Abstract

Neuroblastoma and its benign differentiated counterpart, ganglioneuroma, are paediatric neuroblastic tumours arising in the sympathetic nervous system. Their broad spectrum of clinical virulence is mainly related to heterogeneous biologic background and tumour differentiation. Neuroblastic tumours synthesize various neuropeptides acting as neuromodulators. Previous studies suggested that galanin plays a role in sympathetic tissue where it could be involved in differentiation and development. We investigated the expression and distribution of galanin and its three known receptors (Gal-R1, Gal-R2, Gal-R3) in 19 samples of neuroblastic tumours tissue by immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization and fluorescent-ligand binding. This study provides clear evidence for galanin and galanin receptor expression in human neuroblastic tumours. The messengers coding for galanin, Gal-R1 and -R3 were highly expressed in neuroblastoma and their amount dramatically decreased in ganglioneuroma. In contrast, Gal-R2 levels remained unchanged. Double labelling studies showed that galanin was mainly co-expressed with its receptors whatever the differentiation stage. In neuroblastic tumours, galanin might promote cell-survival or counteract neuronal differentiation through the different signalling pathways mediated by galanin receptors. Finally, our results suggest that galanin influences neuroblastoma growth and development as an autocrine/paracrine modulator. These findings suggest potential critical implications for galanin in neuroblastic tumours development.

British Journal of Cancer (2002) 86, 117–122. DOI: 10.1038/sj/bjc/6600019 www.bjcancer.com

© 2002 The Cancer Research Campaign

Keywords: galanin, receptor, neuroblastic tumour, neuroblastoma, differentiation, sympathetic nervous system

Neuroblastomas (NB) and neuroblastic tumours (NT) are the most common extracranial malignant tumours in childhood (Brodeur et al, 1993). These embryonal malignancies derived from the sympathoadrenal lineage of the neural crest show a wide spectrum of differentiation, maturation and organization of neuroblasts and Schwann cells. Thus, at one end of the spectrum there are undifferentiated NT or NB and at the other end there are the fully differentiated, mature NT or ganglioneuromas (GN), passing through transitional states or ganglioneuroblastomas (GNB) (Shimada et al, 1999). Most patients with localized NT can be cured with minimal treatment (Brodeur et al, 1993), whereas, in contrast, children over the age of 1 year with widely disseminated disease usually have a fatal outcome (Brodeur et al, 1993; Coze et al, 1997). The spontaneous differentiation and regression of NB reported in some infants is a salient and a unique feature in human oncology (Brodeur et al, 1993). This differentiation/regression phenomenon is similar to programmed cell death as described in the normal development of the sympathetic nervous system (Kogner, 1995) and has been demonstrated to be a valuable target for therapeutic use (Matthay et al, 1999).

The clinical virulence, differentiation and regression of NT are reflective of the biologic heterogeneity of the tumour. Genetic abnormalities such as MYCN amplification, which are associated with tumour aggressiveness (Bowman et al, 1997; Rubie et al, 1997), inhibit the regression of NB (Weiss et al, 1997). The neurotrophin signals, especially those acting through nerve growth factor (NGF) and its TrkA receptor play an important role in regulating the regression or differentiation of NB (Nakagawara and Brodeur, 1997). NB synthesize and secrete a variety of neuropeptides. The different molecular forms of neuropeptide Y were associated with NB growth (Bjellerup et al, 2000), whereas high expression of pancreastatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide and somatostatin were associated with a differentiated neuronal phenotype and a favourable prognosis (Kogner et al, 1995; Albers et al, 2000). The sst2 somatostatin receptor is considered as a primary target to develop potent neuropeptides analogues for NB therapy (Borgstrom et al, 1999).

Galanin is a 29 or 30 amino acid peptide with wide-ranging effects, especially within the neuroendocrine and the central or peripheral nervous system (Bartfai et al, 1993). Accounting for the different biological effects, three distinct G-protein-coupled galanin receptor subtypes termed Gal-R1, Gal-R2 and Gal-R3 have been cloned in human (Habert-Ortoli et al, 1994; Kolakowski et al, 1998). Experiments in animal models suggest a role for this peptide within the sympathetic nervous system during its development (Garcia-Arraras and Torres-Avillan, 1999). No data regarding the distribution and the role of galanin in the human sympathetic system is available so far. In a preliminary study, a highly variable level of galanin expression has been shown in three NB samples (Tuechler et al, 1998).

