Abstract

CEACAM1-4L (carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1, with 4 extracellular Ig-like domains and a long, 71 amino acid cytoplasmic domain) is expressed in epithelial cells and activated T-cells, but is down-regulated in most epithelial cell cancers and T-cell leukemias. A highly conserved sequence within the cytoplasmic domain has ca 50% sequence homology with Tcf-3 and −4, transcription factors that bind β-catenin, and to a lesser extent (32% homology), with E-cadherin that also binds β-catenin. We show by quantitative yeast two-hybrid, BIAcore, GST-pull down, and confocal analyses that this domain directly interacts with β-catenin, and that H-469 and K-470 are key residues that interact with the armadillo repeats of β-catenin. Jurkat cells transfected with CEACAM1-4L have 2-fold less activity in the TOPFLASH reporter assay, and in MCF7 breast cancer cells that fail to express CEACAM1, transfection with CEACAM1 and growth in Ca2+ media causes redistribution of β-catenin from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane, demonstrating a functional role for the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 in regulation of β-catenin activity.

Keywords: CEACAM1, β-catenin, tumor suppressor, cell-cell adhesion

Introduction

CEACAM1 (carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1) is a type I membrane glycoprotein that mediates homotypic cell adhesion and belongs to the CEA gene family (1). It has been shown to play a role in bacterial and viral uptake (2-5), in insulin clearance (6), in angiogenesis (7), in NK and T-cell regulation (8-11), and in tumor suppression (12, 13). CEACAM1 has many isoforms produced by alternative mRNA splicing resulting in protein products with one, three, or four Ig-like extracellular domains with either a long (71 amino acids) or a short (12–14 amino acids) cytoplasmic domain. In epithelial cells, both the long (e.g., CEACAM1-4L) and short (e.g., CEACAM1-4S) cytoplasmic domains are expressed (14) while in activated lymphocytes and neutrophils only the long cytoplasmic domain isoform is expressed (15). In the case of breast epithelial cells we have shown that CEACAM1 is expressed on the lumenal surface of normal mammary epithelial cells (14), and that in a 3D model of mammary morphogenesis, blocking its expression with either an antisense gene or anti-CEACAM1 antibodies blocks lumen formation (16, 17), while in breast cancer cells, that lack CEACAM1 and fail to form lumena in 3D culture, lumen formation is restored to normal when these cells are transfected with the epithelial specific CEACAM1-4S isoform (17). In the case of activated T-cells, CEACAM1-4L is expressed, its ITIMs are phosphorylated and associated with SHP-1, inhibiting further activation (18-22); however, CEACAM1 is down-regulated in T-cell leukemias (15). CEACAM1 gene expression has also been shown to be down-regulated early in colon cancer (12, 23). In a variety of cancer models re-introduction of the CEACAM1 gene causes reversion of the malignant phenotype (24-27). Many of these activities have been ascribed to signaling from the cytoplasmic domain isoforms which, in addition to its association with c-src (28, 29) and SHP-1 and SHP-2 (20), also interact with actin, tropomyosin, calmodulin, annexin-2 p11 tetramer AIIt, filamin A, paxillin, talin and polymerase delta interaction protein p38 (30-36).

To further identify signaling partners in its tumor suppressor activity, we investigated the significance of a highly conserved sequence within the long cytoplasmic domain that exhibited sequence homology to several proteins known to bind β-catenin. Indeed, we were able to show a direct interaction between the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 and β-catenin by a number of assays, including quantitative yeast two-hybrid, BIAcore, GST-pull down, and confocal microscopy. Since β-catenin plays a central role in controlling cell-cell adhesion and proliferation (37), we postulate that some of the tumor suppressor activities ascribed to CEACAM1 are due to its interaction with β-catenin. In addition, our studies identified two key residues that interact with the armadillo repeat of β-catenin.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Baits for Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

The nucleotide and amino acid sequence for CEACAM1-4L was taken from NCBI entry number NP_001703, gi: 19923195. To construct the bait containing the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1-4L (aa 451–526) for yeast two-hybrid screening, an EcoRI site was introduced in front of F451 (nt 1352) of CEACAM1-4L by site directed mutagenesis, using forward and reverse primers, 5′-gcagtagcc-ctggaattctttctgcatttcg-3′ and 5′-cgaaatgcagaaagaattccagggctactgc-3′ and KS/CEACAM1-4L as a template. The plasmid DNA was digested by EcoRI and PstI and subcloned into pGKT7 (Clontech) to create pGKT7/CEACAM1-4L-cyt. hTcf-4 (aa 1–60) was cloned by RT-PCR using forward and reverse primers 5′-cggaatt-cctcccaggagaaaaagacc-3′ and 5′-cgggatc-catcggaggagctgttttg-3′ from RNA isolated from Jurkat cells and subcloned into the EcoR1/BamH1 sites of the pGBKT7 vector. The sequence of hTcf-4 was taken from NCBI entry number gi: 4469252. All PCR reactions were performed using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

A series of single alanine mutants of CEACAM1-4L-cyt were created by sequence overlap extension PCR. The Matchmaker 5′ DNA-BD vector insert screening sense amplimer was 5′-tcatcggaagagagtagtaa-3′ and Matchmaker 3′ DNA-BD vector insert screening antisense amplimer was 5′-agagtcactttaaatttgtat-3′. For each mutant, a set of inside primers was synthesized (Supplementary Material, Table 1S). The pGKT7/CEACAM1-4L-cyt plasmid served as the template. In the first PCR run, the inside antisense primer was used with external sense primer and the inside sense primer was used with external sense primer to create two overlapping fragments. Both of these fragments served as templates to produce the larger fragment using the external primer set. The resulting products were digested with EcoRI and PstI, and ligated into pGKT7 previously cut with the same restriction enzymes.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screen and Analysis

The cytoplasmic domain from CEACAM1-4L (aa 451–526) was subcloned into pGKT7, transformed into yeast AH109 cells, and used as bait to screen the prey—the Arm repeat of the β-catenin (aa 136–671) which was subcloned into pACTII and transformed into yeast Y187 cells. The full-length β-catenin was kindly provided by Dr. Yanhong Shi (Division of Neurosciences, City of Hope). After mating, cells were plated on plates lacking Leu, Trp, His, and adenine (Ade). Colonies were replica plated onto a plate lacking Leu, Trp, His, and Ade and printed onto a filter paper for β-galactosidase analysis using X-gal as a substrate. Plasmid DNA of positive diploid clones were purified and transformed into E. coli DH5. Transformants carrying the β-catenin/prey were selected on LB/ampicillin plates. Plasmid DNA was purified and sequenced. The β-catenin/prey plasmid DNA was transformed into yeast AH109 carrying the CEACAM1-4L-cyt bait construct or transformed into yeast Y187 for mating experiments. The co-transformants or mated cells were selected on plates lacking His and Trp and the overnight culture supernatants were assayed for β-galactosidase using PNP-β-Gal as a substrate. The results (quadruplicates) were normalized to cell mass measure at A600nm.

