Abstract

The mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) is required for normal cellular function; inherited and somatic mutations in mtDNA lead to a variety of diseases. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has served as a model to study mtDNA integrity, in part because it can survive without mtDNA. A measure of defective mtDNA in S. cerevisiae is the formation of petite colonies. The frequency at which spontaneous petite colonies arise varies by ∼100-fold between laboratory and natural isolate strains. To determine the genetic basis of this difference, we applied quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping to two strains at the opposite extremes of the phenotypic spectrum: the widely studied laboratory strain S288C and the vineyard isolate RM11-1a. Four main genetic determinants explained the phenotypic difference. Alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 contributed to the high petite frequency of S288C and its derivatives by increasing the formation of petite colonies. By contrast, the S288C allele of MKT1 reduced the formation of petite colonies and compromised the growth of petite cells. The former three alleles were found in the EM93 strain, the founder that contributed ∼88% of the S288C genome. Nearly all of the phenotypic difference between S288C and RM11-1a was reconstituted by introducing the common alleles of these four genes into the S288C background. In addition to the nuclear gene contribution, the source of the mtDNA influenced its stability. These results demonstrate that a few rare genetic variants with individually small effects can have a profound phenotypic effect in combination. Moreover, the polymorphisms identified in this study open new lines of investigation into mtDNA maintenance.

MITOCHONDRIA are responsible for many critical biological processes such as energy production via oxidative phosphorylation (Nelson and Cox 2000), intermediary metabolism (Nelson and Cox 2000), heme biosynthesis (Heinemann et al. 2008), iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis (Lill and Muhlenhoff 2008), the production of reactive oxygen (Balaban et al. 2005), and programmed cell death (Newmeyer and Ferguson-Miller 2003). Of the ∼1000 gene products that function in the mitochondria, only a small subset are encoded in the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) (Sickmann et al. 2003). This subset includes components of the mitochondrial protein translation apparatus and subunits of the protein complexes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (Taylor and Turnbull 2005).

In addition to energy production, oxidative phosphorylation generates the membrane potential (ΔΨ) across the inner membrane of the mitochondrion (Nelson and Cox 2000). ΔΨ is required for the import of most nuclear-encoded proteins into the organelle (Mokranjac and Neupert 2008). Thus, mtDNA, which is essential for oxidative phosphorylation (Taylor and Turnbull 2005), is also important for the maintenance of ΔΨ. For this reason, mtDNA affects many of the biological processes that occur within the mitochondria.

Consistent with the importance of mtDNA integrity, many inherited mutations in mtDNA lead to a spectrum of human diseases that often affect multiple organ systems (Taylor and Turnbull 2005). In addition to inherited mtDNA mutations, acquired mtDNA mutations in somatic tissues accumulate progressively during the normal course of aging (Chomyn and Attardi 2003; Chien and Karsenty 2005). These somatic mtDNA mutations may play a causal role in age-associated diseases such as Parkinson's (Bender et al. 2006; Kraytsberg et al. 2006) and cancer (Ishikawa et al. 2008). Moreover, mice engineered with a proofreading-deficient mitochondrial DNA polymerase (Trifunovic et al. 2004) exhibit a premature aging phenotype that correlates with increased somatic mtDNA deletions (Vermulst et al. 2008).

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an excellent model organism for gaining insights into the molecular basis of human mitochondrial disorders (Barrientos 2003). Unlike metazoans, S. cerevisiae is a facultative anaerobe and can survive without mtDNA, a situation that is not tolerated in obligate aerobes (Hance et al. 2005). Yeast cells with defective (rho−) or no (rho0) mitochondrial genome are referred to as petites because they form small colonies on glucose-containing medium (Ephrussi et al. 1949; Dujon 1981). By contrast, cells that have fully functional mitochondria form grande colonies and are designated rho+. Both rho− and rho0 cells can be propagated on a fermentable carbon source such as glucose, because they are able to generate ATP through glycolysis (Nelson and Cox 2000). However, they cannot grow on a nonfermentable carbon source such as glycerol, because under these conditions ATP synthesis can be achieved only through oxidative phosphorylation (Nelson and Cox 2000).

Mitochondrial genome instability can be quantitatively measured by the frequency of spontaneous petites in a population of yeast cells. While values can vary, the lowest petite frequencies are ∼1% for S. cerevisiae (Sherman 2002). This low end of the spectrum is at least 100-fold higher than the expected occurrence of respiratory-defective yeast cells due to nuclear mutations (Tzagoloff and Dieckmann 1990; Drake 1991). Over 200 complementation groups of nuclear S. cerevisiae mutations leading to respiratory deficiency have been identified (Tzagoloff and Dieckmann 1990), and the spontaneous mutation rate per nuclear gene in S. cerevisiae ranges from 10−7 to 10−8 per cell division (Drake 1991). Given this mutation rate in nuclear genes, the spontaneous petite frequency generally reflects the instability of the mitochondrial rather than nuclear DNA (Dujon 1981).

More than 200 genes are required for the faithful maintenance of rho+ yeast mtDNA (Contamine and Picard 2000; Hess et al. 2009). However, only a fraction of these genes are involved in pathways that directly affect mtDNA transactions such as replication, recombination, and repair, as well as mtDNA packaging into nucleoids, nucleoid division, and nucleoid segregation to daughter cells (Contamine and Picard 2000; Chen and Butow 2005). Loss-of-function mutations in these genes lead to rho− and/or rho0 petites. The involvement of other processes—such as mitochondrial transcription and translation, ATP synthesis, iron homeostasis, and fatty acid metabolism—accounts for the majority of known loss-of-function mutations that increase petite production, but their involvement in mtDNA maintenance is not well understood (Contamine and Picard 2000).

The majority of spontaneously arising petite cells are rho− (de Zamaroczy et al. 1981). Analysis of the mtDNA in a number of spontaneous petite mutants suggests that most such rho− genomes are a head-to-tail tandem repetition of a segment of the rho+ mtDNA (Faugeron-Fonty et al. 1979). The DNA sequence of the repeated segment in spontaneous petite mutants suggests that the repeat may originate from rho+ mtDNA by illegitimate direct-repeat recombination involving short homologous sequences (Gaillard and Bernardi 1979; Gaillard et al. 1980). However, neither the defects in mtDNA processing that lead to direct-repeat recombination nor the conditions that may determine its occurrence are known.

Given the large number of genes that can modulate petite formation, it is not surprising that the spontaneous frequency of petites varies within a large range among laboratory strains of S. cerevisiae (Marmiroli et al. 1980; Sherman 2002). There have been two attempts in the past 50 years to explain the genetic basis for these differences. Soon after the discovery of the petite mutation (Ephrussi et al. 1949), Ephrussi's group identified a laboratory strain with very unstable mtDNA (Ephrussi and Hottinguer 1951). A single, recessive nuclear mutation was responsible for this phenotype, but the identity of the mutant gene was never determined. More recently, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the gene encoding the mitochondrial DNA polymerase (MIP1) was implicated in the increased mtDNA mutability of several common laboratory S. cerevisiae strains (Baruffini et al. 2007).

In the course of studying the age-associated genomic instability that occurs during yeast pedigree analysis (McMurray and Gottschling 2003), we discovered that petite formation can lead to increased nuclear genome instability (Veatch et al. 2009). To understand the basis for how mitochondrial defects arise, we sought to identify genetic determinants that were responsible for the spontaneous petite formation observed. We found that the frequency at which petites arose in a culture varied among different strains of S. cerevisiae, which is consistent with earlier reports (Ephrussi and Hottinguer 1951; Marmiroli et al. 1980). In the study presented here, we use quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping to identify the main genetic determinants of petite formation in the common laboratory strain S288C and its derivatives, which were used in our earlier nuclear genome instability studies (McMurray and Gottschling 2003; Veatch et al. 2009).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids:

The segregants from the BY4716 (MATα lys2Δ0) × RM11-1a (MATa leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 ho∷loxP-kanMX4-loxP) cross have been described in detail elsewhere (Brem et al. 2002; Yvert et al. 2003; Brem and Kruglyak 2005). A list of all the other strains used in this study can be found in Table 1. The construction of the allelic replacement strains is described in detail below. Isogenic haploid derivatives of YPS163, YPS1000, and YPS1009 from Paul Sniegowski's collection of oak yeast isolates (Sniegowski et al. 2002) were created by inactivating the HO endonuclease with a loxP-kanMX4-loxP cassette (Guldener et al. 1996), sporulating the transformants, and selecting the haploid, G418 resistant spores. BY4716 was diploidized by using the pHS2 plasmid (a kind gift of Adam Deutschbauer) as previously described (Deutschbauer and Davis 2005).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Background | Relevant genotype | References or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Σ1278b | Σ1278b | MATα SAL1 MKT1-30G CAT5-91M MIP1-661T | F. Hilger (Gembloux) |

| EM93a | Progenitor of S288C | MATa/α SAL1/sal1-1 MKT1-30G/MKT1-30G CAT5-91M/CAT5-91I MIP1-661T/MIP1-661A | Mortimer and Johnston (1986) |

| UCC1158 | RM11-1a | MATaho∷loxP-KAN-loxP leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SAL1 MKT1-30G CAT5-91M MIP1-661T | Mortimer et al. (1994) |

