Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is commonly associated with both microvascular and macrovascular complications and a strong correlation exists between glycaemic control and the incidence and progression of vascular complications. Pioglitazone, a Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) ligand indicated for therapy of type T2DM, induces vascular effects that seem to occur independently of glucose lowering.

Methods

By using a hindlimb ischemia murine model, in this study we have found that pioglitazone restores the blood flow recovery and capillary density in ischemic muscle of diabetic mice and that this process is associated with increased expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). Importantly, these beneficial effects are abrogated when endogenous Akt is inhibited; furthermore, the direct activation of PPARγ, with its selective agonist GW1929, does not restore blood flow recovery and capillary density. Finally, an important collateral vessel growth is obtained with combined treatment with pioglitazone and selective PPARγ inhibitor GW9662.

Conclusion

These data demonstrate that Akt-VEGF pathway is essential for ischemia-induced angiogenic effect of pioglitazone and that pioglitazone exerts this effect via a PPARγ independent manner.

Background

Diabetes mellitus is commonly associated with both microvascular and macrovascular complications such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular events, severe peripheral vascular disease, nephropathy and retinopathy [1]. Vascular function in diabetes has been studied extensively in both animal models and humans [2-4], and impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatation has been documented as a consistent finding in animal models of diabetes induced by alloxan or streptozotocin [5,6]. Consistently, in vivo studies have confirmed that hyperglycemia directly induces endothelial dysfunction both in diabetic and healthy subjects [7]. Moreover an experimental animal model has shown a decreased ability of diabetic mice in restoring the blood flow and the capillarity density after hind-limb ischemia [8]. Thiazolidinedione derivatives (TZDs), such as pioglitazone, troglitazone and rosiglitazone, are indicated for therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They have been demonstrated to be effective alone or in combination with a sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin. Pioglitazone is an insulin sensitizer that promotes glucose metabolism without increasing insulin secretion [9]. In addition to its insulin sensitizing effects, increasing evidence suggests that this drug improve vascular health, vascular function and inflammatory biomarkers of arteriosclerosis [10-12]. Interestingly, these vascular effects seem to occur independently of glucose lowering and have been demonstrated also in non-diabetic, healthy individuals [10,12-14]. These findings have led to the hypothesis that pioglitazone could exert vasculoprotective effects that are independent of its metabolic action.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are the major ligands of TZDs and Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) is the receptor mediating TZDs' antidiabetic effects [15]. TZDs are non-selective and non-specific ligands of PPARs and they are able to stimulate several PPARγ-independent pathways [16-21]. Therefore, the vasculoprotective effect of pioglitazone could be unrelated to the activation of PPARγ.

Akt is a central signaling molecule in regulating cell survival, proliferation, tumor growth and angiogenesis [22]. Short-term Akt activation in inducible Akt1 transgenic mice induces physiological cardiac hypertrophy with maintained vascular density [23], indicating that coronary angiogenesis is enhanced to keep pace with the growth of the myocardium. Similar observations have also been made in skeletal muscle cells: Akt activation results in myofiber growth associated with enhanced Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), a prototypical angiogenic agent, secretion and induces blood vessel recruitment [24]. VEGF and Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) are key angiogenic growth factors induced by hypoxia [25], and expression of these two growth factors is enhanced by short-term Akt activation in the myocardium [23]. Furthermore, transgenic co-expression of VEGF and Ang-2 exhibits synergistic effects on induction of coronary angiogenesis in the myocardium [26]. Thus, Akt-mediated growth-promoting signals act to enhance angiogenesis in a paracrine manner, providing a mechanism by which angiogenesis is coordinately regulated. Some authors have shown that the treatment with pioglitazone in an experimental model of hind-limb ischemia in diabetic mice up-regulates VEGF expression and this is associated with the phosphorylation/activation of eNOS at Ser1177 and Akt at Ser473 [8]. Given pre-existing data, we hypothesized that pioglitazone could improve impaired angiogenesis in diabetic mice by Akt-VEGF pathway, independently of PPARγ receptor.

