Abstract

Photochemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization (photo-CIDNP) of nuclei other than 1H offers a tremendous potential for sensitivity enhancement in liquid state NMR under mild, physiologically relevant conditions. Photo-CIDNP enhancements of 15N magnetization are much larger than those typically observed for 1H. However, the low gyromagnetic ratio of 15N prevents a full fruition of the potential signal-to-noise gains attainable via 15N photo-CIDNP. Here, we propose two novel pulse sequences, EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC, tailored to overcome the above limitation. EPIC-HSQC exploits the strong 1H polarization and its subsequent transfer to non-equilibrium Nz magnetization prior to 15N photo-CIDNP laser irradiation. CHANCE-HSQC synergistically combines 1H and 15N photo-CIDNP. The above pulse sequences, tested on tryptophan (Trp) and the Trp-containing protein apoHmpH, were found to display up to two-fold higher sensitivity than the reference NPE-SE-HSQC pulse train (based on simple 15N photo-CIDNP followed by N-H polarization transfer), and up to a ca. 3-fold increase in sensitivity over the corresponding dark pulse schemes (lacking laser irradiation). The observed effects are consistent with the predictions from a theoretical model of photo-CIDNP and prove the potential of 15N and 1H photo-CIDNP in liquid state heteronuclear correlation NMR.

Introduction

For selected nuclei, a considerable degree of nonequilibrium polarization can be photochemically induced in liquid media containing a dye prone to populate a triplet excited state, via a process known as photo-CIDNP. Interaction of the photo-excited triplet dye with specific NMR-active target molecules ultimately results in variations in NMR resonance intensities [1-3]. Given that a reactive collision between the NMR-active substrate and the photosensitizer dye is usually needed [4-6], photo-CIDNP has been primarily employed to monitor the degree of solvent exposure of tryptophan and other selected amino acids in polypeptides and proteins [7-10].

According to the most widely accepted photo-CIDNP mechanism [4], interaction between the dye (usually flavin mononucleotide (FMN) or another flavin derivative) and the NMR-active substrate, followed by reversible oxidation of the substrate by the dye, results in the transient formation of a triplet radical pair. The fate of the radical pair is governed by two competing reaction pathways known as recombination and escape. The relative flux along the recombination and escape paths depends on the spin state of the polarizable nuclei, for photo-CIDNP-active residues. The above processes give rise to absorptive or emissive resonances with either enhanced or reduced intensities [4,11].

Typical photo-CIDNP applications rely on the enhancement of 1H longitudinal magnetization in 1H-detected 90°-pulse-acquisition experiments [2,9,12,13]. On the other hand, despite the widespread use of heteronuclear correlation in NMR [14], applications of photo-CIDNP to heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy have been scarce to date [15-17].

Among the photo-CIDNP-active amino acids, tryptophan (Trp) is the only one that contains a slow-exchanging side chain proton linked to 15N (i.e., Hε1 in the indole aromatic ring). Therefore Trp is a suitable model for photo-CIDNP method development studies involving 1H-15N heteronuclear correlation NMR. Photo-CIDNP enhancements are much larger for 15N than 1H because the unpaired electron spin density at the indole 15Nε1 nucleus is higher than at the 1Hε1 [18]. On the other hand, the overall sensitivity of pulse sequences employing 15N-photo-CIDNP is hampered by the intrinsically NMR low sensitivity of 15N. The only 15N photo-CIDNP-enhanced (NPE-) pulse sequence reported so far comprises a pre-rf laser irradiation followed by 15N rf excitation and reverse INEPT-type transfer back to 1H [15,16]. Such sequence is referred to here as NPE-SE-HSQC (Fig. 1c).

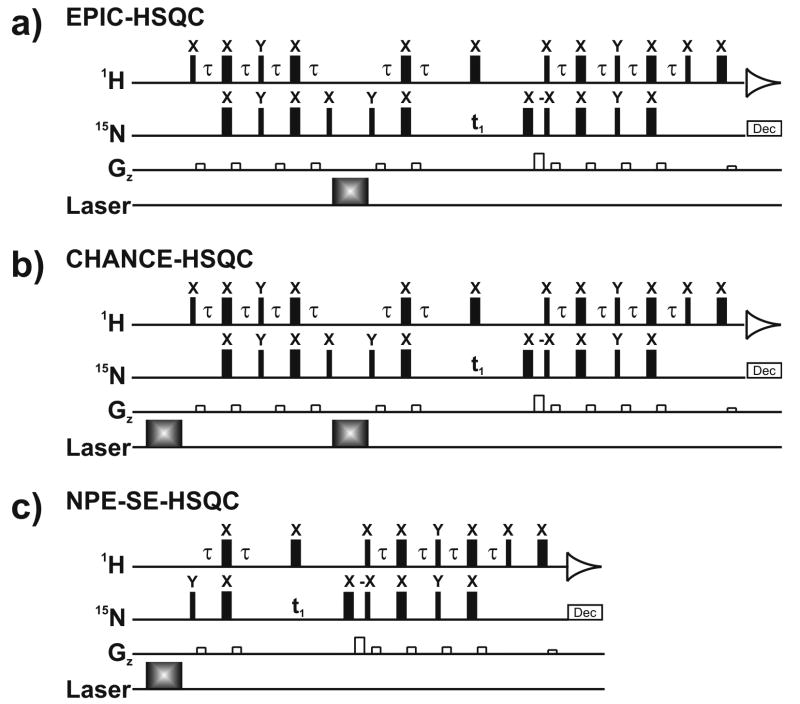

Fig. 1.

