Summary

Nanoscale vectors comprised of cationic polymers that condense DNA to form nanocomplexes are promising options for gene transfer. The rational design of more efficient nonviral gene carriers will be possible only with better mechanistic understanding of the critical rate-limiting steps, such as nanocomplex unpacking to release DNA and degradation by nucleases. We present a two-step quantum dot fluorescence resonance energy transfer (two-step QD-FRET) approach to simultaneously and non-invasively analyze DNA condensation and stability. Plasmid DNA, double-labeled with QD (525 nm emission) and nucleic acid dyes, were complexed with Cy5-labeled cationic gene carriers. The QD donor drives energy transfer stepwise through the intermediate nucleic acid dye to the final acceptor Cy5. At least three distinct states of DNA condensation and integrity were distinguished in single particle manner and within cells by quantitative ratiometric analysis of energy transfer efficiencies. This novel two-step QD-FRET method allows for more detailed assessment of the onset of DNA release and degradation simultaneously.

Keywords: nanocomplex, FRET, quantum dot, delivery, degradation, nonviral

Introduction

Nanoscale vectors in the form of cationic polymers complexed with plasmid DNA (pDNA) have emerged as safer, though less efficient, options for gene transfer compared to viruses [1]. The rational design of more efficient nonviral gene carriers will be possible only with better mechanistic understanding of the critical rate-limiting steps, such as nanocomplex unpacking to release the DNA cargo [2] and subsequent DNA degradation [3, 4]. Condensation of pDNA by cationic polymers protects it from enzymatic degradation, but either pre-mature dissociation or overly stable binding would be detrimental to transfection efficiency [5–7]. Conventional methods to study nanocomplex stability and DNA degradation do not accurately reflect intracellular microenvironments or conditions. For example, gel electrophoresis is a common assay for nanocomplex stability but introduces an external electromotive force. Degradation of DNA has been studied in cells using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) which requires permeabilizing the cell membrane. As an alternative, fluorescence energy transfer (FRET) with organic fluorophores has been used to study the dissociation of pDNA from lipoplexes or polyplexes [8, 9] or the degradation of pDNA [10, 11].

Quantum dots (QDs) have emerged as more efficient FRET donors due to their resistance to photobleaching, broad absorption, and narrow symmetric emission spectra which reduce spectral cross-talk [12–14]. Previously, we demonstrated that single-step quantum dot-mediated FRET (QD-FRET), comprised of a QD donor (605 nm emission) and Cy5 acceptor, is an ultrasensitive method to detect the release of DNA from the nanocomplex [15]. Using this method, we developed a quantitative model and observed that the kinetics and intracellular compartment where dissociation occurs have a significant impact on transfection efficiencies for different gene carriers due to potential enzymatic barriers such as nuclease-mediated DNA degradation [16]. The dependence of nanocomplex stability and its ability to protect DNA on the structure-function relationships of the gene carrier require an integrated sensing platform whereby both DNA release from nanocomplexes and subsequent DNA degradation can be simultaneously monitored.

Here, we demonstrate a novel approach to study both DNA condensation and stability in a simultaneous and non-invasive manner by two-step QD-FRET. The incorporation of QDs as energy transfer donors permits continuous tracking of both rate-limiting processes during gene delivery. Previous applications of stepwise FRET with three fluorophores were to increase the effective distance for energy transfer [17–19] or to study protein interactions only [20]. In our approach, a QD donor (525 nm emission) is paired with a nuclear dye (ND) and a second acceptor Cy5 for stepwise FRET. The relay ND serves a dual purpose: first, as the acceptor/donor (or relay) and second, as an indicator for DNA integrity. At least three states of pDNA can be distinguished through combinations of ND and Cy5 emission and quantitative ratiometric analysis of FRET efficiencies [14, 18]. Two gene carriers, chitosan [21] and polyethylene glycol-polyphosphoramidate block copolymer (PEG-b-PPA) [22], were compared since both polymers elicit transgene expression in vitro and in vivo while forming nanocomplexes with contrasting structures and stabilities. Being amenable to single particle characterization, two-step QD-FRET is particularly valuable for understanding critical barriers to gene transfer given the heterogeneity of nanocomplexes and microenvironments encountered within cells.

