Abstract

Aims

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) requires countries to implement tobacco dependence treatment programs. To provide treatment effectively, a country needs individuals trained to deliver these services. We report on the global status of programs that train individuals to provide tobacco dependence treatment.

Design

Cross-sectional web-based survey of tobacco treatment training programs in a stratified convenience sample of countries chosen to vary by WHO geographic region and World Bank income level.

Participants

Key informants in 48 countries; 70% of 69 countries who were sent surveys responded.

Measurements

Program prevalence, frequency, duration, and size; background of trainees; content (adherence to pre-defined core competencies); funding sources; challenges.

Findings

We identified 61 current tobacco treatment training programs in 37 (77%) of 48 countries responding to the survey. Three-quarters of them began in 2000 or after, and 40% began after 2003, when the FCTC was adopted. Programs estimated training 14,194 individuals in 2007. Training was offered to a variety of professionals and paraprofessionals, but most often to physicians and nurses. Median program duration was 16 hours, but programs' duration, intensity, and size varied widely. Most programs used evidence-based guidelines and reported adherence to core tobacco treatment competencies. Training programs were less frequent in low-income countries and in Africa. Securing funding was the major challenge for most programs; current funding sources were government (58%), non-government organizations (23%), pharmaceutical companies (17%) and, in one case, the tobacco industry.

Conclusion

Training programs for tobacco treatment providers are diverse and growing. Most upper- and middle-income countries have programs, and most programs appear to be evidence-based. However, funding is a major challenge. In particular, more programs are needed for non-physicians and for low-income countries.

Keywords: tobacco use cessation, training, world health

Introduction

Tobacco use is a major threat to global health. By 2030, tobacco use is projected to cause 8 million deaths annually, with 80% of them occurring in the developing world (1). Tobacco use prevention and cessation are both needed to combat this problem,. Increasing cessation rates among adult tobacco users has the potential to reduce tobacco-attributable mortality faster than prevention of tobacco initiation.(1) The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), an international treaty adopted in 2003, aims to reduce the health consequences of tobacco use through the worldwide implementation of evidence-based tobacco control actions (2). The provision of treatment for tobacco users is one of the key activities called for by the FCTC. Article 14 of the FCTC asks countries to “design and implement effective programs aimed at promoting the cessation of tobacco use,” and to “establish . . programmes for . . counseling. . and treating tobacco dependence.” (2). In addition, offering help to quit is also one of six actions recommended to counter the tobacco epidemic in the 2008 WHO's Global Tobacco Epidemic report (1).

In order to deliver tobacco dependence treatment, a country needs to have an adequate number of trained tobacco treatment providers. These individuals could be health care professionals, paraprofessionals, or community health workers. A few individual tobacco training programs have been described, but little systematic data exist about the extent of training programs worldwide, and there is virtually no information on tobacco treatment training programs in developing countries. As standards for FCTC implementation are prepared, it will be important to understand the current extent and impact of training programs worldwide, especially in countries that have ratified the FCTC, and to compare the content of these programs with accepted training program guidelines.

This project aimed to develop a methodology for obtaining this information and to conduct an initial survey in a stratified convenience sample of countries. Although funds did not permit us to survey all FCTC signatory countries, we sought to obtain information from a sample of countries that varied by geographic region and income level. In each of these countries, we sought to identify tobacco training programs; to describe their teaching methods, funding, and number of individuals trained; and to compare their curricula with evidence-based tobacco treatment standards of practice developed by the Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence (ATTUD) (3). We also sought to identify gaps in existing programs and common challenges to implementing training programs worldwide.

Methods

With the help of an advisory board of international tobacco control experts (see Acknowledgments), we developed a web-based survey and administered it to a stratified convenience sample of key informants in 69 countries that varied by economic level and geographic region.

Sample

To develop a sample of countries that varied by geographic region and economic development, we created an 18-cell matrix by crossing the six WHO regions (4) with the three World Bank income levels (5) (Table 1). There were no countries in two of the cells: high-income countries in the WHO African and Southeast Asia regions. To fill the 16 remaining cells, we identified 44 countries, chosen because they had responded to a 2007 global survey of tobacco treatment services and guidelines (6). We reasoned that key informants in these countries would likely be knowledgeable about training activities.

Table 1.

