Abstract

The antifungal and antimicrobial kutznerides, hexadepsipeptides comprised of one α-hydroxy acid and five non-proteinogenic amino acids, are remarkable examples of the structural diversity found in nonribosomally-produced natural products. They contain D-3-hydroxyglutamic acid, which is found in the threo and erythro isomers in mature kutznerides. In this study, two putative non-heme iron oxygenase enzymes, KtzO and KtzP, were recombinantly expressed, characterized biochemically in vitro, and found to stereospecifically hydroxylate the β-position of glutamic acid. KtzO generates threo-L-hydroxyglutamic acid and KtzP catalyzes the formation of the erythro-isomer bound to the peptidyl carrier protein of the third module of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase KtzH. This module has a truncated adenylation domain and is unable to activate and incorporate glutamic acid. The lack of a functional adenylation domain in the third KtzH module is compensated in trans by the stand-alone adenylation domain KtzN, which activates and transfers glutamic acid onto the carrier of KtzH in the presence of the truncated adenylation domain and either KtzO or KtzP. A method that employs non-hydrolyzable coenzyme A analogs was developed and used to determine the kinetic parameters for KtzO- and KtzP-catalyzed hydroxylation of glutamic acid bound to the carrier protein. A detailed mechanism for the in trans compensation of the truncated adenylation domain and the stereospecific hydroxyglutamic acid generation and incorporation is presented. These insights may guide the use of KtzO/KtzP and KtzN or other in trans modification/restoration tools in biocombinatorial engineering approaches.

Keywords: non-heme iron hydroxylase, NRPS, non-proteinogenic amino acids, hydroxylation, coenzyme A analogs

Introduction

A defining characteristic of secondary metabolites, in particular those produced by large multimodular nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), is their broad structural diversity.1 The origin of this diversity can be traced back to the large pool of available building blocks, which are utilized during the biosynthesis of these natural products. These building blocks include proteinogenic amino acids, fatty acids, and non-proteinogenic amino acids.2 Additional modifications,3 such as glycosylation (vancomycin,4 balhimycin5), methylation (calcium-dependent antibiotics (CDA),6,7 daptomycin7), phosphorylation (CDA),8 halogenation (syringomycin E)9 and hydroxylation (CDA,10 syringomycin E,11 viomycin12) may occur prior to, during or after assembly of the natural product and provide further structural variations. In order to understand how this complexity is generated, the enzymatic mechanisms underlying such modification reactions must be investigated. Such mechanistic insights will aid portability and reengineering efforts to incorporate tailoring enzymes into other NRPS assembly lines.

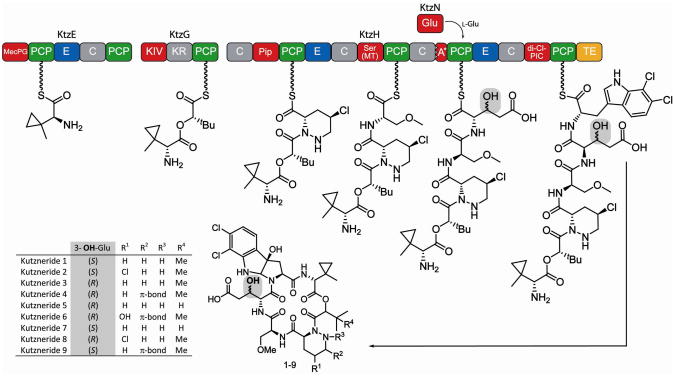

Extraordinary examples of structural diversity and the occurrence of non-proteinogenic amino acids are the antifungal and antimicrobial kutznerides 1–9 (Figure 1).13,14 These cyclic hexadepsipeptides, isolated from the soil actinomycete Kutzneria sp. 744, are comprised of five unusual non-proteinogenic amino acids and one α– hydroxy acid, and differ in the extent of substitution and stereochemistry of constituent residues.13,14 All kutznerides contain the unusual tricyclic dihalogenated (2S,3aR,8aS)-6,7,dichloro-3a-hydroxy-hexahydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole-2-carboxylic acid (PIC), followed by 2-(1-methylcyclopropyl)-D-glycine (D-MecPG), which is connected to the α-hydroxy acid moiety of either (S)-2-hydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid or (S)-2-hydroxy-3,3-dimethylbutyric acid. The hydroxy acid is followed by a D-piperazic acid (Pip) moiety found in four different forms (Figure 1). In addition, kutznerides contain O-methyl-L-serine and either the threo or erythro isomer of 3-hydroxy-D-glutamic acid (D-hGlu).

Figure 1.

Proposed biosynthesis and structures of kutznerides 1–9. Adenylation (A) domains are shown in red, peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domains in green, condensation (C) domains in grey and epimerization (E) domains in blue. The third A domain of KtzH (A*) is only 88-aa in size and nonfunctional. The thioesterase (yellow) is proposed to cleave the mature kutzneride from the assembly line by cyclization and thereby yield kutznerides 1–9. The site of glutamic acid hydroxylation is highlighted in grey. All known kutzneride species where found to contain D-β-hydroxylated glutamic acid either in the erythro (1, 2, 7, 9) or threo (3–6, 8) form.

The organization of the kutzneride NRPS assembly line is also unusual (Figure 1).15 Kutznerides are thought to be assembled by three non-ribosomal peptide synthetases, KtzE, KtzG and KtzH. KtzE is predicted to activate MecPG and catalyze its condensation with the hydroxy acid, which is activated by the adenylation (A) domain of KtzG. KtzG was shown to adenylate 2-keto-isovaleric acid (KIV) and it is postulated that after in situ reduction of the keto function by the ketoreductase domain (KR), a methyltransferase forms the t-butyl group found in many kutznerides.15 Whether the methylated hydroxy acid is transferred onto the second peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domain of KtzE prior to condensation is unclear. KtzH contains the remaining four modules needed for kutzneride assembly. The first module is predicted to activate Pip and the second to activate Ser. The A domain of module two of KtzH is also thought to be responsible for O-methylation because it contains a methyltransferase. The third module of KtzH deviates from standard NRPS logic. The A domain found in module three, designated as A*, is only approximately 20% of the size of typical A domains and thus likely to be nonfunctional. The lack of a functional amino acid activating domain in the third module may be compensated by the stand-alone A domain KtzN, which was shown to activate glutamic acid.15 Lastly, the fourth module of KtzH is predicted to incorporate the differently substituted PICs prior to cyclization by the thioesterase (TE) domain and peptide release. The presence of three epimerization (E) domains in the NRPSs agrees with the occurrence of three D-amino acids.

