Abstract

CEACAM1 (carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1), a type I transmembrane glycoprotein involved in cell–cell adhesion has been shown to act as an angiogenic factor for mouse and human endothelial cells. Based on the ability of CEACAM1 to initiate lumen formation in human mammary epithelial cells grown in 3D culture (Matrigel), we hypothesized that murine CEACAM1 may play a similar role in vasculogenesis. In order to test this hypothesis, murine embryonic stem (ES) cells stimulated with VEGF were differentiated into embryoid bodies (EB) for 8 days (−8–0 d) and transferred to Matrigel in the presence or absence of anti-CEACAM1 antibody for an additional 12 days (0–12 d). In the absence of anti-CEACAM1 antibody or in the presence of an isotype control antibody, the EB in Matrigel underwent extensive sprouting, generating lengthy vascular structures with well-defined lumina as demonstrated by confocal microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunohistochemical analysis. Both the length and architecture of the vascular tubes were inhibited by anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1, a mAb that blocks the cell–cell adhesion functions of CEACAM1, thus demonstrating a critical role for this cell–cell adhesion molecule in generating and maintaining vasculogenesis. QRT–PCR analysis of the VEGF treated ES cells grown under conditions that convert them to EB revealed expression of Ceacam1 as early as −5 to −3 d reaching a maximum at day 0 at which time EBs were transferred to Matrigel, thereafter levels at first declined and then increased over time. Other markers of vasculogenesis including Pecam1, VE-Cad, and Tie-1 were not detected until day 0 when EBs were transferred to Matrigel followed by a steady increase in levels, indicating later roles in vasculogenesis. In contrast, Tie-2 and Flk-1 (VEGFR2) were detected on day five of EB formation reaching a maximum at day 0 on transfer to Matrigel, similar to Ceacam1, but after which Tie-2 declined over time, while Flk-1 increased over time. QRT–PCR analysis of the anti-CEACAM1 treated ES cells revealed a significant decrease in the expression of Ceacam1, Pecam1, Tie-1, and Flk-1, while VE-Cad and Tie-2 expression were unaffected. These results suggest that the expression and signaling of CEACAM1 may affect the expression of other factors known to play critical roles in vasculogenesis. Furthermore this 3D model of vasculogenesis in an environment of extracellular matrix may be a useful model for comparison to existing models of angiogenesis.

Keywords: CEACAM1, Vasculogenesis, Embryonic stem cells, Lumen formation, Embryoid bodies

Introduction

Vasculogenesis is the generation of new blood vessels during embryonic development [1]. The process involves the differentiation of endothelial cells from a stem cell compartment in the embryo. The endothelial cells form tubes that grow throughout the developing embryo and later conduct blood and lymph in the developing vascular system. In contrast, angiogenesis is the sprouting of new blood vessels from existing ones [1,2]. Both processes employ vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as a key molecule [3,4] that binds to VEGF receptors VEGFR-1, also called FLT-1 (fms-like tyrosine kinase) [5,6] and VEGFR-2, also called KDR in human and FLK-1 in mouse. Both belong to the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) subfamily [5], are mainly expressed in the vascular endothelium and are involved in angiogenesis activities, including proliferation, survival, migration, and permeability of vascular endothelial cells [7,8].

Human carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) has been shown to be a potent stimulant for VEGF-mediated angiogenesis [9,10]. In the case of human endothelial cells, CEACAM1 purified from human granulocytes was shown to stimulate chemotaxis and capillary formation of microvascular endothelial cells grown in the presence of VEGF, a process that was inhibited by anti-CEACAM1 antibodies [9]. In the case of a murine endothelial cell line lacking the Ceacam1 gene, transfection with a murine CEACAM1 cDNA stimulated sprouting in a Matrigel plug assay [11]. Although Ceacam1−/− mice develop normally, their endothelial cells fail to establish new blood vessels in the Matrigel plug assay, a function that was restored in endothelial cells from Ceacam1endo+ mice where Ceacam1 was re-expressed under the Tie-2 promoter [11]. These studies raise important questions about the role of Ceacam1 in endothelial cells in that it appears, on the one hand, to be dispensable during embryogenesis, and on the other hand, to be essential for angiogenesis.

A similar situation may exist for platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (CD31, Pecam1−/−) kockout mice, in which the mice are viable and develop a normal vascular system, but when the endothelial cells are tested in vitro, they are abnormal [12,13]. For example, lung microvascular cells from these mice fail to form tubes on Matrigel [14], and migrate poorly on fibronectin in a wound healing assay [15]. The authors speculate that other molecules with similar functions may replace PECAM1 in vivo. This possibility is strengthened by the similar domain structures between PECAM1 and CEACAM1, both comprising extracellular homotypic adhesive Ig-like domains with ITIM-bearing cytoplasmic domains, and their comparable roles in homophillic cell–cell adhesion. Thus, both CEACAM1 and PECAM1 are cell adhesion proteins that play a role in endothelial cell sprouting. While a number of studies demonstrate a role for CEACAM1 in angiogenesis and a role for PECAM1 in both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis, no studies on the importance of CEACAM1 in vasculogenesis have been performed. In this respect, vasculogenesis begins early during embryogenesis: starting between E7 and E7.5, mesoderm cells begin to proliferate, forming the mesodermal cell masses, which are the precursors of so called “blood islands” [16,17]. Following this development, the central cells of the blood islands produce hemoglobin while the outer layer of cells differentiates into the endothelial network [17]. When Daniels et al. used three different anti-CEACAM1 antibodies to stain E7.5 mouse embryos, they concluded that there was a complete absence of CEACAM1 expression [18]. However, in their study the presence of blood island precursors was not shown. We show here that CEACAM1 is indeed expressed in the murine blood island precursors, suggesting that CEACAM1 may play a role in vasculogenesis in the developing embryo.

In our studies, we have shown that human CEACAM1 is essential for lumen formation in both in vitro and in vivo models of human mammary gland morphogenesis [19–21]. Whether or not this holds true in the murine mammary gland has not been investigated, yet mammary gland formation is apparently normal in Ceacam1−/− mice (Beauchemin, personal communication). Thus, it is likely that compensating systems may operate in gene knock-out mice, obscuring the true role of a given gene. Since vasculogenesis also involves lumen formation, we speculate that CEACAM1 may play a similar role in this process in normal mice. We considered growing murine embryoid bodies (EB) in a 3D culture as an in vitro model system for investigating this possibility to be ideal because EB are directly derived from ES cells and have been previously shown to undergo vasculogenesis after treatment with VEGF and growth on Matrigel (see below).

Matrigel is a convenient source of extracellular matrix that has been shown repeatedly to simulate a vital 3D environment for glandular morphogenesis [22]. For example, when murine EB are grown in Matrigel they undergo gastrulation-like events, including the formation of endoderm and mesoderm [23]. Mouse EBs cultured in the presence of VEGF undergo vascular sprouting and produce a nearly pure population of endothelial cells [3,24]. These tubes are fully capable of sustaining blood flow when transferred to E9 embryo hearts, demonstrating that these are functional vascular tubes [25]. Furthermore, these cells express most of the expected markers of vascular endothelial cells including Pecam1, VE-Cad, Tie-1/2, and Flk-1 [4]. Thus, it appears that starting from ES cells, only VEGF and Matrigel are required for the initiation of vasculogenesis. Furthermore, when PECAM1 positive cells are selected from human ES cells and grown on Matrigel, endothelia cell sprouting occurs [24]. Given the incomplete understanding of the critical factors involved in vasculogenesis, the known role of human CEACAM1 in lumen formation, and the overlapping functions of CEACAM1 and PECAM1, we utilized the EB/VEGF/3D model system to study the role of murine CEACAM1 in vasculogenesis.

When murine EB differentiated in the presence of VEGF for 8 days were transferred to Matrigel, these EB produced extensive vascular sprouting. Quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (QRT–PCR) analysis detected the time course of expression of the vascular endothelial marker genes Ceacam1, Pecam1, VE-Cad, Tie-1/2, and Flk-1. Confocal and electron microscopy analysis of these cells revealed a defined lumen, and immunostaining revealed luminal expression of CEACAM1. Many of the lumina contained apoptotic bodies indicating that vascular lumina may form in a manner analogous to mammary gland lumen formation in which central acinar cells undergo apotosis [19–21]. The sprouting was inhibited and the vessel architecture was abnormal when EB were cultured in the presence of VEGF and anti-CEACAM1 monoclonal antibody prior to plating into Matrigel, but identical treatment with a monoclonal antibody isotype control had no effect on the formation of vascular sprouts. Furthermore, the message levels of Ceacam1, Pecam1, Tie-1, and Flk-1, but not VE-Cad and Tie-2, were reduced. These studies establish an important role for Ceacam1 in vasculogenesis and suggest that its function may be replaced in the Ceacam1−/− mice by other cell adhesion genes such as Pecam1. The reciprocal and hierarchal roles of these two cell–cell adhesion molecules require further investigation.

Materials and methods

Growth factors and antibodies

Murine recombinant VEGF165 (vascular endothelial growth factor) was purchased from PEPROTECH Inc. (Rocky Hill, New Jersey). Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM1) and Alexa Fluor 488 rat IgG2a (isotype control) were obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA), used for Confocal microscopy. Rat anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM1) was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA), used for antibody inhibition assay. Anti-rat IgG2a used as an isotype control was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 (Mouse IgG1) has been previously described [26]. Bovine insulin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MA). Mouse antihuman CD33 (IgG1) used as an isotope control was a kind gift from Dr. David Colcher (City of Hope).

Cell culture and embryoid body formation

Mouse embryonic stem cells derived from strain 129S1-SVImj were cultured on amitotically-inactivated STO-Neo/LIF feeder layer [from EJ Robertson] in DMEM (Mediatech Inc, Herndon, VA)containing 16% fetal bovine serum, non-essential amino acids (GIBCO, stock solution diluted 1:100, final concentration 100 nM), GlutaMax (Invitrogen), penicillin/streptomycin, and 30 nM 2-mercaptoethanol (ES medium). The ES cells were digested at 37 °C with Trypsin/EDTA, and reduced to a single-cell suspension by pipetting. The STO feeder cells were depleted by incubating the cell suspension in a plastic tissue-culture dish in ES medium in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 45min. The non-adherent cells were transferred to a fresh plastic tissue-culture dish, and incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for an additional 45 min. The resulting non-adherent cells contained ca 90% ES cells, and the enriched ES cells were frozen in 20% FBS/10% DMSO/70% DPBS without Ca2+/Mg2+.

