Abstract

Reovirus, a member of the Reoviridae family, is a ubiquitous virus in vertebrate hosts. Although disease caused by reovirus infection is for the most part mild, studies of reovirus have been particularly valuable as a model for understanding the local host response to replicating foreign antigen in intestinal and respiratory sites. In this article, a brief overview is presented of the basic features of reovirus infection, as will the host’s humoral and cellular immune response to during the infectious cycle. New information regarding the interactions and involvement of immune response molecules during reovirus infection will be presented based on multiple analyte array studies from our laboratory.

Keywords: Analyte, Effector, Intestine, IEL, Viral

Introduction

Reovirus is a non-enveloped virus made up of segmented double-stranded RNA inside a double-layered capsid shell [1, 2]. Three serotypes have been defined for reovirus, designated serotype 1 (prototype Lang strain), serotype 2 (prototype Jones strain), and serotype 3 (prototype Dearing strain). The outer capsid consists of both structural and non-structural polypeptides [3, 4]. The σ1 hemagglutinin, a structural capsid molecule, has been linked to many virus associated activities, including host cell attachment, viral neutralization by antibody, recognition by cytotoxic T cells, and tissue tropism and pathogenesis of reovirus-mediated diseases [5–16]. Core proteins consist of transcriptases and replicases used in viral replication.

Virus infectivity by reovirus spans a wide range of vertebrate species [17–19], and the virus has served well as an experimental system for studying the dynamics of acute enteric and respiratory virus infection in laboratory animals. Differences have been reported in regional areas of infectivity in the small intestine using reovirus serotype 1 versus serotype 3, with serotype 1 primarily infecting epithelial cells and serotype 3 infecting intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) [20–25]. In both cases, however, entry of the virus appears to occur through Peyer’s patches, most likely via M cells [26]. Following oral infection, the virus may spread to mesenteric lymph nodes [27] and may disseminate and penetrate into many tissues, including the liver [28, 29], pancreas [5, 30], and endocrine tissues [31], as well as muscle [32] and heart tissue [33–35]. Age-associated susceptibility to reovirus serotype 3 leading to fatal encephalitis has been reported, the effect of which does not appear to be mediated by immunological factors but most likely reflect developmental conditions of neural tissues [36]. An autoimmune diabetes has been described following reovirus infection in mice [37], and human pancreatic beta cells are susceptible to in vitro reovirus infection [38].

Humoral and Cellular Immunity to Reovirus

Both neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies develop following reovirus infection [39–42]. The hemagglutinin σ1 protein is the primary target molecule of neutralizing antibodies [43–45] as seen from studies using cloned S1 gene products recognized by monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies [45]. Moreover, cloning of S1 gene cDNA in E. coli, resulting in a fusion protein with hemagglutinating activity and binding capacity to L cells [46], and analysis using mutant σ1 proteins, revealed that viral domains differ with regard to their tissue binding capacities and hemagglutinating activities [46]. Likewise, site-directed mutagenesis of the S1 gene has identified conserved attachment sites of the σ1 protein with the location of greatest activity in the c-terminal portion [47]. Antibodies to the σ1 protein have been shown to prevent the spread of reovirus serotype 3 to the CNS and to protect against lethal disease [44, 48]. In studies using reovirus serotypes 1 and 3, infection of the P388D1 macrophage cell line was enhanced in the presence of non-neutralizing antibody or with neutralizing antibody at low concentrations, an effect presumably due to endocytosis of virus-antibody complexes following Fc receptor capture by cells [49]. Recent studies have demonstrated a role for IgG and IgA antibodies directed to σ1 protein in in vivo protection against Peyer’s patch (PP) infection when antibody was administered orally with infectious virus. In contrast, only IgA effectively blocked infection when secreted from subcutaneous hybridoma tumors, a system that would more closely mimic systemic antibody dissemination [50]. The route of infection influences the immunoglobulin isotype generated. This is seen in studies in which oral reovirus exposure leading to infection of PP stimulated IgA synthesis while intradermal virus infection elicited IgG from lymph node cells [39]. IgG was present in the serum of mice following either oral or intradermal infection [39].

