Abstract

Objective

To estimate the current effect of demographics, pathology, and treatment on mortality among women with vaginal cancer.

Methods

Using data from 17 population-based cancer registries that participate in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, 2,149 women diagnosed with primary vaginal cancer between 1990 to 2004 were identified. The association between various demographic factors, tumor characteristics, and treatments and risk of vaginal cancer mortality were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards modeling.

Results

The mean age at diagnosis was 65.7 ± 14.3 years. Approximately 66% of all cases were non-Hispanic whites. Incidence was highest among African-American women (1.24/100,000 person-years). The 5-year disease specific-survival was 84% (Stage I), 75% (Stage II), and 57% (Stage III/IV). In a multivariate adjusted model, women with tumors greater than 4 cm and advanced disease had elevated risks of mortality (HR 1.71, 4.67, respectively). Compared to women with squamous cell carcinomas, patients with vaginal melanoma had a 1.51-fold (95% CI: 1.07–2.41) increased risk of mortality. Surgery alone as a treatment modality had the lowest risk of mortality. The risk of mortality has decreased over time, as women diagnosed after 2000 had an adjusted 17% decrease in their risk of death compared to women from 1990–1994.

Conclusion

Stage, tumor size, histology, and treatment modality significantly affect a woman’s risk of mortality from vaginal cancer. There appears to be a survival advantage that is temporally related with the advent of chemoradiation.

Introduction

Vaginal cancer was first identified as a unique entity by Graham and Meigs in 1952(1). Since then, very few case series have been reported, and to this day there is still minimal information on its natural history, prognostic factors, and treatment. This can mostly be attributed to the rarity of this disease. In the United States, there are less than 2,500 new cases annually and less than 1,000 deaths(2). Worldwide, it only accounts for 1–3% of all gynecologic malignancies(3).

Vaginal cancer is predominantly a disease of older women, and approximately 50% of cases present in women over the age of 70 (4). Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histological type of vaginal cancer, accounting for nearly 80% of all cases in some reports(4). Recognized factors that increase a woman’s lifetime risk of vaginal cancer include younger age at coitarche, greater number of lifetime sexual partners, smoking, in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure(5, 6), and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection(7, 8). The etiology of vaginal cancer is closely-linked to cervical cancer, and HPV infection appears to be a necessary cofactor in most cases, OR 4.3 (95% CI 3.0–6.2) (7).

The largest population-based series reported to date on vaginal cancer is the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) report, which focused primarily on histology and survival for women diagnosed with vaginal cancer from 1985–1994(4). This report demonstrated a worse prognosis in women with vaginal melanoma as well as in older women. However, there is minimal additional data in the literature describing the impact of demographic factors, such as race/ethnicity and socio-economic status, on disease-specific mortality.

The treatment of vaginal cancer typically follows the same pathway as cervical cancer with Stage I cancers being offered radical surgery or radiation and those with locally advanced, node negative disease often being treated with radiation. In 1999 the National Cancer Institute (NCI) issued a clinical alert regarding the importance of concurrent cisplatin based chemotherapy with radiation for the treatment of locally advanced and node positive cervical cancers(9). This clinical alert was issued because multiple prospective randomized trials found a significant improvement in progression free and overall survival when cisplatin was given during the radiation. Since that report many clinicians have also incorporated the use of chemoradiation for the treatment of vaginal cancers. The use of chemoradiation reached wide-spread applicability in the late 1990s(10).

The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database of the NCI currently includes patient data from 17 population-based cancer registries (26% of the US population). The purpose of this study was to utilize a large population-based database (SEER) to estimate the modern day impact of demographic factors, pathologic features, and cancer treatments on risk of mortality among women with vaginal cancer.

Materials and Methods

This study was undertaken after obtaining approval by the Institutional Review Board of the Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington. Women diagnosed with primary vaginal carcinoma between January 1990 and November 2004 without prior history of any type of in situ or invasive cancer were identified through 17 population-based cancer registries in the United States that participate in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program. January 1990 was chosen as the starting point for this analysis as we wanted patients who had been treated with relatively contemporary radiation techniques. 2000 was used as a relative surrogate marker for the approximate wide-spread introduction of chemo-radiation. November 2004 was chosen as the ending date as this was the latest date for which all 17 of the available registries had collected data available at the time of the analysis.