Methods

Animals and drugs administration

The investigation was approved by A. Gemelli University Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male 8-12-week-old C57BL/6J mice were used for experiments. Diabetes was induced by administering 50 mg/kg body wt streptozotocin (STZ; Sigma) in citrate buffer (pH 4.5), intraperitoneally (i.p.) during the fasting state, for 5 days, as previously described [27]. Hyperglycemia was verified 2 days after STZ injection by an Accu-Check Active glucometer (Roche). We considered mice to be diabetic when blood glucose was at least 16 mmol/l (normal 5-8 mmol/l). Overall, 50 mice showed a blood glucose level of at least16 mmol/l, both 1 and 2 week after the STZ injection and, therefore, were included in the experimental diabetic group. A first group of 10 STZ-diabetic mice received pioglitazone (3 mg/kg per day) by gavage for two weeks [8]. To evaluate whether the effect of pioglitazone was mediated by PPARγ, a second group of 10 STZ-diabetic pioglitazone-treated mice, received a PPARγ selective antagonist, GW9662 (Sigma), at the dosage of 2 mg/kg i.p., administered 1 h before pioglitazone [28]. To evaluate whether the effect of pioglitazone was mediated by Akt, a third group of 10 STZ-diabetic pioglitazone-treated mice, FPA-124 (Echelon), a cell-permeable inhibitor of Akt (Sigma), was administered by gavage at the dosage of 20 mg/kg/bid, everyday of pioglitazone-treatment period [29,30]. Finally, to evaluate the role of PPARγ on ischemia-induced angiogenesis, a fourth group of 10 STZ-diabetic mice was gavaged twice daily for two weeks with GW1929 (Sigma), a PPARγ selective agonist, at 5 mg/kg dosage [31]. The last group of 10 STZ-diabetic mice received vehicle (0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose) by gavage everyday for two weeks after surgery. Finally, 10 untreated C57BL/6J mice were also included in the model. The last two groups were used as controls.

Mouse hindlimb ischemia model

After two weeks from the beginning of the treatment with pioglitazone (n = 10), pioglitazone + GW9662 (n = 10), pioglitazone + FPA-124 (n = 10), GW1929 (n = 10), unilateral hindlimb ischemia was induced by excising the right femoral artery, as previously described [32]. Right femoral artery ligation was used to induce hindlimb ischemia in untreated and the STZ-diabetic mice receiving vehicle. Briefly, all animals were anesthetized with an i.p. injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg). The proximal and distal portions of the femoral artery and the distal portion of the saphenous artery were ligated. The arteries and all side branches were dissected free and excised. The skin was closed with 5-0 surgical suture. A laser Doppler perfusion imager system (PeriScan PIM II, Perimed) was used to measure hindlimb blood perfusion before and after surgery and then followed at 7-day intervals, until the end of the study, for a total follow-up of 28 days after surgery [32]. Before imaging, excess hairs were removed from the limbs using depilatory cream and mice were placed on a heating plate at 40°C. To avoid the influence of ambient light and temperature, results were expressed as the ratio between perfusion in the right (ischemic) versus left (non-ischemic) limb.

Histological Assays

At one and four weeks after surgery, mice were sacrificed by i.p. injection of an overdose of pentobarbital. The whole limbs were fixed in methanol overnight. The femora were carefully removed, and the ischemic thigh muscles were embedded in paraffin. All the specimens were routinely fixed overnight in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The sections for immunohistochemistry were collected on 3-aminopropyltriethoxy-silane (Sigma), allowed to dry overnight at 37°C to ensure optimal adhesion, dewaxed, rehydrated, and treated with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase. For antigen retrieval (CD31 only, not necessary for VEGF) the section were microwave treated in 1 mM EDTA at pH 8 for 10 min and allowed to cool for 20 min. Endogenous biotin was saturated using a biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories). The sections were incubated at room temperature for 30 min with the following antibodies: purified rat anti-mouse CD31 [dilution 1:30; monoclonal (IgG2a); BD Bioscience] and rabbit anti-mouse VEGF [dilution 1:100, polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology]. The slides were incubated for 1 h in the humid chamber at room temperature, then with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 10 minutes, washed, incubated with DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin. Capillary density was measured by counting six random high-power (magnification × 200) fields or a minimum of 200 fibers from each ischemic and non-ischemic limb on an inverted light microscope, and was expressed by the number of CD31+ cells per square millimeter or per fiber. Area was measured with a NIH Image analysis system (ImageJ 1.41). Two operators extracted independently the results.

Western Blotting

Immunoblotting was performed on homogenates of muscle tissues. Proteins (40 mg per lane) were separated in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidine difluoride membranes [33]. Membranes were incubated with antibodies against phospho-Akt (Ser473, 1:500, Cell Signaling Technology Company), Akt (1:1000, New England Biolabs) and VEGF (1:500, R&D Systems). Antibody binding was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000; Chemicon) and enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare Bioscience). Finally, the blots were reprobed with total Akt, VEGF, or actin (1:5000, Sigma).

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean value ± SEM. Statistical comparisons of means were performed by ANOVA followed by Student's t-test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Pioglitazone enhances blood flow recovery in diabetic mice after hind-limb ischemia