Hence, we further investigated the expression and the distribution of galanin and galanin receptors in NT tissue by using morphological approaches and addressed the role of this neuropeptide in NB differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Nineteen patients were investigated. All the 19 children had newly diagnosed and previously untreated NT. The diagnosis of NT was made by histological assessment of a surgically resected tumour specimen. The tumours were classified according to the grading system of Shimada et al (1999); (1) NB, Schwannian stroma-poor (UD: undifferentiated, PD: poorly differentiated, D: differentiating); (2) GNB (nodular or intermixed) and (3) GN, Schwannian stroma-dominant. The MYCN copy number was determined by Southern blot analysis. Patients were staged according to the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) (Brodeur et al, 1993). Patients were treated according to protocols described previously (Coze et al, 1997; Rubie et al, 1997).

In situ hybridization

Preparation of probes

Altogether eight oligonucleotide probes (Eurogentec Bel SA, France) were used in this study for in situ detection of galanin mRNA (n=2), Gal-R1 mRNA (n=2), Gal-R2 mRNA (n=2), Gal-R3 mRNA (n=2). Sequences were complementary to the nucleotides 60–107, 139–186 encoding for human preprogalanin (McKnight et al, 1992), to nucleotides 6–53, 984–1031 of the mRNA encoding the human Gal-R1 (Habert-Ortoli et al, 1994), to nucleotides 91–138, 1001–1048 of the mRNA encoding the human Gal-R2 (Kolakowski et al, 1998) and to nucleotides 41–88, 921–968 of the mRNA encoding the human Gal-R3 (Kolakowski et al, 1998).

All oligonucleotides were chosen in regions presenting few homologies with sequences of related mRNAs, and they were checked against the GenBank database.

For radioactive in situ hybridization, oligonucleotides were labelled as previously described (Dagerlind et al, 1992) at the 3′-end using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) (Amersham, Amersham, UK), in a cobalt-containing buffer with 35S-dATP (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA, USA), to a specific activity of 1–4×109 c.p.m. μg−1 and purified by ethanol precipitation. For non-radioactive in situ hybridization, 100 pmol of each oligonucleotide probe were labelled at the 3′-end with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), according to published protocols (Schmitz et al, 1991).

In situ hybridization procedure

Human NB samples, frozen immediately after sampling, were cut in a cryostat (Microm, Heidelberg, Germany) and then processed as described earlier (Broberger et al, 1997), with 0.5 ng of each of the radioactively labelled galanin or galanin receptor and, when performing double in situ hybridization, 2 nM of the digoxigenin-galanin probes.

All sections were then dipped into Ilford K5 nuclear emulsion (Ilford, Mobberly, Cheshire, UK) diluted 1:1 with distilled water, exposed for three (galanin) and eight (galanin receptor) weeks, developed and fixed. Some sections were counterstained with cresyl violet. After mounting in glycerol, the sections were analyzed in a Zeiss Axiophot 2 microscope equipped with a dark field condenser.

Quantification

The neuronal profiles were delineated on counterstained sections and the number of silver grains per cell were counted automatically on an image analyser (Histo 200, Biocom, Les Ulis, France) as previously described (Le Moine and Bloch, 1995; Landry et al, 2000). To compare the intensity of galanin and galanin receptor mRNA labelling according to differentiation status, grain counting was performed in samples representative of the two ends of the NT spectrum of differentiation, i.e. NB (n=7) and GN (n=4). Three sections were counted in each case. Owing to their nodular or focal heterogeneity, GNB were not taken in account for grain counting. Results were expressed as a number of grains per μm2. Data were presented as mean±standard error; statistical comparisons were made using the Student t-test.

