Abstract

Aberrant neurotransmissions via glutamate and dopamine receptors have been the focus of biomedical research on the molecular basis of psychiatric disorders, but the mode of their interaction is yet to be uncovered. In this study, we demonstrated the pharmacological reversal of methamphetamine-stimulated dopaminergic overflow by suppression of group I metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptor in living primates and rodents. In vivo positron emission tomography (PET) was conducted on cynomolgus monkeys and rats using a full agonistic tracer for dopamine D2/3 receptor, [11C]MNPA [(R)-2-11CH3O-N-n-propylnorapomorphine], and fluctuation of kinetic data resulting from anesthesia was avoided by scanning awake subjects. Excessive release of dopamine induced by methamphetamine and abolishment of this alteration by treatment with an antagonist of group I mGlu receptors, 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP), were measured in both species as decreased binding potential because of increased dopamine and its recovery to baseline levels, respectively. Counteraction of MPEP to the methamphetamine-induced dopamine spillover was also supported neurochemically by microdialysis of unanesthetized rat striatum. Moreover, patch-clamp electrophysiological assays using acute brain slices prepared from rats indicated that direct targets of MPEP mechanistically involved in the effects of methamphetamine are present locally within the striatum. Because MPEP alone did not markedly alter the baseline dopaminergic neurotransmission according to our PET and electrophysiological data, the present findings collectively extend the insights on dopamine–glutamate cross talk from extrastriatal localization of responsible mGlu receptors to intrastriatal synergy and support therapeutic interventions in case of disordered striatal dopaminergic status using group I mGlu receptor antagonists assessable by in vivo imaging techniques.

Keywords: dopamine, glutamate, neurotransmission, PET, metabotropic glutamate receptor, methamphetamine, schizophrenia

Introduction

Clarification of the molecular pathophysiology of psychosis based on disordered dopaminergic and glutamatergic neurotransmissions (Seeman, 1987; Carlsson, 1988; Takahashi et al., 2006) is a current research priority for a significant number of biomedical scientists, because dopamine stimulants amphetamine (Castner et al., 2005; Featherstone et al., 2007) and methamphetamine (Ujike and Sato, 2004) and the NMDA receptor antagonists ketamine (Krystal et al., 1994; Aalto et al., 2002) and phencyclidine (Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Jentsch and Roth, 1999) are known to evoke psychotic manifestations resembling those of schizophrenia. The vast majority of efficacious antipsychotics are also aimed at blockage of central dopamine D2 receptors (Conley and Kelly, 2002). Another avenue toward antipsychotic modulation of neurotransmissions has also been offered by a selective agonist for metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) 2/3 receptors (Moghaddam and Adams, 1998; Patil et al., 2007). This finding, in conjunction with the contribution of NMDA receptors to the pathophysiology of the dopaminergic system (Moghaddam et al., 1997; Javitt et al., 2004), has led dialogs between dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems (Carlsson and Carlsson, 1990; Laruelle et al., 2003; Javitt, 2007) to become a paramount focus of neurobiological approaches in studies of schizophrenia.

Besides the ligands for group II mGlu receptors, 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP), which binds selectively to mGlu5 receptor (Gasparini et al., 1999), has also been shown to alleviate amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion in rats (Spooren et al., 2000; Ossowska et al., 2001; Pietraszek et al., 2004), and microdialysis assays have indicated that this effect is attributable to its suppression of striatal dopamine overflow (Gołembiowska et al., 2003). However, systemic administration of MPEP causes only mild to modest reduction of the baseline dopamine release (Gołembiowska et al., 2003). Furthermore, hyperlocomotion of rats as a consequence of exposure to phencyclidine was augmented by the treatment with MPEP (Pietraszek et al., 2004), and thus the beneficial effect of MPEP may be rather confined to the normalization of glutamate receptors functionally and/or spatially coupled to the pharmacological targets of amphetamine.

In the present study, we provide the first demonstration that pharmacological reversal of methamphetamine-provoked dopamine excess by an mGlu5 receptor blockade is detectable in living rats and monkeys by positron emission tomography (PET). The ability to collect data on the synaptic dopamine concentration was strengthened by the use of an agonistic probe for dopamine D2-like (D2/3) receptor, (R)-2-11CH3O-N-n-propylnorapomorphine ([11C]MNPA) (Finnema et al., 2005a; Seneca et al., 2006). The binding of this compound is supposedly selective for D2/3 receptors in a high-affinity state and thus is sensitively displaceable by endogenous dopamine within the synaptic cleft (Creese et al., 1984; Seeman et al., 1985; Seneca et al., 2006). We also incorporated methodology for scanning animals in an unanesthetized condition, thereby circumventing the anesthesia-dependent alteration of radiotracer kinetics as reported for other ligands (Nader et al., 1999; Tsukada et al., 2001; Elfving et al., 2003; Momosaki et al., 2004) and especially the modulation of glutamatergic transmission by ketamine. Mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of MPEP on the normalization of methamphetamine-overactivated dopaminergic terminals have also been pursued by electrophysiological studies.

Materials and Methods

Radiochemistry.

[11C]MNPA was prepared as described previously (Finnema et al., 2005a). Briefly, the 2-OH group of (R)-2-OH-norapomorphine was selectively methylated with [11C]methyl iodide, which was synthesized with high specific radioactivity by single-pass reaction of [11C]methane with I2 (Zhang and Suzuki, 2005). The reaction mixture was applied to preparative HPLC, and the radioactive fraction corresponding to [11C]MNPA was collected. The radiochemical purity was >93% at the separation of tracer, and the specific radioactivity was 1800 ± 365 GBq/μmol (mean ± SE) at the end of synthesis.

Animals.

The animals used here were maintained and handled in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and our institutional guidelines. Protocols for the present animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Radiological Sciences.

Four male cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca irus) at 7 years of age weighing ∼6 kg were used. According to the surgical procedure described by Onoe et al. (1994), an acrylic cap was applied to the top of the monkey's skull to fixate its head on the monkey chair (Obayashi et al., 2001). A 1.5-tesla magnetic resonance (MR) imaging system (Philips Gyroscan S15/ACS II; Philips Electronic) was used for acquiring neuroanatomical information on the brain of each monkey, which consisted of axial T1-weighted MR images generated with a three-dimensional spin-echo sequence.

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Japan SLC) weighing 300–400 g were housed two or three per cage at a constant room temperature (25°C) under a 12 h light/dark cycle (light from 7:00 A.M. to 7:00 P.M.) for 2–4 weeks. The rats were also operated on by a technique similar to that for the monkeys to fixate their heads. An anatomical template of the rat brain consisting of axial T1-weighted MR images was obtained with a 3.0-tesla Philips Intera (Philips Electronic) by means of a three-dimensional spin-echo sequence.

PET measurements and image analysis.

PET scans for monkeys (n = 4) were performed using a high-resolution SHR-7700 PET camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) designed for laboratory animals, which provides 31 transaxial slices 3.6 mm (center-to-center) apart and a 33.1 cm (transaxial) × 11.16 cm (axial) field of view (FOV). The spatial resolution for the reconstructed images was 2.6 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) at the center of the FOV (Watanabe et al., 1997). The monkeys were conscious and immobilized by joining the acrylic cap on the head with the fixation device (Muromachi-Kikai) to ensure accuracy on repositioning (Okauchi et al., 2001). After a transmission scan for attenuation correction using a 68Ge-68Ga source, dynamic emission scans were conducted in a three-dimensional acquisition mode for 93 min (frames: 3 at 1 min, 4 at 3 min, and 13 at 6 min). Emission scan images were reconstructed with a 4 mm Colsher filter. [11C]MNPA was injected via the crural vein as a single bolus at the start of emission scanning. The injected doses of the radiotracer were 81.9–97.9 MBq (90.9 ± 4.4 MBq, mean ± SD).

