Abstract

The authors tested 2 mechanisms for the relation of movie smoking exposure with onset of cigarette smoking in adolescence. Longitudinal data with 8-month follow-up were obtained from a representative sample of 6,522 U.S. adolescents, ages 10–14 years. Structural modeling analysis based on initial nonsmokers, which controlled for 10 covariates associated with movie exposure, showed that viewing more smoking in movies was related to increases in positive expectancies about smoking and increases in affiliation with smoking peers, and these variables were both related to smoking onset. A direct effect of movie exposure on smoking onset was also noted. Mediation findings were replicated across cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Tests for gender differences indicated that girls showed larger effects of movie exposure for some variables. Implications for policy and prevention research are discussed.

Keywords: smoking, adolescents, movies, expectancies, peers

It is known that there is an effect of movie exposure to smoking cues on smoking uptake by younger adolescents; that is, youth who view more occurrences of cigarette smoking in movies are more likely to smoke. An effect of movie exposure on adolescent smoking has been shown in cross-sectional research with several populations (Hanewinkel & Sargent, 2007; Sargent et al., 2001), and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that movie exposure precedes initiation of smoking (Dalton et al., 2003; Distefan, Pierce, & Gilpin, 2004; Jackson, Brown, & L’Engle, 2007). This topic is of public health significance because a substantial proportion of early initiators go on to become dependent smokers who have great difficulty in quitting (e.g., Anthony, Warner, & Kessler, 1994; Breslau, Fenn, & Peterson, 1993). In view of the extensive exposure to smoking in movies (Sargent, Tanski, & Gibson, 2007) and the susceptibility of younger adolescents to media influences (Shadel, Niaura, & Abrams, 2002), it is important to understand how movies influence smoking during early adolescence.

An effect of movie exposure on adolescent smoking has been demonstrated with control for important covariates, variables that are correlated with movie exposure and also are related to adolescent smoking (Dalton et al., 2003; Sargent et al., 2001). So, the basic effect is not readily attributable to confounding of movie exposure with these factors. However, theoretical questions about how this effect occurs need to be addressed. A question of particular interest to addiction research is whether environmental exposures operate through a direct effect, not involving any other processes, or whether they set in motion intermediate processes that are involved in smoking onset, that is, a mediated effect (MacKinnon, 2006; MacKinnon, Taborga, & Morgan-Lopez, 2002). On the basis of work suggesting that distal exposures may operate through indirect effects (Wills et al., 2001; Wills, Pierce, & Evans, 1996), we have proposed that movie exposure will have indirect effects on adolescent smoking. In the following sections, we discuss the theoretical rationale for two types of indirect effects.

Expectancies and Affiliations

When an adolescent views persons smoking in movie situations, what ensues? One process may involve expectancies about smoking. Young persons hold beliefs about what tobacco and other substances will do for them, and these beliefs influence behavior (e.g., Stacy, Newcomb, & Bentler, 1993; Wetter, Smith, Kenford, & Jorenby, 1994). Expectancies about social facilitation (e.g., smoking will help you enjoy social situations) and relaxation effects (e.g., smoking will help calm you down when upset) have a particular importance for adolescents (DiRocco & Shadel, 2007; Wills, Sandy, & Shinar, 1999), and such cues may tend to be associated with smoking situations in movies. Thus, we could anticipate that persons who frequently view occurrences of smoking in movies would develop more positive expectancies about smoking, and this could be a factor in subsequent onset of smoking cigarettes (cf. Tickle, Hull, Sargent, Dalton, & Heatherton, 2006).

Adolescent smoking tends to be a social phenomenon, and there is reason to believe that social processes will also be involved in movie effects (Hoffman, Sussman, Unger, & Valente, 2006). The hypothesized process is that after viewing persons smoking in movies, a teen will tend to view smokers as more attractive, and hence be more inclined to socialize with persons who smoke, which is a risk factor for onset of smoking (e.g., Gerrard et al., 2002; Wills & Cleary, 1999). This is predicted to be another pathway for the impact of movie exposure on adolescent smoking.

Prospective support for part of this formulation was previously found with data from a longitudinal study with an 18-month follow-up, conducted in middle schools in Northern New England (Wills et al., in press). This study measured exposure to movie smoking in an initial survey, and an analysis was performed to examine changes in number of friends who smoked from Time 1 to Time 2 among initial nonsmokers. Persons with more movie exposure at Time 1 did show an increase in affiliation with peer smokers over time, and this increase in affiliation was significantly related to onset of smoking. A structural modeling analysis of this process showed that peer affiliation mediated part of the impact of movie exposure on smoking onset, a significant direct effect being observed also.

The Present Research

Though the finding of mediation in the prior study was suggestive, a better understanding of this effect is needed. Both conceptual replication and sample replication are needed because the sample was 95% White and from a predominantly rural region. Another issue is that there are other potential mediators, particularly cognitive factors such as expectancies. It seems unlikely that movie exposure affects only one aspect of adolescents’ functioning, so a test for cognitive as well as social processes in mediation of the movie exposure effect is needed.