(a) EPIC-HSQC and (b) CHANCE-HSQC pulse sequences, and (c) the reference sequence NPE-SE-HSQC [15,16]. The EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC rf pulses preceding the 15N chemical shift evolution delay are not phase cycled. The phase of the NPE-SE-HSQC 15N 90° excitation pulse is cycled between y and −y. The phase cycling of all the rf pulses following the 15N chemical shift evolution delay is identical to that of sensitivity-enhanced HSQC [14].

In this report, we propose two novel pulse sequences that employ 15N photo-CIDNP and, at the same time, overcome the low intrinsic sensitivity of 15N. We find that, even at the moderate laser power employed here (1 W), both sequences exhibit up to 2-fold higher signal-to-noise per unit time (S/N)t than NPE-SE-HSQC for the indole Hε1 of free Trp, and 25-35 % higher sensitivity for urea-unfolded apoHmpH, a Trp-containing protein. The new sequences yield up to a ca. 3-fold increase in sensitivity over the corresponding dark (i.e., lacking laser irradiation) pulse schemes, highlighting the power of photo-CIDNP for sensitivity enhancement in NMR.

Results and Discussion

General features of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC

15N photo-CIDNP enhancements, defined as (S/N)t,light/ (S/N)t,dark, are 1-2 orders of magnitude larger than 1H enhancements, for the biologically relevant indole NH spin pair of tryptophan [15]. A large 15N photo-CIDNP is expected due to the high unpaired spin electron density on the indole 15N, in the Trp radical cation that gets populated in the course of photo-CIDNP [18]. 15N photo-CIDNP was recently exploited to study native and non-native states of lysozyme [15,16] via a pulse sequence based on 15N excitation and a 15N-1H reverse-INEPT transfer, similar to the NPE-SE-HSQC pulse scheme shown in Figure 1c. However, despite the large observed enhancements, the absolute sensitivity of photo-CIDNP 15N-1H sequences is limited by the low inherent sensitivity of 15N.

In this report, we propose two sensitive photo-CIDNP-enhanced pulse sequences, EPIC-HSQC (i.e., Enhancement by Polarization transfer Integrated with 15N photo-CIDNP-HSQC, Fig. 1a) and CHANCE-HSQC (i.e., Combined 1H and 15N photo-CIDNP-Enhanced-HSQC, Fig. 1b), which successfully overcome the above limitation.

Photo-CIDNP acts on spin populations and has the ability to enhance longitudinal magnetization. Thus, the goal of the first portion of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC is to generate augmented non-equilibrium longitudinal 15N magnetization prior to the 15N photo-CIDNP step.

Accordingly, EPIC-HSQC (Fig. 1a) combines the superior 1H sensitivity and the large 15N photo-CIDNP by transferring the large 1H polarization to 15N via INEPT. The resulting 2HzNx antiphase 15N coherence is then turned into 15N z-magnetization immediately prior to laser irradiation via the refocusing steps

| (1) |

15N-photo-CIDNP is then carried out on a polarization transfer-enhanced 15N magnetization, which is ∼10-fold larger than its equilibrium value. After laser irradiation, 15N-photo-CIDNP-enhanced magnetization is detected following coherence transfer back to the 1H nucleus. EPIC-HSQC thus combines the advantageous features of 1H and 15N to achieve higher NMR sensitivity.

As shown in Figure 1b, CHANCE-HSQC combines photo-CIDNP enhancements from both 1H and 15N to probe the opportunity to further increase sensitivity. An initial laser pulse generates photo-CIDNP-enhanced 1H polarization, which is then transferred to 15N through a refocused-INEPT pulse train. A second laser pulse generates 15N photo-CIDNP, which further adds to the previous 1H photo-CIDNP. The combination of the above effects is detected on the 1H channel following a reverse-INEPT transfer.

Both EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC involve excitation and detection of the sensitive 1H nucleus, thereby maintaining the γ5/2 sensitivity advantage. Laser irradiation applied to non-equilibrium polarization generated within the rf pulse sequence, as opposed to the conventional irradiation before the first rf pulse [4], is another notable feature of both of these steady-state photo-CIDNP pulse schemes.

In EPIC-HSQC, photo-CIDNP arises solely from 15N. In the case of CHANCE-HSQC, on the other hand, 1H and 15N-photo-CIDNP are combined and may be toggled on/off at will. For instance, both laser pulses may be turned off, giving rise to a completely dark spectrum, or either the first or second laser pulses may be turned on giving rise to 1H or 15N photo-CIDNP alone. Alternatively, both laser pulses may be on, giving rise to the full light spectrum taking advantage of both 1H and 15N photo-CIDNP. Clearly, CHANCE-HSQC with only the second laser pulse turned on is indistinguishable from EPIC-HSQC.

