Abstract

We demonstrate that recent data from human males are consistent with constant interference levels among chromosomes under the two-pathway model, whereas inappropriately fitting shape parameters of Gamma distributions to immunofluorescent interfoci distances observed on finite chromosomes generates false interpretations of higher levels of interference on shorter chromosomes. We provide appropriate statistical methodology.

WORKING with mice, de Boer et al. (2006) fit the shape parameter of the Gamma distribution to inter-MLH1-foci distances on the synaptonemal complex as a new method for measuring crossover interference. The method exploited demonstrations that the Gamma distribution models intercrossover distances well when measured in terms of genetic length [on infinitely long chromosomes; Broman and Weber (2000)] and that the synaptonemal complex length may simply introduce a change in scale (Lynn et al. 2002). The methodology has since been employed to estimate interference again in mice (Barchi et al. 2008), as well as in dogs (Basheva et al. 2008), cats (Borodin et al. 2007), shrews (Borodin et al. 2008), minks (Borodin et al. 2009), tomatoes (Lhuissier et al. 2007), and humans (Lian et al. 2008).

Lian et al. (2008) used the estimates of the shape parameter in human males to conclude that interference increases as chromosomal length decreases. This seemingly contradicts earlier work of Kaback et al. (1999), who observed in budding yeast that the recombination rate per megabase increases but that interference decreases as chromosomal length decreases. In this note, we argue that the results of both Kaback et al. (1999) and Lian et al. (2008) are consistent with constant interference levels when analyzed under the two-pathway hypothesis for crossing over (Stahl et al. 2004; Getz et al. 2008).

According to this hypothesis, there are two recombinational pathways: crossovers in the pairing pathway promote pairing of the chromosomes and have no interference whereas crossovers in the disjunction pathway manifest interference. If, as in Housworth and Stahl (2003), we assume that each chromosome must have the same average number of double-strand breaks in the pairing pathway to achieve synapsis and the same proportion of these will have crossover resolutions, then the mathematical model for estimating genetic distance X in centimorgans from the physical distance L in number of megabase pairs would be X = aL + b. Here, a is the rate, per 100 meioses, of disjunction crossovers per megabase pair and b is the fixed average number of pairing pathway crossovers, per 100 meioses, per chromosome. Under this model, shorter chromosomes will have higher total recombination per megabase than long chromosomes and will seem to have lower levels of interference, explaining both of the results of Kaback et al. (1999). The regression analysis for human males based on the high-resolution Rutgers map (Matise et al. 2007) is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.—

Regression of male chromosomal genetic length, X (cM), on physical length, L (Mbp) from the high-resolution Rutgers combined linkage physical map of the human genome (Matise et al. 2007). The genetic length in the disjunction pathway for a human male chromosome can be estimated as X − 52 or 0.59L.

When analyzed with the two-pathway model, the results of Lian et al. (2008) are also explained by constant interference levels among chromosomes. Under this model, it is only the crossovers in the disjunction pathway that show up as MLH1 foci in the immunofluorescence images. Further, the interfoci distances given in the histograms of Lian et al. (2008) are conditional on the chromosomes receiving at least two crossovers, which, among other things, truncates the distance to be no more than the length of the chromosome whereas the Gamma distribution models intercrossover distances on infinitely long chromosomes. Indeed, the results of our simulation of 100 meioses from 10 men with constant interference given in Figure 2 match well with the corresponding histograms in Figure 2 of Lian et al. (2008). We conclude that the large shape estimates reported by Lian et al. (2008) for short chromosomes are simply due to the bias induced by inappropriately fitting a Gamma distribution to the data.

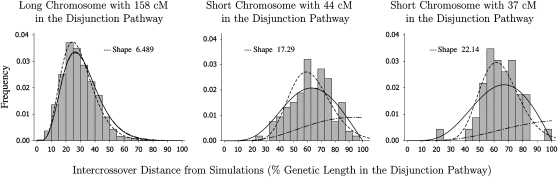

Figure 2.—

The fit of a Gamma distribution to simulated intercrossover distances from 100 meioses from 10 men who follow the counting model with m = 5. The interference parameter, m, is the number of randomly distributed precursors between crossover events. The use of m = 5 is consistent with previous estimates of interference in human males (Broman and Weber 2000; Housworth and Stahl 2003). The shape parameter of a Gamma distribution fitted to intercrossover distances occurring on infinitely long chromosomes would be ν = m + 1 (or 6 in this case). The dashed-dotted lines show this unconditional Gamma distribution for the intercrossover distances, appropriately scaled. The dashed lines are the inappropriately fitted Gamma distributions and the solid lines are the intercrossover distributions conditional on the chromosome receiving at least two crossovers. For the longest chromosome, the effect of conditioning is so negligible that the unconditional and conditional lines are nearly indistinguishable and are very similar to the inappropriately fitted Gamma distribution. For chromosome 19, the length in the disjunction pathway is ∼X − 52 = 44 cM and the resulting interfoci distances, when fitted inappropriately to a Gamma distribution, have an inflated shape parameter similar to the results of Lian et al. (2008). To explain the results of Lian et al. (2008) for chromosome 20, we have to assume that the total genetic length of chromosome 20 in the Rutgers map is overestimated and that the correct length to use for the simulation is closer to 0.59L, which is ∼37 cM. With that assumption, it is possible to generate data giving an estimate for the shape parameter of an inappropriately fitted Gamma distribution similar to the results of Lian et al. (2008).