ES cells were cultured on 1% agar coated Petri-dishes in DMEM (Mediatech Inc, Herndon, VA) with 14% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum(Omega Scientific Inc., Tarzana, CA), non-essential amino acids (GIBCO, stock solution diluted 1:100, final concentration 100 nM), 2-mercaptoethanol (GIBCO, final concentration 30 nM) and 5% of Antibiotic–Antimycotic (GIBCO, stock solution diluted 1:100, final concentration 1000 U of penicillin,1000 µg of streptomycin),100 µg/ ml VEGF and 10 µg/ml bovine insulin were added into medium.

Mouse embryonic blood island collection

Timed-matings were set up with outbred mice. Pregnant females were euthanized at 7.5 days after detection of the copulatory plug, and the implantations were dissected from the uterus. Samples were fixed in 4% PFA/DPBS at room temp for 45 min, and then continued the fixation in 1% PFA/DPBS at +4 °C overnight. On second day, samples were washed 3 times in DPBS+, and then processed for immunohistochemistry analysis. All usage of animals was approved under a City of Hope IACUC protocol.

Matrigel in vitro tube formation assay

Regular Matrigel (450 µl, BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA. LOT 81148) or growth factor reduced Matrigel (450 µl, BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA. LOT A4539 was added to 12-well plates and allowed to solidify for 20 min at 37 °C. After the Matrigel solidified, an additional 500 µl of Matrigel mixed with embryoid bodies was then plated on the top of previous Matrigel layer and allowed to solidify for 20 min at 37 °C. Complete medium including VEGF and insulinwas then added and the plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from murine embryonic stem cells or EB by using Trizol® method (GIBCO-BRL/Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, samples were homogenized in 500 µl Trizol® (GIBCO-BRL/Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), followed by the addition of 100 µl chloroform. After centrifugation at 4 °C at 14,000 rpm for 15 min, the top clear layer was transferred to a clean microcentrifuge tube. Then 400 µl 2-propanol was added to the samples and they were vortexed. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The total RNA was then purified by washing in 75% ice-cold ethanol one time and after a 5 min, 14,000 rpm centrifugation at 4 °C, the RNA pellet was air dried and dissolved in 50 µl RNase free water. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was then prepared using the Omniscript® reverse transcription system (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The reverse transcription system contains oligo primers, RNase inhibitor, MMLV reverse transcriptase, dNTP mix, buffer and 2.5 µg total RNA in a final volume of 20 µl. The reaction mixture was incubated at 42 °C for 1 h and then stored at −20 °C until used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotide primers used for real-time PCR.

| Transcript | Sense 5′ to 3′ | Antisense 5′ to 3′ | Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hprt | GCTGGTGAAAAGGACCTCT | CACAGGACTAGAACACCTGC | 248 | [46] |

| Ceacam1 | ATGAACAGTGAGGCAGTCCC | AGGCTCTGGCCAGTATCTGA | 139 | |

| Pecam1 | GTCATGGCCATGGTCGAGTA | CTCCTCGGCATCTTGCTGAA | 260 | [47] |

| Tie-1 | CTCACTGCCCTCCTGACTGG | CGATGTACTTGGATATAGGC | 228 | [48] |

| Tie-2 | GATTTTGGATTGTCCCGAGGGTCAAG | CACCAATATCTGGGCAAATGATGG | 327 | [49] |

| VE-Cadherin | CAGCACTTCAGGCAAAAACA | TTCTGGTTTTCTGGCAGCTT | 111 | |

| Flk-1 | TCTGTGGTTCTGCGTGGAGA | GTATCATTTCCAACCACCCT | 269 | [50] |

| Ceacam1-4L | CTGAGGGCAACAGGACTCTC | CTGAATGGGTCACTTCGGTT | 109 | |

| Ceacam1-2L | TCCCTGCTCTTCCAAATGAT | GAGGAAGGGCTGAGTCACTG | 132 |

Quantitative expression of the genes Ceacam1, Ceacam1 4L, Ceacam1 2L, Flk-1, Tie-1, Tie-2, VE-Cad, Pecam1, and the “house-keeping” gene Hprt were measured using the Bio-Rad IQ5 Real-time Detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA). Gene expression was quantified using Quantace 2X SYBR master mix (Norwood, MA), standard DNA primer sequences and standard curves according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the amplification parameters were initiated at 95 °C for 5 min, then 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s for 40 cycles, followed by 7 min at 72 °C for the final extension.

Immunohistochemistry

Samples of EB in Matrigel in 12 well plates were washed twice in PBS and fixed in 10% NBF for 10 min. After fixation, wells were washed in PBS 3 times, each time is 5 min. Right after washing, 3% liquid agar was directly added to the cells, allowed to gel for 10 min, and fixed in formalin overnight. Following fixation, mouse 7.5dpc implantations and EB in Matrigel were embedded in paraffin, and immunohistochemical staining was performed on 5-µm thick sections. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene for 5 min followed by graded ethanol washes. Samples were pretreated with 3% hydrogen peroxide and subjected to antigen retrieval by steam in DIVA/citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min. After antigen retrieval, slides were pre-incubated with “protein block” for 5 min and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-mouse CEACAM1 CC1 monoclonal antibody (90 µg/ml). Afterwards, the slides were washed and incubated in Mouse Polymer for 30 min, stained with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB), and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Confocal microscopy

EB were grown in Matrigel and stained with mAb CC1 (1 µg/ml) or mouse anti-human CD33 isotype control antibody (1 µg/ml) for 10 h at 37 °C and washed with DMEM medium containing 14% bovine serum and growth factors for 15 min 3 times at 37 °C. Secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon) were then added for 8 h at 37 °C, followed by 15 min 3 ti0me washes at 37 °C with DMEM medium containing 14% serum and growth factors. Confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss Model 510 (Oberkochen, Germany) confocal microscope.

EB were grown in Matrigel and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse PECAM1 antibody (1 µg/ml, BioLegned) or Alexa Fluor 488 rat IgG2a antibody (1 µg/ml, BioLegned ) for 10 h at 37 °C and washed with DMEM medium containing 14% bovine serum and growth factors for 15 min 3 times at 37 °C. Confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss Model 510 (Oberkochen, Germany) confocal microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy

Matrigel was lifted from 12 well plates, washed with PBS, fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer at RT overnight, treated with 1% OsO4 for 30 min, washed, dehydrated with stepwise ethanol–water treatments and embedded in Eponate. Thin sections were stained for 15 min with aqueous 5% uranyl acetate followed by 2 min staining with Sato's lead. Sections were observed and photographed with a FEI Tecnai G2 12 twin transmission electron microscope equipped with a Gatan US 1000 2K CCD camera.

Western blotting

The Matrigel was digested with matrisperse (BD) at 4 °C for 4 h with shaking, and then the cells were isolated by centrifugation. Total proteins (50 µg) from 1% NP40 cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitro-cellulose membranes and probed with anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 (1 µg/ml) and anti-β-actin antibody (1 µg/ml, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) antibodies. Signals were detected on the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Antibody inhibition assay

Anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 (10 µg/ml) or isotope control antibody mouse anti-human IgG1 (10 µg/ml) were added to the medium on day −8 when ES cells were either in the Petri-dishes or on day 0 when EB were transferred to Matrigel. Mediumwas changed every other day until day 0 in the Petri-dishes or until day 12 in Matrigel. Cells in the Petri-dishes were also collected for real-time PCR and Western blot analysis.

Anti-PECAM1 (10 µg/ml, eBiosciences) or isotype control antibody rat IgG2a (10 µg/ml) were performed under the same condition as CC1 antibody.

Results

Expression of CEACAM1 in murine blood island precursors

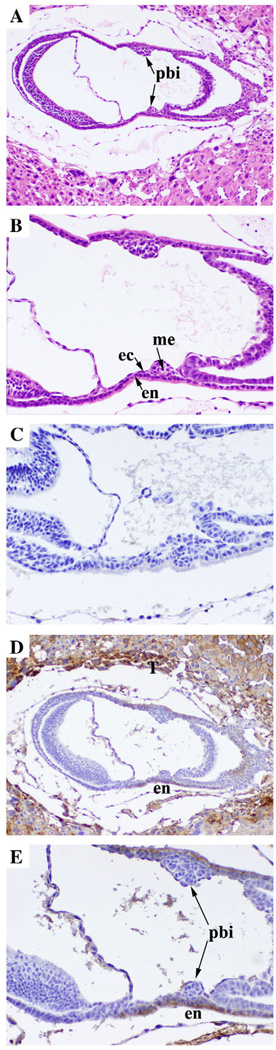

Previous studies have shown that CEACAM1 could not be detected in the early post-implantation embryo [18]. However, in that study the staining for blood island precursors was not shown. Therefore, we reinvestigated CEACAM1 expression in E7.5 embryos that had clearly developed blood island precursors. As shown in Fig. 1, CEACAM1 was strongly expressed in the endodermal cells surrounding the blood island precursors. In addition, the intermediate trophoblasts from the placenta strongly expressed CEACAM1 in agreement with Daniels el al. [18], thus providing a positive internal control for CEACAM1 staining (Fig. 1D). As expected, the staining of the embryo with secondary antibody only (no primary) was negative (Fig. 1C). These results suggest the possibility that CEACAM1 may play a role in early vasculogenesis in the developing embryo.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of CEACAM1 expression in murine blood island precursors. Outbred mouse E7.5 embryos were collected as described, and then they were fixed and stained by hemotoxylin and eosin A (Mag 50×) and B (Mag 100×) or with secondary antibody only C or with anti-Ceacam1 monoclonal antibody CC1 D (Mag 50×) and E (Mag 100×). Arrow indicates mesoderm (me), endoderm (en), ectoderm (ec) and blood island precursors (pbi).