The NMR resonance intensity attainable by the proposed pulse sequences under light conditions depends critically on the sign of the 15N polarization immediately preceding the relevant laser pulse (i.e., the EPIC-HSQC only laser pulse, and the CHANCE-HSQC laser pulse II). This concept is further discussed and corroborated by experimental evidence in the Supplementary Information. As shown in supplementary Figures S1 and S2, when the longitudinal 15N magnetization preceding the relevant laser pulse is driven to be positive, the resulting spectral intensity under light conditions is significantly smaller. As a consequence, a full fruition of the photo-CIDNP sensitivity enhancement is only achieved if the longitudinal 15N magnetization preceding the relevant laser irradiation is set to a proper sign, in this case negative. This goal was achieved by setting the second 15N 90° rf pulse to be +x, in both EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC. It is worth noticing that, in case the sign of the isotropic hyperfine coupling constant for the polarizable nucleus of interest were to be opposite, the pulse phases listed in Figure 1 would lead to decreased signal intensities. The above discussion underscores the importance of properly preparing the sign of the relevant longitudinal magnetization prior to any laser irradiation, in heteronuclear photo-CIDNP NMR.

EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC applications to biologically relevant samples

The performance of EPIC- and the CHANCE-HSQC was tested on two model substrates: 15N-Trp (in water and 6 M urea) and 15N-apoHmpH, a Trp-containing protein (in a 6 M urea aqueous buffer). ApoHmpH [19] is the 15.7 kDa heme-binding domain of the E.coli globin flavohemoglobin [20]. It has one Trp (W120, in the H-helix) that is solvent-exposed in the urea-unfolded state but sequestered within the hydrophobic core in the native state. Urea-unfolded apoHmpH is thus an appropriate substrate for photo-CIDNP applications.

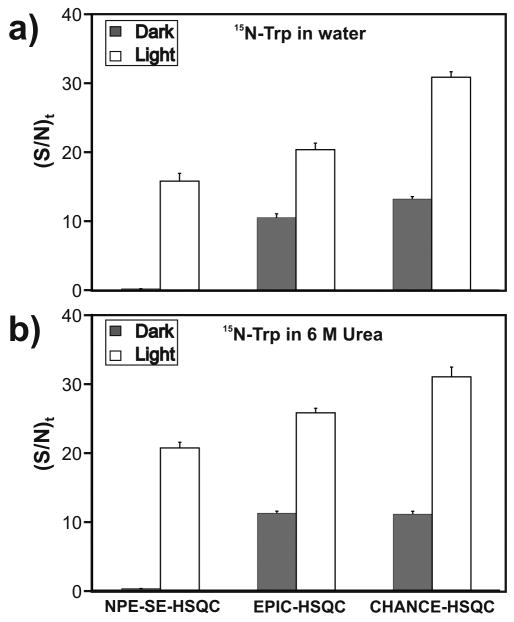

The sensitivity of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC was assessed experimentally by evaluating (S/N)t, defined as in eqn. 10, under light conditions. Figures 2 and 3 compare the sensitivity of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC and the reference sequence NPE-SE-HSQC, for the free Trp and apoHmpH samples.

Fig. 2.

Comparison between the sensitivity (i.e., (S/N)t) of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC and that of the reference NPE-SE-HSQC sequence for (a) 15N-Trp in water and (b) 15N-Trp in 6 M urea at pH 6.9 and 24°C. The Trp concentration was 1 mM in all samples. Data were collected in 1D mode (4 transients and two steady state scans) upon setting the 15N chemical shift evolution delay to zero. Uncertainties in (S/N)t are expressed as ± 1 standard error of the mean. Measurements were made on 2 independent samples and 10 replicates were carried out for each sample.

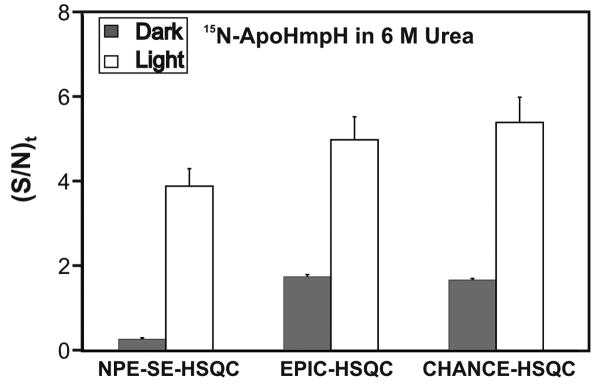

Fig. 3.

Comparison between the (S/N)t of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC and the NPE-SE-HSQC reference pulse sequence for the Trp120 indole 1H resonance of urea-unfolded 15N-apoHmpH (∼ 300 μM in 25 mM tris-d11, in aqueous 6 M urea and 0.2 mM flavin mononucleotide (FMN), at pH 7.0). (S/N)t values were determined from data acquired at 24°C in 1D mode (16 transients and two steady state scans) by setting the evolution time of the indirect dimension to zero. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error of the mean. Measurements were performed on two independent samples. The vertical scale is not directly comparable to that of Figure 2 due to the different number of transients and sample concentrations.

In all cases, the new pulse sequences show an increased (S/N)t over NPE-SE-HSQC. For Trp in water, EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC are 25% and 94% more sensitive than NPE-SE-HSQC, respectively. Sensitivity enhancements over NPE-SE-HSQC for Trp in 6 M urea range from 24% for EPIC-HSQC to 48% for CHANCE-HSQC. The apoHmpH protein shows (S/N)t increases of 25% (EPIC-HSQC) and 35% (CHANCE-HSQC) relative to NPE-SE-HSQC.