In the present research, interviews were conducted by telephone with a representative national sample of younger adolescents. This longitudinal study included measures of smoking expectancies and peer affiliations and questions about movie viewing. We hypothesized that there would be two mediation pathways for the movie exposure effect, one through expectancies and one through peer affiliations, and these hypotheses were tested in a structural modeling analysis. The study had measures of several covariates, including demographics, parental relationship measures, adolescent personality characteristics, and smoking by parents and siblings. These were included in analyses so as to rule out confounding explanations for effects of media exposure by variables such as personality characteristics and family relationships (Wakefield, Flay, Nichter, & Giovino, 2003). Because of questions previously raised about cross-sectional mediation analysis (Cole & Maxwell, 2003), the hypotheses were tested in a cross-sectional mediation analysis, and effects were then tested for replication in a longitudinal mediation analysis. In view of previous suggestions of gender differences in adolescent smoking and advertising effects (DiRocco & Shadel, 2007; Vidrine, Anderson, Pollak, & Wetter, 2006), we also conducted multiple-group analyses in structural equation modeling to determine whether effects of movie exposure were comparable for girls and boys.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The participants were a U.S. national sample of 6,522 adolescents, ages 10–14 years (M = 12.05, SD = 1.39). The baseline sample was 49% female, and ethnic distribution was 11% African American, 19% Latino, 62% Caucasian, and 8% mixed/“other” ethnicity. With regard to parental education, 40% of the participants had parents with education through high school completion, 29% had parents with some college education, and 31% had parents who were college graduates. On a 6-point scale for household income (anchor points $10,000 or less and $75,000 or more), the mean income level was 4.23 (SD = 1.60), representing a household income in the range from $30,000 to $50,000. With regard to urbanicity, 31% of the participants were inner-city residents in a Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA), 48% were in the outer part of an SMSA (i.e., suburban), and 21% resided outside of an SMSA (i.e., rural).

The sample was recruited through random digit dialing. Participants were interviewed by telephone with a structured protocol, lasting approximately 20 min, which contained questions about media exposures, cigarette smoking, and other variables. We obtained parental consent and adolescent assent prior to interviewing each respondent. A Certificate of Confidentiality protected the privacy of responses, which is conducive to validity of self-reports (Wills & Cleary, 1997). All aspects of the survey were approved by the institutional review boards at Dartmouth Medical School and the survey research firm (Westat, Rockville, MD). The completion percentage for the survey was 66%. To confirm that the sample was representative, we compared the distributions of age, gender, ethnicity, household income, and census region in our unweighted sample with those of the 2000 U.S. Census and showed they were almost identical (see Sargent et al., 2005).

After the baseline interview, the participants were recontacted 8 months later. Of the 6,522 baseline participants, 5,503 (84%) participated in the second survey. There was some differential attrition, as is typical in longitudinal studies of adolescents (Newcomb & Bentler, 1988; Wills, Walker, & Resko, 2005). Persons who dropped out did not differ significantly on baseline smoking status, smoking expectancies, friends smoking, family relationship variables, or adolescent personality variables. Likelihood of dropout was higher for persons who had more movie exposure, had parents who smoked, were from families with less education and income, and were of minority (African American or Hispanic) ethnicity. In a multivariate analysis, these variables together accounted for only 3% of the variance in attrition, so the magnitude of the attrition effect was modest, and the continuing sample was similar in characteristics to the baseline sample. The present analysis is restricted to persons who were nonsmokers at baseline (N = 5,829); that is, they had never puffed on a cigarette. Of these, 4,932 (85%) participated in the follow-up survey, and they form the basis for the longitudinal analysis.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic characteristics of participants were assessed at baseline with items on gender (0 = male, 1 = female), ethnicity (eight options), and family structure (three options). Parents answered questions about parental education, household income, and residence ownership. Coding of census tract data was used to index urbanicity and region of the United States.

Movie smoking exposure

Adolescents’ exposure to movie smoking was assessed at baseline using previously validated methods (Sargent et al., 2001). Participants were presented with a list of titles of 50 movies, randomly drawn from a population of 532 recent movies that were popular at the box office and likely to be of interest to adolescents. We selected the top 100 U.S. box-office hits per year for each of the 5 years preceding the baseline survey (1998–2002, N = 500), and 32 movies that earned at least $15 million in gross U.S. box-office revenues during the first 4 months of 2003. (Older movies were included because adolescents often watch these movies on DVDs.) The sample of 50 movies that each participant received was stratified on Motion Picture Association of America ratings to reflect the distribution of the full sample of movies (19% G/PG, 41% PG-13, 40% R). Participants were asked (no/yes) whether they had seen each movie; it has previously been demonstrated that adolescents have good reliability for recalling movies they have seen and have low false-positive rates in reporting having viewed fictitious or unavailable films (Dalton et al., 2002; Sargent et al., 2001). The movies were coded independently for occurrences of smoking by a group of trained coders using a standardized protocol. A smoking occurrence was counted whenever a major or minor character handled or used tobacco in a scene or when tobacco use was depicted in the background (e.g., “extras” smoking in a bar scene). Occurrences were counted irrespective of the scene’s duration or how many times the tobacco product appeared during the scene; most tobacco use involved cigarettes or cigars, with less than 1% of occurrences involving spit tobacco. A methodological check for a 10% subsample of movies indicated the interrater correlation for number of smoking occurrences was .96, and the mean kappa for coder agreement on whether smoking was occurring in 1-s intervals was 0.86 (SD = .17), both statistics indicating good coding reliability (Wills et al., in press). The number of occurrences of smoking in the movies that an individual participant had seen (from the list of 50) was recorded as that participant’s list-specific score, and an extrapolated score was computed to represent the number of occurrences of smoking the participant would have seen with his or her viewing habits from the entire population of 532 movies (Dalton et al., 2003). For analysis, the score was censored at the 99th percentile to reduce the influence of some high-leverage outliers.

