Abstract

Study Design

Analysis of baseline data for patients enrolled in SPORT, a project conducting three randomized and three observational cohort studies of surgical and non-operative treatments for intervertebral disc herniation (IDH), spinal stenosis (SpS), and degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS).

Objective

To explore racial variation in treatment preferences and willingness to be randomized.

Summary of Background Data

Increasing minority participation in research has been a priority at the NIH. Prior studies have documented lower rates of participation in research and preferences for invasive treatment among African Americans.

Methods

Patients enrolled in SPORT (March 2000-February 2005) that reported data on their race (n=2323) were classified as White (87%), Black (8%) or Other (5%). Treatment preferences (non-operative, unsure, surgical), and willingness to be randomized were compared among these groups while controlling for baseline differences using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

There were numerous significant differences in baseline characteristics among the racial groups. Following adjustment for these differences, Blacks remained less likely to prefer surgical treatment among both IDH (White: 55%, Black: 37%, Other: 55%, p=0.023) and SpS/DS (White: 46%, Black: 30%, Other: 43%, p=0.017) patients. Higher randomization rates among Black IDH patients (46% vs. 30%) were no longer significant following adjustment (OR=1.45, p=0.235). Treatment preference remained a strong independent predictor of randomization in multivariate analyses for both IDH (unsure OR = 3.88, p<0.001 and surgical OR=0.23, p<0.001) and SpS/DS (unsure OR = 6.93, p<0.001 and surgical OR= 0.45, p<0.001) patients.

Conclusions

Similar to prior studies, Black participants were less likely than Whites or Others to prefer surgical treatment; however, they were no less likely to agree to be randomized. Treatment preferences were strongly related to both race and willingness to be randomized.

Keywords: Spinal Stenosis, Degenerative Spondylolisthesis, Intervertebral Disc Herniation, treatment preference, willingness to randomize, racial variation, surgical treatment, clinical trial

BACKGROUND

Ten years ago, legislation was passed that mandated the inclusion of women and minorities in NIH-funded biomedical and behavioral research with human subjects. 1 For phase III clinical trials, women and minorities are supposed to be enrolled in adequate numbers to ensure valid analyses of differences in intervention effects. 1 Few studies are able to fulfill this mandate and concerns have been raised that the NIH policy may be ineffective or even that it may be doing more harm than good. 2

Recruiting large numbers of minorities into research studies is complicated because these groups by definition comprise a minority of the population. In addition, lower rates of willingness to participate in medical research studies among minority groups have been reported. 3,4 Some possible reasons underlying these differences include: distrust of medical research due to the history of racially biased/unethical studies;3,5-7 the belief that racial minorities have borne a disproportionate share of the burden for testing new treatments; preferences toward risk;4,5 perceptions of traditional and alternative treatment modalities; 4; and socioeconomic barriers to participation.6-13

The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) is an NIH-funded study that is being conducted at 11 clinical centers around the United States. It involves the simultaneous conduct of three randomized clinical trials comparing surgical and non-operative treatments for patients with intervertebral disc herniation (IDH), spinal stenosis (SpS), or degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS). Patients who meet the eligibility criteria but decline to be randomized are invited to participate in a parallel observational cohort study. Details of the design of the project, including recruitment, eligibility criteria, treatment and follow-up procedures have been published previously.14 In this study, we used data collected from SPORT participants at baseline to explore racial variation in treatment preferences and willingness to be randomized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

This analysis includes a total of 2,323 subjects that were enrolled in SPORT between March 2, 2000 and February 28, 2005 and who provided data regarding their race/ethnic background. Other baseline characteristics that we examined in this analysis include: age; sex; body mass index (BMI); education; income; work/legal status; smoking history; comorbidity; back-related symptoms (frequency or how often the symptom recurs; duration or length of time the system persist once it begins; and bothersomeness or intensity of the pain); Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score; Health Utilities Index (HUI) score; and physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component summary scores for the SF-36.

