Abstract

Early developmental abnormalities affecting mesocortical dopamine (DA) neurons may result in later functional deficits that play a role in the emergence of psychiatric illness in adolescence/early adulthood. Little is known about the functional maturation of these neurons under either normal or abnormal conditions. In the present study, 6-hydroxydopamine was infused into the rat medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) on postnatal day (PN) 12-14. On PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65, mPFC extracellular DA and norepinephrine (NE) concentrations were monitored in intact and lesioned rats using in vivo microdialysis. Extracellular DA and NE concentrations in the intact mPFC remain fairly stable across development; one exception being a trend for acute tailshock-evoked DA concentrations to increase as a function of age. Lesioned rats sustained a persistent (~50%) decrease in mPFC tissue DA concentrations. Tailshock-evoked increases in mPFC extracellular DA were attenuated in lesioned rats tested on PN30-35, but not PN45-50 or 60-65. Basal and evoked extracellular NE was unaffected in lesioned rats tested at any age, despite a persistent (~25%) decrease in tissue NE content. Horizontal locomotor activity was also assessed in the present study. Results of previous studies suggest this behavior is modulated by mesoprefrontal DA neurons. Although not significant, acute tailshock- and acute amphetamine-evoked horizontal locomotor activity tended to be attenuated in lesioned rats tested on PN30-35 and augmented in lesioned rats tested on PN60-65. The present data suggest that early partial loss of mesoprefrontal DA nerve terminals, resulting in a persistent decrease in tissue DA concentrations, is unlikely to result in persistent alterations in local DA release.

Keywords: amphetamine, development, microdialysis, norepinephrine, schizophrenia, stress

1. Introduction

It has been suggested that functional deficits occurring as a result of abnormal development of mesoprefrontal dopamine (DA) neurons contribute to psychiatric illnesses, such as attention deficit disorder and schizophrenia [4,23]. Static anatomical and chemical measurements confirm that this innervation undergoes extensive refinement from early embryonic development until adulthood [6,9,14,15,22,32,39,42,43,48,49,51]. However, to our knowledge, the functional capacity of these neurons across development has not been examined even in the intact organism.

Goals of the present study were to examine the functional maturation of cortical catecholamine nerve fibers, as determined by analysis of extracellular DA and norepinephrine (NE) concentrations in the rat medial PFC (mPFC), under normal conditions and conditions of a structural compromise sustained early in development. Previously, we developed a method for producing early partial loss of DA nerve fibers in the rat mPFC, to an extent similar to that observed in postmortem tissue of schizophrenic subjects [7]. Results of our previous study, examining the effects of this lesion on basal and stress-evoked tissue catecholamine concentrations, suggest that early partial loss of mPFC tissue DA results in persistent alterations in basal and stress-evoked neurochemical activity of mesoprefrontal DA nerve fibers. However, postmortem measures of tissue catecholamines and their metabolites do not always reflect changes in neurotransmitter release in vivo. In the present study, we examined the effects of partial loss of mPFC DA sustained on postnatal days (PN) 12–14 on local basal and stress-evoked extracellular catecholamines, using in vivo microdialysis. Since rat neurodevelopment at birth resembles that seen in primates during the second trimester [29], the impact of lesions sustained within the first few postnatal weeks may be relevant to hypotheses that adverse events occurring early in development play a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. In addition, because we and others have found that partial loss of mPFC DA sustained later in development, during late adolescence/early adulthood, differentially affects acute amphetamine- and stress-evoked motor behavior in adult rats [5,24,26,41], horizontal locomotor activity was also monitored in the present studies under basal conditions and in response to acute amphetamine and stress. Neurochemical and behavioral measures were performed on PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65, corresponding to juvenile, adolescent, and adult development [36].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Ten litters of Sprague-Dawley rats consisted of a lactating dam and 12 male pups age PN8-10 were obtained from Animal Technologies Ltd. (Kent, WA). Rats from a single litter were randomly assigned to each of the treatment groups in a study. Litters were housed in metal (302 × 13 cm) or plastic cages (47 × 26 × 20 cm) with cob bedding (Green Pet Products, Conrad, IO). On PN21, rats were weaned and housed 2–4 per cage in hanging wire-mesh cages where they remained until testing. The ambient temperature of the animal housing rooms was maintained at 20–22°C and the room lights were on from 8:00 am to 8:00 pm. All treatments were performed during the light phase of the light/dark cycle. Rodent chow and water were available ad libitum except during microdialysis sampling. Procedures for the treatment of rats were approved by Western Washington University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee using criterion established by the U.S. Animal Welfare Act and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. 6-Hydroxydopamine lesions of the rat mPFC on PN12-14

6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesions of the mPFC were performed as previously described [7]. PD12-14 was chosen for lesions based on previous observations that administration of 6-OHDA earlier in development (PN1-7) does not induce persistent reductions in tissue DA concentrations in the adult rat mPFC [35,38]. On PN12-14, rats were pretreated with the norepinephrine (NE) uptake inhibitor desipramine hydrochloride (0.125 mg base/0.025 ml/10 g in 0.9% NaCl, subcutaneous; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 30 min later anesthetized with isoflurane (Abbot Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL; 4.5% in oxygen for ~5 min and 1–2% for the remainder of the surgery). Rats were placed in a stereotaxic instrument equipped with a neonatal rat adaptor and anesthesia mask (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Throughout surgery, rats rested on a reusable heat packet (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). A glass pipette (tip o.d. = 50–100 μm) was positioned in the mPFC at stereotaxic coordinates: AP+2.1 and ML±0.3 mm from bregma, and DV–2.4 mm (amphetamine study) or DV-2.4 and −3.7 mm (microdialysis study) from dura with the skull flat. After the pipette was in position for 5 min, 1.0 μg 6-OHDA base (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) in 0.25 μl vehicle (0.9% NaCl containing 0.03% ascorbic acid) was infused over 5 min using a pneumatic picopump (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The pipette was left in position for an additional 5 min to allow for dispersal of the toxin or vehicle. The infusion procedure was repeated in the contralateral hemisphere, the pipette was removed and the scalp sutured. Upon resuming normal motor activity, pups were returned to the litter. Rats were handled 2–3 times/week by an animal care technician. Control subjects were either untreated or subjected to the same procedure as lesioned rats (including DMI pretreatment) with the exception that 0.25 μl of vehicle only was infused bilaterally into the mPFC. Previously, we reported that vehicle infusions fail to affect mPFC catecholamine nerve terminals [47]. Similarly, in pilot studies performed in rats sustaining infusions on PN12-14 and sacrificed on PN30-35 or 60-65, tissue catecholamine concentrations did not differ between vehicle-infused and unoperated controls. Specifically, in vehicle-infused and unoperated controls sacrificed on PN30-35, mPFC DA concentrations were 0.09±0.01 and 0.08±0.01 and NE concentrations were 0.43±0.03 and 0.37±0.03 ng/mg tissue, respectively. In vehicle-infused and unoperated controls sacrificed on PN60-65, DA concentrations were 0.08±0.01 and 0.09±0.01 and NE concentrations were 0.45±0.02 and 0.39±0.01 ng/mg, respectively.