Covariates

In addition to demographics, covariates were chosen on the basis of likely correlations with movie exposure and with adolescent smoking. Measures were adapted from previous research (Sargent et al., 2001; Wills et al., 2001), and responses were recoded if necessary such that a higher score reflects more of the named quantity. Measures of parenting were a nine-item scale tapping mother’s warmth and responsiveness (e.g., “She listens to what I have to say” and “She makes me feel better when I’m upset,” Cronbach’s α = 0.71), and a seven-item scale on mother’s demandingness and rules (e.g., “She checks to see if I do my homework,” “She has rules for what I can do,” and “She knows where I am after school”; α = 0.59). Adolescent personality characteristics were a six-item scale on Rebelliousness (Sargent et al., 2001), which tapped tendency toward antisocial behavior (e.g., “I like to break the rules” and “I argue a lot with other kids”; α = 0.73); a four-item scale on Sensation Seeking (Stephenson, Hoyle, Slater, & Palmgreen, 2003), which had items such as “I like to do scary things” and “I like loud music” (α = 0.59); a four-item measure of self-esteem based on the Rosenberg scale (e.g., Rosenberg & Pearlin, 1978; “I like myself the way I am” and “I’m happy with how I look”; α = 0.64); and a four-item measure on Self-Control based on the Kendall-Wilcox scale (Kendall & Wilcox, 1979; e.g., “I’m good at waiting my turn” and “I have to be reminded several times to do things”; α = 0.42). Measures of parental and sibling smoking were obtained through items asking the participant whether his or her mother or father, or older sibling, smoked cigarettes. These were recoded for analysis to a 3-point scale for parental smoking (0 = no parent smokes, 1 = one parent smokes, 2 = two parents smoke) and a dichotomous index for sib smoking (no sibling smokes vs. sibling smokes). School performance was indexed with the question “How would you describe your grades last year?” Response points were below average, average, good, and excellent. Because of small cell frequency at the lowest response point, this measure was recoded to a 3-point scale.

Smoking expectancies

Smoking expectancies were assessed at both time points. Two items followed the lead-in, “Please tell me how you feel about the following statements.” The items were “I think I would enjoy smoking” and “I think smoking would be relaxing.” Responses were on 4-point scales ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The items were inter-correlated (r = .45 and .52 at Waves 1 and 2, respectively) and accordingly combined in a composite score.

Peer smoking

Affiliation with peer smokers was assessed at both time points with an item that asked, “How many of your friends smoke cigarettes?” This had a 3-point response scale (1 = none, 2 = some, 3 = most).

Adolescent smoking

The criterion measures, obtained at both time points, were two items on cigarette smoking. First, the participant was asked the question “Have you ever tried smoking a cigarette, even just a puff?” Response points were 0 = no and 1 = yes. Those who answered affirmatively to the first question were then asked “How many cigarettes have you smoked in your life?” Responses to the second item were on a 4-point scale (1 = just a few puffs, 2 =1–19 cigarettes, 3 = 20–100 cigarettes, 4 = more than 100 cigarettes). From these two items, a 5-point score could be constructed for each participant such that a 0 represented never smoked and a 4 represented a lifetime smoking experience of more than 100 cigarettes.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Data from the baseline survey showed that 89% of the sample were nonsmokers, and 11% were smokers. Of the latter, 7% had only puffed on a cigarette, 2% had smoked 1–19 cigarettes, <1% had smoked 20–100 cigarettes, and < 1% had smoked more than 100 cigarettes. Data for the Wave 2 survey indicated 86% of the sample were nonsmokers, and 14% were smokers. Of the latter, 9% had puffed, 3% had smoked 1–19 cigarettes, 1% had smoked 20–100 cigarettes, and 1% had smoked more than 100 cigarettes. Thus, there was a significant increase in smoking over the follow-up period. With regard to familial smoking, baseline data showed there was no parental smoking for 66% of participants, 22% had one parent who smoked, and 12% had two parents who smoked. Sibling smoking was reported by 15% of the participants.

Data on peer smoking from the baseline survey indicated that 78% of participants had no friends who smoked, 19% had some friends who smoked, and 3% said most of their friends smoked. At the Wave 2 survey, these figures were 69%, 26%, and 5%, respectively, so there was also an increase in peer smoking over the study period. Data on expectancies showed generally low levels in the sample. At baseline, 85% and 86% of participants indicated no positive expectancy for enjoyment and relaxation, respectively, 11%–12% indicated a little, and 2% indicated more positive expectancies. At the Wave 2 survey, the comparable figures were 78%–80% none, 16%–17% a little, and 3%–5% more positive, so there was also an increase in smoking expectancies over the follow-up period.

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1 for the subsample of persons who were nonsmokers at baseline and were followed up at Wave 2. Absolute levels were generally high for measures of mother’s responsiveness and demandingness and for adolescents’ self-esteem and self-control. Responses were shifted toward the upper end of the dimensions, but skewnesses were moderate, with the sign of the coefficients negative by convention. Levels for rebelliousness and sensation seeking tended to be low; the positive skewness coefficients for the variables reflect distributions shifted toward the lower end of the dimensions, but skewness values were in the moderate range. Data on movie viewing indicated that, on average, participants had seen 12 movies from the random lists of 50 presented; on average, the movies they had viewed contained 56 occurrences of smoking. With the participants’ viewing habits, this translates into an expected average exposure to 594 occurrences of smoking from the population of movies identified for the study.