Immunohistochemistry

The NB samples were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 90 mn and rinsed for at least 24 h in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10% sucrose, 0.02% bacitracin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 0.01% sodium azide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The samples were sectioned in a cryostat. The sections were then incubated with antiserum at 4°C for 24 h. Polyclonal galanin antibodies (1 : 1000; Peninsula, Belmont, CA, USA) raised in rabbit were detected with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1 : 200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and streptavidin-fluorescein (1 : 200; Vector). Monoclonal N-Cam antibodies (1 : 1000; Tebu, Le Perray en Yvelines, France) raised in mouse were detected with rhodamine (TRITC)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (1 : 200; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Sections were mounted in an anti-fading solution and examined in a Zeiss Axiophot 2 fluorescence microscope.

Receptor binding

Binding to galanin receptors was investigated using a fluo-ligand conjugate, fluo-Gal™ (Advanced Bioconcept, NEN™ Life Science Products, Zaventtem, Belgium), consisting of a fluorophore (fluorescein) and the 30 residue human galanin. This peptide was designed to bind with high affinity to human Galanin-R subtypes (Mellentin-Michelotti et al, 1999). Cryostat sections were rinsed twice for 5 mn at room temperature in Neurobasal medium (Gibco) containing 0.09% glucose, 0.2% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and 0.02% bacitracin. The sections were preincubated for 10 mn at 4°C, then incubated for 60 mn at 4°C with 20 nM fluo-Gal™ in the same Neurobasal medium solution. The slides were then rinsed and fixed by incubating in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 mn at room temperature. After mounting in para-phenylenediamine (Sigma), the slides were immediately visualised in a Zeiss Axiophot 2 fluorescence microscope.

Controls

The specificity of in situ hybridization results was established for each mRNA species by incubating four control sections with a hybridization cocktail containing an excess (100-fold) of unlabelled probe.

Specificity of the immunostaining patterns was demonstrated by preabsorption of the antiserum with the corresponding peptide (Peninsula).

The specificity of fluorescent binding was assessed, on serial sections, by the ability to compete the binding of fluo-Gal™ using an excess (100-fold) of unlabelled peptide (Peninsula).

As a control, immunohistochemical studies were also performed on three paediatric tumours : Wilms' tumour (n=1), schwannosarcoma (n=1), and schwannoma (n=1).

RESULTS

Characteristics of NT

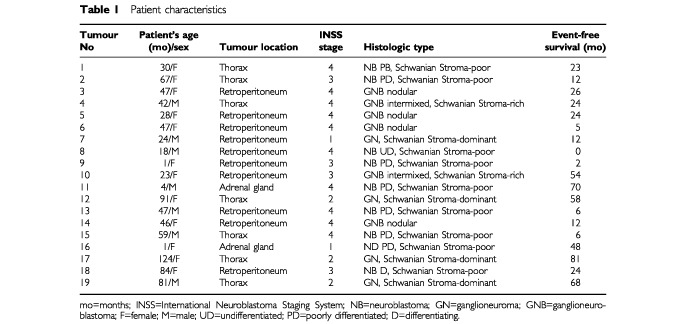

Age of the patient, location of the tumour, staging and histological classification are summarized in Table 1. Out of 19 tumours, nine were NB stroma-poor (one undifferentiated, seven poorly differentiated, one differentiating), six were GNB (two of the intermixed subtype, four of the nodular one), and four were GN (Schwannian stroma-dominant) (Table 1). The median age at diagnosis was 46 (range, 1 to 124) months. The median follow-up period after diagnosis was 24 (range: 2-81) months.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