Results and Discussion

Versatility of two-step QD-FRET

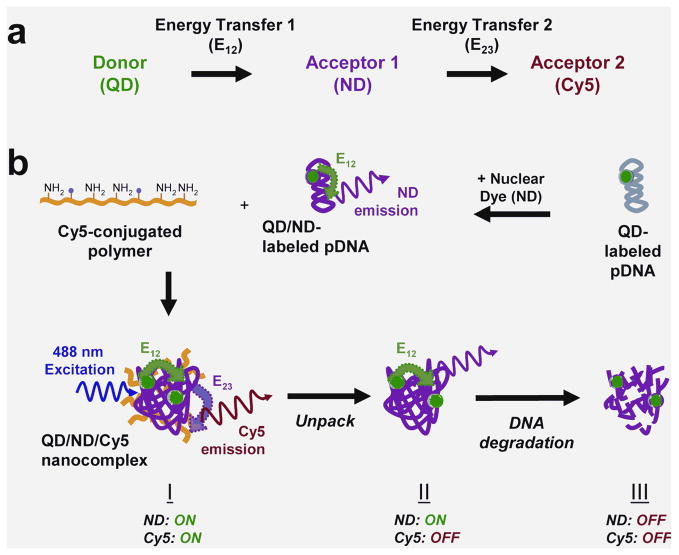

Our three-fluorophore FRET system is designed with a two-step energy transfer [23], henceforth named two-step QD-FRET. The QD donor (525 nm emission) drives energy transfer to an intermediate acceptor ND (energy transfer E12) serving as a relay donor to the final acceptor Cy5 (energy transfer E23) (Figure 1a). Each fluorophore is selected based on their compatibility as single-step FRET pairs, where spectral overlap between the donor and acceptor is maximized and potential cross-talk between channels is minimized. Within this system, three main states of pDNA are indicated by combinations of FRET-mediated emission from the ND and/or Cy5 (Figure 1b). (I) When pDNA, double-labeled with QD and ND (QD/ND-pDNA), are condensed into compact nanocomplexes, the QD donor drives energy transfer through the ND which acts as a relay to Cy5 conjugated on the polymeric gene carrier. For stable nanocomplexes, both the ND and Cy5 are ‘on’ or actively exhibiting intra- (E12) and intermolecular FRET (E23), respectively. (II) When the nanocomplex begins to unpack and release intact pDNA, only the ND is ‘on’ through E12 while Cy5 is ‘off’ due to the loss of E23. (III) The subsequent onset of degradation of free pDNA is indicated by the ND and Cy5 turning ‘off’ due to the loss of E12 and E23, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of two-step QD-FRET. Excitation of the QD donor drives stepwise energy transfer (E12) through the nuclear dye (ND) which serves as the first acceptor/donor (or relay) for energy transfer to the second acceptor Cy5 (E23). (b) Plasmid DNA is double-labeled with QD and nuclear dyes before complexation with a Cy5-labeled cationic polymer to form nanocomplexes by self-assembly. Three distinct states of plasmid DNA (pDNA): (I) condensed within a nanocomplex, (II) released and intact, and (III) degraded, are distinguished by relative ND and Cy5 emission and calculated E12 and E23 efficiencies.

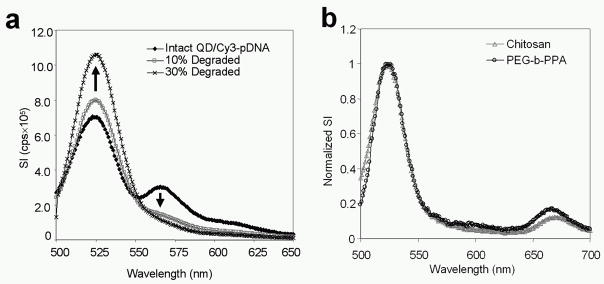

Two cyanine-based NDs having similar spectral properties but different DNA-binding mechanisms were compared to illustrate the versatility of two-step QD-FRET. An intercalating dye (BOBO-3) or covalently binding dye (Cy3) was used to label pDNA as intramolecular FRET acceptors for the QD donor (Supporting Information) [17, 24]. Intact plasmids labeled with QD and Cy3 via a covalent linker (QD/Cy3-pDNA) exhibited two corresponding emission peaks due to E12 (Figure 2a). Similarly, plasmids labeled with both QD and BOBO-3 (QD/BOBO-pDNA) exhibited two peaks corresponding to their emission maxima (Supporting Information, Fig. 1a). Subsequent experiments characterizing DNA degradation were conducted using QD/Cy3-pDNA due to the quenching of QDs caused by unbound BOBO-3 above nM concentrations (Supporting Information, Fig. 2). It is expected that this quenching effect may be mitigated by further optimization of staining ratios such that the concentration of unbound BOBO-3 remains less than nM magnitudes while still allowing for sufficient energy transfer.

Figure 2.

Spectral characterization of two-step QD-FRET. (a) Intact QD/Cy3-pDNA exhibited QD (525 nm) and E12-mediated Cy3 (570 nm) emission (◆). Increasing fractions of degraded QD/Cy3-pDNA: 10% (gray □) and 30% (×). Total pDNA content was kept constant. (b) Emission spectra of nanocomplexes comprised of QD/Cy3-pDNA and Cy5-labeled (670 nm) chitosan (gray △) or PEG-b-PPA (○) showed two-step energy transfer. The signal intensity here was normalized to the QD peak value at 525 nm to compare the energy transfer between the different nanocomplex polymer compositions.

To demonstrate the versatility of this nanophotonics approach, two gene carriers, chitosan [21, 25] and PEG-b-PPA [22], which form contrasting nanocomplex structures were compared. When complexed with DNA, chitosan generates polyplex structures [25] while PEG-b-PPA forms core-shell micelles [22]. The QD/BOBO or QD/Cy3-labeled pDNA were stably complexed with either Cy5-labeled chitosan or PEG-b-PPA. Labeling of the pDNA and polymer had minimal effect on the stability and physical properties of nanocomplexes, compared to unlabeled nanocomplexes (Supporting Information, Fig. 3). The spectra from these triple-labeled nanocomplexes showed that normalized signal intensities of Cy5 for chitosan and PEG-b-PPA were similar (Figure 2b and Supporting Information, Fig. 1b). Hence, two-step QD-FRET is a versatile platform that may be applied to various cationic gene carriers and nanocomplex morphologies.

