Abstract

Objective

This systematic review assesses the impact of peer education/counseling on nutrition and health outcomes among Latinos, and identifies future research needs.

Design

A systematic literature search was conducted by: a) searching internet databases, b) conducting backward searches from reference lists of articles of interest, c) manually reviewing the archives of the Center for Eliminating Health Disparities among Latinos (CEHDL), d) searching the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, and e) directly contacting researchers in the field. We reviewed 22 articles derived from experimental or quasi-experimental studies.

Outcomes

Type 2 diabetes behavioral and metabolic outcomes, breastfeeding, nutrition knowledge, attitudes and behaviors.

Results

Peer nutrition education has a positive influence on diabetes self-management, breastfeeding outcomes, as well as on general nutrition knowledge and dietary intake behaviors among Latinos.

Conclusions and implications

There is a need for longitudinal randomized trials testing the impact of peer nutrition education interventions grounded on goal setting and culturally appropriate behavioral change theories. Inclusion of reliable scales and the construct of acculturation is needed for further advancing the knowledge in this promising field. Operational research is also needed to identify the optimal peer educator characteristics, the type of training that they should receive, the client loads and dosage (i.e., frequency and amount of contact needed between needed peer educator and client), and the best educational approaches and delivery settings.

Keywords: acculturation, behavioral change theory, breastfeeding, community health worker, diabetes, EFNEP, FSNE, Hispanic, Latino, nutrition education, peer

Introduction

Latinos1 are the largest minority group in the U.S. comprising over 12% of the population and are expected to be nearly 25% of the population by 2050. Over 40% of Latinos are foreign-born, with almost half residing in California and Texas. Latinos represent over 20 different countries of origin from Central America, South America, the Caribbean, and Europe. Over 22% of Latinos live in poverty, compared with 8.2% of non-Latino white individuals. Contributing to poor socioeconomic status are higher unemployment rates, lower status employment, and lower educational attainment among Latinos compared to non-Latino white individuals (1, 2).

Latinos have less access to nutritionally adequate and safe foods. Compared to 7.8% of non-Latino white individuals, almost 20% of Latinos are food insecure (3). Food insecurity has been linked to poor dietary quality, low quantity of food, and overweight/obesity. The high incidence of risk factors and chronic diseases among Latinos including obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (4-6) is exacerbated by lower physical activity levels compared to the rest of the population (7, 8).

Peer Educators/Community Health Workers2

Community health workers (CHWs) have been defined as ‘community members who work almost exclusively in community settings and serve as connectors between health care consumers and providers to promote health among groups that have traditionally lacked access to adequate care’(9, 10). CHWs are expected to come from communities of the same socioeconomic status as those they serve, and to have similar cultural and social life experiences as their target clients. The nomenclature used to describe CHWs varies greatly in the scientific literature. CHWs have been referred to as promotoras, lay health workers, community health advisors, paraprofessionals, patient navigators, outreach workers, aides, peer educators, and peer counselors; without having clear specific definitions of these terms. The term used does not appear to be solely a function of the discipline studied or tasks performed.

Ideally, CHWs should have experienced a similar condition (e.g., diabetes) or practiced the same behavior (e.g., breastfeeding) that they are addressing and/or should have provided key support to a close friend or relative with the condition or practicing the behavior of interest (9-12). The Chronic Care Model (11) posits that CHWs play a crucial role linking communities with the health care system. CHWs' can perform multiple tasks including disease and case management, the simple transfer of health information, support with medical appointments (e.g., setting appointment, transportation, presence during appointment), and support for health promotion (12).

The documentation of the use of paraprofessionals to deliver social and health services in the U.S. began in the 1960's. Indeed, the use of nutrition education paraprofessionals was formally institutionalized through the creation of the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) in the early 60s (13), and has greatly expanded through the Food Stamp Nutrition Education Program (FSNE) (14). In developing countries, CHWs have been and continue to be used extensively to address diverse problems including infant mortality and causal factors (malnutrition, measles and other communicable diseases, diarrhea, respiratory infections), HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria (10, 15). Demonstration projects and small-scale programs in the U.S. and other developed countries have shown that CHWs are effective at improving diverse outcomes including infant feeding, immunizations, HIV prevention/self-management, diabetes self-management and breast cancer screening rates (10, 15, 16). However, the impact of peer nutrition educators has not been systematically reviewed.

A recent report from a conference on peer-led approaches to dietary change in the UK (17) reviewed three studies grouped into three categories: a) older people living in shelters, b) mother and infants (emphasis on weaning foods), and c) individuals with diabetes. All studies targeted low-income individuals. The author concluded that these peer led interventions can have positive impacts on knowledge, confidence and attitudes, and small improvements in diet change. However, this conclusion should apply only to the infant feeding study as there were no positive results reported from the diabetes and elderly studies. For the latter two studies, the internal validity is highly questionable due to high attrition rates and limited statistical power. There are no published reviews addressing the effectiveness of CHWs that deliver nutrition education to Latinos. However, a systematic review published over a decade ago evaluated the impact of peer nutrition education. These findings are summarized in the following section.

Impact of nutrition education

In 1995 Contento et al. (13) examined the effectiveness of nutrition education at improving knowledge, attitudes and behaviors across the life span. Their review included 217 experimental or quasi-experimental studies with adequate documentation of instrument reliability and validity. The authors included a chapter on the impact of training of paraprofessionals (EFNEP and WIC nutrition aides, school food service staff) and professionals (school teachers, nutritionists, health professionals) on their nutrition education effectiveness. Based on two controlled studies (18, 19) the authors concluded that well developed trainings are effective at increasing paraprofessionals' general nutrition knowledge and breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy (for teaching breastfeeding). The review (13) strongly supports a positive impact of paraprofessionals on nutrition knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of target audiences. However, little emphasis was placed on Latino target audiences, which is understandable since the major growth of the Latino community nationwide is relatively recent and few studies were available at the time when their review was published.

Objectives

The objectives of this systematic review are to: a) assess the impact of peer education/counseling on type 2 diabetes, breastfeeding and other nutrition knowledge, attitudinal, and behavioral outcomes among Latinos, b) discuss the policy implications of findings, and c) identify gaps in knowledge and future research needs. This review covers studies based on federal nutrition education programs (EFNEP and FSNE), as well as demonstration nutrition education programs.

