Abstract

During adhesion-mediated neuronal growth cone guidance microtubules undergo major rearrangements. However, it is unknown whether microtubules extend to adhesion sites because of changes in plus-end polymerization and/or translocation dynamics, because of changes in actin-microtubule interactions, or because they follow the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Here, we used fluorescent speckle microscopy to directly quantify microtubule and actin dynamics in Aplysia growth cones as they turn towards beads coated with the cell adhesion molecule apCAM. During the initial phase of adhesion formation, dynamic microtubules in the peripheral domain preferentially explore apCAM-beads prior to changes in growth cone morphology and retrograde actin flow. Interestingly, these early microtubules have unchanged polymerization rates but spend less time in retrograde translocation due to uncoupling from actin flow. Furthermore, microtubules exploring the adhesion site spend less time in depolymerization. During the later phase of traction force generation, the central domain advances and more microtubules in the peripheral domain extend because of attenuation of actin flow and clearance of F-actin structures. Microtubules in the transition zone and central domain, however, translocate towards the adhesion site in concert with actin arcs and bundles, respectively. We conclude that adhesion molecules guide neuronal growth cones and underlying microtubule rearrangements largely by differentially regulating microtubule-actin coupling and actin movements according to growth cone region and not by controlling plus-end polymerization rates.

Keywords: microtubule dynamics, actin dynamics, growth cone guidance, cell adhesion, fluorescent speckle microscopy

Introduction

Neuronal growth cones are highly specialized signaling devices at the tip of axons, integrating extracellular guidance information and transducing it into directional movement towards target cells. The two major cytoskeletal components that drive this directional locomotion are microtubules and actin filaments (Dent and Gertler, 2003; Gordon-Weeks, 2004; Kalil and Dent, 2005). It is well established that the actin cytoskeleton is critical for growth cone motility while microtubules are essential for axonal elongation (Yamada et al., 1970; Letourneau and Ressler, 1984; Marsh and Letourneau, 1984). In addition, both microtubule and actin dynamics are required for growth cone guidance (Bentley and Toroian-Raymond, 1986; Sabry et al., 1991; Chien et al., 1993; Tanaka and Kirschner, 1995; Williamson et al., 1996; Challacombe et al., 1997; Buck and Zheng, 2002; Suter et al., 2004). Growth cone steering in vivo and in vitro involves major rearrangements of both microtubules and actin filaments (Sabry et al., 1991; Lin and Forscher, 1993; O'Connor and Bentley, 1993; Tanaka and Kirschner, 1995; Tanaka and Sabry, 1995; Suter et al., 1998; Dent and Gertler, 2003; Zhou and Cohan, 2004).

Dynamic microtubules explore the growth cone peripheral (P) domain where they interact with F-actin bundles (Tanaka and Kirschner, 1991; Dent and Kalil, 2001; Schaefer et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2002; Suter et al., 2004). The steady state distribution of these dynamic microtubules is largely determined by plus-end polymerization and retrograde translocation. Although not required for microtubule exploration of the P domain, filopodial actin bundles guide the polymerization of microtubules while removing them at the same time from the periphery by coupling to retrograde actin flow (Schaefer et al., 2002; Burnette et al., 2007). Furthermore, actin-microtubule interactions are critical for growth cone guidance and directed axonal outgrowth (Challacombe et al., 1996; Dent and Kalil, 2001; Buck and Zheng, 2002; Schaefer et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2002; Gordon-Weeks, 2004; Suter et al., 2004; Zhou and Cohan, 2004). Despite this wealth of information on the role of the growth cone cytoskeleton, surprisingly little is known about which aspects of actin and microtubule polymerization and translocation dynamics are affected during growth cone turning induced by specific guidance cues. The Aplysia cell adhesion molecule (apCAM) mediates growth cone steering involving leading edge protrusion and central (C) domain advance accompanied by attenuation of retrograde F-actin flow, traction force generation and microtubule extension to adhesion sites (Suter et al., 1998). These findings provided evidence for a mechanism of substrate-cytoskeletal coupling controlling not only growth cone movements (Mitchison and Kirschner, 1988; Jay, 2000; Suter and Forscher, 2000) but cell migration in general (Lauffenburger and Horwitz, 1996; Jurado et al., 2005; Gupton and Waterman-Storer, 2006; Giannone et al., 2007). In addition, two molecular motors, myosin II and dynein, have recently been implicated in laminin-mediated growth cone guidance and remodeling (Turney and Bridgman, 2005; Myers et al., 2006; Grabham et al., 2007). However, it is unclear whether microtubule polymerization or translocation dynamics actually change during adhesion-mediated growth cone turning, whether microtubule-actin interactions are altered or whether microtubules simply follow the actin reorganization.

To address these basic questions we combined microtubule/actin fluorescent speckle microscopy (FSM) (Waterman-Storer et al., 1998) with the restrained bead interaction (RBI) assay, which utilizes apCAM-coated beads to induce adhesion-mediated growth cone steering (Suter et al., 1998). The combination of these two techniques enabled us to directly quantify both actin and microtubule dynamics during apCAM-mediated adhesion formation and traction force generation. Our results show that microtubules explore the adhesion site before morphological changes occur and that these early microtubules extend due to uncoupling from retrograde actin flow and not due to changes in plus-end polymerization dynamics. During the second phase of growth cone guidance when traction force builds up, the bulk of microtubules reorient largely due to changes of the actin organization.

Methods

Aplysia Bag Cell Neuronal Culture

Aplysia bag cell neurons were dissected and cultured on poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips as previously described (Forscher and Smith, 1988; Suter et al., 1998). Cultured cells were kept in L15 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with artificial seawater (ASW) overnight in a 14° C incubator. All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Fluorescent Speckle Microscopy of Microtubule and F-Actin Dynamics

We performed multimode Differential Interference Contrast (DIC)/microtubule/actin fluorescent speckle microscopy as recently described (Waterman-Storer et al., 1998; Schaefer et al., 2002). 1 mg/ml rhodamine-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton, Inc) and 20 μM Alexa 488-phalloidin (Molecular Probes) were prepared in injection buffer (100 mM PIPES pH 7.0, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) and clarified at 10,000×g for 30 minutes at 4° C before microinjection into the cell bodies of 1 day old Aplysia bag cell neurons using an NP-2 micromanipulator and Femtojet microinjection system (Eppendorf). Cells were allowed to recover for at least 1 hour before L15-ASW was exchanged with imaging medium (ASW supplemented with 2 mg/ml BSA, 1 mg/ml L-carnosine and 25 mM vitamin E; all chemicals from Sigma-Aldrich or Calbiochem). Triple channel DIC/microtubule/actin timelapse sequences were taken at 10 seconds intervals using an Eclipse TE2000E (Nikon) microscope equipped with a 60× 1.4 NA oil objective and a EMCCD camera (Cascade II, Photometrics) controlled with MetaMorph 7.0 software (Molecular Devices). Fluorescent epi-illumination was provided by an X-cite 120 metal halide lamp (EXFO Photonic Solutions, Inc) and appropriate single band pass filter sets (Chroma).

