Abstract

We designed and experimentally validated an in silico gene deletion strategy for engineering endogenous one-carbon (C1) metabolism in yeast. We used constraint-based metabolic modeling and computer-aided gene knockout simulations to identify five genes (ALT2, FDH1, FDH2, FUM1, and ZWF1), which, when deleted in combination, predicted formic acid secretion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under aerobic growth conditions. Once constructed, the quintuple mutant strain showed the predicted increase in formic acid secretion relative to a formate dehydrogenase mutant (fdh1 fdh2), while formic acid secretion in wild-type yeast was undetectable. Gene expression and physiological data generated post hoc identified a retrograde response to mitochondrial deficiency, which was confirmed by showing Rtg1-dependent NADH accumulation in the engineered yeast strain. Formal pathway analysis combined with gene expression data suggested specific modes of regulation that govern C1 metabolic flux in yeast. Specifically, we identified coordinated transcriptional regulation of C1 pathway enzymes and a positive flux control coefficient for the branch point enzyme 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH). Together, these results demonstrate that constraint-based models can identify seemingly unrelated mutations, which interact at a systems level across subcellular compartments to modulate flux through nonfermentative metabolic pathways.

FORMIC acid is an important intracellular metabolite that has been adapted for specific functions in different organisms. It is produced and secreted in small amounts as a fermentation by-product by bacteria in the family Enterobacteriaceae (Leonhartsberger et al. 2002) and in large quantities as an irritant and pheromone by ants (Hefetz and Blum 1978). Formic acid is used commercially as a preservative in animal feed and has a potential use as a precursor to hydrogen, since it is one of only a few biological molecules with sufficient reducing potential (Milliken and May 2007). The main pathway for biohydrogen production during mixed acid fermentation in Escherichia coli proceeds through a formic acid intermediate: a product of the reaction catalyzed by pyruvate formate lyase (PFL) (EC 2.3.1.54) (Birkmann et al. 1987).

As yeast (and other eukaryotes) lack a PFL homolog, their primary source of formic acid is through tetrahydrofolate (THF)-mediated one-carbon (C1) reactions present in the mitochondria (McNeil et al. 1996). In mammalian cells C1 metabolism is responsible for up to 90% of single carbon units required for nucleotide biosynthesis (Fu et al. 2001). The first reaction in this pathway is catalyzed by the branch point enzyme 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH) (EC 1.1.1.95) encoded by the yeast isozymes SER3 and SER33. The NAD-dependent oxidation reaction catalyzed by PGDH is nonfermentative: oxygen, rather than organic substrate, acts as the final electron acceptor to maintain redox homeostasis under conditions where high levels of serine and formic acid are synthesized from the glycolytic intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) (Peters-Wendisch et al. 2005).

Constraint-based (stoichiometric) models are capable of describing systems-level properties of metabolic networks without requiring specific information about molecular mechanism or reaction-specific kinetics. As many of these parameters are often unknown, constraint-based methods have advantages over their kinetic counterparts as practical tools for developing systems-level metabolic engineering strategies. These models rely on well-annotated genomic sequences to define sets of metabolites and the stoichiometric matrix of known biochemical reactions. Once these are defined, feasible assumptions about quasi-steady-state optimality are all that is necessary to predict reaction rates for the entire system. Combinatorial enzyme deletion phenotypes can be explored systematically by constraining specific enzyme-reaction fluxes to zero (for example, Edwards and Palsson 2000; Forster et al. 2003). This approach provides reasonable approximations of genomewide biochemical processes in several model organisms (Edwards and Palsson 2000; Duarte et al. 2004; Bro et al. 2006; Hjersted et al. 2007; Oh et al. 2007; Resendis-Antonio et al. 2007; Becker and Palsson 2008; Motter et al. 2008).

Constraint-based methods provide a solid mathematical foundation for identifying important properties of biochemical pathways. Under a certain set of stoichiometric constraints, metabolic networks can be decomposed into a finite number of elementary flux modes (EFMs) or extreme pathways (Papin et al. 2002). The properties of EFMs have important biological implications. EFMs are the unique set of nondecomposable pathway flows for a given biochemical network (Schuster et al. 2000). In biological terms, EFMs are modular units of pathway function—minimal sets of enzymes required to catalyze whole metabolic reactions. Because metabolic pathways are highly integrated, the number of possible pathways connecting reactants and products grows exponentially. Thus EFM analysis is computationally tractable only for individual pathways or small metabolic subnetworks (Klamt and Stelling 2002).

Past metabolic engineering efforts in eukaryotic microbes have sought to control flux through anaerobic pathways for increased production of metabolites produced by fermentation. These include lactate (van Maris et al. 2004; Ishida et al. 2006), malate (Zelle et al. 2008), isoprenoids (Shiba et al. 2007; Herrero et al. 2008; Kizer et al. 2008), glycerol (Geertman et al. 2006; Cordier et al. 2007), and ethanol (Alper et al. 2006; Bro et al. 2006), among others. Although nonfermentative by-products represent a class of biologically interesting and commercially attractive small molecules, efforts aimed at engineering microbes for increased production of these metabolites are comparatively infrequent.

Reactions that produce the major one-carbon donors serine, glycine, and formic acid are often duplicated in the cytoplasm and mitochondrion (Christensen and Mackenzie 2006). Flux through these reactions is generally oxidative in the mitochondria and reductive in the cytoplasm; however, C1 metabolic pathways are under considerable regulatory control and can be adapted to specific genetic backgrounds and growth conditions (Kastanos et al. 1997; Piper et al. 2000). Two groups have independently shown that C1 enzymes are controlled dynamically by glycine at the transcriptional level. Upon glycine withdrawal many enzymes involved in C1 metabolism are strongly repressed, a regulatory event that requires the transcription factor Bas1 (Subramanian et al. 2005). Under conditions of glycine induction Gelling et al. (2004) noticed a similar pattern of C1 enzyme differential expression; however, Bas1 was not required for the observed effect in this case. In both of these studies the intact cytosolic serine hydroxymethyltransferase Shm2 (EC 2.1.2.1) was necessary for glycine-dependent changes in C1 enzyme expression (Gelling et al. 2004; Subramanian et al. 2005). Although contradicting evidence exists, results reported thus far demonstrate the dynamic control of C1 metabolism in eukaryotes.

To investigate metabolic engineering strategies for controlling biosynthetic flux through a nonfermentative pathway, we chose to construct strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that increase flux through C1 metabolism. We chose a constraint-based modeling approach to develop genetic engineering strategies leading to increased production of formic acid. We experimentally validated our modeling strategy and identified specific transcriptional control mechanisms that govern C1 metabolism in the engineered strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constraint-based modeling and in silico gene deletion:

The validated, genome-scale metabolic model S. cerevisiae iND750 previously described by Duarte et al. (2004) was used to model the fully compartmentalized yeast metabolic network. The flux balance analysis (FBA) optimization problem was formulated as described previously (Varma and Palsson 1994) in the GNU MathProg language and solved with custom-generated C code (available upon request), implementing the GNU linear programming (LP) kit (GLPK) available at ftp://aeneas.mit.edu/pub/gnu/glpk.

Specifically, we defined quasi-steady-state conditions using the yeast stoichiometric matrix S and unknown flux vector v,

|

with maximization of growth rate (μ) as the objective function for FBA:

|

Thermodynamic constraints in iND750 are derived from the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and associated with individual reactions to define  and

and  , which are the upper and lower bounds of each reaction i. We modeled 20 mmol gDW−1 hr−1 constant glucose uptake, nutrient uptake fluxes appropriately constrained to simulate synthetic complete media including the addition of serine (Figure 1A; supporting information, Table S1), oxygen uptake flux that was either fixed to 0 mmol gDW−1 hr−1 or left unconstrained to simulate anaerobic or aerobic growth conditions, respectively, and internal fluxes constrained to {0, ∞} or left unconstrained to simulate irreversible or reversible reactions, respectively. It is important to note that multiple optimal solutions are possible in which the objective function constraint is satisfied (Lee et al. 2000; Phalakornkule et al. 2001). We sampled alternative optimal solutions for the mutant strains predicted to increase flux to formic acid by relaxing the directionality constraint of individual reactions (Lee et al. 1997). Results from this analysis indicated some flexibility in the formic acid biosynthetic pathway; however, the three mutations alt2, fum1, and zwf1 were consistently associated with significant increases in formic acid secretion, with a minimum secretion rate of 53.65 mmol gDW−1 hr−1 (other data not shown).

