Abstract

A very sizable proportion of juvenile delinquents and adult criminals come from backgrounds and family kin systems having deviant parents or kin. This paper provides a focus upon the child-rearing practices directly observed by trained ethnographer during a case study of one highly criminal, drug-using household/kin network. The concrete expectations (and actual practices)—called conduct norms—with which the household adults respond to (or “nurture”) children and juveniles are delineated. While children are taught to “pay attention” to what adults do, adults typically model various deviant activities and rarely engage in conventional behaviors. Drug-using, and especially crack-using, men and women are expected not to raise (or financially support) children born to them; other kin expect to raise children of such unions. Children are not expected, nor able, to develop strong affective bonds with any household adults, and receive little or no psychological parenting. Adults do not take strong measures to protect children/juveniles from harm, and often adults are a major source of harm. In many ways the conduct norms in such crack-using households are well designed to “nurture” those persons who will be antisocial as children, delinquents as juveniles, and become criminals, drug misusers, and prostitutes in adulthood—and who have very few chances to become conventional adults. [Translations are provided in the International Abstracts Section of this issue.]

Keywords: Developing careers in drug use and crime, Socialization into drug use and crime, Conduct norms in crack-using households

Introduction

It is a criminological truism that a large proportion of persons entering juvenile detention centers, jails, prisons, and drug-user treatment programs have been raised in households or family systems characterized by a history of alcohol and other drug use, criminality, and violence (see Loeber and Southamer-Loeber, 1986, for a review). Numerous studies provide evidence of intergenerational continuity in both substance use (Smart and Fejer, 1972; Sowder and Burt, 1980; Deren, 1986; Johnson and Pandina, 1991; Green et al., 1991) and criminality (West and Farrington, 1973, 1977; McCord, 1979; Robins et al., 1975; Robins, 1979; Farrington 1992). Family factors such as poor parental child-rearing practices, parents' rejection of the child, poor supervision or monitoring, erratic or harsh discipline, parental conflict, and low parental interest in education have been identified as predictors of both self-reported and officially recorded delinquency (West and Farrington, 1973; Farrington, 1986, 1992; Loeber and Dishion, 1983; Loever and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986). Rarely delineated or understood, however, are the normative systems and social processes (occurring at the level of the household, family, and community) of child rearing and supervision which create young adults without conventional skills and education who are at high risk for crime and delinquency, drug use, and violence.

While some studies (Panel on High Risk Youth, 1993; Wilson, 1987; Jancks and Peterson, 1991) have sought to document the structural or macrolevel forces influencing these outcomes, little is known about the impact of microlevel processes (at the level of the family or household). Macrolevel forces, such as the decline in manufacturing and low wage jobs, reduced public housing, increased housing costs, declines in purchasing power for welfare recipients and low income workers, devaluation of high school education, and the widespread proliferation of drug use and sales, criminality, and incarceration in many low income urban communities, have all been identified as factors conducive to inadequate caregiving and socialization (Dunlap and Johnson, 1992)—but do not by themselves create such outcomes. As Currie has noted, “Families that are burdened by the stresses of poor income, lack of responsive social networks, internal conflict and parental violence are, not too surprisingly, less able to ensure the kind of supervision and guidance that, in families with better resources, reduce the risks of youth criminality and violence” (1985:56).

This paper analyzes the microlevel social processes whereby families and households exposed to many of the above social forces and deprivations engage in patterned practices which effectively rear children and juveniles for careers as deviant adults in severely distressed inner-city households (Dunlap and Johnson, 1992; Kasarda, 1992). The paper delineates specific conduct norms identified during an intensive ethnography of a multiproblem inner-city kin network which has produced highly deviant adults across three generations. It focuses on a particular household—the Smith family—where almost all adults became drug users, criminals, or violent persons, and failed to achieve conventional education, skills, or legal employment. The major theme of this paper concerns the development and maintenance of special conduct norms (defined shortly) in drug-using households which generate child-rearing and household management practices that routinely produced young adults ill-suited to succeed in conventional society and predisposed toward (or have almost no other options than) drug use, violence, criminality, and ineffective parenting.

Theoretical Model and Definitions

This paper draws from a long theoretical tradition in anthropology and criminology (Wolfgang, 1958, 1967; Wolfgang and Ferracuti, 1967; Curtis, 1975; Silberman, 1978; Blau and Blau, 1982; Currie, 1985; Daly and Wilson, 1988). However, most such theories assert that particular structural positions are characterized by high rates of violence because a significant proportion of people subscribe to and act in accordance with cultural beliefs that sanction violence. In a seminal essay, Wolfgang and Ferracuti (1967) extensively reviewed the intellectual traditions, defined key concepts, and reviewed a wide variety of statistical evidence suggesting the probable existence of a subculture of violence (see Note 1) in several parts of the world. Although no single unified definition exists, subcultures are “composed of values, conduct norms, social situations, role definitions and performances, sharing, transmission, and learning of values” (Wolfgang, 1967:146; see Wolfgang and Ferracuti, 1967:95–163 for development of these concepts).

Unfortunately, most research on subcultures, including Wolfgang's, calls for, but has rarely elaborated the content of subcultures and, in particular, the content of specific values and conduct norms (but see Johnson, 1973:9, 193–196). That is, what are the specific rules that govern the patterned behaviors and activities occurring within the subculture? Previous research on drug-use(r) subcultures has identified some values, norms, and conduct norms as central components from quantitative analyses of college students

For the purposes of this paper, values are defined here as shared ideas about what the subgroup believes to be true or what it wants (desires) or ought to want (Johnson, 1973:9). Values “may connote what is or is believed (existential), what people want (desire), or what people ought to want (desirable)” (see Note 2).

Norms (in general) “define the reaction or response which in a given person is approved or disapproved by the normative group (…and) has thus been crystallized into a rule, the violation of which arouses group reaction …. The norms that govern conduct will involve varying degrees of individual conformity to the shared values. The same norms may serve as a criteria for defining what is ‘normal’ or expected conduct and what is not” (Wolfgang and Ferracuti, 1967:101). “The sanction is an integral part of the norm … and raises a barrier against violation” (Sellin 1938:33–34; Wolfgang and Ferracuti, 1967:106).

Conduct norms (see Note 3) are defined here as those expectations of behavior in a particular social situation that are attached to a given status within the group (Johnson, 1973:9). Conduct norms are then social (or groups) expectations which serve to govern behavior in a given behavioral domain or at a specific location or time or during interaction with specific others.

In short, values constitute relatively abstract reasons or rationales existing within the subculture about why people should do something or some activity is approved (but no sanctions are mentioned). Norms constitute relatively general “guidelines” or informal rules about what individuals are expected to do or not do, and specify appropriate rewards (for conformity) or negative sanctions (for noncompliance). As conceptualized here, conduct norms regulate social groups, time, place, and govern specific behaviors; they are a “concrete” application of the (more general) norms consistent with subcultural values and beliefs.

Central to the analysis below are the conduct norms. This paper focuses primarily upon the conduct norms associated with the rearing and management of child(ren) and juveniles in households where drug use/“abuse” is a major activity of many adults. The primary concern in this paper is to infer several conduct norms regarding child-rearing practices evident in one household characterized by drug use and sales, aggression and violence, inadequate, neglectful, or abusive parenting, and low parental interest in education and skill development.