GST-Fusion Proteins and GST-Pull-Down Assay

pGEX-4T-2 (Amersham) was used to construct vectors expressing GST-CEACAM1-4L-cyt fusion proteins. The pGKT7/CEACAM1-4L-cyt and pGKT7/CEACAM1-4L-cyt mutant plasmids served as the templates. The 5′ prime insert screening sense amplimer was 5-cggaattcctgcatttcgggaagaccggc-3′ and the 3′ prime insert antisense amplimer was 5-ttttccttttgcgg-ccgctcaagtaacttc-3. PCR conditions were 95°C/1 min, 18 cycles of 95°C/30 sec, 55 °C/1 min, and 68°C/1 min. After an EcoRI and NotI digestion, the fragments were subcloned individually in frame with respect to GST into pGEX-4T-2, which was digested with the same restriction enzymes. Similarly, full length hTcf4 was cloned into the BamH1/NotI sites of pGEX-4T-2 using the 5′-insert amplimer 5′-cgggatccatgccgcagctgaacgg-cgg-3′ and the 3′-insert amplimer was 5-ttttcttttgcggccgctattctaaagacttggt-gacgag-3′. GST, GST-CEACAM1-4L-cytoplasmic domain (451–526), GST-CEACAM1-4L-cytoplasmic domain mutants, and GST-hTcf-4 were expressed and purified according to manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce Biotechnology).

Confocal Microscopy

The cellular distribution of CEACAM1-4L-eGFP in stably transfected Jurkat cells was performed on cells plated on 6 well slides precoated with 20 ng/ml of fibronectin (Sigma). Cells were permeabilized in PSG (0.01% saponin PBS) containing 0.5% NP-40 for 20 min at 20°C and stained for β-catenin using mouse anti-β-catenin (BD Transduction Labs) followed by Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes). For colocalization of CEACAM1-4L with β-catenin, in PBMCs or in CEACAM1-4L stably transfected MCF-7 cells, the cells were grown in 6 well chamber slides precoated with fibronectin (20 ng/ml) for 1–2 d in DMEM plus 10% FBS, followed by fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 45 min and staining with rabbit anti-CEACAM1 antibody 22-9 (1:500) for 1 hr and Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 1 hr. Staining for β-catenin was performed after permeabilization as described above. Staining for E-cadherin was performed with FITC-mouse anti-E-cadherin (BD Transduction Labs). In order to remove E-cadherin from the plasma membrane, cells were treated with 2 mM EGTA and 2.5 mM glucose for 10 min, grown in Ca2+-free media for 1–2 d, and transferred to glass slides overnight. The slides were mounted in 80% glycerol/PBS and observed on a Zeiss Confocal microscope using FITC and Rhodamine filter settings to detect GFP and Alexa-488 or Texas Red, respectively.

Peptide Synthesis

Synthetic peptides corresponding to amino acids 451–484 (wild type, or mutants H469A or K470A) adjacent to the transmembrane domain of the CEACAM1 long cytoplasmic domain were synthesized using FMOC chemistry by the City of Hope Peptide Synthesis Core. Peptides were purified to >95% purity by reversed-phase HPLC on a Vydac C18 column and their masses confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry on a Finnigan LCQ ion trap mass spectrometer.

BIAcore Analysis

Biomolecular interaction analyses were carried out in HBS-buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) Surfactant P20, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 or pH 5.5) using the BIAcore® T100 (BIAcore, Inc.). GST-fusion proteins were immobilized on a CM5 sensorchip (BIAcore) using the Amine Coupling Kit (BIAcore). The surface of the sensorchip was activated with 30 μl EDC/NHS (100 mM N-ethyl-N′-(dimethyl-aminopropyl)-carbodimide-hydrochloride, 400 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide) using a flow rate of 5 μl/min. For immobilization of fusion proteins, 1–10 μg in 100 μl 10 mM sodium acetate pH 4.0 were applied (flow rate: 5 μl/min). Subsequently, the sensorchip was deactivated with 30 μl of 1 M ethanolamine hydrochloride pH 8.5 (flow rate: 5 μl/min) and HBS flowed for 5 mins. Binding studies and regeneration of the chip surface between injections were carried out at a flow rate of 20 μl/min unless otherwise noted. Peptides (wild type and mutants H469A, K470A, D479A, T477A were tested at 4 and 5 μM) were diluted in HBS-buffer immediately prior to injection. Between sample injections the surface was regenerated with 15 μl of 10 mM HCl. Data were analyzed with BIAevaluation BIAcore T100 V1.1 evaluation software (BIAcore, Piscataway, NJ), and curve fitting was done with the assumption of one-to-one (Langmuir) binding.

TOPFLASH Reporter Assay

Reporter assays were performed in Jurkat cells seeded into 6 well plates (2 × 105 cells per well) and transfected with 3.5 μg of pTOPFLASH firefly-luciferase reporter (Promega), and 1 μg of pCMV-β plasmid (Promega) as a transfection control. FUGENE 6 (9 μl) was used as the transfection agent. After 48 hr of incubation, the cells were washed with PBS, lysed with reporter lysis buffer (Promega), and firefly luciferase and β-galactosidase activities measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Results were normalized to β-galactosidase and reported as the average of triplicate assays. Negative control experiments included transfection with pFOPFLASH (Promega) containing mutated LEF/Tcf sites. Jurkat cells were also transfected with a constitutively active form of β-catenin missing the first 90 amino acids (ΔN90) as a positive control (kindly provided by Dr. Yanhong Shi, City of Hope).

Molecular Modeling

A molecular model of CEACAM1-4L cytoplasmic domain was built using the MODELLER 6v1 (38). Coordinates for the N-terminal half of the cytoplasmic tail (residues 451–484) were modeled using residues D676–D714 of phosphorylated E-cadherin bound to β-catenin as a template (39). Prior to running MODELLER, three residue library files (models.lib, restyp.lib, and top_polh.lib) were edited to include topological parameters for phosphoserine and phosphothreonine, which were derived from related entries (SER, THR, and MP_2) in the CHARMM 22 residue topology file. Of the 15 models generated, the model with the lowest potential energy and least violation of spatial restraints was selected.

Results and Discussion

Homology of the Long Cytoplasmic Domain of CEACAM1 β-Catenin-Binding Proteins

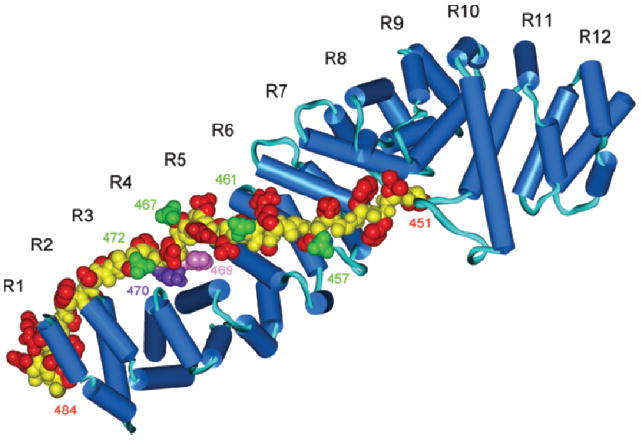

Upon examining the sequence homology of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 from man with other species (rat, mouse, and cow), we noted a highly conserved region within the first 35 amino acids of the 71 amino acid domain. When this sequence was searched across the human protein database using BLAST, major hits were obtained for the transcription factors Tcf-3 and Tcf-4, both of which bind β-catenin (data not shown). Conserved residues among the four species sequenced in the CEACAM1 long cytoplasmic domain and their alignment with Tcf-3 and Tcf-4, as well as LEF-1 and E-cadherin that also bind β-catenin, are shown in Table 1. In the cases of Tcf-3, Tcf-4 and E-cadherin, these residues have been shown to directly interact with the armadillo repeats of β-catenin by a variety of assays including x-ray crystallography (39-41). Using this region of the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin as a template (aa 830–863, Table 1), we constructed a model of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 (aa 451–484) docked to β-catenin to evaluate the potential interaction and to predict key residues within this putative interaction (Fig. 1). As can be seen from this model, His-469 was predicted to be deeply buried between armadillo repeats 3–4 of β-catenin. In order to test this prediction, we performed a number of assays in which His-469 (and adjoining residues) were mutated to the neutral amino acid, Ala.