Countries in the Sample*

| WHO Region (# of countries) | World Bank Income Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High Income | Middle Income | Low Income | |

| African (n=46) | N/A | Mauritius, South Africa | Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania |

| Americas (n=35) | Canada, United States | Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela, Argentina, Panama, Peru, Ecuador | N/A |

| Eastern Mediterranean (n=21) | Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates | Egypt, Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Tunisia | Pakistan |

| European (n=53) | Austria, England, France, Germany, Netherlands, Scotland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Cyprus, Faroe Islands, Greece, Israel, Finland, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Belgium, Ireland | Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Armenia, Hungary, Russia | Kyrgyzstan |

| South-East Asia (n=11) | N/A | India, Thailand, Sri Lanka | Bangladesh, Nepal |

| Western Pacific (n=27) | Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore | Malaysia, Mongolia, Palau, China | Cambodia |

Countries in non-italicized font (n=44) were chosen because they had participated in a prior global survey of tobacco treatment systems and guidelines (6). Countries in italics (n=25) were selected from other sources, as described in the Methods section. Countries that provided information to this project are shown in boldface type. Countries not in boldface had no respondent to our survey.

N/A = not applicable. There are no high-income countries in the WHO African or Southeast Asian regions. Haiti is the only low-income in the Americas region and was excluded from the sample because we could not locate key informants.

This strategy filled 12 of 16 cells, but left four cells empty and others containing few countries. To fill these gaps, we added 25 countries in which we or our Advisory Board could locate key informants, using three criteria. First, we added populous countries that are economically and politically prominent in their region (e.g., China, South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, Thailand, and Venezuela). Second, to increase the minimal representation from the Eastern Mediterranean, we contacted participants in a WHO Eastern Mediterranean regional meeting on smoking cessation treatment held in Cyprus in April 2008 (personal communication, Gregory Connolly). Third, we used a list of contacts from countries that had participated in a recent 32-country study of secondhand smoke (7). We could not identify a key informant in the only country in the low-income Americas category (Haiti) and excluded it. In total, we sent surveys to key informants in 69 nations. (Table 1)

Survey Instrument

In collaboration with ATTUD and our advisory board, we developed a 37-item web-based survey. It was administered in English only due to funding constraints. The survey assessed the following constructs for each training program identified: year started, number of individuals trained annually and since inception, professional background of trainees and trainers (physicians, nurses, psychologists, pharmacists, dentists, social workers, community health workers, students, or other), program cost to trainees, program funding sources (government, non-government grant, professional organization, educational institution, pharmaceutical company, tobacco company, or other), program affiliation (professional schools, government, or tobacco industry), program content (number of contact hours, method of instruction [lecture, small group, observed skills practice, web-based], topics covered [e.g., brief interventions, extended behavioral counseling, motivational techniques, pharmacotherapy, tailoring for special populations, complementary methods]), end-of-program assessment method, certification offered to graduates, and current challenges faced by the program.

To make a general assessment of the quality of programs identified, we asked key informants whether the program they described included training in 11 core competencies for evidence-based tobacco treatment as defined in 2005 by an ATTUD expert panel (3). Subsequent surveys of external tobacco treatment specialists in 2005 found high levels of concordance with these competencies (3). Because our survey respondents might not be fluent in English, we modified the 11 core competencies into simpler English language terms and expanded to 13 questions. One author (KW), an ATTUD board member, verified that the new wording accurately conveyed the original intent and meaning of the competencies.

Data Collection

The survey was administered using Survey Monkey, an online survey tool (www.surveymonkey.com). In February 2008, we sent an initial email message to each of our contacts in the selected countries asking whether these individuals could serve as key informants for a survey about tobacco treatment training in their countries, and if not, whether they could refer us to the most appropriate person in their country with this information. Two follow-up e-mails were sent to non-respondents. In March and April 2008, each key informant identified was sent an email requesting completion of a web-based survey. At the end of the survey, respondents were asked to provide us with contacts for any other training programs in their country. We sent a survey to all additional contacts identified; thus some countries had more than one survey response. Responses from countries with multiple surveys were reviewed and responses were not discordant. Non-respondents received two reminder emails. Data collection ended on June 30, 2008. Respondents received no financial incentives for survey completion. Information on U.S. programs was obtained from ATTUD's website, which had collected data on U.S. training programs using a comparable survey (8). We contacted these programs by email to obtain additional data to complete our survey.