The SEER program abstracts data from the medical records of patients. The operational details and methods used by the program have been described elsewhere(11), and it has been estimated that greater than 95% of all incident cancer cases in the regions under surveillance are ascertained. A total of 2,694 potentially eligible women with primary vaginal cancer were identified using SEER*Stat 6.4.4 (Information Management Services, Inc., Silver Spring, MD). Cases were excluded if they were less than 20 years old or greater than 89 years old (n=163). This age range was chosen because the vast majority of vaginal cancers diagnosed in the US occur in women in this age range. An additional 382 cases of occult vaginal cancer (Carcinoma in situ) were excluded from the multivariate models as these women are not at risk for cause specific mortality in most cases. 2149 cases of invasive vaginal cancer were included in the final multivariate analyses. The SEER program collects age, year of diagnosis, race/ethnicity, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, tumor size, tumor grade, number of positive lymph nodes, and histology. Additionally, the initial course of cancer-directed surgical and radiation treatment within the first four months is also available, though data on chemotherapy are not. Finally, vital status and survival time is ascertained annually. The duration of follow-up is calculated in months using the date of diagnosis and whichever occurs first, 1)date of death, 2) date last known to be alive, 3) November 2004 (the follow-up cutoff date used in our analysis. The primary outcome of interest in this study was cause-specific mortality, or death due to vaginal cancer as indicated by International Classification of Diseases cause-of-death codes. Using this approach, 2,531 cases were available and eligible for analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC 10.0 for Windows (College Station, TX). The associations between vaginal cancer mortality risk within categories of age at diagnosis (20–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89), year of diagnosis (5-year intervals: 1990 to 1994, 1995 to 1999, 2000 to 2004), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic white, African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander), county-level socio-economic status indicators (percent foreign born, median annual household income, percent less than a high school education, percent living below the federal poverty level, and unemployment percentage), histologic tumor type (squamous, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, other), AJCC stage (I, II, III/IV), grade (1–4), tumor size (0 to 3.9cm, ≥4.0cm), lymph node status (binary – yes/no), and treatment modality (surgery, radiation, both, none) were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model(12). Multivariate adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as estimates of relative risks of mortality. Based on log-log survival curves, proportional hazards assumption in these data was validated for predictive factors used in the analysis. We then analyzed our data using two sets of statistical models, one adjusted only for age and year of diagnosis and a multivariate adjusted model that was additionally adjusted for stage and treatment. We evaluated for confounding by tumor size, grade, lymph node status, and histology. There was no significant confounding by these variables. Since stage was a likely effect modifier of the relationship between treatment and risk of mortality, our assessments of the impact of treatment were stratified by stage and p-values for interactions were calculated based on likelihood ratio testing. Incidence rates within categories were calculated using the rate session feature of SEER*Stat. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and statistical significance assessed with the log-rank test.

Results

The mean age at diagnosis of women with vaginal cancer for the study period 1990–2004 was 65.7 ± 14.3 years, and incidence rates of vaginal cancer increased with age such that the rate among 80–89 year-olds was 4.43/100,000 person-years, but was only 0.03/100,000 person-years among 20–29 year-olds (Table 1). The majority of women included were non-Hispanic whites (66%), followed by African-Americans (14%), Hispanic whites (12%), Asian/Pacific Islanders (7%), and others (1%). Incidence rates varied by race/ethnicity with African American women having the highest rate (1.24/100,000 person-years), and Asians/Pacific Islanders had the lowest rate (0.64/100,000 person-years). There were a greater number of cases diagnosed between the years 2000 to 2004 as four additional cancer registries became part of the SEER program starting in 2000: Greater California, Kentucky, Louisiana, and New Jersey. By region, the highest incidence rate was found in the metropolitan Detroit area (MI), 1.32 per 100,000 women, and the lowest in the state of Utah, 0.56 per 100,000 women. Rates also tended to be somewhat higher in counties with lower median household incomes, higher unemployment rates, and with a greater proportion of the population living below the Federal Poverty Level. The greatest proportion of women had Stage I disease, 36% (IR 0.21 per 100,000 person-years), and most had squamous histology, 65% (IR 0.65 per 100,000).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinico-pathologic characteristics, and age-adjusted incidence rates

