Summary

Microbes found on the skin are usually regarded as pathogens, potential pathogens or innocuous symbiotic organisms. Advances in microbiology and immunology are revising our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of microbial virulence and the specific events involved in the host–microbe interaction. Current data contradict some historical classifications of cutaneous microbiota and suggest that these organisms may protect the host, defining them not as simple symbiotic microbes but rather as mutualistic. This review will summarize current information on bacterial skin flora including Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Propioni-bacterium, Streptococcus and Pseudomonas. Specifically, the review will discuss our current understanding of the cutaneous microbiota as well as shifting paradigms in the interpretation of the roles microbes play in skin health and disease.

Keywords: bacteria, immunity, infectious disease

Most scholarly reviews of skin microbiota concentrate on understanding the population structure of the flora inhabiting the skin, or how a subset of these microbes can become human pathogens. In the past decade, interdisciplinary collaborations at the interface of microbiology and immunology have greatly advanced our understanding of the host–symbiont and host–pathogen relationships.

There is surprisingly little literature that has systematically evaluated the influence of the resident cutaneous microflora in skin health. Primarily, studies have been conducted to analyse the types of microbes present on the skin and their pathogenic roles, with sparse attention given to other functions. The goal of the present review is to summarize current information on bacterial skin flora with special emphasis on new concepts that go beyond the narrow perception of these organisms as only potential agents of disease. Through an analysis of the limited current literature, we highlight a new hypothesis that suggests skin microbes directly benefit the host and only rarely exhibit pathogenicity. In this model, the delicate balance of the skin barrier and innate immunity combine to maintain healthy skin, and disturbance of this balance can predispose the host to a number of cutaneous infectious and inflammatory conditions.

Does the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ apply to the skin?

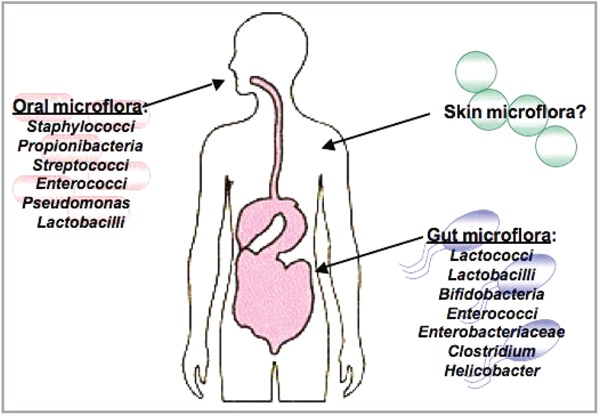

Several studies on noncutaneous epithelial surfaces have shown that the surface microflora can influence the host innate immune system (Fig. 1). Observations include how indigenous microbiota enable expansion and maintenance of the CD8 memory T cells in the lung,1 how gut microflora influence inflammatory bowel disease,2 and how lactobacilli in the intestine educate prenatal immune responses. These findings complement several studies that suggest disruption in microbial exposure early in development may lead to allergic disease.3,4

Fig 1.

Resident microflora that are beneficial to the host. The gut and mouth contain many species of microflora. Microbiota in the intestines protect the host by educating the immune system and preventing pathogenic infections. These microflora benefit the systemic immune system of the host and positively affect other organs, such as the lung. In the mouth, over 500 species of bacteria protect the mucosa from infections by preventing colonization of dangerous yeasts and other bacteria. It is yet unclear if the microflora of the skin play a similar role in protecting the host. Image from http://www.giconsults.com with permission.

The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ stipulates that exposure of T regulatory cells to intestinal microbes generates a mature immune response that decreases reactions to self-antigens, as well as harmless antigens from nonpathogenic microbes.5 Such a beneficial effect of microbiota in the gut has been used to support the use of probiotics. For example, Lactobacillus acidophilus secretes antibacterial substances that can prevent adhesion and invasion of enteroinvasive pathogens in experimental models such as cultured intestinal Caco-2 cells.6–8 Furthermore, oral administration of various probiotics has been associated with reduced colorectal cancer and active ulcerative colitis in some clinical studies.9,10 Although these approaches remain controversial, the benefits of resident gut microbiota are being actively explored through a variety of trial therapeutics and disease prevention measures.

Unlike the intestine, the role of microbes on the skin surface has not been well studied. An incomplete understanding of the fundamental biology of cutaneous microflora is the result of the limited research efforts to date. Existing clinical studies have provided invaluable information about the abundance and types of microbes on the skin, but fail to address their functions.11–15 In light of symbiotic relationships of microbial mutualism and commensalism demonstrated as critical to human health in studies of gut microbiota, a need exists to expand this research in skin.

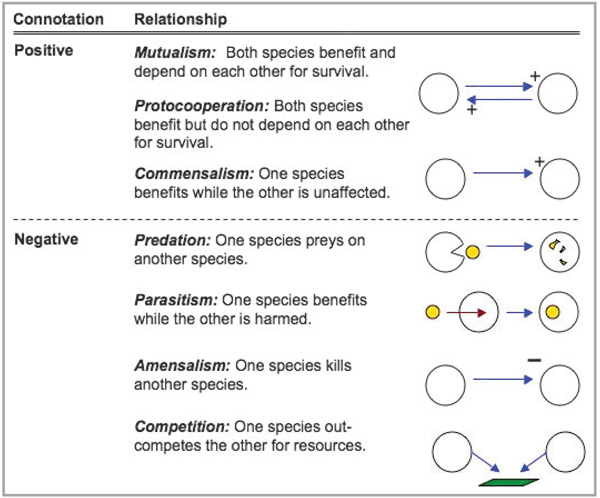

To begin this discussion it is helpful to outline the potential systems for symbiosis between skin flora and the host. These can fall into three categories: parasitism, commensalism or mutualism (Fig. 2). Commonly, a symbiotic relationship is understood to be one in which both organisms benefit each other. This perception is not correct. Symbiotic relationships can exist in which only one organism benefits while the other is harmed (parasitism, predation, ammensalism and competition), one organism benefits and no harm occurs to the other (commensalism) or both find benefit (mutualism and protoco-operation). Microbes found on the surface of the skin that are only very infrequently associated with disease are typically referred to as commensal. This term implies that the microbe lives in peaceful coexistence with the host while benefiting from the sheltered ecological niche. An example of such a microbe is the Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis. Emerging evidence to be discussed below indicates that this species and other so-called skin commensals may play an active role in host defence, such that they may represent, in fact, mutuals. One must recognize, however, that distinct categorizations such as parasitic, commensalistic or mutualistic may be oversimplified as the same microbe may take on different roles at different times. Understanding this premise, and the factors that dictate the type of microbe–host symbiosis, could lead to effective treatment and prevention strategies against skin infection.

Fig 2.

Types of symbiotic relationships.

It is also important to recognize that the distinction between what we consider to be harmless flora or a pathogenic agent often lies in the skin’s capacity to resist infection, and not the inherent properties of the microbe. Host cutaneous defence occurs through the combined action of a large variety of complementary systems. These include the physical barrier, a hostile surface pH, and the active synthesis of gene-encoded host defence molecules such as antimicrobial peptides, proteases, lysozymes and cytokines and chemokines that serve as activators of the cellular and adaptive immune responses. Virulence factors expressed by a microbe may enable it to avoid the host defence programme, but it is ultimately the sum effectiveness of this host response that determines if a microbe is a commensal (or mutual) organism or a dangerous pathogen for the host.

In the following review we focus on literature that describes the skin microbial flora. Although resident micro-flora on the skin include bacteria, viruses and many types of fungi, we will limit and focus the discussion by concentrating specifically on bacteria. The number of bacteria identified from human skin has expanded significantly, and will probably continue to increase as genotyping techniques advance.11,12 Some of the best-studied long-term and transient bacterial residents isolated from the skin include those from the genera Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Streptococcus and Pseudomonas (Table 1). Unfortunately, little is known about many of the other bacterial species on skin due to their low abundance and apparent harmlessness.11 Therefore, we will focus on those species best studied.

