Abstract

The influence of deviant peers on youth behavior is of growing concern, both in naturally occurring peer interactions and in interventions that might inadvertently exacerbate deviant development. The focus of this special issue is on understanding the moderating and mediating variables that account for peer contagion effects in interventions for youth. This set of nine innovative papers moves the field forward on three fronts: (1) Broadening the empirical basis for understanding the conditions under which peer contagion is more or less likely (that is, moderators of effects); (2) Identifying mechanisms that might account for peer contagion effects (mediators); and (3) Forging the methodological rigor that is needed to study peer contagion effects within the context of intervention trials. We propose an ecological framework for disentangling the effects of individuals, group interactions, and program contexts in understanding peer contagion effects. Finally, we suggest methodological enhancements to study peer contagion in intervention trials.

Keywords: peer contagion, peer influences, deviant peers

Dishion, McCord, and Poulin (1999) brought attention to the possibility that systematic interventions that are aimed at reducing or preventing deviant behavior in youth might actually have adverse, or iatrogenic, effects. They drew on substantial research that suggests that association with deviant peers in the natural environment is a major factor in the growth of deviant behavior during early adolescence. They noted that the positive effects of the content of an intervention might be offset by processes of peer influence that occur when deviant youth are allowed to interact with each other. Since that time, researchers have examined the extent to which such effects occur in various interventions, the circumstances under which these effects are exacerbated or minimized, and the group-process and psychosocial mechanisms through which such effects occur.

This special issue was launched by a call for papers on this topic. We requested studies that evaluated effects associated with peer aggregation (whether positive, negative, or null), or studies that were able to identify mediating and/or moderating mechanisms accounting for peer contagion effects. Of the nine studies that survived the peer review process, six evaluated interventions that involved peer aggregation, ranging from first grade through high school. In addition, three studies revealed that school environments themselves are vulnerable to peer contagion by virtue of aggregation on playgrounds, in classrooms, and in college dormitories.

STUDIES OF PEER AGGREGATION IN INTERVENTION

Four of the six intervention studies reported in this section involve “selected” prevention strategies for child or adolescent problem behavior. Selected prevention studies are those that identify youth at-risk and then deliver interventions to prevent the escalation of problem behavior (Bryant, Windle, & West, 1997). As summarized in the review article, several of the studies documenting possible peer contagion effects in the literature have involved randomized selected prevention trials (Gifford-Smith, Dodge, Dishion, & McCord, 2005). Three of the four studies in this issue reveal that peer contagion effects undermined or reduced overall prevention effects (Boxer, Guerra, Huesman, & Morales, 2005; Cho, Halfors, & Sanchez, 2005; Mager, Milich, Harris, & Howard, 2005). The Fast Track intervention does not document main effects for the peer-group component of the intervention, but their carefully conducted analyses reveal that peer contagion in the groups was associated with increases in aggressive behavior (Lavallee, Bierman, Nix, & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2005), The distinction between treatment and selected prevention may turn out to be important in understanding peer contagion effects, as research by Lipsey (in press) reveals that only studies classified as selective prevention programs document reduced effect sizes associated with peer aggregation. There was no evidence for reduced effect sizes associated with peer aggregation in studies of the treatment of delinquent behavior in adolescence. One working hypothesis coming out of these findings is that peer contagion effects may be strongest among those youth who are either only moderately deviant or are still developing deviant behavior patterns. Among those youth who are not at all deviant or are already firmly entrenched in deviant lifestyles, the incremental effect of the peer group may be minor. This hypothesis awaits future inquiry.

The randomized treatment study by Leve and colleagues (Leve & Chamberlain, 2005) represents an important contribution to this literature. Randomly assigning serious conduct problem youth to either community group treatment or treatment foster care resulted in differential outcomes on multiple indices of adolescent problem behavior, and these differences were entirely mediated by deviant peer clustering (Leve & Chamberlain, 2005). This study also underscores the importance of adult behavior management to reduce both peer contagion processes as well as adolescent problem behavior.