| BY4716 | S288C | MATα lys2Δ0 sal1-1 MKT1-30D CAT5-91I MIP1-661A | Brachmann et al. (1998) |

| S288C | S288C | MATα mal gal2 sal1-1 MKT1-30D CAT5-91I MIP1-661A | Adams et al. (1997); Mortimer and Johnston (1986) |

| UCC1166 | SK1 | MATα ho∷LYS2 leu2Δ(Asp18-EcoRI) lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SAL1 MKT1-30G CAT5-91M MIP1-661T | Barbara Garvik (Hartwell Lab) |

| YDS3 | W303 | MATα ade2-1, trp1-1, can1-100, leu2-3,112, his3-11,15, ura3 RAP1 wt SAL1 MKT1-30G CAT5-91M MIP1-661A | Lori Sussel (Shore Lab) |

| UCC8407 | YPS163 | MATaho∷loxP-KANMX4-loxP SAL1 MKT1-30G CAT5-91M MIP1-661T | This study |

| UCC8409 | YPS1000 | MATaho∷loxP-KANMX4-loxP SAL1 MKT1-30G CAT5-91M MIP1-661T | This study |

| UCC8411 | YPS1009 | MATaho∷loxP-KANMX4-loxP SAL1 MKT1-30G CAT5-91M MIP1-661T | This study |

| UCC8062-1 | Diploid RM11 | MATa/α LEU2/leu2Δ0 LYS2/lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 ho∷loxP-KAN-loxP/ho∷loxP-KAN-loxP | This study |

| UCC8088-1 | Diploidized BY4716 | MATa/α lys2Δ0/lys2Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8240 | S288C | MATaMKT1-30D ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8241 | S288C | MATaMKT1-30G ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8334 | S288C | MATα lys2Δ0 [S288C rho+] | This study |

| UCC8335 | S288C | MATα lys2Δ0 [S288C rho+] | This study |

| UCC8338 | S288C | MATα lys2Δ0 [RM11 rho+] | This study |

| UCC8339 | S288C | MATα lys2Δ0 [RM11 rho+] | This study |

| UCC8340 | RM11 | MATα ho∷loxP-KAN-loxP lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 [S288C rho+] | This study |

| UCC8341 | RM11 | MATα ho∷loxP-KAN-loxP lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 [S288C rho+] | This study |

| UCC8344 | RM11 | MATα ho∷loxP-KAN-loxP lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 [RM11 rho+] | This study |

| UCC8356 | S288C | MATaMKT1-30G sal1-1 CAT5-91I MIP1-661A ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8357 | S288C | MATaMKT1-30G sal1-1 CAT5-91I MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8358 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G sal1-1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661A ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8359 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G sal1-1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8360 | S288C | MATaMKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91I MIP1-661A ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8361 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91I MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8362 | S288C | MATaMKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661A ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8363 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 | This study |

| UCC8372 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 [RM11 rho+] | This study |

| UCC8374 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 [RM11 rho+] | This study |

| UCC8376 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 [S288C rho+] | This study |

| UCC8378 | S288C | MATα MKT1-30G SAL1 CAT5-91M MIP1-661T ura3Δ0 [S288C rho+] | This study |

| UCC8413 | Hybrid BY4716 × RM11 | MATa/α LEU2/leu2Δ0 LYS2/lys2Δ0 URA3/ura3Δ0 ho/ho∷loxP-kan-loxP | This study |

A kind gift of Joshua Akey's lab.

The plasmid pLND44-4 was used to replace the MIP1-661A allele with the MIP1-661T allele. The plasmid pRS306-MKT1-D30G (a kind gift of Joshua Veatch) was used to replace the MKT1-30D allele with a MKT1-30G allele. Please refer to supporting information, File S1, for details in plasmid construction.

Strain construction for functional analysis:

The allelic exchange experiments were conducted in the BY4724 (MATa lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0) background to be able to use the URA3 marker for positive and negative selection. The MKT1 and MIP1 allelic replacements were executed by a two-step gene replacement strategy using integrating, URA3-marked plasmids (Scherer and Davis 1979; Adams et al. 1997). For the MKT1 replacement, we linearized pRS306-MKT1-D30G with HindIII before transformation. For the MIP1 replacement, we linearized pLND44-4 with AvrII. In both cases, Ura+ transformants were grown in YEPD to allow for the spontaneous excision of the integrated plasmid. These events were selected for by plating cells on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) (Boeke et al. 1987). Several independent, 5-FOA resistant clones were sequenced to screen for those that had retained the new MKT1-30G or MIP1-661T alleles. The SAL1 and CAT5 allelic replacements were executed by two sequential transformations as described in detail elsewhere (Gray et al. 2004). Briefly, the first transformation integrates the URA3 marker into the targeted locus (sal1-1 or CAT5-91I). The second transformation replaces URA3 with a PCR product, which in our case was amplified from RM11-1a genomic DNA (see File S1 for details).

In all single-allele replacement experiments, control replacements with the respective S288C/BY4716 (hereafter S288C/BY) alleles were performed in parallel to rule out background mutations during the transformation process that may reduce the petite frequency. Moreover, two independent transformants for each single replacement were analyzed and found to behave similarly. Proper allele replacements were sequence verified. PCR and sequencing primers are listed in Table S1.

The single-allelic replacement strains were all of the same mating type. After several crosses and sporulations, we constructed a diploid strain that is homozygous for MKT1-30G and heterozygous for SAL1/sal1-1, CAT5-91M/CAT5-91I, and MIP1-661T/MIP1-661A. All the strains in Figure 7 are haploid spores from that single diploid strain and thus isogenic for the S288C genetic background except at the indicated alleles for SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1.

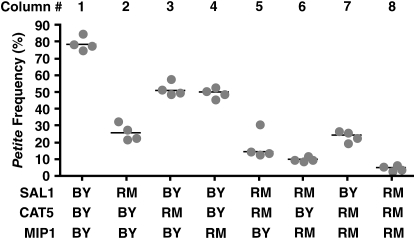

Figure 7.—

SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 are QTGs that affect the petite frequency phenotype. Petite frequencies (as described in Figure 1) of strains containing each of the eight combinations of BY or RM alleles at the SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 QTGs are presented. All eight strains (UCC8356–UCC8363 in Table 1) are haploid spores derived from a single diploid BY strain that was homozygous for MKT1-30G and heterozygous for SAL1/sal1-1, CAT5-91M/CAT5-91I, and MIP1-661T/MIP1-661A (see materials and methods). The BY and RM alleles of each gene are described in the Table 2 legend.

Media and growth conditions:

We used standard YEPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose). The indicator medium for the petite frequency assay was YEPDG (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 0.1% glucose, and 3% glycerol) (Adams et al. 1997). On this type of medium, respiratory-deficient cells give rise to much smaller colonies than respiratory-proficient cells (Tzagoloff and Dieckmann 1990). The difference in colony size between petites and grandes is clearly distinguishable after growth at 30° for 5 days.

To compare the growth of grande cells (Figure 4C and Figure S1, A), we pregrew cells in YEPG (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 3% glycerol) before plating serial dilutions on YEPD. A pure population of petite cells (Figure 4C, Figure S1, A and B) was derived by treating logarithmic-phase cells in YEPD with 25 μg/ml of ethidium bromide for 6 hr (Slonimski et al. 1968). After washing out the ethidium bromide, cells were either plated in serial dilutions on YEPD to compare the growth of petite cells or analyzed using a Powerwave XS plate reader (see File S1).

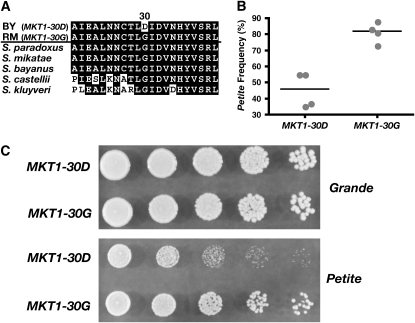

Figure 4.—

MKT1 is a QTG that affects the growth of petite cells. (A) Sequence alignment of the region of the Mkt1 protein that contains the nonsynonymous polymorphism at the 30th amino acid residue (indicated above the alignment). The most common amino acid at each position in the protein is boxed in black. (B) Petite frequencies of strains UCC8240 (MKT1-30D) and UCC8241 (MKT1-30G). (C) Serial dilution spotting of grande (top) and petite (bottom) cells of the strains UCC8240 (MKT1-30D) and UCC8241 (MKT1-30G). See materials and methods for the isolation of pure populations of grande and petite cells.

Petite frequency assay:

Strains were streaked onto YEPD plates from the glycerol freezer stock and allowed to grow into single colonies for 2 days. At least four independent colonies or independent groups of colonies were suspended in sterile 1× PBS. Appropriate PBS dilutions of each independent suspension were plated onto large YEPDG plates. The petite and grande colonies were counted after growth at 30° for 5 days. Colonies were counted manually for Figures 1B and 2 and with ImageJ 1.38x software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) for Figures 1C, 4B, 7, and 8 (see File S1 for details). The reported petite frequency is the ratio of small colonies to total number of colonies. For each strain, we report the median petite frequency of the independent isolates to reduce the effects of any outliers due to jackpot events: petite mutations occurring very early during colony growth.

