Abstract

Owing to the increasing prevalence, patient interest, and high risk of adverse effects associated with use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), investigation of this issue in an orthopaedic population is warranted. The objectives of this study were to (1) identify the prevalence of CAM use, (2) assess the level of communication between patients and physicians regarding CAMs, (3) uncover reasons for nondisclosure, and (4) identify potentially harmful interactions between CAMs and conventional therapy. We conducted a cross-sectional observational study among patients being treated in orthopaedic surgical clinics for osteoarthritis (OA). Of the 373 participants, 42.9% reported taking one or more CAMs, and 40.6% admitted their surgeons were unaware of their alternative therapy use. Reasons for nondisclosure included, the patient thought: (1) it was not important (29.7%); (2) the surgeon would not be interested (13.5%); and (3) their surgeon would not know about CAMs (8.2%). Twenty-two of 281 patients (7.8%) were taking alternative medicines that could interact with their blood pressure medication, 28.6% were taking anticoagulant/antiplatelet medication and also taking a CAM that could interact, and 5.9% were taking conventional pain medications along with a CAM that potentially could interact. Orthopaedic surgeons should make it part of their consultation to inquire about CAM use.

Level of Evidence: Level III, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

In Canada, arthritis is one of the most common chronic conditions and is a leading cause of pain, physical disability, and use of healthcare services [3–6, 24, 30, 36]. There were approximately 58,714 total hip and knee arthroplasties performed in Canada in 2004 representing a 10-year increase of 87% and a 10% increase compared with 2003 [11]. The number of people with arthritis is expected to increase to 6.5 million by 2031 [5].

The term complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) encompasses many alternative therapies such as dietary supplements, herbs, megavitamins, homeopathic medicines, acupuncture, and numerous other modalities [17]. The National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAMs as a group of medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that currently are not considered part of conventional medicine [33].

CAMs currently are not regulated in North America. In Canada, they are referred to as natural health products and although they are in the process of becoming regulated, regulation will not be fully completed until 2010 [17]. Similarly, in the United States, CAMs are regulated as dietary supplements by the Food and Drug Administration, a category that does not require proof of safety by the manufacturer before marketing but is not permitted to make treatment-cure claims [44]. A recent study by Health Canada reported 71% of Canadians regularly take a natural health product [16].

CAMs can cause potential harmful interactions or side effects with conventional treatments [35, 38, 42, 46]. These include serious complications with anesthesia during surgery [18, 35, 43], an increase or decrease in heart rate and/or blood pressure [25, 26, 32, 34], harmful interactions if used concomitantly with anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications [7, 8, 10, 28, 37, 40], and certain herbal medications can produce harmful effects in patients taking NSAIDs or prescription pain medications [20, 21, 43, 45]. Many physicians are poorly informed about alternative therapies [2, 27]. Studies suggest greater than half of orthopaedic surgeons are unaware of their patients’ CAM use [13, 27], and approximately 60% of patients who use CAMs do not disclose this information to their primary care providers [27, 38]. With the aging population, the increasing incidence of OA, the use of CAMs in this population, and the potential for serious adverse events when CAMs interact with traditional medications, physicians need to inquire and understand CAMs, to provide optimal patient care.

As a result of the increasing prevalence, patient interest, and high risk of adverse effects associated with CAM use, the primary objective of our study was to identify the prevalence of CAM use among patients with OA. The secondary objectives were to assess the level of communication between patients and physicians regarding CAM use, identify reasons for physician disclosure or nondisclosure, and identify any potentially harmful interactions related to CAM use and simultaneous conventional therapy.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study among patients being treated for OA across three university-affiliated orthopaedic surgery clinics in Ontario, during a 1-year period (2004–2005). Eligible study participants were at least 16 years of age and able to read and write in English. We excluded patients if they did not have the cognitive capacity to provide consent for participation or were attending the clinic for treatment not related to OA.