Methodology

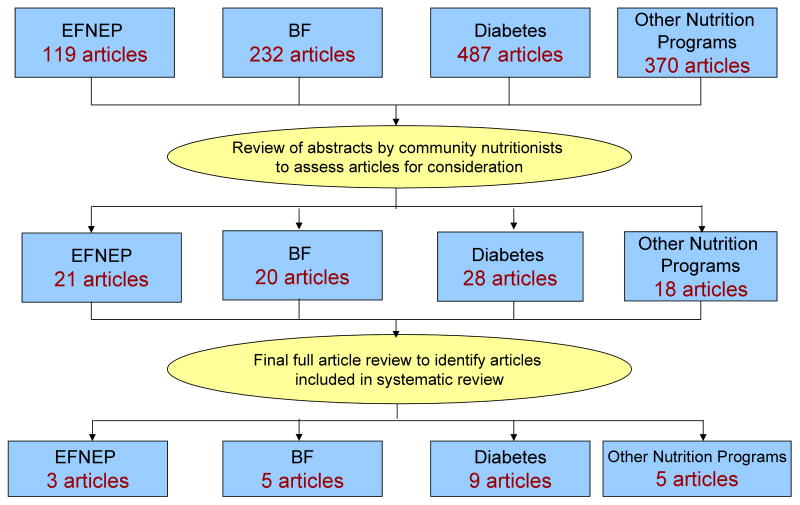

A systematic literature search (Figure 1) was conducted by: a) searching internet databases (PubMed), b) conducting backward searches using reference lists from articles of interest, c) manually reviewing the archives of the Center for Eliminating Health Disparities among Latinos (CEHDL), d) searching the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, and e) directly contacting researchers in the field. The PubMed search was conducted using the following key words and combinations: Latino(s), Hispanic(s), community health worker(s), peer(s), educator(s), peer education, promotora(s), promoter(s), diabetes, nutrition, la cocina saludable, salud para su corazón, su corazón su vida, your health your life, partner(s) in health, compañeros en salud, EFNEP, FSNE, breastfeeding. For the purpose of this review, nutrition education is defined as ‘any set of learning experiences designed to facilitate the voluntary adoption of eating and other nutrition-related behaviors conducive to health and well being’ (13). Nutrition education impact studies were included if they met the following criteria: a) experimental or quasi-experimental design, b) include Latino specific results or a predominantly Latino study population (>60%), c) use of reliable and valid scales3, d) nutrition education intervention(s) clearly described, e) published since 1994, and f) conducted in the United States. All abstracts of articles generated from the database searches were reviewed by community nutrition academic and agency experts (i.e. the authors of this paper) to identify those that met the inclusion criteria. Of the 87 articles initially identified for full review, 65 were eliminated (Table 1). Thus, this review is based on 9 diabetes articles, 5 breastfeeding promotion articles, 3 EFNEP articles, and 5 articles presenting four nutrition education demonstration programs (Tables 2-5). No FSNE studies met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Systematic Literature Review Process

Table 1.

Exclusionary Factors for Inclusion in Review

| Reasons | Number of articles excluded | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes [19] a |

Breastfeeding [15] |

EFNEP [18] |

Other nutrition programs [13] |

|

| Small percentage of sample were Latinos | 2b (57, 58) c |

7 (59-65) |

9 (36-38, 41, 44, 56, 66-68) |

5 (69-73) |

| Used other health professional rather than peer counselors/community health workers | 1 (74) |

2 (75, 76) |

---- | ---- |

| Article does not report results using an experimental or quasi-experimental design (i.e. process evaluation article, study description article etc.) | 6 (77-82) |

2 (83, 84) |

---- | 5 (85-89) |

| No Latinos included in sample | ---- | 1 (90) |

1 (91) |

---- |

| Ethnic composition of population sample not defined | ---- | ---- | 5 (42, 43, 92-94) |

2 (95, 96) |

| Publication only available as conference abstract | ---- | ---- | 1 (97) |

1 (98) |

| Intervention did not include nutrition education | 2 (99, 100) |

---- | ---- | ---- |

| Intervention was not specific to diabetes management | 5 (51, 101-104) |

---- | ---- | ---- |

| Promotoras/community health workers were not involved in diabetes nutrition education instruction | 2 (105, 106) |

---- | ---- | ---- |

| Did not involve community health workers | 1 (107) |

1 (108) |

---- | ---- |

| Could not locate articles | ---- | ---- | 2 (109, 110) |

---- |

| Incomplete data for Latinas | 1 (111) |

|||

| Insufficient data to assess study | ---- | 1 (112) |

---- | ---- |

Indicates the number of articles excluded per section.

Indicates the number of articles excluded per reason.

References.

---- indicates that was not a reason for exclusion of an article within the section.

Table 2.

Impact of peer nutrition education among Latinos with type 2 diabetes

| Randomized trials | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Sample | Design/Measures | Intervention/Theory | Results | Comments |

| Corkery et al. (22) | New York, NY | Randomized

|

All participants enrolled in a diabetes education program | Forty participants completed education program | Possible bias:

|

| 64 Hispanic patients primarily of Puerto Rican origin; 40 (63%) completed study | Pre-/post- knowledge test | Additional support by CHW as liaison with medical providers, to remind about upcoming appointments, and to reinforce self-care instructions | Greater diabetes education program completion among participants with CHW (80% vs. 47%; P=0.01) | Possible lack of statistical power | |

| newly referred to diabetes management clinic for education | Outcomes:

|

No behavioral change theory specified | No statistical difference in knowledge, lifestyle behaviors, or metabolic outcomes by CHW assignment | No follow-up to participants who did not complete education program | |

| > 20 y old | Main outcome was program completion; no clinical outcomes | ||||

| Lujan et al. (23) | Texas-Mexico Border | Randomized controlled trial:

|

Culturally-specific 6-month intervention | HbA1c decreased (0.45%) for intervention group and increased (0.30%) for control group. Mean changes were significantly different (P<0.001) | Extensive training for promotoras |

| Mexican Americans | Baseline, 3- and 6-month data collection | 8 weekly 2-h group classes | Greater change in diabetes knowledge score with intervention (P<0.002) | Unknown extent of nutrition education, but classes met ADA's diabetes education curriculum guidelines | |

| 150 patients > 40 y with type 2 diabetes | Survey:

|

Telephone follow-up calls | No change in patients' belief in their ability to manage diabetes | ||

| Exclusions: diabetes complications interfering with class participation |

HbA1c | Behavior change postcards mailed biweekly for 16 weeks | |||

| Community empowerment theory | |||||

| Quasi-experimental trials | |||||

| Education | |||||

| Reference | Sample | Design/Measures | Intervention/Theory | Results | Comments |

| Culica et al. (30) | Dallas, TX | Pre-/post- evaluation | Community health worker-led:

|

Significant decrease in HbA1c (-1.08%, P<0.01) | Patients of all ethnic background enrolled; 78% of participants were Mexican American |

| 92 diabetes patients, >18y | Clinical data:

|

No change in BMI or blood pressure | No control group | ||

Exclusions:

|

Patient participation rates | One-to-one education | |||

| HbA1c available only for 55 patients | |||||

| Small sample size; potential lack of statistical power | |||||

| Philis-Tsimikas et al. (28) | San Diego County, CA | Pre-/post- 1-y program participation evaluation | 12 months of nurse case management (mean of 8 visits/y)

|

Among Project Dulce Participants:

|

No Latino-specific results; 72% of project participants were Latino |

| Adults (18-80 y) with type 1 and type 2 diabetes | No random assignment | Peer-educator led group-based classes: 12 weekly 2-hour sessions

|

No significant changes in control group | Only 56% of Project Dulce participants attended peer education classes; unable to distill effect of peer education | |