Race/Ethnic Categories

Patient race/ethnic background is self-recorded at baseline using categories as specified in the NIH guidelines on inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research. 1 These categories include two ethnic categories and six race categories. Due to small numbers of patients in some of the race/ethnic categories, we grouped patients into the following three categories for this analysis: White (White race/ not Hispanic or Latino ethnicity), Black (Black/African American race/not Hispanic or Latino ethnicity), and Other (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, more than one race/Hispanic or Latino ethnicity). Data on the racial composition of the SPORT site hospital referral regions was obtained from The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. 15 Data on the racial composition of the U.S. population was obtained from the U.S. Census. 16

Treatment Preferences

SPORT participants are asked about their current treatment preferences (definitely non-operative, probably non-operative, not sure, probably surgery, definitely surgery) at baseline. For the purposes of this analysis, we grouped the “definitely” and “probably” response categories to form three treatment preference groups (non-operative, unsure, and surgical). In addition, participants are asked what factors most influence their treatment preferences. Response categories include:

How my personal doctor thinks my spine-related problem should be treated

How my family thinks my spine-related problem should be treated

The advice or experience of friends

My ability to work or go about my usual daily activities

My ability to participate in and enjoy my usual leisure activities

Not wanting to be a burden to my family

Worries about money

Concerns about the potential risks of surgery

Worries about potential side effects or risks of addiction with pain medications

Non-operative treatment has not been effective for me

Other.

Willingness to be Randomized

Willingness to be randomized is assessed by the subject’s actual decision to participate in the randomized trial as opposed to the observational cohorts. This decision is made following an informed consent process which included discussions about: the purpose of the study; any potential benefit from the study; what type of treatment and length of time the study involves; risks associated; patient confidentiality; data collection; withdrawal from the study; patient access to research records; number of participants; contact person; cost of the study; enrollment incentive; and liability of research related injury or illness. Before being asked to agree to participate, patients are asked to review one of two SPORT shared decision making videos14,17,18 that discuss the possible outcome of surgery and non-operative treatment of back pain . The SPORT Nurse Coordinator reviews the informed consent with the patient before the participants sign it.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and health status characteristics were summarized using proportions for categorical variables and medians with inter-quartile ranges for continuous variables. Unadjusted comparisons were made between racial categories using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis rank tests for continuous variables.

Adjusted analyses for comparing rates of participation in the RCT versus the observational cohort, treatment preferences and factors that influence treatment preferences among racial groups were performed using multiple logistic regression for binary or polytomous categorical data.19 Variables identified from the initial analyses of the demographic factors were included as covariates in the multiple regression. Logistic regression parameter estimates and covariance matrices for the logistic regression parameters were used to test the global hypothesis of no difference between the odds or cumulative odds associated with the racial categories. Pairwise tests were performed to compare the White category to the Black and Other categories.

RESULTS

Racial/Ethnic Composition of the SPORT population

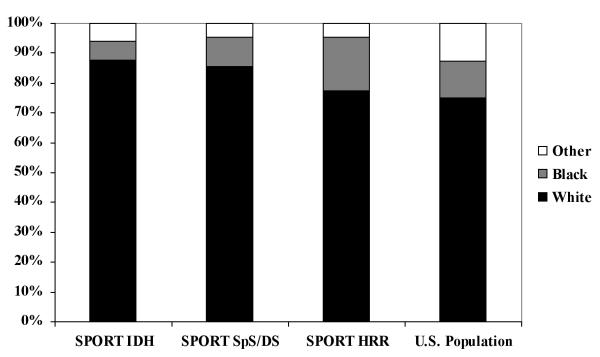

The SPORT population includes 2,011 (86.5%) Whites, 182 (7.8%) Blacks, and 130 (5.6%) Others (50 Hispanic/Latino, 11 American Indian/Alaska Native, 25 Asian, 6 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 38 More Than One Race). The SPORT population (Figure 1) has a smaller proportion of Blacks (6.13% IDH/ 9.57% SpS/DS) compared to that of the Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs) from which SPORT patients are drawn (17.8%) or the U.S. population as a whole (12.3%). The proportion of patients in the Other category (6.13% IDH/ 5.13% SpS/DS) is slightly higher than that of the hospital referral population (4.7%) but considerably lower than that of the U.S. population as a whole (12.6%).

