Short abstract

Claudins are crucial components of tight junctions and are important in regulating permeability and maintaining cell polarity in cell sheets.

Abstract

The claudin multigene family encodes tetraspan membrane proteins that are crucial structural and functional components of tight junctions, which have important roles in regulating paracellular permeability and maintaining cell polarity in epithelial and endothelial cell sheets. In mammals, the claudin family consists of 24 members, which exhibit complex tissue-specific patterns of expression. The extracellular loops of claudins from adjacent cells interact with each other to seal the cellular sheet and regulate paracellular transport between the luminal and basolateral spaces. The claudins interact with multiple proteins and are intimately involved in signal transduction to and from the tight junction. Several claudin mouse knockout models have been generated and the diversity of phenotypes observed clearly demonstrates their important roles in the maintenance of tissue integrity in various organs. In addition, mutation of some claudin genes has been causatively associated with human diseases and claudin genes have been found to be deregulated in various cancers. The mechanisms of claudin regulation and their exact roles in normal physiology and disease are being elucidated, but much work remains to be done. The next several years are likely to witness an explosion in our understanding of these proteins, which may, in turn, provide new approaches for the targeted therapy of various diseases.

Gene organization and evolutionary history

In metazoans, biological compartments of different compositions are separated by epithelial (or endothelial) sheets. The transport between these compartments, especially the movement of molecules that can occur in between the cells that make up the cellular sheets (paracellular diffusion), is highly regulated. In vertebrates, the tight junctions (TJs) are the structures responsible for forming the seal that controls paracellular transport. TJs are composed of multiple components, but the tetraspan integral membrane proteins known as claudins are essential for TJ formation and function [1].

In mammals, a total of 24 claudin genes have been found (Table 1). Humans and chimpanzees have 23 annotated CLDN genes in their genome (they lack CLDN13), whereas mice and rats have all 24. The exact mechanisms of claudin evolution remain unknown, although some data suggest that the claudin multigene family expanded and evolved via gene duplications early in chordate development [2]. Consistent with this hypothesis is the presence of highly homologous CLDN genes located in close proximity in various mammalian genomes (see below). Interestingly, the genome of the puffer fish Takifugu has a large number of claudin genes (at least 56) as the result of extensive gene duplication [3]. Claudin-like genes have been reported in lower chordates (the ascidian Halocynthia roretzi), as well as in invertebrates (Drosophila) [4], but the exact roles of these claudins in permeability barriers still remain to be elucidated. The presence of these genes suggests that the origin of the claudins may be quite ancient and that a claudin ancestor pre-dates the establishment of the chordates.

Table 1.

Gene IDs for claudin genes in commonly studied mammals

| Gene | Human | Chimpanzee | Rat | Mouse |

| CLDN1 | 9076 | 12738 | 65129 | 12737 |

| CLDN2 | 9075 | 465795 | 300920 | 12738 |

| CLDN3 | 1365 | 742734 | 65130 | 12739 |

| CLDN4 | 1364 | 463464 | 304407 | 12740 |

| CLDN5 | 7122 | 458955 | 65131 | 12741 |

| CLDN6 | 9074 | 467882 | 287098 | 54419 |

| CLDN7 | 1366 | 455232 | 65132 | 53624 |

| CLDN8 | 9073 | 474085 | 304124 | 54420 |

| CLDN9 | 9080 | + | 287099 | 56863 |

| CLDN10 | 9071 | 452626 | 290485 | 58187 |

| CLDN11 | 5010 | 460846 | 84588 | 18417 |

| CLDN12 | 9069 | 463521 | 500000 | 64945 |

| CLDN13 | - | - | + | 57255 |

| CLDN14 | 23562 | 470085 | 304073 | 56173 |

| CLDN15 | 24146 | 463619 | 304388 | 60363 |

| CLDN16 | 10686 | 740268 | 155268 | 114141 |

| CLDN17 | 26285 | 474084 | 304125 | 239931 |

| CLDN18 | 51208 | 470935 | 315953 | 56492 |

| CLDN19 | 149461 | 747192 | 298487 | 242653 |

| CLDN20 | 49861 | 472215 | 680178 | 621628 |

| CLDN21 | 644672 | 740287 | + | 100042785 |

| CLDN22 | 53842 | 743556 | 306454 | 75677 |

| CLDN23 | 137075 | 472693 | 290789 | 71908 |

| CLDN24 | 100132463 | 471363 | 100039801 | 502083 |

The GenBank gene ID is given when the CLDN gene is present in the given species. A dash (-) represents the absence of a particular CLDN homolog in the particular species whereas a plus sign (+) signifies that the gene seems to be present in the genome, although it is not yet annotated and assigned a gene ID in GenBank.