Exclusions:

|

Measures:

|

Staged diabetes management | No randomization | ||

| Project Dulce group (n=153; 72% Latino) | Effect in part attributed to distribution of medications at the time of appointment | ||||

| Control group (n=76; 69% Latino): patients referred but not enrolled to Project Dulce | |||||

| Teufel-Shone et al. (29) | Yuma and Santa Cruz Counties, AZ | Pre-/post- assessment | 12-week program; 10 contacts:

|

Decreased non-carbonated sweetened drink consumption (P<0.001) | Inconsistent program implementation between sites (home visits vs. group classes) |

| 72 patients with diabetes and 177 support family members | Questionnaire:

|

Education:

|

Increased joint physical activity among family members (P=0.002) | Family based; involvement of family members in program participation | |

| Social Learning Theory | Increased family support (P=0.01) | Results included those for family members; unknown effect in diabetes control | |||

| Family Social Behaviors | No different effects in knowledge, attitudes, behaviors and beliefs when comparing family members with and without diabetes | Education included information on food choices. Unclear if more in-depth nutrition information was provided | |||

| Unknown impact in health outcomes | |||||

| No control group | |||||

| Education plus support groups | |||||

| Garvin et al. (24) | King County, Seattle | Pre-/post- survey | Support groups | Overall sample improvements in:

|

No control group |

| 348 Latino, African American and Asian patients with diabetes | Lifestyle behaviors including diet & physical activity

|

Peer education classes | Only self-reported measures; social desirability bias | ||

| focus groups | Self management classes | Latino sub-ethnicity and acculturation not addressed | |||

| Care coordination | Weak dietary intake assessment methodology | ||||

| Socio-ecological model | |||||

| Lorig Chronic Disease self-management model | |||||

| Ingram et al. (25) | Farmworker community, US-Mexico border | Pre-/post- 1-y evaluation | Promotoras:

|

Improvement in:

|

Variable extent of program participation depending on participant's availability and involvement |

| 70 patients with diabetes | Clinical data (from medical records):

|

On average: 12 2-h support groups per year 25 phone calls during 1 program year |

Number of support group and advocacy contacts significantly correlated with improved glycemic control | Follow-up examinations conducted at 12±4 months | |

Questionnaire data:

|

Social support theory | Greater perceived social and family support | Questionnaires administered by promotoras | ||

| Program participation logs | No control group | ||||

| Data limited to medical chart availability | |||||

| Joshu et al. (26) | US-Mexico border; Laredo, TX | Pre-/post- evaluation at 3 and 12 months | Promotora-led self management program:

|

80.7% self-management completion rate | No Latino-specific results; patient population >95% Latino |

| 301 patients with diabetes | Clinical measures:

|

Lessons addressed knowledge, health beliefs, depression, glucose monitoring, medication management, physical activity, healthy eating, coping and goal setting | HbA1c was 0.8% lower after 3 months (P<0.001) and 0.7% lower after 12 months (P<0.001) | Incomplete clinical data | |

| Self-management outcomes self-reported as perceived achievement of goals | Optional 10-session support group post-completion of self management program | Lower LDL cholesterol after 3 and 12 months (6 and 17%, respectively; P<0.01) | No control group | ||

| Monthly promotora-health care provider meeting | 11% lower triglycerides after 12 months (P<0.05) | Unknown patient selection criteria | |||

| No changes in HDL cholesterol | Self-report of self-management outcomes | ||||

| Thompson et al. (27) | Oakland, CA | Pre-/post- evaluation of

|

Usual care (medical visits and referrals to dietitian or health educator) | Significant reductions in HbA1c after 6 months (-0.36%) and 12 months (-0.48%) | Report of subset of participants Enrolled for at least 1 year with baseline and follow up data available and at least 6 contacts with community health workers |

| 142 Spanish-speaking Latino patients (Mexican American) | Peer supporters/community health workers; weekly for the first 6 months, monthly thereafter

|

HbA1c reduction at one year attributed to reduction of 0.78% among women at 12 months (vs. +0.11% in men) no effect on blood pressure, BMI or LDL cholesterol | No control group | ||

| HbA1c > 8.0%, comorbid depression or inadequate social support | Chronic care model patient centered counseling Transtheoretical model | Potential selection bias based on willingness to participate | |||

Table 5.

Impact of non-EFNEP peer nutrition education among Latinos

| Reference | Sample | Design/Measures | Intervention/Theory | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balcazar et al. (53) |

|

Pre/post test

|

Salud para su Corazón

|

|

|

| Participatory/Social Action Research | |||||

| Elder et al. (50) |

|

|

Intervention:

|

|

|

Control group:

|

|

||||

| Goal setting Support/Encouragement theories |

|||||

| Staten LK et al. (51) |

|

|

|

Self-reported improvements in physical activity and diet

|

|

| Social support theory | |||||

| Taylor et al. (52) |

|

|

La Cocina Saludable

|

|

|

| Transtheoretical stages of change model | |||||

Analyses

Each article was assessed for the internal and external validity of the study4 as well as for the behavioral theory base (or lack thereof) of the intervention (20). The collective interpretation of study findings was the product of a consensus process involving all authors.

Results

Diabetes peer counseling

Among Latinos, implementing lifestyle modifications to follow current diabetes self-management recommendations is often challenging (21). Moreover, the lack of culturally-competent diabetes education programs that incorporate appropriate language, beliefs, values, costumes, and food preferences, hinders the efficacy of existing programs. An emerging approach to improve self-management has been the incorporation of CHWs as part of the diabetes care team. While several projects are already following this strategy, only those in which CHWs were involved in nutrition education are included herein. Trials that followed a randomized design will be reviewed first, followed by quasi-experimental interventions.

Randomized trials

Two randomized trials have been conducted targeting individuals of Puerto Rican (22) and Mexican (23) origin. Corkery et al. (22) recruited 64 Latino patients, primarily of Puerto Rican origin, newly referred to a diabetes education program delivered by a certified diabetes educator (CDE). Participants were randomized to additional support by a CHW. Regarding nutrition education, the CHW only reinforced information provided by the CDE. Program completion rate was higher among participants assigned to the CHW group vs. controls. Program completion was associated with improved knowledge and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) concentrations, and changes in self-care behaviors regardless of group assignment. In a recent trial, Lujan et al. (23) recruited 150 Mexican American patients with type 2 diabetes to evaluate a promotora-delivered intervention. Participants were randomized to usual care or a 6-month intervention consisting of eight 2-hour group classes and follow-up telephone calls following ADA curriculum guidelines. The nutrition component of the intervention only included a discussion of the food guide pyramid and reading food labels. At 6-months the mean improvements in diabetes knowledge and HbA1c were significantly greater for the intervention group. Regardless of group assignment, participants' belief about their ability to manage diabetes did not change.

These two studies indicate that CHWs are capable of promoting compliance with medical appointments as well as improving knowledge and metabolic outcomes among Latinos with diabetes. The CHWs played different roles in both studies. Corkery et al. (22) worked with bilingual/bicultural Puerto Rican CHWs living in the target community and who had previously volunteered in a diabetes clinic. CHWs attended clinic session with their assigned clients. By contrast, in Lujan's et al. study (23), the CHWs were bilingual clinic employees who received 60-hours of training in diabetes self-management. They delivered eight 2-hour participative classes, and had frequent follow-up contact telephone contact with their clients. This may explain, at least in part, the differences in results between the studies.

Quasi-experimental studies

Seven studies in which CHWs provided education for Latinos with diabetes or their families including a nutrition component had quasi-experimental designs (i.e. pre/post measurements). Of the seven, four provided support groups in addition to nutrition education.(24-27).

Project Dulce (28) combined nurse case management and a group-based peer education program which covered diabetes and its complications, the role of diet, exercise and medications, the importance of glucose self-monitoring, and discussions about experiences and beliefs about diabetes. The program enrolled 153 patients with diabetes (72% Latino) who completed 12 months of visits with a nurse case manager. Only 56% of participants attended additional peer education classes. A control group included patients not enrolled in Project Dulce (n=76, 69% Latino). Project Dulce participation resulted in a decrease in diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, all of which were significantly lower relative to the control group, and an increase in diabetes knowledge. The main limitation of this study was that the effect of peer counseling independent of nurse case management was not assessed.

