Abstract

Participation in the workplace has been proposed as a potential structural-level HIV/STI prevention strategy for youth. Only a few cross-sectional studies have explored the effect of work during adolescence and young adulthood on sexual behavior and their results have been mixed. This study builds on this literature by exploring whether work influences youths’ sexual behavior in a cohort of African American youth [N = 562; 45% males; M = 14.5 years, SD = 0.6] followed from adolescence to young adulthood (ages 13 to 25). Using growth curve modeling, we tested whether working was associated with older sex partners. Then, we explored the association between sex partner age differences and sexual behaviors (i.e., number of sex partners, condom use, and frequency of sexual intercourse). Finally, we tested whether the relationship between sex partner age differences and sexual behaviors was confounded by working. Working greater number of hours was not significantly associated with having older sex partners. Sex partner age differences was associated with number of partners, condom use, and and higher sex frequency. These associations were larger for females. Working was associated with higher sex frequency, after accounting for age differences. We discuss the implications of these findings for future research and program planning, particularly in the context of youth development programs.

Keywords: African American, sexuality, employment, partner, adolescence

INTRODUCTION

During adolescence and young adulthood, youth may participate in the workforce in order to increase their socioeconomic position, facilitate their independence from parents, and begin to assert their adult identity. Researchers and policy makers have argued that, if true, this work benefits perspective could be considered a structural strategy that would promote healthy youth development (Greenberger & Steinberg, 1986). Most research exploring the effects of employment on health outcomes during adolescence and young adulthood, however, has focused on the effects of employment on internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors (Bauermeister, Zimmerman, Barnett & Caldwell, 2007; Staff, Mortimer & Uggen, 2004). Unfortunately, we know very little as to how employment influences youths’ sexual behavior. Is working during adolescence and young adulthood associated with youths’ sexual behavior?

The Role of Employment in Sexual Behavior

Financial inequalities may increase the risk for HIV/AIDS or sexually-transmitted infections (STI) by limiting access to condoms and increasing inconsistent condom use. In their Theory of Gender and Power, Connell (1987) and Wingood and DiClemente (2002) have posited that sexual power imbalances are socially maintained and reinforced by females’ unequal socioeconomic dependence on males, with its impact stronger among individuals of lower socioeconomic status. Females are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed (Wingood & DiClemente, 1998), have lower control of their work environments (Hall, 1991), and earn less and work less prestigious occupations than their male counterparts (US Department of Labor, 2006). These socioeconomic imbalances are most notable among females with low incomes or who are unemployed (Brewster, 1994), who have less than a high school education (Anderson, Brackbill, & Mosher, 1996), who belong to a racial and ethnic minority (CDC, 2005), and who are young (CDC, 2005).

The few studies exploring the effects of work on youth's sexual health, however, have found mixed results. Kraft and Coverdill (1994) found that African American female youth participating in the labor force during adolescence and young adulthood were less likely to become pregnant and/or infected with a STI. In a subsequent study, however, Coverdill and Kraft (1996) found no significant association between work and premarital pregnancy for African American working females, regardless of wage levels or length of employment. For White and Latino females, however, working decreased the risk of premarital conception as wages and length of employment increased. Taken together, these studies suggest that work is beneficial for youths’ sexual health. Unfortunately, the generalizability of these studies’ findings is somewhat limited because the researchers used data from 1979 to 1986, which assumes no changes in the construction of workforce participation or in the association between employment and sexual behavior since 1986.

In contrast to these studies, Rich and Kim (2002) found current and cumulative work to be associated with earlier onset of sexual intercourse among females participating in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. As the number of hours worked increased, female adolescents were more likely to report having first intercourse at an earlier age than their counterparts working fewer hours or not working at all. This is particularly worrisome considering recent evidence suggesting earlier onset of sexual intercourse may be associated with greater number of STIs later in life (Sandfort, Orr, Hirsch, & Santelli, 2008). Furthermore, pregnancy outcomes varied by race/ethnicity. Current employment increased the risk of pregnancy among African Americans, but not for White Americans. These race differences should be interpreted with caution, however, given the different trends in the timing of fertility across racial and ethnic groups in the United States and the heterogeneity within each racial group (Geronimus, 2001; Geronimus, Bound, & Waidmann, 1999).

One potential explanation for these mixed results is the presence of a third-variable acting as a confounder. Greater workforce involvement, for example, exposes adolescents and young adults to greater chances of interacting with older individuals. Youth participating actively in the workforce may be exposed to a greater number of older youth and adults who may become sex partners. Could the relationship between work and sex behaviors be explained by a third variable such as the age difference between youth and their sexual partners? If true, then previous relationships found between working and sexual behaviors could be explained by the mediation of sex partners’ age differences. In this study, we explore the plausibility of this mediation model by testing whether the association between the number of hours worked and sexual behaviors persists after adjusting for sex partners’ age differences across adolescence and young adulthood.

Sex Partner Age Differences

Sex partner characteristics influence youths’ sexual decision-making and their risk of acquiring STIs during adolescence and young adulthood (DiClemente, Wingood, Crosby, Sionean, Coob, Harrington, et al., 2002). Having an older sex partner, for example, increases earlier sexual onset, inconsistent condom use, and STIs in national samples of adolescents and young adults (Ford & Lepkowski, 2004; Silbereisen & Kracke, 1997). Unfortunately, most studies exploring the effects of sex partners’ age on youths’ sexual behaviors have used cross-sectional designs. Prospective studies describing how sex partners’ age influence youths’ sexual behaviors over time may be useful in the tailoring of prevention programs. In this study, we explore whether variations in age between youth and their sex partners increase their sexual behaviors (e.g., condom use, sex frequency, and number of partners) during adolescence and young adulthood.