| Demographic Characteristics | n | % | IR† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | (n=2531) | ||

| 20–29 | 17 | 1 | 0.03 |

| 30–39 | 99 | 4 | 0.17 |

| 40–49 | 268 | 10 | 0.51 |

| 50–59 | 446 | 18 | 1.15 |

| 60–69 | 567 | 22 | 2.08 |

| 70–79 | 651 | 26 | 3.22 |

| 80–89 | 483 | 19 | 4.43 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 1684 | 66 | 1.01 |

| Hispanic Whites | 296 | 12 | 0.86 |

| African American | 344 | 14 | 1.24 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 178 | 7 | 0.64 |

| Others | 29 | 1 | 0.73 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 1990–1994 | 544 | 21 | 1.03 |

| 1995–1999 | 640 | 25 | 0.97 |

| 2000–2004 | 1347 | 53 | 1.02 |

| SEER Registry | |||

| Alaska Natives | 4 | <1 | 1.04 |

| Atlanta | 133 | 5 | 0.89 |

| California | 290 | 11 | 0.93* |

| Connecticut | 176 | 7 | 1.00 |

| Detroit | 286 | 11 | 1.32 |

| Hawaii | 52 | 2 | 0.84 |

| Iowa | 151 | 6 | 1.04 |

| Kentucky | 87 | 3 | 1.20* |

| Los Angeles | 426 | 17 | 1.04 |

| Louisiana | 91 | 4 | 1.16* |

| New Jersey | 167 | 7 | 1.09* |

| New Mexico | 95 | 4 | 1.11 |

| Rural Georgia | 7 | <1 | 1.23 |

| San Francisco-Oakland | 217 | 9 | 0.98 |

| San Jose-Monterey | 97 | 4 | 0.95 |

| Seattle-Puget Sound | 194 | 8 | 0.94 |

| Utah | 58 | 2 | 0.56 |

|

| |||

| County-level Socio-economic Characteristics | |||

| Percent Foreign Born | |||

| <5.0% | 358 | 14 | 1.03 |

| 5.0–14.9% | 871 | 34 | 1.07 |

| 15.0–29.9% | 723 | 29 | 0.91 |

| ≥30.0% | 579 | 23 | 1.01 |

| Median Annual Household Income | |||

| <$40,000 | 423 | 17 | 1.12 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 1229 | 49 | 1.04 |

| ≥$50,000 | 879 | 34 | 0.93 |

| % Less than a High School Education | |||

| <15.0% | 703 | 28 | 0.88 |

| 15.0–24.9% | 1161 | 46 | 1.09 |

| ≥25.0% | 667 | 26 | 1.04 |

| % Living Below the Federal Poverty Level | |||

| <10.0% | 968 | 38 | 0.94 |

| 10.0–14.9% | 629 | 25 | 0.96 |

| >15.0% | 934 | 37 | 1.12 |

| Unemployment Percentage | |||

| <4.0% | 368 | 15 | 0.96 |

| 4.0–7.9% | 1274 | 50 | 0.94 |

| ≥8.0% | 889 | 35 | 1.11 |

|

| |||

| Tumor Characteristics | |||

| Stage | |||

| Stage 0 (Carcinoma in situ) | 382 | 17 | 0.21 |

| Stage I | 805 | 36 | 0.21 |

| Stage II | 493 | 22 | 0.12 |

| Stage III | 252 | 11 | 0.06 |

| Stage IV | 312 | 14 | 0.05 |

| Histology | |||

| Squamous cell | 1624 | 65 | 0.65 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 359 | 14 | 0.13 |

| Melanoma | 147 | 6 | 0.07 |

| Other | 371 | 15 | 0.21 |

Incidence rates are per 100,000 person-years from 1992–2004 and are derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 13 Regs Limited-Use, Nov 2006 Sub (1992–2004) - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2004 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2007, based on the November 2006 submission.

Incidence rates are from 2000–2004 since these registries were not added to the SEER program until 2000.