2.3. In vivo microdialysis and horizontal locomotor activity

On PN30-35, 45-50 or 60-65, rats were anesthetized with Equithesin (3 ml/kg, intraperitoneal; 258 mM chloral hydrate, 86 mM magnesium sulfate, 25% v/v propylene glycol, and 20% v/v of 50 mg/ml Nembutal sodium solution obtained from Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Deerfield, IL). A vertical, concentric microdialysis probe was positioned in the mPFC (4.0 × 0.25 mm active membrane). Stereotaxic coordinates for microdialysis probes in the mPFC were: PN30-35 at AP+3.0, ML+0.8, and DV-5.3; PN45-50 at AP+3.1, ML+0.9, and DV-5.8; and PN60-65 at AP+3.2, ML+1.0, and DV-6.0 (AP and ML are mm from bregma and DV are mm from dura, with the skull flat).

Beginning immediately following implantation, probes were continuously perfused with artificial cerebral spinal fluid (145 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 1.2 mM CaCl2) at rate of 1.5 μl/min using a syringe pump (KD Scientific, New Hope, PA). Microdialysis sampling began ~18 hrs after implantation. Rats were housed and tested in a square acrylic cage (46 cm3) with cob flooring. The cage was located in a custom-built chamber (51 cm2) comprised of a single-layer of photocells (20 cells per side) forming a horizontal grid. Photocells were 2.5 cm apart and 5 cm above the floor of the chamber. Photocell interruptions were recorded 3 times per second and microdialysis samples were collected every 15 min throughout the experiment. Following at least 1 hr of baseline sampling, a cuff was positioned on the base of the tail. A 0.6 mA shock was delivered through the cuff using a shock generator (BRS-LVE, Laurel, MD). The shock cycle consisted of a 1-s shock delivered every 10 s for 45 s, followed by a 5-min intershock interval. This cycle was repeated 6 times during the 30-min tailshock interval after which the cuff was removed. The effects of systemic d-amphetamine sulfate (1.5 mg/kg ip, Sigma-Aldrich) on horizontal locomotor activity was examined in control rats and rats previously sustaining 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC on PN12-14 and subsequently tested on PN30-35 and 60-65 (in vivo microdialysis was not performed in conjunction with this study). Analysis of locomotor activity was performed exactly as described above with the exception that d-amphetamine was administered following 30-min of habituation to the activity chamber. The dose of d-amphetamine was chosen based on results of previous studies demonstrating that reversible and irreversible inactivation of the hippocampus sustained during neonatal development results in the emergence of hyperresponsiveness to the motor stimulant effects of 1.5 mg/kg d-amphetamine in adult animals [33,34].

2.4. Tissue dissection, verification of probe placement, and neurochemical analyses

Rats were decapitated 1–4 days after testing. The brains were rapidly removed and bisected. The rostral portion, containing the mPFC, was frozen onto a microtome stage. A thick coronal section was cut at the level of the mPFC [2.9–4.3 mm anterior to bregma; [37]] and placed on ice. As required, this section was inspected for localization of microdialysis probe tracts within the mPFC. The tract was required to be within the region medial to the corpus callosum and lateral to the midline. Data from rats in which the probe tract was outside this region were excluded from analysis. The right and left mPFC were freehand dissected from this section [24]. Tissue samples were weighed, sonicated, and filtered as described previously [7]. The resulting supernatant was stored at −80° C until analyzed using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection.

Catecholamine concentrations in dialysate and tissue were determined using HPLC with electrochemical detection. The HPLC system consisted of an injector (Rheodyne, Rohnert Park, CA), pump (ESA, Chelmsford, MA) and pulse dampener (SSI, State College, PA). Peak separation was accomplished using a reversed-phase C18 column (3.2 × 150 mm, 3 μm; ESA or Supelcosil, Bellefonte, PA) and, in the case of tissue supernatant, a guard column (4.0 × 20 mm, 5 μm; Supelcosil). Mobile phase (ESA, #71-1332) was circulated at a rate of 0.4 ml/min. Detection was performed using a potentiostat (ESA, Model 5100A) controlling a conditioning cell (ESA, Model 5020) maintained at +400 mV and an analytical cell (ESA, Model 5014) with the first and second electrodes maintained at −140 and +125 mV, respectively. Analytes were quantified by comparing the oxidation signals from the second electrode produced by samples to those produced by standards of known concentrations. The detection limit of the assay was ~0.5 pg/20 μl of sample for each analyte. Acquisition and analysis of chromatograms were performed using a Star Chromatography Workstation (Varian, Walnut Creek, CA). Dialysate DA, NE, and DOPAC concentrations were immediately assayed. Tissue of the left and right mPFC of each rat was analyzed separately and data from the two hemispheres were then used to calculate average catecholamine concentrations in individual subjects.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using ANOVA. In the case of repeated measures ANOVAs, degrees of freedom were adjusted in accordance with the Huynh-Feldt F-test [27]; adjusted degrees of freedom are reported. Post hoc analyses of the contribution of individual means to a significant ANOVA was determined using t tests with a layered Bonferroni correction of p values for multiple comparisons [10]. Unadjusted t tests were used only for analysis of planned comparisons of mPFC tissue catecholamine concentrations following local 6-OHDA, as predicted based on our previously published findings [7]. The accepted level of significance for all ANOVAs and t tests was p≤0.05. Unless indicated as not significant (ns), all F and t values reported in the results section are significant at the p≤0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of early 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC on local tissue and extracellular DA and NE concentrations