We note further that the natural measure of interference involves genetic distances. In that framework, the shape and scale parameters of the Gamma distribution do not both freely vary: the rate (reciprocal of the scale) is twice the shape, ν. For data normalized to be a percentage of the entire length, the restriction is that the scale, μ, = 100/(2νx), where x is the genetic length (in morgans) of the chromosome in the disjunction pathway.

METHOD OF ANALYSIS FOR FOCI DATA

de Boer et al. (2006) recognized the finite chromosome issue and employed an ad hoc method to address it, which was not utilized by the subsequent authors. The proper method of analysis of foci data would take into account all information, including the distances from the ends to the nearest crossovers. Assume that the data are relative to the total length. Then a small set of results for four meioses involving a given chromosome is given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Tiny example dataset

| Meiosis | Lengths | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 47 | 23 | ||

| 2 | 100 | ||||

| 3 | 45 | 55 | |||

| 4 | 12 | 38 | 27 | 13 | 10 |

In this data set, the second meiosis had no crossovers at all. The third meiosis had only one crossover that occurred at not quite half the length of the chromosome. The first meiosis had two crossovers with a relative intercrossover distance of 47% of the length of the chromosome. The lengths to the ends of the chromosome were 30 and 23% of the total length. The fourth meiosis had four crossovers with intercrossover distances of 38, 27, and 13% of the total length and lengths to the ends that were 12 and 10% of the total.

The total likelihood of the data set is the product of the probabilities of all of these events, including the distances to the ends and the probability of receiving no crossover when none occurred. Following Broman and Weber (2000) without thinning the results from the four-strand bundle, the probability density of observing a given intercrossover distance, y, is Gamma distributed and is given by the formula

|

The probability density of the length to one of the ends, y, is the probability of the censored observation, which is

|

where F(y | ν, μ) is the cumulative distribution function of f (y | ν, μ).

The probability density of the length to the other end, y, is the density required for stationarity (so that it does not matter which end is considered the censored one) and is

|

where F(y | ν, μ) is again the cumulative distribution function of f(y | ν, μ).

The probability of having no crossovers on the entire length is the probability of not getting a first crossover, which is

|

where G(y | ν, μ) is the cumulative distribution function of g(y | ν, μ). Chromosomes with no crossovers would contribute this probability to the product.

If the scale is restricted to μ = 100/(2νx) with the genetic length x known, then the likelihood is a function of only one variable, ν, and can be optimized easily. Code in R that takes as input a data set such as the one in Table 1 and returns the best estimate for ν along with an estimate of the standard error in ν is provided as supporting information, File S1 and also at http://mypage.iu.edu/∼ehouswor/Software/InterMLH1fociCode.html.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.103853/DC1.

References

- Barchi, M., I. Roig, M. di Giacomo, D. G. de Rooij, S. Keeney et al., 2008. ATM promotes the obligate XY crossover and both crossover control and chromosome axis integrity on autosomes. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000076.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basheva, E. A., C. J. Bidau and P. M. Borodin, 2008. General pattern of meiotic recombination in male dogs estimated by MLH1 and RAD51 immunolocalization. Chromosome Res. 16: 709–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodin, P. M., T. V. Karamysheva and N. B. Rubtsov, 2007. Immunofluorescent analysis of meiotic recombination in the domestic cat. Cell Tissue Biol. 1: 503–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodin, P. M., T. V. Karamysheva, N. M. Belonogova, A. A. Torgasheva, N. B. Rubtsov et al., 2008. Recombination map of the common shrew, Sorex araneus (Eulipotyphla, Mammalia). Genetics 178: 621–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodin, P. M., E. A. Basheva and A. I. Zhelezova, 2009. Immunocytological analysis of meiotic recombination in the American mink (Mustela vison). Anim. Genet. 40: 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman, K. W., and J. L. Weber, 2000. Characterization of human crossover interference. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66: 1911–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, E., P. Stam, A. J. J. Dietrich, A. Pastink and C. Heyting, 2006. Two levels of interference in mouse meiotic recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 9607–9612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz, T. J., S. A. Banse, L. S. Young, A. V. Banse, J. Swanson et al., 2008. Reduced mismatch repair of heteroduplexes reveals “non”-interfering crossing over in wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 178: 1251–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housworth, E. A., and F. W. Stahl, 2003. Crossover interference in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73: 188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaback, D. B., D. Barber, J. Mahon, J. Lamb and J. You, 1999. Chromosome size-dependent control of meiotic reciprocal recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the role of crossover interference. Genetics 152: 1475–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhuissier, F. G. P., H. H. Offenberg, P. E. Wittich, N. O. E. Vischer and C. Heyting, 2007. The mismatch repair protein MLH1 marks a subset of strongly interfering crossovers in tomato. Plant Cell 19: 862–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian, J, Y. Yin, M. Oliver-Bonet, T. Liehr, E. Ko et al., 2008. Variation in crossover interference levels on individual chromosomes from human males. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17: 2583–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, A., K. E. Koehler, L. Judis, E. R. Chan, J. P. Cherry et al., 2002. Covariation of synaptonemal complex length and mammalian meiotic exchange rates. Science 296: 2222–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matise, T. C., F. Chen, W. Chen, F. M. de la Vega, M. Hansen et al., 2007. A second-generation combined linkage physical map of the human genome. Genome Res. 17: 1783–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, F. W., H. M. Foss, L. S. Young, R. H. Borts, M. F. F. Abdullah et al., 2004. Does crossover interference count in Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Genetics 168: 35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]