Table 1.

Descriptives for Longitudinal Sample

| Range | M | SD | Skew | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variable | ||||

| Mother responsiveness | 9–36 | 29.61 | 4.02 | −0.91 |

| Mother demandingness | 7–28 | 23.47 | 3.41 | −0.80 |

| Rebelliousness | 6–24 | 8.38 | 2.39 | 1.50 |

| Sensation seeking | 4–16 | 7.70 | 2.37 | 0.68 |

| Self-esteem | 4–16 | 13.18 | 2.20 | −0.81 |

| Self-control | 4–16 | 12.13 | 1.91 | −0.32 |

| School performance | 1–3 | 2.10 | 0.75 | −0.16 |

| Movies seen | 0–49 | 11.98 | 6.82 | 0.91 |

| Movie smoking exposurea | 0–408 | 55.87 | 51.97 | 1.58 |

| Expected smoking exposureb | 0–2,493 | 594.27 | 527.88 | 1.24 |

| Mediator | ||||

| Friends smoking 1 | 1–3 | 1.17 | 0.41 | 2.31 |

| Friends smoking 2 | 1–3 | 1.29 | 0.52 | 1.58 |

| Smoking expectancies 1 | 2–8 | 2.25 | 0.65 | 3.06 |

| Smoking expectancies 2 | 2–8 | 2.41 | 0.82 | 2.27 |

Note. N = 4,932. Data are for persons who were nonsmokers at Wave 1 and were followed up at Wave 2. Variables are from Wave 1 unless otherwise indicated.

Occurrences viewed in random lists of 50 presented.

Expected occurrences from population of 532 movies.

Correlations of the study variables in baseline data as computed in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2005), with the score for adolescent smoking as criterion variable, are presented in Table 2. Categorical specification was used for friends smoking (three levels), smoking expectancies (collapsed to five levels because of small cell sizes at the upper end of the distribution), and adolescent smoking (five levels). The expectation-maximization algorithm was used to include missing data, and the analysis was performed for the sample of 6,522 cases using weighted least squares estimation.1 There was more exposure to smoking in movies for participants who were older, boys, higher on rebelliousness and sensation seeking and lower on self-esteem, and for those who had parents or siblings who smoked. Conversely, movie smoking exposure was lower among participants who had better self-control; were doing better in school; and whose parents had higher responsiveness, demandingness, and education. These data show that exposure to movie smoking is related to both adolescent personality and familial variables, and there were substantial correlations among the covariates. It should also be noted that all the covariates were significantly related to adolescent smoking with one exception (gender). In the structural modeling analysis, the correlations of movie exposure with these covariates were removed statistically, so the observed effect for movie exposure is not confounded with any of these variables.

Table 2.

Correlations of Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Movie exposure | — | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Age | .38 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Gender | −.12 | .01 | — | |||||||||||||

| 4. SES | −.04 | .01 | .02 | — | ||||||||||||

| 5. Mother responsiveness | −.17 | −.14 | .07 | .13 | — | |||||||||||

| 6. Mother demandingness | −.17 | −.18 | .07 | .01 | .47 | — | ||||||||||

| 7. Rebelliousness | .28 | .19 | −.21 | −.10 | −.42 | −.29 | — | |||||||||

| 8. Sensation seeking | .36 | .22 | −.10 | −.09 | −.31 | −.20 | .49 | — | ||||||||

| 9. Self-esteem | −.07 | −.10 | −.08 | .07 | .35 | .28 | −.28 | −.21 | — | |||||||

| 10. Self-control | −.15 | −.13 | .15 | .04 | .34 | .29 | −.52 | −.35 | .30 | — | ||||||

| 11. School performance | −.15 | −.14 | .12 | .20 | .22 | .17 | −.33 | −.24 | .24 | .33 | — | |||||

| 12. Parent smoking | .18 | .03 | −.01 | −.26 | −.11 | −.06 | .17 | .20 | −.07 | −.11 | −.16 | — | ||||

| 13. Sib smoking | .17 | .11 | .01 | −.12 | −.08 | −.06 | .12 | .13 | −.06 | −.08 | −.12 | .22 | — | |||

| 14. Smoking expectancies | .19 | .16 | −.05 | −.07 | −.24 | −.23 | .32 | .22 | −.19 | −.21 | −.13 | .13 | .13 | — | ||

| 15. Friend smoking | .33 | .36 | −.01 | −.12 | −.24 | −.20 | .34 | .31 | −.17 | −.21 | −.21 | .20 | .20 | .33 | — | |

| 16. Adolescent smoking | .24 | .24 | −.02 | −.09 | −.18 | −.16 | .33 | .25 | −.14 | −.21 | −.17 | .22 | .22 | .43 | .43 | — |

Note. Correlations are for Wave 1 data. SES = socioeconomic status; Sib = Sibling. Approximate significance levels are r > |.05|, p < .01. r > |.07|, p <.0001.