Table 1.

| Organism | Clinical isolate observations | Molecular detection |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Common, occasionally pathogenic | Frequent |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Infrequent, usually pathogenic | Frequent |

| Staphylococcus warneri | Infrequent, occasionally pathogenic | Occasional |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Infrequent, usually pathogenic | Occasional |

| Streptococcus mitis | Frequent, occasionally pathogenic | Frequent |

| Propionibacterium acnes | Frequent, occasionally pathogenic | Frequent |

| Corynebacterium spp. | Frequent, occasionally pathogenic | Frequent |

| Acinetobacter johnsonii | Frequent, occasionally pathogenic | Frequent |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Infrequent, occasionally pathogenic | Frequent |

Staphylococcus epidermidis

Staphylococcus epidermidis, the most common clinical isolate of the cutaneous microbiota, is a Gram-positive coccus found in clusters. As a major inhabitant of the skin and mucosa it is thought that S. epidermidis comprises greater than 90% of the aerobic resident flora. Small white or beige colonies (1–2 mm in diameter), desferrioxamine sensitivity, lack of trehalose production from acid and coagulase-negative characteristics easily distinguish S. epidermidis from other bacteria in the same genus.

Despite its generally innocuous nature, over the past 20 years S. epidermidis has emerged as a frequent cause of nosocomial infections. Several extrinsic factors contribute to the conversion of S. epidermidis from a member of the resident microflora to an infectious agent. The bacteria primarily infect compromised patients including drug abusers, those on immunosuppressive therapy, patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), premature neonates and patients with an indwelling device.16 The major ports of entry for these infections are foreign bodies such as catheters and implants.17 After entry, virulent strains of S. epidermidis form biofilms that partially shield the dividing bacteria from the host’s immune system and exogenous antibiotics. Once systemic, S. epidermidis can cause sepsis, native valve endocarditis, or other subacute or chronic conditions in the patient risk groups outlined above.18,19 A major complicating factor in the management of S. epidermidis blood infections is the inadequacy of many common antibiotic treatments. Biofilm formation reduces the access of antibiotics to the bacteria and often necessitates the removal of indwelling devices.20

In addition to catheter infections, patients with necrotic tumour masses from ulcerated advanced squamous cell carcinomas, head and neck carcinomas, breast carcinomas and sarcomas have a high propensity for infection by S. epidermidis. Also, myelosuppressive chemotherapy renders patients neutropenic, thereby increasing the risk of septicaemia. As abscesses infrequently form in neutropenic patients, S. epidermidis infections present as spreading cellulitis, associated with septicaemia.21 These specific skin infections caused by S. epidermidis require a predisposed host and do not reflect the typical bacteria–host interaction. In fact, S. epidermidis resides benignly, if not as a mutual on the skin’s surface, with infection arising only in conjunction with specific host predisposition.

Medical treatments for S. epidermidis infection range from systemic antibiotics to device modification and removal. Current research suggests that bacterial attachment to materials is dependent on the physicochemical properties of the bacterial and plastic surfaces.22–24 In particular, S. epidermidis has been shown to adhere to highly hydrophobic surfaces, while detergent-like substances and electric currents reduce attachment to the surfaces of the prosthetics or catheters.24,25 The autolysin protein AtlE, which possesses a vitronectin-binding domain, has been identified as a probable attachment factor. When the atlE gene is disrupted, the resulting S. epidermidis mutant exhibits reduced surface hydrophobicity and impaired attachment to a polystyrene surface.26 Other adhesion factors belong to the MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) family of surface-anchored proteins, including fibrinogen-binding protein Fbe.27,28 Other specific S. epidermidis proteins that may be involved in attachment to plastic-coated materials include Aas1, Aas2, SdrF and AAP (accumulation-associated protein).29,30

Increased virulence of S. epidermidis has also been attributed to a process known as intercellular adhesion (Fig. 3). Once the bacteria have gained entry, through a catheter for example, S. epidermidis produces factors responsible for growth, immune evasion and adhesion. In particular, polysaccharide intercellular adhesion (PIA) and poly-N-succinyl-glucosamine (PNSG), both encoded by the ica locus, mediate intercellular adhesion and have been implicated in virulence.31,32 Although these studies are very interesting, only a fraction of the S. epidermidis strains contains these genes, with the majority of the positive strains isolated from catheter infections and not from healthy skin.33 Other virulence factors are thought to be regulated by the agr (accessory gene regulator), sar and sigB loci. In a complex regulatory system, these three loci are involved in quorum-sensing and potentially biofilm (slime capsule) formation.22,34 The studies on the agr system, although fascinating, fail to address how the individual components under regulation, themselves affect virulence. In addition, the agr locus does not solely regulate virulence factors, but other genes involved in the bacterium’s physiology. The locus, also found in nonpathogenic staphylococci strains, has yet to be investigated under ‘mutual’ conditions on the skin’s surface. The understanding and inhibition of biofilms is of great interest and may increase the effectiveness of antibiotics against S. epidermidis catheter infections or sepsis. In addition, anti-PIA antibodies are being investigated in biofilm formation prevention.35 Interferon (IFN)-γ therapy, in addition to antibodies against specific S. epidermidis surface-binding proteins, has also proven effective in preventing catheter adhesion.36

Fig 3.

Staphylococci are pathogenic and mutualistic. (a) Virulence factors and molecules produced by staphylococci that aid in pathogenesis. (b) Staphylococci act mutually by inhibiting pathogens and priming the immune response. (c) Molecules from staphylococci that have dual functions.

Recent studies can be interpreted to suggest that S. epidermidis is a mutualistic organism, much like the bacteria of the gut. Many strains of S. epidermidis produce lantibiotics, which are lanthionine-containing antibacterial peptides, also known as bacteriocins (Fig. 3). Among the several identified bacteriocins are epidermin, epilancin K7, epilancin 15X, Pep5 and staphylococcin 1580.37–39 Additional antimicrobial peptides on the surface of the skin have recently been identified as originating from S. epidermidis.40 The identification of these peptides suggests the presence of intra- and interspecies competition, yet their direct regulatory, cytotoxic and mechanistic roles have yet to be addressed. Although S. epidermidis rarely damages the keratinocytes in the epidermis, the bacteria produce peptides toxic to other organisms, such as S. aureus and group A Streptococcus (GAS, S. pyogenes). The host epidermis permits S. epidermidis growth as the bacterium may provide an added level of protection against certain common pathogens, making the host–bacterium relationship one of mutualism. Protection afforded by S. epidermidis is further demonstrated in recent studies on pheromone cross-inhibition. The agr locus produces modified peptide pheromones, which subsequently affect the agr systems of various species by activating self and inhibiting nonself agr loci.41,42 The activation of agr signals to the bacterium that an appropriate density is reached and leads to a downregulation of virulence factors.43 Quorum-sensing decreases colonization-promoting factors and increases pheromones such as the phenol soluble modulin γ (δ-haemolysin, δ-toxin or δ-lysin).41 These pheromones affect the agr signalling of competing bacteria (such as S. aureus) and ultimately lead to colonization inhibition.42 Pheromones are being investigated for their therapeutic potential, such as δ-toxin, which reduces S. aureus attachment to polymer surfaces.44 In contrast, δ-toxin has also been labelled a virulence factor. Thus far, no studies have examined the consequences of eliminating δ-toxin production by targeted mutagenesis to prove conclusively the beneficial or detrimental effects of the peptide.

Staphylococcus epidermidis may also promote the integrity of cutaneous defence through elicitation of host immune responses. Our own preliminary data suggest that S. epidermidis plays an additional protective role by influencing the innate immune response of keratinocytes through Toll-like receptor (TLR) signalling (Fig. 3). TLRs are pattern-recognition receptors that specifically recognize molecules produced from pathogens collectively known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns. This education of the skin’s immune system may play an important role in defence against harmful pathogens. Through cellular ‘priming’, keratinocytes are able to respond more effectively and efficiently to pathogenic insults. New unpublished data suggest that S. epidermidis present on the skin amplifies the keratinocyte response to pathogens.