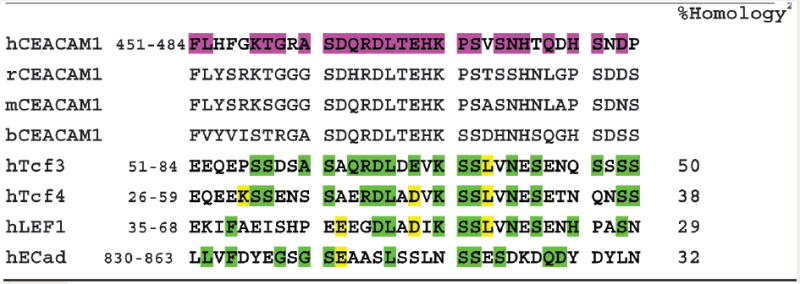

Table 1.

Sequence homology of CEACAM1 to Tcf/LEF and E-cadherin.1

|

The long cytoplasmic domains of rat, murine, and bovine CEACAM1 are aligned with human CEACAM1 using NCBI numbering (hCEACAM1, NP 001703, gi: 19923195). Residues that occur in any one of the other three species (rCEACAM1, NP 001029032, gi: 76496477; mCEACAM1 NP 001034274, gi: 85719299; bCEACAM1, NP 991357, gi: 45430005) are highlighted in purple in the human sequence. The aligned sequences of hTcf3 (Q9HCS4, gi: 29337134), hTcf4 (CAB 97218, gi: 9188632), hLEF1 (NP 057353, gi: 7705917), and hECAD (NP 004351, gi: 4757960) are shown with residues that occur in any of the CEACAM1 species highlighted in green (conservative substitutions are highlighted in yellow).

The percent homologies of the green highlighted residues compared to the purple highlighted residues are shown.

Figure 1.

Homology model of the interaction of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 with β-catenin. The sequence of the long cytoplasmic domain of human CEACAM1 is shown in Table 1. The homology model is based on the x-ray structure of the armadillo repeats of murine β-catenin complexed with residues 577–728 of murine E-cadherin. Blue, β-catenin; yellow, peptide backbone; red, side chains; green, potential phosphorylation sites of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1. H-469 and K-470 are shown in magenta and purple respectively. R1–R12 denote the 12 Arm repeats of β-catenin.

Binding of β-Catenin to the Long Cytoplasmic Domain of CEACAM1 in a Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

The yeast two-hybrid assay allows one to test the potential interaction of two protein domains in a living cell with a quantitative read-out. When the entire 72-amino acid version of the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1-4L was used as bait vs. the armadillo repeat (aa 134–671, Arm) of β-catenin a strong signal was obtained compared to control vectors lacking either the bait or the prey sequences (Table 2). When 1–60hTcf-1 was used as bait with the Arm repeats of β-catenin as a positive control, only a low signal was observed. Since others (42) had suggested that only the Arm repeats of β-catenin were required to interact with 1-60hTcf-4, we were surprised that the signal for the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 was stronger. In order to better understand this result, we used full-length β-catenin as prey, and only under these conditions were equivalent signals for 1-60hTcf-4 and the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 obtained. Thus, the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 and 1-60hTcf-4 interact with β-catenin with the same relative strengths in the yeast two-hybrid assay, and according to these data, only the Arm repeats of β-catenin are required for the interaction with CEACAM1.

Table 2.

Interaction of the Long Cytoplasmic Domain of CEACAM1 with β-Cateninin a Quantitative Yeast Two-Hybrid Assaya

| Baitb | Prey | Responsec | P-valued |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | Arm-β-catenin | 0.079 ± 0.001 | |

| Long cyto. domain | none | 0.046 ± 0.001 | |

| Long cyto. domain | Arm-β-catenin | 0.468 ± 0.015 | 0.001 |

| 1-60hTcf-4 | Arm-β-catenin | 0.206 ± 0.01 | 0.001 |

| Long cyto. domain | FL-β-catenin | 0.378 ± 0.011 | 0.001 |

| 1-60hTcf-4 | FL-β-catenin | 0.422 ± 0.02 | 0.001 |

See methods for the assay details.

Bait (e.g., the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1) was fused to Gal4 BD (binding domain) and prey (e.g., the armadillo repeat (Arm) or full length (FL) β-catenin) was fused to the Gal4 AD (activation domain). 1-60hTcf-4 was used as a positive control.

A410nm normalized for cell density.

Calculated by the chi-squared method.

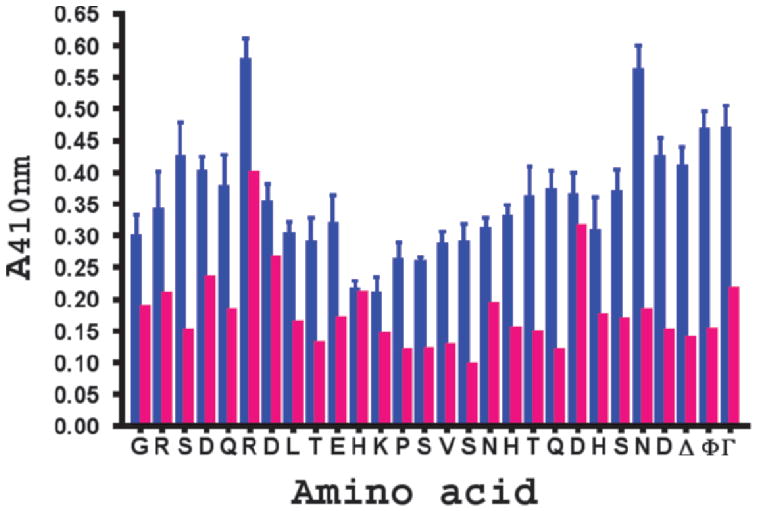

In order to determine critical residues in the long cytoplasmic domain bait, each of the residues were sequentially mutated to alanine and re-tested in the quantitative yeast two-hybrid assay (Fig. 2). The results reveal that mutation of His-469, Lys-470, and to a lesser extent Asp-479 reduce the binding to β-catenin to near background levels. It is noteworthy that these residues are located in the middle of the sequence postulated to bind β-catenin and correspond to key residues within the β-catenin binding sites of Tcf-3, Tcf-4, LEF-1 and E-cadherin (43). Therefore, these results confirm a major prediction of the homology model shown in Figure 1, namely that H469 is a critical binding residue.

Figure 2.

Results of alanine scanning mutagenesis on the binding of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 with β-catenin. The wild type sequence of the long cytoplasmic domain is shown on the x-axis and the results of a quantitative yeast two-hybrid assay (± SED, 4 replicates) shown on the y-axis. Red bars. minus bait; blue bars, plus bait; Δ, truncated version (451–484) of the long cytoplasmic domain; Φ, wild type version of CEACAM1 long cytoplasmic domain; Γ, 1-60hTcf-4 as the positive control. Except for mutants H469A, K470A, and D479A, P < 0.001 (bait vs. no bait); thus, identifying these 3 residues as hot spots for binding β-catenin.