Finberg and colleagues provided the first evidence that MHC-restricted, reovirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) generated from reovirus-infected mice infected with reovirus serotypes 1 or 3 [8], and to demonstrate that anti-reovirus CTL respond to the σ1 hemagglutinin [8]. Subsequent studies have confirmed a role for CTL in the anti-reovirus immune response [42, 51–54]. However, there appears to be a significant degree of cross-reactivity of CTL raised to serotype 1 or 3 [52–54]. Additionally, studies of CTL specificities using vaccinia virus-reovirus recombinant constructs indicate both strain specific and cross-reacting CTL directed to the σ1 non-structural capsid protein [52].

TCRαβ T cells appear to account for most reovirus-specific CTL; the role of γδ T cells in the immune response to reovirus has not been thoroughly explored. T CTL Vβ repertoire appears to be skewed in favor of Vβ6, Vβ, 12, and Vβ17, although Vβ2, Vβ7, Vβ9, and Vβ14 also may participate in the response to reovirus [55, 56]. Interestingly, the Jβ gene segment of Vβ6 TCR clones expanded in SCID mice showed more restricted Jβ gene usage in orally-infected mice versus systemically-infected animals [55], implying that repertoire selection of anti-reoviral T cells is dictated in part by the route of viral entry. Using a germinal center/T cell marker (GCT), London and colleagues reported an increase in GCT+, Thy-1+, CD8+ IELs and lamina propria lymphocytes (LPL) bearing CD11c, a marker of T cell activation in the gut [57], in mice infected intraduodenally with serotype 1 reovirus T1L [58]. Modest differences also were noted in the cytotoxic activities mediated via perforin, FasL, and TRAIL for PP lymphocytes, IELs, and LPLs [58]. Local dendritic cells play a clear role in determining the outcome of virus delivery within mucosal tissues, leading either to immune tolerance or lymphoid activation [59–61]. Moreover, CD11c+, CD8α+ DCs in PP subepithelial dome contribute to CD4+ T cell priming by viral antigen cross-presentation [59].

A role for the immune response in curtailing the reovirus infectious process is also evident from studies using severe-combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, which develop a systemic reovirus infection leading to death of the host [62]. Protection of SCID mice can be achieved upon adoptive transfer of PP cells from immune animals [62]. Interestingly, the role for NK cells during virus infection is unclear. Given that SCID mice, which have significant numbers of NK cells despite a lack of mature functional T cells, are susceptible to reovirus infection [62], it would appear that adaptive immune elements play a necessary and indispensable role in curtailing the spread of virus. Yet, studies using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells demonstrate in vitro lysis of reovirus-infected K562 NK-sensitive target cells, the activity of which is influenced by IL-15 [63]. Moreover, reovirus infection is a potent inducer of NK cell activity in mice [64], and some anti-reovirus CTL express the asialo GM1 marker commonly found on NK cells; however, those cells were not lytic for NK-sensitive target cells [65], suggesting that they conform most closely to conventional CTL. Thus, it appears that both NK cells and CTL are needed for the development of an adequate immune response, with NK cells being required early during the infectious cycle and the classical adaptive cellular immune response mediated by CTL being essential late in the cycle. In the absence of either of those, viral infection is not adequately controlled.

Immunoregulatory and Effector Cytokines during Reovirus Infection – Analysis using Multiple Analyte Arrays

Information remains incomplete about the role played by immune regulatory cytokines and chemokines in the local host immune response to reovirus infection. Studies of cytokine production by mice following oral infection with serotype 1 reovirus characterize elevated levels of gene expression for IFN-γ in PP lymphocytes and IELs, and synthesis of IL-5, IL-6, and IFN-γ from cultured PP cells of reovirus infected mice [66]. Differences also exist in the levels of IFN-γ produced by lymph node cells following intradermal infection, with C3H mice being high producers and BALB/c, C57BL/6, and B10.D2 mice being low responders [39]. IFN-γ and IL-12 mRNA levels increase in draining popliteal or mesenteric lymph nodes following footpad or oral infection with reovirus serotype 1, respectively [67].

