Abstract

IRF8, a transcription factor restricted primarily to hematopoietic cells, is known to influence the differentiation and function of dendritic cells (DC), macrophages, granulocytes and B cells. In human tonsil, IRF8 is expressed at high levels by intrafollicular macrophages and DC, but at much lower levels by tingible body macrophages in germinal centers (GCs) and little, if at all, by follicular DC. Spleens of IRF8-defficient mice had reduced numbers of white pulp follicles and GCs that were irregular in shape. The frequency of follicular B cells was significantly reduced while the population of marginal zone (MZ) B cells was increased. In addition, MZ macrophages were reduced in number and abnormally distributed, while metallophilic macrophages were normal. These findings demonstrate differential requirements for IRF8 among distinct subsets of B cells, DC, and macrophages.

Keywords: Germinal center, Follicular dendritic cells, B cells, IRF8

Introduction

During the adaptive immune response, the microarchitecture of lymphoid organs facilitates effective communication between antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DC), B cells, and effector T cells in order to mount an effective defense against specific pathogens [1]. The marginal sinus, separating the red and white pulp areas, defines the marginal zone (MZ) where specialized subsets of macrophages, B cells, and DC interact with cells leaving the bloodstream and entering the white pulp and the germinal centers (GCs) [2, 3]. The GC reaction is complex, involving crosstalk among B cells, CD4+ follicular T helper (FTH) cells, and follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) as well as extensive trafficking between the centroblast-rich dark zone and the centrocyte-, FDC-, and FTH-rich light zone [4, 5].

FDCs are a critical element of the GC reaction [6]. Unlike other subsets of DC, they do not derive from bone marrow cells and their development is dependent on their expression of TNFR1 and expression of LTA by bone marrow-derived cells, with B cells perhaps being of greatest importance [7]. In mice, both B and T cells are essential for the development of FDCs. GC formation is defective in mice deficient in CD40 or CD40L and in athymic mice. Regulation of various FDC activities is dependent on different signaling pathways downstream from TNFR1, and IKK2 is required for upregulation of VCAM-1/ICAM-1 expression and the generation of productive GCs [8].

Interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP)/interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8) is a member of the IRF family of transcription factors. While many family members are expressed ubiquitously, expression of IRF8 is mostly limited to hematopoietic cells including myeloid cells, T and B cells, erythroid elements, and DC and NK cells. Mice homozygous for a null allele of IRF8 (IRF8−/−) are immunodeficient and exhibit a marked expansion of granulocytes terminating in a disease with similarities to human chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) [9]. More recently, it was found that BXH2 mice, which develop a high frequency of myeloid leukemias, bear a point mutation in IRF8 [10] but that their disease has distinct differences from that of IRF8−/− mice [11].

Data from a large number of studies comparing IRF8−/− and wild type (IRF8+/+) mice have shown that IRF8 plays important roles in regulating the differentiation and function of hematopoietic populations via activation or repression of target genes [12] with much of the attention being focused on DC [13]. IRF8 governs the maturation and function of Langerhans cells as well as other subsets of myeloid and non-myeloid DC [14–17]. In addition, IRF8 differentially controls antigen uptake and MHC class II presentation in defined DC subpopulations [14].

Studies of B lineage cells have shown that IRF8, IRF4 (another member of the IRF family), and PU.1 act collaboratively to activate immunoglobulin (Ig) light chain activation and the pre-B to B cell transition [18, 19]. Recently, we showed that IRF8 is differentially expressed in mature B cells with low levels of expression in naïve cells, marked upregulation of expression in GC B cells, followed by a striking downregulation during terminal plasma cell differentiation [20]. In addition, we showed that IRF8 is involved in the transcriptional regulation of two critical GC genes, BCL6 and activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). Previous histologic studies of IRF8−/− mice revealed abnormalities of GC structure, but it was not possible to determine if this abnormality was B cell intrinsic as IRF8 is normally expressed to some extent in almost all splenic cells.

The present study was directed at determining the mechanisms that might contribute to GC B cell abnormalities in IRF8-deficient mice by clarifying the patterns of IRF8 expression among different types of spleen cells with an initial focus on FDC, a cell type critically involved in GC development and activity [21]. The results showed that FDCs of mice and humans express very little if any IRF8, indicating that B cell-intrinsic defects or B cell abnormalities induced by other IRF8-positive spleen cell subsets contributed to the GC abnormalities. Indeed, we identified abnormalities in the relative distributions of follicular and MZ B cells of IRF8-deficient mice and selective effects of IRF8 deficiency on macrophage subsets that flank the marginal sinus. These data indicate that expression of IRF8 has differential effects not only on subsets of DC, as previously shown, but also on subsets of splenic B cells and macrophages. Since we found FDCs to be IRF8-negative, it is likely that the combined effects of IRF8-deficiency on other cell subsets determine the GC abnormalities identified in IRF8 knockout mice.

