Abstract

In various excitable tissues, the hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated current (Ih) contributes to burst firing by depolarizing the membrane after a period of hyperpolarization. Alternatively, conductance through open channels Ih channels of the resting membrane may impede excitability. Since primary sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglion show both loss of Ih and elevated excitability after peripheral axonal injury, we examined the contribution of Ih to excitability of these neurons. We used a sharp electrode intracellular technique to record from neurons in nondissociated ganglia to avoid potential artefacts due to tissue dissociation and cytosolic dialysis. Neurons were categorized by conduction velocity. Ih induced by hyperpolarizing voltage steps was completely blocked by ZD7288 (approximately 10μM), which concurrently eliminated the depolarizing sag of transmembrane potential during hyperpolarizing current injection. Ih was most prominent in rapidly conducting Aα/β neurons, in which ZD7288 produced resting membrane hyperpolarization, slowed conduction velocity, prolonged action potential (AP) duration, and elevated input resistance. The rheobase current necessary to trigger an AP was elevated and repetitive firing was inhibited by ZD7288, indicating an excitatory influence of Ih. Less Ih was evident in more slowly conducting Aδ neurons, resulting in diminished effects of ZD7288 on AP parameters. Repetitive firing in these neurons was also inhibited by ZD7288, and the peak frequency of AP transmission during tetanic bursts was diminished by ZD7288. Slowly conducting C-type neurons showed minimal Ih, and no effect of ZD7288 on excitability was seen. After spinal nerve ligation, axotomized neurons had less Ih compared to control neurons and showed minimal effects of ZD7288 application. We conclude that Ih supports sensory neuron excitability, and loss of Ih is not a factor contributing to increased neuronal excitability after peripheral axonal injury.

1. Introduction

Damage to the axons of peripheral sensory neurons may result in chronic neuropathic pain in human subjects. Numerous sequelae ensue at locations along the sensory pathway, including the brain and spinal cord. Altered properties of the sensory neuron itself may be noted at both the injury site and in the neuronal somata in the dorsal root ganglion proximal to the injury, where shifts in expression and function of voltage gated channels in the contribute to an altered biophysical phenotype. Specifically, diminished tetrodotoxin-insensitive Na+ current and increased tetrodotoxin-sensitive current (Cummins et al., 2000), diminished K+ currents (Everill and Kocsis, 1999; Sarantopoulos et al., 2007), and diminished high voltage-activated (Abdulla and Smith, 2001; Baccei and Kocsis, 2000; Hogan et al., 2000; McCallum et al., 2006) and low-voltage-activated (McCallum et al., 2003) currents may each contribute to hyperexcitability noted in DRG neurons after axotomy (Sapunar et al., 2005).

The hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated current, also termed the anomalous rectifier current or H-current (Ih), is expressed in sensory neurons, particularly large neurons with myelinated axons (Scroggs et al., 1994; Tu et al., 2004; Vasilyev et al., 2007). This current is activated by membrane potentials negative to −60mV (Yao et al., 2003) and does not inactivate, and therefore is in a conducting state at resting membrane potentials (RMPs) typical of sensory neurons. Neuronal Ih channels conduct Na+ and K+ and exhibit a reversal potential of approximately −35mV (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996; Mayer and Westbrook, 1983; Mercuri et al., 1995; Yagi and Sumino, 1998), so their activation usually results in depolarization of the neuronal membrane potential.

In various neuronal cell types, Ih has been demonstrated to influence neuronal excitability through two opposing properties. The activation of Ih upon membrane repolarization following an action potential (AP) results in a depolarization that may initiate subsequent APs and a rhythmic burst, especially in conjunction with T-type calcium current (Pape, 1996). Accordingly, Ih has been shown to support spontaneous burst firing in most brain sites (Chan et al., 2004; Ghamari-Langroudi and Bourque, 2000; Lupica et al., 2001; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996; Tanaka et al., 2003), although not all (Mercuri et al., 1995). In contrast to this excitatory influence, ionic conductance through Ih channels reduces the input resistance of neurons and thereby limits AP initiation in response to a depolarizing current (Doan et al., 2004; Gasparini and DiFrancesco, 1997; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996). Since Ih is expressed in axons (Birch et al., 1991; Takigawa et al., 1998), reduced input resistance may increase conductance failure through points of impedance mismatch, such as the T-branch where the central and peripheral limbs of the sensory neuron axon meet with the axonal stem that leads to the neuronal soma (Luscher et al., 1994; Stoney, 1985).

In a prior investigation (Sapunar et al., 2005), we have noted a significant loss of the hyperpolarization-induced transmembrane potential relaxation (“sag”) in sensory neurons after axotomy. Since the sag phenomenon is attributable to Ih (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996; Tanaka et al., 2003; Yao et al., 2003), we hypothesized that loss of Ih may contribute to the hyperexcitability also seen in sensory neurons following axotomy (Sapunar et al., 2005). Few observations are available to discern the role of Ih in sensory neurons. Block of Ih with the nonspecific agent clonidine resulted in reduced repetitive firing in partially digested DRG neurons (Yagi and Sumino, 1998), as did the specific agent ZD7288 in a small number of dissociated DRG neurons (Tu et al., 2004). However, measurement of Ih is influenced by both temperature and cytoplasmic dialysis (Cuevas et al., 1997), and dissociation produces an injury-like effect on neuronal excitability (Zheng et al., 2007). We have therefore examined the regulation of sensory neuronal excitability by Ih, using ZD7288 to selectively block Ih (BoSmith et al., 1993; Larkman and Kelly, 2001; Satoh and Yamada, 2000) in neurons of nondissociated DRGs at 35°C, using a sharp electrode technique that limits cellular alterations associated with patch dialysis (Blatt and Slayman, 1983).