PET scans for rats (n = 4) were performed with a small animal-dedicated microPET FOCUS220 system (CTI Concorde Microsystems), which yields a 25.8 cm (transaxial) × 7.6 cm (axial) FOV and a special resolution of 1.3 mm FWHM at the center of FOV (Tai et al., 2005). A 20 min transmission scan for attenuation correction was performed using a spiraling 68Ge-68Ga point source. Subsequently, list-mode scans were performed for 90 min. All list-mode data were sorted and Fourier rebinned into two-dimensional sinograms (frames: six at 20 s, five at 1 min, four at 2 min, three at 5 min, and six at 10 min). Images were thereafter reconstructed using two-dimensional filtered back-projection with a 0.5 mm Hanning filter. [11C]MNPA was injected via the tail vein as a single bolus at the start of emission scanning. The injected dose of the radiotracer was 34.4–65.5 MBq (41.9 ± 7.7 MBq, mean ± SD).

Subsequently to PET scans, anatomical regions of interest (ROIs) were manually defined on the left and right striata and cerebellar cortices in the PET images coregistered with MR images using PMOD software (PMOD Technologies). Regional radioactivity was calculated as percentage standardized uptake value [%SUV = (% injected dose/cm3 brain) × body weight (g)]. The radioactivity in the cerebellum was used for estimating the concentrations of free and nonspecifically bound radioligands in the brain, and the concentration of radioligands specifically bound to dopamine D2/3 receptors in the striatum was defined as the difference in total radioactivity between the striatum and cerebellum. We also examined the radioligand binding by calculating the binding potential (BPND; ratio at equilibrium of specifically bound radioligand to that of nondisplaceable radioligand in tissue) based on a multilinear reference tissue model (MRTM) (Ichise et al., 2003) using the cerebellar time-radioactivity curve as a reference.

A total of five PET scans, at intervals of ≥2 weeks, were performed for each animal. Control data were acquired in duplicate to examine the test–retest variability of [11C]MNPA-PET measurements. Assessments for pretreatment with MPEP (Tocris Cookson) alone were then conducted by intravenously administering 1 mg/kg MPEP 10 min before the radiotracer injection. MPEP at this dose is known to occupy ∼50% of central mGlu5 receptors (Patel et al., 2005). Methamphetamine (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma) challenges were also performed by intravenous administration of 0.5 mg/kg methamphetamine 5 min before the radiotracer injection. Finally, combined MPEP and methamphetamine pretreatments were done with both agents, each being administered as in the single-drug challenges.

As a supplementary study for examining reliability of PET measurements in awake animals, we also conducted [11C]MNPA-PET scans for a monkey and three rats with and without ketamine–xylazine anesthesia (details of experimental procedures are given in the supplemental material, available at www.jneurosci.org). Comparison of regional time-radioactivity curves for the same individuals in these conditions demonstrated that not only the uptake of the tracer into the brain but also its retention in the striatum showed substantial increase by the use of ketamine and xylazine (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In the anesthetized condition, peak radioactivities in the striatum and cerebellum were ∼450 and 250% SUV, respectively, and striatal BPND was 1.72 from monkey data. These data were consistent with the mean values of the previous experiment (Seneca et al., 2006), supporting the effects of anesthetics on radiotracer delivery and binding. In line with the monkey, striatal BPND values estimated by rat data under ketamine and xylazine anesthesia were increased by 42% compared with control values. Peak radioactivity in the striatum was also increased by 26% relative to that of the awake condition. Thus, depth of anesthesia is likely to induce fluctuations of the radioligand kinetics in both species, justifying the use of conscious animals for the purpose of precise PET quantifications with [11C]MNPA.

Microdialysis.

Microdialysis was conducted for conscious rats (n = 4) administered with either methamphetamine alone or MPEP and methamphetamine, as in the PET measurements. Under anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.), a guide cannula was implanted (stereotactic coordinates: anteroposterior, ±0.0 mm; mediolateral, 3.0 mm from bregma) according to the stereotactic atlas of the rat brain (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). The microdialysis probes with a membrane portion of 250 μm in diameter and 2 mm in length (Eicom A-I-8-02; Eicom) were inserted in the striatal region (4 mm below the dura mater) via the guide cannula. The probe was perfused with Ringer's solution, pH 6.4, at a flow rate of 2 μl/min, and 20 μl samples were collected every 10 min. Dopamine contents were measured by HPLC with electrochemical detection (HTEC-500; Eicom). The average of the data obtained over 30 min just before injection of drugs was used as the baseline value. The level of dopamine in extracellular fluid was expressed as percentage of baseline.

Electrophysiological study.

Sagittal corticostriatal slices (300 μm thick) were prepared from Sprague Dawley rats at postnatal days 14–24 with a microslicer (Dosaka). Slices were superfused continuously in a solution containing (in mm) 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.0 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26.0 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, and 0.1 picrotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich) and equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.3–7.4. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained from medium spiny (MS) neurons of the striatum under visual guidance (differential interference contrast /infrared optics) with an EPC-10 amplifier and Pulse software (HEKA Elektronik) using an Olympus BX50WI and a charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu Photonics). The patch electrodes (3–5 MΩ resistance) in both current- and voltage-clamp experiments contained 120 K-gluconate, 5 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 MgATP, and 0.1 NaGTP (adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH). For current-clamp recording, firing patterns were checked by positive and negative current injection.

For voltage-clamp recordings, synaptic responses were evoked by field stimulation of corticostriatal fibers at 0.05 Hz by a stimulating electrode consisting of a silver-painted patch pipette (Shin et al., 2006) to obtain half-maximum amplitude of the EPSC. Drugs were stored as frozen stock solution and diluted 1000-fold into artificial CSF immediately before use. To determine the effect of drug on EPSCs, the averaged EPSC amplitudes of 12 traces during the peak response to the drug were compared with those obtained immediately before drug application. The average EPSC was plotted as six consecutive traces. Signals were filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz with Pulse/PulseFit (Heka Elektronik). If series resistance changed by >20%, the experiments were discarded. Contributions of dopaminergic and glutamatergic innervations to EPSCs were assessed by using 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), SCH23390 hydrochloride, and (S)-(−)-sulpiride purchased from Tocris Cookson (supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The MS neurons showed a slow voltage-ramp and nonadapting firing pattern with depolarizing current, lacking sag with hyperpolarization (supplemental Fig. 2B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) (Kawaguchi et al., 1989). Synaptic currents were then evoked by electrical stimulation on the subcortical white matter in acute slices at the holding potential of −70 mV in the presence of picrotoxin (100 μm) to block GABAergic components at a rate of 0.05 Hz (supplemental Fig. 2A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). These currents were completely and reversibly inhibited by CNQX (20 μm), a selective AMPA receptor antagonist, confirming that the currents were AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs (supplemental Fig. 2C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Statistical analysis.

Unless specified otherwise, significant differences were assessed with repeated-measures ANOVA, with the experimental condition as a repeated factor. A two-tailed probability of 0.05 was selected as the significance level.

