Abstract

Oligodendrocytes in CNS are linked to astrocytes by heterotypic gap junctions composed of Cx32 and Cx47 in oligodendrocytes and Cx30 and Cx43 in astrocytes. These gap junctions also harbour regulatory proteins, including ZO-1 and ZONAB. Here, we investigated the localization of multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1) at these gap junctions and examined accessory proteins and connexins associated with oligodendrocytes in Cx47 knockout mice. In every CNS region tested, punctate immunolabelling for MUPP1 was found on all oligodendrocyte somata in wild-type mice. These MUPP1-positive puncta were co-localized with punctate labelling for oligodendrocytic Cx32 or Cx47, and with astrocytic Cx30 or Cx43 at oligodendrocyte-astrocyte (O/A) gap junctions, but were not found at astrocyte-astrocyte gap junctions. In Cx47 knockout mice, immunolabelling of MUPP1 and ZONAB was absent on oligodendrocytes, whereas some ZO-1-positive puncta remained. In Cx32 knockout mice, MUPP1 and ZONAB persisted at O/A gap junctions. The absence of Cx47 in Cx47 knockout mice was accompanied by a total loss of punctate labelling for Cx30, Cx32 and Cx43 on oligodendrocyte somata, and by a dramatic increase of immunolabelling for Cx32 along myelinated fibers. These results demonstrate MUPP1 at O/A gap junctions and Cx47-dependent targeting of connexins to the plasma membranes of oligodendrocyte somata. Further, it appears that deficits in myelination reported in Cx47 knockout mice may arise not only from a loss of Cx47, but also from the accompanied loss of gap junctions and their regulatory proteins at oligodendrocyte somata, and that loss of Cx47 may be partly compensated by elevated levels of Cx32 along myelinated fibers.

Keywords: glial cells, myelin, scaffolding proteins, immunohistochemistry, spatial buffering

Introduction

Efflux of potassium ions from neurons during neuronal activity is accumulated by astrocytes and thought to be redistributed to areas of neuronal inactivity or to nearby capillaries via a process termed K+ spatial buffering (Orkland et al., 1966). This redistribution is considered to be mediated by the cell-to-cell flow of ions through an extensive network of gap junctions, which are composed of connexin (Cx) proteins that form channels linking the cytoplasmic compartments of adjoining cells (Bruzzone & Ressot, 1997; Rouach et al., 2002; Theis et al., 2005). Since its inception, support for the K+ spatial buffering concept has been obtained from studies in a variety of CNS regions (Connors et al., 1982; Newman, 1986; Holthoff & Witte, 2000; Ransom et al., 2000; Kofuji & Newman, 2004; Wallraff et al., 2006). However, direct evidence for a key role of glial gap junctions in this process has been slow to emerge, due in part to the apparent complexity of the gap junctionally coupled glial syncytium. Indeed, macroglial cells collectively express among the largest repertoire of connexins of any cell type, with Cx30 and Cx43 found in astrocytes, and Cx29, Cx32 and Cx47 in oligodendrocytes (Scherer et al., 1995; Li et al., 1997; Nagy & Rash, 2000; Altevogt et al., 2002; Altevogt & Paul, 2004; Nagy et al., 2004; Kleopa et al., 2004; Orthmann-Murphy et al., 2008). Expression of Cx26 protein has also been reported in astrocytes (Nagy et al., 2001; Altevogt & Paul, 2004), although this remains controversial as Cx26 promoter driven LacZ gene expression was not detected in these cells (Filippov et al., 2003). Furthermore, glial cells form gap junctions at a bewildering array of subcellular locations, with multiple connexins contributing to these gap junctions at various sites in the glial syncytium. Homologous intercellular as well as autologous astrocyte-astrocyte gap junctions formed by various combinations of Cx26, Cx30 and Cx43 link astrocyte processes at their ensheathments of neuronal and vascular elements (Mugnaini, 1986; Yamamoto et al., 1990; Wolburg & Rohlmann, 1995). Heterologous oligodendrocyte-astrocyte (O/A) gap junctions formed by Cx32 and Cx47 in oligodendrocytes with Cx26, Cx30 and Cx43 in astrocytes occur at oligodendrocyte somata and their processes, at the outer surface of internodal myelin, and at paranodal myelin. It has been concluded that oligodendrocytes do not form gap junctions with each other, but do form autologous gap junctions composed of Cx32 within uncompacted myelin at Schmidt-Lanterman incisures and paranodal loops (Rash et al., 1997; Rash et al., 2001; Kamazawa et al., 2005). Studies of Cx29 have so far indicated its absence in O/A gap junctions (Nagy et al., 2003a; Kleopa et al., 2004), but this requires further analysis by ultrastructural approaches. Despite extensive ultrastructural documentation of O/A gap junctions and immuohistochemical characterization of their constituent connexins, it is noteworthy that only a few reports have characterized functional O/A gap junctional coupling between oligodendrocytes and astrocytes in studies of these cell in vitro (Kettenmann & Ransom, 1988; Ransom & Kettenmann, 1990; Venance et al., 1995).

The structural organization and coupling partner relationships of glial connexins and the functional contribution of each to K+ spatial buffering has been the subject of intense investigations. In particular, recent studies have reported severe myelination deficits in mice with double knockout (KO) of Cx32 and Cx47, but only mild deficits in mice with either Cx32 or Cx47 KO (Sutor et al., 2000; Menichella et al., 2003, 2006; Odermatt et al., 2003), suggesting functional redundancy of gap junctions within the glial syncytium and/or compensation for the loss of one connexin by another. Previously, we and others found that gene deletion of Cx32 was accompanied by a loss of its astrocytic coupling partner Cx30 on oligodendrocyte somata, without obvious alterations in any of the other glial connexins (Nagy et al., 2003b; Altevogt & Paul, 2004), consistent with proposed Cx30/Cx32 coupling at O/A gap junctions and with possible functional compensation by the remaining glial connexins.

In addition, we have identified two gap junction-associated proteins that may serve scaffolding and/or regulatory roles at glial gap junctions, namely zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and the transcription factor ZO-1-associated nucleic acid-binding protein (ZONAB) (Li et al., 2004; Penes et al., 2005). In the present report, we identified the association of another protein with O/A gap junctions, the multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1), which contains thirteen PDZ domains (Ullmer et al., 1998), is often co-localized with ZO-1 at tight junctions in various cell types (Ebnet et al., 2004), and has been genetically linked to predisposition for drug dependence (Shirley et al., 2004). Further, in order to better understand the physiological basis for the reported phenotype of Cx47 KO mice, we used immunohistochemical approaches to examine the impact that Cx47 gene deletion has on the association of MUPP1, ZO-1 and ZONAB with O/A gap junctions, and to determine how loss of Cx47 affects the deployment of astrocytic Cx30, Cx32 and Cx43.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and animals

Antibodies, their source, conditions under which they were used in this study and references describing their specificity characteristic are presented in Table 1. A newly produced polyclonal antibody against MUPP1 was generated against a fourteen amino acid peptide corresponding to a sequence within the C-terminus region of MUPP1. The antibody was affinity-purified and designated Ab42-2700. Most of the antibodies used were obtained from Invitrogen/Zymed Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Monoclonal anti-2,′3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNPase) was obtained from Sternberger Monoclonals (Baltimore, MD, USA) and polyclonal anti-Cx43 designated 18A was generously provided by E.L. Hertzberg (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York). A total of twenty normal male CD1 mice, five wild-type adult male C57BL/6 mice, five Cx47 KO adult male C57BL/6 mice, three Cx32 KO adult male C57BL/6 mice and three adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were used in this study. The Cx32 KO mice (Cx32(-/-)) and Cx47 KO mice (Cx47EGFP(-/-)) were generated as previously described (Nelles et al., 1996; Odermatt et al., 2003). Animals were utilized according to approved protocols by the Central Animal Care Committee of University of Manitoba, with minimization of the numbers of animals used.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for western blotting and immunohistochemistry

| Antibody | Type | Species | Epitope*; Designation | Dilution | Source; Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cx30 | polyclonal | rabbit | c-terminus; 71-2200 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Nagy et al., 1999 |

| Cx30 | monoclonal | mouse | c-terminus; 33-2500 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Rash et al., 2001 |

| Cx32 | polyclonal | rabbit | c-terminus; 34-5700 | 3 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Nagy et al., 2003b |

| Cx32 | monoclonal | mouse | c-terminus; 35-8900 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Nagy et al., 2003b |

| Cx43 | monoclonal | mouse | c-terminus; 35-5000 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Nagy et al., 2003b |

| Cx43 | polyclonal | rabbit | aa 346-363; 18A | 1:1000 | Yamamoto et al., 1990a |

| Cx47 | monoclonal | mouse | c-terminus; 37-4500 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; present study |

| Cx47 | polyclonal | rabbit | c-terminus; 36-4700 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Li et al., 2004 |

| ZO-1 | polyclonal | rabbit | aa463-1109; 61-7300 | 3 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Penes et al., 2005 |

| MUPP1 | polyclonal | rabbit | c-terminus; 42-2700 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; present study |

| ZONAB | polyclonal | rabbit | c-terminus; 40-2800 | 2 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed; Penes et al., 2005 |

| CNPase | monoclonal | mouse | whole protein | 1:5000 | Sternberger Monoclonals |

| EGFP | polyclonal | rabbit | whole protein | 3 μg/mL | Invitrogen/Zymed |

aa, amino acids

Light microscopic immunofluorescence

Procedures for immunohistochemistry were performed according to standard protocols as we described previously (Penes et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004). Briefly, mice deeply anaesthetized with equithesin (3 mL/kg) were transcardially perfused with 3 mL of ice-cold 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.9% NaCl, 0.1 sodium nitrite and 1 unit/mL heparin, and then with 40 ml of cold 0.16 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.6, containing 1% formaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid. The fixative was flushed from animals by perfusion with 10 mL of ice-cold 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 10% sucrose. Tissue sections cut on a cryostat at 10 μm thickness were washed for 20 min in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1.5% sodium chloride (TBS) and 0.3% Triton X-100 (TBSTr). For double immunofluorescence labelling, sections were incubated simultaneously with two primary antibodies (a rabbit polyclonal and mouse monoclonal) for 24 h at 4°C, then washed for 1 h in TBSTr, and incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature simultaneously with appropriate combinations of secondary antibodies, which included: FITC-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG diluted 1:100 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG diluted 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), Alexa Flour 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1:1000 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) and Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). All antibodies were diluted in TBSTr containing 5% normal goat or normal donkey serum. After secondary antibody incubations, sections were washed in TBSTr for 20 min, then in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 for 30 min, and covered with antifade medium and coverslipped. Control procedures included omission of one of the primary antibodies with inclusion of each of the secondary antibodies to establish absence of inappropriate cross-reactions between primary and secondary antibodies or between different combinations of secondary antibodies. Conventional and confocal immunofluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss Axioskop2 fluorescence microscope using Axiovision 3.0 software (Carl Zeiss Canada, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and on an Olympus Fluoview IX70 confocal microscope using Olympus Fluoview software (Olympus Canada, Inc., Markham, ON, Canada), and assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA), CorelDRAW Graphics Suite 12 (Corel Corporation, Ottawa, ON, Canada), and Northern Eclipse software (Empix Imaging, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