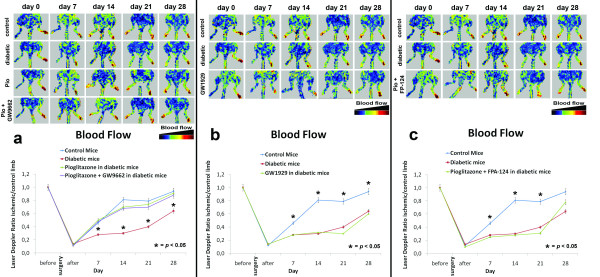

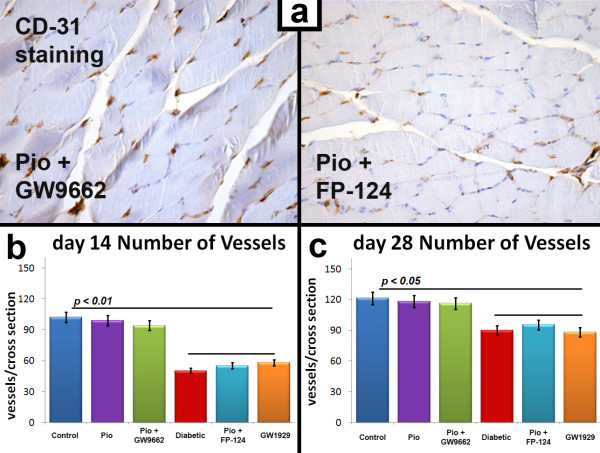

Pioglitazone treatment results in improved perfusion and favorably modulation of capillary density in ischemic skeletal muscle of diabetic mice. Laser Doppler perfusion imaging was performed before, immediately after and on days 7, 14, 21 and 28 after surgery. Perfusion recovery was significantly attenuated in STZ-diabetic mice treated with vehicle, compared with normoglycemic mice (Fig. 1a) and, as previously reported [8], pioglitazone restored the blood flow recovery in STZ-diabetic mice, reaching almost 80% of the blood flow of the untreated leg in four weeks (Fig. 1a). Collateral vessel formation was also histologically evaluated by the capillary density of the ischemic hindlimb muscle collected two and four weeks after surgery (Fig. 2). Consistently with the measurement of laser Doppler imaging, anti-CD31 immunostaining revealed that angiogenesis in the ischemic hindlimb is impaired in the diabetic mice treated with vehicle. Pioglitazone significantly restored the number of detectable capillaries in the ischemic leg of the diabetic mice to a normal level (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

a. Foot blood flow monitored in vivo by laser Doppler perfusion imaging (LDPI) in control, STZ-diabetic, pioglitazone-treated and pioglitazone+GW9662-treated mice. Evaluation of the ischemic (right) and non-ischemic (left) hindlimbs, immediately after and on days 7, 14, 21 and 28 after surgery. Red indicates normal perfusion while blue a marked reduction in blood flow of ischemic hindlimb. Pioglitazone restored blood flow recovery in diabetic mice, compared with normoglycemic mice. Interestingly, pioglitazone associated with selective PPARγ inhibitor GW9662 restored blood flow recovery in diabetic mice. The blood flow of the ischemic hindlimb is expressed as the ratio between perfusion of the ischemic limb versus uninjured limb. *p < 0.05 vs control, STZ-diabetic and pioglitazone-treated mice. b. LDPI in control, STZ-diabetic, GW1929-treated mice. Selective PPARγ agonist GW1929 did not restore blood flow recovery in diabetic mice, compared with normoglycemic and STZ-diabetic mice.*p < 0.05 vs STZ-diabetic and GW1929-treated mice. c. LDPI in control, STZ-diabetic and pioglitazone+FP-124-treated mice. Pioglitazone associated with selective Akt inhibitor FP-124 did not restore blood flow recovery in diabetic mice, compared with normoglycemic and STZ-diabetic mice.*p < 0.05 vs STZ-diabetic and pioglitazone+FP-124-treated mice.

Figure 2.

a. Representative photomicrographs of ischemic muscle sections from pioglitazone+GW9662-treated and from pioglitazone+FP-124-treated diabetic mice stained with antibody directed against CD-31, 28 days after surgery. Positive staining appears in brown. Magnification ×40. Number of vessels per cross section is significantly reduced in pioglitazone+FP-124-treated diabetic mice respect to GW9662-treated diabetic mice. b. Quantification of ischemia-induced angiogenesis 14 and 28 days after surgery. Number of vessels per cross section is significantly reduced in STZ-diabetic, pioglitazone+FP-124-treated and GW1929-treated mice vs STZ-diabetic, pioglitazone+FP-124-treated and GW9662-treated mice (p < 0.01 at 14 days and p < 0.05 at 28 days).

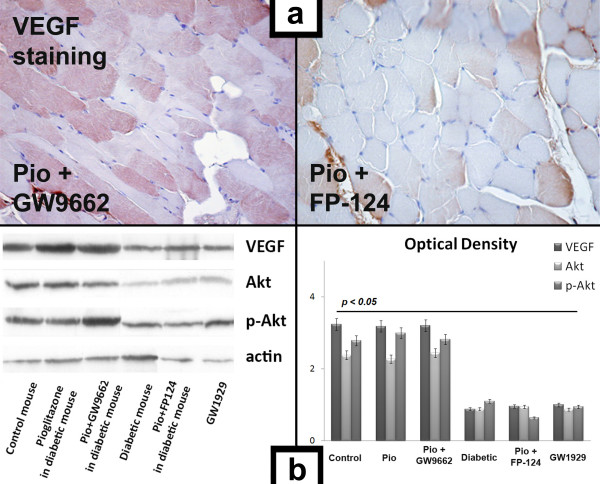

Pioglitazone-induced angiogenic response occurs in association with VEGF production and increases phosphorylation of Akt