Quantifying DNA degradation by E12

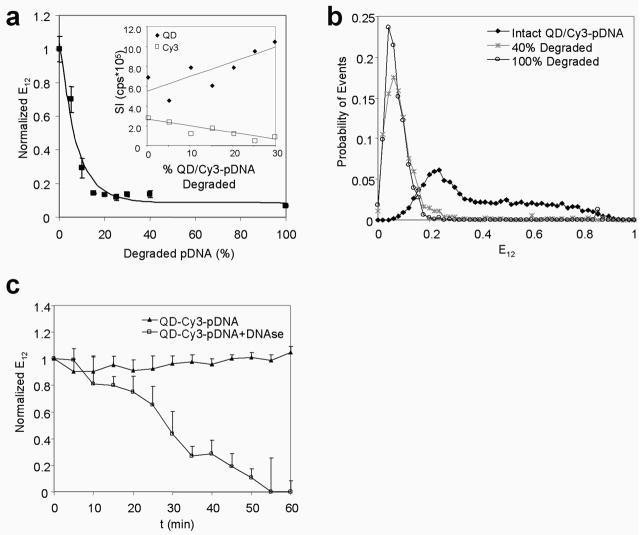

To assess the sensitivity of E12 efficiency to detect DNA degradation, intact QD/Cy3-pDNA were mixed with varying fractions of degraded QD/Cy3-pDNA while keeping the total pDNA amount constant. Increasing fractions of degraded QD/Cy3-pDNA resulted in higher QD signals and reduced FRET-mediated Cy3 signals (Figure 2a). The QD and Cy3 signals varied linearly with increasing fractions of degraded pDNA as expected (Figure 3a, inset). E12 efficiencies were calculated from measured signal intensities according to Equation (1), and an exponential decay function was fitted to experimentally measured E12 efficiencies by least squares (R2=0.96) to generate the E12 calibration curve: y = 0.09 + 0.95e−0.13x, where y is the normalized E12 and x is the % degraded pDNA (Figure 3a). The sensitivity range according to this E12 calibration curve was up to ~30% degraded pDNA, above which the E12 value remained constant at ~0.1. The reduction in E12 efficiency was caused by the diffusion of small DNA oligomers away from the QD donor as plasmid DNA was being cleaved by nucleases and thereby increasing donor-acceptor separation [26] and reducing the acceptor-donor ratio. Similar sensitivity for degradation was reported for siRNA [10] and DNA oligomers [11], illustrating the potential application of QD-FRET to other nucleic acid molecules.

Figure 3.

DNA degradation by QD-FRET. (a) Experimentally measured E12 efficiencies (■, mean±SD, n=3) and the E12 calibration curve: y = 0.09 + 0.95e−0.13x, where y is the normalized E12 and x is the % degraded pDNA. The QD (◆) and Cy3 signals (□) varied linearly with increased fractions of degraded pDNA as expected (inset). The non-linearity of the E12 calibration curve was a result of the ratio used to calculate E12 efficiency. (b) By single molecule detection, the probability histogram for E12 efficiency values for completely intact QD/Cy3-pDNA (◆), a 40% mixture of degraded pDNA (*), and degraded pDNA only (○). (c) The E12 efficiency of QD/Cy3-pDNA normalized to the initial value was monitored for 60 min with nucleases (DNase I) (□) and without nucleases (▲) (mean±SD, n=3).

The mixed population of coiled and relaxed forms of individual plasmids were resolved by the sensitivity of energy transfer and single molecule detection (SMD) (Figure 3b) [14, 27]. While nearly all intact DNA had E12 values above 0.2, the wide distribution of E12 for intact pDNA reflected the mixed presence of coiled plasmids indicated by higher E12 values and relaxed plasmids by lower E12 values. In contrast, the E12 distribution for degraded QD/Cy3-pDNA shifted to the left (E12<0.2) due to the loss of intramolecular FRET and was consistent with the E12 calibration curve in Figure 3a. These observations validate that FRET efficiencies obtained from the emission spectra and single molecule data were in strong agreement and suggest that E12 values are well suited to signal the onset of DNA degradation as a bulk population or as single molecules.

The degradation kinetics of QD/Cy3-pDNA treated with nucleases showed that E12 efficiency declined whereas the E12 of the control QD/Cy3-pDNA (without nucleases) remained constant (Figure 3c). At least 30% of pDNA was degraded after 45 min where E12 efficiencies declined below 0.2. The resistance of the QD donor to photobleaching allowed continuous tracking of the status of QD-labeled pDNA for at least 1 h.