In Cx47 KO mice, the coding region of Cx47 was replaced by EGFP as a reporter for Cx47 expression (Odermatt et al., 2003). Nevertheless, we used the oligodendrocyte marker CNPase in combination with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody to identify oligodendrocytes in the Cx47 KO mice in order to parallel similar cell identification in wild-type mice lacking EGFP expression in oligodendrocytes. This approach first required confirmation that the weak tissue fixation protocol found to be necessary and optimal for immunofluorescence visualization of some of the proteins examined in this study (e.g., ZO-1, ZONAB, MUPP1) rendered EGFP fluorescence undetectable. As shown in supplementary Figure 1, oligodendrocytes in brains from Cx47 KO mice were faintly positive for EGFP in cryostat sections that were immediately coverslipped after sectioning without immunohistochemical processing (Fig. S1A), compared with the absence of EGFP fluorescence in similarly prepared sections from wild-type mice (Fig. S1B). However, after processing of tissues for immunofluorescence as described above, sections from brains of Cx47 KO mice displayed negligible EGFP fluorescence (Fig. S1C) and exhibited the same low level of background as seen in similarly processed sections from brains of wild-type mice (Fig. S1D). Sections of brains from Cx47 KO mice were also totally devoid of immunolabelling for EGFP when processed with anti-EGFP using Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (not shown). These results, taken together, indicate that EGFP diffuses and is washed out of cells after weak tissue fixation, consistent with recommendations of stronger tissue fixation for its adequate detection (Invitrogen).

Expression vectors, cell culture and transient transfection

GW1-MUPP1 expression vector containing the full-length of the MUPP1 coding region was provided by Dr. Ronald Javier (Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas). Transformation of GW1-MUPP1 into DH5α-competent cells and extraction of GW1-MUPP1 recombination plasmid were prepared according to manufacturer’s standard procedure (Invitrogen; Qiagen). HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. For transient transfection, HeLa cells were transfected for 24 h with either empty vector or GW1-MUPP1 plasmid using Lipofectamine™ 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) as described previously (Li et al., 2004) and harvested for Western blotting.

A truncated Cx47 expression vector was constructed using full-length Cx47 pcDNA3 vector as template. The following primers were used for amplification of truncated Cx47 DNA lacking the c-terminus four animo acids. Sense: 5′- GGGGGG GTA CCG ACC AAC ATG AGC TGG AGC TTC C -3′, Antisense: 5′- TCA GGC CTT GCC GTC TCT GCT GC-3′. The PCR was carried out in 20 μL of solution containing 2 μL of 10 × PCR buffer, 0.8 μL of 50 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 100 ng sense and antisense primers, 0.5 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide, one unit of TaqDNA polymerase and 50 ng of Cx47-pcDNA3 plasmid. The PCR conditions were 94 °C for 3 min, then 35 cycles of amplification at 94 °C for 45 s, 60 °C for 60 s, and 72 °C for 2 min. This was followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min for T-A cloning. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and purified using a gel purification kit (Qiagen Inc, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). PCR products were subcloned into PCR 2.1 vector, digested with EcoRI, and ligated into pcDNA3 expression vector using T4 DNA ligase according to manufacturer’s instruction. Recombinant plasmids were extracted and the orientation was verified by using Apa I or Xba I digestion of the recombinant plasmids. For transient co-transfection experiment, HeLa cells were transfected with MUPP1 and either full-length Cx47 or truncated Cx47 using LipofectAMINE 2000 reagent as previously described (Li et al., 2004).

Western blotting

After transient transfection, cultured HeLa cells were rinsed briefly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.9% saline) and lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EGTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, and 5 μg/mL each of the protease inhibitors leupeptin, pepstatin A and aprotinin. Mouse whole brain and sciatic nerve were collected, rapidly frozen, stored at -80°C, and subsequently homogenized in IP buffer. HeLa cell lysates and tissue homogenates were sonicated and briefly centrifuged, followed by protein determination using a kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Sample proteins (20 μg) were separated electrophoretically in 7% (for MUPP1 detection) or 12.5% (for Cx47 detection) polyacrylamide gels and transblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) in standard Tris-glycine transfer buffer (pH 8.3) containing 0.5% SDS. Membranes were blocked for 2 h at room temperature in TSTw solution (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween-20) containing 5% non-fat milk powder, followed by a brief wash with TSTw. Membranes were incubated for 16 h at 4°C with anti-MUPP1 Ab42-2700 (1 μg/mL) or anti-Cx47 Ab37-4500 (0.5 μg/mL) in TSTw containing 1% non-fat milk powder, then washed four times in TSTw for 40 min, and incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or donkey anti-mouse IgG diluted 1:5,000 (Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Oakville, ON, Canada) in TSTw containing 1% non-fat milk powder. Membranes were then washed in TSTw four times for 40 min and resolved by chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham PB, Baie d’Urfe, Quebec, Canada).

Immunoprecipitation

Homogenates of whole brain were briefly sonicated in IP buffer, cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C, and 1 mg of supernatant protein was washed for 1 h at 4°C with 20 μL of protein A-coated agarose beads (Santa Cruz BioTech, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Samples were then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants were incubated with 2 μg of polyclonal primary antibody with shaking for 2 h at 4°C, followed by 1 h of incubation with 20 μL of protein-A coated agarose beads. The mixture was then centrifuged at 20,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C, and pelleted beads were washed five times under rotation with 1 mL of washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40). The beads were then collected and boiled for 3 min in SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 10% β-mercaptoethanol and taken for immunoblot detection of proteins in IP material. Control samples were taken through the IP procedure with exclusion of the primary antibody used for IP.

Results

Characterization of anti-MUPP1

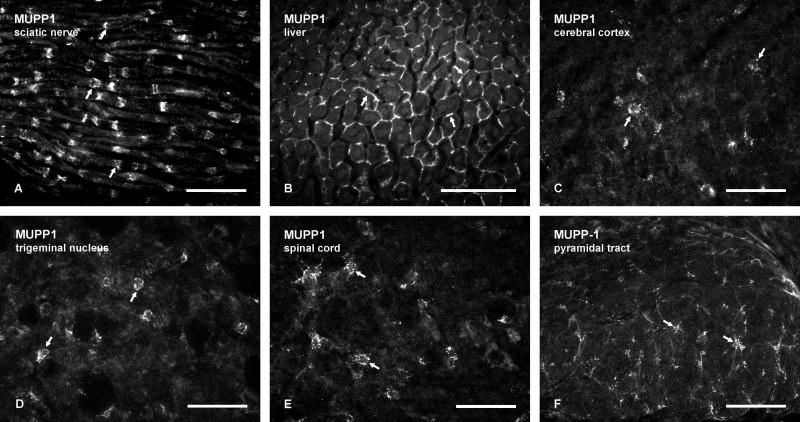

In sciatic nerve, Ab42-2700 produced robust immunofluorescence labelling along myelinated fibers (Fig. 1A), with a pattern that closely matched the previously reported distribution of MUPP1 intermittently at Schmidt-Lanterman incisures, as revealed by other antibodies against MUPP1 (Poliak et al., 2002). This pattern resembled the distribution of several other proteins (Cx29, Cx32, myelin associated glycoprotein) at these incisures (Bergoffen et al., 1993; Li et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2005). In liver, anti-MUPP1 Ab42-2700 gave intense labelling around the periphery of hepatocytes (Fig. 1B). Hepatic MUPP1-immunoreactivity was highly co-localized with labelling for the tight junction-associated protein ZO-1, as observed by MUPP1/ZO-1 double immunofluorescence in sections of liver (not shown), consistent with the reported association of MUPP1 with tight junctions in various cell types (Hamazaki et al., 2002; Jeansonne et al., 2003; Coyne et al., 2004; Ebnet et al., 2004). In brain, MUPP1 was previously localized immunohistochemically to various structures, including neurons and choroid plexus (Becamel et al., 2001; Sitek et al., 2003), although details of its subcellular localization in vivo are not yet available. The patterns of immunofluorescence labelling obtained here with anti-MUPP1 Ab42-2700 in the CNS of CD1 mice and rats were similar to those described in these earlier reports; labelling of choroid plexus was robust, and labelling of neuronal cell bodies tended to be diffuse and weak, but some neurons occasionally exhibited fine MUPP1-positive puncta (not shown), consistent with the reported association of MUPP1 with post-synaptic densities in cultured neurons (Krapivinsky et al., 2004). Thus, the newly developed anti-MUPP1 Ab42-2700 displayed similar specificity characteristics by immunofluorescence as those previously described.

FIG. 1.

Immunofluorescence labelling with anti-MUPP1 in peripheral tissues and brain of adult mouse. A,B: Labelling of Schmidt-Lanterman incisures along myelinated fibers in sciatic nerve (A, arrows), and labelling of tight junctions at appositions between hepatocytes in liver (B, arrows). C-F: Immunolabelling in gray matter of brain and spinal cord, showing small MUPP1-immunopositive cells in the cerebral cortex (C, arrows), trigeminal motor nucleus (D, arrows) and spinal cord dorsal horn (E, arrows). F: Immunolabelling in white matter showing MUPP1-positive cells in the pyramidal tract (arrows). Scale bars: A,C,D,E, 50 μm; B,F, 100 μm.

Localization of MUPP1 in oligodendrocytes

In addition to the MUPP1-immunoreactive structures noted above, immunolabelling with Ab42-2700 in all gray matter regions of brain and spinal cord was prominently associated with small cells and their initial processes, as shown in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1C), the trigeminal nucleus shown as a representative area in the brainstem (Fig. 1D), and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Fig. 1E). These cells had the morphological appearance of oligodendrocytes, on which we focused in the present study. At low magnification, immunolabelling appeared largely granular or punctate, and was distributed around the peripheral margins of cells, which exhibited only faint diffuse cytoplasmic labelling. Similar labelling of small cells and their thin initial processes was observed in white matter, as shown in the pyramidal tract (Fig. 1F). Punctate immunofluorescence labelling for MUPP1 was also observed along myelinated fibers in white matter, but only in large fiber tracts such as the pyramidal tract (Fig. 1F), the corpus callosum and internale capsule (described below), where these puncta along fibers appeared more faint than those seen on small cell bodies.