La Diabetes y La Unión Familiar (29) was a 12-week education intervention designed to enhance patients' family social support and increase primary prevention behaviors among family members. Seventy-two patients with diabetes and 177 family members participated in the program, which reinforced collective esteem and efficacy as well as family communication. The nutrition education component focused on food choices and physical activity. Participation decreased non-carbonated sweetened drink intake, increased joint participation of family members in physical activity, and increased reported support for each other. No consistent change in fruits, vegetables, soft drinks, or low- and nonfat milk intake was reported. This project uniquely focused on building family-based social support. However, it is limited by inconsistent program implementation between study sites (home visits vs. group instruction), combination of results from patients and family members, and lack of assessment of health outcomes.

The Community Diabetes Education (CoDE) program (30) recruited 162 patients, predominantly of Mexican origin (78%), who received diabetes education from a CHW during 3 initial visits and quarterly assessments over 12 months. Education included glucose control and monitoring, hypoglycemia, sick day care, nutrition, diabetes complications, foot care, physical activity, smoking cessation, alcohol use, and goal setting. For the 55 patients with available data, HbA1c significantly decreased after 12 months. Body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure did not change with intervention. Unlike other interventions, there was a one-on-one CHW-patient interaction, which allowed for providing individual instruction and personalized meal planning. However, this study was limited by the lack of separate analysis for Latino participants.

Joshu et al. (26) conducted a promotora-led intervention at a Texas health center on the US-Mexico border which serves a predominately Latino population (95%). The intervention consisted of ten weekly 2.5-h self-management education classes and individual follow-up. Additional support groups were available after program completion. Of the 301 participants enrolled, 80.7% completed the self-management intervention while 24.6% also attended support groups. Relative to baseline values, HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides were lower after 12 months. Participants reported achieving the self-management goals set during the program. This study was limited by lack of a clearly described nutrition education component of the training curriculum, lack of evaluation of additional support group participation on outcomes, and lack of clinical data for a high proportion of program participants

Thompson et al. (27) evaluated a CHW-led program that included telephone-based support and classes. CHWs emphasized meal planning, exercise, blood glucose self-monitoring, and adequate medication use. CHWs also facilitated support groups, led a walking club, and taught diabetes classes. To be included, participants had to be Latino, speak Spanish, and have HbA1c > 8.0%, comorbid depression, or inadequate social support. Overall, HbA1c decreased significantly after 6 and 12 months of program participation (n=142). However, only women actually had a decrease in HbA1c after 12-months whereas HbA1c slightly increased in men. There was no significant effect on blood pressure, BMI or LDL cholesterol. These results could be biased as only the subset of participants who received at least 6 CHW contacts and who had available data at 1 year were included in the analysis.

The Campesinos Diabetes Management Program was conducted in a farm worker community on the US-Mexico Border (25). Promotoras provided support, advocacy and education for diabetes self-management (diabetes, nutrition, physical activity promotion, goal setting) through support groups and telephone and in-person contacts. The analysis included participants with available baseline and 12-month (±4 months) HbA1c data (n=70) extracted from medical records. Participation resulted in a decrease in HbA1c and systolic blood pressure, and an increase in HDL cholesterol. There were no significant effects on LDL cholesterol, triglycerides or diastolic blood pressure. HbA1c improvement was correlated with the number of support group and advocacy contacts. Study limitations included the fact that data was not available for all program participants, lack of standardization of promotora-client contact amount, and the approach of using promotoras for data collection.

The REACH 2010 project (24) recruited 348 patients with diabetes from a multiethnic population (37% Latinos). Participants, their family and friends engaged in support group discussions on healthy diet, physical activity, and coping with stressors including discrimination. Peer educators taught classes on culturally appropriate healthy eating, weight management, physical activity and diabetes. Trained facilitators offered an additional self-management class. Latinos reported significant improvements in their ability to maintain a healthy diet, eat more vegetables and low-fat foods, and eat less salt and sugar, and showed increased knowledge about diabetes care practices. Latinos showed significant improvements in their self-confidence to exercise for 30 min/day and diabetes management as well as increased ability to control their weight.

As with the randomized trials, the CHWs had diverse backgrounds and played different roles across studies. Project Dulce's CHWs were individuals with diabetes themselves and leadership skills (28). They received two training programs, including the 24 hour long project training curriculum, and they delivered education in a group setting. La Diabetes y la Unión Familiar (29) hired promotoras who worked at a community health clinic but did not have diabetes education experience and promotoras who worked in a community-based diabetes prevention program. All promotoras underwent a one-day training session and delivered their services at home as well as at diverse community settings. The Campesinos Diabetes Management Program (25) had CHWs whose main role was to facilitate social support groups. In the study by Joshu et al. (26) CHWs delivered group education, had weekly follow-up contact with their clients, and facilitated support groups. CHWs met monthly with physicians to discuss patients' diabetes self-management challenges. The CHWs recruited by Thompson et al. (27) were female patients from their target clinic with community leadership skills, who either had diabetes themselves or had a family member with diabetes. CHWs received 30-hours of training in diabetes management and the transtheoretical stages of change model. Their services included one-on-one counseling (mostly telephone-based) as well as group education. The CoDE Program (30) employed a CHW to help patients with diabetes self-management under the direct supervision of a physician through 7-hour patient contacts over a 12 month period. The CHW had a high school equivalence degree and was certified as a promotora by the State of Texas.

Summary

Overall, participation in CHW-delivered programs for diabetes self-management resulted in improved glycemic control (22, 23, 25-28, 30), lipid profile (25, 26, 28) and blood pressure (25, 28). Improvement in diabetes knowledge (23, 28), self-management behaviors (24, 26, 29) and social or family support (25, 29) were also reported. Six out of the 9 studies based their intervention on at least one behavioral change theory. However, the specific operationalization of theory constructs was generally not reported.

Studies reviewed in this section had a wide variety of designs and method of nutrition education delivery by CHWs. Several programs hired women with diabetes or with a relative with diabetes as CHWs. When reported, it appears that potential CHWs were selected based on their leadership skills and empathy towards their own community. CHWs previous paraprofessional experience, diabetes management training length and content also varied widely across studies. Only one study (30) actually reported hiring a CHW certified as such by the state where the study took place. It is important to note that the only study that reported offering to the CHW both an in-depth diabetes management training as well as behavioral change theory training is the one reporting a strong dose response relationship between the number of contacts by the CHW and the strength of the improvement in HbA1c (27). There is a need for further research to better understand the ideal background CHW characteristics and leadership attributes, intensity of contact needed between CHW and patient to attain the desired outcomes, and study training protocols.

Likewise, the optimal role for CHWs has not been carefully studied. This is an important question since the studies reviewed in this section assigned diverse roles to their CHWs ranging from social support group moderators to assisting with diabetes-self management care under the direct supervision of a physician. Once efficacy studies are conducted, cost-effectiveness studies can then be designed to assess how to formally integrate CHWs diabetes education programs that include sound nutrition education as part of the formal health care system. Additionally, carefully controlled randomized trials are needed to assess the independent effect of CHW-delivered nutrition education on glycemic control and diabetes self-management. Finally, since most of the studies reviewed included Latinos of Mexican origin, further research with other Latino subgroups is needed.

Breastfeeding promotion

The international evidence suggests that peer counselors can have a positive impact on breastfeeding behaviors in very diverse socio-cultural settings (15). Peer counselors have played a role in breastfeeding promotion in the U.S. since the 1980s (31). However, until recently few experimental or quasi-experimental studies were available to understand the impact of peer counseling on breastfeeding outcomes among Latinas.