Furthermore, under light conditions, EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC are 1.9 - 2.8-fold more sensitive than the corresponding dark sequences for free Trp, and 2.9 - 3.2-fold more sensitive for apoHmpH. These significant sensitivity enhancements are larger than those observed for 1H photo-CIDNP heteronuclear correlation pulse sequences [17]. The above results demonstrate the advantages of 15N photo-CIDNP in heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy.

At the low laser power employed here, the optimal length of the EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC laser irradiation delay following creation of non-equilibrium Nz magnetization was found to be 500 ms. During this fairly long time span, significant 15N spin-lattice relaxation can take place. In addition, the 500 ms laser irradiation period increases the overall length of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC, thereby decreasing (S/N)t. Within this context, higher laser irradiation power is a promising tool to yield further increases in (S/N)t, since higher power warrants the use of significantly shorter laser irradiation.

Computational prediction of photo-CIDNP sensitivity enhancements

The experimentally observed photo-CIDNP sensitivity enhancements observed in EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC can be rationalized by the following photo-CIDNP theoretical framework [21].

The evolution of 1H and 15N magnetization of the Trp indole NH during photo-CIDNP can be described by a theoretical framework modeling photo-CIDNP pumping as a zeroth order process [21,22] taking place at rates pH and pN, for 1H and 15N, respectively, according to

| (2) |

where ρH, ρN and ρNH are autorelaxation rate constants for Hz, Nz and the two spin-order 2HzNz, respectively; Hz0, Nz0 are the equilibrium proton and nitrogen polarizations, σNH is the 1H–15N cross-relaxation rate constant, and ηz is a rate constant arising from the interference between 15N chemical shift anisotropy and 1H–15N dipolar relaxation. According to the above model, photo-CIDNP pumping is regarded as an additive perturbation to the well-known equations of motion in the absence of photo-CIDNP [23].

The above relaxation rate constants are related to the spectral density function (J(ω)) at frequencies ωH, ωN, ωH−ωN and ωH+ωN by [14]:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

where c = γNB0 (σ‖ − σ⊥) and . In the above relations, γH and γN are the 1H and 15N gyromagnetic ratios, ωH and ωN are the 1H and 15N Larmor frequencies, respectively, rNH is the indole 1H−15N bond distance in Trp (rNH = 1.02 Å´ [24]); μ0 is the permittivity of free space, σ‖ and σ⊥ are the parallel and perpendicular components of the axially symmetric chemical shielding tensor, with (σ‖ − σ⊥) assumed to be -89.2 ppm for the Trp indole 15Nε1 [25]. The spectral density functions at frequencies ωH, ωN, ωH−ωN and ωH+ωN can be evaluated from the general form of J(ω) for an isotropically tumbling molecule in the absence of local motions

| (8) |

The rotational correlation time τc for Trp is 50 ps [21]. τc for Trp in 6 M urea can be calculated from τc for Trp in water taking into account the 1.36-fold larger viscosity of 6 M urea relative to water [26]. The estimated relaxation rate constants for Trp in water and in 6 M urea are shown in Table 1. pH and pN are determined from experimental data collected with the HPE-SE-HSQC [17] and NPE-SE-HSQC [15-17] reference pulse sequences (see Materials and Methods).

Table 1.

NMR relaxation rate constants used to compute (S/N)t in the presence of photo-CIDNP.

| NMR relaxation rate constants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | ρH (s-1) |

ρN (s-1) |

ρNH (s-1) |

σNH (s-1) |

δ (s-1) |

| Trp in water | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| Trp in 6 M urea | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

The pH and pN parameters are then entered into the system of coupled differential equations describing the time-dependent behavior of Hz, Nz and HzNz in the presence of photo-CIDNP (relations 2). Numerical integration using (S/N)t of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC under dark conditions as experimental inputs yields predicted values for (S/N)t in the presence of photo-CIDNP, as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Computationally predicted and experimentally observed (S/N)t for EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC are listed in Table 2 and further discussed below.

Table 2.

Comparison between experimental and computationally predicted (S/N)t for EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC under light conditions.

| NMR Pulse Sequence | Samples | |

|---|---|---|

| Trp in water | Trp in 6 M urea | |

| EPIC-HSQC | ||

| Computed | 23.3 | 28.0 |

| Experimental | 20 ± 1 | 25.7 ± 0.7 |

| CHANCE-HSQC | ||

| Computed | 28.8 | 37.4 |

| Experimental | 30.9 ± 0.8 | 31 ± 1 |

Comparison between experimental and computationally predicted (S/N)t

As shown in Table 2, the experimental and computationally predicted enhancements are in very good agreement for samples of Trp in water and in 6 M urea, supporting the reliability of the above theoretical treatment for EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC. The (S/N)t is higher for Trp samples in urea, as discussed below.