Researchers studying sex partners’ age as a predictor of sexual behavior have often operationalized this measure as a categorical variable (i.e., partner is two or more years younger, partner is of same age or less than two years apart, partner is two or more years older). Limiting sex partners’ age to these arbitrary categorical values can mask more complex relationships between sex partner age and sexual behavior. As an alternative, Kaestle, Morisky, and Wiley (2002) created an “age difference” variable that measured the difference in age between female participants in their sample and their male sex partners. Kaestle et al. (2002) found that having an older sex partner was associated with greater number of sexual intercourse occasions. This association, however, had a curvilinear trend, with the magnitude of the association decreasing as female participants grew older. Their study, however, was limited by several factors. First, Kaestle et al. truncated the distribution of the age difference score by assigning the same value (i.e., age difference = 0) to participants who had partners of the same-age and to participants who had younger sex partners. Consequently, the risk estimates reported in their findings may be biased. Second, Kaestle et al. focused their analyses solely on females. Age gaps may have different effects for males and females and deserve further study. While we follow Kaestle et al.'s (2002) approach to study sex partners’ age on sexual behavior, we model the age difference as a non-truncated score, where positive values representing youth's age difference with their older sex partners and negative values representing their age difference with younger sex partners. Furthermore, we explore whether sex partners’ age differences have different implications for males and females’ sexual behaviors.

The Role of Employment during Adolescence and Young Adulthood

Compared to any other race or ethnic group in the United States, African Americans have the highest unemployment rate (i.e., unemployed and looking for a job in the past 6 months), with a current season-adjusted rate of approximately 11% (US Department of Labor, 2004). Among adolescents, the unemployment rate among 16 to 19 year old African Americans (30%) was twice as high as that of Whites (15%). The striking difference in unemployment rates between White and African American youth raise questions related to the equitable development of both groups within health-promotive social contexts. Racial differences in HIV incidence, for example, suggest that African American males and females are 8 and 25 times more likely, respectively, to be infected than their White counterparts. As the effects of socioeconomic status are hard to detangle from a race-conscious society (Brewster, 1994; Link & Phelan, 2003; Shelton, Cassell, & Adetunji, 2005), HIV infection is also patterned by socioeconomic status. HIV and STI incidence is increasing among adolescents and young adults living in poverty, lacking access to quality medical care, and at-risk of dropping out of school (Office of the Surgeon General, 2003; US Census, 2003; Valleroy, MacKellar, Karon, Janssen, & Hayman, 1998). This study acknowledges these demographic disparities by exploring whether employment's effect on sexual behaviors varies depending on youths’ gender, risk of high school dropout, and their socioeconomic status.

Study Objectives and Hypotheses

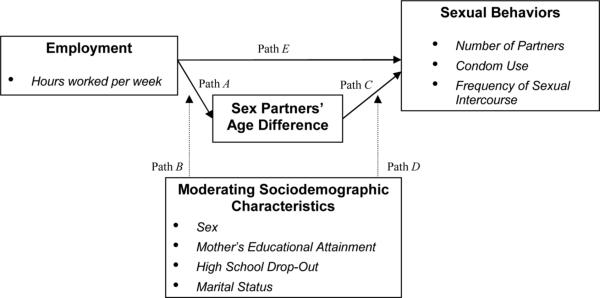

Because STIs are preventable through behavior change, a greater understanding of what negative and positive factors are associated with sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults is needed. Building on the previous limitations of the research literature on employment and sexual behaviors of adolescents and young adults, this study follows a sample of African Americans beginning at age 13 until age 25 in order to address four gaps in the scientific literature. First, we test whether the number of hours worked predicts sex partners’ age differences across adolescence and young adulthood (Path A in Fig. 1). We hypothesize that adolescents and young adults working greater number of hours during these two developmental periods will also report older sex partners, with the effect also being moderated by sex, mother's education, high school dropout, and marital status (Path B in Fig. 1). Then, we test whether age differences predict sexual behaviors over time (Path C in Fig. 1). Congruent with previous research, we hypothesize that youth with older sex partners will report greater sexual behaviors over time. We follow our analyses by testing whether this association is moderated by participants’ sex, mother's education, high school dropout, and marital status during adolescence and young adulthood (Path D in Fig. 1). Congruent with the theory of gender and power (Connell, 1987), we hypothesize that the association between partners’ age differences and sexual behaviors will be most salient for females, especially if they have mothers with fewer years of education or if they dropped out of high school. Finally, we test a mediation model that examines whether the effects of work on sexual behaviors over time are mediated by the differences between partners’ age over time (Path C through Path A after considering Path E in Fig. 1). We hypothesize that the relationship between number of hours worked and sexual behaviors will disappear after accounting for sex partner age differences.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Mediation between Work, Sex Partners’ Age Differences, and Sexual Behaviors during Adolescence and Young adulthood in a Sample of African Americans.

METHOD

This study was based on a 8-year longitudinal study exploring the relationship between substance use and high school dropout among youth who were followed from mid-adolescence to young adulthood. Participants in this study were recruited based on their risk for school dropout. To be eligible for the study, participants had a grade point average (GPA) of 3.0 or lower at the end of the eighth grade, were not diagnosed by the school as having emotional or developmental impairments, and identified as African American, White, or Bi-racial (African American and White). Data were collected from 850 adolescents beginning their ninth grade (wave 1: 1994) in four public high schools in a midwestern U.S. city. Waves 1 through 4 correspond to the participants’ high school years (1994−1997). We did not collect data the year between waves 1−4 and 5−8; thus, waves 5 through 8 correspond to the second, third, fourth, and fifth years post-high school (1999−2002).

Participants

Adolescents self-reporting as African American constituted 80 percent of the sample in wave 1 (N = 681). We focused the analyses on the African American subsample because they are at a greater risk for HIV infection in the US (CDC, 2005). A total of 89 participants were excluded from the analyses due to missing data on the number of hours worked per week on more than two of the first four study waves. Missing information on hours worked hours per week during two or more of the four waves of high school diminished testing how work trajectories during adolescence and young adulthood influence sexual behavior. In addition, another 30 participants were excluded from the analyses if they reported their sexual debut occurred prior to age 9 or their last sex partner was under the age of 9. These participants may reflect unusually precocious sexual behavior or involuntary sexual encounters. Consequently, these participants are at greater sexual behavior than the rest of the sample and their inclusion in the analyses may overestimate the association between the number of hours worked and sexual behaviors.

Procedure

After receiving IRB approval, structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with students in school or in a community setting if the participants could not be found in school. After the face-to-face interview portion of the protocol, participants completed a self-administered paper and pencil questionnaire about alcohol and substance use, sexual behaviors and other sensitive information. Waves 5 through 8 interviews were mostly conducted in a community setting. On average, each interview lasted 50 to 60 minutes. Parental consent was obtained for minors. Compensation for participants’ time was given ($15 for wave 1, $20 for waves 2−4; and $25 for waves 5−8). The study had a 90% response rate over the first four waves of the study and a 68% response rate over all eight waves.