Restrained Bead Interaction Assay

RBI assays were performed as previously reported (Suter et al., 1998; Suter et al., 2004). 5 μm-diameter Ni-NTA silica beads (Micromod) were coated with recombinant 6His-tagged apCAM purified from baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells (Suter et al., 2004). apCAM-coated beads were prepared as a 1:5000 dilution from 1% stocks in imaging medium. Cells were perfused with imaging medium throughout the experiment. We used a 3D-hydraulic micromanipulator (Narishige) to move individual beads with a microneedle onto the center quadrants Q2 or Q3 of the growth cone P domain and prevent them from retrograde movement. Because of the regional difference in microtubule distribution [Fig. 1], beads were consistently placed on the center quadrants in order to assess microtubule and actin dynamics. Triple channel time-lapse recording was performed before and immediately after bead placement until the C domain boundary reached the bead site, as determined by DIC imaging.

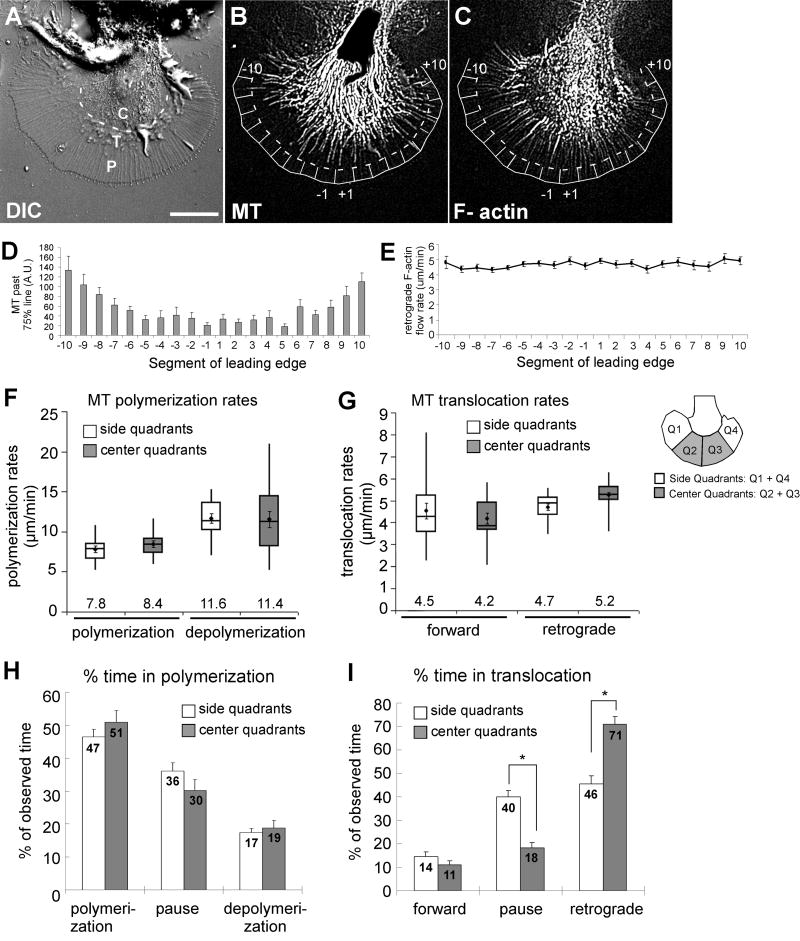

Fig. 1. Regional differences in microtubule translocation dynamics in steady state growth cones.

(A) DIC image of a live Aplysia growth cone including P domain, T zone and C domain. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Microtubules (MT) labeled by rhodamine-tubulin explore the P domain more in side than center segments. P domains were divided into 20 segments. Dashed line marks 75% of the distance from C domain boundary to the leading edge. (C) F-actin structures including filopodial bundles visualized with Alexa 488-phalloidin. (D) Quantification of microtubule exploration in distal segments: average values ± s.e.m. of the sum of binarized microtubule signal beyond the 75% line (n=16 growth cones). (E) Retrograde actin flow rate was similar in all segments (mean values ± s.e.m.; n=10). (F-I) Microtubule polymerization and translocation dynamics in side quadrants (n=36 microtubules) and center quadrants (n=34 microtubules). Data was averaged per growth cone and then mean values were determined from n=16 growth cones. (F) Whisker plots of microtubule polymerization and depolymerization rates. The top and lower ends of the boxes are the upper and lower quartiles; the middle line is the median value. Whiskers are minimum and maximum values. Means ± s.e.m. are dots with error bars; mean values (μm/minute) are above x-axis. Paired t-test (side versus center): P=0.15 (polymerization rate), P=0.45 (depolymerization rate). (G) Whisker plots of forward (P=0.24) and retrograde (P=0.01) translocation rates. (H) Percentage of time spent in polymerization, polymerization pauses, or depolymerization (Mean values ± s.e.m.; P > 0.05). (I) Percentage of time spent in forward, translocation pauses, or retrograde translocation. Asterisks indicate P<0.005.

Image processing and analysis of cytoskeletal dynamics

MetaMorph 7.0 software (Molecular Devices) was used for image processing, quantitative analysis of microtubule and actin dynamics and making of movies and montages. To enhance speckles, microtubule and actin images were processed with spatial filters in the following sequence: (1) Low pass 4 × 4; (2) Laplace 2 edge enhancement; (3) Low pass 3 × 3. For measuring microtubule density past 75% line, 10 minutes time-lapse stacks (60 images) were processed, binarized, and summed per segment. The C domain-bead axis was defined as the 5 μm wide corridor between the bead position and the C domain boundary. Using individual microtubule montages, polymerization and depolymerization rates were measured as the length change between the first speckle at the plus-end and an internal microtubule fiduciary mark over time, while translocation was defined by position changes of an internal speckle (Schaefer et al., 2002). For analysis of microtubule polymerization and translocation dynamics, we only selected clearly identifiable single microtubules in the P domain. Rates were determined on a time-weighted basis. Retrograde F-actin flow rates were assessed by kymograph analysis of actin speckles. One tailed paired t-tests were performed to identify significant changes in dynamics parameters between side vs. center, on- vs. off-axis, and pre-bead vs. latency microtubules. Photoshop CS3 (Adobe) and Canvas 8 (Deneba) were used for image processing and final figure assembly.

Results

Dynamic Microtubules Preferentially Explore the Growth Cone Periphery on the Side

Before analyzing microtubule dynamics during adhesion-mediated growth cone guidance, we first wondered whether there are regional differences in microtubule dynamics along the periphery in steady state Aplysia growth cones on poly-lysine substrates [Fig. 1]. Such information is critical for the proper analysis and interpretation of changes in microtubule behavior during growth cone responses to more specific adhesion substrates such as apCAM. In agreement with our previous study (Suter et al., 2004), we found that in steady state growth cones, dynamic microtubules explore the distal P domain 67% more frequently in the side than in the center segments [Fig. 1(B,D); Movie 1]. Since microtubules are often associated with retrogradely moving filopodial actin bundles in the P domain (Schaefer et al., 2002), a slower actin flow in the side sections would result in less “clearing” of microtubules from the growth cone periphery. However, here we did not measure any significant differences in actin flow rates along the growth cone periphery [Fig. 1(C,E); average actin flow rate 4.7±0.2 μm/minute] and therefore propose that the increased density of microtubules in distal side areas is not due to a similar decrease in retrograde F-actin flow rates.