Conduct norms may be conceptualized in several ways. They can be seen as the effective “rules” (or concrete normative expectations) which govern the “flow of action” as specific persons interact with others and their environment to produce patterned behaviors. The consequence is clear: an individual routinely acts in accord with the normative system (and usually follows the specific conduct norms) of the subgroup(s) within which she/he functions. Conduct norms may also be conceptualized as the specific rules which persons “internalize” (e.g., those norms and values which are incorporated as major elements of the individual personality system—Sellin, 1938). These conduct norms may become so internalized in the person's psychological makeup and ingrained in their external social environments that the person functions as if on “automatic pilot.” That is, as a person goes about his/her daily life, almost all choices, verbal statements, and actions are governed (and largely predetermined) by these “invisible” conduct norms. During any given day, almost everyone automatically (and without conscious choice) behaves and speaks according to hundreds of different conduct norms governing behavior in dozens of different behavioral domains. Conduct norms may also be very “localized.” Specific conduct norms may be applicable for certain roles. In addition, families or individual households may develop conduct norms which are relevant only to members of that family or household; nonfamily outsiders are not expected to follow family norms.

Individuals may not even realize (nor be able to articulate) that they are following specific conduct norms, especially when the effective conduct norm (e.g., a woman is not expected to raise her children) conflicts with conventional values and self-image (e.g., a good mother cares for her children) that society emphasizes. Thus, many crack-using women claim to be “good mothers” because their mother (or other female relative) is caring for their children; they provide vague plans about how they are going to “clean up” and get their children back soon—but take no action consistent with such vague plans. Such women are, however, acting in direct accord with one major conduct norm of street life: drug consumption is more important one's family and children.

Conduct norms are not externally evident and do not exist in the physical universe. As “shared expectations,” they are often unstated and are rarely written down. Rather, they are “internalized” by persons and serve to “regulate” actions and interactions within specific social subgroups. Thus, conduct norms, and their content, are difficult to operationalize and specify in writing (see Note 4).

In the case study (below) of Island's household and the Smith family kin network, one highly deviant, multiproblem family followed a series of conduct norms which frequently transgressed the general norms of conventional American society and even the conduct norms existing among other low income African-American families without serious drug use problems. Yet, the conduct norms documented below for Island's household may be very similar among thousands of other family/kin networks where adult members engage in drug use/sale and other forms of criminality. Indeed, the senior author and other project staff have observed many similarities in the family experiences of other crack sellers and drug users (Dunlap, 1992, 1995). The content of the conduct norms identified for this specific family below are likely to reflect a larger set of norms prominent in low income inner-city minority families where drug/alcohol use is a central aspect of household life. It is beyond the scope of this paper to attempt to link the themes to the various massive literatures on child development, African-American family systems, child-rearing practices, family violence, poverty, drug use/ “abuse,” and many other relevant literatures.

Methodology

The data presented here were obtained during two ongoing studies. The first study, “The Natural History of Crack Distribution/Abuse,” is an ethnographic study of the structure, functioning, and economics of cocaine and crack distribution in low-income minority communities in New York City. To date (1997), over 700 subjects have been observed and their activities noted in field notes. In-depth tape-recorded interviews have been conducted with 296 subjects; the tapes' contents have been transcribed and analyzed. Several papers provide details of the qualitative methods used in the project, including respondent recruitment and interviewing procedures (Dunlap et al., 1990; Lewis et al., 1992; Dunlap and Johnson, 1994a, 1994b), hypertext techniques for analyzing large textual data sets (Manwar et al., 1994), and the use of case study methods (Dunlap et al., 1994).

The present paper is based upon an intensive ethnographic study of one multiproblem inner-city kin network headed by Island, a Black woman, 65 years old in 1996. The ethnographer, Dunlap, initially developed close rapport and conducted intensive interviews with Sonya and Ross, Island's adult children in 1989, and has maintained a close relationship with them ever since. Both were eager to have their family participate in this ethnographic research. Ross provided an introduction to and initial access to Island (also see Dunlap and Johnson, 1994a; Williams et al., 1992). Since the initial introduction, Island was open and friendly. A key to strong relationship with these three household members was the assurance of (and maintaining) complete confidentiality of what was observed and the information obtained during interviews. Dr. Dunlap has been the only “straight” (not drug user, not involved in street life) person these family members know and interact with on a regular basis. Dr. Dunlap has secured extensive cooperation with Island and many other members of this family/kin network. Between 1989 and 1996, Dr. Dunlap developed close relationships and rapport with many crack dealers and some of their family members. Island and her crack user/seller son, Ross, have provided over 20 hours of tape-recorded, confidential, in-depth interviews during 6 years of research. They have permitted the ethnographer to observe activities in their household for the equivalent of more than 50 full days over 6 years, and have frequently phoned the ethnographer to provide important information or to request assistance. Hundreds of pages of field notes based upon direct observations in the Smith household, and over 3,000 pages of transcribed interviews with family members, were available for analysis. Several papers forthcoming and published address related issues (Dunlap, 1992, 1995; Dunlap and Johnson 1992, 1994a, 1994b; Dunlap et al., 1996; Maher et al., 1996; Dunlap et al., forthcoming).

The second study, “Violence in Crack User/Seller Households: An Ethnography,” builds from the first study. Over 15 additional families with one or more crack user/seller adults have been recruited for in-depth study; selected family members have been carefully interviewed and directly observed on several different occasions for over 1 year. The conduct norms reported below for the Smith household are observed, in varying degrees, among all of these other households and with similar results among the children, juveniles, young adults, and middle age adults. Future papers will report additional findings not delineated here.

The analyses below emphasize Dr. Dunlap's direct observations in and field notes of this household, describing the patterned behaviors and conversations observed as a basis for attempting to infer and specify operative conduct norms associated with child care and rearing practices. These norms may be important precursors to establishing and/or maintaining participation in drug-use(r) subcultures and criminality in adulthood. Only patterned behaviors which were observed more than five times have been inferred as conduct norms. Direct observations were supplemented by analyses of transcripts in which interviewees reported events or situations from which one or more specific conduct norm(s) could be inferred.

While this analysis focuses upon one household/family kin system, there are several thousand households in New York City where a grandparent-aged adult (usually a woman like Island) is currently rearing grandchildren and/or greatgrandchildren whose parents have become crack users and/or criminals. The caregiving and rearing practices documented in Island's household appear to be quite similar to those in equivalently disadvantaged socially isolated households (Furstenberg, 1993). The operative conduct norms regarding child-rearing practices are then likely to be comparable in other families and households—although specific conduct norms vary in content and intensity and may be mediated by other factors including community resources (Sampson, 1992) and social capital (Coleman, 1990).

While families like the Smith kin network undoubtedly constitute a distinct minority of African-American families and individuals, such family systems and severely distressed households arguably generate a sizable proportion of individuals who become the clientele of social control agencies (e.g., jail, prison, probation, parole, drugs and alcohol-user treatment—Wallace, 1991, 1992) and social services agencies (e.g., foster care, youth services, homeless shelters) in major metropolitan areas (Johnson et al., 1990; Panel on High Risk Youth, 1993). Within this context, the extended kin network, an African-American cultural characteristic, may function like a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the extended family may keep children “given up” (see below) by their birth parents within the kin network and out of the foster care/adoptive system. On the other hand, when the guardian (usually a grandparent or female relative) kin network is enmeshed in drug/alcohol use and sales and criminality (as is the Smith family below), the kin network may provide a mechanism by which drug use and other dysfunctional behaviors are transmitted both within and across generations (Dunlap, 1992). In particular, widespread exposure to deviant conduct norms concerning child-rearing practices displayed by successive generations of drug-using adults may produce children who fail to gain the skills necessary for conventional roles but who routinely learn skills for criminality and substance use modeled by adults.