Results

Stability of [11C]MNPA-PET measurement for awake animals

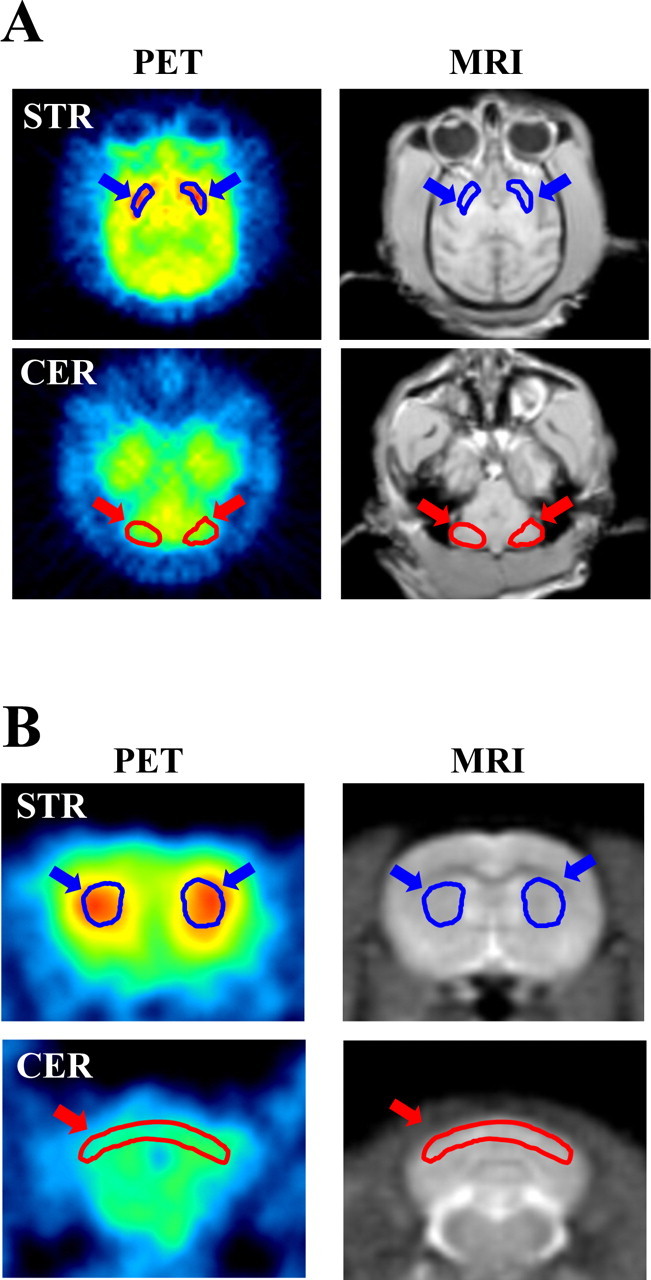

Representative PET images of monkey and rat brains were obtained by averaging dynamic data at 0–90 min after administration of [11C]MNPA and coregistered with anatomical MR images (Fig. 1). Time-radioactivity curves for ROIs defined on the striatum and cerebellum (Fig. 1) and regional time-radioactivity curves were generated (Fig. 2). In line with previous PET imaging of anesthetized monkeys (Seneca et al., 2006), high-level uptake of [11C]MNPA into the brain was observed as an initial rise of radioactivity over 1–2 min after tracer injection, and retention of the radiotracer thereafter was highest in the striatum and minimal in the cerebellum. Specific binding of the radioligand in the striatum, estimated as the difference in radioactivity between two regions, peaked between 30 and 40 min after administration. Striatal BPND values estimated using MRTM with cerebellar data as reference were 1.01 ± 0.048 and 1.00 ± 0.056 at the first and second baseline scans in monkeys (Table 1), respectively, indicating small interindividual and intraindividual variability.

Figure 1.

Distribution of [11C]MNPA in cynomolgus monkey (A) and rat (B) as viewed by PET. Transaxial (A) or coronal (B) MR images (MRI) at different levels were used for defining ROIs on the striatum (STR) and cerebellum (CER), as indicated by blue and red arrows, respectively. The ROIs were then translated to the coregistered PET images to generate regional time-radioactivity curves. The PET images displayed here reflect the radioactivity summed from 0 to 90 min after tracer injection.

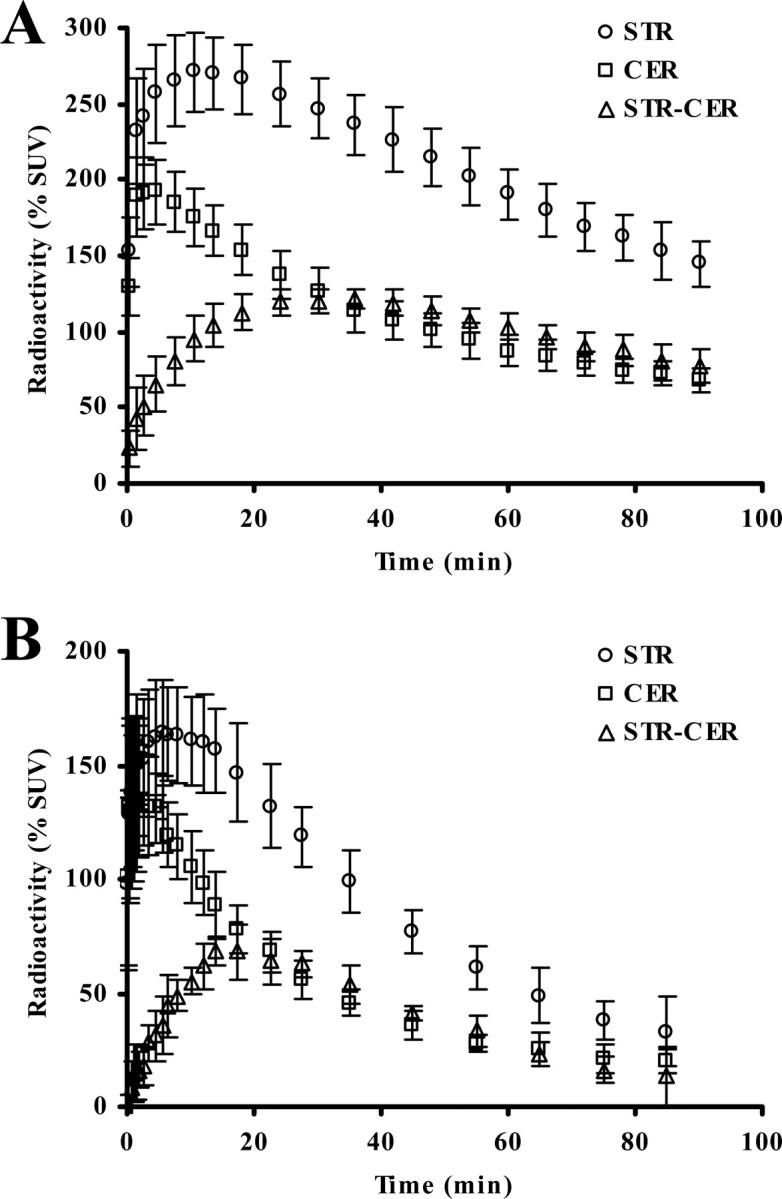

Figure 2.

Average (±SD) time-radioactivity data for the cerebellar (CER; circles) and striatal (STR; squares) regions, along with differences between the two regions (STR-CER; triangles) obtained from eight baseline [11C]MNPA-PET scans (2 scans per animal) for four monkeys (A) and four rats (B) in an awake condition. All data are expressed as percentage SUV (% SUV).

Table 1.

BPND for [11C]MNPA estimated from control data in monkeys

| Monkey ID |

BPND |

Variability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Retest | ||

| M1 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 3.0 |

| M2 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 3.0 |

| M3 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.7 |

| M4 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 8.1 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.01 ± 0.048 | 1.00 ± 0.056 | 3.7 ± 3.1 |

Meanwhile, striatal and cerebellar time-radioactivity curves in conscious rats illustrated considerably rapid kinetics of [11C]MNPA relative to monkeys (Fig. 2B). Clearance half-time provided by monoexponential fits of radioactivity loss from the rat cerebellum was 17 min, much smaller than the corresponding value in monkeys (40 min). Specific binding of the ligand in the rat striatum peaked at around 20 min after injection, thereafter promptly declining compared with that in the monkey striatum. Striatal BPND values estimated using MRTM were 0.83 ± 0.039 and 0.83 ± 0.017 at the first and second baseline scans in rats (Table 2), respectively, indicating stability of the present assay using unanesthetized animals.