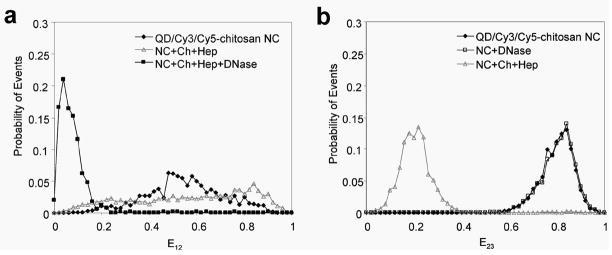

Single molecule and temporal analysis of DNA condensation and degradation

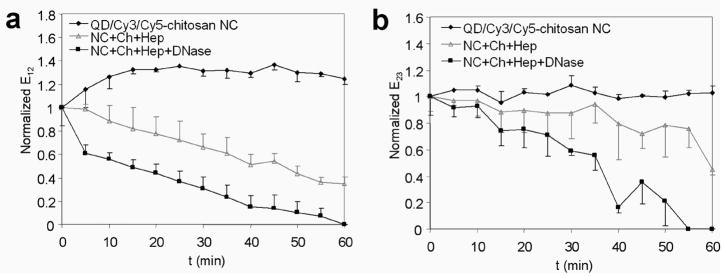

Being amenable to single particle characterization, two-step QD-FRET is particularly valuable for understanding critical barriers to gene transfer given the heterogeneity of nanocomplexes and microenvironments encountered within cells. By three-color SMD (Supporting Information, Fig. 4) [28], the distributions of pDNA having distinct condensed or degraded states were detected. Stable QD/Cy3/Cy5-chitosan nanocomplexes exhibited more efficient intermolecular energy transfer between the DNA and polymer (E23>0.6) (Figure 4b). Nanocomplexes treated with DNase I had nearly identical E23 efficiency distributions as control nanocomplexes, suggesting that the gene carrier provided effective protection from enzymatic degradation. Further, E23 efficiencies above 0.6 indicated that chitosan remained stably complexed to pDNA after nuclease treatment. When treated with chitosanase and heparin for 1 h to disrupt the nanocomplexes, the E23 efficiency distribution shifted down to below 0.4, which was consistent with measured unpacking kinetics and bulk spectral measurements (Supporting Information, Fig. 5). The gradual decrease in E23 of disrupted nanocomplexes was caused by the initial swelling or loosening of the nanocomplex which was followed by a more rapid decline after 30 min as it continued to unpack (Figure 5b). The addition of nucleases along with chitosanase and heparin steepened the rate of E23 reduction, indicating a faster unpacking of the nanocomplex. As the nanocomplexes were being disrupted, the added nucleases expedited the dissociation process since DNA was also susceptible to cleavage. Similarly to E12 efficiency, the E23 efficiency is sensitive to the separation between Cy3 and Cy5 during the unpacking process where the nanocomplex loosens as the pDNA and gene carrier continue to dissociate.

Figure 4.

Characterization of two-step QD-FRET nanocomplexes by single molecule detection. The probability histograms of (a) E12 efficiencies and (b) E23 efficiencies for QD/Cy3/Cy5-chitosan nanocomplexes which were untreated (◆), treated with DNase I (□), disrupted with heparin (Hep) and chitosanase (Ch) (gray △), or disrupted in combination with DNase I (■).

Figure 5.

Temporal characterization of two-step QD-FRET nanocomplexes. (a) Changes in E12 efficiencies for DNA degradation and (b) E23 efficiencies for dissociation of QD/Cy3/Cy5-chitosan nanocomplexes (NC) were monitored for 60 min. Nanocomplexes were untreated (◆) or disrupted by treatment with heparin (Hep) and chitosanase (Ch) (gray △), or disrupted in combination with DNase I (■). Efficiencies were normalized to the initial value before treatment (mean±SD, n=3).

The integrity of encapsulated and released pDNA was maintained as indicated by their E12 efficiencies being above 0.2 (Figure 4a). When encapsulated within a nanocomplex, condensed pDNA showed a more uniform distribution of E12 compared to that for free pDNA (Figure 3b). Likewise, plasmids released from disrupted nanocomplexes also exhibited a wider E12 distribution, which was attributed to their relaxation after release. Combining disruption with nucleases resulted in the degradation of released pDNA, which was indicated by the clear shift in E12 efficiency distributions to below 0.2 (Figure 4a) and the rapid decline of E12 efficiency during the first 5 min followed by a steady decline to less than 0.2 after 40 min as more DNA was degraded (Figure 5a). Taken together, these results confirmed that condensed DNA was protected by the gene carrier from nuclease-mediated degradation through steric hindrance [25], and more importantly, provided direct evidence that unpacking occurs prior to DNA cleavage by nucleases.