The presence of the threo- and erythro isomers of 3-hydroxyglutamic acid, and the first occurrence of a putative in trans compensation mechanism makes the hGlu-residue interesting from the standpoints of biosynthesis and mechanism. Investigations regarding its generation should provide insights into NRPS assembly logic extending beyond the classical linear modularity principle. Furthermore, the stereospecific hydroxylation of amino acids at the relatively unreactive β-position is a synthetic challenge. In nature, this modification is usually catalyzed by non-heme iron(II)- and α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent hydroxylases.16,17 Hydroxylation may occur during synthesis of the amino acid precursor, as for 3-hydroxyarginine12 and 3-hydroxyasparagine10 during viomycin and CDA biosynthesis, respectively, or once the amino acid is bound to a carrier protein (PCP-S-amino acid), as in syringomycin E biosynthesis.11 Hydroxylase candidates capable of introducing the OH-group at the β-position of the glutamic acid residue during kutzneride assembly have been identified previously on the gene level.15 KtzO and KtzP, the proteins encoded by these genes, exhibit the conserved HXD/E…H iron(II)-binding motif. They also show high sequence homology (53% and 49%, Supporting Information Table S1) to SyrP, the non-heme iron hydroxylase from the syringomycin E synthesis cluster, which exclusively acts on PCP-S-Asp. Thus, it is likely that KtzO and KtzP catalyze the hydroxylation of glutamic acid tethered to the third PCP domain of KtzH (PCP3-S-Glu). One or both enzymes could introduce the hydroxyl group as a racemic mixture or act stereospecifically such that one enzyme generates erythro-hGlu, found in kutznerides 1, 2, 7, 9, and the other forms threo-hGlu, found kutznerides 3–6 and 8.

In this study, the two putative non-heme iron oxygenases KtzO and KtzP were cloned and recombinantly expressed in E. coli. The enzymes were characterized biochemically in vitro and were found to catalyze the stereospecific hydroxylation of the β-position of glutamic acid bound to the PCP of the third module of KtzH. Direct kinetic measurements were determined by using non-hydrolyzable coenzyme A analogs18 where glutamic acid is bound to the PCP by an amide bond.

This study also details the first biochemical characterization of a stand-alone adenylation domain that, in trans, reconstitutes a non-functional NRPS assembly line. To provide mechanistic insights, the ability of KtzN to activate and transfer Glu was determined in the presence/absence of the truncated A* domain of KtzH and in presence/absence of the hydroxylases KtzO and KtzP. The detailed mechanism of hGlu incorporation into a natural product on truncated modules of NRPS assembly lines may aid the use of these and other modification/restoration enzymes in biocombinatorial engineering approaches to small molecule synthesis.

Experimental Section

Strains, Culture, Media and General Methods

The E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium, supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin (final concentration). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless stated otherwise. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. DNA dideoxy sequencing confirmed the identity of all constructed plasmids (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute).

Cloning of KtzN, KtzO, KtzP, A*PCP3, PCP3 and CDA-T9

The genes coding for ktzO and ktzP as well as the A*PCP3 and the PCP3 gene fragments were amplified by PCR from fosmid DNA containing the kutzneride biosynthetic cluster15 using the Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix with GC buffer (New England Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The amplification of ktzO was carried out using the oligonucleotides 5′-ktzO (5′-AAA AAA GGA TCC ATG ACG AAC TCG ACG GAC GA) and 3′-ktzO (5′-AAA AAA GCG GCC GCT CAG CGG TCG CGG TGG ACG G). The ktzP gene was amplified using the primer combination of 5′-ktzP (5′-AAA AAA GGA TCC GTG ACT GTG GAA CCC AGG CG) and 3′-ktzP (5′-AAA AAA GCG GCC GCT CAG CGG GAA TCG AGA GTC G). The gene fragment A*PCP3 coding for the A domain fragment A* and the PCP domain of the third module of ktzH, was amplified using the oligonucleotides 5′-A*PCP3 (5′-AAA AAA GGA TCC GAC CTC GCG CTG GTC GAG GC) and 3′-A*PCP3 (5′-AAA AAA GCG GCC GCT CAG TCG GCC ACC CGT GCG GCC A). For amplification of the gene fragment PCP3, coding for the third PCP domain of ktzH, the oligonucleotides 5′-PCP3 (5′-AAA AAA GGA TCC ATC AGG GCC CCG CGG ACG GA) and 3′-A*PCP3 were used, as both gene fragments have the same 3′-end. The sites where the restriction endonucleases cut are underlined in the sequences. After purification, the PCR products were digested with BamHI and NotI, and the genes of interest (ktzO, ktzP and the gene fragments A*PCP3 and PCP3) were each ligated into a BamHI- and NotI-digested pQE30-derived expression vector (Qiagen). The genes coding for ktzN and CDA-T9 were cloned previously10,15 and the resulting expression vectors used to transform E. coli expression strains.