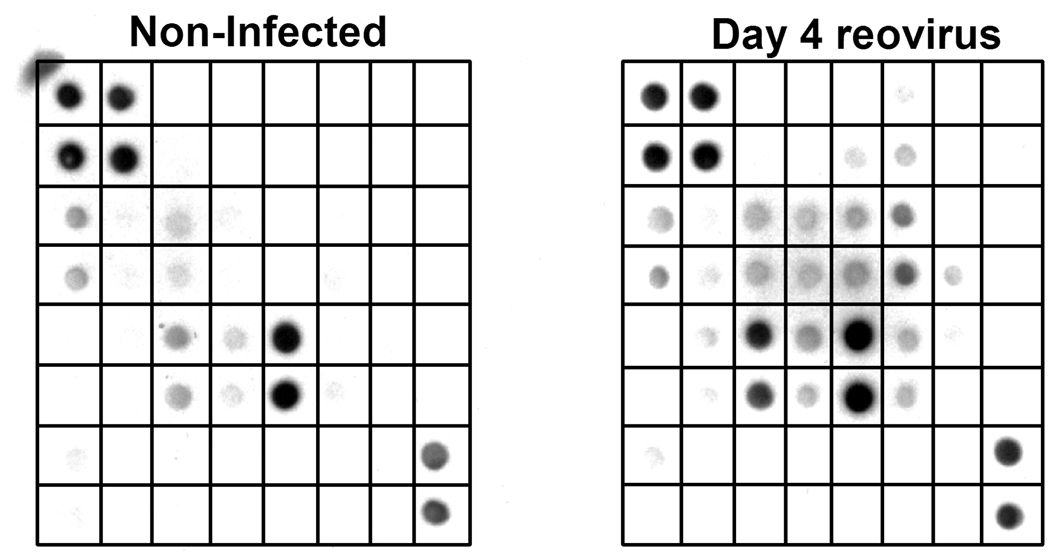

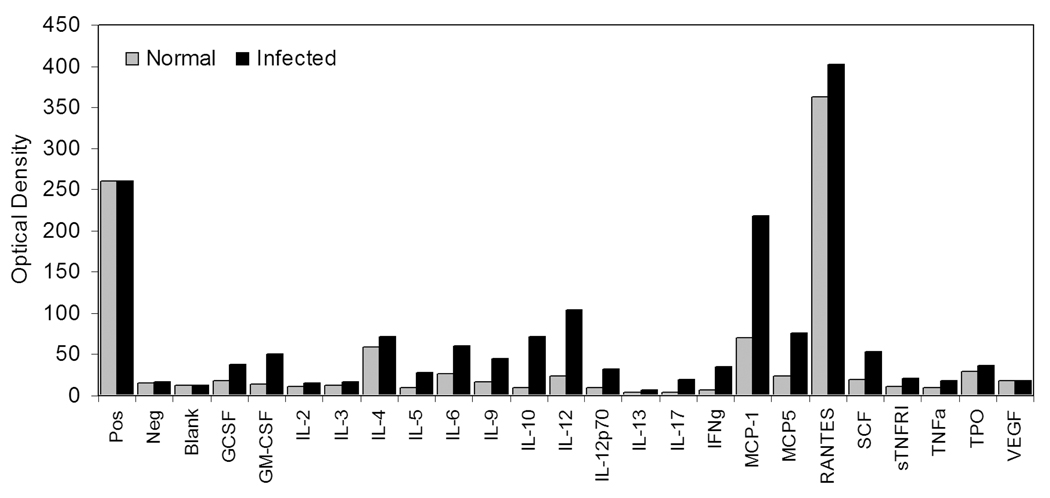

In an effort to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the involvement of regulatory and effector molecules in the response to reovirus infection, we initiated a series of studies aimed at defining changes that take place in cytokine and chemokine activities in intestinal tissues using a system for simultaneously evaluating twenty-two immune regulatory and effector immune response molecules. Mice were infected with 107.5 reovirus type 3 Dearing strain by oral gavage. Previous studies from our laboratory using real-time PCR indicate that virus infection peaked in the small intestine between days 4–7 post infection [68]. On day 4 post-infection, IELs were isolated and cultured overnight in serum-free tissue culture medium. Cell-free supernatants were recovered and reacted with commercial membranes (RayBiotech, Inc; Norcross, GA) that measure the activity of the twenty-two analytes shown in Table 1. The results of these findings are shown in Fig. 1 for IELs from non-infected mice and from mice after 4 days of reovirus infection. Note the increase in activity of a number of analytes in IELs from virus-infected mice compared to IELs from non-infected animals. After normalization of the data using positive controls included with the membranes, the data are displayed graphically as seen in Fig. 2, allowing direct comparisons and quantification of the changes in analyte values that cannot be directly determined by visual inspection but are quantifiable based on optical density, thus revealing numerous analyte changes during infection.

Table 1.

Template for Protein Array Grids

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | GCSF | GM-CSF | IL-2 | IL-3 |

| 2 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | GCSF | GM-CSF | IL-2 | IL-3 |

| 3 | IL-4 | IL-5 | IL-6 | IL-9 | IL-10 | IL-12 | IL-12p70 | IL-13 |

| 4 | IL-4 | IL-5 | IL-6 | IL-9 | IL-10 | IL-12 | IL-12p70 | IL-13 |

| 5 | IL-17 | IFN-γ | MCP-1 | MCP-5 | RANTES | SCF | sTNFRI | TNF-α |

