Abstract

Cancer patients undergoing treatment with systemic cancer chemotherapy drugs often have abnormal growth factor and cytokine profiles. Thus, serum levels of interleukin-8 (IL-8) are elevated in patients with malignant melanoma. In addition to IL-8, aggressive melanoma cells secrete, through its transcriptional regulator hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis and metastasis of human cancerous cells. Whether these responses are related to adenosine, a ubiquitous mediator expressed at high concentrations in cancer and implicated in numerous inflammatory processes, is not known and is the focus of this study. We have examined whether the DNA-damaging agents etoposide (VP-16) and doxorubicin can affect IL-8, VEGF, and HIF-1 expressions in human melanoma cancer cells. In particular, we have investigated whether these responses are related to the modulation of the adenosine receptor subtypes, namely, A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. We have demonstrated that A2B receptor blockade can impair IL-8 production, whereas blocking A3 receptors, it is possible to further decrease VEGF secretion in melanoma cells treated with VP-16 and doxorubicin. This understanding may present the possibility of using adenosine antagonists to reduce chemotherapy-induced inflammatory cytokine production and to improve the ability of chemotherapeutic drugs to block angiogenesis. Consequently, we conclude that adenosine receptor modulation may be useful for refining the use of chemotherapeutic drugs to treat human cancer more effectively.

Introduction

The incidence and mortality of cutaneous melanoma are still on the rise [1]. Overall, melanoma accounts for 1% to 3% of all malignant tumors and is increasing in incidence by 6% to 7% each year. The prognosis of metastatic melanoma remains poor. Once the metastatic phase develops, it is almost always fatal [2]. Different therapeutic approaches for metastatic melanoma have been evaluated, including chemotherapy and biologic therapies, both as single treatments and in combination [3]. To date, however, none have had a significant impact on survival. Systemic chemotherapy is still considered the mainstay of treatment of stage IV melanoma and is used largely with palliative intent [3]. Numerous chemotherapeutic agents have shown some activity in the treatment of malignant melanoma with dacarbazine (DTIC) being the most widely used [4]. DTIC is a nonclassical alkylating agent, generally considered the most active agent for treating malignant melanoma [4]. However, response rates for single-agent DTIC are disappointing [5,6].

A major obstacle to a successful treatment of metastatic melanoma is its notorious resistance to chemotherapy [7]. Chemoresistance is widely explored in cancer research, and many mechanisms have been described by which a tumor can evade cell killing in a variety of malignancies [8]. However, the mechanisms of chemoresistance of malignant melanoma are not established.

The aggressive nature of human melanomas is related to several abnormalities in growth factors, cytokines, and their receptor expression. For example, metastatic melanoma cells constitutively secrete the cytokine interleukin-8 (IL-8), whereas nonmetastatic cells produce low to negligible levels of IL-8 [9–11]. In fact, IL-8, originally discovered as a chemotactic factor for leukocytes, may play an important role in the progression of human melanomas [10]. Serum levels of IL-8 are elevated in patients with malignant melanoma [12], and several studies have demonstrated that the expression levels of this interleukin correlate with disease progression in human melanomas in vivo [12–16]. In addition to IL-8, aggressive melanoma cells secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis and metastasis of human cancerous cells [17]. Cytotoxic therapy, including radiotherapy, and other stress conditions such as hypoxia are known to induce IL-8 and VEGF release by tumor cells [18,19]. In particular, hypoxic induction of VEGF is mediated by the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), which plays a key role in regulating the adaptation of tumors to hypoxia [20]. HIF-1 is a heterodimer composed of an inducibly expressed HIF-1α subunit and a constitutively expressed HIF-1β subunit. A growing body of evidence indicates that HIF-1 contributes to tumor progression and metastasis [20,21]. HIF-1 is a potent activator of angiogenesis and invasion through its up-regulation of target genes critical for these functions [20]. Therefore, because HIF-1α expression and activity seem central to tumor growth and progression, HIF-1 inhibition becomes an appropriate anticancer target [20].

Adenosine is a ubiquitous mediator implicated in numerous inflammatory processes [22]. Accumulating evidence suggests that adenosine-mediated pathways are involved in cutaneous inflammation and epithelial cell stress responses. Most adenosine effects are mediated by its interaction with four seven-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor, namely, A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 [23]. Recently, it has been reported that epithelial cells release adenosine in response to various stimuli, including adenosine receptor agonists [24]. Moreover, we have demonstrated that, in addition to producing adenosine, melanoma cell lines also express functional adenosine receptors [25,26]. In particular, activation of A2B receptor leads to the production and release of calcium, VEGF, and IL-8 [27–29], whereas A3 receptor leads to the production and release of calcium, VEGF, and angiopoietin-2 [30–35]. Recently, we have demonstrated that A3 receptor induces a prosurvival signal in tumor cells [36]. Furthermore, A3 receptor stimulation increases the levels of HIF-1α in hypoxic tumor cells [28,31,33].

Here, we investigate whether two chemotherapeutic drugs, etoposide (VP-16) and doxorubicin, modulate IL-8 and VEGF production in human melanoma A375 cells. In particular, because adenosine is able to modulate HIF-1, VEGF, and IL-8 in cancer cells, we analyze the influence of the adenosinergic signaling on the chemotherapeutic drug effects in human melanoma cells.

We found, for the first time, that A2B receptor blockade can modulate IL-8 production, whereas blocking A3 receptors, it is possible to further decrease VEGF reduction due to VP-16 and doxorubicin in melanoma cells.We thus conclude that adenosine receptor modulation may be useful with chemotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of malignant melanoma.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Reagents, and Antibodies