Analyzing intracellular unpacking and DNA degradation

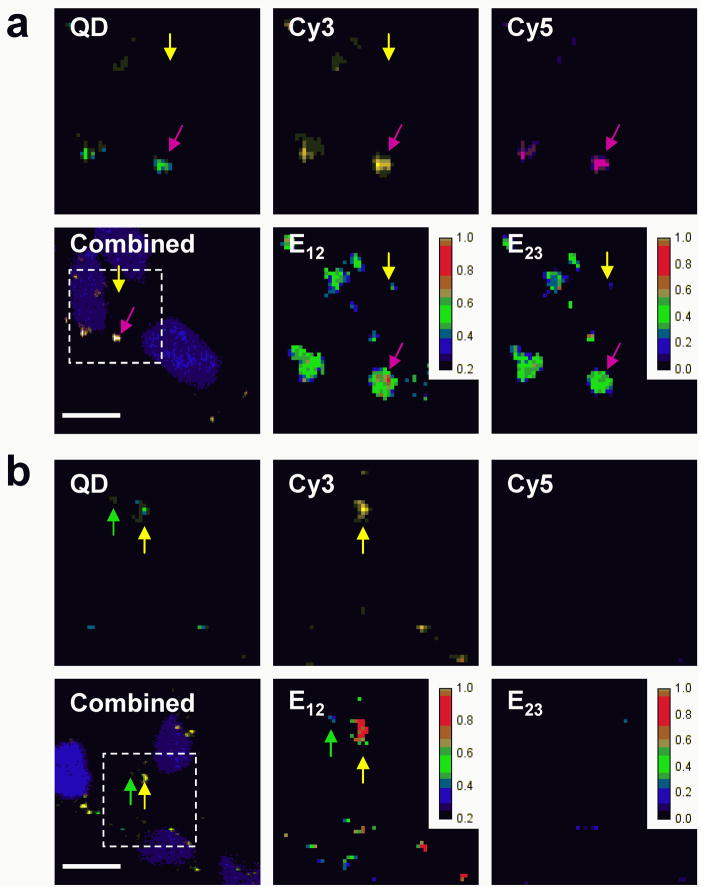

Combining quantitative ratiometric FRET analysis with SMD may resolve subpopulations of nanocomplexes and DNA having E23 and E12 values that signify intermediate stages of unpacking and degradation, respectively. These intermediate stages can be correlated to energy transfer efficiencies calculated from images of transfected cells, giving a more accurate description of unpacking and DNA degradation kinetics within cells. HEK293 cells were transfected with triple-labeled chitosan and PEG-b-PPA nanocomplexes to study the intracellular release and degradation of pDNA by two-step QD-FRET. At least three distinct states of pDNA were observed by calculating E12 and E23 efficiencies on a pixel-by-pixel basis using Equations (1) and (2), respectively (Supporting Information). At 4 h post-transfection, chitosan nanocomplexes remained stable or began dissociating since E23 efficiencies were below 0.6 (Figure 6a). As a result, most of the pDNA associated with chitosan maintained its integrity since their E12 efficiencies were above 0.5 in value. In contrast, nearly all the pDNA were dissociated from PEG-b-PPA micelles as indicated by E23 efficiencies below 0.4 (Figure 6b). The free pDNA showed a range of E12 efficiencies but some pDNA clearly have E12 efficiencies less than 0.2, indicating that these plasmids were degraded as a consequence of being rapidly released. Microinjected pDNA were reported to be degraded within 2 h [3, 4, 29]. The unpacking kinetics observed was consistent for chitosan [16] and PEG-b-PPA, which formed relatively less stable complexes (unpublished data). The PEG conjugation may increase the colloidal stability of PEG-b-PPA micelles but reduce the complex stability of the micelles [11]. These results underscore the delicate balance between maintaining stability to preserve DNA and allowing for its release to increase bioavailability.

Figure 6.

Intracellular analysis by two-step QD-FRET. HEK293 cells were transfected with (a) QD/Cy3/Cy5-chitosan and (b) QD/Cy3/Cy5-PEG-b-PPA nanocomplexes. The combined image of QD, Cy3, and Cy5 channels at 4 h post-transfection shows colocalized signals relative to the nucleus (blue). Individual QD (green), Cy3 (yellow), Cy5 (purple) channels, E12 efficiencies, and E23 efficiencies are shown for the region of interest (dashed box). Energy transfer efficiencies for DNA degradation (E12) and unpacking (E23) were calculated on a pixel-by-pixel basis and their values are indicated by the pseudo-color scale. Examples of condensed pDNA within nanocomplexes (purple arrow), released intact pDNA (yellow arrow), and degraded pDNA (green arrow) are shown. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Discussion

We have demonstrated a two-step QD-FRET approach to simultaneously and non-invasively monitor DNA condensation and integrity. The use of QDs as the donor allowed efficient stepwise energy transfer to a relay ND and acceptor Cy5. At least three distinct states of pDNA were distinguished by FRET-mediated emission from the ND and/or Cy5 and by quantitative ratiometric analysis of E12 or E23 efficiencies. After considering applicable quantification methods [30–32], the ratiometric analysis presented here was chosen to be the most meaningful method to compare data across different detection platforms used in this study: spectrofluorometry, 3-channel SMD, fluorescence microplate reader, and confocal microscopy. We obtained similar results across these platforms, suggesting that the ratiometric analysis was an appropriate metric in the single [14] and two-step QD-FRET systems to monitor DNA integrity and condensation.

Condensed, free and intact, or partially degraded pDNA were identified in a cellular and intracellular conditions. Given the Forster distances for the QD/Cy3 pair and Cy3/Cy5 pair were 5.8 nm [24] and 6.0 nm [28], respectively, the high sensitivity of energy transfer to changes in donor-acceptor distance and ratios allowed various stages of unpacking and degradation to be detected. The E12 efficiency is sensitive to the diffusion of small oligomers away as DNA was being cleaved which reduced the acceptor-donor ratio. Similarly, E23 is sensitive to the separation between the pDNA and gene carriers as they dissociate. There is also a possibility that the QD and Cy5 may participate in energy transfer[23], but any such energy transfer is expected to be minimal due to the small spectral overlap. Any effect of QD-Cy5 energy transfer (E13) is expected to be negligible in our analysis since E13 would contribute only in the case of compact nanocomplexes. Further, the narrow emission spectra of QDs allowed efficient energy transfer mainly through the intermediate ND to the final acceptor Cy5. Intercalated or covalently-bound nuclear dyes were both compatible relays within this versatile two-step QD-FRET system. Unlike previous reports which have used relay fluorophores solely to increase the effective distance range for QD-FRET [17], the Cy3 in this system serves as both a relay fluorophore as well as an indicator of DNA integrity by intramolecular FRET.

This versatility was again demonstrated by applying two-step QD-FRET to analyze different polymers. Chitosan and PEG-b-PPA formed nanocomplexes with contrasting structures and unpacking rates which are factors that play a role in determining eventual transfection efficiency. Considering that the mean luciferase expression levels were at least 10× lower for chitosan than PEG-b-PPA in hepatocytes at 6 h post-transfection (0.02 and 0.36 ng luciferase/mg protein, respectively) and 48 h post-transfection [22, 33], the intracellular analysis of E12 and E23 suggested that the slower unpacking of chitosan nanocomplexes may have preserved DNA integrity but ultimately hampered its ability to release DNA, reducing its intracellular bioavailability. In contrast, PEG-b-PPA micelles dissociated readily in cells, rendering DNA accessible for transcription but also susceptible to degradation which had less of an impact on transfection efficiency in this case. From this comparison, two-step QD-FRET resolved mechanistic differences in the cellular processing of different gene carriers and identified the relative importance of unpacking and protection specific to individual carriers and their effect on short- and long-term transgene expression.

In conclusion, two-step QD-FRET is a sensitive and versatile platform to study rate-limiting barriers to efficient gene transfer. To our knowledge, this is the first report where DNA dissociation from nanocomplexes and subsequent DNA degradation may be tracked in a simultaneous and non-invasive manner. This is also the first attempt in using stepwise QD-FRET as a sensing system to identify various states of DNA. Quantitative ratiometric analysis of energy transfer efficiencies were correlated to at least three distinct states of DNA condensation and integrity. Condensed, free and intact, or partially degraded pDNA were identified in a single particle manner and within cells. Different nuclear dyes and gene carriers were compared to demonstrate the potential applicability of this method to other types of vectors. Thus, two-step QD-FRET is poised to expedite the design of more efficient vectors for nanomedicine by offering a more accurate mechanistic understanding of critical barriers to gene delivery.