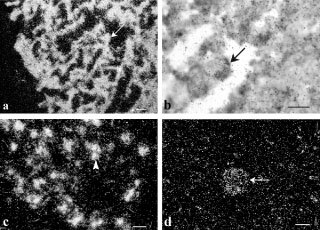

Expression of galanin

Galanin messenger was detected by in situ hybridization in all tumours investigated (Figure 1A,C and D). Cresyl violet counterstaining showed silver grains overlying the cytoplasm of neuronal cell bodies (data not shown). No significant signal was seen over Schwannian stroma cells (Figure 1C,D). Galanin mRNA was found in the vast majority of neuroblasts whatever the differentiation stage. A very high number of positive small round-cells was observed in NB (Figure 1A) whereas only a few labelled large neuronal cells were detected in GN (Figure 1D), in accordance with the decrease in cell density. Galanin mRNA-containing cells were organized in dense clusters in NB (Figure 1A) or in rosette-like structures in tumours with early neuronal differentiation (Figure 1C), and they appeared sparse within the stroma of GN (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Dark-field (A,C and D) emulsion dipped autoradiograms of NT sections after hybridization with 35S-labelled probes complementary to galanin mRNA. The NB contained a high density of strongly labelled small round-cells (arrow) (A). In NB, PD, galanin mRNA-containing cells (arrowhead) were organized in rosette-like structures and no significant signal was seen over Schwannian stroma cells (C). In GN, a few labelled large neuronal cells (arrow) were detected (D). Brightfield micrograph (B) of a section processed for double in situ hybridization visualizing galanin mRNA using non-radioactive probes and Gal-R1 mRNA, using radioactively- labelled probes; co-localization between galanin and gal-R1 mRNA (arrow). Bars indicate 10 μm.

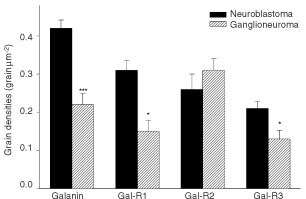

Grain counting showed that the cellular intensity of the labelling was lower in GN than in NB (0.22±0.03 grains μm−2 vs 0.42±0.02 grains μm−2, respectively, P<0.001) (Figure 2). No significant differences were noticed between metastatic and non-metastatic NT, or according to the age of the patient or the MYCN status (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Quantitative evaluation showing the grain densities of labelled neuronal cells after in situ hybridization for galanin mRNA and galanin receptor mRNA in NB and GN. Statistical analyses were carried out by using Student t-test. P value of each counting is indicated. *P<0.05. ***P<0.001.

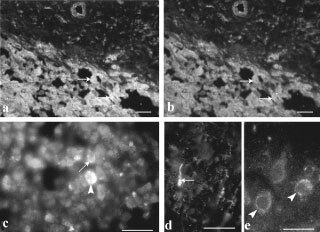

Galanin immunoreactivity (-IR) was seen in all tumours investigated. Sections processed for double immunohistochemistry showed a total overlap of galanin-IR and N-Cam-IR (Figure 3A,B). As in the in situ hybridization study, the number of galanin-IR containing cells decreased with cell density (Figure 3A vs 3E). In GNB, the intensity of the signal was highly variable from one cell to another with intensely labelled neuroblasts coexisting with weakly positive ones within the same section (Figure 3C). Moreover, some fibres were obviously positive in GNB (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence micrographs showing Galanin-IR (A,C–E) and N-Cam-IR (B). Double immunohistochemistry in NB showed a total overlap of galanin-IR and N-Cam-IR (arrows) (A,B). Intensely labelled neuroblasts were seen in GNB, nodular, nodular portion (arrowhead) together with weakly positive ones (arrow) (C) within the same section. Galanin-positive fibres (arrow) were detected in GNB, intermixed (D). The number of galanin-IR containing cells decreased with the neuronal cell density (A vs E). Bars indicate 50 μm.

Expression of galanin receptors

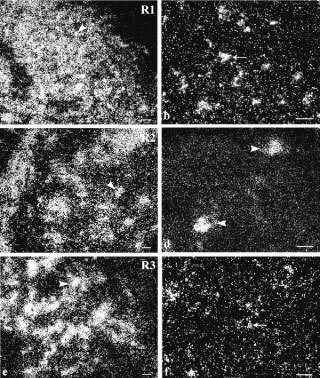

Transcripts coding for all three galanin receptors investigated in this study were found in NT (Figure 4). NB exhibited a homogeneous expression of Gal-R1 (Figure 4A), -R2 (Figure 4C) and -R3 (Figure 4E) mRNAs throughout the whole sample. In GN, galanin receptor messengers were confined to the scattered neuronal cells, not overlying Schwannian stroma cells (Figure 4B,D and F). Furthermore, the cellular intensity of galanin-R1 and -R3 labelling was intense in NB and decreased in GN (Figure 2: R1: 0.31±0.03 grains μm−2 vs 0.15±0.03 grains μm−2 respectively, P<0.05; R3: 0.21±0.02 grains μm−2 vs 0.13±0.02 grains μm−2 respectively, P<0.05). In contrast, galanin-R2 mRNA levels remained unchanged at the cellular level (Figure 2: 0.26±0.04 grains μm−2 vs 0.31±0.03 grains μm2, P: NS). No changes were observed according to the metastatic spread, the MYCN status or the age of the patient.