Data Analysis

Completed surveys were transferred to an electronic database. Data analysis was conducted using Stata statistical software (9). Program characteristics were summarized and compared in univariate analyses by WHO region and by World Bank income level (high, medium, or low). Analyses were done for all programs identified and for all current programs, defined as programs that trained any individuals in 2007 or 2008.

Results

We received 76 reports from 48 (70%) of the 69 countries surveyed. This included 69 completed program surveys and reports from 7 additional informants that they were not aware of any training program in their country. Table 2 displays the distribution of respondents by WHO region and World Bank income level.

Table 2.

Response Rate and Program Prevalence by Country, Region and Income Level

| Countries sent surveys N | Countries responding N | Response rate % | Countries with a current program N (% of countries responding to survey) | Current Programs identified N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 69 | 48 | 70% | 37 (77%) | 61 |

| WHO Region | |||||

| African | 6 | 5 | 83% | 1 (20%) | 1 |

| Americas | 11 | 7 | 64% | 7 (100%) | 18 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 9 | 5 | 56% | 4 (80%) | 4 |

| European | 29 | 20 | 69% | 17 (89%) | 23 |

| South-East Asia | 5 | 3 | 60% | 2 (67%) | 7 |

| Western Pacific | 9 | 8 | 89% | 6 (75%) | 8 |

| World Bank Income Level | |||||

| High | 28 | 22 | 79% | 20 (91%) | 33 |

| Middle | 32 | 20 | 63% | 16 (80%) | 27 |

| Low | 9 | 6 | 67% | 1 (17%) | 1 |

Prevalence of Training Programs

In total, 41 of 48 countries (85%) reported that their country had a current or a previous tobacco treatment training program, and a total of 69 current or past training programs were identified. Thirty-seven of 48 countries (77%) reported that their country had a current tobacco treatment training program, and 61 current programs were identified. In four additional countries, previous programs were identified that did not conduct trainings in 2007–08.

The prevalence of tobacco training programs by country varied by country income level and region, with fewer programs in low-income countries and in Africa (Table 2). Current training programs were reported by respondents in only one of six low-income countries (17%, 95% CI: 0–50%), compared with 16 of 20 middle income countries (80%, 95% CI: 62–98%), and 20 of 22 high-income countries (91%, 95% CI: 86–100%). Nearly half of the countries with current training programs (46%, 95% CI: 29–63%) were in Europe, followed by the American (19%, 95% CI: 6–32%) and Western Pacific regions (16%, 95% CI: 4–29%), while only 3% (95% CI: 0–8%) of programs were in Africa and only 5% (95% CI: 0–13%) were in Southeast Asia.

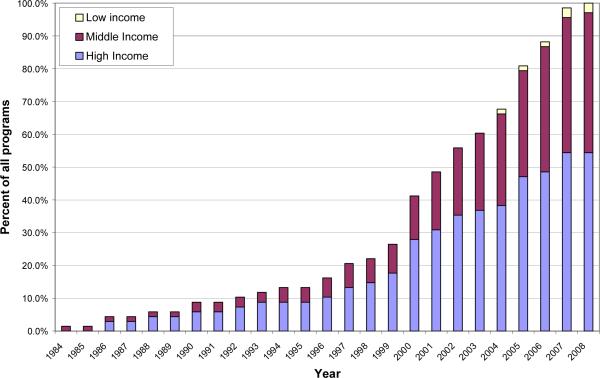

Although training programs had started as early as 1984 in high- and middle-income countries, nearly three-quarters (74%) of training programs, including all those in low-income countries, had begun in 2000 or after (Figure 1). Training programs in Europe and the Americas began in the 1980s, while programs in the Western Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean regions began in the 1990s, and programs in Southeast Asia and Africa began only after 2000. Forty percent of training programs began after 2003, when the FCTC treaty was adopted.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Incidence of Training Programs by Year, Stratified by Country Income Level

