Abstract

Drosophila melanogaster curled, one of the first fly mutants described by T. H. Morgan >90 years ago, is the founding member of a series of curled wing phenotype mutants widely used as markers in fruit fly genetics. The expressivity of the wing phenotype is environmentally modulated, suggesting that the mutation affects the metabolic status of cells rather than a developmental control gene. However, the molecular identity of any of the curled wing marker mutant genes is still unknown. In a screen for starvation-responsive genes, we previously identified the single fly homolog of the vertebrate nocturnin genes, which encode cytoplasmic deadenylases that act in the post-transcriptional control of genes by poly(A) tail removal of target mRNAs prior to their degradation. Here we show that curled encodes Drosophila Nocturnin and that the gene is required at pupal stage for proper wing morphogenesis after eclosion of the fly. Despite the complex ontogenetic expression pattern of the gene, curled is not expressed in the developing wing, and wing-specific curled knockdown mediated by RNAi does not result in the curled wing phenotype, indicating a tissue-nonautonomous, systemic mode of curled gene function. Our study not only presents an entry point into the functional analysis of invertebrate nocturnins but also paves the way for the identification of the still elusive Nocturnin target mRNAs by genetic suppressor screens on the curled wing phenotype.

ON December 15th, 1915 Thomas H. Morgan described the first curled (cu) mutant Drosophila melanogaster (Bridges and Morgan 1923). The posterior wing part of curled mutant flies is bent upwards, an eponymous phenotype, which made curled the founding member of a series of recessive or dominant marker mutations. They include curled on X (Krivshenko 1958), curl (Goldschmidt 1944), curlex (Lindsley and Grell 1968), Curled 3 (Meyer 1952), Curlyoid (Curry 1939), Curly (Ward 1923), and Upturned (Ball 1935). Curly and curled are among the most popular wing marker mutations for research and are used daily in Drosophila research laboratories worldwide.

Despite the widespread use of curled wing mutants the morphogenetic cause of this phenotype is unclear. It has been proposed that curled wings result from contraction differences between the dorsal and ventral wing surfaces while the expanded wings dry after eclosion (Waddington 1940) and there are indications for a functional interrelationship among the curled winged phenotype mutants since curled is incompletely dominant in Curly mutants (Nozawa 1956a). Since similar wing phenotypes have also been described for D. pseudoobscura and D. montium mutants (Sturtevant and Novitski 1941), the mechanism underlying curled wing formation is likely to be evolutionarily conserved among Drosophilids. Moreover, the phenotypic expressivity of different curled wing mutants is variable depending on environmental factors such as larval nutrition during defined ontogenetic stages (Nozawa 1956a,b). Finally, the expressivity of the curled mutant wing phenotype has a cold-sensitive phase during late pupal stage (Nozawa 1956a). However, despite a long history of curled wing mutants none of the curled wing marker genes has been molecularly identified to date.

Recently we performed a genomewide screen to identify and characterize starvation-responsive genes in adult Drosophila flies (Grönke et al. 2005). Among the starvation-induced genes was the fly homolog of the vertebrate circadian rhythm effector gene nocturnin (no; CG31299), originally described as circadian rhythm gene in Xenopus laevis retinal photoreceptor cells (Green and Besharse 1996). Various other vertebrate nocturnins exert a circadian expression mode, most prominently in the mouse liver (Wang et al. 2001; Barbot et al. 2002) and in the human hepatoma cell line Huh7 (Li et al. 2008). In nocturnin knockout mice the central clock is unaffected but the mutant animals develop severe metabolic phenotypes due to impaired lipid uptake or utilization causing resistance to diet-induced obesity and hepatic steatosis (Green et al. 2007).

Nocturnin genes encode evolutionarily highly conserved members of a subfamily of the yCCR4-related protein family (Dupressoir et al. 2001), named after yeast Carbon Catabolite Repressor 4 (CCR4) (Denis 1984). All yCCR4-related proteins encode a C-terminal Mg2+-dependent endonuclease-like domain (endo/exonuclease/phosphatase domain; pfam03372) (Dupressoir et al. 2001). The yCCR4-related protein family consists of four distinct subfamilies named after the proteins Nocturnin, Angel, 3635, and CCR4. The CCR4 subfamily proteins are catalytic components of a major cytoplasmic deadenylation complex in eukaryotes initiating mRNA decay by exonucleolytic 3′-5′ poly(A) tail removal (Chen et al. 2002). Like the yeast and vertebrate orthologs, the Drosophila CCR4 protein, which is encoded by the gene twin, acts as deadenylase on a number of different specific target mRNAs during embryogenesis and oogenesis as well as during heat-shock recovery (Temme et al. 2004; Morris et al. 2005; Semotok et al. 2005; Bönisch et al. 2007; Chicoine et al. 2007; Kadyrova et al. 2007). As yet the function of the Drosophila yCCR4-related protein subfamily representatives Angel and 3635 has not been studied.

Vertebrate Nocturnin proteins also exert deadenylase activity in vitro (Baggs and Green 2003; Garbarino-Pico et al. 2007) and are proposed to act in post-transcriptional regulation of hitherto unidentified target transcripts. As well as their pronounced circadian rhythm expression the vertebrate nocturnins are subject to clock-independent regulation implying additional and clock-independent functions in embryogenesis and/or metabolism. For example, Xenopus nocturnin is dynamically expressed from neurula stage onwards in various differentiating organs prior to the onset of the endogenous clock (Curran et al. 2008) and acute regulation of mouse nocturnin by physiological cues has been proposed. Moreover, nocturnin is an immediate early response gene of NIH3T3 fibroblast cells, characterized by its fast mRNA and protein turnovers (Garbarino-Pico et al. 2007).

Here we show, more than nine decades after the original description of the Drosophila gene curled, that the gene is identical to the fly ortholog of nocturnin. Uncovering the molecular identity of curled not only provides an entry point for the functional understanding of the prominent wing mutant phenotype, widely used as a marker in genetic studies, but also sets the stage for the analysis of the implications of fly nocturnin in circadian rhythm effector control and/or metabolism.

We show that Drosophila curled(nocturnin) has a highly complex and dynamic ontogenetic expression pattern and that the gene is acutely regulated upon physiological challenge. The Curled protein features all amino acids essential for catalytic function of CCR4 proteins and is localized in the cytoplasm, consistent with a possible function in mRNA decay via deadenylation as reported for yeast and vertebrates. We demonstrate that curled(nocturnin) is necessary during a narrow time window at late pupal stage for proper wing morphogenesis in adult flies and that this requirement is not tissue autonomous. Our results suggest that timely post-transcriptional regulation of effector genes is essential for proper wing formation during the wing expansion phase early after the eclosion of flies. Thus the curled mutant wing phenotype presents the first example of a morphogenetic function for a nocturnin gene family member that acts in the context of the long described Drosophila curled wing marker genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly techniques:

Flies were propagated at 25° on a complex corn flour-soy flour-molasses medium as described (Grönke et al. 2005). Fly strains used are showed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Fly strains

| Name (stock number) | Genotype | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| tubulin-GAL4 (RKF1057) | w*; P{w+mC=tubP-GAL4}LL7/TM3, P{w+mC=ActGFP}JMR2, Ser1 | BDSC no. 5138 (rebalanced) |

| Df(3R)M86D (RKF1063) | Df(3R)M86D, Dfd[1] p[p]/TM3, Ser[1] | BDSC no. 1714 |

| FB+SNS GAL4 (RKF125) | w*; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}FB+SNS | Grönke et al. (2003) |

| cu(no)GE22476 (SGF706) | w*; P{w+mC=EP}noGE22476 renamed to w*; P{w+mC=EP}cuGE22476 | GenExel |

| no1 or cu3 (SGF707) | w*; no1 renamed to w*; cu3 | This study |

| no2 or cu4 (SGF708) | w*; no2 renamed to w*; cu4 | This study |

| no3 or cu5 (SGF709) | w*; no3 renamed to w*; cu5 | This study |

| noGE22476rv or cuGE22476rv (SGF710) | w*; noGE22476rv renamed to w*; cuGE22476rv | This study |

| cu(no)+12.2; cu3(no1) (SGF713) | w*; P{w+mC=CaSpeR4 cu(no)+12.2}#43a/+; cu3(no1) | This study |

| no(cu)stop12.2; cu3(no1) (RKF1067) | w*; P{w+mC=CaSpeR4 nostop12.2}#20a; cu3(no1) | This study |

| UAS-cu(no)-RC:EGFP (SGF811) | w*; P{w+mC curled(nocturnin)[Scer\UAS]=UAS-cu(no)-RC:EGFP}#103/CyO float | This study |

| UAS-cu(no)-RC:EGFP; cu3(no1) (RKF1087) | w*; P{w+mC curled(nocturnin)[Scer\UAS]=UAS-cu(no)-RC:EGFP}#103; cu3(no1) | This study |

| UAS-cu(no)-RE:EGFP (SGF813) | w*; P{w+mC curled(nocturnin)[Scer\UAS]=UAS-cu(no)-RC:EGFP}#30/CyO float | This study |

| UAS-cu(no)-RE:EGFP; cu3(no1) (RKF1085) | w*; P{w+mC curled(nocturnin)[Scer\UAS]=UAS-cu(no)-RC:EGFP}#30; cu3(no1) | This study |

| cu1 (RKF1061) | cu1 | BDSC no. 468 |

| cu1/TM3, Sb1 | ru1, pbl5, h1, th1, st1, cu1, sr1, es ca1/TM3, Sb1 | BDSC no. 2452 |

| TM6C, cu1 | ash1, B1/TM6C, cu1, Sb1, ca1 | BDSC no. 5045 |

| cu2/cu1 (RKF1062) | In(3L)A54, st1 cu2 pp red1 e4/TM6C, cu1 Sb1 Tb1 | BDSC no. 6591 |

| Lsp2-GAL4 (RKF491) | y1,w1118; P{Lsp2-GAL4.H}3 | BDSC no. 6357 |

| UAS-cu(no) dsRNA | w1118; P{GD8898}v45442 | Dietzl et al. (2007) |

| hs-GAL4 (GÖ432) | P{GAL4hs.2sevryp+t7.2=GAL4-Hsp70.sev}K25 (on 3rd) | Ruberte et al. (1995) |

| w1118 | w1118 | This study |

For additional strains see Table 3.

Heat-shock-induced cu(no) in vivo knockdown was induced by exposing the F1 progeny of the cross hs-GAL4 × UAS-cu(no) dsRNA (raised at 25°) for 20 min to 37° at the indicated time points/developmental stages. Identically treated F1 progeny of w1118 × UAS-cu(no) dsRNA flies were used as controls.

Generation of nocturnin mutants:

w*; P{w+mC=EP}no(cu)GE22476 flies that carry an EP transposon-construct integration in the 5′ upstream region of the nocturnin gene at chromosome 3R between positions 7025884/5 (FlyBase D. melanogaster Genome Release 5.17), corresponding to position −2956 relative to the putative no(cu) start ATG in no(cu)-RD exon 1, were obtained from GenExel (Korea). No(cu) deletion mutants were generated by a conventional P-element mobilization scheme resulting in the small no3 deletion (class I event) and the two larger deletions no1 and no2 (class II events) as well as the precise excision allele noGE22476rv, which serves as a genetically matched background control. Sequencing of the relevant part of the no(cu) gene showed that no3 and no2 deletion mutants lack genomic DNA sequences from 3R: 7.025.888–7.027.112 and 7.025.888–7.032.973, respectively, corresponding to position (pos.) −2953 to −1729 and −2953 to +4132 relative to the putative no(cu) start ATG in no(cu)-RD exon 1. No1 contains residual P-element sequence, which impeded the molecular characterization at the sequence level, but PCR analysis mapped the 3′ breakpoint between no(cu)-RC exon 1 and exon 6 (Figure 1A).

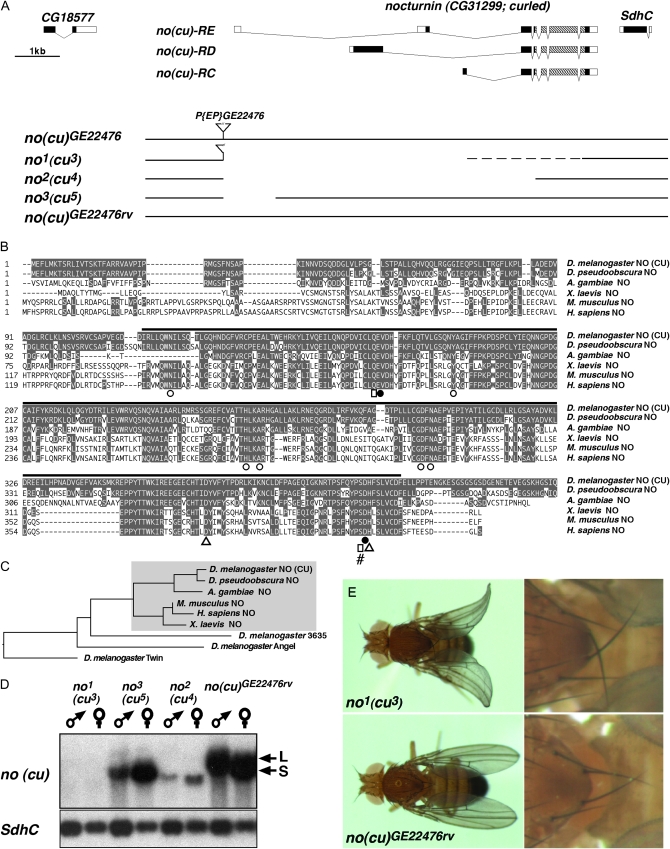

Figure 1.—

The Drosophila nocturnin (curled) gene: gene locus organization, deletion mutants, and phylogeny of Nocturnin proteins. (A) Organization of nocturnin (curled) gene locus with transcript isoforms no(cu)-RC, no(cu)-RD, and no(cu)-RE relative to the flanking genes CG18577 and SdhC at 86D7 on chromosome 3R. [Note: Coding parts of exons are marked by black, noncoding parts by white boxes; hatched boxes, Mg2+-dependent endonuclease-like domain (pfam03372); no(cu)-RC, -RD, -RE are the only no(cu) transcripts annotated in FlyBase r5.17.] Transposon integration line P{EP}no(cu)GE22476 was used to generate nocturnin (curled) deletion mutants no1 (cu3), no2 (cu4), and no3 (cu5) as well as genetically matched no+ (cu+) control line no(cu)GE22476rv. (B) Sequence alignment of vertebrate und invertebrate Nocturnin (NO) protein family members proves strong evolutionary conservation of amino acids involved in the catalytic function of yCCR4-related family proteins (amino acids identical to D. melanogaster NO are shaded in gray). Residues essential for the Mg2+-dependent endonuclease-like domain function are indicated as in Dupressoir et al. (2001): ▵, catalytic residue; □, residues involved in orientation and stabilization of catalytic residues; ○, for phosphate binding, and •, for Mg2+ binding residues; #, position of stop in nostop12.2. The black bar illustrates the extent of the pfam03372 domain. (C) Phylogenetic tree analysis showing that Drosophila NO(CU) is the Nocturnin ortholog (Nocturnin subfamily shaded gray) among the four yCCR4-related proteins of the fly. (D) Northern blot analysis of adult flies shows nocturnin (curled) small S and large L transcript populations in no(cu)GE22476rv controls and identifies no1 (cu3) as transcript null mutation. No3 (cu5) specifically lacks no(cu) L transcripts, while no2 (cu4) expresses a low abundance transcript slightly shorter than the no(cu) S transcript of control flies. SdhC transcript is unaffected in all no(cu) mutants. (E) Distally upward bent wing (left panel) and proximally crossed posterior scutellar bristle (right panel) phenotypes of no1 (cu3) mutants compared to no(cu)GE22476rv controls.

Fecundity assay and imaginal hatching rate:

cu3(no1) and cu4(no2) mutants were crossed into a w1118 mutant background for five generations and reestablished as homozygous stocks. Embryos of the appropriate parental mutant and control genotypes (see Figure S1, A) were collected and mixed embryo collections were seeded in propagation vials to ensure identical propagation conditions. After hatching virgin females and males of the respective mutant or control genotypes were batch mated 1–2 days after hatching for 27 hr. Single females were then housed with 1–2 males and daily transferred to new food vials. Progeny were counted as embryos; the developmental speed was monitored and empty pupal cases counted to assess the percentage of imaginal hatching. For quantitative analysis females producing no progeny or not surviving the full observation period were excluded. Progeny values of all other females of a given genotype were averaged and the standard deviation calculated.

Molecular biology:

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Name (stock number) | Sequence | Restriction site/comment |

|---|---|---|

| SGO163 | TGCCCTGTGAGAAGTGTAGA | |

| SGO209 | GGGGCGTCTAATGTTATG | |

| SGO363 | GGTAGATCTTAAAAGTGACAATGGATC | BglII |

| SGO364 | CCTTAGATCTTGCCGCAGACATGGAG | BglII |

| SGO365 | GCACAAAAAGATCTAAATGGAGTTTC | BglII |

| SGO366 | TCGGCAAATTAGGTACCTGAAGCTTT | KpnI |

| SGO367 | TGGTCGACTGTATTGAATGGATCCATGCTTG | SalI |

| SGO374 | GTCATTGGCATTGTTATCAG | |

| SGO375 | CCGAGGTGGCGTCTAATC | |

| SGO390 | TCAGATCTCCAGAGCATTTGAACCGC | |

| SGO391 | GCGGCTCGAACTCAAACTC | |

| SGO405 | TGAACTGAATCCCCCATCTAA | |

| SGO406 | GTTTGTTGTGTTACGCAATCC | |

| SGO418 | CAGTCAGTGTACGGTCCCA | |

| SGO419 | AATGTAATAGGTTTAGCTGGGG | |

| SGO451 | GTGCGGCCGCAGCCTTACACGAATGTCG | NotI |

| SGO452 | ATGGTACCTGTTGCTTTGGGCGTGCTGC | KpnI |

| SGO453 | GGTGACTCGAGGTTTATAGG | XhoI |

| SGO454 | CCTATAAACCTCGAGTCACC | XhoI |

| SGO455 | CAGATCAAAAACTGTCTAGACT | XbaI |

| SGO456 | CCAATATCCATAGGATCACTTTTC | Mutation in bold |

| SGO457 | GAAAAGTGATCCTATGGATATTGG | Mutation in bold |

| RKO681 | GCGAAGAGGGCGAGGAATGTCA | |

| RKO682 | TGGGTGTGCGATTCTTGCCAA | |

| RKO692 | CGATATGCTAAGCTGTCGCACA | |

| RKO693 | CGCTTGTTCGATCCGTAACC |

cDNA isolation and transgene cloning:

cu(no) and SdhC cDNAs were PCR amplified from an embryonic (0–22 hr) Drosophila Oregon R cDNA library. cu(no)-RD (pos. 75–2024 of NM_001104276.1) encoding full-length CU(NO)-PD was amplified using SGO363/SGO366 and cloned into pCRII-TOPO (www.invitrogen.com) resulting in pCRII-TOPO cu(no)-RD (SG261). Cu(no)-RC (pos. 1–1349 of NM_001104275; silent substitutions at pos. T411C and G1257A) encoding full-length CU(NO)-PC was amplified using SGO364/SGO367 and cloned into pEGFP-N2 (www.clontech.com). The cu(no)-RC:EGFP fusion cassette of the resulting pEGFP-N2 cu(no)-RC:EGFP clone (SG264) was subcloned BglII/NotI into pUAST (Brand and Perrimon 1993) resulting in pUAST cu(no)-RC:EGFP (SG268). Using the same strategy, cu(no)-RE (pos. 339–1680 of NM_001104277.1) encoding full-length CU(NO)-PE was amplified using SGO365/SGO367, cloned into pEGFP-N2 (resulting in pEGFP-N2 cu(no)-RE:EGFP clone (SG265) and the cu(no)-RE:EGFP fusion cassette subcloned into pUAST resulting in pUAST cu(no)-RE:EGFP (SG269). SdhC cDNA (pos. 2–596 of NM_141790.2) was amplified using SGO418/SGO419 and cloned into pCRII-TOPO (www.invitrogen.com) resulting in pCRII-TOPO SdhC (SG283).

The no+12.2 genomic rescue construct was generated in a three-step cloning process. First two cu(no) genomic DNA fragments were PCR amplified using the primer pairs SGO451/SGO454 and SGO452/SGO453 and cloned into vector pBluescript II KS(+) (www.stratagene.com) using the restriction sites indicated above resulting in pBS II KS(+) cu(no) 4.6 (SG296) and pBS II KS(+) cu(no) 7.6 (SG300), respectively. Subsequently, the SG300 DNA insert was released by XhoI/KpnI restriction, cloned into equally restricted SG296, and the resulting 12.2-kbp genomic fragment subcloned via NotI/KpnI restriction into pCaSpeR4 vector (https://dgrc.cgb.indiana.edu) to generate pCaSpeR4 cu(no)+12.2 (SG301).

A C->A nonsense mutation at cu(no)-RE position 1545 in the inactivated genomic rescue construct cu(no)stop12.2 was introduced by PCR using primer pairs SGO455/SGO457 and SGO452/SGO456 on the SG300 template. The two resulting DNA fragments were mixed, used as PCR template with primers SGO455/SGO452 and the PCR product cloned via XbaI/KpnI to generate pBS II KS(+) cu(no)stop 7.6. The subsequent generation of pCaSpeR4 cu(no)stop12.2 (SG302) followed the strategy outlined for SG301. Introduction of the mutation was confirmed by sequencing. Transgenic fly strains were established by P-element-mediated germ-line transformation as described (Grönke et al. 2003).

Identification of curled mutations:

PCR-based cu gene locus analysis was performed with the following primer combinations (see Figure 2B): Amplicon a, SGO374/SGO375; amplicon b, SGO363/SGO391; and amplicon c, SGO405/SGO406. Control amplicon d was amplified from the brummer gene locus using SGO163/SGO209. Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) fly strains no. 2452, no. 5045 (for cu1 allele), and no. 6591 (for cu2 allele) were crossed to transcript null no1(cu3) mutant flies. Nocturnin(curled) cDNAs of transheterozygous cu1/no1(cu3) or cu2/no1(cu3) flies were isolated as above using the primer pair SGO390/SGO366, cloned into the pCRII-TOPO vector (www.invitrogen.com) and sequenced. Cu(no) mutations detected in the cu1 allele of both cu1 mutant fly lines or in differently sized cDNAs from cu2/no1(cu3) flies were confirmed by PCR amplification and sequencing of the corresponding genomic DNA sequence.

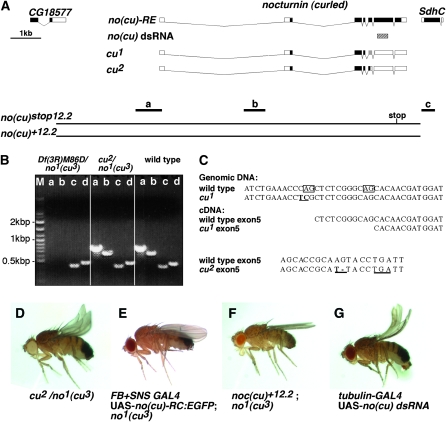

Figure 2.—

curled is nocturnin. (A) Schematic overview of molecular lesions in the cu1 and cu2 alleles at the nocturnin/curled gene locus. Boxes represent noncoding (open), coding (black), or miscoding (shaded) exons with the exception of the hatched box [cu(no) dsRNA] representing the cu(no) coding region targeted by a transgenic dsRNA snapback construct. Extent of genomic cu(no) rescue constructs without [cu(no)+12.2] and with [cu(no)stop12.2] stop mutation in a functional essential region of Nocturnin. Bars labeled with a, b, and c indicate position and extent of PCR amplicons used in B. (Note: Bar d, control amplicon from the brummer locus; M, DNA molecular size marker.) PCR-based genotyping in B confirms coverage of no1 (cu3) by Df(3R)M86D and genomic integrity of SdhC in no1 (cu3) mutants. No gross cu(no) locus aberrations in the cu2 mutant allele. (C) cu(no) splice site mutation in cu1 and frameshift mutation in cu2. The no1 (cu3) mutant wing phenotype is not complemented by cu2 (D), and can be rescued by tissue-specific cu(no) cDNA (E), or cu(no)+12.2 genomic (F) transgene expression. (G) cu(no) mutant phenocopy by ubiquitous expression of a cu(no) dsRNA transgene.

Northern blot and qRT–PCR:

Total RNA for qRT–PCR analysis was prepared using peqGOLD TriFast reagent (www.peqlab.de) and reverse transcribed using the QIAGEN QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (www.qiagen.com). Real-time PCR analysis was performed on an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus System using Applied Biosystems Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (www.appliedbiosystems.com) with the following primer pairs: cu(no), RKO681/RKO682 and RpL32, RKO692/RKO693. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and experiments were repeated twice. Details are available on request.

Developmental Northern blot and quantitative Northern blot analysis were done as described (Grönke et al. 2003, 2005). In brief, Northern blots were prepared using the Northern Max kit (www.ambion.com) with 2 μg poly-A+ mRNA per lane for developmental and 10 μg total RNA per lane for quantitative expression analysis, respectively. Blots were successively hybridized with radioactively labeled cu(no) and SdhC antisense RNA probes using the Strip-EZ RNA kit (www.ambion.com). The universal cu(no) probe, detecting all annotated transcript isoforms, was generated by in vitro transcription of NotI linearized pCRII-TOPO cu(no)-RD (SG261), the SdhC probe of NotI linearized pCRII-TOPO SdhC (SG283) using Sp6 RNA polymerase. For quantification hybridized blots were scanned with a PhosphoImager (Fujifilm BAS; www.fujifilm.com) and signal intensity was quantified using AIDA Image Analyzer software v2.11 (www.raytest.de).

In silico methods:

Insect Nocturnin (Curled) homologs from D. pseudoobscura and Anopheles gambiae were identified in a tBlastN homology search (www.flybase.org) with D. melanogaster CU-PE and subsequently hand assembled. The deduced protein sequences were aligned with D. melanogaster CU-PE (ABW08641), the vertebrate Nocturnin homologs from X. laevis (AAB39495), Mus musculus (AAG01384), and Homo sapiens (Q9UK39) using the ClustalW algorithm of MEG-ALIGN (www.dnastar.com) to generate the Nocturnin protein alignment. The same alignment including in addition the D. melanogaster Twin (CG31137-PA, ACL89247), D. melanogaster Angel-PA (AAF47045), and D. melanogaster 3635 proteins (CG31759-PC, AAN10808) was used to generate the phylogenetic tree.

Imaging:

In situ hybridization on embryos and third instar larval tissue using a digoxigenin-labeled RNA antisense probe was done as described (Grönke et al. 2003). The cu antisense probe was generated by in vitro transcription on NotI linearized pCRII-TOPO cu-RD (SG261) using Sp6 RNA polymerase (www.fermentas.com) and the DIG RNA labeling kit (www.roche-applied-science.com).

Wing and bristle phenotypes of anesthetized adult flies at days 4–6 posteclosion were imaged using a Zeiss Discovery V8 stereomicroscope equipped with a Qimaging Micropublisher 5.0 RTV camera. The same setup was used to record the early posteclosion wing expansion phase of w1118;cu3/cu4 (File S1) and w1118 (File S2) flies.

For ex vivo EGFP fluorescence detection fat body tissue of third instar larval progeny of the cross Lsp-2-GAL4 × UAS-no-RC:EGFP was hand dissected, embedded in phosphate-buffered saline, and imaged within 1 hr after preparation using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope using 488 nm excitation and 500–541 nm emission wavelengths or transmission mode.

RESULTS

Molecular organization of the Drosophila nocturnin gene and generation of nocturnin mutants:

In a screen for starvation-responsive genes in adult flies (Grönke et al. 2005), we identified Drosophila nocturnin (no) which was previously characterized as bona fide ortholog of the mammalian nocturnin genes by sequence alignment (Dupressoir et al. 2001). The no gene locus maps genetically at 86D7 on the third chromosome (genomic sequence annotation 3R 7.026.138–7.034.357) (Tweedie et al. 2009). It codes for three predicted no transcript isoforms (no-RC, no-RD, and no-RE) (Tweedie et al. 2009; see also Figure 1A) the existence of which was confirmed by cDNA isolation and sequencing. Conceptual translation of the no transcript isoforms predicts three different no proteins (NO), NO-PC, NO-PD, and NO-PE, which share a C-terminal Mg2+-dependent endonuclease-like domain (pfam03372; NO-PE amino acids 115–411; Figure 1, A and B; see also Dupressoir et al. 2001) encoded by the common last five exons. Protein sequence alignment of D. melanogaster NO-PE to the other three fly yCCR4-related proteins called Twin, Angel, and 3635 as well as to Nocturnin proteins of other insects (D. pseudoobscura, An. gambiae) and of nonmammalian (X. laevis) as well as of mammalian vertebrates (M. musculus, H. sapiens) proves that NO is the bona fide Nocturnin ortholog of the fly (Figure 1, B and C and Dupressoir et al. 2001). Moreover it reveals remarkably high sequence conservation between Nocturnin proteins in particular in the putative Mg2+-dependent endonuclease-like domain (between 53 and 89% sequence identity; Figure 1B). Notably all amino acids, which have been implicated in the domain's catalytic function, are completely sequence conserved. These findings suggest that Drosophila NO is a putative mRNA deadenylase involved in post-transcriptional regulation of target genes (see Figure 1B). Thus all three predicted Drosophila NO protein isoforms are likely to exert mRNA deadenylase function as reported for various yCCR4-related family proteins (Chen et al. 2002; Baggs and Green 2003; Morris et al. 2005).

To analyze no function in vivo we generated no deletion mutants by imprecise P-element excision of the P{EP}GE22476 transgene construct, which is integrated immediately upstream of the no transcribed region (Figure 1A). Starting from the noGE22476 fly strain the no alleles no1, no2, and no3 were isolated. They carry no deletions of different extent (see materials and methods). We also recovered the precise excision revertant noGE22476rv, which served as a genetically matched control. No transcript expression in the deletion mutants was examined by Northern blot analysis (Figure 1D). Control flies express two prominent no transcript sizes of ∼1.8 kb and 2.0 kb, referred to as S and L, respectively. The size of the annotated no transcripts (Figure 1A) suggests that the S band might correspond to no-RC (1529 bp) and no-RE (1856 bp), whereas the L band might correspond to no-RD (2194 bp). In no1 flies no S and L transcripts are absent, confirming that this mutation is indeed a transcript null allele. No2 mutants only express a low abundant no transcript, which is slightly smaller than the no S transcript of control animals. No3 mutant flies exclusively express no S transcripts. None of the no deletions affect the expression of the no downstream neighboring gene SdhC supporting the specificity of the no alleles (Figure 1D).

Homozygous flies carrying any of the three no deletions are viable and fertile. Whereas the wings of no3 mutant flies appear normal both the no1 and no2 mutants show a phenotype identical to curled (cu) mutants i.e., upward bent (curled) wings and proximally crossed posterior scutellar bristles (Figure 1E). Since the cu gene has been genetically mapped to 86D3–86D4 (Tweedie et al. 2009), a chromosomal region very close to no at 86D7, we asked whether no and cu mutations could be alleles of the same gene.

nocturnin is curled:

To establish whether cu and no mutations affect the same gene, we performed a number of experiments that demonstrate that the curled wing phenotype of no mutants is caused by an inactivation of no and that the nocturnin gene is indeed encoded by the curled gene locus. Molecular data indicate that the no1 deletion is encompassed by deficiency Df(3R)M86D (Figure 2B), which genetically does not complement the curled wing phenotype of no1 nor of the cu1 or cu2 mutants (data not shown). Furthermore, no1, cu1, and cu2 failed to complement each other (Figure 2D; and data not shown). Moreover, the wing phenotype of homozygous no1 mutants can be completely reverted to wild type by the targeted expression of a NO-PC:EGFP or a NO-PE:EGFP fusion protein (Figure 2E and data not shown). Finally, the mutant phenotype of homozygous no1 flies as well as of transheterozygous no1/cu1 mutant flies can be reverted by a 12.2-kbp genomic rescue transgene, termed no+12.2, which spans the no gene locus (Figure 2, A and F, and data not shown).

The importance of the putative catalytic domain of NO is highlighted by the fact that a no+12.2- derived control transgene termed nostop12.2 fails to rescue the wing phenotype. This nostop12.2 transgene carries a premature stop codon after amino acid position 401 of the NO-PE open reading frame resulting in a truncated NO protein that lacks part of the predicted endonuclease domain (Figures 1A and 2A) including evolutionarily conserved and functionally important amino acid residues essential for nocturnin protein function (Figure 1B). Taken together, these results unambiguously establish that a deletion of the no gene causes a curled wing phenotype and that the endonuclease domain is important for no gene function.

Molecular analysis of cu2/no1 transheterozygotes detected no gross molecular lesion of the X-ray induced cu2 allele (Figure 2B). However, genomic and cDNA sequence analysis revealed that no transcripts are indeed affected in cu1 and cu2 mutants. Cu1 mutants carry a splice acceptor site mutation at no-RE exon 5, which causes an alternative splice site usage. This leads to an 11-bp deletion followed by both a frameshift in the open reading frame and a premature translational stop signal (Figure 2, A and C). Similarly, cu2 mutants carry a base pair substitution followed by a single-base-pair deletion at positions 67/68 of the no-RE exon 5, which cause a premature translational stop at amino acid position 147 of NO-PE (Figure 2, A and C). Accordingly, the NO open reading frame of the two independently generated cu mutant alleles lack the conserved endonuclease domain. Thus, cu1 and cu2 appear to be loss-of-function alleles.

Thus, we provide ample evidence that nocturnin is identical to the previously described gene curled for which reason the latter name will be maintained. Therefore, we refer in the following text to no1, no2, and no3 mutant alleles as cu3, cu4, and cu5, respectively, to the transgene bearing flies described above as cu+12.2 and custop12.2 and finally to the EGFP containing fusion transgenes as UAS-cu-RC:EGFP and UAS-cu-RE:EGFP, respectively.

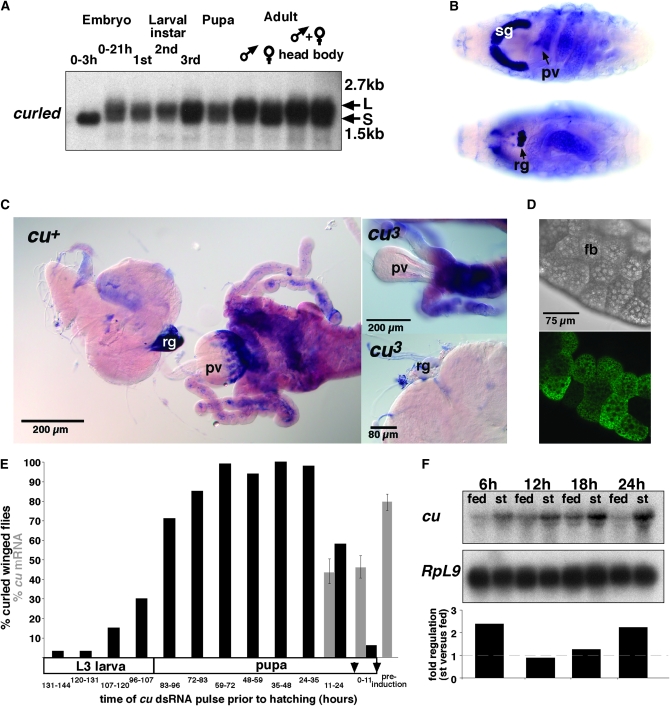

curled developmental expression and its relation to wing morphogenesis:

As observed with its vertebrate orthologs (Dupressoir et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2001; Curran et al. 2008) the Drosophila gene cu displays a complex expression pattern. Developmental Northern blot analysis revealed cu expression during all ontogenetic stages from early embryos to adult flies. The small cu transcript S observed during early embryogenesis is maternally provided. In all other stages of the Drosophila life cycle both the S and the L transcripts are expressed (Figure 3A). In situ hybridization detects strong cu transcript enrichment in embryonic salivary glands, the distal part of the proventriculus (posterior to the later imaginal ring region) and the ring gland as well as weak expression in the midgut (Figure 3B). The proventricular and ring gland cu expression domains are also found at third instar larval stage (Figure 3C). Cu transcript could not be detected by in situ hybridization in the larval central brain, in the imaginal discs, the salivary glands, or in the fat body (Figure 3C and data not shown). The latter result is in line with the absence of cu cDNAs in a larval fat body EST library (Jiang et al. 2005). However, microarray experiments detect weak cu expression in this organ (Chintapalli et al. 2007), which suggests low abundance cu expression in the fat body at the detection limit. Furthermore, cu expression shows neither gender specificity nor differences between head and body in adult flies (Figure 3A). Tissue-targeted in vivo expression of a functional CU-PC:EGFP fusion protein in larval fat body cells indicates that the protein is homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm (Figure 3D) as has been reported for endogenous Nocturnin protein in Xenopus retinal photoreceptor cells (Baggs and Green 2003).

Figure 3.—

Complex and dynamic curled developmental gene expression and pupal function for wing morphogenesis. (A) Developmental Northern blot analysis detects curled S (±1.8 kb) and L (± 2.0 kb) transcript populations at all ontogenetic stages with the exception of early embryos, exclusively expressing maternally contributed cu S transcripts. (B and C) Tissue-specific expression of cu transcripts in embryos and third instar larvae. Expression in embryonic salivary glands (B) and in embryonic (B) and third instar larval (C) proventriculus and ring gland absent from cu3 deletion mutants. (D) Cytoplasmic intracellular CU-PC:EGFP localization upon targeted expression in third instar larval fat body. (Note exclusion from lipid droplets.) (E) Phenocritical period of curled wing morphogenesis function in pupae determined by in vivo RNAi. Percentage of curled winged phenotypes (black columns) and cu transcript expression levels (gray columns) scored in flies subjected to developmental time-controlled ubiquitous cu gene knockdown pulses during third instar larval and pupal development. Note: Arrows exemplify time points of heat-shock-mediated cu knockdown induction and error bars 95% confidence intervals. (F) Quantitative Northern blot analysis demonstrates starvation-responsive transcriptional upregulation of cu in adult male flies. sg, salivary gland; pv, proventriculus; rg, ring gland; st, starved.

Collectively, the cu gene is expressed during all stages of the Drosophila life cycle, and transcripts are enriched in metabolically active tissues such as the ring gland, salivary gland, and the proventriculus. This expression profile of cu argues for specific developmental and/or metabolic functions of the CU protein. However, neither the reduction of cu gene function by a ubiquitous RNAi-mediated gene knockdown (see below) nor lack of the cu gene impairs the fecundity of adult flies (Figure S1, A). Additionally, cu mutants show a normal survival rate and developmental time during ontogenesis from embryos to adult flies (Figure S1, B; and data not shown). Thus, reduction or lack of cu function reveals no developmental role of the endogenous cu expression other than in adult wing morphogenesis. Notably, however, ectopic expression of the CU-PC:EGFP fusion protein under ubiquitous driver control causes lethality at pupal stage (data not shown). This result suggests that control of cu expression dosage is critical for normal fly development.

Upwardly bent, curled wings are the most prominent phenotype of mutant flies carrying a cu gene deletion or lacking an intact CU C-terminal endonuclease domain. Accordingly, it was surprising to find that the cu gene is not expressed during any stage of wing development. The discrepancy between the cu gene expression domains and the specific cu mutant wing phenotype argues therefore against a tissue-autonomous mode of cu gene action. To test this hypothesis we took advantage of tissue-specific in vivo gene knockdown in response to a UAS-cu(no) dsRNA transgene that was controlled by a variety of different GAL4 drivers using the GAL4/UAS system (Brand and Perrimon 1993). Ubiquitous cu knockdown forced by different driver constructs phenocopies the cu mutant wing phenotype (Figure 2G; and Table 3), whereas expression of the UAS-cu(no) dsRNA effector transgene in wing imaginal discs had no impact on wing morphogenesis (Table 3, Figure S1, E). Interestingly, cu knockdown in various different individual organs such as the nervous system, ring gland, muscles, fat body, tracheal system, salivary gland, and gut including each of the various endogenous cu expression domains was also insufficient to interfere with normal wing development (Table 3). These data suggest that the cu gene acts in a nonautonomous manner and that the endogenous expression domains of the gene have possibly redundant functions in providing cu activity. This conclusion gains further support by the finding that CU-PC:EGFP expression targeted to the fat body and the stomatogastric nervous system of cu mutants can fully rescue the wing phenotype (Figure 2E; note the absence of wing expression shown in Figure S1, D), whereas the cu knockdown by UAS-cu(no) dsRNA effector transgene expression in the same spatiotemporal expression patterns does not interfere with normal wing development (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Tissue-specificity analysis suggests a systemic cu function for wing morphogenesis

| Conditional curled knockdown causing curled wing phenotype | ||

|---|---|---|

| Driver line genotype: | Driver line tissue specificity: | No. of F1 scored: |

| w*; P{w+mC=tubP-GAL4}LL7/TM3, P{w+mC=ActGFP}JMR2, Ser1 (1m) | Ubiquitous | >100 |

| y1 w*; P{w+mC=Act5C-GAL4}25FO1 / CyO, P{w+mC=ActGFP}JMR1 (1m) | Ubiquitous | >100 |

| w*; da-GAL4 | Ubiquitous | 112a |

| Conditional curled knockdown causing no curled wing phenotype | ||

| Driver line genotype: | Driver line tissue specificity: | No. of F1 scored: |

| w*; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}10c | Wing disc | 133 |

| w*; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}C-765d | Wing disc | 135 |

| P{w+m*=GAL4}A9, w*b | Wing disc | >100 |

| w*; P{GAL4-vg.M}2; TM2/TM6B, Tb1 b | Wing disc | 81 |

| w1118 P{GawB-DeltaKE}BxMS1096-KE b | Wing disc | 60 |

| w*; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}30A/CyOm | Wing disc, eye-antennal disc, salivary gland | 37 |

| yawa; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}FB P{w+m*UAS-GFP 1010T2}; +/+e | Fat body, salivary gland | >100 |

| w*; 3.1Lsp2-Gal4 line 2/TM3, Sb *f | Fat body | 54 |

| y* w*; r4-gal4g | Fat body | 61 |

| w*; yolk-Gal4 (II)j | Female Fat body | 64 (females) |

| w*; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}FB+SNSe | Fat body, stomatogastric nervous system, salivary gland | >100 |

| w1118; P{w+mC=Sgs3-GAL4.PD}TP1b | Salivary gland | >100 |

| P{w+mW.hs=GawB}elavC155 b | Nervous system | 54 |

| P{w+mW.hs=GAL4-Nrv2-3} P{w+m*UAS-GFP}h | Nervous system | 55 |

| w1118; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}drlPGAL8 b | Primarily mushroom body and central body complexes | 27 |

| w*; Burs-Gal4i | Bursicon-positive neurons | 44 |

| y1 w*; P{w+mC=GAL4-per.BS}3b | period-positive neurons | 65 |

| w*; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}dimm929 b | Peptidergic neurons | 69 |

| w*; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}386Yb | Peptidergic neurons | 55 |

| y1 w*; P{w+mC=Ccap-GAL4.P}16b | CCAP-secreting cells of ventral ganglion and brain | 87 |

| P{w+mC=GAL4-Eh.2.4}C21b | Eclosion hormone-expressing neurons | 63 |

| w1118; P{w+mC=drm-GAL4.7.1}1.1/TM3, Sb1 b | Embryonic proventriculus, anterior midgut, posterior midgut, Malpighian tubules, and small intestine | 45 |

| w1118; P{w+mW.hs=GawB}l(2)C805C805/CyOb | Larva: ring gland, histoblasts, gut and Malpighian tubulesAdult: male accessory glands, testis sheath and cyst cells | 44 |

| w*; P{GAL4-btl.S}k | Tracheal system | >100 |

| P{GAL4-Mhc.W}MHC-82l | Muscles | >100 |

Ubiquitous but no tissue-specific cu knockdown causes the curled wing phenotype. All driver lines were crossed against the UAS-cu(no) dsRNA effector line.

expressivity low

BDSC, (1m) Modified BDSC stock

K. Basler laboratory

To determine the phenocritical period of cu requirement for normal wing development we performed cu knockdown experiments by ubiquitous UAS-cu(no) dsRNA expression pulses in response to a heat-shock-controlled GAL4 driver transgene. Ubiquitous cu knockdown at any ontogenetic stage prior to the third larval instar (L3) stage did not result in a curled wing phenotype (data not shown), whereas cu dsRNA expression pulses during mid and late L3 (96–120 hr preeclosion) caused curled wings in low penetrance (<30%; Figure 3E). A fully penetrant curled wing phenotype was obtained, however, when cu dsRNA pulses were expressed during the pupal stage. Remarkably, cu dsRNA expression as late as 11–24 hr prior to fly eclosion could still induce the curled wing phenotype in the majority of the individuals. Quantitative RT–PCR experiments indicate that the corresponding rapid phenotypic response correlates with a reduction of cu mRNA abundance by ∼50% (Figure 3E). These findings show that the pupal stage is the phenocritical period of the cu-dependent wing phenotype and that a rapid decrease of cu mRNA abundance at eclosion can cause the phenotype observed.

The cu mutant wing phenotype can be suppressed by larval crowding and/or in malfed larvae (Nozawa 1956a,b) likely caused by riboflavin shortage during larval stages (Pavelka and Jindrák 2001). We therefore asked whether cu mRNA abundance could also be acutely modulated by altered physiological cues such as food deprivation. To demonstrate such a principal effect on cu mRNA, the cu transcript abundance in starved adult flies was monitored by quantitative Northern blot analysis (Figure 3F). The results show that cu transcripts quickly accumulate upon food deprivation (2.5-fold after 6 hr) and that the gene is dynamically regulated during an extended starvation period (Figure 3F; see also microarray data in Grönke et al. 2005). (Note: This work refers to the previous nocturnin gene annotation CG4796; FlyBase ID FBgn0037872.)

Thus, in agreement with previous studies concerning the modulation of the cu wing phenotype in response to environmental factors, cu transcript abundance is strongly affected by food deprivation.

Is curled involved in bursicon-controlled posteclosion behavior?

Both aspects of the cu mutant phenotype, i.e., the posterior upwardly bent wings as well as the misorientation of the posterior scutellar bristle, become manifest at expansion phase early after eclosion of the adult fly (File S1). During that stage, flies' behavior follows a stereotypical though environmentally modulated complex motor pattern (Fraenkel et al. 1984). The immediate posteclosion behavior is composed of two active motor phases (Baker and Truman 2002) called perch selection phase [phase I according to Peabody et al. (2009)] and expansion phase (phase III), which are separated by a largely sedentary interphase (phase II). The expansion phase is initiated by abdominal elongation and flexion of the body and eventually leads to wing and cuticle expansion (File S2). This stereotyped posteclosion behavior is coordinated by the neuropeptide bursicon (reviewed in Honegger et al. 2008), which is released into the hemolymph by a subset of NCCAP neurons during posteclosion phase II (Luan et al. 2006; Peabody et al. 2008, 2009). Bursicon controls the phase III behavior but it also has somatic functions including cuticle tanning (Baker and Truman 2002; Dai et al. 2008) and in transient cuticle plasticization allowing for body and wing expansions (Reynolds 1976, 1977).

cu mutants show a normal phase I–III posteclosion behavior sequence suggesting that cu gene function is unlikely to be involved in the behavioral output of bursicon (burs) activity at the level of NCCAP neurons. This conclusion is supported by the finding that cu knockdown in bursicon-positive NCCAP neurons does not interfere with normal wing morphogenesis (Table 3). Moreover cu mutants tan properly (Figure S1, C and D). This observation argues against a putative cu function in burs-mediated body pigmentation. However, the fact that both aspects of the cu mutant phenotype become manifest during the bursicon-controlled phase III of posteclosion behavior still leaves the possibility that the requirements for both, the burs and the cu genes or their effectors are interconnected. Unfortunately, a direct comparison of the cu and burs mutant wing phenotype development is impossible since burs mutants fail to expand their wings (Dewey et al. 2004) and the details of the incomplete wing expansion sequence in flies subjected to activity modulation of bursicon-releasing NCCAP neurons have not been reported (Luan et al. 2006). Thus, it is undecided whether the partially expanded wing development of those mutant flies follows the wild-type sequence, transiently adapting a downwardly cupped wing shape (Peabody et al. 2009) or whether the expanding wings bend up immediately as observed in cu mutants (compare File S1 and File S2). However, it is noteworthy that the posterior scutellar bristle reorientation, which is likely a consequence of thoracic cuticle expansion, fails not only in cu mutants but also in flies carrying the bursZ1091 or the bursZ1091/bursZ5569 mutant alleles (Dewey et al. 2004). Accordingly, a model proposing that cu affects a somatic output of burs signaling which in turn causes structural or physiological changes in wing and thoracic cuticle plasticity cannot be excluded. In accordance with this model we found that cu acts neither cell autonomously in the wing tissue nor in an organ-specific manner since wing- or organ-specific cu knockdown failed to cause a curled wing phenotype (see above and Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Here we provide evidence that the Drosophila gene cu, initially discovered >90 years ago by Thomas H. Morgan (Bridges and Morgan 1923), encodes the fly ortholog of vertebrate Nocturnin. The proposal that cu encodes a deadenylase as described for Nocturnin is based on strong circumstantial evidence. In vertebrates as well as in Drosophila all four yCCR4-related protein subfamilies, which are named for CCR4, nocturnin, 3635, and Angel are each represented by a single ortholog of high sequence conservation (Dupressoir et al. 2001). CCR4 subfamily members from yeast to mammals including the fly CCR4 ortholog Twin have been demonstrated or proposed to act as the catalytic component of the cytoplasmic deadenylase, which exerts 3′–5′ poly(A) RNA exonuclease activity (Chen et al. 2002; Temme et al. 2004). Similarly, in vitro poly(A)-tail-specific exonuclease activity involved in deadenylation has been shown for both Xenopus and mouse Nocturnin (Baggs and Green 2003; Garbarino-Pico et al. 2007). Moreover, all catalytic residues critical for CCR4 enzymatic function are absolutely sequence conserved in Curled (Figure 1B; see also Dupressoir et al. 2001). Consistent with its putative function in post-transcriptional mRNA control the EGFP-tagged CU is cytoplasmatically localized (Figure 3D) as has been observed for endogenous Xenopus Nocturnin (Baggs and Green 2003), a yeast Ccr4p–GFP fusion protein (Sheth and Parker 2003), the endogenous Drosophila CCR4 (Temme et al. 2004), an HA-tagged Drosophila CCR4 in nurse cells and blastoderm embryos (Lin et al. 2008), and a GFP-tagged hCcr4 in HEK293 cells (Cougot et al. 2004). These aspects of Drosophila Curled are in agreement with its proposed function in post-transcriptional control of target mRNAs via deadenylation.

Poly(A) tail removal is the first step in post-transcriptional gene repression followed by the decay of the corresponding mRNAs (reviewed in Meyer et al. 2004; Garbarino-Pico and Green 2007; Houseley and Tollervey 2009). Given the potent regulatory impact of deadenylases high selectivity of targeted mRNA species is required, possibly mediated by RNA-interacting proteins. To date no direct regulatory target mRNAs of any Nocturnin family protein is known but a yeast two-hybrid screen identified Quaking-related 58E-1 (Qkr58E-1) as an interaction partner of Nocturnin/Curled (Giot et al. 2003). This putative binding partner carries an RNA-binding K homology domain (Fyrberg et al. 1998) and thus may serve as mediator between Curled and specific target mRNAs.

The question of whether fly cu acts as a vertebrate nocturnin-like circadian cycling gene needs to be carefully addressed in future studies. Various genomewide microarray-based studies have not identified cu as a cycling gene (Claridge-Chang et al. 2001; McDonald and Rosbash 2001; Ceriani et al. 2002; Lin et al. 2002; Ueda et al. 2002) nor has a subsequent metaanalysis that was based on the data sets of the aforementioned studies (Keegan et al. 2007). However, these studies assessed global cycling patterns based on RNA extracted from total fly heads or bodies and likely would have missed circadian cycling of genes expressed in specific tissues/organs under peripheral clock control. In fact, adult cu expression has been reported not only in the brain but also in carcass preparations housing the adult abdominal fat body and oenocytes, which execute adipose-tissue and liver-like functions, respectively (Butterworth et al. 1965; Gutierrez et al. 2007), as well as in malpighian tubules, the fly kidneys (Chintapalli et al. 2007). Peripheral clocks have been reported to operate in all three of these metabolic nodal points (Giebultowicz and Hege 1997; Hege et al. 1997; Krupp et al. 2008; Xu et al. 2008). Accordingly, an evolutionarily conserved metabolic effector gene function of Drosophila cu is a possibility to be explored.

Although the circadian expression and function of vertebrate nocturnins is well studied, experimental data also suggest an additional, noncircadian role for these nocturnins. In mouse and Xenopus the nocturnin genes are already expressed during early embryogenesis (Wang et al. 2001; Curran et al. 2008). Interestingly, in frog nocturnin expression domains precede the onset of circadian rhythm expression of the clock gene Bmal1 (Curran et al. 2008), implying clock-independent nocturnin functions at this stage of development. Similarly, mouse nocturnin expression during embryogenesis has been reported (Wang et al. 2001) and Drosophila cu displays a complex tissue-specific embryonic expression pattern but their significance remains elusive since both nocturnin knockout mice and the cu mutant flies are viable and fertile and undergo apparently normal ontogenesis (Green et al. 2007) (Figure S1, A and E).

A selective, modulatory role of nocturnin would be consistent with the complex, though relatively subtle, metabolic phenotypes of knockout mice where phenotype and lipometabolism gene expression are nutritionally regulated (Green et al. 2007). The question remains open whether the primary cause of the mouse knockout phenotypes is the lack of circadian nocturnin expression in liver and/or other tissues. Alternatively or additionally the failure of a potential second regulatory aspect of nocturnin could contribute to the phenotypes. In fact, nocturnin is an immediate early gene when murine NIH3T3 fibroblast cells are exposed to phorbol ester or serum stimulation and both nocturnin mRNA and protein are characterized by a short turnover rate (Garbarino-Pico et al. 2007). Thus the gene is acutely regulated by physiological cues. Our findings that cu mRNA accumulates rapidly upon starvation of flies (Figure 3E) and that flies show a very sensitive phenotypic response to an acute cu downregulation (Figure 3D) would be in line with these results in mammalian cells. Furthermore, cu is downregulated in Drosophila Schneider (S2) cells depleted for the negative elongation factor (NELF), a transcription regulatory complex that affects rapidly inducible genes by stalling of RNA polymerase II (Gilchrist et al. 2008). Notably, the cu gene in S2 cells shows a promotor-proximal enrichment of NELF subunits, of the GAGA factor (Lee et al. 2008) and of RNA polymerase II (Muse et al. 2007) proposed to be characteristic for rapidly inducible stimulus-responsive genes (Gilchrist et al. 2008). Consistently, RNA polymerase II stalling at the cu promotor has been demonstrated in fly embryos (Zeitlinger et al. 2007). Taken together, the current data on cu regulation portray a gene subject to acute and dynamic regulation and thus it shows characteristics reminiscent of the noncircadian regulatory aspects of its mouse ortholog.

Besides showing that the curled wing phenotype of cu mutants is due to the loss of Drosophila nocturnin expression, our results highlight the possibility that mutants affecting a putative deadenylase involved in mRNA degradation can act in a non-cellautonomous manner during posteclosion morphogenesis. This mode of action is well established for hormones, like bursicon, which is produced in few endocrine cells of the fly, and systemically affects posteclosion morphogenesis as soon as it becomes available to all cells after its release into the hemolymph. But how can a putative enzyme that is located in the cytoplasm of cells outside the developing wing control proper wing morphogenesis? Taking all results presented in this study into account, we speculate that Drosophila Curled is required to degrade, among others, a specific mRNA which encodes a factor that prevents the synthesis or the conversion of a metabolic compound and/or its release into the hemolymph. In cu mutants this metabolic compound is either not synthesized or remains trapped in the cells that lack cu gene function and thus, it would not be available in target cells at the time when adult wing morphogenesis occurs. It appears that such a hypothetical compound can be supplied by many or all cells since the mutant wing phenotype can be only elicited by ubiquitous but not by tissue-specific cu gene knockdown. The disclosure of the molecular nature of such a compound and the question of whether and how such a component could interact with the activity of the bursicon pathway or whether it acts in parallel has to await the identification of first direct targets of Nocturnin proteins in vertebrates or Drosophila. The Drosophila cu mutant presents an ideal entry point for a genetic suppressor screen to identify such target genes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ralf Stanewsky and Carla Gentile for advice on qRT–PCR experiments and to Jake Jacobson for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Hans-Willi Honegger, Susan McNabb, and John Ewer for discussions on the bursicon mutant phenotypes. The Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, and Alf Herzig, Susan McNabb, and Benjamin White are acknowledged for fly strains. This study was supported by the Max Planck Society.

Supporting information is available online at: http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.105601/DC1.

References

- Baggs, J. E., and C. B. Green, 2003. Nocturnin, a deadenylase in Xenopus laevis retina: a mechanism for posttranscriptional control of circadian-related mRNA. Curr. Biol. 13: 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J. D., and J. W. Truman, 2002. Mutations in the Drosophila glycoprotein hormone receptor, rickets, eliminate neuropeptide-induced tanning and selectively block a stereotyped behavioral program. J. Exp. Biol. 205: 2555–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball, F., 1935. Mutants and abberations. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 3: 108. [Google Scholar]

- Barbot, W., M. Wasowicz, A. Dupressoir, C. Versaux-Botteri and T. Heidmann, 2002. A murine gene with circadian expression revealed by transposon insertion: self-sustained rhythmicity in the liver and the photoreceptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1576: 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bönisch, C., C. Temme, B. Moritz and E. Wahle, 2007. Degradation of hsp70 and other mRNAs in Drosophila via the 5′ 3′ pathway and its regulation by heat shock. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 21818–21828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A. H., and N. Perrimon, 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, C. B., and T. H. Morgan, 1923. The third-chromosome group of mutant characters of Drosophila melanogaster. Publs. Carnegie Instn. 327: 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, F. M., D. Bodenstein and R. C. King, 1965. Adipose tissue of Drosophila melanogaster I. an experimental study of larval fat body. J. Exp. Zool. 158: 141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceriani, M. F., J. B. Hogenesch, M. Yanovsky, S. H. Panda, M. Straume et al., 2002. Genome-wide expression analysis in Drosophila reveals genes controlling circadian behavior. J. Neurosci. 22: 9305–9319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Y. C. Chiang and C. L. Denis, 2002. CCR4, a 3′-5′ poly(A) RNA and ssDNA exonuclease, is the catalytic component of the cytoplasmic deadenylase. EMBO J. 21: 1414–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicoine, J., P. Benoit, C. Gamberi, M. Paliouras, M. Simonelig et al., 2007. Bicaudal-C recruits CCR4-NOT deadenylase to target mRNAs and regulates oogenesis, cytoskeletal organization, and its own expression. Dev. Cell 13: 691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli, V., J. Wang and J. Dow, 2007. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 39: 715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claridge-Chang, A., H. Wijnen, F. Naef, C. Boothroyd, N. Rajewsky et al., 2001. Circadian regulation of gene expression systems in the Drosophila head. Neuron 32: 657–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougot, N., S. Babajko and B. Séraphin, 2004. Cytoplasmic foci are sites of mRNA decay in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 165: 31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran, K. L., S. LaRue, B. Bronson, J. Solis, A. Trow et al., 2008. Circadian genes are expressed during early development in Xenopus laevis. PLoS ONE 3: e2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry, V., 1939. [New mutants report.] Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 12: 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L., E. M. Dewey, D. Zitnan, C. W. Luo, H. W. Honegger et al., 2008. Identification, developmental expression, and functions of bursicon in the tobacco hawkmoth, Manduca sexta. J. Comp. Neurol. 506: 759–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis, C. L., 1984. Identification of new genes involved in the regulation of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase II. Genetics 108: 833–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, E. M., S. L. McNabb, J. Ewer, G. R. Kuo, C. L. Takanishi et al., 2004. Identification of the gene encoding bursicon, an insect neuropeptide responsible for cuticle sclerotization and wing spreading. Curr. Biol. 14: 1208–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl, G., D. Chen, F. Schnorrer, K. C. Su, Y. Barinova et al., 2007. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 448: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir, A., W. Barbot, M. P. Loireau and T. Heidmann, 1999. Characterization of a mammalian gene related to the yeast CCR4 general transcription factor and revealed by transposon insertion. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 31068–31075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir, A., A. P. Morel, W. Barbot, M. P. Loireau, L. Corbo et al., 2001. Identification of four families of yCCR4- and Mg2+-dependent endonuclease-related proteins in higher eukaryotes, and characterization of orthologs of yCCR4 with a conserved leucine-rich repeat essential for hCAF1/hPOP2 binding. BMC Genomics 2: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, G., J. Su and J. Zdarek, 1984. Neuromuscular and hormonal control of post-eclosion processes in flies. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1: 345–366. [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg, C., J. Becker, P. Barthmaier, J. Mahaffey and E. Fyrberg, 1998. A family of Drosophila genes encoding quaking-related maxi-KH domains. Biochem. Genet. 36: 51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino-Pico, E., and C. B. Green, 2007. Posttranscriptional regulation of mammalian circadian clock output. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 72: 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino-Pico, E., S. Niu, M. D. Rollag, C. A. Strayer, J. C. Besharse et al., 2007. Immediate early response of the circadian polyA ribonuclease nocturnin to two extracellular stimuli. RNA 13: 745–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgel, P., S. Naitza, C. Kappler, D. Ferrandon, D. Zachary et al., 2001. Drosophila immune deficiency (IMD) is a death domain protein that activates antibacterial defense and can promote apoptosis. Dev. Cell 1: 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebultowicz, J. M., and D. M. Hege, 1997. Circadian clock in Malpighian tubules. Nature 386: 664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist, D. A., S. Nechaev, C. Lee, S. K. Ghosh, J. B. Collins et al., 2008. NELF-mediated stalling of Pol II can enhance gene expression by blocking promoter-proximal nucleosome assembly. Genes Dev. 22: 1921–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot, L., J. S. Bader, C. Brouwer, A. Chaudhuri, B. Kuang et al., 2003. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 302: 1727–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, R., 1944. New mutants report. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 18: 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C. B., and J. C. Besharse, 1996. Identification of a novel vertebrate circadian clock-regulated gene encoding the protein nocturnin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 14884–14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, C. B., N. Douris, S. Kojima, C. A. Strayer, J. Fogerty et al., 2007. Loss of Nocturnin, a circadian deadenylase, confers resistance to hepatic steatosis and diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 9888–9893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönke, S., M. Beller, S. Fellert, H. Ramakrishnan, H. Jäckle et al., 2003. Control of fat storage by a Drosophila PAT domain protein. Curr. Biol. 13: 603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönke, S., A. Mildner, S. Fellert, N. Tennagels, S. Petry et al., 2005. Brummer lipase is an evolutionary conserved fat storage regulator in Drosophila. Cell. Metab. 1: 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén, I., J. L. Mullor, J. Capdevila, E. Sánchez-Herrero, G. Morata et al., 1995. The function of engrailed and the specification of Drosophila wing pattern. Development 121: 3447–3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, E., D. Wiggins, B. Fielding and A. Gould, 2007. Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature 445: 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hege, D. M., R. Stanewsky, J. C. Hall and J. M. Giebultowicz, 1997. Rhythmic expression of a PER-reporter in the Malpighian tubules of decapitated Drosophila: evidence for a brain-independent circadian clock. J. Biol. Rhythms 12: 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger, H. W., E. M. Dewey and J. Ewer, 2008. Bursicon, the tanning hormone of insects: recent advances following the discovery of its molecular identity. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol. 194: 989–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseley, J., and D. Tollervey, 2009. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell 136: 763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z., X. L. Wu, J. J. Michal and J. P. McNamara, 2005. Pattern profiling and mapping of the fat body transcriptome in Drosophila melanogaster. Obesity Res. 13: 1898–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyrova, L. Y., Y. Habara, T. H. Lee and R. P. Wharton, 2007. Translational control of maternal Cyclin B mRNA by Nanos in the Drosophila germline. Development 134: 1519–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, K. P., S. Pradhan, J. P. Wang and R. Allada, 2007. Meta-analysis of Drosophila circadian microarray studies identifies a novel set of rhythmically expressed genes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3: e208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivshenko, J., 1958. New mutants report. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 32: 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, J. J., C. Kent, J. C. Billeter, R. Azanchi, A. K. So et al., 2008. Social experience modifies pheromone expression and mating behavior in male Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 18: 1373–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazareva, A. A., G. Roman, W. Mattox, P. E. Hardin and B. Dauwalder, 2007. A role for the adult fat body in Drosophila male courtship behavior. PLoS Genet. 3: e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C., X. Li, A. Hechmer, M. Eisen, M. D. Biggin et al., 2008. NELF and GAGA factor are linked to promoter-proximal pausing at many genes in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 3290–3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G., and J. H. Park, 2004. Hemolymph Sugar Homeostasis and Starvation-Induced Hyperactivity Affected by Genetic Manipulations of the Adipokinetic Hormone-Encoding Gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 167: 311–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., J. Yue, Y. Zhang, L. Zhou, W. Hao et al., 2008. CLOCK/BMAL1 regulates human nocturnin transcription through binding to the E-box of nocturnin promoter. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 317: 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M. D., X. Jiao, D. Grima, S. F. Newbury, M. Kiledjian et al., 2008. Drosophila processing bodies in oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 322: 276–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y., M. Han, B. Shimada, L. Wang, T. M. Gibler et al., 2002. Influence of the period-dependent circadian clock on diurnal, circadian, and aperiodic gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 9562–9567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley, D., and E. Grell, 1968. Genetic variations of Drosophila melanogaster. Publs. Carnegie Instn. 627: 469. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, H., W. C. Lemon, N. C. Peabody, J. B. Pohl, P. K. Zelensky et al., 2006. Functional dissection of a neuronal network required for cuticle tanning and wing expansion in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 26: 573–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, M. J., and M. Rosbash, 2001. Microarray analysis and organization of circadian gene expression in Drosophila. Cell 107: 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, H., 1952. New mutants report. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 26: 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, S., C. Temme and E. Wahle, 2004. Messenger RNA turnover in eukaryotes: pathways and enzymes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39: 197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. Z., A. Hong, M. A. Lilly and R. Lehmann, 2005. twin, a CCR4 homolog, regulates cyclin poly(A) tail length to permit Drosophila oogenesis. Development 132: 1165–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse, G. W., D. A. Gilchrist, S. Nechaev, R. Shah, J. S. Parker et al., 2007. RNA polymerase is poised for activation across the genome. Nat. Genet. 39: 1507–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, K., 1956. a The effects of the environmental conditions on curled expressivity and the interaction between two mimic genes, curled and Curly, in Drosophila melanogaster. Jpn. J. Genet. 31: 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, K., 1956. b The effects of the environmental conditions on Curly expressivity in Drosophila melanogaster. Jpn. J. Genet. 31: 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Pavelka, J., and L. Jindrák, 2001. Mechanism of the fluorescent light induced suppression of Curly phenotype in Drosophila melanogaster. Bioelectromagnetics 22: 371–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody, N., F. Diao, H. Luan, H. Wang, E. Dewey et al., 2008. Bursicon functions within the Drosophila CNS to modulate wing expansion behavior, hormone secretion, and cell death. J. Neurosci. 28: 14379–14391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody, N., J. Pohl, F. Diao, A. Vreede, D. Sandstrom et al., 2009. Characterization of the decision network for wing expansion in Drosophila using targeted expression of the TRPM8 channel. J.Neurosci. 29: 3343–3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S. E., 1976. Hormonal regulation of cuticle extensibility in newly emerged adult blowflies. J. Insect Physiol. 22: 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S. E., 1977. Control of cuticle extensibility in the wings of adult manduca at the time of eclosion. Effects of Eclosion Hormone and Bursicon. J. Exp. Biol. 70: 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ruberte, E., T. Marty, D. Nellen, M. Affolter and K. Basler, 1995. An absolute requirement for both the type II and type I receptors, punt and thick veins, for dpp signaling in vivo. Cell 80: 889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, C. M., G. W. Davis, R. D. Fetter and C. S. Goodman, 1996. Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity. I. Fasciclin II controls synaptic stabilization and growth. Neuron 17: 641–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semotok, J. L., R. L. Cooperstock, B. D. Pinder, H. K. Vari, H. D. Lipshitz et al., 2005. Smaug recruits the CCR4/POP2/NOT deadenylase complex to trigger maternal transcript localization in the early Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 15: 284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, U., and R. Parker, 2003. Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science 300: 805–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiga, Y., M. Tanaka-Matakatsu and S. Hayashi, 1996. A nuclear GFP/β-galactoside fusion protein as a marker for morphogenesis in living Drosophila. Dev. Growth Differ. 38: 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., and E. Novitski, 1941. The homologies of the chromosome elements in the genus Drosophila. Genetics 26: 517–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B. H., P. Z. Xu and P. M. Salvaterra, 1999. Dynamic visualization of nervous system in live Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 10438–10443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temme, C., S. Zaessinger, S. Meyer, M. Simonelig and E. Wahle, 2004. A complex containing the CCR4 and CAF1 proteins is involved in mRNA deadenylation in Drosophila. EMBO J. 23: 2862–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie, S., M. Ashburner, K. Falls, P. Leyland, P. McQuilton et al., 2009. FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila Gene Ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: D555–D559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, H. R., A. Matsumoto, M. Kawamura, M. Iino, T. Tanimura et al., 2002. Genome-wide transcriptional orchestration of circadian rhythms in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 14048–14052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, C., 1940. The genetic control of wing development in Drosophila. J. Genet. 41: 75–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., D. L. Osterbur, P. L. Megaw, G. Tosini, C. Fukuhara et al., 2001. Rhythmic expression of Nocturnin mRNA in multiple tissues of the mouse. BMC Dev. Biol. 1: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L., 1923. The genetics of Curly Wing in Drosophila. Another case of balanced lethal factors. Genetics 8: 276–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K., X. Zheng and A. Sehgal, 2008. Regulation of feeding and metabolism by neuronal and peripheral clocks in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 8: 289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlinger, J., A. Stark, M. Kellis, J. Hong, S. Nechaev et al., 2007. RNA polymerase stalling at developmental control genes in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo. Nat. Genet. 39: 1512–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]