In general, CLDN genes have few introns and several lack introns altogether (Table 2). The result of this is that the genes are typically small, on the order of several kilobases (kb). Several pairs of CLDN genes that are very similar to each other in sequence and in intron/exon arrangement are located in close proximity in the human genome, such as CLDN6 and CLDN9, which are located only 200 bp apart on chromosome 16. CLDN22 and CLDN24 on chromosome 4, CLDN8 and CLDN17 on chromosome 21, and CLDN3 and CLDN4 on chromosome 7 are also located within 50 kb of each other. This genomic structure suggests gene duplication as a crucial driving force in the generation of many of these claudins. Whether the genomic arrangement leads to coordinate regulation is currently unknown but, at least in the case of CLDN3 and CLDN4, coordinate expression has been reported in several normal and neoplastic tissues [5], and expression of these genes is frequently simultaneously elevated in various cancers [6]. The other CLDN genes are dispersed on several human chromosomes, including the X chromosome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Human claudin genes and transcript information

| Gene | Localization | Introns | Transcript information | Protein size | Molecular weight | Pi |

| CLDN1 | 3q28 | 3 | One form | 211 | 22,744 | 8.41 |

| CLDN2 | Xq22 | 1 | One form | 230 | 24,549 | 8.47 |

| CLDN3 | 7q11 | 0 | One form | 220 | 23,319 | 8.37 |

| CLDN4 | 7q11 | 0 | One form | 209 | 22,077 | 8.38 |

| CLDN5 | 22q11 | 1 | Two variants: alternative splicing, coding unaffected | 218 | 23,147 | 8.25 |

| CLDN6 | 16p13 | 1 | One form | 220 | 23,292 | 8.32 |

| CLDN7 | 17p13 | 3 | One form | 211 | 22,390 | 8.91 |

| CLDN8 | 21q22 | 0 | One form | 225 | 24,845 | 9 |

| CLDN9 | 16p13 | 1 | One form | 217 | 22,848 | 6.54 |

| CLDN10 | 13q31 | 1 | Two variants: alternative transcription start site, different amino termini | a: 226 | 24,251 | 9.24 |

| b: 228 | 24,488 | 8.32 | ||||

| CLDN11 | 3q26 | 2 | One form | 207 | 21,993 | 8.22 |

| CLDN12 | 7q21 | 2 | One form | 244 | 27,110 | 8.8 |

| CLDN14 | 21q22 | 2 | Two variants: alternative splicing, coding unaffected | 239 | 25,699 | 8.94 |

| CLDN15 | 7q11 | 4 | One form | 228 | 24,356 | 5.61 |

| CLDN16 | 3q28 | 4 | One form | 305 | 33,836 | 8.26 |

| CLDN17 | 21q22 | 0 | One form | 224 | 24,603 | 9.8 |

| CLDN18 | 3q34 | 4 | Two variants: alternative transcription start site, different amino termini | a: 261 | 27,856 | 8.39 |

| b: 261 | 27,720 | 8.39 | ||||

| CLDN19 | 1p34 | 4 | Two variants: alternative splicing, different carboxyl termini | a: 224 | 23,229 | 8.48 |

| b: 211 | 22,076 | 7.52 | ||||

| CLDN20 | 6q25 | 1 | One form | 219 | 23,515 | 6.98 |

| CLDN21 | 11q23 | 0 | One form | 229 | 25,393 | 5.37 |

| CLDN22 | 4q35 | 0 | One form | 220 | 25,509 | 5.37 |

| CLDN23 | 8p23 | 0 | One form | 292 | 31,915 | 7.51 |

| CLDN24 | 4q35 | 0 | One form | 205 | 22,802 | 4.87 |

The chromosomal localization, intron number, and transcript details are indicated for each of the claudin genes, together with the size (in amino acids), molecular weight (in Da), and isoelectric point (Pi) of their encoded proteins. CLDN10, CLDN18, and CLDN19 have two variants giving rise to slightly different proteins. Only the variants documented in GenBank are indicated and other variants may exist.