Production of Recombinant Enzymes

The pQE30-plasmids containing the genes or gene fragments of interest and the previously described ktzN and cda-T9 expression plasmids10,15 were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) Star (Invitrogen). For production of recombinant KtzO, KtzP, A*PCP3 and PCP3 the transformed cells were grown at 34°C to an optical density of 0.6 (600 nm), induced with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, final concentration of 0.1 mM) and grown for an additional 5 h at 28°C. The recombinant proteins were purified by Ni-NTA (Qiagen) affinity chromatography using a FPLC (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The Ni column was equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES, 250 mM NaCl pH 8.0 buffer and an increasing gradient of imidazole was employed (7.5 mM to 250 mM in 30 min). Fractions containing the recombinant protein were identified by SDS-PAGE analysis, combined, and subjected to buffer exchange into 25 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.0 using HiTrap Desalting Columns (GE Health Care). The protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using calculated extinction coefficients at 280 nm. The proteins were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. KtzN and CDA-T9 were produced and purified as previously described.10,15

General Hydroxylation Assay

The recombinant hydroxylase (KtzO or KtzP) (5 μM) was incubated for 2 h at 28°C with the co-substrate αKG (2 mM), (NH4)2FeSO4 as source of the ferrous iron co-factor (0.5 mM), and the substrate of interest (200 μM) in 100 μL of 25 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl (pH 7). Reactions were stopped by addition of formic acid (final concentration of 4% v/v). Control reactions were carried out by excluding either the hydroxylase or αKG.

Hydroxylation Assay with Free Amino Acids

The assays were carried out as described above except that the reaction was stopped by addition of nonafluoropentanoic acid (final concentration of 4% v/v). The mixture was then analyzed for the presence of hydroxylated products by reversed-phase HPLC-MS on an ESI-Quad 1100(A) Series MSD mass spectrometer (Agilent) equipped with a Hypercarb column (Thermo Electron Corporation, 100% carbon, pore diameter of 250 Å, particle size of 5 μm). Solvent A was aqueous nonafluoropentanoic acid (20 mM) solution, and solvent B was acetonitrile. Gradient elution was applied starting with 0% B for 5 min, followed by 0–30% B in 25 min, with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min at 15°C.

Hydroxylation Assays with PCP-S-Amino Acid, PCP-HN-Glu and Kinetics

The recombinant PCP, PCP3 (200 μM), or the recombinant PCP with the incomplete A domain, A*PCP3 (200 μM), were artificially loaded with either coenzyme A (CoA) coupled to an amino acid (mainly CoA-Glu, 1 mM) or with amino-coenzyme A (NH2-CoA) coupled to glutamic acid (1 mM) by using the promiscuous phosphopantetheinyl (ppant) transferase Sfp19,20 (2 μM). The loading reaction was incubated at 28°C for 15 min in buffered aqueous solution (pH 7, 25 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2). The synthesis of the CoA-amino acids and a detailed description, based on previously published work,18,21,22 of NH2-CoA synthesis and its coupling to an amino acid are included in the Supporting Information section. To ensure that complete conversion of apo-PCP to PCP-S-amino acid or PCP-HN-Glu was achieved, the loading assays were stopped by addition of formic acid (final concentration of 4% v/v) and the reaction mixture was analyzed by reversed phase HPLC-MS using a QTOF-MS QStar Pulsar i (Applied Biosystems) coupled to a HP 1100 HPLC (Agilent) equipped with a C-4 Nucleosil guard column (Macherey and Nagel, 10 × 3 mm, pore diameter of 300 Å, particle size 5 μm) with the following conditions: solvent A (water/0.45% formic acid), solvent B (acetonitrile/0.45% formic acid), flow rate 0.2 mL/min, temperature 45 °C with a gradient of 10–95% solvent B in 10 min, the gradient was then held for 7 min. Protein mass reconstruction was calculated using Analyst Software v1.5 (Applied Biosciences). After complete loading of the PCP domain was confirmed to occur within 15 min, the reaction was repeated and after 15 min of preincubation for complete loading of the PCP domain, the hydroxylase (either KtzO or KtzP), αKG and iron(II) were added and the assay conducted as described above for the general hydroxylation assay. For kinetic measurements with A*PCP3-HN-Glu and non-cognate CDA-T9-HN-Glu, the hydroxylation assays were set-up as described above and stopped after 30 min, which was determined to be the optimal reaction time for being in the linear conversion range. Substrate concentrations were varied between 10 μM and 450 μM. Kinetic parameters were determined using the calculated starting velocity and the Enzyme Kinetic Module for Sigma Plot 8.0 (SPSS).

Enzymatic Synthesis of hGlu

The general hydroxylation assay was carried out as described above except that the final reaction volume was 200 μL. The proteins were precipitated by addition of 1 mL 10% TCA, and the resulting mixture centrifuged (45 min, 13,000 rpm, 4°C). The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with 200 μL diethyl ether/absolute ethanol (3:1) twice and with 200 μL diethyl ether once. The washed pellet was dried for 5 min at 37°C and 100 μL of 0.1 M aqueous potassium hydroxide solution was added to cleave the thioester bond and release the hydroxylated glutamic acid from the PCP domain. The pellet was resuspended in the KOH(aq) solution and the resulting mixture was incubated at 70°C for 20 min at 1400 rpm in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf). After thioester cleavage, methanol (1 mL) was added, and the mixture was incubated over night at −20°C. Precipitated protein debris was separated from the hGlu-containing supernatant by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 30 min, 4°C). The supernatant was transferred into a new tube and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure by using a SpeedVac-manifold (13,000 rpm, 2 mbar, 30°C). The pellets were stored at −20°C or derivatized immediately for HPLC analysis (see below).

Derivatization and Determination of Configuration of Enzymatically-Synthesized hGlu by HPLC

3-Hydroxyglutamic acid standards were synthesized as previously described.13 The dabsyl derivatization of both enzymatically-prepared and synthetic hGlu was based on published protocols.23,24 The pellets of hGlu were dissolved in buffered aqueous solution (100 μL, 50 mM TRIS, pH 9) and a saturated solution of dabsyl chloride in acetone (100 μL) was added. The mixture was heated at 70 °C for 15 min at 1400 rpm in a Thermomixer and subsequently diluted with absolute ethanol (1 mL). The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min, and 100 μL of the supernatant was analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC-QTOF-MS. Gradient elution was carried out using a Synergi Fusion-RP column (Phenomenex, polar embedded C-18 column, 250 × 3 mm, pore diameter of 80 Å, particle size 4 μm) and the following conditions: solvent A was water/0.45% formic acid; solvent B was acetonitrile/0.45% formic acid. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min with a gradient from 50% B to 75% B over 20 min and then increasing to 95% B over the next min. The gradient was then held for a further 5 min.