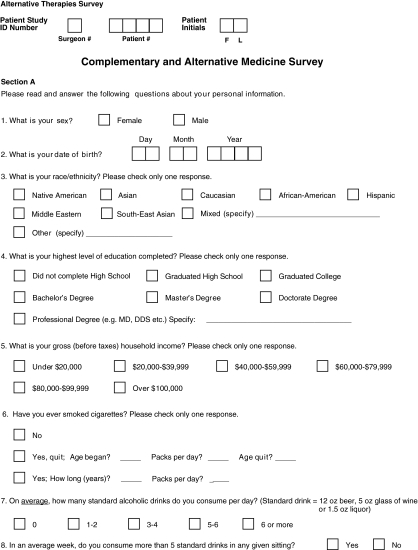

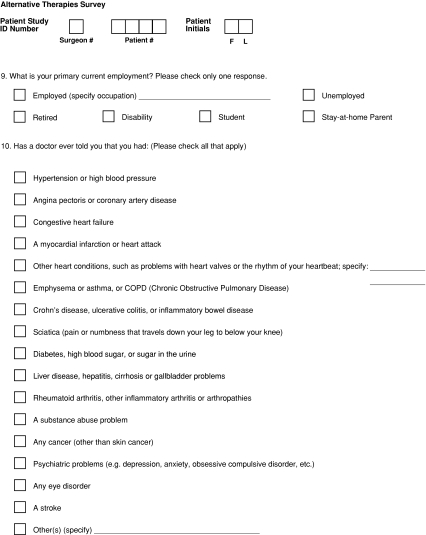

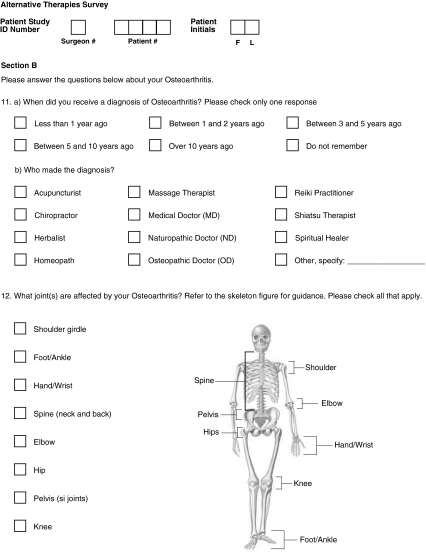

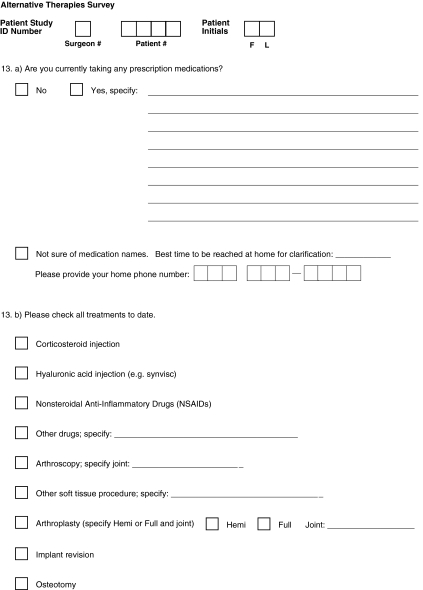

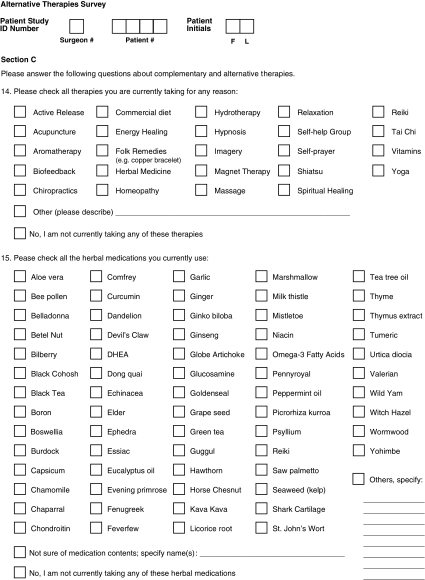

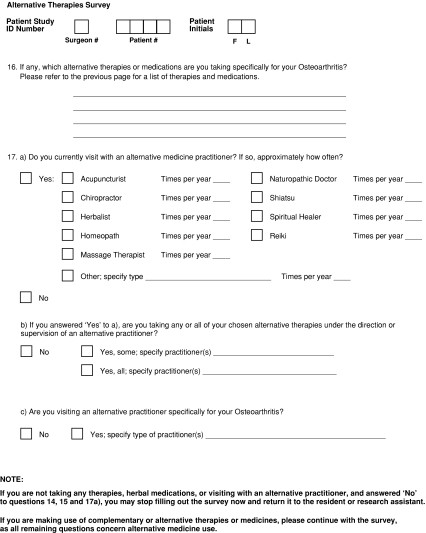

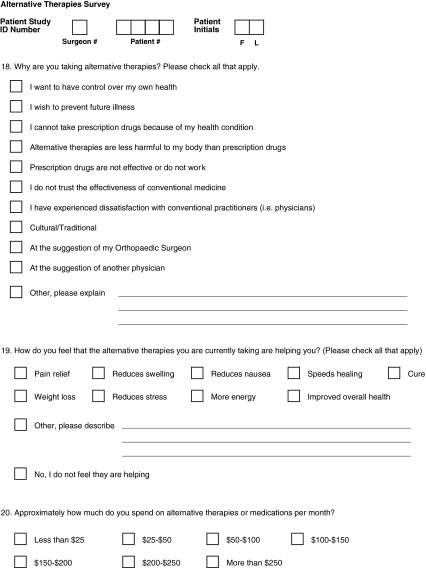

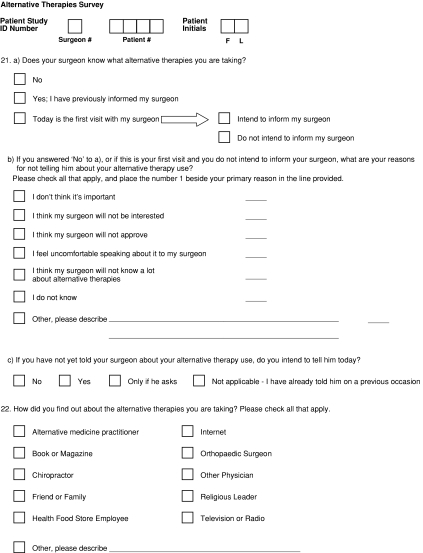

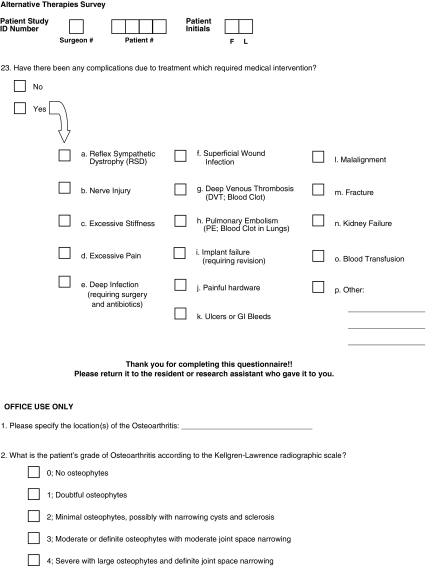

We designed a survey consisting of closed-ended, multiple-choice, and fill-in-the-blank questions (Appendix 1). The questionnaire consisted of five sections: (1) demographic information; (2) general information about the patient’s OA; (3) prevalence of and reasons for the use of CAMs and amount of money spent each month on CAMs; (4) a detailed list of the patient’s prescription medications; and (5) detailed information regarding the patient’s OA (this section completed by the orthopaedic surgeon). Questionnaire items were generated by reviewing the literature, searching naturopathy and holistic Internet web sites, and contacting experts in naturopathy, holistic medicine, and orthopaedic surgery. We used a “sample to redundancy” strategy by which we contacted experts until no new items for the questionnaire emerged. We pretested the questionnaire with an independent group of 10 community members and three orthopaedic surgeons to ascertain whether the survey adequately addressed CAM use among patients with OA. The community members and orthopaedic surgeons also assessed the clarity and comprehensiveness of the items contained in the questionnaire.

The research assistant approached patients, who either were existing patients of the surgeon with a confirmed diagnosis of OA or were new patients referred to the surgeon for suspicion of OA, while they were in the waiting room for consultation with the orthopaedic surgeon. On completion of the consultation, the surgeon documented the severity of OA. After providing informed consent, patients were asked to complete the survey while waiting for their consultation. The research assistant was available to answer questions, check for completeness, and clarify any uncertain, illegible, or confusing responses with the patient, and then collect the completed surveys. If patients were uncertain about any of the CAMs or prescription medications they were taking, the research assistant called them at home and completed these sections over the phone.