Formation of vascular tubes in Matrigel

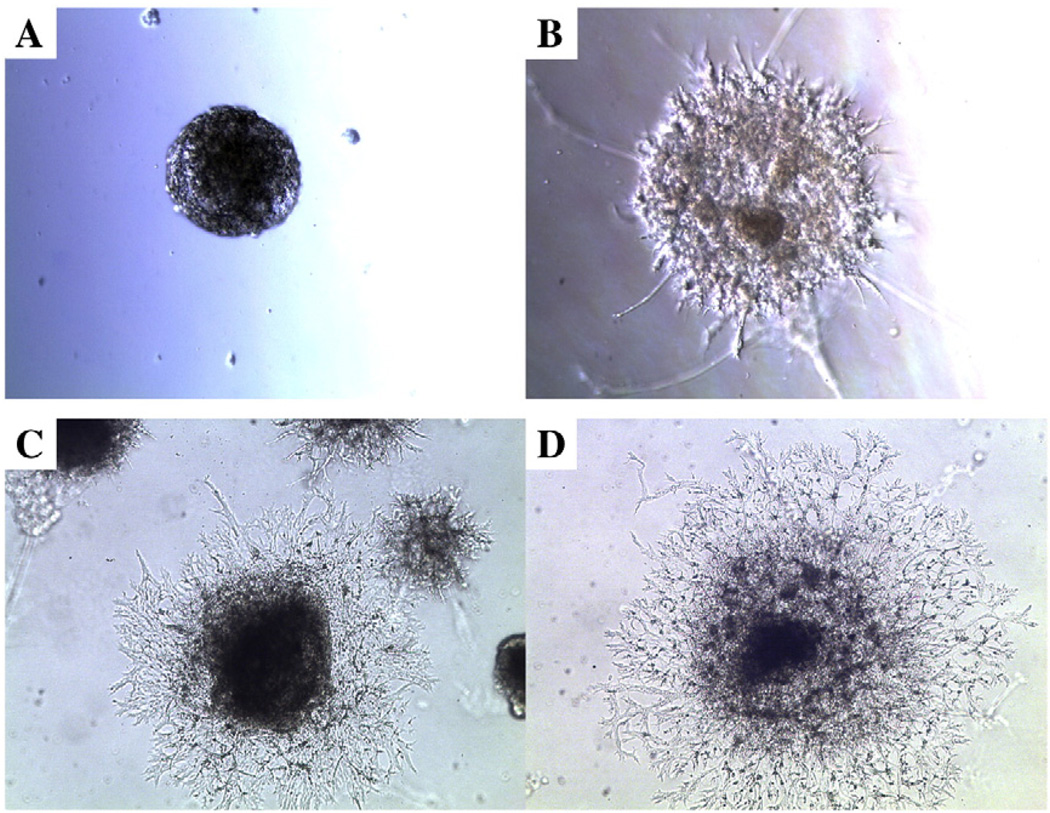

Previous studies have shown that VEGF treatment of murine ES cells grown on type IV collagen (a component of Matrigel) coated plates [3] or on Matrigel [27] undergo vasculogenesis. In addition, EB treated with VEGF grown in the presence [28] or absence [13] of Matrigel undergo vasculogenesis. Based on our observation that human mammary epithelial cells grown in 3D culture containing Matrigel require CEACAM1 to undergo lumen formation [19–21], we asked if a similar 3D model could be used for studying the role of murine CEACAM1 in lumen formation for ES/EB undergoing vasculogenesis. Murine ES cells cultured in the presence of STO/LIF feeder cells and VEGF for 4 days were transferred to plates coated with 1% agar to induce EB formation. After 8 days EB were mixed with Matrigel, overlaid with an existing layer of Matrigel, and treated with medium containing VEGF to produce a 3D environment for vasculogenesis. Vascular sprouts were observed after 1–2 days with almost complete conversion to vascular tubes by 12 days (Fig. 2). After that, the cells began to liquefy the Matrigel, destroying most of the 3D cultures. However, in a few cases, the cells survived longer than 13 days and underwent further differentiation into a variety of cell types including beating cardiomyocytes. For the sake of reproducibility, only the cultures from 0–13 days are described here. In order to quantitate the effects of different conditions on vascular sprouting, we examined EB using three parameters. The first was the number of EB with no detectable sprouts. The second and third were the numbers of EB with either short (<250 µm) or (>250 µm) long sprouts. In the absence of VEGF, vascular tubes also developed from EB, but at a later time (Table 2). It is also important to note that Matrigel itself contains growth factors in addition to extracellular matrix that might affect vasculogenesis. To determine if the observed vasculogenesis was mainly due to the presence of these growth factors, we also performed the experiment using dialyzed Matrigel, containing reduced amounts of growth factors. Although the time course of vasculogenesis is similar for regular or dialysed Matrigel, it appears that vasculogenesis is slightly favored in dialyzed Matrigel (Table 2). This may reflect opposing effects of the extra growth factors present in regular Matrigel.

Fig. 2.

Development of vascular sprouts from VEGF treated EB in Matrigel. ES cells were treated with 100 µg/ml VEGF and 10 µg/ml bovine insulin for 8 d on 1% agar coated plates to induce EB formation and then transferred to a 3D Matrigel culture for an additional 13 d. Starting from the day of transfer to Matrigel, microscopic analysis of the EB at day 0 (A), day 4 (B), day 8 (C), and day 12 (D) reveals extensive sprouting over time (Mag 50×).

Table 2.

Quantitation of vascular sprouting in the presenece or absence of VEGF or in Matrigel vs. growth factor reduced Matrigel.a

| Day | Day 4 | Day 8 | Day 11 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gel type | Regular | GF reduced | Regular | GF reduced | Regular | GF reduced | ||||||

| VEGF | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| No sprouts | 31,25 | 50,49* | 27,26 | 50,48** | 25,26 | 31,38 | 27,24 | 22,21 | 23,22 | 21,25 | 16,11 | 18,14 |

| Sprouts <250 µm | 44,48 | 31,34* | 51,49 | 32,31** | 35,28 | 40,37 | 17,17 | 43,42** | 22,25 | 24,24 | 12,15# | 14,17# |

| Sprouts >250 μm | 25,27 | 19,17* | 22,25 | 18,21 | 40,46 | 29,25* | 56,59# | 36,38** | 55,53 | 55,51 | 72,74## | 68,69# |

EBs were grown in the regular Matrigel or growth factor reduced Matrigel in the presence or absence of 100 µg/ml VEGF. The numbers of sprouts were quantitated at days 4, 8, and 11 as follows: the number with no sprouts, the number with sprouts <250 µm, and the number with sprouts >250 µm. The experiment was repeated twice. Values were compared to the no VEGF treatment control (*, p<0.05,**, p<0.01) or regular vs. GF reduced Matrigel (#, p<0.05,##, p<0.01) by the Student's T test.