Next, we analyzed microtubule plus-end polymerization and translocation dynamics in side versus center quadrants by FSM [Fig. 1(F-I)]. Polymerization rates were not significantly different between side (7.8±0.4 μm/minute) and center region microtubules (8.4±0.4 μm/minute), and similar observations were made for depolymerization rates [Fig. 1(F)]. In addition, forward (4.5±0.4/4.2±0.3 μm/minute) and retrograde (4.7±0.2/5.2±0.2 μm/minute) translocation rates did not differ between microtubules in side versus center regions versus, respectively [Fig. 1(G)]. Retrograde translocation rates of microtubules were similar to retrograde actin flow rates. This is suggestive of actin-microtubule coupling, which occurs 65% of time between microtubules and actin bundles in the growth cone periphery (Schaefer et al., 2002). Furthermore, the percentage of time microtubules spent in polymerization or depolymerization had no regional variations [Fig. 1(H)].

The only significant difference between side and center microtubules were the fractions of time spent in retrograde translocation and pauses [Fig. 1(I)]. Center microtubules spent 71±3% of the observed time in retrograde translocation compared to 46±3% for side microtubules. Conversely, center microtubules spent less time (18±2%) in translocation pauses than side microtubules (40±3%). Thus, dynamic exploratory microtubules were more abundant in distal side regions because they spent less time spent in retrograde translocation, most likely due to uncoupling from actin flow.

Microtubules Explore Adhesion Sites during the Latency Phase

Next we analyzed microtubule dynamics during adhesion-mediated growth cone steering. In the restrained bead interaction (RBI) assay, microbeads coated with ligands for the Aplysia cell adhesion molecule (apCAM) are positioned onto the distal P domain of growth cones to mimic cellular adhesive substrates (Suter et al., 1998). The retrograde movement of beads coupled via apCAM to the underlying actin flow is prevented by a microneedle, resulting in a stereotypic growth cone response towards the bead that can be subdivided into two major phases. (1) The “latency” phase begins with bead placement and involves adhesion formation and signaling but very little morphological changes. (2) The following “traction” phase (previously named “interaction” phase (Suter et al., 1998)) is characterized by major structural, cytoskeletal and biophysical changes. These changes include central domain extension towards the bead and protrusive growth of the leading edge in front of the bead. Actin flow is significantly attenuated along the C domain-bead axis and microtubules extend towards the adhesion site while tension builds up between the C domain and the bead substrate [Fig. 2(A-D); Movie 2] (Suter et al., 1998). These morphological and cytoskeletal rearrangements faithfully recapitulate the events occurring during growth cone encounters with favorable cellular substrates (Lin and Forscher, 1993) and correspond to the stages in axon formation (Goldberg and Burmeister, 1986; Dent and Gertler, 2003).

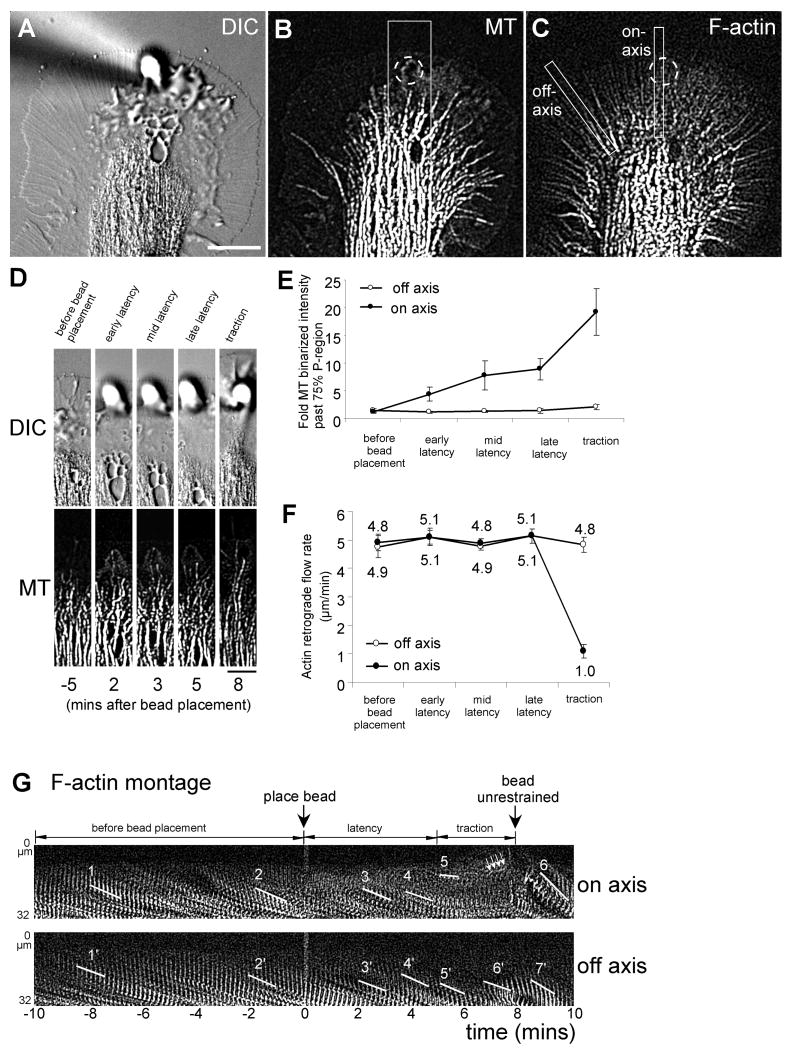

Fig. 2. Preferential microtubule exploration of apCAM sites during latency period.

(A) DIC image of growth cone directly after placement of apCAM-bead (time = 0 minute) restrained with a micropipette. (B) Microtubule FSM image of (A). Dashed circle represents bead position; box marks region used for time-lapse montage in (D). (C) Actin FSM image of (A). On-axis and off-axis boxes were used for time-lapse montage in (G). (D) DIC and microtubule time-lapse montages of on-axis corridor marked in (B) before bead placement, during latency and traction period. Individual microtubules explored the adhesion site during the latency period. (E) Microtubule intensity past the 75% boundary in the P domain increased on-axis (one bead diameter) during the latency period and remained constant off–axis (up to 2 bead diameters next to the bead; mean values ± s.e.m.; n=10 growth cones). (F) Retrograde actin flow rates remained similar in the latency period, but decreased significantly on-axis during the traction period (mean values ± s.e.m.; n=7 growth cones). Latency period was equally divided into early, mid and late latency. (G) Montages of F-actin bundles in on-axis and off-axis boxes indicated in (C). line 1: 5.1 μm/minute; line 2: 4.9 μm/minute; line 3: 5.1 μm/minute; line 4: 4.8 μm/minute; line 5: 1.6 μm/minute; line 6: 12.7 μm/minute; line 1′ to 7′: 4.9 - 6.1 μm/minute. Scale bars: 20 μm (A), 10 μm (D).

During the latency period we previously observed F-actin accumulation and Src activation around the bead adhesion site, both depend on dynamic microtubules (Suter et al., 2004). Since microtubules strengthen apCAM-actin coupling by Src activation, we speculated that dynamic microtubules could preferentially explore the adhesion site during the latency phase. Indeed, here we show by live cell imaging that microtubule density in the distal P domain along the C domain-bead axis (on-axis) but not in neighboring areas (off-axis) increased up to 9-fold throughout the latency period, whereas overall growth cone morphology remained stable [Fig. 2(D,E); Movie 3]. Thus, preferential microtubule extension to the adhesion site occurred clearly before the C domain (characterized by large organelles) moved towards the bead. Microtubule density then further doubled between the late latency and the traction period [Fig. 2(E)].