Characteristics at Baseline

The demographic and medical history characteristics of the SPORT population are compared among the three racial groups in Table 1. Age, sex, BMI, education, income, marital status, and work/legal status were significantly associated with racial group. Mean age was lower (p=0.014) for Others (49 years) compared to Whites and Blacks (both 54 years). A greater proportion of Blacks were male (36.8%) than among Whites (52.8%) and Others (51.5%, p<0.001). Median BMI was higher (p<0.001) among Blacks (28.8) and Others (27.4) than among Whites (26.8). Blacks were less likely to have a college or graduate degree (Black: 60.2%, White: 70.6%, Other: 70.0%, p=0.014), more likely to have no job (Black: 40.7%, White: 34.5%, Other: 34.6%) and more likely to earn less than $20,000 per year if they did have a job than Whites and Others (Black: 24.2%, White: 16.2%, Other: 13.8%, p<0.001). Black subjects were more likely (p<0.001) to report having hypertension (51.8%) compared to Whites (28.6%) and Others (24.6%) and were more likely (p<0.001) to report having diabetes (17.0%) than Whites (8.2%) or Others (10.0%). Blacks were also more likely (p=0.039) to have joint problems (46.2%) than Whites (36.6%) and Others (34.6%). Other subjects were more likely (p=0.024) to report stomach problems (25.4%) than either Whites (16.6%) or Blacks (19.8%).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Racial Group

| Characteristic | White (N=2011) |

Black/African- American (N=182) |

Other (N=130) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic: | |||||

| Age | 54.0 (40.0, 68.0) | 54.0 (43.0, 65.0) | 49.0 (36.0, 61.0) | 0.014 | |

| Sex (Male) | 1062 (52.8%) | 67 (36.8%) | 67 (51.5%) | <0.001 | |

| BMI | 26.8 (23.7, 30.4) | 28.8 (25.6, 33.1) | 27.4 (24.0, 29.8) | <0.001 | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 590 (29.4%) | 72 (39.8%) | 39 (30.0%) | 0.014 | |

| Some college | 1419 (70.6%) | 109 (60.2%) | 91 (70.0%) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/living with significant other |

1444 (71.8%) | 95 (52.2%) | 84 (64.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Divorced | 181 (9.0%) | 37 (20.3%) | 20 (15.4%) | ||

| Widowed | 163 (8.1%) | 22 (12.1%) | 5 (3.8%) | ||

| Single | 223 (11.1%) | 28 (15.4%) | 21 (16.2%) | ||

| Personal income | |||||

| No job | 693 (34.5%) | 74 (40.7%) | 45 (34.6%) | <0.001 | |

| >$20,000 /yr | 325 (16.2%) | 44 (24.2%) | 18 (13.8%) | ||

| $20 −49,999 /yr | 458 (22.8%) | 38 (20.9%) | 43 (33.1%) | ||

| >= $50,000 /yr | 535 (26.6%) | 26 (14.3%) | 24 (18.5%) | ||

| Work/Legal status: | |||||

| Legal case | 71 (3.5%) | 20 (11.0%) | 22 (16.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Medical history: | |||||

| Smoking status | Yes | 332 (16.5%) | 41 (22.5%) | 21 (16.2%) | 0.067 |

| Not now, but in past | 724 (36.0%) | 62 (34.1%) | 36 (27.7%) | ||

| Never smoked | 955 (47.5%) | 79 (43.4%) | 73 (56.2%) | ||

| Comorbidity | Hypertension | 579 (28.8%) | 93 (51.1%) | 32 (24.6%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 164 (8.2%) | 31 (17.0%) | 13 (10.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Stomach problem | 333 (16.6%) | 36 (19.8%) | 33 (25.4%) | 0.024 | |