2. Results

2.1 Ih in neurons of non-dissociated DRGs

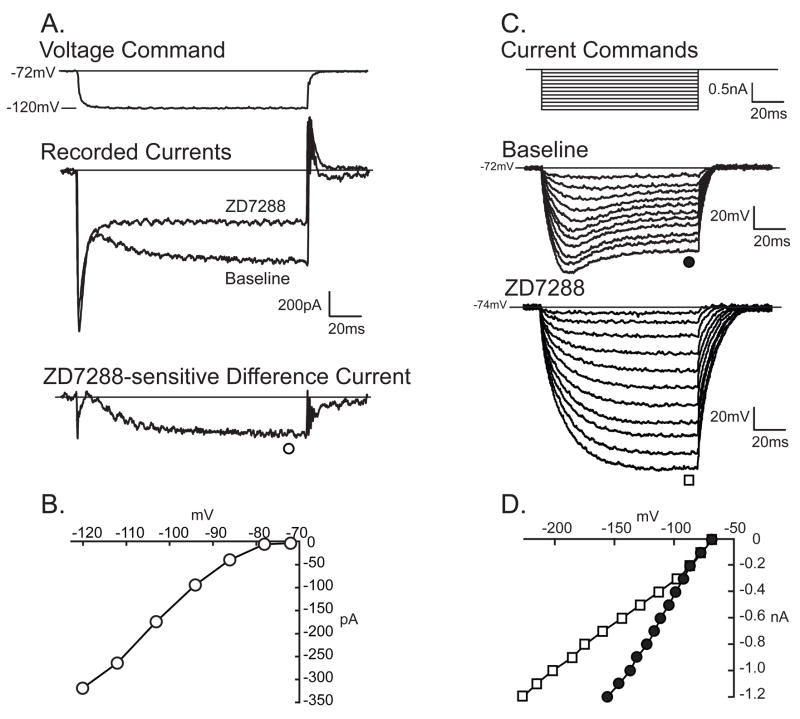

Discontinuous single-electrode voltage clamp (DSEVC) recording was employed to confirm blockade of Ih by ZD7288. Ih was identified during as a slowly developing inward current during hyperpolarizing voltage commands (Fig. 1A). ZD7288 (approximately 10μM, see methods) was delivered via a pressurized system. Control experiments with comparable application of vehicle without ZD7288 produced no changes in measured parameters (data not shown). Three minute application of ZD7288 resulted in complete inhibition of the time-dependent component of inward current (Fig. 1A, Table 1), which confirms the identity of this component as Ih and allows its measurement as the difference current obtained by digitally subtracting the baseline trace from the post-ZD7288 trace (Fig. 1B). The functional effect of Ih may be discerned in its production of the transmembrane potential sag, seen in discontinuous current-clamp (DCC) mode as a slowly developing depolarization during sustained hyperpolarizing current pulses recorded (Fig. 1C,D). In the same neurons in which Ih was blocked by ZD7288, sag was also entirely eliminated (Fig 1C, Table 1), which confirms that Ihgenerates the sag. This causal relationship is further supported by the strong cell-by-cell correlation (R=0.80, P<0.001) between Ih and sag, which was measured as the percentage return of the potential back to RMP (Villiere and McLachlan, 1996).

Figure 1.

H-current (Ih) in sensory neurons. A. In discontinuous single electrode voltage-clamp mode, hyperpolarizing voltage commands (top panel, recorded actual voltage) produce a immediate inward current and an additional slowly activating component that is sensitive to ZD7288 (middle panel), shown as the digitally subtracted difference current (bottom panel), in an Aα/β neuron. B. The current-voltage (I–V) relationship for Ih in this neuron. C. In the same neuron, discontinuous current clamp mode, hyperpolarizing current injections through the recording electrode (top panel) elicit time-dependent and voltage-dependent inward rectification (“sag”, middle panel), that is eliminated by ZD7288 (approximately 10μM, bottom panel). D. The I–V relationship shows the loss of sag during ZD7288 administration (open squares) compared to baseline conditions (filled circles).

Table 1.

Effects of H-current blocker ZD7288 on function of control dorsal root ganglion neurons.

| Ih (pA) |

Sag ratio (%) |

RMP (mV) |

CV (m/s) |

Apamp (mV) |

AP95% (ms) |

AHPamp (mV) |

AHP80% (ms) |

AHParea (mV·ms) |

Rin (MΩ) |

Rheobase (nA) |

Following Freq. ( Hz) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aα/β

n=23 |

BL | 297 ±94 | 24.5±12.1 | −70.5±8.1 | 24.3±7.0 | 72.7±9.1 | 0.72±0.22 | 10.8±4.2 | 21.5±20.4 | 287±342 | 46±19 | 3.3±1.6 | 387±220 |

| ZD | 0.0±0.0*** | 0.0±0.0*** | −71.6±9.4* | 23.8±6.8*** | 73.1±10.9 | 0.76±0.17* | 10.9±4.9 | 41.6±69.6 | 347±451 | 61±25*** | 3.6±1.6* | 387±212 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

|

Aδ

n=19 |

BL | 163±129 | 14.2±13.9 | −71.4±10.4 | 8.1±2.1 | 71.2±10.3 | 1.57±0.86 | 8.1±5.0 | 53±53 | 1165±1454 | 75±42 | 2.6±1.8 | 155±116 |

| ZD | 0.0±0.0** | 0.0±0.0*** | −71.8±10.2 | 8.3±1.6 | 70.6±12.6 | 1.82±1.94 | 9.0±5.2** | 156±468 | 1238±2195 | 85±38* | 3.1±1.9 | 105±88* | |

|

| |||||||||||||

|

C

n=8 |

BL | 12±21 | 1.4±3.3 | −63.4±4.1 | 0.5±0.1 | 76.2±12.5 | 3.31±0.55 | 14.3±5.4 | 41.5±14.6 | 2470±3023 | 153±28 | 1.2±0.3 | |

| ZD | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | −60.9±8.6 | 0.5±0.1 | 75.0±9.2 | 3.78±1.65 | 16.1±2.8 | 34.1±11.2* | 3456±3569 | 136±57 | 1.0±0.3 | ||