Since microtubule distribution in the P domain is affected by the actin cytoskeleton (Forscher and Smith, 1988; Burnette et al., 2007), we analyzed whether changes in F-actin dynamics or content could explain the preferential microtubule exploration of the apCAM adhesion site during the latency phase. Consistent with our measurements of F-actin flow rates using marker beads (Suter et al., 1998), actin FSM revealed that during the complete latency period retrograde F-actin flow along the C domain-bead axis (5.1±0.3 μm/minute in late latency) was not different from either the period before bead placement (4.9±0.3 μm/minute) or off-axis areas (5.1±0.3 μm/minute) [Fig. 2(F,G)]. In addition, we did not observe any decrease in F-actin content between the C domain boundary and the bead area during the latency period. During the traction phase however, we observed an 80% attenuation of retrograde flow as well as a decrease in F-actin content specifically along the C domain-bead axis (dark area below line 5 and white arrows in Figure 2(G)). Furthermore, montages of on-axis F-actin dynamics revealed brief periods of forward movements of actin structures at the end of the traction phase (arrows in Figure 2(G)). Upon bead release, flow rates were increased when compared to pre-bead control rates [Fig. 2(G), line 6: 12.7 μm/minute], indicating that the beads were under strong tension during the traction phase. In summary, microtubules along the C domain-bead axis preferentially explored apCAM adhesion sites during the early phase of apCAM-cytoskeletal coupling even though F-actin flow continued at similar rate.

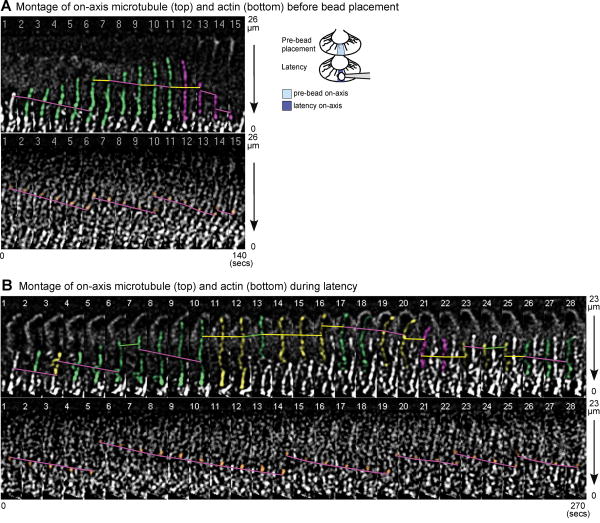

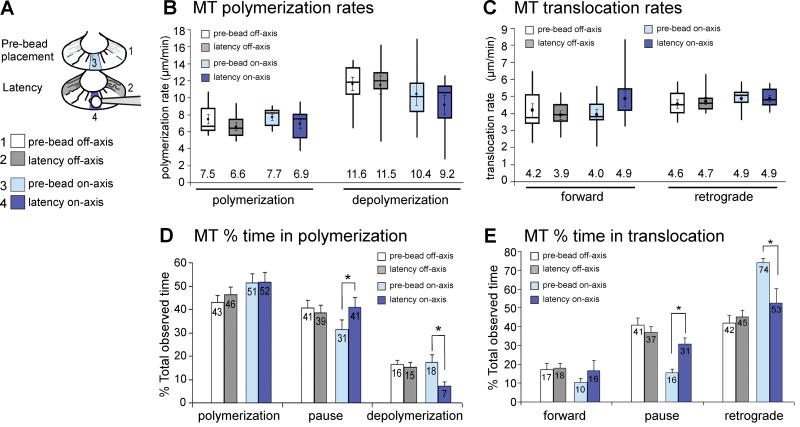

Exploratory Microtubules Spend less Time Coupled to Actin Flow and in Depolymerization

To determine the mechanisms by which microtubules explore the adhesion site during the latency period, we analyzed and compared plus-end polymerization and translocation dynamics of individual microtubules located on and off the C domain-bead axis before (“pre-bead”) and right after bead placement (“latency”) on the same growth cones. Before bead placement on-axis microtubules were often observed in polymerization phase while undergoing retrograde translocation [Fig. 3(A)]. During the latency phase, however, these on-axis microtubules spent less time in depolymerization and retrograde translocation [Fig. 3(B)]. Quantification of plus-end polymerization and translocation dynamics in 10 growth cones is presented in Figure 4. During the latency period, polymerization (6.9±0.6 μm/minute) and depolymerization rates (9.2±1.1 μm/minute) of on-axis microtubules did not differ significantly from control values measured in the same region before bead placement (7.7±0.4 and 10.4±1.3 μm/minute, respectively) or from off-axis control microtubules [Fig. 4(B)]. Retrograde and forward translocation rates of microtubules exploring the adhesion site during the latency also remained similar to pre-bead control values as well as to rates of off-axis microtubules before and after bead placement on the same growth cones [Fig. 4(C)].

Fig. 3. Microtubule and actin dynamics before and after bead placement.

Montages of individual microtubules (top) and actin bundles (bottom) in the on-axis region before bead placement (A) and during the latency phase (B). The growth cone leading edge is facing the top edge. For translocation analysis, an internal reference speckle was followed (green line: forward; yellow: translocation pause; magenta: retrograde). Internal actin speckles used for line tracing are shown in orange. Polymerization events were determined by the addition/disappearance of microtubule plus end speckles, and polymerization rates measured based on the distance between the tip and internal reference speckle per time interval. Microtubules are color-shaded based on polymerization event (green: polymerization; yellow: polymerization pause; magenta: depolymerization). Arrows indicate direction of retrograde flow. Time-lapse interval: 10 seconds. Vertical distance indicated on the right. (A) Example of an on-axis microtubule before bead placement undergoing plus-end polymerization and retrograde translocation (magenta lines) followed by depolymerization. (B) Example of an on-axis microtubule during the latency period spending more time in translocation pause (yellow lines).

Fig. 4. Quantification of microtubule polymerization and translocation dynamics during the latency period.

(A) Schematic of P domain areas from which microtubules were selected for analysis: Side quadrants before (pre-bead off-axis) and after bead placement (latency off-axis); C domain-bead axis before (pre-bead on-axis) and after bead placement (latency on-axis). Only clearly quantifiable microtubules were analyzed in 10 growth cones (42 microtubules on-axis, 33 microtubules off-axis). (B) Polymerization rates do not change during the latency period (paired t-test for pre-bead versus latency: P>0.05). Data are shown as whisker plots. (C) Forward and retrograde translocation rates as whisker plots (P>0.05). (D) During the latency phase, on-axis microtubules spent less time in depolymerization and conversely more time in pause when compared to on-axis microtubules before bead placement. (E) Exploratory on-axis microtubules spent less time in retrograde translocation and conversely more time in translocation pause during the latency period than prior to bead placement. Mean values ± s.e.m. are shown in (D) and (E); asterisks indicate P <0.05.

Notably, these exploratory microtubules spent significantly less time in retrograde translocation during the latency period when compared to pre-bead control microtubules (53±7.5% versus 74±2.1%), while spending more time in translocation pauses (31±3.2% versus 16±1.8%; Fig. 4(E)). In addition, these on-axis microtubules also spent less time in depolymerization during the latency period than before bead placement (7±1.2% versus 18±3.0%), but more time in polymerization pauses (41±4.0% versus 31±4.4%; Fig. 4(D)). Neither polymerization nor translocation dynamics of off-axis microtubules were affected during any phase of the apCAM-mediated growth cone guidance. Thus, microtubules preferentially explore apCAM adhesion sites during the latency phase through two mechanisms: (1) because they undergo less retrograde translocation due to partial uncoupling from actin flow and (2) because they spend less time in depolymerization.