Longitudinal Mediation Analysis

The hypothesis that effects of movie smoking exposure are mediated through changes in expectancies and peer affiliations was tested in a longitudinal structural equation model, specified with movie smoking exposure at Wave 1 as exogenous (i.e., not predicted by any prior construct in the model) and the hypothesized mediators at Wave 2 as endogenous (i.e., could be predicted by prior constructs in the model). The analysis was conducted for the subsample of persons who were nonsmokers at Wave 1 and the criterion variable was the dichotomous index of smoking status at Wave 2, so any effects to this variable represent predictors of smoking onset. All of the constructs in the analysis were manifest variables (i.e., had only one indicator). Covariates from Wave 1 (demographics, parenting measures, adolescent personality measures, familial smoking measures, and school performance) were specified as exogenous together with the movie smoking score, so as to control statistically for any correlation of movie exposure with these variables. The model was specified with Wave 1 measures for expectancies and peer smoking included as covariates, so any paths to Wave 2 measures for these constructs represent predictors of change in expectancies or affiliations. The structural model was analyzed in Mplus with categorical specification for friends smoking, which had three levels, smoking expectancies, which had five levels, and adolescent smoking, which had two levels.

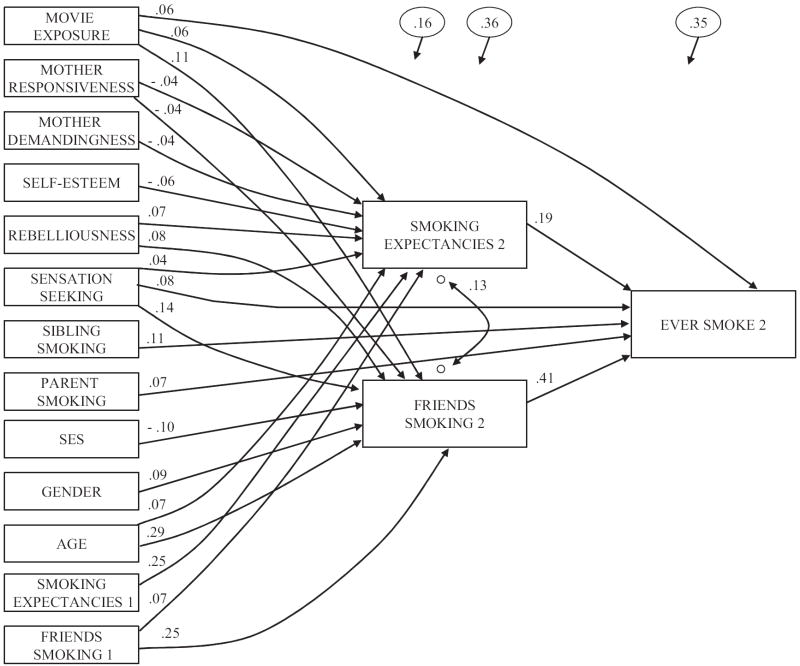

The model was estimated using weighted least squares estimation with robust standard errors; some cases were dropped because with this method, any case with missing data on an exogenous variable is excluded from the analysis. The final structural model, after dropping two variables with no significant effects (self-control and poor school performance) and several nonsignificant paths, had a chi-square (df = 21, N = 4,203) of 27.08, comparative fit index (CFI) of .99, and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) of .008, all these parameters indicating good fit to the data. The model is presented in Figure 1 with standardized values for all coefficients. Correlations among exogenous variables, included in the model but excluded from the figure for graphical simplicity, are indicated in Table 2. In the structural model, the residual correlation between smoking expectancies and affiliation with peer smokers was .13, so although these were positively related, they were not redundant constructs. In the model, the exogenous variables accounted for 16%–36% of the variance in the mediators, and together the variables in the model accounted for 35% of the variance in smoking onset.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal structural model for movie smoking exposure, mediators, and smoking onset. Variables are from Time 1 unless otherwise noted. Straight single-headed arrows indicate path effects, curved double-headed arrow indicates covariance. Values are standardized coefficients; all coefficients are significant (p < .05). Values in circles at top of figure are squared multiple correlations, the variance accounted for in a given construct (which the arrow points to) by all constructs to the left of it in the model. SES = socioeconomic status.

The results showed that both of the mediation hypotheses were supported. (Results reported here are all independent effects and are significant at p < .0001 unless otherwise noted.) Significant paths were found from movie smoking exposure to increase in positive expectancies about smoking and to increase in affiliation with peer smokers, and there were significant paths from expectancies and affiliations to adolescent smoking onset. There was also a direct effect of movie exposure on smoking onset (p < .05). Tests for the significance of the indirect effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004) indicated the effect of movie exposure through change in friend smoking was significant (critical ratio [CR] = 4.85, p < .0001), as was the effect through change in expectancies (CR = 3.51, p = .001). These results support the reasoning behind the mediation predictions and show that there are two different pathways for the movie effect, one through a cognitive process and one through a social process.2

Additional findings for the covariates were noted in the structural model. Maternal responsiveness had inverse paths to changes in expectancies about smoking and affiliation with peer smokers (p < .05), and inverse paths to change in expectancies were found for adolescent self-esteem and maternal demandingness (p < .05). Personality characteristics were salient in the model, with rebelliousness and sensation seeking (p < .05) positively related to change in smoking expectancies, and rebelliousness and sensation seeking also positively related to change in affiliation with peer smokers; in addition, sensation seeking had a direct effect on smoking onset (p < .01). Familial smoking was a significant factor, as both sibling smoking and parental smoking (p < .01) had direct effects on smoking onset. These effects were obtained controlling for the correlations of the covariates with each other and with the demographic variables, which also had significant effects. Age had positive paths to changes in expectancies and peer affiliations. Female gender was positively related to change in affiliation with peer smokers, whereas parental socioeconomic status was inversely related to this variable.