Figure 4.

Dark-field micrographs of emulsion-dipped autoradiograms of NT tissue after hybridization with 35S-labelled probes complementary to galanin receptor mRNA. The NB contained a high density of strongly labelled small round-cells (arrowheads) (A,C and E). In GN, a weak Gal-R1 and Gal-R3 mRNA labelling was detected in the few large neuronal cells (arrows) (B,F) whereas a strong Gal-R2 labelling was observed in neuronal cells (arrowheads) (D). Bars indicate 10 μm.

A high degree of co-localization between galanin and galanin receptor mRNA was found at the various differentiation stages investigated as revealed by double in situ hybridization (Figure 1B).

Galanin binding

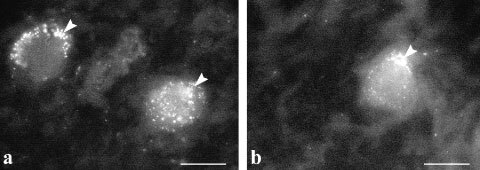

Incubation of sections from GN with fluorescent-galanin resulted in an accumulation of bright spots over the cytoplasm of neuronal cell bodies (Figure 5). They appeared either scattered at the periphery of the perikarya, (Figure 5A,B) or clustered in endosome-like domains (Figure 5B). In a few cases, fluorescent galanin bound to possible neuronal fibres. In contrast, very weak binding, if any, was detected in NB.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence micrographs showing fluorescent-galanin binding to receptors in GN. Accumulation of bright spots over the cytoplasm of neuronal cell bodies were seen at the periphery of the perikarya, possibly on the cell membrane (A,B) or clustered in endosome-like domains located near the membrane (B) (arrowheads). Bar indicates 10 μm.

Controls

No radioactive signal was observed after hybridization with an excess (100-fold) of cold probes. Preabsorption of our antibody with galanin resulted in an absence of labelling. Incubation of fluorescent galanin with an excess (100-fold) of unlabelled peptide totally abolished the signal.

Very weak immunoreactivity, if any, was detected in the three other paediatric tumour samples (Wilms' tumour, schwannosarcoma, and schwannoma). As an internal control, the NT Schwannian stroma cells did not show any galanin-IR, any galanin/Gal-R mRNA labelling or any fluo-Gal™ binding.

DISCUSSION

This study provides clear evidence for galanin and galanin receptor expression and regulation in human NT.

Galanin was previously reported to be expressed in small cell lung cancer (Sethi et al, 1992). Galanin-IR was detected in some adrenal pheochromocytomas but neither in extra-adrenal paragangliomas nor in medullary carcinomas of the thyroid, in endocrine tumours arising in the lung, pancreas, or the gastro-intestinal tract (Sano et al, 1991). Galanin was also shown to be released by tumoral corticotropes but not by other pituitary adenomas and appeared to be involved in tumour growth and to be specifically regulated (Invitti et al, 1999). Galanin was demonstrated to bind to its specific receptors in human pituitary tumours (Hulting et al, 1993). The present findings provided a new example of a neural crest-derived tumour which can be modulated by a strong and regulated expression of galanin/galanin receptors.

In NT, galanin neurone-specific expression was demonstrated by in situ hybridization counterstaining and immunohistochemical co-localization with N-Cam, a neuronal marker. Our data do not suggest any relation with the metastatic potential of NT, or with the MYCN status, perhaps owing to the limited number of patients investigated in our study. On the other hand, the present study demonstrates that galanin/galanin receptor expression is related to the differentiation stage, according to Shimada's classification. During embryogenesis, galanin was widely expressed in differentiating neurones of the peripheral nervous system but dramatically decreased postnatally and was no longer observed in mature principal sympathetic neurones of avian models (Barreto-Estrada et al, 1997; Garcia-Arraras and Torres-Avillan, 1999), as well as in rodent (Xu et al, 1996) and human (Marti et al, 1987; Del Fiacco and Quartu, 1994) primary sensory neurones. Similarly, in NB, most undifferentiated neuronal cells displayed robust galanin expression while its levels were reduced in the well-differentiated GN neuronal cells.