Although conventional society may judge Island (and other similar persons) as an “incompetent” caregiver for many reasons, Island's household was among the “least unstable” within her kin network (Dunlap, 1992) (see Note 5). Indeed, Island was the only person willing to assume caregiving responsibilities for children born to heroin- or crack-using adults within this network. We, therefore, do not wish to blame Island for faulty caregiving. Only she has shown the fortitude and inclination to endure life-long impoverishment, multiple problems, numerous crises and traumas, deaths, imprisonments, and problems in the family-kin system. She has also opened her life and those of household members to continual intrusions by a friendly stranger (the ethnographer), provided extensive background information on events, interpreted events and described the personalities involved, and verified the accounts of others. Most importantly perhaps, Island behaved normally toward children and young adults, allowing Dr. Dunlap to observe directly the actual patterned behaviors of child rearing and household management from which the following conduct norms were inferred.

The Case Study: Harlem Community, Island's Household, and The Smith Family/Kin Network

The Neighborhood

Island's apartment reflected the neighborhood. The apartment was situated in a drug-infested building on a block located between two main avenues in Harlem. This private apartment building was located across the street from public housing. The street was cluttered with trash, crack viles, and “winos” standing around socializing (laughing, joking, judging females who pass by, asking for money to get more wine, etc.) all day and late into the night. At one end of the block was a park, the main “hang out” area in the neighborhood. On a typical day the park is filled with crack sellers dealing crack, their bosses watching them, “look outs” for police observing, children playing, people coming to buy crack; people sitting on benches getting high, talking about sex to one another, and prostitutes trying to pick up tricks, etc. People begin to trickle in this park at around 11:30 AM. By the evening the park was full and “busy.” A stroll down the block revealed young people standing around, leaning against the iron gate separating Island's building from the building on the avenue. The young people were smoking “blunts” (marijuana mixed with tobacco). The street norm among such young people prohibits smoking crack or using heroin. Many young people were females who have their babies in a stroller nearby. They stand talking to the young males and other females.

The Building

Island's apartment was in a building which takes up nearly the entire side of the street, except for an abandoned school and a post office. Most young people were hanging out in the lobby of Island's building where sellers played dice and sold crack, cocaine, angel dust, and marijuana. Ross, Island's son, moved back and forth between the park and the apartment building selling his “wares.” Inside the building also, prostitutes turned tricks on the staircase. The hallway and foyer of the building were vibrant with such action both day and night.

The Apartment

Island's apartment, located on the first floor not far from the main entrance, had three medium sized bedrooms, a dining/living room, and a small kitchen with just enough space to have a refrigerator, sink, drain board on one side, and the stove and a cabinet on the other. The kitchen can be entered only via the hall because the entrance to the dining/living room was blocked with assorted furniture and boxes piled high. Generally, the house was unkept and cluttered with too many boxes and furniture—leaving little living space. Two dogs also lived in the apartment. Sonya had the back bedroom and her dog stayed in their bedroom tied to the bedpost. Her room was the neatest room in the house because she meticulously kept herself and her space clean. Island's room was full with a king-size bed, numerous boxes, chests of drawers, and a cabinet in which she hung clothes; it was overflowing with so many things that she could only enter the room and get into the bed. Ross' room had a bed and dresser, and was shared with his dog. Sometimes Walter, his cousin, slept on a “pallet” (see Note 6) at the foot of the bed. His room had a little more space because Ross needed room to move around in his wheelchair.

Changing Household Composition

This household was always full and seldom did it only consist of just the main residents: Island, Sonya, and Ross. After his birth in 1992, Desmond became a main member of the household. Numerous other relatives who were basically without permanent residence lived for short periods of time in Island's household. At the start of the study (1989– 92), the stable members of this household consisted of Island, Ross, Sonya, Norman, Joyce, Sam, and a boyfriend of Sonya (see Fig. 1). Over the years, the secondary household members changed constantly. Sometimes the household was so full that people were sleeping in the hallway near the entrance to the apartment, on both couches, on the floor, and anywhere space could be found to make a “pallet” and sleep. When Ross' children came to visit, they slept in the bed with Island, which was a privilege. Desmond did not have a bed of his own, but slept with Island in her bed. Thus, the household was full almost all the time with relatives and friends who are otherwise homeless. Generally relatives like Alvin, Rodney, Walter, Norman, Barbara, and others were adults whom Island has primarily “raised” during their childhood, but were now homeless as adults. Unrelated friends may spend a couple of nights or a weekend before moving on.

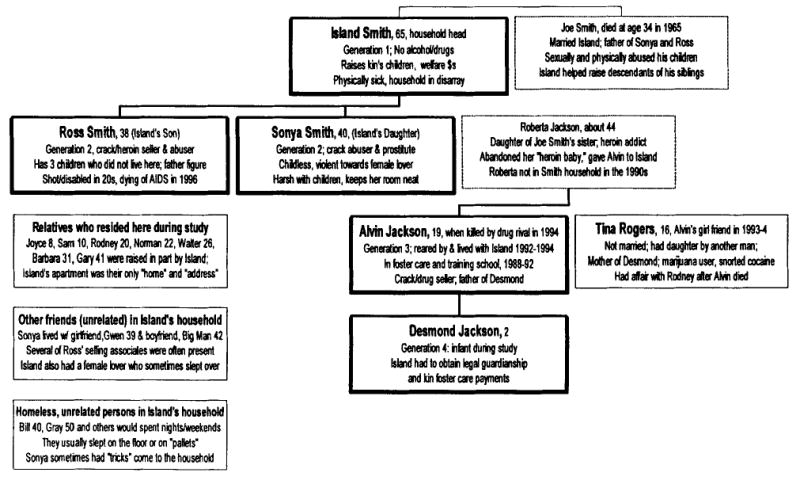

Fig. 1.

The Island Smith household in 1995.

The Smith family kin network is too large and complex to describe fully but is delineated more fully elsewhere (Dunlap, 1992, 1995; Dunlap and Johnson 1992, 1994a, 1994b; Dunlap et al., forthcoming).

Island Smith was born in 1930 in the Bahamas. Abandoned at birth by her mother, she was raised by her father and later, his wife, until the age of four. Upon the death of her father, Island remained in the care of her stepmother who moved to New York City in the mid-1930s. Island's schooling was cut short in order to help raise her stepmother's children (Island's “brothers and sisters”) by working at a low-wage cleaning job. At the age of 18, Island married Joe Smith, a migrant from the Carolinas (recently released from jail) with a penchant for alcohol and a job as a coal-hauler. Joe had 11 brothers and sisters, most of whom lived in the New York metropolitan area. Upon her marriage, Island acquired an extensive kin network, almost all of whom were “heavy” alcohol users. (See Fig. 1.)

Island gave birth to two children, a daughter (Sonya) in 1953 and a son (Ross) 2 years later. Island separated from her husband when he raped their daughter, who was then 6 years old. Joe died in a car accident 2 years later and Island's household soon became a place of refuge for the entire network of kin. In addition to her own children, Island has raised or helped to raise the children and grandchildren of her “brothers and sisters” and those of Joe's siblings (her in-laws). In this caregiver role, Island assumed temporary responsibility (often lasting several years) for rearing children during various periods of infancy, childhood, and young adulthood. While many of these children were at some stage placed in formal foster care, most returned to “Aunt Island's” home after “aging out” of foster care or upon their release from jail/prison.