Table 2.

BPND for [11C]MNPA estimated from control data in rats

| Rat ID |

BPND |

Variability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Retest | ||

| R1 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.5 |

| R2 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 1.0 |

| R3 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 4.7 |

| R4 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 1.7 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.83 ± 0.039 | 0.83 ± 0.017 | 2.0 ± 1.9 |

However, the mean BPND value in awake monkeys obtained here was smaller than that in anesthetized monkeys (Seneca et al., 2006) by ∼30%, suggesting that the use of ketamine and xylazine may influence the tracer kinetics. This notion was also supported by our auxiliary PET measurements for comparison of awake and anesthetized conditions in the same individuals, as described in Materials and Methods and demonstrated in supplemental Figure 1 (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Counteraction of MPEP to methamphetamine-induced decrease in [11C]MNPA binding to striatal D2/3 receptor

The effects of MPEP and methamphetamine, alone and in combination, on the association of [11C]MNPA with striatal dopamine receptor were analyzed in conscious animals (Figs. 3, 4; Tables 3, 4). We observed substantial reductions in radioligand binding to the striata of rats and monkeys pretreated with methamphetamine (0.5 mg/kg, i.v.). The decrement of the BPND value in awake monkeys (16.7%) was slightly smaller than that in the previous PET assay of anesthetized subjects with amphetamine challenge (∼25%) (Seneca et al., 2006), whereas the variance of methamphetamine-induced changes among individuals was small (Table 3). Methamphetamine profoundly influenced the kinetics of [11C]MNPA in rats relative to monkeys, as the BPND estimate dropped from baseline by 31.8% (Table 4). A single bolus injection of MPEP (1.0 mg/kg, i.v.) did not significantly alter the BPND value for [11C]MNPA in both rats and monkeys compared with untreated controls. In contrast, MPEP treatment reversed the attenuation of radiotracer binding resulting from methamphetamine exposure to a level comparable to controls (Tables 3, 4). This effect, again, was robustly found in all animals with small intersubject variance.

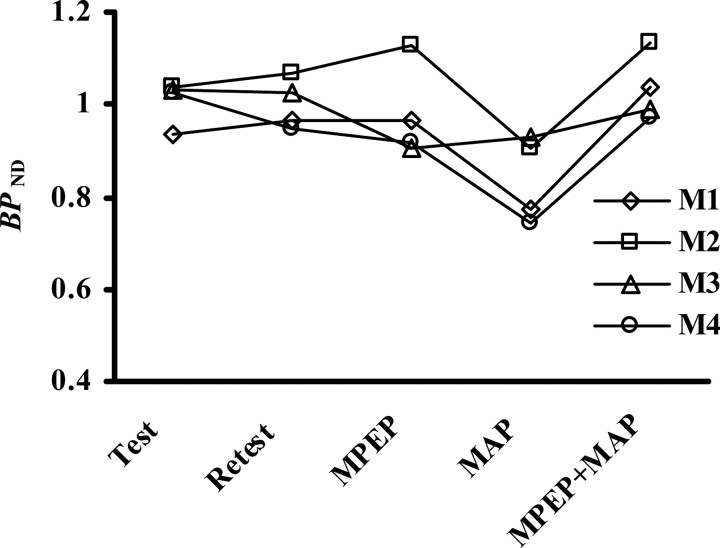

Figure 3.

BPND values in four monkeys at baseline PET scans (Test and Retest) and scans after treatments with MPEP alone, methamphetamine (MAP) alone, and the combination of MPEP and MAP (MPEP+MAP). M1–M4 correspond to the identifications of the monkeys shown in Table 1.

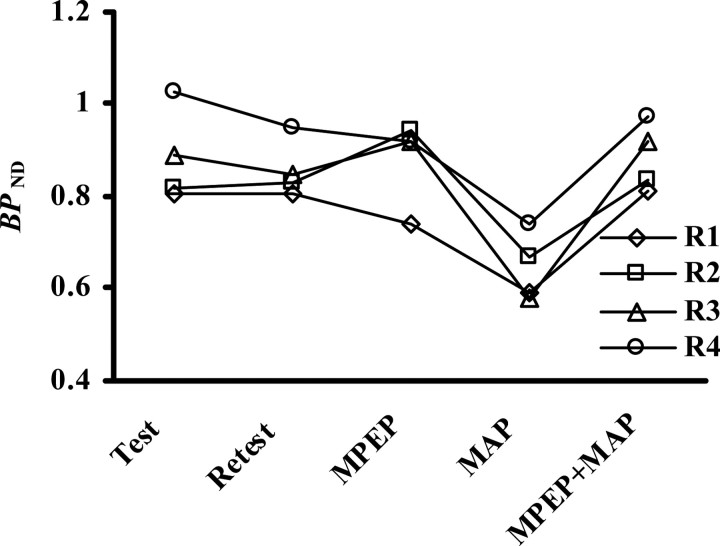

Figure 4.

BPND values in four rats at baseline PET scans (Test and Retest) and scans after treatments with MPEP alone, methamphetamine (MAP) alone, and the combination of MPEP and MAP (MPEP+MAP). R1–R4 correspond to the identifications of the rats shown in Table 2.

Table 3.

Quantified changes in striatal BPND values after administration of methamphetamine (MAP) and/or MPEP in monkeys

| Conditions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MPEP | MAP | MPEP plus MAP | |

| BPND mean (±SD) | 1.00 (±0.049) | 0.98 (±0.103) | 0.84* (±0.093) | 1.03 (±0.072) |

| ΔBPND (%) mean (±SD) | −2.5 (±8.6) | −16.7 (±6.5) | 2.9 (±6.5) | |

ΔBPND is calculated as the difference from the mean BPND value at baseline.

*p < 0.05 versus control.

Table 4.

Quantified changes in striatal BPND values after administration of methamphetamine (MAP) and/or MPEP in rats

| Conditions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MPEP | MAP | MPEP plus MAP | |

| BPND mean (±SD) | 0.83 (±0.028) | 0.86 (±0.090) | 0.57* (±0.105) | 0.86 (±0.050) |

| ΔBPND (%) mean (±SD) | 4.1 (±9.2) | −31.8 (±12.8) | 4.1 (±3.8) | |

ΔBPND is calculated as the difference from the mean BPND value at baseline.

*p < 0.05 versus control.

Statistical examination of the kinetic parameters also demonstrated insignificant changes of the striatal BPND values by MPEP alone (monkeys, p = 0.61; rats, p = 0.43; ANOVA) and significant reduction of BPND by methamphetamine (monkeys, p = 0.01; rats, p = 0.02; ANOVA). Statistical analysis also indicated that the perturbed binding of [11C]MNPA consequent to the methamphetamine challenge was normalized by MPEP to a degree showing no significant difference from the methamphetamine-free condition (monkeys, p = 0.45; rats, p = 0.12; ANOVA).

Neurochemical evidence for modulation of extracellular dopamine by methamphetamine and MPEP

Microdialysis was performed in rats under conditions identical to those of the PET studies (Fig. 5). The concentration of extracellular dopamine in the striatum was 0.97 ± 0.21 fmol/μl at baseline and was increased by ∼15-fold at 10 min after methamphetamine treatment. Meanwhile, MPEP pretreatment at 5 min before methamphetamine injection attenuated the effect of methamphetamine on the dopamine content by >50%. This observation supports the PET findings that the relatively rapid alteration of striatal dopaminergic neurotransmission by one-shot administration of methamphetamine was constantly suppressed by systemic priming with MPEP.

