SUMMARY

Planar polarity is a fundamental property of epithelia in animals and plants. In Drosophila it depends on at least two sets of genes: one set, the Ds system, encodes the cadherins Dachsous (Ds) and Fat as well as the Golgi protein Four-jointed. The other set, the Stan system, encodes Starry night (Stan or Flamingo) and Frizzled. The prevailing view is that the Ds system acts via the Stan system to orient cells. However, using the Drosophila abdomen, we find instead that the two systems operate independently: each confers and propagates polarity, and can do so in the absence of the other. We ask how the Ds system acts; we find that either Ds or Ft is required in cells that send information and show that both Ds and Ft are required in the responding cells. We consider how polarity may be propagated by Ds-Ft heterodimers acting as bridges between cells.

INTRODUCTION

Most organisms are built of epithelia consisting of cells that are both asymmetric in the basal/apical axis and within the plane of the cell sheet (Fanto and McNeill, 2004; Grebe, 2004). Planar cell polarity (PCP) is shown by the orientation of structures such as hairs in insects (Lawrence, 1966; Strutt, 2003; Saburi and McNeill, 2005) as well as cilia (Eaton, 1997) and stereocilia in vertebrates (Lewis and Davies, 2002). PCP is also implicated in convergent extension in vertebrate embryos (Wallingford et al., 2002). Genetic and molecular studies in Drosophila have identified proteins essential for PCP and these are generally conserved in vertebrates (Klein and Mlodzik, 2005). Here we study Drosophila and build a new logical structure for PCP.

There are two sets of genes involved in PCP which we name the Stan system and the Ds system. The Stan system depends on a cadherin receptor-like molecule, Starry Night ( Chae et al., 1999; Usui et al., 1999), as well as Frizzled (Fz) (Adler et al., 1997), a receptor for Wnts (Wodarz and Nusse, 1998). Other proteins in the Stan system are Diego, Dishevelled, Van Gogh (also called Strabismus), and Prickle (Pk). There are several ideas of how the Stan system might function. A popular model proposes that PCP is determined by asymmetrically localised complexes of “core” (Stan system) proteins in cell membranes (Strutt, 2002). This asymmetry, which has been observed in some epithelial cells, would be oriented by an unknown graded signal (“factor X”, Struhl et al., 1997a). Propagation of PCP would be driven by feedback between proteins, the asymmetrical arrangement of proteins in one cell affecting localisation in neighbouring cells (Tree et al., 2002; Amonlirdviman et al., 2005). We have argued (Lawrence et al., 2004) that this view is largely incorrect, and base our opinion mainly on two pieces of evidence: First, cells that completely lack the Fz protein can be polarised by their neighbours — yet, in the asymmetry model the orientation of each cell should probably depend on the differential accumulation and activity of Fz intrinsic to that cell (Tree et al., 2002). Second, flies that lack one component of the feedback mechanism of the Stan system, Pk, lose the asymmetric localisation of the other core proteins — yet, in these flies, disparities in the level of Fz still propagate polarity from cell to cell (Lawrence et al., 2004). This result with Pk has been confirmed in the wing and even extended to wings lacking dishevelled (Strutt and Strutt, personal communication).

Our alternative model for the Stan system has four main tenets (Lawrence et al., 2004): (i) Fz activity is normally gently graded from one cell to the next as a response to factor X. (ii) The level of Fz activity in any one cell is adjusted towards the levels of its neighbours — this tenet explains how experimentally induced disparities in Fz activity can induce changes in polarity that propagate for several cells. (iii) A cell becomes polarised by comparing its own level of Fz activity with that of its various neighbouring cells, pointing hairs towards the neighbour with the lowest level and away from the neighbour with the highest level. (iv) The Fz activity levels of neighbours are perceived through intercellular homodimers made by Stan and, accordingly, propagation of polarity depends on having Stan molecules in both the sending and responding cells.