During the fieldwork period, both Island's “natural” children were resident in her household. Her daughter, Sonya, is an ex-heroin user and current crack smoker who has worked as a prostitute since the age of 15. Island's son, Ross, is a “freelance” crack dealer with a long history of drug use and sales. The composition of this household is extremely fluid, and several children, assorted kin, and other unrelated persons often live in or flow through the household on a typical day. Island estimates that 89 of the children in her kin network have lived with her for significant periods of time. All of the children who have grown up or who are currently growing up in Island's household have been exposed to instability, frequent shifts of residence, poor supervision, harsh or erratic parental discipline, and lack of conventional nurturing (documented more fully below). None of the children that Island has helped to rear have become relatively conventional persons (i.e., managed to attain legal employment, abstained from drug use, or desisted from criminality). With the exception of Island herself, almost all members of this particular kin network either had been or was currently an user of alcohol, cocaine, heroin, or crack (or several of these drugs), drug seller, active criminal, or prostitute. As Island herself noted for some of the children she has raised:

Arthur…sixteen years I had him. Arthur had got in trouble by following somebody [Ross] selling drugs…. Norman, you see Norman was put away [prison]…. He got mixed up with the wrong crowd and went out there and robbed a cab…. And Barbara, just got out there and she started doing what her mother did (prostitution)…most of them are out there in the street. Barbara, too, she's in jail and Norman is in jail. Bobo he somewhere in Brooklyn. Roy and Kareema are out there in the street with drugs and what not.

The prognosis for the children Island is currently rearing is equally bleak. The family and home environment is transient and unpredictable. It is almost impossible for children growing up in this context to define themselves except in relation to the world of drugs and deviance that surrounds them. The wider kin network, rather than providing refuge from substance misuse, serves to reinforce the values and norms of the inner-city drug subculture, foreclose alternative opportunities to young persons, and further isolate these children from “mainstream” social and cultural influences. In the following sections the analytic focus is upon the informal rules and conduct norms in Island's household as these are established, maintained, and sanctioned by household adults for children and youths. The paper does not address how children respond, grow, and learn within these adult-driven expectations.

The Cognitive Framework: “Pay Attention” as A Learning Style

Within Island's household, a frequently heard phrase was “pay attention.” This apparently simple instruction summarized a complex cognitive framework which served both to organize and diffuse specific conduct norms associated with child-rearing practices. While the conduct norms are identified below, the cognitive framework or learning style implied by “pay attention” warrants elaboration.

While adults in Island's household frequently gave children or young adults direct or implicit instructions to pay attention, they rarely provided specific verbal explanations. That is, adults gave tasks to child(ren) but did not provide them with any instructions. The child would be told to do something and when they could not perform that task, the response might be one of ridicule, such as: “You don't know how to cook some rice! Pay attention the next time somebody cooks some rice and you'll know.” The child or youth was expected to know how to do something just because he/she had observed it. For example, whenever someone knocked on the door of Island's apartment, one of the children was told to open it. When the child fumbled with complex locks, the response might be, “What's the matter with you, you seen me unlock that door a million times and you don't know how to unlock the door? If you paid attention you'd know how to do it.” Or “You don't know how to role a joint! (Laugh) You know how to roll a joint!”

Adults used the statement with the intention of providing training. However, spending time with a child to help him/her master a simple skill was not part of such training. Children learned primarily by making mistakes, but were only told about the mistake, not how to do it right. If a child was hungry and asked for something to eat, Island responded, “Do you see me cooking! No! Who's in the kitchen cooking? Well pay attention and ask Gloria to give you something to eat.” [Another adult (Gloria) was in the kitchen cooking for herself and had no responsibility for the child.] Island was never observed giving verbal directions to a child about how to cook something. Likewise, she and other adults in the household were rarely observed interacting with children in an intentional effort to help them learn and master a variety of age-appropriate basic skills (e.g., ride a bike, open a locked door, sew a torn dress, etc.).

“Pay attention” directed the listener to carefully observe the behavior of adults; it was also an invitation to imitate that behavior (Bandura and Walters, 1963; Bandura, 1973). The speaker implied that “watching” would enable the “watcher” to master all the elements of a complex behavior by observation alone. Further, the speaker assumed that the observer would correctly infer the multiple motivations and processes acted out by the speaker. As Sonya told the ethnographer: “Watch me, I'll show you what prostitution is all about.” In the sense “pay attention” also served as a vehicle for avoiding a verbal articulation or abstract description of complex behavior patterns. Although her activities could be observed, Sonya could not articulate what she actually did. While it was apparent from observations that Sonya had a clear mastery of the subtle craft of enticing customers, obtaining money, and performing various sex acts, she could not provide the ethnographer with articulate and concrete verbal descriptions of her activities or an explanation of her reasoning or motivations. Adults and children only paid attention to the immediate present and what was happening “right now”; they did not attempt to generalize or summarize a phenomena and rarely considered the possible consequences of their actions, behaviors, and choices.

The directive to “pay attention” also failed to encompass reasons (why) to do or not to do something. Thus, adults, children, and juveniles failed to connect their immediate world and reality to either their own futures or to the larger society and its social values. Children growing up in drug-using families observed the outcomes of drug use among their parents and other adult members. When they became adults, most failed to make the connection between their own drug use and that of their adult models. As young adults they may well have chosen another type of drug (e.g., crack) to that preferred by their parents (e.g., heroin), but they failed to understand that their outcomes from crack use would likely be similar.

The conduct norms governing this particular social world (Island's household) held that only what you observed or experienced was “real” and “meaningful.” Abstractions, concepts, and written information were not “real,” and, therefore, not important. (Adult members were never observed reading newspapers or other written materials—even if they were literate.)

The major deficit of the “pay attention” learning style, however, involved the content of what children and juveniles learned from their (largely deviant) role models; that is, the deviant actions observed spoke much louder to individual child(ren) than the words from a few conventional adults (e.g., teachers, middle-class persons). Adults in the household routinely modeled many deviant behaviors and conduct norms which younger persons adopted as they grew up. The following sections provide detailed descriptions of specific conduct norms in several important behavioral domains, specifically: (i) Parenthood, (ii) Psychological parenting, and (iii) Protecting children. Some of the conduct norms regarding caregiving practices are provided in Table 1; only some of these are discussed in the text below.

Table 1. Content of Conduct Norms Regarding Adult–Child Relationships in Conventional Society and in Severely Distressed Households.

| Domain of behavior | “Ideal” in conventional society | Severely distressed households |

|---|---|---|

| Child conception | Child conceived intentionally | Children “happen,” most not wanted |

| Child anticipated as an “expense” | Child sometimes planned to obtain transfer payments | |

| Unplanned child will be loved/nurtured | Children may be called “mistakes” during childhood | |

| Birth father's role | Father acknowledges paternity legally and socially | Father's identity sometimes unknown by mother/family |

| Father gives child his last name | Birth father's last name rarely given to child | |

| Father financially supports children | Father provides no money to support his children | |

| Father emotionally supports children | Father will rarely see children, gives no emotional support | |

| Father will live with his children | Father will not live with his children | |

| Father will never harm children | If present, father may treat children as he pleases | |

| Birth mother's role | Mother will keep and raise children born to her | Drug-using mother will often not keep child |

| Child is a primary possession and responsibility | Drug-using mother seeks to “give” child to someone else | |

| Mother uses income to support children | Drug-using mother will often spend $s on drugs, not children | |

| Mother is primary psychological parent of child | Drug-using mother will rarely relate emotionally to children | |

| Mother spends hours daily interacting with child | Drug-using mother spends little or no time with children | |

| Mother regularly cuddles and express love to child | Drug-using mother rarely holds child, seldom expresses love | |

| Mother always retains parental/guardian role | Drug-using mother encourages oldest child to assume parent role | |

| Adult female and male sexual relationships | Man and women marry and stay married | Drug users rarely marry; if married, they often separate or divorce |

| Man and women live common-law for years | Drug users may have common law partners, but often several | |