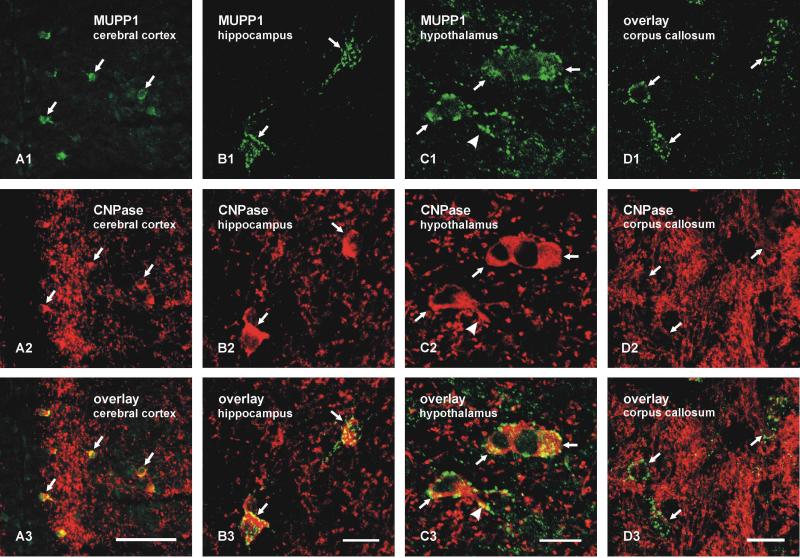

Double immunofluorescence labelling for MUPP1 and the oligodendrocyte marker CNPase confirmed that all MUPP1-positive small cells were CNPase-positive (Fig. 2A). By laser scanning confocal microscopy, punctate labelling for MUPP1 was more clearly seen distributed largely around the plasma membrane of CNPase-positive oligodendrocytes and their initial processes, as demonstrated in the hippocampus (Fig. 2B) and hypothalamus (Fig. 2C). A similar pattern of MUPP1 labelling associated with CNPase-positive oligodendrocytes was seen in white matter, as shown in the corpus callosum (Fig. 2D), but dense labelling of CNPase along myelinated fibers in fiber tracts tended to obscure weaker labelling of CNPase in oligodendrocyte cell bodies. Sections from various brain regions of three mice were immunolabelled as illustrated in Figure 2, and were used to determine the proportion of oligodendrocyte somata that displayed MUPP1-positive puncta. Counts of over 300 CNPase-positive cells in each of the cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, cerebellum and brainstem (total of > 1800 cells) revealed that all were decorated with MUPP1-puncta, and none were seen without labelling for MUPP1.

FIG 2.

Double immunofluorescence labelling of MUPP1 and CNPase in adult mouse brain. A: Low magnification of the cingulate and adjacent motor cortex showing MUPP1-positive cells (A1, arrows) immunolabelled for the oligodendrocyte marker CNPase (A2, arrows), as shown by overlay (A3, arrows). B-D: Higher magnification laser scanning confocal double immunofluorescence showing oligodendrocyte somata double-labelled for MUPP1 and CNPase in the hippocampus (B1,B2, same field), hypothalamus (C1,C2, same field), and corpus callosum (D1,D2, same field), with overlays shown in B3,C3 and D3, respectively. Immunolabelling of MUPP1 appears as puncta (B1,C1,D1, arrows) around the periphery of oligodendrocyte cell bodies (B2,C2,D2, arrows) and along their initial processes (C1,C2, arrowhead). CNPase-positive oligodendrocyte somata are less evident in the corpus callosum due to heavy labelling of CNPase in white matter. Scale bars: A, 50 μm; B-D, 10 μm.

MUPP1 co-localization with glial connexins

The punctate pattern of immunofluorescence labelling for MUPP1 associated with oligodendrocyte somata was identical to the previously described distribution of oligodendrocytic Cx47 and Cx32, which form gap junctions with astrocytic Cx30 and Cx43 on these cells (Nagy et al., 2003a; Li et al., 2004). Confocal double immunofluorescence was therefore conducted to determine spatial relationships between MUPP1 and these various connexins. In all brain regions examined and as shown in the thalamus, MUPP1-positive puncta on oligodendrocyte somata were highly co-localized with Cx47-positive puncta (Fig. 3A) as well as with Cx32-positive puncta (Fig. 3B). In the vicinity of oligodendrocytes, numerous Cx32-positive puncta were seen to be devoid of immunolabelling for MUPP1 (Fig. 3B), and these Cx32-puncta were attributed to labelling of Cx32 associated with myelinated fibers, as previously reported (Li et al., 1997; Nagy et al., 2003b). As expected based on observations of the presence of all four of the above connexins in many heterotypic O/A gap junctions (Nagy et al., 2004), MUPP1 on oligodendrocyte somata was also co-localized with a small subpopulation of astrocytic Cx30-positive (Fig. 3C) and Cx43-positive (Fig. 3D) puncta distributed on the surface of these somata in all brain regions. Additional densely distributed Cx30-puncta and Cx43-puncta seen in the fields of Figure 3C and 3D, representing astrocyte-astrocyte gap junctions, lacked labelling for MUPP1.

FIG. 3.

Laser scanning confocal double immunofluorescence of MUPP1 with glial connexins associated with oligodendrocytes somata in adult mouse brain. Each vertical set of three images (e.g., A1,A2,A3) show the same field, with the third image (e.g., A3) representing overlay of the first two (e.g., A1,A2). A: Oligodendrocyte somata in the thalamus displaying MUPP1-puncta (A1, arrows) and Cx47-puncta (A2, arrows) around their periphery, with co-localization of puncta shown by yellow in overlay (A3, arrows). B: Oligodendrocyte somata in the thalamus displaying MUPP1-puncta (B1, arrows) and Cx32-puncta (B2, arrows) around their periphery, with co-localization of puncta shown in overlay (B3, arrows). C: Oligodendrocyte somata in the hypothalamus decorated by MUPP1-puncta (C1, arrows) and co-localized with a small subpopulation of Cx30-positive puncta (C2, arrows), as shown in overlay (C3, arrows). D: Oligodendrocyte somata in the thalamus showing MUPP1-puncta around their periphery (D1, arrows) co-localized with a subpopulation of Cx43-positive puncta (D2, arrows), as shown in overlay (D3, arrows). Scale bars: 10 μm.

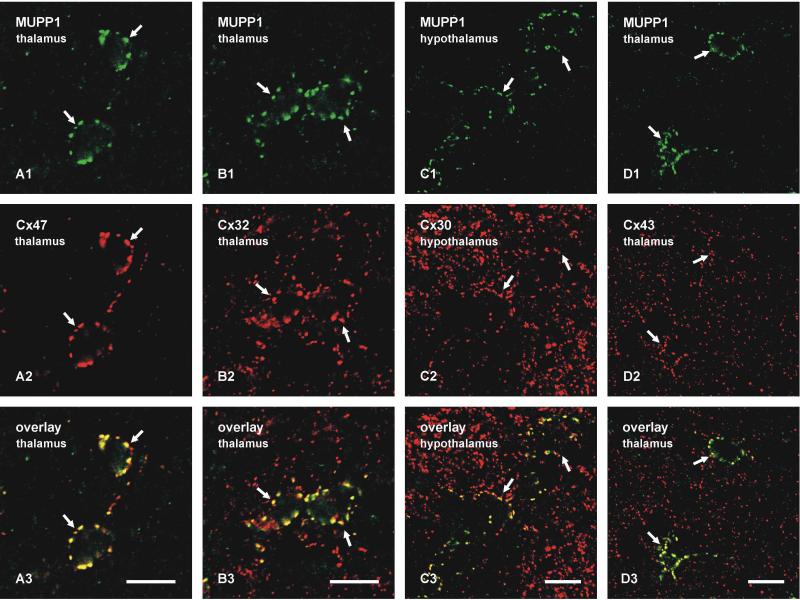

Immunoblotting of MUPP1 and Cx47/MUPP1 co-IP

Western blotting was used to confirm specificity of Ab42-2700 for MUPP1 and to establish co-association of Cx47 with MUPP1. In immunoblots loaded with equal protein from brain and sciatic nerve homogenates, Ab42-2700 recognized a single protein band migrating at about 220 kDa (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2, respectively), which was more abundant in sciatic nerve than in brain. In HeLa cells transiently transfected with HA-tagged MUPP1, Ab42-2700 recognized a similarly migrating band, which was absent in control empty-vector transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4, respectively). After IP of MUPP1 from brain homogenate with polyclonal Ab42-2700 in three separate experiments, immunoblots of IP material probed with monoclonal anti-Cx47 revealed the presence of Cx47 (Fig. 4B, lane 2), which co-migrated with Cx47 in brain homogenate that was included as a positive control for Cx47 detection (Fig. 4B, lane 1). Cx47 was absent in IP material after omission of anti-MUPP1 during the IP procedure, which was included as a negative control (Fig. 4B, lane 3). Specificity of the monoclonal anti-Cx47 was shown by its detection of a single band in Cx47-transfected HeLa cells and absence of this band in control HeLa cells transfected with empty-vector (Fig. 4B, lanes 4 and 5, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot characterization of anti-MUPP1 and monoclonal anti-Cx47. A: Western blots showing detection of MUPP1, migrating at 220 kDa (arrowhead), in homogenates of mouse brain (lane 1) and sciatic nerve (lane 2), and detection of a MUPP1 band at 220 kDa in lysate from HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged MUPP1 (lane 3), and absence of this band in control empty vector-transfected HeLa cells (lane 4). B: Western blot demonstrating co-IP of MUPP1 with Cx47. Lanes were loaded with mouse brain homogenate (lane 1), immunoprecipitate protein after IP of MUPP1 from mouse brain homogenate with polyclonal anti-MUPP1 (lane 2), and IP control with omission of anti-MUPP1 (lane 3). Blot probed with monoclonal anti-Cx47 shows detection of Cx47 in IP material (lane 2), co-migrating with Cx47 detected in brain (lane 1), and absence of Cx47 in IP material after omission of anti-MUPP1 during the IP procedure (lane 3). Specificity of monoclonal anti-Cx47 was shown by its detection of Cx47 in Cx47-transfected HeLa cells (lane 4) and absence of detection in control empty vector-transfected HeLa cells (lane 5). C: IP of MUPP1 from HeLa cells transfected with either full-length or truncated Cx47 (Tr-Cx47) and co-transfected with MUPP1, followed by probing with anti-Cx47. Blot shows co-IP of full-length Cx47 with MUPP1 (lane 4) and absence of co-IP of Tr-Cx47 with MUPP1 (lane 5). Control lanes show detection of Cx47 in HeLa cells transfected with full-length (lane 1) or trunctated Cx47 (lane 3), Cx47 detection after IP of MUPP1 from brain (lane 2), and absence of a Cx47 band after omission of anti-MUPP1 during IP (Lane 6). D: IP of various connexins from mouse brain followed by probing for MUPP1. Blot shows detection of MUPP1 after IP of Cx47 (lane 1) and Cx43 (lane 2), but not after IP of Cx32 (lane 3) or Cx30 (lane 4). E: Blot showing detection of Cx43 after IP of Cx47 (lane 2) from mouse brain, with controls showing detection of Cx43 in brain homogenate (lane 1) and absence of a Cx43 band after omission of anti-Cx43 during IP (lane 3).

