Abstract

We studied three lines of oxytocin (Oxt) and oxytocin receptor (Oxtr) knockout (KO) male mice (Oxt−/−, total Oxtr−/−, and partial-forebrain Oxtr (OxtrFB/FB)) with established deficits in social recognition to further refine our understanding of their deficits with regard to stimulus female's strain. We used a modified social discrimination paradigm in which subjects are singly housed only for the duration of the test. Additionally, stimulus females are singly-housed throughout testing and are presented within corrals for rapid comparison of investigation by subject males. Wildtype (WT) males from all three lines discriminated between familiar and novel females of three different strains (C57BL/6, Balb/c, Swiss-Webster). No KO males discriminated between familiar and novel Balb/c or C57BL/6 females. Male Oxt−/− and Oxtr−/− mice, but not OxtrFB/FB mice, discriminated between familiar and novel Swiss-Webster females. As this might indicate a global deficit in individual recognition for OxtrFB/FB males, we examined their ability to discriminate between females from different strains and compared performance with Oxtr−/− males. WT and KO males from both lines were able to distinguish between familiar and novel females from different strains, indicating the social recognition deficit is not universal. Instead, we hypothesize that the Oxtr is involved in “fine” intra-strain recognition, but is less important in “broad” inter-strain recognition. We also present the novel finding of decreased investigation across tests, which is likely an artifact of repeated testing and not due to stimulus female's strain or age of subject males.

Introduction

Social recognition, the ability to distinguish familiar from novel conspecifics, is imperative for the display of appropriate social behaviors (Ferguson et al., 2002, Winslow & Insel, 2002). Oxytocin (Oxt) administration facilitates social recognition (Dluzen et al., 1998; Benelli et al., 1995; Popik & Van Ree, 1991; Popik et al., 1996) and the development of knockout (KO) mice provided further evidence of Oxt's role in social recognition. Oxt KO mice (Oxt−/−) fail to distinguish between familiar and novel conspecifics (Ferguson et al., 2001, Ferguson et al., 2000). Two independently derived lines of Oxt receptor KO (Oxtr−/−) mice also have social recognition deficits (Lee et al., 2008, Takayanagi et al., 2005), as does a relatively forebrain-specific Oxtr KO (OxtrFB/FB) (Lee et al., 2008). However, the social recognition deficit differs between Oxtr−/− and OxtrFB/FB males when given the same social recognition task (two-trial), whereas OxtrFB/FB males show no social recognition deficit on the five-trial habituation/dishabituation task (Lee et al., 2008). These results indicate a need for further examination of the social recognition deficits of these two Oxtr KO mouse lines.

To do so, we have developed a modified version of the two-trial social discrimination task previously used by Engelmann et al, (1995). However, here we use group-housed subject males, which demonstrate better social memory than singly-housed subject males (Kogan et al., 2000). We also use singly-housed stimulus females to prevent transfer of major urinary proteins between females, which could reduce recognition of individuals by a confusion of odors (see Cheetham et al., 2007). Stimulus females are presented within corrals, which reduces direct contact between the subject and stimulus animals while still eliciting high interest and investigation by the subject (Choleris et al., 2003, Kudryavtseva et al., 2002). As males cannot directly contact corralled females there is no need to extinguish sex behavior prior to the test, as with other social recognition paradigms (see Ferguson et al., 2001, Lee et al., 2008). Finally, presenting females in corrals allows the use of gonadally intact females, which elicit higher interest from males than ovariectomized females when contact is prevented (Muroi et al., 2006).

The modified two-trial social discrimination task was used to examine social recognition in male Oxt, Oxtr, and OxtrFB/FB KOs and their male wildtype (WT) siblings. The ability of WT and KO males from each line to discriminate between females of the same strain was examined to determine whether using stimulus females from inbred (C57Bl/6 or Balb/c) or outbred (Swiss-Webster: SW) strains affects recognition abilities. WT males from all three lines distinguish between individual females of the same strain. Oxt−/− and Oxtr−/− males distinguish between SW females, but not females from the inbred strains. However, OxtrFB/FB males have a complete inability to discriminate between females of the same strain. Therefore, the ability of OxtrFB/FB males to distinguish between females from different strains is assessed and compared with Oxtr−/− males. We find that the discrimination deficit is not universal, but is instead specific to intra-strain recognition.

Methods

Animals and housing

The development and genotyping of the Oxt−/−, Oxtr−/−, and OxtrFB/FB mice were described previously (Lee et al., 2008, Young et al., 1996). Oxt KO subjects were originally an equal mix of the C57BL/6J and 129x1/SvJ strains [RW4 embryonic stem cell line (Shipley et al., 1996)] but have been repetitively backcrossed for greater than 10 generations with C57BL/6J mice (from Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME). The Oxtr gene for recombination was amplified by PCR from 129/Sv DNA and targeted into the R1 (from 129X1/SvJ × 129S1 cross; Nagy et al., 1993) embryonic stem cell line (Lee et al., 2008). Germline transmission then resulted in an equal mix of the C57BL/6J and 129/S strains. To generate forebrain-specific Oxtr KOs, we crossed the L7ag13 transgenic line (C57BL/6J genetic background) that expresses Cre recombinase under the control of the Camk2a promoter (Dragatsis & Zeitlin, 2000, Zakharenko et al., 2003) with Oxtr+/flox or Oxtrflox/flox mice that had been generated by crossing with Flp recombinase-expressing mice (Jackson Labs, stock no. 003800; C57BL/6J background) to eliminate the neomycin resistance cassette. Oxtrflox/flox male mice were crossed with female Oxtr+/flox mice that contained one transgenic allele expressing Cre recombinase (Oxtr+/flox, cre or Oxtr+/FB). The offspring thus had following genotypes: (a) Oxtr+/flox, (b) Oxtrflox/flox, (c) Oxtr+/flox,cre, and (d) Oxtrflox/flox,cre. The former two are considered WT, the third heterozygous forebrain inactivation and the fourth one forebrain-specific Oxtr KO (OxtrFB/FB). To generate whole body Oxtr KO mice, we bred male Oxtr+/flox, cre mice, which have germ cell expression of Cre recombinase, with female Oxtrflox/flox mice (Bastia et al., 2005). This led to heterozygous progeny with one Oxtr allele inactivated (Oxtr+/−). We crossed these mice to get homozygous total Oxtr KO (Oxtr−/−) mice. Further details are available in the original description (Lee et al., 2008). As both the transgenic lines expressing Flp or Cre recombinase were on a C57BL/6J background, the resulting Oxtr−/− and OxtrFB/FB mice studied here were approximately 88% and 81% C57BL/6J (rest being 129/S), respectively. All OxtrFB/FB mice are heterozygous for the Cre recombinase transgene.