| 6 | IL-17 | IFN-γ | MCP-1 | MCP-5 | RANTES | SCF | sTNFRI | TNF-α |

| 7 | TPO | VEGF | Blank | Blank | Blank | Blank | Blank | Pos |

| 8 | TPO | VEGF | Blank | Blank | Blank | Blank | Blank | Pos |

Fig. 1.

Analysis of twenty-two immune response analytes produced by IELs from non-infected mice and IELs from mice 4 days after reovirus infection. Note the increase in synthesis of analytes in infected mice compared to non-infected animals. See Table 1 for identification of analytes in blot grids.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of data from Fig. 1 after normalization using the positive and negative control values provided with the blotting membranes.

What do these findings tell us about the natural intestinal immune response to reovirus? It is clear that virus infection leads to a complex but selective pattern of expression of immune response molecules produced by intestinal IELs. This can be seen in Table 2, in which analytes have been grouped based on whether they had a >2-fold or <2-fold change in analyte levels relative to that of normal IELs. Of the analytes showing elevated changes, several are characterized by their strong inflammatory activities (IL-6, IL-12, IFN-γ), or as analytes that are used in T cell activation, e.g., IL-17 and SCF. Upregulation of activity for colony-stimulating factors (GSCF and GM-CSF) and monocyte chemoattractant proteins (MCP-1 a n d MCP-5) point to a process of mobilization and/or cell proliferation of dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages during the height of infection. Stem cell factor (SCF) would be used in the expansion/development of intestinal T cells during infection [69]. Collectively, the composite effects of those analytes in the host response to enteric virus infection would predictably lead to a strong cell-mediated immune response on day 4 of infection, a time when virus is wide-spread [68].

Table 2.

Changes in Analyte Levels in Intestinal IELs from Day 4 Reovirus-infected Mice

| Fold change >2.0 |

Fold change <2.0 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Analyte | Fold | Analyte | Fold |