Immunostaining revealed that VEGF expression had increased in the ischemic tissue of normoglycemic mice compared to STZ-diabetic mice (Fig. 3). VEGF concentration in ischemic tissue was also significantly higher in pioglitazone-treated STZ-mice than in untreated STZ-diabetic mice (Fig. 3), underlying the crucial role of VEGF in pioglitazone-induced angiogenic response. To further investigate the mechanism by which pioglitazone stimulates angiogenesis in diabetic mice, we evaluated VEGF and Akt expression in the ischemic leg 7 days after surgery by Western blotting analysis (Fig. 3). Pioglitazone normalized VEGF expression and induced phosphorylation/activation of Akt at Ser473, which expression was reduced in diabetic mice treated with vehicle.

Figure 3.

a. Representative photomicrographs of ischemic muscle sections from pioglitazone+GW9662-treated and from pioglitazone+FP-124-treated diabetic mice stained with antibody directed against VEGF, 7 days after surgery. Positive staining appears in brown. Magnification ×40. b. VEGF, Akt and pAkt expression 7 days after surgery. Representative Western blot and optical density evaluation of VEGF Akt, pAkt and actin protein content in the ischemic legs of control, pioglitazone-treated, pioglitazone+GW9662-treated, STZ-diabetic, pioglitazone+FP-124-treated and GW9662-treated mice. Pioglitazone normalized VEGF expression with enhanced phosphorylation of Akt in ischemic muscle. After pioglitazone administration, even when PPARγ activity was inhibited by GW9662, STZ-diabetic mice showed a normalized expression of VEGF and enhanced levels of p-Akt Ser473 in ischemic limbs compared to those treated with pioglitazone+FP-124 or with GW1929. Selective PPARγ agonist GW1929 or pioglitazone associated with selective Akt inhibitor FP-124 did not normalize VEGF expression in diabetic micevs STZ-diabetic, pioglitazone+FP-124-treated and GW1929-treated mice. p < 0.05.

The ability of pioglitazone in normalizing the expression of VEGF, activating Akt and restoring blood flow is independent of PPARγ activation

To determine if pioglitazone-induced angiogenic response in STZ-diabetic mice depends on activation of PPARγ, we compared two groups of STZ-diabetic mice undergoing hindlimb ischemia with selective PPARγ agonist GW1929 (n = 10) or with pioglitazone associated with selective PPARγ inhibitor GW9662 (n = 10). Laser Doppler perfusion imaging was performed before, immediately after and on days 7, 14, 21 and 28 after surgery. Surprisingly, the treatment with GW1929 did not exert any effect on ischemic muscle (Fig. 1b), on VEGF expression (Fig. 3) and on blood flow recovery, while pioglitazone maintained its activity in normalizing the expression of VEGF (Fig. 3), activating Akt and restoring blood flow also in mice where PPARγ was inhibited by GW9662 (Fig. 1a).

These results suggest that pioglitazone presides its favorable effects on ischemic-induced angiogenesis regardless of PPARγ activity.

The activity of pioglitazone on VEGF expression and blood flow recovery was abolished by selective inhibition of Akt

To confirm the hypothesis that the up-regulation of VEGF induced by pioglitazone occurs through the activation of Akt pathway, we inhibited Akt in diabetic mice subjected to hind-limb ischemia and pre-treated with pioglitazone. Seven days after surgery Akt was inhibited and pioglitazone had no effect on VEGF expression of ischemic muscles in diabetic mice (Fig. 3). Furthermore, combined treatment of pioglitazone with FPA-124, a selective Akt inhibitor, had no effect on blood flow recovery evaluated by laser Doppler (Fig. 1c).

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated the effect of pioglitazone on angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia in diabetic mice. We have been able to show that vascular Akt system plays an important role in ischemia-induced angiogenesis in pioglitazone-treated mice in vivo. In fact, pioglitazone failed to promote blood flow recovery when Akt activity was inhibited by FP-124, indicating that Akt is an essential co-factor to promote collateral growth in response to tissue ischemia during treatment with pioglitazone. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the important roles of vascular Akt system in ameliorating endothelial dysfunction and restoring ischemia-induced angiogenesis in diabetic mice treated with pioglitazone, including induction of post-ischemic angiogenesis and secretion of VEGF from ischemic muscle. In addition, this study demonstrates that the positive effect of pioglitazone occurs via a PPARγ independent mechanism.