Microtubule Extension during the Traction Phase in Response to F-actin Rearrangements

We next investigated the mechanism of bulk microtubule extension towards the adhesion site during the traction phase of apCAM-mediated growth cone guidance. We have previously shown that apCAM-actin coupling results in an acute reduction of retrograde actin flow at the onset of the traction phase (Suter et al., 1998; Suter and Forscher, 2001). Here, we confirmed these flow effects using actin FSM [Figs. 2(G) and 5(A) upper panel, orange and pink speckles]. During the traction phase, retrograde actin flow rates between the bead and the C domain were reduced by 80% compared to before bead placement (n=7). In addition, we observed a gradual clearance of actin bundles from the on-axis corridor during the traction period when compared to the latency or pre-bead period [Fig. 2(G), dark area below white arrows; Fig. 5(A)]. Finally, the transition (T) zone, in which actin bundles are severed and disassembled, moved forward during the traction period (indicated by red line in Fig. 5(A)). F-actin flow attenuation and bundle clearance in the P domain were accompanied by bulk extension of microtubules towards the bead [Fig. 5(A) lower panel, red microtubules], while exploratory microtubules from the latency phase persisted around the bead [Fig. 5(A), blue and green microtubules]. Observation of time-lapse movies indicated that the polymerization dynamics of these on-axis microtubules during the traction period did not significantly differ from the pre-bead or latency period, while most microtubules were either in translocation pauses or still in retrograde translocation, and very little forward translocation was observed (Movies 2 and 4; Fig. 5(A) lower panel).

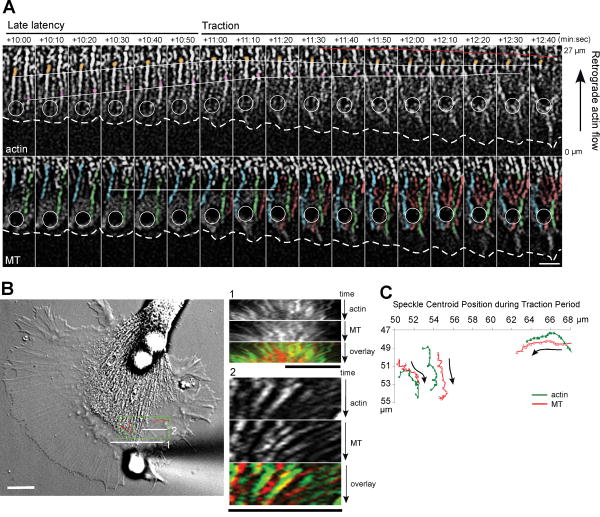

Fig. 5. Microtubules and F-actin rearrange in concert during the traction period.

(A) Time-lapse montage of actin (upper panel) and microtubule dynamics (lower panel) in the C domain-bead axis during the late latency and traction period. Dashed line: growth cone leading edge; circle: apCAM bead position. Actin speckles colored in pink and orange show that retrograde flow continued during late latency and abruptly stopped at the onset of traction phase. Red line: forward shift of the T zone. Blue and green microtubules explored the bead since the late latency period, while red microtubules extended to the bead during the traction period. White line: translocation pause of blue microtubule. Scale bar: 5 μm. (B) DIC image of a different growth cone when the C domain reached the bead. Line scans 1 and 2 through the T zone were used for actin and microtubule kymographs on the right (green: actin, red: microtubules; see also Movie 4). Green box demarks area used for tracking the speckle positions shown in (C). All scale bars: 10 μm. (C) Tracking of 3 pairs of adjacent actin and microtubule speckles from boxed area in (B) in the traction period. Arrows indicate direction of speckle movements.

In addition, microtubules in the T zone and C domain were re-oriented in concert with adjacent actin structures towards the apCAM-bead [Fig. 5(B); Movie 4]. These structures include the transverse actin arcs in the T zone as well as actin bundles in the C domain, both of which undergo Rho-dependent actomyosin-contractility (Schaefer et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2003). Arcs are oriented perpendicular to the filopodial actin bundles (Movie 4, orange and yellow arrowhead; Fig. 6), while central actin bundles are oriented parallel to the axis of growth (Movie 4, red and pink arrowhead) and appear to be formed from T zone arcs (Zhang et al., 2003). The kymographs in Figure 5(B) show concomitant movements of actin speckles on arcs and C domain bundles together with microtubule speckles towards the C domain and the apCAM-bead. These movements were confirmed by tracking centroid positions of adjacent actin and microtubule speckles [Fig. 5(C)]. During the traction period the decrease of P domain actin structures behind the bead resulted in reorientation of actin arcs towards the adhesion site where they appeared to be immobilized. Because they are under actomyosin-based tension, actin arcs narrowed the C domain and focused the microtubules towards the bead site (Movie 4). Bulk microtubules and actin bundles in the C domain both translocated forward towards the apCAM-bead at an average rate of 2.69 ± 0.05 μm/minute (n=6), which is similar to the rate of forward movement of the C domain boundary and leading edge (2.74 ± 0.56 μm/minute, n=14). In summary, during the traction period, P domain microtubules advanced towards the adhesion site because of actin flow attenuation and actin clearance, while T zone and C domain microtubules translocated forward most likely through association with arcs and central actin bundles, respectively.

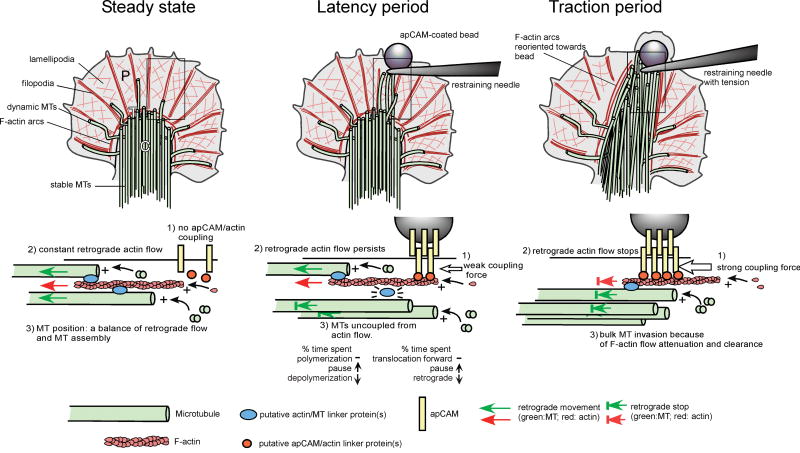

Fig. 6. Model: Mechanisms of microtubule extension during adhesion-mediated growth cone guidance.