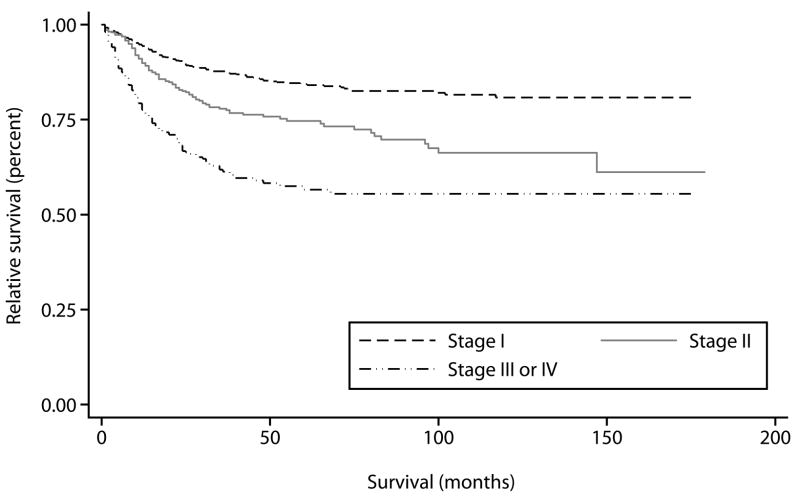

Based on Kaplan-Meier curves, the 5-year disease specific survival for women with Stage I tumors was 84% (95% CI 82–87%), 75% for Stage II tumors (95% CI 70–79%), and 57% for women with advanced disease (95% CI 50–62%) (Figure 1). Tumor size was evaluated as a continuous and dichotomous variable, and survival was worse in women with tumors greater than 4 cm (p<0.001 by log-rank test, 5 year survival 84% vs. 65%). 5-year disease specific survival was also comparable across histologies, 78% for squamous cell carcinomas (95% CI 75–79%), 78% for adenocarcinomas (95% CI 72–84%), 70% for melanomas (95% CI 62–77%), and 73% (95% CI: 59% to 82%) for other rarer histologic types.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier disease-specific overall survival in women with vaginal cancer from 1990–2004 compared by stage.

In our multivariate adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, year of diagnosis, race/ethnicity, and county level indicators of socioeconomic status were not related to risk of vaginal cancer mortality (Table 2). Not surprisingly, stage was strongly related to risk as compared to women with stage I disease, those with stage II and stage III/IV disease had elevated risks of mortality (HR=2.46 and 4.97, respectively). Additionally, age at diagnosis, tumor size, and lymph node status were related to risk; though grade was not. Compared to women with squamous cell carcinomas, those diagnosed with melanoma or vaginal cancer of a rarer other histologic type had 51% (95% CI: 7% to 141%) and 33% (95% CI: 4% to 81%) elevated risks of mortality, respectively. There was a trend toward improved survival over time with a 17% reduction in mortality by 2000–2004, even when potential confounding factors were taken into account.

Table 2.

Cox regression of predictive factors

| Predictor1 | No. of cases at risk | Person time (yrs) | No. of deaths | Age and diagnosis year adjusted hazard ratio† | 95% CI | Multivariate-adjusted hazard ratio†† | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| 20–39 | 100 | 461 | 15 | 0.89 | 0.50–1.56 | 1.14 | 0.64–2.04 |

| 40–49 | 235 | 877 | 36 | 1.01 | 0.66–1.54 | 1.03 | 0.67–1.59 |

| 50–59 | 376 | 1301 | 54 | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | ref |

| 60–69 | 487 | 1641 | 72 | 1.04 | 0.73–1.49 | 1.05 | 0.73–1.50 |

| 70–79 | 521 | 1512 | 97 | 1.44* | 1.03–2.01 | 1.56* | 1.10–2.19 |

| 80–89 | 374 | 1598 | 84 | 2.14** | 1.51–3.01 | 2.12** | 1.48–3.03 |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||||||

| 1990–1994 | 425 | 2430 | 99 | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | ref |