All subjects used were littermates from crosses of heterozygote mice. Within each strain, subjects were taken from 6-7 breeders, with equivalent numbers of WT and KO subjects tested from each breeder (see Crusio et al., 2009). Subject males were group-housed (2-5 animals per cage) upon weaning at 21-28 days old in single-sex cages throughout testing. Gonadally intact Balb/c, C57BL/6, and SW female mice were purchased from NCI-Frederick (Frederick, MD) for use as stimulus females. Balb/c females were chosen in order to compare with our previous social recognition results using this strain (Lee et al., 2008). C57BL/6 were chosen because this strain is the primary background strain of our knockout lines, and SW females were chosen because they are a readily obtained outbred strain. Stimulus females were group-housed (5 per cage) upon receipt into the colony, and singly housed one week prior to onset of all experiments.

All animals were maintained under a 12:12 dark cycle (lights on at 0300h) with food and water available ad libitum. All tests were conducted during the light phase of the light cycle beginning between 930 and 1100 hours under dim lighting (approx 30-40 lux inside the testing cages). All animal procedures were approved by the National Institute of Mental Health Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines on the care and use of animals.

Experiment 1

Adult males (90-120 days old) from the Oxt KO, Oxtr KO, and partial forebrain-specific Oxtr KO lines were tested three times on the modified social discrimination paradigm (Figure 1). Group sizes differ across tests as data from any male that investigated during either trial 1 or trial 2 for <30 seconds (<10% of time allotted) was discarded. In the first test, Balb/c females (mean age: 110 days old) were used as stimulus animals [males: (Oxt+/+, n = 10; Oxt−/−, n = 10) (Oxtr+/+, n = 7; Oxtr−/−, n = 9) (Oxtr+/+, n = 8; OxtrFB/FB, n = 9)]. Two weeks later, the same males were again administered the social discrimination task, with C57BL/6 females (mean age: 80 days old) used as stimulus animals [males: (Oxt+/+, n = 10; Oxt−/−, n = 7) (Oxtr+/+, n = 9; Oxtr−/−, n = 9) (Oxtr+/+, n = 9; OxtrFB/FB, n = 8)]. In the third test (two weeks after the second), SW females (mean age: 80 days old) were used as stimulus animals [males: (Oxt+/+, n = 7; Oxt−/−, n = 6) (Oxtr+/+, n = 9; Oxtr−/−, n = 9) (Oxtr+/+, n = 9; OxtrFB/FB, n = 7)].

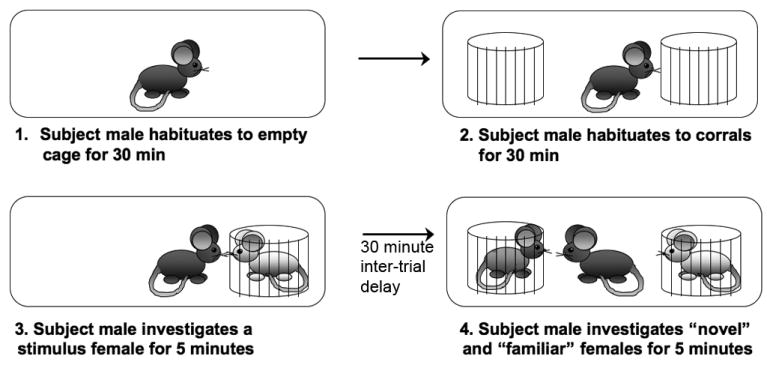

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the final social discrimination paradigm used in Experiments 1, 2, and 3.

On each test day, group-housed subject males were placed singly into new, clean cages with < 1/8″ bedding on the cage floor one hour prior to start of testing. Males were allowed to acclimate to the new cage for 30 minutes, at which point two wire corrals (www.kitchenplus.com, Item #31570) were introduced into the cage (4 ¼″ high × 4″ diameter). The space between the wire bars of the corrals permitted passage of volatile olfactory cues from the stimulus female to the subject male without allowing the male to deposit his scent on the stimulus females (Insel & Fernald, 2004), but still maintain high interest and investigation times (see Choleris et al., 2003, Choleris et al., 2006). Males were given 30 minutes to habituate to the presence of the corrals, after which a stimulus female was placed into either the left or right corral (placement was counter-balanced across genotype); the second empty corral was removed from the cage. Males were given 5 minutes of exposure to the stimulus female (trial 1); investigation was scored whenever the male did the following: (1) made direct contact with the female with either the nose or the forepaw; (2) sniffed or reached inside of the lower half of the corral; or (3) sniffed any portion of the female external to the corral (e.g., her tail). The female was removed after 5 minutes and returned to her home cage. The unused empty corral was returned to the test cage during the 30-minute inter-trial delay, although not necessarily in the same location as the corrals' left-right placements within the cage were counter-balanced across genotype to avoid development of a side preference.

Upon re-exposure (trial 2), the female from trial 1 (familiar) was placed into the same corral as in trial 1 to avoid cross-contamination of female odors. A novel female (with which the male had no prior experience) was placed into the previously empty corral. Exploration of both familiar and novel corralled females was recorded for 5 minutes using the same criteria for exploration as during trial 1. Stimulus females were returned to their home cages; subject males were weighed and returned to their group-housed home cage.

Data from each line (Oxt, Oxtr, OxtrFB/FB) were analyzed using SPSS version 13.0 (Chicago, Il). Time spent investigating 1) familiar and 2) novel females was examined via repeated measures MANOVA (genotype × test). Post-hoc analysis to determine differences across the three tests was carried out using Bonferroni correction. Depending upon significance from the MANOVA, one-way ANOVAs compared 1) differences in investigation times within each genotype across the three tests; and 2) differences across each genotype within each test. For all three lines, paired-samples t-tests were run within each genotype and test to assess ability to discriminate between familiar and novel females. For all statistical tests, significance was set at p<0.05.