Upper panel shows top view of growth cone in steady state, latency and traction period of adhesion-mediated growth cone guidance. Lower panel shows corresponding sections of the plasma membrane/cytoskeleton interface marked by the box in the top view. In steady state growth cones on poly-lysine, apCAM is not coupled to actin (1), which moves at constant retrograde flow (2). Microtubule tip positions are determined by a balance of plus-end polymerization and retrograde transport through actin flow coupling via putative linker protein(s) (blue) (3). During the latency period, apCAM-actin coupling forces are weak (1) and therefore do not result in flow attenuation (2). Putative signals derived from the adhesion site might uncouple microtubules from F-actin by changing the affinity of linker protein(s) to at least one of the cytoskeletal components (3), resulting in higher microtubule exploration of the adhesion site. Note that the additional possible mechanisms discussed such as increased microtubule stability and capture at adhesion site are not depicted in this schematic. During the traction period, strong apCAM-actin coupling (1) stops retrograde flow along the C domain-bead axis (2). Microtubules persisting at the bead since the latency phase are joined by new microtubules invading the corridor due to actin flow attenuation and F-actin clearance (3). T zone and C domain microtubules translocate towards the bead, potentially by coupling to arcs and central actin bundles.

Discussion

There is accumulating evidence that actin-microtubule interactions are critical for a number of cellular processes, including cell migration, growth cone pathfinding, cell division and cortical flow (Rodriguez et al., 2003). In neuronal growth cones, actin-microtubule interactions regulate microtubule distribution under steady state condition and are important for growth cone steering and directed axonal outgrowth (Challacombe et al., 1996; Dent and Kalil, 2001; Buck and Zheng, 2002; Schaefer et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2002; Gordon-Weeks, 2004; Suter et al., 2004; Zhou and Cohan, 2004). However, these previous studies have largely relied on immunocytochemical data and cytoskeletal drug treatments but not quantitative live cell imaging. Thus, it has remained unknown (1) whether microtubule polymerization or translocation dynamics change during growth cone steering, (2) whether actin-microtubule coupling changes or (3) whether microtubules simply follow actin rearrangements. A detailed knowledge of which aspect of cytoskeletal dynamics is affected in growth cone turning is essential in order to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms and guide the search for cytoskeletal effector proteins downstream of guidance receptors. To our knowledge the present study represents the first quantitative analysis of microtubules dynamics during adhesion-mediated cytoskeletal rearrangements involved in growth cone steering. Here, we have demonstrated by quantitative microtubule/actin FSM that microtubule extension in adhesion-mediated attractive growth cone guidance is largely regulated at the level of actin-microtubule coupling and less by controlling microtubule plus end polymerization dynamics. While our findings, as well as others, indicate that guidance cues primarily affect the actin cytoskeleton and actin-microtubule interactions (Dent and Gertler, 2003; Zhou and Cohan, 2004), certain cues such as NGF and slit may also signal directly to microtubule plus-end binding proteins such as APC and orbit/MAST/CLASP, respectively, and affect microtubule dynamics independently of the actin cytoskeleton (Lee et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2004).

Microtubule Dynamics in Steady State Growth Cones

Consistent with our previous report (Suter et al., 2004), we found that steady state growth cones on poly-lysine substrates have a higher density of exploratory microtubules in the side versus center regions [Fig. 1]. The present finding of constant actin flow rates along the growth cone periphery is in slight contrast with our previous study, where we reported a 15% decrease in actin flow in the side versus center regions (Suter et al., 2004). Because of the larger sample size in the present study, we believe that the current finding is more accurate. In addition, a relatively small decrease of 15% in actin flow could not solely explain the 67% increase in microtubule density on the side. Thus, other mechanisms must cause the region-specific microtubule exploration of the distal P domain. We found that microtubules in the side segments spend significantly less time in retrograde translocation than microtubules in the center segments. Since retrograde microtubule translocation is largely caused by coupling to retrogradely moving actin bundles (Schaefer et al., 2002), we conclude that microtubules on the growth cone sides have a lower level of actin coupling than center region microtubules. Such differences in actin coupling could be due to alterations in amounts or affinities of actin-microtubule linker proteins between side and center regions. Although putative linker molecules such as microtubule associated and motor proteins have been proposed, clearly more work is needed to establish the role of these candidate proteins in neuronal growth cones (Rodriguez et al., 2003).

What could be the functional significance of these regional differences in microtubule distribution? Since evidence suggests that microtubules have a signaling role in growth cone steering (Buck and Zheng, 2002; Suter et al., 2004), we speculate that the higher density of microtubules in the side regions could increase the sensing potential of the growth cone for guidance cues that are presented more “off-path” with respect to the direction of growth. At least in the case of the large Aplysia growth cone with a wide and not very dynamic P domain, the probability of adhesion receptor binding and activation on the side could be lower than in the center region while the growth cone is moving straight ahead in cell culture. Because of the Aplysia growth cone geometry, adhesion molecules presented in the path of growth cone movement will engage a higher number of receptors in the center part of the P domain when compared to adhesion molecules presented at similar densities on the side. The growth cone might compensate the lower probability of encountering molecular cues on the side with an increased microtubule density which in turn could increase the probability of turning responses. Whether such a mechanism plays a role for growth cone guidance in vivo, where growth cones tend to be smaller, more dynamic and exposed to multiple cues, is unknown.

Microtubule Dynamics during Adhesion-Mediated Growth Cone Guidance

Interestingly, we also found evidence that uncoupling from retrograde actin flow is a major cause for the gradual increase in microtubule density at adhesion sites during the latency period of apCAM-mediated growth cone guidance. This finding might be in contrast with our previous observations of low microtubule density at the bead based on tubulin immunocytochemistry of growth cones fixed during the latency period (Suter et al., 2004). Immunocytochemistry only provides a snapshot in time while microtubule FSM allows monitoring the behavior of microtubules during the complete sequence of apCAM-induced growth cone responses. Thus, immunocytochemistry likely underestimates actual microtubule dynamics. In addition, quantification of microtubule density was performed differently in the two studies: Previously, we determined the average number of microtubules at the bead site and did not directly compare these values with microtubule density at same location before bead placement or off-axis. Here, we determined microtubule density by summation of binarized microtubule intensities in more growth cones over 10 minutes and directly compared these values with microtubule densities before bead placement and off-axis. Thus, we believe that the present study describes the microtubule behavior during the latency period more accurately.

A refined substrate-cytoskeletal model (Mitchison and Kirschner, 1988; Jay, 2000; Suter and Forscher, 2000) explaining the underlying cytoskeletal changes involved in adhesion-mediated growth cone guidance is depicted in Figure 6. Similarly to our present findings, previous studies reported early microtubule rearrangements before growth cones turn away from a repelling substrate border (Tanaka and Kirschner, 1995; Williamson et al., 1996; Challacombe et al., 1997). We hypothesize that a signal originating from the adhesion site traveling retrogradely with actin flow may reduce the coupling state of putative actin-microtubule linker protein(s) such as MAP2, tau, or Short Stop (Rodriguez et al., 2003). Our data also support two other potential mechanisms leading to increased microtubule density at adhesion sites during the early phase of adhesion-mediated growth cone rearrangements. (1) One mechanism could involve stabilization by plus-end tracking proteins, since microtubules also spent less time in depolymerization during the latency period (Gordon-Weeks, 2004; Kalil and Dent, 2005; Koester et al., 2007). Conventionally, measures of microtubule stability are usually the classic parameters catastrophe and rescue frequencies, which are the frequencies of polymerization/depolymerization transition events (Walker et al., 1988). In this study we have not used these parameters to describe microtubule stability, because microtubules in the growth cone periphery frequently collapse into the crowded central domain, after which it is difficult to determine whether the same microtubules underwent rescue or not, resulting in an underestimate of rescue events (Tanaka and Kirschner, 1991). Instead we used the straightforward measurement of “percentage time spent” in a given polymerization behavior category, which is partially reflective of catastrophe and rescue frequencies. (2) The second alternative mechanism could be explained by the capture of microtubules at the adhesion site, as shown previously for non-neuronal cells (Kaverina et al., 1998; Gundersen, 2002), since we observed an increase in translocation pause of exploratory microtubules during the latency period.