To determine whether co-IP of Cx47/MUPP1 was dependent on molecular interactions involving the PDZ binding motif of Cx47, HeLa cells were taken for IP of Cx47 after co-transfection with MUPP1 and either full-length Cx47 or truncated Cx47 lacking the C-terminal four amino acid PDZ domain binding motif. As shown in Fig. 4C, IP of MUPP1 resulted in detection of full-length Cx47 (lane 4) but not truncated Cx47 (lane 5) in IP material. Positive controls included demonstration of Cx47 detection in transfected HeLa cells (lane 1) and after IP of MUPP1 from brain (lane 2) in a separate experiment from that in Fig. 4B, and demonstration that anti-Cx47 was able to detect truncated Cx47 (lane 3). Omission of anti-Cx47 during IP resulted in the absence of a Cx47 detection (lane 6).

Additional experiments were undertaken to determine whether IP of other glial connexins result in detection of MUPP1 in IP material. IP of Cx47 was used as a positive control for MUPP1 detection as well as for demonstrating Cx47/MUPP1 co-IP using anti-Cx47 (Fig. 4D, lane 1). A weaker MUPP1 band was also detected after IP of Cx43 (Fig. 4D, lane 2), but not after IP of Cx32 or Cx30 (Fig. 4D, lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Similar results were obtained after reverse IP with anti-MUPP1, namely detection of Cx47 and Cx43, but not Cx32 nor Cx30 (not shown). Since MUPP1 was found to be absent in astrocytes by immunofluorescence, detection of MUPP1 after IP of Cx43 may have resulted from maintained association of Cx43 with its connexin pairing partner Cx47 bound to MUPP1 in brain homogentates. This possibility was supported by the demonstration that IP of Cx47 from brain led to detection of Cx43 in IP material, where a major Cx43 band (Fig. 4E, lane 2) co-migrated with Cx43 found in brain homogentate (Fig. 4E, lane 1), and several other faster migrating bands corresponding to known dephosphorylated forms of Cx43 (Fig. 4E, lane 2) that were less evident in the whole brain homogenate. Cx43 was not detected after omission of anti-Cx47 during the IP procedure.

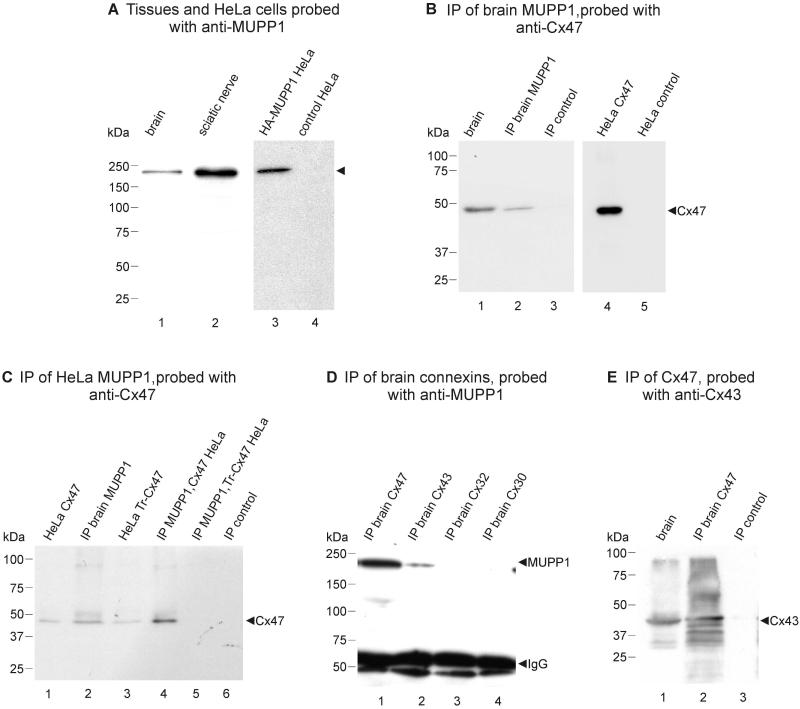

Immunolabelling of MUPP1, ZONAB and ZO-1 in Cx47 KO mice

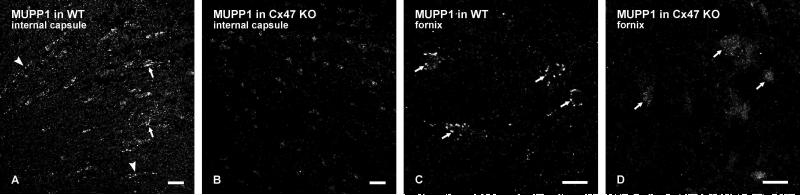

We next used Cx47 KO mice to determine whether MUPP1 localization at oligodendrocyte gap junctions was dependent on the presence of Cx47 at these junctions. Two other proteins, ZONAB and ZO-1, previously reported to be associated with oligodendrocyte gap junctions (Penes et al., 2005), were also examined in Cx47 KO mice. In wild-type C57BL/6 mice, immunolabelling of MUPP1 in brain was identical to that described above in CD1 mice. In regions of white matter in wild-type mice, punctate labelling was observed on cells and sparsely along fibers as shown in the internal capsule (Fig. 5A) and predominantly on cells as seen in the fornix, as shown in supplementary Figure S2A and S2C, respectively, whereas labelling for MUPP1 in C57BL/6 mice with Cx47 gene deletion was largely reduced or absent in these structures (Fig. S2B,D) and all other white matter regions examined.

FIG. 5.

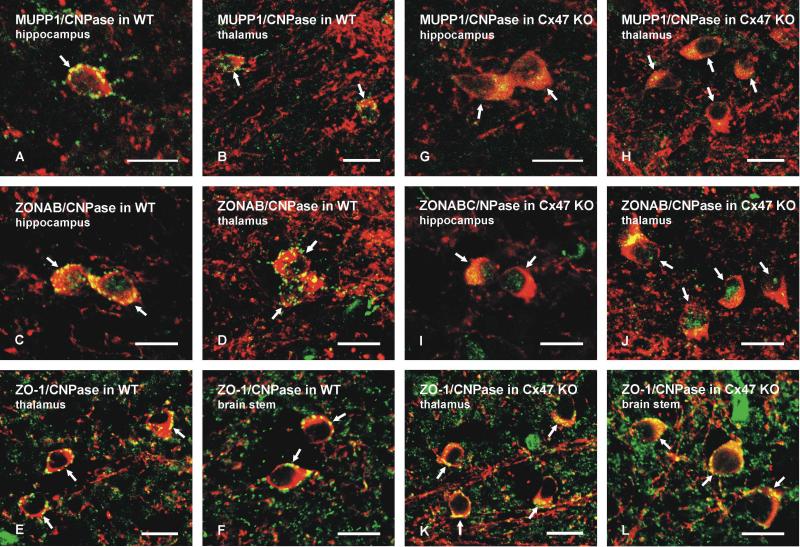

Laser scanning confocal double immunofluorescence comparing MUPP1, ZONAB and ZO-1 association with gap junctions on oligodendrocyte somata in various gray matter brain regions of wild-type and Cx47 KO mice. A-L: All images are shown as overlays in fields of the brain regions indicated, with the oligodendrocyte marker CNPase labelled red and gap junction-associated proteins labelled green. Overlap of red and green labels appears as yellow. Punctate labelling (seen as green or yellow puncta) for MUPP1 (A,B), ZONAB (C,D) and ZO-1 (E,F) is seen on oligodendrocyte somata (labelled red, arrows) in each of the brain regions in wild-type mice (A-F). Labelling for MUPP1 (G,H) and ZONAB (I,J) is absent around the periphery of oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO mice (G-J, arrows), but fine punctate labelling for ZO-1 is still seen around the periphery of oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO mice (K,L, arrows). Scale bars: 10 μm.

In gray matter, confocal double immunofluorescence images shown only as overlays (with red/green overlap appearing yellow) of labelling for CNPase (red) with either MUPP1 (Fig. 5A,B, green), ZONAB (Fig. 5C,D, green) or ZO-1 (Fig. 5E,F, green) in various brain regions of wild-type C57BL/6 mice revealed the typical punctate labelling of these proteins associated with oligodendrocyte somata that was seen in CD1 mice, as previously reported (Penes et al., 2005). In Cx47 KO mice, CNPase-positive oligodendrocyte somata were completely devoid of MUPP1-puncta (Fig. 5G,H) and ZONAB-puncta (Fig. 5I,J). Concomitantly, diffuse intracellular labelling for MUPP1 and ZONAB was increased and was more evident in the cytoplasmic compartment of these somata from Cx47 KO mice, as seen by dispersed yellow colour resulting from red and green overlap (Fig. 5G-J). In addition, some labelling for ZONAB in Cx47 KO mice appeared to be localized within the nuclear compartment of oligodendrocytes (Fig. 5I,J, seen as green), which was devoid of CNPase. By contrast, punctate labelling of ZO-1 remained associated with oligodendrocyte somata after Cx47 gene deletion (Fig. 5K,L), but appeared more dispersed and of finer grain than typically seen in wild-type mice.