Coupled KtzN/PCP/Hydroxylase Assays

The A domain KtzN (2 μM) was incubated with ATP (1 mM), L-glutamic acid (5 mM), DTT (0.5 mM), MgCl2 (1 mM) holo-A*PCP3 (100 μM) or holo PCP3 (200 μM). Holo-PCPs were generated by pre-incubation of the PCPs with CoA (1 mM) and Sfp (2 μM) at 28°C for 15 min (complete conversion validated by QTOF-MS). The coupled assays were also conducted in the presence of KtzO or KtzP (5 μM), αKG (2 mM) and ferrous iron (0.5 mM). All reactions were incubated in buffered aqueous solution (25 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7), stopped after two hours by addition of formic acid (final concentration of 4% v/v) and then analyzed by HPLC-QTOF-MS as described above.

Results and Discussion

Expression and Purification of KtzO, KtzP, A*PCP3, PCP3

The genes ktzO and ktzP, and the gene fragments of A*PCP3 and PCP3, were amplified and cloned into expression vectors and the corresponding recombinant proteins were overproduced in E. coli as His7-tagged fusions (KtzP, 40.1 kDa; KtzO, 39.5 kDa; A*PCP3, 22.3 kDa; PCP3, 11.3 kDa) and purified using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that each protein was isolated in high purity (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Protein identity was verified by mass spectrometry and the following protein yields were obtained from 1 L of bacterial culture: KtzP, 2.2 mg; KtzO, 3.1 mg; A*PCP3, 5.7 mg; PCP3, 0.2 mg.

Hydroxylation of Carrier Protein-Bound Glutamic Acid

Sequence alignments of KtzO and KtzP reveal a putative ferrous iron binding motif HXD/E…H and similarity to the prototype non-heme iron(II) and αKG-dependent taurine dioxygenase TauD25 and other oxygenases (Supporting Information, Table S1). KtzO and KtzP also share high sequence similarity with SyrP, a hydroxylase acting on the β-position of aspartic acid bound to the phosphopantetheinyl (ppant) co-factor of the eighth peptidyl carrier protein of the syringomycin E megasynthetase (SyrE-T8-S-Asp).11 Therefore, KtzO and KtzP were predicted to hydroxylate glutamic acid at the β-position during kutzneride biosynthesis and to act on glutamic acid tethered to the third PCP of KtzH (Figure 1). One can speculate that either one enzyme hydroxylates PCP-bound glutamic acid and generates both isomers of L-3-hydroxyglutamic acid (threo- and erythro-hGlu), and that the other is not involved in hGlu biosynthesis, or that both work on PCP-tethered Glu. In the latter case, it is possible that the enzymes act stereospecifically to each generate one hGlu isomer.

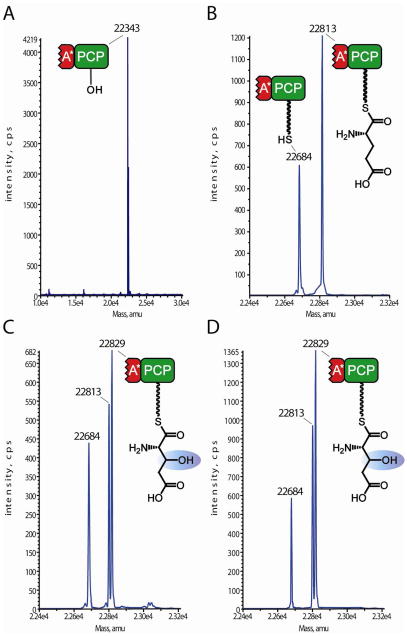

To determine the biochemical origin of the hGlu residues found in mature kutznerides, KtzO or KtzP was incubated with the glutamic acid ppant thioesters of the truncated A* domain-PCP (A*PCP3-S-Glu), as A* might play a role in hydroxylase-PCP interaction. Preincubation of A*PCP3 with synthetic CoA-S-Glu and the promiscuous ppant-transferase Sfp19,20 generated the loaded carrier A*PCP3-S-Glu,, which was subsequently incubated with αKG, Fe(II) and either KtzO or KtzP. QTOF-MS revealed that the apo-form of A*PCP3 (Figure 2A) with an apparent mass of 22,343 Da was loaded with ppant-S-Glu to generate A*PCP3-S-Glu (Figure 2B), indicated by the mass increase of 470 Da. Incubations with KtzO (Figure 2C) and KtzP (Figure 2D) resulted in the formation of hydroxylated A*PCP3-bound L-glutamic acid (A*PCP3-S-hGlu), shown by the mass difference of 16 Da. Hydrolysis of A*PCP3-S-Glu occurred at neutral pH (Figure 2B, 2C, mass: 22,684 Da) after 2 hours. The control reaction lacking αKG only showed the mass of A*PCP3-S-Glu and holo-A*PCP3 (Figure 2B), providing no evidence for hydroxylase activity. Reactions conducted with the single PCP3 (PCP3-S-Glu), also revealed a mass shift of 16 Da, indicating that hydroxylation occurred (Figure S2). These findings demonstrate that both KtzO and KtzP are indeed non-heme iron(II)- and αKG-dependent oxygenases that catalyze the hydroxylation of PCP-tethered glutamic acid in vitro. The truncated A domain observed in module three of KtzH is not required for hydroxylation of PCP-bound substrate.

Figure 2.

QTOF-MS analysis of hydroxylation activity of KtzO and KtzP on PCP-tethered glutamic acid. A: apo-A*PCP3 with an apparent mass of 22343 Da. B, control reaction: A*PCP3 loaded with synthetic coenzyme A glutamic acid by Sfp and incubated for 2h. The mass shift of 470 Da shows that ppant-S-Glu was transferred on the PCP domain. C: A*PCP3 after incubation with αKG, (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 and KtzO, preceded by incubation with Sfp and CoA-S-Glu. The mass difference of 16 Da compared with B indicates hydroxylation of the PCP-bound glutamic acid. D: Same as C, but after incubation with KtzP. Hydrolysis is observed for B and C and D, and the mass of 22684 Da corresponds to the holo-A*PCP3.