Individuals trained

Programs estimated a total of 12,161 individuals trained in 2006, and 14,194 individuals in 2007. Table 3 displays the individuals trained in programs in 2007 by geographic region and country income level. Only 1% of trainees were in low-income countries. The Americas trained the largest number of individuals, followed by the European and Western Pacific regions; few individuals were trained in the Eastern Mediterranean and African regions.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Training Programs by Geographic Region and Country Income Level*

| Number of Programs (Number of countries) | Year 1st Program Started | Number Trained In 2007 | Types of Individuals Trained N (%) of Programs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians** | Nurses** | Dentists** | Pharmacists** | Psychologists | Social workers | Community health workers | Program open to anyone | ||||

| All countries | 69 (41 countries) | 1984 | 14,194 (100%) | 62 (90%) | 55 (80%) | 40 (58%) | 37 (54%) | 41 (59%) | 31 (45%) | 39 (57%) | 11 (16%) |

| Region | |||||||||||

| African | 2 (2 countries) | 2007 | 72 (<1%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Americas | 19 (7 countries) | 1984 | 5,374 (38%) | 18 (95%) | 17 (89%) | 12 (63%) | 9 (47%) | 14 (74%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (53%) | 3 (17%) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 4 (4 countries) | 1997 | 98 (<1%) | 4 (100%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) |

| European | 26 (20 countries) | 1986 | 3,759 (26%) | 23 (88%) | 17 (65%) | 15 (58%) | 13 (50%) | 15 (58%) | 9 (35%) | 11 (42%) | 3 (12%) |

| South-East Asia | 7 (2 countries) | 2001 | 1,760 (12%) | 4 (57%) | 6 (86%) | 3 (43%) | 3 (43%) | 3 (43%) | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) |

| Western Pacific | 11 (6 countries) | 1992 | 3,131 (22%) | 11 (100%) | 10 (91%) | 8 (73%) | 9 (82%) | 6 (55%) | 7 (64%) | 11 (100%) | 2 (18%) |

| Income Level | |||||||||||

| High | 37 (20 countries) | 1986 | 7,351 (52%) | 33 (89%) | 33 (89%) | 25 (68%) | 27 (73%) | 26 (70%) | 21 (57%) | 22 (59%) | 7 (19%) |

| Middle | 29 (16 countries) | 1984 | 6771 (48%) | 26 (90%) | 19 (66%) | 14 (48%) | 9 (31%) | 14 (48%) | 10 (34%) | 15 (52%) | 4 (14%) |

| Low | 3 (1 country) | 2004 | 72 (<1%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (67%) | 0 (0%) |

Individual programs could offer training to multiple types of individuals. Includes all training programs identified including those that did not train students in 2007 or 2008.

Includes students of medicine, nursing, dentistry, or pharmacy

Programs trained individuals with a variety of professional backgrounds (Table 3). Nearly all programs (90%) offered training to physicians or medical students, and four-fifths of programs (80%) trained nurses or nursing students. Over half were open to psychologists, dentists, pharmacists, and community health workers. In addition to the categories shown in Table 3, programs also trained respiratory therapists, dieticians, mental health workers, addiction workers, social assistants, and community leaders such as religious leaders and teachers. Sixteen percent of programs were open to anyone. Training open to community health workers (CHWs) varied by region but not by income level, with CHWs included in all programs in Africa and the Western Pacific, but in fewer programs in other regions.

Training Program Content and Methods

The median duration of a training program was 16 hours, with a range from 1.5 hours to over 100 hours (interquartile range, 11–30 hours). Programs reported that they trained a median of 30 individuals per program (interquartile range, 15–60) and offered a median of 3 programs per year (interquartile range, 1.5–4.5 programs).

Programs used a variety of teaching methods, primarily lectures (98% of programs), small group sessions (94%), and observed practice with clients (70%). Fewer programs used one-on-one teaching (48%) or on-line training (25%). Training materials included a formal syllabus (40% of programs), training manual (74%), book (42%), and websites (26%).

Individuals with a variety of professional credentials taught in these programs. The trainers were most often physicians (in 77% of programs), followed by psychologists (53%), tobacco treatment counselors (53%), nurses (32%), CHWs (21%), pharmacists (18%) and dentists (10%).

Just over half of programs (52%) had an end-of-program examination. Although 74% of programs offered certification to graduates, only 5 programs (8%) used an external board to assess competence for certification. In most other cases, certification was offered by the sponsoring institution or training program and may have just represented proof of program attendance.

Adherence to Tobacco Treatment Competencies

Fifty-two programs (79%) reported that their training curriculum was based on evidence-based treatment guidelines. Programs most often used their country's own guidelines, which were themselves often adapted from other national guidelines. The U.S. clinical practice guideline (10) and to a lesser extent the British guideline (11) were most often mentioned as sources.