A375 human melanoma cells were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection, LGC Standards s.r.l., Milano, Italy. Tissue culture media and growth supplements were obtained from Cambrex (Bergamo, Italy). Anti-adenosine A2B and anti-adenosine A3 receptor polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) were from Alpha Diagnostic (DBA, Milano, Italy). Human anti-HIF-1α and human anti-HIF-1β monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Milano, Italy). U0126 (inhibitor of MEK-1 and MEK-2), SB 202190 (inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)), human anti-ACTIVE MAPK and human anti-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2) pAbs were from Promega (Milano, Italy). SH-5 (inhibitor of Akt) was from Vinci-Biochem (Florence, Italy). [3H]-Thymidine was from Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Milano, Italy). Anti-human phospho-p38, anti-human p38 MAP Kinase, anti-human phospho-Akt and anti-human Akt antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Milano, Italy). 4-(2-[7-Amino-2-[furyl][1,2,4,] triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol was obtained from Tocris Cookson Ltd (Bristol, UK). N-Benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-2-[5-(2,6-dioxo-1, 3-dipropyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purin-8-yl)-1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yloxy]-acetamide (MRE 2029F20) and 5N-(4-methoxyphenyl-carbamoyl)amino-8-propyl-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3e]1,2,4-triazolo[1,5c] pyrimidine (MRE 3008F20) were synthesized by Prof. Pier Giovanni Baraldi (Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Ferrara, Italy) [37]. Adenosine A2B and A3 receptors and HIF-1α small interfering RNA (siRNA) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, D.B.A. ITALIA s.r.l., Milano, Italy. RNAiFect Transfection Kit was from Qiagen (Milano, Italy). Unless otherwise noted, all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (Milano, Italy).

Cell Culture

A375 human melanoma cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml), and L-glutamine (2 mM) at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air.

Establishment of Hypoxic Culture Condition

For hypoxic conditions, cells were placed for the indicated times in a modular incubator chamber and flushed with a gas mixture containing 1% O2, 5% CO2, and balance N2 (MiniGalaxy; RSBiotech, Irvine, Scotland). Maintenance of the desired O2 concentration (1%) was constantly monitored during incubation using a microprocessor-based oxygen controller. The cells gassed under hypoxic conditions can reach the 1% oxygen concentration in ∼90 minutes [38].

Cytotoxic Treatment of Cancer Cells

Exponentially growing cells (70%–80% confluence) in complete medium were treated with different concentrations of cytotoxic drugs, followed by exposure to hypoxia (1% O2) for different indicated time intervals.

MTS Assay

The MTS assay was performed to determine cell viability and proliferation according to the manufacturer's protocol from the Cell Titer 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay as previously described [32]. Briefly, 105 cells were plated in 24-multiwell plates; 500 µl of complete medium was added to each well with different concentrations of cytotoxic drugs. The cells were then incubated for 24 hours. At the end of the incubation period,MTS solution was added to each well. The optical density of each well was read on a spectrophotometer at 570 nm. For each experiment, four individual wells of each drug concentration were prepared. Each experiment was repeated three times.

[3H]-Thymidine Incorporation: Cell Proliferation Test

Cells were seeded in fresh medium with 1 µCi/ml of [3H]-thymidine in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10%fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml), and l-glutamine (2 mM). After 24 hours of labeling, cells were trypsinized, dispensed in four wells of a 96-well plate, and filtered through Whatman GF/C glass-fiber filters using a Micro-Mate 196 Cell Harvester (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences,Milano, Italy). The filter-bound radioactivity was counted on Top Count Microplate Scintillation Counter (efficiency, 57%) with Micro-Scint 20 (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

A375 adherent cells were trypsinized, mixed with floating cells, washed with PBS, and permeabilized in 70% (vol/vol) ethanol-PBS solution at 4°C for at least 24 hours. The cells were washed with PBS, and the DNA was stained with a PBS solution, containing 20 µg/ml propidium iodide and 100 µg/ml RNAse, at room temperature for 30 minutes. Cells were analyzed with an EPICS XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL), and the content of DNA was evaluated by the EXPO-32 program (Becton Dickinson Italia Spa, Milano, Italy). Cell distribution among cell cycle phases and the percentage of apoptotic cells were evaluated as previously described [30]. Briefly, the cell cycle distribution is shown as the percentage of cells containing 2n (G0/G1 phases), 4n (G2 and M phases), and 4n > x > 2n DNA amount (S phase) judged by propidium iodide staining. The apoptotic population is the percentage of cells with DNA content lower than 2n.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole-cell lysates, prepared as described previously [32], were resolved on a 10% SDS gel and transferred onto the nitrocellulose membrane. Western blot analyses were performed as previously described [31] with anti-HIF-1α (1:250 dilution) and anti-HIF-1β antibodies (1:1000 dilution) in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS/0.1% Tween-20 overnight at 4°C. Aliquots of total protein sample (50 µg) were analyzed using antibodies specific for phosphorylated (Thr183/Tyr185) or total p44/p42 MAPK (1:5000 dilution), phosphorylated (Thr180/Tyr182) or total p38 MAPK (1:1000 dilution), and for phosphorylated or total Akt (Ser473; 1:1000 dilution). The protein concentration was determined using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, TEMA ricerca S.r.l., Bologna, Italy). Membranes were washed and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies against mouse and rabbit immunoglobulinG(1:2000 dilution). Specific reactions were revealed with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Amersham, Corp, Arlington Heights, IL). The membranes were then stripped and reprobed with antitubulin antibodies (1:250) to ensure equal protein loading.

Densitometry Analysis

The intensity of each band in the immunoblot assay was quantified using molecular analyst/PC densitometry software (Bio-Rad, Milano, Italy). Mean densitometry data from independent experiments were normalized to results in cells in the control. Data were presented as the mean ± SE.

Treatment of Cells with siRNA

A375 cells were plated in six-well plates and grown to 50% to 70% confluence before transfection. Transfection of siRNA was performed at a concentration of 100 nM using RNAiFect Transfection Kit. Cells were cultured in complete medium, and at 48 hours, total proteins were isolated for Western blot analysis of A2B, A3, and HIF-1α protein. A nonspecific random control siRNA was used under identical conditions [32].