Gill et al. (32) conducted a study in the southwestern U.S. to assess the impact of lactation support on breastfeeding outcomes among Mexican-American women. Women were recruited from a health department clinic during the second pregnancy trimester. The intervention group (n=100) received up to 2 prenatal breastfeeding counseling session from a lactation consultant. Women were called 5 times during the first 6 weeks post-partum and monthly from 3-6 months post-partum. Calls were made by either a lactation consultant or a certified lactation educator. Two of the three study lactation educators were bilingual. Upon request the study lactation consultants and/or educators visited the women in their homes. All women in the intervention group received at least one home visit. The control group received the standard breastfeeding education that could have included a breastfeeding class through a WIC clinic. Women in the intervention group were more likely to initiate breastfeeding and to continue breastfeeding at 6 months. Limitations of this study included the lack of random assignment to study group, the lack of specifics on the background of the lactation educators, and the variable extent of their involvement.

Anderson et al. (33) randomly assigned 162 women living in Connecticut to either a breastfeeding peer counseling group or a control group. Women were recruited in the prenatal care clinic of an inner-city hospital certified as Baby Friendly, and were enrolled if they were planning to breastfeed. Women who delivered a preterm infant were excluded from the study. Women in the intervention group were visited in their homes by their peer counselor up to 3 times prenatally, daily during the post-partum hospital stay, and up to 9 times postnatally. The great majority of study participants were Latinas (72 %). Exclusive breastfeeding from birth until 3 months post-partum was significantly higher in the intervention than in the control group. Consistent with this, women in the intervention group were significantly more likely to remain amenorrheic and their infants to have a lower incidence of diarrhea at 3 months. A subsequent differential response analysis showed that non-Puerto Rican Latinas and non-Hispanic black women benefited much more from the intervention than their Puerto Rican counterparts (34).

Chapman et al. (35) used an experimental design to assess the effectiveness of “Breastfeeding: Heritage and Pride”, a breastfeeding peer counseling program in Hartford, Connecticut, targeting low-income women. Participants were recruited from the prenatal care clinic of a certified Baby Friendly inner-city hospital serving a predominantly Latina clientele and were included if they were planning to breastfeed and if they delivered a healthy term infant. Women were randomly assigned to receive services from “Breastfeeding: Heritage and Pride” or to a control group. The peer counseling intervention consisted of 1 prenatal home visit, 3 post-partum home visits and telephone contact as needed. The proportion of women initiating breastfeeding was significantly higher in the intervention than in the control group. This difference was sustained at 1 and 3 months but was no longer statistically significant by 6 months. As in the study by Anderson et al. (33), the authors identified several effect modifiers (35). Women who benefited the most from this intervention were those who were multiparous, those who were uncertain about their breastfeeding intentions prenatally, as well as those who were mix feeding at 1 day post-partum.

A comparison of the last two studies shows that breastfeeding peer counseling is a highly efficacious intervention under ideal research controlled conditions (34), and also has an impact under real program conditions (35), although as expected in this instance, the impact is of lower magnitude. These studies also illustrate the importance of examining effect modifiers since participants' characteristics clearly influenced the degree of benefit received from the intervention.

Peer nutrition education

EFNEP Nutrition education

The Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) was designed as a program relying on nutrition education paraprofessionals to target the dietary habits of low-income households with children. Nutrition aides initially taught food and nutrition principles to families in their homes. By 1969 there were 5,000 paraprofessionals reaching out to 200,000 families nationwide. Nutrition aides were hired from the target communities (13). Contento's review in 1995 (13) highlighted several early studies showing that EFNEP participation is associated with improved dietary habits.

Evaluating the effectiveness of EFNEP at improving nutrition-related behaviors has been the basis of several national reports, statewide and local research studies, and cost-benefit analyses. National evaluations of EFNEP have been conducted since 1999 to assess and monitor the impact of this program on the dietary intake, nutrition knowledge, and food behaviors of low-income participants in the United States. Consistent with most national findings, randomized control trials and quasi-experimental studies examining the impact of EFNEP on nutrition-related outcomes among local populations have demonstrated improved dietary intake (36), nutrition knowledge (37-39), food practices (37-39), and food insecurity (40, 41) with some improvements being observed a year after graduation from the program (37, 38).

Cost-benefit studies have also emerged from selected states to determine the indirect and direct benefits of EFNEP on health care costs and work productivity.(41-45) Findings from these studies support EFNEP as a program that prevents diet-related illnesses and diseases, reporting benefit-cost ratios anywhere from approximately 3 to 1 (44) and 17 to 1 (43). In fact, a few research studies have documented economic benefits of EFNEP including program-related improvements in employment (37, 38) and education (38).

Only a few studies have examined the possible effect modification of race/ethnicity on EFNEP's nutrition-related outcomes. This is relevant for this review as 36% of EFNEP participants are Latino. Townsend et al. (39) conducted the first randomized control study evaluating the impact of the EFNEP on nutrition-related behaviors among low-income youth. This study, conducted in 10 counties in California, included a multi-ethnic sample of 5111 children (43% Latino) from 229 youth groups. Children randomized to the intervention group received 7 EFNEP education lessons (within 6-8 weeks) delivered by their respective group leaders (mostly teachers). Those in the control group did not receive these lessons until after 8 weeks. Overall, children in the intervention group had improved outcomes in their nutrition knowledge, food preparation and safety skills, selection of foods, and eating varieties of foods. Townsend et al. found that Latino youth that received 7 nutrition education lessons had significantly greater improvements in their nutrition knowledge and food preparation skills/food safety practices compared to those who did not receive the education. However, among Latino youth, no significant improvements between intervention and control groups were found for two other indicators, reflecting dietary variety and selection of nutritious foods. Further studies are needed to determine whether ethnicity/race modifies the effect of EFNEP.

Results from a multiethnic study conducted by Dollahite et al. (40) reported specific benefits of the EFNEP program on food insecurity among Latino adults. Participation in the New York State EFNEP during 1999-2001 was found to ameliorate food insecurity among Latinos, measured by the single question “how often do you run out of food before the end of the month?”. After controlling for socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, Latinos' food insecurity scores improved from entry to exit in EFNEP compared to Asians. Non-Latino white and non-Latino black individuals also experienced improvements in food insecurity compared to Asians suggesting that EFNEP nutrition education provides most racial/ethnic groups with tools that enable them to ameliorate their food insecurity level.

A cost-benefit analysis was conducted by Block Joy et al. (45) among a sub-sample of participants enrolled in EFNEP in California in 1998. Over 60% of families participating in EFNEP in California at that time were Latino. Using stringent criteria replicated from other studies (43), the authors first determined that 2-28% of EFNEP graduates practiced ‘optimal nutrition behaviors’ to prevent/protect against specific illnesses/chronic diseases (i.e. colorectal cancer, foodborne illness, heart disease, obesity, osteoporosis, stroke/hypertension, type 2 diabetes). Cost-benefit analyses were conducted to evaluate the impact of the EFNEP program on reducing medical costs. Overall, EFNEP resulted in a savings of $14.67 in medical care costs per every $1.00 spent. The authors also determined that EFNEP nutrition education saved in long-term medical costs. For EFNEP graduates who maintained ‘optimal nutrition behavior’ over 5 years, California saved at least $3.67 dollars per person in future medical treatment costs.

These studies document several benefits of EFNEP nutrition education for Latinos. Results are consistent with other EFNEP studies including non-Latino participants. Thus, EFNEP benefits may not be race/ethnic specific but rather are experienced by all participants.