Expression of Ceacam1 in EB sprouted vascular tubes in Matrigel

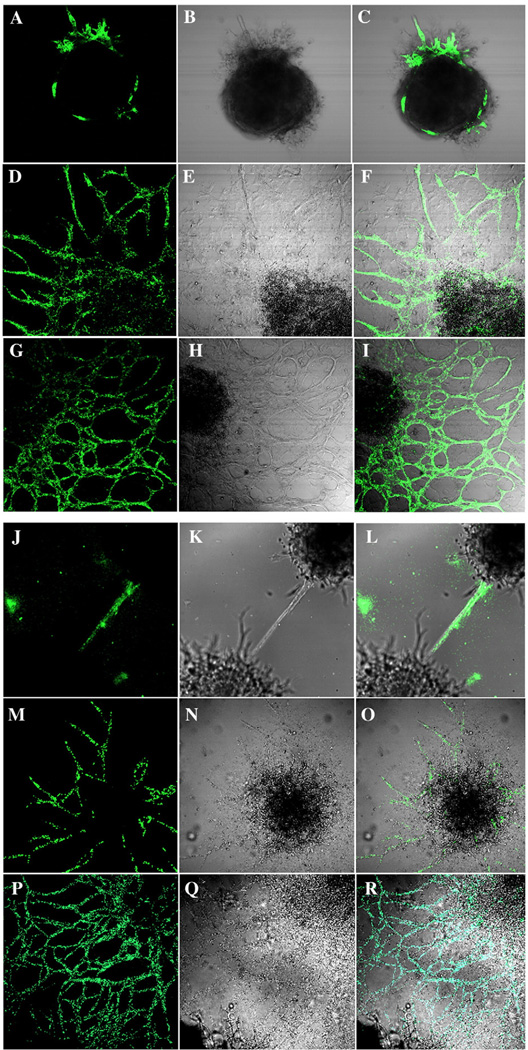

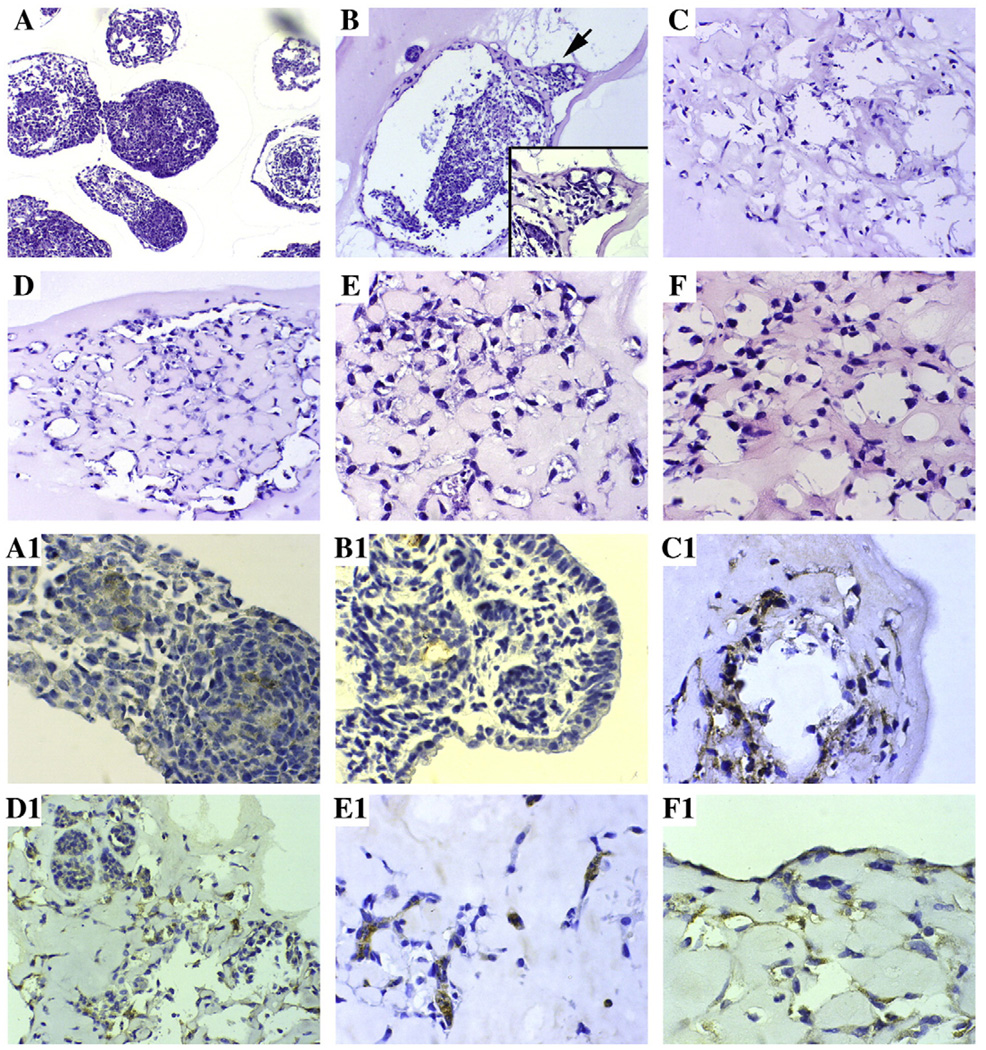

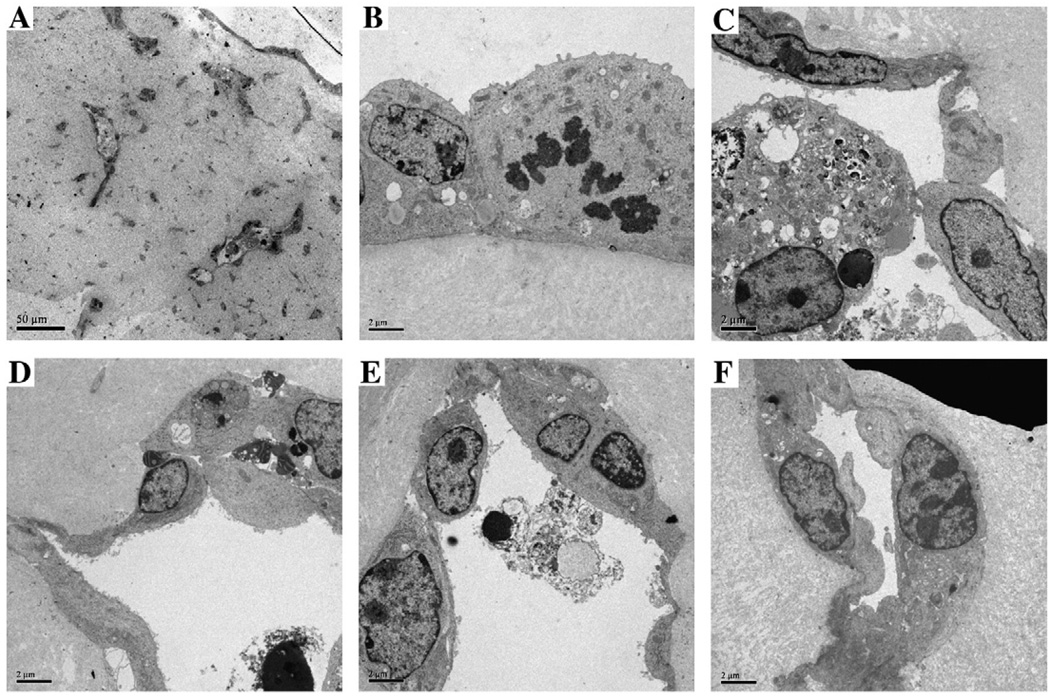

Analysis of the 3D EB cultures stained with either anti-PECAM1 or anti-CEACAM1 antibodies and analyzed by confocal microscopy reveals dark EB masses surrounded by a halo of PECAM1 or CEACAM1 positive vascular tubes (Fig. 3). The endothelial lineage of the vascular tubes was confirmed by the PECAM1 staining. It can be seen that the patterns of staining for both PECAM1 and CEACAM1 is similar. When the Matrigel cultures were fixed and immunostained, CEACAM1 was observed along the luminal surfaces of tubes (Fig. 4). The inner diameters of tubes ranged from 4–60 µm. The flattened shape of the nuclei was consistent with an endothelial lineage. The tube-like structure was further characterized using electron microscopy (Fig. 5). Both empty and apoptotic cell filled lumina were observed, similar to our previous observation that in an in vitro model of mammary morphogenesis the lumen was generated by apoptosis of central acinar cells [19,20]. In a few cells, we also observed the formation of dense granular structures, reminiscent of Weibel–Palade bodies, a characteristic of endothelial cells [29,30]. Again, the cells and nuclei have a flattened morphology, consistent with their endothelial linage.

Fig. 3.

Confocal analysis of CEACAM1 and PECAM1 protein expression on EB grown in 3D culture. EBs grown as described in Fig. 2 were stained with antibodies to PECAM1 (A, D, G) or CEACAM1 (J, M, P), imaged by phase contrast (B, E, H, K, N, Q) and the two images overlaid (C, F, I, L, O, R) (Mag 100×).

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of endothelial sprouts from EB grown in 3D culture. EBs grown as described in Fig. 2 were fixed and stained by hemotoxylin and eosin (A–F) or with anti-Ceacam1 monoclonal antibody CC1 (A1–F1) at day 0 (A, A1), day 3 (B, B1), day 6 (C, C1), day 8 (D, D1), day 10 (E, E1) and day 13 (F, F1). A and B (Mag 50×, inset 100×), C and D (Mag 100×), E and F (Mag 200×). A1, B1, E1, and F1 (Mag 200×), C1 and D1 (Mag 100×).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of endothelial sprouts from EB grown in 3D culture by electron microscopy. EBs grown as described in Fig. 2 were examined by TEM. Low power (60×) reveals the presence of multiple small (ca 2 µM diam) and a few large (5–10 µM diam) vascular tubes (A). High power (1100×) examination of the vascular tubes reveals a tight connection to the ECM (B, lower) with a few microvilli on the luminal surface (upper, B), and in some cases, the presence of darkly staining multilamellar bodies (center, B). Examination of the lumina at high power (1100×) reveals apoptotic bodies with condensed nuclei and degraded cytoplasm surrounded by flattened endothelial cells (C–E). A complete small (ca 2 µm diam) vascular tube is shown in F.

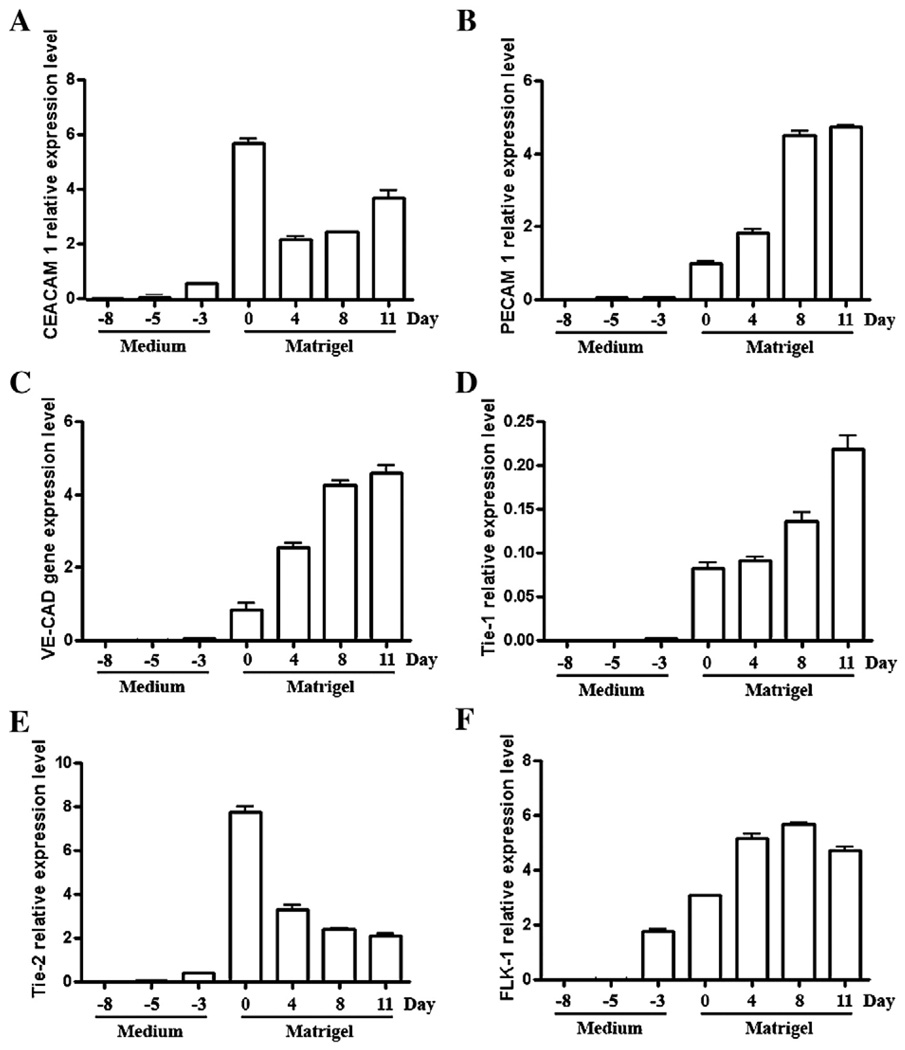

The RNA from cells harvested at various time points, starting from the ES (pre-EB) stage, was subjected to QRT–PCR analysis. Ceacam1 expression increased from undetectable at the pre-EB stage to a maximum level at day 0 before the EB were transferred to Matrigel (Fig. 6). In contrast, the mRNA levels of Pecam1, VE-Cad, and Tie-1 were essentially below detection levels until after transfer of the EB to Matrigel (day 0), after which they increased uniformly to their maximal levels (day 12). In contrast Tie-2 and Flk-1 which, like Ceacam1, were detected at day −3 and reached maximal levels before transfer to Matrigel (day 0). The expression of Tie-2 began to decrease thereafter, while Flk-1 appeared to reach a plateau.