Tests for Gender Differences

Because of the possibility that girls and boys react differently to media exposures, we performed analyses to determine whether effects of movie exposure in the structural model differed by gender. Multiple-group analyses were conducted in which the structural model in Figure 1 (excluding gender) was analyzed for both genders. Covariance matrices were computed for boys and girls separately and were input to a multiple-group procedure in which the model was analyzed simultaneously in both groups with all parameters freely estimated.

Parameters from the multiple-group model are reported by gender in Table 3. Constraints were imposed on coefficients, and the difference in fit from the base model (with 1 df) was used to evaluate whether a coefficient differed significantly across gender groups. Nested tests were performed using a procedure outlined in Muthén and Muthén (2005, chap. 15) because with weighted least squares estimation, the difference in fit statistics is not distributed as chi-square. In the longitudinal model, the path from movie exposure to change in friends use was larger for girls, but the difference was not significant, Δχ2(1) = 3.23, p = .07. The path from expectancy change to smoking onset was larger among girls, and the difference chi-square (1 df) of 5.09 (p = .02) indicated these two paths differed significantly.3 Hence, there was some evidence of gender differences, but given the number of tests performed, these results should be interpreted with caution and need to be tested for replication.

Table 3.

Coefficients in Structural Model for Girls and Boys

| Girls |

Boys |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | b | SE | b | SE |

| Movie exposure = > Expectancy change | .129* | .066 | .170** | .062 |

| Movie exposure = > Friend use change | .350**** | .072 | .178**** | .065 |

| Movie exposure = > Smoking onset | .135 | .096 | .117 | .087 |

| Expectancy change = > Smoking onseta | .360**** | .044 | .221**** | .043 |

| Friend use change = > Smoking onset | .330**** | .042 | .319**** | .043 |

Note. Values are unstandardized coefficients.

Coefficients differ for girls and boys by 1-df test, p < .05.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

Discussion

This research tested the relation of movie smoking exposure to onset of cigarette smoking with longitudinal data from a representative sample of younger adolescents. We used a rigorous procedure to assess exposure to smoking cues in movies and assessed individual and familial variables that presented possible confounds in determining the impact of movie exposure on adolescent behavior. The results showed that higher exposure to movie smoking was related to greater likelihood of smoking onset, controlling for a number of covariates. These findings were obtained in a diverse sample of adolescents with control for a range of demographic characteristics.

The aim of this research was to learn more about how the effects of movie exposure are mediated. We found in a longitudinal structural modeling analysis that the effect of movie exposure was mediated through smoking expectancies and peer affiliations. Persons who viewed more smoking in movies showed an increase in positive expectancies about smoking and an increase in affiliation with peers who smoked, and these changes were factors in smoking onset. Prior prospective research with younger adolescents has shown that expectancies and affiliations influence uptake of substance use rather than the converse (e.g., Henry, Slater, & Oetting, 2005; Wetter et al., 2004; Wills & Cleary, 1999), consistent with the temporal relations specified in the present structural model. The results also showed protective indirect effects through these mediators for higher socioeconomic status, positive parenting practices, and adolescent self-esteem; risk promoting mediated effects for age, rebelliousness, and sensation seeking, and direct effects on smoking onset for sensation seeking and familial smoking. From a methodological standpoint, it should be noted that findings from the longitudinal analysis of mediation were almost identical to findings from a cross-sectional analysis (cf. Cole & Maxwell, 2003).

There are some possible limitations that should be noted. The measures in this study were relatively simple ones, some of lower reliability, but the sample size provided adequate power to detect hypothesized effects. The completion rate was moderate, and there was differential attrition from the panel as is typical in longitudinal studies of adolescents (Wills et al., 2005). Though the scope of the attrition effects was modest, there may be some qualification to the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the mediation results are based on two assessments, and research with three or more waves of data may help to provide more detail about temporal relations between constructs.

Theoretical Perspective

From a theoretical standpoint, the findings on mediation give a more articulated perspective on media effects. There are reasonable grounds for seeing modeling as an explanation for movie exposure effects; social influence effects are prominent in adolescent substance use (Gibbons et al., 2004; Kobus, 2003), and it is plausible that teenagers view people smoking in dramatic portrayals and think, “I might like to try that” (Gibbons, Gerrard, & Lane, 2003). However, there are some difficulties with a simple modeling explanation because the behaviors shown in movies are performed by fairly different people (e.g., they are typically older) and in different life contexts than most teenagers inhabit. So a simple modeling formulation might account for part of the effect of movie smoking on adolescent behavior but there may be other relevant processes.

The present data indicate more complex effects than simple modeling because they show that viewing smoking in movies sets in motion a number of processes. Some are cognitive: Viewers who frequently see smoking portrayed onscreen tend to have more positive beliefs about cigarettes being enjoyable and relaxing. In addition, it appears that movie exposure sets social processes in motion, such that persons who see a lot of smoking situations in movies are susceptible to a dynamic of increased affiliation involving peer smokers. So the message of the present data is that movie exposure activates several processes. The data demonstrate that effects of movie exposure are mediated in part through both cognitive and social processes, though it is possible that other processes operate as well.