Materials and methods

Human tonsil samples

Human tonsil specimens were obtained from the files of the Hematopathology Section, Laboratory of Pathology of the NCI (Bethesda, Maryland).

Mice and tissue collection

C57BL/6 J (B6) mice (IRF8+/+) (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were crossed with IRF8 knockout mice (IRF8−/−) [9] on a B6 background (kindly provided by Dr. Keiko Ozato NICHD, NIH) to generate IRF8+/+, IRF8+/−, and IRF8−/− mice. The mice were studied at 7 to 12 weeks of age. At necropsy, samples from spleen and lymph node were frozen in OCT or fixed in formalin for histologic study or prepared for use in flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy

For IRF8 immunohistochemistry studies of human tonsil samples, formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue sections were used, and the staining was performed as previously described [22]. Lymphoid tissues of mouse samples in OCT were sectioned at 4 μm. The sections were fixed in acetone for 15 min and then air dried for 30 min before blocking with 5% horse serum for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were then stained with antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Alexa fluor dyes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used for fluorescence conjugations: Alexa 488 (green), Alexa 350 (blue), Alexa 555 (red), and Alexa 647 (magenta). The sections were mounted in fluomount G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and viewed with a Leica/Leitz microscope and a confocal microscope. For analysis of mitotic features, tissues were embedded in paraffin fixed in neutral buffered formalin and cut into 3 μm sections. The sections were stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), TUNEL, and anti-Ki67.

Flow cytometric (FACS) analyses

Single cell suspensions were prepared from spleens of WT and IRF8−/− mice. Cells were stained with FITC-, PE-, allophycocyanin (APC)-, or percp-conjugated antibodies specific for mouse B220, IgM, CD21, and CD23 (BD-Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) flow cytomoter. Data were representative of more than five independent experiments and analyzed with WinMDI software (Scripps Institute, La Jolla, CA).

Results

IRF8 expression in human tonsil and mouse spleen samples

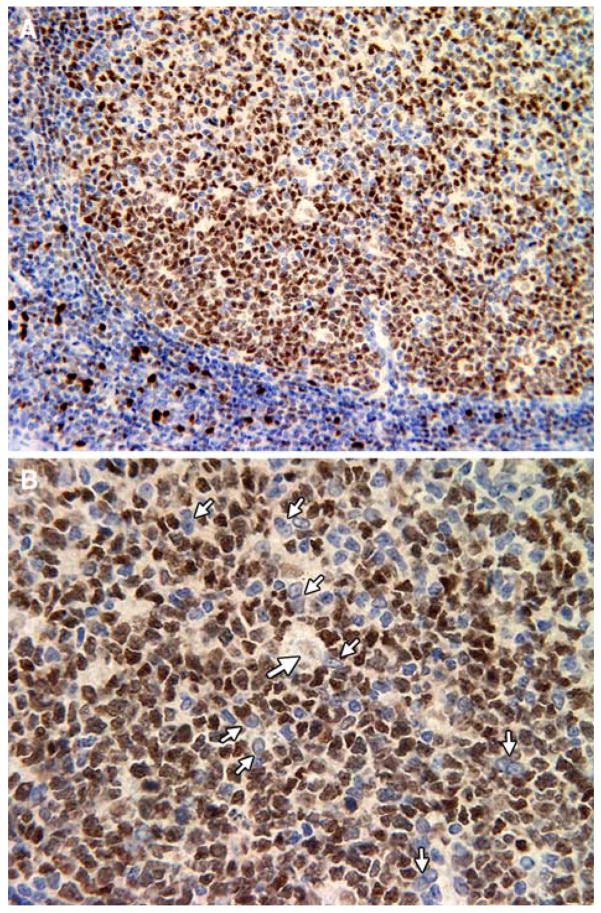

We first studied IRF8 expression patterns in human tonsil by IHC using paraffin-embedded tissue sections (Fig. 1). The most intense IRF8 staining was seen in nuclei of mononuclear cells in the parafollicular and paracortical T cell zones (Fig. 1a and b) that were previously identified as being macrophage in origin [23]. In B cell follicles, the most intense staining was seen in GC dark zones, consistent with high level expression in centroblasts [20, 23, 24], although the levels were significantly lower than in paracortical macrophages (Fig. 1a and b). Interestingly, tingible body macrophages, a distinct mature macrophage subset found in GCs, expressed only very low levels of IRF8 (Fig. 1c, large arrows). In contrast, FDCs (small arrows) appear to be IRF8-negative or to express IRF8 below the level of detection afforded by IHC. These studies indicated that IRF8 is differentially expressed in anatomically and functionally distinct subsets of macrophages and that FDCs, in contrast to plasmacytoid and other dendritic cell subsets [17], do not express IRF8. The absence of IRF8 from FDCs might be considered predictable, given their origins from non-bone marrow-derived cells [7].

Fig. 1.