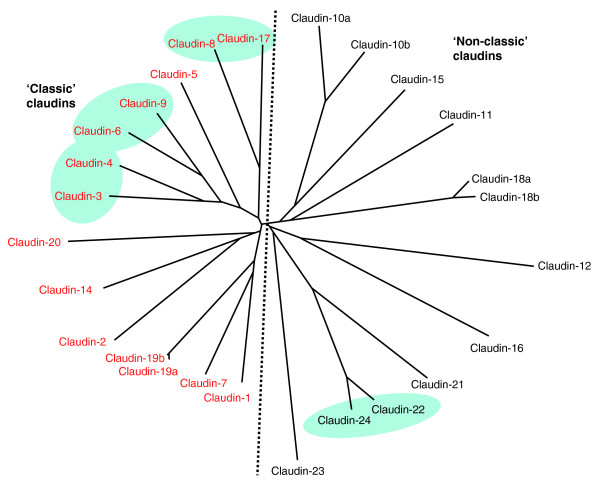

The claudin proteins show a wide range of sequence similarity. Phylogenetic analyses of the human claudins demonstrate very strong sequence relationships between some of them, such as claudin-6 and claudin-9, whereas other claudins are more distantly related (Figure 1). A subdivision of the claudin family into 'classic' and 'non-classic' groups has been suggested from sequence analysis of the mouse claudin proteins [7]. Our analysis with human proteins also suggests that some demarcation can be made between claudins on the basis of sequence homology (Figure 1), although the exact members of the 'classic' and 'non-classic' classes are slightly different from the ones suggested by Krause et al. [7] for the mouse proteins. As the expression patterns and functions of claudin proteins become clearer in the future, it may be possible and more appropriate to subdivide the claudins according to these parameters.

Figure 1.

A phylogenetic tree of full-length human claudin proteins, indicating the relationships between them. Claudin-10, claudin-18, and claudin-19 have two variants resulting from alternative start sites or splicing (Table 2). Highly similar claudins encoded by genes located in close proximity in the human genome are highlighted in green. As previously suggested [7], claudins can be divided in two groups in terms of sequence homology (dashed line): the 'classic' human claudins are indicated in red and the 'non-classic' in black. Human claudin protein sequences were obtained from GenBank (see accession numbers in Table 1) and aligned using ClustalW 2.0.11, which was also used to calculate phylogenetic distances. The unrooted tree was obtained using Drawtree in PHYLIP version 3.67.

Characteristic structural features

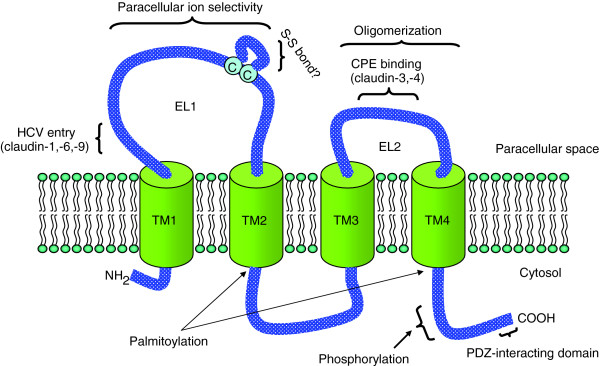

The claudins belong to the PMP22/EMP/MP20/claudin superfamily of tetraspan membrane proteins (PFAM family 00822) [8]. The 24 mammalian members are 20 to 34 kDa in size, with most about 22 to 24 kDa (see Table 2 for information on human claudins). The proteins are predicted, on the basis of hydropathy plots, to have four transmembrane helices with their amino- and carboxy-terminal tails extending into the cytoplasm [1,8] (Figure 2). The typical claudin protein contains a short intracellular cytoplasmic amino-terminal sequence of approximately 4 to 5 residues followed by a large extracellular loop (EL1) of 60 residues, a short 20-residue intracellular loop, another extracellular loop (EL2) of about 24 residues, and a carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic tail (Figure 2). The size of the carboxy-terminal tail is more variable in length; it is typically between 21 and 63 residues, although it can be as large as 106 residues (in the case of claudin-23). The amino acid sequences of the first and fourth transmembrane regions are highly conserved among different claudin isoforms; the sequences of the second and third are more diverse. The first loop contains several charged amino acids and, as such, is thought to influence paracellular charge selectivity [9]. Two highly conserved cysteine residues are present in the first extracellular loop and are hypothesized to increase protein stability by the formation of an intramolecular disulfide bond [10]. It has been suggested that the second extracellular loop, by virtue of its helix-turn-helix motif conformation, can form dimers with claudins on opposing cell membranes through hydrophobic interactions between conserved aromatic residues [11].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the claudin monomer. The model depicts the conserved structural features of claudins and some of the known interactions and modifications. EL1 and EL2 denote the extracellular loops 1 and 2, respectively. The transmembrane domains 1 to 4 (TM1 to TM4) and the regions important for hepatitis C virus (HCV) entry and Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) binding are shown.