Fig. 6.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Ceacam1, Pecam1, VE-Cad, Tie-1, Tie-2, and Flk-1 mRNA levels in VEGF treated ES cells converted to EB and grown in Matrigel. ES cells grown on 1% agar and treated with VEGF for 8 days (Medium) were transferred to 3D culture (Matrigel) and grown for another 11 days in the continued presence of VEGF. Cells were harvested at the time points indicated, total RNA extracted and specific mRNAs quantitated in triplicate as described in Methods. The results are reported relative to the housekeeping mRNA of Hprt.

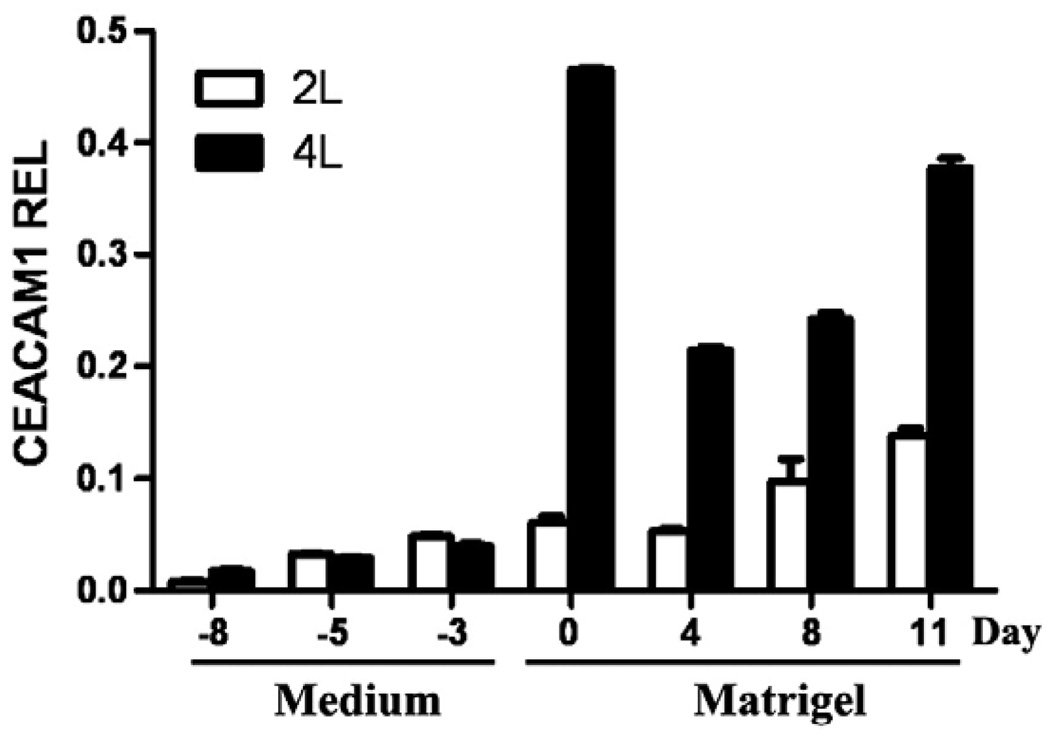

Since there are two genes coding for different CEACAM1 proteins in mice, Ceacam1 and Ceacam2, we sequenced the QRT–PCR products and found no evidence for the expression of the Ceacam2 gene (data not shown). Given that the primers selected for the Ceacam1 gene were in a region where sequence homology was low, this result was not unexpected. In addition, murine Ceacam1 produces multiple mRNAs due to alternative splicing. When we performed RT–PCR to determine which splice forms were present, we found only the CEACAM1-4L and -2L splice forms (data not shown). However, we were unable to quantitate the amount of each splice form in a conventional RT–PCR assay, so we performed QRT–PCR assays. These results demonstrate that the two splice forms are made in roughly equivalent amounts until day 0, at which time the amount of the -4L isoform rapidly rises and becomes the predominant splice form (Fig. 7). These results suggest that vasulogenesis at the level of CEACAM1 involves a shift in the splicing machinery. It is intriguing to speculate that such a change may involve other mRNAs that are differentially spliced.

Fig. 7.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Ceacam1 isoforms expressed in ES cells and EB. ES cells and EBs grown as described in Fig. 2 were harvested at the time points indicated, total RNA extracted, and PCR analysis performed using two sets of primers that identify the Ceacam1-4L and Ceacam1-2L, respectively. Results indicate that the major isoform expressed is Ceacam1-4L. Note that the expression level of Ceacam1 falls after transfer of EB to Matrigel and then increases over time. The results are reported relative to the housekeeping mRNA of Hprt.

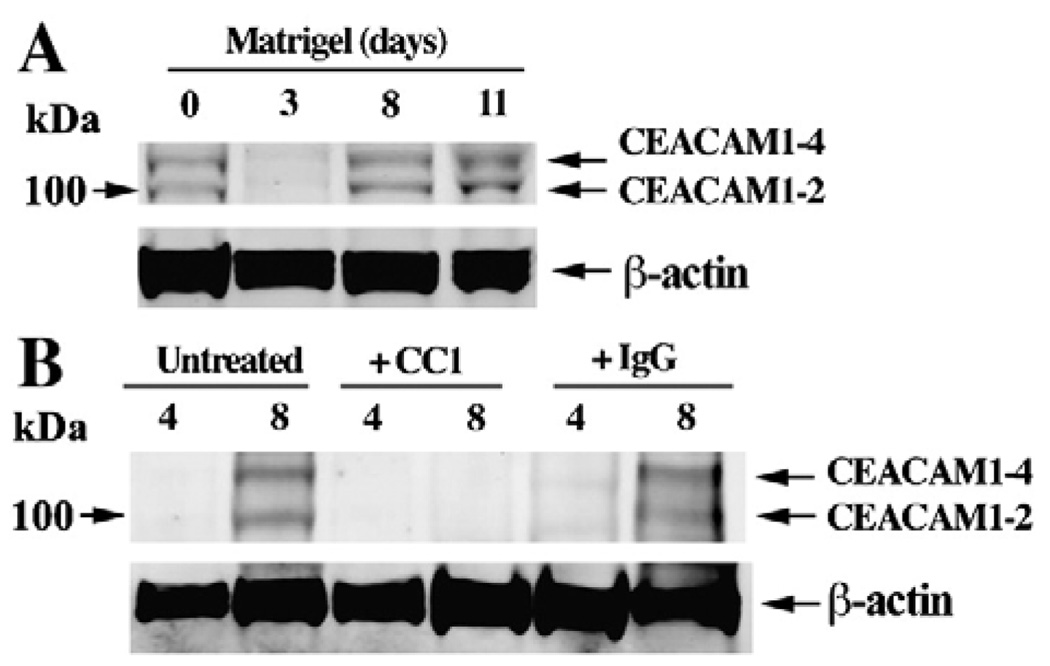

Western blot analysis of CEACAM1 for EBs transferred to Matrigel revealed a steady increase in protein levels over the course of 11 days (Fig. 8A). Based on the molecular sizes of the bands, it appears that the two and four ecto-domain forms of CEACAM1 were expressed. Western blot analysis was performed on CEACAM1 only due to difficulty of extracting a sufficient number of cells from 3D Matrigel cultures for protein expression studies. Since CEACAM1 is expressed as two predominant ecto-domain isoforms in mouse that vary in levels among different tissues [31], it was important to determine which isoforms are expressed during vasculogenesis. Based on the relative intensities of the bands (Fig. 8A), it appears that the 4 Ig domain isoform of CEACAM1 prevails over the 2 Ig domain isoform. A further consideration is the nature of the cytoplasmic domain isoforms in which short (12–14 amino acids) and long (72 amino acids) isoforms are expressed. The analysis of the expression of the short and long cytoplasmic domain isoforms by QRT–PCR reveals predominant expression of CEACAM1-4L (Fig. 7). The importance of the expression of the long cytoplasmic domain isoform includes its potential interaction with β-catenin [32]. Notably, VEGF induces the phosphorylation of β-catenin that directly associates with PECAM1 in endothelial cells [33], further linking the potential functions of CEACAM1 and PECAM1.

Fig. 8.

Western blot analysis of CEACAM1 expressed by EB grown in Matrigel in the absence or presence of an anti-CEACAM1 antibody. (A) EBs grown in Matrigel were harvested at 0, 3, 8, and 11 days, lysed, and CEACAM1 isoforms identified by western blot analysis with anti-CEACAM1 antibody CC1 and an anti-β-actin antibody. Note that the freshly transferred EBs have high levels of CEACAM1 which first fall and then rise again over time. (B) The experiment was repeated on EBs that were untreated, treated with anti-CEACAM1 antibody CC1, or treated with an isotype control IgG, the cells isolated at 0, 4, and 8 days, and the CEACAM1 expression analyzed by western blotting with anti-CEACAM1 antibody CC1 or anti-β-actin antibody.