The removal of S. epidermidis (i.e. through overuse of topical antibiotics) may be detrimental to the host for two reasons. Firstly, removing S. epidermidis eliminates the bacterium’s endogenous antimicrobial peptides, allowing potentially pathogenic organisms to colonize the skin more effectively. Secondly, without bacterial priming of the skin, the host may be less efficient in warding off infection. In this light, S. epidermidis may be thought of as a mutual, thus, adding to the human innate immune system. Understanding this interaction may advance our knowledge of cutaneous diseases and infectious disease susceptibility.

Staphylococcus aureus

Characterized by circular, golden-yellow colonies, and β-haemolysis of blood agar, the coagulase-positive S. aureus is a leading human pathogen. Staphylococcus aureus clinical disease ranges from minor and self-limited skin infections to invasive and life-threatening diseases. Staphylococcus aureus skin infections include impetigo, folliculitis, furuncles and subcutaneous abscesses, and through the production of exfoliative toxins, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.45 The bacterium can also cause serious invasive infections such as septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, pneumonia, meningitis, septicaemia and endocarditis.45–47 Elaboration of superantigen toxins can trigger staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome.

Particular conditions predispose the skin to S. aureus infections, such as atopic dermatitis (AD). While viruses (e.g. herpes simplex type 1 virus and human papillomavirus) and fungi (e.g. Trichophyton rubrum) also opportunistically infect lesional and nonlesional AD skin, S. aureus is by far the most common superinfecting agent.48 Like S. epidermidis, S. aureus is a frequent cause of infection in catheterized patients.49

At present, S. aureus infections are treated with antibiotics and with the removal of infected implants as necessary.50 Unfortunately, there has been a dramatic rise in antibiotic-resistant strains, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in both hospital and community settings, and even documented reports of vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus strains (VISA and VRSA).46,51

The emergence of methicillin resistance is due to the acquisition of a transferable DNA element called staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec), a cassette (types I–V) carrying the mecA gene, encoding penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 2a.52–54 Through site-specific recombination, the DNA element integrates into the genome. Normally, β-lactam antibiotics bind to the PBPs in the cell wall, disrupt peptidoglycan layer synthesis and kill the bacterium. However, β-lactam antibiotics cannot bind to PBP2a, allowing a bacterium containing the mecA gene to survive β-lactam killing.54 Plasmids have also been found to confer Staphylococcus resistance to kanamycin, tobramycin, bleomycin, tetracycline and vancomycin.55,56

Staphylococcus aureus expresses many virulence factors, both secreted and cell surface associated, that contribute to evasion (Fig. 3). Staphylococcus aureus secretes the chemotaxis inhibitory protein of staphylococci (CHIPS) which binds to the formyl peptide receptor and C5a receptor on neutrophils, thereby interfering with neutrophil chemotaxis.57 Eap (also called major histocompatibility class II analogue protein Map) adheres to the intracellular adhesion molecule-1 on neutrophils, and prevents leucocyte adhesion and extravasation.58 Staphylococcus aureus also secretes an arsenal of toxins that damage host cells. Such toxins include superantigens (enterotoxins A–E, toxic shock syndrome toxin-1, ETA, B and D) and cytoxins [α-, β-, δ-, γ-haemolysin, Panton–Valentine leucocidin (PVL), leucocidin E–D, S. aureus exotoxin].45,46,59 Although PVL is epidemiologically associated with MRSA infections, its contribution to virulence is under dispute. Expression of PVL in a strain of S. aureus, previously not containing the toxin, increased virulence in a murine pneumonia model. Yet, the isogenic deletion of PVL in the MRSA clones USA300 and USA400 showed no reduction in virulence in other infection models. Extracellular enzymes secreted by S. aureus that may contribute to tissue damage include proteases, lipases, hyaluronidase and collagenase.46,60 Staphylococcus aureus α-haemolysis secretion leads to pore formation in target cell membranes and subsequent activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB inflammatory pathway.61

Staphylococcus aureus is relatively resistant to killing by cationic antimicrobial peptides produced by host epithelial cells and phagocytes. One key underlying mechanism for this resistance involves alterations in the charge of the bacterial cell surface. The Dlt protein causes d-alanine substitutions in the ribitol teichoic acids and lipoteichoic acids of the cell wall, slightly neutralizing the negatively charged cell surface to which cationic peptides usually bind.62,63 The MprF enyme adds l-lysine to phosphatidyl glycerol, similarly neutralizing the negatively charged cell surface.64 Mutants with defects in Dlt and MprF have been shown to be markedly more susceptible to human defensins.62,65 The staphylokinase of S. aureus binds and protects against defensins, while aureolysin cleaves human cathelicidin LL-37, offering further protection.66,67

Staphylococcus aureus resists phagocyte killing at a number of different levels. Effective opsonization of the bacterium is inhibited by the polysaccharide capsule, the surface expressed clumping factor and protein A. The eponymous golden carotenoid pigment protects S. aureus against neutrophil killing in vitro by scavenging oxygen free radicals.68

Despite the usual classification of S. aureus as a transient pathogen, it may be better considered a normal component of the nasal microflora.69,70 It is estimated that 86·9 million people (32·4% of the population) are colonized with S. aureus.71 Other studies have suggested that among the population, 20% are persistently colonized, 60% of the population intermittently carry the bacteria and 20% are never colonized.69 Colonization by S. aureus is certainly not synonymous with infection. Indeed, like S. epidermidis, healthy individuals rarely contract invasive infections caused by S. aureus.54 Staphylococcus aureus found on healthy human skin and in nasal passages are in effect acting as a commensal, rather than a pathogen. Certain strains of S. aureus have been shown to produce bacteriocins such as staphylococcin 462, a peptide responsible for growth inhibition of other S. aureus strains.72 Although the production of this bacteriocin probably aids in bacterial competition, further investigations, using mutagenesis and an in vivo model, would be helpful to illustrate the putative beneficial role of this organism. As S. aureus has generally been regarded as a pathogen, research has focused on its virulence factors, thereby minimizing studies about its role as an inhabitant of the normal flora.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

Coryneforms are Gram-positive, nonmotile, facultative anaerobic actinobacteria. These common members of the skin flora are divided into two species: C. diphtheriae and nondiphtheriae corynebacteria (diphtheroids). Corynebacterium diphtheriae is categorized by biotype: gravis, mitis, belfanti and intermedius, as defined by colony morphology and biochemical tests. Coryne-bacterium diphtheriae is further divided into toxigenic and non-toxigenic strains. Toxinogenic C. diphtheriae produce the highly lethal diphtheria toxin, which can induce fatal global toxaemia. Nontoxinogenic (nontoxin-producing) C. diphtheriae are capable of producing septicaemia, septic arthritis, endocarditis and osteomyelitis.73–75 Both nontoxigenic and toxigenic C. diphtheriae can be isolated from cutaneous ulcers of alcoholics, intravenous drug users and from hosts with poor hygiene standards, such as in endemic outbreaks in areas of low socio-economic status.76,77 Although immunization has successfully reduced the prevalence of diphtheria in most developed countries, the disease has surfaced in individuals impacted by socioeconomic deprivation, as well as nonimmunized and partially immunized individuals.78

Corynebacterium diphtheriae virulence is mainly attributed to diphtheria toxin, a 62-kDa exotoxin. The crystal structure shows a disulphide-linked dimer with a catalytic, transmembrane and receptor-binding domain.79 Invasion of the exotoxin is a complex series of events that involves translocation into the cytosol and results in halted protein synthesis.