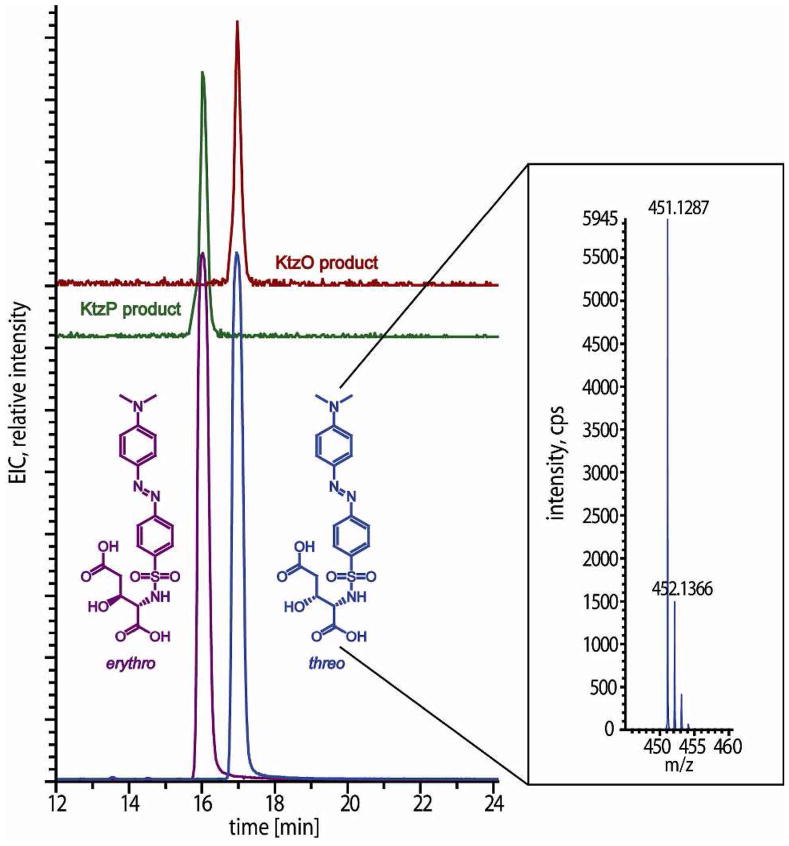

β-Hydroxylation and Stereospecificity

In order to confirm the Glu-β-hydroxylation and to ascertain the stereospecificity of KtzO and KtzP, the threo and the erythro isomers of β-OH-Glu were synthesized as previously described.13 The enantiomerically pure threo-L-hydroxyglutamic acid and the erythro-L-glutamic acid were dabsylated to facilitate separation and identification by reversed phase HPLC-MS.23,24 Co-elution analyses employing synthetic and dabsylated hGlu standards revealed that KtzO and KtzP are stereospecific hydroxylases acting on the β-position of Glu. KtzO generates threo-L-hydroxyglutamic acid and KtzP catalyzes the formation of erythro-hGlu (Figure 3). This system is the first example for a NRPS where products with two isomers of a Cβ modified amino acid are generated by two modifying enzymes that catalyze the very same reaction but with opposite stereospecificity.

Figure 3.

Stereospecificity of KtzO and KtzP. KtzO and KtzP products were cleaved off the PCP, derivatized with dabsyl-Cl, analyzed via HPLC-MS and compared with synthetic standards of the dabsylated L-β-hydroxyglutamic acids. The KtzP product co-elutes with the Dab-L-erythro-hGlu and the KtzO product with the threo form. High resolution mass spectrometric analyses of the peaks (observed [M+H]+= 451.1287 m/z) are in accordance with the theoretical masses (451.1282 m/z).

Transfer of Glutamic Acid on A*PCP3 by KtzN

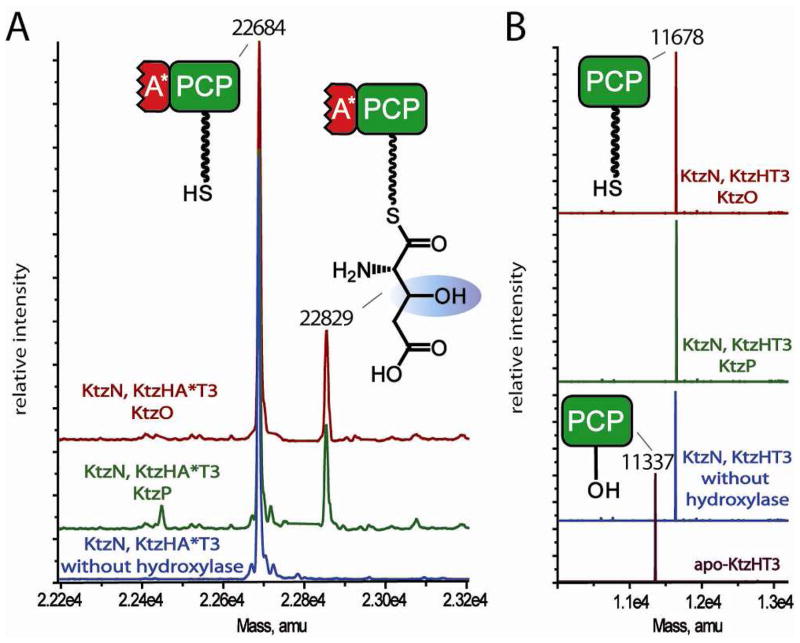

Another intriguing factor regarding tailoring of hGlu and the kutzneride assembly line is the mechanism of activation and transfer of the glutamic acid onto the third PCP domain of KtzH. It was postulated that the stand-alone adenylation domain KtzN (Figure 1) acts as an in trans substitute domain for the truncated A* domain in the third module of HtzH by activating glutamic acid as an amino acyl adenylate, and transferring it to the third module. KtzN was shown to activate glutamic acid in previous studies, but the transfer event and factors that may mediated this reaction, such as protein-protein interaction, the role of the hydroxylases or A*, have not been investigated.15 KtzN is predicted to be the first example for specific NRPS assembly line in trans recovery, which most likely involves specific protein-protein interactions between the third module of KtzH and KtzN, Without such specific protein-protein interactions, it is likely that KtzN would load all four PCPs of KtzH with glutamic acid.