Experiment 2

A new cohort of males from the OxtrFB/FB line was examined once on the social discrimination task to verify their inability to distinguish between SW females. The social discrimination task as administered as described in Experiment 1 (see Figure 1). Subject males averaged 100 days old, and consisted of 3 genotypes: Oxtr+/+ (n = 8), OxtrFB/FB (n = 7), and Oxtr+/flox,cre (n = 8). The latter group was tested to determine whether expression of Cre recombinase in the transgenic line used to generate the OxtrFB/FB mice might affect the social recognition phenotype. An ANOVA was run to assess differences across genotypes for time spent investigating 1) familiar and 2) novel females. Paired-samples t-tests were run within each genotype to assess ability to discriminate between familiar and novel females. For all statistical tests, significance was set at p<0.05.

Experiment 3

New cohorts of males from the Oxtr−/− and OxtrFB/FB lines were examined in the social discrimination task to determine ability to discriminate between females of two different strains. The social discrimination task was administered as described in Experiment 1 (see Figure 1). Adult males from both the Oxtr−/− and OxtrFB/FB lines were tested three times, with 4 weeks between tests. On the first test [(Oxtr line: average 95 days old; Oxtr+/+, n = 9; Oxtr−/−, n = 10) (OxtrFB/FB line: average 102 days old; Oxtr+/+, n = 12; OxtrFB/FB, n = 11)], a C57BL/6 and a Balb/c female were presented. On the second test, [(Oxtr line: average 128 days old; Oxtr+/+, n = 9; Oxtr−/−, n = 10) (OxtrFB/FB line: average 136 days old; Oxtr+/+, n = 12; OxtrFB/FB, n = 11)], a C57BL/6 and a SW female were presented. On the final test, [(Oxtr line: average 155 days old; Oxtr+/+, n = 7; Oxtr−/−, n = 10) (OxtrFB/FB line: average 166 days old; Oxtr+/+, n = 11; OxtrFB/FB, n = 10)], a Balb/c and a SW female were presented. Strain and left-right position of female presented as “familiar” were counterbalanced across genotype and test. Females were approximately 60 days old on test 1, 85 days old on test 2, and 110 days old on test 3. Statistical analysis was identical to that described for Experiment 1.

Experiment 4

The results from Experiments 1 and 2 indicated that age could be a factor in the decreased exploration observed from test 1 to 3. Therefore, comparisons were made between old (160-190 days; Oxtr+/+, n = 7; OxtrFB/FB, n = 5) and young (80-95 days; Oxtr+/+, n = 9; OxtrFB/FB, n = 8) males. Subjects were tested once using Balb/c females (approximately 60 days old) as stimulus animals. A two-way MANOVA (genotype × age) was run to assess differences across genotypes and ages for time spent investigating 1) familiar and 2) novel females. Paired-samples t-tests were run within each genotype for each age to assess ability to discriminate between familiar and novel females. For all statistical tests, significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Experiment 1

Social discrimination in Oxt KO males

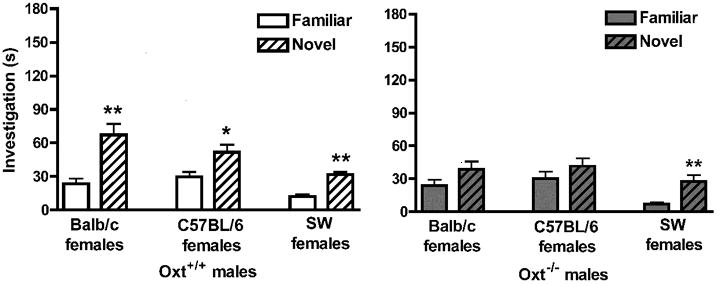

Oxt+/+ and Oxt−/− males were assessed three times on the social discrimination task (Figure 2). A repeated measures MANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype (WT, KO) [F1,44 = 3.86, p<0.05]; female (familiar, novel) [F1,44 = 39.55, p<0.001]; and test (1, 2, 3) [F2,44 = 9.07, p<0.001]. Generally, Oxt+/+ males investigated all females more than Oxt−/− males, and novel females were investigated more than familiar females by all subjects. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed decreased investigation times for familiar and novel females on test 3 (SW females) compared to test 1 (Balb/c females; p<0.001) and test 2 (C57BL/6 females; p<0.001; Figure 2). There was a trend towards a genotype × female interaction [F1,44 = 3.39, p=0.07], but no other significant interactions. Accordingly, ANOVAs comparing within-genotype differences across the three tests and between-genotype differences within each test could not be carried out.

Figure 2.

Social recognition memory in Oxt WT and KO mice. Data are investigation times in seconds (mean ± SEM) and were analyzed via repeated-measures MANOVA (genotype × test). (a) Oxt+/+ (WT) males significantly discriminated between familiar and novel Balb/c stimulus females (left; **p<0.01), C57BL/6 stimulus females (middle; *p<0.05), and SW females (right; **p<0.01). (b) Oxt−/− (KO) males were unable to discriminate between familiar and novel Balb/c stimulus females (left) or C57BL/6 stimulus females (middle), but discriminated between familiar and novel SW females (right; **p < 0.01).

Within each genotype for each of the three tests, investigation times of familiar and novel females were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Oxt+/+ males (Figure 2a) discriminated between familiar and novel Balb/c females (p<0.05; left), C57BL/6 females (p<0.05; middle) and SW females (p<0.01; right), as measured by a significant difference in investigation times. In contrast, Oxt−/− males (Figure 2b) did not discriminate between familiar and novel Balb/c females (p>0.08; left) or C57BL/6 females (p>0.10; middle), but did discriminate between familiar and novel SW females (p<0.01, right).