| Man and women have some affairs | Drug users usually have sexual affairs; man leaves household rapidly | |

| Unrelated male give money/other goods to family | Drug using male provide no $s, uses family's food and shelter | |

| Adult caregiver role (other than birth mother) (sometimes birth mother) |

Caregiver treats children like a mother | Caregiver “removes” child from caregiving by drug-using mother |

| Grandparent(s) occasionally care for child | Grandparents/relatives often expected to assume parental role | |

| Caregiver loves/supports child | Caregiver resents having to care for another child | |

| Caregiver provides good food, shelter, health care | Caregiver provides marginal food, shelter, medical care to child | |

| Caregiver routinely expresses love in many ways | Caregiver rarely loves, cuddles, expresses affection to the child | |

| Caregiver constructs safe environment in home | Caregiver does not systematically protect child from harm | |

| Caregiver ensures that school work is done | Caregiver does not help child with school work or education | |

| Caregiver carefully screens temporary helpers | Caregiver temporarily allows unrelated persons to care for child | |

| Caregiver has enough income to support child | Caregiver often wants welfare/foster care payments for child | |

| Caregiver provides direct instructions to child | Caregiver expects child to learn tasks by “paying attention” | |

| Caregiver has child trust authorities/agency staff | Caregiver warns child not to trust/speak to staff of agencies | |

| Child's roles | Child learns age-appropriate tasks/behaviors | Child given little or no training in age-appropriate tasks |

| Oldest child supervised by parent | Oldest child becomes “most responsible” person in household | |

| Parent always responsible for child's care | Oldest child takes care of parent and household by default | |

| Oldest child helps, not responsible for siblings | Oldest child often care for younger children | |

| Child often interrupts adult talk/activities | Child learns to be “seen” but not “heard” by adults | |

| Emotional relationships between guardian and child | Child trained to plan a long, productive life | Child does not expect to live long, and to die young |

| Child learns that current life affects future | Child does not learn that current activity will affect their future | |

| Child uses/trusts adult(s) as resources | Child learns not to trust adults and that adults have no resources | |

| Child learns to express love to guardian | Child does not express love/affection to parent/guardian | |

| Child and family contacts with outsiders and agency staff | Child honest/open with agency staff | Child conceals and enables illegal behaviors of guardian/adults |

| Child is loyal to family and its history | Child taught to keep many family behaviors secret from outsiders | |

| Child helped to plan how to access good jobs | Child does not plan for future in conventional society | |

| Child gains access to legal support systems | Child cannot learn to use “conventional means” to get legal jobs | |

| Child can seek help from service providers | Child learns never to seek help for problems from service providers |

(i) Conduct Norms Regarding Parenthood

A key feature of drug-using kin networks like Island's was the attenuated link between childbearing and child rearing (see Note 7). Few persons of either gender reaching adulthood in the 1980s and early 1990s were or ever had been married, and no marriages survived more than 5 years. Almost all of the women had children, sometimes several by different men. While crack users were consistent in their failure to assume responsibility for raising and nurturing their child(ren), the tenuous connection between giving birth to a child and raising that child was evident throughout the kin network.

For example, Alvin was Island's nephew on her husband's side. Alvin's mother (Roberta Jackson) was a heroin user who had been unable to care for him; she “gave” Alvin to Island to raise when he was 6 months old (in 1975). Island was Alvin's primary caregiver and effective “mother.” Alvin had been convicted and imprisoned for drug sales in his teens and continued to sell crack and drugs upon his release from jail. In 1993, Alvin brought his girlfriend, Tina (then age of 16), in Island's household to live with him. Alvin and Tina smoked marijuana, angel dust, snorted cocaine, and drank beer and wine on the stairway most days, but they avoided crack use. Tina subsequently became pregnant and gave birth to a son, Desmond, in 1993. Upon her return from the hospital, Tina did little to care for the baby. Island was often angry because Tina rarely changed, bathed, fed, gave a bottle to, or held the baby.

One day Island [was] watching television and Ross was putting on his clothes, [when] Tina and Alvin came in with a lot of packages. Tina had a shopping bag with boxes in it and wrapping paper, a large doll, and a broom and cleaning set for a little girl [gifts for Tina's previous child who was being raised by her former boyfriend's parents]. Alvin stopped and played with the baby [Desmond]; Tina told Alvin to take the packages into the bedroom. After they walked into the bedroom, Ross and Island began to complain [to each other and Dunlap] that Tina had not bought anything for her own baby. She did not acknowledge Desmond either—as Alvin had done. Tina simply argued about carrying the packages and then went into the bedroom. This made Ross and Island very upset. Ross puts himself in the chair and goes over to the baby and kisses him and says it is OK because the baby's grandmother [Island] would buy him something. Island said to me [Dunlap], “see what I tell you, she [Tina] does nothing for the baby, but that's alright!” Island was visibly angry. She put the baby on her lap and made no other comment; her look was one which displayed that she was not pleased with Tina for not bringing the baby anything.

The ethnographer observed Tina hold or change her infant only twice (and for only brief periods) during the 4 months she was in the household. Alvin would play with the baby occasionally but was never observed performing child care tasks; while doing so, he verbally insulted Tina:

This baby takes after me, not her (Tina) because she's ugly. (And repeated this several times while Tina was listening.)

Island effectively became the baby's primary caregiver. Tina planned to “give” Desmond to Island and Island was preparing “papers” to obtain legal guardianship. These papers were not signed because Tina wanted the welfare payments, but not Desmond. When Alvin was shot and killed (see Note 8) in February 1994 at the age of 19, Tina began an affair with his cousin Rodney, raised (in part) in Island's house; Tina showed no further interest in raising Desmond. Similar disinterest in child rearing was shown by others in the Smith family kin network.

Key conduct norms regarding parenthood inferred from field observations and interviews are outlined below.

- A child's father was not expected to help rear nor to make financial contributions to the child(ren) he sired. Almost no males in the Smith kin network born after 1950 resided with their natural child(ren), nor did they make any routine financial contributions to the households rearing their child(ren). Most fathers knew little about their child(ren), and many had no contact with them. Alvin was more involved with his infant son, Desmond, than most fathers—but his limited “fathering” ended with his premature death. If and when fathers maintained contact with their child(ren), they would occasionally provide a small gift or buy the child a present when asked, but never provided anything resembling child support payments (Dunlap and Johnson, 1994b). Island's drug-selling son, Ross (age 38), had three teen-aged children by a woman.Dunlap: What did you do with your money that you make when you were selling….Ross: Bought clothes, went out and partied, took trips.Dunlap: OK.Ross: But I was not giving it to my kids and stuff. The rest of the money I had I took and bought clothes, drank, had trips and partied. And I partied.Dunlap: And then you used the money for your kids also. And for your family, how about your family?Ross: Only my mom and my sisters.Dunlap: So your family then?Ross: Yeah.Dunlap: Your immediate family, but not your kids or their mom?Ross: Yeah.

While a young woman was vaguely expected (as a value) to rear the child(ren) born to her, she was not expected to create and maintain a household (see Note 9). Few women born after 1950 in the Smith kin network established and maintained their own households. Like Tina and Florence (below), many of these young women and their children were incorporated into existing households. Very few of the women born after 1950 resembled the stereotypical “welfare mother” (Lubiano, 1993) who established and maintained her own household and reared her child(ren) supported by welfare payments (see Note 10). Although many women in the Smith kin network had several illegitimate children and some were occasionally in receipt of AFDC benefits, very few were able to locate and maintain their own apartments. More often, young women and their children were incorporated into the households of their mothers and other female kin. Within these households, the grandmother (or aunt) was often the effective primary caregiver of the women's children, though not always a legal guardian.