T2DM is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality that places a substantial economic and health burden on the public. Although the increased death rate is mainly due to cardiovascular disease, deaths from non-cardiovascular causes are also increasing [34]. T2DM is commonly associated with both microvascular and macrovascular complications [35]. A strong correlation exists between glycaemic control and the incidence and progression of microvascular complications [36], while its impact on macrovascular events evolution seems weaker [37]. Several long-term diabetes mellitus complications are characterized by vasculopathy associated with aberrant angiogenesis. Excessive angiogenesis plays an important role in diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy whereas inhibited angiogenesis contributes to impaired wound healing and impaired coronary collateral vessel development. Indeed, diabetic neuropathy is linked to reduced nutritive blood flow secondary to diabetes and could potentially be improved by inducing angiogenesis in regions of inadequate perfusion [38]. Furthermore, the increased glomerular filtration rate in diabetic nephropathy may be the consequence of an enlarged glomerular filtration surface resulting from excessive angiogenesis [39]. Moreover, diabetic patients frequently suffer of chronic non-healing ulcers usually localized on pressure points of the foot [40] and the presence of small abnormal blood vessels has been reported at the wound edge of diabetic ulcers [41]. The increased morbidity and mortality related to atherosclerosis and the ensuing coronary and peripheral artery disease may be due to an impaired ability to form collateral vessel in the diabetic scenario [42]. Indeed, these patients often present a wide vascular disease and a great number of vascular occlusions, due to diabetes-induced deficiencies of angiogenesis [43]. Diabetes-induced impairment of collateral formation has been also demonstrated in murine models: hindlimb ischemia created by ligation of the femoral artery is associated with a reduced formation of capillaries and a reduction in blood flow to the ischemic limb in diabetic versus non-diabetic mice [44]. Thus, several agents are implicated in development of abnormal angiogenesis in diabetes mellitus, including dysregulation of VEGF local expression [45,46] and other growth factors or cytokines imbalances [47,48] in a general metabolic derangement [49].

PPARs are considered important factors for ameliorating hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia in subjects with T2DM. PPARγ activation improves insulin sensitivity, decreases inflammation, plasma levels of free fatty acids and blood pressure, so indirectly leading to inhibition of atherogenesis, improvement of endothelial function and reduction of cardiovascular events. The insulin-sensitizing drugs TZDs, as PPARγ agonists, have beneficial effects on serum lipids in diabetic patients and have also been shown to inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis in animal models [17]. Increasing evidence suggests that TZDs improve endothelium-dependent vascular function and inflammatory biomarkers of arteriosclerosis, independently of glucose-lowering effect in diabetic and non-diabetic individuals [50]. Interestingly, TZDs were reported to increase VEGF expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells [51], to promote angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia [52] and to reduce myocardial infarction size in animal model [53]. Recent findings showed that pioglitazone restores the impaired angiogenesis in ischemic muscle of diabetic mice [8]. In all these studies, Authors have assumed that the effects induced by TZDs were mediated by the activation of PPARγ, without considering that TZDs are non-selective and non-specific ligands of this nuclear receptor, since they are able to stimulate several PPARγ-independent pathways that are important in angiogenesis [18-21,54]. About pioglitazone, there are many biological effects idipendent of PPARγ activation; in fact, pioglitazone causes PPARγ-independent relaxation of isolated blood vessel [55], inhibits homocysteine-induced vascular smooth muscle cells migration that is independent of PPARγ [56] and prevents apoptosis of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in mice as well as in human EPCs in a PI3K-dependent manner [57]. Furthermore, this agent inhibits lung cancer cell growth and its antiproliferative action does not occurs via PPARγ activation [58]. Importantly, pioglitazone is metabolized predominantly via the CYP 3A4, CYP 2C8 and CYP 1A1 pathways, through hydroxylation and oxidation [59] and, since the CYP 3A4 metabolic pathway is common to the metabolism of several drugs, the potential for drug interactions and consequent alterations in efficacy and safety of numerous concomitant medications should be considered when this drug is co-administered with CYP 3A4-metabolized agents. Effectively, pioglitazone stimulates PPARγ but the vasculoprotective effects could be unrelated to the activation of PPARγ.

In a hindlimb ischemia murine model, our results confirm that diabetic mice display a decreased angiogenic response, that pioglitazone restores the blood flow recovery and capillary density in ischemic muscle and that this process is associated with increased expression of VEGF. Importantly, these beneficial effects are abrogated when endogenous Akt is inhibited; furthermore, the direct activation of PPARγ, with its selective agonist GW1929, does not restore blood flow recovery and capillary density. Finally, an important collateral vessel growth is obtained with combined treatment with pioglitazone and selective PPARγ inhibitor GW9662. These data demonstrate that Akt pathway is essential for ischemia-induced angiogenic effect of pioglitazone and that pioglitazone exerts this effect via a PPARγ independent manner.