Inhibition of vasculogenesis with anti-CEACAM1 or anti-PECAM1 monoclonal antibodies

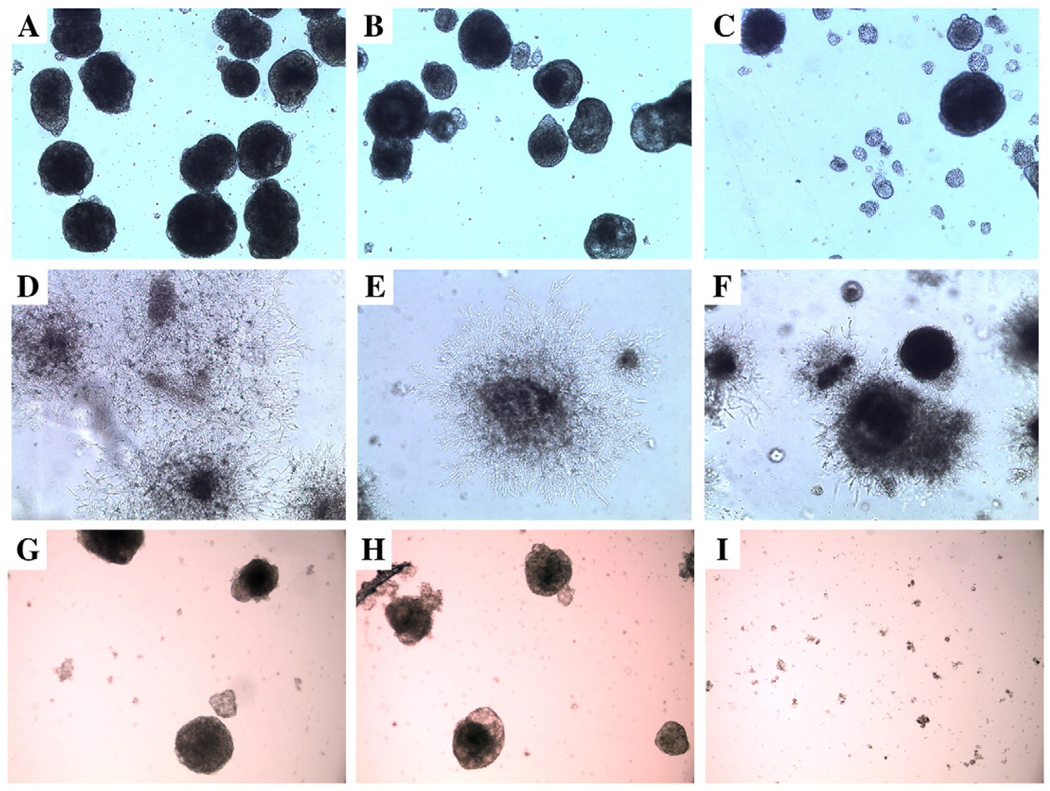

In order to demonstrate that CEACAM1 played a functional role in the observed vasculogenesis, the ES cells or EB were cultured in the presence of anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 or an isotype control mAb. Notably, EB formation was nearly completely inhibited by anti-CEACAM1 antibody, but not by the isotype control (Figs. 9A–C). This result suggests that the disruption of cell–cell adhesion by anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 largely prevented EB formation. Therefore, to test the effect of CC1 mAb on vasculogenesis, we introduced the mAb only after EB were transferred to Matrigel. In this case, the extent of and architectural appearance of the vascular network was severely altered (Figs. 9D–F). No effect was seen for the untreated or isotype treated controls. We also analyzed the protein levels of CEACAM1 by western blot analysis at 2 time points to determine if anti-CEACAM1 mAb treatment reduced the amount of CEACAM1 compared to untreated or isotype antibody treated controls. As shown In Fig. 8B, anti-CEACAM1 mAb treatment significantly reduced the levels of CEACAM1 protein at the 8 d time point.

Fig. 9.

Confocal analysis of EB treated with VEGF in the presence or absence of anti-CEACAM1 antibody or anti-PECAM1 antibody. ES cells grown on 1% agar to induce EB formation were treated with VEGF for 8 days only (A and G), VEGF plus isotype control IgG for 8 days (B and H), or VEGF plus anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 for 8 days (C) or anti-PECAM1 antibody (I) and analyzed by confocal microscopy (phase contrast). Note the inhibition of EB formation in the CC1 treated sample. EBs treated with VEGF only were transferred to Matrigel and were untreated (D), isotype IgG treated (E), or CC1 treated (F) for 8 days and analyzed by confocal microscopy (phase contrast). Note that sprouts were either absent or truncated in the CC1 treated sample. All samples at 50×.

In order to quantitate the effects of the anti-CEACAM1 antibody inhibition, we examined EB in three groups (untreated, isotype control, and anti-CEACAM1 treated) using the same three three parameters described earlier. The results shown in Table 3 demonstrate that mAb CC1 had a quantitative effect on the ability of the EB to produce sprouts. At day 4 of anti-CEACAM1 treatment, the number of EB with no sprouts roughly doubled compared to untreated or isotype treated controls (p<0.05), while the number with short sprouts was similar, and the number with long sprouts was reduced by about 50% (p<0.05). At day 8, the number with no sprouts remained >200% compared to controls, and the number with short or long sprouts was reduced by 50%. At day 12 most of the inhibition was lost with similar numbers of EB with short or long sprouts in all three groups. We conclude that inhibition of the function of CEACAM1 by a CEACAM1-specific mAb prevents normal vasculogenesis through day 8, but eventually, vasculogenesis is restored in spite of the presence of anti-CEACAM1 antibody.

Table 3.

Quantitation of vascular sprouting inhibition by anti-CEACAM1 antibody.a

| Day | Day 4 | Day 8 | Day 12 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | No tx | Iso tx | CC1 tx | No tx | Iso tx | CC1 tx | No tx | Iso tx | CC1 tx |

| No sprouts | 18,12 | 20,16 | 36,40* | 10,13 | 12,10 | 24,22* | 4,3 | 3,4 | 8,7* |

| Sprouts <250 µm | 50,49 | 48,40 | 50,46 | 16,15 | 23,21 | 51,56** | 7,5 | 7,8 | 9,10 |

| Sprouts >250 µm | 32,39 | 32,40 | 14,14** | 74,72 | 65,69 | 25,22** | 89,91 | 90,88 | 83,83 |

EBs were treated with 0 (No tx), 10 µg/ml of an isotype control Ab (Iso tx) or 10 µg/ml of anti-CEACAM1 antibody (CC1 tx) and the number of sprouts quantitated at days 4, 8, and 12 as follows: the number with no sprouts, the number with sprouts <250 µm, and the number with sprouts >250 µm. The experiment was repeated twice. All values were compared to the no treatment control by the student's T test (*, p<0.05,**, p<0.01).

Since PECAM1 may play an equally important role in vasculogenesis in our system, we also tested the effect of anti-PECAM1 antibodies on development of vascular tubes from EB. As shown in Figs. 9G–I the formation of EB was completely inhibited by anti-PECAM1 antibody and not by an isotype control antibody. Furthermore, as shown in Table 4 vascular tube formation from EB was inhibited by anti-PECAM1 antibody at early time points.

Table 4.

Quantitation of vascular sprouting inhibition by anti-PECAM1 antibody.a

| Day | Day 4 | Day 8 | Day 11 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | No tx | Iso tx | PE tx | No tx | Iso tx | PE tx | No tx | Iso tx | PE tx |

| No sprouts | 38,39 | 35,32 | 37,31 | 27,28 | 29,28 | 38,34* | 26,28 | 19,23 | 28,29 |

| Sprouts <250 µm | 51,48 | 53,57 | 55,51 | 38,39 | 41,39 | 42,45 | 29,28 | 33,27 | 23,28 |

| Sprouts >250 µm | 10,14 | 12,11 | 14,12 | 35,33 | 30,33 | 20,21** | 45,44 | 48,50 | 47,43 |

EBs were treated with 0 (No tx), 10 µg/ml of an isotype control Ab (Iso tx) or 10 µg/ml of anti-PEACAM1 antibody (PE tx) and the number of sprouts quantitated at days 4, 8, and 12 as follows: the number with no sprouts, the number with sprouts <250 µm, and the number with sprouts >250 µm. The experiment was repeated twice. All values were compared to the no treatment control by Student's T test (*, p<0.05,**, p<0.01).