Drug-using women were not expected to (and most did not) rear their child(ren). Such women expected to spend most of their limited financial resources and time pursuing the drugs they used and their social life. Tina and other women devoted very limited material and emotional resources to the care of their child(ren), especially after the child was 6 months old. Thus, neither the birth mother nor birth father were likely to be significant adults involved in their child(ren)'s upbringing.

Drug-using women expected to “give away” their children or anticipated having them removed from their care by official agencies (Roberts, 1991; Maher, 1992, 1997). Key kinspersons were expected to intervene and remove children being reared by heroin- and crack-using women. Drug-using women in the Smith clan often sought out and “gave” their infants to a relative to raise or “assumed” (as did Tina and Alvin) that the relative would provide care if they did not. More precisely, drug-using women felt that they were being good mothers when a kinsperson (mother or aunt) was responsible for caring/rearing their child(ren) (Dunlap, 1992). Failing the availability of willing kinspersons, a relative might contact child protective services and the child would enter foster care and/or adoption—as had Alvin, Rodney, and several other Smith relatives. One afternoon the following was observed: Sonya was working (prostituting). Another crack ho'—who was about 8 months pregnant—asked Sonya if her mother (Island) would take her baby. When Sonya said no, the woman asked for help in finding someone to “give” her baby to when it was born.

- Kin often did not know who the father of a child was, generally did not want to know, and avoided attempts to learn of or involve the father in parenting. Of these children born from various periods of cohabitation, Island often knew who the father was, but displayed no interest in contacting these men or seeking their assistance. Moreover, the fathers of several children were either dead, homeless, or serving long-term prison sentences. Although the mother of Sonya—who had a 25-year career as prostitute—Island condemned an unrelated neighbor as a “slut” for having sex for drugs.Island: Florence is pregnant with another (her third) baby. They are “staircase babies” 'cause Florence will have sex with anyone that wants her for some marijuana or crack. She ends up having sex on the staircase. Her babies are 1 year apart and all by different males. She does not know who her babies are by because she has sex with any and everybody outside on the stairway. She's not 20 years old yet. Her (Florence's) mother drinks (alcohol) heavy and has a boyfriend who causes chaos in the house every now and then. Florence asked me (Island) to take this next baby since her mother was now caring for her first two babies.

A key kinsperson (often a grandmother, aunt, or other older woman) was expected to assume responsibility for caregiving and rearing child(ren) (Troester, 1984). Among persons born after 1950, few of the Smith kin had a steady legal income with which to support a family or household. Only kin with households (usually grandparent-aged persons in the mid-1990s) had steady enough incomes (from jobs, social security, pensions, or other sources) to afford to maintain households. In addition to grandchild(ren) they may have been raising, such kinspersons were also expected to provide food and shelter for their adult children or kin (usually without payment from such persons or from the welfare system).

(ii) Conduct Norms Regarding Psychological Parenting

One of the significant features of child-rearing practices within the Smith kin group was the near absence of what the child development literature refers to as “psychological parent,” the one person with whom the child becomes most deeply attached, and the most trusted adult in the child's life (Bettelheim, 1988). While the caregiver provided for the child's instrumental needs (food, clothing, shelter, some health care), Island and other adults demonstrated little awareness of a child's psychological states, or their need for affection and support (Bettelheim 1955). Several conduct norms relevant to psychological parenting were inferred from direct observations and interviews with the kin network.

Children were neither expected, nor were able, to develop strong affective bonds with their birth parents. Few of the children in the Smith kin network had the opportunity to interact with and relate to their natural parents. Either the parents were entirely absent from the household (e.g., in Desmond's case, Alvin was dead and Tina was on the streets) or were only occasionally present. Even when a natural parent was “living” in the household, they were not expected to relate to their child(ren) and express strong affective ties. If the natural parent did relate to the child, it was on the same basis as did other adults to whom the child was “passed around” (see below).

- Kin caregivers rarely provided more than basic shelter, food, and clothing. While Island provided clothing, food, and a place to sleep for the children in her care, many aspects of effective caregiving (e.g., age-appropriate nutrition, separate sleeping arrangements, etc.) were clearly absent, as is evident from the following fieldnote excerpt.[Summer 1994] Desmond now sleeps with Island in her king-sized bed along with another 10-year-old cousin, Sam. Desmond has no crib of his own. Island regularly fed, changed, and bathed him. If he cries, adults give him something to eat. Island fed Desmond (at 6 months) the same food that adults eat. This included: potato chips, lots of candy, sometimes with nuts, and ice cream. Island was never observed feeding Desmond standard baby food (like strained peas). Whatever adults were eating (e.g., sweet potato pie), they gave the same to the baby. Everyone who picked him up usually gave him something to eat. As a result Desmond was extremely fat for a baby of his age.[Summer 1995]. The doctor tells Island to give Desmond standard baby food, and greatly reduce the amounts. Island “pays him [doctor] no mind” and continues feeding Desmond high calorie foods.

- The primary caregivers did not expect to develop strong affective bonds with the child(ren) in their care. Most Smith kin reported having had several caregivers during their childhood. Caregiving was varied during the course of a day. Other adults and adolescents, both within and outside the household, were called upon to provide intermittent caregiving to infants and young children.Island asked everyone to hold or watch and care for Desmond, even complete strangers. We sat on the park bench to keep cool from the heat of the day. Desmond sat in the carriage. Across from us sat a group of senior citizens. Desmond was eager to get out of the carriage, so Island let him walk around, but did not pay much attention to him. The senior citizens used their canes to keep him from going into the street. A wino from the building came and sat down. Island asked him to watch Desmond. He plays with Desmond for a while, but said to Island, “I can't take care of him now.” But he put Desmond in the carriage and took him to the store, bought him an “icey,” and brought him back. Desmond ate the icey in the carriage. Sam (a 10-year-old cousin) came. Island told him to watch Desmond. Sam plays with him for a while then puts him back in the carriage. Next a young girl (about age 14) from the building comes and takes Desmond to another area of the park where older children play; she plays with him for an hour. She returns him to the carriage. Aunt Barbara arrived and looked after Desmond for a while. At no time did Island pick up, play with, or intentionally stimulate Desmond—although she occasionally “talked at” him when he indicated wanting attention.

- Displays of physical affection were, for the most part, limited to infants. The primary caregiver was only expected to provide limited affective bonding. As an infant Desmond received occasional hugs from Island in 1994, but she was never observed kissing him. As a 1-year-old in 1995, such hugs from Island occur less often. Sam, at age 10, received no hugs or other forms of physical affection. Desmond never cried out for Island nor for any specific person and went willingly with anyone who cared for him. He did not seek out specific adults to play or be with him. Instead, adults often joked about the child's attributes.Island: He (Desmond) needs a bra—because his breasts are so big!Ross: He's (Desmond) such a pig. Alvin (Desmond's father) was fat like Desmond, and got his nickname after a show where fat Alvin was a character.

- Adults routinely ignored or provided harsh treatment to child(ren) who sought adult attention or help. Thus, children and juveniles learned not to ask adults for help or to seek their permission or approval.Sam was standing on the ramp trying to make sense of what was happening. He asked the simple question, “Can I go?” He received little response. At first they did not pay him any attention. He was told, “she (your mother) isn't here, she's at the funeral.” That was not an answer to his question. He stood and listened to what we were talking about—who was or was not going to the funeral. He listened awhile, then went off to play somewhere. No one ever explained anything to him about Rodney's death. Whatever he learned came from paying attention and listening to adult conversations. But no one ever sat down with Sam and explained how Rodney died, or what happened, or how Sam felt about his death. (Rodney was an older cousin who had lived with Sam as an older brother in Island's household about 5 years earlier.)