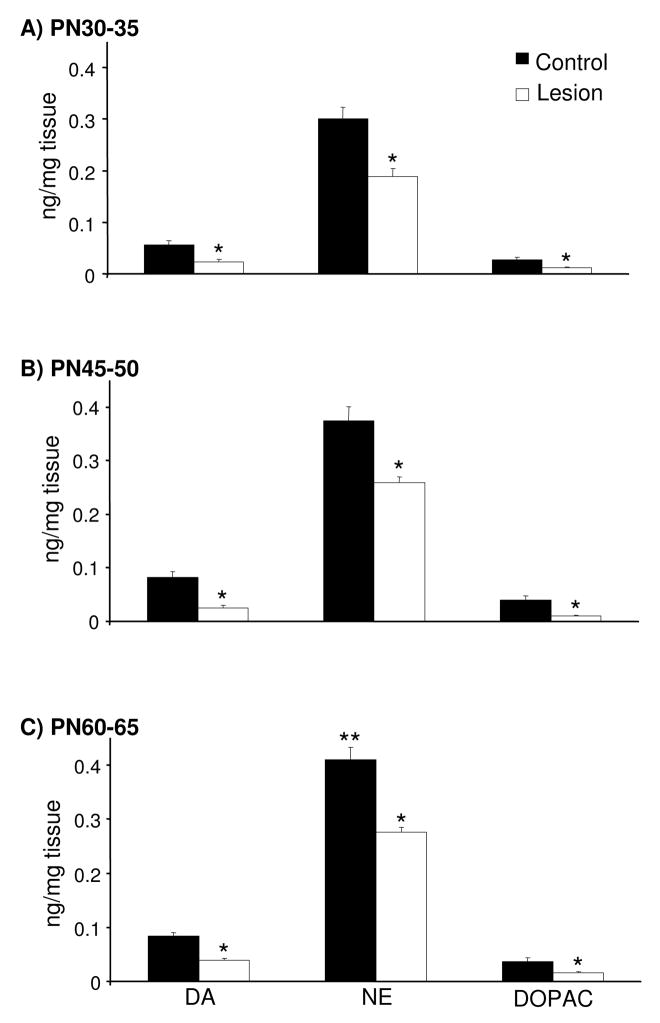

Local infusions of 6-OHDA on PN12-14 decreased mPFC tissue DA and DOPAC concentrations by ~50% in rats subjected to microdialysis testing on PN30-35, 45-50, or 60-65 [Fig. 1; t(10)=2.6 and 2.2, t(14)=5.1 and 4.6, and t(15)=6.6 and 3.2, respectively]. Tissue NE concentrations were also decreased by ~25% in the mPFC of these rats tested on PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 [Fig. 1; t(10)=2.4, t(14)=4.4, and t(15)=5.8, respectively]. In control and lesioned rats, tissue catecholamine concentrations in the rat mPFC varied as a function of normal development [Fig. 1: F(2,21)=5.5]. Specifically, tissue NE concentrations were higher in PN60-65 control and lesioned rats relative to treatment-matched rats tested on PN30-35 [t(13) = 3.38 and t(12) = 3.15]. A similar trend was observed for tissue DA concentrations [F(2,21)=3.2, ns].

Figure 1.

Tissue DA, NE, and DOPAC concentrations in the mPFC of PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 control rats and rats previously sustaining local 6-OHDA infusions on PN12-14 (panels A, B, and C, respectively; n=5–9/group). Local 6-OHDA decreased mPFC tissue DA and DOPAC concentrations by ~50% and NE by ~25% relative to age-matched control rats. Tissue NE concentrations were increased in PN60-65 control and lesioned rats relative to treatment-matched PN30-35 rats. Data are presented as group mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from age-matched control (t tests, p≤0.05). **Significantly different from treatment-matched PN30-35 rats (t tests with layered Bonferroni correction, p≤0.017–0.05).

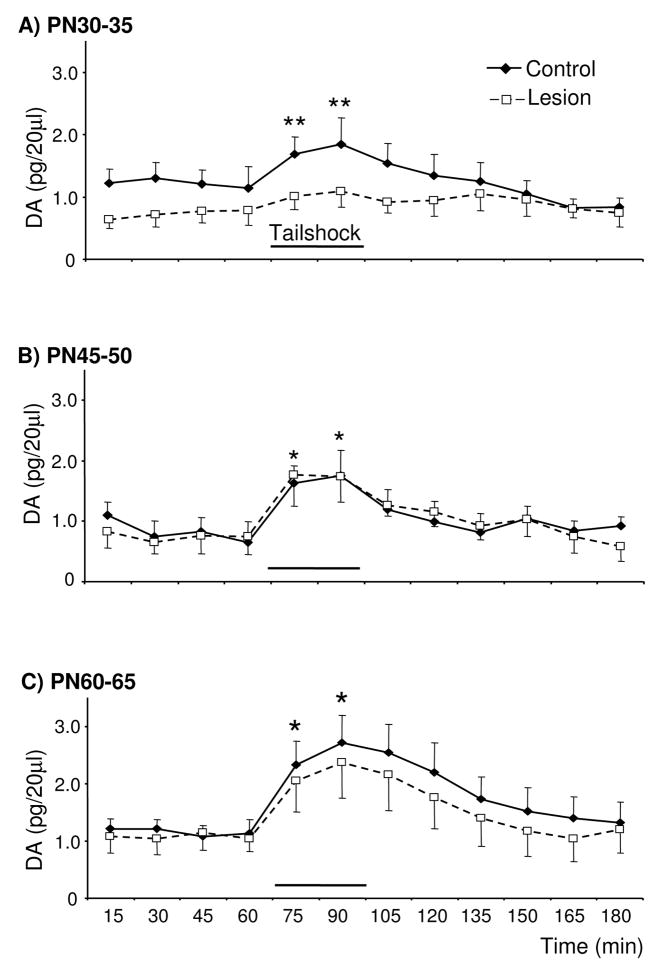

Loss of ~50% of mPFC tissue DA on PN12-14 did not significantly affect local basal extracellular DA concentrations in PN30-35, 45-50, or 60-65 rats (Fig. 2). Lesioned rats tested on PN30-35 did exhibit a trend for decreased basal extracellular DA relative to age-matched controls. In addition, tailshock failed to increase extracellular DA in the mPFC of PN30-35 lesioned-rats, whereas evoked increases were observed in age-matched controls [Fig. 2A; Time × Group: F(5,49)=2.4; pairwise comparisons of PN30-35 control at time 60 versus 75 and 90: t(5)=3.5 and 3.4, respectively]. In contrast, similar evoked increases in extracellular DA were observed in lesioned and age-matched control rats tested on PN45-50 and 60-65 [Fig. 2B&C, respectively; Time: F(4,29)=8.6 and F(4,36)=15, respectively; pairwise comparisons of PN45-50, collapsed across treatment condition, at time 60 versus 75 and 90: t(9)=3.8 and 5.0, respectively; pairwise comparisons of PN60-65, collapsed across treatment condition, at time 60 versus 75 and 90: t(11)=5.1 and 5.4, respectively]. In control rats, basal extracellular DA did not vary as a function of age, however there was a trend for greater stress-evoked increases in extracellular DA concentrations in the mPFC of PN60-65 than PN30-35 or PN45-50 rats [F(2,14)=1.5, ns; 2.4±0.1 versus 1.7±0.2 and 1.8±0.1 pg/20 μl, respectively].