What is the purpose of attracting early microtubules towards the newly formed adhesion site? Src-tyrosine kinase activation at the bead site is essential for strong apCAM-actin coupling and depends on microtubule dynamics (Suter and Forscher, 2001; Suter et al., 2004). Thus, a bidirectional signal might initiate cytoskeletal reorganization in apCAM-induced growth cone steering. Upon apCAM-clustering near the leading edge, signals could travel with retrograde actin flow to promote microtubule extension via partial actin-microtubule uncoupling and microtubule stabilization [Fig. 6]. These early microtubules could then deliver signaling molecules such as Src activators to strengthen apCAM-actin coupling. As a consequence, actin flow is attenuated and actin bundles disappear, allowing bulk microtubule extension to the adhesion site. Similar P domain invasion by microtubules occurred when such actin changes were induced globally either by application of the myosin II inhibitor blebbistatin or the actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin B (Forscher and Smith, 1988; Burnette et al., 2007).

The concerted movement of T zone and C domain microtubules and adjacent actin structures suggests that microtubules are translocated towards the adhesion site by coupling to reorienting actin arcs and central actin bundles, respectively. The T zone actin arcs and C domain actin bundles are likely the cytoskeletal structures that maintain the tension built up during adhesion-mediated neurite growth and guidance (Lamoureux et al., 1989; Suter et al., 1998). However, we can not precisely determine whether the coupling level between microtubules and F-actin changes during the phase of traction force generation because of the high density of these cytoskeletal structures in the C domain. Alternatively, the microtubule motor dynein could be involved, as proposed in laminin-stimulated growth cone turning and outgrowth (Myers et al., 2006; Grabham et al., 2007). Finally, we can not formally exclude the possibility that microtubule-microtubule interactions also contribute to microtubule reorientation in the T zone and C domain during the traction phase.

In summary, dynamic microtubules in the P domain of growth cones advance to apCAM adhesion sites earlier than previously anticipated. Interestingly, these microtubules do so by uncoupling from actin, while bulk microtubule extension later occurs due to actin rearrangements involved in growth cone guidance. Since actin-microtubule interactions play a role in cell migration in general (Waterman-Storer and Salmon, 1997; Salmon et al., 2002; Rodriguez et al., 2003), it will be interesting to investigate whether similar changes in actin-microtubule coupling occur when fibroblast-like cells migrate on different adhesion substrates. These mechanistic findings will facilitate the search for the regulatory molecules in charge such as actin-microtubule linker protein(s), which is an exciting goal for future studies.

Supplementary Material

Movie 1. Microtubules explore side more than center regions in steady state Aplysia growth cones. Growth cone periphery was divided into 20 segments (green: side segments; blue: center segments). Segments cover the distal P domain from the 75% line to the leading edge. Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 5 minutes; playback time: 60× real time (6 fps). Scale bar: 10 μm.

Movie 2. Triple channel (DIC, microtubule and actin FSM) time-lapse movie of growth cone response to apCAM-coated bead. Elapsed time 0-5 minutes: before bead placement; 14-28 minutes: latency period; 29-32 minutes: traction period; 32-33 minutes: bead release. Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 33 minutes; playback time: 60× real time (6 fps). Scale bar: 10 μm.

Movie 3. Dual channel (DIC, microtubule FSM) time-lapse movie showing early exploratory microtubules (colored in blue) extending towards apCAM-bead adhesion site during the latency period. Elapsed time -6:57-0:00 minutes:seconds: before bead placement; 0:00-5:27 minutes:seconds: latency period; 5:27-7:57 minutes:seconds: traction period. Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 15 minutes; playback time: 50× real time (5 fps). Scale bar: 5 μm.

Movie 4. Triple channel (DIC, microtubule and actin FSM) time-lapse movie of structural and cytoskeletal rearrangements during the traction phase. Movie shows concomitant movement of microtubules with actin arcs and bundles in the T zone and C domain, respectively, towards apCAM bead. Microtubules and actin reference speckles are traced in the T zone (orange and yellow arrowheads) and C domain (red and pink arrowheads). Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 5 minutes; playback time: 150× real time (15 fps). Scale bar: 10 μm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Gil Lee and Xiong Ying for assistance with development of additional growth cone turning assays not employed in the present study. We are grateful to Dr. Peter Hollenbeck, Dr. Donald Ready and Dr. Chris Staiger as well as members of the Suter Lab for valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Laurie Iten for help with compression of movie files. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 NS049233) and the Bindley Bioscience Center at Purdue University to D.M.S.

Abbreviations

- apCAM

Aplysia cell adhesion molecule

- ASW

artificial sea water

- C

central

- CNS

central nervous system

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- FSM

fluorescent speckle microscopy

- P

peripheral

- RBI

restrained bead interaction

- T

transition

Contributor Information

Aih Cheun Lee, Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, 915 West State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2054.

Daniel M. Suter, Bindley Bioscience Center, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907.