The region that shows the most sequence and size heterogeneity among the claudin proteins is the carboxy-terminal tail. It contains a PDZ-domain-binding motif that allows claudins to interact directly with cytoplasmic scaffold ing proteins, such as the TJ-associated proteins MUPP1 [12], PATJ [13], ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3, and MAGUKs [14]. Furthermore, the carboxy-terminal tail upstream of the PDZ-binding motif is required to target the protein to the TJ complex [15] and also functions as a determinant of protein stability and function [8]. The carboxy-terminal tail is the target of various post-translational modifications, such as serine/threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation [16] and palmitoylation [17], that can significantly alter claudin localization and function. Most cell types express multiple claudins, and the homotypic and heterotypic interactions of claudins from neighboring cells allow strand pairing and account for the TJ properties [18], although it appears that heterotypic head-to-head interactions between claudins belonging to two different membranes are limited to certain combinations of claudins [19].

Localization and function

Claudin proteins were first purified as components of TJs [20] and are now known to be essential components of TJ structure and function. TJs are found at the most apical part of the lateral surface of a sheet of epithelial cells and serve as a continuous paracellular seal between the apical and basolateral sections [1,21]. When observed by freeze-fracture microscopy, TJs can be seen to be composed of complex networks of strands, which can be extremely variable in terms of number and complexity depending on the cell type. Claudins are the major constituents of these strands and from various lines of evidence it has been suggested that claudins may be organized as hexamers within the TJs [22].

Surprisingly, it has been shown that, under certain conditions, claudin proteins can be localized to the cytoplasm in both normal and neoplastic tissues [6,23]. This cytoplasmic localization may involve claudin phosphorylation [24]. Although the exact roles of cytoplasmic claudin proteins are unknown, they may be related to vesicle trafficking or cell-matrix interactions [23].

Studies performed by manipulating claudin levels in vitro have established claudins as being crucial in the regulation of the selectivity of paracellular permeability [8,9,25]. Overexpression of various claudins in cell lines affects the epithelial resistance and permeability of different ions, and these changes are dependent on the exact claudins expressed. Site-directed mutagenesis of charged residues has shown that the first extracellular loop has an important role in charge selectivity [8]. For example, substituting a negative charge at residue Lys65 in claudin-4 increases Na+ permeability in Madine-Darby canine kidney II cells [9]. Overall, the data from several studies are consistent with a model in which claudin protein levels and combinations within the TJ have a major role in determining paracellular ion selectivity [8].

Various mouse models have established the importance of claudins in creating barriers and, in some models, highly specific roles have been demonstrated in particular cell types. For example, the Cldn1 knockout mouse model illustrates the importance of this gene in epidermis TJ function. Claudin-1-deficient mice die soon after birth as a consequence of dehydration from transdermal water loss [26].

Claudin-11 deficient mice show deafness because of the disappearance of TJs from the basal cells of the stria vascularis (the lateral secretory wall of the cochlear duct) [27,28]. Similarly, Cldn14 homozygous knockout mice have hearing loss, probably because of impaired ion selectivity in one of the epithelial layers in direct contact with the hair cells (the reticular lamina) [29]. Loss of claudin-19 in a mouse model leads to behavioral deficits, which seem to be due to the disappearance of TJs from Schwann cells, leading to abnormal nerve conduction along peripheral myelinated fibers [30].