Table 4 displays the proportion of programs that reported adherence to each of the 13 ATTUD-derived core tobacco treatment competencies. Most of the competencies were covered in most of the training programs. Twenty-three percent of programs reported that they adhered to all 13 core competencies. The median number of competencies covered by a training program was 11 (range, 2–13). Over 90% of programs taught about tobacco use, health risks, counseling skills, pharmacotherapy, relapse prevention, and how to assess a smoker. A smaller majority of programs reported that they provided training on how to help diverse smokers, defined by medical illness or ethnic or socioeconomic status, how to make referrals, how to continue their own education, and compliance with a code of ethics. Few of the competencies varied notably by income level or geographic region, except that programs in the Eastern Mediterranean region reported adherence to a median of 7 core competencies, while the median in all other regions was ≥10.

Table 4.

Programs' Adherence to Core Competencies for Tobacco Treatment*

| ATTUD Category | Global Tobacco Treatment Training Survey question Does your program teach students… | Programs adhering to competency n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco dependence knowledge and education | about tobacco use and its health impact on the population? | 63/65 (97%) |

| about the evidence-based methods to stop tobacco use? | 58/64 (91%) | |

| Counseling skills | counseling strategies to help smokers commit to change? | 60/65 (92%) |

| Pharmacotherapy | about the medicines used to treat tobacco use? | 63/65 (97%) |

| Relapse prevention | how to provide continued support and help smokers avoid relapse? | 60/65 (92%) |

| Assessment interview | how to interview a smoker to collect the information needed for treatment? | 61/65 (94%) |

| Treatment planning | how to develop a treatment plan for each smoker? | 57/64 (89%) |

| Documentation and evaluation | how to keep records of smokers treated and measure program results? | 46/64 (72%) |

| Diversity and specific health issues | how to work with different population groups defined by age, sex, ethnicity or socioeconomic status? | 41/65 (63%) |

| how to work with smokers who have specific health needs (such as pregnancy)? | 46/64 (72%) | |

| Professional resources | how to provide referrals for smokers with medical and psychiatric problems? | 44/64 (69%) |

| Professional development | how to continue their own education about tobacco after the course ends? | 44/65 (68%) |

| Law and ethics | how to comply with a code of ethics and with other government regulations about treating smokers? | 35/62 (56%) |

| All competencies | -- | 15/66 (23%) |

| Median (range) of core competencies per program | 11 (2–13) | |

Adapted from Core competencies for evidence-based treatment of tobacco dependence.

Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence (ATTUD), April 2005. http://www.attud.org/docs/standards.pdf

Program funding and sponsorship

Training programs were funded by a variety of sources, and some were funded by more than one source. Among 66 programs reporting on their funding sources, 58% were funded by government grants or funds. Other sources of funding included grants from non-government organizations (23%), professional organizations (12%), educational institutions (14%), and the pharmaceutical industry (17%). (Table 5) Only one program, in Iran, had funding from the tobacco industry. Funding source did not vary by region or country income level. A total of 51 programs provided data on their sponsorship and affiliations. Training programs were most often affiliated with a medical school (61%), followed by a nursing school (20%), public health school (16%), pharmacy school (12%). One program in Europe reported a tobacco industry affiliation consisting of a lecture on cigarette technology given by a tobacco company employee.

Table 5.

Characteristics of Training Programs by Sources of Program Funding

| Programs providing data (N) | Sources of program funding | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government grants | Nongovernment grants | Professional organizations | University or school | Pharmaceutica 1 industry | Tobacco Industry | ||

| All countries | 66 | 38 (58%) | 15 (23%) | 8 (12%) | 9 (14%) | 11 (17%) | 1 (2%) |

| WHO Region | |||||||

| African | 2 | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Americas | 18 | 13 (72%) | 3 (17%) | 3 (17%) | 2 (11%) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 3 | 2 (67%) | 2 (67%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) |

| European | 25 | 11 (44%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (12%) | 6 (24%) | 7 (28%) | 0 (0%) |

| South-East Asia | 7 | 3 (43%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Western Pacific | 11 | 7 (64%) | 5 (45%) | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| Income Level | |||||||

| High | 35 | 23 (66%) | 5 (14%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Middle | 28 | 12 (43%) | 10 (36%) | 5 (18%) | 5 (18%) | 8 (29%) | 1 (4%) |

| Low | 3 | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Fifty-three percent of the 58 programs that reported on their cost were offered free to participants, including all programs in low-income countries, two-thirds of programs in middle-income countries, and less than half (41%) of those in high-income countries. Free programs were not more likely to be government or pharmaceutical industry-supported.