Family life was not organized so the primary caregiver could spend time alone interacting with the child(ren). Neither Island nor any of the other adults in the kin network were observed interacting with children, reading stories to them, or spending time one-to-one with a child or juvenile talking about issues of interest to the child. The closest exception to this conduct norm was television viewing. One or several adults would frequently watch television in the company of children. However, television viewing in the Smith family household was dominated by adult programs such as films, sitcoms, and soap operas. Children were never observed watching age-appropriate shows such as Sesame Street or cartoons.

- Caregivers were not expected to assume responsibility for organizing children's activities and free time activities. Adults displayed little interest in children's education so that children were often discouraged from doing homework.Joyce (age 8) tries to tell Island about her homework. Island tells her to “go and sit down” or she will “tear up the papers.” The child goes and sits on the couch and attempts to do the homework. Meanwhile, a lot of action is going on (baby crying, people coming in and out and talking, Island looking for the baby bottle and a clothes bag for the mother, etc.). Eventually the mother leaves with the crying baby; Island is glad and relates this. Joyce, trying to do her homework, gives up, puts the papers on the table, and begins to play with the other kids.

Adults rarely “planned for” children's activities or special events. Thus, if Island wanted to go out to a movie or visit a relative, the child(ren) might be brought along—if Island could not find someone else to care for them. However, taking the child(ren) along was perceived as a burden and not as an opportunity to enrich the child's life. The Smith adults showed little or no awareness of understanding and encouraging children to pursue age-appropriate interests and activities.

(iii) Conduct Norms Regarding the Protection of Children from Harm

An important expectation which society places upon parents and caregivers is that they protect children from a variety of physical and social harms. In particular, caregivers are expected to engage in proactive prevention by creating a physical and social environment in which children will almost always be safe. For the most part, Island's household was not systematically organized to prevent harm to children. Located in a subsidized building, the apartment contained a kitchen, living room, two bathrooms, and three bedrooms.

- Adults were not expected to construct a safe household environment for children. Children were confined for the convenience of the adult:Island's principal strategy to protect Desmond from physical harm was to confine him to a playpen full of stuffed animals. At the age of 10 months, Desmond could not climb out. Many times, however, dangerous objects were left around the house while Desmond crawled around. For example, the flower stand from Alvin's funeral could easily be pulled over. Children were often not warned about potential dangers. Ross' dog was trained to attack and had badly bitten and scarred another adult in the household. The dog and cat currently ignore Desmond, but whether they will be able to do as he grows older remains to be seen.

-

Adults were not expected to hide or conceal their drugs, drug paraphernalia, consumption, or related behaviors from children. Children were routinely exposed, however, to adults engaged in other quasi-deviant behaviors. By 2 years of age, Desmond had learned from Ross how to shoot dice. One day,Desmond is in the middle of the floor shooting … a set of red dice … with another (adult) female who looks like a crack user. She is playing with him and he is showing off that he knows how to shoot dice. Ross comes in, makes them stop, fusses at the woman, and she leaves. I say, “You know Desmond is always showing people he knows how to shoot dice.” Ross relates, “Yea but he don't need to be shooting it with her.”Children are astute observers of what adults are doing. Shortly after Desmond learned how to talk at about age 2, Island permitted Mark, a crack-using, unrelated man, to live in her household while dying of AIDS. Desmond demonstrated that he had learned the adult language of the household while “running” with Ross and other drug sellers (but never playing with children his own age).Island: One day, Mark was high (on crack) and nodding on the couch, Desmond observed him and said, “Mark fucked up, mama, Mark fucked up.” When Island's female friend tries to talk to him, Desmond replied, “Leave me alone and get out of my face.” Desmond is a lot like Alvin (his dead father) was when he was little, and is very aggressive. He is not afraid of anyone!Dunlap: Desmond is the type of kid that may perhaps be the bully of the class.Adults (without forethought) frequently left alcohol and drugs easily accessible to children. Ross verbally condemned adults who smoked crack in front of their children, but was not overly concerned about children observing his business in the household.Ross: Un hum. With their children, with their husbands, and they both smoke (crack). I remember one time I cooked something, I gave 'em a piece (of crack). Little girl's (age 9) standing right there. They smoking with a little girl standing right there looking at 'em. I ask 'em, I said why do you all do that. She goes to school, man. I said how ya all feel that girl goes to school and say my daddy and mother smoke crack in front a me.Eloise: She watch her parents smoke crack?Ross: They let her watch.Ross: Now you wouldn't believe, the lady's 44 years old. She's been doing crack for since I don't know how long, and the husband, he's 41, and he's running back and forth to store for people. He standing out there waiting for somebody to call him. You can be in the house, you hear this [whistle sound]. Right? That's the call. Somebody want him to go to the store. (The man was a go-between and low-level distributor who was hired to transport crack from a hidden location [“store”] to other sellers.)Ross often “hid” bundles of crack vials in the corners of the easy chairs or other recesses in the house. Sam, aged 10, could easily have found them accidentally. Various adults have “parties” in the house, leaving alcohol, cocaine, and other drugs openly accessible.For the most part, however, adults zealously guard their drugs and consume them rapidly, so in practice, children may have limited access. In some instances, adults misused alcohol and over-the-counter medicines by using them to sedate infants and young children.Island sent Desmond to her sister, Judy (age 65). Island knew that Judy gave children alcohol to put them to sleep. Judy gave Desmond some gin to help him go to sleep, but it made him sick, so both Judy and Island had to deal with a sick baby.Child rearing does not take place solely within the family or “under the roof” (Sampson, 1992). Conduct norms revealing the failure of caregivers to protect children from harm were often reinforced at the neighborhood or community level. Field observations in Central Harlem indicate that when children are taken to the park, they can hardly fail to observe nearby adults (frequently intoxicated) engaging in a wide variety of deviant and illegal behaviors including the consumption and sale of illicit drugs, violence, and acts of prostitution. While Dunlap was observing Island and Sonya in the park, others were present. Benny was selling ‘red top’ crack vials; Headband was the look-out, and Dennis was her 5 year old son. The owner of the crack (Benny's boss) was also watching Benny and Headband.The crack users play with the children of their comrades (in the park). Dennis had been walking around saying ‘red caps’ loudly. Benny got angry because the police would know what he was doing and he would get busted. He did not say it in a nice manner. “Shut the fuck up! Shit! Don't you know cops hear you, I'm fucked! Shut that motherfucker up!” I talked to Headband and asked where she lived. She says she stays out here in the park. I asked whether her son stays with her. She says that he stays with her mother sometimes. Today is the second day I have seen them out here. Benny had bought some chicken wings for Headband and the little boy to eat.

- Intermittent supervision and caregiving responsibility often fell to unsuitable adults and other children. Infants and younger children were sometimes left unattended or under the supervision of older children. Adults known to have inappropriate and/or illegal behavior toward children were expected and permitted to provide intermittent responsibility for children in the absence of the usual caregiver or other adults. Adults entering Island's household were not “screened” for their capacity to harm children. Several unrelated persons or distantly related persons came and went during the fieldwork period, as evidenced in the following fieldnote excerpt about a nearly juvenile-aged boy.Sam (age 10) spends a lot of time with Gary (a 41-year-old male relative) who is good to Sam and does many things for him. Gary provides Sam with a lap and affection (which Island does not provide). Island tells me [Dunlap] that “Gary likes little boys! He's gone with other boys in the building.” Homosexuality or bisexuality, however, was considered normal in this household. Island, Ross, and Sonya have all had sexual partners of their same gender. (Two years later: Gary died of AIDS, never having told Island or others he had HIV or AIDS).