The epidemic of T2DM has created a large need for new hypoglycaemic and hypolipemic therapies; the PPARs agonists represent a potentially important new group of drugs with a mechanism of action differing from and perhaps complementary to existing therapies. The emergence of the angiogenesis altered signalling paradigm in T2DM promises to enhance our understanding of cardiovascular complications of diabetes and the advances in the understanding of the biology of angiogenesis enabled the development of new therapeutic strategies for promoting angiogenesis. Since pioglitazone is a drug currently used with excellent tolerance and limited toxicity, our data might offer a novel and potentially low toxic approach for the treatment of diabetes-associated altered angiogenesis. Our findings provide new information to understand the biological effects of pioglitazone and its role in ischemia-induced angiogenesis, with potentially important implications for the management of subjects affected by T2DM cardiovascular complications.

Conclusion

The novel finding of the present study is that vascular Akt system plays an essential role in restoring angiogenesis in diabetic mice treated with pioglitazone. In fact, pioglitazone failed to promote blood flow recovery when Akt activity was abolished, indicating that Akt is essential for pioglitazone to promote collateral growth in response to tissue ischemia. Finally, this is the first demonstration that the positive effect of pioglitazone occurs via a PPARγ independent mechanism. This study represents a step forward towards a better understanding of mechanisms implicated in the vascular effects of pioglitazone.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FB and GS participated in the design of the study, performed the hindlimb ischemia model and in part performed data analysis. VA and ES performed the immunohistochemical analysis. PR and GP carried out the immunoassays. GDA performed the statistical analysis. LI reviewed the manuscript. GG and AF conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Work performed by the authors is supported by the Catholic University School of Medicine, Rome, Italy.

Contributor Information

Federico Biscetti, Email: f.biscetti@gmail.com.

Giuseppe Straface, Email: giuseppestraface@gmail.com.

Vincenzo Arena, Email: vincenzo.arena@rm.unicatt.it.

Egidio Stigliano, Email: egstigliano@gmail.com.

Giovanni Pecorini, Email: g.pecorini@gmail.com.

Paola Rizzo, Email: rizzo.paola@gmail.com.

Giulia De Angelis, Email: giulia.deangelis78@gmail.com.

Luigi Iuliano, Email: iuliano.luigi@gmail.com.

Giovanni Ghirlanda, Email: gghirlanda@rm.unicatt.it.

Andrea Flex, Email: andrea.flex@rm.unicatt.it.