| GCSF | 2.1 | IL-2 | 1.3 |

| GM-CSF | 3.5 | IL-3 | 1.2 |

| IL-5 | 3.0 | IL-4 | 1.1 |

| IL-6 | 2.2 | IL-13 | 1.7 |

| IL-9 | 2.6 | RANTES | 1.1 |

| IL-10 | 7.3 | sTNFR1 | 1.8 |

| IL-12 | 4.4 | TNFα | 1.7 |

| IL-12p70 | 3.3 | TPO | 1.2 |

| IL-17 | 4.0 | VEGF | 1.0 |

| IFN-γ | 5.9 | ||

| MCP-1 | 3.0 | ||

| MCP-5 | 3.1 | ||

| SCF | 2.6 | ||

An additional novel finding from these studies pertains to the high level of IL-10 production by reovirus-infected IELs compared to IELs from non-infected mice (Table 2). Interestingly, other studies have described suppressed IL-10 activity in PP of mice infected with reovirus serotype 1 [67]. Those differences may reflect the fact that our studies were done using IELs from intestinal tissues after removal of PPs, or alternatively that virus strain differences influence the outcome of IL-10 production in the small intestine. Nonetheless, it may be of value to re-evaluate the relative contributions of PP cells and IELs to the overall host response to reovirus. Regardless, the data shown in Table 2 for IL-10 imply that the immune response to virus proceeds in the face of a significant level of immunological control. Although this may appear to be intuitively obvious, studies that examine regulatory and effector cytokines individually, without the benefit of a holistic integrative analysis provided by multiple analyte determinations, are likely to miss this connection. Indeed, further studies using multiple analyte systems will undoubtedly provide new insight into the totality of the immune response at the level of the intestinal mucosa.

Information derived from the nine analytes that had <2-fold changes compared to normal mice are equally revealing. Both IL-2 and IL-4, cytokines that exert proliferative effects on lymphocytes, were only modestly elevated during infection — at least at day 4 post-infection. On the one hand, this could be indicative of a temporal effect such that the greatest level of proliferation mediated by IL-2 and IL-4 may have already occurred prior to day 4. It should be noted that IL-4 was present in significant levels in non-infected mice (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), possibly indicating an ongoing process of IL-4 synthesis in the small intestine due to a homeostatic process of T cell and/or B cell expansion in the small intestine. Likewise, RANTES (CCL5) expression, though not appreciably elevated in virus-infected mice, was nonetheless one of the analytes having the greatest activity in array blots of both non-infected and infected mice (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). That pattern is consistent with RANTES being synthesized by resting T cells and with the elevation of RANTES secretion following T cell activation. If IELs are activated or partially-activated T cells, as has been predicted [70–72], background levels of RANTES would already be high, masking changes that occur in RANTES production by anti-viral T cells during the infection cycle.

Where to from Here?

It will be particularly interesting to conduct similar analyte expression studies at temporal intervals during the course of reovirus infection, and to conduct analyte studies within selected areas of the intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and regional Peyer’s patches). An obvious void in our knowledge of the reovirus infectious process concerns the lack of information about the natural history of the virus throughout the intestine following exposure. Where, for example, does the virus reside following oral ingestion? Is the virus uniformly or randomly distributed in intestinal tissue sites? Are there changes in the location of virus infection across time? If so, what accounts for those changes? What is the nature of the local site-specific immune response as virus infection proceeds? These are a few of the fundamentally-important issues that bear directly on issues pertaining to the manipulation of the host immune response through vaccination or therapy, and they are central to our understanding of how the intestinal immune system responds to a replicating foreign antigen in general.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant DK35566 and by a grant DK56338 to the Gulf Coast Digestive Disease Center.