| 1995–1999 | 526 | 2162 | 115 | 1.02 | 0.78–1.33 | 0.96 | 0.73–1.26 |

| 2000–2004 | 1142 | 1965 | 144 | 0.85 | 0.66–1.01 | 0.83 | 0.63–1.08 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 1402 | 4504 | 254 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| Hispanic Whites | 252 | 727 | 35 | 0.89 | 0.62–1.27 | 1.02 | 0.71–1.45 |

| African-Americans | 284 | 788 | 47 | 1.08 | 0.79–1.47 | 1.03 | 0.75–1.43 |

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | 147 | 473 | 21 | 0.78 | 0.50–1.23 | 0.75 | 0.48–1.18 |

| % Less than a High School Education2 | |||||||

| <15.0% | 587 | 2217 | 104 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| 15.0–24.9% | 961 | 2741 | 174 | 1.12 | 0.88–1.43 | 1.14 | 0.89–1.48 |

| ≥25.0% | 545 | 1599 | 80 | 0.91 | 0.68–1.22 | 1.02 | 0.76–1.38 |

| Unemployment Percentage1 | |||||||

| <4.0% | 297 | 1090 | 63 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| 4.0–7.9% | 1078 | 3241 | 185 | 0.88 | 0.66–1.18 | 0.93 | 0.69–1.26 |

| ≥8.0% | 718 | 2226 | 110 | 0.77 | 0.56–1.05 | 0.84 | 0.61–1.15 |

| Stage | |||||||

| I | 799 | 3543 | 79 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| II | 490 | 1730 | 105 | 2.46** | 1.83–3.30 | 2.35** | 1.74–3.19 |

| III/IV | 554 | 1167 | 162 | 4.97** | 3.78–6.52 | 4.67** | 3.53–6.19 |

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 134 | 462 | 22 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| 2 | 565 | 1912 | 103 | 1.16 | 0.73–1.84 | 1.01 | 0.63–1.63 |

| 3 | 633 | 1794 | 119 | 1.32 | 0.84–2.09 | 1.10 | 0.68–1.76 |

| 4 | 78 | 230 | 21 | 1.96* | 1.07–3.57 | 1.67 | 0.91–3.10 |

| Histology | |||||||

| Squamous | 1390 | 4584 | 233 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| Adenocarcinoma | 291 | 949 | 47 | 1.08 | 0.78–1.48 | 1.07 | 0.77–1.48 |

| Melanoma | 123 | 250 | 21 | 1.23 | 0.79–1.92 | 1.51* | 1.07–2.41 |

| Other | 282 | 769 | 55 | 1.39* | 1.03–1.86 | 1.33* | 1.04–1.81 |

| Tumor Size | |||||||

| Less than 4cm | 554 | 2357 | 74 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| Greater than 4cm | 471 | 1408 | 127 | 2.43* | 1.82–3.24 | 1.71** | 1.25–2.33 |

| Positive Lymph Nodes | |||||||

| No | 313 | 1219 | 33 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| Yes | 102 | 218 | 29 | 3.75 | 2.25–6.26 | 2.90* | 1.09–7.72 |

| Treatment | |||||||

| Surgery | 483 | 1805 | 50 | 1.00 | ref | 1.00 | ref |

| Radiation | 755 | 2676 | 177 | 2.03** | 1.47–2.79 | 1.38 | 0.98–1.95 |

| Both | 645 | 1602 | 92 | 1.71* | 1.21–2.42 | 1.35 | 0.93–1.96 |

| None | 172 | 380 | 35 | 2.54** | 1.64–3.93 | 2.07* | 1.32–3.25 |

Model Adjusted for Age and Year of Diagnosis

Final Multivariate Model Adjusted for Age, Year of Diagnosis, Stage, and Treatment

Significant at p-value <0.05

Significant at p-value <0.001

Missing data for predictors is as follows: Grade (707, 32.9%); Tumor Size (1120, 52.1%); Histology (9. 0.4%); Lymph Node Status (1728, 80.4%)

County-based socio-economic characteristics are derived from SEER and are not individually defined

In our study, only 10% of women undergoing surgery had a surgery that was coded as a radical procedure, lower than historically reported (13). However, primary treatment with surgery and/or radiation was not related to risk of mortality in our multivariate adjusted model. A stratified analysis was performed to further address the impact of treatment within women of each stage (Table 3). Among women with stage I disease, compared to women whose primary treatment consisted only of surgery, those treated with only radiation, combined modalities, or no treatment had elevated risks of mortality; but only women with stage I disease who received no treatment had a statistically significant increased risk of mortality (HR=2.23; 95% CI: 1.01–5.03). In women with stage II vaginal cancer, there was a similar trend toward increased mortality in those women who did not have surgery alone as the primary treatment modality but none of the values reached statistical significance. Finally, in women with advanced disease, the differences in mortality associated with treatment modality were within the limits of chance.