Experimental Section

Labeling of plasmid DNA and polymeric gene carriers

Plasmid DNA (pEGFP-C1, 4.9 kb, Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was labeled with nuclear dyes and streptavidin-functionalized QD525 (Qdot 525 ITK, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described previously [15]. Briefly, pDNA were biotinylated as described by the manufacturer (Label IT Biotin, Mirus Bio, Madison, WI) but scaled to have ~1–2 biotin labels per pDNA. The number of QDs labeled onto each pDNA is estimated to be ~1–3 [15]. Prior to QD-labeling, biotinylated plasmid was labeled with either one of two cyanine-based nuclear dyes which have different DNA-binding mechanisms but similar spectral characteristics for comparison. An intercalating dye, BOBO-3, (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and a covalently binding dye, Cy3 (Label IT Cy3, Mirus Bio, Madison, WI), were selected based on their excitation and emission spectra to allow for efficient energy transfer [17, 24]. The primary amines of the cationic polymeric gene carriers were labeled with N-hydroxy-succinimide-functionalized Cy5 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) through carbodiimide chemistry. A solution of Cy5 dye was gradually added to aqueous solutions of chitosan (390 kDa, 83.5% deacetylated, Vanson, Redmond, WA) or PEG-b-PPA (synthesized as described in [22]) and stirred continuously for at least 12 h. For chitosan, the reaction mixture was maintained at pH ~6.5 to keep chitosan soluble. Any remaining free dye was removed by dialysis to obtain only Cy5-labeled polymer. See Supporting Information for full details on labeling.

Synthesis of two-step QD-FRET nanocomplexes

The QD/BOBO-pDNA or QD/Cy3-pDNA was electrostatically complexed with a Cy5-labeled chitosan or PEG-b-PPA to form triple-labeled nanocomplexes (QD/ND-pDNA/Cy5-polymer). Nanocomplexes were prepared from chitosan as described previously [15]. Briefly, Cy5-chitosan (pH 5.5–5.7; 0.1% in 25 mM acetic acid solution) and QD-labeled pDNA in 50 mM of sodium sulfate solution were both heated to 55°C separately. Equal volumes of both solutions were quickly mixed under high vortexing. Chitosan nanocomplexes were formed at an N/P ratio (primary amine to phosphate ratio) of 4:1. The synthesis of nanocomplexes formed with PEG-b-PPA are described elsewhere [22]. Briefly, pDNA was added to an aqueous solution of PEG-b-PPA.

Complexes were formed at an N/P ratio of 8:1 by adding equal volumes of polymer solution to the DNA solution and then vigorously mixed. All polyplexes were then used without further purification. Fluorescence emission spectra of QD/ND/Cy5-nanocomplexes were scanned by a spectrofluorometer (Spex FluoroLog-3, Horiba Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ). The excitation wavelengths for QD/BOBO-3 and QD/Cy3-labeled nanocomplexes were 425 nm and 405 nm, respectively. See Supporting Information for full details on characterizing polyplex size and zeta potential.

Ratiometric analysis of FRET efficiencies

A ratiometric method [14, 18] was used to calculate efficiencies for energy transfers between the QD and ND (E12) and between the ND and Cy5 (E23), separately, according to following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where IQD525, IND, and ICy5 represent the burst or signal intensities obtained from each corresponding channel and ND is either BOBO-3 or Cy3.

Disruption of nanocomplexes and degradation of DNA

QD/Cy3-pDNA was degraded with DNase I (2 U/μg pDNA; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 1 h at 37°C. To inhibit DNase I, 10% by volume of 400 mM TAE buffer supplemented with 10 mM EDTA was added. While keeping the total DNA amount constant per sample, mixtures of degraded and intact QD/Cy3-pDNA were prepared and its emission spectra scanned with an excitation at 405 nm. The calibration curve relating E12 efficiency according to equation (1) to the fraction of degraded pDNA was determined by least squares fitting of an exponential function to the experimental E12 data normalized to E12 value of intact QD/Cy3-pDNA (Origin v6.0, OriginLab, Northampton, MA). The kinetics of QD/Cy3/Cy5-chitosan nanocomplex dissociation and DNA degradation were monitored for 1 h at 37°C. Triplicate wells containing QD/Cy3/Cy5-chitosan nanocomplexes were treated with heparin sulfate (8 μg/μg pDNA; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and chitosanase (14 μg enzyme/μg polymer; Seikagaku America, Ijamsville, MD) and/or DNase I (2 U/μg pDNA). FRET efficiencies E12 and E23 were calculated according to Equations (1) and (2), respectively, and normalized to the initial value. See Supporting Information for full details on data acquisition.

3-channel single molecule detection

The custom setup used for single molecule detection is similar to the one reported previously [15]. Energy transfer efficiencies were analyzed and distributions of E12 and E23 were obtained for each 100-s measurement. The probability histogram, based on the distributions of E12 and E23, was then normalized according to the number of total events to keep the sum of probabilities (area under the curve) for each histogram equal to unity and plotted from the average of three independent measurements. See Supporting Information for full details on data acquisition.