Corynebacterium jeikeium

The nondiphtheriae corynebacteria, diphtheroids, are a diverse group, containing 17 different species, of which not all are present on human skin. Several species commonly colonize cattle, while others, such as C. jeikeium (formerly known as CDC group JK), are normal inhabitants of our epithelium. Although many diphtheroids are found on human skin, C. jeikeium is the most frequently recovered and medically relevant member of the group. In the last few years, Corynebacterium diphtheroids have gained interest due to the increasing number of publications on nosocomial infections. Corynebacterium jeikeium causes infections in immune-compromised patients, in conjunction with underlying malignancies, on implanted medical devices and in skin-barrier defects.80 In addition, C. jeikeium has been suggested as the cause of papular eruption with histological features of botryomycosis.81 Once the bacterium has penetrated the skin’s barrier, the bacterium can cause sepsis or endocarditis.82

Corynebacterium jeikeium treatment varies from other Gram-positive organisms because it is resistant to multiple antibiotics. However, it remains sensitive to glycopeptides including vancomycin or teicoplanin. Corynebacterium jeikeium antibiotic resistance stems from a variety of factors, ranging from the acquisition of antibiotic-resistant genes to the polyketide synthesis of FadD enzymes and subsequent corynomycolic acid in the cell envelope. Iron and manganese acquisition by C. jeikeium may contribute to virulence. Siderophores produced by the bacterium allow for efficient iron sequestration in the host. Manganese acquisition inhibits Mg-dependent superoxide dismutase, protecting the bacterium from superoxide production by the host or competing bacteria.83 There is much evidence that oxygen radicals produced by the host are a mechanism for defence against pathogens. In contrast, it has rarely been investigated whether or not production or scavenging of reactive oxygen species reflects interspecies competition for an ecological niche on the skin epithelium.

The C. jeikeium genome sequence also reveals numerous putative proteins with homology to adhesion and invasion factors from other Gram-positive pathogens.84 These include SurA and SurB (surface proteins similar to those of GAS and group B Streptococcus), Sap proteins (surface-anchored proteins that resemble C. diphtheriae factors used in pili formation), CbpA protein (belongs to the MSCRAMM family) and NanA protein (similar to neuraminidases from Streptococcus pneumoniae).85–88

Corynebacterium jeikeium is considered part of the normal skin flora, similar to S. epidermidis. This bacterium species resides on the skin of most humans and is commonly cultured from hospitalized patients.80,89 In particular, colonization is seen in axillary, inguinal and perineal areas.90 Almost all infections caused by C. jeikeium are nosocomial and occur in patients with pre-existing ailments. As with S. epidermidis, C. jeikeium is ubiquitous and largely innocuous, illustrating that the bacterium is commensal. In fact, C. jeikeium may offer epidermal protection, bolstering the argument that cutaneous microflora are mutualistic. Manganese acquisition effectively allows the bacteria to safeguard themselves from superoxide radicals. The enzyme superoxide dismutase may also function to prevent oxidative damage to epidermal tissue, a potential means by which bacteria protect the host. Moreover, iron and manganese are critical for organism survival, both pathogenic and nonpathogenic. The act of scavenging these elements may prevent colonization by other microbes. Finally, C. jeikeium produces bacteriocin-like compounds used to ward off potential pathogens and competitors. Lacticidin Q produced by Lactococcus lactis has a 66% homology to AucA, a hypothetical protein encoded in the C. jeikeium plasmid pA501.91 AucA has yet to be investigated for its bacteriocin activity both in vivo and in vitro. Most likely, C. jeikeium produces other bacteriocins not yet identified. As the study of virulence factors dominates the fields of micro-biology and infectious disease, little is known about the potential mutualism of C. jeikeium. Given the prevalence of skin colonization, the relative rarity of C. jeikeium pathogenesis and the yet unexplored benefits of the bacterium, C. jeikeium probably lives mutually on the skin.

Propionibacterium acnes

Commonly touted as the cause of acne vulgaris, P. acnes is an aerotolerant anaerobic, Gram-positive bacillus that produces propionic acid, as a metabolic byproduct. This bacterium resides in the sebaceous glands, derives energy from the fatty acids of the sebum, and is susceptible to ultraviolet radiation due to the presence of endogenous porphyrins.92

Propionibacterium acnes is implicated in a variety of manifestations such as folliculitis, sarcoidosis and systemic infections resulting in endocarditis.93,94 Occasionally, P. acnes causes SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis), a chronic, inflammatory, systemic infection.95 In the sebaceous gland, P. acnes produces free fatty acids as a result of triglyceride metabolism. These byproducts can irritate the follicular wall and induce inflammation through neutro-phil chemotaxis to the site of residence.96 Inflammation due to host tissue damage or production of immunogenic factors by P. acnes subsequently leads to cutaneous infections (Fig. 4).97,98

Fig 4.

Hypothetical model for relationship between Propionibacterium acnes and pustule formation. The graph depicts pustule formation and P. acnes growth over time. In phase 1, P. acnes is present, but comedones are not. In phase 2, comedo formation begins, independently of P. acnes growth; P. acnes begins to proliferate only after comedo forms. In phase 3, P. acnes proliferates in trapped comedo. In phase 4, P. acnes is killed by an inflammatory response. Disease and pustule formation is maximal despite eradication of P. acnes. This model illustrates that acne formation is not triggered by the ubiquitous and resident P. acnes and at the maximal disease stage, P. acnes has already been eliminated.

The most well-known ailment associated with P. acnes is the skin condition known as acne vulgaris, affecting up to 80% of adolescents in the U.S.A.99 Several factors are thought to contribute to an individual’s susceptibility. Androgens, medications (including steroids and oral contraceptives), the keratinization pattern of the hair follicle, stress and genetic factors all contribute to acne predisposition.100,101 Clinically, patients present with distended, inflamed or scarred pilosebaceous units. Noninflammatory acne lesions form either open or closed comedones, while inflammatory acne lesions develop into papules, pustules, nodules or cysts.

Like S. epidermidis, P. acnes causes many postoperative infections. Prosthetic joints, catheters and heart valves transport the cutaneous microflora into the body.102 Sepsis and endocarditis result from systemic infections.103 Another common port of entry for P. acnes is through ocular injury or operation. Propioni-bacterium acnes causes endophthalmitis (inflammation of the interior of the eye causing blindness) weeks or months after trauma or eye surgery. The infection delay probably results from the low-virulence phenotype of P. acnes.104

Treatment for P. acnes infections varies depending on the presentation of disease. For acne, various medications and prevention strategies are currently employed. Benzoyl peroxide and topical antibiotics are bactericidal and bacteriostatic, respectively, against P. acnes infections. Topical retinoids such as tretinoin and adapalene reduce inflammation of follicular keratinocytes and may interfere with TLR2 and P. acnes interactions.105 A regimen of oral antibiotics is given to individuals with moderate acne. In addition to reducing the number of P. acnes on the skin, antibiotics provide an anti-inflammatory effect.106 Oral isotretinoin, a compound related to retinol (vitamin A), is currently the only treatment that leads to permanent remission.107 The cutaneous effects of isotretinoin and other vitamin A derivatives are currently being researched. Rare systemic infections, including endocarditis, which can develop postoperatively or in immune-compromised patients, have been treated effectively with penicillin or vancomycin.108–110

Proposed P. acnes virulence factors include enzymes that aid in adherence and colonization of the follicle. In particular, hyaluronate lyase degrades hyaluronan in the extracellular matrix, potentially contributing to adherence and invasion.111 The genome of P. acnes also encodes sialidases and endoglyco-ceramidases putatively involved in host tissue degradation.99 Propionibacterium acnes also produces biofilms, limiting antibiotic access to the site of infection.96

Studies have shown that TLRs play an important role in inflammation associated with P. acnes infection. Propionibacterium acnes induces expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in keratinocytes,112 and the bacterium can induce interleukin (IL)-6 release from TLR1−/−, TLR6−/− and wild-type murine macrophages but not from TLR2−/− murine macrophages.113 These combined data show that P. acnes interacts with TLR2 to induce cell activation. Propionibacterium acnes infection also stimulates production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-8 (involved in neutrophil chemotaxis), tumour necrosis factor-α, IL-1β and IL-12.114,115

The major factors contributing to acne are the hypercornification of the outer root sheath and the pilosebaceous duct, increased sebum production and, potentially, the overgrowth of P. acnes. Some have suggested that P. acnes involvement in inflammation is relatively minor and the abnormal bacterial growth in the sebaceous ducts may be a side-effect of inflammation rather than a root cause (Fig. 4). Although the bacterium is commonly associated with acne pathogenesis, healthy and acne-prone patients alike are colonized.11 Studies have also shown that antibiotics primarily reduce inflammation and only secondarily inhibit P. acnes growth.106 These data suggest that P. acnes has a low pathogenic potential with a minor role in the development of acne. The prevalence of P. acnes on healthy skin suggests a relationship of commensalism or mutualism rather than parasitism.