References

- 1.Mayor HD, Jamison RM, Jordan LE, Vanmitchell M. Reoviruses. Ii. Structure and Composition of the Virion. J Bacteriol. 1965;89:1548–1556. doi: 10.1128/jb.89.6.1548-1556.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RE, Zweerink HJ, Joklik WK. Polypeptide components of virions, top component and cores of reovirus type 3. Virology. 1969;39(4):791–810. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer EL, Martin ML. The fine structure of the capsid of reovirus type 3. Virology. 1977;76(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasquez C, Tournier P. The morphology of reovirus. Virology. 1962;17:503–510. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(62)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onodera T, Toniolo A, Ray UR, Jenson AB, Knazek RA, Notkins AL. Virus-induced diabetes mellitus. XX. Polyendocrinopathy and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1981;153(6):1457–1473. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.6.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner HL, Drayna D, Averill DR, Jr, Fields BN. Molecular basis of reovirus virulence: role of the S1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74(12):5744–5748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finberg R, Weiner HL, Burakoff SJ, Fields BN. Type-specific reovirus antiserum blocks the cytotoxic T-cell-target cell interaction: evidence for the association of the viral hemagglutinin of a nonenveloped virus with the cell surface. Infect Immun. 1981;31(2):646–649. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.646-649.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finberg R, Weiner HL, Fields BN, Benacerraf B, Burakoff SJ. Generation of cytolytic T lymphocytes after reovirus infection: role of S1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76(1):442–446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner HL, Fields BN. Neutralization of reovirus: the gene responsible for the neutralization antigen. J Exp Med. 1977;146(5):1305–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.5.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee PW, Hayes EC, Joklik WK. Protein σ1 is the reovirus cell attachment protein. Virology. 1981;108(1):156–163. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90535-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner HL, Ault KA, Fields BN. Interaction of reovirus with cell surface receptors. I. Murine and human lymphocytes have a receptor for the hemagglutinin of reovirus type 3. J Immunol. 1980;124(5):2143–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finberg R, Spriggs DR, Fields BN. Host immune response to reovirus: CTL recognize the major neutralization domain of the viral hemagglutinin. J Immunol. 1982;129(5):2235–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spriggs DR, Bronson RT, Fields BN. Hemagglutinin variants of reovirus type 3 have altered central nervous system tropism. Science. 1983;220(4596):505–507. doi: 10.1126/science.6301010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nepom JT, Weiner HL, Dichter MA, et al. Identification of a hemagglutinin-specific idiotype associated with reovirus recognition shared by lymphoid and neural cells. J Exp Med. 1982;155(1):155–167. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner HL, Powers ML, Fields BN. Absolute linkage of virulence and central nervous system cell tropism of reoviruses to viral hemagglutinin. J Infect Dis. 1980;141(5):609–616. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyler KL, Bronson RT, Byers KB, Fields B. Molecular basis of viral neurotropism: experimental reovirus infection. Neurology. 1985;35(1):88–92. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFerran JB, Connor TJ, McCracken RM. Isolation of adenoviruses and reoviruses from avian species other than domestic fowl. Avian Dis. 1976;20(3):519–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belak S, Palfi V. Isolation of reovirus type 1 from lambs showing respiratory and intestinal symptoms. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch. 1974;44(3):177–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott FW, Kahn DE, Gillespie JH. Feline viruses: isolation, characterization, and pathogenicity of a feline reovirus. Am J Vet Res. 1970;31(1):11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharpe AH, Fields BN. Pathogenesis of viral infections. Basic concepts derived from the reovirus model. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(8):486–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502213120806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keroack M, Fields BN. Viral shedding and transmission between hosts determined by reovirus L2 gene. Science. 1986;232(4758):1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.3012780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiner DB, Girard K, Williams WV, McPhillips T, Rubin DH. Reovirus type 1 and type 3 differ in their binding to isolated intestinal epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. 1988;5(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodkin DK, Fields BN. Growth and survival of reovirus in intestinal tissue: role of the L2 and S1 genes. J Virol. 1989;63(3):1188–1193. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1188-1193.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DH, Fields BN. Molecular basis of reovirus virulence. Role of the M2 gene. J Exp Med. 1980;152(4):853–868. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.4.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin DH, Kornstein MJ, Anderson AO. Reovirus serotype 1 intestinal infection: a novel replicative cycle with ileal disease. J Virol. 1985;53(2):391–398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.2.391-398.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf JL, Kauffman RS, Finberg R, Dambrauskas R, Fields BN, Trier JS. Determinants of reovirus interaction with the intestinal M cells and absorptive cells of murine intestine. Gastroenterology. 