| Joint problem | 736 (36.6%) | 84 (46.2%) | 45 (34.6%) | 0.031 | |

| Back-related: | |||||

| Diagnosis | DS | 478 (23.8%) | 58 (31.9%) | 23 (17.7%) | 0.011 |

| IDH | 1021 (50.8%) | 71 (39.0%) | 71 (54.6%) | ||

| SPS | 512 (25.5%) | 53 (29.1%) | 36 (27.7%) | ||

| Duration | 6 weeks or less | 161 (8.0%) | 10 (5.5%) | 7 (5.4%) | 0.35 |

| 7-12 weeks | 290 (14.4%) | 17 (9.3%) | 19 (14.6%) | ||

| 3-6 months | 758 (37.7%) | 74 (40.7%) | 54 (41.5%) | ||

| 7-12 months | 374 (18.6%) | 43 (23.6%) | 21 (16.2%) | ||

| 1-2 years | 224 (11.1%) | 16 (8.8%) | 17 (13.1%) | ||

| 2-3 years | 95 (4.7%) | 7 (3.8%) | 6 (4.6%) | ||

| 3 years + | 109 (5.4%) | 15 (8.2%) | 6 (4.6%) | ||

| Health-related Quality of Life: | |||||

| Bothersomeness | 19.0 (14.0, 24.0) | 19.0 (15.0, 25.0) | 22.0 (15.0, 26.0) | 0.001 | |

| Frequency | 19.0 (14.0, 24.0) | 20.0 (15.0, 25.0) | 22.0 (16.0, 27.0) | <0.001 | |

| ODI | 44.0 (31.0, 60.0) | 49.0 (35.0, 64.0) | 49.0 (33.0, 65.0) | 0.016 | |

| SF-36 | Physical component summary |

29.3 (24.1, 35.2) | 27.2 (22.5, 32.5) | 27.9 (23.9, 33.8) | <0.001 |

| SF-36 | Mental component summary |

49.1 (38.6, 57.2) | 45.7 (36.8, 55.8) | 43.2 (34.8, 54.1) | 0.001 |

Diagnosis and quality of life characteristics are compared among the racial groups in Table 1. There were significant differences in diagnosis among the racial/ethnic categories, with 50.8% of Whites diagnosed with IDH, 25.5% with SpS, and 23.8% with DS compared to 39.0% IDH, 29.1% SpS, 31.9% DS for Blacks, and 54.6% IDH, 27.7% SpS, 17.7% DS for Others (p=0.011). Back symptoms were less bothersome (p=0.001) and less frequent (p<0.001) among White subjects compared to Blacks and Others (p=0.001). Whites had higher median SF-36 physical (p=0.001) and mental (p=0.001) component summary scores and lower median ODI scores (P=0.016) than Blacks or Others. (NOTE: The lower score on ODI indicates less disability, whereas a higher score on the SF-36 means less pain, less mental distress, etc).

Having a Worker’s Compensation claim, time since quitting smoking, history of stroke, osteoporosis, cancer, fibromyalgia, migraine headaches, chronic fatigue syndrome, depression, anxiety/panic disorder, PTSD, alcoholism, drug dependency, heart problems, lung problems, stomach problems, bowel/intestinal problems, liver problems, kidney problems, blood vessel problems, nervous system problems and duration of low back/leg pain were not significantly associated with racial groups.