Together, the avirulence of P. acnes and the studies showing a beneficial effect on the host suggest that the bacterium is a mutual. In one study, mice, immunized with heat-killed P. acnes and subsequently challenged with lipopolysaccharides, showed increased TLR4 sensitivity and MD-2 upregulation.116 The authors suggested that the hyperelevated cytokine levels indicated a detrimental effect by P. acnes in vivo. The data, although interesting, do not identify the P. acnes molecule associated with the effect. Alternatively, the data may suggest that P. acnes enables host cells to respond effectively to a pathogenic insult, in which case P. acnes would serve a protective role. It is probable that a similar response could be seen with injections of other types of bacteria but these results serve to highlight a potential mechanism for mutualism. Propionibacteria have also been shown to produce bacteriocins or bacteriocin-like compounds. These include propionicin PLG-1, jenseniin G, propionicin SM1, SM2, T1117,118 and acnecin,119 with activity against several strains of propionibacteria, several lactic acid bacteria, some Gram-negative bacteria, yeasts and moulds. Little is known about the production or role of bacteriocins in P. acnes oral or cutaneous survival. These bacteriocins may potentially secure the pilosebaceous niche and protect the duct from other pathogenic inhabitants. By depleting P. acnes through antibiotic use, the host could theoretically increase susceptibility to infection by pathogens. The supply of nutrient-rich sebum in exchange for protection against other microbes may be one mechanism by which P. acnes acts mutualistically.

Group A Streptococcus (S. pyogenes)

Known for causing superficial infections as well as invasive diseases, GAS forms chains of Gram-positive cocci. The bacterium is β-haemolytic on blood agar and catalase-negative. GAS strains are further subclassified by their M-protein and T-antigen serotype.

The types of M protein and T antigen expressed indicate the strain’s potential to cause superficial or invasive disease. GAS infections are diverse in their presentation, with ‘strep throat’, a mucosal infection and impetigo of the skin being most common. Superficial GAS infections differ with age and cutaneous morphology. Nonbullous impetigo (pyoderma) prevails in infants and children. The postinfectious nonpyogenic syndrome rheumatic fever can follow throat infection and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis can follow either skin or throat infection.120 GAS is also associated with deeper-seated skin infections such as cellulitis and erysipelas, infections of connective tissue and underlying adipose tissue, respectively. These types of disease occur frequently in the elderly and in individuals residing in densely populated areas.121 Bacterial infections generally occur in association with diabetes, alcoholism, immune deficiency, skin ulcers and trauma. The invasive necrotizing fasciitis, or ‘flesh-eating’ disease, carries a high degree of morbidity and mortality and is frequently complicated by streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. GAS can also cause infections in many other organs including lung, bone and joint, muscle and heart valve, essentially mimicking the disease spectrum of S. aureus.

GAS disease treatment depends on location, severity and type of infection. Superficial infections such as impetigo are easily eradicated with topical antibacterial ointments such as mupirocin (Bactroban®) or fusidic acid (Fucidin®). More extensive skin infections are treated with oral antibiotics such as penicillin, erythromycin or clindamycin.122 Invasive infections require systemic antibiotics and intensive support; surgical debridement of devitalized tissue is critical to management of necrotizing fasciitis.123

For the most part, GAS is sensitive to β-lactams (penicillin), but in severe infections the antibiotic fails due to the large inoculum of bacteria and the ability of GAS to downregulate PBPs during stationary growth phase.124 In severe systemic infections, adjunctive therapy with intravenous gammaglobulin may provide neutralizing antibodies against streptococcal superantigens to prevent development of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.125

GAS is capable of subverting the host immune response in a variety of ways. Inhibiting phagocyte recruitment, GAS expresses the proteases ScpC or SpyCEP, that cleave and inactivate the neutrophil chemokine IL-8.126,127 GAS also produces a C5a peptidase that cleaves and inactivates this chemoattractant byproduct of the host complement cascade.128,129 Invasive strains of GAS produce DNases (also known as streptodornases) that degrade the chromatin-based neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) employed by the host innate immune system to ensnare circulating bacteria.130,131 Targeted mutagenesis revealed that DNase Sda I promotes GAS NET degradation and neutrophil-killing resistance both in vivo and in vitro. Hyaluronidase, secreted by GAS, allows for bacterial migration through the host extracellular matrix.132 The surface-expressed streptokinase sequesters and activates host plasminogen on the bacterial surface, effectively coating the bacteria with plasmin that promotes tissue spread. The pore-forming toxins streptolysin O (SLO) and streptolysin S are broadly cytolytic against host cells including phagocytes, as shown through targeted mutagenesis. A variety of streptococcal superantigens, e.g. SpeA, SpeC and SmeZ, can promote rapid clonal T-cell expansion and trigger toxic shock-like syndrome.133 GAS causes disease in compromised and healthy individuals alike, illustrative of a parasitic symbiosis between GAS and the host.

Potential host benefits of GAS may be deciphered in certain interactions of GAS with host epithelium. For example, several studies have shown that SLO promotes wound healing in vitro through stimulating keratinocyte migration.134 Sublytic concentrations of SLO may induce CD44 expression, potentially modulating collagen, hyaluronate and other extracellular matrix components in mouse skin. Both the tight skin mouse (Tsk) model of scleroderma and the bleomycin-induced mouse skin fibrosis model showed decreased levels of hydroxyproline after treatment with SLO.135

Plasminogen activation in the epidermis leads to keratinocyte chemotaxis, suppression of cell proliferation, and potential re-epithelialization of wounds.136 Also, streptokinase is now being used clinically for therapeutic fibrinolysis.137,138 Thus, in a tissue-specific context, limited expression of certain GAS virulence factors may aid rather than harm the host.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

This Gram-negative, rod shaped, aerobic bacterium is well known for its ability to produce fluorescent molecules, including pyocyanin (blue-green), pyoverdin or fluorescein (yellow-green) and pyorubin (red-brown). Fluorescence and the grape-like sweet odour allow for easy identification of P. aeruginosa from other Gram-negative bacteria.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is commonly found in nonsterile areas on healthy individuals and, much like S. epidermidis, is considered a normal constituent of a human’s natural microflora. The bacteria normally live innocuously on human skin and in the mouth, but are able to infect practically any tissue with which they come into contact. Flexible, nonstringent metabolic requirements allow P. aeruginosa to occupy a variety of niches, making it the epitome of an opportunistic pathogen. Due to the general harmlessness of the bacteria, infections occur primarily in compromised patients and in conjunction with hospital stays. Explicitly, immune-compromised individuals with AIDS, cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, neutropenia, and haematological and malignant diseases develop systemic or localized P. aeruginosa infections. Transmission often occurs through contamination of inanimate objects and can result in ventilator-associated pneumonia and other device-related infections.