FSNE nutrition education

The USDA Food Stamp Program (FSP) is the largest food assistance program in the world. In FY 2006 it served 27 million people at a cost of $30 billion federal dollars. The FSP transfers cash to households in an electronic debit card that can be used to purchase foods at supermarkets, food shops, and even some farmers markets. The FSP has very few restrictions regarding the types of foods that can be bought, thus nutrition education may be essential for improving food shopping decisions of program recipients. The Food Stamp Nutrition Education (FSNE) Program officially started in 1981 through an act of Congress seeking to provide nutrition education to food stamp recipients using approaches developed by EFNEP and other programs and following a $1:$1 federal:state match funding mechanism. By FY1992 only 7 states were participating receiving a total of $661,000 in federal funds. Since then the program has grown exponentially and it now includes 52 states and territories that receive about $275 million in federal funds. FSNE program content varies from state to state and includes one-on-one and small group education as well as food and nutrition social marketing campaigns (14). Addressing the effectiveness of this program is very relevant to this review, as FSNE targets low-income Latinos in many states and often involves the use of nutrition education paraprofessionals. Even though Latino specific FSNE programs exist (46) and conceptual impact evaluation efforts are underway (47-49), no published studies met our inclusion criteria.

Demonstration programs

We identified 4 additional nutrition education demonstration programs involving community health workers, only one of which was a randomized controlled trial. Elder et al. (50), conducted a randomized controlled trial among 357 Spanish speaking Latinas to examine the 1 year impact of behavior change approaches to reduce dietary fat and to increase fiber intakes. During the 14-week program, participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: 1) promotoras-led intervention group, involving weekly home visits or telephone contacts plus nutrition tailored newsletters with homework assignments mailed weekly to participants' homes, 2) tailored intervention group, involving weekly mailing of the same newsletters used with the promotora group; and 3) control group, involving mailing of 12 off-the shelf materials covering the same modules and content as the newsletters. Intervention impact was assessed at baseline, 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post-intervention. Outcomes were based on 24-hour dietary recalls and anthropometric measures. At 12 weeks, participants in the promotora-led group had significantly lower intakes of total and saturated fat, glucose, and fructose than those in the tailored group and significantly lower intakes of energy and total carbohydrates than those in the control group. By 12 months, between-group dietary intake differences were no longer detected suggesting that interpersonal contact with the promotoras is important in order to achieve long-term success.

Pasos Adelante (Steps Forward), a 12-week program facilitated by CHWs, is a revised curriculum of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute cardiovascular disease prevention program, Su Corazón, Su Vida (Your Heart, Your Life). The impact of this intervention was assessed in Arizona using pre and post-curriculum questionnaires of self-reported measures of physical activity and dietary patterns in 216 participants who completed the program (51). Program participation was associated with increased physical activity, lower soft drink consumption, and increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. However, the benefit was stronger in one of the two counties included in the study.

La Cocina Saludable (The Healthy Kitchen) was implemented in 10 southern Colorado counties to improve nutrition related knowledge, skills, and behaviors among low-income Latina mothers of preschool children based on the transtheoretical model and assessing scale reliability (52). Latina grandmothers and grandmother figures (Abuelas) were selected as peer educators to deliver 5 nutrition education sessions. Peer educators participated in a two-day training program. Program evaluation was based on 337 participants. Tests were administered before and after each class to assess immediate changes in knowledge, skills and self-reported behaviors and results were compared to a control group of 52 participants. A survey was mailed at 6 months post-intervention to examine benefit retention. Return rate at 6 months was only 24% and these results were not compared to the control group. Significant improvements were documented for self-reported nutrition, diet and food safety knowledge/skills and these improvements were retained at 6 months. Study limitations included very low follow-up survey response rate, lack of comparison of follow-up intervention group data with controls, all the measures were self-reported, and no in-depth dietary assessment methods used.

Balcazar et al. (53, 54) evaluated the effectiveness of the Salud para Su Corazón (Health for your Heart) National Council of La Raza (SPSC-NCLR) Promotora Outreach Program. The goal of the program was to improve heart-healthy behaviors among 223 Latino families participating at 7 sites across the U.S. The intervention consisted of 7 two-hour lessons that took place during the first half of a 6-month intervention plus home visits or telephone contacts to reinforce the educational activities learned in the program. Participating families completed a 35-item survey on heart-healthy behaviors before and after the sessions. The program was associated with improved overall heart-healthy score that included physical activity, weight, and cholesterol, fat, salt and sodium intake. The greatest improvement was observed on practices related to dietary cholesterol and fat. This study was limited by the lack of a control group, the fact that all the measures were self-reported, and lack of in-depth measures of dietary intake.

Summary

Overall, these nutrition education demonstration studies suggest that peer education has the potential to change dietary behaviors among Latinos. However, several limitations to the studies deserve consideration. Most studies failed to address important factors in their analysis, such as acculturation, which can play an important role in the effect of nutrition education interventions (46). Moreover, the majority of the data in these studies was self-reported, thus the possibility of social desirability bias cannot be excluded.

Consistent with the previous sections of this review, the characteristics of CHWs as well as their training and roles varied widely across studies. Salud Para su Corazón (53, 54) worked with promotoras already employed by the community-based organizations (CBOs) participating in the study. The promotoras' training program included 50-hours of curriculum exposure, participation in a 2-day national promotoras conference, and monthly updates. The promotoras delivered their services mostly through group education in the CBOs, but were also allowed to have contact with their clients at their homes or by telephone. La Cocina Saludable program (52) was implemented by senior Latinas who were grandmothers or abuelas. They were recruited through job advertisements as well as health and social agencies referrals. The vast majority of them were females and most of them older than 40. Only 31% had a bachelor's degree, 64% were fluent in Spanish, and over three-quarters had previous teaching and community services experience. Abuela educators were trained with the same curriculums that they were going to use with their clients. A strength of these studies (52-54) is that they both documented the effectiveness of trainings at improving promotoras' knowledge and skills. The study Pasos Adelante (51) worked with promotoras employed by two different community agencies who received six hours of manual training although several of them had received prior training on heart disease prevention. Senior and junior promotoras worked in pairs and they delivered group lessons to their clients and facilitated walking clubs at diverse community settings. Only 1 out of the 11 promotoras only was a male. In the trial by Elder et al. (50) the promotora's role was to work with clients in their homes or via telephone around themes highlighted by the tailored newsletters and homework assignments.

Conclusions

This systematic review of experimental and quasi-experimental studies provides evidence that peer nutrition education has a positive influence on diabetes self-management, breastfeeding outcomes, as well as on general nutrition knowledge and dietary intake behaviors among Latinos in the U.S. These findings are consistent with studies conducted with non-Latino white and black individuals. This suggests that it is important to formally incorporate peer nutrition educators as part of the CHWs framework and to integrate them as part of the public health and clinical health care management in the U.S. This strategy could contribute to addressing the health disparities that seriously affect Latinos and other minority groups.

There is a need for prospective experimental and controlled quasi-experimental studies to further examine the impact of peer nutrition education among Latinos. The majority of studies reviewed based their intervention on at least one behavioral change theory. However, hardly any study provided specifics on the operationalization of theory constructs. Likewise, hardly any of the interventions reviewed addressed the influence of acculturation as an effect modifier. With few exceptions, there was a consistent lack of information on nutrition knowledge, self-efficacy and behavioral scales' reliability across studies. Thus, it is imperative that future studies are designed based on sound behavioral change theories that take into account the major role of acculturation in shaping lifestyle behaviors and health outcomes in Latino communities (46). It is essential to report the reliability of scales to further advance the knowledge in this field. When experimental studies are not possible to conduct, strong quasi-experimental study designs are very useful. However, these studies should always aim to include a comparison group. Unfortunately this was not the case for most of the quasi-experimental studies included in this review.