Confocal imaging

HEK293 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were transfected with QD-FRET polyplexes containing 0.5 μg DNA in 0.5 ml of reduced-serum media (Opti-MEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 4 h at 37°C. At 4 h post-transfection, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with a nuclear dye (Hoechst 33342, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA). Imaging was performed with a confocal microscope (LSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using the multi-track mode. Corresponding pixels of 12-bit images from each individual QD525, Cy3, or Cy5 channel were used to calculate FRET efficiencies according to equations (1) and (2) and presented as a pseudo-color image and scale. The background values for E12 were found to be <0.1 and E23 to be negligible. See Supporting Information for full details on image acquisition and assessing transfection efficiency.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH EB002849, NSF DBI-0552063, CBET0546012, and NIH DK068399.

Biographies

Dr. Hunter H. Chen is currently working in formulation development for a biotechnology company. He received his Ph.D. and M.S.E. degrees in Biomedical Engineering from Johns Hopkins University where his doctoral dissertation, under the mentorship of Dr. Kam W. Leong, was focused on developing and applying nanophotonic methods to monitor the intracellular trafficking and unpacking of DNA nanocomplexes. His Master’s thesis work involved optical and MR image guided gene and drug delivery. He received his B.S. in Bioengineering from the University of California at Berkeley.

Dr. Hunter H. Chen is currently working in formulation development for a biotechnology company. He received his Ph.D. and M.S.E. degrees in Biomedical Engineering from Johns Hopkins University where his doctoral dissertation, under the mentorship of Dr. Kam W. Leong, was focused on developing and applying nanophotonic methods to monitor the intracellular trafficking and unpacking of DNA nanocomplexes. His Master’s thesis work involved optical and MR image guided gene and drug delivery. He received his B.S. in Bioengineering from the University of California at Berkeley.

Dr. Yi-Ping Ho received her B.S. and M.S. in Power Mechanical Engineering from National Tsing-Hua University, Taiwan and Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from Johns Hopkins University, respectively. She is currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Duke University in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. Her research focuses on integrating nanophotonics, novel molecular constructs and microfluidics for detecting nucleic acids in the context of disease diagnostics and gene therapy.

Dr. Yi-Ping Ho received her B.S. and M.S. in Power Mechanical Engineering from National Tsing-Hua University, Taiwan and Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from Johns Hopkins University, respectively. She is currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Duke University in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. Her research focuses on integrating nanophotonics, novel molecular constructs and microfluidics for detecting nucleic acids in the context of disease diagnostics and gene therapy.

Mr. Xuan Jiang was born in Luoyang, China in 1979. He received his B.S. degree in polymer science and engineering from Fudan University in 2001 and M.S. degree in Chemistry from National University of Singapore in 2004. Currently, he is a 4th-year PhD student in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. His research focuses on the development of polymeric micelle systems for liver-targeted gene delivery. He has co-authored 9 peer reviewed journal publications.

Mr. Xuan Jiang was born in Luoyang, China in 1979. He received his B.S. degree in polymer science and engineering from Fudan University in 2001 and M.S. degree in Chemistry from National University of Singapore in 2004. Currently, he is a 4th-year PhD student in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. His research focuses on the development of polymeric micelle systems for liver-targeted gene delivery. He has co-authored 9 peer reviewed journal publications.

Dr. Hai-Quan Mao received his B.S. and Ph.D. in polymer chemistry from Wuhan University in 1988 and 1993, respectively. He completed his postdoctoral research in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Johns Hopkins University from 1995 to 1998, and moved to Johns Hopkins in Singapore as a research investigator. He also taught at the Department of Materials Science in the National University of Singapore as an adjunct assistant professor from 2001 to 2003. Since 2003, he has been an assistant professor in Materials Science and Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Mao received the Capsugel Award for Outstanding Research from the Controlled Release Society in 1998, and the Faculty Early Career Award from the National Science Foundation in 2008. He has co-authored 66 peer reviewed journal publications and 16 US patents. His current research focuses on engineering polymeric nanomaterials for gene delivery and for regenerative medicine applications.

Dr. Hai-Quan Mao received his B.S. and Ph.D. in polymer chemistry from Wuhan University in 1988 and 1993, respectively. He completed his postdoctoral research in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Johns Hopkins University from 1995 to 1998, and moved to Johns Hopkins in Singapore as a research investigator. He also taught at the Department of Materials Science in the National University of Singapore as an adjunct assistant professor from 2001 to 2003. Since 2003, he has been an assistant professor in Materials Science and Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Mao received the Capsugel Award for Outstanding Research from the Controlled Release Society in 1998, and the Faculty Early Career Award from the National Science Foundation in 2008. He has co-authored 66 peer reviewed journal publications and 16 US patents. His current research focuses on engineering polymeric nanomaterials for gene delivery and for regenerative medicine applications.

Prof. Wang received his B.S. and M.S. in Mechanical Engineering from National Taiwan University in 1988 and 1994. He served in the R.O.C. military service from 1994 to 1996 and then worked in Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) from 1996 to 1998. He received his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from University of California, Los Angeles in 2002. After graduation, Dr. Wang joined The Johns Hopkins University as a faculty member in the departments Mechanical Engineering and Biomedical Engineering. His research areas includes single molecule detection, nano-biomolecular sensors and microfluidics and the their applications to molecular diagnostics. Prof. Wang received the NSF CAREER award in 2006.

Prof. Wang received his B.S. and M.S. in Mechanical Engineering from National Taiwan University in 1988 and 1994. He served in the R.O.C. military service from 1994 to 1996 and then worked in Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) from 1996 to 1998. He received his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from University of California, Los Angeles in 2002. After graduation, Dr. Wang joined The Johns Hopkins University as a faculty member in the departments Mechanical Engineering and Biomedical Engineering. His research areas includes single molecule detection, nano-biomolecular sensors and microfluidics and the their applications to molecular diagnostics. Prof. Wang received the NSF CAREER award in 2006.