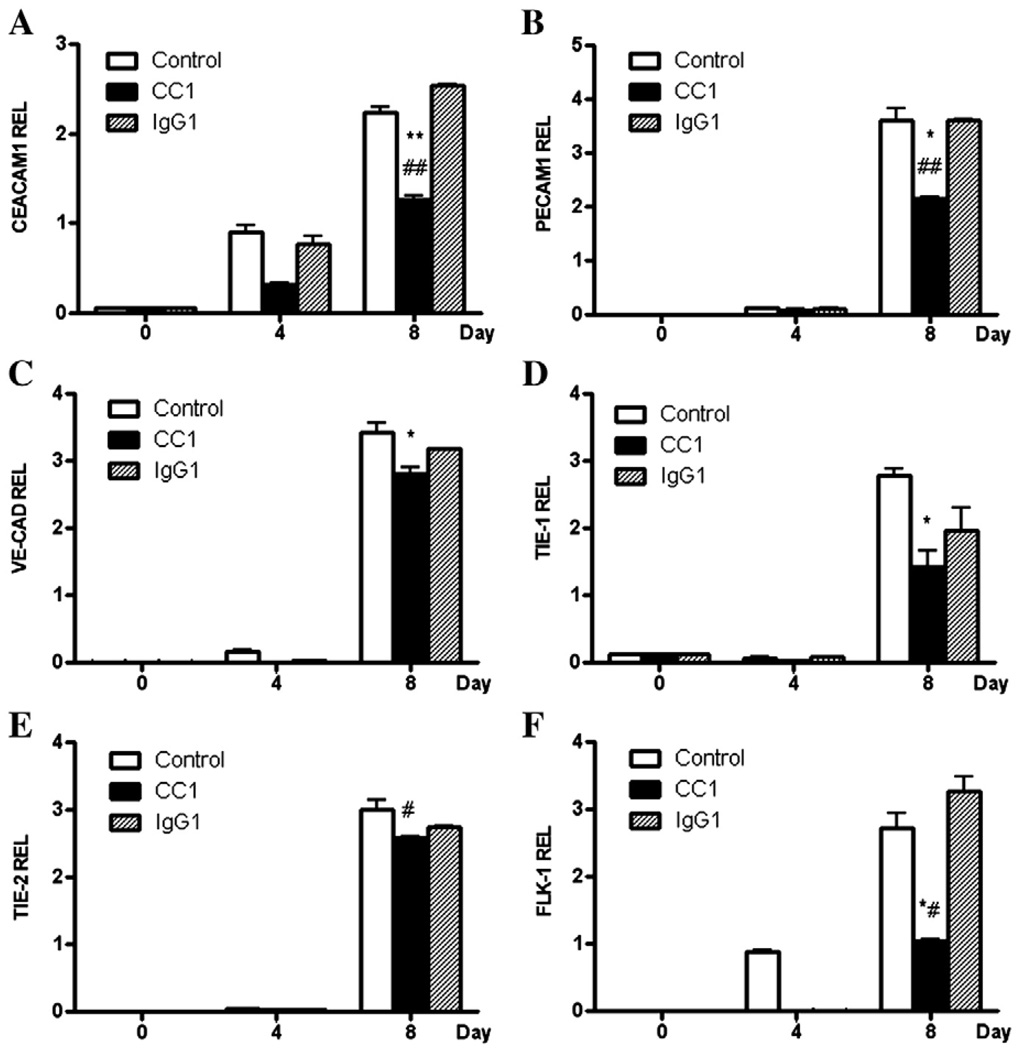

In addition, the ES cells treated with anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 or the isotype control were harvested at various time points and the expression levels of Ceacam1, Pecam1, VE-Cad, Tie-1/2, and Flk-1 were determined by QRT–PCR (Fig. 10). All of the mRNAs examined were significantly inhibited by CC1 mAb treatment at day 8 with the greatest inhibition observed for Ceacam1, Pecam1, and Flk1. The least amount of inhibition was seen for Tie-2, Ceacam1 and Flk-1 expression, but not for the other mRNAs, at day 4 and significantly inhibited by the CC1 mAb treatment. Notably, CC1 mAb has been shown to react to the N-terminal Ig-like domain of CEACAM1, the domain responsible for its homophillic cell adhesion function [34]. These results demonstrate that inhibition of the function of CEACAM1 by an N-terminal domain specific mAb inhibits the entire program of vasculogenesis as measured by the expression of Peacam1, VE-Cad, Tie-1/2, and Flk-1.

Fig. 10.

Inhibition of mRNA expression of Ceacam1, Pecam1, VE-Cad, Tie-1, and Flk-1 in anti-CEACAM1 treated EB. EBs grown in the presence of VEGF as described in Fig. 2 were transferred to Matrigel and treated with VEGF only (control), VEGF plus anti-CEACAM1 antibody (CC1), or VEGF plus isotype control antibody (IgG), the cells harvested at days 0, 4, and 8, and analyzed for Ceacam1 (A), Pecam1 (B), VE-Cad (C), Tie-1 (D), Tie-2 (E), and Flk-1 (F) by QRT–PCR in triplicate and the results reported relative to the housekeeping gene HRPT. (**, p<.001, *, p<.01 for CC1 compared to untreated; ##, p<.001, #, p<.01 for CC1 compared to isotype control treated).

Discussion

Although it seemed reasonable to us that CEACAM1may play a role in vasculogenesis based on its similar functions to PECAM1 and its observed role in angiogenesis, there were several arguments against this idea. The first was the reported negative staining for CEACAM1 in early embryos and the second was the fact that CEACAM1 knock-out mice developed normally. We addressed the first issue by re-examining early embryos at the stage of blood island formation and found strong staining for CEACAM1 directly at the blood islands precursor area. Notably, previous studies [18] missed this finding because the sections examined did not have blood islands in them. While this evidence does not prove a role for CEACAM1 in vasculogenesis, it makes it harder to rule out. The problem associated with the knock-outs also is true for PECAM-1 and reminds us of a general problem with making hard conclusions from negative data in knock-outs, namely that when nothing serious happens, it is possible that compensating systems may operate. Thus, to answer the question, we turned to an in vitro system utilizing ES cells and a 3D culture system. Based on other reports, the 3D Matrigel culture system appears to be an ideal model system for studying vasculogenesis in vitro. In our study, murine ES cells cultured in the presence of VEGF under conditions of conversion to EB began to express Ceacam1, Tie-2 and Flk-1 prior to the expression of other vascular markers such as Pecam1, VE-Cad, and Tie-1. Ceacam1 expression reached a maximum level at the time of complete differentiation into EB (day 0), suggesting that Ceacam1 expression is stimulated by EB differentiation. In contrast, other markers of endothelial cells (except Tie-2 and Flk-1) were mainly detected after EB transfer to Matrigel. This suggests that their expression is partly dependent upon exposure to extracellular matrix (ECM). Expression of Tie-2 is strongly down-regulated after transfer to Matrigel, unlike the other markers of endothelial cells (including Ceacam1), suggesting that it may be inhibited by ECM. Ceacam1 expression declined initially after EB transfer to Matrigel, but increased thereafter. These distinctive patterns of expression should allow us to sequence the order of gene expression in vasculogenesis. The expression levels of Ceacam1 and all of the other vasculogenesis marker genes, with the exception of Tie-2, were inhibited by anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1, suggesting that the entire vasculogenesis program has a feed-back mechanism that requires the expression of Ceacam1 for appropriate homophillic cell adhesion.

We also addressed the issues of the requirement for VEGF in our system, and whether or not additional growth factors present in Matrigel were necessary for vascular sprouting. When VEGF was omitted, vascular sprouting was still observed, suggesting that the ES cells were capable of making their own VEGF and that Matrigel may induce the production of VEGF. Furthermore, the use of dialyzed Matrigel, known to have reduced amounts of growth factors, also supported vascular sprouting. Future experiments will be directed at identifying the components of Matrigel responsible for VEGF production. In any case, vascular sprouting appears to be a default program for EB grown in Matrigel.

The inhibition of EB formation by anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 extends our observation from the previous experiments that show the early expression of CEACAM1 in VEGF treated ES cells. This result suggests that CEACAM1 plays a role in the differentiation of ES cells to EBs. Since CEACAM1 is a cell–cell adhesion molecule that can act as a co-receptor for other adhesion molecules such as integrin β3 [35], this result may not be entirely unexpected. Notably, PECAM1 regulates the signaling of integrin β3 in platelets [36], suggesting that CEACAM1 and PECAM1 have similar roles in signaling. We speculate that CEACAM1 functions in the early stages of ES aggregation and that other adhesion molecules take over after EB formation. Indeed, we show here that anti-PECAM1 antibodies also inhibit both the formation of EB from ES cells and the ability of EB to produce vascular sprouts when grown in Matrigel. Thus, CEACAM1 and PECAM1 may have supporting and/or interchangeable roles in vascular sprouting.

In comparing our results to the role of Ceacam1 in angiogenesis [11], several similarities emerge. First, Ceacam1 appears to play an essential and early role in endothelial sprouting. Second, endothelial sprouting is inhibited by anti-CEACAM1 mAbs. For example, an anti-human CEACAM1 mAb was also able to inhibit endothelial cell tube formation in a model of angiogenesis [9], and anti-murine CEACAM1 mAb CC1 inhibited endothelial cell sprouting in the Matrigel plug assay[11]. Third, endothelial sprouts stain positive for both CEACAM1 and PECAM1, suggesting that these two cell–cell adhesion molecules may play redundant roles in both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Fourth, the CEACAM1 isoform(s) responsible for both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis were the long cytoplasmic domain isoform(s). The significance of the long cytoplasmic domain includes its known interactions with actin [37,38], annexin II [39], calmodulin [40], SHP-1/2 [41], and β-catenin [32]. In particular, the interaction with β-catenin and SHP1/2 is perhaps the most striking similarity that exists between CEACAM1 and PECAM1. As mentioned earlier, VEGF has been shown to induce the phosphorylation of β-catenin in endothelial cells [33], and if PECAM1 is phosphorylated on its ITIM, it may recruit SHP-2 [42], which in turn can dephosphorylate β-catenin [43]. The net effect is proliferation of endothelial cells [44]. Whether or not CEACAM1 can perform a similar function in endothelial cells remains to be demonstrated. Fifth, we provide evidence that tube formation may involve apoptosis of central cells, in analogy to our findings in a 3D model of mammogenesis.

Although previous studies have demonstrated that VEGF treated murine or human ES cells or EB are capable of vascular sprouting [25,27,45] the mechanism of lumen formation was not explored. Since we observed apoptotic cells inside the vascular tubes, it is possible that the sprouts begin as solid tubes and form lumina by apoptotic loss of central cells. If this is the case, CEACAM1 may play a key role in vascular lumen formation, just as it does in the in vitro model of mammogenesis [19,20]. However, CEACAM1 could also play a broader role since treating EB with the anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1 blocked sprouting as well as lumen formation. The evidence for this is a significant inhibition of vascular sprouting by treatment of EB with anti-CEACAM1 mAb CC1. Thus, CEACAM1 appears to act early in the vascular program, even before lumen formation begins.

Although our study suggests that CEACAM1 plays an essential role in vasculogenesis, it is clear that vasculogenesis is unimpaired in Ceacam1−/− mice. Thus, it is likely that another molecule with redundant functions can substitute for CEACAM1 in vivo. A likely candidate is PECAM1 because it, like CEACAM1, comprises extracellular IgG domains with adhesive properties, has a cytoplasmic domain containing an ITIM, interacts with β-catenin, and is expressed on endothelial cells [15,43]. If this is the case, why didn't PECAM1 expression rescue the EB treated with anti-CEACAM1 antibody? A likely answer is that, at least in this model system, CEACAM1 is expressed prior to PECAM1 and that the disruption of CEACAM1 mediated adhesion down-regulated the entire vasculogenesis program including PECAM1 expression. In the developing embryo missing the Ceacam1 gene, compensating programs may develop. We hypothesize that in the Pecam1−/− mice [12,15], a similar compensation program may operate, where the Ceacam1 gene may substitute for Pecam1 functions. Thus, it is possible that vasculogenesis may be completely inhibited in double knock-out mice. Clearly, these are testable hypotheses, and if proven, will allow us to better order the genes involved in vasculogenesis.