Social discrimination in Oxtr KO males

Oxtr+/+ and Oxtr−/− males were tested three times on the social discrimination task (Figure 3). A repeated measures MANOVA revealed a significant main effects of female (familiar, novel) [F1,46 = 72.81, p<0.001] and test (1, 2, 3) [F2,46 = 11.32, p<0.001]. Generally, all subjects investigated novel females more than familiar females. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed decreased investigation times on test 3 (SW females) compared to test 1 (Balb/c females; p<0.05) and test 2 (C57BL/6 females; p < 0.001; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Social recognition memory in Oxtr WT and KO mice. Data are investigation times in seconds (mean ± SEM) and were analyzed via repeated-measures MANOVA (genotype × test). (a) Oxtr+/+ (WT) males significantly discriminated between familiar and novel Balb/c stimulus females (left; ***p<0.001), C57BL/6 stimulus females (middle; *p<0.05), and SW females (right; *p<0.05). Oxtr+/+ males investigated novel Balb/c females significantly more than novel C57BL/6 or SW females (##p<0.01). (b) Oxtr−/− (KO) males were unable to discriminate between familiar and novel Balb/c stimulus females (left) or C57BL/6 stimulus females (middle), but discriminated between familiar and novel SW females (right; *p<0.05). Oxtr−/− males investigated familiar SW females significantly less than familiar Balb/c or C57BL/6 females (#p<0.05).

There was no significant main effect of genotype (WT, KO) [F1,46 = 2.88, p>0.05], but there were significant female × genotype [F1,46 = 8.73, p<0.01] and female × genotype × test [F2,46 = 5.19, p<0.01] interactions. Therefore, data from Oxtr+/+ and Oxtr−/− males were analyzed separately via one-way ANOVAs comparing performances within genotype across the three tests. Oxtr+/+ males differed across the three tests in investigation of the novel females [F2,24 = 11.93, p<0.001]. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed that Oxtr+/+ males spent more time investigating the novel females during test 1 (Balb/c females) than during test 2 (C57BL/6 females) and test 3 (SW females); p<0.01 for both (Figure 3a). Oxtr−/− males differed across the three tests in investigation of the familiar females [F2,24 = 6.10, p<0.01]. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferonni correction revealed that Oxtr−/− males spent significantly less time investigating the familiar females during test 3 than test 1 or test 2 (p<0.05; Figure 3b).

Within each genotype for each of the three tests, investigation times of familiar and novel females were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Oxtr+/+ males (Figure 3a) discriminated between familiar and novel Balb/c females (p<0.001; left), C57BL/6 females (p<0.05; middle) and SW females (p<0.05; right), as measured by a significant difference in investigation times. In contrast, Oxtr−/− males (Figure 3b) did not discriminate between familiar and novel Balb/c females (p>0.08; left) or C57BL/6 females (p>0.10; middle), but did discriminate between familiar and novel SW females (p<0.01, right).

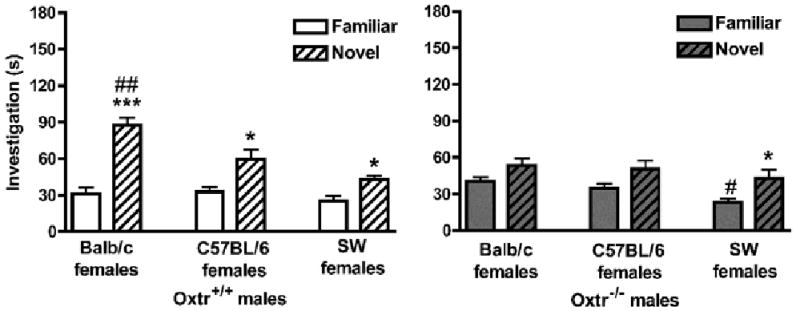

Social discrimination in OxtrFB/FB males

Oxtr+/+ and OxtrFB/FB males were tested three times on the social discrimination task (Figure 4). A repeated measures MANOVA revealed significant main effects of female (familiar, novel) [F1,44 = 41.00, p<0.001]; and test (1, 2, 3) [F2,44 = 9.58, p<0.001]. Generally, Oxtr+/+ males investigated all females more than OxtrFB/FB males, and all subjects investigated novel females more than familiar females. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed decreased investigation times for familiar and novel females on test 3 (SW females) compared to test 1 (Balb/c females; p<0.01) and test 2 (C57BL/6 females; p<0.001; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Social recognition memory in OxtrFB/FB WT and KO mice. Data are investigation times in seconds (mean ± SEM) and were analyzed via repeated-measures MANOVA (genotype × test). (a) Oxtr+/+ (WT) males significantly discriminated between familiar and novel Balb/c stimulus females (left; **p<0.01), C57BL/6 stimulus females (middle; **p<0.01), and SW females (right; *p<0.05). Oxtr+/+ males investigated novel SW females significantly less than novel Balb/c or C57BL/6 females (#p<0.05). (b) OxtrFB/FB (KO) males were unable to discriminate between familiar and novel Balb/c stimulus females (left), C57BL/6 stimulus females (middle), and SW females (right). OxtrFB/FB males investigated familiar SW females significantly less than familiar Balb/c or C57BL/6 females (###p<0.001).

There was no significant main effect of genotype (WT, KO) [F1,44 = 3.79, p = 0.06], but there was a significant female × genotype interaction [F1,44 = 6.17, p<0.05]. No other interactions were significant. To examine the interaction, data from Oxtr+/+ and OxtrFB/FB males were analyzed separately via one-way ANOVA comparing performances within genotype across the three tests. Oxtr+/+ males differed across the three tests in investigation of the novel females [F2,25 = 3.98, p<0.05]. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed that Oxtr+/+ males spent less time investigating the novel females during test 3 than during test 1 or test 2 (p<0.05; Figure 4a). OxtrFB/FB males differed across the three tests in investigation of the familiar females [F2,23 = 5.38, p<0.05]. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed that OxtrFB/FB males spent significantly less time investigating the familiar females during test 3 than test 1 (p<0.001; Figure 4b).

Within each genotype for each of the three tests, investigation times of familiar and novel females were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Oxtr+/+ males (Figure 4a) discriminated between familiar and novel Balb/c females (p<0.01; left), C57BL/6 females (p<0.01; middle) and SW females (p<0.05; right), as measured by a significant difference in investigation times. In contrast, OxtrFB/FB males (Figure 4b) did not discriminate between familiar and novel Balb/c females (p>0.10; left), C57BL/6 females (p>0.08; middle), or SW females (p>0.10, right).