The second set of genes that acts in PCP, the Ds system, encodes two atypical cadherins, Dachsous (Ds) and Fat (Ft), as well as a resident Golgi protein, Four-jointed (Fj) (Strutt et al., 2004). The Ds system, like the Stan system, orients cellular outgrowths. However, unlike the Stan system, it also affects the orientation of cell divisions and organ shape as well as having some input into growth (Bryant et al., 1988; Baena-López et al., 2005). In an important paper, Yang et al (2002) proposed that, in the eye, the polarity genes constitute a linear pathway in which morphogens, such as Wingless (Wg), orient the Ds system. In the eye, this system consists of gradients of Fj and Ds (Simon, 2004) with Fj first repressing Ds activity and Ds then repressing Ft activity. Yang and colleagues argued that Ft then activates Fz to polarise the Stan system. Thus, the graded activity of the Ds system constitutes factor X, and the Stan system transduces X to polarise cells. This single pathway model of PCP has become accepted and now prevails in the literature on PCP (Adler, 2002; Strutt and Strutt, 2002; Ma et al., 2003; Uemura and Shimada, 2003; but see discussion in Klein and Mlodzik, 2005; Strutt and Strutt, 2005a; Strutt and Strutt, 2005b).

Experiments in the Drosophila abdomen give comparable results to those in the eye. A morphogen, Hedgehog (Hh), appears to be responsible for activity gradients of Fj, Ds and Ft (Casal et al., 2002). As in the eye, the Stan system acts in PCP but there is no evidence as to whether there is, or is not, a single pathway: Hh -> Ds system -> Stan system. Experimentally, the abdomen has some advantages over the eye. For example, in the eye, PCP is revealed in the arrangement of cells in entire ommatidia; each an ensemble of photoreceptors, lens and pigment cells. In the abdomen, the polarity of each cell is shown directly by the orientation of hairs produced by that cell alone. Here, we use this advantage to test whether the Ds and Stan systems act as part of a single linear pathway. Our main conclusion is that they do not and that each system deploys a different mechanism to polarise cells and to propagate polarity from cell to cell.

RESULTS

The dorsal abdomen

The dorsal epidermis of the adult abdomen is segmented and divided into a chain of anterior (A) and posterior (P) compartments. The epithelium secretes pigmented plates (tergites), made by the A compartments and separated by strips of more flexible cuticle; most of the cells make cuticular hairs or bristles that point posteriorly. Cells in the P compartment secrete the morphogen Hh that controls cell polarity (and cell type) in the A compartment (Struhl et al., 1997a; Lawrence et al., 1999). Here, we focus on the A compartment — our current view is summarised in Fig 1. The vectors and extents of the gradients shown in Fig 1 are derived from experiments with genetic mosaics: for example near the front of a clone of ds− cells, wildtype hairs point the “wrong” way (forwards). This, we argue, is because the normal grade of Ds activity (high at the back of the A compartment, low at the front), is locally reversed. At the back of the clone, the effects are concordant with the normal grade and therefore polarity is not altered. Similarly, clones of cells in which ds is overexpressed (henceforth called UAS.ds clones) make the hairs behind the clone point forwards, because, there, the normal grade of Ds activity is reversed. The corresponding experiments with fj and ft give similar results, except that the sign is opposite (ft− and fj− clones cause the polarity of wildtype cells to reverse behind the clones, and UAS.fj (Casal et al., 2002) and UAS.ft clones reverse in front of the clones). For the experiments described below, the genotypes are referred to by number (1-92) and presented in the Supplemental Data; the Supplemental Data also includes a diagrammatic précis of the results.

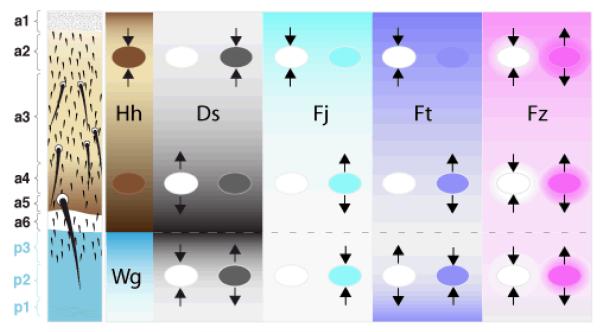

Figure 1. A summary of polarising gradients in the abdomen.