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The levels of VEGF and IL-8 protein secreted by the cells in the medium were determined by a VEGF and an IL-8 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, DBA,Milano, Italy). In brief, subconfluent cells were changed into fresh medium in the presence of solvent or various concentrations of drugs in hypoxia. The medium was collected, and VEGF and IL-8 protein concentrations were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions. The results were normalized to the number of cells per plate. Data were presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Statistical Analysis

All values in the figures and text are expressed as mean ± SE of n observations (with n ≥ 3). Data sets were examined by Student's t test or by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett test (when required). P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cytotoxic Activity of Chemotherapeutic Drugs

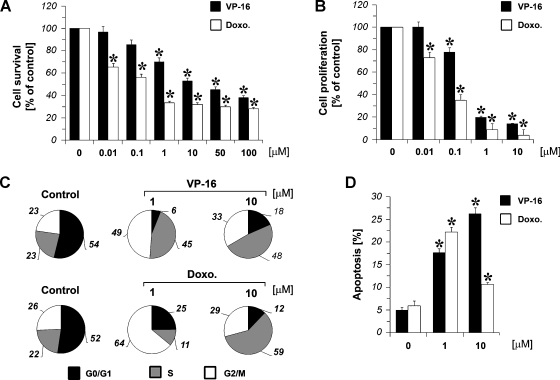

All the experiments were performed in hypoxic conditions at 1% O2. An assessment of growth effects in A375 cells subjected to VP-16 and doxorubicin for 24 hours was performed by using the MTS assay that measured viable cell mass. As shown in Figure 1A, A375 melanoma cells were sensitive to the growth-inhibitory effects of both the DNA-damaging agents tested. A375 cells were treated with VP-16 and doxorubicin (0.01–100 µM). The cell viability was reduced up to 40 ± 4% and 30 ± 4% for VP-16 and doxorubicin, respectively (control set at 100%, n = 4). A number of different mechanisms, such as 1) impaired DNA synthesis, 2) perturbations in cell cycle progression, and 3) induction of apoptosis, could contribute to the reduction in viable cell mass seen after treatment with cytotoxic agents. DNA synthesis was markedly inhibited in melanoma cells treated with increasing concentrations of chemotherapeutics (0.01–10 µM). This inhibition was dose-dependent as determined by tritiated thymidine incorporation after 24 hours of treatment (Figure 1B). The cytometry investigation showed a clear arrest in the G2/M and S cell cycle phases of melanoma cells treated with VP-16, 1 and 10 µM, respectively, to control cells. In particular, low concentration of VP-16 arrested cells in the G2/M phase, whereas higher doses of chemotherapeutic drug were needed to accumulate cell cultures in the S phase (Figure 1C). Similar results were obtained when melanoma cells were treated for 24 hours with doxorubicin 1 to 10 µM (Figure 1C). Furthermore, to evaluate the induction of apoptosis by chemotherapeutic drugs, A375 cells were incubated with or without VP-16 and doxorubicin (1–10 µM) for 24 hours. As shownin Figure 1D, both the chemotherapeutic drugs tested were able to significantly induce apoptosis.

Figure 1.

Effect of chemotherapeutic drugs. (A) A375 cellswere treated with increasing concentrations (0.01–100 µM) of VP-16 or doxorubicin (Doxo.) for 24 hours under hypoxic conditions, and cell viability was assayed by an MTS test. MTS: the cell growth is expressed as a percentage of the optical densitymeasured on untreated cells (control, 100%). Ordinate reportsmeans of four different optical density quantifications with SE (vertical bar). During the experiment, cells treated with the solventDMSOserved as controls. (B) Antiproliferative activitymeasured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. A375 cells were treated with VP-16 or doxorubicin (Doxo.) at the indicated concentrations. [3H]-Thymidine incorporation is reported as percentage ofDNA-labeled recovered on drug vehicle-treated cells. Ordinate reportsmeans of four different [3H]-thymidine incorporation experiments with standard error (vertical bar). (C) DNA content analysis of A375 cells by flow cytometry. Figures show percentage cell number of cells in different cell cycle phases. Two representative experiments of A375 cells treated with VP-16, doxorubicin (Doxo.), and DMSO (control) are reported. (D) Apoptosis of A375 cells, by flow cytometry, after treatment with VP-16 or doxorubicin (Doxo.) at the indicated concentrations (percentage of subdiploid cells). *P < .01 compared with the control (untreated cells); analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test.

Modulation of IL-8 by VP-16 and Doxorubicin

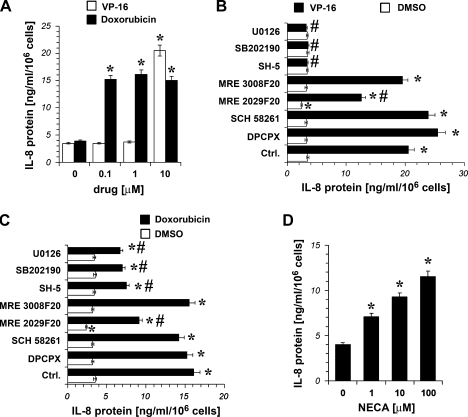

A375 cells were incubated with VP-16 and doxorubicin (0.1–10 µM), then IL-8 protein content was measured. As shown in Figure 2A, VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin 0.1 to 10 µM significantly increased the levels of IL-8 in A375 cells after 24 hours of treatment.

Figure 2.

Effect of chemotherapeutic drugs on IL-8 expression in hypoxic (1% O2) A375 cells. (A) IL-8 release into the culturemediumof A375 cells cultured for 24 hours in the absence (0) and in the presence of increasing concentrations of VP-16 and doxorubicin. *P < .01 compared with the control (DMSO-treated hypoxic cells); analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. (B and C) IL-8 release into the culture medium of A375 cells cultured for 24 hours in the absence and in the presence of 1 µM of U0126, SB 202190, SH-5, the A3 antagonist MRE 3008F20, the A2B antagonist MRE 2029F20, the A2A antagonist SCH 58261, and the A1 antagonist DPCPX 1 µM alone (DMSO) or in the presence of the chemotherapeutic drug VP-16 5 µM (VP-16; B) or in the presence of the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin 1 µM (C); the inhibitors and the antagonists were added 30 minutes before the chemotherapeutic drug, then the cells were exposed to hypoxia. Ctrl. indicates control and represents DMSO in empty bar and VP-16 or doxorubicin alone (filled bar) in panelsBand C, respectively. Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .05 compared with the control (DMSO-treated hypoxic cells). #P < .05 compared with the control (VP-16-treated cells in panel B; doxorubicin-treated cells in panel C); analysis was byANOVAfollowed byDunnett test. (D) Effect of the adenosine receptor agonist NECA (1, 10, and 100 µM) on IL-8 expression in hypoxic A375 cells after 24 hours of treatment. *P < .01 compared with the control (0; untreated hypoxic cells). Analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test.