A surprising finding from this review is that we could not identify any experimental or quasi-experimental study assessing the impact of FSNE among Latinos even through this major program has been in place for over a decade now. Many states include peer nutrition educators as part for their FSNE delivery strategies. Thus, this represents a major gap in knowledge. An outcome evaluation strategy similar to EFNEP's behavioral check list is being proposed (39, 47-49). However, no specific recommendations have been made regarding identification of impact of peer educators. Also, Spanish-speaking Latinos are not being targeted during initial development of the evaluation strategy. This is important to address as there are FSNE programs devoted to addressing the nutrition education needs of mostly Spanish speaking audiences (55).

Future studies should move beyond assessing self-reported behaviors and include objective measures such as anthropometry, biomarkers, and blood pressure. They should also have enough statistical power to compare diverse Latino subgroups. Finally, there is a need to better understand how nutrition peer educators can be formally incorporated into the healthcare system within the Chronic Health Care's community health worker framework. Operational research is needed to identify the characteristics that peer educators should have, the general and specific training that they should receive, the client loads and dosage (i.e., frequency and amount of contact needed between needed peer educator and client), the educational approach (e.g., individual, small group, large group) and setting (home, community sites). Studies published thus far vary widely in these parameters and no clear patterns have emerged to make objective process recommendations. This operational research gap is worrisome as Dickin et al. (56) have shown that the characteristics of peer nutrition educators and the work context are significant determinants of nutrition education program effectiveness.

Table 3.

Impact of peer counseling on breastfeeding outcomes among Latinas

| Reference | Sample | Design/Measures | Intervention/Theory | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (33) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Chapman et al (35) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gill et al. (32) |

|

|

|

Women in the intervention group were more likely to initiate breastfeeding (82.3% vs. 67.1%) and to continue breastfeeding at 6 months (43% vs. 21%). |

|

Table 4.

Impact of EFNEP education among Latinas

| Reference | Sample | Design/Measures | Intervention/Theory | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block Joy et al. (45) |

|

|

|

Participants achieving optimal nutrition behavior

|

Strength: study replicated techniques and methodology used in Virginia. |

Outcomes (prevention against):

|

Overall benefit-cost ratio

|

Limitation: Although the initial sample was predominately Latino, it is unknown whether the sample used for the analyses was also predominately Latino as only those participants exhibiting optimal nutrition behaviors were included in the final analyses | |||

Sensitivity analyses ($)

|

|||||

| Dollahite et al. (40) |

|

|

|

|

Limitations:

|

| Townsend et al. (39) |

|

|

|

|

Limitations:

|

Measured as those EFNEP graduates who achieved the greatest benefit (a score of 4 or more) on all dietary practices criteria because they could be attributed to the nutrition education.

Leaders consisted of classroom teachers, afternoon program staff, summer camp staff, community agency personnel, and teenagers.

Acknowledgments

The development of this article was funded by the Connecticut Center of Excellence for Eliminating Health Disparities among Latinos (CEHDL) (NIH-National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant # P20MD001765). This work is dedicated to all our Latino communities, for their past, present and future contributions.

Footnotes

While the terms Latino and Hispanic are often times used interchangeably in the literature, the authors will refer to this ethnic group solely as Latino.

In the area of nutrition education, the term peer educator is commonly used. In the public health literature the term community health worker has become the term of choice, although other terms such as promotora are also employed. When describing studies in this review we use the term as reported in the original article.

A Cronbach alpha of at least 0.85 was establish a priori as criteria for assessing internal validity of scales, Reliability was assessed based on intracorrelation coefficients of repeated scale applications using preset criteria of an r of at least 0.35 and a p value <0.05.

Internal and external validity were assessed following the guidelines recommended by Jekel et al.20

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau. The Hispanic Population in the United States, 2006 March CPS. [February 10, 2008]; Available at www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hispanic/ho06.html.

- 2.LaVeist TA. Minority Populations and Health: An Introduction to Health Disparities in the United States. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Ross Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Household Food Security in the United States, 2006. [December, 2007];Economic Research Report Number 49. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/ERR49/ERR49.pdf.

- 4.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. National Diabetes statistics fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2005. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Insitute of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, Eberhardt MS, Flegal KM, Engelgau MM, Saydah SH, Williams DE, Geiss LS, Gregg EW. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1263–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Carter-Pokras O, Andersen R. Acculturation and leisure-time physical inactivity in Mexican American adults: results from NHANES III, 1988-1994. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1254–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2005 update. Dallas, Texas: American Heart Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witmer A, Seifer SD, Finocchio L, Leslie J, O'Neil EH. Community health workers: integral members of the health care work force. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1055–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ro M, Treadwell H, Northridge M. Community health workers and community voices: Promoting good health. A Community Voices Publication. National Center for Primary Care at Morehouse School of Medicine. [February 13, 2008];2003 October; (2nd Printing, July 2004). Available at: http://www.communityvoices.org/Uploads/CHW_FINAL_00108_00042.pdf.