Table 3.

The effect of treatment stratified by stage

| Treatment† | No. of cases at risk | Person time (yrs) | No. of deaths | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stage I | |||||

| Surgery | 147 | 1760 | 10 | 1.00 | ref |

| Radiation | 110 | 548 | 15 | 1.51 | .89–2.56 |

| Both | 120 | 446 | 15 | 1.33 | .76–2.32 |

| None | 16 | 68 | 3 | 2.23* | 1.01–5.03 |

|

| |||||

|

Stage II | |||||

| Surgery | 46 | 139 | 8 | 1.00 | ref |

| Radiation | 166 | 679 | 41 | 1.63 | 0.78–3.41 |

| Both | 97 | 349 | 18 | 1.35 | 0.60–3.05 |

| None | 13 | 408 | 2 | 2.57 | 0.91–7.22 |

|

| |||||

|

Stage III/IV | |||||

| Surgery | 34 | 71 | 8 | 1.00 | ref |

| Radiation | 144 | 371 | 47 | 0.91 | 0.55–1.51 |

| Both | 93 | 217 | 24 | 0.71 | 0.40–1.25 |

| None | 24 | 39 | 8 | 1.94* | 1.04–3.61 |

Model adjusted for Age, Year of Diagnosis, Tumor Size, and Grade

Significant at p-value < 0.05

Discussion

Before interpreting the results of our study, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. First, our study was based on data that had already been collected. With respect to missing data, information on tumor size, one of our primary predictors, was missing for 52% of cases. This could be a potential source of bias. Likely, tumor size is more frequently missing for larger lesions that are not surgical candidates. This feature of the data could lead to a risk estimate biased toward the null if individuals with large lesions and a poor prognosis have an unknown tumor size. However, this is probably somewhat offset by the difficulty in measuring smaller lesions, and some of the missing data on tumor size may be attributable to the uncertainty in these measurements. The data does appear to be quite complete for many of the other predictors of interest; however, data on tumor grade is missing for 33% of cases, and the misclassification for tumor grade is likely differential as well.

In addition, several covariates of interest are unavailable from the SEER database. Of most significant concern is the lack of data on chemotherapy. Therefore, we cannot fully evaluate the effect of chemotherapy on mortality or the combination/sequencing of chemotherapy with radiation and surgical treatments. However, using year of diagnosis as a surrogate for the introduction of chemoradiation, we do see a trend toward lower risk of death after 2000 in our multivariate model as compared to women diagnosed between 1990–1994 (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63–1.08, p=0.07). Additionally, we were unable to evaluate potential confounders that may not have been available in the SEER database. For example, HPV (OR 4.3, 95% CI 3.0–6.2), smoking (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.4 to 3.1), and number of lifetime partners (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.9–4.9) have been shown in a population-based case-control study to be associated with vaginal cancer incidence, although their impact on vaginal cancer mortality is unclear (7). Overall, the impact of the residual confounding by unmeasured predictors is uncertain, but due to the observational nature of this study, readers should interpret its results accordingly.

Despite its limitations, our study is one of the largest to date addressing a distinctly rare disease process, vaginal cancer. Most of the reports in the literature consist of small, single institution retrospective series ranging from 70–314 patients(8, 13, 14). Additionally, due to the rarity of the disease, the case series presented reflect a long period of time with heterogeneous clinical data and treatment techniques. Although the SEER program is not without its own limitations, our study utilizes data that are population-based, collected from women diagnosed in multiple geographic regions, and includes a large sample size.