The main port of entry is through compromised skin, with burn victims commonly suffering from P. aeruginosa infections. Entry into the blood results in bone, joint, gastrointestinal, respiratory and systemic infections. On the skin, P. aeruginosa occasionally causes dermatitis or deeper soft-tissue infections. Dermatitis occurs when skin comes into contact with infected water, often in hot tubs. The infection is very mild and is treated easily with topical antibiotics. Severe infections are treated with injectable antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides (gentamicin), quinolones, cephalosporins, ureidopenicillins, carbapenems, polymyxins and monobactams, although multi-drug resistance is increasingly common in hospital settings and in chronically infected individuals (e.g. patients with cystic fibrosis).

During infection, the type IV pilus and nonpilus adhesins anchor the bacteria to the tissue. Pseudomonas aeruginosa secretes alginate (extracellular fibrous polysaccharide matrix), protecting the bacterium from phagocytic killing and potentially from antibiotic access.139 Postmortem lung material from P. aeruginosa-infected cystic fibrosis patients showed the bacterial cells in distinct fibre-enclosed microcolonies. Pseudomonas aeruginosa also produces a variety of toxins and enzymes including lipopolysaccharide, elastase, alkaline protease, phospholipase C, rhamnolipids and exotoxin A, to which the host produces antibodies.140 The regulation of these virulence factors is very complex and is modulated by the host’s response. The role of many of these antigens in host immunity is incompletely understood. Also, the contribution of many of the toxins to bacterial virulence remains controversial, with toxin-lacking strains still exhibiting virulence in murine models of infection.140 It was found that P. aeruginosa is able to sense the immune response and upregulate the virulence factor type I lectin (lecA).141 IFN-γ binds to the major outer-membrane protein OprF and the OprF–IFN-γ interaction induces the bacteria to express lectin and quorum-sensing related (bacterial communication system) virulence factors.141,142 Many genes that encode porins and other virulence factors are also being studied in relation to quorum sensing and P. aeruginosa metabolism.

The medical significance of P. aeruginosa infections is heightened due to antibiotic resistance. Pseudomonas aeruginosa expresses genes that encode enzymes which hydrolyse specific antibiotics. Specifically, the bacteria produce AmpC cephalosporinase, β-lactamases (PSE, OXA, TEM, SHV and other class-A type) and metallo-carbapenemases.143 Antibiotic resistance also results from mutations in the porin OMP, which normally encodes the D2 porin, OprD.144 Subsequent inactivation of OprD leads to imipenem resistance. Aminoglycoside resistance due to a variety of mechanisms occurs through acquisition of gene-resistance cassettes occasionally present in integrons simultaneously encoding metallo-β-lactamases.145 Other antibiotic-resistant mechanisms are attributed to upregulation of efflux pumps, such as the MexAB–OprM system, and to mutations in topoisomerases II and IV.146,147

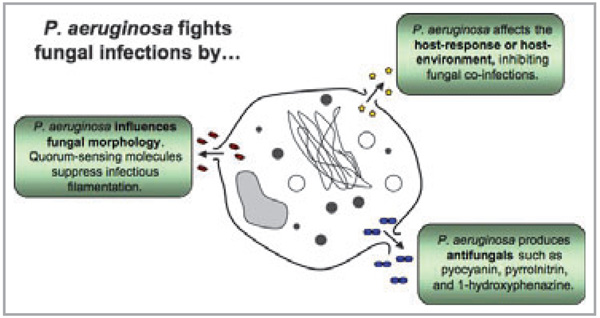

Despite intermittent disease caused by P. aeruginosa, the bacteria have been shown to protect the human host from a variety of infections. The byproducts of Pseudomonas are so potent that several have been turned into commercial medications. One of the most well-known products of a Pseudomonas (particularly P. fluorescens) is pseudomonic acid A, also called mupirocin or Bactroban®.148 Mupirocin is one of the only topical antibiotics used in treatment of topical infections caused by staphylococcal and streptococcal pathogens. Staphylococcus aureus with resistance to multiple antibiotics often shows sensitivity to mupirocin. Pseudomonas aeruginosa also produces compounds with similar antimicrobial activity. A peptide called PsVP-10, produced by P. aeruginosa, was shown to have antibacterial activity against Streptococcus mutans and S. sobrinus.149 In addition, P. aeruginosa suppresses fungal growth (Fig. 5). Fungal species that the bacteria fully or partially inhibit include Candida krusei, C. keyfr, C. guilliermondii, C. tropicalis, C. lusitaniae, C. parapsilosis, C. pseudotropicalis, C. albicans, Torulopsis glabrata, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Aspergillus fumigatus.150 Studies have shown that P. aeruginosa and C. albicans coexist in the host and the attenuation of P. aeruginosa results in C. albicans growth. The mechanism by which P. aeruginosa inhibits C. albicans may be due to the quorum-sensing molecule 3-oxo-C12 homoserine lactone (3OC12HSL).151 This and other molecules, such as 1-hydroxyphenazine or pyocyanin, are shown to suppress the filamentous, or virulent, phase of C. albicans growth (Fig. 5). Although in vitro data show inhibition by both molecules, future targeted mutagenesis will be required to show conclusively the relevance of these compounds in cross-inhibition.152 The presence of P. aeruginosa probably attenuates C. albicans and possibly other yeasts, thereby preventing infection. The repression of microbial growth by P. aeruginosa is not restricted to yeasts, and inhibition is also seen with Helicobacter pylori.153

Fig 5.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa fights fungal infections. It produces compounds such as pyocyanin, pyrrolnitrin and 1-hydroxyphenazine which kill and inhibit fungal growth. Pseudomonas aeruginosa also prevents the morphological transition of fungi from yeast-form cells to virulent filamentous cells. Filamentation of Candida albicans is associated with pathogenesis, adhesion, invasion and virulence-related products. Pseudomonas aeruginosa interacts with the host creating an environment inhospitable to fungi.

The obvious benefit of P. aeruginosa leads toward the classification of this microbe as a mutual. The rarity of P. aeruginosa-related disease and the impedance of pathogenic organisms suggest that this bacterium maintains homeostasis between host and microbe, preventing disease. The antifungal activity of phenazines may explain the rarity of yeast infections in cystic fibrosis patients. In the same vein, removing P. aeruginosa from the skin, through use of oral or topical antibiotics, may inversely allow for aberrant yeast colonization and infection. Thus, the bacterium’s ubiquitous presence could contribute against colonization by more pathogenic organisms, effectively making P. aeruginosa a participant in the host’s cutaneous innate immune system.