To evaluate what protein-protein interactions are required for Glu transfer by KtzN and gain more mechanistic insight into this unusual NRPS recovery strategy, Glu transfer was monitored in an assay containing recombinant KtzN (Glu A domain), ATP, L-Glu, holo-A*PCP3 and in the absence or presence of one hydroxylase (KtzO or KtzP), αKG and ferrous iron. Analysis of the assay of KtzN with holo-A*PCP3 in the absence of hydroxylase revealed that no glutamic acid was transferred (Figure 4A, blue trace). Upon addition of either KtzO (Figure 4A, dark red trace) or KtzP (Figure 4A, green trace), co-substrate and co-factor, glutamic acid was transferred onto A*PCP3 and subsequently hydroxylated. The reaction was either not complete or hydrolysis of the PCP-S-hGlu thioester occurred prior to analysis, indicated by the prominent holo-A*PCP3 peak (Figure 4A). To evaluate the role of the truncated adenylation domain A*, the assay was carried out using the single PCP domain instead of A*PCP. MS analyses showed that no glutamic acid was transferred regardless of the presence or absence of any hydroxylase (Figure 4B). These results demonstrate that two factors are critical for KtzN-mediated transfer of glutamic acid onto the third PCP domain of KtzH in vitro: the presence of one of the two hydroxylases and the presence of A*, the truncated A domain in KtzH. These requirements explain the selective transfer of Glu to the third module of KtzH by KtzN during the in trans compensation mechanism. KtzN is indeed able to restore the assembly line by acting in trans and is the first example for an in trans acting NRPS adenylation domain recovery protein.

Figure 4.

MS analysis of coupled glutamic acid transfer assays. A: Incubation of KtzN with holo A*PCP3, KtzO (red trace) or KtzP (green trace) and their co-substrates yielded the transfer of glutamic acid and subsequent hydroxylation by KtzO and KtzP. No transfer of glutamic acid by KtzN was observed with a hydroxylase was not added (blue trace). B: Role of A*: The KtzN coupled assay was carried out as in A, but the single PCP was used instead of A*PCP of the third module of KtzH. In all cases, only holo-PCP was detected after the coupled assays, indicating that one hydroxylase and the A* domain is needed to allow KtzN-mediated transfer of glutamic acid on the PCP domain.

Kinetic Parameter Determination Using CoA Analogs

The unstable nature of the thioester bond between glutamic acid and PCP, as observed in the assays stated above (Figure 2BC, Figure 4A), makes it difficult to collect accurate biochemical data for determining the kinetic parameters for KtzO- and KtzP-catalyzed reactions. Although different strategies have been developed to circumvent thioester hydrolysis, e.g. amide ligation,26 basic cleavage or thioesterase type II mediated cleavage,9 a convincing method for direct kinetic parameter determination of carrier protein ppant-thioesters has not been established to date. The reported methods involve thioester cleavage, and thus the amount of substrate hydrolyzed prior to cleavage is impossible to quantify.

The method introduced herein, inspired by work of the Bruner group where phosphopantetheinyl thioester mimics, including amino-coenzyme A (NH2-CoA), were used to manipulate the geometry of carrier domains in multidomain NRPS assemblies18 involves replacement of the labile thioester linkage with a hydrolytically stable amide bond. Amino-coenzyme A was used as a synthetic precursor to prepare a non-hydrolyzable amino-coenzyme A coupled to glutamic acid as detailed in Supporting Information. Instead of starting the synthesis with trityl-diaminoethane resin, which was used in previous studies,18 free pantothenic acid was used. The diol was protected and the pantothenic acid was coupled to Boc-diaminoethane to yield fully protected aminopantetheine. After deprotection aminopantetheine was incubated with the three coenzyme A biosynthesis27 enzymes PanK, PPAT, DPCK, which were recombinantly expressed in E. coli,18,28 and ATP to yield the coenzyme A analog, in which the thiol group is replaced by an amine group (Scheme S1). The amino-CoA was then coupled to the Boc-protected glutamic acid using standard amide coupling reagents. Upon acidic in situ deprotection, CoA-HN-Glu was obtained with an overall yield of 4%.

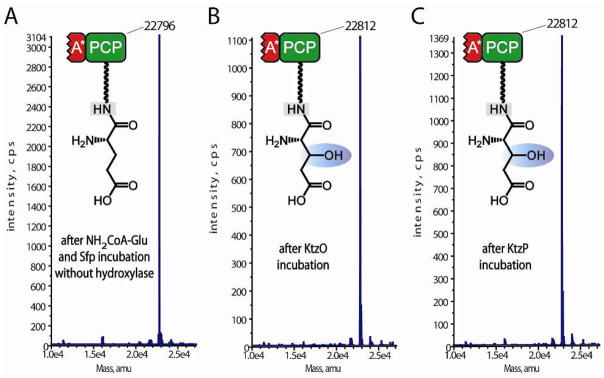

A*PCP3 was loaded with CoA-HN-Glu by Sfp to yield the A*PCP3-HN-Glu and MS analysis revealed complete conversion of apo-A*PCP3 to A*PCP3-HN-Glu (Figure 5A). After incubation with either KtzO or KtzP, αKG and ferrous iron, a mass shift of 16 Da was observed (KtzO, Figure 5B, KtzP, Figure 5C), demonstrating that KtzO and KtzP catalyzed the hydroxylation of A*PCP3-HN-Glu. The additional oxygen introduced by the hydroxylation reaction is of no consequence for the ionization properties of examined protein. Thus, the mass spectrometer counts for the loaded A*PCP3-HN-Glu and its hydroxylated form were used to determine the percentage of the hydroxylated protein species relative to the non-hydroxylated one. By variation of the A*PCP3-HN-Glu concentration (10 to 450 μM), it was possible to measure the starting velocities and therefore to determine Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters (Figure S3), which are listed in Table 1. One characteristic of these hydroxylases is the high affinity to their substrate, which is shown by the relatively low KM values (KtzO: 121.5 μM, KtzP: 168.9 μM) compared with free amino acids modifying enzymes (AsnO: 479 μM, VioC: 3400 μM)10,12 (Table 1). Other features are their low turn-over numbers (KtzO: 0.34 min−1, KtzP: 0.44 min−1) compared with free amino acid hydroxylases (AsnO: 299 min−1, VioC: 2611 min−1) and the low catalytic efficiencies (Table 1). However, the catalytic efficiencies of KtzO and KtzP are identical, which explains why both isomers of the hydroxylated glutamic are found at equal amounts in the mature kutznerides, and only differ in the grade of substitution of other residues (Figure 1). A*PCP3 was chosen for kinetic measurements over the single PCP as its production level and its ionization properties are much better. However, the incubation of the single PCP with KtzO or KtzP yielded the same conversion percentage (data not shown), indicating that that similar kinetic properties should be expected.