Binding Kinetics of the Cytoplasmic Domain- β-Catenin Interactions

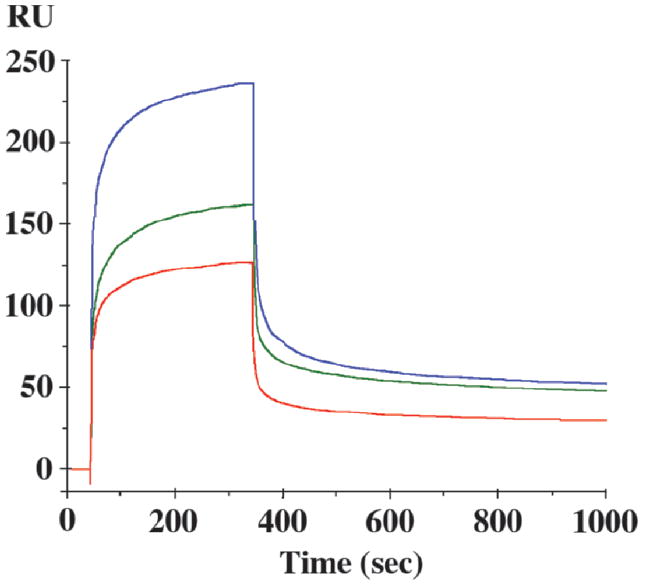

Although the yeast two-hybrid assay demonstrated that β-catenin and the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 can interact in vitro, it is possible that the interaction was indirect and/or depended on either the presence of other proteins or post-translational modifications. Therefore, the direct interaction of β-catenin with the cytoplasmic domain was tested in a BIAcore assay. In this assay a GST- β-catenin fusion protein containing just the Arm repeats of β-catenin was immobilized on a BIAcore chip and synthetic peptides corresponding to aa 451–484 of the wild type or mutated (H469A, K470A) versions of the cytoplasmic domain were flowed over the chip and the binding kinetics measured (Fig. 3, Table 3). From the kinetics, the dissociation constants were calculated (KD) and demonstrate that the interaction is in the nM range, well within the estimated physiological concentrations of both CEACAM1 and β-catenin at the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane. It can be seen that the interaction of the wild type peptide with GST-β-catenin-Arm is strongest for the wild type peptide and >9-fold less for the K470A and H469A mutants. Controls included the D479A and T477A mutants that had significant and minimal effects, respectively, on binding in the yeast two-hybrid assay. Both of these mutants bound similarly to the wild type on the BIAcore assay (data not shown). These results strengthen the conclusion that H469 and K470 are key residues in this interaction, further supporting our domain homology model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

BIAcore analysis of the binding of the wild type and mutated versions of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 to GST-β-catenin. The GST fusion protein of the armadillo repeats (residues 134–671) of human β-catenin was immobilized to a CM5 chip using standard amine chemistry and synthetic peptides containing either the wild type sequence (451–484; upper curve, blue) or mutated versions of the peptide K470A (middle curve, green) or H469A (bottom curve, red) were flowed over it vs. a CM5 chip with immobilized GST alone. Only the GST subtracted curves are shown (no binding to GST alone was detected). All peptides were run at 4 μM.

Table 3.

Binding Constants for the Interaction of Peptides from the Long Cytoplasmic Domain of CEACAM1 with GST-β-Catenina

| Peptide | kon (M −1sec−1) | koff (sec −1) | KD (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 7.95 × 104 | 4.73 × 10−4 | 5.9 |

| K470A | 5.88 × 103 | 5.05 × 10−4 | 86 |

| H469A | 8.98 × 103 | 4.94 × 10−4 | 54 |

The GST-fusion protein (50 μg/ml) of the armadillo repeats (residues 136–671) of β-catenin was immobilized to a BIAcore CM5 chip and the binding of wild type or mutated version of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 flowed over it vs. a CM5 chip immobilized with GST. All peptides were at 4 μM.

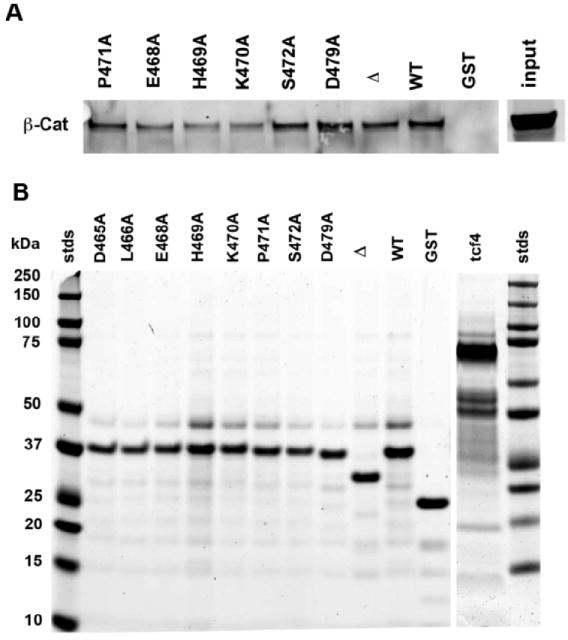

GST-Pull Down Analysis

Although the yeast two-hybrid and BIAcore data demonstrate that the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 and β-catenin can interact, they do not prove that they actually interact in cells that express these two proteins. In order to demonstrate that a “real life” interaction is possible, we generated GST-fusion proteins of the full-length wild type (aa 451–526), a truncated version (aa 451–484) and mutated versions of the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1, incubated them with lysates of Jurkat cells known to contain high levels of β-catenin, and ran the bound and eluted proteins on SDS gels to determine if β-catenin was pulled down. As shown in Figure 4 and Table 4, the wild type sequence was the most effective in binding β-catenin, followed by mutants D479A, E468A, P471A S472A, and D465A, residues that flank the critical residues H469 and K470. Mutants H469A and K470A bound the least amount of β-catenin. In this assay the truncated version of the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 bound similar amounts of β-catenin as the full-length domain, suggesting that additional residues in the full-length domain are not required for the interaction with β-catenin in vivo. Controls included GST alone (no binding) and either GST-1-60hTcf-4 (no binding, data not shown) or full-length GST-hTcf-4 (strong binding). It is noteworthy, that no binding was seen for GST-1-60hTcf-4, suggesting that additional sequences within hTcf4 contribute to β-catenin binding. Jurkat cells were selected for this assay because they express high levels of β-catenin (44) and no CEACAM1 (15) nor E-cadherin (45), both of which could have led to an interference in the assay. While these cells do express Tcf-1/LEF-1, the amounts were either too low or too weak to interfere. Since high β-catenin expression is frequently observed in T-cell leukemias, including Jurkat cells (44), and CEACAM1-4L has been shown by us to inhibit proliferation in Jurkat cells (11), it is likely that the two genes are oppositely regulated to control cell growth. Taken together, these data suggest a role for CEACAM1 in regulating the transcriptional activity of β-catenin.

Figure 4.