Fifty-nine programs answered questions about barriers that they faced. The biggest challenge, reported by 58% of programs, was securing funding. Less often cited as major challenges were finding individuals to train (24%), or obtaining training material (19%).

Discussion

The GT3 survey is one of the first surveys to describe tobacco treatment training programs worldwide. We found a rapid spread of training programs since 1999. By 2008, programs were reported in most high- and middle-income countries, but in few low-income countries. These programs were offered primarily to physicians and nurses and varied widely in intensity and duration. However, most programs reported adherence to evidence-based guidelines and a set of training program competencies.

Over the next 20 years, developing countries will account for upwards of 80% of tobacco-related deaths, yet tobacco treatment services are available to less than 5% of the world's population (1). Of the 1.3 billion current smokers worldwide, more than 500 million will die of tobacco-related disease if smoking cessation rates do not increase (12). A recent global survey of tobacco treatment efforts found the current state of treatment worldwide to be lacking (6). Fewer than half of countries surveyed had standardized treatment policies or government officials responsible for implementation efforts, and fewer than a quarter reported that treatment services were easily available (6). In this context, the FCTC offers an opportunity for promoting better tobacco treatment services through effective implementation of Article 14.

A key step in providing better tobacco treatment services will be the rapid expansion of tobacco treatment training programs. Prior to the GT3 survey, little was known about the current state of tobacco treatment training programs outside of North America and Europe. Most of what was known came from literature about the training of health professional students. The Global Health Professions pilot survey of medical, dental, nursing, and pharmacy student in 10 countries found that only 5–37% of third-year students reported receiving any formal training in tobacco treatment counseling, even though upwards of 90% of students thought that this should be a part of their curriculum (13). A survey of 282 nursing schools across 4 countries in Asia found that 51% of schools included tobacco treatment training, but most provided less than one hour of instruction on tobacco control per year and only 6% included in-depth training (14).

In the context of current FCTC efforts and previous research, several findings of the GT3 survey should be highlighted. There is a strong relationship between country income level and the presence of a training program, with high-income countries much more likely to have a treatment program than low-income countries. While this may be due to funding constraints across countries, the rapid spread of tobacco use and tobacco-related disease across middle- and low-income countries in the developing world makes it incumbent upon governments to fund tobacco treatment training efforts. Tobacco dependence treatment has been shown to be a cost-effective health intervention, even in low-income countries (15), yet funding was the most pressing challenge cited by training programs. Therefore, it is appropriate for those countries interested in confronting their tobacco epidemics to include tobacco treatment training as a component of their FCTC implementation package.

Our study also found that most tobacco treatment training programs are geared toward, and provided by, doctors and nurses. Expansion of these programs is still needed worldwide, especially in many European and East Asian countries where upwards of 25%–45% of physicians smoke (16). Training programs in these areas need to include content that assists physicians themselves to quit. Fewer programs are geared toward non-professional or paraprofessional health workers. Expanded training options for these non-physicians are needed urgently, especially in low-income countries with few physicians and nurses, where other individuals will be providing much of the tobacco treatment. The GT3 survey found some encouraging indications of this starting to happen. The African and Western Pacific regions are already more likely than other regions to include community health workers in their training programs, and some existing training programs aim to extend beyond health workers to include local community leaders such as teachers and religious leaders. Future training programs could benefit from association with government health systems at the primary care and community level to increase participation rates by non-physicians and non-nurses.

This paper has several limitations. First, this is not a representative sample of countries across the world. Although we used a stratified convenience sampling strategy and attempted to include countries with geographical and economic diversity, our study population did not include a random sample of countries and under-represented low-income countries. This limits the generalizability of our findings. Since we drew our sample from a set of countries that were early adopters of FCTC and had already responded to a survey about tobacco treatment, there may be a bias toward a higher prevalence of programs than would be found in a more representative sample. Second, our sample size was small, with fewer than 10 programs surveyed in the low-income group and in four of six geographic regions. Third, our results depend on the self-report of individuals who completed the survey. Not all were treatment specialists, and they may have been unaware of all training activities in their countries, leading to possible under-reporting. We also have no way to verify the accuracy of respondents' reports of high adherence to tobacco training standards. Fourth, due to funding constraints, the survey was conducted only in English, and we may have missed programs whose leaders lacked English language skills. Fifth, we focused on independent tobacco treatment training programs, not training for telephone quitline staff members or training that is integrated into existing educational structures such as medical or nursing education. The latter information is being collected by the Global Health Professionals Survey (13).