Figure 2.

Basal and tailshock-evoked extracellular DA concentrations in the mPFC of control rats and rats previously sustaining partial loss of tissue mPFC DA and NE (~50 and 25%, respectively) on PN12-14 and subsequently tested on PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 (panels A, B, and C, respectively; n=5–6/group). Relative to age-matched controls, PN30-35 lesioned rats exhibited a trend for lower basal and evoked extracellular DA. Tailshock increased extracellular DA in PN30-35 control rats, but not lesioned rats. Basal and evoked extracellular DA concentrations in the mPFC of PN45-50 and 60-65 lesioned rats did not differ from age-matched controls. Tailshock increased extracellular DA in the mPFC of lesioned and control rats tested on PN45-50 and 60-65. Data are presented as group mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from baseline sample immediately preceding tailshock, collapsed across treatment condition (t tests with layered Bonferroni correction, p≤0.006–0.05). **Significantly different within-group baseline sample immediately preceding tailshock (t tests with layered Bonferroni correction, p≤0.006–0.05).

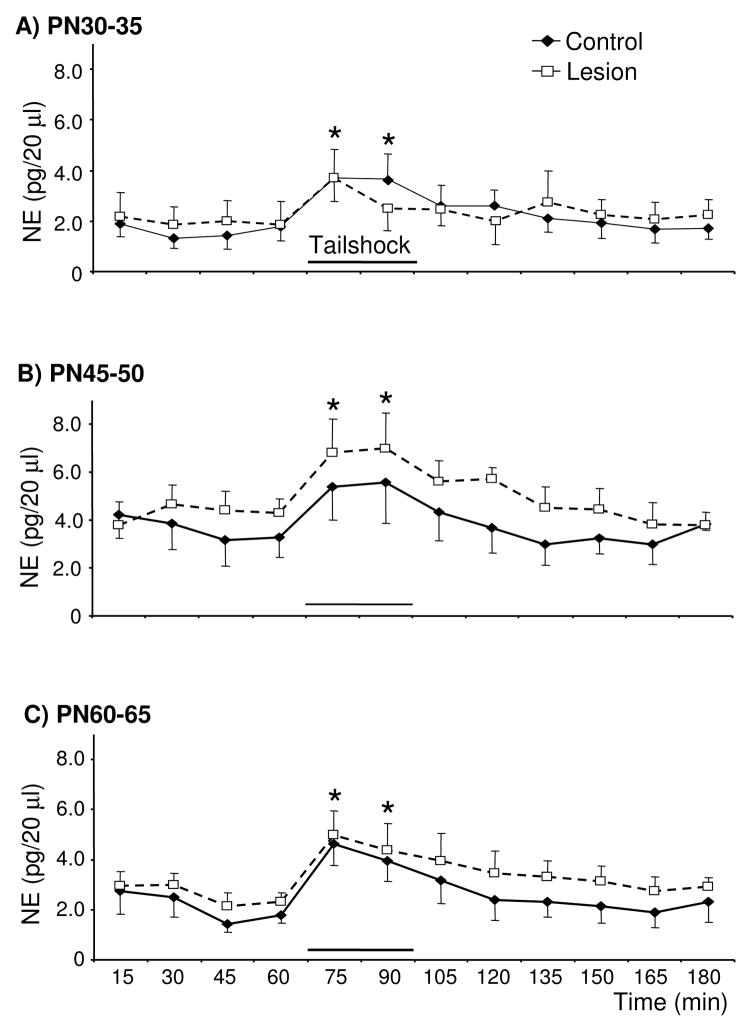

Despite the loss of ~25% of tissue NE concentrations in the mPFC of lesioned rats, basal extracellular NE concentrations on PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 did not differ from age-matched controls (Fig. 3). Tailshock increased extracellular NE in PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 lesioned- and control-rats and this effect did not vary as a function of treatment condition [Time: F(7,50)=8.7, F(4,36)=8.4, and F(4,36)=9.0, respectively]. Relative to the last baseline sample, extracellular NE was increased during the first and second 15 min of stress in rats tested on PN30-35 [t(8)=4.8 and 4.7, respectively], PN45-50 [t(9)=3.8 and 3.2, respectively], and PN60-65 [t(11)=5.7 and 3.9, respectively]. In control rats, basal and stress-evoked extracellular NE concentrations in the mPFC did not vary as a function of age.

Figure 3.

Basal and tailshock-evoked extracellular NE concentrations in the mPFC of control rats and rats previously sustaining partial loss of mPFC DA and NE (~50 and 25%, respectively) on PN12-14 and subsequently tested on PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 (panels A, B, and C, respectively; n=5–6/group). Basal and stress-evoked extracellular NE concentrations in the mPFC of lesioned rats did not differ from age-matched controls. Tailshock increased extracellular NE in the mPFC of PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 rats. Data are presented as group mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from baseline sample immediately preceding tailshock, collapsed across treatment condition (t tests with layered Bonferroni correction, p≤0.006–0.05).

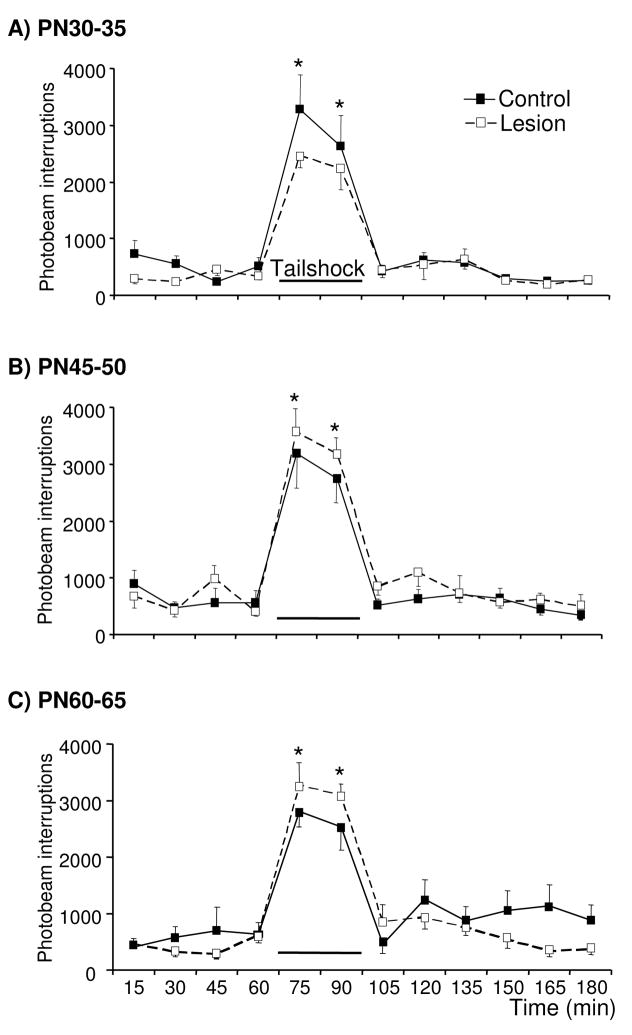

3.2. Effects of early 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC on horizontal locomotor activity in juvenile, adolescent, and adult rats

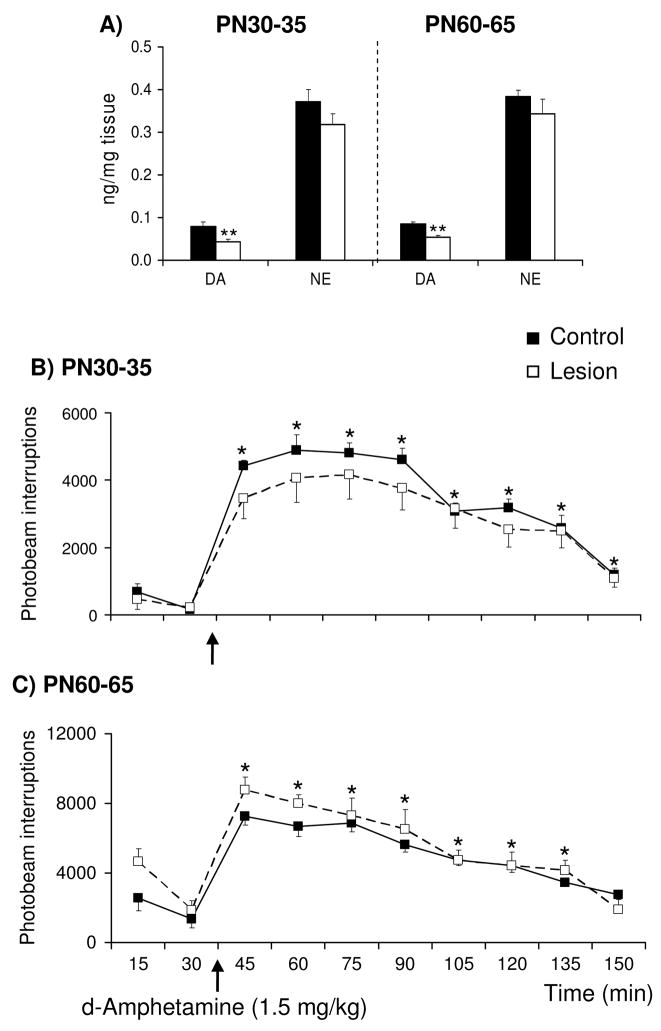

Basal and stress-evoked horizontal locomotor activity was monitored simultaneous with analysis of extracellular DA and NE concentrations in the mPFC of control and lesioned rats. Basal and tailshock-evoked activity were similar in lesioned rats tested on PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 relative to age-matched controls, with all age-groups exhibiting increased activity in response to 30 min of tailshock [Fig. 4; Time: F(2,23)=25, F(6,85)=36, F(10,137)=33, respectively]. Relative to the last baseline sample, motor activity was increased in the first and second 15 min of stress in rats tested on PN30-35 [t(11)=7.6 and 6.7, respectively], PN45-50 [t(15)=8.1 and 9.3, respectively], and PN60-65 [t(14)=11 and 10, respectively]. In an independent study, d-amphetamine-evoked activity was examined in control rats and rats previously sustaining 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC on PN12-14 and subsequently tested on PN30-35 or 60-65 (in vivo microdialysis was not performed in conjunction with behavioral testing in these rats). Local 6-OHDA infusions on PN12-14 decreased mPFC tissue DA concentrations by ~40% in PN30-35 and 60-65 rats [Fig. 5A; t(10)=3.1 and t(15)=3.2, respectively]. In this experiment, lesioned rats sustained a nonsignificant (~10%) reduction in mPFC tissue NE concentrations. Differences in the DA and NE depletions across the two experiments (~50 and 25%, respectively, in the first experiment versus ~40 and 10%, respectively, in the present experiment) are likely related to the use of two 6-OHDA infusion sites per hemisphere in the first study and a single infusion site per hemisphere in the present study. Acute d-amphetamine sulfate (1.5 mg/kg, ip) increased activity in PN30-35 and 60-65 lesioned-rats and age-matched controls [Fig. 5B and C; Time: F(3,12)=79 and F(4,15)=34, respectively]; this effect did not differ as a function of treatment condition. In control and lesioned rats tested on PN30-35, motor activity was elevated at all sampling intervals following administration of amphetamine [pairwise comparisons of time 30 versus each of times 45-160, collapsed across treatment condition: t(13) = 17, 13, 14, 14, 15, 12, 9.4, and 6.3, respectively]. Similar effects of amphetamine were observed in control and lesioned rats tested on PN60-65 [pairwise comparisons of time 30 versus each of times 45-135, collapsed across treatment condition: t(16) = 8.8, 10, 7.8, 5.9, 6.2, 4.4, and 3.9, respectively]. Although not significant, it is noteworthy that lesioned rats tested on PN30-35 exhibited an attenuated response to both tailshock and amphetamine whereas those tested on PN60-65 exhibited an augmented response.

Figure 4.

Effects of tailshock on horizontal locomotor activity in control rats and rats previously sustaining partial loss of mPFC DA and NE (~50 and 25%, respectively) on PN12-14 and subsequently exposed to 30 min of tailshock on PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 (panels A, B, and C, respectively; n=5–9/group). The total number of photocell beam interruptions per 15-min interval was determined for each rat. Tailshock evoked similar increases in motor activity in PN30-35, 45-50, and 60-65 lesioned and age-matched control rats. Each point represents the group mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from the baseline sample immediately preceding tailshock, collapsed across treatment condition (t tests with layered Bonferroni correction, p≤0.006–0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of d-amphetamine sulfate (1.5 mg/kg, i.p.) on horizontal locomotor activity in control rats and rats previously sustaining 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC on PN12-14 and subsequently tested on PN30-35 or 60-65 (n=6–10/group). Local administration of 6-OHDA resulted in ~40% loss of mPFC tissue DA and no significant loss of tissue NE on PN12-14 (A) The total number of photocell beam interruptions per 15-min interval was determined for each subject. Amphetamine increased motor activity in control and lesioned rats tested on PN30-35 (B) and PN60-65 (C) and these effects did not differ as a function of treatment condition. Each point represents the group mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from the baseline sample immediately preceding d-amphetamine (t tests with layered Bonferroni correction, performed on data collapsed across treatment condition, p≤0.006–0.05). **Significantly different from age-matched control (t tests, p≤0.05).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we found that extracellular DA and NE concentrations in the intact mPFC remain relatively stable across development; an exception being a trend for acute stress-evoked increases in DA concentrations to be enhanced with age. We also observed that partial loss of mPFC DA sustained in infancy transiently decreased local extracellular DA concentrations in juvenile but not peripubescent or adult development. Previously, we reported that similar loss sustained later in development (~ late adolescence/early adulthood) results in persistent decreases in extracellular DA that extend into adulthood [47]. Together these findings suggest that a persistent hypofunction of mesoprefrontal DA neurons is most likely to occur when development of these neurons is compromised during late adolescence/early adulthood rather than early in development.

4.1. Tissue and extracellular DA and NE in the developing mPFC of control rats

To date, the normal developmental trajectory of mesoprefrontal DA neurons has been established largely by static anatomical and chemical measurements [3,6,7,9,15,22,30,42,43,44,49]. A goal of the present study was to examine whether the functional capacity of mesoprefrontal DA nerve terminals, determined by analysis of extracellular DA using in vivo microdialysis, also undergoes developmental changes from juvenescence to adulthood in the intact animal. We found that basal extracellular DA concentrations in the mPFC were similar across development, whereas acute stress tended to evoke progressively greater increases in extracellular DA as the organism matured. The latter observation is consistent with our previous data indicating that acute stress evokes greater increases in tissue DOPAC concentrations in the mPFC of adult than juvenile rats [7]. A variety of neural mechanisms could account for an apparent differential responsiveness of mesoprefrontal DA neurons as a function of development. For example, the presence of transient autoreceptor modulation of DA synthesis in the mPFC early in development may attenuate the responsiveness of mesoprefrontal DA neurons to acute environmental stimuli [2,12,45]. Alternatively, attenuated stress-evoked increases in extracellular DA in juvenile rats may be a consequence of increased clearance of released DA by neighboring NE and serotonin nerve terminals. DA, NE, and serotonin nerve terminals in adult rodents can transport and release all three monoamine neurotransmitters [17,50,53]. To our knowledge the contribution of heterologous transport and release mechanisms to regulation of extrasynaptic monoamine concentrations has not yet been examined in developing animals. However, the observation that high affinity NE uptake in rat frontal cortex decreases from PN20 to adulthood [31], is consistent with the hypothesis that attenuated stress-evoked extracellular DA in juvenile rats may be due to increased uptake of DA by NE nerve terminals at this stage of development. Given the importance of extrasynaptic signaling in normal and abnormal brain function [28,40], future research examining the factors regulating extrasynaptic monoamines in the developing organism may be critical to advancing our understanding of developmental disorders such as schizophrenia and depression. It is unlikely that developmental differences in the responsiveness of mesoprefrontal DA neurons to acute stress are due to a more general physiological characteristic of the immature state, in that acute stress-evoked increases in plasma corticosterone are similar in juvenile, adolescent, and adult rats [8].

NE fibers of the rat frontal cortex achieve an adult density and pattern of innervation by the end of the first postnatal week [31]. However, tissue NE concentrations in the rat and nonhuman primate frontal cortex increase from birth through adulthood [7,15,31]. Despite the increase in mPFC tissue NE content in adult rats, basal and acute stress-evoked mPFC extracellular NE concentrations in the present study did not vary across development. In contrast to mesoprefrontal DA neurons, mechanisms controlling extracellular NE concentrations in the rat mPFC may achieve adult characteristics early in development.

4.2. Effects of early partial loss of mPFC catecholamines on local extracellular DA and NE in the developing rat

As previously reported, local 6-OHDA on PN12-14 persistently reduced mPFC tissue DA and, to a lesser extent, NE concentrations [7]. We now report that this lesion produced a transient reduction in local basal and acute stress-evoked extracellular DA evident on PN30-35, but not PN45-50 or 60-65. Previously, we examined the functional consequences of partial loss of mPFC DA fibers in rats sustaining 6-OHDA lesions at 220–250 g [47]. In rats sustaining lesions at 220–250 g (during puberty) and subsequently tested 4 weeks later (as young adults), basal and acute stress-evoked extracellular DA concentrations were decreased following ~60% loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive (TH-IR) axons and no loss of dopamine-β-hydroxylase-immunoreactive (DβH-IR) axons in the mPFC. Together, these findings suggest that moderate loss of mPFC DA nerve terminals sustained around the time of puberty results in a persistent decrease in local basal and evoked extracellular DA concentrations, whereas these effects are only transient in rats sustaining similar loss on PN12-14. It is unlikely that a lack of effect of PN12-14 lesions on extracellular DA in rats tested on PN45-50 and 60-65 is a function of the interval between lesioning and determination of extracellular DA. In our previous study, lesions induced in 220–250 g rats resulted in decreased basal and evoked-extracellular DA concentrations measured 4 wks after the lesion; corresponding roughly to the interval between PN12-14 lesions and PN45-50 testing in the present study. Given that basal and acute stress-evoked tissue DOPAC concentrations are persistently decreased following our 6-OHDA lesion on PN12-14 [7] as well as electrolytic lesions of the ventral tegmental area on PN1[13], normalization of extracellular DA does not appear to occur by increased synthesis of DA by remaining DA nerve terminals.

A longstanding hypothesis has been that dysfunction of mesoprefrontal DA neurons leads to dysfunction of mesoaccumbens DA neurons and that, together, these abnormalities contribute to the negative and positive symptoms, respectively [16,52]. Results of experimental studies support this view in that partial loss of mesoprefrontal DA neurons sustained in late adolescent/young adult rats, disrupts DA turnover and release in the nucleus accumbens and electrophysiological activity of VTA DA neurons [11,18,25,26]. In contrast, our recent study indicates that partial loss of mesoprefrontal DA neurons sustained on PN12-14 fails to result in persistent alterations in basal and acute stress-evoked neurochemical activity of mesoaccumbens DA neurons, as determined by analysis of tissue DA and metabolite levels [7]. It may be that following partial loss of mPFC tissue DA on PN12-14, normalization of mPFC extracellular DA concentrations (as observed in the present study) is sufficient to regulate the neurochemical activity of mesoaccumbens DA neurons despite a persistent loss of mPFC tissue DA.

4.3. Effects of early partial loss of mPFC catecholamines on basal and evoked locomotor activity across development

Previously, we reported that control rats and rats sustaining 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC on PN12-14 exhibited similar horizontal locomotor activity when tested on PN30 and 60 under baseline and acute footshock conditions [7]. In the latter study, we observed that acute footshock decreased motor activity relative to a non-stressed treatment condition, raising the possibility that differences between control and lesioned rats may have been masked by a floor-effect. Therefore, in the present study we examined the behavioral effects of acute tailshock and systemic d-amphetamine, both of which increase horizontal locomotor activity [24,26]. Lesions sustained on PN12-14 did not significantly affect basal, acute tailshock-, or acute amphetamine-evoked horizontal locomotor behavior in rats tested on PN30-35, 45-50, or 60-65. Although not significant, lesioned rats tested on PN30-35 exhibited an attenuated behavioral response to acute tailshock and amphetamine, whereas those tested on PN60-65 exhibited an augmented response. The present trend for enhanced stress- and amphetamine-evoked motor behavior in adult rats previously sustaining 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC on PN12-14 is reminiscent of a significant augmentation in stress- and amphetamine-evoked motor activity observed in adult rats previously sustaining reversible or irreversible inactivation of the hippocampus as neonates [33,34]. The behavioral effects of 6-OHDA lesions of the mPFC sustained on PN12-14 differ from those observed in rats sustaining similar lesions in late adolescence/early adulthood or earlier in development. Specifically, partial loss of mPFC DA sustained during late adolescence/early adulthood attenuates acute amphetamine-evoked motor behavior in adult rats [5,24,26,41]. In addition, 6-OHDA lesions of the frontal cortex on PN7 increases basal horizontal locomotor in adulthood despite the fact that tissue DA has returned to near-normal concentrations [38]. Together these findings suggest that the behavioral consequences of partial loss of mPFC catecholamines are dependent on the developmental epoch in which the lesion is sustained.

In conclusion, results of the present study indicate that partial loss of the cortical DA innervation early in development does not result in profound alterations in basal, acute stress- or acute amphetamine-evoked local extracellular catecholamine concentrations or motor behavior in the adult. Thus, although results of biochemical and anatomical studies suggest that the activity of mesoprefrontal DA nerve fibers is decreased in adults with schizophrenia [1,19,20,21,46], this may not be due to an early developmental abnormality. Alternatively, the present findings taken together with previously published research, suggest that a persistent hypofunction of mesoprefrontal DA neurons is most likely to occur when development of these neurons is compromised during late adolescence/early adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS grant MH61616 and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Akil M, Pierri JN, Whitehead RE, Edgar CL, Mohila C, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Lamina-specific alterations in the dopamine innervation of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1580–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen SL, Dumont NL, Teicher MH. Developmental differences in dopamine synthesis inhibition by (+/−)-7-OH-DPAT. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356:173–81. doi: 10.1007/pl00005038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen SL, Thompson AT, Rutstein M, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH. Dopamine receptor pruning in prefrontal cortex during the periadolescent period in rats. Synapse. 2000;37:167–9. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200008)37:2<167::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnsten AF. Stimulants: Therapeutic Actions in ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks K, Gratton A. Possible involvement of medial prefrontal cortex in amphetamine-induced sensitization of mesolimbic dopamine function. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;282:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benes FM, Taylor JB, Cunningham MC. Convergence and plasticity of monoaminergic systems in the medial prefrontal cortex during the postnatal period: Implications for the development of psychopathology. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:1014–27. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce PJ, Finlay JM. Neonatal depletion of cortical dopamine: Effects on dopamine turnover and motor behavior in juvenile and adult rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;156:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi S, Kellogg CK. Adolescent development influences functional responsiveness of noradrenergic projections to the hypothalamus in male rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;94:144–51. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(96)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulter C, Happe H, Murrin L. Postnatal development of the dopamine transporter: A quantitative autoradiographic study. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;92:172–181. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darlington RB. Regression and Linear Models. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutch AY, CWA, Roth RH. Prefrontal cortical dopamine depletion enhances the responsiveness of mesolimbic dopamine neurons to stress. Brain Research. 1990;521:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91557-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumont NL, Andersen SL, Thompson AP, Teicher MH. Transient dopamine synthesis modulation in prefrontal cortex: in vitro studies. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;150:163–6. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feenstra M, Kalsbeek A, van Galen H. Neonatal lesions of the ventral tegmental area affect monoaminergic responses to stress in the medial prefrontal cortex and other dopamine projection areas in adulthood. Brain Research. 1992;596:169–182. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91545-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galineau L, Kodas E, Guilloteau D, Vilar MP, Chalon S. Ontogeny of the dopamine and serotonin transporters in the rat brain: an autoradiographic study. Neurosci Lett. 2004;363:266–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman-Rakic PS, Brown RM. Postnatal development of monoamine content and synthesis in the cerebral cortex of rhesus monkeys. Brain Res. 1982;256:339–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(82)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grace AA. Cortical regulation of subcortical dopamine systems and its possible relevance to schizophrenia. J Neural Transm. 1993;91:111–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01245228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gresch PJ, Sved AF, Zigmond MJ, Finlay JM. Local influence of endogenous norepinephrine on extracellular dopamine in rat medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurochem. 1995;65:111–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harden DG, King D, Finlay JM, Grace AA. Depletion of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex decreases the basal electrophysiological activity of mesolimbic dopamine neurons. Brain Res. 1998;794:96–102. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heritch AJ. Evidence for reduced and dysregulated turnover of dopamine in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:605–615. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hitri A, Casanova MF, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR, Wyatt RJ. Age-related changes in [3H]GBR 12935 binding site density in the prefrontal cortex of controls and schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;37:175–82. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00202-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn RS, Harvey PD, Davidson M, Keefe RS, Apter S, Neale JM, Mohs RC, Davis KL. Neuropsychological correlates of central monoamine function in chronic schizophrenia: relationship between CSF metabolites and cognitive function. Schizophr Res. 1994;11:217–24. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalsbeek A, Voorn P, Buijs RM, Pool CW, Uylings HB. Development of the dopaminergic innervation in the prefrontal cortex of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;269:58–72. doi: 10.1002/cne.902690105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keshavan MS, Diwadkar V, Rosenberg DR. Developmental biomarkers in schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders: common origins, different trajectories? Epidemiol Psychiatr Soc. 2005;14:188–93. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00007934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King D, Finlay JM. Effects of selective dopamine depletion in medial prefrontal cortex on basal and evoked extracellular dopamine in neostriatum. Brain Res. 1995;685:117–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00421-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King D, Finlay JM. Loss of dopamine terminals in the medial prefrontal cortex increased the ratio of DOPAC to DA in tissue of the nucleus accumbens shell: Role of stress. Brain Res. 1997;767:192–200. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King D, Zigmond MJ, Finlay JM. Effects of dopamine depletion in the medial prefrontal cortex on the stress-induced increase in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens core and shell. Neuroscience. 1997;77:141–53. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirk RE. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Science. Brooks/Cole Publishing; Pacific Grove, CA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiss JP. Theory of active antidepressants: a nonsynaptic approach to the treatment of depression. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolb B. Brain Plasticity and Behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leslie C, Robertson M, Cutler A, Bennett J. Postnatal development of D1 dopamine receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex, striatum and nucleus accumbens of normal and neonatal 6-hydroxydopamine treated rats: a quantitative autoradiographic analysis. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;62:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90195-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levitt P, Moore RY. Development of the noradrenergic innervation of neocortex. Brain Res. 1979;162:243–59. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis DA, Harris HW. Differential laminar distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive axons in infant and adult monkey prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1991;125:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90014-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipska BK, Halim ND, Segal PN, Weinberger DR. Effects of reversible inactivation of the neonatal ventral hippocampus on behavior in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2835–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02835.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipska BK, Jaskiw GE, Weinberger DR. Postpubertal emergence of hyperresponsiveness to stress and to amphetamine after neonatal excitotxic hippocampal damage: a potential animal model of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:67–75. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mana MJ, Scott S, Frame S, Luttrell IP, Boyce PJ, Finlay JM. Neonatal 6-OHDA into medial prefrontal cortex of rats impairs morris maze performance in the absence of dopamine depletions. Annual Society for Neuroscience Meeting. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojeda SR, Andrews WW, Advis JP, White SS. Recent advances in the endocrinology of puberty. Endocr Rev. 1980;1:228–57. doi: 10.1210/edrv-1-3-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press Inc.; Sydney; Orlando: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rezvani AH, Eddins D, Slade S, Hampton DS, Christopher NC, Petro A, Horton K, Johnson M, Levin ED. Neonatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the frontal cortex in rats: Persisting effects on locomotor activity, learning and nicotine self-administration. Neuroscience. 2008;154:885–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg DR, Lewis DA. Postnatal maturation of the dopaminergic innervation of monkey prefrontal and motor cortices: a tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemical analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1995;358:383–400. doi: 10.1002/cne.903580306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semyanov A. Can diffuse extrasynaptic signaling form a guiding template? Neurochem Int. 2008;52:31–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sokolowski JD, Salamone JD. Effects of dopamine depletions in the medial prefrontal cortex on DRL performance and motor activity in the rat. Brain Res. 1994;642:20–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90901-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Specht LA, Pickel VM, Joh TH, Reis DJ. Light-microscopic immunocytochemical localization of tyrosine hydroxylase in prenatal rat brain. I. Early ontogeny. J Comp Neurol. 1981;199:233–53. doi: 10.1002/cne.901990207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Specht LA, Pickel VM, Joh TH, Reis DJ. Light-microscopic immunocytochemical localization of tyrosine hydroxylase in prenatal rat brain. II. Late ontogeny. J Comp Neurol. 1981;199:255–76. doi: 10.1002/cne.901990208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarazi FI, Baldessarini RJ. Comparative postnatal development of dopamine D(1), D(2) and D(4) receptors in rat forebrain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teicher MH, Gallitano AL, Gelbard HA, Evans HK, Marsh ER, Booth RG, Baldessarini RJ. Dopamine D1 autoreceptor function: possible expression in developing rat prefrontal cortex and striatum. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;63:229–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90082-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Kammen DP, van Kammen WB, Mann LS, Seppala T, Linnoila M. Dopamine metabolism in the cerebrospinal fluid of drug-free schizophrenic patients with and without cortical atrophy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:978–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800100072010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venator DK, Lewis DA, Finlay JM. Effects of partial dopamine loss in the medial prefrontal cortex on local baseline and stress-evoked extracellular dopamine concentrations. Neuroscience. 1999;93:497–505. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verney C. Distribution of the catecholaminergic neurons in the central nervous system of human embryos and fetuses. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;46:24–47. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990701)46:1<24::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verney C, Berger B, Adrien J, Vigny A, Gay M. Development of the dopaminergic innervation of the rat cerebral cortex a light microscope immunocytochemical study using anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibodies. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1982;5:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(82)90111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vizi ES, Zsilla G, Caron MG, Kiss JP. Uptake and release of norepinephrine by serotonergic terminals in norepinephrine transporter knock-out mice: implications for the action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7888–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1506-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weickert CS, Webster MJ, Gondipalli P, Rothmond D, Fatula RJ, Herman MM, Kleinman JE, Akil M. Postnatal alterations in dopaminergic markers in the human prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2007;144:1109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia: I. Regional cerebral blood flow evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto BK, Novotney S. Regulation of extracellular dopamine by the norepinephrine transporter. J Neurochem. 1998;71:274–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]