GST pull-down assays using the long cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1-4L and Jurkat cell lysates. GST fusion proteins (100 μg) containing either the wild type sequence (451–526) of the long cytoplasmic domain or selected mutants were incubated with lysates (2 mg) of Jurkat cells, washed with Profound lysis buffer in TBS, and bound proteins eluted with 100 mM reduced glutathione, run on SDS gels, and western blotted with anti- β-catenin antibody (A). The experiment was quantitated by first integrating the β-catenin from the eluted gluatathione beads, demonstrating that β-catenin was present in the Jurkat cell lysates (input), and normalized to GST-fusion protein input as analyzed by Coomasie Blue stained gels (B). The results were reported as fraction of the wild type. Δ, truncated version (451–484) of the long cytoplasmic domain; Tcf-4, full-length version of hTcf-4 (hTcf-4 was quantitated from a separate gel containing the wild type control); GST, GST only control. Quantitative results for all the mutants tested are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Binding of GST-Fusion Proteins to β-Catenin in Jurkat Cell Lysatesa

| GST-fusion protein | β-catenin (normalized) |

|---|---|

| WT | 1.00 |

| D465A | 0.48 |

| E468A | 0.78 |

| H469A | 0.25 |

| K470A | 0.46 |

| P471A | 0.88 |

| S472A | 0.49 |

| D479A | 0.93 |

| Δ | 0.88 |

| Tcf-4 | 3.46 |

| GST | 0.06 |

GST fusion proteins containing either the wild type sequence (451–526) of the long cytoplasmic domain or selected mutants were incubated with lysates of Jurkat cells, washed with Profound lysis buffer in TBS, and bound proteins eluted with 100 mM reduced glutathione, run on SDS gels, and western blotted with anti- β-catenin and GST antibodies. The western blots were scanned and quantitated on the LiCor Odessey and β-catenin amounts were normalized first to GST-fusion protein and then to the wild type GST fusion protein. Alternatively, the input of GST-fusion protein was normalized to Coomassie Blue stained gels as shown in Figure 4. Δ, truncated version (451–484) of the long cytoplasmic domain; Tcf-4, full-length version of hTcf-4; GST, GST only control.

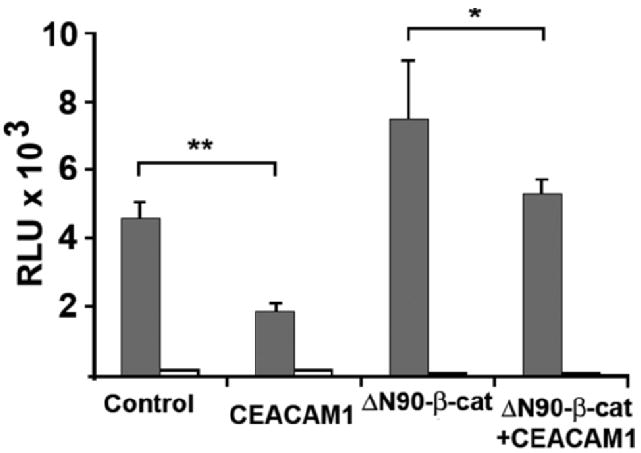

Transcriptional Activity of β-Catenin in Jurkat Cells

To directly test the hypothesis that CEACAM1-4L can regulate β-catenin transcriptional activity in Jurkat cells, we transfected Jurkat or Jurkat/CEACAM1-4L cells with either TOPFLASH containing 4 copies of the LEF/Tcf minimal promoter or FOPFLASH containing 4 copies of the mutated inactive promoter. The results show that CEACAM1-4L reduces transcriptional activity by >2-fold while no activity is seen for the FOPFLASH transfected controls (Fig. 5). As a further control, Jurkat and Jurkat/CEACAM1-4L cells were transfected with an N-terminal deletion of β-catenin (ΔN90) that has constitutive activity due to the absence of the N-terminal Ser residues that can be phosphorylated by GSK3β in many cell lines (46, 47). In this experiment, the reporter activity was decreased by 25% in the Jurkat/CEACAM1-4L vs. the Jurkat control cells. Thus, CEACAM1-4L can reduce the activity of both endogenously expressed β-catenin, and to a lesser extent, constitutively active β-catenin.

Figure 5.

Effect of CEACAM1-4L on reporter assays. Jurkat or Jurkat/CEACAM1-4L cells were transfected with pCMVβ (transfection control) and either pTOPFLASH (shaded bars) or pFOP-FLASH (negative control, open bars) and luciferase activity measured after normalization to β-galactosidase activity. As a positive control, Jurkat or Jurkat/CEACAM1-4L cells were also transfected with an N-terminal deletion mutant of β-catenin (ΔN90-β-catenin) that is constitutively active. Results shown are for triplicate assays: *(P < .05), **(P < .005).

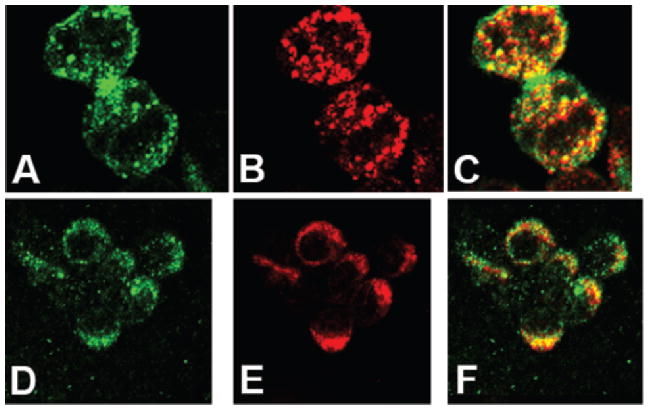

Confocal Analysis of CEACAM1-4L–β-Catenin Interactions

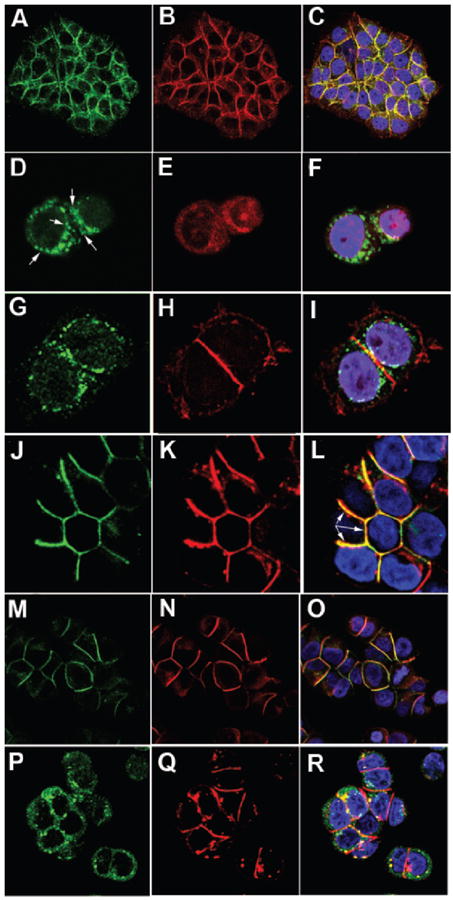

To further test the interaction of CEACAM1-4L with β-catenin in vivo, we used cell transfection assays and examined the co-localization of either CEACAM1-4L or the CEACAM1-4L/eGFP fusion protein with β-catenin. Previously, we have shown that the eGFP fusion protein is expressed at the plasma membrane and inhibits cell proliferation in transfected Jurkat cells (11). In all cases, clones were selected based on their high level of surface expression of the transfected gene (data not shown). Jurkat cells were selected for these studies because of their high level expression of β-catenin and their lack of expression of CEACAM1 and E-cadherin, thus offering the opportunity to observe the effects of forced expression of CEACAM1 on β-catenin co-localization. Jurkat/CEACAM1-4L/eGFP transfectants stained with anti- β-catenin antibodies co-localized with CEACAM1 in punctate microdomains on the cell surface (Fig. 6A–C). Apparent exceptions were areas where two cells contacted leading to a higher concentration of CEACAM1 than β-catenin between cells.