Univariate Analyses

In univariate analyses (Table 2), treatment preferences varied significantly among the racial groups overall (p=0.008). Blacks were less likely to prefer surgical treatment (33.0%) compared to Whites (46.6%) and Others (43.8%). These relationships persisted within each of the diagnosis groups but were less statistically significant. Overall, Others were the group most willing to be randomized (47.7%) compared to Whites (42.9%) and Blacks (45.1%) but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.50). Among patients diagnosed with SpS/DS, Others were the group most willing to be randomized (54.2%) compared to Whites (46.6%) and Blacks (42.3%), while among patients diagnosed with IDH, Black subjects were more willing (49.3%) to be randomized than Whites (39.3%) or Others (42.3%). None of these differences reached statistical significance.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Treatment Preferences and Willingness to be Randomized Rates by Diagnosis and Racial Group

| Outcome | Racial group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Preference Group | White | Black | Other | p-value |

| Willingness to be Randomized (% Yes) | ||||

| Overall | 42.9% | 45.1% | 47.7% | 0.50 |

| IDH | 39.3% | 49.3% | 42.3% | 0.23 |

| SpS/DS | 46.6% | 42.3% | 54.2% | 0.33 |

| Treatment Preference (% Yes) | ||||

| Overall | ||||

| Non-operative | 34.7% | 45.1% | 33.8% | 0.008 |

| Unsure | 18.7% | 22.0% | 22.3% | |

| Surgical | 46.6% | 33.0% | 43.8% | |

| IDH | ||||

| Non-operative | 32.6% | 46.5% | 31.0% | 0.080 |

| Unsure | 16.4% | 18.3% | 21.1% | |

| Surgical | 51.0% | 35.2% | 47.9% | |

| SpS/DS | ||||

| Non-operative | 36.8% | 44.1% | 37.3% | 0.30 |

| Unsure | 21.1% | 24.3% | 23.7% | |

| Surgical | 42.1% | 31.5% | 39.0% |

Multivariate Analyses

Treatment preferences adjusted for baseline differences are compared among the racial groups. Black subjects were less likely than Whites or Others to prefer surgical treatment among both IDH (White=51.0%, Black=35.2%, Other=47.9%,) and SpS/DS (White=42.1%, Black=31.5%, Other=39.0%,) patients (Table 2) We also examined factors which influenced treatment preferences within diagnosis among the racial groups. In adjusted analyses, significant differences between the racial groups were observed for the following factors: Among the IDH patients ability to enjoy usual leisure activities (White=48.0%, Black=33.6%, Other=36.2%, p=0.027); worries about money (White=6.6%, Black=13.2%, Other=1.4%, p=0.007); and risks of surgery (White=23.4%, Black=33.1%, Other=39.0%, p=0.010). For SpS/DS patients, advice or experience of friends (White=5.2%, Black=12.7%, Other=10.5%, p=0.047); ability to work (White=72.2%, Black=60.5%, Other=62.6%, p=0.035); ability to enjoy usual leisure activities (White=53.9%, Black=41.6%, Other=31.4%, p=0.007) ; risk of surgery (White=29.1%, Black=41.7%, Other=37.3%, p=0.034; and non-operative treatment being ineffective (White=25.9%, Black=15.6%, Other=21.1%, p=0.058) varied significantly among the racial groups.

Willingness to be Randomized

The results of multivariate analyses designed to assess the independent effects of race and treatment preference on willingness to be randomized while controlling for baseline differences among the race groups is shown in Table 3. In this analysis, race was no longer a significant predictor of willingness to randomize in either IDH (OR=1.13 for Blacks compared to Whites, p=0.66; OR=1.02 for Others, p=0.95) or SpS/DS (OR=0.71 for Blacks, p=0.16; OR=1.44 for Others, p=0.24) patients. Treatment preference remained a significant, strong predictor of willingness to randomize in both diagnostic groups. Compared to patients with a baseline preference for non-operative treatment, those who were unsure were much more likely (OR=3.60 for IDH, p<0.001; OR=5.31 for SpS/DS, p<0.001) to agree to be randomized. Those who preferred surgical treatment were much less likely (OR=0.25 for IDH, p<0.001; OR=0.40 for SpS/DS, p<0.001) to agree to be randomized compared to those who preferred non-operative treatment.

Table 3.