, which are the upper and lower bounds of each reaction i. We modeled 20 mmol gDW−1 hr−1 constant glucose uptake, nutrient uptake fluxes appropriately constrained to simulate synthetic complete media including the addition of serine (Figure 1A; supporting information, Table S1), oxygen uptake flux that was either fixed to 0 mmol gDW−1 hr−1 or left unconstrained to simulate anaerobic or aerobic growth conditions, respectively, and internal fluxes constrained to {0, ∞} or left unconstrained to simulate irreversible or reversible reactions, respectively. It is important to note that multiple optimal solutions are possible in which the objective function constraint is satisfied (Lee et al. 2000; Phalakornkule et al. 2001). We sampled alternative optimal solutions for the mutant strains predicted to increase flux to formic acid by relaxing the directionality constraint of individual reactions (Lee et al. 1997). Results from this analysis indicated some flexibility in the formic acid biosynthetic pathway; however, the three mutations alt2, fum1, and zwf1 were consistently associated with significant increases in formic acid secretion, with a minimum secretion rate of 53.65 mmol gDW−1 hr−1 (other data not shown).

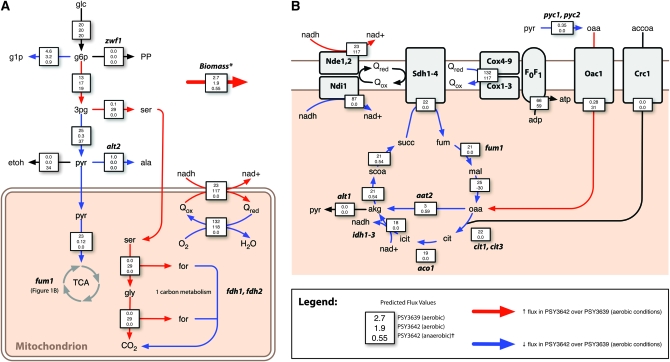

Figure 1.—

Constraint-based modeling predicts mutations that redirect flux through serine/glycine biosynthesis and C1 metabolism, leading to increased aerobic formic acid secretion. Arrows denote key cytoplasmic (A) and mitochondrial (B) reactions for which predicted flux is higher (red) or lower (blue) in PSY3642 compared to PSY3639 (see text for details). Boxes superimposed over arrows contain flux values for three simulated conditions: (i) PSY3639 (aerobic), (ii) PSY3642 (aerobic), and (iii) PSY3642 (anaerobic)(†, anaerobic flux values, given in A only). Flux values are relative to a constant glucose uptake rate of 20 mmol gDW−1 hr−1. See Table S2 for a complete list of predicted fluxes and metabolites required for growth (*, the biomass equation, given in Table S2). Abbreviations (not provided in the text): glc, glucose; g1p, glucose-1-phosphate; g6p, glucose-6-phosphate; ser, serine; etoh, ethanol; pyr, pyruvate; ala, alanine; gly, glycine; for, formate; nad, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; Q, quinone; accoa, acetyl-CoA; cit, citrate; isocit, isocitrate; succ, succinate; fum, fumarate; and mal, malate.

To identify the maximum theoretical yield for formic acid production we substituted formic acid secretion for biomass in the objective function. All the other constraints were appropriate for external exchange and aerobic growth. Maximizing this objective resulted in Equation 1, which can be considered the “type I” through pathway for formic acid biosynthesis (Schilling et al. 2000).

Several efficient algorithms have been developed for identifying a single solution of optimal gene knockouts (for example, Burgard et al. 2003). We chose an iterative simulation strategy as we were interested in all combinations of gene knockouts predicted to affect C1 metabolism and formic acid production, including solutions that might be considered suboptimal under formal definitions. By constraining the fluxes of individual sets of ≤3 nonessential genes to zero and reevaluating the system using LP we simulated metabolic phenotypes for >4 million gene combinations in reasonable time frames (<4 hr on an x86-64 processor running Linux version 2.6.15-51). Our knockout simulation protocol is summarized with the following pseudocode:

|

Yeast strains and plasmids:

PSY3642 was derived from the fdh1 fdh2 parental strain PSY3639 (Overkamp et al. 2002) by iterative gene replacement (Guldener et al. 1996). Briefly, LoxP-KanMX gene deletion cassettes for ALT2, FUM1, and ZWF1 were generated by PCR, using primers with 45 bp of flanking homology and pUG6 as template (Guldener et al. 1996). KanMX+ transformants were selected on YPD plates containing 200 mg/liter G418 (geneticin). After confirming integration by single-colony PCR, G418 sensitivity was reestablished for subsequent gene replacement by expressing Gal4-Cre from pSH65 (Guldener et al. 1996) and selecting transformants on YPD plates containing 50 mg/liter phleomycin. Correct excision of LoxP-KanMX was confirmed by single-colony PCR.

The biobrick assembly method (Knight 2003; Phillips and Silver 2006) was used to generate the expression plasmid pRS410a consisting of (ordered 5′–3′) the yeast CUP1 promoter, the yeast Kozak sequence, the catalytic domain of SerA (cloned by PCR from E. coli genomic DNA), in-frame fusion of the V5 epitope, the stop codon, and the yeast ADH1 terminator. The flanking biobrick restriction sites XbaI and SpeI were used to subclone the expression fragment into pRS410 (Addgene). Yeast transformants were selected on YPD plates containing 200 mg/liter G418 and cultured with the same concentration of drug in synthetic complete media containing 2% glucose and 0.3 mm CuSO4. Primer sequences used in this study are shown in Table S3.

Metabolite determination:

Extracellular formic acid and ethanol measurements were made using spectrometric enzymatic assays at 340 nm according to the manufacturer's specifications (R-Biopharm). Yeast cultures were grown in synthetic complete media with 2% glucose under batch conditions in baffled (aerobic) or round bottom (anaerobic) Erlenmeyer shaker flasks. Anaerobic cultures were grown in sparged media under nitrogen gas.

Samples for intracellular metabolite measurements were prepared, using several methods as conceptual frameworks (Lange et al. 2001; Visser et al. 2004; Canelas et al. 2008; Sporty et al. 2008). Briefly, 20-ml samples were quickly drawn at a log phase (cell density of 0.4–0.6 OD600) and immediately quenched in 32 ml cold 60% (v/v) methanol. A frozen binary solution of 60% (v/v) ethanol was used to maintain the yeast samples and quenching solution at −40°. Two subsequent washes were performed using the cold quenching solution, followed by cell lysis at 4° using a glass bead beater in the presence of 75% (v/v) ethanol to precipitate proteins. Samples were lyophilized overnight, resuspended in 100 μl anaerobic water, and centrifuged twice before use. The supernatant was stored at −80° until processing via HPLC.

HPLC measurements were performed using a Waters 2695 HPLC separation module fitted with a Luna C18 5-μm column, 250 × 4.5 mm (Phenomenex). Samples of 75–85 μl were injected and eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, starting with 100% mobile phase buffer A and gradually increasing to 100% mobile phase buffer B (Di Pierro et al. 1995). Specifically, the relative fraction of buffer B in the mobile phase was increased at a rate of 15%/min until 60%, at 0.6%/min until 80%, during which the majority of separation occurred, and at 20%/min until 100% was reached. Buffer A contained 10 mm tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, 10 mm KH2PO4, and 0.25% methanol at pH 7.0 (Di Pierro et al. 1995). Buffer B contained 2.8 mm tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, 100 mm KH2PO4, and 30% methanol at pH 5.5 (Di Pierro et al. 1995). NAD was analyzed at 260 nm, and NADH was analyzed at 340 nm using a photodiode array detector (Waters 996) (Di Pierro et al. 1995; Sporty et al. 2008). Standard curves of specific metabolites were performed to enable quantification.

Gene expression profiling and analysis:

Poly(A) mRNA was obtained in biological triplicate by trizol extraction (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from early log-phase (OD600 = 0.4) yeast grown aerobically. cDNA was generated from PSY3642 and PSY3639 by reverse transcription, differentially labeled with Cy3 or Cy5, respectively (one sample was processed with the labeling reversed to minimize artifacts introduced by incorporation bias), and hybridized to whole-genome cDNA microarrays (http://www.microarray.ca/). Array scans were analyzed with GenPix software and Rosetta Resolver (complete data are available in Table S4).