Measures

Table I presents descriptive statistics for each sexual behavior measure by sex across all waves.

Table I.

Sexual Behavior Measures by Sex

| Number of partners | Inconsistent Condom Usea | Intercourse Frequency | Sex partners’ age difference in yearsb,c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave | M, SD | N | M, SD | N | M, SD | N | M, SD | N |

| Males | ||||||||

| 1 | 2.89, 4.14 | 228 | 1.80, 1.25 | 170 | 2.03, 1.78 | 238 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 2.72, 3.80 | 234 | 1.48, .92 | 176 | 2.15, 1.77 | 236 | −.14, 1.66 | 171 |

| 3 | 2.79, 3.81 | 227 | 1.46, .80 | 169 | 2.48, 1.95 | 232 | .04, 2.25 | 166 |

| 4 | 2.53, 2.93 | 213 | 1.86, 1.13 | 175 | 2.89, 1.94 | 219 | −.06, 2.23 | 179 |

| 5 | 2.80, 4.95 | 166 | 2.30, 1.39 | 138 | 3.40, 1.96 | 167 | .44, 3.11 | 138 |

| 6 | 2.21, 2.44 | 185 | 2.13, 1.41 | 157 | 3.44, 1.96 | 189 | .08, 2.99 | 154 |

| 7 | 2.27, 2.76 | 155 | 2.48, 1.54 | 139 | 3.54, 1.89 | 157 | −.24, 2.85 | 135 |

| 8 | 2.10, 2.66 | 163 | 2.34, 1.58 | 137 | 3.69, 1.91 | 166 | −.30, 3.51 | 144 |

|

Females | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.46, 1.97 | 291 | 1.85, 1.27 | 168 | 1.53, 1.72 | 293 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 1.31, 1.67 | 299 | 2.02, 1.37 | 192 | 1.88, 1.85 | 300 | 1.30, 2.31 | 193 |

| 3 | 1.63, 2.32 | 300 | 2.25, 1.39 | 217 | 2.30, 1.92 | 300 | 1.36, 2.45 | 221 |

| 4 | 1.53, 1.61 | 266 | 2.55, 1.42 | 220 | 2.97, 1.92 | 268 | 1.33, 2.55 | 238 |

| 5 | 1.67, 1.67 | 249 | 2.94, 1.54 | 222 | 3.62, 1.85 | 249 | 2.04, 3.40 | 218 |

| 6 | 1.38, 1.26 | 249 | 2.99, 1.61 | 217 | 3.50, 1.92 | 249 | 2.06, 3.56 | 216 |

| 7 | 1.40, 1.18 | 236 | 2.98, 1.57 | 198 | 3.49, 2.00 | 238 | 2.69, 4.31 | 198 |

| 8 | 1.37, 1.06 | 239 | 2.8, 1.65 | 193 | 3.56, 1.88 | 239 | 2.78, 4.69 | 206 |

Variable is reverse coded (1=Always use condom; 5=Never use condom)

Measure created by subtracting participants’ age at the time of interview from the reported age of their last sexual partner in each wave (e.g., Sex partner's age – Participant's age).

Measure not collected in wave 1.

Sex Partners’ Age Differences

We calculated sex partners’ age differences by subtracting the participants’ age at the time of each interview from the reported age of the participants’ last sexual partner in each wave (e.g., Last sexual partner's age – Participant's age). Age of participants’ last sexual partner was asked in an open-ended question across waves 2 through 8 (“The last time you had sex, how old was your partner?”). Participants who reported not having sex in the previous year or unable to recall their partner's age were coded as missing. All participants were assigned a missing value for wave 1.

Number of Sex Partners

For wave 1, participants reported the number of sex partners up to that point in an open-ended question format (“How many sex partners have you ever had?”). For all other waves, participants self-reported the number of sex partners in the past year by answering an open-ended question (“How many sex partners have you had in the last year?”). Participants who reported that they never had sex in their lifetime or did not have sex in the previous year were coded as having zero partners.

Inconsistent Condom Use

For wave 1, participants reported their condom use over their lifetime. Across all other waves, participants self-reported their condom use over the previous year (“How often have you used a condom when having sex in the last year?”). Participants could respond with one of the following categories: 1 = Almost never, 2 = Not very often, 3 = Half of the time, 4 = Most of the time, and 5 = Always. This measure was reverse coded so every unit increase reflected greater risk: 1 = Always wears condoms, 2 = Wears condoms most of the time, 3 = Half of the time, 4 = Does not wear condoms very often, and 5 = Almost never wears condoms. Participants reporting never having sex or not having had sex in the previous year were coded as missing.

Frequency of Sexual Intercourse

Participants self-reported their frequency of sexual intercourse in the previous year (“How many times have you had sex in the last year?”). Participants could respond using the following categories: 0 = None, 1 = 1 or 2 times, 2 = 3 to 5 times, 3 = 6 to 8 times, 4 = 9 to 11 times, and 5 = 12 or more times. Participants reporting never having sex or not having had sex in the previous year were coded as zero.

Number of Hours Worked

To measure work, participants reported the number of hours per week they worked for each wave (“On the average over the school year, how many hours per week do you work in a job for a pay?” for waves 1−3; and, “How many hours per week do you work?” for waves 4−8). Response categories were: 1 = None, 2 = Less than 10 hours, 3 = 11−20 hours, 4 = 21−30 hours, and 5 = More than 30 hours. Table II presents the distribution of hours worked for each wave.

Table II.

Number of Hours Worked per Week by Sex

| Wave | None N (%) | < 10 hours N (%) | 11−20 hours N (%) | 21−30 hours N (%) | 31+ hours N (%) | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | ||||||

| 1 | 220 (87.6%) | 19 (7.6%) | 6 (2.4%) | 5 (2.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 251 |

| 2 | 217 (86.5%) | 12 (4.8%) | 16 (6.4%) | 6 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | 251 |

| 3 | 158 (63.5%) | 14 (5.6%) | 37 (14.9%) | 29 (11.6%) | 11 (4.4%) | 249 |

| 4 | 149 (59.8%) | 13 (5.2%) | 37 (14.9%) | 27 (10.8%0 | 23 (9.2%) | 249 |

| 5 | 57 (33.9%) | 1 (0.6%) | 8 (4.8%) | 20 (11.9%) | 82 (48.8%) | 168 |

| 6 | 65 (34.4%) | 3 (1.6%) | 10 (5.3%) | 13 (6.9%) | 98 (51.9%) | 189 |

| 7 | 56 (34.6%) | 4 (2.5%) | 8 (4.9%) | 18 (11.1%) | 76 (46.9%) | 162 |

| 8 | 53 (31.4%) | 4 (2.4%) | 12 (7.1%) | 13 (7.7%) | 87 (51.5%) | 169 |

|

Females | ||||||

| 1 | 280 (90%) | 21 (6.8%) | 8 (2.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 311 |

| 2 | 260 (83.6%) | 16 (5.1%) | 24 (7.7%) | 7 (2.3%) | 4 (1.3%) | 311 |

| 3 | 210 (67.7%) | 13 (4.2%) | 46 (14.8%) | 30 (9.7%) | 11 (3.5%) | 310 |

| 4 | 175 (57.6%) | 11 (3.6%) | 65 (21.4%) | 31 (10.2%) | 22 (7.2%) | 304 |

| 5 | 93 (37.2%) | 8 (3.2%) | 15 (6.0%) | 35 (14.0%) | 99 (39.6%) | 250 |

| 6 | 79 (30.7%) | 3 (1.2%) | 12 (4.7%) | 41 (16.0%) | 122 (47.5%) | 257 |

| 7 | 84 (34.4%) | 2 (0.8%) | 15 (6.1%) | 42 (17.2%) | 101 (41.4%) | 244 |

| 8 | 90 (37.2%) | 9 (3.7%) | 14 (5.8%) | 25 (10.3%) | 104 (43%) | 242 |

Demographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics were collected from participants at each wave. In wave 1, participants were asked to report their date of birth and sex. Participants were asked to report their mother's highest level of schooling using the following nine categories ranging from completed grade school or less, to graduate or professional school after college. These responses were recoded into five categories: 1 = completed grade school and/or some high school, 2 = completed high school, 3 = had some vocational or training school and/or some college, 4 = completed college, and 5 = attended graduate or professional school after college. Responses of “No contact” and “Don't know” were recoded as missing. We use mother's education as a proxy for SES as it is highly correlated with other measures of SES (Oakes & Rossi, 2003)

Marital status was collected at every wave. We created a dummy variable to identify whether participants had married by wave 8. Participants were also asked if they finished high school or received a GED by wave 5. This high school dropout variable was dummy coded: 0 = finished high school and 1 = did not complete high school.

Data Analysis

We conducted preliminary analyses across all study variables by comparing participants with complete data to those who were excluded from this study. Then, we used HLM 6.0 (SSI, 2004) to test the association between sexual behavior and the time-varying covariates across adolescence and young adulthood. While a repeated measures regression performs list-wise deletion for cases with missing values in one or more data points, HLM maximizes all available data because its algorithms do not require information across all waves in order to compute growth estimates (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Similar to repeated measures regressions, multilevel modeling allows the total variance to be divided into within-individual variation (Level One Model; i.e., change in sexual behavior over time) and between-individual variation (Level Two Model; i.e., individual-level characteristics).

Because this study covers two developmental periods, we parceled the growth parameters into two, grand-mean centered piecewise estimates to acknowledge the different growth rates for each period. Failure to acknowledge for different slopes within each developmental period could result in growth curve misspecification and biased estimates. The first piecewise estimate was centered on age 13 and accounted for growth during adolescence (ages 13 to 18). The second piecewise estimate was centered on age 19 and accounted for the growth during young adulthood years (ages 19−25). The quadratic term of a piecewise growth parameter was added when the outcome had a curvilinear shape. A quadratic piecewise growth estimate approximates the mean acceleration or deceleration of the outcome over the developmental period.

We also explored the single-item reliability (λ) of variables with random variation. Contrary to fixed-variation varibles, HLM assigns a single-item reliability to determine the amount of variation across individuals on the measure. This reliability coefficient is similar to Cronbach's alpha in that it is a ratio indicating the precision of the observed variation around the parameter relative to the true score (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). We provide full statistical statements only for those outcomes that achieved statistical significance to facilitate brevity. Given the number of analyses partaken, we present our data analytic strategy in each subsection of the results for clarity.

RESULTS

Sample Description

The mean age at wave 1 for the 562 African American participants was 14.5 years (SD = .60). Females composed 55% of the sample. Mother's highest educational level completed at wave 1 was as follows: 10.5% grade school or some high school, 40.8% high school, 31.8% some college or vocational training, 13.6% college, and 3.3% graduate or professional school. The high school dropout prevalence in the sample was 18%. Only 6% of youths reported getting married by wave 8. No participants reported being divorced and/or remarrying.

Attrition Analyses

Adolescent males were more likely to be excluded from the analyses than females, χ2 (1) = 26.41, p < .001. Older adolescents were also more likely to be excluded, t (679) = 5.02, p < .001. Participants excluded from the analyses were younger at first sexual intercourse, t (337) = 2.64, p < .01, had more sexual partners, t (402) = 3.12, p < .01, and reported greater sex frequency in lifetime, t (424) = 3.43, p < .001. We found no significant differences by mother's education level, high school dropout, marital status, age of their last sexual partner at wave 2, condom use at wave 1, or number of hours worked at wave 1.

Is Work Associated with Age Differences between Youth and their Sex Partners?

We first modeled the growth of the age differences between youth and their sex partners over time and included the number of hours worked across both developmental periods as a time-varying covariate. As illustrated by Path A in Fig. 1, the Hoursti covariate measured the association between the number of hours worked and age differences between youth and their sex partners over time, after adjusting for participants’ initial sex partners’ age difference mean score at age 14 and the piecewise growth estimates for the age differences over time.

In order to test for differences across individual-level characteristics (Path B in Fig.1), we allowed two terms to vary at random: the initial sex partners’ age difference at age 14 and the slope of hours worked. Variation in the initial age difference between participants and their sex partners at age 13 and/or the slope of hours worked was determined by inspecting the random effects table in the HLM output. If the intercept or the slope of hours worked varied between individuals, we explored whether individual-level characteristics (sex, mother's educational attainment, high-school dropout, and marital status) explained this variation. If individual-level variables were non-significant, they were dropped from the analyses.

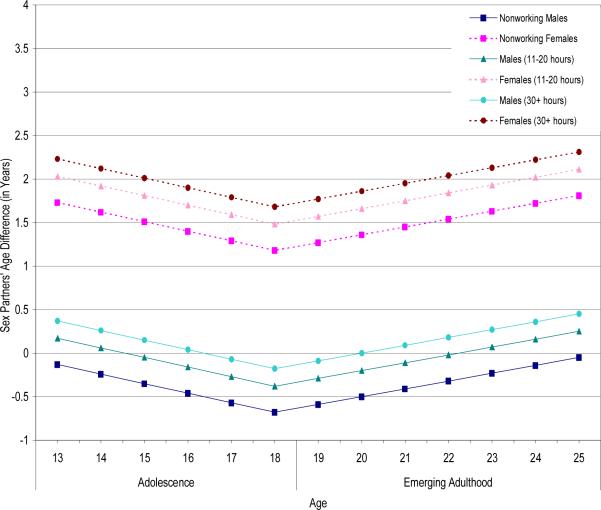

Overall, females had older sex partners across adolescence and young adulthood. The age gap, however, decreased for males and females during adolescence and increased as they transitioned into adulthood. Modeling number of hours worked on sex partners’ age differences across the adolescent and young adulthood periods suggested that, on average, youth working greater number of hours had older sex partners than counterparts working fewer hours or not working at all (see Fig. 2). This relationship, however, was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Growth Model of Number of Hours Worked on Sex Partners’ Age Differences among African American Males and Females across Adolescence and Young adulthood.

Sexually active participants reported age differences between themselves and their sex partners at age 14. The initial age difference between youth and their sex partners varied by individual-level characteristics, χ2 (501) = 1311.41, p < .01. We found initial mean scores for sex partners’ age differences at age 14 varied by participant's sex. At age 14, females reported having older sex partners than their male counterparts by almost two years, b = 1.86, p < .01. Males, however, reported having same-aged sex partners. The initial age difference did not vary by mother's education, high school dropout, or marital status. The initial difference between youth and their sex partners had a high reliability (λ = .59).

Sex partners’ age differences were best modeled with a linear term for the adolescent and young adulthood periods, respectively. During adolescence, youth reported having slightly younger sex partners, but this change over time was not statistically significant. Youth, however, had increasingly older sex partners across their young adulthood years b = 0.09, p < .01.

Inclusion of work as a time-varying covariate was not significantly associated with age differences between sex partners during adolescence and young adulthood, suggesting no support for Path A in Fig. 1. Furthermore, the slopes of hours worked on age differences did not vary by individual-level characteristics, suggesting no support for Path B in Fig.1.

Are Age Differences between Youth and their Sex Partners associated with Sexual Behavior?

To test the association over time between sexual behaviors (i.e., condom use, number of sexual partners, and sexual intercourse frequency) and sex partners’ age differences (Path C in Fig. 1), we modeled the growth of each sexual behavior and added the age difference time-varying covariate to the growth curve model.

The initial score between participants’ sexual behaviors and the association between age differences between youth and their sex partners were allowed to vary at random. If the intercept or the age difference slope varied between individuals, we explored whether individual-level characteristics (sex, mother's educational attainment, high-school dropout, and marital status) explained the variation. To avoid the loss of participants in the Level-Two analyses, we imputed missing values on mother's educational attainment, high school dropout, and marital status by giving them the sample's mean score for each variable. Following Cohen, Cohen, Aiken and West's (2002) approach, however, we created a dummy variable to adjust for a participant's imputed score. If significant, this variable was included in the final model to adjust for differences between participants with data and those whose scores were imputed. We dropped individual-level variables that were non-significant from the final models.

Sex Partners’ Age Differences and Number of Sex Partners

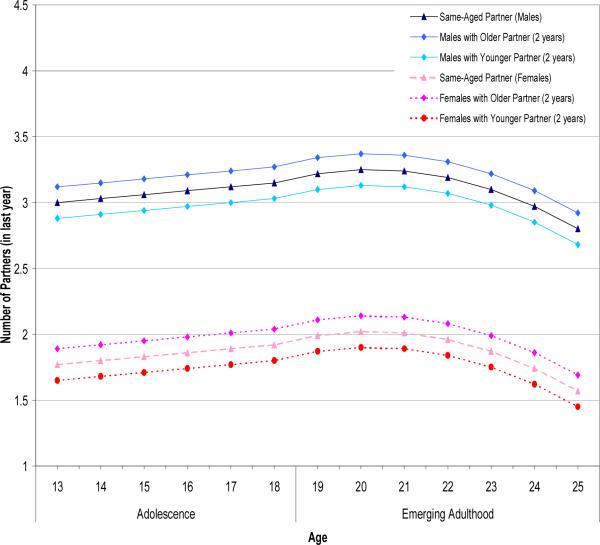

Females had fewer partners than their male counterparts across both developmental periods. As shown in Fig. 3, the number of partners was consistent across adolescence and decreased as youth got older. When we modeled youths’ sex partners’ age differences on their number of partners, we found participants with older sex partners reported a greater number of partners across adolescence and young adulthood.

Figure 3.

Growth Model of Sex Partners’ Age Differences on Number of Partners among African American Males and Females across Adolescence and Young adulthood.

Sexually active 13-year-olds reported having between one and three sex partners in their lifetime. The initial number of partners reported by youth varied by their sociodemographic characteristics, χ2 (454) = 968.13, p < .01. At age 13, females, b = −1.33, p < .01, had fewer partners than their male counterparts, b = 3.25, p < .01. The initial number of partners was not associated with their mother's education, high school dropout, or marital status. The initial number of sex partners among youth had a moderate reliability (λ = .35).

The number of partners was best modeled with a linear term for adolescence and a linear and quadratic term for young adulthood, respectively. There was no linear growth in youths’ number of partners during adolescence. There was no linear growth in youths’ number of partners during young adulthood. The curvilinear trend during the young adulthood years, however, suggested that youth had fewer partners as they entered their 20s, b = −0.02, p < .01.

Sex partners’ age differences were associated with the number of partners across adolescence and young adulthood. Participants with older sex partners reported a greater number of sexual partners over time than their counterparts with same-aged or younger sex partners, b = 0.08, p < .05. This association, however, varied by individual-level characteristics, χ2 (457) = 701.73, p < .01. The variation in the relationship between age differences and the number of partners across adolescence and young adulthood did not vary by sex, mother's education, high school dropout, or marital status.Sex partners’ age difference over time had a moderate reliability (λ = .24).

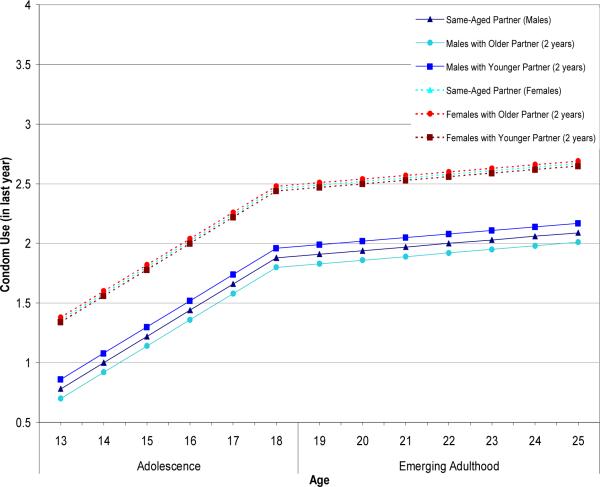

Sex Partners’ Age Differences and Inconsistent Condom Use

Overall, youth decreased their condom use across adolescence and young adulthood. Across both periods, females were less likely to report condom use than males (see Fig. 4). Youth were more likely to report condom use during adolescence than during young adulthood years. Modeling the difference in age between youth and their sex partners over time suggests that African American youth with older sex partners were less likely to report condom use than counterparts with same-aged or younger sex partners.

Figure 4.

Growth Model of Sex Partners’ Age Differences on Condom Use among African American Males and Females across Adolescence and Young adulthood.

Sexually active African Americans reported consistent condom use at age 13; however, initial condom use varied by individual-level characteristics, χ2 (471) = 882.42, p < .01. Condom use at age 13 varied by sex. Females, b = 0.59, p < .01, reported using condoms less often than males, b = 0.95, p < .01. Initial condom use did not vary by mother's educational attainment, high school dropout, or marital status. Initial condom use had a moderate reliability (λ = .39).

Condom use was best modeled with a linear term for the adolescent and young adulthood years, respectively. Although at different rates, condom use decreased during adolescence, b = 0.18, p < .01, and young adulthood, b = 0.04, p < .01.

Sex partners’ age differences were associated with condom use across adolescence and young adulthood; however, this association varied by individual-level characteristics, χ2 (471) = 644.75, p < .01. As shown in Fig. 4, we found sex differences in the association between sex partners’ age differences and condom use. Males reporting older sex partners reported more condom use over time than counterparts with same-aged or younger sex partners, b = −0.04, p < .05. The effect of sex partners’ age on condom use for females, however, was small, b = 0.06, p < .01. The relationship between condom use and sex partners’ age differences did not vary by mother's education, high school dropout, or marital status. Age differences between youth and their sex partners had a low reliability (λ = .07).

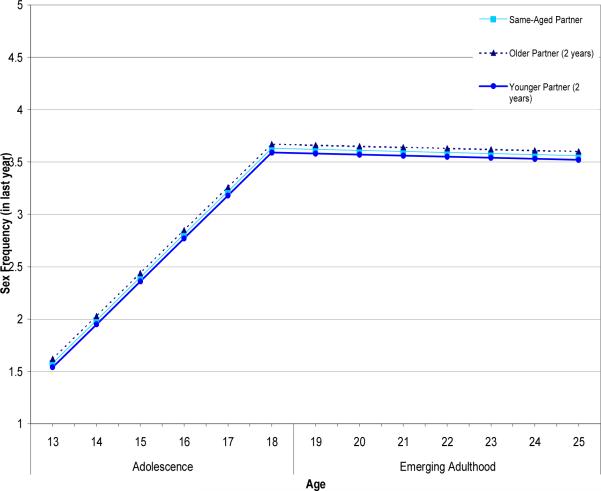

Sex Partners’ Age Differences and Sexual Intercourse Frequency

Overall, males and females increased their sex frequency across adolescence. As shown in Fig. 5, however, youth began to level off in their frequency of sexual intercourse as they entered their 20s. Modeling the effect of age difference on youths’ sexual intercourse frequency over time suggests that African American participants with older sex partners over time reported slightly greater sexual intercourse frequency than counterparts with same-aged or younger sex partners.

Figure 5.

Growth Model of Sex Partners’ Age Differences on Sexual Intercourse Frequency among African Americans across Adolescence and Young adulthood.

On average, 13 year-old sexually active participants reported having had sex on more than one occasion in their lifetime. The frequency of sexual intercourse across their lifetime, however, varied by individual-level characteristics, χ2 (476) = 1001.40, p < .01. Sex, mother's educational attainment, high school dropout, or marital status did not explain differences in the initial score for lifetime sex frequency. Initial sexual intercourse frequency had a moderately high reliability (λ = .44).

Sex frequency over time was modeled with a linear growth term for the adolescent and young adulthood periods, respectively. Youths’ sex frequency increased during adolescence, b = 0.38, p < .01, and during young adulthood, b = 0.03, p < .01.

The age gap between youth and their sex partners was associated with sex frequency over time. Youth who had older sex partners over time reported slightly higher sex frequency than counterparts with same-aged or younger sex partners, but this association was not statistically significant. This relationship, however, varied by individual-level characteristics, χ2 (476) = 708.66, p < .01. None of the demographic characteristics, however, explained the differences in the slopes of age differences’ effect on sexual intercourse frequency across the adolescent and young adulthood. Sex frequency across adolescence and young adulthood had a low reliability (λ = .14).

Do Age Differences Mediate the Relationship between Work and Sexual Behaviors?

To test for the mediation of age differences in the relationship between number of hours worked and sexual behaviors across adolescence and young adulthood, we used Sobel's test (MacKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995a & 1995b) by assessing whether the Hoursti covariate had an indirect effect on the sexual behavior outcomes through AgeDifferencesti, after controlling for the direct effect of Hoursti on AgeDifferencesti.

Mediation Model 1: Age Difference, Work, and Number of Partners

Inclusion of number of hours worked into the model was not significantly associated with number of sex partners. Based on the non-significant Sobel test, sex partners’ age differences did not mediate the relationship between the number of hours worked and number of partners across adolescence and young adulthood.

Mediation Model 2: Age Difference, Work, and Condom Use

Inclusion of number of hours worked into the model was not significantly associated with condom use, after adjusting for sex partners’ age differences. Based on the non-significant Sobel test, we found no mediation between the number of hours worked and condom use through sex partners’ age differences across adolescence and young adulthood.

Mediation Model 3: Age Difference, Work, and Sexual Intercourse Frequency

Youth working greater number of hours across adolescence and young adulthood had greater sex frequency growth than counterparts working fewer hours or not working at all, b = 0.05, p < .05, after adjusting for sex partner age differences. Based on the non-significant Sobel test, however, we found no evidence to suggest that sex partners’ age differences mediated the relationship between the number of hours worked and sex frequency across adolescence and young adulthood.

DISCUSSION

Participation in the labor force may be an opportunity for youth to establish their financial independence from their parents and their partners. Our study's aims were (a) to explore whether workforce participation, as measured by the number of hours worked, was associated with sex partners’ age differences, (b) to assess the association between sex partner age differences and sex behaviors, and (c) to determine if sex partner age differences was a confounder in the relationship between workforce participation and sex behaviors.

Youths’ participation in the labor force (e.g., number of hours worked) across adolescence and young adulthood was not associated with older sex partners. Our findings linking participation in the labor force and sex partner age differences, however, should be interpreted with caution. The absence of a direct association between these two variables does not eliminate he possibility of a more intricate causal pathway. While number of hours worked was not associated with sex partner age differences, other work characteristics (e.g., job earnings, job type, job satisfaction, or time of day when youth work) may elucidate other associations between these variables (Mortimer, 2003). Future research exploring the association between working and youth's transition into adulthood differs by occupation, earnings, and the quality of work itself may also help understand the contexts where work may be associated with sex partner age differences.

The association between sex partners’ age difference and sexual intercourse frequency and number of partners was similar for males and females. Youth reported greater intercourse frequency and number of partners with every additional year difference between their older partners and themselves. The association between sex partners’ age differences and condom use, however, had different effects for males and females. African American males reported less condom use if they were older than their sex partners over time, with the effect increasing as the age difference widened. African American females, however, reported more condom use if they were older than their sex partners. It is important to note, however, that females reported less condom use than males, even when they reported same-aged partners across adolescence and young adulthood. It may be possible that being the older sex partner is associated with increased sexual relationship power, self-esteem, and self-efficacy to use condoms. This interpretation of our study findings would support a theory of gender and power interpretation (Wingood & DiClemente, 2002) because sexual power imbalances may increase if females have older sex partners. African American females with younger male partners, however, might feel more confident to negotiate equitable sexual relationships across adolescence and young adulthood. On the other hand, a counterargument may be that females reported lower condom use during adolescence and young adulthood because they preferred to use other reproductive health technologies such as birth control. Unfortunately, we were unable to measure sexual relationship power or contraceptive use, making these interpretations as tentative. Future research should explore whether African American females having sexual relationships with younger males have different communication and safer sex negotiation skills, or may opt to use other reproductive health technologies such as contraceptives, than their counterparts with similar or older sex partners. Future research that explores youths’ social relationships in detail may help understand these age-disparate relationships more clearly and inform youth prevention programs.

Inclusion of the number of hours worked as a covariate in the growth curve models had additive effects on sexual intercourse frequency, even after accounting for sex partners’ age differences. Working greater number of hours during adolescence and young adulthood was associated with more sexual intercourse across adolescence and young adulthood, after adjusting for the age gap between youth and their sex partners. One potential interpretation for these findings is that, as labor force participation increases youth become more financially independent and may begin to settle down and marry. Nonetheless, this interpretation was not supported by the data: intercourse frequency did not vary by marital status given that only a few participants reported being married across the 8 waves. It may be necessary to replicate these findings in other longitudinal datasets where additional young adulthood years (e.g., 25 to 35) are available.

As a note of caution, it is important to highlight that the associations found between work and sexual activity could be confounded by adolescents’ motivation to work. For example, an adolescent's decision to work because he/she needs to contribute to the household income may place him/her in a different work trajectory than an adolescent who decides to work in order to buy his/her first car and assert his/her independence. Consequently, the associations found between different work trajectories and sexual activity may disappear once youths’ motivations for working have been included in the analyses. While we tested for differences across socioeconomic status, family structure, and academic achievement, we cannot rule out other alternative explanations.

Several additional limitations should be noted. First, the study's findings may not be generalizable because participants in this study were recruited based on their risk for school dropout (e.g., GPA lower than 3.0 during eighth grade). Nonetheless, previous studies with the same sample have found adolescents had a more even distribution of GPA by wave 4 (12th grade) of the study (Zimmerman, Caldwell, & Bernat, 2002), making it comparable to other datasets. Second, we were unable to account for the quality or type of job that adolescents worked while in high school (Mortimer et al., 2002). Work type, wages, and quality may help identify differences in adolescent work and development. Adolescents working poor quality jobs, for example, may differ from those working in higher quality jobs, regardless of work intensity. Future research exploring how these factors may mediate or moderate the work and developmental transitions relationship would be useful. This work will be essential in order to inform policy initiatives adequately Third, the attrition analyses also suggest that youth engaging in the most risky behaviors were excluded from the longitudinal analyses due to missing data. The sample included in the analyses, however, did report a wide range of sexual behaviors that were not widely skewed. Finally, several HLM analyses had weak single-item reliability. While this restricted reliability could lead to finding null effects, our ability to find effects suggests that, in a worst case scenario, the associations presented may be attenuated.