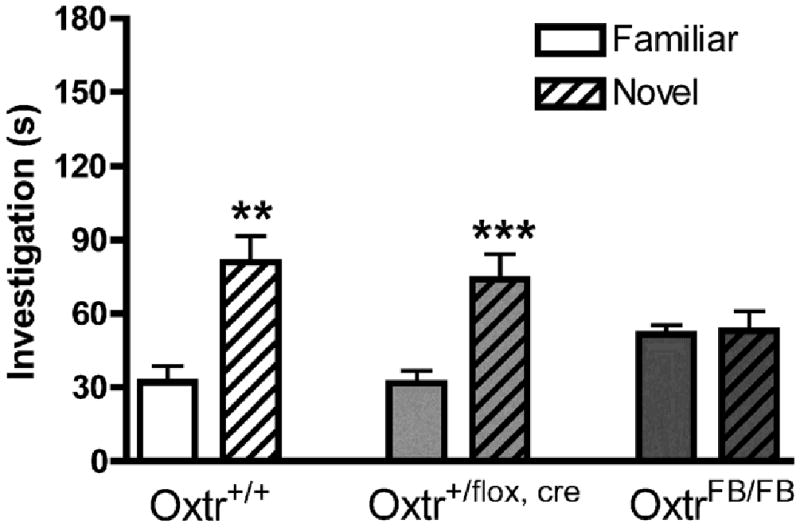

Experiment 2

A new cohort of males from the OxtrFB/FB line was tested once on the social discrimination task using SW females as stimulus animals (Figure 5). An ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype [F4,40 = 3.22, p<0.05] and a significant genotype × familiar female interaction [F2,20 = 4.35, p<0.05]. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed that OxtrFB/FB males spent significantly more time investigating familiar females than did Oxtr+/+ or Oxtr+/flox,cre males. Within each genotype, differences in investigation times of familiar and novel females were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Oxtr+/+ males (Figure 5, left) and Oxtr+/flox,cre males (Figure 5, middle) both discriminated between familiar and novel SW females (p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively), whereas OxtrFB/FB males (which are also heterozygous for the Cre recombinase transgene) spent equivalent times with familiar and novel SW females (Figure 5, right; p>0.10).

Figure 5.

Social recognition memory for SW females in Oxtr WT, Oxtr+/flox,cre (heterozygous for both forebrain Oxtr inactivation and the Cre recombinase transgene), and OxtrFB/FB (homozygous for forebrain Oxtr inactivation and heterozygous for the Cre recombinase transgene) mice. Data are investigation times in sections (mean ± SEM) and were analyzed via paired samples t-tests. WT (Oxtr+/+, left) and heterozygote (Oxtr+/flox,cre, middle) males both discriminated between familiar and novel SW stimulus females (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). KO males (OxtrFB/FB) did not.

As there were no differences across genotypes in investigation of the novel females [F2,20 = 2.05, p>0.10], these results indicate that the inability of OxtrFB/FB males to discriminate between familiar and novel SW females is due to increased investigation of the familiar females. These results are different from those observed in Experiment 1, in which OxtrFB/FB males seemed to spend slightly more time investigating the novel SW females, although not significantly so (Figure 4, right). These differences in investigation of the familiar females are likely an artifact of the repeated testing design used in Experiment 1, as SW females were presented on the third test in Experiment 1, but on the first test in this experiment.

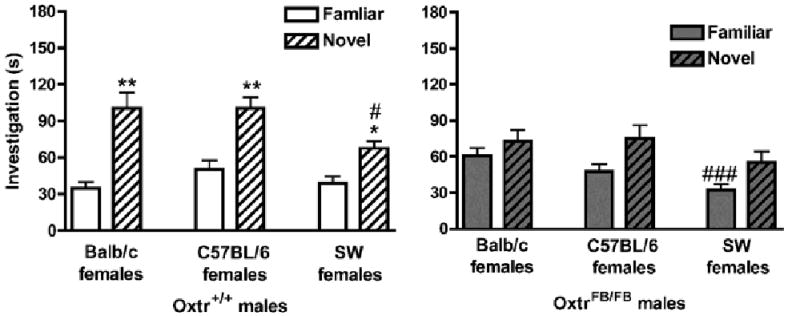

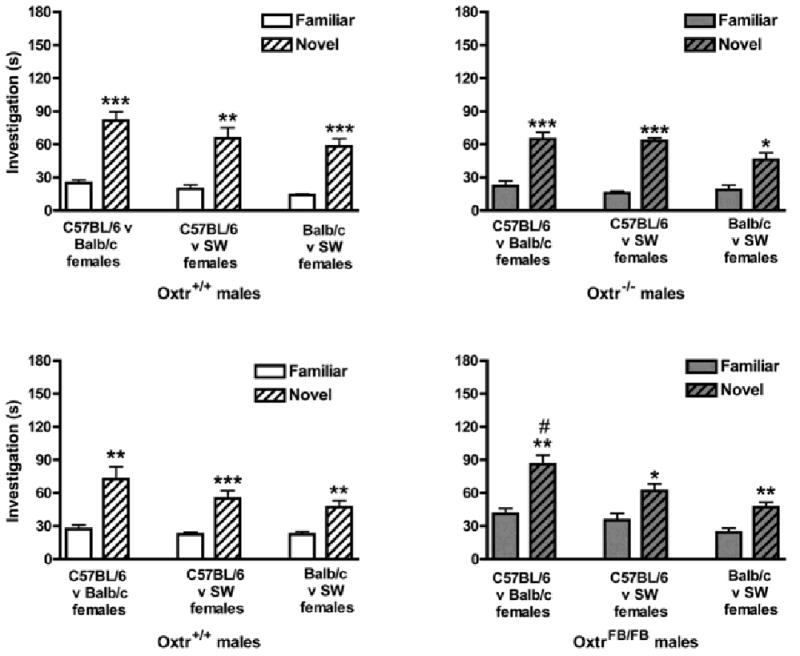

Experiment 3

New cohorts of males from the Oxtr+/+ and OxtrFB/FB lines were tested three times each on the social discrimination task, using females from two different strains as stimulus animals at each test (test 1: C57BL/6 v Balb/c; test 2: C57BL/6 v SW; test 3: Balb/c v SW) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Social recognition memory in two lines of Oxtr mice for females of different strains. Data are investigation times in seconds (mean ± SEM) and were analyzed via repeated-measures MANOVA (genotype × test). (a) WT (Oxtr+/+) and (b) KO (Oxtr−/−) males from the total Oxtr line, and (c) WT (Oxtr+/+) and (d) KO (OxtrFB/FB) males from the partial forebrain-specific Oxtr line all successfully discriminated between familiar and novel stimulus females (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). OxtrFB/FB males investigated the novel females significantly more on the first test (d, left) than the second (d, middle) or third (d, right) tests (#p<0.05).