Ih, H-current measured at during 150ms step to −120mV; ZD, ZD7288 (10μM); BL, Baseline condition; RMP, resting membrane potential; CV, conduction velocity; APamp, action potential amplitude; AP95%, action potential duration at 95% of amplitude; AHPamp, afterhyperpolarization amplitude; AHP80%, afterhyperpolarization duration at 80% of amplitude; AHParea, afterhyperpolarization area under the curve; Rin, input resistance. Values are given as mean ± SD.

P<0.05,

P <0.01,

P <0.001 vs. baseline.

Reliable membrane capacitance determination is not possible using our recording technique due to the influence of space-clamp limitations in non-dissociated tissue, so Ih was not normalized for capacitance. The larger size of Aα/β neurons (47±6μm) compared to Aδ (37±3μm) and C-type neurons (34±3μm) may in part contribute to the larger Ih. However, as a reflection of current density, the functional impact of Ih may be estimated by the degree of sag in the different categories of neurons (Table 1). The prominent sag in Aα/β-type neurons, compared to a smaller average sag in Aδ and near absence in C-type neurons, indicates that the large Ih recorded in Aα/β neurons and intermediate Ih recorded in Aδ do not represent merely the larger size of these neurons in comparison to the slight Ih in C-type neurons.

2.2 Functional role of Ih in DRG neurons

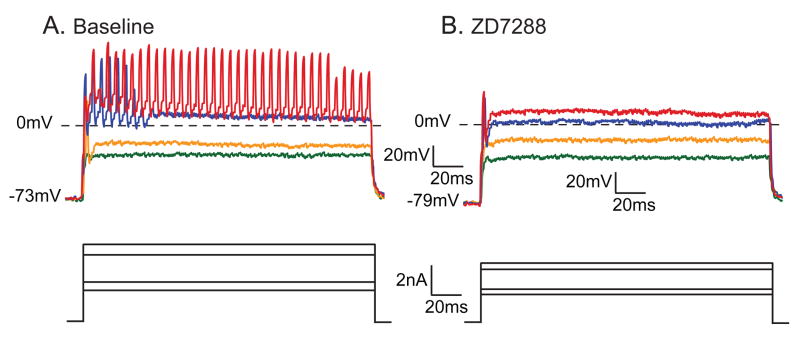

The influences of Ih blockade with ZD7288 upon action potential (AP) parameters (Fig. 2) and neuronal excitability (Table 1) were determined in neurons grouped by conduction velocity (CV).

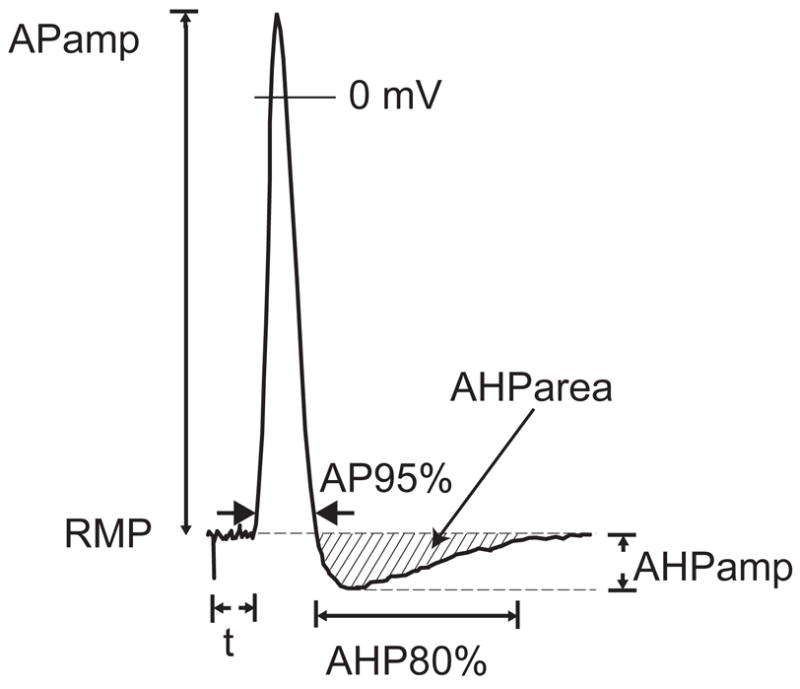

Figure 2.

Measured action potential (AP) parameters. RMP, resting membrane potential; APamp, amplitude of AP; AP95%, duration of AP after 95% repolarization; t, latency following axonal stimulation; AHPamp, amplitude of afterhyperpolarization; AHP80%, duration of afterhyperpolarization until 80% recovery to baseline; AHParea, area of the AHP.