Figure 1.—

Petites occur at a higher frequency in most common laboratory strains. (A) A 2-day-old YEPD colony of the laboratory strain BY4716 and of the vineyard strain RM11-1a were diluted appropriately and plated onto indicator YEPDG plates to distinguish between petite and grande colonies. Pictures were taken after 5 days of growth. (B) Petite frequencies are presented for several laboratory and natural isolate strains (described in Tables 1 and 3). The petite frequency was determined for four independent isolates of each strain and is represented by a shaded dot. Each solid line represents the median petite frequency. (C) The petite frequencies for diploid strains of the BY (UCC8088-1), RM (UCC8062-1), and hybrid BY × RM (UCC8413) genetic backgrounds.

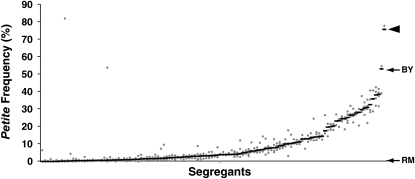

Figure 2.—

Petite frequency is a quantitative trait. A total of 122 segregants from a cross between BY4716 and RM11-1a (Brem and Kruglyak 2005) were assayed for their petite frequencies. Each shaded dot represents the petite frequency of an independent isolate of a segregant. The solid dash indicates the median petite frequency for each segregant based on all independent isolates of that segregant. Segregants are sorted in increasing order of median petite frequency. The arrows point to the median petite frequencies of the parental strains (BY4716 at 52%, RM11-1a at 0.6%). The arrowhead points to the one segregant with median petite frequency greater than that of BY4716.

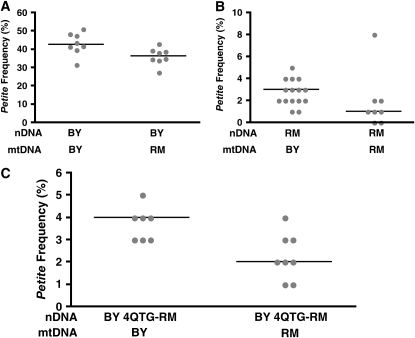

Figure 8.—

The mitochondrial genome affects its own stability. Petite frequencies are shown of isonuclear strains with different mitochondrial genomes constructed via kar crosses (see materials and methods). nDNA, nuclear DNA; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA. (A) Pooled values from two independent isolates containing BY nDNA and BY mtDNA (UCC8334 and UCC8335) or BY nDNA and RM mtDNA (UCC8338 and UCC8339). (B) The same as in A except strains contain RM nDNA and BY mtDNA (UCC8340 and UCC8341) or RM nDNA and RM mtDNA (UCC8344). (C) BY or RM mtDNA was cytoduced by kar cross (see materials and methods) into UCC8363, which is a BY background strain that contains the MKT1-30G, SAL1, CAT5-91M, and MIP1-661T alleles (referred to as BY 4QTG-RM). Shown are pooled values from two independent isolates containing BY 4QTG-RM nDNA and BY mtDNA (UCC8376 and UCC8378) or BY 4QTG-RM nDNA and RM mtDNA (UCC8372 and UCC8374).

Linkage and statistical analysis:

We tested for linkage between a marker and the petite frequency phenotype by dividing the segregants into two groups according to the inheritance of the BY or the RM11-1a (hereafter RM) marker allele. The median petite frequencies for the segregants in the BY vs. the RM group were compared with the nonparametric, Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (Lindgren 1968). The P-value of that test was transformed by taking the negative value of the natural logarithm of the P-value to arrive at the “linkage likelihood” statistic reported in Figure 3. The 5% genomewide significance level in Figure 3 was estimated by empirical permutation tests (Churchill and Doerge 1994). Analogous results were obtained by running the linkage analysis in R/qtl (data not shown). The Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was also used to assess the statistical significance of the difference in petite frequencies between two strains. Fisher's exact test (Prism software) was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference in petite mutation rates (Table 2).

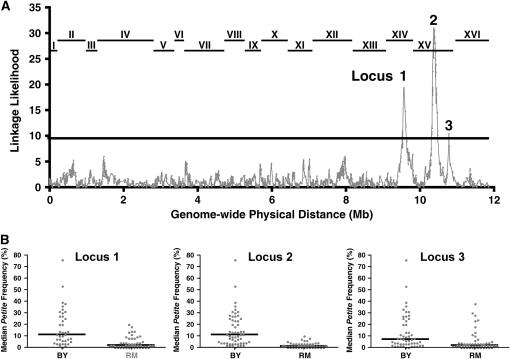

Figure 3.—

The petite frequency phenotype links to at least 3 QTL. (A) Linkage between a polymorphic marker and the median petite frequency phenotype was tested by partitioning the segregants into two groups according to marker inheritance (BY or RM). The median petite frequencies were compared between the two groups with the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney statistical test (Lindgren 1968). The P-value of that test was transformed by taking the negative value of the natural logarithm of the P-value. The shaded line plots the transformed P-value (y-axis) for each marker as a function of the physical location of the marker in the yeast genome (x-axis). The lines at the top of the graph indicate the locations of the 16 S. cerevisiae chromosomes. The solid line at linkage likelihood of 9.3 marks the 5% genomewide significance level, which is adjusted for multiple testing on the basis of empirical permutation tests (Churchill and Doerge 1994). The three loci that reach statistical significance are designated as loci 1, 2, and 3. (B) The median petite frequencies are presented for segregants with unequivocal inheritance at the three loci shown in A of either the BY or the RM parent. For locus 1, analysis was restricted to the 100 segregants with no missing genotype data and no recombination events in the 37.2-kbp window between marker positions 449,639 and 486,861, which are the two markers with the highest linkage likelihood. For locus 2, analysis was restricted similarly to 114 segregants in a 26.4-kbp window (between marker positions 519,776 and 546,197). For locus 3, analysis was similarly restricted to 108 segregants in an 8.7-kbp window between marker positions 937,036 and 945,781, which are the two markers with the highest linkage likelihood.

TABLE 2.

Estimation of petite mutation rates per cell division

| Strain

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCC8240 | UCC8241 | UCC8360 | UCC8358 | UCC8357 | |

| Genotype | |||||

| MKT1 | BY | RM | RM | RM | RM |

| SAL1 | BY | BY | RM | BY | BY |

| CAT5 | BY | BY | BY | RM | BY |

| MIP1 | BY | BY | BY | BY | RM |

| Cell divisions | |||||

| Two grandes | 56 | 38 | 54 | 55 | 55 |

| Petite and grande | 3 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Petite mutation rate (%) | 5 | 22 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| P-value | <0.01a | 0.03b | 0.03b | 0.03b | |

The test compares UCC8241 to UCC8240.

The test compares UCC8360, 8358 or 8357 to UCC8241.

Cells were pregrown in liquid YEPG medium for at least 24 hr to select for a pure population of grande cells. An aliquot of the saturated YEPG culture (1:1000 dilution) was inoculated into YEPD medium. After 10 hr of growth in YEPD, individual unbudded or small-budded cells were picked as mothers and placed at predefined positions on a solid YEPD plate. Newly formed daughter cells were separated from their mother cells by micromanipulation, and the mother and daughter cells were allowed to form independent colonies. The petite and grande status of each cell was inferred from the phenotype of the resulting colony. For MKT1, BY indicates the MKT1-30D allele, and RM indicates the MKT1-30G allele. For SAL1, BY indicates the sal1-1 allele, and RM indicates the wild-type allele. For CAT5, BY indicates the CAT5-91I allele, and RM indicates the CAT5-91M allele. For MIP1, BY indicates the MIP1-661A allele, and RM indicates the MIP1-661T allele.

Genome sequences and alignments:

The source of the BY/S288C sequences was the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) (http://www.yeastgenome.org/). The source of the RM11-1a sequences was the Broad Institute (http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/saccharomyces_cerevisiae/). DNA or protein alignments between BY and RM were performed using the blastn and blastp functionalities respectively provided by the Broad Institute web site. For each gene in locus 2, protein alignments between BY and the other Saccharomyces genus species were performed on the SGD website by using the “Fungal Alignment” option in the “Comparison Resources” drop-down menu from the Summary SGD page for each gene. These alignments are generated by applying the ClustalW multiple sequence alignment algorithm to available sequences from the following six species: S. paradoxus, S. mikatae, S. bayanus, S. kudriavzevii, S. castellii, and S. kluyveri (Cliften et al. 2003; Kellis et al. 2003). Additional protein alignments between BY and species of the Ascomycetes phylum were performed on the SGD website by using the “BLASTP vs. fungi” option in the Comparison Resources drop-down menu from the Summary SGD page of the gene. The Ascomycetes species selected for these additional alignments were Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Wood et al. 2002), Ashbya gossypii (Dietrich et al. 2004), Candida glabrata, Kluyveromyces lactis, Debaryomyces hansenii, Yarrowia lipolytica (Dujon et al. 2004), and Pichia stipitis (Jeffries et al. 2007).