To determine whether Akt and MAPK pathways were required for IL-8 increase induced by VP-16 and doxorubicin, A375 cells were pretreated for 30 minutes with SH-5, an Akt inhibitor, with SB 202190 and U0126, which are potent inhibitors of p38 MAPK and MEK1/2, respectively. Cells were then exposed to VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin 1 µM for 24 hours. As shown in Figure 2, B and C, SB 202190, U0126, and SH-5 1 µM were able to completely inhibit VP-16-induced increase of IL-8 protein expression, whereas they inhibited only partially the effect of doxorubicin.

Furthermore, to evaluate a potential role for adenosine receptors in the increase of IL-8 induced by VP-16 and doxorubicin, A375 cells were treated with the chemotherapeutic drugs in combination with 1 µM of adenosine receptor antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX; for A1), SCH 58261 (for A2A), MRE 2029F20 (for A2B), and MRE 3008F20 (for A3). The results indicate that only the A2B receptor antagonist MRE 2029F20 was able to significantly reduce IL-8 protein levels in hypoxic A375 cells. Furthermore, as expected, MRE 2029F20 partially blocked the increase in IL-8 induced by VP-16 and doxorubicin (Figure 2, B and C), suggesting that the A2B receptor induced a signal able to increase IL-8 protein. To confirm this finding, we stimulated A2B adenosine receptors in A375 cells with increasing concentrations of 5′-N-ethylcarboxamide-adenosine (NECA; 1–100 µM) for 24 hours.We found that this drug induced the secretion of IL-8 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2D). The relatively low potency of NECA agrees with previous reports of A2B receptor-mediated IL-8 production [28,39].

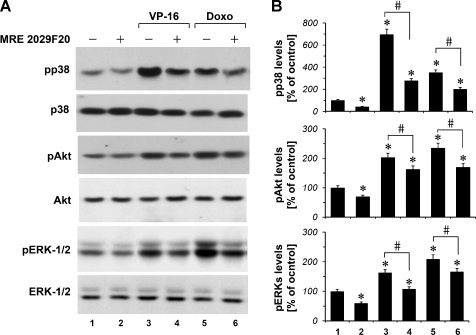

VP-16 and Doxorubicin Modulate Akt, p44/p42, and p38 MAPK Signaling Pathways

A375 cells were cultured in the absence and in the presence of VP-16 and doxorubicin for 6 hours. We found that exposure of melanoma cells to VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin 1 µM resulted in the increase of p38, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels (Figure 3, A and B). Furthermore, we observed that the A2B receptor antagonist MRE 2029F20 1 µM was able to attenuate the increase in p38, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels induced by VP-16 and doxorubicin. In particular, we found that the A2B receptor antagonist MRE 2029F20 1 µM, when used alone, reduces p38, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation basal levels in A375 cells (Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

p38, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in hypoxic (1% O2) A375 cells. (A) pp38, phospho-Akt, and pERK1/2 MAPK phosphoprotein levels under VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin (Doxo) 1 µM treatment in the absence and in the presence of the A2B adenosine receptor antagonist MRE 2029F20 1 µM. (B) Densitometric data, means from three independent experiments, were normalized to the results obtained in cells in the absence of drugs (control). Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .01 compared with the control. Analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. #P < .01 compared with cells treated with the chemotherapeutic alone; t test.

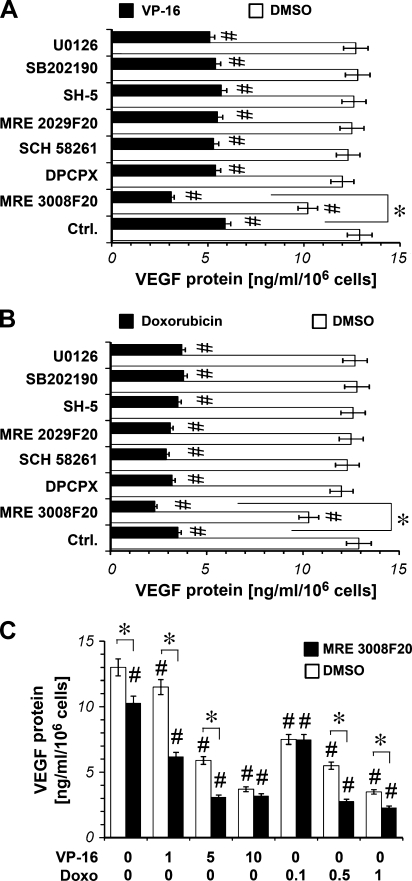

Modulation of VEGF by VP-16 and Doxorubicin

To investigate VEGF expression, we incubated A375 cells with VP-16 (5 µM) and doxorubicin (1 µM) and determined VEGF protein release. As shown in Figure 4A, VP-16 and doxorubicin significantly decreased the levels of VEGF after 24 hours of treatment.

Figure 4.

Effect of chemotherapeutic drugs on VEGF expression in hypoxic (1% O2) A375 cells. (A) VEGF release into the culture medium of A375 cells cultured for 48 hours in the absence and in the presence (1 µM) of U0126, SB 202190, SH-5, the A3 antagonist MRE 3008F20, the A2B antagonistMRE 2029F20, the A2A antagonist SCH 58261 and the A1 antagonist DPCPX alone (DMSO) or in the presence of the chemotherapeutic drug VP-16 5 µM (VP-16; A) or in the presence of the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin 1 µM (B); the inhibitors and the antagonists were added 30 minutes before the chemotherapeutic drug, then the cellswere exposed to hypoxia. Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .05 MRE 3008F20 plus chemotherapeutic drug-treated cells versus chemotherapeutic drug-treated cells: black filled bar indicates Ctrl.; analysis was by t test. #P < .05 compared with the control (DMSO-treated cells: empty bar indicates Ctrl.); analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. (C) VEGF release into the culture medium of A375 cells cultured for 48 hours in the presence of increasing concentrations of the chemotherapeutic drug VP-16 (1-5-10 µM) and doxorubicin (0.1-0.5-1 µM) in the absence and in the presence of the A3 antagonist MRE 3008F20 1 µM, which was added 30 minutes before the chemotherapeutic drug. Then the cells were exposed to hypoxia. *P < .05: MRE 3008F20-treated cells versusDMSO-treated cells; analysiswas by t test. #P < .05 compared with the control (DMSO-treated hypoxic cells: empty bar indicates Ctrl.); analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test.