- Adults were not expected to provide routine preventive medical care for children (see Note 11). Caregivers did not have children vaccinated for childhood diseases. Various over-the-counter children's medicines were not in the apartment. Children frequently had life-threatening illnesses. For example, Desmond suffered from asthma, as did many of the adults in the household. Moreover, the kin network sometimes interfered with emergency medical care when children were ill, as is illustrated in the following excerpt.In the evening, Island takes Desmond (at 6 months) home and gives him a bath, but his breathing is getting tight due to his asthma. She has a machine for his asthma, but didn't have medicine for the machine. She took Desmond to the emergency room. Island asks me [Dunlap] to hold Desmond while he gets his medication. Desmond was still wheezing. An Asian doctor came, puts him on the table. He asked Island to take off his undershirt, but she refused because Desmond might catch a cold. She held up the undershirt for him, while the doctor listened to his chest. The doctor acted like he didn't want to touch Desmond. This made everyone mad. Meanwhile, several female relatives and friends (“street women”) arrived at the bedside (they were high on crack). When the doctor started giving care to Desmond, the women began commenting: “Look at that motherfucker, look what he doing!” “I bet you don't do your own that way.” “Niggers ain't shit.” “I get your ass outside, I kick it all over the place.” The doctor got a security guard who put everyone out of the room, except for Island and Desmond.At age 2, Desmond was diagnosed as slow and needs special education because his speech is slow and he cannot pronounce his words correctly. Island was not going to let anyone give him any drugs, but she did not get it straight what they recommended.

- Adults were not expected to maintain an orderly and comfortable household for themselves or for the child(ren). The lack of attention to hygiene, safety, and spatial organization in this apartment indicates an absence of awareness of the need for environmental management.July 1994 was very hot—usually above 90° with very high humidity most days. The lock on the front door to Island's apartment was broken. One bathroom had so much junk piled in front that it couldn't be used. Upon entering the living room, a lot of boxes were piled up and all around the left side. The flower stand from Alvin's funeral was near the entry obscuring foot traffic. On the right side was a deep freezer with stuff piled on it. Three big easy chairs were in front of the television, with a couch and coffee table with a lot of pictures. The window had plants and vines. So cluttered was the living room that there was only enough space (about 30 inches) to walk through the living room. Ross had an aggressive and unpredictable dog that could potentially hurt members of the household. The cat runs around. Several little puddles of urine and dog feces are found around the house. I [Dunlap] never saw anyone walk the dog or take him out of house. Ross wanted the windows kept closed at all times [with no air conditioning]. Island had a fan in her bedroom but kept the window closed. The house was so hot and miserable and smelled so badly that I [Dunlap] hate going there. I tried my best to conduct interviews and observations outdoors or in restaurants.

In these and many other ways, Island and other caregivers do not routinely act to protect children from physical and emotional harm, or to shield them from various activities that are considered deviant in conventional society. While their inaction often constitutes neglect, it usually does not result in children being removed by protective services. Nonetheless, this long-term form of borderline neglect holds important consequences for child development and, in particular, for the ability to resist drug misuse and criminality (Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986; Widom, 1989a, 1989b) in young adulthood.

Conclusion

While the family or household typically provides the foundation of a child's upbringing and acts as a site of intellectual and social accomplishment, it can also serve as a training ground for antisocial, deviant, and criminal behavior. This paper has attempted to identify and document the key conduct norms governing child-rearing practices in an inner-city, multiproblem household characterized by the presence of several drug-abusing adults. Expectations of behavior, governed by specific content norms, dramatically shaped the physical, social, and emotional environment in which the children in the household under study were raised.

The “pay attention” style of learning stressed direct observation of actual behavior by adults. This observed learning process socialized children to believe that only what they saw was important. Adults provided children with little or no understanding of the detailed procedures, reasons, and abstract rationales for given activities and behaviors. Entirely neglected by caregivers (and hence not learned by children) was the importance of other forms of learning: direct one-to-one instruction, learning via books and written documents, lengthy discussions about the pros and cons of a behavior or issue, and critical analysis of options and choices.

Equally harmful was the fact that the adults whom these children observed were primarily modeling deviant and/or illegal behaviors, as well as acting according to conduct norms that were considerably discrepant in many ways from those found in conventional households. That is, the children observed in this household were not routinely exposed to adults engaged primarily in conventional lifestyles or behaviors. Caregivers did not organize the household or their lives to go to work at a legal job, earn “honest” money, or participate in conventional institutions (e.g., church, community organizations, etc.) Rather, caregivers and other adults in the Smith household routinely modeled behaviors (and observant children inferred the relevant conduct norms) about how to sell and use drugs, prostitute, gamble, stay up late and sleep late, ignore household maintenance, shift childcare responsibilities to others, and a host of related activities, all of which may interfere with learning conventional behaviors, and have been shown to predict later deviance (Loeber and Stouthamer-Lober, 1986).

Further complicating the social learning processes evident in this household was the near absence of caregiver attention to protecting children from harm, especially at the hands of those who provided temporary caregiving, often without the primary caregiver overseeing it. Another, more intangible consequence was that children did not have a psychological parent and often failed to form strong affective bonds with either their primary caregivers or their birth parents. Rather, children learned not to trust either their primary caregiver or other adults in the household. Adults often chastised children for not knowing something— but adults made no attempt to explain the phenomenon. The Smith adults were seldom observed helping children learn important and age-appropriate skills. Indeed, many children came to despise or hate some of the adults who cursed at them, ridiculed their behaviors, misled them about something, and physically and/ or sexually abused them. In the household studied here, the end result of such child-rearing practices and conduct norms were young adults who had neither been loved nor attached to a loving adult, who often hated or disliked the persons responsible for the childhood, who were frequently angry, often filled with rage, and who engaged in various forms of violence, illegal activities, and high risk behaviors.

Almost all of these conduct norms, internalized during childhood and acted on as young adults, were fundamentally incompatible with those of conventional society. When combined with their lack of formal education and severe skills deficits, living their lives according to these conduct norms clearly interfered with the ability of young adults to obtain legitimate employment and to lead conventional lives. The only occupations actually open to young people like Alvin, Rodney, Tina, and others in this particular kin network were drug selling, prostitution, and other forms of criminal activity. However, while they had observed others engage in these illegal occupations and were aware of the appropriate conduct norms, the absence of a mentor-based training system to help youths learn the subtle art of avoiding arrest/incarceration or being shot by rivals, meant that most also failed to become relatively “successful” criminals. Many persons in the Smith kin network had been killed (like Alvin and Rodney), had been incarcerated for long periods (like Norman and Arthur), or were active drug users and homeless (like Roy and Bobo). Ross was a relatively successful (without arrests) crack seller in the 1985–94 period, but he had been shot in a drug dispute and crippled at age 24; he was dying of AIDS in 1995. Sonya remained an active prostitute, although she had numerous arrests and was incarcerated in her twenties.

For younger children—many of whom constitute the fourth generation of inner-city drug-using households—the future looks very bleak. The grandparent (Island's) generation is rapidly aging; many primary caregivers will die or become incapable of rearing children by the year 2000. Few members of the second generation appear capable of assuming caregiving responsibilities for their grandchildren. Moreover, both the macrolevel social forces (Dunlap and Johnson, 1992) within American society and the general directions of federal and state policy (more reliance on criminal justice sanctions and incarceration, combined with less support for welfare, social services, and housing supports) suggest that children born into and reared in drug-using households (like Desmond and Sam) will likely have futures which, at best, resemble their parents.