mtDNA swaps:

kar1Δ15 strains derived from BY4700 and RM11-1a served as donors for the BY and RM mitochondrial genomes. The kar1Δ15 allele was introduced into these strains via a pop-in/pop-out strategy using plasmid pMR1593 (Vallen et al. 1992). The strains that served as recipients of the desired mtDNA were rho0 derivatives of BY4716 and RM11-1b. The rho0 strains were isolated by first transforming BY4716 and RM11-1b with pLND46, a derivative of p16G-MIP1-DN (kind gift of J. Veatch, unpublished data). pLND46 is a centromeric plasmid carrying the NatMX cassette as a selectable marker and a galactose-inducible, catalytically inactive allele of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase (MIP1-D918A). Transformants were induced to rho0 petites by clonal growth on galactose and ClonNAT medium. These rho0 recipient strains and the kar1Δ15 donor strains were mated for 4 hr at 30° on YEPD plates. Subsequently, individual zygotes were micromanipulated to defined positions on the plate. Two hours later, individual vegetative cells were separated from the zygotes and placed at new positions on the plate. Colonies that arose from these vegetative cells were screened for the mating type and lysine auxotrophy of the recipient nuclear background. Transfer of the desired mitochondrial genome was confirmed by mtDNA isolation (described below) and EcoRV fingerprinting.

mtDNA isolation:

Strains were grown in liquid YEPGal medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 3% galactose). We find that strains with high mtDNA instability on glucose have robust mtDNA maintenance on galactose. Thus, growing the strains in galactose medium for mtDNA isolation allows us to obtain grande mtDNA genomes essentially unadulterated by petite genomes. The protocol follows the steps in Defontaine et al. (1991) with the following modifications. We performed only two water washes before zymolyase treatment and did not sonicate after the lysis step. Cell debris and nuclei were pelleted at 4300 × g for 12 min. The supernatant was then pelleted at 20,000 × g for 20 min to obtain a crude mitochondrial pellet mostly devoid of contaminating nuclear DNA. RNAse A was added to the mitochondrial lysis buffer to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. The DNA was phenol extracted and precipitated from the aqueous layer with 0.1 vol of sodium acetate and 1 vol of isopropanol. For the fingerprinting analysis, the isolated mtDNA was EcoRV digested and run on a 0.6% agarose gel overnight at 23 V.

RESULTS

Petites occur at higher frequency in most common laboratory strains than in natural isolates:

To determine whether QTL mapping was a feasible method for identifying genetic determinants of petite formation, we took a representative set of S. cerevisiae strains and determined the frequency of petites in these strains using a simple, quantitative measure. Briefly, colonies were grown for 2 days on rich medium with 2% glucose (YEPD), which does not require growing cells to have respiratory mitochondrial function. These colonies were then resuspended and plated onto rich medium with 0.1% glucose and 3% glycerol (YEPDG), on which colonies of petite cells are easily distinguished from colonies that arise from grande cells (Figure 1A) (Adams et al. 1997).

Using this assay, the petite frequencies of five commonly used laboratory strains and four natural S. cerevisiae isolates were measured (Figure 1B). The laboratory strains included S288C, which is a historical laboratory standard that was used as the source of the first completely sequenced eukaryotic genome (Goffeau et al. 1996). BY4716 is a direct descendant of S288C and served as the basis for the systematic deletion collection (Winzeler et al. 1999) and our earlier nuclear genome instability studies (McMurray and Gottschling 2003; Veatch et al. 2009). W303 is also derived in part from S288C, but its lineage appears to include crosses to several other unrelated strains (Winzeler et al. 2003; Schacherer et al. 2007). In contrast, Σ1278b and SK1 do not appear to have been derived from any crosses with S288C (Liti et al. 2009). The RM11-1a strain, a natural isolate from a California vineyard (Mortimer et al. 1994), was chosen because of the QTL mapping resources available (Brem et al. 2002; Yvert et al. 2003). In addition, three natural isolates from oak trees were included because of their documented genetic diversity among wild S. cerevisiae populations (Fay and Benavides 2005).

Petite frequencies were determined for haploid derivatives of all nine strains. All four natural S. cerevisiae isolates had low petite frequencies of <5% (Figure 1B). By contrast, four of the five laboratory strains had median petite frequencies that were higher than those of the natural isolates (Figure 1B). This disparity may indicate that extended propagation of S. cerevisiae strains in the laboratory reduces selection for high-fidelity maintenance of full mitochondrial genome function. More importantly, however, the results suggest that petite formation is a quantitative trait that could lend itself to QTL mapping.

Petite frequency is a quantitative trait in S. cerevisiae:

The high frequency of petite formation in BY4716 and low frequency in RM11-1a (Figure 1, A and B) provided a unique opportunity to identify the genetic determinants that were responsible for petite formation in BY4716 by QTL mapping. BY and RM were crossed and ∼120 recombinant progeny from this cross were genotyped for parental contributions at 2957 polymorphic markers covering >99% of the yeast genome (Brem and Kruglyak 2005). These recombinants were used to map loci important in quantitative traits of gene expression (Brem et al. 2002; Yvert et al. 2003; Brem and Kruglyak 2005), stochastic variation in gene expression (Ansel et al. 2008), proteome variation (Foss et al. 2007), cell morphology (Nogami et al. 2007), and DNA repair sensitivity (Demogines et al. 2008) between BY and RM. Thus, it seemed likely that these same recombinants could be used to map relevant QTL that affected petite formation.

As a first step to determine if the difference in petite frequency between BY and RM had a genetic component, the petite frequency was determined for a diploid strain that was a cross between BY and RM. This hybrid exhibited a low petite frequency, similar to an RM × RM diploid strain, and very different from the relatively high petite frequency of a BY × BY strain (Figure 1C). These results suggested that the petite frequency phenotype was under genetic control and that the RM alleles were dominant to those in BY.

Next, 122 F1 haploid segregants from the BY × RM cross were assayed for their median petite frequencies. These values formed a continuum (Figure 2), ranging from the value for the RM parent to the value for one segregant with a median petite frequency greater than that of the BY parent (Figure 2, arrowhead). These data indicated that the median petite frequency phenotype in the segregants was indeed a quantitative trait. Nineteen segregants had median petite frequencies that were at the same low level as that of the RM parent (<0.6%). If random segregation of unlinked loci and no epistasis are assumed, then these data suggested that at least three loci (1/23 ≈ 19/122 F1 segregants) were responsible for the low petite frequency of the RM parent. The influence of multiple loci on petite formation was also suggested by the presence of one segregant with a median petite frequency of 76% (Figure 2, arrowhead), which is higher than that of the BY parent (52%, Figure 1B). These data are consistent with transgressive segregation, in which nonparental allele combinations at more than one locus in the F1 progeny produce a phenotype that is more extreme than either parental phenotype (Rieseberg et al. 2003).

Linkage analysis identifies three QTL for mtDNA instability:

We tested for linkage between the inheritance of each of the available 2957 polymorphic markers and the median petite frequency phenotype (see materials and methods). Three QTL in the yeast genome reached statistical significance on the basis of permutation tests (Figure 3A) (Churchill and Doerge 1994). Locus 1 is on chromosome XIV. Loci 2 and 3 are both on chromosome XV but are likely to be unlinked genetically given the physical distance between them (∼410 kbp). For all three QTL, inheritance of the RM alleles at each locus was associated with a lower petite frequency (Figure 3B).

MKT1 is a quantitative trait gene that affects petite formation and the growth of petite cells:

Locus 1 coincides with QTL identified in other mapping studies in S. cerevisiae. A SNP in the MKT1 gene contributes to the high-temperature-growth phenotypic difference between BY and a clinical isolate (Steinmetz et al. 2002; Sinha et al. 2006), to the sporulation efficiency difference between BY and SK1 (Deutschbauer and Davis 2005), and to expression quantitative trait differences between BY and RM (Zhu et al. 2008). The MKT1 allele that imparts high-temperature resistance (Sinha et al. 2006) and efficient sporulation (Deutschbauer and Davis 2005) encodes a glycine at the 30th amino acid (MKT1-30G) of the open reading frame (ORF). By contrast, the BY allele encodes an aspartate at residue 30 (MKT1-30D allele) (Figure 4A).

We next asked whether the same amino acid difference in MKT1 affected the petite frequency phenotype. The MKT1-30D allele in the BY genetic background was replaced with an MKT1-30G allele (referred to as BY MKT1-30G) (see materials and methods). The median petite frequency of the BY MKT1-30G strain was 82%, almost twice that of the BY MKT1-30D strain (Figure 4B). This result was unexpected because the linkage analysis predicted that inheritance of an RM allele at locus 1 was associated with a lower petite frequency (Figure 3B). These data indicated that another gene(s) within locus 1 contributed to the original QTL mapping information and provided a larger contribution to the RM-associated phenotype than did MKT1-30G.

The frequency at which petite cells arise in a population is a combination of two processes: the rate at which petite mutants are formed and their relative growth rate compared to the growth rate of grande cells in the population. We carried out single-cell analysis to measure the rate at which petite mutants were formed (Table 2). The petite mutation rate of the BY MKT1-30D strain was 5% while that of the BY MKT1-30G strain was 22% (Table 2), a difference that was statistically significant (P = 0.01). Thus, the MKT1-30G allele increases the rate of petite formation in the BY genetic background, a result consistent with this allele contributing to an increased petite frequency (Figure 4B).