1983;85(2):291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kauffman RS, Wolf JL, Finberg R, Trier JS, Fields BN. The sigma 1 protein determines the extent of spread of reovirus from the gastrointestinal tract of mice. Virology. 1983;124(2):403–410. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DH, Costello T, Witzleben CL, Greene MI. Transport of infectious reovirus into bile: class II major histocompatibility antigen-bearing cells determine reovirus transport. J Virol. 1987;61(10):3222–3226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3222-3226.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papadimitriou JM. Electron micrographic features of acute murine reovirus hepatitis. Am J Pathol. 1965;47(4):565–585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onodera T, Jenson AB, Yoon JW, Notkins AL. Virus-induced diabetes mellitus: reovirus infection of pancreatic beta cells in mice. Science. 1978;201(4355):529–531. doi: 10.1126/science.208156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srinivasappa J, Garzelli C, Onodera T, Ray U, Notkins AL. Virus-induced thyroiditis. Endocrinology. 1988;122(2):563–566. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-2-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassan SA, Rabin ER, Melnick JL. Reovirus Myocarditis in Mice: an Electron Microscopic, Immunofluorescent, and Virus Assay Study. Exp Mol Pathol. 1965;76:66–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(65)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baty CJSB. Cytypathic effect in cardiac myocytes but not in cardiac fibroblasts is correlated with reovirus-induced acute myocarditis. J Virol. 1993;67:6295–6298. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6295-6298.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherry B, Li XY, Tyler KL, Cullen JM, Virgin HWt. Lymphocytes protect against and are not required for reovirus-induced myocarditis. J Virol. 1993;67(10):6119–6124. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6119-6124.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherry B. Pathogenesis of reovirus myocarditis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;223:51–66. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72095-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tardieu M, Powers ML, Weiner HL. Age dependent susceptibility to Reovirus type 3 encephalitis: role of viral and host factors. Ann Neurol. 1983;13(6):602–607. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jun HS, Yoon JW. A new look at viruses in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2003;19(1):8–31. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon JW, Selvaggio S, Onodera T, Wheeler J, Jenson AB. Infection of cultured human pancreatic B cells with reovirus type 3. Diabetologia. 1981;20(4):462–467. doi: 10.1007/BF00253408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Major AS, Cuff CF. Effects of the route of infection on immunoglobulin G subclasses and specificity of the reovirus-specific humoral immune response. J Virol. 1996;70:5968–5974. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5968-5974.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen D, Rubin DH. Mucosal T cell response to reovirus. Immunol Res. 2001;23:229–234. doi: 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Virgin HW, Dermody TS, Tyler KL. Cellular and humoral immunity to reovirus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;233:147–161. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72095-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fulton JR, Cuff CF. Mucosal and systemic immunity to intestinal reovirus infection in aged mice. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helander A, Miller CL, Myers KS, Neutra MR, Nibert ML. Protective immunoglobulin A and G antibodies bind to overlapping intersubunit epitopes in the head domain of type 1 reovirus adhesin sigma1. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10695–10705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10695-10705.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyler KL, Virgin HWt, Bassel-Duby R, Fields BN. Antibody inhibits defined stages in the pathogenesis of reovirus serotype 3 infection of the central nervous system. J Exp Med. 1989;170(3):887–900. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banerjea AC, Brechling KA, Ray CA, Erikson H, Pickup DJ, Joklik WK. High-level synthesis of biologically active reovirus protein sigma 1 in a mammalian expression vector system. Virology. 1988;167(2):601–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagata L, Masri SA, Pon RT, Lee PW. Analysis of functional domains on reovirus cell attachment protein sigma 1 using cloned S1 gene deletion mutants. Virology. 1987;160(1):162–168. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner DL, Duncan R, Lee PW. Site-directed mutagenesis of the C-terminal portion of reovirus protein sigma 1: evidence for a conformation-dependent receptor binding domain. Virology. 1992;186(1):219–227. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Virgin HWt, Bassel-Duby R, Fields BN, Tyler KL. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing) J Virol. 1988;62(12):4594–4604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4594-4604.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burstin SJ, Brandriss MW, Schlesinger JJ. Infection of a macrophage-like cell line, P388D1 with reovirus; effects of immune ascitic fluids and monoclonal antibodies on neutralization and on enhancement of viral growth. J Immunol. 1983;130(6):2915–2919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hutchings AB, Helander A, Silvey KJ, Chandran K, Lucas WT, Nibert ML, Neutra MR. Secretory immunoglobulin A antibodies against the sigma1 outer capsid protein of reovirus type 1 Lang prevent infection of mouse Peyer's patches. J Virol. 2004;78(2):947–957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.947-957.