These limitations not withstanding, this study builds on knowledge of youth's sexual behaviors in several ways. First, researchers studying sex partners’ age have included African American samples, but haven't had sufficiently large sample size to do within-race analyses. Instead, they have pooled White Americans and Black Americans and adjusted race using a dummy variable (Ford & Lepkowski, 2004; Kaestle et al., 2002). Second, the availability of data for participants across 8 waves allowed for the prospective exploration of the relationship of between sex partners’ age differences and sexual behaviors across adolescence and the transition into young adulthood. This information may help inform HIV/STI prevention as well as youth development programs. Third, this study contributes to this body of literature by proposing a continuous and dynamic measure that accounts for differences between age of partner and youth over time rather than using a categorical and static measure of sex partners’ age differences. Finally, we tested the effects of working and sex partners’ age differences on African American adolescents’ sexual behaviors. This is especially critical because scarce work has been proposed in this area without acknowledging that age differences may confound these relationships. We hope our results contribute to the larger body of research discussing labor force participation as a structural intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention programs (Greig & Koopman, 2003; Sherman, German, Cheng, Marks, & Bailey-Kloche, 2006).

Is work beneficial for youth's sexual behavior? Our results seem to suggest that working during adolescence and young adulthood may promote greater sexual exploration among African American youth. It is important to note, however, that this sexual exploration may not translate into sexual behavior. Few participants in our sample reported having a STI, being pregnant, or having children across our 8 waves of data; thus, we were unable to predict the association between youth's sexual behavior with these outcomes. Replication of our analyses with other samples where there is a greater variability in STI and pregnancy outcomes is needed before discarding labor force participation as a prevention strategy.

Overall, we are unable to conclude that the mixed findings between work's effects on youth sexual behavior results from the mediation of older sex partners. Instead, we find evidence to suggest that older sex partners during adolescence and young adulthood may increase sexual intercourse frequency, especially if youth are working greater number of hours. Sex education programs and preventive efforts for adolescents and young adults may benefit by discussing how sex partner characteristics may increase sexual behaviors. The findings underscore the importance of adapting health promotion materials to working youth and including strategies for sexual negotiation, especially for youth who may have sexual relationships with older partners, as they transition from adolescence into young adulthood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse to the University of Michigan School of Public Health (Grant Number R01- DA07484; Principal Investigator: Marc A. Zimmerman, Ph.D.) and a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at NY State Psychiatric Instititute and Columbia University (T32-MH19139 Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Prevention; Principal Investigator, Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D.).

Footnotes

CITATION: Bauermeister, J.A., Zimmerman, M., Xue, Y., Gee, G., & Caldwell, C. (In press). Working, sex partner age differences, and sexual behavior among African American youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior. Available online.

REFERENCES

- Anderson JE, Brackbill R, Mosher WD. Condom use for disease prevention among unmarried US women. Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;28:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Barnett T, Caldwell C. Working in high school and the transition to adulthood among African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster LK. Neighborhood context and the transition to sexual activity among young black women. Demography. 1994;31:603–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2004 HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Vol. 16. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Gender and power. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Coverdill JE, Kraft JM. Enrollment, employment, and the risk and resolution of a first premarital pregnancy. Social Science Quarterly. 1996;77:43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz T, Chu SY, Buehler JW, Boyd D, Checko PJ, Conti L, et al. Socioeconomic differences among people with AIDS: Results from a Multistate Surveillance Project. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Sionean C, Crosby RA, Harrington K, Davies S, et al. Association of adolescents’ history of sexually transmitted disease (STD) and their current high-risk behavior and STD status; a case for intensifying clinic-based prevention efforts. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:503–510. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Lepkowski JM. Characteristics of sexual partners and STD infection among American adolescents. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2004;15:260–265. doi: 10.1258/095646204773557802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT. Understanding and eliminating racial inequalities in womenfemales's health in the United States: The role of the weathering conceptual framework. Journal of the American Medical WomenFemales's Association. 2001;56:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA. Health inequality and population variation in fertility-timing. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;49:1623–1636. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Steinberg L. When teenagers work: The psychological and social costs of adolescent employment. Basic Books; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Greig FE, Koopman CK. Multilevel analysis of women's empowerment and HIV prevention: Quantitative survey results from a Preliminary Study I Botswana. AIDS & Behavior. 2003;7:195–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1023954526639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E. Gender, work control and stress: A theoretical discussion and an empirical test. In: Johnson JV, Johansson G, editors. The psychosocial work environment: Work organization, democratization and health. Baywood; Amityville, NY: 1991. pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Morisky DE, Wiley DJ. Sexual intercourse and the age difference between adolescent women and their romantic partners. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34(6):304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft JM, Coverdill JE. Employment and the use of birth control by sexually active single Hispanic, Black, and White women. Demography. 1994;31:593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995a;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures: Erratum. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995b;30(3):ii. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT. Work and growing up in America. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JM, Rossi PH. The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:769–784. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Grinstead OA, Golden E, Catania JA, Kegeles S, Coates TJ. Correlates of HIV risk behaviors in black and white San Francisco heterosexuals: The population-based AIDS in Multiethnic Neighborhoods (AMEN) study. Ethnicity and Disease. 1992;2:361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Second ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rich LM, Kim SB. Employment and the sexual and reproductive behavior of female adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort T, Orr M, Hirsch JS, Santelli J. Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: Results from a national US study. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:155–161. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Software International . Hierarchical Linear Models (version 6.01). SSI Inc.; Chicago: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JD, Cassell MM, Adetunji J. Is poverty or wealth at the root of HIV? Lancet. 2005;366:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, German Y, Cheng M, Marks M, Bailey-Kloche M. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: An innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug using females involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006;18:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbereisen RK, Kracke B. Self-reported maturational timing and adaptation in adolescence. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1997. pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Mortimer JT, Uggen C. Work and leisure in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Second Ed. Wiley; Hoboken: 2004. pp. 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics The employment situation: June 2004. 2004 Accessed from the World Wide Web on July 8, 2004 at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

- Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Janssen RS, Hayman CR. HIV infection in disadvantaged out-of-school youth: prevalence for U.S. Job Corps entrants, 1990 through 1996. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome and Human Retrovirology. 1998;19:67–73. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199809010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Relationship characteristics associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26:29–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1021830023545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The Theory of Gender and Power: A social structural theory for guiding public health interventions. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: Strategies for improving public health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. pp. 313–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH, Bernat DH. Discrepancy between self-report and school-record grade point average: Correlates with psychosocial outcomes among African American adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:86–109. [Google Scholar]