The present research was somewhat limited in the sense that we only used a global assessment of exposure to smoking in movies and did not analyze the movie situations and characters that provided the exposure. This does not rule out the possibility that favorite movie stars have a direct impact on viewers when they are perceived as attractive and similar (Distefan et al., 2004). For example, one actress has been noted as an influence on youth, with a female teen remarking in an interview “Whenever I think of how to smoke, it’s the way Sarah Jessica Parker exhales, and I’m like obsessed … I love her, and the way she exhales is very memorable” (Colangelo, 2006). Studies may provide attention to the impact of smoking by particular types of movie characters (e.g., largely positive vs. largely unattractive characters) and the situations in which smoking occurs (e.g., relaxing, social vs. tense, individual), and how these exposures interact with personality characteristics of viewers (e.g., neuroticism, sensation seeking). Such research may require large samples or controlled laboratory situations (e.g., DiRocco & Shadel, 2007) in order to get at interactional influences and targeted effects (cf. Pierce, Lee, & Gilpin, 1994; Tickle, Sargent, Dalton, Beach, & Heatherton, 2001). Such research may be pursued in concert with epidemiological investigations that help to delineate the overall effects of movie exposures on adolescent behavior.

Issues for Prevention Research

The present research demonstrated several processes in movie effects, but additional questions can be raised. This study used rather simple measures of expectancies and peer affiliations, but in principle, these are complex constructs, and effects of media exposures need to be addressed for additional dimensions such as cognitive perceptions of smoking risk (Gerrard, Gibbons, & Gano, 2003) and the impact of behavior by close friends versus behavior by persons with more distant social relationships (Urberg, Degirmencioglu, & Pilgrim, 1997). In addition, there is a question about the direct effect for movie exposure. Presently, we cannot entirely account for the movie effect, and consideration of other processes needs to be pursued. Techniques from cognitive research could be used to understand better how movie exposure might increase the availability of smoking cues or the perceived normativeness of smoking (Stacy & Weirs, 2006). There is a question about how the impact of social influences differs by ethnicity (e.g., Gerrard & Gibbons, 2006; Robinson et al., 2006; Unger et al., 2001). More work is needed to understand how movie exposures relate to the social networks of adolescents and how they may change the dynamics of network structures. For example, if one member of a network starts watching a lot of R-rated movies or starts smoking, how does this affect the viewing preferences and smoking behavior of other members of his or her network (Valente, Gallaher, & Mouttapa, 2004)? Such work can help increase researchers’ understanding of the social and cognitive worlds of adolescents.

In considering public health implications, the effect sizes noted here could be characterized in Cohen’s (1988) terms as modest ones, but it should be noted that the partialled effect sizes observed here for movie exposure are comparable to those observed for variables that are typically characterized as significant influences on adolescent smoking (e.g., sensation seeking and parental smoking). The results indicate that the movie effect has the same relevance as these other risk factors, considered in a multivariate context. Because the amount of exposure to smoking that adolescents receive through movies is substantial (Charlesworth & Glantz, 2005; Sargent et al., 2007) and almost all adolescents are exposed to some extent, from a public health standpoint, the population-attributable risk is substantial because it is spread throughout the population. Although we focused on mediators of smoking initiation in the present research, it has recently been found that movie exposure also promotes established smoking and the attendant risk of smoking-related morbidity (Sargent et al., 2007). Thus, social policies and individual-level interventions aimed at reducing movie smoking exposure seem like a promising avenue to pursue toward the aim of reducing smoking in adolescence (Austin, Chen, Pinkleton, & Johnson, 2006; Brown, 2006; Sargent, Dalton, Heatherton, & Beach, 2003).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant R01 CA77026 awarded to James D. Sargent and National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01 DA12623 awarded to Thomas A. Wills. We thank the participating parents and adolescents for their cooperation.

Footnotes

From the set of demographic indices, three variables (family structure, household income, and ethnicity) were dropped because in preliminary analyses, they did not show significant unique contributions to movie exposure and/or baseline smoking.

A cross-sectional mediation analysis within Wave 1 data had the same predictor and covariates, with the adolescent smoking score as criterion. This model had a chi-square (df = 15, N = 5,480) of 63.21, CFI of .97, and RMSEA of .024, indicating reasonable fit to the data. There were significant paths from movie exposure to smoking expectancies (β = .10) and friends smoking (β = .15) and from these variables to current adolescent smoking level (βs = .27 and .32, respectively). There was also a direct effect from movie exposure to adolescent smoking (β = .05). Tests of the indirect effects for movie exposure on adolescent smoking showed the indirect effect through friends’ smoking was significant (CR = 6.75, p < .0001), as was the indirect effect through expectancies (CR = 4.51, p < .0001). Thus, the cross-sectional mediation findings were quite similar to results in the longitudinal model.

In the cross-sectional model, the direct effect of movie exposure on current smoking level was significant for girls (b = .237, SE = .039, p < .001) but not for boys (b = .037, SE = .068, ns), and these coefficients differed significantly (p < .05) by a 1-df test.

Contributor Information

Thomas A. Wills, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University

James D. Sargent, Department of Pediatrics, Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center

Mike Stoolmiller, College of Education, University of Oregon.

Frederick X. Gibbons, Department of Psychology, Iowa State University

Meg Gerrard, Department of Psychology, Iowa State University.