Willingness to be Randomized (Adjusted Odds Ratios) by Racial Group and Treatment Preference at Baseline

| Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

| IDH | ||||

| Racial Group | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 1.13 | 0.64 | 2.00 | 0.66 |

| Other | 1.02 | 0.58 | 1.80 | 0.95 |

| Treatment Preference | ||||

| Non-operative | Reference | |||

| Unsure | 3.60 | 2.39 | 5.42 | <0.001 |

| Surgery | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| SpS/DS | ||||

| Racial Group | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.71 | 0.45 | 1.14 | 0.16 |

| Other | 1.44 | 0.79 | 2.63 | 0.24 |

| Treatment Preference. | ||||

| Non-operative | Reference | |||

| Unsure | 5.31 | 3.62 | 7.80 | <0.001 |

| Surgery | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.54 | <0.001 |

Model-based estimates are adjusted for: age, gender, BMI, education, income, marital status, legal status, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, stomach problems, joint problems, episode duration, bothersomeness, frequency, ODI, SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS. (These are all variables significant at p<0.1 in the univariate analyses for the overall study pulation). The same set of predictors was used for both IDH and SpS/DS analyses.

DISCUSSION

The recruitment of minorities into SPORT has been a priority throughout the design and conduct of the project. SPORT clinical sites were selected from a range of geographic locations with a mix of urban, suburban, and rural populations in order to provide a racially /ethnically diverse patient population. In addition, the SPORT protocol requires that all subjects who are eligible for the study be invited to participate regardless of race/ethnic background. Targeted advertisement of the trial was also undertaken on a local level to try to insure adequate minority enrollment. Despite these efforts, minority groups are underrepresented in SPORT as they have been in many prior clinical trials. 20-23

The relative lack of racial/ethnic diversity in the SPORT population may be at least partially attributable to the epidemiology of the conditions that are under investigation. For example, a number of studies have indicated a lower prevalence of low back pain among Blacks as compared to Whites. 24,25 On the other hand, it has been reported that DS occurs more frequently in Blacks than in non-Hispanic Whites. 26

Similar to our findings, patient preferences for invasive procedures have been shown to vary according to race for many different medical conditions. Specifically, African American Blacks have been shown to be less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to prefer invasive treatments for cardiovascular disease, 27-29 cerebrovascular disease, 30 osteoarthritis, 4,31 and end-stage renal disease. 32 Few studies have explicitly investigated the origins of these differences. Some possible explanations include racial differences in how the risks and benefits of invasive treatment are perceived, in predilections for alternative/self-care, and in socioeconomic status/access to health care. 32,33

Low rates of minority participation have been documented in clinical trials for numerous conditions such as cardio-/cerebrovascular disease, 11 cancer, 34 and HIV/AIDS. 35,36 A number of studies have focused on the deleterious effects of prior unethical research studies on rates of minority participation in research. Ironically, the purpose of the informed consent process, which was created to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects, has been reported to discourage minority participation in research. Researchers have found that minorities frequently misinterpret informed consent language as liability protection for the researchers. 37,38 Other barriers to minority participation in research that have been identified in prior studies and which may contribute to the lack of racial diversity in SPORT include a lack of awareness about clinical trials due to the ineffectiveness/paucity of outreach efforts, socioeconomic/access barriers, and language/cultural issues. 11 To their credit, some investigators made attempts to achieve higher minority enrollment through very localized efforts.

In contrast to the findings of prior studies, Black SPORT participants were not less likely than Whites or Others to agree to be randomized. In fact, among IDH patients, Blacks showed a trend toward being more willing to be randomized than the other race groups. This effect may have been mediated through treatment preferences. In our study, treatment preferences at baseline were strongly predictive of willingness to randomize. Not surprisingly, patients whose preference was unsure were more likely than those whose preference was non-operative treatment to agree to be randomized. On the other hand, patients whose treatment preference was for surgery were much less likely than those preferring non-operative treatment to agree to be randomized.