Oxtr−/− males

A repeated measures MANOVA revealed significant effects of female (familiar, novel) [F1,49 = 195.42, p<0.001] and test (1, 2, 3) [F2,49 = 6.77, p<0.01]. Generally, all subjects investigated novel females more than familiar females. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferonni correction revealed decreased investigation times for test 3 (p<0.01) compared with test 1. There were no other significant main effect of genotype, and no significant interactions. Accordingly, ANOVAs comparing within-genotype differences across the three tests and between-genotype differences within each test could not be carried out.

Within each genotype for each of the three tests, investigation times of familiar and novel females were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Oxtr+/+ males (Figure 6a) investigated the novel females more than the familiar female on test 1 (p<0.001; left), test 2 (p<0.01; middle), and test 3 (p<0.001; right). Oxtr−/− males (Figure 6b) also discriminated between novel and familiar females, spending significantly more time investigating the novel females on test 1 (p<0.001; left), test 2 (p<0.001; middle) and test 3 (p<0.05; right).

OxtrFB/FB males

A repeated measures MANOVA revealed significant effects of genotype (WT, KO) [F1,61 = 5.23, p<0.05], female (familiar, novel) [F1,61 = 82.18, p<0.001], and test (1, 2, 3) [F1,61 = 21.33, p<0.001]. Generally, OxtrFB/FB males investigated all females more than Oxt+/+ males, and novel females were investigated more than familiar females by all subjects. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferonni correction revealed decreased investigation times by all subjects for test 2 (p<0.01) and test 3 (p<0.001) compared with test 1.

There was a significant female × test interaction [F2,31 = 8.31, p<0.001], but no other significant interactions. To examine the interaction, data from Oxtr+/+ and OxtrFB/FB males were analyzed separately with a one-way ANOVA comparing performance within genotype across the three tests. Oxtr+/+ males did not differ in investigation of familiar or novel females across the three tests (Figure 6c), whereas OxtrFB/FB males differed in investigation of the novel females across the three tests [F2,31 = 8.31, p<0.001]. Post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni correction revealed that OxtrFB/FB males spent significantly more time investigating the novel females during test 1 than test 2 or test 3 (p<0.05; Figure 6d).

Within each genotype for each of the three tests, investigation times of familiar and novel females were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Oxtr+/+ males (Figure 6c) investigated the novel females more than the familiar females on test 1 (p<0.01; left), test 2 (p<0.001; middle), and test 3 (p<0.01; right). OxtrFB/FB males (Figure 6d) also discriminated between novel and familiar females, spending significantly more time investigating the novel females on test 1 (p<0.01; left), test 2 (p<0.05; middle) and test 3 (p<0.01; right).

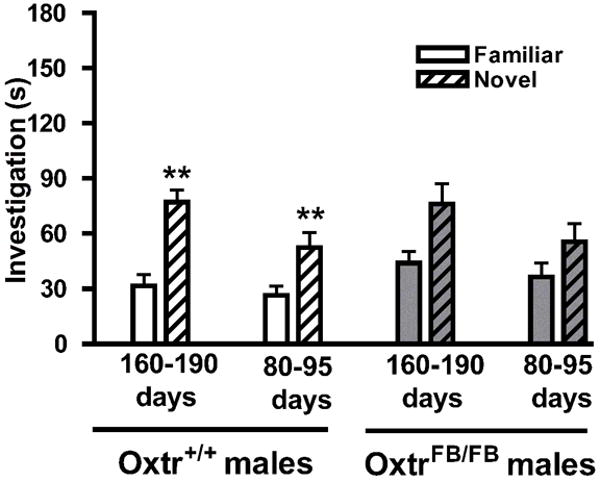

Experiment 4

To determine whether age affected performance on the social discrimination task, old (160-190 days) and young (80-95 days) Oxtr+/+ and OxtrFB/FB males were tested using Balb/c females as stimulus animals. A two-way (genotype × age) MANOVA revealed no significant main effects of genotype (WT, KO) or age (old, young), and no significant interaction (p>0.05 for all). Therefore, age of subject males did not affect investigation of stimulus females. Complementary with results from Experiments 1 and 2, paired samples t-tests revealed that all Oxtr+/+ males (regardless of age) investigated novel females significantly more than familiar females (p<0.01; Fig. 7 left), whereas OxtrFB/FB males did not (p>0.08 for both old and young; Fig. 7 right).

Figure 7.

Social recognition memory in young and old OxtrFB/FB males. Data are investigation times (mean ± SEM) for Oxtr+/+ (WT, left) and OxtrFB/FB (KO, right) males and were analyzed via MANOVA (genotype × age). No differences existed in investigation due to age; only Oxtr+/+ males discriminated between familiar and novel females (**p<0.01).

Discussion

We used a modified version of a social discrimination task to assess social recognition memory in WT and KO males from Oxt, Oxtr, and partial forebrain-specific Oxtr mouse lines. In agreement with previous studies using other social recognition tasks (Ferguson et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2008, Takayanagi et al., 2005). WT males from all three lines discriminated between familiar and novel stimulus females of the same strains (Figures 2-7). This study is the first to demonstrate intact social recognition in WT males independent of stimulus female's strain, but impaired social recognition in KO males dependent upon stimulus female's strain. Oxt−/− and Oxtr−/− males did not discriminate between familiar and novel Balb/c or C57BL/6 females (as shown previously in Oxtr lines: Takayanagi et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2008), but did discriminate between familiar and novel outbred SW females (contrary to Choleris et al., 2003 in a different paradigm)(Figures 2, 3). The ability to discriminate between SW females may be specific to the strain and not generalizable to all outbred strains, as Oxt KO mice cannot distinguish in another paradigm between CD-1 mice (Ferguson et al., 2001, Ferguson et al., 2000).