References

- Cade WT. Diabetes-related microvascular and macrovascular diseases in the physical therapy setting. Phys ther. 2008;88:1322–1335. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooke JE, Goh KL. Vascular function in Type 2 diabetes mellitus and pre-diabetes: the case for intrinsic endotheiopathy. Diabet Med. 1999;16:710–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal DK, McNeill JH. Effect of diabetes on vascular smooth muscle function in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rat mesenteric artery. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1987;65:2274–2280. doi: 10.1139/y87-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schram MT, Chaturvedi N, Schalkwijk C, Giorgino F, Ebeling P, Fuller JH, Stehouwer CD. Vascular risk factors and markers of endothelial function as determinants of inflammatory markers in type 1 diabetes: the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study. Diabetes care. 2003;26:2165–2173. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraji S, Jayakody L, Senaratne MP, Thomson AB, Kappagoda T. Endothelium-dependent relaxation in aorta of BB rat. Diabetes. 1987;36:978–981. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.36.8.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhan WG. Impairment of endothelium-dependent dilatation of cerebral arterioles during diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H621–625. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.3.H621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Zhong C, Yu Y, Li K. Acute effects of hyperglycaemia with and without exercise on endothelial function in healthy young men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99:585–591. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PH, Sata M, Nishimatsu H, Sumi M, Hirata Y, Nagai R. Pioglitazone ameliorates endothelial dysfunction and restores ischemia-induced angiogenesis in diabetic mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Taketomi S, Sugiyama Y, Shimura Y, Sohda T, Meguro K, Fujita T. Effects of pioglitazone on glucose and lipid metabolism in normal and insulin resistant animals. Arzneimittelforschung. 1990;40:156–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzel J, Balletshofer B, Rittig K, Walcher D, Kratzer W, Hombach V, Haring HU, Koenig W, Marx N. Rapid effects of rosiglitazone treatment on endothelial function and inflammatory biomarkers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1804–1809. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000176192.16951.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfutzner A, Marx N, Lubben G, Langenfeld M, Walcher D, Konrad T, Forst T. Improvement of cardiovascular risk markers by pioglitazone is independent from glycemic control: results from the pioneer study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1925–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrosch F, Passauer J, Fischer S, Fuecker K, Hanefeld M, Gross P. In type 2 diabetes, rosiglitazone therapy for insulin resistance ameliorates endothelial dysfunction independent of glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:484–490. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx N, Wohrle J, Nusser T, Walcher D, Rinker A, Hombach V, Koenig W, Hoher M. Pioglitazone reduces neointima volume after coronary stent implantation: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in nondiabetic patients. Circulation. 2005;112:2792–2798. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.535484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horio T, Suzuki M, Takamisawa I, Suzuki K, Hiuge A, Yoshimasa Y, Kawano Y. Pioglitazone-induced insulin sensitization improves vascular endothelial function in nondiabetic patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1626–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumasia R, Eagle KA, Kline-Rogers E, May N, Cho L, Mukherjee D. Role of PPAR- gamma agonist thiazolidinediones in treatment of pre-diabetic and diabetic individuals: a cardiovascular perspective. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2005;5:377–386. doi: 10.2174/156800605774370362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano H, Hasegawa H, Zou Y, Komuro I. Pleiotropic actions of PPAR gamma activators thiazolidinediones in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2779–2786. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel CB, De Lemos JA, Wyne KL, McGuire DK. Thiazolidinediones and risk for atherosclerosis: pleiotropic effects of PPar gamma agonism. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3:65–71. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HB, Hu YS, Medcalf RL, Simpson RW, Dear AE. Thiazolidinediones inhibit TNFalpha induction of PAI-1 independent of PPARgamma activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turturro F, Oliver R, 3rd, Friday E, Nissim I, Welbourne T. Troglitazone and pioglitazone interactions via PPAR-gamma-independent and -dependent pathways in regulating physiological responses in renal tubule-derived cell lines. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1137–1146. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00396.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau CW, Yang CC, Kulp SK, Chen KF, Chen CS, Huang JW, Chen CS. Thiazolidenediones mediate apoptosis in prostate cancer cells in part through inhibition of Bcl-xL/Bcl-2 functions independently of PPARgamma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1561–1569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli A, Ceni E, Crabb DW, Mello T, Salzano R, Grappone C, Milani S, Surrenti E, Surrenti C, Casini A. Antidiabetic thiazolidinediones inhibit invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells via PPARgamma independent mechanisms. Gut. 2004;53:1688–1697. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.031997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steelman LS, Stadelman KM, Chappell WH, Horn S, Basecke J, Cervello M, Nicoletti F, Libra M, Stivala F, Martelli AM, McCubrey JA. Akt as a therapeutic target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:1139–1165. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.9.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiojima I, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Schiekofer S, Ito M, Liao R, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Disruption of coordinated cardiac hypertrophy and angiogenesis contributes to the transition to heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2108–2118. doi: 10.1172/JCI24682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Kureishi Y, Yang J, Luo Z, Guo K, Mukhopadhyay D, Ivashchenko Y, Branellec D, Walsh K. Myogenic Akt signaling regulates blood vessel recruitment during myofiber growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4803–4814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4803-4814.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouyssegur J, Dayan F, Mazure NM. Hypoxia signalling in cancer and approaches to enforce tumour regression. Nature. 2006;441:437–443. doi: 10.1038/nature04871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti RP, Richardson CD, Sato TN. Orchestration of angiogenesis and arteriovenous contribution by angiopoietins and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8219–8224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122109599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg IJ, Hu Y, Noh HL, Wei J, Huggins LA, Rackmill MG, Hamai H, Reid BN, Blaner WS, Huang LS. Decreased lipoprotein clearance is responsible for increased cholesterol in LDL receptor knockout mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:1674–1682. doi: 10.2337/db08-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Ozaki M, Kishioka S. Pioglitazone attenuates tactile allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice subjected to peripheral nerve injury. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:341–347. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08207FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barve V, Ahmed F, Adsule S, Banerjee S, Kulkarni S, Katiyar P, Anson CE, Powell AK, Padhye S, Sarkar FH. Synthesis, molecular characterization, and biological activity of novel synthetic derivatives of chromen-4-one in human cancer cells. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3800–3808. doi: 10.1021/jm051068y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu QS, Ren W, Korchin B, Lahat G, Dicker A, Lu Y, Mills G, Pollock RE, Lev D. Soft tissue sarcoma cells are highly sensitive to AKT blockade: a role for p53-independent up-regulation of GADD45 alpha. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2895–2903. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way JM, Gorgun CZ, Tong Q, Uysal KT, Brown KK, Harrington WW, Oliver WR, Jr, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Hotamisligil GS. Adipose tissue resistin expression is severely suppressed in obesity and stimulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25651–25653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couffinhal T, Silver M, Zheng LP, Kearney M, Witzenbichler B, Isner JM. Mouse model of angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1667–1679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JW, Chen YH, Lin FY, Chen YL, Lin SJ. Ginkgo biloba extract inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced reactive oxygen species generation, transcription factor activation, and cell adhesion molecule expression in human aortic endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1559–1566. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000089012.73180.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai FE, Moss SE, Klein BE, Klein R. Relationship of glycemic control, exogenous insulin, and C-peptide levels to ischemic heart disease mortality over a 16-year period in people with older-onset diabetes: the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR) Diabetes care. 2008;31:493–497. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden-Albala B, Cammack S, Chong J, Wang C, Wright C, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Diabetes, fasting glucose levels, and risk of ischemic stroke and vascular events: findings from the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) Diabetes care. 2008;31:1132–1137. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore G, Bruttomesso D, Nosari I, Tiengo A, Trevisan R. Glycaemic control and microvascular complications in a large cohort of Italian Type 1 diabetic out-patients. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2002;15:232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jermendy G. [Glycaemic control and macrovascular complications in patients with diabetes mellitus] Orvosi hetilap. 2007;148:17–20. doi: 10.1556/OH.2007.27973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Komada MR, Sane DC. Abnormal angiogenesis in diabetes mellitus. Med Res Rev. 2003;23:117–145. doi: 10.1002/med.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyengaard JR, Rasch R. The impact of experimental diabetes mellitus in rats on glomerular capillary number and sizes. Diabetologia. 1993;36:189–194. doi: 10.1007/BF00399948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots MA, Lamme EN, Zeegelaar J, Mekkes JR, Bos JD, Middelkoop E. Differences in cellular infiltrate and extracellular matrix of chronic diabetic and venous ulcers versus acute wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:850–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MW, Herrick SE, Spencer MJ, Shaw JE, Boulton AJ, Sloan P. The histology of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabet Med. 1996;13:S30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltenberger J. Impaired collateral vessel development in diabetes: potential cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:554–560. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarom R, Zirkin H, Stammler G, Rose AG. Human coronary microvessels in diabetes and ischaemia. Morphometric study of autopsy material. J Pathol. 1992;166:265–270. doi: 10.1002/path.1711660308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard A, Silver M, Chen D, Kearney M, Magner M, Annex B, Peters K, Isner JM. Rescue of diabetes-related impairment of angiogenesis by intramuscular gene therapy with adeno-VEGF. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:355–363. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, Keyt BA, Jampel HD, Shah ST, Pasquale LR, Thieme H, Iwamoto MA, Park JE, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1480–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412013312203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida K, Makita Z, Yamagishi S, Atsumi T, Miyoshi H, Obara S, Ishida M, Ishikawa S, Yasumura K, Koike T. Suppression of transforming growth factor beta and vascular endothelial growth factor in diabetic nephropathy in rats by a novel advanced glycation end product inhibitor, OPB-9195. Diabetologia. 1999;42:579–588. doi: 10.1007/s001250051198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampfer H, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S. Expressional regulation of angiopoietin-1 and -2 and the tie-1 and -2 receptor tyrosine kinases during cutaneous wound healing: a comparative study of normal and impaired repair. Lab Invest. 2001;81:361–373. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger RH, Bode-Boger SM, Szuba A, Tsao PS, Chan JR, Tangphao O, Blaschke TF, Cooke JP. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA): a novel risk factor for endothelial dysfunction: its role in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1998;98:1842–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen YD, Bursell SE, Wilkison WO, Clermont AC, Brittis M, McGovern TJ, Spiegelman BM. Vasodilation of rat retinal microvessels induced by monobutyrin. Dysregulation in diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2872–2876. doi: 10.1172/JCI116908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Tafuri S. Modulation of PPARgamma activity with pharmaceutical agents: treatment of insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:38–47. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa K, Hosoi M, Koyama H, Tanaka S, Fukumoto S, Morii H, Nishizawa Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists increase vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:571–574. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu K, Lee ST, Koo JS, Jung KH, Kim EH, Sinn DI, Kim JM, Ko SY, Kim SJ, Song EC, Kim M, Roh JK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-agonist, rosiglitazone, promotes angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. Brain research. 2006;1093:208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman NS, Hattori Y, McDonald MC, Mota-Filipe H, Cuzzocrea S, Pisano B, Chatterjee PK, Thiemermann C. Ligands of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR-gamma and PPAR-alpha) reduce myocardial infarct size. Faseb J. 2002;16:1027–1040. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0793com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner OS, Shiau CW, Chen CS, Graves LM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-independent activation of p38 MAPK by thiazolidinediones involves calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and protein kinase R: correlation with endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10109–10118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura H, Yamawaki H, Mukohda M, Okada M, Hara Y. Mechanisms underlying pioglitazone-mediated relaxation in isolated blood vessel. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:258–265. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08117FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Gao PJ, Xi R, Wu CF, Zhu DL, Yan J, Lu GP. Pioglitazone inhibits homocysteine-induced migration of vascular smooth muscle cells through a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-independent mechanism. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:1471–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensch C, Clever YP, Werner C, Hanhoun M, Bohm M, Laufs U. The PPAR-gamma agonist pioglitazone increases neoangiogenesis and prevents apoptosis of endothelial progenitor cells. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra S, Batra RK, Tai HH, Sharma S, Cui X, Dubinett SM. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone decrease prostaglandin E2 in non-small-cell lung cancer cells by up-regulating 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1715–1720. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovitz HE. Differentiating members of the thiazolidinedione class: a focus on safety. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18:S23–29. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]