The majority of neurons in the Aα/β category conduct non-nociceptive sensory information (Lawson, 2002). Block of Ih in this group resulted in small but significant hyperpolarization of RMP, attributable to removal of a resting conductance through the noninactivating Ih channels. This is also demonstrated by an increased input resistance during Ih blockade. Loss of Ih also resulted in slight slowing of conduction velocity, consistent with the expression of these channels in the axons of DRG neurons (Birch et al., 1991), where they support conduction (Grafe et al., 1997). Despite an increase in input resistance, the rheobasic current necessary to initiate an AP was elevated by ZD7288, indicating an excitatory influence of Ih. This was also evident in the firing patterns elicited by further depolarization, during which 7 of 8 repetitively firing Aα/β neurons showed decreased AP generation after ZD7288 (4.7±2.7 APs at baseline, 2.0±1.8 APs during ZD7288, P=0.023, n=8; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of ZD7288 (approximately 10μM) on firing pattern of an Aα/β neuron during injection of depolarizing current through the recording electrode using discontinuous current clamp, during baseline conditions (A.) and during administration of ZD7288 to the same neuron (B.). In both cases, the upper panel shows voltage traces in response to the current commands shown in the lower panel. Traces in the two conditions are selected to show events at comparable degrees of membrane depolarization. As demonstrated by this neuron, ZD7288 hyperpolarized the resting membrane potential, increased the input resistance of the neuron from 22.5MΩ to 35.7MΩ, increased the voltage necessary to initiate an action potential, and eliminated this neuron’s ability to fire multiple action potentials in response to sustained depolarization.

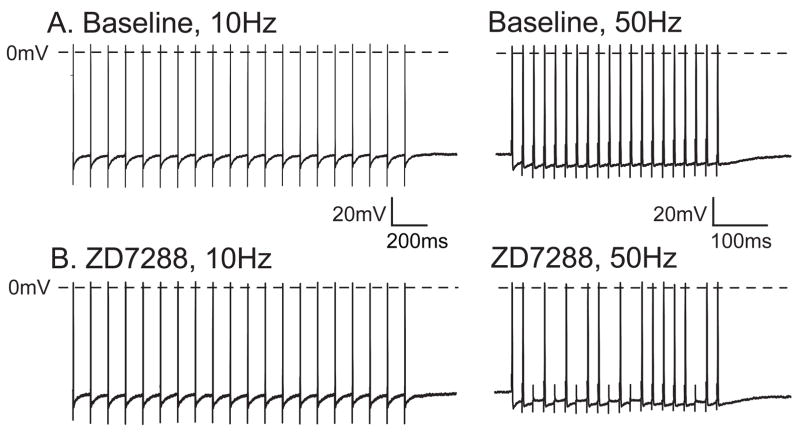

In Aδ neurons, which generally conduct nociceptive afferent traffic, a diminished effect of ZD7288 was seen compared to Aα/β neurons. A smaller fractional increase in input resistance was seen (10% in Aδ vs. 28% in Aα/β neurons), no significantly RMP hyperpolarization developed, and rheobase was not significantly affected. However, 5 of 6 repetitively firing neurons in this category also demonstrated decreased AP generation after ZD7288 (4.5±3.0 APs at baseline, 2.1±2.4 APs during ZD7288, P=0.026, n=6). The ability of the neurons to successfully conduct bursts of APs during tetanic axonal stimulation (following frequency) was also diminished in Aδ neurons (Fig. 4, Table 1). Following frequency is limited by currents that underlie the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) (Luscher et al., 1994), which increased in amplitude during ZD7288 administration in Aδ neurons. This may result from preferential activation of Ih during the AHP (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996). The absence of this effect in Aα/β neurons may be a consequence of the different Ih kinetics in these DRG neuronal populations (Tu et al., 2004).

Figure 4.

Effect of ZD7288 (approximately 10μM) on the ability of an A∂ neuron to conduct action potentials into the soma during tetanic stimulation. Under baseline conditions (A.), the neuronal soma can follow at 10Hz (left panel) and maintain successful firing at 50Hz (right panel), but the same neuron during ZD7288 (B.) drops action potentials at 50Hz (right panel). Note that the time scale is not the same in the right and left panels.

In slowly conducting, mostly nociceptive C-type neurons, the only change noted during ZD7288 administration was a diminished AHP duration (Table 1). Since only a very slight ZD7288-sensitive Ih was observed during DSEVC, this finding is unlikely to be attributable to loss of Ih. No change in firing pattern was noted in 7 repetitively firing C-type neurons (1.4±1.1APs at baseline, 2.3±1.7APs during ZD7288, P=0.18).

2.3 Ih in axotomized DRG neurons

The main goal of this study was to identify whether increased excitability seen after sensory neuron injury can be attributed to the loss of Ih. Data presented so far indicates a contrary finding that selective loss of Ih does not increase neuronal excitability. It is possible, however, that residual Ih in injured neurons could have a different functional role in the context of diverse axotomy-induced cellular alterations compared to the context of an uninjured neuron. We therefore examined the effect of ZD7288 on sensory neurons from rats subjected to spinal nerve ligation (SNL), which produced hyperalgesia (34±14% hyperalgesic responses to plantar application of a pin, n=4 rats vs, 0±0% in control animals, n=18 rats). Compared to neurons from control animals, neurons in DRGs removed 19±3 days after SNL showed a diminished Ih (Table 2) in both Aα/β neuron (P<0.01) and Aδ neurons (P<0.01), with proportionately smaller voltage sag. Application of ZD7288 to axotomized sensory neurons produced minimal functional changes (Table 2). Unlike control neurons, firing rate in repetitively firing axotomized neurons had no consistent response to ZD7288 (2.3±0.8 APs at baseline, 2.2±1.2 APs during ZD7288, P=0.5, n=6).