Furthermore, neuronal cultures of galanin knock-out mice demonstrated that galanin and its receptors play a critical developmental role and function together with differentiating factors such as NGF in a molecular cascade to regulate regeneration and neuronal cell survival (Holmes et al, 2000; O'Meara et al, 2000). In the sympathetic ganglion, injury-induced galanin overexpression was triggered by deprivation of NGF (Zigmond and Sun, 1997). Similar mechanisms promoting tumoral cell survival or counteracting neuronal differentiation may be also involved in NB where NGF/TrkA interaction induced differentiation of tumour cells (Eggert et al, 2000).

The role of galanin in tumoral cell proliferation or survival may be exerted in an autocrine/paracrine fashion (Invitti et al, 1999). This hypothesis is further supported in our study by the co-localization between galanin and its receptors. In animal models, direct paracrine effects have already been demonstrated in differentiating and regenerating neurones (Zigmond and Sun, 1997; Holmes et al, 2000), in the pituitary and in various brain nuclei (Todd et al, 1998). In several human cancers, autocrine or paracrine overactivation of neuropeptide G-protein-coupled receptors, including those of galanin, could contribute to neoplasia (Heasley, 2001; Marinissen and Gutkind, 2001). Moreover, some neuropeptide analogues induce apoptosis in cancer cells where neuropeptide autocrine and paracrine systems are involved (Heasley, 2001).

GN show specific features, since they display a relatively high level expression of Gal-R2 and a clear signal for fluo-Gal binding. Hence, galanin effects might be exerted through Gal-R2 in differentiated tumoral cells. In contrast, given their high level of expression, all the three galanin receptors could be considered in NB. However, the lack of binding suggests the absence of available receptors at the cell surface. In a previous study, Tuechler et al (1998) also suggested that galanin binding was inversely related to galanin peptide concentration in NB tissue. The exact significance of this regulation remains to be elucidated.

The different transduction pathways specifically associated with the different galanin receptors may selectively account for distinct biological activities, including cell-survival and neurite-outgrowth, and for neuropeptide-stimulated growth of cancer cells (Heasley, 2001). The biological activities of Gal-R1 and -R3 receptors are mediated by Gi/G0 G-proteins, leading to the inhibition of adenylate cyclase (Kolakowski et al, 1998). In our study, their associated signalling pathways may have played a role in the poorly differentiated NT (or NB). In contrast, Gal-R2 biological activity is exerted through activation of Gq G-protein and phospholipase C and may be involved in processes prominent during nervous system development (Burazin et al, 2000). Gal-R2 expression in GN indicates that its associated signalling pathway might also be involved in NT cell differentiation. Thus, galanin receptors may be a useful therapeutic target in neuroblastoma; in human cancers involving neuropeptide receptors system, novel molecules have been defined to selectively induce/inhibit one of the G-protein signalling (Heasley, 2001).

The present data suggest that galanin and its receptors are involved in abnormal differentiation processes of NT. Further studies are warranted to assign specific roles to the different galanin receptors in the modulation of the tumour phenotype and to identify the clinical implications of the expression of galanin in NT.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants from the Direction de la Recherche Clinique du Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire de Bordeaux, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer.