To determine sample size, we assumed, based on reported findings, approximately 30% of patients surveyed would be CAM users. We wanted to have sufficient power to provide a 95% confidence interval with a width of no more than 5% around our estimate of CAM use. According to our calculation, 320 completed questionnaires were needed to have sufficient certainty regarding our estimate of CAM use.

We approached 422 patients; 373 (88.3%) patients completed the survey; there were 219 female and 154 male patients with a mean age of 63 years. The majority of participants were white (81.9%), had a high school education or greater (71.6%), and currently were retired (58%). Approximately half of the participants (52.8%) had OA greater than 5 years with the most common joint affected being the knee (84.7%), followed by the hip and pelvis (43.5%), and the hand, wrist, or elbow (40.9%) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Proportion (N = 373) |

|---|---|

| Males | 154 (41.4%) |

| Age (years) | 63.2 ± 12.1 |

| (range, 25.0–90.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity | N = 359 |

| White | 294 (81.9%) |

| Asian | 3 (0.8%) |

| Black | 2 (0.6%) |

| Native American | 19 (5.3%) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (0.3%) |

| Other | 37 (11.1%) |

| Education | N = 366 |

| Did not complete high school | 104 (28.4%) |

| High school graduate | 110 (30.1%) |

| College diploma or Bachelor’s degree | 117 (32.0%) |

| Masters, Doctorate, or professional degree | 35 (9.6%) |

| Gross income | N = 307 |

| Less than $20,000 | 59 (19.2%) |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 77 (25.1%) |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 76 (24.8%) |

| $60,000–$79,999 | 48 (15.6%) |

| Over $80,000 | 47 (15.3%) |

| Smoking status | N = 369 |

| Never smoked | 165 (44.7%) |

| Smoked, but quit | 158 (42.8%) |

| Current smoker | 46 (12.5%) |

| Employment status | N = 371 |

| Retired | 215 (58.0%) |

| Employed | 108 (29.1%) |

| Disability | 33 (8.9%) |

| Stay-at-home parent | 8 (2.2%) |

| Unemployed/student | 7 (1.9%) |

| Comorbidities | N = 373 |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Hypertension | 179 (48.0%) |

| Angina/heart disease | 26 (7.0%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 9 (2.4%) |

| Other heart condition | 43 (11.5%) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 16 (4.3%) |

| Previous stroke | 63 (16.9%) |

| Asthma/emphysema | 41 (11.0%) |

| Sciatica | 72 (19.3%) |

| Diabetes | 53 (14.2%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 158 (42.4%) |

| Any cancer | 34 (9.1%) |

| Depression/anxiety | 69 (18.5%) |

| Other | 81 (21.7%) |

Table 2.