Computational predictions for urea-unfolded apoHmpH would involve several approximations and assumptions. Most importantly, the global tumbling of unfolded proteins is typically highly anisotropic and cannot be described by a unique rotational correlation time nor by a spectra density function of the form of eqn. 8. Furthermore, the model-free approach [27] is unsuitable, and other strategies used to describe unfolded proteins [28-31] cannot be applied here due to the lack of input data. Hence, it is not possible to reliably estimate ρ, σ and ηz in the case of unfolded proteins. Therefore, we chose not to report comparisons between experimental and computed photo-CIDNP enhancements of urea-unfolded apoHmpH.

Effect of viscosity

The viscosity of 6 M urea is 1.36-fold higher than water [26]. The higher viscosity results in a slower rotational correlation time (τc) of Trp, leading to increased NMR relaxation rate constants ρ, σ and ηz. In addition, the decrease in translational diffusion coefficient of Trp and FMN, also caused by higher viscosity, modifies the re-encounter probabilities of the Trp radical-ion pair intermediate [32]. As a consequence, photo-CIDNP pumping rates pH and pN increase. The combined effect of urea on relaxation rate constants and photo-CIDNP pumping rates is reflected in the higher photo-CIDNP enhancements observed for both EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC in the presence of urea.

Comparison between the performance of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC

Both EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC are more sensitive than NPE-SE-HSQC under light conditions. CHANCE-HSQC is a more sensitive sequence than EPIC-HSQC in that it exhibits a higher (S/N)t, by a factor of 1.4 in the case of apoHmpH. However, CHANCE-HSQC requires one more laser pulse/scan than EPIC-HSQC. Therefore, the number of laser pulses available for signal averaging before any significant photodegradation occurs is higher by a factor of two, in EPIC-HSQC.

Therefore, CHANCE-HSQC is a more suitable sequence for real-time photo-CIDNP applications that require rapid data collection (e.g., protein folding kinetics studies) and a high sensitivity per scan. On the other hand, for samples at equilibrium, EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC are of comparable value, as they provides a similar (S/N)t per laser pulse.

2D applications of EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC

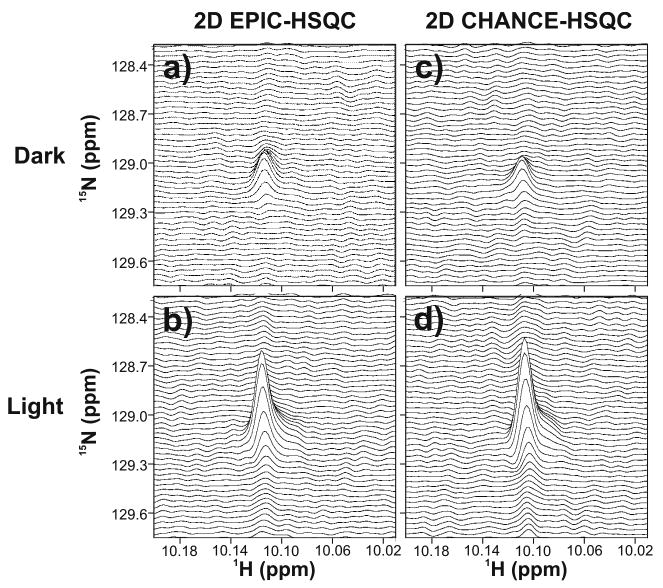

We collected 2D light and dark EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC data on urea-unfolded 15N-apoHmpH at a moderate protein concentration. Stacked plots of these 2D spectra are shown in Figure 4. Light spectra acquired with both pulse sequences show negligible t1 noise, demonstrating the stability of the laser light intensity over time and the reproducibility of shutter timing. The latter is of particular importance in this work, because both EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC include laser irradiation within the rf sequence.

Fig. 4.

Stacked plots of (a and b) 2D EPIC-HSQC and (c and d) 2D CHANCE-HSQC for urea-unfolded 15N-apoHmpH (∼ 300 μM in 25 mM tris-d11, 6 M urea and 0.2 mM FMN, at pH 7.0). Data were collected at 24°C. Panels a and c show the dark spectra, and panels b and d show the light spectra. Each 2D dataset included 32 t1 increments with one transient per increment

Long-term irradiation of samples containing Trp and FMN results in some irreversible photobleaching of FMN and photodegradation of Trp [33]. We have previously investigated the impact of photo-CIDNP 1 W laser irradiation at 488 nm on photodegradation and photobleaching. The effect of these irreversible processes was found to be negligible (i.e., ≤ 5 %) up to 200 500 ms laser pulses [17]. Therefore, given that the laser power and irradiation time employed here are identical to those of the above study, 2D EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC data collection (as well as 1D data acquisition up to ca. 200 transients) is feasible and it does not result into any significant chemical perturbations of the NMR sample.

In summary, acquisition of high quality 2D EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC data of Trp-containing proteins in the presence of photo-CIDNP is straightforward and feasible.

Conclusions

This report proposes two strategies to increase the sensitivity of photo-CIDNP heteronuclear correlation NMR. The EPIC-HSQC pulse sequence integrates the high NMR sensitivity of the 1H nucleus with the large 15N photo-CIDNP enhancement. CHANCE-HSQC combines 1H and 15N photo-CIDNP to achieve an even better (S/N)t. EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC give rise to 25 to 95% higher (S/N)t in photo-CIDNP light spectra for free Trp and 25-35% higher (S/N)t for apoHmpH compared to the conventional NPE-SE-HSQC pulse sequence. EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC are amenable to 2D data acquisition and yield sensitivity enhancements consistent with the predictions of a photo-CIDNP theoretical model. The above class of pulse sequences is also posed to be extended to heteronuclear correlation experiments involving other polarizable insensitive nuclei, e.g., 13C. This type of application promises to be particularly advantageous for nuclei with significant hyperfine coupling. Finally, the use of higher laser irradiation power promises to be a straightforward approach to achieve even greater sensitivity enhancements.