Next, the growth rate of grande cells and newly derived petite cells was compared between the BY MKT1-30D and BY MKT1-30G strains. While there was no growth difference between the two strains when the cells were grande, the BY MKT1-30G strain exhibited a significant growth advantage over the BY MKT1-30D strain when the cells were petite (Figure 4C). Thus, two effects contributed to the higher petite frequency in BY MKT1-30G than in BY MKT1-30D cells. These were (1) a higher rate at which petite mutants were formed (Table 2) and (2) a growth advantage of the petite cells (Figure 4C) when the BY MKT1-30G strain was compared to the BY MKT1-30D strain.

The MKT1-30D allele is specific to the BY/S288C genetic background:

The amino acid at residue 30 in Mkt1 occurs within a highly conserved region (Figure 4A) that is part of the nuclease domain of the protein (Tadauchi et al. 2004). Mkt1 associates with Pbp1, which interacts with the Poly(A) binding protein near the 3′ end of mRNAs (Tadauchi et al. 2004), and appears to regulate mRNA turnover via P bodies (Lee et al. 2009). However, the details of Mkt1 function are unclear. The glycine (MKT1-30G) allele in the RM strain is conserved at this position in all sequenced Saccharomyces species (Figure 4A). It is present in all the common laboratory strains and natural isolates we analyzed, except S288C and its derivative, BY4716 (Table 3). We also queried the Saccharomyces Genome Resequencing Project (SGRP) database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Teams/Team118/sgrp/ and Liti et al. 2009), which contains data on polymorphisms among S288C, W303, SK1, and 33 S. cerevisiae strains from diverse geographical regions and ecological niches. Sixteen of the 33 nonlaboratory S. cerevisiae isolates have high-quality sequence data for MKT1, and all of them carry the MKT1-30G allele. Thus, the MKT1-30D allele present in BY appears to be relatively rare and specific to the BY/S288C genetic background.

TABLE 3.

Strain genotypes at designated genes

| Laboratory strains

|

Natural isolates

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S288C | BY4716 | W303 | SK1 | Σ1278b | RM11-1a | YPS163 | YPS1000 | YPS1009 | |

| MKT1 | BY | BY | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM |

| SAL1 | BY | BY | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM |

| CAT5 | BY | BY | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM |

| MIP1 | BY | BY | BY | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM | RM |

SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 are quantitative trait genes that affect petite formation:

We next wanted to determine which additional alleles within the three QTL contributed to the quantitative difference in petite frequency between the BY and RM strains. We had three considerations in developing our approach to identify these alleles. First, the hybrid BY × RM strain had a petite frequency similar to that of the RM × RM strain (Figure 1C), suggesting that the alleles in BY that contributed to its high petite frequency were recessive to the RM alleles. Second, the high petite frequency in BY/S288C strains was exceptional compared to that in the other strains examined (Figure 1B). Considering these two results together, we hypothesized that the recessive alleles in the BY strain represented partial or complete loss-of-function alleles in genes responsible for faithful mtDNA inheritance. These loss-of-function alleles were present in the BY strain and would be distinct from the normal functioning alleles of the same genes in the RM strain and other wild yeast isolates. Third, there is a polymorphism between BY and RM every ∼1/200 nucleotides on average throughout the genome (Ronald et al. 2005). This divergence means that within the ∼100-kbp region that defines locus 1 or locus 2, there are ∼500 candidate polymorphisms that could explain the difference between the RM and BY petite frequencies.

With these ideas in mind, we took two parallel approaches to identify the relevant polymorphic differences within each locus. We examined candidate genes within the locus: those known to affect mitochondrial genome integrity or transmission (Contamine and Picard 2000). We also focused on nonsynonymous polymorphisms found within the coding region of genes at each locus. The latter approach meant that polymorphisms within intergenic regions (Tanay et al. 2005) or synonymous polymorphisms that might have a phenotypic effect (Kimchi-Sarfaty et al. 2007) were not considered. However, this approach provided an initial screening method to reduce the large number of possible candidates.

To look for polymorphisms, we used the whole-genome sequences available for the BY strain (SGD at http://yeastgenome.org/) and the RM11-1a strain (http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/saccharomyces_cerevisiae/). A 100-kbp region around the peak linkage marker in locus 1 (Figure 5A) contained at least 294 polymorphisms between BY and RM (Figure 5A). A similar analysis in a 97-kbp region around the peak linkage marker in locus 2 (Figure 5B) identified at least 793 polymorphisms between BY and RM.

Figure 5.—

Loci 1 and 2 contain a multitude of genes and polymorphisms that may cause the difference between the BY and RM petite frequencies. Graphical representations of the genes located in locus 1 (A) and locus 2 (B) are presented. The shaded lines plot the linkage likelihood for all the markers at each locus that reached the 5% genomewide statistical significance level (y-axis) as a function of physical location of the marker on chromosome XIV (A) and chromosome XV (B). Below the graphs are diagrams of all the protein-coding genes in these regions generated by the SGD GBrowse interface (www.yeastgenome.org). Below the diagrams are expansions of the subregions where QTGs implicated in this study were found: MKT1 and SAL1 (A) and CAT5 (B). (A) The region between positions 410,121 and 510,213 was BLASTN aligned to the RM11-1a genome to reveal at least 294 polymorphisms between the two parental strains. (B) The region between positions 483,221 and 579,794 was BLASTN aligned to the RM11-1a genome to reveal at least 793 polymorphisms between the two parental strains (Altschul et al. 1997).

Locus 1:

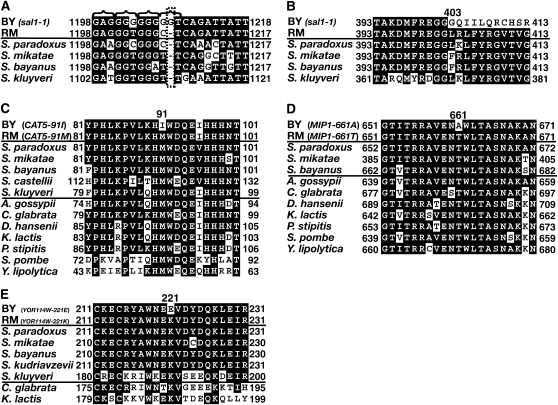

Within locus 1 (Figures 3A and 5A), the SAL1 gene encodes a protein that appears to be a Ca2+-dependent ATP-Mg/Pi exchanger in the mitochondrial inner membrane (Cavero et al. 2005; Traba et al. 2008). Loss-of-function mutations in SAL1 result in decreased mtDNA transmission under certain growth conditions (Kucejova et al. 2008). SAL1 contains a frameshift mutation (the sal1-1 allele) in certain laboratory strains (Chen 2004). The locus history page in the SGD for SAL1 documents that the sal1-1 allele was corrected in the database in February 2004 after sequence comparisons to related fungi (Belenkiy et al. 2000; Brachat et al. 2003). We sequenced the SAL1 gene from BY4716 and S288C. We discovered that these strains both contain the sal1-1 allele despite the correction in the SGD (Figure 6A). The frameshift mutation results in the encoding of missense amino acids starting from the 403rd position of the protein onward (Figure 6B). The mutation also truncates the protein to 494 amino acids from its wild-type length of 545 amino acids. Thus, the sal1-1 mutation is a good candidate for a partial or complete loss-of-function allele that potentially contributes to increased petite frequency in the BY genetic background (Figure 6, A and B).

Figure 6.—

The BY strain contains alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 that likely encode partial or complete loss-of-function proteins. (A) DNA sequence alignment of the region of the SAL1 gene that contains the sal1-1 allele in BY (the inserted nucleotide in the BY lineage is boxed with a dashed line). The brackets above the alignment indicate the register of the open reading frame. The sal1-1 allele was also found in an old S288C isolate (not shown). The most common nucleotide at each position is boxed in black. (B) Sequence alignment of the Sal1 protein. The amino acid position of the frameshift is indicated above the alignment. Protein sequence alignments are shown of Cat5 (C), Mip1 (D), and YOR114W (E) from BY, RM, several closely related Saccharomyces species with available orthologs, and several distantly related Ascomycetes species with available orthologs. Only the regions of the sequence alignments that contain the relevant nonsynonymous polymorphisms are shown. RM contains the evolutionarily conserved ancestral allele while BY contains a derived allele. The position of the allele is numbered above the alignment. The most common amino acid within the Saccharomyces species at each position is boxed in black for all species.

To test the involvement of the sal1-1 mutation in the petite frequency phenotype, we replaced the frameshift mutation in the BY background with the wild-type allele (see materials and methods). The wild-type, RM allele of SAL1, in an otherwise BY MKT1-30G genetic background, suppressed the median petite frequency from 79% to 26% (Figure 7, compare columns 1 and 2). Thus, SAL1 is a quantitative trait gene (QTG) that affects petite frequency.

Locus 2:

In locus 2 (Figure 3A), we analyzed a 97-kbp region around the peak linkage marker (Figure 5B). In this region, there are a total of 47 genes and 109 nonsynonymous polymorphisms between the BY and RM strains. To reduce the number of possible polymorphisms to assay for petite frequency, we first considered only nonsynonymous polymorphisms between BY and RM in regions that were well conserved over the evolutionary timescale of Saccharomyces genus evolution [5–20 million years (Kellis et al. 2003)]. Such polymorphisms are most likely to affect protein function (Hanks et al. 1988; Casari et al. 1995). The ORFs of the 47 genes were aligned with the corresponding amino acid sequences from BY, RM, and six other sequenced species in the Saccharomyces genus (Cliften et al. 2003; Kellis et al. 2003). By requiring that the corresponding amino acid encoded in the RM strain be conserved, the number of polymorphism candidates was reduced from 109 to 8 (1 in YVC1, RAS1, YOR114W, CAT5, RGA1, and ORT1 and 2 in YOR093C). An additional requirement for evolutionary conservation was placed by using sequences from seven more distantly related species of the Ascomycetes phylum, to which the Saccharomyces genus belongs (see materials and methods). The estimated evolutionary distance between these additional Ascomycetes species is at least 300 million years (Wood et al. 2002; Dujon et al. 2004). This additional constraint reduced the number of nonsynonymous polymorphisms for consideration from 8 to 2: one in the CAT5 gene (Figure 6C) and the other in the YOR114W gene (Figure 6E).

CAT5 encodes a monooxygenase that localizes to mitochondria and catalyzes a step in the biosynthesis of ubiquinone, which is an electron carrier in the electron transport chain (ETC) (Marbois and Clarke 1996; Jonassen et al. 1998). The CAT5 polymorphism gives rise to isoleucine in BY and methionine in RM at the 91st amino acid residue (Figure 6C). The BY isoleucine allele (CAT5-91I) was replaced with the RM methionine allele (CAT5-91M) (see materials and methods). The CAT5-91M allele suppressed the median petite frequency from 79% in the BY MKT1-30G CAT5-91I strain to 51% in the BY MKT1-30G CAT5-91M strain (Figure 7, compare columns 1 and 3). Thus, CAT5 is a QTG that affects the petite frequency phenotype. Allele replacement for the candidate polymorphism in YOR114W (Figure 6E), a gene of unknown function, did not affect the petite frequency phenotype (data not shown).

Locus 3:

During the course of our study, an allele of MIP1, the mitochondrial DNA polymerase, was implicated in the elevated mtDNA mutability of some laboratory strains (Baruffini et al. 2007). This MIP1 allele is present in BY, but not in RM. The polymorphism encodes alanine in BY and threonine in RM at the 661st amino acid of the Mip1 protein. The threonine at this position is conserved across the Saccharomyces and Ascomycetes species (Figure 6D). Thus, the BY allele was likely to encode a partial loss-of-function protein. These data, together with the fact that the allele was <2 kbp from the marker of peak linkage in locus 3 (Figure 3A), strongly implicated this polymorphism in petite formation. Therefore, the alanine allele (MIP1-661A) in BY was replaced with the RM threonine allele (MIP1-661T) at the MIP1 genomic locus (see materials and methods) and tested for petite frequency. The MIP1-661T allele suppressed the median petite frequency from 79% in the BY MKT1-30G MIP1-661A strain to 50% in the BY MKT1-30G MIP1-661T strain (Figure 7, compare columns 1 and 4). Thus, MIP1 is a QTG that affects the petite frequency phenotype (Baruffini et al. 2007).

As previously mentioned, the petite frequency is a combination of the petite mutation rate and the relative growth rate of petite and grande cells. We measured the rate of petite formation in the different single-allele replacement strains (Table 2). We found that each one of the wild-type SAL1, CAT5-91M, or MIP1-661T alleles reduced the petite mutation rate in an otherwise BY MKT1-30G genetic background (Table 2). We also compared the growth of grande cells and of newly derived petite cells from the different allele replacement strains. We did not see gross differences in the growth of grande or petite cells by the serial dilution assay (Figure S1, A). We also carried out a more detailed kinetic analysis of the growth of petite cells of the single-allele replacement strains (Figure S1, B). Under these more sensitive conditions, we observed a slight, but statistically significant, growth advantage for petite cells of the CAT5-91M and wild-type SAL1 genotypes (Figure S1, B). Such an improvement in the growth of petite cells is expected to increase the petite frequency. However, the CAT5-91M and wild-type SAL1 genotypes decrease the petite frequency (Figure 7, columns 2 and 3). Taken together, our results suggest that the SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 polymorphisms lower the petite frequency primarily by reducing the rate at which new petite cells are formed.

The SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 polymorphisms, in combination, account for nearly all the difference in petite formation between BY and RM:

The difference in median petite frequency between BY and RM, when both contained the MKT1-30G allele, was >100-fold (79% for BY, Figure 7, vs. 0.6% for RM, Figure 1B). We next asked how much of this difference could be attributed to the SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 alleles and whether these alleles genetically interacted to contribute to this difference.

To address these questions, we created isogenic BY strains with all the possible combinations of BY or RM alleles in SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1. All eight strains had the MKT1-30G allele that gave robust growth of petite cells (Figure 4C). When all three BY alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 were present, the strain had a median petite frequency of 79% (Figure 7, column 1). In contrast, when all three RM alleles were present, the median petite frequency was 5% (Figure 7, column 8). As previously described, the median petite frequency of the original RM parental strain (also MKT1-30G) was 0.6% (Figure 1B). From these results, we conclude that the combination of the three polymorphisms in SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 explains ∼94% [(79% − 5%)/(79% − 0.6%)] of the difference between the BY and RM strains when both carry the MKT1-30G allele.

Analysis of individual QTGs revealed that the SAL1 allele had the greatest impact on petite frequency (Figure 7). When only the BY allele of SAL1 was present, the strain had a median petite frequency of 24% (Figure 7, column 7). By contrast, individual BY alleles of MIP1 and CAT5 had median frequencies of 14 and 10%, respectively.

When pairs of alleles were combined, both additive and synergistic effects were obvious. The combination of CAT5 and MIP1 BY alleles appeared to have an additive affect on petite frequency; when both were present, the median petite frequency was 26% (Figure 7, column 2), compared with 10 and 14% individually. By contrast, when the BY allele of SAL1 was combined with BY alleles of either CAT5 or MIP1, there was evidence of nonadditive effects. Specifically, the median petite frequency of the strain with a single BY allele of SAL1, 24% (Figure 7, column 7), and of CAT5, 10% (Figure 7, column 6), added up to less than the median petite frequency of the strain with BY alleles of SAL1 and CAT5, 50% (Figure 7, column 4). A similar, nonadditive interaction was observed for the combined effect of the SAL1 and MIP1 alleles (Figure 7, compare column 3 to the sum of columns 5 and 7). The most extreme deviation from an additive model was observed when all three loci were combined. The median petite frequency of the strain with a single BY allele of SAL1, 24% (Figure 7, column 7), of CAT5, 10% (Figure 7, column 6), and of MIP1, 14% (Figure 7, column 5), added up to less than two-thirds that of the triple BY allele strain, 79% (Figure 7, column 1).

The BY alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 are rare in natural isolates and originated in the main founder of the S288C strain:

Petite formation in the BY/S288C strains was inordinately high compared to that in most other strains we examined (Figure 1B), and the high frequency resulted primarily from the alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 (Figure 7). Assuming petite formation does not provide a long-term benefit to the cell, we wondered how these three alleles came to be present in the BY/S288C strain background. We started by asking whether the SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 polymorphisms identified here were common or rare in S. cerevisiae strains. We sequenced these polymorphisms in the common laboratory strains and in the natural isolates that we analyzed for petite frequency (Figure 1B and Table 3). The BY/S288C alleles of SAL1 and CAT5 were not present in any of the other strains (Table 3). All these strains contained the RM alleles of these two genes. For MIP1, the BY allele was present in the W303 common laboratory strain, but the RM allele was present in the other six strains analyzed (Table 3). Extending this analysis to other natural isolates of S. cerevisiae revealed that the high-quality or imputed sequences of all 33 nonlaboratory strains in the SGRP database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Teams/Team118/sgrp/) contained the RM alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1. Thus, the BY alleles of these genes appear to be relatively rare in nature.

We next investigated the diploid EM93 strain, which is the main progenitor of S288C (Mortimer and Johnston 1986). We sequenced the four spores of an EM93 tetrad. We found that EM93 is heterozygous for sal1-1 and contains both the CAT5-91I and CAT5-91M alleles, as well as both the MIP1-661A and MIP1-661T alleles (Figure S2). Thus, the BY alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1, which were all absent from the SGRP natural isolates, were all present in the EM93 diploid strain, but in a heterozygous state. We conclude that the most likely origin of the BY alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 is the EM93 strain, particularly given that this strain contributed ∼88% of the S288C genome (Mortimer and Johnston 1986).

The mitochondrial genome affects its own stability:

Our linkage analysis focused on nuclear genetic markers that were strongly associated with the petite frequency phenotype (Figure 3A). However, in addition to polymorphisms in the nuclear genome, variation in the mtDNA itself can affect petite frequency (Contamine and Picard 2000). As a first step to determine whether such a scenario affected the results reported here, the structure of the mitochondrial genome was analyzed in the BY and RM parent strains and in eight F1 segregants (Figure 2). This set of eight segregants included those with the lowest (<1%) and highest (76%) median petite frequencies. EcoRV digestions of mtDNA isolated from each strain revealed restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP) (Botstein et al. 1980) that differed between the BY and RM strains (Figure S3, compare lanes 2 and 3). In addition, the eight F1 segregants were different from either parent, but all eight segregants were identical to one another. This latter result was consistent with the fact that all F1 segregants were derived from a single BY4716 × RM11-1a hybrid, diploid clone (R. Brem, unpublished results). Moreover, the mtDNA restriction pattern of the eight F1 segregants appeared to be a recombinant version of the two parental mitochondrial genomes. In S. cerevisiae, parental mtDNAs are free to recombine during zygote formation and homoplasmic, vegetative diploid cells are quickly established from the zygote (Dujon 1981). Thus, the diploid clone that was sporulated for the derivation of the F1 segregants was homoplasmic for its mtDNA: a recombinant between the two parental mtDNAs. Given that eight F1 segregants with a wide range of median petite frequencies all contained the same mtDNA, we conclude that the linkage analysis between petite frequency and nuclear genotype was not confounded by additional variation in the mtDNA segregating in the cross.

However, the question still remained whether the petite frequency, which differed so dramatically between the two haploid parents, was affected by the differences in the parental mitochondrial genomes. To address this question, isonuclear strains were created that contained the two different parental mitochondrial genomes (see materials and methods). In BY isonuclear strains, an RM mtDNA resulted in a slight, but statistically significant, decrease in the median petite frequency when compared to BY mtDNA [from 43 to 36%, P-value = 0.02 (Figure 8A)]. Similarly, in RM isonuclear strains, RM mtDNA produced a slightly lower median petite frequency than BY mtDNA [from 3 to 1%, P-value <0.01 (Figure 8B)]. Finally, strains were created that contained the two different parental mtDNAs but had a common nuclear genetic background isogenic with BY except for the RM alleles at the four QTGs: MKT1, SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 (referred to here as BY 4QTG-RM). Even in a nuclear genetic background such as BY 4QTG-RM, which is associated with a very low petite frequency (Figure 7, column 8), the RM mtDNA led to an even lower median petite frequency than the BY mtDNA (Figure 8C). Thus, the RM mtDNA leads to a lower petite frequency regardless of the nuclear genetic background.

The result that the mitochondrial genome can affect its own stability suggested that either a polymorphic gene product or a cis feature of the RM mtDNA was responsible for its greater stability. One of the most common differences between yeast mitochondrial genomes is the presence or the absence of introns in the COX1, COB, and 21S_rRNA genes (Dujon 1981; Pel and Grivell 1993). It is also known that intronless mtDNA is more stable than intron-containing mtDNA (Contamine and Picard 2000). To test whether such a situation may explain the difference in mtDNA stability between BY and RM, both mitochondrial genomes were examined for the presence of introns in the COX1 and 21S_rRNA genes (Table 4). The RM mtDNA genome lacked 5 of the 13 introns present in the BY mtDNA (Table 4). These structural variants between the BY and the RM mtDNA explain some of the differences in the EcoRV digestion pattern of the two mitochondrial genomes (Figure S3). Given that intronless mtDNA genomes are more stable (Contamine and Picard 2000), we speculate that the lack of some introns in the RM mtDNA causes its greater stability.

TABLE 4.

Analysis of mitochondrial introns

| PCR confirmation

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intron | Gene | BY | RM |

| aI1 | COX1 | + | − |

| aI5a | COX1 | + | − |

| aI5b | COX1 | + | − |

| aI5c | COX1 | + | − |

| r1 | 21S_rRNA | + | − |

Total DNA (nuclear and mitochondrial) from either the BY4716 or the RM11-1a strain was used as template in PCR reactions. Primer pairs (see Table S1) annealing to the exons that flank the listed introns were used. A minus (−) indicates that the PCR reaction amplified the shorter product, consistent with the absence of the respective intron in RM. A plus (+) indicates that the presence of the respective intron in BY was confirmed by PCR (see Table S1 for primers). Intron names are according to Pel and Grivell (1993).

DISCUSSION

Taking advantage of QTL mapping methods, we have identified four alleles in the common budding yeast laboratory strains BY/S288C that account for nearly all of the difference in spontaneous petite frequency observed between these strains and natural isolates of S. cerevisiae. The BY/S288C alleles in the SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 genes combine to increase the petite frequency (Figure 7) primarily by increasing the rate of petite formation (Table 2). By contrast, the S288C-specific allele of MKT1 reduces the petite frequency by lowering the rate of petite formation (Table 2) and by causing petites to grow very slowly and/or become inviable (Figure 4C). The identification of these alleles provides us with a genetic foundation for understanding how mitochondrial dysfunction can affect age-associated nuclear genome instability (McMurray and Gottschling 2003; Veatch et al. 2009). It also has practical implications for many yeast laboratories that use these strains, particularly those in which the presence of petites could affect the studies.

Origin of the BY/S288C alleles:

The S288C variants of MKT1, SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 appear to be rare alleles when compared to the collection of 33 nonlaboratory isolates of S. cerevisiae with sequenced genomes (Liti et al. 2009). However, we were able to trace the origin of the sal1-1, CAT5-91I, and MIP1-661A alleles in S288C to the EM93 strain, the main founder of the S288C strain (Mortimer and Johnston 1986). The fact that EM93 was isolated from a rotting fig in California raises the possibility that while rare, the S288C variants in SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 arose in the wild. Importantly, these rare variants are present in EM93 in the heterozygous state, complemented by the more common alleles. By contrast, EM93 is homozygous for the common MKT1-30G allele. Thus, the MKT1-30D allele in S288C is likely of laboratory origin.

We speculate that Mortimer inadvertently selected for the MKT1-30D allele during the creation of the S288C strain (Mortimer and Johnston 1986) because this allele reduces the petite frequency in the S288C genetic background (Figure 4B and Table 2). Moreover, the MKT1-30D allele produces a smoother colony morphology than the MKT1-30G allele (L. N. Dimitrov and D. E. Gottschling, unpublished observations). As we have shown here, the MKT1-30G allele permits petite cells to grow well, although they grow somewhat more slowly than grande cells (Figure 4C). When a cell with the MKT1-30G allele becomes petite during the growth of a colony, the cell and the somewhat slower growth of subsequent progeny produce a “lethal sector” or “nibbled” appearance in a colony (James and Werner 1966). By contrast, the MKT1-30D allele, which causes the petite cell to grow very slowly and/or die, cannot effectively compete against the growth of the grande cells around it and hence does not contribute to the colony mass—there are no slow-growing sectors in the colony.

During the derivation of the S288C strain, Mortimer selected for strains that dispersed easily into single cells in liquid culture (Mortimer and Johnston 1986). One allele in S288C that contributes to easy dispersal is flo8-1, which contains a nonsense mutation that disrupts the function of the encoded transcription factor required for flocculation, diploid pseudohyphal growth, and haploid invasive growth (Liu et al. 1996). Another S288C allele that confers easy dispersal is AMN1-368V (Yvert et al. 2003; Ronald et al. 2005). However, the EM93 strain, which contributed 88% of its genome to S288C, contains a functional FLO8 gene (Liu et al. 1996) and the more common AMN1-368D allele (Ronald and Akey 2007). Given the desire for cellular dispersal, it is easy to appreciate why the common EM93 alleles of FLO8 and AMN1 were not fixed in S288C. In contrast to flo8-1 and AMN1-368V, the S288C alleles of SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 do not improve dispersal into single cells (data not shown). Nor are these alleles tightly linked to FLO8 (or any of the other FLO genes) or to AMN1. Thus, it is unlikely that Mortimer selected for these alleles in deriving S288C from EM93. We favor the alternative possibility that these alleles randomly segregated into S288C during its derivation from EM93, a process in which several selection steps imposed severe genetic bottlenecks on the populations that eventually produced S288C (Mortimer and Johnston 1986). Due to this founder effect, the sal1-1, CAT5-91I, and MIP1-661A alleles are commonly encountered in laboratory strains (S288C and its derivatives). One reason why these alleles, which are mildly deleterious with respect to mtDNA inheritance, are still maintained in the S288C genetic background may be that the standards of care of laboratory strains do not place as strong a selective pressure on yeast populations as the selective pressure that occurs outside the laboratory environment (Figure 1B).

Comparison to other studies:

Shortly after the discovery of petite colonies (Ephrussi et al. 1949), it was appreciated that the mtDNA in some yeast strains is unusually unstable (Ephrussi and Hottinguer 1951). For example, in one haploid strain from the Ephrussi lab (known as B15), the petite mutation rate was found to be 4% per cell generation (Ephrussi and Hottinguer 1951). By crossing the B15 strain to one with a more stable mtDNA, the instability of the B15 strain was determined to be a recessive trait controlled by a single nuclear gene (Ephrussi and Hottinguer 1951). However, the identity of this gene was never determined. Our analysis of the petite mutation rate revealed that the mtDNA instability in BY was comparable to that of B15 (5% per cell generation; Table 2). The high mtDNA instability in BY was also a recessive trait. In contrast to Ephrussi's results, we found that the recessive trait was controlled by at least three nuclear QTL. By identifying a causative gene in each of these QTL, we have demonstrated the power of modern mapping technologies for dissecting ideas about unstable mtDNA phenotypes described >50 years ago.

Recently, a computation-based screen for genes that might affect mitochondrial function or transmission identified 100 single-deletion mutant alleles that significantly altered petite frequency relative to the wild-type BY/S288C strain that was used in the analysis (Hess et al. 2009). Interestingly, none of the CAT5, MIP1, MKT1, and SAL1 genes was identified in this screen. Of these four genes, only MIP1 (the gene encoding the mitochondrial DNA polymerase) is present in the compendium of nuclear-encoded genes that have been examined for altered petite frequency since the original Ephrussi work (Contamine and Picard 2000). Our results demonstrate that QTL mapping provides a complementary approach for understanding the complexity of mitochondrial genome maintenance and transmission.

The MIP1-661A allele was recently implicated as the cause for the mtDNA instability observed in most laboratory strains (Baruffini et al. 2007). Consistent with this study, we found that replacing the MIP1-661A allele at its genomic locus with the MIP1-661T allele partially suppressed the petite frequency phenotype (Figure 7). However, our analysis identified at least two other polymorphisms, namely those in SAL1 and CAT5, that contributed to the increased mtDNA instability of S288C-derived laboratory strains (Figure 7). This difference is most easily explained by the fact that the prior study used a W303-derived strain for the allele swapping and phenotypic analysis. In W303, the MIP1 allele is the only one that is derived from S288C, while the CAT5, MKT1, and SAL1 alleles are the same as the common alleles in RM11-1a and the natural isolates (Table 3).

From a QTL mapping point of view, there are at least three studies that used S. cerevisiae as a model system to dissect the genetic architecture of a quantitative trait down to the molecular level (Steinmetz et al. 2002; Deutschbauer and Davis 2005; Gerke et al. 2009). Each one of these studies implicated three QTGs in their quantitative phenotypes: high temperature growth or sporulation efficiency. Our study reveals a comparable complexity in the genetic architecture of a quantitative trait by identifying four QTGs in three QTL. Moreover, the success in dissecting the petite frequency phenotype with 120 segregants demonstrates that it is possible to identify the main genetic determinants of a quantitative trait despite genetic interactions among the QTGs.

Mechanism of spontaneous petite formation:

The prevailing model for the mechanism of spontaneous petite formation in S. cerevisiae postulates that petite genomes arise from the wild-type mtDNA by illegitimate direct-repeat recombination, which is facilitated by the high prevalence of repetitive DNA in the mitochondrial genome (Bernardi 2005). Since Mip1, the mitochondrial DNA polymerase, is directly involved in replicating the mtDNA, we speculate that the S288C MIP1-661A allele leads to defects in mtDNA replication that increase the likelihood of illegitimate direct-repeat recombination. In yeast nuclear DNA, it has been shown that reduced expression of the replicative DNA polymerase α leads to increased homologous recombination events between yeast retrotransposons (Ty elements) on separate yeast chromosomes (Lemoine et al. 2005). The preferred sites for DNA double-strand breaks, which initiate recombination, involve two Ty elements that are in close proximity and have the potential to form a hairpin-like secondary structure (Lemoine et al. 2005). The mitochondrial genome of S. cerevisiae contains several putative origin-of-replication (ori) sequences that could also form hairpin-like secondary structures (de Zamaroczy et al. 1981). By analogy to Ty-mediated recombination, we propose that the MIP1-661A allele reduces the abundance of the Mip1 protein, leads to slow-moving replication forks, or gives rise to other perturbations in mtDNA replication that expose the ori sequences as fragile sites of double-strand DNA. Illegitimate recombination with ori sequences elsewhere in the mtDNA can lead to the production of petite genomes that are a subset of the rho+ mtDNA. Consistent with this model, the vast majority of spontaneous petite genomes contain an mtDNA ori sequence (de Zamaroczy et al. 1981).

We hypothesize that unlike the direct effect of MIP1 on mtDNA maintenance, SAL1 and CAT5 act indirectly by affecting the maintenance of an electrical potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane (ΔΨ). ΔΨ is critical for the normal maintenance of mtDNA (Chen 2002; Wang et al. 2008). This gradient is required for import of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins, including those involved in mitochondrial genome replication and maintenance (Mokranjac and Neupert 2008). Two ways that yeast cells grown on glucose, as was done in this study, can generate ΔΨ are (1) through the ETC, which pumps protons across the inner membrane into the intermembrane space (Nelson and Cox 2000), and (2) through ATP synthase, which normally uses the proton gradient to make ATP, but can “run backward” whereby it hydrolyzes ATP located in the matrix to generate a proton gradient (Traba et al. 2008). This latter process is coupled with mitochondrial ATP transporters, which provide a source of ATP inside the matrix (Dupont et al. 1985; Smith and Thorsness 2008). Thus, when yeast are grown on glucose, their mitochondria consume, rather than produce, ATP (Traba et al. 2008).

SAL1 encodes a mitochondrial ATP carrier that transports ATP into the mitochondrial matrix through the mitochondrial inner membrane (Cavero et al. 2005). Thus, the ATP imported into the matrix by Sal1 fuels the maintenance of ΔΨ. We propose that the sal1-1 allele reduces the efficiency of this transport and compromises the ability of the mitochondria to maintain a robust ΔΨ. Cat5 is a monooxygenase required for the biosynthesis of ubiquinone, a critical component of the ETC (Marbois and Clarke 1996; Jonassen et al. 1998). Here again, we propose that the CAT5-91I allele compromises the maintenance of ΔΨ on glucose. Together, the sal1-1 and CAT5-91I alleles affect mtDNA maintenance indirectly; they both compromise ΔΨ.

Considerations for mapping complex polygenic traits:

Mitochondrial genome instability is, to various degrees, a common phenotype in S. cerevisiae laboratory strains (Figure 1B). As noted above, it is affected by a plethora of genes (Contamine and Picard 2000; Hess et al. 2009). We have identified alleles in three such genes (SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1) that in combination produce a high mtDNA instability in the BY/S288C strain. These three alleles account for nearly all of the phenotypic difference between BY and RM (Figure 7). However, these alleles cannot fully explain the phenotype of the extreme F1 segregant with 76% median petite frequency (Figure 2, arrowhead). On the basis of our allele interaction analysis (Figure 7), we expected the genotype of this segregant to be MKT1-30G, sal1-1, CAT5-91I, and MIP1-661A. We sequenced this segregant at the four QTGs and found that its genotype deviated from our expectation at the MKT1 gene; i.e., it was MKT1-30D rather than MKT1-30G (data not shown). Thus, additional loci affecting petite frequency must be segregating in the BY × RM cross to result in an extreme phenotype that cannot be fully explained by the four QTGs. We did not detect statistically significant linkage to additional genomic loci presumably because their individual effect on petite frequency was too small. However, we propose that these additional loci, in combination, can contribute to the high mtDNA instability observed in the extreme F1 segregant (Figure 2, arrowhead). Similar epistatic interactions that are hard to detect by conventional genetic crosses have been uncovered by using whole-chromosome substitutions in mammals (Shao et al. 2008).

While the three polymorphisms in SAL1, CAT5, and MIP1 account for nearly all the phenotypic difference between BY and RM, in another laboratory strain, SK1, the high mtDNA instability is not due to any of the S288C-specific variants (Figure 1B and Table 3). Thus, more than one genetic architecture can give rise to a complex phenotype such as petite frequency, which is affected by multiple genes (Contamine and Picard 2000; Hess et al. 2009). The difference between SK1 and BY/S288C and the presence of the extreme F1 segregant (Figure 2, arrowhead) are sobering reminders of the concept of genotypic equivalence: different combinations of alleles can confer effectively the same phenotype (Weiss 2008). Genotypic equivalence predicts that determining all the alleles in the human population that contribute to the emergence of polygenic human disease phenotypes will be quite challenging given the large number of genes that can affect complex phenotypes (Weiss 2008). Thus, current efforts in human genetics such as whole-genome association studies (McCarthy et al. 2008) and resequencing of candidate genes for rare variants (Cohen et al. 2004; Ji et al. 2008) are probably uncovering only the tip of the genotypic iceberg.

Acknowledgments

We thank current and former members of the Gottschling laboratory for critical reading of this manuscript and many helpful discussions during the course of this study. We thank Michael McMurray for making the original observation of low petite frequency in RM11-1a, Erin Smith for providing valuable insights into the allelic replacements of candidate genes, Joshua Bloom for running the linkage analysis in R/qtl, Joshua Akey for the EM93 strain and help with the SGRP database, Joshua Veatch for the pRS306-MKT1-D30G and p16G-MIP1-DN plasmids, Adam Deutschbauer for the pHS2 plasmid, Paul Sniegowski for the wild oak yeast isolates, Kin Chan for suggesting the idea of scanning plates for colony counting, and David McDonald of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Scientific Imaging Shared Resources for help with ImageJ. This work was supported by a Simon Fellowship from the Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington (to L.N.D.), by a Burroughs-Wellcome Career Award at the Scientific Interface (to R.B.B.), by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R37 MH059520 and a James S. McDonnell Foundation Centennial Fellowship (to L.K.), and by NIH grant R01 AG023779 (to D.E.G.).

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.104497/DC1.

References

- Adams, A., D. E. Gottschling, C. A. Kaiser and T. Stearns, 1997. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang et al., 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]