References

- AlbersARO'DorisioMSBalsterDACapraraMGoshPChenFHoegerCRivierJWengerGDO'DorisioTMQualmanSJ2000Somatostatin receptor gene expression in neuroblastoma Regul Pept 886173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto-EstradaJLMedina-VeraLDe Jesus EscobarJMGarcia-ArrarasJE1997Development of galanin and enkephalin-like reactivities in the sympathoadrenal lineage of the avian embryo. In vivo and in vitro studies Dev Neurosci 19328336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BartfaiTHökfeltTLangelU1993Galanin, a neuroendocrine peptide Crit Rev Neurobiol 7229274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BjellerupPTheodorssonEJornvallHKognerP2000Limited neuropeptide Y precursor processing in unfavourable metastatic neuroblastoma tumours Br J Cancer 83171176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BorgstromPHassanMWassbergERefaiEJonssonCLarssonSAJacobssonHKognerP1999The somatostatin analogue octreotide inhibits neuroblastoma growth in vivo Pediatr Res 46328332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BowmanLCCastleberryRPCantorAJoshiVCohnSLSmithEIYuABrodeurGMHayesFALookAT1997Genetic staging of unresectable or metastatic neuroblastoma in infants: A Pediatric Oncology Group Study J Natl Cancer Inst 89373380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BrobergerCLandryMWongHWalshJHökfeltT1997Subtypes Y1 and Y2 of the neuropeptide Y receptor are respectively expressed in pro-opiomelanocortin and neuropeptide Y-containing neurons of the rat hypothalamic arcuate nucleus Neuroendocrinology 66393408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BrodeurGMPritchardJBertholdFCarlsenNLTCastelVCastleberryRPDe BernardiBEvansAEFavrotMHedborgFKanekoMKemsheadJLampertFLeeREJLookATPearsonADJPhilipTRoaldBSawadaTSeegerRCTsuchidaYVoutePA1993Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment J Clin Oncol 1114661477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BurazinTCLarmJARyanMCGundlachAL2000Galanin-R1 and –R2 receptor mRNA expression during the development of rat brain suggests differential subtype involvement in synaptic transmission and plasticity Eur J Neuroscience 1229012917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CozeCHartmannOMichonJFrappazDDusolFRubieHPlouvierELevergerGBordigoniPBeharCMechinaudFBergeronCPlantazDOttenJZuckerJMPhilipTBernardJL1997NB 87 induction protocol for stage 4 neuroblastoma in children over 1 year of age: a report from the French Society of Pediatric Oncology J Clin Oncol 1534333440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DagerlindÅFribergKBeanAHökfeltT1992Sensitive mRNA detection using unfixed tissue: combined radioactive and non-radioactive in situ hybridization histochemistry Histochemistry 983949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del FiaccoMQuartuM1994Somatostatin, galanin and peptide histidine isoleucine in the newborn and adult human trigeminal ganglion and spinal nucleus: immunohistochemistry, neuronal morphometry and colocalization with substance P J Chem Neuroanat 7171184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EggertAIkegakiNLiuXChouTTLeeVMTrojanowskiJQBrodeurGM2000Molecular dissection of TrkA signal transduction pathways mediating differentiation in human neuroblastoma cells Oncogene 1320432051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-ArrarasJETorres-AvillanI1999Development expression of galanin-like immunoreactivity by members of the avian sympathoadrenal cell lineage Cell Tissue Res 2953341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habert-OrtoliEAmiranoffBLoquetILaburtheMMayauxJF1994Molecular cloning of a functional human galanin receptor Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 9197809783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HeasleyLE2001Autocrine and paracrine signaling through neuropeptide receptors in human cancer Oncogene 2015631569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HolmesFEMahoneySKingVRBaconAKerrNCPachnisVCurtisRPriestleyJVWynickD2000Targeted disruption of the galanin gene reduces the number of sensory neurons and their regenerative capacity Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 971156311568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HultingALLandTBertholdMLangelUHökfeltTBartfaiT1993Galanin receptors from human pituitary tumours assayed with human galanin Brain Res 625173176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- InvittiCGiraldiFPDubiniAMoroniPLosaMPicolettiRCavagniniF1999Galanin is released by adrenocorticotropin-secreting pituitary adenomas in vivo and in vitro J Clin Endocrinol Metab 8413511356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KognerP1995Neuropeptides in neuroblastomas and ganglioneuroblastomas Prog Brain Res 104325338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KolakowskiLO'NeillGHowardABroussardSRSullivanKAFeighnerSDSawdargoMNguyenTKargmanSShiaoLLHreniukDLTanCPEvansJAbramovitzMChateauneufACoulombeNNgGJohnsonMPTharianAKhoshboueiHGeorgeSRSmithRGO'DowdBF1998Molecular