Table 2.

Effects of H-current blocker ZD7288 on function of axotomized dorsal root ganglion neurons.

| Ih (pA) |

Sag ratio (%) |

RMP (mV) |

CV (m/s) |

Apamp (mV) |

AP95% (ms) |

AHPamp (mV) |

AHP80% (ms) |

AHParea (mV·ms) |

Rin (MΩ) |

Rheobase (nA) |

Following Freq. (Hz) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aα/β

n=7 |

BL | 91±167 | 5.3±7.0 | −66.4±6.6 | 19.5±7.3 | 81.3±7.7 | 0.78±0.17 | 13.2±3.8 | 51.9±33.6 | 696±360 | 29±16 | 3.4±2.1 | 328±255 |

| ZD | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0* | −66.7±7.0 | 19.2±8.2 | 83.3±5.0* | 0.77±0.19 | 14.4±2.8 | 43.4±35.0 | 696±452 | 31±16 | 3.4±2.0 | 253±215 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

|

Aδ

n=8 |

BL | 7±15 | 0.8±1.8 | −65.6±6.7 | 7.9±2.8 | 80.0±9.4 | 1.20±0.26 | 13.6±3.7 | 98.8±68.6 | 1587±1484 | 44±12 | 3.2±1.8 | 103±113 |

| ZD | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | −65.0±6.7 | 7.9±2.7 | 77.9±9.7* | 1.29±0.39 | 14.0±3.0 | 88.7±69.2 | 1484±1351 | 40±14 | 2.1±1.3 | 113±131 | |

Ih, H-current measured at during 150ms step to −120mV; ZD, ZD7288 (10μM); BL, Baseline condition; RMP, resting membrane potential; CV, conduction velocity; APamp, action potential amplitude; AP95%, action potential duration at 95% of amplitude; AHPamp, afterhyperpolarization amplitude; AHP80%, afterhyperpolarization duration at 80% of amplitude; AHParea, afterhyperpolarization area under the curve; Rin, input resistance. Values are given as mean ± SD.

P<0.05,

P <0.01,

P <0.001 vs. baseline.

3. Discussion

The observations reported here are the first to use a microelectrode recording technique in nondissociated DRGs to define the functional role of Ih in primary sensory neurons. These technical details may have critical importance. Ih in primary sensory neurons is highly sensitive to cytosolic cyclic nucleotides and to ATP, both producing a positive shift in the activation curve (Ingram and Williams, 1996; Komagiri and Kitamura, 2003). Ih is also sensitive to cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels (Pan, 2003; Schwindt et al., 1992). These mechanisms may explain neuronal Ih sensitivity to temperature and to cytoplasmic dialysis by patch electrodes (Cuevas et al., 1997). Using a microelectrode method that minimizes dialysis (Blatt and Slayman, 1983) and 35ºC bath temperature may help avoid disruption of natural cytosolic conditions that regulate Ih. Preservation of the natural ganglionic environment and neuron/glial interactions by avoiding dissociation may add further validity to our observations, particularly regarding neuronal excitability. Although this preparation is not perfused, the bicarbonate-based bath solution is oxygenated and only superficial neurons were impaled. Also, the dorsal root must be sectioned, but at a much greater distance from the soma than occurs with dissociation, which thereby avoids the immediate phenotypic shifts that follow dissociation (Zheng et al., 2007). Our findings confirm that DRG neurons possess inward currents induced by hyperpolarization that are characteristic of Ih. Similar to previous observations (Scroggs et al., 1994), we found Ih is maximal in rapidly conducting sensory neurons.

We performed this study to test whether loss of Ih may contribute to the hyperexcitability seen in sensory neurons after peripheral nerve injury. Specifically, rheobase is diminished after spinal nerve ligation in both Aα/β and Aδ neurons, while repetitive firing during depolarization is elevated in Aδ neurons (Sapunar et al., 2005). Axotomy has been shown to reduce sag (Sapunar et al., 2005) and Ih (Abdulla and Smith, 2001) in rat DRG neurons, so a possible stabilizing effect of Ih on DRG neurons might be considered. However, contrasting findings have also been reported. Elevated pain behavior that follows peripheral nerve injury is decreased after ZD7288 given systemically (Chaplan et al., 2003) or applied to the nerve injury site (Dalle and Eisenach, 2005). However, intrathecal ZD7288 has no effect on injury-induced pain behavior (Chaplan et al., 2003), and the mechanistic insights from these in vivo experiments are limited since the tissue site of action cannot be discerned. Also, while Chaplan et al. (Chaplan et al., 2003) showed increased Ih in DRG neurons after axotomy, interpretation of that study is complicated by their concurrent finding that injury decreases expression of protein and message for HCN1 and HCN2, the principal genes encoding Ih channels in sensory neurons.

Sensory neuron axotomy is followed by numerous changes in cellular processes. In order to isolate the effects of Ih loss, we examined the effects of ZD7288 on uninjured neurons. Our present findings do not support our hypothesis that diminished Ih contributes to increased excitability of DRG neurons after axonal injury, but rather indicate the opposite. With Ih blockade by ZD7288, rheobase increased in Aα/β neurons despite an elevated input resistance, and no effect was seen in slower conducting neurons. The generation of repetitive APs during membrane depolarization was diminished in Aα/β and Aδ neurons during ZD7288 application, as was the ability of Aδ neurons to conduct rapid trains of APs through the T-branch and into the cell soma. The use of ZD7288 is a reliable means of identifying the role of Ih as prior reports have noted an absence of effects of ZD7288 on conductances other than Ih (BoSmith et al., 1993; Larkman and Kelly, 2001). Consistent with this, our findings confirm a complete elimination of Ih that accompanies these manifestations of depressed neuronal excitability. We note, however, a reduction in AHP duration in C-type neurons with application of ZD7288, possibly indicating an effect on currents other than Ih, as has been noted in prior reports (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2002; Ghamari-Langroudi and Bourque, 2000).