One of the advantages of the SEER database is that it allows the calculation of incidence rates, and our study is one of the first to present modern trends in incidence in women with vaginal cancer. Incidence rates increase sharply with age and also vary considerably by race/ethnicity. A recent study using 39 cancer registries similarly found the age-adjusted incidence rate of invasive squamous cell cancer was 72% higher in African-American women which correlated with a higher proportion of late stage disease and lower survival(15). Lower survival was also seen in Hispanic and Asian-Pacific Islander women. In our study, incidence rates are also somewhat higher in areas with a lower socioeconomic status. These differences likely correlate with distributions of the known risk factors for vaginal cancer, particularly the prevalence of oncogenic HPV infection(16). With respect to clinical characteristics, the majority of vaginal cancer cases are Stage 1 and have a squamous cell histology as has been previously described(4).

Another major strength of our study is that it does confirm the results of various prior studies that have evaluated risk factors for vaginal cancer mortality, lending credence to our findings. For example, Hellman found that older age (HR 1.2 for each 10 year increment, 95% CI 1.06–1.29), tumors greater than or equal to 4 cm (HR 2.1, 95% CI 1.3–3.3), and advancing stage (HR 2.5 for Stage II disease, 95% CI 1.3–4.6) were the only factors that predicted poor survival in a multivariate analysis of 314 patients. Similarly, in our study, advanced stage disease was associated with a 2.3–4.7 fold increase in the risk of death from vaginal cancer, and tumor size greater than 4 cm was associated with a 1.7-fold increase in our multivariate analysis. Creasman found a very poor prognosis associated with vaginal melanoma with a 5-yr survival of 14%. We also found that vaginal melanoma was associated with an increased risk of mortality in our multivariate model (HR 1.51)(4). However, the 5-yr survival for women in our study (70%) was much better than has been previously reported.

In a review of 100 cases from 1962–1992, Stock found that treatment with surgery was a significantly favorable prognostic factor for disease-free survival when compared to patients treated with radiation therapy alone, especially in patients with stage I–II disease (p<0.001)(13). We found in a stratified analysis of the effect of treatment modality by stage, stage I patients did worse when treated with radiation alone or a combination of both radiation and surgery (HR 1.51 and 1.33 respectively). Other authors have also found excellent results with primary surgical therapy, but the surgery required to provide negative margins often involved radical, exenterative surgery in as many as 40–50% of cases(17, 18). Given the morbidity and mortality of these procedures, radiation has often been utilized as the primary treatment modality when the tumor deemed surgically unresectable. The use of radical surgery appears to have decreased over time, as our data suggests a much lower use of radical surgery (~10%). Whether this can be attributed to a greater use of chemo-radiation is unclear from our data, but up-front surgery when possible appears to improve survival. There is most likely a clear selection bias in terms of those patients who undergo surgery primarily. In most cases surgery is often performed with a curative intent; therefore, when the surgeon feels surgery may not be successful in removing the entirety of the tumor, the patient is often referred for radiation therapy. In addition, women with early stage disease who end up receiving both surgery and radiation are likely to have poor prognostic factors determined at the time of their surgery such as positive margins or pelvic nodal metastases found at the time of surgery that required additional, adjuvant radiation therapy. These poor prognostic factors are the most likely explanation for the worse outcome observed in those women receiving multi-modality treatment. Finally, those women who are not good surgical candidates due to medical co-morbidities, body habitus, or age are often referred for radiation therapy instead.

The NCI issued its clinical alert after several studies demonstrated significant improvementin both progression-free survival and overall survival whencisplatin-based chemotherapy was administered during radiationfor various stages of cervical cancer(19–21). Vaginal cancer has often been treated similarly to cervical cancer(22) as they partially contain the same epithelium, are embryologically similar, and they share many of the same exposures as risk factors(3, 17, 23). Dalrymple found in a small group of patients (n=14) that primary therapy with synchronous radiation and chemotherapy was effective and reasonably well tolerated. However, there is a dearth of data on population-based level on the impact of concurrent chemo-radiation in women with vaginal cancer. Our data suggest an improvement in mortality in women diagnosed after the year 2000 coinciding with the NCI alert.