References

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, and other substances. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Chen Y-C, Pinkleton BE, Johnson JQ. Benefits and costs of Channel One in a middle school setting and the role of media-literacy training. Pediatrics. 2006;117:423–433. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Fenn N, Peterson EL. Early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in a cohort of young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1993;33:129–137. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90054-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD. Media literacy has potential to improve adolescents’ health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:459–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: A review. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1516–1528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo LL. Sex and the ciggie: Teen girls drawn to smoking by former HBO hit. New York Daily News. 2006 August 10;:2. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff L, Gibson JJ, Ahrens MB, et al. Effects of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: A cohort study. The Lancet. 2003;362:281–285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. The prevalence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988 to 1997. Preventive Medicine. 2002;34:516–523. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiRocco DN, Shadel WG. Gender differences in adolescents’ responses to themes of relaxation in cigarette advertising. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distefan JM, Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. Do favorite movie stars influence adolescent smoking initiation? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1239–1244. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Trajectories of drug use among African American adults and adolescents; Paper presented at the NIDA Conference on Racial/Ethnic Differences in Substance Use; Rockville, MD. 2006. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Gano M. Adolescents’ risk perceptions and behavioral willingness: Implications for intervention. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M, Trudeau L, Vande Lune L, Buunk BP. Inhibitory effects of drinker and nondrinker prototypes on adolescent alcohol consumption. Health Psychology. 2002;21:601–609. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ. A social reaction model of adolescent health risk. In: Suls JM, Wallston KA, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers; 2003. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Vande Lune LS, Wills TA, Brody GH, Conger RD. Context and cognitions: Environmental risk, social influence, and adolescent substance use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1048–1061. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in popular contemporary movies and youth smoking in Germany. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Slater MD, Oetting ER. Alcohol use in early adolescence: The effect of changes in perceived harm and friends’ alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:275–283. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BR, Sussman S, Unger J, Valente TW. Peer influences on adolescent cigarette smoking: A theoretical review. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41:103–155. doi: 10.1080/10826080500368892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Brown JB, L’Engle KL. R-rated movies, bedroom television, and initiation of smoking by White and Black adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:260–268. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Wilcox LE. Self-control in children: Development of a rating scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:1020–1029. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 1):37–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence intervals for the indirect effect. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Taborga MP, Morgan-Lopez AA. Mediation designs for tobacco prevention research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68(Suppl 1):S69–S83. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus version 3.0 user’s guide. Los Angeles: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Impact of adolescent drug use and social support on problems of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:64–75. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Lee L, Gilpin EA. Smoking initiation by adolescent girls, 1944 through 1988: An association with targeted advertising. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271:608–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LA, Murray DM, Alfano CM, Zbikowski SM, Blitstein JL, Klesges RC. Ethnic differences in predictors of adolescent onset and escalation: A longitudinal study from 7th to 12th grade. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8:297–307. doi: 10.1080/14622200500490250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M, Pearlin L. Social class and self-esteem among children and adults. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84:53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Meija AM, Gibson JJ, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Carusi CP, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: Its relation to smoking among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Mott LA, Tickle JJ, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. Effect of seeing tobacco use in films on trying smoking among adolescents: Cross sectional study. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(7326):1394–1397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Heatherton TF, Beach ML. Modifying exposure to movie smoking: A novel approach to preventing adolescent smoking. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:643–648. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.7.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Worth KA, Dal Cin S, Wills TA, Gibbons FX, et al. Exposure to smoking depictions in movies: Association with established smoking. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:849–856. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Tanski SE, Gibson J. Exposure to movie smoking among US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years: A population estimate. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1167–1176. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Adolescents’ reactions to the imagery displayed in smoking advertisements. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:173–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Cognitive motivations as long-term predictors of drinking problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1993;12:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Weirs RW. Common themes and new directions in implicit cognition and addiction. In: Weirs RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson M, Hoyle R, Slater M, Palmgreen P. Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large-scale surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;72:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickle JJ, Hull JG, Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Heatherton TF. A structural equation model of social influences and exposure to media smoking on adolescent smoking. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2006;28:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, Heatherton TF. Favorite movie stars, their tobacco use in contemporary movies, and its association with adolescent smoking. Tobacco Control. 2001;10:16–22. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Cruz TB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Howard KA, Palmer PH, Johnson CA. Ethnic variation in peer influences in adolescent smoking. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2001;3:167–176. doi: 10.1080/14622200110043086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:834–844. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Gallaher P, Mouttapa M. Using social networks to understand and prevent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39:1685–1712. doi: 10.1081/ja-200033210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidrine JI, Anderson CB, Pollak KI, Wetter DW. Gender differences in adolescent smoking: Mediator and moderator effects of self-generated expected smoking outcomes. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2006;20:383–387. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.6.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield M, Flay BR, Nichter M, Giovino G. Role of the media in influencing trajectories of adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 1):79–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Welsch SK, Smith SS, Fouladi RT, Fiore MC. Transitions in smoking behavior among college students. Health Psychology. 2004;23:168–177. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Smith SS, Kenford SL, Jorenby DE. Smoking expectancies: Predictive and discriminant validity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:801–811. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. The validity of self-reports of smoking: Analyses by ethnicity in a sample of urban adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:56–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. Peer and adolescent substance use among 6th–9th graders: Influence versus selection mechanisms. Health Psychology. 1999;18:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD, Filer M, Shinar O, Mariani J, Spera K. Temperament and self-control related to early-onset substance use. Prevention Science. 2001;2:145–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1011558807062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Pierce JP, Evans RI. Large-scale environmental risk factors for substance use. American Behavioral Scientist. 1996;39:808–822. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O. Substance use level and problems in late adolescence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:122–134. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Worth KA, Dal Cin S. Movie exposure to smoking cues and adolescent smoking onset: A test for mediation through peer affiliations. Health Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.769. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Walker C, Resko JA. Longitudinal studies of drug use. In: Sloboda Z, editor. Epidemiology of drug abuse. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]