STUDIES OF PEER CONTAGION IN NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS

Peer contagion may also result from aggregation that occurs in the context of education environments, ranging from preschool through college. Early research on aggression indicates in a very concrete sense that preschool children can learn aggressive behavior in their play with school age mates (Patterson, Littman, & Bricker, 1967). Systematic observational research in this special issue extends this finding, revealing that this learning is amplified by the aggregation of young children with externalizing tendencies (Hanish, Martin, Fabes, Leonard, & Herzog, 2005). This work is relevant and complementary to the observational research of Snyder and colleagues showing selective affiliation among aggressive preschoolers (Snyder, West, Stockemer, Givens, & Almquist-Parks, 1996). This finding has now been extended to elementary school.

Consistent with findings reported by Kellam and colleagues (Kellam, Ling, Merisca, Brown, & Ialongo, 1998), tracking elementary school youth into homogeneous classrooms may amplify aggressive behavior (Warren, Schoppelrey, Moberg, & McDonald, 2005). Finally, selecting roommates in college dormitories is not a benign process. The study by Duncan and colleagues is noteworthy in that the “intervention” is simply the random assignment of roommates among first year college students. Randomly pairing college males with a history of alcohol use led to a fourfold increase in drinking during the first 2 years of college (Duncan, Boisjoly, Kremer, Levy, & Eccles, 2005). The effects were not observed for females, nor were they extended to other forms of problem behavior or substance use.

MECHANISMS OF PEER CONTAGION

The articles in this section contribute to our understanding of how peer contagion effects operate. Warren et al. (2005) suggest that models of competition may account for nonlinear increases in problem behavior observed in school classrooms. Prinstein and colleagues isolate the social cognitive mechanisms that might account for the contribution of peers to adolescent problem behavior (Prinstein & Wang, 2005). These studies join the growing body of literature on deviant peer processes. The chief impediment to progress in that domain is the relative lack of experimental evidence. Almost all of the existing studies rely on cross-sectional, or at best, longitudinal studies that disentangle correlational findings through statistical controls. Such studies are always subject to unmeasured third-variable explanations for causal processes. Intervention studies offer a unique opportunity to bring experimental control to this literature.

A careful reading of the innovative papers in this special issue suggests that a general framework of intervention science is needed. Such a framework would prescribe the kinds of measures to be collected, the data analyses to be conducted, and the range of effects to be reported. A general strategy for conducting and reporting outcomes of intervention trials would certainly assist the field in understanding the collective benefits as well as negative side effects of interventions that select peer aggregation as the venue for improving the mental health of children and adolescents.

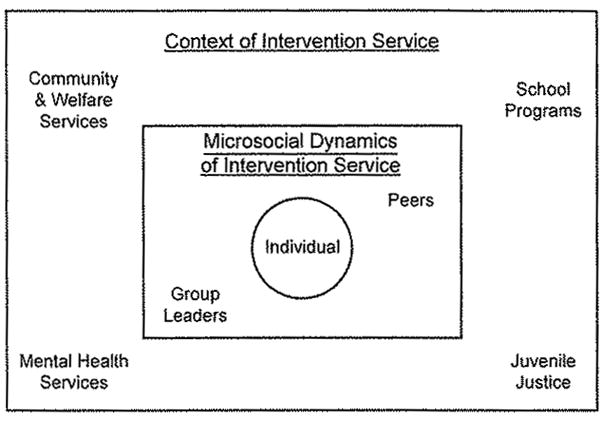

Within the context of developmental science, an ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1989) has been invoked as an integrative framework for systematically studying the dynamics of development. We suggest that an ecological framework would be useful for integrating developmental, experimental psychopathology, and intervention research in advancing our understanding of peer contagion effects, and the circumstances under which such effects would be amplified or minimized (see Fig. 1). It is important to note that the ecological perspective is not a theory of behavior but, rather, a conceptual heuristic for disentangling levels of influence.

Fig. 1.

An ecological framework for understanding deviant peer contagion.