Our study differs in several ways from previous work on murine ES/EB stimulated vasculogenesis. First, we have utilized a 3D environment rather than matrix coated plates. Our previous studies with mammogenesis [20,21] have convinced us that 2D environments are not as efficient and reproducible as 3D culture conditions in providing a physiological setting for cell differentiation. Although others have had some success with simple 2D culture conditions [4] or growth on Matrigel coated plates [25,27,45], one can see that the extent of endothelial cell sprouting is more extensive in the 3D setting. Second, we have followed the expression of Ceacam1 in the ES/EB system for the first time, thus demonstrating that the Ceacam1 gene has a role not only in angiogenesis, but also in vasculogenesis. Furthermore, we have shown that the extent of vasculogenesis and expression of key genes can be quantitated allowing one to more precisely delineate the effect of inhibitory antibodies. While much remains to be done, we have established a quantitative model that demonstrates the involvement of yet another key molecule in the overall process of vasculogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants CA84202 (JES) and AI-059576 (KH). We thank Sofia Loera for immunohistochemistry, Mariko Lee for confocal microscopy, John Hardy and Marcia Miller for electron microscopy. We also thank Christine Chen and Zhifang Zhang for their help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Risau W, Flamme I. Vasculogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1995;11:73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat. Med. 2003;9:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirashima M, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Matsuyoshi N, Nishikawa S. Maturation of embryonic stem cells into endothelial cells in an in vitro model of vasculogenesis. Blood. 1999;93:1253–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vittet D, Prandini MH, Berthier R, Schweitzer A, Martin-Sisteron H, Uzan G, Dejana E. Embryonic stem cells differentiate in vitro to endothelial cells through successive maturation steps. Blood. 1996;88:3424–3431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–365. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanks SK, Quinn AM. Protein kinase catalytic domain sequence database: identification of conserved features of primary structure and classification of family members. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:38–62. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00126-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407:242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto T, Mugishima H. Signal transduction via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors and their roles in atherogenesis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2006;13:130–135. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ergun S, Kilik N, Ziegeler G, Hansen A, Nollau P, Gotze J, Wurmbach JH, Horst A, Weil J, Fernando M, Wagener C. CEA-related cell adhesion molecule 1: a potent angiogenic factor and a major effector of vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira-Ferrer L, Tilki D, Ziegeler G, Hauschild J, Loges S, Irmak S, Kilic E, Huland H, Friedrich M, Ergun S. Dual role of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 in angiogenesis and invasion of human urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8932–8938. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horst AK, Ito WD, Dabelstein J, Schumacher U, Sander H, Turbide C, Brummer J, Meinertz T, Beauchemin N, Wagener C. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 modulates vascular remodeling in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1596–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI24340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan GS, Andrew DP, Takimoto H, Kaufman SA, Yoshida H, Spellberg J, Luis de la Pompa J, Elia A, Wakeham A, Karan-Tamir B, Muller WA, Senaldi G, Zukowski MM, Mak TW. Genetic evidence for functional redundancy of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1): CD31-deficient mice reveal PECAM-1-dependent and PECAM-1-independent functions. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3022–3030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng YS, Ramsauer M, Loureiro RM, D'Amore PA. Identification of genes involved in VEGF-mediated vascular morphogenesis using embryonic stem cell-derived cystic embryoid bodies. Lab. Invest. 2004;84:1209–1218. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solowiej A, Biswas P, Graesser D, Madri JA. Lack of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 attenuates foreign body inflammation because of decreased angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;162:953–962. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63890-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gratzinger D, Canosa S, Engelhardt B, Madri JA. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 modulates endothelial cell motility through the small G-protein Rho. FASEB J. 2003;17:1458–1469. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1040com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haar JL, Ackerman GA. A phase and electron microscopic study of vasculogenesis and erythropoiesis in the yolk sac of the mouse. Anat. Rec. 1971;170:199–223. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palis J, McGrath KE, Kingsley PD. Initiation of hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in murine yolk sac explants. Blood. 1995;86:156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniels E, Letourneau S, Turbide C, Kuprina N, Rudinskaya T, Yazova AC, Holmes KV, Dveksler GS, Beauchemin N. Biliary glycoprotein 1 expression during embryogenesis: correlation with events of epithelial differentiation, mesenchymal–epithelial interactions, absorption, and myogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 1996;206:272–290. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199607)206:3<272::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Hardy JD, Sun Y, Shively JE. Essential role of biliary glycoprotein (CD66a) in morphogenesis of the human mammary epithelial cell line MCF10F. J. Cell. Sci. 1999;112(Pt 23):4193–4205. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirshner J, Chen CJ, Liu P, Huang J, Shively JE. CEACAM1-4S, a cell–cell adhesion molecule, mediates apoptosis and reverts mammary carcinoma cells to a normal morphogenic phenotype in a 3D culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:521–526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232711199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CJ, Kirshner J, Sherman MA, Hu W, Nguyen T, Shively JE. Mutation analysis of the short cytoplasmic domain of the cell-cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1 identifies residues that orchestrate actin binding and lumen formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:5749–5760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaBarge MA, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Of microenvironments and mammary stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:137–146. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rust WL, Sadasivam A, Dunn NR. Three-dimensional extracellular matrix stimulates gastrulation-like events in human embryoid bodies. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:889–904. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levenberg S, Golub JS, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Langer R. Endothelial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:4391–4396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032074999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou X, Gallicano GI. Microvascular tubes derived from embryonic stem cells sustain blood flow. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:335–347. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dveksler GS, Pensiero MN, Dieffenbach CW, Cardellichio CB, Basile AA, Elia PE, Holmes KV. Mouse hepatitis virus strain A59 and blocking antireceptor monoclonal antibody bind to the N-terminal domain of cellular receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:1716–1720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fathi F, Kermani AJ, Pirmoradi L, Mowla SJ, Asahara T. Characterizing endothelial cells derived from the murine embryonic stem cell line CCE. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:371–378. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakagami H, Nakagawa N, Takeya Y, Kashiwagi K, Ishida C, Hayashi S, Aoki M, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Ogihara T, Morishita R. Model of vasculogenesis from embryonic stem cells for vascular research and regenerative medicine. Hypertension. 2006;48:112–119. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000225426.12101.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metcalf DJ, Nightingale TD, Zenner HL, Lui-Roberts WW, Cutler DF. Formation and function of Weibel–Palade bodies. J. Cell. Sci. 2008;121:19–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babich V, Meli A, Knipe L, Dempster JE, Skehel P, Hannah MJ, Carter T. Selective release of molecules from Weibel–Palade bodies during a lingering kiss. Blood. 2008;111:5282–5290. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robitaille J, Izzi L, Daniels E, Zelus B, Holmes KV, Beauchemin N. Comparison of expression patterns and cell adhesion properties of the mouse biliary glycoproteins Bbgp1 and Bbgp2. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;264:534–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin L, Li Y, Chen CJ, Sherman MA, Le K, Shively JE. Direct interaction of tumor suppressor CEACAM1 with beta catenin: identification of key residues in the long cytoplasmic domain. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2008;233:849–859. doi: 10.3181/0712-RM-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilan N, Mahooti S, Rimm DL, Madri JA. PECAM-1 (CD31) functions as a reservoir for and a modulator of tyrosine-phosphorylated beta-catenin. J. Cell. Sci. 1999;112(Pt 18):3005–3014. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.18.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan K, Zelus BD, Meijers R, Liu JH, Bergelson JM, Duke N, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Holmes KV, Wang JH. Crystal structure of murine sCEACAM1a[1,4]: a coronavirus receptor in the CEA family. EMBO J. 2002;21:2076–2086. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brummer J, Ebrahimnejad A, Flayeh R, Schumacher U, Loning T, Bamberger AM, Wagener C. Cis interaction of the cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1 with integrin beta(3) Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159:537–546. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61725-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wee JL, Jackson DE. The Ig-ITIM superfamily member PECAM-1 regulates the “outside–in” signaling properties of integrin alpha(IIb)beta3 in platelets. Blood. 2005;106:3816–3823. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schumann D, Chen CJ, Kaplan B, Shively JE. Carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1 directly associates with cytoskeleton proteins actin and tropomyosin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47421–47433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadekova S, Lamarche-Vane N, Li X, Beauchemin N. The CEACAM1-L glycoprotein associates with the actin cytoskeleton and localizes to cell–cell contact through activation of Rho-like GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:65–77. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirshner J, Schumann D, Shively JE. CEACAM1, a cell–cell adhesion molecule, directly associates with annexin II in a three-dimensional model of mammary morphogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:50338–50345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edlund M, Blikstad I, Obrink B. Calmodulin binds to specific sequences in the cytoplasmic domain of C-CAM and down-regulates C-CAM self-association. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1393–1399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huber M, Izzi L, Grondin P, Houde C, Kunath T, Veillette A, Beauchemin N. The carboxyl-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein–tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:335–344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson DE, Kupcho KR, Newman PJ. Characterization of phosphotyrosine binding motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) that are required for the cellular association and activation of the protein–tyrosine phosphatase. SHP-2, J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24868–24875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biswas P, Canosa S, Schoenfeld D, Schoenfeld J, Li P, Cheas LC, Zhang J, Cordova A, Sumpio B, Madri JA. PECAM-1 affects GSK-3beta-mediated beta-catenin phosphorylation and degradation. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:314–324. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biswas P, Canosa S, Schoenfeld J, Schoenfeld D, Tucker A, Madri JA. PECAM-1 promotes beta-catenin accumulation and stimulates endothelial cell proliferation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;303:212–218. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyd NL, Dhara SK, Rekaya R, Godbey EA, Hasneen K, Rao RR, West FD, III, Gerwe BA, Stice SL. BMP4 promotes formation of primitive vascular networks in human embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2007;232:833–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller G, Kennedy M, Papayannopoulou T, Wiles MV. Hematopoietic commitment during embryonic stem cell differentiation in culture. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:473–486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie Y, Muller WA. Molecular cloning and adhesive properties of murine platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:5569–5573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sato TN, Qin Y, Kozak CA, Audus KL. Tie-1 and tie-2 define another class of putative receptor tyrosine kinase genes expressed in early embryonic vascular system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:9355–9358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voskas D, Jones N, Van Slyke P, Sturk C, Chang W, Haninec A, Babichev YO, Tran J, Master Z, Chen S, Ward N, Cruz M, Jones J, Kerbel RS, Jothy S, Dagnino L, Arbiser J, Klement G, Dumont DJ. A cyclosporine-sensitive psoriasis-like disease produced in Tie2 transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;166:843–855. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62305-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oelrichs RB, Reid HH, Bernard O, Ziemiecki A, Wilks AF. NYK/FLK-1: a putative receptor protein tyrosine kinase isolated from E10 embryonic neuroepithelium is expressed in endothelial cells of the developing embryo. Oncogene. 1993;8:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]