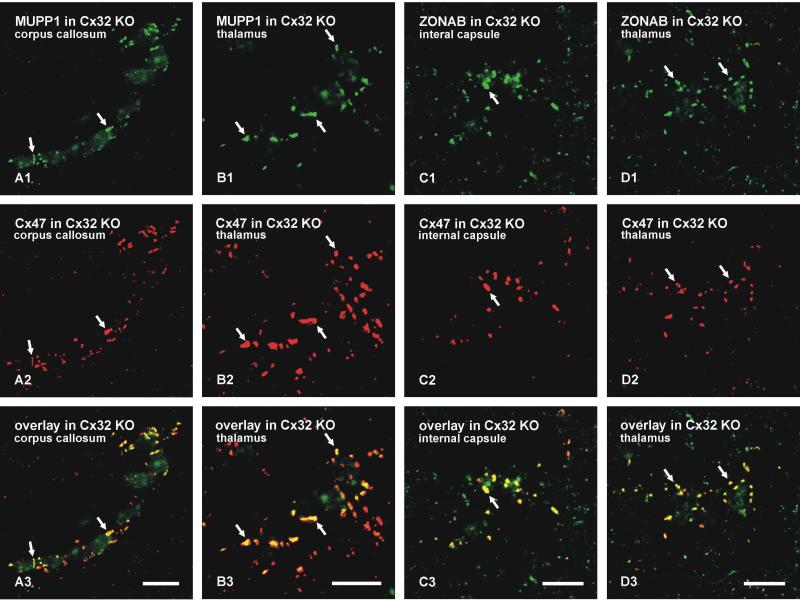

The cellular localization of MUPP1 and ZONAB was also examined in Cx32 KO mice (Nelles et al., 1996) to determine whether gap junctional targeting of these proteins was equally disrupted after loss of Cx32 as that seen after loss of Cx47. In these mice, Cx47 remains densely distributed on oligodendrocyte somata (Nagy et al., 2003b) and was used as a marker for O/A gap junctions in double-labelled sections. As shown in both white matter of the corpus callosum (Fig. 6A) and gray matter of the thalamus (Fig. 6B), punctate labelling for MUPP1 persisted on oligodendrocyte somata and remained co-localized with Cx47 in Cx32-deficient mice. Similarly, as shown in white matter of the internal capsule (Fig. 6C) and gray matter of the thalamus (Fig. 6D), ZONAB remained associated with O/A gap junctions in Cx32 KO mice, as demonstrated by its co-localization with Cx47 in these mice.

FIG. 6.

Laser scanning confocal immunofluorescence of MUPP1 and ZONAB association with gap junctions on oligodendrocyte somata in white and gray matter brain regions of Cx32 KO mice. A,B: Double labelling for MUPP1 and Cx47 in the corpus callosum (A) and the thalamus (B) showing co-localization of MUPP1-positive puncta (A1,B1, arrows) with Cx47-positive puncta (A2,B2, arrows) at O/A gap junctions in these brain regions of Cx32 KO mice. C,D: Double labelling for ZONAB and Cx47 in the internal capsule (C) and the thalamus (D) showing co-localization of ZONAB-positive puncta (C1,D1, arrows) with Cx47-positive puncta (C2,D2, arrows) at O/A gap junctions in these brain regions of Cx32 KO mice. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Immunolabelling of Cx26, Cx30, Cx32 and Cx43 in Cx47 KO mice

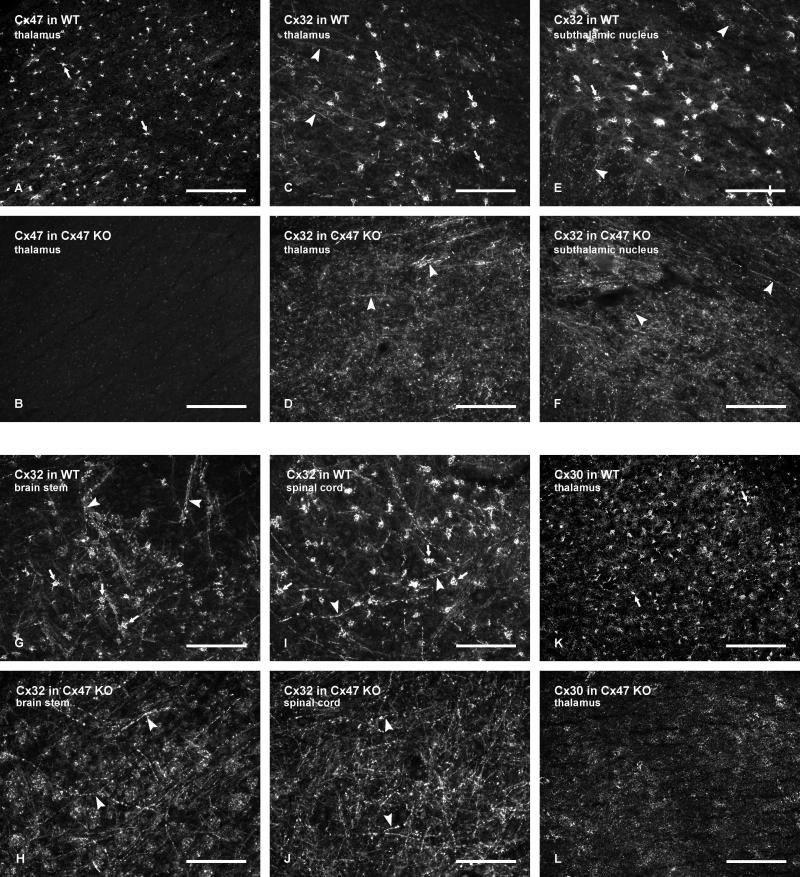

We next investigated whether Cx47 gene deletion had an influence on the localization of other connexins associated with glial cells. Immunofluorescence labelling for Cx30, Cx32, Cx43 and Cx47 on oligodendrocyte somata of wild-type C57BL/6 mice was similar to that previously described in CD1 mice (Rash et al., 2001; Li et al., 2004). Intense labelling for Cx47 typically delineated oligodendrocyte cell bodies even at low magnification, as shown by the visualization of numerous Cx47-positive cells in the thalamus (Fig. 7A). In a similar field of the thalamus from Cx47 KO mice, labelling for Cx47 was totally absent (Fig. 7B), indicating the specificity of monoclonal anti-Cx47 Ab37-4500. Similar results were obtained with polyclonal anti-Cx47 Ab36-4700 (not shown). Oligodendrocyte cell bodies in wild-type mice were similarly laden with dense labelling for Cx32, and sparse to moderate labelling of Cx32 was seen associated with myelinated fibers, as illustrated in the thalamus (Fig. 7C), subthalamic nucleus (Fig. 7E), brainstem (Fig. 7G) and spinal cord gray matter (Fig. 7I). In corresponding fields of each of these brain regions from Cx47 KO mice, labelling of Cx32 on oligodendrocyte somata was entirely absent, and immunolabelling associated with myelinated fibers was dramatically increased (Fig. 7D,F,H,J). Labelling of Cx32 on oligodendrocytes and along myelinated fibers with the antibodies used here was previously shown to be eliminated in Cx32 KO mice (Nagy et al., 2003b), indicating specificity of these antibodies. Although selectively expressed in astrocytes, Cx30 is also heavily concentrated on the astrocyte side of O/A gap junctions (Nagy et al., 2003b), allow visualization of dense Cx30-positive puncta on oligodendrocyte somata at relatively low magnification in wild-type mice, as shown in the thalamus (Fig. 7K), but which were absent on these somata in Cx47 KO mice (Fig. 7L).

FIG. 7.

Low magnification immunofluorescence micrographs showing altered distribution of Cx32 and Cx30 in brain regions of Cx47 KO compared with wild-type mice. A,B: Images showing Cx47 associated with oligodendrocyte somata (A, arrows; all white dots represent Cx47-positive oligodendrocyte somata) in the thalamus of wild-type mice, and absence of labelling in the thalamus of Cx47 KO mice (B). C-J: Immunolabelling of Cx32 in the thalamus (C,D), subthalamic nucleus (E,F), brain stem (G,H) and spinal cord gray matter (I,J) of wild-type mice (C,E,G,I) and Cx47 KO mice (D,F,H,J). Numerous oligodendroctye somata (arrows) and varying densities of myelinated fibers (arrowheads) are seen labelled for Cx32 in each of the brain regions of wild-type mice. No labelling of Cx32 at oligodendrocyte somata is evident in any of the brain regions in Cx47 KO mice, but myelinated fibers (D,F,H,J, arrowheads) in each region exhibit an increased density of labelling for Cx32 in Cx47 KO mice. K,L: Immunolabelling of Cx30 in the thalamus, showing a high concentration of astrocytic Cx30 around oligodendrocyte somata (K, arrows; all white dots represent Cx30 associated with oligodendrocyte somata) in wild-type mice, and an absence of labelling for Cx30 at oligodendrocyte somata in the thalamus of Cx47 KO mice (L). Scale bars: A,B,K,L, 200 μm; C-J, 100 μm.

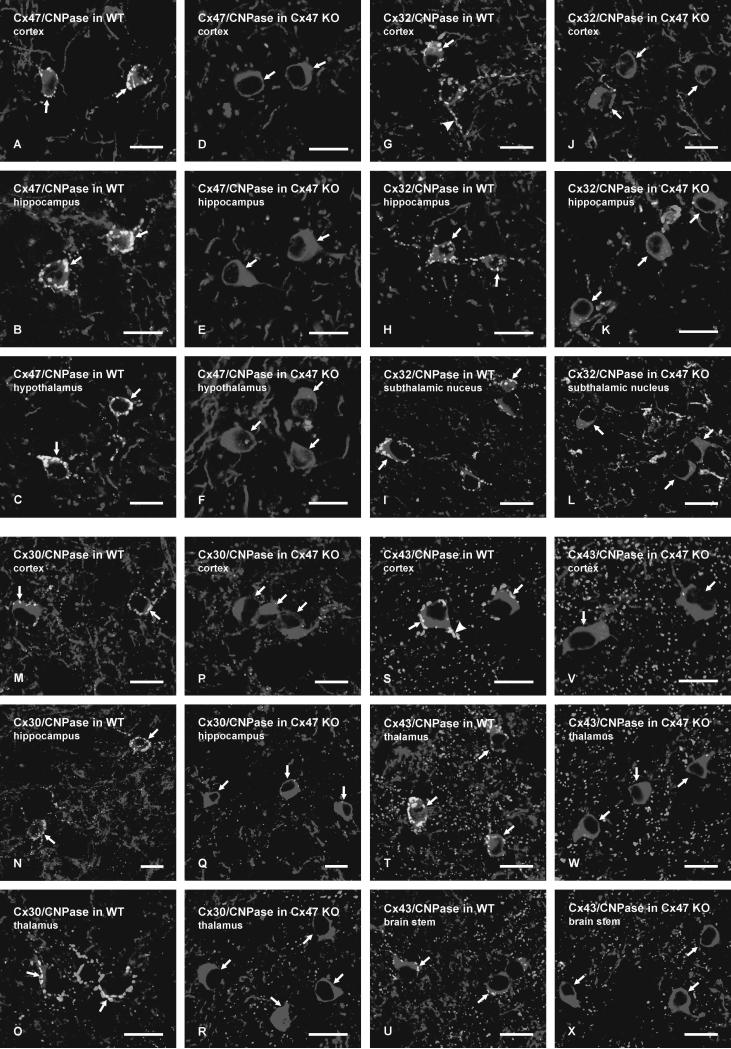

Labelling of connexins associated with oligodendrocyte somata in wild-type and Cx47 KO mice was examined in greater detail by laser scanning confocal double immunofluorescence for CNPase and each of the glial connexins (Fig. 8). Images of double labelling in several corresponding brain regions from wild-type and Cx47 KO mice are presented only as overlays of CNPase labelled red and connexins labelled green, with red/green overlap appearing yellow. In wild-type mice, virtually all CNPase-positive oligodendrocyte cell bodies displayed some degree of punctate labelling for Cx47 (Fig. 8A-C), Cx32 (Fig. 8G-I), Cx30 (Fig. 8M-O) and Cx43 (Fig. 8S-U). In Cx47 KO mice, CNPase-positive oligodendrocytes in the same brain regions were devoid of Cx47 (Fig. 8D-F), as expected, but were also devoid of Cx32 (Fig. 8J-L), Cx30 (Fig. 8P-R) and Cx43 (Fig. 8V-X). Similar results were obtained in surveys of each of these connexins in all other brain regions examined in Cx47 KO mice, including striatum, midbrain areas and spinal cord.