Gene ontology enrichment was obtained using GoStat (http://gostat.wehi.edu.au/) with Benjamini false discovery to correct for multiple hypothesis testing. The query set for enzyme annotation analysis was limited to those gene identities with represented reactions in iND750 for which flux values were calculated.

Hierarchical clustering was applied to genomewide expression profiles of PSY3642 (compared to PSY3639) and other genetic knockout strains (excluding overexpression and drug treatment conditions) in the compendium described by Hughes et al. (2006). Routines were implemented in R (http://www.r-project.org/) with a Euclidean distance metric and Ward's minimum variance clustering algorithm (Murtagh 1985).

We used YEASTRACT-DISCOVERER (http://www.yeastract.com/) to find transcription factor binding motif enrichments in the promoter regions of genes with significant activation (P < 0.01) greater than twofold (Teixeira et al. 2006; Monteiro et al. 2008).

Phenotypic analysis:

Mitotracker Red CMXRos and Mitotracker CM-H2XRos (Invitrogen) were used to stain mitochondria. CMXRos selectively stains mitochondria and fluoresces in the red portion of the spectrum. CM-H2XRos is a reduced version of CMXRos and fluoresces only when oxidized in respiring mitochondria (Ludovico et al. 2002). Overnight yeast cultures were resuspended in YEPD media containing either 1 μm of CMXRos or 3 μm CM-H2XRos and incubated at 30° for 30 min prior to imaging.

Antibodies and Western blotting:

PVDF membranes were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.25% Tween-20 (PBST) and 5% nonfat dry milk, probed with mouse monoclonal primary antibodies against actin (Chemicon) or V5 (Sigma, St. Louis) and appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson), washed with PBST, and developed with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ).

RESULTS

Pathway analysis of C1 metabolism in yeast:

We performed limited pathway analysis of the yeast metabolic network to identify Equation 1, which represents the complete oxidation of glucose into formic acid (see materials and methods):

|

(1) |

Due to the quasi-steady-state assumption, individual reaction rates in Equation 1 are likely to be correlated during C1-mediated formic acid secretion, a condition that strongly suggests coordinated regulation of enzymes in this pathway (Schuster et al. 2002). Coregulation of enzymes involved in glycolysis is well characterized; however, it is not fully understood if and how endogenous transcriptional programs coordinate C1 metabolism to affect formic acid biosynthesis.

Theoretically, maximum flux through Equation 1 would result in four formic acid molecules per glucose, a twofold yield increase compared to PFL-catalyzed reactions associated with mixed acid fermentation in E. coli (Birkmann et al. 1987). This may have important biotechnological applications for biofuel production. Assuming 100% conversion of exogenous formic acid into hydrogen, a two-step conversion process using endogenous hydrogenases in E. coli could result in 4 H2 per glucose (Yoshida et al. 2005; Waks and Silver 2009). Formic acid production in yeast is relatively low and secretion is essentially nonexistent (Blank et al. 2005); however, there is reason to believe that engineering C1 metabolism to produce high levels of formic acid is achievable. Various insect species regulate homologous pathways to produce large quantities of formic acid for the purposes of defense and communication (Hefetz and Blum 1978).

A model-driven metabolic engineering strategy to increase endogenous formic acid secretion:

To formulate genetic engineering strategies leading to increased production of formic acid in yeast, we used the compartmentalized metabolic model iND750 (Duarte et al. 2004) and an iterative gene knockout simulation strategy to identify combinatorial enzyme deletions predicted to significantly increase formic acid secretion (see materials and methods for details). As an exhaustive screen through all triple-knockout combinations would have been experimentally infeasible, we used FBA to screen combinatorial knockouts in silico. We identified several gene knockout combinations, which predicted nonzero secretion rates of formic acid (Table 1). In all cases eliminating the NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase (FDH) reaction (EC 1.2.1.2) was required for secretion of formic acid. This is not surprising as FDH is thought to protect yeast from formic acid toxicity by catalyzing its irreversible oxidation to CO2 (Overkamp et al. 2002).

TABLE 1.

Gene combinations affecting C1 metabolic flux and formic acid secretion identified through in silico knockout simulation

| Rank | Genotype | Efficiency (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | fdh1 fdh2 alt2 fum1 zwf1 | 72.3 |

| 2 | fdh1 fdh2 aat2 fum1 zwf1 | 72.2 |

| 3 | fdh1 fdh2 cat2 fum1 zwf1 | 72.0 |

| 4 | fdh1 fdh2 cat2 fum1 rpe1 | 71.7 |

| 5 | fdh1 fdh2 cat2 fbp1 fum1 | 30.5 |

| 6 | fdh1 fdh2 cat2 yat2 slc1 | 2.4 |

| 7 | fdh1 fdh2 cat2 yat2 cho1 | 2.3 |

| 8 | fdh1 fdh2 cat2 yat2 alt2 | 1.2 |

One hundred percent efficiency is defined as four formic acid molecules per glucose.

We chose to proceed by constructing the mutant strain predicted to have the highest formic acid production efficiency (Table 1). In addition to FDH1 and FDH2, three other genes were targeted for mutation by serial gene replacement (Table 2): ALT2, a putative cytoplasmic alanine transaminase (EC 2.6.1.2); FUM1, fumarase (EC 4.2.1.2); and ZWF1, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.49). Unlike FDH, these three genes (reactions) function across subcellular compartments at distantly located positions within the metabolic network and are not obviously associated with formic acid biosynthesis or C1 metabolism.

TABLE 2.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotypea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PSY3639 | fdh1(41, 1091)∷loxP fdh2(41, 1091)∷loxP | Overkamp et al. (2002) |

| PSY3640 | zwf1∷loxP | This study |

| PSY3641 | zwf1∷loxP fum1∷loxP | This study |

| PSY3642 | zwf1∷loxP fum1∷loxP alt2∷loxP | This study |

| PSY3650 | zwf1∷loxP fum1∷loxP alt2∷loxP rtg1∷KanMX | This study |

| PSY3653 | fum1∷KanMX | This study |

All mutations are present in the CEN.PK113-7D MATa URA3 HIS3 LEU2 TRP1 MAL2 SUC2 genetic background. PSY3640–PSY3642, PSY3650, and PSY3653 are derived from PSY3639.

A predicted increase in flux to formic acid is achieved through nonintuitive interactions between alt2, fum1, and zwf1 (Figure 1). Although the protein encoded by FUM1 is both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial (Stein et al. 1994), the model predicted several effects specifically related to its mitochondrial function: (i) decoupling of the respiratory chain resulting in (ii) decreased flux into the key TCA cycle intermediate alpha-ketoglutarate (AKG) and (iii) increased flux into 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG). Flux through PGDH compensates for loss of FUM1 by balancing 3PG and generating the cytoplasmic AKG—via phosphoserine transaminase (PST) (EC 2.6.1.52) that is necessary for growth. PST catalyzes the transamination of 3-phosphonooxypyruvate, using glutamate as a cofactor, which is balanced by eliminating the competitive reaction associated with ALT2. Removing ZWF1 eliminates direct flux to the pentose phosphate pathway, thereby increasing flux into 3PG, which is balanced by serine/glycine biosynthesis, leading to the complete oxidation of glucose into formic acid, carbon dioxide, and biomass. In the absence of FDH1 and FDH2, intracellular formic acid is balanced by secretion into the media.

Consistent with Equation 1, the FBA model predicts that formic acid secretion is oxygen dependent. Excess reducing equivalents in the form of eight cytoplasmic NADHs are balanced aerobically rather than using an organic substrate as a final electron acceptor. Accordingly, the model predicts increased flux through reactions catalyzed by the external mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenases Nde1 and Nde2 as well as downstream electron transport chain components.

Model validation confirms that elevated formic acid secretion requires aerobic respiration:

Results comparing formic acid secretion in PSY3639 and PSY3642 revealed broad qualitative agreement with two important model predictions: (i) mutations in alt2, fum1, and zwf1 interacted in a combinatorial manner to enhance formic acid production and (ii) this enhancement was oxygen dependent.