Figure 5.

QTOF-MS analysis of CoA-HN-glutamic acid loading on A*PCP3 and hydroxylation assays. A: A*PCP3 incubated with Sfp and CoA-HN-Glu. The mass shift of 453 Da compared to apo-A*PCP3 (Figure 4A, 22343 Da) is in agreement with the calculated ppant-HN-Glu addition. B, C: Incubation of ppant-HN-Glu loaded A*PCP3 with KtzO (B) or KtzP (C) yielded in a mass shift of 16 Da, suggesting hydroxylation.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for the hydroxylation reactions catalyzed by KtzO and KtzP and comparison with free amino acid hydroxylating non-heme iron oxygenases AsnO10 and VioC.12

| Substrate | Enzyme | KM [μmol] | kcat [min−1] | kcat/KM [min−1μmol−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A*PCP3-HN-ppant-Glu | KtzO | 121.5 ± 28.1 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 2.8•10−3 |

| A*PCP3-HN-ppant-Glu | KtzP | 168.9 ± 44.0 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 2.6•10−3 |

| CDA-T9-HN-ppant-Glu | KtzO | 123.3 ± 10.9 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 2.7•10−3 |

| CDA-T9-HN-ppant-Glu | KtzP | 148.5 ± 21.1 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 2.8•10−3 |

| asparagine | AsnO | 479 ± 6.7 | 298.8 ± 19.2 | 0.62 |

| arginine | VioC | 3400 ± 450 | 2611 ± 196 | 0.76 |

Substrate Specificity

To further characterize KtzO and KtzP, their substrate specificities were evaluated. Free amino acids (L-Glu, D-Glu), different PCP-bound amino acids, especially aspartic acid because of its observed activity in KtzN adenylation assays,15 CoA-S-Glu as PCP mimic as well as a non-cognate PCP domain from the CDA biosynthetic cluster10 were considered and the results are summarized in Table S2.

The free amino acid were not accepted as substrates by KtzO or KtzP and therefore a precursor synthesis pathway can be excluded. KtzO and KtzP were found to be highly specific for hydroxylation of PCP-bound L-glutamic acid; PCP-S-D-Glu was not a substrate. The D-hGlu moieties as observed in mature kutznerides are thus likely to be generated exclusively by the action of the epimerization domain, which is present in the third module of KtzH.

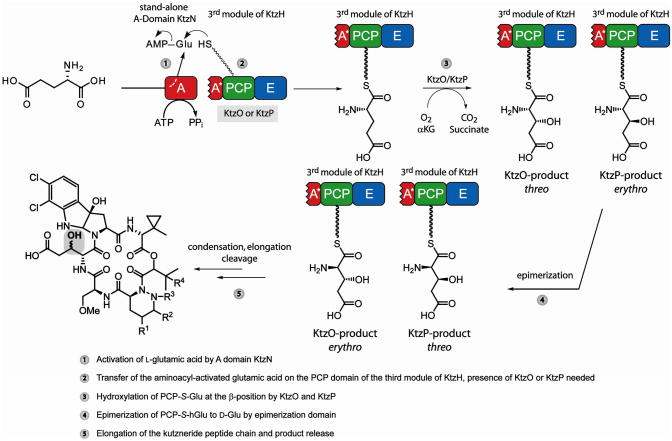

From this biochemical characterization of KtzO and KtzP, in addition to the studies of KtzN-mediated Glu transfer onto the third PCP domain of KtzH, a reaction mechanism for the origin of the threo- and erythro-D-3-hydroxyglutamic acid moieties found in mature kutznerides can be proposed (Figure 6). The stand-alone adenylation domain KtzN first activates L-glutamic acid as amino acyl adenylate, which then can be transferred site-specifically to the third PCP domain of KtzH. The specificity of this interaction is mediated by the presence of the truncated A domain (A*) as well as one hydroxylase, either KtzO or KtzP. Both A* and a hydroxylase are required for Glu-AMP transfer. Subsequently, the PCP-bound glutamic acid is hydroxylated by KtzO to yield to L-threo-3-hydroxyglutamic acid or by KtzP to afford L-erythro-3-hydroxyglutamic acid. Epimerization of the two PCP-S-L-hGlu to D-amino acids, catalyzed by the E domain, will also convert the relative positioning of the hydroxyl group such that that the KtzO product becomes erythro-D-hGlu and the KtzP product threo-D-hGlu. Subsequently, condensation and peptide elongation occur, and release of the mature peptide is achieved by cyclization by the thioesterase domain.

Figure 6.

Proposed reaction mechanism for glutamic acid activation, incorporation and hydroxylation during kutznerides assembly.

KtzO and KtzP are both able to hydroxylate glutamic acid bound to a non-cognate PCP, in this case the ninth PCP domain of the CDA NRPS assembly line (CDA-T9)10 (Figure S4). The kinetic parameters for this reaction were determined as well for both hydroxylases (Figure S5) and it was found that KtzO and KtzP were similarly efficient in hydroxylating CDA-T9-HN-Glu compared with A*PCP3-HN-Glu in vitro (Table 1). These findings make ktzO and ktzP valuable targets for gene transfer into NRPS gene clusters, which produce natural products with a glutamic acid moiety. A strong overproduction of KtzO and KtzP within these clusters could yield in NRPS products containing hGlu moieties, which might improve the bioactivity of these natural products.