- 11.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness. Effective Clin Pract. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez LM, Martinez J. Community health workers: social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:11–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contento I. Nutrition education for adults. J Nutr Educ. 1995;27:312–28. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landers PS. The Food Stamp Program: history, nutrition education, and impact. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1945–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewin SA, Dick J, Pond P, Zwarenstein M, Aja G, van Wyk B, Bosch-Capblanch X, Patrick M. Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metzger N, Parker L. Utilizing community health advisors in diabetes care management. In: Zazworsky D, Bolin J, Gaubeca V, editors. Handbook of Diabetes Management. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 247–56. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson S. Peer-led approaches to dietary change: report of the Food Standards Agency seminar held on 19 July 2006. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:980–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007787773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Looker A, Long P, Hamilton L, Shannon B. A nutrition education model for training and updating EFNEP aides. Home Econ Res J. 1983;11:392–402. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadwallader AA, Olson CM. Use of a breastfeeding intervention by nutrition paraprofessionals. J Nutr Educ. 1986;18:117–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jekel JF, Katz DL, Elmore JG, Wild DMG. Common research designs used in epidemiology. Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Preventive Medicine. Third. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown AF, Gerzoff RB, Karter AJ, Gregg E, Safford M, Waitzfelder B, Beckles GLA, Brusuelas R, Mangione CM. Health Behaviors and Quality of Care Among Latinos With Diabetes in Managed Care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1694–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corkery E, Palmer C, Foley ME, Schechter CB, Frisher L, Roman SH. Effect of a bicultural community health worker on completion of diabetes education in a Hispanic population. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:254–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lujan J, Ostwald SK, Ortiz M. Promotora diabetes intervention for Mexican Americans. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:660–70. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garvin CC, Cheadle A, Chrisman N, Chen R, Brunson E. A community-based approach to diabetes control in multiple cultural groups. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:S83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingram M, Torres E, Redondo F, Bradford G, Wang C, O'Toole ML. The impact of promotoras on social support and glycemic control among members of a farmworker community on the US-Mexico border. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33 6:172S–8S. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshu CE, Rangel L, Garcia O, Brownson CA, O'Toole ML. Integration of a promotora-led self-management program into a system of care. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33 6:151S–8S. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson JR, Horton C, Flores C. Advancing diabetes self-management in the Mexican American population: a community health worker model in a primary care setting. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33 6:159S–65S. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philis-Tsimikas A, Walker C, Rivard L, Talavera G, Reimann JOF, Salmon M, Araujo R. Improvement in diabetes care of underinsured patients enrolled in Project Dulce: A community-based, culturally appropriate, nurse case management and peer education diabetes care model. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:110–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teufel-Shone NI, Drummond R, Rawiel U. Developing and adapting a family-based diabetes program at the U.S.-Mexico border. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Culica D, Walton JW, Prezio EA. CoDE: Community Diabetes Education for uninsured Mexican Americans. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2007;20:111–7. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2007.11928263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossman B. Breastfeeding peer counselors in the United States: helping to build a culture and tradition of breastfeeding. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52:631–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gill SL, Reifsnider E, Lucke JF. Effects of support on the initiation and duration of breastfeeding. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29:708–23. doi: 10.1177/0193945906297376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson AK, Damio G, Young S, Chapman DJ, Perez-Escamilla R. A randomized trial assessing the efficacy of peer counseling on exclusive breastfeeding in a predominantly Latina low-income community. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:836–41. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.9.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson AK, Damio G, Chapman DJ, Perez-Escamilla R. Differential response to an exclusive breastfeeding peer counseling intervention: the role of ethnicity. J Hum Lact. 2007;23:16–23. doi: 10.1177/0890334406297182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapman DJ, Damio G, Young S, Perez-Escamilla R. Effectiveness of breastfeeding peer counseling in a low-income, predominantly Latina population: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:897–902. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luccia B, Kunkel M, Cason K. Dietary changes by Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) Graduates are independent of program delivery method. J Ext. 2003;41 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnold CG, Sobal J. Food practices and nutrition knowledge after graduation from the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2000;32:130–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brink M, Sobal J. Retention of nutrition knowledge and practices among adult EFNEP participants. J Nutr Educ Behav. 1994;26:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Townsend MS, Johns M, Shilts MK, Farfan-Ramirez L. Evaluation of a USDA nutrition education program for low-income youth. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dollahite J, Olson C, Scott-Pierce M. The impact of nutrition education on food insecurity among low-income participants in EFNEP. Family and Consumer Science Research Journal. 2003;32:127–39. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burney J, Haughton B. EFNEP: a nutrition education program that demonstrates cost-benefit. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wessman C, Betterley C, Jensen H. Center for Agricultural and Rural Development (CARD) at Iowa State University. 2000. An evaluation of the costs and benefits of Iowa's Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP). Center for Agricultural and Rural Development (CARD) Publications 01-sr93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajgopal R, Cox RH, Lambur M, Lewis EC. Cost-benefit analysis indicates the positive economic benefits of the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program related to chronic disease prevention. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:26–37. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuster E, Zimmerman Z, Engle M, Smiley J, Syversen E, Murray J. Investing in Oregon's Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP): documenting costs and benefits. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2003;35:200–6. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Block Joy A, Pradhan V, Goldman G. Cost-benefit analysis conducted for nutrition education in California. California Agriculture. 2006;60:185–91. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perez-Escamilla R, Putnik P. The role of acculturation in nutrition, lifestyle, and incidence of type 2 diabetes among Latinos. J Nutr. 2007;137:860–70. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guthrie JF, Stommes E, Voichick J. Evaluating food stamp nutrition education: issues and opportunities. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor-Powell E. Evaluating food stamp nutrition education: a view from the field of program evaluation. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38:12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Townsend MS. Evaluating food stamp nutrition education: process for development and validation of evaluation measures. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell NR, Arredondo EM, Slymen DJ, Baquero B, Zive M, Ganiats TG, Engelberg M. Long-term effects of a communication intervention for Spanish-dominant Latinas. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staten LK, Scheu LL, Bronson D, Pena V, Elenes J. Pasos Adelante: the effectiveness of a community-based chronic disease prevention program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor T, Serrano E, Anderson J, Kendall P. Knowledge, skills, and behavior improvements on peer educators and low-income Hispanic participants after a stage of change-based bilingual nutrition education program. J Community Health. 2000;25:241–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1005160216289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balcazar H, Alvarado M, Hollen ML, Gonzalez-Cruz Y, Pedregon V. Evaluation of Salud Para Su Corazon (Health for your Heart) -- National Council of La Raza Promotora Outreach Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balcazar H, Alvarado M, Hollen ML, Gonzalez-Cruz Y, Hughes O, Vazquez E, Lykens K. Salud Para Su Corazon-NCLR: A comprehensive Promotora outreach program to promote heart-healthy behaviors among Hispanics. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7:68–77. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pérez-Escamilla R, Damio G, Himmelgreen D, González A, Segura-Pérez S, Bermúdez-Millán A. Translating knowledge into community nutrition programs: Lessons learned from the Connecticut Family Nutrition Program for Infants, Toddlers, and Children. In: Pandalai, editor. Research Developments in Nutrition. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2002. pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickin KL, Dollahite JS, Habicht JP. Nutrition behavior change among EFNEP participants is higher at sites that are well managed and whose front-line nutrition educators value the program. J Nutr. 2005;135:2199–205. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.9.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gilmer TP, Philis-Tsimikas A, Walker C. Outcomes of Project Dulce: a culturally specific diabetes management program. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:817–22. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richert ML, Webb AJ, Morse NA, O'Toole ML, Brownson CA. Move More Diabetes: using Lay Health Educators to support physical activity in a community-based chronic disease self-management program. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33 6:179S–84S. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arlotti JP, Cottrell BH, Lee SH, Curtin JJ. Breastfeeding among low-income women with and without peer support. J Community Health Nurs. 1998;15:163–78. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1503_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kistin N, Abramson R, Dublin P. Effect of peer counselors on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and duration among low-income urban women. J Hum Lact. 1994;10:11–5. doi: 10.1177/089033449401000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pugh LC, Milligan RA, Brown LP. The breastfeeding support team for low-income, predominantly-minority women: a pilot intervention study. Health Care Women Int. 2001;22:501–15. doi: 10.1080/073993301317094317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pugh LC, Milligan RA, Frick KD, Spatz D, Bronner Y. Breastfeeding duration, costs, and benefits of a support program for low-income breastfeeding women. Birth. 2002;29:95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schafer E, Vogel MK, Viegas S, Hausafus C. Volunteer peer counselors increase breastfeeding duration among rural low-income women. Birth. 1998;25:101–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1998.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolfberg AJ, Michels KB, Shields W, O'Campo P, Bronner Y, Bienstock J. Dads as breastfeeding advocates: results from a randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:708–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merewood A, Chamberlain LB, Cook JT, Philipp BL, Malone K, Bauchner H. The effect of peer counselors on breastfeeding rates in the neonatal intensive care unit: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:681–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cason KL, Cox RH, Wenrich TR, Poole KP, Burney JL. Food stamp and non-food stamp program participants show similarly positive change with nutrition education. Top Clin Nutr. 2004;19:136–47. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hartman TJ, McCarthy PR, Park RJ, Schuster E, Kushi LH. Results of a community-based low-literacy nutrition education program. J Community Health. 1997;22:325–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1025123519974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dollahite J, Scott-Pierce M. Outcomes of individual vs. group instruction in EFNEP. J Ext. 2003;41 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Birnbaum AS, Lytle LA, Story M, Perry CL, Murray DM. Are differences in exposure to a multicomponent school-based intervention associated with varying dietary outcomes in adolescents? Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:427–43. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Damron D, Langenberg P, Anliker J, Ballesteros M, Feldman R, Havas S. Factors associated with attendance in a voluntary nutrition education program. Am J Health Promot. 1999;13:268–75. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-13.5.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]