Several human diseases have been shown to be caused by mutations in claudin genes. Mutations in the CLDN1 gene result in progressive scaling of the skin and obstruction of bile ducts, known as neonatal sclerosing cholangitis with ichthyosis [31]. The clinical course can vary markedly, from resolution of symptoms to development of liver failure. Mutations in CLDN16 (also known as paracellin-1) cause a rare magnesium wasting disorder characterized by excessive loss of Mg2+ due to kidney malfunction and known as familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciurea and nephrocalcinosis (FHHNC) [32]. CLDN16 expression is restricted to certain junctions of the thick ascending loop of Henle in the kidney, where magnesium and calcium are reabsorbed paracellularly. It is hypothesized that the reduction in cation permeability causes a reduction in the intraluminal electrical gradient necessary to drive magnesium back into the blood. Mutations in CLDN19 are associated with a similar phenotype to that seen in patients with CLDN16 mutations [33]. CLDN19 mutations are also associated with a large number of ocular conditions, such as macular colobomata, nystagmus and myopia. CLDN14 is expressed along the endocochlear epithelium and, when mutated, causes nonsyndromic recessive deafness DFNB29 [34], similar to the phenotype observed in claudin-14-deficient mice [29]. Without being directly affected by known mutations, other claudin proteins have been implicated in human pathologies. Claudin-3 and claudin-4 are known to be surface receptors for the Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin in the gut [35], and claudin-1, claudin-6, and claudin-9 are co-receptors for hepatitis C virus (HCV) entry [36,37].

Several claudin proteins have been shown to be abnormally expressed in cancers [6]; for example, claudin-1 is downregulated in breast and colon cancer [38,39]. These findings are consistent with the long-known fact that TJs are disassembled during tumorigenesis. However, the expression of claudin-3 and claudin-4 has been found to be highly upregulated in multiple cancers [6]. In cancer, over-expressed claudins may have roles in motility, invasion, and survival [40].

Claudin function is regulated at multiple levels [16,41]. Most claudin proteins have potential serine and/or threonine phosphorylation sites in their cytoplasmic carboxy-terminal domains and there are reports suggesting that increased phosphorylation could be associated with changes in barrier function. For example, it has been shown that phosphorylation of claudin-3 and claudin-4 by protein kinase A and C, respectively, results in increased paracellular permeability, possibly because of a mislocalization of claudins [24,42]. Similarly, lysine deficient protein kinase 4 (WNK4) can phosphorylate multiple claudins and increase paracellular permeability [43]. Overall, several claudins are known to be phosphorylated by kinases [16]. Endocytic recycling of claudin proteins is also a potential mechanism of claudin regulation [44], and palmitoylation [17] of these proteins has also been found to influence claudin protein stability. At the transcriptional level, transcription factors such as Snail [45] and GATA-4 [46] can bind to the promoter regions of various claudin genes and affect their expression. Furthermore, there is evidence to support the concept that claudins are downregulated both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally by various growth factors and cytokines [16,47].

Frontiers

We are just beginning to unravel the roles of proteins in TJ formation and function. The large number of claudin proteins and the heterogeneity in their patterns of expression emphasize their crucial roles in the development and maintenance of vertebrate tissues. To add to the complexity, it is now becoming apparent that the claudins are intimately involved in signaling to and from the TJ, providing important cues for cell behavior, such as proliferation and differentiation. These molecular pathways are just emerging and will probably become a major focus of research in the field of claudins and TJs. From a practical point of view, a better understanding of TJ formation and regulation may provide novel avenues for the enhancement of drug delivery and absorption. One promising avenue in cancer research is the possible targeting of tumors overexpressing claudin-3 and -4 with the cytotoxic Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin, which specifically binds these proteins [6]. Similarly, the identification of claudins as receptors for HCV entry suggests these molecules as possible targets for drugs that inhibit HCV infection [37]. In addition to improving our knowledge of the mechanisms important in normal tissue development and maintenance, a better understanding of claudin biology may therefore provide new avenues for targeted therapies of several diseases.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank members of our laboratory for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported entirely by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging.