Anti-IRF8 IHC staining of Human tonsil samples. Large arrows show tangible body macrophages, small arrows show FDCs

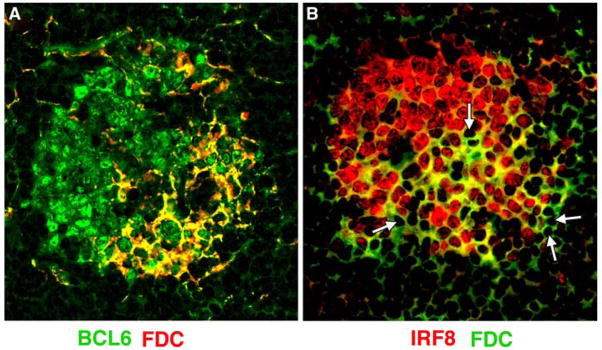

To determine if similar relationships exist among cell subsets in normal mouse spleens, we next used confocal microscopy to evaluate GCs from these mice using antibodies to IRF8, BCL6, and the FDC marker, FDC-M1 (Fig. 2). The results of these studies showed intense staining of dark zone centroblasts with both antibodies to both IRF8 and BCL6 while the FDC-rich area contained smaller cells that stained intensely with both reagents. Importantly, the nuclei of FDCs appeared to be IRF8-negative (Fig. 2b, arrow heads). Finally, tingible body macrophages, as in human GCs, expressed only very low levels of IRF8 (data not shown). We conclude that variations in expression of IRF8 among subsets of macrophages and DC are conserved in humans and mice.

Fig. 2.

Confocal microscopic analyses of GCs from IRF8+/+(+/+) and IRF8−/− (−/−) spleens for expression of BCL6 and FDC-M1. The merged images are shown at the bottom

Effects of IRF8 deficiency on splenic B cell populations

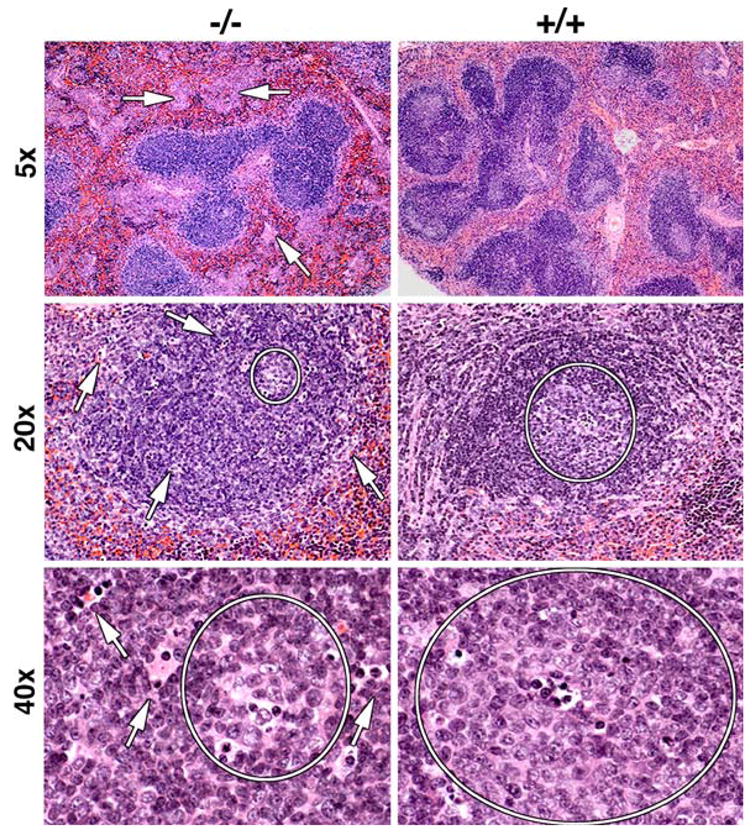

To determine how a lack of IRF8 might affect the features of cells that are normally IRF8-positive, we studied spleens of mice homozygous for a null mutation of IRF8 [9]. Analyses of lymphoid tissues showed that the white pulp area in spleens from IRF8−/− mice was reduced in size due to the presence of fewer and smaller follicles (Fig. 3, 5×). As reported previously, the spleens of knockout mice also had large interfollicular accumulations of myeloid cells (arrowheads). In addition, the number of GCs in spleens of IRF8−/− mice was significantly reduced. (Fig. 3, 5×, 20×; Table 1). GCs in IRF8−/− spleens were often irregular in shape and less uniform in their content of blast cells (Fig. 3, 20×, 40×). In addition, the follicles of IRF8−/− spleens exhibited isolated apoptotic cells and tingible body macrophages residing outside the GCs (arrows), while these features were essentially limited to GCs in spleens of WT mice. Unexpectedly, in spite of the reductions seen in white pulp size, the marginal zones (MZ) of IRF8−/− mouse spleens were increased approximately twofold in size over normal.

Fig. 3.