Materials and Methods

NMR sample preparation

Concentrated stock solutions of aqueous 15N-tryptophan (Trp; Isotec Inc., Miamisburg, OH) and riboflavin-5′-monophosphate (FMN; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were prepared. The pH of the Trp stock solution was adjusted to 7.0. Trp and FMN concentrations were assessed by UV-visible absorption spectroscopy (ε278,Trp = 5,578 M-1cm-1[34], ε450,FMN = 12,500 M-1cm-1[35]). Trp NMR samples (1 mM Trp and 0.2 mM FMN) were prepared by diluting aliquots of Trp and FMN stock solutions in water. Solid urea (6 M, ultrapure, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) was added directly to the NMR samples if needed, and the pH was adjusted to 6.9.

15N-apoHmpH was overexpressed and purified as described [19]. Unfolded apoHmpH NMR samples were prepared by dissolving lyophilized pure apoHmpH in 25 mM tris-d11 (Isotec Inc., Miamisburg, OH) pH 7.0 containing 6 M urea. An appropriate volume of FMN stock solution was added (final concentration: 0.2 mM) and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 0.1 M HCl. ApoHmpH concentrations (typically ∼ 300 μM) were determined by absorption spectroscopy (ε280,apoHmpH = 14,500 M-1cm-1[19]). Control experiments (data not shown) revealed that the presence of 25 mM tris-d11 in NMR samples does not adversely affect photo-CIDNP enhancements, in agreement with earlier reports [36].

All NMR samples contained 5% D2O. Samples containing high concentrations of urea were used within ca. 24 hours of sample preparation.

Photo-CIDNP instrumentation

Photo-CIDNP was generated via photo-irradiation with an Omnichrome 1 W Ar-ion laser (model 543-MAP, Chino, CA) operating in multiline mode (main lines: 488 and 514 nm). Monochromatic laser light (488 nm) was directed into a quartz optical fiber (10 m length, 1 mm diameter, F-MBE, Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA, polished at both ends) via appropriate mirrors (Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA) and a fiber-coupler (F-91-C1-T, Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA). The free end of the optical fiber was routed into a glass NMR tube coaxial insert (Wilmad Labglass, Buena, NJ) and introduced into a 5 mm NMR tube. The position of the coaxial insert was adjusted so that the tip of the fiber was 4 mm above the top of the receiver coil region in the high field magnet. Experiments with apoHmpH were done in Shigemi tubes. The optical fiber was placed inside the insert of a 5 mm Shigemi tube (Shigemi, Inc., Allison Park, PA), with the fiber barely touching the bottom of the insert. A high-speed mechanical shutter-controller setup (shutter: LS055, controller: CX2250, NMLaser, San Jose, CA) was interfaced with the spectrometer console pulse programmer to appropriately coordinate the gating of laser radiation and rf pulses.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR data were collected at 24°C on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a Varian triple resonance 1H{13C, 15N} triple axis gradient probe. The EPIC-HSQC and CHANCE-HSQC pulse sequences (Fig. 1) include 500 ms laser irradiation modules followed by a 500 μs delay to allow the decay of transient paramagnetic species. The dark versions of both sequences are identical to the corresponding light sequences (including the presence of the 500 ms and 500 μs time intervals), except for the fact that laser light is gated off. Data in 1D mode were collected by setting the 15N chemical shift evolution time for the indirect dimension to zero.

Photo-CIDNP experiments under dark and light conditions were carried out with 1,800 complex data points spread over a spectral window of 9,000 Hz. Data for Trp and Trp in 6 M urea were collected with 4 transients preceded by 2 dummy scans, while apoHmpH light and dark data included 16 transients preceded by 2 dummy scans. A uniform relaxation delay of 1.5 s was employed in all experiments.

Data collected under dark and light conditions were processed identically with the VNMR 6.1c software (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Free induction decays were apodized with a 1 Hz exponential linebroadening function and zero-filled to 128k total data points to optimize digitization. Spectra were baseline-corrected with a spline function using the VNMR6.1c baseline fitting utility.

Evaluation of signal-to-noise

S/N of the Trp indole 1H resonance in 1D 1H–15N correlation spectra was determined from independent measurements of resonance intensity (S) and peak-to-peak noise amplitude (NPTP) evaluated within a 4 ppm spectral region centered on the Trp Hε1 resonance. Signal-to-noise (S/N) and signal-to-noise per unit time ((S/N)t) [37] were determined from relations 9 and 10, respectively

| (9) |

| (10) |

where t is the total data collection time.

For each Trp sample (in water or in 6 M urea), 10 replicate experiments (under light and dark conditions) were performed. Measurements on two independent samples were averaged and errors were propagated according to standard procedures [38]. Errors in (S/N)t were obtained by propagation of the uncertainties in S/N. Standard errors were obtained by dividing the standard deviations by , where n is the number of independent measurements (i.e., 2, see above) [39].