Figure 6.

Co-localization of CEACAM1-4L with β-catenin in Jurkat cells transfected with CEACAM1-4L/eGFP and in activated T-cells. A–C. Jurkat cells transfected with CEACAM1-4L/eGFP were grown on fibronectin coated slides overnight and stained with TRITC conjugated anti-β-catenin antibodies (A, green channel; B, red channel; C, merged). D–F. PBMCs were activated with PHA for 2 d and IL-2 for 10–14 d and then grown on fibronectin coated sides overnight and stained with anti-CEACAM1 antibody 22–9 plus Alexa-488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody and TRITC conjugated anti-β-catenin antibody (D, green channel; E, red channel; F, merged).

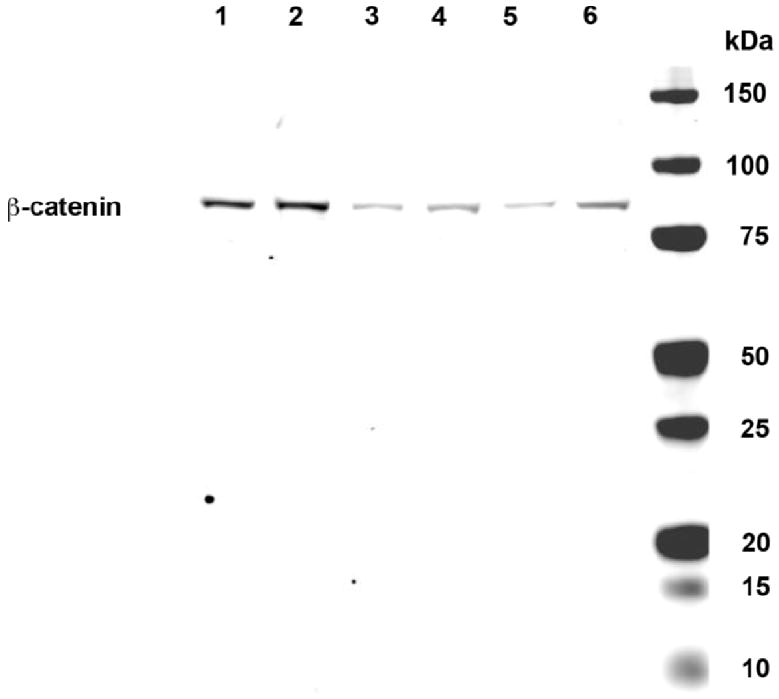

Since Jurkat cells do not express CEACAM1, it was important to examine activated T-cells, cells that normally express CEACAM1 (11, 15). Indeed, the results are similar to those obtained for the CEACAM1 transfected Jurkat cells (Fig. 6D–F). Both proteins are expressed in a punctate pattern on the cell surface with extensive co-localization. Thus, activated T-cells express both proteins and they are found in similar micro-domains. Since the expression of β-catenin in activated PBMCs is weak, we also performed western blot analysis on these cells (Fig. 7). It can be seen that while the amount of β-catenin is low, it is detectable and increased upon treatment with LiCl, an inhibitor of GSK-3β that prevents the destruction of β-catenin. The LiCl results are in agreement with those of Wu et al. (48). In addition, it is known that activated PBMCs do not express E-cadherin, which is itself capable of binding β-catenin (49).

Figure 7.

Expression of β-catenin in activated PBMCs. PBMCs were activated with PHA and IL-2 for 2 d and with IL-2 alone for an additional 10–14 d. Lanes 1, 3, and 5 and lanes 2, 4 and 6 are PBMC samples from two different donors. Samples in lane 1 and 2 were treated with 10mM LiCl for 1h before lysis, samples in lanes 3 and 4 were treated with 10 mM NaCl, and samples in lanes 5 and 6 were untreated. After treatment, cells were washed once with PBS, lysed, proteins separated on SDS gels, and western blotted for β-catenin.

A second model system that employs β-catenin for control of proliferation and has a distinctive cytoplasmic vs. nuclear localization pattern is found in breast cancer epithelial cells. For example, MCF7 cells express high levels of β-catenin but no CEACAM1, and grow normally on plastic when transfected with CEACAM1-4L (17). However, they express high amounts of E-cadherin, a protein known to associate with β-catenin, and which otherwise should inhibit the transcriptional activity of β-catenin. When MCF7 cells are stained for β-catenin and E-cadherin, the two proteins co-localize at cell-cell boundaries (Fig. 8A–C and (50)). This situation presents a dilemma for demonstrating co-localization of CEACAM1 and β-catenin, since CEACAM1 also is found at cell-cell boundaries when expressed in epithelial cells. In order to distinguish the two, MCF7 cells transfected with CEACAM1-4L were grown in calcium free media for 1–2 days and then stained for CEACAM1 and β-catenin. Under these conditions the ability of E-cadherin to make cell-cell junctions and to interact with β-catenin is greatly reduced (Fig. 8D–F and (51)). However, when these cells are transfected with CEACAM1-4L, the co-localization of E-cadherin with β-catenin is disrupted at cell-cell boundaries (Fig. 8G–I), in contrast to CEACAM1-4L where the co-localization is evident (Fig. 8J–L). Arrows indicate areas of reduced cell-cell localization in E-cadherin staining due to Ca2+ depletion (Fig. 8D). The fact that CEACAM1-4L remains co-localized with β-catenin at cell-cell junctions even when E-cadherin localization is reduced, is consistent with CEACAM1-β-catenin interactions. As controls, when CEACAM1 and E-cadherin are stained under Ca2+ conditions, co-localization is observed (Fig. 8M–O), while under Ca2+ free conditions, little co-localization is observed (Fig. 8P–R).

Figure 8.

Co-localization of CEACAM1 with β-catenin in MCF7 cells transfected with CEACAM1-4L. MCF7 (A–F) and CEACAM1-4L transfected MCF7 (G–R) cells were either grown in Ca2+ plus (A–C, M–O) or Ca2+ minus media (D–L, P–R), permeabilized, and stained with TRITC conjugated anti-β-catenin (B, E, H, K) and either FITC conjugated anti-E-cadherin antibody (A, D, G, M, P) or anti-CEACAM1 antibody 22–9 plus Alexa-488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (J) or TRITC- conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (N and Q). Controls include staining for E-cadherin (M and P) and CEACAM1 (N and Q) under Ca2+ (M–O) and Ca2+ free (P–R) conditions. The separate green and red channels (left and middle) are shown together with the merged channels (right) that include DAPI (blue) counterstained for nuclei.