Inspection of Fig. 1 reveals three levels of analysis pertinent to understanding deviant peer contagion within the context of intervention research. The individual level refers to characteristics of intervention recipients that may influence their response to an intervention service. For example, individuals may understand or react to an intervention in such a way that they may deteriorate on the very dimension that the program is intended to improve. In this special issue, two mechanisms have been suggested, including the false consensus bias (Prinstein & Wang, 2005) and competition (Warren et al., 2005). In addition to these factors, one might consider the child’s temperament, age, gender, and behavioral and learning history as factors accounting for individual differences in reacting to interventions that involve peer aggregation. At this stage of the science, it appears that peer contagion is possible from early childhood through adolescence, but it is clear that the specific behaviors that are more susceptible to peer contagion vary across age and gender (Duncan et al., 2005; Hanish et al., 2005).

It is important that the individual-level factors be linked to mechanisms, so that our understanding of the dynamics of peer contagion are advanced (Dishion, in press). Behavioral mechanisms are studied at the second level of analysis depicted in Fig. 1, often referred to as the microsocial mechanism (i.e., relationship processes). For example, a competition model was tested and supported in the work of Warren et al. (2005) to account for increases in aggressive behavior in classrooms marked by high levels of aggression. However, a competition model would also be consistent with deviancy training dynamics that involve positive reinforcement from peers for verbal and nonverbal deviant behavior (Dishion, Spracklen, Andrews, & Patterson, 1996). Deviancy training in the Fast Track social skills training groups was associated with increases in aggressive behavior (Lavallee et al., 2005). Snyder et al. (in press), in the context of kinder-garten classrooms, recently documented deviancy training among 5-year-old children. Randomly selecting classmates and videotaping their play sessions revealed that deviancy training accounted for escalations in antisocial behavior over the ensuing two years (Snyder et al., in press), Dishion and colleagues found that deviancy training among young adolescents during informal periods of a cognitive behavioral intervention was associated with increases in self reported smoking and teacher reported delinquent behaviors in the 3 years immediately following the group sessions (Dishion, Burraston, & Poulin, 2001). Note that the deviancy training dynamic is a process, and may or may not occur depending on the characteristics of the participants, the skill of the group leader, and the context of the intervention. For example, the work by Mager et al. (2005) suggests that mixed groups may be more detrimental than purely deviant groups. The study by Boxer and colleagues is consistent with the idea that peer influence may be greatest in mixed groups of youth (Boxer et al., 2005). This finding may be particularly relevant for explaining the potential heightened risk of selected prevention strategies for producing peer contagion effects, and for explaining why treatment programs consisting of homogeneous groups of problematic youth tend to produce positive effects on key dependent variables (e.g., Dennis et al., 2004; Lochman, 1992; Waldron, Sharry, Fitzpatrick, Behan, & Carr, 2002). In stark contrast with this perspective is the work of Feldman, Caplinger, and Wodarski (1983), indicating that mixed intervention groups bring more favorable outcomes than groups wholly constituted by deviant youth.

The complexity of the problem is highlighted by considering the need for a third level of analysis, when studying peer contagion effects, that is the context within which the intervention is embedded. As noted in Fig. 1, there are four primary contexts considered with respect to deviant peer contagion. The first context includes interventions that are delivered within the community, such as welfare services or other community programs including after school programs, gang prevention programs, recreational centers, or summer camps. The second context involves programs that are delivered within the context of a public school environment. This may include “pull out” programs that contrive a special context in a mainstream public school, or the creation of an alternative school environment. A third context is the provision of outpatient or inpatient mental health services, including substance use treatment programs. Although few studies have addressed peer contagion in inpatient mental health and substance use settings, there are likely features of such programs that may contribute to or detract from intervention goals. Thus, mental health settings provide yet another systemic level of analysis for the potential study of iatrogenic effects due to aggregation. A fourth context is the juvenile justice center, typically involving programs delivered within a community, but one that may include a variety of aggregation strategies ranging from weekly groups, to residential containment that last for weeks, months, or even years within state institutions.

An important feature of an ecological perspective is the ability to conceptualize and test interaction effects among levels of analysis. That is, it is very possible that some vulnerable individuals (e.g., young adolescents with marginal peer relationships) may escalate in problem behavior by virtue of informal interactions among peers that are facilitated by the service being offered at night in a community setting (e.g., they walk home together and have a cigarette). The point is that if this hypothesis were found to be true, then the iatrogenic effect would be explained by a two- to three-way interaction among three levels of analysis. Given the literature on deviant peer contagion contained in this special issue, it is probably true that negative effects are a joint function of the developmental status of the individual, the informal and formal interactions of the participants, and the context of the program or service. Therefore, an ecological framework would seem to be a useful heuristic for considering the further study of iatrogenic effects.

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The set of studies in this special issue stimulate as many questions as they answer regarding the circumstances under which peer contagion may undermine or enhance intervention outcome. In this sense, this special section on peer contagion serves as a beacon for an advancing and increasingly sophisticated intervention science. We highlight three methodological advances in intervention research that would increase the database for understanding the specific mechanisms underlying intervention effectiveness in general, and peer contagion processes in particular:

Studying and reporting the benefits and side effects: Community psychologists, for some time, have been aware that the same intervention can have benefits as well as negative side effects (Kelly, 1987). Our colleague, Professor Joan Mc Cord, to whom this special issue is dedicated, was an inspiration in this regard in her pioneering evaluation of the monumental Cambridge-Somerville prevention trial (Mc Cord, 1978,Mc Cord, 1981,Mc Cord, 1992). Intervention research is not for the timid, in that effects may sometimes be disappointing at best and iatrogenic at worst. To face this challenge of intervention science, courageous examples of objectivity (including those in this special issue) inspire the field to advance in the task of applying science and designing effective mental health interventions. In this regard, we should assume that some interventions may be helpful for some behaviors, but harmful for others. For example, Dishion and Andrews (1995) found that the cognitive behavioral peer group intervention improved observed family interactions but had a harmful effect on tobacco use and delinquent behavior. Reporting positive effects with side effects might become a standard for intervention science, much like pharmacological research

-

Measuring and analyzing multiple levels of intervention strategies: The ecological perspective on intervention research requires a new level of sophistication. One challenge is measurement. As indicated by the studies in this special issue, to understand the mediating factors, it is necessary to measure the relevant (level 2) intervention processes (e.g., deviancy training in the Lavellee et al. [2005] analysis of the Fast Track data). We have found that videotapes of intervention sessions are more valuable than therapist and client ratings of sessions. This may occur because the kinds of interpersonal dynamics that influence change as a function of peer contagion may be difficult to track cognitively by the participants, or even the group leaders. Indeed, many of the relevant peer interactions may occur outside of the group leader’s awareness. Thus, the study of peer contagion would benefit from the development of measures that could be used across intervention contexts. In addition to measuring the microsocial processes underlying peer contagion influences, measures of the intervention context are important to understanding the conditions under which peer contagion is most likely to occur. Work by Mager et al. (2005) and Boxer et al. (2005) are exemplary in this regard.

The measurement of multi-level aspects of an intervention demands more sophisticated modeling than the typical group-by-time repeated measures analysis of variance. Innovations in multivariate modeling, as exemplified in this special issue, are now available for disentangling individual, group, and context effects within intervention science and should be used accordingly (Muthén & Muthén, 2001; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Studying existing program, institutional, and intervention practices: It is tempting in intervention research to cease and desist when an intervention strategy appears to yield negative effects. However, it is critical to recall that the strength of behavioral science is in replication, and review of a multitude of studies on the same topic in order to determine the reliability of a negative effect, as well as the identification of conditions under which negative effects increase in likelihood. Thus, we should continue randomized studies that include interventions that aggregate peers until it is clear under what conditions peer contagion effects can be expected.

It is clear that the majority of interventions and institutional practices involve the explicit or implicit aggregation of children and adolescents into groups. As revealed by the work in this special issue, creative efforts to study existing practices are both ethical and constructive to the science. For example, assignment of roommates in college is often haphazard. Duncan et al. (2005) demonstrate that it is relatively simple to take the haphazard and render it scientifically random, and learn from the ensuing results. This principle can be applied to many existing practices, both intervention and institutional, that are likely to affect the lives of children and adolescents. In this sense, intervention science benefits by moving from the laboratory of university clinics to the real world ecology of service delivery, education, and juvenile justice programs. In this way, a general set of principles can be developed that apply to an emerging theory of intervention that is grounded in both developmental theory and accumulative experience of efforts to change behavior.

References

- Boxer P, Guerra NG, Huesman LR, Morales J. Proximal peer-level effects of small group selected prevention on aggression in elementary school children: An investigation of the peer contagion hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:325–338. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and by design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of child development, Vol. 6. Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues. London: Jai; 1989. pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG. The science of prevention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Halfors D, Sanchez V. Evaluation of a high school peer group intervention for at risk youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:363–374. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3574-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ. Deviant peer contagion within interventions and programs: An ecological framework for understanding influence mechanisms. In: Dodge K, Dishion T, editors. Deviant by design: Interventions and policies that aggregate deviant youth and strategies to optimize outcomes. New York: Guilford; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW. Preventing escalation in problem behaviors with high-risk young adolescents: Immediate and 1-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:538–548. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Burraston B, Poulin F. Peer group dynamics associated with iatrogenic effects in group interventions with high-risk young adolescents. In: Erdley C, Nangle DW, editors. Damon’s new directions in child development: The role of friendship in psychological adjustment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DW, Patterson GR. Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Boisjoly J, Kremer M, Levy DM, Eccles J. Peer effects in drug use and sex among college students. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:375–385. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3576-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman RA, Caplinger TE, Wodarski JS. The St. Louis conundrum: The effective treatment of antisocial youths. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hail; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Smith M, Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, McCord J. Peer influence in children and adolescents: Crossing the bridge from developmental to intervention science. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:255–265. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3563-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Martin CL, Fabes RA, Leonard S, Herzog M. Exposure to externalizing peers in early childhood: Homophily and peer contagion processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:267–281. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3564-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam S, Ling X, Merisca R, Brown H, Ialongo N. The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into the middle school. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:165–185. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JG. An ecological paradigm: Defining mental health consultation as a preventive service. In: Kelly JG, Hess RE, editors. The ecology of prevention: Illustrating mental health consultation. New York: Haworth; 1987. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lavallee KL, Bierman KL, Nix RL The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. The impact of first-grade “friendship group” experiences on child social outcomes in the Fast Track Program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:307–324. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3567-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P. The effects of gender and intervention context on delinquency for youth in the juvenile justice system. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey M. The effects of community-based group treatment for delinquency: A meta-analytic search for cross-study generalizations. In: Dodge K, Dishion T, editors. Deviant by design: Interventions and policies that aggregate deviant youth and strategies to optimize outcomes. New York: Guilford; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE. Cognitive-behavioral intervention with aggressive boys: Three-year follow-up and preventive effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:426–432. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager W, Milich R, Harris MJ, Howard A. Intervention groups for adolescents with conduct problems: Is aggregation harmful or helpful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3572-6. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. A third-year follow-up of treatment effects. American Psychologist. 1978;37:1477–1486. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.33.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. Consideration of some effects of a counseling program. In: Martin SE, Sechrest LB, Redner R, editors. New directions in the rehabilitation of criminal offenders. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1981. pp. 394–405. [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. The Cambridge-Somerville Study: A pioneering longitudinal-experimental study of delinquency prevention. In: McCord J, Tremblay RE, editors. Preventing antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence. New York: Guilford; 1992. pp. 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus statistical analysis with latent variables. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Littman RA, Bricker W. Assertive behavior in children: A step toward a theory of aggression. Monographs for the Society for Research in Child Development. 1967;32:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Wang SS. False consensus and adolescent peer contagion: Examining discrepancies between perceptions and actual reported levels of friends’ deviant and health risk behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:293–306. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Schrepferman L, Oeser J, Patterson G, Stoolmiller M, Johnson K. Peer deviancy training and affiliation with deviant peers in young children: Occurrence and contributions to early-onset conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050194. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, West L, Stockemer V, Givens S, Almquist-Parks L. A social learning model of peer choice in the natural environment. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1996;17:215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron B, Sharry J, Fitzpatrick C, Behan J, Carr A. Measuring children’s emotional and behavioural problems: Comparing the Child Behaviour Checklist and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Irish Journal of Psychology. 2002;23(12):18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Warren K, Schoppelrey S, Moberg DP, McDonald M. A model of contagion through competition and aggressive behavior of elementary students. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:283–292. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3565-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]