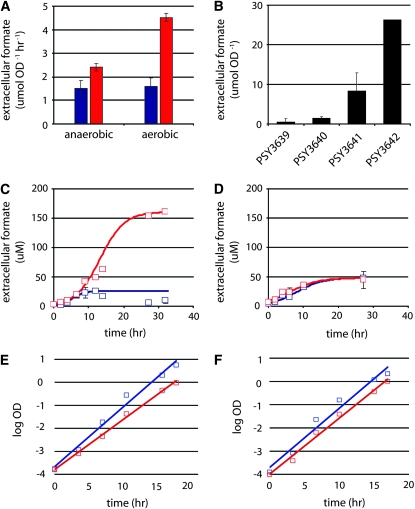

The rate of formic acid secretion measured during log-phase growth was significantly (3-fold) higher in PSY3642 compared to PSY3639 (P < 0.01) and this change was dependent on aerobic growth conditions (Figure 2A). Furthermore, formic acid secretion increased nonlinearly with enzyme loss, indicating a cumulative increase in formic acid production that resulted from eliminating combinatorial interactions between the deleted enzymes (Figure 2B). Because FBA models flux at quasi-steady state, derived predictions are generally applicable only during log-phase growth. However, comparisons of PSY3642 and PSY3639 made after saturation (>30 hr of continuous growth) revealed a striking 16.5-fold increase in extracellular formic acid concentration (Figure 2C). Consistent with model predictions, this difference in total formic acid secretion was observed only under aerobic growth conditions (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.—

Experimental validation of model predictions. (A) Formic acid secretion rates under aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions; (B) total extracellular formic acid production for several strains, including PSY3639 (blue) and PSY3642 (red), grown aerobically (C) and anaerobically (D). Growth rates are given for PSY3639 and PSY3642 grown aerobically (E) and anaerobically (F). Genotypes for strains in B are listed in Table 2. Fit curves in C–F were calculated using logistic regression. Data represent the average of three biological replicates ± SD. A paired two-tailed t-test was used to test for statistical significance in A.

Under aerobic conditions, the model predicted a slight growth disadvantage in PSY3642 attributed to diversion of carbon flux away from biomass into formic acid synthesis (Figure 1A) whereas under anaerobic conditions the predicted growth rates for the two strains were equivalent (data not shown). Consistent with these predictions, under aerobic conditions we observed a substantial growth defect (0.17 hr−1 vs. 0.26 hr−1) (Figure 2E). Under anaerobic conditions, the two strains had comparable growth rates (0.23 hr−1 vs. 0.24 hr−1) (Figure 2F). One simple explanation for the exacerbated growth defect observed in PSY3642 was toxicity. However, the addition of high concentrations of extracellular formic acid up to 100 mm was well tolerated and did not affect relative rates of growth or cell lysis in either strain (data not shown).

Engineering endogenous C1 metabolism induces the retrograde response:

To gain insight into potential transcriptional mechanisms underlying increases in formic acid secretion, we performed gene expression analysis comparing PSY3639 and PSY3642 by competitive hybridization to whole-genome cDNA microarrays (see materials and methods). Bioinformatics analysis of these data implicated specific transcriptional responses resulting from manipulating C1 metabolism for formic acid production. An initial assessment of genes with the highest differential expression (some as high as 56-fold) revealed a varied transcriptional response involving disparate biological processes, including glucose repression (GCR1 and RGR1), mitochondrial function (ATP15, FMT1, RPM2, and QCR10), telomere maintenance (ESC8, RSC58, and SIR3), and C1 metabolism (ADE4, ATP2, ATP7, FOL1, FMT1, and POR1) (Table 3). Significant gene ontology enrichments were identified for enzymes primarily involved in mitochondrial-associated reactions (P = 0.01), including TCA metabolic processes (P = 0.02) and oxidative phosphorylation (P = 0.005). These results are generally consistent with glycine-induced transcriptional changes observed for C1 metabolic enzymes (Gelling et al. 2004).

TABLE 3.

Differentially expressed genes in PSY3642

| Gene | ORF | Function | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADE4 | YMR300C | Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase | −56.6 |

| ATP15 | YPL271W | ATP synthase epsilon subunit | −12.7 |

| FMT1 | YBL013W | Formyl–methionyl–tRNA transformylase | −8.5 |

| ESC8 | YOL017W | Telomeric and mating-type locus silencing | −8.2 |

| QCR10 | YHR001W-A | Ubiqunol–cytochrome c oxidoreductase complex | −7.7 |

| POR1 | YNL055C | Outer mitochondrial membrane porin | −4.1 |

| ATP7 | YKL016C | ATP synthase D subunit | −3.3 |

| ATP2 | YJR121W | F(1)F(0)-ATPase complex β-subunit | −2.2 |

| SER3 | YER081W | Catalyzes the first step in serine biosynthesis | 1.8 |

| ADH3 | YMR083W | Alcohol dehydrogenase isoenzyme | 1.9 |

| RTG1 | YOL067C | Interorganelle communication | 4.7 |

| CRC1 | YOR100C | Mitochondrial carnitine carrier | 4.8 |

| FOL1 | YNL256W | Folic acid synthesis | 5.7 |

| IDH1 | YNL037C | Mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenase | 5.8 |

| RGR1 | YLR071C | Transcriptional regulation of diverse genes | 6.6 |

| IDH2 | YOR136W | NAD+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase | 6.6 |

| OAC1 | YKL120W | Mitochondrial oxaloacetate carrier | 7.0 |

| SIR3 | YLR442C | Silencing at HML, HMR, and telomeres | 9.9 |

| GCR1 | YPL075W | Positive regulator of the enolase | 11.7 |

| RSC58 | YLR033W | Chromatin remodeling complex subunit | 12.1 |

| RPM2 | YML091C | Mitochondrial precursor tRNAs | 44.7 |

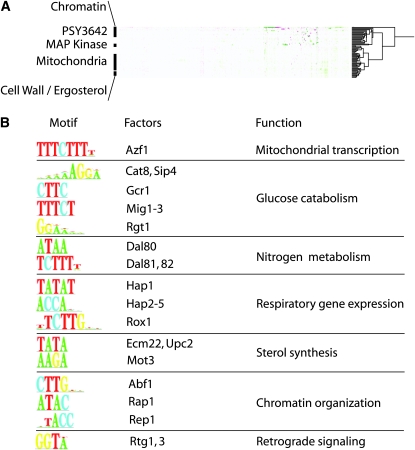

To identify similar patterns of expression in other mutant backgrounds, we compared the gene expression profile of PSY3642 with the compendium generated by Hughes et al. (2006). Using hierarchical clustering of these data, we identified patterns of expression that were similar to the profile observed in PSY3642 (Figure 3A). Each of these profiles was associated with a particular conditional experiment. We chose to limit our analysis to gene expression profiles generated from gene deletions. PSY3642-similar expression patterns were associated with specific gene mutations affecting chromatin function and general transcriptional regulation, MAP kinase signal transduction (swi6, sst2, dig1, and dig2), mitochondrial function (rip1, qcr2, kim4, etc.), and cell wall (gas1, anp1, fks1, etc.) and ergosterol biosynthesis (erg2 and erg3). Interestingly, single deletions in SSN6, RPD3, or TUP1—components of a well-characterized transcriptional silencing complex—resulted in the differential expression of >180 genes (Smith and Johnson 2000; Green and Johnson 2004), many of which were also differentially expressed in PSY3642. Motif enrichments in the promoters of upregulated genes implicated transcription factors associated with several biological processes (Figure 3B). Included in this set were Rtg1 and Rtg3, two transcription factors that mediate mitochondria-to-nucleus retrograde signaling in response to severe mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 3.—

Expression analysis of PSY3642. (A) Hierarchical clustering of PSY3642 and other mutant strain expression profiles are represented as a clustering diagram (dendogram). For clarity, only a portion (approximately one-third) of the complete dendogram is shown. The cluster subtrees are ordered and displayed nonrandomly such that similar expression profiles appear closer together. Labels for several functional categories reflect the tendency for strains with comparable genetic deficiencies to exhibit similar patterns of gene expression (Hughes et al. 2006). PSY3642 clusters close to strains with mutations affecting chromatin function, MAP kinase signaling, and mitochondrial function (see text for details). (B) DNA-binding motifs (P < 10−10) within the promoters of activated genes in PSY3642 are represented as sequence logos (left column) along with cognate transcription factors (middle column) and identified regulatory roles (right column).