Figure 5.

Application of microdialysis to measurement of extracellular dopamine (DA) concentration in the striatum of rats. Assays were performed along the course of methamphetamine (MAP) treatment and combined MPEP and MAP administration (MPEP+MAP). Error bars represent SD.

Interference of MPEP with electrophysiological action of methamphetamine

Because the inhibitory effects of MPEP on methamphetamine-stimulated striatal dopamine release were consistently detectable by in vivo PET scans despite the absence of overt changes in basal dopaminergic transmission by this mGlu5 receptor antagonist alone, we assumed that the molecular targets of MPEP are tightly linked to the mechanism by which methamphetamine overdrives dopamine neurons and might be located in close connection to striatal dopaminergic terminals as well as nigral cell bodies. To examine this concept, we used electrophysiological methods on acute slices prepared from rat brains.

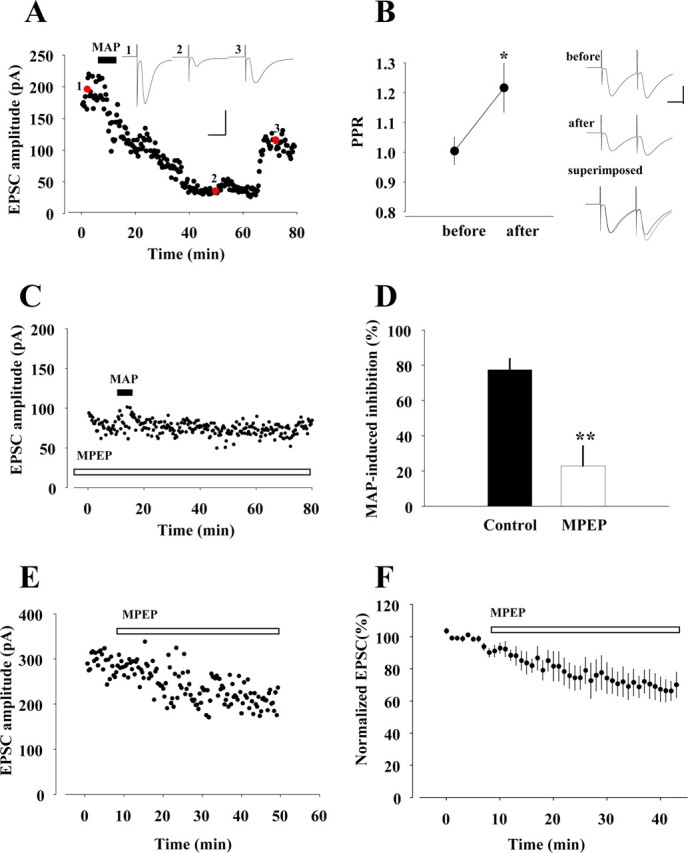

The amplitudes of the EPSCs in striatal MS neurons were reversibly inhibited by a bath application of methamphetamine (100 μm) for 5 min (Fig. 6A). To explore the mechanism for this inhibition, we investigated the effect of methamphetamine application on paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), which is commonly supposed to be a mostly presynaptic process (Zucker, 1989). The paired-pulse ratio (PPR; second response amplitude/first response amplitude), an index of PPF, was increased from 1.00 ± 0.05 to 1.22 ± 0.08 (p = 0.026, paired Student's t test; n = 5) as a result of methamphetamine application (Fig. 6B). This increase in PPR supports a decreased probability of glutamate release at corticostriatal synapses.

Figure 6.

Effects of MPEP on inhibition of EPSCs induced by methamphetamine (MAP). A, Effect of MAP (100 μm; filled bar) on EPSCs. Traces 1–3, taken at time points indicated by red circles, are representative EPSCs before, during, and after the application of MAP, respectively. Calibration: 100 pA, 20 ms. B, Left, Averages of PPRs before and during methamphetamine application (n = 4). *p < 0.05, paired Student's t test. Right, EPSCs elicited by two successive stimuli at an interval 50 ms before and during MAP application. Each trace is the average of 12 consecutive traces. In the superimposed trace, initial EPSCs during methamphetamine application were normalized to those recorded under control conditions. Calibration: 100 pA, 20 ms. C, Effect of pretreatment of MPEP (100 μm; open bar) on MAP-induced attenuation of EPSCs. D, Summarized comparative histograms showing effects of MAP alone (n = 5) and MPEP combined with MAP (n = 4). **p < 0.01, unpaired Student's t test. E, Amplitude of EPSCs after bath application of MPEP alone. F, Normalized EPSC amplitudes plotted before and during application of MPEP.

We then studied pharmacological characteristics of the methamphetamine-induced inhibition. Dopamine receptor antagonists were perfused continuously throughout the experiments from at least 5 min before methamphetamine application. In the presence of the D2/3 receptor antagonist sulpiride (10 μm), methamphetamine failed to inhibit the EPSCs (17.07 ± 2.98%; n = 3; p = 0.0004, unpaired Student's t test) (supplemental Fig. 2D, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In contrast, D1/5 receptor antagonist SCH23390 (10 μm) partially blocked the methamphetamine-induced inhibition of EPSCs (28.60 ± 2.96%; n = 6; p = 0.00003, unpaired Student's t test) (supplemental Fig. 2E, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In addition, these methamphetamine-induced inhibitions were blocked under pretreatment of the slices with a mixture of SCH23390 and sulpiride (supplemental Fig. 2F, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The inhibition of EPSCs (calculated as a percentage of baseline amplitude) by methamphetamine (n = 5) was significantly abolished in the presence of dopamine receptor antagonists (n = 3 in each condition), as summarized in supplemental Figure 2G (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). This result demonstrates that the suppression of EPSCs by methamphetamine can be primarily attributed to the increase in dopamine release in the synaptic cleft.

Subsequently, we analyzed changes in EPSCs provoked by methamphetamine after the application of MPEP to the slices. Notably, the pretreatment with MPEP completely blocked the inhibitory action of methamphetamine on the EPSC amplitude (Fig. 6C). The magnitude of methamphetamine-induced reduction in EPSC (Fig. 6D) was significantly depressed (p = 0.003, unpaired Student's t test) by the pretreatment with MPEP (67.24 ± 7.56% at 40 min; n = 4). Unlike the methamphetamine challenge, the use of MPEP alone resulted in mild and insignificant diminishment of EPSCs (Fig. 6E,F). These electrophysiological profiles indicate that mGlu5 receptors, on which MPEP acts, do not crucially participate in the regulation of basal dopaminergic activity but are pivotally involved in the regulation of dopamine neurons, possibly via linkage to methamphetamine-sensitive synaptic components within the striatal region.

Discussion

The present work provides neuroimaging evidence for functional cross talk between dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmissions in the regulation of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons after psychostimulant intake. Experimental elaborations of the methodological significance for successful detection of this neurochemical intercommunication include use of rodents and nonhuman primates in an unanesthetized condition for in vivo measurements and adoption of an agonistic radioligand for dopamine D2/3 receptor as a PET imaging agent. As demonstrated here, this setup provides a sensitive and robust estimation of changes in synaptic D2/3 receptors occupied by endogenous dopamine during the pathological perturbation of striatal neurotransmissions and its alleviation by modulation of a group I mGlu receptor. A similarly assembled assaying package would thereby be of great utility in assessing the efficacy of potential antianxiety and antipsychotic drugs acting on other groups of mGlu receptors, as exemplified by those in ongoing clinical trials (Patil et al., 2007; Dunayevich et al., 2008), in terms of their outcomes in mending a disordered dopaminergic system in a seamless translation of research insights from animal models to humans.