Feral female mice are more likely to mate within their own strain than with a male from another strain. Oxt−/− females are unable to successfully discriminate between odors from healthy males and those infected with a parasite (Kavaliers et al., 2003). Oxt is therefore implicated in the ability to choose a mate who is parasite-free, more fit, and is less likely to infect the female during mating (see Kavaliers et al., 2005), consistent with an increased emphasis on the role of Oxt in intra-strain recognition.

Unlike the Oxt and Oxtr KO males, OxtrFB/FB males did not discriminate between familiar and novel females regardless of stimulus strain, including SW (Figure 4). OxtrFB/FB males spent only 60% of their time investigating the novel SW female, compared with 69% in Oxtr−/− males and 80% in Oxt−/− males. We have previously reported a general decrease in investigation of all stimulus animals (whether familiar or novel) in OxtrFB/FB males, but a maintained recognition memory on the habituation-dishabituation social recognition task (Lee et al., 2008). The current results refine those obtained with the two-trial social recognition task (Lee et al., 2008), clarifying the deficit in social memory in the OxtrFB/FB line.

The targeted mutation is the same in the Oxtr−/− and OxtrFB/FB mice and the three strains differ slightly in genetic background (see Methods). However, as performances on the social discrimination task by WT males from the Oxt and Oxtr lines are identical, it is unlikely that background strain plays a large role. Both total Oxt−/− and Oxtr−/− males show the same social discrimination deficit, indicating that 129Sv flanking DNA is unlikely to be responsible. The presence of Cre recombinase allele in the OxtrFB/FB males could account for the inability of OxtrFB/FB males to discriminate between SW females. However, in Experiment 2 heterozygous mice (for both Cre recombinase and forebrain Oxtr inactivation) had nearly identical performances to the WT males, and discriminated between familiar and novel SW females. Therefore, Experiment 2 indicates that the Cre recombinase transgene does not account for the social recognition defect in OxtrFB/FB males.

Instead, the results from Experiments 1 and 2 indicated that OxtrFB/FB males may have a general inability to recognize individuals. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ability of OxtrFB/FB and Oxtr−/− males to discriminate between females from different strains. We hypothesized that OxtrFB/FB males would not make this discrimination, but WT males and Oxtr−/− males would. Contrary to the hypothesis, WT and KO males from both lines were equally able to discriminate between familiar and novel females of different strains (Figure 6). Why should OxtrFB/FB males be unable to distinguish between females of the same strain, but able to distinguish between females of different strains? One possibility may be that the postnatal loss of the Oxtr in the OxtrFB/FB in contrast to never expressing Oxtr in the total Oxtr KO leads to the difference. Another possibility may lie with the distribution of the Oxtr within the brain. Deletion of the Oxtr in the OxtrFB/FB conditional line is not complete, with Oxtr expression remaining within the medial amygdala, olfactory bulb, and neocortex, but lacking in the hippocampal formation (Lee et al., 2008). As both the amygdala and the hippocampal formation (including the entorhinal cortex) are important for individual recognition (Ferguson et al., 2001; Petrulis, 2009, respectively), the altered Oxtr expression pattern in the OxtrFB/FB conditional line may prevent OxtrFB/FB males from discriminating between females of the same strain, even if outbred, but allow discrimination between the greatly different odors of females from different strains. In other words, lack of and/or presence of Oxtr in the above-mentioned regions interferes with ability to make “difficult” discriminations (i.e., between females of the same strain), but is not involved in making “easy” discriminations (i.e., between females of different strains). Results from Oxtr KO males indicate that in the complete absence of Oxtr, mice are able to distinguish between different strains. Combined, our data indicates that Oxt acting at the Oxtr may be involved in more detailed individual recognition, but some other peptide or hormone may underlie broad recognition of individuals. For example, follow up studies using this social discrimination paradigm in vasopressin 1a and 1b receptor KO males are planned to determine whether the closely related peptide may be involved in more general individual recognition.

WT males from all three lines were very consistent in their investigation times, with all spending approximately 75% of the time with the novel females on test 1; 63-68% of the time investigating the novel females on test 2; and 65-70% of the time investigating the novel females on test 3. In contrast, the two-trial social recognition tasks may result in greatly different investigation times of familiar females (compared to novel) [e.g., only ∼40% in (Lee et al., 2008), but ∼75% in (Ferguson et al., 2000)]. Inconsistent performance across KO lines when utilizing the same task makes it difficult to compare results directly. We hope that the current task, which uses group-housed subjects and singly-housed gonadally-intact stimulus animals contained within corrals, will result in consistent performance across labs using C57BL/6 and C57BL/129 background lines. We have found highly correlated scores from two different intra-lab investigators (r = 0.991; data not shown), indicating that with appropriate training and exposure to the task, scoring is consistent across investigators.

There is a possible confound of estrous state influencing male investigation with use of gonadally-intact females, which were chosen as they elicit higher interest from males than ovariectomized females. However, the day of estrous cycle has previously not been shown to greatly influence male investigation (Muroi et al., 2006). Females in all states of estrous elicit higher investigation from males than do ovariectomized females (Ingersoll & Weinhold, 1987). Sexually-naïve males (as are the subjects in the current experiments) indicate no preference between receptive and non-receptive females' odors (Carr et al., 1965). Furthermore, subjects of both genotypes would experience any effect of estrous state, thereby eliminating possible genotype × estrous condition interaction.

We believe this study is the first to repeatedly test males' social recognition memory. We find that repeated testing does not interfere with discrimination ability, but does generally result in decreased investigation times by test 3. A previous study indicates that mice from C57BL/6 and 129S2/SvHad strains decrease exploration and activity with repeated testing and handling (Voikar et al., 2004). Males were 2-3 months older at the third test compared to the first. However, we found no overall effect of age on investigation times for both Oxtr+/+ and OxtrFB/FB males (Figure 7). It is therefore likely that the decrease in investigation in the current study is an artifact of repeated testing. Furthermore, as in the third test in Experiment 1, Experiment 2 (Figure 5) shows that WT males discriminated in a single test between familiar and novel SW females, while OxtrFB/FB males did not. These results indicate that the social recognition deficit observed in Experiment 1 is true, and not an artifact of repeated testing. Thus, Experiment 2 suggests that order of presentation of stimulus female's strain does not affect social recognition ability in OxtrFB/FB males. These results do underscore the importance of limiting testing history for animals used in social recognition tests, as previous testing can impact willingness to investigate.

The current study expands upon earlier findings that Oxt and the Oxtr are important in social recognition. Our results indicate that Oxt and the Oxtr are less important for “broad” social recognition (inter-strain), but are seemingly more important for “fine” social recognition (intra-strain). These results were obtained utilizing a modified social discrimination paradigm that generates very similar investigation times by WT males of stimulus females across all lines tested.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NEI/NIMH Animal Facilities staff in Building 49 for their exceptional animal care and daily assistance, particularly Ana Carderas and Darwin Romero. Drs. Scott Wersinger, Heather Caldwell, and Jerome Pagani provided excellent comments on early versions of this manuscript. We also thank Jim Heath and Emily Shepard for technical assistance. This research was supported by NIMH (Z01-MH-002498-20) from the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, DHHS.

References

- Bastia E, Xu YH, Scibelli AC, Day YJ, Linden J, Chen JF, Schwarzschild MA. A crucial role for forebrain adenosine A(2A) receptors in amphetamine sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:891–900. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli A, Bertolini A, Poggioli R, Menozzi B, Basaglia R, Arletti R. Polymodal dose-response curve for oxytocin in the social recognition test. Neuropeptides. 1995;28:251–255. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(95)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr WJ, Loeb LS, Dissinger ML. Responses of Rats to Sex Odors. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1965;59:370–377. doi: 10.1037/h0022036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham SA, Thom MD, Jury F, Ollier WE, Beynon RJ, Hurst JL. The genetic basis of individual-recognition signals in the mouse. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1771–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choleris E, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Muglia LJ, Pfaff DW, Ogawa S. An estrogen-dependent four-gene micronet regulating social recognition: a study with oxytocin and estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6192–6197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631699100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choleris E, Ogawa S, Kavaliers M, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Muglia LJ, Pfaff DW. Involvement of estrogen receptor alpha, beta and oxytocin in social discrimination: A detailed behavioral analysis with knockout female mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:528–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusio WE, Goldowitz D, Holmes A, Wolfer D. Standards for the publication of mouse mutant studies. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluzen DE, Muraoka S, Engelmann M, Landgraf R. The effects of infusion of arginine vasopressin, oxytocin, or their antagonists into the olfactory bulb upon social recognition responses in male rats. Peptides. 1998;19:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragatsis I, Zeitlin S. CaMKIIalpha-Cre transgene expression and recombination patterns in the mouse brain. Genesis. 2000;26:133–135. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<133::aid-gene10>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann M, Wotjak CT, Landgraf R. Social discrimination procedure: an alternative method to investigate juvenile recognition abilities in rats. Physiol Behav. 1995;58:315–321. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00053-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Aldag JM, Insel TR, Young LJ. Oxytocin in the medial amygdala is essential for social recognition in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8278–8285. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08278.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Hearn EF, Matzuk MM, Insel TR, Winslow JT. Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:284–288. doi: 10.1038/77040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Insel TR. The neuroendocrine basis of social recognition. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:200–224. doi: 10.1006/frne.2002.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll DW, Weinhold LL. Modulation of male mouse sniff, attack, and mount behaviors by estrous cycle-dependent urinary cues. Behav Neural Biol. 1987;48:24–42. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(87)90544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Fernald RD. How the brain processes social information: searching for the social brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:697–722. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaliers M, Choleris E, Pfaff DW. Recognition and avoidance of the odors of parasitized conspecifics and predators: differential genomic correlates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:1347–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaliers M, Colwell DD, Choleris E, Agmo A, Muglia LJ, Ogawa S, Pfaff DW. Impaired discrimination of and aversion to parasitized male odors by female oxytocin knockout mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:220–230. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan JH, Frankland PW, Silva AJ. Long-term memory underlying hippocampus-dependent social recognition in mice. Hippocampus. 2000;10:47–56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<47::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtseva NN, Bondar NP, Avgustinovich DF. Association between experience of aggression and anxiety in male mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Caldwell HK, Macbeth AH, Tolu SG, Young WS., 3rd A conditional knockout mouse line of the oxytocin receptor. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3256–3263. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroi Y, Ishii T, Komori S, Nishimura M. A competitive effect of androgen signaling on male mouse attraction to volatile female mouse odors. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrulis A. Neural mechanisms of individual and sexual recognition in Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Behav Brain Res. 2009;200:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popik P, van Ree JM. Oxytocin but not vasopressin facilitates social recognition following injection into the medial preoptic area of the rat brain. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1991;1:555–560. doi: 10.1016/0924-977x(91)90010-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popik P, Vetulani J, Van Ree JM. Facilitation and attenuation of social recognition in rats by different oxytocin-related peptides. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;308:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley JM, Wesselschmidt RL, Kobayashi DK, Ley TJ, Shapiro SD. Metalloelastase is required for macrophage-mediated proteolysis and matrix invasion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3942–3946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16096–16101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505312102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voikar V, Vasar E, Rauvala H. Behavioral alterations induced by repeated testing in C57BL/6J and 129S2/Sv mice: implications for phenotyping screens. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:27–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-183x.2003.0044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow JT, Insel TR. The social deficits of the oxytocin knockout mouse. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:221–229. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young WS, 3rd, Shepard E, Amico J, Hennighausen L, Wagner KU, LaMarca ME, McKinney C, Ginns EI. Deficiency in mouse oxytocin prevents milk ejection, but not fertility or parturition. J Neuroendocrinol. 1996;8:847–853. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1996.05266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharenko SS, Patterson SL, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin SO, Siegelbaum SA, Kandel ER, Morozov A. Presynaptic BDNF required for a presynaptic but not postsynaptic component of LTP at hippocampal CA1-CA3 synapses. Neuron. 2003;39:975–990. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]