In summary, in order to achieve the goals set out by FCTC article 14, more tobacco treatment training programs are needed worldwide, especially culturally appropriate programs that are and tailored to low-resource settings for those in low-income countries. Programs for non-physicians are also needed. Given that most training programs are newly established and cite funding as a major challenge, it will be important to monitor the expansion and quality of these programs. As the implementation of Article 14 proceeds, the GT3 survey is a tool that could be used to monitor the quantity and quality of tobacco treatment training programs worldwide. We have identified and pilot-tested a methodology for surveillance.

Future work can build upon our initial pilot survey findings in a number of ways: the survey instrument should be translated into other languages; training program materials should be reviewed in order to validate self-report of ATTUD competencies met; most importantly, future evaluations should include a more representative set of countries, especially middle- and low-income countries that were not early FCTC adopters. In addition to using key informants, information on programs could also be also requested from government health ministries or health professional schools. In-depth reviews of these programs could help define effective ways to implement training in countries with low resources or specific tobacco control needs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our External Advisory Board (Gregory Connolly, Thomas Glynn, and Harry Lando) for their guidance, to all of the individuals around the world who took the time to respond to our survey, and to Susan Regan, PhD, for assistance with the data analysis.

Funding: Grant from Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence (ATTUD) with funds provided by the Global Treatment Partnership. Dr. Rigotti's time was funded by a grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (#K24-HL04440).

Footnotes

Declarations of interest N Rigotti has in the past five years received research grants to her institution from Nabi Biopharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis to test tobacco pharmacotherapies, and has received consulting fees from Pfizer and Sanofi-Aventis. A Bitton, A Richards, and M Reyen have no competing interests to declare. M Raw has in the last five years received freelance fees, funding for conference expenses and an honorarium for a talk from Pfizer. Ken Wassum is employed by Free and Clear, Inc, a U.S. for-profit provider of tobacco dependence treatment.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence (ATTUD) Core competencies for evidence-based treatment of tobacco dependence. 2005 April; http://www.attud.org/docs/standards.pdf (Accessed August 1st, 2008)

- 4.World Health Organization WHO member states, by region. http://www.who.int/countryfocus/country_offices/memberstatesbyregion/en/print.html. Accessed 8/19/08.

- 5.World Bank Country classification of economies. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/CLASS.XLS. (Accessed August 1st, 2008)

- 6.Raw M, Regan S, Rigotti NA, McNeil A. A survey of tobacco dependence treatment in 36 countries. (manuscript under review at Addiction) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Hyland A, Travers MJ, Dresler C, Higbee C, Cummings KM. A 32-country comparison of tobacco smoke derived particle levels in indoor public places. Tob Control. 2008;17:159–165. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence Find a TTS program. ( http://www.attud.org/findprog.php). Accessed 9-30-08.

- 9.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software. Release 9 Stata Corporation; College Station, TX: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Quick Reference Guide for Clinicians. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: Oct, 2000. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- 11.West R, McNeill A, Raw M. Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals: an update. Thorax. 2000;55:987–99. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Bank . Curbing the epidemic: Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.GTSS Collaborative Group Tobacco use and cessation counseling: Global Health Professionals Survey Pilot Study, 10 countries, 2005. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Supplement 2):ii31–ii34. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.015701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarna L, Danao LL, Chan SS, Shin SR, Baldago LA, Endo E, Minegishi H, Wewers ME. Tobacco control curricula content in baccalaureate nursing programs in four Asian nations. Nurs Outlook. 2006 Nov-Dec;54(6):334–44. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabhat Jha, Chaloupka Frank J., Moore James, Gajalakshmi Vendhan, Gupta Prakash C., Peck Richard, Asma Samira, Zatonski Witold. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. Tobacco Addiction; pp. 869–886. DOI: 10.1596/978-0-821-36179-5/Chpt-46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith DR, Leggat PA. BMC Public Health. Vol. 7. 2007. An international review of tobacco smoking in the medical profession: 1974-2004; p. 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]