Integrating the present and previous (Seneca et al., 2006) [11C]MNPA-PET data, we conceive that anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine markedly alters the delivery and/or specific binding of this ligand, by which fluctuation of time-radioactivity data arises as a function of anesthetic depth. Indeed, the average difference in striatal BPND values between the first and second baseline scans of unanesthetized monkey brains in our study was 3.6%, markedly smaller than that reported for anesthetized animals (27%) (Seneca et al., 2006). Related investigations have indicated uncertainty regarding the influence of ketamine and other NMDA receptor antagonists on the interaction between D2/3 receptors and their ligands (Breier et al., 1998; Smith et al., 1998; Tsukada et al., 2000; Vollenweider et al., 2000; Aalto et al., 2002; Kegeles et al., 2002) and extracellular dopamine levels (Kashihara et al., 1990; Moghaddam et al., 1990; Onoe et al., 1994; Verma and Moghaddam, 1996), presumably because of the diversity of the experimental designs. Our auxiliary microdialysis experiment in rats (supplemental Fig. 3A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) treated with ketamine at a dose equivalent to that in the present supplementary PET scans (supplemental Fig. 2B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) demonstrated an elevated level of extracellular dopamine by ∼50%. It is a matter of caution that this increase in dopamine release after ketamine administration does not plausibly explain enhanced uptake and retention of [11C]MNPA, implying participation of a previously unclarified mechanism that is distinct from regulation of synaptic dopamine levels, in the ketamine-induced modification of radiotracer kinetics. It is also noteworthy that ketamine increases cerebral blood flow (Hassoun et al., 2003; Langsjo et al., 2005), whereby the transfer of radioligands from plasma to brain tissue may be enhanced. Although modification of dopaminergic transmission by xylazine has not been examined intensively, another α2-adrenoceptor agonist, dexmedetomidine, was documented to suppress dopamine release in mice (Ihalainen and Tanila, 2004). Notwithstanding the fact that the pursuit of the pharmacological effects of these drugs would engender a separate scope of research on the regulation of dopamine neurons via NMDA and adrenergic receptors, our experimental data in conjunction with previous notions on the complexity of anesthetic mechanisms justify the use of animals in an awake condition for circumvention of interactions among multiple neuroactive agents. This is of particular significance for the assessment of interference between dopamine and glutamate neurotransmissions, in consideration of the direct modulation of the glutamatergic system by ketamine.

The choice of radiotracers may also crucially determine the detectability of modulations of dopaminergic neurotransmission in living brains. According to the previous attempt to calculate the composition of striatal D2/3 receptors in different modes (Seneca et al., 2006), ∼60% of these receptors are in a high-affinity state, assuming that 10% are high-affinity species basally occupied by endogenous dopamine. This indication is based on the observation that agonistic D2/3 receptor ligands, incapable of accessing low-affinity receptors, were 1.7-fold more efficacious in capturing alterations of synaptic dopamine levels than antagonistic compounds. This estimation is in general agreement with other ex vivo and in vivo approaches comparing agonistic and antagonistic radioligand bindings (Cumming et al., 2002; Narendran et al., 2004; Finnema et al., 2005b). Likewise, the decrements of BPND for [11C]MNPA by 17% (monkeys) and 32% (rats) observed in our PET scans after administration of 0.5 mg/kg methamphetamine correspond to the occupancies of 38% and 71% of basally “vacant” synaptic D2/3 receptors in a high-affinity state by endogenous dopamine, respectively, although it remains to be clarified whether the same modal composition of D2/3 receptors is applicable to the rat striatum. Such significant provocation of dopamine release might also be recognizable with [11C]raclopride, for which the reduction of BPND in the same challenge would not exceed 10% in monkeys if excellent reproducibility (i.e., test–retest variability <5%), as demonstrated in the present study, could be achieved by the use of unanesthetized animals. However, avoiding anesthesia might still not allow the conclusive revelation of the interaction between methamphetamine and MPEP with sufficient statistical power for [11C]raclopride-PET, because a 10% difference at maximum needs to be examined among three or four conditions, each supposedly having 5% variability. In contrast, the present data provide explicit evidence for the reversal of methamphetamine-stimulated dopamine release by preadministered MPEP, because the differential of BPND for [11C]MNPA between methamphetamine challenges with or without MPEP greatly surpassed the variability of measurements. In fact, injection of MPEP at a dosage of 1 mg/kg was found to normalize the BPND value in monkeys by decreasing it by 20%, much larger than the probable variability of 5%. This also indicates that MPEP was potent enough to attenuate the occupancy of available high-affinity synaptic D2/3 receptors by overflowing dopamine from the above-mentioned value (38%) in the methamphetamine test to <11% (corresponding to baseline BPND plus 5%).

The notable capability of MPEP in depressing methamphetamine-overdriven dopaminergic transmission to an extent measurable by in vivo PET may additionally be attributed to a tight interconnection between molecular pathways initiated by the application of methamphetamine and manipulation of group I mGlu receptors, as illustrated by our electrophysiological data. Because the patch-clamp technique introduced here specifically collected information on striatal synapses between cortical and MS neurons involving additional connections from dopamine neurons, the consistency between neuroimaging and electrophysiological results also validates the theoretical view that PET measurements during the methamphetamine challenge primarily reflect the status of synaptically released dopamine. AMPA receptor-mediated glutamatergic transmission to MS neurons is known to be modulated by synaptic dopamine through presynaptic dopamine receptors, leading to the inhibition of EPSCs in these cells (Harvey and Lacey, 1996; Umemiya and Raymond, 1997; Kline et al., 2002), and methamphetamine-stimulated dopamine release in the synaptic cleft is conceived to reinforce this regulatory mechanism, similar to previous observations under amphetamine or cocaine treatment (Scarponi et al., 1999; Centonze et al., 2002). According to in vitro assessments (Sandoval et al., 2001; Fleckenstein et al., 2007), the intensification of synaptic dopamine by exposure to amphetamines is mediated by promotion of protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent phosphorylation of dopamine transporter (DAT), leading to its functional suppression. Interestingly, stimulation of a group I mGlu receptor by a selective agonist has also been shown to abolish functional diminishment of DAT consequent to pharmacological inhibition of PKC and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (Page et al., 2001). Together with our data, these observations support the contention that an intrastriatal group I mGlu receptor could participate in the regulation of the dopaminergic system via a molecular mechanism highly overlapped with that involved in amphetamine- and methamphetamine-induced dopamine overflows. It is also likely that MPEP counteracts amphetamines at synaptic terminals in the striatum by reversing enhanced phosphorylation of DAT. This represents a plausible explanation for the unequivocal efficacy of MPEP in normalizing the disrupted control of dopaminergic neurotransmission without pronounced influences in the normal condition and highlights the pathophysiological and therapeutic significances of striatal group I mGlu receptors in neurological and psychiatric disorders, besides the previously proposed scheme on the contribution of these receptors in cell bodies of nigral dopamine neurons to the modulation of striatal dopamine levels (Gołembiowska et al., 2003). In light of this insight, group I mGlu receptors in the striatum could be tightly linked to dysregulation of dopamine neurons involving DAT but may not be critically implicated in disorders of the dopaminergic system mediated by other mechanisms. Indeed, our preliminary microdialysis assay illustrated no overt influences of MPEP pretreatment on dopaminergic overflow stimulated by inhibition of NMDA receptors with phencyclidine (supplemental Fig. 3B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), which is in line with discrepant actions of MPEP on amphetamine- and phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotions (Pietraszek et al., 2004). The extent of pathogenic implication of group I mGlu receptor in neuropsychiatric disorders would be proven by PET imaging of living patients with emerging radioligands (Ametamey et al., 2006), which would rationalize medicinal intervention in ill-balanced glutamatergic–dopaminergic tones.