One of the strengths of our study is the inclusion of both randomized and observational arms for each of the three diagnoses under investigation in SPORT. Unfortunately, we do not have information about the racial composition of the patients who refused to participate or about perceived discrimination by participants. The racial concordance between research coordinators and subject, subjects’ trust in the healthcare system, and their understanding of the consent process was not measured and therefore the potential influence of these factors on enrollment could not be assessed; this is a limitation of the study.

The results of this study add to the evidence regarding racial differences in treatment preferences. Black participants in SPORT were much less likely to prefer surgical treatment for their back pain. However, in contrast to prior studies, Black participants in SPORT were no less likely than Whites or Others to agree to be randomized. Treatment preferences were strongly related to both race and willingness to randomize.

SPORT Sites.

- Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center

- William A Abdu, MD, MS

- Barbara Butler-Schmidt, RN, MSN; JJ Hebb, RN, BSN

- Emory University-The Emory Clinic

- Scott Boden, MD

- Sally Lashley, BSN, MSA

- Hospital for Joint Diseases

- Thomas Errico, MD

- Alex Lee, RN, BSN

- Hospital for Special Surgery

- Frank Cammisa, MD

- Brenda Green, RN, BSN

- Kaiser-Permanente

- Harley Goldberg, DO

- Pat Malone, RN, MSN, ANP

- Maine Spine & Rehabilitation

- Robert Keller, MD

- Nebraska Foundation for Spinal Research

- Michael Longley, MD

- Nancy Fullmer, RN; Ann Marie Fredericks, RN, MSN, CPNP

- Rothman Institute at Thomas Jefferson Hospital

- Todd Albert, MD

- Allan Hilibrand, MD

- Carole Simon, RN, MS

- Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s

- Gunnar Andersson, MD, PhD

- Margaret Hickey, RN, MS

- University Hospitals of Cleveland/Case-Western-Reserve

- Chris Furey, MD

- Kathy Higgins, RN, PhD, CNS, C

- University of California—San Francisco

- Serena Hu, MD

- Pat Malone, RN, MSN, ANP

- Washington University

- Lawrence Lenke, MD

- Georgia Stobbs, RN, BA

- William Beaumont Hospital

- Harry Herkowitz, MD

- Gloria Bradley, BSN; Melissa Lurie, RN

KEY POINTS.

Analyses were performed to explore racial variation in surgical treatment preference and willingness to be randomized for intervertebral disc herniation (IDH), spinal stenosis (SpS), and degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS) patients.

Blacks were less likely to prefer surgical treatment among the IDH, SpS, and DS patients. There was a higher randomization rate among Black IDH patients.

After controlling for baseline differences, treatment preferences remained a strong predictor of randomization in IDH, SpS, and DS patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the following sources: The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U01-AR45444-01A1) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. Dr. Birkmeyer is supported by an award from AHRQ (K02 HS11288). Dr. Lurie is supported by a Research Career Award from NIAMS (1 K23 AR 048138-01).

This study is dedicated to the memory of Brieanna Weinstein.

REFERENCES

- 1.NIH Policy and Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities As Subjects in Clinical Research - Amended, October, 2001 [National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research] 2001 Available at: http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm.