References

- Bentley D, Toroian-Raymond A. Disoriented pathfinding by pioneer neurone growth cones deprived of filopodia by cytochalasin treatment. Nature. 1986;323:712–715. doi: 10.1038/323712a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck KB, Zheng JQ. Growth cone turning induced by direct local modification of microtubule dynamics. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9358–9367. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09358.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette DT, Schaefer AW, Ji L, Danuser G, Forscher P. Filopodial actin bundles are not necessary for microtubule advance into the peripheral domain of Aplysia neuronal growth cones. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1360–1369. doi: 10.1038/ncb1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challacombe JF, Snow DM, Letourneau PC. Actin filament bundles are required for microtubule reorientation during growth cone turning to avoid an inhibitory guidance cue. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 8):2031–2040. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.8.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challacombe JF, Snow DM, Letourneau PC. Dynamic microtubule ends are required for growth cone turning to avoid an inhibitory guidance cue. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3085–3095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03085.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien CB, Rosenthal DE, Harris WA, Holt CE. Navigational errors made by growth cones without filopodia in the embryonic Xenopus brain. Neuron. 1993;11:237–251. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90181-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, Gertler FB. Cytoskeletal dynamics and transport in growth cone motility and axon guidance. Neuron. 2003;40:209–227. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, Kalil K. Axon branching requires interactions between dynamic microtubules and actin filaments. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9757–9769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09757.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forscher P, Smith SJ. Actions of cytochalasins on the organization of actin filaments and microtubules in a neuronal growth cone. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1505–1516. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannone G, Dubin-Thaler BJ, Rossier O, Cai Y, Chaga O, Jiang G, Beaver W, Dobereiner HG, Freund Y, Borisy G, Sheetz MP. Lamellipodial actin mechanically links myosin activity with adhesion-site formation. Cell. 2007;128:561–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DJ, Burmeister DW. Stages in axon formation: observations of growth of Aplysia axons in culture using video-enhanced contrast-differential interference contrast microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1921–1931. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.5.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Weeks PR. Microtubules and growth cone function. J Neurobiol. 2004;58:70–83. doi: 10.1002/neu.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabham PW, Seale GE, Bennecib M, Goldberg DJ, Vallee RB. Cytoplasmic dynein and LIS1 are required for microtubule advance during growth cone remodeling and fast axonal outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5823–5834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1135-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen GG. Evolutionary conservation of microtubule-capture mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:296–304. doi: 10.1038/nrm777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupton SL, Waterman-Storer CM. Spatiotemporal feedback between actomyosin and focal-adhesion systems optimizes rapid cell migration. Cell. 2006;125:1361–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay DG. The clutch hypothesis revisited: ascribing the roles of actin-associated proteins in filopodial protrusion in the nerve growth cone. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:114–125. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(200008)44:2<114::aid-neu3>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado C, Haserick JR, Lee J. Slipping or gripping? Fluorescent speckle microscopy in fish keratocytes reveals two different mechanisms for generating a retrograde flow of actin. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:507–518. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil K, Dent EW. Touch and go: guidance cues signal to the growth cone cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaverina I, Rottner K, Small JV. Targeting, capture, and stabilization of microtubules at early focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:181–190. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester MP, Muller O, Pollerberg GE. Adenomatous polyposis coli is differentially distributed in growth cones and modulates their steering. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12590–12600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoureux P, Buxbaum RE, Heidemann SR. Direct evidence that growth cones pull. Nature. 1989;340:159–162. doi: 10.1038/340159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell. 1996;84:359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Engel U, Rusch J, Scherrer S, Sheard K, Van Vactor D. The microtubule plus end tracking protein Orbit/MAST/CLASP acts downstream of the tyrosine kinase Abl in mediating axon guidance. Neuron. 2004;42:913–926. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau PC, Ressler AH. Inhibition of neurite initiation and growth by taxol. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1355–1362. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Forscher P. Cytoskeletal remodeling during growth cone-target interactions. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:1369–1383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.6.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L, Letourneau PC. Growth of neurites without filopodial or lamellipodial activity in the presence of cytochalasin B. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:2041–2047. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Cytoskeletal dynamics and nerve growth. Neuron. 1988;1:761–772. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KA, Tint I, Nadar CV, He Y, Black MM, Baas PW. Antagonistic forces generated by cytoplasmic dynein and myosin-II during growth cone turning and axonal retraction. Traffic. 2006;7:1333–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TP, Bentley D. Accumulation of actin in subsets of pioneer growth cone filopodia in response to neural and epithelial guidance cues in situ. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:935–948. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez OC, Schaefer AW, Mandato CA, Forscher P, Bement WM, Waterman-Storer CM. Conserved microtubule-actin interactions in cell movement and morphogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:599–609. doi: 10.1038/ncb0703-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabry JH, O'Connor TP, Evans L, Toroian-Raymond A, Kirschner M, Bentley D. Microtubule behavior during guidance of pioneer neuron growth cones in situ. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:381–395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon WC, Adams MC, Waterman-Storer CM. Dual-wavelength fluorescent speckle microscopy reveals coupling of microtubule and actin movements in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:31–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AW, Kabir N, Forscher P. Filopodia and actin arcs guide the assembly and transport of two populations of microtubules with unique dynamic parameters in neuronal growth cones. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:139–152. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter DM, Errante LD, Belotserkovsky V, Forscher P. The Ig superfamily cell adhesion molecule, apCAM, mediates growth cone steering by substrate-cytoskeletal coupling. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:227–240. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter DM, Forscher P. Substrate-cytoskeletal coupling as a mechanism for the regulation of growth cone motility and guidance. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter DM, Forscher P. Transmission of growth cone traction force through apCAM-cytoskeletal linkages is regulated by Src family tyrosine kinase activity. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:427–438. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter DM, Schaefer AW, Forscher P. Microtubule dynamics are necessary for SRC family kinase-dependent growth cone steering. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1194–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka E, Kirschner MW. The role of microtubules in growth cone turning at substrate boundaries. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:127–137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka E, Sabry J. Making the connection: cytoskeletal rearrangements during growth cone guidance. Cell. 1995;83:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka EM, Kirschner MW. Microtubule behavior in the growth cones of living neurons during axon elongation. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:345–363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney SG, Bridgman PC. Laminin stimulates and guides axonal outgrowth via growth cone myosin II activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:717–719. doi: 10.1038/nn1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RA, O'Brien ET, Pryer NK, Soboeiro MF, Voter WA, Erickson HP, Salmon ED. Dynamic instability of individual microtubules analyzed by video light microscopy: rate constants and transition frequencies. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1437–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman-Storer CM, Desai A, Bulinski JC, Salmon ED. Fluorescent speckle microscopy, a method to visualize the dynamics of protein assemblies in living cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1227–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman-Storer CM, Salmon ED. Actomyosin-based retrograde flow of microtubules in the lamella of migrating epithelial cells influences microtubule dynamic instability and turnover and is associated with microtubule breakage and treadmilling. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:417–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson T, Gordon-Weeks PR, Schachner M, Taylor J. Microtubule reorganization is obligatory for growth cone turning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15221–15226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada KM, Spooner BS, Wessells NK. Axon growth: roles of microfilaments and microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;66:1206–1212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.4.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XF, Schaefer AW, Burnette DT, Schoonderwoert VT, Forscher P. Rho-dependent contractile responses in the neuronal growth cone are independent of classical peripheral retrograde actin flow. Neuron. 2003;40:931–944. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FQ, Cohan CS. How actin filaments and microtubules steer growth cones to their targets. J Neurobiol. 2004;58:84–91. doi: 10.1002/neu.10278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FQ, Waterman-Storer CM, Cohan CS. Focal loss of actin bundles causes microtubule redistribution and growth cone turning. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:839–849. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FQ, Zhou J, Dedhar S, Wu YH, Snider WD. NGF-induced axon growth is mediated by localized inactivation of GSK-3beta and functions of the microtubule plus end binding protein APC. Neuron. 2004;42:897–912. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie 1. Microtubules explore side more than center regions in steady state Aplysia growth cones. Growth cone periphery was divided into 20 segments (green: side segments; blue: center segments). Segments cover the distal P domain from the 75% line to the leading edge. Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 5 minutes; playback time: 60× real time (6 fps). Scale bar: 10 μm.

Movie 2. Triple channel (DIC, microtubule and actin FSM) time-lapse movie of growth cone response to apCAM-coated bead. Elapsed time 0-5 minutes: before bead placement; 14-28 minutes: latency period; 29-32 minutes: traction period; 32-33 minutes: bead release. Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 33 minutes; playback time: 60× real time (6 fps). Scale bar: 10 μm.

Movie 3. Dual channel (DIC, microtubule FSM) time-lapse movie showing early exploratory microtubules (colored in blue) extending towards apCAM-bead adhesion site during the latency period. Elapsed time -6:57-0:00 minutes:seconds: before bead placement; 0:00-5:27 minutes:seconds: latency period; 5:27-7:57 minutes:seconds: traction period. Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 15 minutes; playback time: 50× real time (5 fps). Scale bar: 5 μm.

Movie 4. Triple channel (DIC, microtubule and actin FSM) time-lapse movie of structural and cytoskeletal rearrangements during the traction phase. Movie shows concomitant movement of microtubules with actin arcs and bundles in the T zone and C domain, respectively, towards apCAM bead. Microtubules and actin reference speckles are traced in the T zone (orange and yellow arrowheads) and C domain (red and pink arrowheads). Time interval: 10 seconds; elapsed time: 5 minutes; playback time: 150× real time (15 fps). Scale bar: 10 μm.