The present electrophysiological assessments also provide a notion on distinct contributions of the D1/5 and D2/3 systems to the striatal glutamatergic neurotransmission, clarifying the significance of investigating D2/3 receptors in living brains by [11C]MNPA-PET imaging. This would be of particular significance in exploiting simultaneous modulations of glutamate receptors and a subtype of dopamine receptors as therapeutic approaches. The nearly complete abolishment of methamphetamine-induced EPSC attenuation by antagonism to D2/3 receptors supports the predominance of the D2/3 system in modulation of synaptic glutamate levels, whereas the partially persistent effects of methamphetamine on EPSC during blockage of D1/5 receptors implies roles of these receptors in regulating the gain of the response of MS neurons to the glutamatergic input. It should also be noted that the involvement of the D1/5 system in pathophysiological conditions and its relationship to the glutamatergic systems would be examined by combined PET, neurochemical, and electrophysiological assays as designed here for the D2/3 system, if an appropriate agonistic radioligand for D1/5 receptors is available.

We offer the present animal imaging system in combination with an agonistic D2/3 receptor radioligand in the hope of its applicability for the discovery and pharmacodynamic characterization of a broad range of candidate therapeutic agents capable of manipulating dopaminergic activity through the action on mGlu receptors. In this context, drugs being used in current clinical trials, including the mGlu2/3 agonist LY354740, which was shown to modulate amphetamine-induced changes of [11C]raclopride binding in a PET study for anesthetized baboons (van Berckel et al., 2006), could also be assessable in animal models and humans by using our methodology with a feasible sensitivity to endogenous dopamine levels and without concomitant anesthetic effects. The mechanistic basis of such neuroimaging investigations could be supplemented at a synaptic level by electrophysiological approaches to a specific connection in the circuitry involving dopamine neurons. To summarize, this study delineates technical and conceptual foundations of research strategy for gaining in vivo insights into the molecular signaling network converging on dopaminergic dysregulation in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for the Molecular Imaging Program, Young Scientists (18790859; M.T.), and Scientific Research on Priority Areas Research on Pathomechanisms of Brain Disorders (18023040; M.H.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan; and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. We thank T. Minamihisamatsu and J. Kamei for technical assistance.