To determine whether Akt and MAPK pathways were required for VEGF decrease induced by VP-16 and doxorubicin, A375 cells were pretreated with 1 µM SH-5, SB 202190, or U0126. Cells were then exposed to VP-16 5 µM and doxorubicin 1 µM for 24 hours. As shown in Figure 4, A and B, differently from what we have observed for IL-8-secretion, SB 202190, U0126, and SH-5 were not able to block VP-16- and doxorubicin-induced decrease of VEGF protein expression.

To evaluate a potential role for adenosine receptors in the modulation of VEGF protein levels by VP-16 and doxorubicin, A375 cells were treated with the chemotherapeutic drugs in combination with 1 µM DPCPX, SCH 58261, MRE 2029F20, andMRE 3008F20. The results indicate that the A3 receptor antagonist MRE 3008F20 was able to further impair VEGF production already decreased by VP-16 and doxorubicin in A375 cells (Figure 4, A and B). Moreover, the A3 receptor antagonist MRE 3008F20, also when used alone, was able to significantly reduce VEGF protein in A375 cells. Furthermore, we studied the effect of MRE 3008F20 1 µM in combination with different concentrations of VP-16 (1, 5, and 10 µM) and doxorubicin (0.1, 0.5, and 1 µM) on VEGF production.We found that MRE 3008F20 was able to further reduce VEGF levels already decreased by VP-16 1 to 5 µM and by doxorubicin 0.5 to 1 µM (Figure 4C).

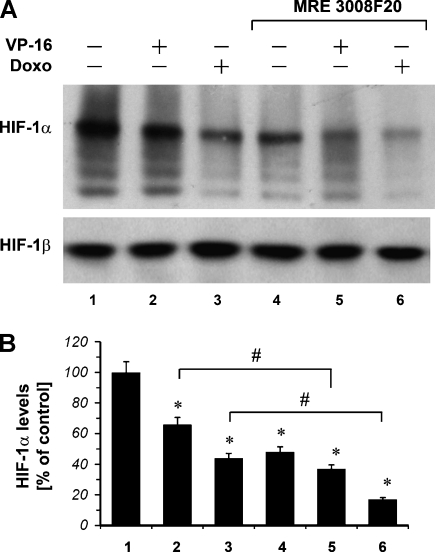

VP-16 and Doxorubicin Modulate the Expression of HIF-1α Protein

The levels of HIF-1α and HIF-1β protein in hypoxic A375 cells on drug treatment were investigated by Western blot analysis (Figure 5). HIF-1α protein expression was increased in a time-dependent manner [31]. In particular, HIF-1α protein expression was detected after 4 hours of exposure to hypoxia, and VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin 1 µM strongly inhibited HIF-1α protein expression (lanes 2 and 3). The observed down-regulation of HIF-1α protein expression by the chemotherapeutic drugs was specific because no alterations were detected in the levels of the HIF-1β protein. Because MRE 3008F20, when used alone, was able to significantly reduce HIF-1α protein in A375 cells (Figure 5, lane 4), we have evaluated whether the A3 receptor antagonist MRE 3008F20 was able to modulate HIF-1α protein when used in combination with the chemotherapeutic drugs. A375 cells were treated for 4 hours in hypoxia with VP-16 10 µM or doxorubicin 1 µM alone and in combination with MRE 3008F20 1 µM. As shown in Figure 5 (lanes 5 and 6), we found that MRE 3008F20 further increased the effect of chemotherapeutic drugs by further decreasing HIF-1α protein accumulation.

Figure 5.

(A) Western blot analysis using an anti-HIF-1α mAb of protein extracts from A375 hypoxic cells (1% O2) under VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin (Doxo) 1 µM treatment (4 hours) in the absence and in the presence of the A3 adenosine receptor antagonist MRE 3008F20 1 µM. HIF-1β shows equal protein loading. (B) The mean densitometric data from three independent experiments were normalized to the results obtained in cells in the absence of drugs (control). Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .01 compared with control without chemotherapeutic treatment; analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. #P < .01 compared with the cells exposed to chemotherapeutic alone (2 vs 5 and 3 vs 6 for VP-16 and doxorubicin, respectively). Analysis was by t test.

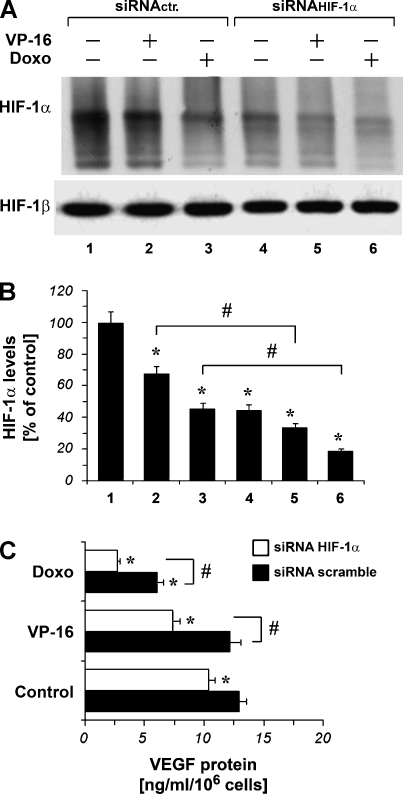

Role of HIF-1α

To investigate a possible role for the HIF-1α subunit in the chemotherapeutic-induced VEGF inhibition, we have performed a series of experiments in the presence of siRNAHIF-1α. HIF-1α protein level was reduced with siRNA at 72 hours after siRNAHIF-1α transfection (Figure 6, A and B, lane 4 vs lane 1). The results show that when HIF-1α protein level was reduced by siRNAHIF-1α transfection, VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin 1 µM further decreased HIF-1α protein content in A375 cells. Furthermore, siRNAHIF-1α transfection was able to decrease VEGF protein levels (Figure 6C). In particular, when HIF-1α protein level was reduced by siRNAHIF-1α transfection, VP-16 1 µM and doxorubicin 0.5 µM decreased VEGF secretion levels to a major extent (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

(A) Western blot analysis using an anti-HIF-1α mAb of protein extracts from A375 cells transfected with scramble ribonucleotides (siRNActr.) or siRNAHIF-1α for 72 hours and cultured with VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin (Doxo) 1 µM for 4 hours. HIF-1β shows equal protein loading. (B) The means of densitometry data from independent experiments were normalized to the results obtained in cells transfected with siRNActr. Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .01 compared with the siRNActr. without chemotherapeutic drug treatment. Analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. #P < .01 cells treated with siRNAHIF-1α compared with cells treated with siRNActr (2 vs 5 for VP-16; 3 vs 6 for doxorubicin). Analysis was by t test. (C) VEGF release into the culture medium of A375 cells transfected with scramble siRNA or with siRNAHIF-1α for 48 hours and then cultured for 24 hours in hypoxia in the absence (Control) and in the presence of VP-16 1 µM and doxorubicin (Doxo) 0.5 µM. Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .01 compared with the Control-siRNA-scramble-transfected cells (black filled bar); analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. #P < .01 siRNAHIF-1α versus siRNA scramble; analysis by t test.

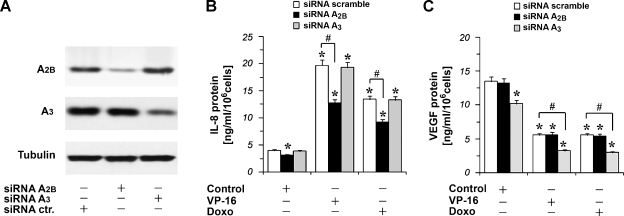

A2B and A3 Receptors Gene Silencing

To demonstrate more conclusively a role for A2B or A3 receptors in the responses being measured, we tried to knock down A2B and A3 receptors' expression in hypoxic A375 melanoma cells using siRNA, leading to a transient knockdown of the A2B and A3 receptor genes. A375 cells were transfected with nonspecific random control ribonucleotides (siRNA scramble) or with siRNA that target A2B (siRNAA2B) or A3 receptor messenger RNA (siRNAA3) for degradation. After transfection, the cells were cultured for 48 hours in complete medium, and then total proteins were isolated for Western blot analysis of A2B and A3 receptor protein expressions. As expected, A2B and A3 receptors protein expressions were strongly reduced in siRNAA2B- and siRNAA3-treated cells, respectively (Figure 7A). To confirm the specificity of the siRNAA3-mediated silencing of A3 receptor, we investigated the expression of A2B receptor protein in siRNAA3-treated cells (Figure 7A). Figure 7A demonstrates that treatment of A375 cells with siRNAA3 reduced the expression of A3 protein but had no effect on the expression of A2B receptor. Similar results were obtained when A375 cells transfected with siRNAA2B were analyzed for the expression of the A3 receptor. Therefore, at 48 hours from the siRNAA2B and siRNAA3 transfection, A375 cells were exposed to VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin 1 µM for 24 hours in hypoxia. Then, IL-8 protein levels were measured. We found that the inhibition of A2B receptor expression was able to reduce chemotherapeutic-induced IL-8 accumulation, whereas the inhibition of A3 receptor expression with siRNAA3 did not modify chemotherapeutic-induced IL-8 accumulation (Figure 7B). In particular, the silencing of the A2B receptor by using siRNAA2B alone was able to significantly reduce basal IL-8 protein secretion in hypoxic A375 cells (Figure 7B). Furthermore, A375 cells were transfected with siRNAA2B and siRNAA3 and exposed to VP-16 5 µM and doxorubicin 1 µM for 24 hours in hypoxia to evaluate VEGF levels. No effect in VEGF inhibition induced by the chemotherapeutic drugs was observed after the inhibition of A2B receptor expression. On the contrary, the inhibition of A3 receptor expression potentiates the reduction of VEGF secretion induced by the chemotherapeutic drugs (Figure 7C). In particular, the silencing of the A3 receptor by using siRNAA3 alone was able to significantly reduce VEGF protein in A375 cells (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

A2B and A3 receptor expression silencing by siRNA transfection in hypoxic A375 cells (1% O2). (A) Western blot analysis using an anti-A2B and an anti-A3 receptor pAb of protein extracts from A375 cells transfected with scramble (control siRNA) ribonucleotides or with siRNAA2B or siRNAA3 and cultured for 48 hours. Tubulin shows equal protein loading. (B) IL-8 release into the culture medium of A375 cells transfected for 48 hours with scramble ribonucleotides or with siRNAA2B or siRNAA3 and then cultured for 24 hours in hypoxia (1% O2) in the absence (Control) and in the presence of VP-16 10 µM and doxorubicin (Doxo) 1 µM. Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .01 compared with the control siRNA-scramble transfected cells without chemotherapeutic drug treatment; analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. #P < .01 siRNAA2B-transfected cells versus siRNA-scramble-transfected cells; analysis was by t test. (C) VEGF release into the culture medium of A375 cells transfected for 48 hours with scramble ribonucleotides or with siRNAA2B or siRNAA3 and then cultured for 24 hours in hypoxia in the absence (Control) and in the presence of VP-16 5 µM and doxorubicin (Doxo) 1 µM. Plots are mean ± SE values (n = 3). *P < .01 compared with control siRNA-scramble-transfected cells without chemotherapeutic drug treatment. Analysis was by ANOVA followed by Dunnett test. #P < .01 siRNAA3-transfected cells versus siRNA-scramble-transfected cells exposed to VP-16 or doxorubicin; analysis was by t test.

Discussion

New treatments are urgently needed for the therapy for metastatic melanoma, and much effort is being devoted to the development of genetic and immune therapies, but the widespread availability of these remains a distant prospect. In the meantime, chemotherapy will remain the treatment of choice, and strategies to overcome resistance offer a more immediate possibility for improving the lot of these patients.

This study was undertaken to examine whether two chemotherapeutic drugs, VP-16 and doxorubicin, modulate IL-8 and VEGF production in human melanoma A375 cells. In particular, because adenosine was able to modulate HIF-1, VEGF, and IL-8 in cancer cells, we analyzed the influence of the adenosinergic signaling on the chemotherapeutic drug effects in human melanoma cells.