Conclusion

When the extracellular domains of CEACAM1-4L interact with each other across cell-cell junctions they transmit signals that include inhibition of cell proliferation (11, 52-55). Signals of this sort have often been connected to the extensively studied β-catenin pathway that includes interactions with the wnt pathway (56) and the E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion pathway (57, 58). It may be that the interaction of β-catenin with CEACAM1 is just as critical to the epithelial cell as E-cadherin, since the loss of CEACAM1 is found more frequently and earlier than E-cadherin in many tumors, including colon, breast, and prostate (13, 59). In the case of colon tumorigenesis, CEACAM1 is down-regulated as early as the hyperplastic polyp stage (88%) and remains down-regulated to the same extent through the classical progression of adenomatous polyps to overt adenocarcinomas (13). In contrast, there is little or no evidence to implicate E-cadherin down-regulation or mutagenesis at the early stages of tumorigenesis in colon cancer. For most epithelial cells, maintenance of the differentiated state involves a balance between proliferation and apoptosis, a function that has been frequently assigned to CEACAM1 (13). For example, in humanized mammary glands in nude mice, CEACAM1-4L expression plays an essential role in lumen formation by inducing apoptosis of the central cells of acini (60). In colon cancer, the early loss of expression of CEACAM1 may adversely affect other cell adhesion molecules like E-cadherin that are lost later in the tumorigenic progression from exerting their protective effect on preventing unrestrained cell proliferation, in agreement with the speculation that loss of genes early in the pathway has a profound effect on tumorigenesis (57). In agreement with this hypothesis, the Ceacam1-/- colon shows increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis with a higher tumor load upon carcinogen-induced colon tumor development (61).