Dr. Kam Leong is the James B. Duke Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Duke University. He received his PhD in Chemical Engineering from the University of Pennsylvania and a postdoctoral training in Applied Biological Sciences at MIT. After serving as a faculty in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine for 20 years, he moved to Duke University in 2006 to lead a research initiative on applying nanotechnology to drug, gene, immuno-, and cell therapy. In addition to being a research faculty at the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore, he also holds a Distinguished Visiting Professorship at the National University of Singapore. He serves on the editorial boards of eight journals, owns more than 35 issued patents, and has published ~200 peer-reviewed research manuscripts. The major research areas of his laboratory involve applying nanoparticles for gene delivery and understanding the response of stem cells to nanotopographical cues for stem cell tissue engineering.

Dr. Kam Leong is the James B. Duke Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Duke University. He received his PhD in Chemical Engineering from the University of Pennsylvania and a postdoctoral training in Applied Biological Sciences at MIT. After serving as a faculty in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine for 20 years, he moved to Duke University in 2006 to lead a research initiative on applying nanotechnology to drug, gene, immuno-, and cell therapy. In addition to being a research faculty at the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore, he also holds a Distinguished Visiting Professorship at the National University of Singapore. He serves on the editorial boards of eight journals, owns more than 35 issued patents, and has published ~200 peer-reviewed research manuscripts. The major research areas of his laboratory involve applying nanoparticles for gene delivery and understanding the response of stem cells to nanotopographical cues for stem cell tissue engineering.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supplementary methods and figures; QD/BOBO/Cy5 spectra; Concentration dependent quenching of QD by free BOBO; DNA retention of QD/BOBO/Cy5-chitosan nanocomplexes; Schematic of three-color single molecule detection setup; Spectra of intact and disrupted QD/Cy3/Cy5-chitosan nanocomplexes.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Putnam D. Nat Mater. 2006;5:439. doi: 10.1038/nmat1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaffer DV, Fidelman NA, Dan N, Lauffenburger DA. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;67:598. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(20000305)67:5<598::aid-bit10>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechardeur D, Sohn KJ, Haardt M, Joshi PB, Monck M, Graham RW, Beatty B, Squire J, O’Brodovich H, Lukacs GL. Gene Ther. 1999;6:482. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollard H, Toumaniantz G, Amos JL, Avet-Loiseau H, Guihard G, Behr JP, Escande D. J Gene Med. 2001;3:153. doi: 10.1002/jgm.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiang T, Wen J, Lim HW, Leong KW. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5293. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koping-Hoggard M, Varum KM, Issa M, Danielsen S, Christensen BE, Stokke BT, Artursson P. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao HQ, Leong KW. Adv Genet. 2005;53:275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itaka K, Harada A, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H, Kataoka K. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:841. doi: 10.1021/bm025527d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong HJ, Liu J, Riddle K, Matsumoto T, Leach K, Mooney DJ. Nat Mater. 2005;4:460. doi: 10.1038/nmat1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raemdonck K, Remaut K, Lucas B, Sanders NN, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10614. doi: 10.1021/bi060351b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Remaut K, Lucas B, Raemdonck K, Braeckmans K, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1333. doi: 10.1021/bm0611578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clapp AR, Medintz IL, Mauro JM, Fisher BR, Bawendi MG, Mattoussi H. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:301. doi: 10.1021/ja037088b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Nat Mater. 2005;4:435. doi: 10.1038/nmat1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang CY, Yeh HC, Kuroki MT, Wang TH. Nat Mater. 2005;4:826. doi: 10.1038/nmat1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho YP, Chen HH, Leong KW, Wang TH. J Control Release. 2006;116:83. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen HH, Ho YP, Jiang X, Mao HQ, Wang TH, Leong KW. Mol Ther. 2008;16:324. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medintz IL, Clapp AR, Mattoussi H, Goldman ER, Fisher B, Mauro JM. Nat Mater. 2003;2:630. doi: 10.1038/nmat961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haustein E, Jahnz M, Schwille P. Chemphyschem. 2003;4:745. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200200634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S, Gaylord BS, Bazan GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5446. doi: 10.1021/ja035550m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galperin E, Verkhusha VV, Sorkin A. Nat Methods. 2004;1:209. doi: 10.1038/nmeth720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy K, Mao HQ, Huang SK, Leong KW. Nat Med. 1999;5:387. doi: 10.1038/7385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang X, Dai H, Ke CY, Mo X, Torbenson MS, Li Z, Mao HQ. J Control Release. 2007;122:297. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watrob HM, Pan CP, Barkley MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7336. doi: 10.1021/ja034564p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim TC, Bailey VJ, Ho YP, Wang TH. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:075701. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/7/075701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao HQ, Roy K, Troung-Le VL, Janes KA, Lin KY, Wang Y, August JT, Leong KW. J Control Release. 2001;70:399. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remaut K, Lucas B, Braeckmans K, Sanders NN, De Smedt SC, Demeester J. J Control Release. 2005;103:259. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang TH, Peng Y, Zhang C, Wong PK, Ho CM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5354. doi: 10.1021/ja042642i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohng S, Joo C, Ha T. Biophys J. 2004;87:1328. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.043935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu N, Kamezaki F, Shigematsu S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clamme JP, Deniz AA. Chemphyschem. 2005;6 doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galperin E, Verkhusha V, Sorkin A. Nature Methods. 2004;1 doi: 10.1038/nmeth720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jares-Erijman EA, Jovin TM. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1387. doi: 10.1038/nbt896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai H, Jiang X, Tan GC, Chen Y, Torbenson M, Leong KW, Mao HQ. Int J Nanomedicine. 2006;1:507. doi: 10.2147/nano.2006.1.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.