We found diminished Ih after axotomy by SNL, which confirms that our previous finding of diminished sag after injury (Sapunar et al., 2005) is due to loss of Ih. Application of ZD7288 to these injured sensory neurons had a diminished effect compared to control neurons, such that Ih blockade had no effect on RMP, AP duration, rheobase, or repetitive firing properties after axotomy. This suggests that the residual Ih in injured neurons plays no particular role in supporting hyperexcitability.

We conclude that axotomy-induced excitability in sensory neurons is attributable to events other than loss of Ih. Indeed, the loss of Ih might be considered a compensatory measure in the context of injury. While the present experiments do not indicate a mechanism by which Ih in decreased after axotomy, it is possible that axotomy-induced depression of both resting levels of cytosolic Ca2+ as well as the transient rises of Ca2+ that accompany neuronal activation (Fuchs et al., 2005; Fuchs et al., 2007) may result in lowered activity of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, which is a regulator of Ih activity (Fan et al., 2005; Rigg et al., 2003).

4. Experimental Procedures

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

4.1 Animal subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic Farms Inc., Hudson, NY) weighing 200–300 g were used. In a subset of animals, neuropathic pain behavior was induced by spinal nerve ligation (SNL). During isoflurane anesthesia (2% in oxygen), the spinal nerves at the fifth lumbar (L5) and L6 levels were exposed, ligated with 6-0 silk ligature, and transected. Accuracy was confirmed at the time of tissue harvest. Unlike the originally described method (Kim and Chung, 1992), paraspinous muscles and the adjacent articular process were not removed. The other animals received skin incisions alone.

4.2 Behavioral Testing

Sensory responsiveness after SNL was tested using a method that selectively identifies neuropathic hyperalgesia (Hogan et al., 2004). On 3 separate days in the second and third postoperative weeks after SNL, the plantar surface of each hind foot was touched 10 times with a 22g spinal anesthesia needle with pressure adequate to indent but not penetrate the skin. The frequency of a hyperalgesia-type response with sustained paw lifting, shaking or licking was determined. Control animals produce only a brief reflexive withdrawal.

4.3 Tissue preparation

DRGs were harvested during anesthesia with isoflurane (2–3% in oxygen). A laminectomy was performed up to the sixth thoracic level while the surgical field was perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, in mM: NaCl 128, KCl 3.5, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2.3, NaH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 24.0, glucose 11.0) bubbled by 5% CO2 and 95% O2 to maintain a pH of 7.35. The fourth and fifth lumbar DRGs and attached dorsal roots were removed and the connective tissue capsule dissected away from the ganglia under 20x magnification. Ganglia were transferred to a glass-bottomed recording chamber and perfused with 35°C aCSF. The proximal cut end of dorsal roots was placed on a pair of platinum wire stimulating electrodes. DRG neurons were viewed using an upright microscope equipped with differential interference contrast optics and infrared illumination. Neuronal soma diameter was determined with the focal plane adjusted to reveal the maximum somatic area, which was measured using a calibrated video image.

4.4 Electrophysiological Recording

Intracellular recordings were performed with microelectrodes fashioned from borosilicate glass (1mmOD, 0.5mmID, with Omega fiber – FHC Bowdoinham, USA) using a programmable micropipette puller (P-97, Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA). Microelectrode resistances were 80–120 MΩ when filled with 2M potassium acetate. Neurons were predominantly selected from the two outermost cell layers of the dorsal medial aspect of the DRG, and were impaled under direct vision by minimally indenting the membrane and then applying an oscillating current to the microelectrode. Data were acquired after stable recordings were achieved, typically within 5min of puncture. Membrane potential was recorded using an active bridge amplifier (Axoclamp 2B, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), except in protocols requiring simultaneous current injection through the electrode, for which we used discontinuous current clamp recording mode. This allows accurate recording of membrane voltage during the passing of current, although the noise level is increased compared to bridge mode. During discontinuous mode recording, the frequency of switching from current injection to recording was 2kHz, and full settling of the electrode charge was confirmed. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz (discontinuous mode) and 10kHz (bridge mode), and then digitized at 10kHz (discontinuous mode) or 40 kHz (bridge mode; Digidata 1322A and Axograph 4.9, Axon Instruments) for data acquisition and analysis. Somatic APs were elicited either by natural conduction from the site of dorsal root stimulation with square-wave pulses of up to 90mA lasting 0.06mS, or by direct membrane depolarization with current injection through the recording electrode. Ih was measured in voltage clamp using single-electrode discontinuous clamp mode, with a switching frequency of 1kHz.