Conclusions

Current research related to infectious diseases of the skin targets microbial virulence factors and aims to eliminate harmful organisms. Some of these same microbes potentially also play an opposite role by protecting the host. The complex host– microbe and microbe–microbe interactions that exist on the surface of human skin illustrate that the microbiota have a beneficial role, much like that of the gut microflora. Microbes participate in inflammatory diseases yet may not cause infections. For the clinician, understanding these principles should guide appropriate use of currently available systemic and topical antibiotics. An overuse of antibiotics may disrupt the delicate balance of the cutaneous microflora leaving the skin susceptible to pathogens previously kept at bay by the existing resident and mutual microbiota. Further advances in our understanding of microbial pathogens as well as an increase in the appreciation of the complex relationship that humans have with the resident microbes promise to lead to novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to dermatological disease.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Tanaka K, Sawamura S, Satoh T, et al. Role of the indigenous microbiota in maintaining the virus-specific CD8 memory T cells in the lung of mice infected with murine cytomegalovirus. J Immunol. 2007;178:5209–5216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ewaschuk JB, Tejpar QZ, Soo I, et al. The role of antibiotic and probiotic therapies in current and future management of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:486–498. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0039-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rinne M, Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, et al. Probiotic intervention in the first months of life: short-term effects on gastrointestinal symptoms and long-term effects on gut microbiota. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:200–205. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000228106.91240.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noverr MC, Huffnagle GB. The ‘microflora hypothesis’ of allergic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1511–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauch UG, Obermeier F, Grunwald N, et al. Influence of intestinal bacteria on induction of regulatory T cells: lessons from a transfer model of colitis. Gut. 2005;54:1546–1552. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.059451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coconnier MH, Lievin V, Lorrot M, et al. Antagonistic activity of Lactobacillus acidophilus LB against intracellular Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium infecting human enterocyte-like Caco-2/TC-7 cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1152–1157. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.1152-1157.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coconnier MH, Lievin V, Bernet-Camard MF, et al. Antibacterial effect of the adhering human Lactobacillus acidophilus strain LB. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1046–1052. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernet MF, Brassart D, Neeser JR, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus LA 1 binds to cultured human intestinal cell lines and inhibits cell attachment and cell invasion by enterovirulent bacteria. Gut. 1994;35:483–489. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Leu RK, Brown IL, Hu Y, et al. A symbiotic combination of resistant starch and Bifidobacterium lactis facilitates apoptotic deletion of carcinogen-damaged cells in rat colon. J Nutr. 2005;135:996–1001. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.5.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokesova A, Frolova L, Kverka M, et al. Oral administration of pro-biotic bacteria (E. coli Nissle, E. coli O83, Lactobacillus casei) influences the severity of dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in BALB/c mice. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2006;51:478–484. doi: 10.1007/BF02931595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao Z, Tseng CH, Pei Z, et al. Molecular analysis of human forearm superficial skin bacterial biota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607077104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dekio I, Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, et al. Detection of potentially novel bacterial components of the human skin microbiota using culture-independent molecular profiling. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:1231–1238. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredricks DN. Microbial ecology of human skin in health and disease. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2001;6:167–169. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadaway LC. Skin flora and infection. J Infus Nurs. 2003;26:44–48. doi: 10.1097/00129804-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth RR, James WD. Microbiology of the skin: resident flora, ecology, infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:367–390. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domingo P, Fontanet A. Management of complications associated with totally implantable ports in patients with AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2001;15:7–13. doi: 10.1089/108729101460056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tacconelli E, Tumbarello M, Pittiruti M, et al. Central venous catheter-related sepsis in a cohort of 366 hospitalised patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:203–209. doi: 10.1007/BF01709582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caputo GM, Archer GL, Calderwood SB, et al. Native valve endocarditis due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clinical and micro-biologic features. Am J Med. 1987;83:619–625. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90889-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overturf GD, Sherman MP, Scheifele DW, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis associated with delta toxin-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:88–91. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199002000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoyle BD, Costerton JW. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics: the role of biofilms. Prog Drug Res. 1991;37:91–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7139-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitlik S, Fainstein V. Cellulitis caused by Staphylococcus epidermidis in a patient with leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1099–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerca N, Pier GB, Vilanova M, et al. Quantitative analysis of adhesion and biofilm formation on hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Res Microbiol. 2005;156:506–414. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Mei HC, van de Belt-Gritter B, Reid G, et al. Adhesion of coagulase-negative staphylococci grouped according to physico-chemical surface properties. Microbiology. 1997;143:3861–3870. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vacheethasanee K, Marchant RE. Surfactant polymers designed to suppress bacterial (Staphylococcus epidermidis) adhesion on biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:302–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(20000605)50:3<302::aid-jbm3>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Borden AJ, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Electric block current induced detachment from surgical stainless steel and decreased viability of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6731–6735. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heilmann C, Hussain M, Peters G, et al. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1013–1024. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4101774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams RJ, Henderson B, Sharp LJ, et al. Identification of a fibronectin-binding protein from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6805–6810. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6805-6810.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson M, Frykberg L, Flock JI, et al. A fibrinogen-binding protein of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2666–2673. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2666-2673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCrea KW, Hartford O, Davis S, et al. The serine-aspartate repeat (Sdr) protein family in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiology. 2000;146:1535–1546. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-7-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hussain M, Herrmann M, von Eiff C, et al. A 140-kilodalton extra-cellular protein is essential for the accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains on surfaces. Infect Immun. 1997;65:519–524. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.519-524.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Xu L, Wang J, et al. Conversion of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains from commensal to invasive by expression of the ica locus encoding production of biofilm exopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3188–3191. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3188-3191.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKenney D, Pouliot K, Wang Y, et al. Vaccine potential of poly-1-6 beta-D-N-succinylglucosamine, an immunoprotective surface polysaccharide of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Biotechnol. 2000;83:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(00)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang YQ, Ren SX, Li HL, et al. Genome-based analysis of virulence genes in a non-biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis strain (ATCC 12228) Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1577–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tao JH, Fan CS, Gao SE, et al. Depression of biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance by sarA disruption in Staphylococcus epidermidis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4009–4013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun D, Accavitti MA, Bryers JD. Inhibition of biofilm formation by monoclonal antibodies against Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A accumulation-associated protein. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:93–100. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.1.93-100.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boelens JJ, van der Poll T, Dankert J, et al. Interferon-gamma protects against biomaterial-associated Staphylococcus epidermidis infection in mice. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1167–1171. doi: 10.1086/315344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bierbaum G, Gotz F, Peschel A, et al. The biosynthesis of the lantibiotics epidermin, gallidermin, Pep5 and epilancin K7. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:119–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00399417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekkelenkamp MB, Hanssen M, Danny Hsu ST, et al. Isolation and structural characterization of epilancin 15X, a novel lantibiotic from a clinical strain of Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1917–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahl HG. Staphylococcin 1580 is identical to the lantibiotic epidermin: implications for the nature of bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:752–755. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.752-755.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cogen AL, Nizet V, Gallo RL. Staphylococcus epidermidis functions as a component of the skin innate immune system by inhibiting the pathogen Group A Streptococcus. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:S131. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otto M. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis peptide pheromones produced by the accessory gene regulator agr system. Peptides. 2001;22:1603–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otto M, Echner H, Voelter W, et al. Pheromone cross-inhibition between Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1957–1960. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1957-1960.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otto M, Sussmuth R, Vuong C, et al. Inhibition of virulence factor expression in Staphylococcus aureus by the Staphylococcus epidermidis agr pheromone and derivatives. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vuong C, Saenz HL, Gotz F, et al. Impact of the agr quorum-sensing system on adherence to polystyrene in Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1688–1693. doi: 10.1086/317606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwatsuki K, Yamasaki O, Morizane S, et al. Staphylococcal cutaneous infections: invasion, evasion and aggression. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;42:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foster TJ. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:948–958. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker BS. The role of microorganisms in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sadoyma G, Diogo Filho A, Gontijo Filho PP. Central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus: microbiology and risk factors. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10:100–106. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702006000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viale P, Stefani S. Vascular catheter-associated infections: a micro-biological and therapeutic update. J Chemother. 2006;18:235–249. doi: 10.1179/joc.2006.18.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hiramatsu K. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma XX, Ito T, Tiensasitorn C, et al. Novel type of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec identified in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1147–1152. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.1147-1152.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiramatsu K, Cui L, Kuroda M, et al. The emergence and evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:486–493. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foster TJ. The Staphylococcus aureus ‘superbug’. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1693–1696. doi: 10.1172/JCI23825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deurenberg RH, Vink C, Kalenic S, et al. The molecular evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:222–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weigel LM, Clewell DB, Gill SR, et al. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;302:1569–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Haas CJ, Veldkamp KE, Peschel A, et al. Chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterial antiinflammatory agent. J Exp Med. 2004;199:687–695. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chavakis T, Hussain M, Kanse SM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus extra-cellular adherence protein serves as anti-inflammatory factor by inhibiting the recruitment of host leukocytes. Nat Med. 2002;8:687–693. doi: 10.1038/nm728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cribier B, Prevost G, Couppie P, et al. Staphylococcus aureus leukocidin: a new virulence factor in cutaneous infections? An epidemiological and experimental study. Dermatology. 1992;185:175–180. doi: 10.1159/000247443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyon GJ, Novick RP. Peptide signaling in Staphylococcus aureus and other Gram-positive bacteria. Peptides. 2004;25:1389–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dragneva Y, Anuradha CD, Valeva A, et al. Subcytocidal attack by staphylococcal alpha-toxin activates NF-kappaB and induces inter-leukin-8 production. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2630–2635. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2630-2635.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peschel A, Otto M, Jack RW, et al. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8405–8410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collins LV, Kristian SA, Weidenmaier C, et al. Staphylococcus aureus strains lacking D-alanine modifications of teichoic acids are highly susceptible to human neutrophil killing and are virulence attenuated in mice. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:214–219. doi: 10.1086/341454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oku Y, Kurokawa K, Ichihashi N, et al. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus mprF gene, involved in lysinylation of phosphatidylglycerol. Microbiology. 2004;150:45–51. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26706-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peschel A, Jack RW, Otto M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to human defensins and evasion of neutrophil killing via the novel virulence factor MprF is based on modification of membrane lipids with l-lysine. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1067–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin T, Bokarewa M, Foster T, et al. Staphylococcus aureus resists human defensins by production of staphylokinase, a novel bacterial evasion mechanism. J Immunol. 2004;172:1169–1176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sieprawska-Lupa M, Mydel P, Krawczyk K, et al. Degradation of human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by Staphylococcus aureus-derived proteinases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4673–4679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4673-4679.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu GY, Essex A, Buchanan JT, et al. Staphylococcus aureus golden pigment impairs neutrophil killing and promotes virulence through its antioxidant activity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:209–215. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peacock SJ, de Silva I, Lowy FD. What determines nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus? Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:605–610. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, et al. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mainous AG, III, Hueston WJ, Everett CJ, et al. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus in the United States, 2001–2002. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:132–137. doi: 10.1370/afm.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hale EM, Hinsdill RD. Biological activity of staphylococcin 162: bacteriocin from Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1975;7:74–81. doi: 10.1128/aac.7.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Austin GE, Hill EO. Endocarditis due to Corynebacterium CDC group G2. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:1106. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.6.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barakett V, Morel G, Lesage D, et al. Septic arthritis due to a non-toxigenic strain of Corynebacterium diphtheriae subspecies mitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:520–521. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Poilane I, Fawaz F, Nathanson M, et al. Corynebacterium diphtheriae osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent child: a case report. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:381–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02072108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harnisch JP, Tronca E, Nolan CM, et al. Diphtheria among alcoholic urban adults. A decade of experience in Seattle. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:71–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-1-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coyle MB, Groman NB, Russell JQ, et al. The molecular epidemiology of three biotypes of Corynebacterium diphtheriae in the Seattle outbreak, 1972–1982. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:670–679. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Prospero E, Raffo M, Bagnoli M, et al. Diphtheria: epidemiological update and review of prevention and control strategies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:527–534. doi: 10.1023/a:1007305205763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choe S, Bennett MJ, Fujii G, et al. The crystal structure of diphtheria toxin. Nature. 1992;357:216–222. doi: 10.1038/357216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coyle MB, Lipsky BA. Coryneform bacteria in infectious diseases: clinical and laboratory aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:227–246. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jucgla A, Sais G, Carratala J, et al. A papular eruption secondary to infection with Corynebacterium jeikeium, with histopathological features mimicking botryomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:801–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van der Lelie H, Leverstein-Van Hall M, Mertens M, et al. Corynebacterium CDC group JK (Corynebacterium jeikeium) sepsis in haematological patients: a report of three cases and a systematic literature review. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:581–584. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Storz G, Imlay JA. Oxidative stress. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tauch A, Kaiser O, Hain T, et al. Complete genome sequence and analysis of the multiresistant nosocomial pathogen Corynebacterium jeikeium K411, a lipid-requiring bacterium of the human skin flora. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4671–4682. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4671-4682.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stalhammar-Carlemalm M, Areschoug T, Larsson C, et al. The R28 protein of Streptococcus pyogenes is related to several group B streptococcal surface proteins, confers protective immunity and promotes binding to human epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:208–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ton-That H, Schneewind O. Assembly of pili in Gram-positive bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Joh D, Wann ER, Kreikemeyer B, et al. Role of fibronectin-binding MSCRAMMs in bacterial adherence and entry into mammalian cells. Matrix Biol. 1999;18:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(99)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Camara M, Boulnois GJ, Andrew PW, et al. A neuraminidase from Streptococcus pneumoniae has the features of a surface protein. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3688–3695. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3688-3695.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Larson EL, McGinley KJ, Leyden JJ, et al. Skin colonization with antibiotic-resistant (JK group) and antibiotic-sensitive lipophilic diphtheroids in hospitalized and normal adults. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:701–706. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wichmann S, Wirsing von Koenig CH, Becker-Boost E, et al. Group JK corynebacteria in skin flora of healthy persons and patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1985;4:502–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02014433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fujita K, Ichimasa S, Zendo T, et al. Structural analysis and characterization of lacticin Q, a novel bacteriocin belonging to a new family of unmodified bacteriocins of Gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:2871–2877. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02286-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ashkenazi H, Malik Z, Harth Y, et al. Eradication of Propionibacterium acnes by its endogenic porphyrins after illumination with high intensity blue light. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;35:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2003.tb00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jakab E, Zbinden R, Gubler J, et al. Severe infections caused by Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated pathogen in late postoperative infections. Yale J Biol Med. 1996;69:477–482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Homma JY, Abe C, Chosa H, et al. Bacteriological investigation on biopsy specimens from patients with sarcoidosis. Jpn J Exp Med. 1978;48:251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kotilainen P, Merilahti-Palo R, Lehtonen OP, et al. Propionibacterium acnes isolated from sternal osteitis in a patient with SAPHO syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1302–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Coenye T, Peeters E, Nelis HJ. Biofilm formation by Propionibacterium acnes is associated with increased resistance to antimicrobial agents and increased production of putative virulence factors. Res Microbiol. 2007;158:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Miskin JE, Farrell AM, Cunliffe WJ, et al. Propionibacterium acnes, a resident of lipid-rich human skin, produces a 33 kDa extra-cellular lipase encoded by gehA. Microbiology. 1997;143:1745–1755. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-5-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jappe U, Ingham E, Henwood J, et al. Propionibacterium acnes and inflammation in acne; P. acnes has T-cell mitogenic activity. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:202–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bruggemann H, Henne A, Hoster F, et al. The complete genome sequence of Propionibacterium acnes, a commensal of human skin. Science. 2004;305:671–673. doi: 10.1126/science.1100330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bataille V, Snieder H, MacGregor AJ, et al. The influence of genetics and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of acne: a twin study of acne in women. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1317–1322. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chiu A, Chon SY, Kimball AB. The response of skin disease to stress: changes in the severity of acne vulgaris as affected by examination stress. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:897–900. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.7.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zeller V, Ghorbani A, Strady C, et al. Propionibacterium acnes: an agent of prosthetic joint infection and colonization. J Infect. 2007;55:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mohsen AH, Price A, Ridgway E, et al. Propionibacterium acnes endocarditis in a native valve complicated by intraventricular abscess: a case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:379–380. doi: 10.1080/003655401750174066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Callegan MC, Engelbert M, Parke DW, II, et al. Bacterial endophthalmitis: epidemiology, therapeutics, and bacterium–host interactions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:111–124. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.111-124.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Webster G. Mechanism-based treatment of acne vulgaris: the value of combination therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Layton AM, Knaggs H, Taylor J, et al. Isotretinoin for acne vulgaris – 10 years later: a safe and successful treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:292–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb11849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Huynh TT, Walling AD, Miller MA, et al. Propionibacterium acnes endocarditis. Can J Cardiol. 1995;11:785–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]