The aims of this study were as follows:

to investigate the effect of two drugs used in chemotherapy on cell vitality and on cytokine release induced in melanoma cells under hypoxic conditions;

to define a molecular signaling of the cancer cell response to these drugs; and

to investigate the putative role of the adenosinergic system in these processes.

We demonstrated that human melanoma cells produce IL-8 and VEGF. In particular, we found that treatment of melanoma cells with the DNA-damaging drugs VP-16 and doxorubicin resulted in the upregulation of the proangiogenic cytokine IL-8 (Figure 2). These results are in accord with data indicating that in addition to their known cytotoxic effects, chemotherapeutic agents can trigger cytokine production in a variety of cell types in vitro [40,41]. Moreover, our data indicate that the DNA-damaging drugs VP-16 and doxorubicin inhibit VEGF expression (Figure 4) through the inhibition of HIF-1 (Figure 5).

A further objective of these studies was to assess whether the adenosinergic signaling, through its adenosine receptor subtypes, could modulate cytokine production induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Using the human A375 melanoma cell line that expresses each of the four adenosine receptor subtypes [25], these studies demonstrated that the A2B receptor blockade can modulate IL-8 production, whereas blocking A3 receptors, it is possible to further decrease VEGF reduction because of VP-16 and doxorubicin. In this work, we have demonstrated that the inhibition of the A2B receptor results in the reduction of IL-8 production, whereas inhibition of A3 results in the reduction of VEGF. According to these results, it has been previously demonstrated that stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors increased synthesis and secretion of IL-8, whereas A3 receptors are responsible of the increase of VEGF [27,28]. We hypothesize that the different effects of A2B and A3 adenosine receptors on the synthesis of angiogenic factors may imply their coupling to different G proteins.

The mechanism of how A2B adenosine receptor could decrease chemotherapy-induced cytokine production was also examined and was found to be dependent on the activation of MAPK. The current findings describe a putative mechanism by which this G protein-coupled receptor can decrease the cytokine-producing effects of chemotherapeutic agents in human melanoma.

Hypoxic cancer cells are resistant to chemotherapeutic treatment, leading to the selection of cells with a more malignant phenotype. HIF-1 has been shown to be responsible for an adaptive response of cells to hypoxia. If VP-16 would influence its activity under hypoxia, this could lead to changes in cell survival. To investigate this possibility, we measured HIF-1α protein level. The results indicate that hypoxia did increase HIF-1α protein level in melanoma cells, and this effect was influenced by VP-16 (Figure 5).

Dacarbazine remains the reference standard treatment of metastatic melanoma, but only a minority of patients obtains long-lasting responses [7]. Polychemotherapy regimens have been reported to produce various response rates. Treatment with VP-16 is more common in lung cancer, leukemia, and testicular tumors and has been used in polychemotherapy regimens combined with cisplatin for the treatment of melanoma brain metastases, but the response rates remain less than 13% [42].

The significance of tumor cell-derived cytokine production in the therapeutic effectiveness or adverse effect profile of chemotherapeutic agents is unclear. However, significant levels of cytokines, including IL-8, tumor necrosis factor α, and others, can be found in patients undergoing chemotherapy for a variety of tumors [43,44]. It has been reported that overproduction of chemokines is a potential mechanism for melanoma cells to evade cell death and become resistant to chemotherapy. Strategies to inhibit IL-8 signaling may sensitize hypoxic tumor cells to conventional treatments.

These data may have a significant clinical relevance, justifying the combination of conventional chemotherapy with anti-IL-8 and/or anti-VEGF modalities, such as A2B or A3 adenosine receptor antagonists, for the treatment of malignant melanoma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Giuliano Marzola's work in editing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DPCPX

1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MRE 2029F20

N-benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl-2-[5-(2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purin-8-yl)-1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yloxy]-acetamide

- MRE 3008F20

5N-(4-methoxyphenyl-carbamoyl)amino-8-propyl-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3e]1,2,4-triazolo[1,5c] pyrimidine