Retrograde signaling is typically associated with the petite phenotype caused by loss of mitochondrial DNA (ρ0) (Butow and Avadhani 2004). Cells sense mitochondrial dysfunction and implement systemic changes in gene expression to compensate for mitochondria-associated metabolic deficiencies (Liu and Butow 2006). In ρ0 yeast, Rtg1-mediated retrograde signaling is exclusively post-translational: phosphorylated Rtg1 translocates to the nucleus without any change in the abundance of RTG1 transcript itself; however, in PSY3642 expression of RTG1 is significantly upregulated (Table 3). This suggests an alternative (transcriptional) mode of Rtg1-mediated retrograde signaling that is absent in ρ0 yeast.

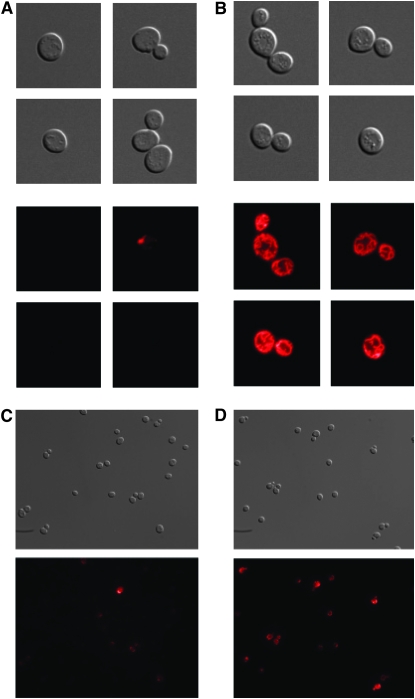

Using mitochondria-specific vital stains we confirmed the mitochondrial defect implied by induced expression of RTG1 and transcriptional induction of retrograde responsive genes. Whereas PSY3639 resembled wild-type yeast with regard to mitochondrial abundance, morphology, and membrane potential, analysis of PSY3642 revealed a heterogeneous population of cells that were depleted in functional mitochondria (Figure 4). Microscopic analysis revealed a dramatic reduction in both the total number of mitochondria and their associated respiratory capacity (compare Figure 4, A and C, to Figure 4, B and D). This effect was primarily evident in PSY3642, with strains PSY3640 and PSY3641 resembling the parent strain PSY3639 (Figure S1). These data, along with experiments that show elevated formic acid secretion exclusively under oxygenated growth conditions (Figure 2), indicate that mitochondrial function and respiratory capacity are severely diminished but not completely abolished in PSY3642.

Figure 4.—

Phenotypic analysis of PSY3642 reveals mitochondrial dysfunction. Total mitochondria were labeled in PSY3642 (A) and PSY3639 (B) and single cells were imaged at 100× magnification with DIC (top panels) and epifluorescence (bottom panels). Oxidation of Mitotracker CM-H2XRos was measured to indicate respiratory capacity in PSY3642 (C) and PSY3639 (D). Cells were imaged at 40× magnification with DIC (top panels) and epifluorescence (bottom panels). Exposure times were 40 msec in all cases.

ρ0 yeast upregulate several genes to provide stoichiometric amounts of oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA to drive the TCA cycle in the presence of respiratory deficiency (Epstein et al. 2001). Several of these genes are also upregulated in PSY3642, including PYC1, OAC1, and CRC1, as well as the NAD-dependent TCA cycle enzymes IDH1 and IDH2 (Table 3). As the FBA model predicted very little flux through the TCA cycle, a retrograde responsive increase in flux through these reactions represents an unanticipated (and unforeseeable) adaptation to manipulating C1 metabolism. We constructed an rtg1 mutation in the PSY3642 genetic background (PSY3650) and observed a 25% increase in formic acid secretion (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Quantification of Rtg1-mediated formic acid secretion

| Strain | Formic acid (mm)a | Ethanol (mm)a |

|---|---|---|

| PSY3639 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 155 ± 19 |

| PSY3642 | 0.16 ± 0.004 | 178 ± 14 |

| PSY3650 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | NA |

Data are given as the average of three biological replicates ± SD.

In the presence of severe respiratory deficiency, increased TCA cycle flux would be coupled to increased flux through NAD-dependent reactions (for example, through increased expression of IDH1 and IDH2). As a result the cell would require some biochemical mechanism to regenerate NAD and maintain redox homeostasis. ρ0 yeast upregulate the expression of glycerol-3-phosphate and alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes (Gpd2 and Adh1-7) as part of the retrograde response. These pathways reoxidize NADH in the absence of competent oxidative capacity (Epstein et al. 2001). In PSY3642 there is no significant change in expression of GPD2, ADH1, or ADH4–7. ADH3, a mitochondrial ethanol-acetaldehyde redox shuttle (Bakker et al. 2000), is induced twofold; however, we observed no detectable difference in ethanol production between PSY3642 and PSY3639 (Table 4). To test the hypothesis that flux through NAD-dependent reactions increases in PSY3642 we measured intracellular NADH/NAD ratios directly (see materials and methods). We observed a significant increase in intracellular NADH relative to NAD, which was eliminated in rtg1 mutants (Figure 5). Together, these results support the hypothesis of an Rtg1-mediated increase in flux to the TCA cycle, which increases the NADH/NAD ratio and diverts organic substrate away from C1 metabolism and formic acid biosynthesis.

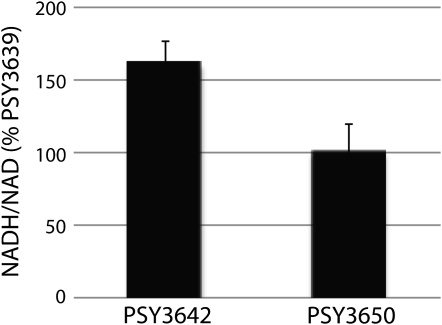

Figure 5.—

Increase in NADH/NAD in PSY3642 NADH/NAD ratios for PSY3642 and PSY3650 is given as percentage of PSY3639. Data represent the average of four biological replicates ± SD. Compared to that in PSY3639, NADH accumulated significantly in PSY3642 (P = 0.001) but not in PSY3650 (P = 0.46). Statistical significance was assessed by testing the null hypothesis m = 100% vs. the alternative m > 100%, assuming normally distributed sample data.

Increased flux to formic acid is modulated by coordinated expression of C1 pathway enzymes:

According to our pathway analysis of C1 metabolism, the enzymes associated with Equation 1 are both necessary and sufficient to catalyze the full oxidation of glucose into formic acid given proper regulatory constraints that serve to channel flux through this pathway. Transcriptional coregulation of the upstream portion of Equation 1 (glycolysis) is well characterized. By combining pathway analysis and transcriptional data, we tested the hypothesis that downstream reactions occurring after the glycolytic branch point PGDH are also subject to coregulation. We sought to identify endogenous transcriptional programs responsible for increased C1 metabolic flux in PSY3642.

A closer look at relative mRNA abundance for enzymes involved in formic acid biosynthesis revealed an interesting pattern of endogenous differential expression (Figure 6B). Relative to the branch point isozyme Ser3 (PGDH), differential expression of downstream enzymes is correlated to their relative position in the pathway, with the lowest expression change associated with the terminal enzyme Mis1. Linear regression indicates that 52% of the variance in differential expression of C1-associated enzymes is explained simply by their relative topological position in the reaction pathway (P = 0.02). Interestingly, this pattern of differential expression implicates a recognized mechanism of endogenous metabolic control termed multisite modulation, where coordinated expression of several enzymes modulates flux through entire metabolic pathways (Fell 1997). This provides experimental evidence that C1 enzymes constitute a module of pathway function in PSY3642.

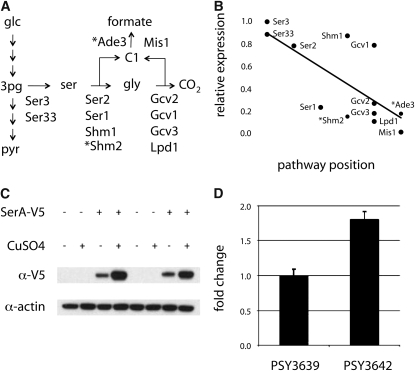

Figure 6.—

Flux to formic acid is controlled by PGDH and the coordinated expression of all pathway enzymes. (A) The subnetwork of serine–glycine–formate biosynthesis with reaction arrows that represent composites of several biochemical interconversions labeled with relevant enzymes. The cytoplasmic enzymes involved in converting serine into formic acid (Shm2 and Ade3) are denoted with asterisks. (B) Differential expression of enzymes in A were normalized to Ser3 and plotted according to their pathway position. Multisite modulation for enzymes in the formic acid biosynthetic pathway is indicated by linear regression (solid line, R2 = 0.52) and corrected Spearman's ranked order correlation (ρ = −0.72, P = 0.02). (C) Levels of the SerA fusion protein (relative to actin) were unaffected by genetic background and induction conditions. (D) Expressing SerA in PSY3642 caused a significant increase in formic acid secretion under inducing conditions. Each transformed strain was normalized to the empty vector control plasmid pRS410a. Data in D represent the average of three biological replicates ± SD. We assessed statistical significance using a paired two-tailed t-test (P = 0.002).

The transcriptional data we obtained suggested that increased expression of Ser3 was causally associated with increased flux to formic acid (Table 3). Generally, overexpressing branch point enzymes rarely affects their associated flux to any significant degree. This is due, in part, to feedback inhibition by downstream metabolites (Fell 1997). Indeed, PGDH is allosterically inhibited by serine and, as a consequence, it has very low flux control in mammalian tissue (; Fell and Snell 1988; Bell et al. 2004; Thompson et al. 2005). To test the hypothesis that PGDH may control formic acid synthesis in PSY3642, we generated a plasmid for inducible overexpression of the catalytic domain of E. coli SerA (pRS410a), a well-characterized functional homolog of yeast Ser3. Expression levels of the fusion protein were not affected by strain-specific genetic backgrounds or transcriptional induction (Figure 6C). Consistent with previous experiments in mammalian tissues, SerA had no effect on flux to formic acid in PSY3639; however, SerA expression in PSY3642 resulted in an 86% increase in extracellular formic acid concentration (Figure 6D). This result is consistent with endogenous induction of Ser3 in PSY3642 and suggests that PGDH has a positive flux control coefficient in this strain.

DISCUSSION

Our goal in this work was to test an FBA-based strategy for engineering C1 metabolism in yeast to increase endogenous formic acid production and describe cellular mechanisms responsible for regulating this important metabolic pathway. FBA and gene knockout simulations identified a nonintuitive combination of genes (ALT2, FUM1, and ZWF1), which individually had no obvious role in formic acid biosynthesis (Figure 1). On the basis of the model predictions, we constructed the quintuple knockout alt2 fdh1 fdh2 fum1 zwf1 and showed significant oxygen-dependent formic acid secretion in the engineered strain, during both log-phase (Figure 2A) and stationary-phase growth (Figure 2, C and D). Further, maximum formic acid secretion required all five enzyme deletions predicted by the model (Figure 2B). Although formic acid is an essential intracellular metabolite, it is not secreted in detectable levels in wild-type yeast (McNeil et al. 1996; Blank et al. 2005). Thus, our results demonstrate the successful application of an FBA-based strategy for microbial production of formic acid under aerobic growth conditions. More generally, these data support the predictive potential for this approach in deriving strategies aimed at engineering nonfermentative metabolic pathways that integrate across subcellular compartments in eukaryotic microbes.

To gain insights into the regulatory events that result from manipulating formic acid biosynthesis, we supplemented model predictions and validation experiments with gene expression and phenotypic analyses. From these data we identified (i) a significant transcriptional response involving multiple cellular processes (Table 3 and Figure 3); (ii) activation of retrograde signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and diminished respiratory capacity (Table 4 and Figures 4 and 5); and (iii) transcriptional regulatory events that lead to the coordinated expression of enzymes involved in C1 metabolism (Figure 6). Upon close inspection, these data indicate specific mechanisms of metabolic regulation that result from unanticipated adaptive responses to manipulating C1 metabolic flux.

Several lines of evidence strongly suggest activation of the retrograde response in PSY3642 cells. In terms of global gene expression pattern, PSY3642 is most similar to strains with mutations in genes that are directly involved in retrograde signaling (Figure 3A). These include Rpd3, Ssn6, and Tup1, a well-characterized corepressor complex (Malave and Dent 2006), and Yat2, a carnitine acetyl-CoA transferase involved in transporting activated acetate into respiratory deficient mitochondria (Epstein et al. 2001; Swiegers et al. 2001; Liu and Butow 2006). Interestingly, Yat2 was identified in our original in silico knockout screen for enzymes that affect C1 metabolic flux (Table 1).

In petite cells Ssn6–Tup1 is converted from a transcriptional corepressor complex into a coactivator, which upregulates gene expression through direct interaction with Rtg3 (Conlan et al. 1999), one of three transcription factors primarily responsible for retrograde responsive gene activation in yeast (Rothermel et al. 1997). DNA binding motifs for Rtg1 and Rtg3 are overrepresented in the promoters of activated genes in PSY3642 (Figure 3D) while RTG1 expression itself is increased almost fivefold (Table 3). These results strongly implicate retrograde regulatory transcription factors as specific modulators of gene activation and metabolic activity in PSY3642. Consistent with this hypothesis are data showing Rtg1-dependent NADH accumulation and limitations in formic acid biosynthesis (Figure 5 and Table 4).

While zwf1 mutants have no mitochondrial defects (Blank et al. 2005), Wu and Tzagoloff (1987) speculated that the petite-like phenotype of fum1 mutants is caused by decreased concentrations of intramitochondrial amino acids, which limits the production of respiratory chain components. However, loss of Fum1 alone does not account for retrograde signaling in PSY3642, as transcriptional changes in fum1 single mutants are limited; only ∼20 genes are affected, none of which encode typical retrograde responsive TCA cycle enzymes (McCammon et al. 2003). Furthermore, although Gelling et al. (2004) showed that C1 metabolic flux changes significantly affect the expression status of respiratory chain components, mitochondrial deficiency and retrograde signaling were not reported as a consequence. From these results we conclude that enzyme deletions predicted by our model cause systemic metabolic changes that modulate C1 flux and activate retrograde signaling in PSY3642. Specifically, alt2-associated loss of cytoplasmic alanine transaminase activity—either alone or in combination with fum1 or zwf1 mutations—may significantly diminish aminogenic capacity leading to full activation of the retrograde response. Alternatively, retrograde signaling may result from reduced intracellular concentrations of specific retrograde inhibitors such as glutamate, glutamine, or ammonia (Crespo et al. 2002; Tate and Cooper 2003; Butow and Avadhani 2004; Dilova et al. 2004).

Multisite modulation is an important mechanism of metabolic control, where changes in pathway flux result from the coordinated expression of multiple pathway enzymes in relative proportion to their distance from the main pathway branch point (Thomas and Fell 1996; Fell 1997). Accumulating evidence obtained in yeast (Niederberger et al. 1992), mammals (Brownie and Pedersen 1986; Waterman and Simpson 1989; Hillgartner et al. 1995; Vogt et al. 2002; Werle et al. 2005), and plants (Quick et al. 1991; Stitt et al. 1991; Anterola et al. 1999) suggests that multisite modulation may be a general design principle employed by cells to regulate metabolic flux in vivo (Wildermuth 2000). Indeed, using formal pathway analysis, we identified a module of pathway function corresponding to downstream reactions in C1 metabolism (Equation 1) and observed a pattern of differential expression in PSY3642 that strongly suggested multisite modulation of enzymes in this pathway (Figure 6B).

A predominant challenge in constraint-based analysis of metabolic networks involves discovering and incorporating relevant cellular regulatory processes (Price et al. 2003; Stelling and Gilles 2004). Because regulatory events are conditional and often characterized by their dynamic nature, they are difficult to predict under the assumptions of conventional FBA (Jamshidi and Palsson 2008). Without the benefit of complete knowledge of gene regulation it is useful to combine systems-level modeling with experimental data generated post hoc for the purposes of design and discovery in complex metabolic systems. By combining formal pathway analysis, FBA, and experimentation, we were able to identify and exploit specific modes of endogenous regulation to increase C1 metabolic flux and engineer a formic acid-producing strain of yeast.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Agapakis and Jake Wintermute for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant to C.J.K., by an NIH Cell and Developmental Biology training grant (GM07226) to P.M.B., and in part by a grant from the Harvard University Center for the Environment.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.105254/DC1.

References

- Alper, H., J. Moxley, E. Nevoigt, G. R. Fink and G. Stephanopoulos, 2006. Engineering yeast transcriptional machinery for improved ethanol tolerance and production. Science 314: 1565–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anterola, A. M., H. van Rensburg, P. S. van Heerden, L. B. Davin and N. G. Lewis, 1999. Multi-site modulation of flux during monolignol formation in loblolly pine (Pinus taeda). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 261: 652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, B. M., C. Bro, P. Kotter, M. A. H. Luttik, J. P. van Dijken et al., 2000. The mitochondrial alcohol dehydrogenase Adh3p is involved in a redox shuttle in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 182: 4730–4737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S. A., and B. O. Palsson, 2008. Context-specific metabolic networks are consistent with experiments. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4: e1000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J. K., G. A. Grant and L. J. Banaszak, 2004. Multiconformational states in phophoglycerate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 43: 3450–3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkmann, A., F. Zinoni, G. Sawers and A. Brök, 1987. Factors affecting transcriptional regulation of the formate-hydrogen-lyase pathway of Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 148: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank, L. M., L. Kuepfer and U. Sauer, 2005. Large-scale 13C-flux analysis reveals mechanistic principles of metabolic network robustness to null mutations in yeast. Genome Biol. 6: R49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bro, C., B. Regenberg, J. Forster and J. Nielsen, 2006. In silico aided metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for improved bioethanol production. Metab. Eng. 8: 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownie, A. C., and R. C. Pedersen, 1986. Control of aldosterone secretion by pituitary hormones. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 4: S72–S75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard, A. P., P. Pharka and C. D. Maranas, 2003. Optknock: a bilevel programming framework for identifying gene knockout strategies for microbial strain optimization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 84: 647–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butow, R. A., and N. G. Avadhani, 2004. Mitochondrial signaling: the retrograde response. Mol. Cell 14: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canelas, A. B., W. M. van Gulik and J. J. Heijnen, 2008. Determination of the cytosolic free NAD/NADH ratio in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under steady-state and highly dynamic conditions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 100: 734–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, K. E., and R. E. MacKenzie, 2006. Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism is adapted to the specific needs of yeast, plants and mammals. BioEssays 28: 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan, S. R., N. Gounalaki, P. Hatis and D. Tzamarias, 1999. The Tup1-Cyc8 protein complex can shift from a transcriptional co-repressor to a transcriptional co-activator. J. Biol. Chem. 1: 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordier, H., F. Mendes, I. Vasconcelos and J. M. Francois, 2007. A metabolic and genomic study of engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for high glycerol production. Metab. Eng. 9: 364–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, J. L., T. Powers, B. Fowler and M. N. Hall, 2002. The TOR-controlled transcription activators GLN3, RTG1, and RTG3, are regulated in response to intracellular levels of glutamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 6784–6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilova, I., S. Aronova, J. C.-Y. Chen and T. Powers, 2004. Tor signaling and nutrient-based signals converge on Mks1p phosphorylation to regulate expression of Rtg1p-Rtg3p-dependent target genes. J. Biol. Chem. 45: 46527–46535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pierro, D., B. Tavazzi, C. F. Perno, M. Bartolini, E. Balestra et al., 1995. An ion-pairing high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the direct simultaneous determination of nucleotides, deoxynucleotides, nicotinic coenzymes, oxypurines, nucleosides, and bases in perchloric acid cell extracts. Anal. Biochem. 231: 407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, N. C., M. J. Herrgård and B. O. Palsson, 2004. Reconstruction and validation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae iND750, a fully compartmentalized genome-scale metabolic model. Genome Res. 14: 1298–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J. S., and B. O. Palsson, 2000. The Eschericia coli MG1655 in silico metabolic genotype: its definition, characteristics, and capabilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 5528–5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, C. B., J. A. Waddle, W. Hale, 4th, V. Dave, J. Thornton et al., 2001. Genome-wide responses to mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell, D. A., 1997. Frontiers in Metabolism: Understanding the Control of Metabolism. Portland Press, London.

- Fell, D. A., and K. Snell, 1988. Control analysis of mammalian serine biosynthesis. Feedback inhibition on the final step. Biochem. J. 256: 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, J., I. Famili, B. Palsson and J. Nielsen, 2003. Large-scale evaluation of in silico gene knockouts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. OMICS 7: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, T. F., J. P. Rife and V. Schirch, 2001. The role of serine hydroxymethyltransferase isozymes in one-carbon metabolism in MCF-7 cells as determined by 13C NMR. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 393: 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertman, J. M., A. J. van Maris, J. P. van Dijken and J. T. Pronk, 2006. Physiological and genetic engineering of cytosolic redox metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for improved glycerol production. Metab. Eng. 8: 532–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelling, C. L., M. D. Piper, S. P. Hong, G. D. Kornfeld and I. W. Dawes, 2004. Identification of a novel one-carbon metabolism regulon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 7072–7081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, S. R., and A. D. Johnson, 2004. Promoter-dependent roles for the Srb10 cyclin-dependent kinase and the Hda1 deacetylase in Tup1-mediated repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 4191–4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldener, U., S. Heck, T. Fiedler, J. Beinhauer and J. H. Hegemann, 1996. A new efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 2519–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefetz, A., and M. S. Blum, 1978. Biosynthesis of formic acid by the poison glands of formicine ants. Science 201: 454–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, O., D. Ramon and M. Orejas, 2008. Engineering the Saccharomyces cerevisiae isoprenoid pathway for de novo production of aromatic monoterpenes in wine. Metab. Eng. 10: 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillgartner, F. B., L. M. Salati and A. G. Goodridge, 1995. Physiological and molecular mechanisms involved in nutritional regulation of fatty acid synthesis. Physiol. Rev. 75: 47–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjersted, J. L., M. A. Henson and R. Mahadevan, 2007. Genome-scale analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism and ethanol production in fed-batch culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 97: 1190–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. R., M. J. Marton, A. R. Jones, C. J. Roberts, R. Stoughton et al., 2006. Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell 102: 109–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, N., S. Saltoh, T. Ohnishi, K. Tokuhiro, E. Nagamori et al., 2006. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for efficient production of pure L: -(+)-lactic acid. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 131: 795–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi, N., and B. O. Palsson, 2008. Formulating genome-scale kinetic models in the post-genome era. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4: 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastanos, E. K., Y. Y. Woldman and D. R. Appling, 1997. Role of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic serine hydroxymethyltransferase isozymes in de novo purine synthesis in Sacharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 36: 14956–14964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizer, L., D. J. Pitera, B. F. Pfleger and J. D. Keasling, 2008. Application of functional genomics to pathway optimization for increased isoprenoid production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74: 3229–3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klamt, S., and J. Stelling, 2002. Combinatorial complexity of pathway analysis in metabolic networks. Mol. Biol. Rep. 29: 233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, T., 2003. Idempotent vector design for standard assembly of biobricks. In DSpace. MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, MIT Synthetic Biology Working Group. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/21168.

- Lange, H. C., M. Eman, G. van Zuijlen, D. Visser, J. C. van Dam et al., 2001. Improved rapid sampling for in vivo kinetics of intracellular metabolites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 75: 406–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., A. Goel, M. M. Ataii and M. M. Domach, 1997. Supply-side analysis of growth of Bacillus subtilis on glucose-citrate medium: feasible network alternatives and yield optimality. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63: 710–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., C. Phalakornkule, M. M. Domach and I. E. Grossmann, 2000. Recursive MILP model for finding all alternate optima in LP models for metabolic networks. Comp. Chem. Eng. 24: 711–716. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhartsberger, S., I. Korsa and A. Bock, 2002. The molecular biology of formate metabolism in enterobacteria. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4: 269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., and R. A. Butow, 2006. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40: 159–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludovico, P., F. Rodrigues, A. Almeida, M. T. Silva, A. Barrientos et al., 2002. Cytochrome c release and mitochondria involvement in programmed cell death induced by acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 2598–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malave, T. M., and S. Y. Dent, 2006. Transcriptional repression by Tup1-Ssn6. Biochem. Cell Biol. 84: 437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCammon, M. T., C. B. Epstein, B. Przybyla-Zawislak, L. McAlister-Henn and R. A. Butow, 2003. Global transcription analysis of Krebs tricarboxylic acid cycle mutants reveals an alternating pattern of gene expression and effects on hypoxic and oxidative genes. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 958–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, J. B., A. L. Bognar and R. E. Pearlman, 1996. In vivo analysis of folate coenzymes and their compartmentalization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 142: 371–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken, C. E., and H. D. May, 2007. Sustained generation of electricity by the spore-forming, Gram-positive, Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain DCB2. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73: 1180–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, P. T., N. Mendes, M. C. Teixeira, S. d'Orey, S. Tenreiro et al., 2008. YEASTRACT-DISCOVERER: new tools to improve the analysis of transcriptional regulatory associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: D132–D136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motter, A. E., N. Glubahce, E. Almass and A. L. Barabasi, 2008. Predicting synthetic rescues in metabolic networks. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4: 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, F., 1985. Multidimensional clustering algorithms. Physica-Verlag, Wuerzburg, Germany.

- Niederberger, P., R. Prasad, G. Miozzari and H. Kacser, 1992. A strategy for increasing an in vivo flux by genetic manipulations. The tryptophan system of yeast. Biochem. J. 287: 473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y.-K., B. O. Palsson, S. M. Park, C. H. Schilling and R. Mahadevan, 2007. Genome-scale reconstruction of metabolic network in Bacillus subtillis based on high-throughput phenotyping and gene essentiality data. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 28791–28799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overkamp, K. M., P. Kötter, R. van der Hoek, S. Schoondermark-Stolk, M. A. Luttik et al., 2002. Functional analysis of structural genes for NAD(+)-dependent formate dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 19: 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papin, J., N. Price, J. Edwards and B. Palsson, 2002. The genome-scale metabolic extreme pathway structure in Haemophilus influenzae shows significant network redundancy. J. Theor. Biol. 215: 67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters-Wendisch, P., M. Stolz, H. Etterich, N. Kennerknecht, H. Sahm et al., 2005. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-serine production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 7139–7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phalakornkule, C., S. Lee, T. Zhu, R. Koepsel, M. M. Ataai et al., 2001. A MILP-based flux alternative generation and NMR experimental design strategy for metabolic engineering. Metab. Eng. 3: 124–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, I., and P. A. Silver, 2006. A new biobrick assembly strategy designed for facile protein engineering. In DSpace. MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, MIT Synthetic Biology Working Group. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/32535.

- Piper, M. D., S. P. Hong, G. E. Ball and I. W. Dawes, 2000. Regulation of the balance of one-carbon metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 30987–30995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, N., J. L. Reed, J. A. Papin, S. J. Wiback and B. O. Palsson, 2003. Network-based analysis of metabolic regulation in the human red blood cell. J. Theor. Biol. 225: 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick, W. P., U. Schurr, R. Sheibe, E.-D. Schulze, S. R. Rodermel et al., 1991. Decreased ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase in tobacco transformed with 'antisense' rbcS. I. Impact on photosynthesis in ambient growth conditions. Planta 183: 542–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendis-Antonio, O., R. J. Reed, S. Encarnacion, J. Collado-Vides and B. O. Palsson, 2007. Metabolic reconstruction and modeling of nitrogen fixation in Rhizobium etli. PLoS Comp. Biol. 3: e192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel, B. A., J. L. Thornton and R. A. Butow, 1997. Rtg3p, a basic helix-loop-helix/leucine zipper protein that functions in mitochondrial-induced changes in gene expression, contains independent activation domains. J. Biol. Chem. 32: 19801–19807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, C. H., D. Letsher and B. Ø. Palsson, 2000. Theoryfor the systemic definition of metabolic pathways and their use in interpreting metabolic function from a pathway-oriented perspective. J. Theor. Biol. 203: 229–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, S., D. A. Fell and T. Dandekar, 2000. A general definition of metabolic pathways useful for systematic organization and analysis of complex metabolic networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 18: 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, S., S. Klamt, W. Weckwerth, F. Moldenhaurer and T. Pfeiffer, 2002. Use of network analysis of metabolic systems in bioengineering. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 24: 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, Y., E. M. Paradise, J. Kirby, D. K. Ro and J. D. Keasling, 2007. Engineering of the pyruvate dehydrogenase bypass in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-level production of isoprenoids. Metab. Eng. 9: 160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. L., and A. D. Johnson, 2000. Turning genes off by Ssn6-Tup1: a conserved system of transcriptional repression in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporty, J. L., M. M. Kabir, K. W. Turteltaub, T. Ognibene, S. J. Lin et al., 2008. Single sample extraction protocol for the quantification of NAD and NADH redox states in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Sep. Sci. 31: 3202–3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, I., Y. Peleg, S. Even-Ram and O. Pines, 1994. The single translation product of the FUM1 gene (fumarase) is processed in the mitochondria before being distributed between the cytosol and the mitochondria in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 4770–4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelling, J., and E. D. Gilles, 2004. Mathematical modeling of complex regulatory networks. IEEE Trans. Nanobioscience 3: 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt, M., W. P. Quick, U. Schurr, E.-D. Schulze, S. R. Rodermel et al., 1991. Decreased ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase in tobacco transformed with ‘antisense’ rbcS. II. Flux-control coefficients for photosynthesis in varying light, CO2, and air humidity. Planta 183: 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, M., W. B. Qiao, N. Khanam, O. Wilkins, S. D. Der et al., 2005. Transcriptional regulation of the one-carbon metabolism regulon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Bas1p. Mol. Microbiol. 57: 53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiegers, J. H., N. Dippenaar, I. S. Pretorius and F. F. Bauer, 2001. Carnitine-dependent metabolic activities in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: three carnitine acetyltransferases are essential in a carnitine-dependent strain. Yeast 18: 585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate, J. J., and T. G. Cooper, 2003. Tor1/2 regulation of retrograde gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae derives indirectly as a consequence of alterations in ammonia metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 38: 36924–36933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, M. C., P. Monteiro, P. Jain, S. Tenreiro, A. R. Fernandes et al., 2006. The YEASTRACT database: a tool for the analysis of transcription regulatory associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: D446–D451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S., and D. A. Fell, 1996. Design of metabolic control for large flux changes. J. Theor. Biol. 182: 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. R., J. K. Bell, J. Bratt, G. A. Grant and L. J. Banaszak, 2005. Vmax regulation through domain and subunit changes. The active form of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 44: 5763–5773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Maris, A. J., A. A. Winkler, D. Porro, J. P. van Dijken and J. T. Pronk, 2004. Homofermentative lactate production cannot sustain anaerobic growth of engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae: possible consequence of energy-dependent lactate export. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 2898–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma, A., and B. O. Palsson, 1994. Metabolic flux balancing: basic concepts, scientific and practical use. Biotechnology 12: 994–998. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, D., G. A. van Zuylen, J. C. van Dam, M. R. Eman, A. Proll et al., 2004. Analysis of in vivo kinetics of glycolysis in aerobic Saccharomyces cerevisiae by application of glucose and ethanol pulses. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 88: 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, A. M., H. Nef, J. Schaper, M. Poolman, D. A. Fell et al., 2002. Metabolic control analysis of anaerobic glycolysis in human hibernating myocardium replaces traditional concepts of flux control. FEBS Lett. 24: 245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waks, Z., and P. A. Silver, 2009. Engineering a synthetic dual organism for hydrogen production. Appl. Environ. Eng. 75: 1867–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, M. R., and E. R. Simpson, 1989. Regulation of steroid hydroxylase gene expression is multifactorial in nature. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 45: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werle, M., J. Kreuzer, J. Höfele, A. Elsässer, C. Ackermann et al., 2005. Metabolic control analysis of the Warburg-effect in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 12: 827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildermuth, M., 2000. Metabolic control analysis: biological applications and insights. Genome Biol. 1: 1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M., and A. Tzagoloff, 1987. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fumarases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are encoded by a single nuclear gene FUM1. J. Biol. Chem. 262: 12275–12282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, A., T. Nishimura, H. Kawaguchi, M. Inui and H. Yukawa, 2005. Enhanced hydrogen production from formic acid by formate hydrogen lyase-overexpressing Escherichia coli strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 6762–6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelle, R. M., E. de Hulster, W. A. van Winden, P. de Waard, C. Dijkema et al., 2008. Malic acid production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae: engineering of pyruvate carboxylation, oxaloacetate reduction, and malate export. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74: 2766–2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]