References

- Tsukita S, Furuse M. Pores in the wall: claudins constitute tight junction strands containing aqueous pores. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:13–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollmar R, Nakamura SK, Kappler JA, Hudspeth AJ. Expression and phylogeny of claudins in vertebrate primordia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10196–10201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171325898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh YH, Christoffels A, Brenner S, Hunziker W, Venkatesh B. Extensive expansion of the claudin gene family in the teleost fish, Fugu rubripes. Genome Res. 2004;14:1248–1257. doi: 10.1101/gr.2400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu VM, Schulte J, Hirschi A, Tepass U, Beitel GJ. Sinuous is a Drosophila claudin required for septate junction organization and epithelial tube size control. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:313–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt KJ, Agarwal R, Morin PJ. The claudin gene family: expression in normal and neoplastic tissues. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin PJ. Claudin proteins in human cancer: promising new targets for diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9603–9606. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause G, Winkler L, Mueller SL, Haseloff RF, Piontek J, Blasig IE. Structure and function of claudins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:403–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegio OR, Van Itallie CM, McCrea HJ, Rahner C, Anderson JM. Claudins create charge-selective channels in the paracellular pathway between epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C142–C147. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00038.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelow S, Ahlstrom R, Yu AS. Biology of claudins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F867–F876. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90264.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontek J, Winkler L, Wolburg H, Muller SL, Zuleger N, Piehl C, Wiesner B, Krause G, Blasig IE. Formation of tight junction: determinants of homophilic interaction between classic claudins. FASEB J. 2008;22:146–158. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8319com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki Y, Itoh M, Sasaki H, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1) is concentrated at tight junctions through its possible interaction with claudin-1 and junctional adhesion molecule. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:455–461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh MH, Liu CJ, Laurinec S, Margolis B. The carboxyl terminus of zona occludens-3 binds and recruits a mammalian homologue of discs lost to tight junctions. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27501–27509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Furuse M, Morita K, Kubota K, Saitou M, Tsukita S. Direct binding of three tight junction-associated MAGUKs, ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3, with the COOH termini of claudins. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1351–1363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffer C, Gerke V. The C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of claudins 1 and 5 but not its PDZ-binding motif is required for apical localization at epithelial and endothelial tight junctions. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:135–144. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mariscal L, Tapia R, Chamorro D. Crosstalk of tight junction components with signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:729–756. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie CM, Gambling TM, Carson JL, Anderson JM. Palmitoylation of claudins is required for efficient tight-junction localization. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1427–1436. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:285–293. doi: 10.1038/35067088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty BL, Ward C, Smith T, Ritzenthaler JD, Koval M. Regulation of heterotypic claudin compatibility. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30005–30013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin-1 and -2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1539–1550. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K, Furuse M, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin multigene family encoding four-transmembrane domain protein components of tight junction strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:511–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitic LL, Unger VM, Anderson JM. Expression, solubilization, and biochemical characterization of the tight junction transmembrane protein claudin-4. Protein Sci. 2003;12:218–227. doi: 10.1110/ps.0233903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman B, Russell T, Nordeen SK, Medina D, Neville MC. Claudin 7 expression and localization in the normal murine mammary gland and murine mammary tumors. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R248–R255. doi: 10.1186/bcr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza T, Agarwal R, Morin PJ. Phosphorylation of claudin-3 at threonine 192 by cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates tight junction barrier function in ovarian cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26233–26240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, Renigunta A, Konrad M, Gomes AS, Schneeberger EE, Paul DL, Waldegger S, Goodenough DA. Claudin-16 and claudin-19 interact and form a cation-selective tight junction complex. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:619–628. doi: 10.1172/JCI33970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, Yoshida Y, Haratake A, Sugitani Y, Noda T, Kubo A, Tsukita S. Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1099–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Davies C, Southwood CM, Frolenkov G, Chrustowski M, Ng L, Yamauchi D, Marcus DC, Kachar B. Deafness in Claudin 11-null mice reveals the critical contribution of basal cell tight junctions to stria vascularis function. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7051–7062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1640-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajiri S, Miyamoto T, Mineharu A, Sonoda N, Furuse K, Hata M, Sasaki H, Mori Y, Kubota T, Ito J, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Compartmentalization established by claudin-11-based tight junctions in stria vascularis is required for hearing through generation of endocochlear potential. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5087–5096. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yosef T, Belyantseva IA, Saunders TL, Hughes ED, Kawamoto K, Van Itallie CM, Beyer LA, Halsey K, Gardner DJ, Wilcox ER, Rasmussen J, Anderson JM, Dolan DF, Forge A, Raphael Y, Camper SA, Friedman TB. Claudin 14 knockout mice, a model for autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29, are deaf due to cochlear hair cell degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2049–2061. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T, Morita K, Takemoto D, Takeuchi K, Kitano Y, Miyakawa T, Nakayama K, Okamura Y, Sasaki H, Miyachi Y, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Tight junctions in Schwann cells of peripheral myelinated axons: a lesson from claudin-19-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:527–538. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadj-Rabia S, Baala L, Vabres P, Hamel-Teillac D, Jacquemin E, Fabre M, Lyonnet S, De Prost Y, Munnich A, Hadchouel M, Smahi A. Claudin-1 gene mutations in neonatal sclerosing cholangitis associated with ichthyosis: a tight junction disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1386–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DB, Lu Y, Choate KA, Velazquez H, Al-Sabban E, Praga M, Casari G, Bettinelli A, Colussi G, Rodriguez-Soriano J, McCredie D, Milford D, Sanjad S, Lifton RP. Paracellin-1, a renal tight junction protein required for paracellular Mg2+ resorption. Science. 1999;285:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad M, Schaller A, Seelow D, Pandey AV, Waldegger S, Lesslauer A, Vitzthum H, Suzuki Y, Luk JM, Becker C, Schlingmann KP, Schmid M, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Ariceta G, Cano F, Enriquez R, Juppner H, Bakkaloglu SA, Hediger MA, Gallati S, Neuhauss SC, Nurnberg P, Weber S. Mutations in the tight-junction gene claudin 19 (CLDN19) are associated with renal magnesium wasting, renal failure, and severe ocular involvement. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:949–957. doi: 10.1086/508617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox ER, Burton QL, Naz S, Riazuddin S, Smith TN, Ploplis B, Belyantseva I, Ben-Yosef T, Liburd NA, Morell RJ, Kachar B, Wu DK, Griffith AJ, Riazuddin S, Friedman TB. Mutations in the gene encoding tight junction claudin-14 cause autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29. Cell. 2001;104:165–172. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katahira J, Sugiyama H, Inoue N, Horiguchi Y, Matsuda M, Sugimoto N. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin utilizes two structurally related membrane proteins as functional receptors in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26652–26658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM, Syder AJ, Panis M, Wolk B, Hatziioannou T, McKeating JA, Bieniasz PD, Rice CM. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature. 2007;446:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nature05654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng A, Yuan F, Li Y, Zhu F, Hou P, Li J, Song X, Ding M, Deng H. Claudin-6 and claudin-9 function as additional coreceptors for hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2007;81:12465–12471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01457-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer F, White K, Kubbies M, Swisshelm K, Weber BH. Genomic organization of claudin-1 and its assessment in hereditary and sporadic breast cancer. Hum Genet. 2000;107:249–256. doi: 10.1007/s004390000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MB, Konkin T, Routhier J, Sabo E, Pricolo VE. Claudin-1 is a strong prognostic indicator in stage II colonic cancer: a tissue microarray study. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:511–518. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal R, D'Souza T, Morin PJ. Claudin-3 and claudin-4 expression in ovarian epithelial cells enhances invasion and is associated with increased matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7378–7385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley MK, Koval M. Regulation and roles for claudin-family tight junction proteins. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:431–437. doi: 10.1002/iub.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza T, Indig FE, Morin PJ. Phosphorylation of claudin-4 by PKCepsilon regulates tight junction barrier function in ovarian cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3364–3375. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi K, Rai T, Kobayashi K, Sohara E, Suzuki T, Itoh T, Suda S, Hayama A, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Disease-causing mutant WNK4 increases paracellular chloride permeability and phosphorylates claudins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4690–4694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306924101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M, Kubo A, Furuse M, Tsukita S. A peculiar internalization of claudins, tight junction-specific adhesion molecules, during the intercellular movement of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1247–1257. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikenouchi J, Matsuda M, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Regulation of tight junctions during the epithelium-mesenchyme transition: direct repression of the gene expression of claudins/occludin by Snail. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1959–1967. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escaffit F, Boudreau F, Beaulieu JF. Differential expression of claudin-2 along the human intestine: implication of GATA-4 in the maintenance of claudin-2 in differentiating cells. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203:15–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AB, Harris RC. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation differentially regulates claudin expression and enhances transepithelial resistance in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3543–3552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]