- 2.Vastag B. Researchers say changes needed in recruitment policies for NIH trials. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:536–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shavers V, Lynch C, Burmeister L. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:248–56. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim S, Siminoff L, Burant C, Kwoh C. Differences in expectations of outcome mediate African American/White patient differences in “willingness” to consider joint replacement. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2002;46:2429–35. doi: 10.1002/art.10494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gamble V. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1773–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson L. New York Times. New York: 1997. Experiment leaves legacy of distrust of new AIDS drugs; p. 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanson G, Ward A. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: Toward a participant-friendly system. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87:17447–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson J, Weinberger M, Westmoreland G, Mamlin L, Segar D, Greene J, Martin D, Tierney W. Racial disparity in cardiac decision making: Results from patient focus groups. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1450–3. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.13.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberson N. Clinical trial participation: Viewpoints from racial/ethnic groups. Cancer. 1994;74:2687–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9+<2687::aid-cncr2820741817>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kressin N, Meterko M, Wilson N. Racial disparities in participation in biomedical research. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92:62–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris Y, Gorelick P, Samuels P, Bempong I. Why African Americans may not be participating in clinical trials. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1996;88:630–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorelick P, Harris Y, Burnett B, Bonecutter F. The recruitment triangle: Reasons why African Americans enroll, refuse to enroll, or voluntarily withdraw from a clinical trial. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1998;90:141–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feussner J. Understanding the dynamics between ethnicity and health care: Another role for health services research in chronic disease management. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2002;46:2265–7. doi: 10.1002/art.10501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birkmeyer N, Weinstein J, Tosteson A, Tosteson T, Skinner J, Lurie J, Deyo R, Wennberg J. Design of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2002;27:1361–72. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper M. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in the United Statesed. American Hospital Publishing, Inc.; Chicago, IL: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Population Profile of the United States: 2000. Chapter 2. All Across the U.S.A.: Population Distribution and Composition, 2000 [U.S. Census Bureau] 2000 Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/profile2000.html.

- 17.Treatment Choices for Low Back Pain: Herniated Disc. Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making; Boston, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treatment Choices for Low Back Pain: Spinal Stenosis. Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making; Boston, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysised. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gavaghan H. Clinical trials face lack of minority group volunteers. Nature. 1995;373:178. doi: 10.1038/373178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svensson C. Representation of American blacks in clinical trials of new drugs. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261:263–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen A. The dilemma of women of color in clinical trials. Journal of the American Modern Women’s Association. 1994;49:105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas C, Pinto H, Ronch M, Vaughn C. Participation in clinical trials: Is it state-of-the-art treatment for African Americans and other people of color? Journal of the National Medical Association. 1994;88:177–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shekelle P, Markovich M, Louie R. An epidemiologic study of episodes of back pain care. Spine. 1995;20:1668–73. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199508000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyo R, Tsui-Wu Y. Descriptive epidemiology of low bakc pain and its related medical care in the United States. Spine. 1987;12:264–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg N. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: Predisposing factors. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1975;57:467–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maynard C, Fisher L, Passamani E, Pullum T. Blacks in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS): Race and clinical decision making. American Journal of Public Health. 1986;76:1446–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.12.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schecter A, Gldschmidt-Clermont P, McKee G. Influence of gneder, race, and education on patient preferences and receipt of cardiac catheterizations among coronary care unit patients. American Journal of Cardiology. 1996;78:996–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whittle J, Conigliaro J, Good C, Joswiak M. Do patient preferences contribute to racial differences in cardiovascular procedure use? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:267–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012005267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oddone E, Horner R, Diers T. Understanding racial variation in the use of carotid endarterectomy: The role of aversion to surgery. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1998;90:25–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim S, Burant C, Siminoff L, Kwoh C. Do African American and white patients with chronic knee/hip pain differ with respect to their awareness of joint replacement and its benefits and risks? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000:240. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayanian J. The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341:1661–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz J. Patient preferences and health disparities. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:1506–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Advani A, Atkeson B, Brown C, Peterson B, Fish L, Johnson J, Gockerman J, Gautier M. Barriers to the participation of African-American patients with cancer in clinical trials: A pilot study. Cancer. 2003;97:1499–506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schilling R, Schinke S, Nichols E, Zayas L, Miller S, Orlandi M. Developing strategies for AIDS prevention research with black and Hispanic drug users. Public Health Reports. 1989;104:2–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horgan J. Affirmative action. AIDS researchers seek to enroll more minorities in clinical trials. Scientific American. 1989;261:34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gifford A, Cunningham W, Heslin K, Andersen R, Nakazono T, Lieu D, Shapiro M, Bozzette S. Participation in research and access to experimental treatment by HIV-infected patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:1373–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbie-Smith G, Tomas S, Williams M, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14:537–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]