H&E staining of spleens from IRF8+/+(+/+) and IRF8−/− (−/−) mice. Original magnifications are indicated to the left. Germinal centers are circled in the lower four panels and arrows point to apoptotic bodies localized outside germinal centers

Fig. 5.

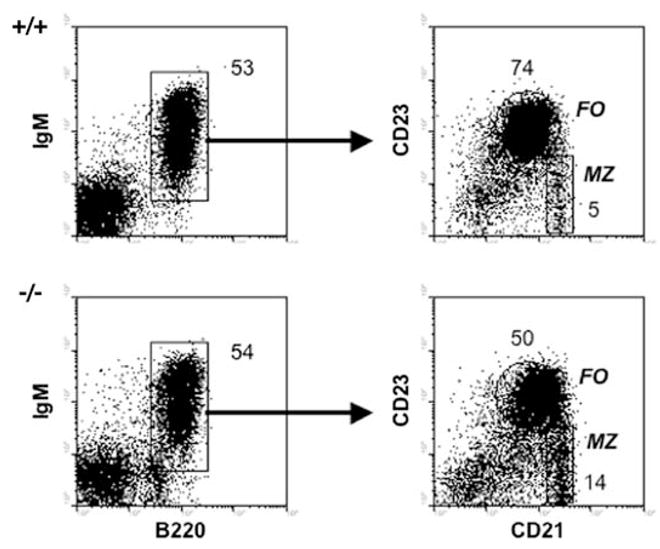

FASC analyses of spleen cells from IRF8+/+(+/+) and IRF8−/− (−/−) mice. The left panels, gated to show lymphocytes, show results obtained with antibodies to IgM and B220 and the gates used for characterization of B cells for expression of CD21 and CD23 shown in the right panels. Numbers in the right panel indicate the percentages of total B cells. In the right panels, the gates for follicular (FO) B cells (CD23hiCD21lo) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells (CD23lo/−CD21hi) are indicated together with the percentages of cells falling in the gates. Data are representative of five or more independent experiments

Table 1.

Quantitation of follicles and germinal centers in spleens and lymph nodes from normal and IRF8−/− mice

| Genotype | Follicles persection |

Germinal centers persection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | Lymph node | Spleen | Lymph node | |

| IRF8+/+ (n = 38) | 10 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| IRF8−/− (n = 22) | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 |

Number indicate the mean ± 1SD

Interestingly, in lymph nodes of IRF8−/− and WT mice, B cell follicles and GCs were similar in number and size (Table 1). Similar to spleens of IRF8−/− mice, however, apoptotic cells were seen frequently outside GCs (data not shown). A deficiency in IRF8 thus appeared to have greater effects on follicular and GC structures in spleens than in lymph nodes.

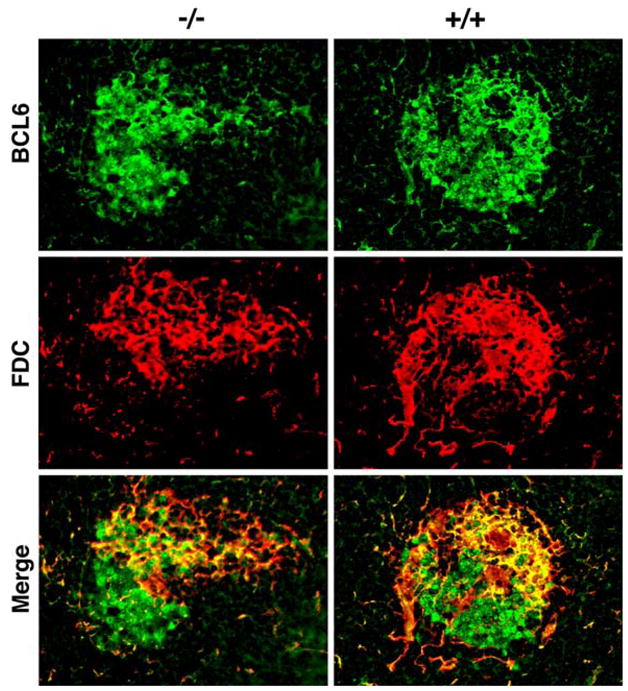

To further examine the characteristics of the white pulp in spleens of RF8-deficient mice, we used confocal microscopy to study the relationships of GC B cell subsets stained with antibodies to BCL6 and follicular dendrites stained with antibody to FDC-M1 in order to identify FDCs (Fig. 4). The germinal centers of knockout mice tended to be irregular in shape, as noted above, but were similar to those of wild type mice. Both had substantial populations of centroblast-like cells staining intensely with BCL6 although cells of this phenotype appeared to be less tightly bunched than in germinal centers of wild type mice. Smaller, less intensely staining populations of cells more closely associated with FDCs presumably reflect the population of centrocytes.

Fig. 4.

Confocal microscopic analyses of normal spleen co-stained with antibodies to anti-IRF8 and FDC-M1. The merged images are shown at the bottom

The observation that the MZ of IRF8−/− appeared to be larger than those of normal mice prompted us to examine features of splenic B cells by flow cytometry (FACS) (Fig. 5). After gating on lymphocytes, the proportions of mature B cells, defined by expression of B220 and IgM, were the same in mice of both genotypes. Studies of the B220+IgM+ B cell subsets were then performed, using antibodies to CD23 and CD21 to define follicular B cells (CD23hiCD21lo) and MZ B cells (CD23lo/−CD21hi). These studies showed that the proportions of follicular B cells were reduced by ~33% in the spleens of IRF8-deficient mice while the proportions of MZ B cells were increased almost threefold. These results suggested that expression of IRF8 in maturing B cells of normal mice favors the generation of follicular B cells over marginal zone B cells.

Characteristics of FDCs in spleens of IRF8 knockout mice

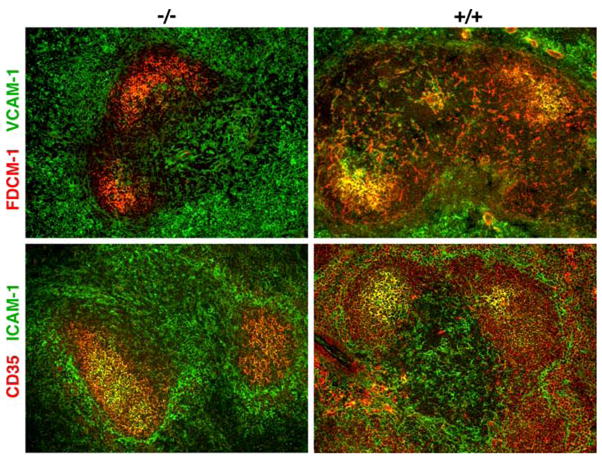

The indications that FDCs of both humans and mice are IRF8-negative could be taken to suggest that the abnormal features of splenic GCs seen in IRF8 knockout mice are unlikely to be due to abnormalities of FDCs. However, FDCs in IRF8-deficient mice develop in the presence of Th2 polarized T cells and activated B cells that characterize the spleens of these mutants [9]. To determine if this abnormal environment might result in alterations in their phenotypes we used confocal microscopy to compare FDCs from knockout and normal mice for their expression of FDC-M1, VCAM-1, CD35, and ICAM-1 (Fig. 6). Previous studies showed that the survival of antigen-specific B cells during the GC reaction is strongly promoted by close contact between B cells and FDCs and is mediated in good part by interactions of VLA-4/VCAM-1 and LFA-1/ICAM-1 [25–28]. The results of these studies showed that FDCs from wild type and knockout mice, marked by expression of FDC-M1 or CD35, coexpressed ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 at similar levels (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Confocal microscopic analyses of GCs from IRF8+/+(+/+) and IRF8−/− (−/−) spleens for expression of the indicated pairs of cell surface markers

Characteristics of the MZ sinus and flanking populations of metallophilic and MZ macrophages in spleens of IRF8-deificient mice

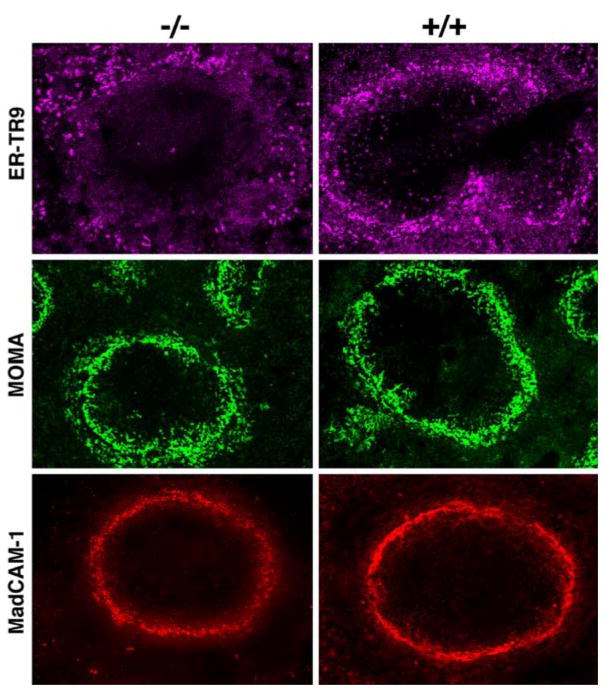

We showed previously that the MZ B cell population was significantly increased among B cells in spleens of IRF8 knockout mice. MZ B cells are separated from the white pulp by the marginal sinus and are intermingled with a specialized population of macrophages, termed MZ macrophages. Another subset of specialized macrophages, termed metallophilic macrophages, lies just to the white pulp side of the marginal sinus. We were interested in studying these populations from two perspectives. First, since IRF8 is differentially expressed among macrophage subsets in human tonsil, would a deficiency in IRF8 differentially affect subsets of mouse macrophages? Second, the relationship between MZ macrophages and MZ B cells is strikingly interdependent such that MZ macrophages are absent from mice without MZ B cells and that mice lacking MZ macrophages do not have MZ B cells [29, 30].

Altered signaling in MZ macrophages can result in reorganization of the macrophages to the red pulp and migration of MZ B cells into follicles [29]. The fact that IRF8 is expressed at high levels in macrophages raised the possibility that the organization and function of MZ macrophages or metallophilic macrophages might be altered in IRF8-deficient mice. Therefore to examine if the macrophage populations specific to the white pulp and MZ might be selectively altered in IRF8 knockout mice, we studied spleens of wild type and knockout mice for expression of markers for marginal sinus endothelial cells (MadCAM-1) [31], for metallophilic macrophages (MOMA-1), and for MZ macrophages (ER-TR9) (Fig. 7). In spleens of wild type mice (Fig. 7), the expression of these markers was as described previously. Furthermore, the expression patterns of MadCAM-1 and MOMA-1 in spleens of knockout mice were similar to those seen in spleens of normal mice. In contrast, the close association of ER-TR9 with the MZ in normal spleens was not seen in spleens of the knockouts. While some ER-TR9-positive cells were associated the MZ, as in wild type mice, there were gaps in which the MZ was devoid of these cells and other areas where the cells radiated out from the MZ into the red pulp (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Confocal microscopic studies of GCs from IRF8+/+(+/+) and IRF8−/− (−/−) mice for expression of ERTR-9 on MZ macrophages, MOMA-1 on metallophilic macrophages, and MadCAM-1 on marginal sinus endothelial cells and activated FDCs

Previous studies showed that mice deficient in the negative signaling inositol phosphatase, SHIP, lack MZ B cells and that MZ macrophages are redistributed into the red pulp [29]. These features were the same in mice with either a conventional knockout or a macrophage-specific knockout of the gene, Using immunohistochemical staining, we found that SHIP is expressed at comparable levels in MZ macrophages from spleens of normal and IRF8−/− mice (data not shown), indicating that the effect of IRF8 deficiency on MZ macrophages cannot be ascribed to impaired expression of SHIP.

These studies supported the suggestion taken from the studies of human tonsil that IRF8 may play distinct roles in subsets of macrophages. In mouse spleen the numbers and distribution of MOMA-1-expressing metallophilic macrophages appear to be the same in mice either competent or deficient in IRF8. In contrast, the frequency and distribution of MZ macrophages were significantly altered in the knockouts. It seems possible that these changes in MZ macrophages could contribute to the changes observed in the MZ B cell population of IRF8-deficient mice. Alternatively, the altered distribution of MZ macrophages could be secondary to changes intrinsic to the MZ B cell population. The availability of conditional IRF8 knockouts could be critical for distinguishing between these possibilities.

Discussion

For many years, both IRF8 and IRF4 were considered to be exclusive to immune cells of hematopoietic origin. Nonetheless, a number of studies have shown that IRF8 is expressed in a variety of non-lymphoid tissues including the mouse lens [32, 33], developing mouse brain [34], human retinal pigment epithelial cells [35], mature human spermatozoa [36], a human osteosarcoma cell line [37], and human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines [38, 39]. Studies of both human and mouse FDCs showed them to be IRF8-negative, a contrast with other subpopulations of DC and Langerhans cells. By studying IRF8 knockout mice, it was found that FDCs of the knockout mice express a series of surface molecules at levels similar to those found on FDCs of normal mice and that they maintain a generally similar relationship to subsets of GC B cells. As a result, there is no clear indication that FDCs contribute to abnormalities of GC frequency or structure in spleens of knockout mice. We cannot rule out the possibility that these changes may be attributable to reduced populations of follicular B cells that may be phenotypically but not functionally normal.

The induction and maturation of FDC networks and GCs are dependent on expression of p55TNFR on FDC precursors and TNF family members on B and T cells [7, 8]. Our results suggest that a FDC-independent IRF8 signaling pathway absent in IRF8-deficient mice is responsible for abnormalities of GCs but not FDCs in both spleens and lymph nodes of IRF8−/− mice. Although GC and FDC networks tend to be more normal in size in lymph nodes than in spleens of the knockouts, the GCs in both tissues are more irregular in shape and exhibit an increase in apoptosis and tingible body macrophages outside the GCs. These differences could be due to changes in IRF8-dependent mechanisms in B cells or T cells that also normally express IRF8, but where IRF8 functions remain incompletely explored. The preservation of FDC function in the GC reactions of knockout mice may be due to the fact that CD35, FDC-M1, MAdCAM-1, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 are expressed at levels comparable to those of FDCs from wild type mice.

Macrophage subsets in humans and mice are distinct for their expression of IRF8 and their requirements for expression of the transcription factor. In humans, interfollicular macrophages express IRF8 at substantially higher levels than tingible body macrophages and similar observations were made in mice. In mice deficient in IRF8, metallophilic macrophages occupy their appropriate niche in normal numbers, yet MZ macrophages distribute abnormally and also appear to be altered in numbers.

Previous studies demonstrated that IRF8 preferentially directs myeloid progenitor cells into the monocytic-macrophage differentiation pathway while repressing granulocyte-specific genes [40]. Our analyses of IRF8−/− mice indicate that the roles played by IRF8 in directing macrophage differentiation are not uniform among distinct subsets of these cells. This is evidenced most clearly by the differing consequences of IRF8 deficiency for metallophilic macrophages as compared MZ macrophages. The phenotype of IRF8−/− mice, an altered distribution and number of MZ macrophages in association with a normal to increased population of MZ B cells, is much like that seen in plt/plt mutant mice that lack CCL19 and CCL21 [41]. Studies of mice with a conditional knockout of IRF8 in macrophages will be required to tell if the different effects of the conventional knockout on macrophage subsets is cell intrinsic.

IRF8-deficient mice showed an expanded population of MZ B cells in the spleen. This could be due to B cell-intrinsic differences in selection into the MZ versus follicular B cell subsets. Alternatively, it could be due to changes in the normal balance and communications between MZ macrophages and MZ B cells. Studies of isolated cell populations and of conditional knockout mice, currently not available, would be required to resolve these issues.

Our present studies demonstrated that spleens of IRF8-deficient mice exhibited multiple abnormalities that were evident in the red pulp, white pulp, and MZ. The red pulp, as noted previously, had expanded populations of myeloid cells including macrophages and, more prominently, granulocytes. The number and size of the white pulp follicles were reduced, GCs were fewer in number and altered in structure and the population of MZ B cells was expanded. In addition, the number and organization of MZ macrophages was disturbed. The mechanisms responsible for these abnormalities are yet to be clearly defined although they are most likely to reflect cell type-specific functions of IRF8.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance of B. Marshall, photographic support from Rick Dreyfuss, and the provision of mice by K. Ozato. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12026-008-8032-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Cozine CL, Wolniak KL, Waldschmidt TJ. The primary germinal center response in mice. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:323–35. doi: 10.1038/nri799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mebius RE, Nolte MA, Kraal G. Development and function of the splenic marginal zone. Crit Rev Immunol. 2004;24:449–64. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v24.i6.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwickert TA, Lindquist RL, Shakhar G, Livshits G, Skokos D, Kosco-Vilbois MH, et al. In vivo imaging of germinal centres reveals a dynamic open structure. Nature. 2007;446:83–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen CD, Okada T, Tang HL, Cyster JG. Imaging of germinal center selection events during affinity maturation. Science. 2007;315:528–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1136736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tew JG, Wu J, Fakher M, Szakal AK, Qin D. Follicular dendritic cells: beyond the necessity of T-cell help. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:361–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01942-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto M, Fu YX, Molina H, Huang G, Kim J, Thomas DA, et al. Distinct roles of lymphotoxin alpha and the type I tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor in the establishment of follicular dendritic cells from non-bone marrow-derived cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1997–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Victoratos P, Lagnel J, Tzima S, Alimzhanov MB, Rajewsky K, Pasparakis M, et al. FDC-specific functions of p55TNFR and IKK2 in the development of FDC networks and of antibody responses. Immunity. 2006;24:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtschke T, Lohler J, Kanno Y, Fehr T, Giese N, Rosenbauer F, et al. Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell. 1996;87:307–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turcotte K, Gauthier S, Tuite A, Mullick A, Malo D, Gros P. A mutation in the Icsbp1 gene causes susceptibility to infection and a chronic myeloid leukemia-like syndrome in BXH-2 mice. J Exp Med. 2005;201:881–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong HJ, Anderson DE, Lee CH, Jang MK, Tamura T, Tailor P, et al. Cutting edge: autoantigen Ro52 is an interferon inducible E3 ligase that ubiquitinates IRF-8 and enhances cytokine expression in macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179:26–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanno Y, Levi BZ, Tamura T, Ozato K. Immune cell-specific amplification of interferon signaling by the IRF-4/8-PU 1 complex. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:770–9. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriele L, Ozato K. The role of the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family in dendritic cell development and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18:503–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Borghi P, Sestili P, Venditti M, Morse HC, III, et al. ICSBP is critically involved in the normal development and trafficking of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;103:2221–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aliberti J, Schulz O, Pennington DJ, Tsujimura H, Reis e Sousa C, Ozato K, et al. Essential role for ICSBP in the in vivo development of murine CD8alpha + dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;101:305–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsujimura H, Tamura T, Ozato K. Cutting edge: IFN consensus sequence binding protein/IFN regulatory factor 8 drives the development of type I IFN-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:1131–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamura T, Tailor P, Yamaoka K, Kong HJ, Tsujimura H, O’Shea JJ, et al. IFN regulatory factor-4 and -8 govern dendritic cell subset development and their functional diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:2573–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu R, Medina KL, Lancki DW, Singh H. IRF-4, 8 orchestrate the pre-B-to-B transition in lymphocyte development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1703–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1104803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma S, Turetsky A, Trinh L, Lu R. IFN regulatory factor 4 and 8 promote Ig light chain kappa locus activation in pre-B cell development. J Immunol. 2006;177:7898–904. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CH, Melchers M, Wang H, Torrey TA, Slota R, Qi CF, et al. Regulation of the germinal center gene program by interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 8/IFN consensus sequence-binding protein. J Exp Med. 2006;203:63–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Nierop K, de Groot C. Human follicular dendritic cells: function, origin and development. Semin Immunol. 2002;14:251–7. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintanilla-Martinez L, Thieblemont C, Fend F, Kumar S, Pinyol M, Campo E, et al. Mantle cell lymphomas lack expression of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:175–82. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65558-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez A, Pittaluga S, Rudelius M, Davies-Hill T, Sebasigari D, Fountaine TJ, et al. Expression of the interferon regulatory factor IRF8/ICSBP1 in human reactive lymphoid tissues and B-cell lymphomas: a novel germinal center marker. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008 doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318166f46a. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cattoretti G, Shaknovich R, Smith PM, Jack HM, Murty VV, Alobeid B. Stages of germinal center transit are defined by B cell transcription factor coexpression and relative abundance. J Immunol. 2006;177:6930–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YJ, Joshua DE, Williams GT, Smith CA, Gordon J, MacLennan IC. Mechanism of antigen-driven selection in germinal centres. Nature. 1989;342:929–31. doi: 10.1038/342929a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koopman G, Parmentier HK, Schuurman HJ, Newman W, Meijer CJ, Pals ST. Adhesion of human B cells to follicular dendritic cells involves both the lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1/intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and very late antigen 4/vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 pathways. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1297–304. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koopman G, Keehnen RM, Lindhout E, Newman W, Shimizu Y, van Seventer GA, et al. Adhesion through the LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18)-ICAM-1 (CD54) and the VLA-4 (CD49d)-VCAM-1 (CD106) pathways prevents apoptosis of germinal center B cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:3760–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu J, Qin D, Burton GF, Szakal AK, Tew JG. Follicular dendritic cell-derived antigen and accessory activity in initiation of memory IgG responses in vitro. J Immunol. 1996;157:3404–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlsson MC, Guinamard R, Bolland S, Sankala M, Steinman RM, Ravetch JV. Macrophages control the retention and trafficking of B lymphocytes in the splenic marginal zone. J Exp Med. 2003;198:333–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nolte MA, Arens R, Kraus M, van Oers MH, Kraal G, van Lier RA, et al. B cells are crucial for both development and maintenance of the splenic marginal zone. J Immunol. 2004;172:3620–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balogh P, Aydar Y, Tew JG, Szakal AK. Appearance and phenotype of murine follicular dendritic cells expressing VCAM-1. Anat Rec. 2002;268:160–8. doi: 10.1002/ar.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W, Nagineni CN, Efiok B, Chepelinsky AB, Egwuagu CE. Interferon regulatory transcription factors are constitutively expressed and spatially regulated in the mouse lens. Dev Biol. 1999;210:44–55. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, Nagineni CN, Ge H, Efiok B, Chepelinsky AB, Egwuagu CE. Interferon consensus sequence-binding protein is constitutively expressed and differentially regulated in the ocular lens. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9686–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray PA, Fu H, Luo P, Zhao Q, Yu J, Ferrari A, et al. Mouse brain organization revealed through direct genome-scale TF expression analysis. Science. 2004;306:2255–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1104935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, Nagineni CN, Hooks JJ, Chepelinsky AB, Egwuagu CE. Interferon-gamma signaling in human retinal pigment epithelial cells mediated by STAT1, ICSBP, and IRF-1 transcription factors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:976–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dadoune JP, Pawlak A, Alfonsi MF, Siffroi JP. Identification of transcripts by macroarrays, RT-PCR and in situ hybridization in human ejaculate spermatozoa. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:133–40. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen W, Rogatsky I, Garabedian MJ. MED14 and MED1 differentially regulate target-specific gene activation by the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:560–72. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu K, Abrams SI. Coordinate regulation of IFN consensus sequence-binding protein and caspase-1 in the sensitization of human colon carcinoma cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis by IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2003;170:6329–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang D, Thangaraju M, Greeneltch K, Browning DD, Schoenlein PV, Tamura T, et al. Repression of IFN regulatory factor 8 by DNA methylation is a molecular determinant of apoptotic resistance and metastatic phenotype in metastatic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3301–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamura T, Nagamura-Inoue T, Shmeltzer Z, Kuwata T, Ozato K. ICSBP directs bipotential myeloid progenitor cells to differentiate into mature macrophages. Immunity. 2000;13:155–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ato M, Nakano H, Kakiuchi T, Kaye PM. Localization of marginal zone macrophages is regulated by C-C chemokine ligands 21/19. J Immunol. 2004;173:4815–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.