FIG. 8.

Laser scanning confocal double immunofluorescence of connexins associated with CNPase-positive oligodendrocyte somata in various brain regions of wild-type mice, and absence of connexins on these somata in Cx47 KO mice. All images are shown as overlays of the brain regions indicated, with the oligodendrocyte marker CNPase labelled red and connexins labelled green. Overlap of red and green label appears as yellow. A-F: Dense labelling of Cx47 (yellow puncta) is seen on CNPase-positive oligodendrocytes somata (arrows) in wild-type mice (A-C), but is absent on these somata in Cx47 KO mice (D-F). G-L: Punctate labelling of Cx32 is seen on CNPase-positive oligodendrocyte somata and their initial processes in wild-type mice (G-I, arrows), but is absent on these cells in Cx47 KO mice (J-L, arrows). M-X: CNPase-positive oligodendrocyte somata (arrows) are decorated with punctate labelling for the astrocytic connexins Cx30 (M-O) and Cx43 (S-U) in wild-type mice, but are devoid of labelling for Cx30 (P-R) and Cx43 (V-X) in Cx47 KO mice. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Discussion

The present results demonstrate: 1. That in addition to its reported expression in neurons (Becamel et al., 2001; Sitek et al., 2003), the multi-PDZ domain scaffolding protein MUPP1 is also expressed in oligodendrocytes, where it is largely associated with heterotypic gap junctions on oligodendrocyte somata, and where Cx32 and Cx47 were previously shown to be localized on the oligodendrocyte side and Cx30 and Cx43 on the astrocyte side (Nagy et al., 2004); 2. That the connexin and connexin-accessory protein composition at oligodendrocyte plasma membranes is radically altered in Cx47 KO mice. We show that subcellular targeting of MUPP1 as well as Cx32 and ZONAB to oligodendrocyte gap junctions requires the presence of Cx47, as demonstrated by the absence of these three proteins at O/A gap junctions in Cx47 KO mice. In contrast, localization of ZO-1 on oligodendrocyte somata was altered, but still present. 3. That subcellular targeting of the astrocytic connexins Cx30 and Cx43 to gap junctions formed by astrocyte processes with oligodendrocyte somata was dependent on the presence of Cx47 in oligodendrocytes. And 4. That loss of Cx32 at oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO mice was accompanied by an increased trafficking of this connexin to sites along myelinated fibers.

MUPP1 expression in oligodendrocytes and association with O/A gap junctions

Previous studies of MUPP1 in neurons and Schwann cells have indicated that it serves a scaffolding role for transmitter receptors and tight junctions in these cells, respectively (Ullmer et al., 1998; Becamel et al., 2001; Balasubramanian et al., 2007; Poliak et al., 2002; Hamazaki et al., 2002; Krapivinsky et al., 2004; Coyne et al., 2004). Our results expand the cellular expression profile of MUPP1 to include the CNS oligodendrocyte counterparts of peripheral Schwann cells. In both of these cell types, MUPP1 was localized at subcellular sites containing connexins; Schmidt-Lanterman incisures in Schwann cells (Poliak et al., 2002) and O/A gap junctions in oligodendrocytes (present results). The localization of MUPP1 on the oligodendrocyte side of O/A gap junctions, rather than the astrocyte side, was inferred from the absence of immunolabelling for MUPP1 at astrocyte-astrocyte gap junctions, and observations of intracellular labelling for MUPP1 in oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO mice. Although we observed co-IP of Cx43 and MUPP1 from brain, this was likely a result of indirect molecular associations, namely, Cx43 coupling to Cx47 and the latter connexin to MUPP1 at O/A gap junctions. Indirect co-IP of Cx43/MUPP1 is consistent with our finding of Cx43/Cx47 co-IP from brain tissue. The loss of both Cx32 and Cx47 together with the loss of MUPP1 on oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO mice indicates the absence of O/A gap junctions in these mice and connexin-dependent targeting of MUPP1 to gap junctions. These observations, together with results showing co-IP of Cx47 with MUPP1 and elimination of this co-IP after C-terminal truncation of the PDZ domain binding motif of Cx47, suggest a scaffolding role of MUPP1 at O/A gap junctions. However, further investigations are required to characterize direct molecular interactions of MUPP1 with Cx47 and possibly other gap junctions-associated proteins in oligodendrocytes.

Plasma membrane targeting of ZO-1 and ZONAB after Cx47 gene deletion

We previously demonstrated expression of the scaffolding protein ZO-1 in oligodendrocytes, the localization of ZO-1 to O/A gap junctions and the direct molecular interaction of Cx47 with the second of the three PDZ domains in ZO-1 (Li et al., 2004). Further, we found that the transcription factor ZONAB, which associates with the SH3 domain of ZO-1 at tight junctions in cultured MDCK cells (Balda & Matter, 2000, 2003; Balda et al., 2003), is also associated with O/A gap junctions, where it presumably interacts with ZO-1 (Penes et al., 2005). The present results showing the loss of ZONAB at the cytoplasmic membrane surface of oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO mice indicates that the association of ZONAB with O/A gap junctions is dependent on the presence of Cx47. In contrast, the persistence of finer, more broadly distributed ZO-1-positive puncta at the peripheral margins of oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO compared with wild-type mice suggests localization of ZO-1 at some other membrane sites in addition to gap junctions. Although virtually all ZO-1 at the surface of oligodendrocyte somata in wild-type mice appeared to be associated with O/A gap junctions (Penes et al., 2005), the loss of these junctions after deletion of Cx47 may have allowed visualization of ZO-1 at tight junctions, which occur in oligodendrocytes (Massa & Mugnaini 1982; Massa et al., 1984) but appear to be devoid of ZONAB as indicated by the present results. Alternatively, loss of O/A gap junctions after Cx47 deletion may have revealed ZO-1, in the absence of ZONAB, at pre-determined sites for initial deposition of connexins into junctional plaques. This deposition could be mediated by association of ZO-1 with plasma membrane structures via one of its several domains and tethering of Cx47 to the second PDZ domain of nucleated ZO-1.

The loss of ZONAB at O/A gap junctions in Cx47-deficient mice was accompanied by a concomitant elevation in cytoplasmic and nuclear labelling for this transcription factor, which may have functional consequences related to its potentially increased activity at nuclear targets. It was previously reported that ZONAB in canine MDCK cells acts to repress expression of the tyrosine kinase receptor ErbB2 (Balda & Matter., 2000, 2003; Balda et al., 2003), and it is well established that ErbB2 signalling is important for oligodendrocyte survival, differentiation and myelination (Park et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003). Thus, we speculated that ErbB2 signalling in oligodendrocytes may, in part, be regulated by interactions between connexins, ZO-1 and ZONAB at glial gap junctions (Penes et al., 2005). Whether failure of ZONAB sequestration at O/A gap junctions in Cx47 KO mice results in excess ZONAB-mediated suppression of ErbB2 expression in oligodendrocytes, and thereby hampering the development and function of these cells remains to be investigated. In support of this possibility, it is perhaps noteworthy that greater myelin abnormalities were observed in Cx47 KO mice (Odermatt et al., 2003), where we observed ZONAB to be absent at O/A gap junctions, than in Cx32 KO mice (Sutor et al., 2000), where ZONAB persisted at these gap junctions.

Inter-dependency of glial connexin targeting to O/A gap junctions

In hepatocytes, which co-express Cx26 and Cx32 and are linked by gap junctions containing both of these connexins, loss of Cx32 was accompanied by a profound loss of Cx26 (Nelles et al., 1996), indicating an inter-dependency of connexin expression and localization at these homologous junctions. A similar inter-dependency was observed at heterologous heterotypic O/A gap junctions, where absence of Cx32 in oligodendrocytes of Cx32 KO mice resulted in a complete loss of astrocytic Cx30, but Cx43 and Cx47 persisted at these junctions (Nagy et al., 2003b; Altevogt & Paul, 2004). Together with the reported permissiveness of Cx30/Cx32 and non-permissiveness of Cx32/Cx43 channel combinations (White & Bruzzone, 1996; Dahl et al., 1996), our findings suggested I) that Cx47 in oligodendrocytes forms communicating gap junctional channels with astrocytic Cx43, that Cx32 forms channels with Cx30; and III) that Cx32 is required for assembly of its coupling partner (Cx30) into these junctions. The present results showing loss of Cx43 at O/A gap junctions after gene deletion of Cx47 supports the proposed coupling of Cx47 with Cx43 hemichannels, and indicates the requirement of Cx47 for assembly and maintenance of Cx43 at O/A gap junctions. In addition, the loss of Cx30 at O/A gap junctions in Cx47 KO mice is likely due to the loss of its trans-acting coupling partner (Cx32) in these mice, which is consistent with earlier observations showing loss of Cx30 at O/A gap junctions in Cx32 KO mice (Nagy et al., 2003b; Altevogt & Paul, 2004), further indicating the required presence of each of these coupling partners for stable gap junction formation. Overall, our findings are consistent with a recent report by Orthmann-Murphy et al. (2007a) who tested various O/A connexin coupling combinations for permissiveness of functional gap junction channel formation in transfected HeLa cells and found that only Cx47/Cx43 and Cx32/Cx30 heterotypic pairs formed functional channels, suggesting that these pairs may also mediate coupling at O/A gap junctions. They also found that only the homotypic combinations of Cx30/Cx30 and Cx43/Cx43 formed functional channels in transfected HeLa cells, indicating that these channels may mediate coupling at A/A gap junctions (Orthmann-Murphy et al., 2007a). It should be emphasized that these results need to be verified by functional studies of glial gap junctions in brain slices which have not been reported so far.