References

- Aalto S, Hirvonen J, Kajander J, Scheinin H, Nagren K, Vilkman H, Gustafsson L, Syvalahti E, Hietala J. Ketamine does not decrease striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding in man. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164:401–406. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ametamey SM, Kessler LJ, Honer M, Wyss MT, Buck A, Hintermann S, Auberson YP, Gasparini F, Schubiger PA. Radiosynthesis and preclinical evaluation of 11C-ABP688 as a probe for imaging the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:698–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Adler CM, Weisenfeld N, Su TP, Elman I, Picken L, Malhotra AK, Pickar D. Effects of NMDA antagonism on striatal dopamine release in healthy subjects: application of a novel PET approach. Synapse. 1998;29:142–147. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199806)29:2<142::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A. The current status of the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1988;1:179–186. doi: 10.1016/0893-133x(88)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson M, Carlsson A. Interactions between glutamatergic and monoaminergic systems within the basal ganglia—implications for schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:272–276. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90108-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castner SA, Vosler PS, Goldman-Rakic PS. Amphetamine sensitization impairs cognition and reduces dopamine turnover in primate prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:743–751. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Picconi B, Baunez C, Borrelli E, Pisani A, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Cocaine and amphetamine depress striatal GABAergic synaptic transmission through D2 dopamine receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:164–175. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley RR, Kelly DL. Current status of antipsychotic treatment. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1:123–128. doi: 10.2174/1568007024606221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creese I, Sibley DR, Leff SE. Agonist interactions with dopamine receptors: focus on radioligand-binding studies. Fed Proc. 1984;43:2779–2784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming P, Wong DF, Gillings N, Hilton J, Scheffel U, Gjedde A. Specific binding of [11C]raclopride and N-[3H]propyl-norapomorphine to dopamine receptors in living mouse striatum: occupancy by endogenous dopamine and guanosine triphosphate-free G protein. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:596–604. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevich E, Erickson J, Levine L, Landbloom R, Schoepp DD, Tollefson GD. Efficacy and tolerability of an mGlu2/3 agonist in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1603–1610. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfving B, Bjørnholm B, Knudsen GM. Interference of anaesthetics with radioligand binding in neuroreceptor studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:912–915. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone RE, Kapur S, Fletcher PJ. The amphetamine-induced sensitized state as a model of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:1556–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnema SJ, Seneca N, Farde L, Shchukin E, Sóvágó J, Gulyás B, Wikström HV, Innis RB, Neumeyer JL, Halldin C. A preliminary PET evaluation of the new dopamine D2 receptor agonist [11C]MNPA in cynomolgus monkey. Nucl Med Biol. 2005a;32:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnema SJ, Seneca N, Farde L, Gulyás B, Bang-Andersen B, Wikström HV, Innis RB, Halldin C. Scatchard analysis of the D2 receptor agonist [11C]MNPA in the monkey brain using PET. Eur J Nucl Med. 2005b;32:SB2, 293. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:681–698. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini F, Lingenhohl K, Stoehr N, Flor P J, Heinrich M, Vranesic I, Biollaz M, Allgeier H, Heckendorn R, Urwyler S, Varney MA, Johnson EC, Hess SD, Rao SP, Sacaan AI, Santori EM, Velicelebi G, Kuhn R. 2-Methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), a potent, selective and systemically active mGlu5 receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gołembiowska K, Konieczny J, Wolfarth S, Ossowska K. Neuroprotective action of MPEP, a selective mGluR5 antagonist, in methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity is associated with a decrease in dopamine outflow and inhibition of hyperthermia in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:484–492. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey J, Lacey MG. Endogenous and exogenous dopamine depress EPSCs in rat nucleus accumbens in vitro via D1 receptors activation. J Physiol. 1996;492:143–154. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun W, Le Cavorsin M, Ginovart N, Zimmer L, Gualda V, Bonnefoi F, Leviel V. PET study of the [11C]raclopride binding in the striatum of the awake cat: effects of anaesthetics and role of cerebral blood flow. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0904-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichise M, Liow JS, Lu JQ, Takano A, Model K, Toyama H, Suhara T, Suzuki K, Innis RB, Carson RE. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1096–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000085441.37552.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihalainen JA, Tanila H. In vivo regulation of dopamine and noradrenaline release by α2A-adrenoceptors in the mouse nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 2004;91:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC. Glutamate and schizophrenia: phencyclidine, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors, and dopamine-glutamate interactions. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:69–108. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Balla A, Burch S, Suckow R, Xie S, Sershen H. Reversal of phencyclidine-induced dopaminergic dysregulation by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor/glycine-site agonists. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:300–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Roth RH. The neuropsychopharmacology of phencyclidine: from NMDA receptor hypofunction to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:201–225. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashihara K, Hamamura T, Okumura K, Otsuki S. Effect of MK-801 on endogenous dopamine release in vivo. Brain Res. 1990;528:80–82. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90197-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Emson PC. Intracellular recording of identified neostriatal patch and matrix spiny cells in a slice preparation preserving cortical inputs. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62:1052–1068. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.5.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles LS, Martinez D, Kochan LD, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Mawlawi O, Suckow RF, Van Heertum RL, Laruelle M. NMDA antagonist effects on striatal dopamine release: positron emission tomography studies in humans. Synapse. 2002;43:19–29. doi: 10.1002/syn.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Takacs KN, Ficker E, Kunze DL. Dopamine modulates synaptic transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2736–2744. doi: 10.1152/jn.00224.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, Heninger GR, Bowers MB, Jr, Charney DS. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langsjo JW, Maksimow A, Salmi E, Kaisti K, Aalto S, Oikonen V, Hinkka S, Aantaa R, Sipila H, Viljanen T, Parkkola R, Scheinin H. S-ketamine anesthesia increases cerebral blood flow in excess of the metabolic needs in humans. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:258–268. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A. Glutamate, dopamine, and schizophrenia: from pathophysiology to treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:138–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Adams BW. Reversal of phencyclidine effects by a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist in rats. Science. 1998;281:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Gruen RJ, Roth RH, Bunney BS, Adams RN. Effect of L-glutamate on the release of striatal dopamine: in vivo dialysis and electrochemical studies. Brain Res. 1990;518:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Adams B, Verma A, Daly D. Activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by ketamine: a novel step in the pathway from NMDA receptor blockade to dopaminergic and cognitive disruptions associated with the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2921–2927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momosaki S, Hatano K, Kawasumi Y, Kato T, Hosoi R, Kobayashi K, Inoue O, Ito K. Rat-PET study without anesthesia: anesthetics modify the dopamine D1 receptor binding in rat brain. Synapse. 2004;54:207–213. doi: 10.1002/syn.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Grant KA, Gage HD, Ehrenkaufer RL, Kaplan JR, Mach RH. PET imaging of dopamine D2 receptors with [18F]fluoroclebopride in monkeys: effects of isoflurane- and ketamine-induced anesthesia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:589–596. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Hwang DR, Slifstein M, Talbot PS, Erritzoe D, Huang Y, Cooper TB, Martinez D, Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. In vivo vulnerability to competition by endogenous dopamine: comparison of the D2 receptor agonist radiotracer (-)-N-[11C]propyl-norapomorphine ([11C]NPA) with the D2 receptor antagonist radiotracer [11C]-raclopride. Synapse. 2004;52:188–208. doi: 10.1002/syn.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi S, Suhara T, Kawabe K, Okauchi T, Maeda J, Akine Y, Onoe H, Iriki A. Functional brain mapping of monkey tool use. Neuroimage. 2001;14:853–861. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okauchi T, Suhara T, Maeda J, Kawabe K, Obayashi S, Suzuki K. Effect of endogenous dopamine on endogenous dopamine on extrastriated [(11)C]FLB 457 binding measured by PET. Synapse. 2001;41:87–95. doi: 10.1002/syn.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoe H, Inoue O, Suzuki K, Tsukada H, Itoh T, Mataga N, Watanabe Y. Ketamine increases the striatal N-[11C]methylspiperone binding in vivo: positron emission tomography study using conscious rhesus monkey. Brain Res. 1994;663:191–198. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossowska K, Konieczny J, Wolfarth S, Wieronska J, Pilc A. Blockade of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) produces antiparkinsonian-like effects in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:413–420. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page G, Peeters M, Najimi M, Maloteaux JM, Hermans E. Modulation of the neuronal dopamine transporter activity by the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 in rat striatal synaptosomes through phosphorylation mediated processes. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1282–1290. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Ndubizu O, Hamill T, Chaudhary A, Burns HD, Hargreaves R, Gibson RE. Screening cascade and development of potential positron emission tomography radiotracers for mGluR5: in vitro and in vivo characterization. Mol Imaging Biol. 2005;7:314–323. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-0005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil ST, Zhang L, Martenyi F, Lowe SL, Jackson KA, Andreev BV, Avedisova AS, Bardenstein LM, Gurovich IY, Morozova MA, Mosolov SN, Neznanov NG, Reznik AM, Smulevich AB, Tochilov VA, Johnson BG, Monn JA, Schoepp DD. Activation of mGlu2/3 receptors as a new approach to treat schizophrenia: a randomized Phase 2 clinical trial. Nat Med. 2007;13:1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/nm1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Ed 4. San Diego: Academic; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszek M, Rogoz Z, Wolfarth S, Ossowska K. Opposite influence of MPEP, an mGluR5 antagonist, on the locomotor hyperactivity induced by PCP and amphetamine. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;55:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval V, Riddle EL, Ugarte YV, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Methamphetamine-induced rapid and reversible changes in dopamine transporter function: an in vitro model. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1413–1419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01413.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarponi M, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB. Electrophysiological evidence for a reciprocal interaction between amphetamine and cocaine-related drugs on rat midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:593–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P. Dopamine receptors and the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Synapse. 1987;1:133–152. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Watanabe M, Grigoriadis D, Tedesco JL, George SR, Svensson U, Nilsson JL, Neumeyer JL. Dopamine D2 receptor binding sites for agonists. A tetrahedral model. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;28:391–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneca N, Finnema SJ, Farde L, Gulyás B, Wikström HV, Halldin C, Innis RB. Effect of amphetamine on dopamine D2 receptor binding in nonhuman primate brain: a comparison of the agonist radioligand [11C]MNPA and antagonist [11C]raclopride. Synapse. 2006;59:260–269. doi: 10.1002/syn.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin RM, Tsvetkov E, Bolshakov VY. Spatiotemporal asymmetry of associative synaptic plasticity in fear conditioning pathways. Neuron. 2006;52:883–896. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GS, Schloesser R, Brodie JD, Dewey SL, Logan J, Vitkun SA, Simkowitz P, Hurley A, Cooper T, Volkow ND, Cancro R. Glutamate modulation of dopamine measured in vivo with positron emission tomography (PET) and 11C-raclopride in normal human subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:18–25. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooren WP, Gasparini F, Bergmann R, Kuhn R. Effects of the prototypical mGlu(5) receptor antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine on rotarod, locomotor activity and rotational responses in unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;406:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai YC, Ruangma A, Rowland D, Siegel S, Newport DF, Chow PL, Laforest R. Performance evaluation of the microPET focus: a third-generation microPET scanner dedicated to animal imaging. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:455–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Higuchi M, Suhara T. The roles of extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:919–928. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada H, Harada N, Nishiyama S, Ohba H, Sato K, Fukumoto D, Kakiuchi T. Ketamine decreased striatal [11C]raclopride binding with no alterations in static dopamine concentrations in the striatal extracellular fluid in the monkey brain: multiparametric PET studies combined with microdialysis analysis. Synapse. 2000;37:95–103. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200008)37:2<95::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada H, Nishiyama S, Kakiuchi T, Ohba H, Sato K, Harada N. Ketamine alters the availability of striatal dopamine transporter as measured by [11C]β-CFT and [11C]β-CIT-FE in the monkey brain. Synapse. 2001;42:273–280. doi: 10.1002/syn.10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujike H, Sato M. Clinical features of sensitization to methamphetamine observed in patients with methamphetamine dependence and psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025:279–287. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemiya M, Raymond LA. Dopaminergic modulation of excitatory postsynaptic currents in rat neostriatal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1248–1255. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.3.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berckel BN, Kegeles LS, Waterhouse R, Guo N, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Narendran R, Van Heertum R, Laruelle M. Modulation of amphetamine-induced dopamine release by group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY354740 in non-human primates studied with positron emission tomography. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:967–977. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A, Moghaddam B. NMDA receptor antagonists impair prefrontal cortex function as assessed via spatial delayed alternation performance in rats: modulation by dopamine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:373–379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00373.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider FX, Vontobel P, Oye I, Hell D, Leenders KL. Effects of (S)-ketamine on striatal dopamine: a [11C]raclopride PET study of a model psychosis in humans. J Psychiatr Res. 2000;34:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(99)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Okada H, Shimizu K, Omura T, Yoshikawa E, Kosugi T, Mori S, Yamashita T. A high resolution animal PET scanner using compact PS-PMT detectors. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1997;44:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MR, Suzuki K. Sources of carbon which decrease the specific activity of [11C]CH3I synthesized by the single pass I2 method. Appl Radiat Isot. 2005;62:447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:13–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]