Conclusions

KtzO and KtzP are non-heme iron(II)/αKG-dependent hydroxylases. Notably, they both work on PCP tethered glutamic acid. One could expect from the kutzneride structures, where the threo and erythro 3-hydroxyglutamic acids are found in similar amounts, that it would be more economical for the kutzneride NRPS to have only one enzyme for Glu hydroxylation. This enzyme could catalyze β-hydroxylation of PCP-S-L-Glu, providing racemic mixture in a kind of epimerization mechanism. Instead, evaluation of KtzO and KtzP shows there are two on-line hydroxylating enzymes in kutzneride biosynthesis, which stereospecifically catalyze the formation of PCP-S-L-threo-hGlu (KtzO) and PCP-S-L-erythro-hGlu (KtzP).

The transfer of the glutamic acid onto the third PCP domain of KtzH was investigated. The truncated adenylation domain of the third module of KtzH is non-functional, and the stand-alone A domain KtzN, which was shown to activate glutamic acid as aminoacyl adenylate,15 acts as in trans to restore the NRPS assembly line. Assembly line recovery and transfer of glutamic acid onto the PCP is only achieved when the A* domain and at least one of the hydroxylases are present in vitro. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first characterization of an in trans acting adenylation domain, which simultaneously restores the ability of an NRPS assembly line to produce a secondary metabolite.

To determine the kinetic parameters of KtzO and KtzP catalyzed hydroxylations, the problem of the labile thioester bond of A*PCP3-S-Glu was circumvented by using synthetic coenzyme A analogs coupled to glutamic acid where the thioester was replaced by a hydrolytically stable amide bond. This method, adapted from previous work,18,21,28 is a simple and robust way for to investigate carrier proteins, which have substrates bound via a prosthetic ppant arm. The applications of this methodology are broad and it may be used in investigations of related peptidyl, fatty acid or acyl carrier proteins that involve substrate trapping, NMR and X-ray crystallography studies or whenever a labile thioester is a problem.

Finally, KtzO and KtzP exclusively hydroxylate PCP-bound glutamic acid, but do not require the cognate PCP of module three of KtzH for in vitro activity. If the NRPS on-line modification by non-cluster enzymes can be transferred to in vivo applications, the insights from this study might assist in future reengineering approaches of NRPS gene clusters in order to generate new secondary metabolites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Antje Schäfer and Volker Gatterdam for excellent technical assistance, and Dr. Uwe Linne for help with MS measurements. We also thank Dr. Eric R. Strieter for providing the expression plasmids containing genes for the coenzyme A biosynthesis enzymes and for sharing NH2-CoA synthesis experience. Financial support was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (M. S. and M. A. M.) as well as NIH grant GM43998 (C.T.W.) and a NIH post-doctoral fellowship (E. M. N.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Sequence alignments, experimental details of amino CoA synthesis and coupling of CoA/NH2-CoA to amino acids, SDS-PAGE analysis of the studied enzymes, hydroxylation assay analysis of KtzO and KtzP with PCP3-S-Glu, CDA-T9-HN-Glu and kinetic data. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Walsh CT. Science. 2004;303:1805–1810. doi: 10.1126/science.1094318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strieker M, Marahiel MA. Chembiochem. 2009;10:607–616. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samel SA, Marahiel MA, Essen LO. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:387–393. doi: 10.1039/b717538h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbard BK, Walsh CT. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:730–765. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sussmuth RD, Wohlleben W. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63:344–350. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1443-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milne C, Powell A, Jim J, Al Nakeeb M, Smith CP, Micklefield J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11250–11259. doi: 10.1021/ja062960c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahlert C, Kopp F, Thirlway J, Micklefield J, Marahiel MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12011–12018. doi: 10.1021/ja074427i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neary JM, Powell A, Gordon L, Milne C, Flett F, Wilkinson B, Smith CP, Micklefield J. Microbiology. 2007;153:768–776. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002725-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaillancourt FH, Yin J, Walsh CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10111–10116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504412102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strieker M, Kopp F, Mahlert C, Essen LO, Marahiel MA. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:187–196. doi: 10.1021/cb700012y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh GM, Fortin PD, Koglin A, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11310–11320. doi: 10.1021/bi801322z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmetag V, Samel SA, Thomas MG, Marahiel MA, Essen LO. Febs J. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broberg A, Menkis A, Vasiliauskas R. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:97–102. doi: 10.1021/np050378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohanka A, Menkis A, Levenfors J, Broberg A. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1776–1781. doi: 10.1021/np0604331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimori DG, Hrvatin S, Neumann CS, Strieker M, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16498–16503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708242104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausinger RP. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:21–68. doi: 10.1080/10409230490440541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clifton IJ, McDonough MA, Ehrismann D, Kershaw NJ, Granatino N, Schofield CJ. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:644–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Bruner SD. Chembiochem. 2007;8:617–621. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambalot RH, Gehring AM, Flugel RS, Zuber P, LaCelle M, Marahiel MA, Reid R, Khosla C, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 1996;3:923–936. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reuter K, Mofid MR, Marahiel MA, Ficner R. Embo J. 1999;18:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koglin A, Lohr F, Bernhard F, Rogov VV, Frueh DP, Strieter ER, Mofid MR, Guntert P, Wagner G, Walsh CT, Marahiel MA, Dotsch V. Nature. 2008;454:907–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier JL, Mercer AC, Rivera H, Jr, Burkart MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12174–12184. doi: 10.1021/ja063217n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim TY, Kim HJ. J Chromatogr A. 2001;933:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)01240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vendrell J, Aviles FX. J Chromatogr. 1986;358:401–413. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eichhorn E, van der Ploeg JR, Kertesz MA, Leisinger T. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23031–23036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopp F, Linne U, Oberthur M, Marahiel MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2656–2666. doi: 10.1021/ja078081n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begley TP, Kinsland C, Strauss E. Vitam Horm. 2001;61:157–171. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)61005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke KM, Mercer AC, La Clair JJ, Burkart MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11234–11235. doi: 10.1021/ja052911k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.