Criteria for inclusion of data were a RMP negative to –50mV, and an AP amplitude greater than 40mV. Together, these excluded approximately 6% of recordings. AP measures (Fig. 2) were obtained from single traces after consistency of dimensions was confirmed by comparison to 10 sequential APs. Determinations of AP and AHP dimensions and the area under the curve for the AHP were performed digitally. Input resistance was calculated from the membrane potential shift generated by a 100ms injection of a hyperpolarizing current through the recording electrode, using a current amplitude (0.2–0.5nA) that failed to show any time-dependent rectification (“sag”) (Villiere and McLachlan, 1996). Sag in response to hyperpolarization is predominantly attributable to Ih (Scroggs et al., 1994). This was quantified as the fractional return from the peak hyperpolarized membrane potential back towards RMP during injection of a 1.2nA hyperpolarization current for 100ms. Rheobase was determined as the minimum current able to elicit an AP during incremental depolarizing current injection of 0.5–10nA for 100mS. The pattern of impulse generation was determined during depolarizing current steps beyond rheobase, at which neurons either continued to produce single APs or fired repetitively. The influence of ZD7288 upon AP firing pattern was measured at a depolarizing voltage that first produced a drug-induced difference in the number of APs generated. This measure is a sensitive indicator of drug effect but cannot be used to compare inherent excitability between groups (such as uninjured neurons versus SNL neurons) at baseline conditions due to the highly variable number of APs that might be present at the depolarization level at which ZD7288 first has an effect.

The following frequency was determined by presenting trains of 20 axonal stimuli with 3s intervals between trains, each train having progressively shorter interstimulus intervals. The maximum frequency of stimulation (1/interstimulus interval) at which each stimulus in the train produced a full somatic AP was considered the somatic following frequency.

Neurons were classified by the method of Villiere and McLachlan (Villiere and McLachlan, 1996). Conduction velocity (CV) was measured by dividing the distance between stimulation and recording sites by the conduction latency. Neurons with dorsal root CV<1.5m/S were considered C-type, neurons with CV>15m/S were considered Aα/β-type, and neurons with CV>1.5m/S but CV<10m/S were considered Aδ-type. For neurons with CV between 10 and 15m/S, long AP duration was used to categorize the cells as Aδ-types (Villiere and McLachlan, 1996). Stable recordings in C-type neurons are articularly challenging to acquire, so this group is necessarily smaller in number, and data were inadequate to evaluate following frequency.

4.5 Agents

ZD7288 (40μM, Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) was dissolved in bath solution. This was delivered by a microperfusion technique from a pipette with a 4μ diameter tip that was positioned 100μm from the impaled neuron, and ejected continuously by pressure applied to the back end of the pipette (Picospritzer II, General Valve Corp, Fairfield, NJ). Preliminary experiments in which cell depolarization was measured during microperfusion application of solutions of various K+ concentrations indicated an effective 4-fold dilution of pipette solution into the bath at the cell membrane, so the ZD7288 concentration was approximately 10μM at the cell surface. Preliminary experiments showed a full onset of action within 3min.