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- siRNAA2B

small interfering RNA that targets A2B receptor messenger RNA

- siRNAA3

small interfering RNA that targets A3 receptor messenger RNA

- siRNAHIF-1α

siRNA targeting the transcription factor HIF-1α

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VP-16

etoposide

References

- 1.Howe HL, Wingo PA, Thun MJ, Ries LA, Rosenberg LA, Feigal EG, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer (1973 through 1998), featuring cancers with recent increasing trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:824–842. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallagher SJ, Thompson JF, Indsto J, Scurr LL, Lett M, Gao BF, Dunleavey R, Mann GJ, Kefford RF, Rizos H. p16INK4a expression and absence of activated B-RAF are independent predictors of chemosensitivity in melanoma tumors. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1231–1239. doi: 10.1593/neo.08702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker JC, Kampgen E, Brocker EB. Classical chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:503–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman PB, Einhorn LH, Meyers MH, Saxman S, Destro AN, Panageas KS, Begg CB, Agerwala SS, Schuchter LM, Ernstoff MS, et al. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of the Dartmouth regimen versus dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2745–2751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Middleton MR, Grob JJ, Aaronson N, Fierlbeck G, Tilgen W, Seiter S, Gore M, Aamdal S, Cebon J, Coates A, et al. Randomized phase III study of temozolomide versus dacarbazine in the treatment of patients with advanced metastatic malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:158–166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Middleton MR, Lorigan P, Owen J, Ashcroft L, Lee SM, Harper P, Thatcher N. A randomized phase III study comparing dacarbazine, BCNU, cisplatin and tamoxifen with dacarbazine and interferon in advanced melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1158–1162. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggermont AM, Kirkwood JM. Re-evaluating the role of dacarbazine in metastatic melanoma: what have we learned in 30 years? Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1825–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottesman MM. Mechanisms of cancer drug resistance. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:615–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schadendorf D, Moller A, Algermissen B, Worm M, Stichering M, Czarnetzki BM. IL-8 produced by human malignant melanoma cells in vitro is an essential autocrine growth factor. J Immunol. 1993;15:2667–2675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bar-Eli M. Role of interleukin-8 in tumor growth and metastasis of human melanoma. Pathobiology. 1999;67:12–18. doi: 10.1159/000028045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh RK, Gutman M, Radinsky R, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of interleukin 8 correlates with the metastatic potential of human melanoma cells in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3242–3247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ugurel S, Rappl G, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. Increased serum concentration of angiogenic factors in malignant patients correlates with tumor progression and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:577–583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh RK, Gutman M, Reich R, Bar-Eli M. Ultraviolet-B irradiation promotes tumorigenic and metastatic properties in primary cutaneous melanoma via induction of interleukin-8. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3669–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurnberg W, Tobias D, Otto F, Henz BM, Schadendorf D. Expression of interleukin-8 detected by in situ hybridization correlates with worse prognosis in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Pathol. 1999;189:546–551. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199912)189:4<546::AID-PATH487>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunz M, Goebeler M, Brocker EB, Gillitzer R. IL-8 mRNA expression in primary malignant melanoma mRNA in situ hybridization: sensitivity, specificity, and evaluation of data. J Pathol. 2000;192:413–415. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(200011)192:3<413::AID-PATH738>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luca M, Huang S, Gershenwald JE, Singh RK, Reich R, Bar-Eli M. Expression of interleukin-8 by human melanoma cells up-regulates MMP-2 activity and increases tumor growth and metastasis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1105–1113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rofstad EK, Halsor E. Vascular endothelial growth factor, interleukin 8, platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor promote angiogenesis and metastasis in human melanoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4932–4938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geng L, Donnelly E, McMahon G, Lin C, Sierra-Rivera E, Oshinka H, Hallahan DE. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling leads to reversal of tumor resistance to radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2413–2419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Büchler P, Reber HA, Tomlinson JS, Hankinson O, Kallifatidis G, Friess H, Herr I, Hines OJ. Transcriptional regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is crucial for invasion of pancreatic and liver cancer. Neoplasia. 2009;11:196–206. doi: 10.1593/neo.08734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fredholm BB. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haskó G, Pacher P. A2A receptors in inflammation and injury: lessons learned from transgenic animals. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:447–455. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merighi S, Varani K, Gessi S, Cattabriga E, Iannotta V, Ulouglu C, Leung E, Borea PA. Pharmacological and biochemical characterization of adenosine receptors in the human malignant melanoma A375 cell line. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1215–1226. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merighi S, Mirandola P, Varani K, Gessi S, Leung E, Baraldi PG, Tabrizi MA, Borea PA. A glance at adenosine receptors: novel target for antitumor therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;100:31–48. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feoktistov I, Ryzhov S, Zhong H, Goldstein AE, Matafonov A, Zeng D, Biaggioni I. Hypoxia modulates adenosine receptors in human endothelial and smooth muscle cells toward an A2B angiogenic phenotype. Hypertension. 2004;44:649–654. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000144800.21037.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Simioni C, Leung E, Maclennan S, Baraldi PG, Borea PA. Caffeine inhibits adenosine-induced accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, vascular endothelial growth factor, and interleukin-8 expression in hypoxic human colon cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:395–406. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.032920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryzhov S, Novitskiy SV, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Carbone DP, Biaggioni I, Dikov MM, Feoktistov I. Host A2B adenosine receptors promote carcinoma growth. Neoplasia. 2008;10:987–995. doi: 10.1593/neo.08478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merighi S, Mirandola P, Milani D, Varani K, Gessi S, Klotz KN, Leung E, Baraldi PG, Borea PA. Adenosine receptors as mediators of both cell proliferation and cell death of cultured human melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:923–933. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Leung E, MacLennan S, Baraldi PG, Borea PA. A3 adenosine receptors modulate hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression in human A375 melanoma cells. Neoplasia. 2005;7:894–903. doi: 10.1593/neo.05334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Leung E, Maclennan S, Borea PA. A3 adenosine receptor activation inhibits cell proliferation via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation in A375 human melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19516–19526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Leung E, Maclennan S, Borea PA. Adenosine modulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in human glioblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gessi S, Merighi S, Varani K, Cattabriga E, Benini A, Mirandola P, Leung E, MacLennan S, Feo C, Baraldi S, et al. Adenosine receptors in colon carcinoma tissues and colon tumoral cell lines: focus on the A3 adenosine subtype. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:826–836. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gessi S, Merighi S, Varani K, Leung E, MacLennan S, Borea PA. The A3 adenosine receptor: an enigmatic player in cell biology. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:123–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Leung E, Maclennan S, Baraldi PG, Borea PA. Hypoxia inhibits paclitaxel-induced apoptosis through adenosine-mediated phosphorylation of bad in glioblastoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:162–172. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baraldi PG, Tabrizi MA, Gessi S, Borea PA. Adenosine receptor antagonists: translating medicinal chemistry and pharmacology into clinical utility. Chem Rev. 2008;108:238–263. doi: 10.1021/cr0682195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen CB, Schneider BK, White CW. Limitations to oxygen diffusion and equilibration in in vitro cell exposure systems in hyperoxia and hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1021–L1027. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.4.L1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feoktistov I, Ryzhov S, Goldstein AE, Biaggioni I. Mast cell-mediated stimulation of angiogenesis: cooperative interaction between A2B and A3 adenosine receptors. Circ Res. 2003;92:485–492. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000061572.10929.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mühl H, Nold M, Chang JH, Frank S, Eberhardt W, Pfeilschifter J. Expression and release of chemokines associated with apoptotic cell death in human promonocytic U937 cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3225. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3225::AID-IMMU3225>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawagishi C, Kurosaka K, Watanabe N, Kobayashi Y. Cytokine production by macrophages in association with phagocytosis of etoposide-treated P388 cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1541:221. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Planting AS, van der Burg ME, Goey SH, Schellens JH, Vecht C, de Boer-Dennert M, Stoter G, Verweij J. Phase II study of a short course of weekly high-dose cisplatin combined with long-term etoposide in metastatic melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2026–2028. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darst M, Al-Hassani M, Li T, Yi Q, Travers JM, Lewis DA, Travers JB. Augmentation of chemotherapy-induced cytokine production by expression of the platelet-activating factor receptor in a human epithelial carcinoma cell line. J Immunol. 2004;172:6330–6335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villani F, Viola G, Vismara C, Laffranchi A, Di Russo A, Viviani S, Bonfante V. Lung function and serum concentrations of different cytokines in patients submitted to radiotherapy and intermediate/high dose chemotherapy for Hodgkin's disease. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:2403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]