In conclusion our data confirm that stage, tumor size, histology, and treatment modality are significant prognostic factors in women with vaginal cancer. When possible in early stage disease, surgery appears to confer a survival advantage. The decision on treatment modality must still be made in the context of the individual patient as it is unlikely that prospective trials will be undertaken to answer this specific question. In the future we may be able to see if the trend of decreased mortality with modern treatment continues; but presently, it appears there may be an ongoing reduction in the risk of mortality associated with the use of chemo-radiation in women with vaginal cancer.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure:The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Oncology Training Grant, number 5 T32 CA09515-22. Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Seattle, WA

NIH K30, Clinical Research Training Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

References

- 1.Graham JB, Meigs JV. Earlier detection of recurrent cancer of the uterine cervix by vaginal smear. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1952 Oct;64(4):908–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)38804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2006 Mar–Apr;56(2):106–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creasman WT. Vaginal cancers. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2005 Feb;17(1):71–6. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200502000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creasman WT, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the vagina. Cancer. 1998 Sep 1;83(5):1033–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbst AL, Norusis MJ, Rosenow PJ, Welch WR, Scully RE. An analysis of 346 cases of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix with emphasis on recurrence and survival. Gynecologic oncology. 1979 Apr;7(2):111–22. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(79)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst AL, Scully RE. Adenocarcinoma of the vagina in adolescence. A report of 7 cases including 6 clear-cell carcinomas (so-called mesonephromas) Cancer. 1970 Apr;25(4):745–57. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197004)25:4<745::aid-cncr2820250402>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Carter JJ, McKnight B, et al. A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecologic oncology. 2002 Feb;84(2):263–70. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellman K, Lundell M, Silfversward C, Nilsson B, Hellstrom AC, Frankendal B. Clinical and histopathologic factors related to prognosis in primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 May–Jun;16(3):1201–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cancer Institute: NCI Clinical Announcement. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 1999. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omura GA. Progress in gynecologic cancer research: the Gynecologic Oncology Group experience. Seminars in oncology. 2008 Oct;35(5):507–21. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young JL, Jr, Percy CL, Asire AJ, Berg JW, Cusano MM, Gloeckler LA, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1973–77. National Cancer Institute monograph. 1981 Jun;(57):1–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DR. Regression model and life tables (with discussion) J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J. A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecologic oncology. 1995 Jan;56(1):45–52. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otton GR, Nicklin JL, Dickie GJ, Niedetzky P, Tripcony L, Perrin LC, et al. Early-stage vaginal carcinoma--an analysis of 70 patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004 Mar–Apr;14(2):304–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.014214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, Matanoski G, Chen VW, Saraiya M, Coughlin SS, King JB, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of vaginal cancer incidence and survival by race, ethnicity, and age in the United States. Cancer. 2008 Nov 15;113(10 Suppl):2873–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan MJ, Partridge EE, Wang SS, Schiffman M. Socioeconomic status and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 among oncogenic human papillomavirus DNA-positive women with equivocal or mildly abnormal cytology. Cancer. 2005 Jul 1;104(1):61–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis KP, Stanhope CR, Garton GR, Atkinson EJ, O’Brien PC. Invasive vaginal carcinoma: analysis of early-stage disease. Gynecologic oncology. 1991 Aug;42(2):131–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90332-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin SC, Young J, Mikuta JJ. Squamous carcinoma of the vagina: treatment, complications, and long-term follow-up. Gynecologic oncology. 1985 Mar;20(3):346–53. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(85)90216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters WA, 3rd, Liu PY, Barrett RJ, 2nd, Stock RJ, Monk BJ, Berek JS, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Apr;18(8):1606–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, Maiman MA, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Apr 15;340(15):1144–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitney CW, Sause W, Bundy BN, Malfetano JH, Hannigan EV, Fowler WC, Jr, et al. Randomized comparison of fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus hydroxyurea as an adjunct to radiation therapy in stage IIB-IVA carcinoma of the cervix with negative para-aortic lymph nodes: a Gynecologic Oncology Group and Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1999 May;17(5):1339–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henson D, Tarone R. An epidemiologic study of cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva based on the Third National Cancer Survey in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1977 Nov 1;129(5):525–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grigsby PW. Vaginal cancer. Current treatment options in oncology. 2002 Apr;3(2):125–30. doi: 10.1007/s11864-002-0058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]