Cx47-dependent targeting of Cx32 to O/A gap junctions

The observed loss of Cx32 at plasma membranes of oligodendrocyte somata in Cx47 KO mice indicates that, as in the case of ZONAB and MUPP1, targeting also of Cx32 to these membranes requires the presence of Cx47. One potential basis for such dependency is that Cx32 and Cx47 form heteromeric connexons, where connexon hexamers contain a mixture of the two connexins, thus necessarily resulting in co-transport to plasma membranes, and thus lack of Cx32 transport in the absence of Cx47. Such heteromeric connexons occur in other cell types (Sosinsky, 1995; Kumar & Gilula, 1996). However, this is unlikely at O/A gap junctions if, as discussed above, these junctions contain exclusively Cx30/Cx32 and Cx43/Cx47 coupling partners, which suggests homomeric connexon constituents. Moreover, Cx32 trafficking from oligodendrocyte somata to myelinating processes remained intact, suggesting that formation of heteromeric Cx32/Cx47 connexons was not required for this trafficking to occur. Alternatively, Cx47-dependent localization of Cx32 at O/A gap junctions may involve the scaffolding protein MUPP1. O/A gap junctions may initially be formed by Cx47 associated with MUPP1, possibly in conjunction with ZO-1, followed by targeting of Cx32 to these sites. Although we found no evidence for Cx32 association with MUPP1 by co-IP approaches, we cannot at present exclude that MUPP1 may indirectly participate in the recruitment of Cx32 to O/A gap junctions in some as yet unknown manner.

Implications for myelin associated deficits in Cx47 KO mice

The functional importance of Cx32 and Cx47 in oligodendrocyte gap junctions for development and maintenance of myelin was indicated by observations of severe derangements in myelin structure in mice with gene deletion of both these connexins (Menichella et al., 2003), and milder abnormalities in mice lacking either Cx32 or Cx47 (Sutor et al., 2000; Odermatt et al., 2003). In addition, humans with mutations in Cx32 or Cx46.6 (the human ortholog of mouse Cx47), leading to X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-Like disease, respectively, exhibit CNS symptoms related to myelin abnormalities (Bahr et al., 1999; Paulson et al., 2002; Uhlenberg et al., 2004; Orthmann-Murphy et al., 2007b). The basis for these disruptions can be attributed to the functional absence of Cx32 and/or Cx47 in normally extensive gap junctions linking various compartments of oligodendrocytes with astrocytes, providing pathways for the flow of ions, water and metabolites in the glial syncytium, as originally proposed in the concept of K+ spatial buffering (Orkand et al., 1966; Newman, 1986). Recently, subcellular locations at which oligodendrocytes connect gap junctionally with the glial syncytium have been extended and now include their somata, dendrites, outer turn of myelin and paranodal loops, where Cx47 is present in far greater abundance than Cx32 (Kamasawa et al., 2005). In contrast, Cx32 without Cx47, was found in autologous or reflexive gap junctions linking successive cytoplasmic compartment along myelin (Kamasawa et al., 2005). The contribution of these oligodendrocyte gap junctions to K+ spatial buffering was recently supported by physiological evidence demonstrating that myelin vacuolization in Cx32/Cx47 double KO mice increased with extent of neural activity (Menichella et al., 2006). The present observations are relevant to the CNS effects of Cx32 and Cx47 gene deletions and the loci at which these connexins form gap junctions. First, our results indicate that any functional impairments or alterations in oligodendrocytes of Cx47 KO mice results not only from a loss of Cx47 at all locations, but also from a total loss of all connexins and gap junctions on oligodendrocyte somata. Further studies with brain slices will be required to determine whether this leads to uncoupling of oligodendrocyte somata from astrocytes. The total loss of all O/A gap junctions on oligodendrocyte somata is consistent with altered electrophysiological properties of these cells in Cx47 KO mice (Odermatt et al., 2003). Second, the mild CNS deficits observed in Cx47-deficient mice, compared with the more serious and ultimately lethal deficits in Cx32/Cx47 double KO mice, have been attributed to possible compensation of Cx47 loss by Cx32. Our results indicate that such compensation is less likely to occur on oligodendrocyte somata, due to the absence of Cx32 at these somata in Cx47 KO mice. However, the increase of Cx32 observed along myelin in Cx47 KO mice provides evidence for potential compensation. It remains to be determined whether this elevated Cx32 is associated largely with autologous gap junctions as occurs in normal mice (Kamasawa et al., 2005), or whether it occurs at these gap junctions as well as at those along the surface of the internodal myelin following Cx47 gene deletion.

Supplementary Material

FIG. S1. Detectability of EGFP fluorescence in CNS oligodendrocytes after weak tissue fixation of Cx47 KO (Cx47EGFP(-/-)) mice. A,B: Images of sections coverslipped and photographed without immunohistochemical processing, showing faint fluorescence for EGFP in oligodendroctyes of the thalamus from Cx47 KO mice (A), compared with absence of fluorescence in control wild-type thalamus (B). C,D: Images of sections coverslipped and photographed after immunohistochemical processing, showing loss of EGFP fluorescence in oligodendroctyes of the thalamus from Cx47 KO mice and a comparable low level of background (C) as seen in control wild-type thalamus (D). Scale bar: 50 μm.

FIG. S2. A-D: Immunofluorescence labelling of MUPP1 in white matter of wild-type and Cx47 KO adult mice. In wild-type mice, MUPP1-positive puncta are seen associated with oligodendrocyte cell bodies (A, arrows) and sparsely with myelinated fibers (A, arrowheads) in the internal capsule, and with cell bodies in the fornix (C, arrows). In Cx47 KO mice, similar fields of the internale capsule (B) and fornix (D) as in A and C, respectively, show a large reduction in immunolabelling of MUPP1 associated with fibers (B) and with oligodendrocyte somata (D, arrows). Scale bars: A,B, 20 μm; C,D, 10 μm.

FIG. 9.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to J.I.N., and by grants (Wi 270/22-5,6) from the German Research Association to K.W. We thank B. McLean for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Juergen Eiberger for breeding the Cx47 KO mice in the Bonn laboratory. Also supported by NIH (NS44395 to John E. Rash/J.I.N.).

Abbreviations

- aa

amino acids

- Ab

antibody

- O/A

oligodendrocyte-to-astrocyte

- CNPase

monoclonal anti-2,′3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′ phosphodiesterase

- CNS

central nervous system

- Cx

connexin

- EM

electron microscopy

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GJIC

gap junction intercellular communication

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- KO

knockout

- LM

light microscopy

- MDCK

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney

- MsY3

mouse Y-box transcription factor 3

- MUPP1

multi-PDZ domain protein 1

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Development

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PDZ

postsynaptic protein PSD-95/Drosophila junction protein Disc-large/tight junction protein ZO-1

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecylsulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TBS

50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 with 1.5% sodium chloride

- TBSTr

50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1.5% NaCl, 0.3% Triton X-100

- TBSTw

20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl with 0.2% Tween-20

- WT

wild-type

- ZO-1

zonula occludens-1

- ZONAB

ZO-1-associated nucleic acid-binding protein.