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hogan KT, Cashdollar LW. Clonal analysis of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to reovirus. Viral Immunol. 1991;4(3):167–175. doi: 10.1089/vim.1991.4.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoffman LM, Hogan KT, Cashdollar LW. The reovirus nonstructural protein sigma1NS is recognized by murine cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1996;70(11):8160–8164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8160-8164.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parker SE, Sears DW. H-2 restriction and serotype crossreactivity of anti-reovirus cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) Viral Immunol. 1990;3(1):77–87. doi: 10.1089/vim.1990.3.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.London SD, Cebra JJ, Rubin DH. The reovirus-specific cytotoxic T cell response is not restricted to serotypically unique epitopes associated with the virus hemagglutinin. Microb Pathog. 1989;6(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fulton JR, Smith J, Cunningham C, Cuff CF. Influence of the route of infection on development of T-cell receptor beta-chain repertoires of reovirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2004;78(3):1582–1590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1582-1590.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen D, Lee F, Cebra JJ, Rubin DH. Predominant T-cell receptor Vbeta usage of intraepithelial lymphocytes during the immune response to enteric reovirus infection. J Virol. 1997;71(5):3431–3436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3431-3436.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huleatt JW, Lefrancois L. Antigen-driven induction of CD11c on intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and CD8+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154(11):5684–5693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bharhani MS, Grewal JS, Pilgrim MJ, Enocksen C, Peppler R, London L, London SD. Reovirus serotype 1/strain Lang-stimulated activation of antigen-specific T lymphocytes in Peyer's patches and distal gut-mucosal sites: activation status and cytotoxic mechanisms. J Immunol. 2005;174(6):3580–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fleeton MN, Contractor N, Leon F, Wetzel JD, Dermody TS, Kelsall BL. Peyer's patch dendritic cells process viral antigen from apoptotic epithelial cells in the intestine of reovirus-infected mice. J Exp Med. 2004;200(2):235–245. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greene MI, Weiner HL. Delayed hypersensitivity in mice infected with reovirus. II. Induction of tolerance and suppressor T cells to viral specific gene products. J Immunol. 1980;125(1):283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fleeton M, Contractor N, Leon F, He J, Wetzel D, Dermody T, Iwasaki A, Kelsall B. Involvement of dendritic cell subsets in the induction of oral tolerance and immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1029:60–65. doi: 10.1196/annals.1309.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.George A, Kost SI, Witzleben CL, Cebra JJ, Rubin DH. Reovirus-induced liver disease in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice. A model for the study of viral infection, pathogenesis, and clearance. J Exp Med. 1990;171(3):929–934. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fawaz LM, Sharif-Askari E, Menezes J. Up-regulation of NK cytotoxic activity via IL-15 induction by different viruses: a comparative study. J Immunol. 1999;163(8):4473–4480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.al-Sheboul S, Crosley D, Steele TA. Inhibition of reovirus-stimulated murine natural killer cell cytotoxicity by cyclosporine. Life Sci. 1996;59(20):1675–1682. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parker SE, Sun YH, Sears DW. Differential expression of the ASGM1 antigen on anti-reovirus and alloreactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) J Immunogenet. 1988;15(4):215–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313x.1988.tb00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fan JY, Boyce CS, Cuff CF. T-Helper 1 and T-helper 2 cytokine responses in gut-associated lymphoid tissue following enteric reovirus infection. Cell Immunol. 1998;188(1):55–63. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mathers AR, Cuff CF. Role of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-10 in serum immunoglobulin G antibody responses following mucosal or systemic reovirus infection. J Virol. 2004;78(7):3352–3360. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3352-3360.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Montufar-Solis D, GT, Teng BB, Klein JR. ICOS is upregulated on CD43+ CD4+ murine small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes during acute reovirus infection: Functional separation of early and late responses to infection. J Immunol. 2005 (submitted) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Puddington L, Olson S, Lefrancois L. Interactions between stem cell factor and c-Kit are required for intestinal immune system homeostasis. Immunity. 1994;1(9):733–739. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang HC, Zhou Q, Dragoo J, Klein JR. Most murine CD8+ intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes are partially but not fully activated T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):4717–4722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shires J, Theodoridis E, Hayday AC. Biological insights into TCRγδ+ and TCRαβ+ intraepithelial lymphocytes provided by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) Immunity. 2001;15(3):419–434. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayday A, Theodoridis E, Ramsburg E, Shires J. Intraepithelial lymphocytes: exploring the Third Way in immunology. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(11):997–1003. doi: 10.1038/ni1101-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]