4.6 Statistical analysis

Data is grouped by neuron type according to CV categories. The “n” for each group indicates the number of recorded neurons, which were obtained from between 5 and 11 different animals for each group of control neurons and from 4 animals for each group of SNL neurons. Data are expressed as means ± SD. The effect of ZD7288 was evaluated using paired Student’s t-test to identify significant drug effects in the context of natural variability between neurons under baseline conditions. Significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant No. NS-42150 (QH) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdulla FA, Smith PA. Axotomy- and autotomy-induced changes in Ca2+ and K+ channel currents of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;85:644–58. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccei ML, Kocsis JD. Voltage-gated calcium currents in axotomized adult rat cutaneous afferent neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:2227–38. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch BD, Kocsis JD, Di Gregorio F, Bhisitkul RB, Waxman SG. A voltage- and time-dependent rectification in rat dorsal spinal root axons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1991;66:719–28. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR, Slayman CL. KCl leakage from microelectrodes and its impact on the membrane parameters of a nonexcitable cell. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1983;72:223–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01870589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BoSmith RE, Briggs I, Sturgess NC. Inhibitory actions of ZENECA ZD7288 on whole-cell hyperpolarization activated inward current (If) in guinea-pig dissociated sinoatrial node cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:343–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Shigemoto R, Mercer JN, Surmeier DJ. HCN2 and HCN1 channels govern the regularity of autonomous pacemaking and synaptic resetting in globus pallidus neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9921–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2162-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplan SR, Guo HQ, Lee DH, Luo L, Liu C, Kuei C, Velumian AA, Butler MP, Brown SM, Dubin AE. Neuronal hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels drive neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1169–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01169.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Castillo PE. Assessing the role of Ih channels in synaptic transmission and mossy fiber LTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9538–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142213199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas J, Harper AA, Trequattrini C, Adams DJ. Passive and active membrane properties of isolated rat intracardiac neurons: regulation by H- and M-currents. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1890–902. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Waxman SG. Sodium channels and the molecular pathophysiology of pain. Progress in Brain Research. 2000;129:3–19. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)29002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle C, Eisenach JC. Peripheral block of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) reduces mechanical allodynia in animal models of postoperative and neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:243–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan TN, Stephans K, Ramirez AN, Glazebrook PA, Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Differential distribution and function of hyperpolarization-activated channels in sensory neurons and mechanosensitive fibers. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3335–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5156-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everill B, Kocsis JD. Reduction in potassium currents in identified cutaneous afferent dorsal root ganglion neurons after axotomy. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:700–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Fricker D, Brager DH, Chen X, Lu HC, Chitwood RA, Johnston D. Activity-dependent decrease of excitability in rat hippocampal neurons through increases in I(h) Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1542–51. doi: 10.1038/nn1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A, Lirk P, Stucky C, Abram SE, Hogan QH. Painful nerve injury decreases resting cytosolic calcium concentrations in sensory neurons of rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1217–25. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A, Rigaud M, Hogan QH. Painful nerve injury shortens the intracellular Ca2+ signal in axotomized sensory neurons of rats. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:106–16. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267538.72900.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini S, DiFrancesco D. Action of the hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) blocker ZD 7288 in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Pflugers Arch. 1997;435:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s004240050488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghamari-Langroudi M, Bourque CW. Excitatory role of the hyperpolarization-activated inward current in phasic and tonic firing of rat supraoptic neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4855–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04855.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafe P, Quasthoff S, Grosskreutz J, Alzheimer C. Function of the hyperpolarization-activated inward rectification in nonmyelinated peripheral rat and human axons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:421–6. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Q, Sapunar D, Modric-Jednacak K, McCallum JB. Detection of neuropathic pain in a rat model of peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:476–87. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan QH, McCallum JB, Sarantopoulos C, Aason M, Mynlieff M, Kwok WM, Bosnjak ZJ. Painful neuropathy decreases membrane calcium current in mammalian primary afferent neurons. Pain. 2000;86:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram SL, Williams JT. Modulation of the hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) by cyclic nucleotides in guinea-pig primary afferent neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:97–106. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–63. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komagiri Y, Kitamura N. Effect of intracellular dialysis of ATP on the hyperpolarization-activated cation current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2115–22. doi: 10.1152/jn.00442.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkman PM, Kelly JS. Modulation of the hyperpolarisation-activated current, Ih, in rat facial motoneurones in vitro by ZD-7288. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:1058–72. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson SN. Phenotype and function of somatic primary afferent nociceptive neurones with C-, Adelta- or Aalpha/beta-fibres. Exp Physiol. 2002;87:239–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupica CR, Bell JA, Hoffman AF, Watson PL. Contribution of the hyperpolarization-activated current (I(h)) to membrane potential and GABA release in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:261–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Streit J, Lipp P, Luscher HR. Action potential propagation through embryonic dorsal root ganglion cells in culture. II. Decrease of conduction reliability during repetitive stimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:634–43. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, McBain CJ. The hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) and its contribution to pacemaker activity in rat CA1 hippocampal stratum oriens-alveus interneurones. J Physiol. 1996;497(Pt 1):119–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL. A voltage-clamp analysis of inward (anomalous) rectification in mouse spinal sensory ganglion neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1983;340:19–45. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum JB, Kwok WM, Mynlieff M, Bosnjak ZJ, Hogan QH. Loss of T-type calcium current in sensory neurons of rats with neuropathic pain. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:209–16. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200301000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum JB, Kwok WM, Sapunar D, Fuchs A, Hogan QH. Painful peripheral nerve injury decreases calcium current in axotomized sensory neurons. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:160–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercuri NB, Bonci A, Calabresi P, Stefani A, Bernardi G. Properties of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current Ih in rat midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:462–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZZ. Kappa-opioid receptor-mediated enhancement of the hyperpolarization-activated current (I(h)) through mobilization of intracellular calcium in rat nucleus raphe magnus. J Physiol. 2003;548:765–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.037622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC. Queer current and pacemaker: the hyperpolarization-activated cation current in neurons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1996;58:299–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg L, Mattick PA, Heath BM, Terrar DA. Modulation of the hyperpolarization-activated current (I(f)) by calcium and calmodulin in the guinea-pig sino-atrial node. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:497–504. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapunar D, Ljubkovic M, Lirk P, McCallum JB, Hogan QH. Distinct membrane effects of spinal nerve ligation on injured and adjacent dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:360–376. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantopoulos CD, McCallum JB, Rigaud M, Fuchs A, Kwok WM, Hogan QH. Opposing effects of spinal nerve ligation on calcium-activated potassium currents in axotomized and adjacent mammalian primary afferent neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1132:84–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh TO, Yamada M. A bradycardiac agent ZD7288 blocks the hyperpolarization-activated current (I(h)) in retinal rod photoreceptors. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1284–91. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt PC, Spain WJ, Crill WE. Effects of intracellular calcium chelation on voltage-dependent and calcium-dependent currents in cat neocortical neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;47:571–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90166-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Todorovic SM, Anderson EG, Fox AP. Variation in IH, IIR, and ILEAK between acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons of different size. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:271–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoney SD., Jr Unequal branch point filtering action in different types of dorsal root ganglion neurons of frogs. Neuroscience Letters. 1985;59:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takigawa T, Alzheimer C, Quasthoff S, Grafe P. A special blocker reveals the presence and function of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current IH in peripheral mammalian nerve fibres. Neuroscience. 1998;82:631–4. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Wu N, Hsaio CF, Turman J, Jr, Chandler SH. Development of inward rectification and control of membrane excitability in mesencephalic v neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1288–98. doi: 10.1152/jn.00850.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu H, Deng L, Sun Q, Yao L, Han JS, Wan Y. Hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels: roles in the differential electrophysiological properties of rat primary afferent neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:713–22. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyev DV, Shan Q, Lee Y, Mayer SC, Bowlby MR, Strassle BW, Kaftan EJ, Rogers KE, Dunlop J. Direct inhibition of Ih by analgesic loperamide in rat DRG neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:3713–21. doi: 10.1152/jn.00841.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villiere V, McLachlan EM. Electrophysiological properties of neurons in intact rat dorsal root ganglia classified by conduction velocity and action potential duration. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:1924–41. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi J, Sumino R. Inhibition of a hyperpolarization-activated current by clonidine in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:1094–104. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Donnelly DF, Ma C, LaMotte RH. Upregulation of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2069–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02069.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JH, Walters ET, Song XJ. Dissociation of dorsal root ganglion neurons induces hyperexcitability that is maintained by increased responsiveness to cAMP and cGMP. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:15–25. doi: 10.1152/jn.00559.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]