References

- Altevogt BM, Kleopa KA, Postma FR, Scherer SS, Paul DL. Connexin29 is uniquely distributed within myelinating glial cells of the central and peripheral nervous system. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:6458–6470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06458.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altevogt BM, Paul DL. Four classes of intercellular channels between glial cells in the CNS. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4313–4323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3303-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr M, Andres F, Timmerman V, Nelis ME, Van Broeckhoven C, Dichgans J. Central visual, acoustic and motor pathway involvement in Charcot-Marie-Tooth family with an asn205ser mutation in the connexin32 gene. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psych. 1999;66:202–206. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S, Fam SR, Hall RA. GABAB receptor association with the PDZ scaffold MUPP1 alters receptor stability and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:4162–4171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Matter K. The tight junction protein ZO-1 and an interacting transcription factor regulate ErbB-2 expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:2024–2033. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Matter K. Epithelial cell adhesion and the regulation of gene expression. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:310–318. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Garrett MD, Matter K. The ZO-1-associated Y-box factor ZONAB regulates epithelial cell proliferation and cell density. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:423–432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becamel C, Figgs A, Poliak S, Dumuis A, Peles E, Bockaert J, Lubbert H, Ullmer C. Interaction of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2C receptors with PDZ10 of the multi-PDZ domain protein MUPP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12974–12982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergoffen J, Scherer SS, Wang S, Scott MO, Bone LJ, Paul DL, Chen K, Lensch MW, Chance PF, Fischbeck KH. Connexin mutations in X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Science. 1993;262:2039–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.8266101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, Ressort C. Connexins, gap junctions and cell-cell signalling in the nervous system. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997;9:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW, Ransom BR, Kunis DM, Gutnick MJ. Activity-dependent K+ accumulation in the developing rat optic nerve. Science. 1982;216:1341–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.7079771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne CB, Voelker T, Pichla SL, Bergelson JM. The coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor interacts with the Multi-PDZ domain protein-1 (MUPP1) within the tight junction. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48079–48084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl E, Manthey D, Chen Y, Schwarz H-J, Chang S, Lalley PA, Nicholson BJ, Willecke K. Molecular cloning and functional expression of mouse connexin30, a gap junction gene highly expressed in adult brain and skin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17903–17910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebnet K, Suzuki A, Ohno S, Vestweber D. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs): more molecules with dual functions? J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:19–29. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippov MA, Hormuzdi SG, Fuchs EC, Monyer H. A reporter allele for investigating connexin26 gene expression in the mouse brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;18:3183–3192. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki Y, Itoh M, Sasaki H, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1) is concentrated at tight junctions through its possible interaction with claudin-1 and junctional adhesion molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:455–461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holthoff K, Witte OW. Directed spatial potassium redistribution in rat neocortex. Glia. 2000;29:288–292. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(20000201)29:3<288::aid-glia10>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Sirkowski EE, Stickney JT, Scherer SS. Prenylation-defective human connexin32 mutants are normally localized and function equivalently to wild-type connexin32 in myelinating Schwann cell. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7111–7120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1319-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeansonne B, Lu Q, Goodenough DA, Chen YH. Claudin-8 interacts with multi-PDZ-domain protein 1 (MUPP1) and reduces paracellular conductance in epithelial cells. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003;49:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamasawa N, Sik A, Morita M, Yasumura T, Davidson KGV, Nagy JI, Rash JE. Connexin47 and connexin32 in gap junctions on oligodendrocyte somata, myelin sheaths, paranodal loops and Schmidt-Lanterman incisures: implications for ionic homeostasis and potassium siphoning. Neuroscience. 2005;136:65–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H, Ransom BR. Electrical coupling between astrocytes and between oligodendrocytes studied in mammalian cell cultures. Glia. 1988;1:64–73. doi: 10.1002/glia.440010108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Sun Q, Oglesbee M, Yoon SO. The role of ErbB2 signaling in the onset of terminal differentiation of oligodendrocytes in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5561–5571. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05561.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleopa AK, Orthmann JL, Enriquez A, Paul DL, Scherer SS. Unique distribution of the gap junction proteins connexin29, connexin32, and connexin47 in oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2004;47:346–357. doi: 10.1002/glia.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji P, Newman EA. Potassium buffering in the central nervous system. Neuroscience. 2004;129:1045–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapivinsky G, Medina I, Krapininsky L, Gapon S, Clapham DE. SynGAP-MUPP1-CaMKII synaptic complexes regulate p38 MAP kinase activity and NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic AMPA receptor potentiation. Neuron. 2004;43:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar NM, Gilula NB. The gap junction communication channel. Cell. 1996;84:381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Hertzberg EL, Nagy JI. Connexin32 in oligodendrocytes and association with myelinated fibers in mouse and rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;379:571–591. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970324)379:4<571::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Lynn BD, Olson C, Meier C, Davidson KG, Yasumura T, Rash JE, Nagy JI. Connexin29 expression, immunocytochemistry and freeze-fracture replica immunogold labelling (FRIL) in sciatic nerve. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;16:795–806. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ionescu AV, Lynn BD, Lu S, Kamasawa N, Morita M, Davidson KG, Yasumura T, Rash JE, Nagy JI. Connexin47, connexin29 and connexin32 co-expression in oligodendrocytes and Cx47 association with zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) in mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2004;126:611–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa PT, Mugnaini E. Cell junctions and intramembrane particles of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes: A freeze-frature study. Neuroscience. 1982;7:523–538. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa PT, Szuchet S, Mugnaini E. Cell-cell interactions of isolated and cultured oligodendrocytes: formation of linear occluding junctions and expression of peculiar intramembrane particles. J. Neurosci. 1984;4:3128–3139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-12-03128.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menichella DM, Goodenough DA, Sirkowski E, Scherer SS, Paul DL. Connexins are critical for normal myelination in the CNS. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5963–5973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05963.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menichella DM, Majdan M, Awatramani R, Goodenough DA, Sirkowski E, Scherer SS, Paul DL. Genetic and physiological evidence that oligodendrocyte gap junctions contribute to spatial buffering of potassium released during neuronal activity. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10984–10991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0304-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini E. Cell junctions of astrocytes, ependyma, and related cells in the mammalian central nervous system, with emphasis on the hypothesis of a generalized functional syncytium of supporting cells. In: Fedoroff S, Vernadakis A, editors. Astrocytes. I. New York Academic Press; 1986. pp. 329–371. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Patel D, Ochalski PAY, Stelmack GL. Connexin30 in rodent, cat and human brain: selective expression in gray matter astrocytes, co-localization with connexin43 at gap junctions and late developmental appearance. Neuroscience. 1999;88:447–468. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Rash JE. Connexins and gap junctions of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the CNS. Brain Res. Rev. 2000;32:29–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Li X, Rempel J, Stelmack G, Patel D, Staines WA, Yasumura T, Rash JE. Connexin26 in adult rodent CNS: demonstration at astrocytic gap junctions and co-localization with connexin30 and connexin43. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;441:302–323. doi: 10.1002/cne.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Ionescu AV, Lynn BD, Rash JE. Connexin29 and connexin32 at oligodendrocyte/astrocyte gap junctions and in myelin of mouse CNS. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003a;464:356–370. doi: 10.1002/cne.10797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Ionescu AV, Lynn BD, Rash JE. Coupling of astrocyte connexins Cx26, Cx30, Cx43 to oligodendrocyte Cx29, Cx32, Cx47: Implications from normal and connexin32 knockout mice. Glia. 2003b;44:205–218. doi: 10.1002/glia.10278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Dudek FE, Rash JE. Update on connexins and gap junctions in neurons and glia in the mammalian nervous system. Brain Res. Rev. 2004;47:191–215. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelles E, Butzler C, Jung D, Temme A, Gabriel H-D, Dahl U, Traub O, Stumpel F, Jungermann KJ, Zielasek, Toyka KV, Dermietzel R, Willecke K. Defective propagation of signals generated by sympathetic nerve stimulation in the liver of connexin32-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA. 1996;93:9565–9570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA. High potassium conductance in astrocyte endfeet. Science. 1986;233:453–454. doi: 10.1126/science.3726539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odermatt B, Wellershaus K, Wallraff A, Seifert G, Degen J, Euwens C, Fuss B, Bussow H, Schilling K, Steinhauser C, Willecke K. Connexin 47 (Cx47)-deficient mice with enhanced green fluorescent protein reporter gene reveal predominant oligodendrocytic expression of Cx47 and display vacuolized myelin in the CNS. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4549–4559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04549.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkand RK, Nicholls JG, Kuffler SW. Effect of nerve impulses on the membrane potential of glial cells in the central nervous system of amphibia. J. Neurophysiol. 1966;29:788–806. doi: 10.1152/jn.1966.29.4.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orthmann-Murphy JL, Freidin M, Fischer E, Scherer SS, Abrams CK. Two distinct heterotypic channels mediate gap junction coupling between astrocyte and oligodendrocyte connexins. J. Neurosci. 2007a;27:13949–13957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3395-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orthmann-Murphy JL, Enriquez AD, Abrams CK, Scherer SS. Loss-of-function GJA12/connexin47 mutations cause Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2007b;34:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orthmann-Murphy JL, Abrams CK, Scherer SS. Gap junctions couple astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-9027-5. Epub ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Miller R, Krane I, Vartanian T. The erbB2 gene is required for the development of terminally differentiated spinal cord oligodendrocytes. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:1245–1258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson HL, Garbern JY, Hoban TF, Krajewski KM, Lewis RA, Fischbeck KH, Grossman RI, Lenkinski R, Kamholz JA, Shy ME. Transient central nervous system white matter abnormality in X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:429–434. doi: 10.1002/ana.10305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penes M, Li X, Nagy JI. Expression of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and the transcription factor ZO-1-associated nucleic acid-binding protein (ZONAB/MsY3) in glial cells and co-localization at oligodendrocyte and astrocyte gap junctions in mouse brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:404–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliak S, Matlis S, Ullmer C, Scherer SS, Peles E. Distinct claudins and associated PDZ proteins form different autotypic tight junctions in myelinating Schwann cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002;159:361–371. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom BR, Kettenmann H. Electrical coupling, without dye coupling, between mammalian astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in cell culture. Glia. 1990;3:258–266. doi: 10.1002/glia.440030405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom CB, Ransom BR, Sontheimer H. Activity-dependent extracellular K+ accumulation in rat optic nerve: the role of glial and axonal Na+ pumps. J. Physiol., (Lond) 2000;522:427–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, Duffy HS, Dudek FE, Bilhartz BL, Whalen LR, Yasumura T. Grid-mapped freeze-fracture analysis of gap junctions in gray and white matter of adult rat central nervous system, with evidence for a ‘pan-glial’ syncytium that is not coupled to neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;388:265–292. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<265::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, Yasumura T, Dudek FE, Nagy JI. Cell-specific expression of connexins and evidence of restricted gap junctional coupling between glial cells and between neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001;15:1983–2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01983.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N, Avignone E, Même W, Koulakoff A, Venance L, Blomstrand F, Giaume C. Gap junctions and connexin expression in the normal and pathological central nervous system. Biol. Cell. 2002;94:457–475. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer SS, Deschenes SM, Xu Y-T, Grinspan JB, Fischbeck KH, Paul DL. Connexin32 is a myelin-related protein in the PNS and CNS. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:8281–8294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08281.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley RI, Walter NAR, Reilly CF, Buck KJ. Mpdz is a quantitative trait gene for drug withdrawal seizures. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:699–700. doi: 10.1038/nn1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitek B, Poschmann G, Schmidtke K, Ullmer C, Maskri L, Andriske M, Stichel CC, Zhu XR, Luebbert H. Expression of MUPP1 protein in mouse brain. Brain Res. 2003;970:178–187. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinsky G. Mixing of connexins in gap junction membrane channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9210–9214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutor B, Schmolke C, Teubner B, Schirmer C, Willecke K. Myelination defects and neuronal hyperexcitability in the neocortex of connexin32-deficient mice. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10:684–697. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.7.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis M, Söhl G, Eiberger J, Willecke K. Emerging complexities in identity and function of glial connexins. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenberg B, Schuelke M, Ruschendorf F, Ruf N, Kaindl AM, Henneke M, Thiele H, Stoltenburg-Didinger G, Aksu F, Topaloglu H, Nurnberg P, Hubner C, Weschke B, Gartner J. Mutations in the gene encoding gap junction protein α12 (connexin46.6) cause Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-Like disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:251–260. doi: 10.1086/422763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmer C, Schmuck K, Figge A, Lubbert H. Cloning and characterization of MUPP1, a novel PDZ domain protein. FEBS Lett. 1998;424:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venance J, Cordier J, Monge M, Zalc B, Glowinski J, Giaume C. Homotypic and heterotypic coupling mediated by gap junctions during glial cell differentiation in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995;7:451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallraff A, Kohling R, Heinemann U, Theis M, Willecke K, Steinhauser C. The impact of astrocytic gap junctional coupling on potassium buffering in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2006;17:5438–5447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0037-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TW, Bruzzone R. Multiple connexin proteins in single intercellular channels: connexin compatibility and functional consequences. J. Bioenerg. Biomem. 1996;28:339–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02110110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolburg H, Rohlmann A. Structure-function relationships in gap junctions. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1995;157:315–373. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Ochalski PAY, Hertzberg EL, Nagy JI. On the organization of astrocytic gap junctions in the brain as suggested by LM and EM immunocytochemistry of connexin43 expression. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;302:853–883. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials