Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer gene 3 (PCA3) encodes a prostate-specific messenger RNA (mRNA) that serves as the target for a novel urinary molecular assay for prostate cancer detection. Our objective is to evaluate the ability of PCA3 in addition to serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) to predict cancer detection by extended template biopsy.

Methods

From September 2006 to December 2007, whole urine samples were collected after attentive digital rectal exam from 187 men prior to ultrasound-guided 12-core prostate biopsy in a urology outpatient clinic. Urine PCA3/PSA mRNA ratio scores were measured within one month and serum PSA within six months of biopsy. These were related to cancer positivity on biopsy.

Results

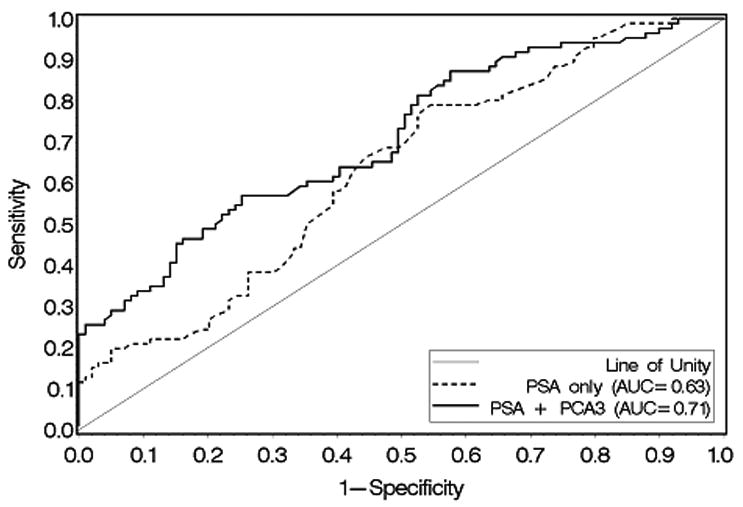

Overall, 87/187 (46.5%) biopsies were positive for cancer. Sensitivity and specificity of PCA3 score ≥35 for positive biopsy were 52.9% and 80.0%; positive and negative predictive values were 69.7% and 66.1%. Using receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis, PSA alone resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.63 for prostate cancer detection; PSA + PCA3 score resulted in an AUC of 0.71. The likelihood of prostate cancer detection rose with increasing PCA3 score ranges (p>0.0001), providing possible PCA3 score parameters for stratification into low, moderate, high, and very high risk groups for biopsy positivity.

Conclusion

Adding PCA3 to serum PSA improves prostate cancer prediction. Use of PCA3 in a clinical setting may help risk-stratify patients for biopsy and cancer detection, although a large-scale validation study is needed to address assay standardization, optimal cut-off values and appropriate patient populations.

Keywords: prostatic neoplasms, genes, biopsy, urine

Introduction

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has revolutionized the evaluation and treatment of prostate cancer (PCa) since its initial discovery in 19791, resulting in increased cancer detection and subsequent downward stage migration2. Yet there remains significant debate regarding optimal PSA thresholds for cancer detection3. To refine risk stratification, derivative measurements such as percent free PSA4, 5, age-specific PSA ranges6, and PSA velocity7 have been proposed, but are constrained by similar limitations as PSA itself. Namely, non-malignant conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatitis can cause PSA elevations8 and result in unnecessary and repeated prostate biopsies. These limitations of PSA as a prognostication tool have led to an intensive search for other PCa biomarkers.

Prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3, also known as Differential Display Code 3 or DD3) is a prostate-specific gene that was present in 95% of prostate cancer samples initially studied9, and significantly over-expressed in cancer versus benign tissue10. PCA3 is known to be a non-coding messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) with no resultant protein. Clinically, PCA3 mRNA is detectable in the urine and prostatic fluid of men with PCa. PCA3 mRNA levels are independent of prostate volume and serum PSA, but may be higher with larger, more aggressive tumors11. PCA3 now serves as the target for a novel urinary molecular assay for PCa detection12-15. This clinical test requires urine to be collected after an attentive digital rectal exam (DRE) to increase the number of prostate cells shed into the urine6, 7, and all versions of this assay are reported as a ratio of PCA3 mRNA/PSA mRNA.

Currently, several urinary PCA3 assays exist, with initial feasibility studies in Europe relying upon a time-resolved fluorescence-based (TRF), quantitative RT-PCR-based methodology. The only commercially available PCA3 assay in the United States uses whole urine rather than sediment and relies upon magnetic microparticle capture, transcription-mediated RNA amplification and hybridization protection assay detection of PSA and PCA3 mRNA. With an initial cut-off value set at 50, this assay demonstrated a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 79%13. The TRF-based version has demonstrated sensitivities of 65-67%, specificities of 66-83%, and negative predictive values of 80-90%10, 15. The nucleic acid sequence-based amplification urine uPM3™ assay has demonstrated similar results; with a cutoff of 0.5, sensitivity ranged from 66-82%, specificity from 76-89%, and negative predictive value from 84-87%12, 14. PCA3 is not intended to be used alone for prostate cancer screening at this time, and thus far, all studies have investigated its utility in conjunction with PSA and other biomarkers.

While initial results from these studies are promising, they cannot be generalized to all populations as study cohorts were comprised of only pre-screened patients undergoing biopsy for an elevated PSA. The unrestricted widespread use of novel biomarkers, such as PCA3, without consideration for the consequences may result in unanticipated consequences16. Our aim is to describe the ability of urine PCA3 combined with serum PSA to improve PCa detection on biopsy versus serum PSA alone, and discuss potential downstream effects of this new biomarker. We will examine the available clinical evidence and illustrate the benefits and limitations of using PCA3 in clinical practice.

Methods

Patient Selection and Sample Processing

From September 2006 to December 2007, whole urine specimens were collected from men after attentive DRE and prior to ultrasound-guided 12-core prostate biopsy, according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan. All men presenting for prostate biopsy were approached about participation in this prospective database study. All prostate biopsies were performed within one month of DRE and urine specimen collection, and both prostate exams and biopsies were completed by a single surgeon (JTW) at a urologic outpatient satellite clinic. Inclusion criteria included adult males undergoing prostate biopsy for any of the following reasons: elevated or rising PSA, <15% free PSA, prostate cancer risk factors, prior atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP) or high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN), or abnormal DRE. Exclusion criteria included history of prostate cancer or prior prostate surgery, urine not collected after DRE and prior to prostate biopsy, inadequate prostate biopsy with less than 12 cores, or men who declined to consent for participation in the study.

An attentive DRE included firm pressure on the prostate from base to apex and from lateral to median lobe, with three strokes per lobe and enough pressure to slightly depress the prostate surface17. Following DRE, patients collected their initial void of 20-30 milliliters (ml) of urine, and this was processed for the Gen-Probe assay performed off-site at Molecular Profiling Institute. Clinic specimen processing involved transferring urine into a transport tube containing a detergent-based stabilization buffer, and keeping all specimens at or below 30°C. PCA3 and PSA mRNAs were isolated from urine and underwent transcription-mediated amplification; the products were detected with the hybridization protection Gen-Probe assay using target-specific acridinium ester-labeled probes. PCA3 scores were reported as a quantitative PCA3/PSA mRNA ratio × 1000 to normalize PCA3 to the amount of prostate RNA present in the urine sample. Cases with insufficient PSA mRNA were considered inconclusive and excluded. A PCA3 score of ≥35 was considered positive (per laboratory standard), and serum PSA levels were measured within six months prior to prostate biopsy.

Prostate biopsy was performed within one month following urine collection for the assay. At minimum, a transrectal ultrasound-guided twelve-core biopsy utilizing a sextant template was performed for all patients, with additional biopsies directed to lesions discovered on palpation or imaging, or as clinically indicated. Prostate parameters and total volume were measured at time of biopsy.

Data Analysis

Clinical data, including final prostate biopsy pathology results, were prospectively collected using explicit data collection tools. Prognostic ability (sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values) of the PCA3 test was determined by cross-tabulation. Logistic regression models were used to produce data for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, with area under the curve (AUC) values determined from the model c-statistic. The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test was used to test for association between ordinal PCA3 groupings and positive biopsy rate. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to explore the association between PCA3 and prostate volume. All tests were performed at the 5% significance level using SAS statistical software (v.9.1, Cary, NC).

Results

Overall, 192 men consented to the research study and submitted whole urine samples for PCA3 analysis; of these, 187 samples yielded sufficient RNA for analysis, resulting in a specimen informative rate of 97.4%. The demographics of our patient population are detailed in Table 1. The mean age of men biopsied was 62 years, and mean prostate volume was 59.4 grams. Biopsy was performed for elevated PSA in most patients, and 16% of patients had an abnormal DRE. Most patients underwent biopsy for the first time. The mean PSA was 8.7 (SD, 12.4) ng/ml, and the mean PCA3 score was 41.1 (SD, 63.3). Overall, prostate cancer was diagnosed by biopsy in 87 (46.5%) men, with most men harboring Gleason 6 or 7 prostate cancer, and a quarter harboring Gleason 8 disease or higher. There was no relationship between PCA3 score and prostate volume (p=0.26). The Spearman rank correlation between PCA3 and biopsy Gleason score was 0.25, and between PCA3 and percent positive biopsy cores was 0.43.

Table 1.

Demographics for 187 Men Undergoing Prostate Biopsy

| Parameter | Overall |

|---|---|

| No. Patients | 187 |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 62.0 (8.3) |

| (range) | (44-86) |

| Prostate volume (grams) | |

| Mean (SD) | 59.4 (39.2) |

| (range) | (9-241) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 171 (91.5%) |

| Black | 10 (5.3%) |

| Other | 6 (3.2%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 181 (97%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (1.1%) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.1%) |

| Family history of PCa | |

| Yes | 35 (18.7%) |

| Reason for biopsy | |

| Elevated PSA | 166 (88.8%) |

| HGPIN | 11 (5.9%) |

| ASAP | 4 (2.1%) |

| Other | 19 (10.2%) |

| Previous biopsies | |

| None | 136 (72.7%) |

| One or more | 51 (27.3%) |

| Biopsy Positive | 87 (46.5%) |

| Gleason 6 | 32 (36.8%) |

| Gleason 7 | 33 (37.9%) |

| Gleason 8 or higher | 22 (25.3%) |

| Biopsy Stage | |

| T1c | 60 (69.0%) |

| T2a | 19 (21.8%) |

| T2b | 4 (4.6%) |

| T2c | 1 (1.1%) |

| T3a or higher | 3 (3.4%) |

The overall sensitivity and specificity of PCA3 score ≥35 for positive biopsy in this cohort were 52.9% and 80.0%, respectively. The positive predictive value of PCA3 score for PCa was 69.7% and the negative predictive value was 66.1%. Using ROC curve analysis, serum PSA alone resulted in an AUC of 0.63 for positive diagnosis of prostate cancer, while the combination of PSA + PCA3 score resulted in an improved AUC of 0.71 (Figure 1). Logistic regression analysis showed that PCA3 (p=0.001) was independently associated with positive biopsy after adjusting for the effect of PSA (p=0.07). Additionally, PCA3 (p=0.003) remained a significant predictor of prostate cancer risk after adjusting for other clinical factors, including age, family history, number of prior biopsies, DRE results, and PSA. When the cohort was further divided into men undergoing initial or repeat biopsy, both PSA (p=0.02) and PCA3 (p=0.004) were able to independently predict positive biopsy in the initial biopsy cohort (n=136).

Figure 1. ROC Curve Analysis for serum PSA versus serum PSA + urine PCA3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve comparing serum PSA alone (dashed line) versus serum PSA + urine PCA3 score (solid line) as a predictor of positive prostate biopsy. Area under the curve (AUC) for serum PSA alone was 0.63 versus 0.71 for serum PSA + urine PCA3 score.

Regarding PSA breakdown, 151 patients had a PSA< 10, and 34 had a PSA >10. The AUC for PCA3 + PSA can be calculated for patients with a PSA<10 (0.69) and with a PSA>10 (0.90). The performance characteristics in the group with a PSA<10 is similar to that for the overall group (0.71), indicating that the addition of PCA3 is still useful in the cohort with a PSA<10.

Figure 2 illustrates a significant rise in the proportion of positive biopsies with increasing PCA3 score ranges (Mantel-Haenszel chi-square p>0.0001), providing clinically meaningful parameters for stratification into low (PCA3 score<5, 10.5% positive biopsy), moderate (PCA3 score 5-34, 38.2% positive biopsy), high (PCA3 score 35-100, 64.7% positive biopsy), and very high (PCA3 score >100, 86.7% positive biopsy) risk groups for positive biopsy. From this data, the overall utility rate for the PCA3 score is 45%, signifying that 85/187 men with either low or high PCA3 score ranges (e.g., <5, 35-100, and >100) would experience a change in their cancer detection rate relative to their pre-PCA3 score probability of cancer detection (46.5% in this cohort).

Figure 2. PCA3 Score and Relation to %Positive Biopsy.

There is a significant rise in the proportion of positive biopsies with increasing PCA3 score ranges (p>0.0001). A PCA3 score of 35 is used as a cut-off.

Discussion

The limitations of serum PSA alone for the detection and risk stratification of prostate cancer have been explored extensively. Through conventional PSA surveillance, clinicians are both missing patients with prostate cancer and a non-elevated PSA, and performing a large number of unnecessary biopsies to detect a smaller proportion of questionably clinically significant tumors. Using a standard cut-off of 4.0ng/ml, 15% of men who have a PSA <4.0ng/ml have biopsy-proven PCa, with a subsequent 15% of those men harboring cancer that is Gleason 7 or higher3. Additionally, PSA has not been able to predict lethal prostate cancer with precision18. These issues remain points of controversy, long after PSA had been disseminated widely for screening and evaluation. This sequence of events should prompt careful planning for next-generation PCa biomarkers to ensure their measured dissemination into clinical practice.

PCA3 is currently the only urinary PCa biomarker to progress past the initial discovery phases and be translated into a commercial assay. Despite promising initial studies, the optimal clinical utility of PCA3 remains unclear. Reviewed here are a number of clinical scenarios which will inevitably arise as PCA3 is disseminated into practice.

Screening

Prostate cancer screening is performed currently with annual digital rectal exams and the serum PSA test. A threshold of 4 ng/ml for serum PSA is typically used as the upper limit of normal, although optimal screening levels remain controversial3. While a new biomarker could ultimately be adapted for screening, there have been no studies to date investigating urine PCA3 as a screening tool. Similarly, all published PCA3 studies have investigated its performance in pre-screened populations of men referred for biopsy, often for an elevated PSA, and there have been no head-to-head studies comparing PSA to PCA3 in a general population. Thus, there is no empiric evidence at this time to support supplanting serum PSA with the urine PCA3 assay in a screening context, and wide-spread use of PCA3 in the absence of PSA would be ill-advised. Moreover, the utility of PCa screening in general is still questioned; the results of the randomized, multi-center Prostate Lung Colon Ovarian (PLCO) trial are anxiously awaited to determine the benefit of PCa screening in decreasing cancer-specific mortality19.

Adjunct to PSA for Initial Prostate Biopsy

An elevated serum PSA >4.0ng/ml or focal prostate nodule often prompt referral for transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Recent studies investigating PCA3 have shown that in a pre-screened population referred for biopsy, the urine PCA3 score correlates well with the probability of cancer on biopsy. Several studies have demonstrated a significant difference in the median PCA3 score between healthy, biopsy-negative, and biopsy-positive groups11, 13. The PCA3 score also demonstrated a direct correlation with the probability of positive biopsy in a study by Deras et al.20; this was consistent with our cohort as well. These PCA3 risk groups may provide possible parameters for risk for positive biopsy when used as a PSA adjunct. In our cohort, the combination of PSA and PCA3 resulted in superior PCa prediction over PSA alone. In a logistic regression algorithm by other authors, incorporation of PCA3 into a model with serum PSA, prostate volume, and DRE results improved the AUC from 0.69 for PCA3 alone to 0.75 (p=0.0002)20. Here, we also demonstrate that PCA3 remains an independent predictor for positive biopsy after adjusting for multiple clinical factors.

Furthermore, PCA3 may be valuable because its performance characteristics demonstrate stability across serum PSA levels and independence from prostate volume20. Thus, PCA3 may potentially be used to determine risk for positive biopsy across all PSA ranges. More recently, the PCA3 test was found to differentiate men with low-risk, low-volume prostate cancer11, although these data have yet to be verified independently.

Adjunct to PSA for Repeat Prostate Biopsy

Repeat prostate biopsy is indicated for patients who have a prior negative biopsy but continue to have an elevated serum PSA or abnormal DRE, or for follow-up of previous pathologic diagnoses of pre-malignant HGPIN or ASAP. In our series, more than a quarter of all biopsies were repeat biopsies. It remains unclear when and how often to repeat a prostate biopsy. There is a documented decline in cancer detection with each successive biopsy21, and for men with persistently elevated PSA who are undergoing repeat biopsy, Marks and colleagues demonstrated limited reliability of PSA in PCa prediction and a significant superiority of the urine PCA3 assay in 226 men undergoing repeat biopsy (AUC 0.68 for PCA3 versus 0.52 for serum PSA, p<0.01)22. Another study has found as a sub-analysis, the diagnostic accuracy of PCA3 was similar between men undergoing first versus repeat biopsy20, although there has been no similar study investigating PCA3 performance in only men undergoing repeat biopsy. Our own analysis for predictive ability of PCA3 with PSA in the repeat biopsy cohort failed to confirm the findings of Marks et al., though this may be secondary to a small repeat biopsy sample size. There is a suggestion that PCA3 may significantly improve the pre-test probability for men considered for a repeat biopsy22, though this also remains unconfirmed.

Post-Treatment Cancer Surveillance

Clinically localized prostate cancer is often treated with radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy (brachytherapy or external beam); serum PSA is the primary means of monitoring for biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy, tumor persistence or treatment failure after radiotherapy. In the initial descriptive study of the PCA3 assay, PCA3 and PSA signals were detected at only background levels in 20/21 men who had undergone prostatectomy and mRNA copy numbers were insufficient for analysis; the only post-prostatectomy specimen which yielded measurable PCA3 and PSA signals had developed a biopsy-positive recurrence13. No study has since investigated PCA3 use in a post-prostatectomy cohort, and unlike PSA in biochemical recurrence, there is no current data to support using PCA3 for post-treatment PCa surveillance, although this is biologically plausible.

Potential Impact and Limitations of PCA3 for Risk Stratification

The strongest evidence available would support the use of PCA3 as an adjunct to PSA to determine risk for positive biopsy. For example, a 56 year-old male patient is found to have an elevated PSA of 4.1 ng/ml on annual PSA testing, with no obvious nodule palpable on DRE. Previous PSA levels have been <4 ng/ml, and he has had no episodes of prostatitis. His likelihood of positive prostate biopsy is 47% in our cohort. In this scenario, the PCA3 assay may be helpful in determining risk for positive biopsy. If his PCA3 score returns <5, our data suggest a positive biopsy rate of approximately 10%, significantly lower than our overall positive biopsy rate. Alternatively, if his PCA3 score returns 35-100 or >100, his rate of positive biopsy increases to 65% or 87%, respectively. Even taking into account some variability in the overall positive biopsy rate from different cohorts, these changes in pre- and post-PCA3 assay probability for half the patients in this cohort can impact significantly the mutual decision to continue PSA surveillance or proceed with repeat biopsy.

While PCA3 appears to improve PCa detection, it has inherent limitations. There is no international standard for the urinary assay and all methods rely upon urine obtained immediately after an attentive DRE. This is not unlike PSA for which there are several assays; and reported values vary based upon assay method of PSA measurement used23, 24. Specimen informative rates are generally high, but a small proportion of men will have to provide repeat urine samples after an inadequate DRE, to express a sufficient number of prostate cells. Furthermore, it is unclear if a suboptimal DRE or a small peripheral tumor producing a minimal number of shed cells into the urine can result in a falsely negative PCA3 score; and while no relationship has been found between PCA3 score and prostate volume, a recent report suggests that PCA3 RNA can be detected in HGPIN and benign tissue proximal to neoplastic glands, suggesting precursor molecular changes25. It has yet to be determined if this can result in false positive results with HGPIN pathology. Lastly, while a PCA3 score of ≥35 has been adopted as a preliminary positive cut-point, 33.9% of men in our sample with a PCA3 score <35 had PCa on biopsy, a reminder that risk remains a continuous, rather than dichotomous variable.

In spite of the evidence for PCA3, its exact role in clinical practice has yet to be truly validated. With regard to phases of biomarker validation26, PCA3 has passed the initial preclinical phase of laboratory exploratory study and clinical assay development, and is being investigated currently in prospective trials. Before PCA3 becomes propagated widely as a novel biomarker for PCa detection or screening, a bona-fide validation study should be conducted to confirm findings from limited single-institution studies, refine assay standardization, and define the most relevant patient population for application. It should be recognized that existing studies of PCA3 are limited by their lack of multi-institution accrual, small sample sizes, and potential selection bias.

In conclusion, there is mounting evidence to suggest that a combination of urine PCA3 and serum PSA is superior to PSA alone for detection of prostate cancer, though these studies are limited to pre-screened patients with elevated or rising PSA levels. PCA3 may serve as a useful adjunct to determine risk for positive prostate biopsy, and in counseling men contemplating repeat biopsy; although the question remains: are we merely contributing to the over-diagnosis of prostate cancer that is not clinically significant? To date, there is no definitive evidence demonstrating that PCA3 prognosticates for lethal prostate cancer, and in the absence of such evidence, these biomarkers may only contribute to the continued over-diagnosis of prostate cancer. Nevertheless, if our goals are to minimize unnecessary prostate biopsies and optimize early prostate cancer detection, PCA3 appears worthy of systematic large-scale validation to clarify its role as a passing trend or as a valuable next-generation biomarker for prostate cancer detection.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: Prostate SPORE (grant P50CA69568 to A.M.C.), Early Detection Research Network (grant U01 CA111275-01 and U01 CA113913 to A.M.C. and J.T.W.).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: J.T.W. and A.M.C. are consultants for Gen-Probe, Inc; K.J.W. is employed by Ameripath, and serves on the scientific advisory board for Gen-Probe, Inc. and Onconome, Inc.