In the current model of T-cell development, β-catenin plays a critical role in the thymic development of thymocytes, and is expressed anew in T-cell leukemias (62). It is noteworthy that in T-cell leukemia cell lines such as Jurkat cells, CEACAM1 is not expressed, and if forcibly expressed, exerts an inhibitory effect on cell proliferation (11). In the work presented here, forcible expression of CEACAM1-4L also results in its co-localization with β-catenin, thus suggesting the possibility that it can interfere with the β-catenin signaling pathway in Jurkat cells. Furthermore, β-catenin and CEACAM1 are expressed together in activated PBMCs, suggesting that they help regulate proliferation in these cells. Taken together, our data indicate that CEACAM1 is a differentiation agent or morphogen in many tissues and that its down-regulation is a common mechanism of tumorigenesis because it impacts on both the β-catenin proliferation and apoptotic pathways.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant CA 84202.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Obrink B. CEA adhesion molecules: multifunctional proteins with signal-regulatory properties. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:616–626. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(97)80114-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blau DM, Turbide C, Tremblay M, Olson M, Letourneau S, Michaliszyn E, Jothy S, Holmes KV, Beauchemin N. Targeted disruption of the Ceacam1 (MHVR) gene leads to reduced susceptibility of mice to mouse hepatitis virus infection. J Virol. 2001;75:8173–8186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8173-8186.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray-Owen SD, Dehio C, Haude A, Grunert F, Meyer TF. CD66 carcinoembryonic antigens mediate interactions between Opa-expressing Neisseria gonorrhoeae and human polymorphonuclear phagocytes. Embo J. 1997;16:3435–3445. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virji M, Evans D, Griffith J, Hill D, Serino L, Hadfield A, Watt SM. Carcinoembryonic antigens are targeted by diverse strains of typable and non-typable Haemophilus influenzae. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:784–795. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulton IC, Gray-Owen SD. Neisserial binding to CEACAM1 arrests the activation and proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Najjar SM. Regulation of insulin action by CEACAM1. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:240–245. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ergun S, Kilik N, Ziegeler G, Hansen A, Nollau P, Gotze J, Wurmbach JH, Horst A, Weil J, Fernando M, Wagener C. CEA-related cell adhesion molecule 1: a potent angiogenic factor and a major effector of vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol Cell. 2000;5:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markel G, Wolf D, Hanna J, Gazit R, Goldman-Wohl D, Lavy Y, Yagel S, Mandelboim O. Pivotal role of CEACAM1 protein in the inhibition of activated decidual lymphocyte functions. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:943–953. doi: 10.1172/JCI15643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kammerer R, Stober D, Singer BB, Obrink B, Reimann J. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 on murine dendritic cells is a potent regulator of T cell stimulation. J Immunol. 2001;166:6537–6544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iijima H, Neurath MF, Nagaishi T, Glickman JN, Nieuwenhuis EE, Nakajima A, Chen D, Fuss IJ, Utku N, Lewicki DN, Becker C, Gallagher TM, Holmes KV, Blumberg RS. Specific regulation of T helper cell 1-mediated murine colitis by CEACAM1. J Exp Med. 2004;199:471–482. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CJ, Shively JE. The cell-cell adhesion molecule carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule 1 inhibits IL-2 production and proliferation in human T cells by association with Src homology protein-1 and down-regulates IL-2 receptor. J Immunol. 2004;172:3544–3552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumaier M, Paululat S, Chan A, Matthaes P, Wagener C. Biliary glycoprotein, a potential human cell adhesion molecule, is down-regulated in colorectal carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10744–10748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nittka S, Gunther J, Ebisch C, Erbersdobler A, Neumaier M. The human tumor suppressor CEACAM1 modulates apoptosis and is implicated in early colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:9306–9313. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Simpson JF, Glackin C, Riethorf L, Wagener C, Shively JE. Expression of biliary glycoprotein (CD66a) in normal and malignant breast epithelial cells. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:3203–3212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kammerer R, Hahn S, Singer BB, Luo JS, von Kleist S. Biliary glycoprotein (CD66a), a cell adhesion molecule of the immunoglobulin superfamily, on human lymphocytes: structure, expression and involvement in T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3664–3674. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3664::AID-IMMU3664>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J, Hardy JD, Sun Y, Shively JE. Essential role of biliary glycoprotein (CD66a) in morphogenesis of the human mammary epithelial cell line MCF10F. J Cell Science. 1999;112:4193–4205. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirshner J, Chen CJ, Liu P, Huang J, Shively JE. CEACAM1-4S, a cell-cell adhesion molecule, mediates apoptosis and reverts mammary carcinoma cells to a normal morphogenic phenotype in a 3D culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:521–526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232711199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beauchemin N, Kunath T, Robitaille J, Chow B, Turbide C, Daniels E, Veillette A. Association of biliary glycoprotein with protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in malignant colon epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:783–790. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skubitz KM, Ducker TP, Skubitz AP, Goueli SA. Antiserum to carcinoembryonic antigen recognizes a phosphotyrosine-containing protein in human colon cancer cell lines. FEBS Lett. 1993;318:200–204. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80021-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber M, Izzi L, Grondin P, Houde C, Kunath T, Veillette A, Beauchemin N. The carboxyl-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein-tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:335–344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagaishi T, Pao L, Lin SH, Iijima H, Kaser A, Qiao SW, Chen Z, Glickman J, Najjar SM, Nakajima A, Neel BG, Blumberg RS. SHP1 phosphatase-dependent T cell inhibition by CEACAM1 adhesion molecule isoforms. Immunity. 2006;25:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagaishi T, Iijima H, Nakajima A, Chen D, Blumberg RS. Role of CEACAM1 as a regulator of T cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1072:155–175. doi: 10.1196/annals.1326.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nollau P, Scheller H, Kona-Horstmann M, Rohde S, Hagenmuller F, Wagener C, Neumaier M. Expression of CD66a (human C-CAM) and other members of the carcinoembryonic antigen gene family of adhesion molecules in human colorectal adenomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2354–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo W, Tapolsky M, Earley K, Wood CG, Wilson DR, Logothetis CJ, Lin SH. Tumor-suppressive activity of CD66a in prostate cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6:313–321. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo W, Wood CG, Earley K, Hung MC, Lin SH. Suppression of tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells by an epithelial cell adhesion molecule (C-CAM1): the adhesion and growth suppression are mediated by different domains. Oncogene. 1997;14:1697–1704. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinerman DI, Dinney CP, Zhang WW, Lin SH, Van NT, Hsieh JT. Suppression of human bladder cancer growth by increased expression of C-CAM1 gene in an orthotopic model. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3431–3435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunath T, Ordonez-Garcia C, Turbide C, Beauchemin N. Inhibition of colonic tumor cell growth by biliary glycoprotein. Oncogene. 1995;11:2375–2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brummer J, Neumaier M, Gopfert C, Wagener C. Association of pp60c-src with biliary glycoprotein (CD66a), an adhesion molecule of the carcinoembryonic antigen family downregulated in colorectal carcinomas. Oncogene. 1995;11:1649–1655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skubitz KM, Campbell KD, Ahmed K, Skubitz AP. CD66 family members are associated with tyrosine kinase activity in human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1995;155:5382–5390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumann D, Chen C-J, Kaplan B, Shively JE. Carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1 directly associates with cytoskeleton proteins actin and tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47421–47433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edlund M, Blikstad I, Obrink B. Calmodulin binds to specific sequences in the cytoplasmic domain of C-CAM and down-regulates C-CAM self association. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1393–1399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirshner J, Schumann D, Shively JE. CEACAM1, a cell-cell adhesion molecule, directly associates with annexin II in a three-dimensional model of mammary morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50338–50345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klaile E, Muller MM, Kannicht C, Singer BB, Lucka L. CEACAM1 functionally interacts with filamin A and exerts a dual role in the regulation of cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5513–5524. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebrahimnejad A, Flayeh R, Unteregger G, Wagener C, Brummer J. Cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1 associates with paxillin in granulocytes and epithelial and endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;260:365–373. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller MM, Singer BB, Klaile E, Obrink B, Lucka L. Transmembrane CEACAM1 affects integrin-dependent signaling and regulates extracellular matrix protein-specific morphology and migration of endothelial cells. Blood. 2005;105:3925–3934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klaile E, Muller MM, Kannicht C, Otto W, Singer BB, Reutter W, Obrink B, Lucka L. The cell adhesion receptor carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 regulates nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of DNA polymerase delta-interacting protein 38. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26629–26640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701807200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barker N, Clevers H. Catenins, Wnt signaling and cancer. Bioessays. 2000;22:961–965. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200011)22:11<961::AID-BIES1>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huber AH, Weis WI. The structure of the beta-catenin/E-cadherin complex and the molecular basis of diverse ligand recognition by beta-catenin. Cell. 2001;105:391–402. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poy F, Lepourcelet M, Shivdasani RA, Eck MJ. Structure of a human Tcf4-beta-catenin complex. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/nsb720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graham TA, Weaver C, Mao F, Kimelman D, Xu W. Crystal structure of a beta-catenin/Tcf complex. Cell. 2000;103:885–896. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638–642. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fasolini M, Wu X, Flocco M, Trosset JY, Oppermann U, Knapp S. Hot spots in Tcf4 for the interaction with beta-catenin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21092–21098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung EJ, Hwang SG, Nguyen P, Lee S, Kim JS, Kim JW, Henkart PA, Bottaro DP, Soon L, Bonvini P, Lee SJ, Karp JE, Oh HJ, Rubin JS, Trepel JB. Regulation of leukemic cell adhesion, proliferation, and survival by beta-catenin. Blood. 2002;100:982–990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Y, Kolligs FT, Hottiger MO, Mosavin R, Fearon ER, Nabel GJ. Regulation of beta-catenin transformation by the p300 transcriptional coactivator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12613–12618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220158597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang HW, Aoki M, Fruman D, Auger KR, Bellacosa A, Tsichlis PN, Cantley LC, Roberts TM, Vogt PK. Transformation of chicken cells by the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase. Science. 1997;276:1848–1850. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aoki M, Sobek V, Maslyar DJ, Hecht A, Vogt PK. Oncogenic transformation by beta-catenin: deletion analysis and characterization of selected target genes. Oncogene. 2002;21:6983–6991. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu B, Crampton SP, Hughes CC. Wnt signaling induces matrix metalloproteinase expression and regulates T cell transmigration. Immunity. 2007;26:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cepek KL, Rimm DL, Brenner MB. Expression of a candidate cadherin in T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6567–6571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu Y, Leo C, Yu S, Huang BC, Wang H, Shen M, Luo Y, Daniel-Issakani S, Payan DG, Xu X. Identification and functional characterization of a novel human misshapen/Nck interacting kinase-related kinase, hMINK beta. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54387–54397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peignon G, Thenet S, Schreider C, Fouquet S, Ribeiro A, Dussaulx E, Chambaz J, Cardot P, Pincon-Raymond M, Le Beyec J. E-cadherin-dependent transcriptional control of apolipoprotein A-IV gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells: a role for the hepatic nuclear factor 4. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3560–3568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo W, Earley K, Tantingco V, Hixson DC, Liang TC, Lin SH. Association of an 80 kDa protein with C-CAM1 cytoplasmic domain correlates with C-CAM1-mediated growth inhibition. Oncogene. 1998;16:1141–1147. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abou-Rjaily GA, Lee SJ, May D, Al-Share QY, Deangelis AM, Ruch RJ, Neumaier M, Kalthoff H, Lin SH, Najjar SM. CEACAM1 modulates epidermal growth factor receptor—mediated cell proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:944–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI21786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu Q, Chow EM, Wong H, Gu J, Mandelboim O, Gray-Owen SD, Ostrowski MA. CEACAM1 (CD66a) promotes human monocyte survival via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- and AKT-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39179–39193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scheffrahn I, Singer BB, Sigmundsson K, Lucka L, Obrink B. Control of density-dependent, cell state-specific signal transduction by the cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1, and its influence on cell cycle regulation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mulholland DJ, Dedhar S, Coetzee GA, Nelson CC. Interaction of nuclear receptors with the Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling axis: Wnt you like to know? Endocr Rev. 2005;26:898–915. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shively JE. CEACAM1 and hyperplastic polyps: new links in the chain of events leading to colon cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:9303–9305. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gooding JM, Yap KL, Ikura M. The cadherin-catenin complex as a focal point of cell adhesion and signalling: new insights from three-dimensional structures. Bioessays. 2004;26:497–511. doi: 10.1002/bies.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Comegys MM, Carreiro MP, Brown JF, Mazzacua A, Flanagan DL, Makarovskiy A, Lin SH, Hixson DC. C-CAM1 expression: differential effects on morphology, differentiation state and suppression of human PC-3 prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:3261–3276. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yokoyama S, Chen CJ, Nguyen T, Shively JE. Role of CEACAM1 isoforms in an in vivo model of mammary morphogenesis: mutational analysis of the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1-4S reveals key residues involved in lumen formation. Oncogene. 2007;26:7637–7646. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leung N, Turbide C, Olson M, Marcus V, Jothy S, Beauchemin N. Deletion of the carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (Ceacam1) gene contributes to colon tumor progression in a murine model of carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2006;25:5527–5536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dorfman DM, Greisman HA, Shahsafaei A. Loss of expression of the WNT/beta-catenin-signaling pathway transcription factors lymphoid enhancer factor-1 (LEF-1) and T cell factor-1 (TCF-1) in a subset of peripheral T cell lymphomas. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1539–1544. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64287-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.