Participant characteristics associated with OA

| OA characteristic | Proportion |

|---|---|

| Duration of OA | N = 363 |

| Less than 1 year | 24 (6.6%) |

| 1–5 years | 129 (35.6%) |

| Longer than 5 years | 192 (52.8%) |

| Do not remember | 18 (5.0%) |

| Joint affected by OA | N = 366 |

| Knee | 310 (84.7%) |

| Hip/pelvis (sacroiliac joints) | 159 (43.5%) |

| Hand/wrist/elbow | 150 (40.9%) |

| Spine (neck and back) | 105 (28.7%) |

| Shoulder girdle | 98 (26.8%) |

| Foot/ankle | 78 (21.3%) |

| Grade OA* | N = 319 |

| 0 = no osteophytes | 8 (2.5%) |

| 1 = doubtful osteophytes | 10 (3.1%) |

| 2 = minimal osteophytes | 79 (24.8%) |

| 3 = moderate osteophytes | 86 (27.0%) |

| 4 = severe, large osteophytes | 136 (42.6%) |

| Previous treatments for OA | N = 351 |

| Arthroplasty | 190 (54.1%) |

| NSAIDs | 180 (51.3%) |

| Corticosteroid injection | 145 (41.3%) |

| Arthroscopy (knee scope) | 135 (38.5%) |

| Hyaluronic acid injection | 70 (19.9%) |

| Other medications | 66 (18.8%) |

| Osteotomy | 15 (4.3%) |

| Soft tissue procedure | 13 (3.7%) |

*According to the Kellgren-Lawrence radiographic scale.

The primary analysis was descriptive. We calculated the proportion of patients using CAMs with a 95% confidence interval around this estimate. Secondary analyses included the relative frequency of reasons for patients not disclosing CAM use to their physicians, the percentage of patients who disclose CAM use to their physicians, the frequency of the persons or places that referred them to CAMs, and frequency of patients who are using CAMS that may be harmful given their condition.

Results

Of the 373 patients, 157 (42.9%; 95% CI, 37.9–48.0%) reported taking one or more CAMs, of which 19.8% (95% CI, 16.0–24.2%) said they currently visit with an alternative medicine practitioner (Table 3). Of those, 26.5% were taking an herbal medication specifically for their OA, and 6.8% (95% CI, 4.4–10.0%) visit an alternative practitioner to treat their OA. Seven people did not respond to this question. The majority of patients (83%) had been diagnosed with OA by a medical doctor (the remaining patients were diagnosed by an osteopathic doctor [12.8%], chiropractor [1.7%], or massage therapist [0.3%]). All patients who were taking CAMs specifically to treat their OA reported previously trying some form of conventional treatment. The three most common treatments included NSAIDs (53%), arthroscopy (43%), and arthroplasty or total joint arthroplasty (38%). The most popular CAMs taken by patients in the study were glucosamine (28.7%), chondroitin (16.1%), and omega-3 fatty acids (10.4%) (Table 4). The majority of people spent less than $25 per month on alternative medications (45.4%), whereas 25.9% spent $25 to $50 per month, 15.7% spent $50 to $100 per month, and 12.9% reported spending greater than $100 per month. The most common reasons for taking CAMs were to have control over their own health and to prevent future illness (Table 5).

Table 3.

Prevalence of CAM practitioner use

| Practitioner | Proportion, N = 363 |

|---|---|

| Acupuncturist | 3.0% |

| Chiropractor | 11.8% |

| Herbalist | 0.8% |

| Homeopath | 0.6% |

| Massage therapist | 9.1% |

| Naturopathic Doctor | 1.1% |

| Shiatsu | 0.3% |

| Spiritual healer | 0.3% |

| Reikic | 0.3% |

Table 4.

Prevalence of CAM use in our sample

| CAM | Proportion | CAM | Proportion | CAM | Proportion | CAM | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloe vera | 2.7% | Devil’s claw | 0.8% | Glucosamine | 28.7% | Reiki | 0.5% |

| Bee pollen | 1.1% | DHEA | 0.5% | Goldenseal | 0.0% | Saw palmetto | 2.5% |

| Belladonna | 0.3% | Dong Quai | 0.5% | Grape seed | 0.8% | Seaweed | 0.8% |

| Betel nut | 0.0% | Echinacea | 3.8% | Green tea | 7.1% | Shark cartilage | 2.2% |

| Bilberry | 0.5% | Elder | 0.0% | Guggul | 0.0% | St. John’s wort | 1.1% |

| Black cohosh | 0.5% | Ephedra | 0.0% | Hawthorn | 0.8% | Tea tree oil | 1.9% |

| Black tea | 2.7% | Essiac | 0.0% | Horse chestnut | 0.0% | Thyme | 0.3% |

| Boron | 0.3% | Eucalyptus oil | 0.5% | Kava kava | 0.3% | Thymus extract | 0.0% |

| Boswellia | 0.0% | Evening primrose | 1.4% | Licorice root | 0.5% | Tumeric | 1.1% |

| Burdock | 0.0% | Fenugreek | 0.0% | Marshmallow | 0.0% | Urtica diocia | 0.0% |

| Capsicum | 0.3% | Feverfew | 0.0% | Milk thistle | 0.8% | Valerian | 0.0% |

| Chamomile | 2.2% | Fish oil | 0.0% | Mistletoe | 0.8% | Vitamin E | 1.1% |

| Chaparral | 0.0% | Flax | 1.6% | Niacin | 0.5% | Wild yam | 0.3% |

| Chondroitin | 16.1% | Garlic | 8.7% | Omega-3 fatty acids | 10.4% | Witch hazel | 0.0% |

| Coenzyme Q10 | 0.5% | Ginger | 2.2% | Pennyroyal | 0.0% | Wormwood | 0.0% |

| Comfrey | 0.0% | Ginkgo biloba | 3.3% | Peppermint oil | 0.5% | Yohimbe | 0.0% |

| Curcumin | 0.5% | Ginseng | 2.7% | Picrorhiza kurroa | 0.0% | Other | 9.8% |

| Dandelion | 0.0% | Globe artichoke | 0.0% | Psyllium | 1.4% |

Table 5.

Patients’ reasons for taking CAM

| Reason | Proportion N = 181 |

|---|---|

| I want to have control over my own health | 79 (43.6%) |

| I want to prevent future illness | 65 (35.9%) |

| Alternative therapies are less harmful to my body than prescription drugs | 33 (18.2%) |

| At the suggestion of another physician (not orthopaedic surgeon) | 33 (18.2%) |

| At the suggestion of my orthopaedic surgeon | 23 (12.7%) |

| Prescription drugs are not effective or do not work | 13 (7.2%) |

| I cannot take prescription drugs because of my health condition | 8 (4.4%) |

| I have experienced dissatisfaction with conventional practitioners (ie, physicians) | 7 (3.9%) |

| I do not trust the effectiveness of conventional medicine | 4 (2.2%) |

| Cultural/traditional | 1 (0.6%) |

| Other | 66 (36.5%) |

Of the 192 patients who responded to the question asking whether they had communicated CAM use to their healthcare providers, 78 (40.6%; 95% CI, 33.9–47.7%) admitted their surgeon was not aware of which alternative therapies they currently were taking. Thirty-three of these patients (21.2%) said they would inform the surgeon only if he or she asked them. However, 21 patients (10.9%) were seeing the orthopaedic surgeon for the first time, of which 92.3% reported they intended to inform the surgeon of their alternative medicine use that day.

Reasons for not disclosing information about CAM use to the surgeon were the patient thought (1) it was not important (29.7%), (2) the surgeon would not be interested (13.5%), and (3) their surgeon would not know about alternative medicines (8.2%).

Two hundred eighty-one patients were taking prescription medications. More than half of these patients (56.6%) were taking prescription medications for a heart condition. Twenty-two of the 281 patients (7.8%) were taking an alternative medicine that interacts with their blood pressure medication, a combination that has been noted to increase heart rate and blood pressure [43], therefore making the prescription drug less effective. Forty-nine of the 281 patients (17.4%) were taking anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications, of which 14 patients (28.6%) simultaneously were taking a natural health product that would affect their international normalized ratio (INR) and/or platelet function [43]. Eight of the 14 patients (57.1%) had a previous myocardial infarction or stroke, placing them at an even greater risk of having an additional heart attack or stroke in the future. Among the 169 patients (60.5%) taking conventional pain medications, 10 (5.9%) also were taking an interacting CAM. Eight of the 10 patients were taking ginkgo biloba, one was taking bee pollen, and the other was taking glucosamine, all simultaneously with an NSAID or pain killer. In all 10 cases, the combination of the pain medication with the CAM has the potential to make the prescription drug less effective [43].

Discussion

Owing to the increasing popularity of complementary and alternative medicines, and evidence suggesting CAM use potentially can cause harmful interactions or side effects with conventional treatments [35, 38, 42, 46], this study addressed the prevalence of CAM use among patients with OA. Secondary objectives were to assess the level of communication between patients and physicians regarding CAM use, uncover reasons for physician disclosure or nondisclosure, and identify any potentially harmful interactions related to CAM use and simultaneous conventional therapy.

Our study is limited as we do not know the proportion of patients surveyed who actually experienced an adverse reaction or complication while simultaneously taking an herb with a prescription medication. Although we cannot be certain if any of the patients have experienced or will experience these complications, we do know they are at an increased risk of having such an adverse event in the future. In addition, the use of CAMs was self-reported, and therefore has not been validated. Also, our study included a predominantly white population, which may not be representative of populations in other practices. A national survey reported the prevalence of CAM use is equally common among white, black, Latino, Asian, and Native American populations [29]. One previous study also suggested variation in CAM use among different ethnic groups. After controlling for other variables, Katz and Lee found whites and Hispanics were considerably less likely to use CAM therapy than blacks [23]. Finally, the list of herbal medications we provided to patients was not exhaustive. There are numerous alternative medications that potentially could interact with prescription medications, and although no participants in this study reported taking other CAMs, these potentially dangerous herbs are available to patients. Although the study design used a convenience sample, and therefore limited the generalizability of the results, a strength of this study is it was a large, multicenter survey, which included patients with a broad spectrum of OA severity.

Our data suggest 42.9% of patients with OA, who were being treated by an orthopaedic surgeon, used some form of CAM. However, many physicians remain poorly informed regarding alternative therapies and therefore avoid discussing CAM use with their patients [2, 27]. Two studies suggest greater than half of orthopaedic surgeons are unaware of their patients’ CAM use [13, 27], and approximately 60% of patients who use CAMs do not disclose this information to their primary care providers [27, 38]. Similarly, 78 (40.6%) of our study patients admitted their orthopaedic surgeon was not aware of which alternative therapies they currently were taking. Unfortunately, this lack of communication may put the patient at an increased risk of side effects. Despite the purported benefit offered by some alternative medicines, occasionally the use of these products can cause harmful interactions or side effects with conventional treatments [35, 38, 42, 46].

Complementary and alternative medicines also may cause harmful interactions with prescription medications, particularly among patients taking medications for heart conditions. In our study, 56.6% of patients taking medication for a heart condition also were taking a CAM that potentially could interact with that medication (Table 6) [43]. When taken concurrently with prescription medications, some CAMs either can increase or decrease heart rate and/or blood pressure, which could progress to a myocardial infarction or stroke [25, 26, 32, 34], and therefore should not be taken by patients receiving blood pressure medication or with a history of cardiac problems.

Table 6.

Important interactions between prescription medications and CAMs

| Heart/Blood pressure | Anticoagulant/Antiplatelet | NSAIDs/Pain |

|---|---|---|

| Belladonna | Alfalfa | Beeswax |

| Black tea* | Capsicum | Bee pollen |

| Capsicum | Coenzyme Q10 | Boron |

| Chromium* | Chondroitin | Chromium |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Devil’s claw | Ginkgo biloba |

| Devil’s claw | Dong Quai | Licorice root |

| DHEA† | Evening primrose | St. John’s wort |

| Ginger | Fenugreek | |

| Ginkgo biloba‡ | Fish oil | |

| Ginseng | Flax | |

| Green tea§ | Garlic | |

| Hawthorne§ | Ginger | |

| Kava kava | Ginkgo biloba | |

| Licorice root | Ginseng | |

| Mistletoe | Glucosamine | |

| St. John’s wort | Grape seed | |

| Green tea | ||

| Saw palmetto | ||

| St. John’s wort | ||

| Tumeric | ||

| Vitamin E |

* May be most problematic with beta blockers; †may be most problematic with calcium channel blockers and angiotensin II receptor antagonists; ‡may be most problematic with beta blockers and calcium channel blockers; §may be most problematic with calcium channel blockers.

Some CAMs also are capable of producing arrhythmias [43] that can cause blood clots to pool in the heart. If these clots are passed through the heart or to the brain, a heart attack or stroke may result. Still other herbs like ginseng may cause elevated blood pressure as a side effect, negating the effects of some antihypertensives [12, 30, 43]. One case report deemed ginseng responsible for reducing the diuretic effect of furosemide [30]. The herbal licorice (0.5%) may elevate blood pressure, negating the effects of antihypertensive therapy [41, 43]. As a result of its mineralocorticoid activity, licorice may antagonize effects of spironolactone, minimizing its diuretic effect. Pseudoaldosteronism accompanied by weight gain, hypokalemia, hypertension, and metabolic alkalosis has been reported [30, 41, 43].

Some CAMs potentially can interact with certain liver enzymes responsible for metabolism of commonly prescribed heart and blood pressure medications [9, 14, 15, 31]. The metabolism of a drug can be altered by another drug or foreign chemical and such interactions can be clinically important. A family of enzymes called cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes are involved in the metabolism of numerous xenobiotics and in numerous interactions between drugs and food, herbs, and other drugs [9, 14, 15, 31]. The observed induction and inhibition of CYP enzymes by natural products in the presence of a prescribed drug has led to the general acceptance that natural therapies can have adverse effects. For example, Devil’s claw (used by 0.8% of our patients), ginkgo (3.3% of patients), ginseng (2.7% of patients), and St John’s wort (1.1% of patients), are substrates for CYP 2D6. These herbs specifically compete for activation and therefore time to effectiveness with medications such as beta blockers, antiarrhythmics, oxycodone, and amitriptyline [9, 14, 15, 31].

Some CAMs produce complications by interacting with anesthesia during surgery [1, 18, 19, 22, 35, 39, 43]. For example, glucosamine, used by 28.7% of study participants, should be stopped 2 to 3 weeks before surgery because it may lead to fainting and delayed recovery after anesthesia [18, 43]. Other CAMs being taken by patients in our study should be stopped 2 to 3 weeks before surgery to avoid complications [18, 43], including myocardial infarction, stroke, bleeding, inadequate oral anticoagulation, prolonged or inadequate anesthesia, organ transplant rejection, and interference with medications crucial for patient care [18, 35, 43], like chondroitin (16.1%), echinacea (3.8%), ginkgo biloba (3.3%), ginseng (2.7%), and garlic supplements (8.7%). St John’s wort, which was used by four patients in this study, can cause cardiovascular collapse during anesthesia [18, 43], and evening primrose oil, taken by six patients in this study, also has the potential to interact with anesthesia during surgery [18, 43].

In addition, certain CAMs can cause harmful interactions as a result of being used concomitantly with anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications [7, 8, 10, 28, 37, 40]. Anticoagulants prevent the production of vitamin K-producing factors that are involved in the formation of blood clots. These medications are responsible for normalizing the INR. Coenzyme Q10 (used by 0.5% of our patients), for example, is chemically similar to vitamin K and promotes clotting [43]. Antiplatelets, like aspirin and Plavix (Sanofi-Aventis Canada Inc, Laval, Quebec, Canada), however, work by preventing platelets in the blood from clumping together. Garlic (used by 8.7% of our patients) increases the side effects of antiplatelets, including ulcers in the stomach, abdominal pain, ringing in the ears, and hemorrhagic stroke [7, 8, 10, 28, 37, 40, 43].

Finally, certain herbal medications can produce harmful effects in patients taking NSAIDs or prescription pain medications. For example, St John’s wort (1.1% of our patients), an herb commonly taken for depression, can interact with narcotic pain killers [43] such as Percocet (Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada Inc, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), OxyContin (Purdue Pharma, Pickering, Ontario, Canada), or Tylenol #3 (Janssen-Ortho, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and cause worsening of side effects such as an increase in narcotic-induced sleep time [21, 43, 45]. Although these medications typically are not prescribed for patients with OA, they commonly are prescribed postsurgery and for patients with severe unresponsive pain.

It also is possible for a reverse interaction to occur in which the prescription medication decreases the effect of the CAM [20, 43]. For example, glucosamine commonly is taken specifically to alleviate OA symptoms and was the most popular herb being consumed by our study patients (28.7%). However, glucosamine may be less effective in patients simultaneously taking acetaminophen [20, 43]. When acetaminophen is metabolized, it uses up sulfur, which is a requirement for glucosamine to work; therefore, simultaneous use can decrease the effect of glucosamine [20, 43].

Discontinuing herbal use also can be harmful. For example, if a patient has been taking an anticoagulant such as warfarin and an herb that interacts with warfarin, the patient’s INR will have been titrated to the desired range. This means the herb’s effect on the blood and INR already is accounted for; if the patient suddenly stops taking the herb, it consequently could result in an increased risk of bleeding and/or clots by affecting the INR.

Two of the most common CAMs used by patients in our study were glucosamine (28.7%) and chondroitin (16.1%). Pharmaceutical companies that manufacture these products claim there are no harmful interactions associated with these treatments, however, studies investigating the safety of these products were conducted over a relatively short time (16 weeks to 1 year), and therefore did not have the potential to capture any long-term adverse events [43].

Our data highlight the need for open communication regarding CAM use between patients and healthcare providers. Many patients with OA are using some form of CAM, and consequently orthopaedic surgeons and other healthcare providers should make it part of their consultation to inquire about CAM use. Many alternative medications can be helpful to patients, but they also can be extremely harmful when not taken with appropriate supervision. When using CAMs, patients need to be consistent with their consumption and keep their healthcare providers well informed of which products and medications they are taking.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jason Busse for advice regarding complementary and alternative medicines. We also thank the participating orthopaedic surgeons for allowing us access to their clinics and patients: Dr. Robert Bourne, Dr. Steven MacDonald, Dr. Doug Naudie, Dr. Richard McCalden (London Health Sciences Centre), Dr. Robert Litchfield and Dr. Robert Giffin, (Fowler Kennedy Sports Medicine Clinic), and Dr. Justin DeBeer (Hamilton Health Sciences Centre).

Appendix 1

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the reporting of this case report, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at The University of Western Ontario and McMaster University.

References

- 1.Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:208–216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Badley EM. The effect of osteoarthritis on disability and health care use in Canada. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1995;43:19–22. [PubMed]

- 4.Badley EM. The impact of disabling arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Badley EM, Rothman LM, Wang PP. Modeling physical dependence in arthritis: the relative contribution of specific disabilities and environmental factors. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:335–345. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Badley EM, Wang PP. Arthritis and the aging population: projections of arthritis prevalence in Canada 1991 to 2031. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:138–144. [PubMed]

- 7.Bloch AS. Pushing the envelope of nutrition support: complementary therapies. Nutrition. 2000;16:236–239. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J. Herbal Medicine Expanded Commission E Monographs. Newton, MA: Integrative Medicine Communications; 2000.

- 9.Budzinski JW, Foster BC, Vandenhoek S, Arnason JT. An in vitro evaluation of human cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition by selected commercial herbal extracts and tinctures. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:273–282. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Burnham BE. Garlic as a possible risk for postoperative bleeding. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:213. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Canadian Joint Replacement Registry. 2006 Report: Hip and Knee Replacements in Canada. 2006. Ottawa, ON Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); 2006. Report No: ISBN 13:978-1-55392-921-5.

- 12.DerMarderosian A, Liberti L, Beutler JA. The Review of Natural Products. 4th Ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- 13.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Foster BC, Vandenhoek S, Hana J, Krantis A, Akhtar MH, Bryan M, Budzinski JW, Ramputh A, Arnason JT. In vitro inhibition of human cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of marker substrates by natural products. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:334–342. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, Williams DK, Gentry WB, Cui Y, Ang CY. Cytochrome P450 phenotypic ratios for predicting herb-drug interactions in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:276–287. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Health Canada. Baseline natural health products survey among consumers. Available at: www.hcsc.gc.ca/dhpmps/pubs/natur/eng_cons_survey_e.html. Accessed August 7, 2007.

- 17.Health Canada. Natural health products. Available at: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodnatur/about-apropos/index_e.html.2007. Accessed August 7, 2007.

- 18.Heller J, Gabbay JS, Ghadjar K, Jourabchi M, O’Hara C, Heller M, Bradley JP. Top-10 list of herbal and supplemental medicines used by cosmetic patients: what the plastic surgeon needs to know. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:436–445; discussion 446–447. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:889–899. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hoffer LJ, Kaplan LN, Hamadeh MJ, Grigoriu AC, Baron M. Sulfate could mediate the therapeutic effect of glucosamine sulfate. Metabolism. 2001;50:767–770. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hussain MD, Teixeira MG. Saint John’s Wort and analgesia: effect of Saint John’s Wort on morphine induced analgesia. Available at: http://view.abstractonline.com/aaps.abstractViewer.asp. Accessed August 8, 2007.

- 22.Izzo AA. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: a systematic review. Drugs. 2001;61:2163–2175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Katz P, Lee F. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Berthelot JM, Le Petit C, Aghajanian J, Sayre EC, Cibere J, Anis AH, Badley EM. Descriptive epidemiology of osteoarthritis in British Columbia, Canada. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:386–393. [PubMed]

- 25.Langner E, Greifenberg S, Gruenwald J. Ginger: history and use. Adv Ther. 1998;15:25–44. [PubMed]

- 26.Langsjoen P, Langsjoen P, Willis R, Folkers K. Treatment of essential hypertension with coenzyme Q10. Mol Aspects Med. 1994;15(suppl):S265–272. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Lazar JS, O’Connor BB. Talking with patients about their use of alternative therapies. Prim Care. 1997;24:699–714. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Legnani C, Frascaro M, Guazzaloca G, Ludovici S, Cesarano G, Coccheri S. Effects of a dried garlic preparation on fibrinolysis and platelet aggregation in healthy subjects. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43:119–122. [PubMed]

- 29.Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, Hufford DJ, Johnson JC. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): a national probability survey of CAM utilizers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:50–56. [PubMed]

- 30.Mansoor GA. Herbs and alternative therapies in the hypertension clinic. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:971–975. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, Taylor RM, Ruan Y, Wang JS, Chavin KD. Effect of St John’s Wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA. 2003;290:1500–1504. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A. American Herbal Products Association’s Botanical Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1998.

- 33.National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health. CAM basics. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/helath/whatiscam/. Accessed August 8, 2007.

- 34.Newell CA, Anderson LA, Philpson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. 2nd Ed. London, England: Pharmaceutical Press; 1996.

- 35.Norred CL. Complementary and alternative medicine use by surgical patients. AORN J. 2002;76:1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Perruccio AV, Power JD, Badley EM. Arthritis onset and worsening self-rated health: a longitudinal evaluation of the role of pain and activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:571–577. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Rahman K, Billington D. Dietary supplementation with aged garlic extract inhibits ADP-induced platelet aggregation in humans. J Nutr. 2000;130:2662–2665. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Ramsey SD, Spencer AC, Topolski TD, Belza B, Patrick DL. Use of alternative therapies by older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:222–227. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Skinner CM, Rangasami J. Preoperative use of herbal medicines: a patient survey. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:792–795. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Steiner M, Lin RS. Changes in platelet function and susceptibility of lipoproteins to oxidation associated with administration of aged garlic extract. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;31:904–908. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Stewart PM, Wallace AM, Valentino R, Burt D, Shackleton CH, Edwards CR. Mineralocorticoid activity of liquorice: 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency comes of age. Lancet. 1987;2:821–824. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Tallia AF, Cardone DA. Asthma exacerbation associated with glucosamine-chondroitin supplement. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:481–484. [PubMed]

- 43.Therapeutic Research Family. Natural medicines comprehensive database. Available at: www.naturaldatabase.com. Accessed August 8, 2007.

- 44.US Food and Drug Administration. Dietary supplements. Available at: www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/supplmnt.html. Accessed August 8, 2007.

- 45.Upton R. St John’s Wort, hypericum perforatum: quality control, analytical and therapeutic monograph. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia. 1997:1–32.

- 46.Zun LS, Gossman W, Lilienstein D, Downey L. Patients’ self-treatment with alternative treatment before presenting to the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:473–475. [DOI] [PubMed]