References

- 1.Wang MC, Valenzuela LA, Murphy GP, Chu TM. Purification of a human prostate specific antigen. Invest Urol. 1979;17(2):159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, Basler JW. Detection of organ-confined prostate cancer is increased through prostate-specific antigen-based screening. JAMA. 1993;270(8):948–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson IM, Pauler DK, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, Parnes HL, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or =4.0 ng per milliliter. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2239–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalona WJ, Partin AW, Slawin KM, Brawer MK, Flanigan RC, Patel A, et al. Use of the percentage of free prostate-specific antigen to enhance differentiation of prostate cancer from benign prostatic disease: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1542–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1542. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stenman UH, Leinonen J, Alfthan H, Rannikko S, Tuhkanen K, Alfthan O. A complex between prostate-specific antigen and alpha 1-antichymotrypsin is the major form of prostate-specific antigen in serum of patients with prostatic cancer: assay of the complex improves clinical sensitivity for cancer. Cancer Res. 1991;51:222–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oesterling JE, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Guess HA, Girman CJ, Panser LA, et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen in a community-based population of healthy men. Establishment of age-specific reference ranges. JAMA. 1993;270:860–4. see comment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter HB, Pearson JD, Metter EJ, Brant LJ, Chan DW, Andres R, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men with and without prostate disease. JAMA. 1992;267:2215–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morote Robles J, Ruibal Morell A, Palou Redorta J, de Torres Mateos JA, Soler Rosello A. Clinical behavior of prostatic specific antigen and prostatic acid phosphatase: a comparative study. Eur Urol. 1988;14:360–6. doi: 10.1159/000472983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bussemakers MJ, van Bokhoven A, Verhaegh GW, Smit FP, Karthaus HF, Schalken JA, et al. DD3: a new prostate-specific gene, highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5975–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hessels D, Klein Gunnewiek JM, van Oort I, Karthaus HF, van Leenders GJ, van Balken B, et al. DD3(PCA3)-based molecular urine analysis for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2003;44:8–15. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakanishi H, Groskopf J, Fritsche HA, Bhadkamkar V, Blase A, Kumar SV, et al. PCA3 molecular urine assay correlates with prostate cancer tumor volume: implication in selecting candidates for active surveillance. J Urol. 2008;179:1804–10. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fradet Y, Saad F, Aprikian A, Dessureault J, Elhilali M, Trudel C, et al. uPM3, a new molecular urine test for the detection of prostate cancer. Urology. 2004;64:311–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groskopf J, Aubin SM, Deras IL, Blase A, Bodrug S, Clark C, et al. APTIMA PCA3 molecular urine test: development of a method to aid in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1089–95. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.063289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tinzl M, Marberger M, Horvath S, Chypre C. DD3PCA3 RNA analysis in urine--a new perspective for detecting prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2004;46:182–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Gils MP, Hessels D, van Hooij O, Jannink SA, Peelen WP, Hanssen SL, et al. The time-resolved fluorescence-based PCA3 test on urinary sediments after digital rectal examination; a Dutch multicenter validation of the diagnostic performance. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:939–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins MM, Barry MJ. Controversies in prostate cancer screening. Analogies to the early lung cancer screening debate. JAMA. 1996;276:1976–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gen-Probe PCA3 Assay. Gen-Probe, Inc.; 2006-2007. Document No.: 500614 Rev. B. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fall K, Garmo H, Andren O, Bill-Axelson A, Adolfsson J, Adami HO, et al. Prostate-specific antigen levels as a predictor of lethal prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:526–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andriole GL, Reding D, Hayes RB, Prorok PC, Gohagan JK. The prostate, lung, colon, and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: Status and promise. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:358–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deras IL, Aubin SMJ, Blase A, Day JR, SKoo S, Partin AW, et al. PCA3: a molecular urine assay for predicting prostate biopsy outcome. J Urol. 2008;179:1587–92. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djavan B, Remzi M, Marberger M. When to biopsy and when to stop biopsying. Urol Clin North Am. 2003;30:253–62. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marks LS, Fradet Y, Deras IL, Blase A, Mathis J, Aubin SM, et al. PCA3 molecular urine assay for prostate cancer in men undergoing repeat biopsy. Urology. 2007;69(3):532–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray MA, Cooke RR, Weinstein P, Nacey JN. Comparability of serum prostate-specific antigen measurement between the Roche Diagnostics Elecsys 2010 and the Abbott Architect i2000. Ann Clin Biochem. 2004;41:207–12. doi: 10.1258/000456304323019578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kort SA, Martens F, Vanpoucke H, van Duijnhoven HL, Blankenstein MA. Comparison of 6 automated assays for total and free prostate-specific antigen with special reference to their reactivity toward the WHO 96/670 reference preparation. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1568–74. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.069039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popa I, Fradet Y, Beaudry G, Hovington H, Beaudry G, Tetu B. Identification of PCA3 (DD3) in prostatic carcinoma by in situ hybridization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:1121–7. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson ML, Thornquist M, et al. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1054–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]