2D NMR data acquisition and processing

2D EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC data were collected on a 15N-apoHmpH sample (∼ 300 μM) in aqueous 25 mM tris-d11 (pH 7.0) containing 6 M urea. Data were collected with sweep widths of 9,000 and 250 Hz, in the 1H and 15N dimensions, respectively. Each dataset comprised 2,048 complex points and 32 increments, with 1 scan per increment. Quadrature detection in the indirect dimension was achieved according to States et al. [40].All data sets were processed identically with the VNMR 6.1c software. Time-domain data were apodized with a cosine-square function and zero-filled to 16,384 and 256 total points in the 1H and 15N dimensions, respectively, prior to Fourier transformation.

Computational prediction of photo-CIDNP enhancements

The system of three coupled first order differential equations 2 was integrated numerically with the Matlab 7.0 software package (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The pH and pN values were determined by employing HPE-SE-HSQC [14] and NPE-SE-HSQC as sample-specific reference pulse sequences as follows. The experimental (S/N)t of HPE-SE-HSQC under dark conditions was used as a measure of Hz0, and the experimental (S/N)t of HPE-SE-HSQC [17] and NPE-SE-HSQC [15-17] under light conditions were taken as a measure of Hz(t=0.5s) and Nz(t=0.5s), respectively. Nz0 was calculated from Hz0, scaled by .

Hz0 and Nz0 values defined as above, together with the NMR relaxation constants in Table 1 and initial guesses for pH and pN, were used to compute Hz(t=0.5s) and Nz(t=0.5s) by numerically integrating relations 2 upon setting t=0.5s. The pH and pN values were then iteratively optimized until the (S/N)t determined from the above numerical integration procedure reproduced the experimentally observed (S/N)t under light conditions. The resulting final values of pH and pN were then used to predict photo-CIDNP enhancements for EPIC- and CHANCE-HSQC as follows.

The EPIC-HSQC pulse sequence has only one laser irradiation period. At the beginning of this period (corresponding to t = 0 in the numerical integration procedure), all Hz magnetization has been converted to Nz magnetization (ignoring relaxation losses during the INEPT-transfer and refocusing periods). Thus, the EPIC-HSQC experimental (S/N)t under dark conditions is a measure of Nz0. In addition, Hz0 = 0. The value of Nz(t=0.5s), was computed from Hz0 and Nz0 and pH and pN, determined as described above, and from the NMR relaxation constants in Table 1 by numerical integration of relations 2 upon setting t = 0.5 s. Since Nz(t=0.5s) is completely converted to 1H coherence at the end of the pulse sequence, Nz(t=0.5s) is used as a measure of (S/N)t under light conditions.

CHANCE-HSQC has two laser irradiation periods, denoted in the subscripts below as I and II. The experimental (S/N)t under dark conditions was used as a measure of Hz0,I, i.e., the 1H longitudinal magnetization at time t = 0 of the first laser irradiation period. Nz0,I was calculated by scaling Hz0,I by . Hz,I(t=0.5s) was then computed by numerical integration of relations 2 upon entering the above Hz0 and Nz0 and setting t = 0.5 s.