characterization and expression of cloned human galanin receptors Gal-R2 and Gal-R3 J Neurochem 7122392251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LandryMHolmbergKZhangXHökfeltT2000Effect of axotomy on expression of NPY, galanin, and NPY Y1 and Y2 receptors in dorsal root ganglia and the superior cervical ganglion studied with double-labeling in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry Exp Neurol 162361384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MoineCBlochB1995D1 and D2 dopamine receptor gene expression in the rat striatum: sensitive cRNA probes demonstrate prominent segregation of D1 and D2 mRNAs in distinct neuronal populations of the dorsal and ventral striatum J Comp Neurol 355418427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MarinissenMJGutkindJS2001G-protein-coupled receptors and signaling networks: emerging paradigms Trends Pharmacol Sci 22368376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MartiEGibsonSJPolakJMFacerPSpringballDRAswegenGVAitchisonMKoltzenburgM1987Ontogeny of peptide- and amine-containing neurons in motor sensory, and autonomic regions of rat and human spinal cord, dorsal root ganglia, and rat skin J Comp Neurol 266332359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MatthayKKVillablancaJGSeegerRCStramDOHarrisRERamsayNKSwiftPShimadaHBlackCTBrodeurGMGerbingRBReynoldsCP1999Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with invasive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation and 13-cisretinoic acid. Children's Cancer group N Engl J Med 34111651173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnightGLKarlsenAEKowalykSMathewesSLSheppardPOO'HaraPJTaborskyGJ1992Sequence of human galanin and its inhibition of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from RIN cells Diabetes 418287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellentin-MichelottiJEvangelistaLTSwartzmanEEMiragliaSJWernerWEYuanPM1999Determination of ligand binding affinities for endogenous seven-transmembrane receptors using fluorometric microvolume assay technology Anal Biochem 27218290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NakagawaraABrodeurGM1997Role of neurotrophins and their receptors in human neuroblastomas: a primary culture study Eur J Cancer 3320502053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'MearaGCoumisUMaSYKehrJMahoneySBaconAAllenSJHolmesFKahlUWangFHKearnsIROve-OgrenSDawbarnDMufsonEJDaviesCDawsonGWynickD2000Galanin regulates the postnatal survival of a subset of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 971156911574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RubieHHartmannOMichonJFrappazDCozeCChastagnerPBaranzelliMCPlantazDAvet-LoiseauHBenardJDelattreOFavrotMPeyrouletMCThyssAPerelYBergeronCCourbon-ColletBVannierJPLemerleJSommeletD1997N-Myc gene amplification is a major prognostic factor in localized neuroblastoma: results of the NB 90 study. Neuroblastoma Study Group of the Societe Française d'Oncologie Pediatrique J Clin Oncol 1511711182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanoTVrontakisMEKovacsKAsaSLFriesenHG1991Galanin immunoreactivity in neuro-endocrine tumors Arch Pathol Lab Med 115926929 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SchmitzGGWalterTSeiblRKesslerC1991Nonradioactive labeling of oligonucleotides in vitro with the hapten digoxigenin by tailing with terminal transferase Ann Biochem 192222231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SethiTLangdonSSmythJRozengurtE1992Growth of small cell lung cancer cells: Stimulation by multiple neuropeptides and inhibition by broad spectrum antagonists in vitro and in vivo Cancer Res 5227372742 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ShimadaHAmbrosIMDehnerLPHataJJoshiVVRoaldB1999Terminology and morphologic criteria of neuroblastic tumors: recommendations by the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee Cancer 86349363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ToddJFSmallCJAkinsanyaKOStanleySASmithDMBloomSR1998Galanin is a paracrine inhibitor of gonadotroph function in the female rat Endocrinology 13942224429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TuechlerCHametnerRJonesNJonesRIismaaTPSperlWKoflerB1998Galanin and galanin receptor expression in neuroblastoma Ann NY Acad Sci 863438441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WeissWAAldapeKMohabatraGFeuersteinBGBishopJM1997Targeted expression of MYCN causes neuroblastoma in transgenic mice EMBO J 1629852995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XuZQShiTJHökfeltT1996Expression of galanin and a galanin receptor in several sensory systems and bone anlage of rat embryos Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 931490114905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZigmondRESunY1997Regulation of neuropeptide expression in sympathetic neurons. Paracrine and retrograde influences Ann N Y Acad Sci 814181197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]