In CHANCE-HSQC, Hz,I(t=0.5s) was set equal to Nz0,II, assuming that the photo-CIDNP-enhanced Hz magnetization at the beginning of the rf pulse sequence is quantitatively converted to Nz before the second laser pulse. In addition, we set Hz0,II = 0. Numerical integration of relations 2 was then used to compute Nz,II(t=0.5s). The latter value was taken as a measure of CHANCE-HSQC (S/N)t under light conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ed Turner for lending us equipment and to Jennifer Choi for providing samples of 15N-labeled apoHmpH. We thank Charles Fry for helpful discussions, and Neşe Kurt and Jung Ho Lee for a critical reading of the manuscript. This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant GM068535.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bargon J, Fischer H, Johnsen U. Nuclear magnetic resonance emission lines during fast radical reactions. I. Recording methods and examples. In: Naturforsch ZA, editor. Phys Sci. Vol. 22. 1967. pp. 1551–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaptein R, Dijkstra K, Nicolay K. Laser photo-CIDNP as a surface probe for proteins in solution. Nature. 1978;274:293–294. doi: 10.1038/274293a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward HR, Lawler RG. Nuclear magnetic resonance emission and enhanced absorption in rapid organometallic reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:5518–5519. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hore PJ, Broadhurst RW. Photo-CIDNP of biopolymers. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1993;25:345–402. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaptein R. Chemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization. Theory and applications in mechanistic chemistry. In: Williams GH, editor. Advances in free-radical chemistry. V. Academic Press; New York: 1975. pp. 319–380. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaptein R. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Molecular Biology. In: Pullman B, editor. NMR Spectroscopy in Molecular Biology. D. Reidel Publishing Company; Dordrecht, Holland: 1978. pp. 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canet D, Lyon CE, Scheek RM, Robillard GT, Dobson CM, Hore PJ, van Nuland NAJ. Rapid formation of non-native contacts during the folding of HPr revealed by real-time photo-CIDNP NMR and stopped-flow fluorescence experiments. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:397–407. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hore PJ, Winder SL, Roberts CH, Dobson CM. Stopped-flow photo-CIDNP observation of protein folding. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5049–5050. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok KH, Hore PJ. Photo-CIDNP NMR methods for studying protein folding. Methods. 2004;34:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mok KH, Kuhn LT, Goez M, Day IJ, Lin JC, Andersen NH, Hore PJ. A preexisting hydrophobic collapse in the unfolded state of an ultrafast folding protein. Nature. 2007;447:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature05728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaptein R. Simple rules for chemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization. Journal of the Chemical Society D: Chemical Communications. 1971;1971:732–733. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goez M, Mok KH, Hore PJ. Photo-CIDNP experiments with an optimized presaturation pulse train, gated continuous illumination, and a background-nulling pulse grid. J Magn Reson. 2005;177:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheek RM, Stob S, Boelens R, Dijkstra K, Kaptein R. Applications of two-dimensional 1H nuclear magnetic resonance methods in photochemically induced dynamic nuclear polarisation spectroscopy. Faraday Discuss Chem Soc. 1984;78:245–256. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, Rance M, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR spectroscopy. Second. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyon CE, Jones JA, Redfield C, Dobson CM, Hore PJ. Two-dimensional 15 N–1 H photo-CIDNP as a surface probe of native and partially structured proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6505–6506. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlorb C, Mensch S, Richter C, Schwalbe H. Photo-CIDNP reveals differences in compaction of non-native states of lysozyme. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1802–1803. doi: 10.1021/ja056757d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekhar A, Cavagnero S. 1H photo-CIDNP enhancements in heteronuclear correlation NMR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem. 2009;113:8310–8318. doi: 10.1021/jp901000z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walden SE, Wheeler RA. Distinguishing Features of Indolyl Radical and Radical Cation: Implications for Tryptophan Radical Studies1. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:1530–1535. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eun YJ, Kurt N, Sekhar A, Cavagnero S. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of ApoHmpH, a fast-folding bacterial globin. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:879–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ilari A, Bonamore A, Farina A, Johnson KA, Boffi A. The X-ray structure of ferric Escherichia coli Flavohemoglobin reveals an unexpected geometry of the distal heme pocket. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23725–23732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hore PJ, Egmond MR, Edzes HT, Kaptein R. Cross-relaxation effects in the photo-CIDNP spectra of amino acids and proteins. J Magn Reson. 1982;49:122–142. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuprov I, Hore PJ. Chemically amplified 19F–1H nuclear Overhauser effects. J Magn Reson. 2004;168:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldman M. Interference effects in the relaxation of a pair of unlike spin-1/2 nuclei. J Magn Reson. 1984;60:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tjandra N, Szabo A, Bax A. Protein backbone dynamics and 15N chemical shift anisotropy from quantitative measurement of relaxation interference effects. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6986–6991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross TA, Opella SJ. Protein structure by solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:306–308. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawahara K, Tanford C. Viscosity and density of aqueous solutions of urea and guanidine hydrochloride. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3228–3232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipari G, Szabo A. Effect of librational motion on fluorescence depolarization and nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules and membranes. Biophys J. 1980;30:489–506. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng JW, Wagner G. Mapping of spectral density function using heteronuclear NMR relaxation measurements. J Magn Reson. 1992;98:308–332. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrow NA, Zhang O, Szabo A, Torchia DA, Kay LE. Spectral density function mapping using 15 N relaxation data exclusively. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:153–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00211779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buevich AV, Baum J. Dynamics of unfolded proteins: Incorporation of distributions of correlation times in the model free analysis of NMR relaxation data. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8671–8672. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Modig K, Poulsen FM. Model-independent interpretation of NMR relaxation data for unfolded proteins: the acid-denatured state of ACBP. J Biomol NMR. 2008;42:163–177. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burri J, Fischer H. Diffusion dependence of absolute chemically induced nuclear polarizations from triplet radical pairs in high magnetic fields. Chem Phys. 1989;139:497–502. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Connolly PJ, Hoch JC. Photochemical degradation of tryptophan residues during CIDNP experiments. J Magn Reson. 1991;95:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mihalyi E. Numerical values of the absorbances of the aromatic amino acids in acid, neutral, and alkaline solutions. J Chem Eng Data. 1968;13:179–182. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitby LG. A new method for preparing flavin-adenine dinucleotide. Biochem J. 1953;54:437–442. doi: 10.1042/bj0540437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaptein R. Photo-CIDNP studies of proteins. In: Berliner LJ, Reuben J, editors. Biological magnetic resonance. Vol. 4. Plenum Press; New York: 1982. pp. 145–191. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ernst RR, Bodenhausen G, Wokaun A. Principles of nuclear magnetic resonance in one and two dimensions. Oxford University Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bevington PR, Robinson DK. Data reduction and error analysis for the physical sciences. Second. McGraw-Hill, Inc.; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walpole RE, Myers RH, Myers SL, Ye K. Probability and statistics for engineers and scientists. Eighth. Pearson Prentice Hall; New Jersey: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.States DJ, Haberkorn RA, Ruben DJ. A two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser experiment with pure absorption phase in four quadrants. J Magn Reson. 1982;48:286–292. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.