On the left, the pattern of the cuticle is shown with the types of cuticle in the A (a1-a6) and in the P compartment (blue, p3-p1). The compartments are patterned by gradients; Hh in A and Wg in P (Struhl et al., 1997a; Lawrence et al., 2002). The U-shaped Hh gradient sets up the Ds gradients and also the activity gradients of Fj and Ft that are shown in the next three columns (Casal et al., 2002). Clones that lack or overexpress a gene affect the polarity of wildtype cells around as shown (arrows). For example, the leftmost column shows ptc− en− clones, which constituitively activate the Hh transduction pathway and produce reversal of the wildtype cells behind the clones (but only when they are in the middle of the A compartment, where they cause a discrepancy in the Hh transduction pathway between the clone and the surround). The next column shows the gradient of Ds: loss of ds reverses the polarity of cells in front of clones at the back of the A compartment (where the level of Ds activity is high) but has no effect when the clones are located at the front of the A compartment (where Ds activity is low). Overexpression of Ds has the opposite effects: repolarising only at the front of the A compartment. The effects of clones involving Fj and Ft are as shown. By contrast to the other genes, clones involving Fz have similar effects wherever they are situated. We imagine there is an alteration in Fz activity that spreads out from the clones as the surrounding wildtype cells readjust their levels of Fz activity by an averaging process (Lawrence et al., 2004); this is symbolised by the haloes. This difference of clonal behaviour points again to a distinction between the Ds and Stan systems.

Is there a linear and causal relationship between the Ds and Stan systems?

If the linear relationship were correct, cells that lack the Stan system should not support propagation of polarity changes caused by disparities in the Ds system. Indeed, in the eye, the repolarising ability of fj−, ds− and ft− clones all appear to be blocked in the absence of fz (Yang et al., 2002 but see Discussion). However, experiments in the abdomen lead to a different conclusion. By all previous tests, Stan is required in both “sending” and “receiving” cells for the transmission of polarising information induced by differences in Fz activity: stan−, stan− fz− and stan− UAS.fz clones do not repolarise their wildtype neighbours (genotype 1 and Lawrence et al., 2004) nor do UAS.fz UAS.stan clones repolarise stan− cells (genotype 2). Similarly, stan− cells are not repolarised by UAS.fz cells (genotype 3, Fig 2B). These experiments show that, with respect to repolarisation, the Stan system is completely disabled by the stan- genotypes we have used. Nevertheless, we find UAS.ft clones in stan− flies reverse the polarity of cells anterior to the clone, particularly posteriorly within the A compartment (genotypes 4 and 5, Fig 2D), as they do in wildtype flies (genotypes 6-8, Fig 3A). Also, ft− clones in stan− flies (genotype 9) can reverse the polarity of cells behind the clone, as they do in wildtype flies (Casal et al., 2002). The repolarisation caused by gain, or loss, of Ft in clones in stan− flies can spread a few cell diameters away from the clone.

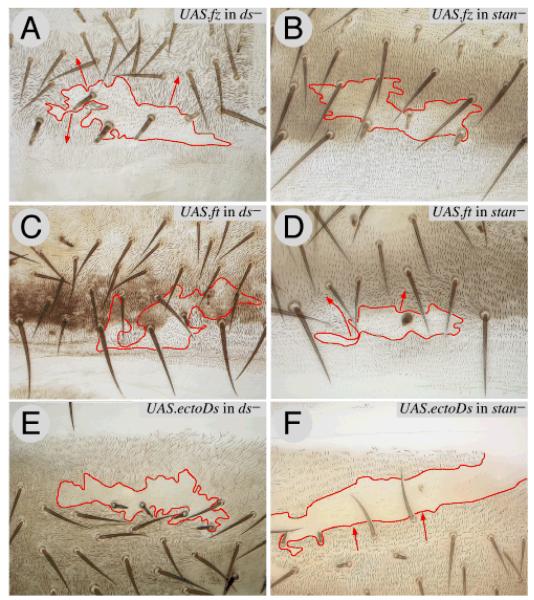

Figure 2. The Ds and Stan systems are different and independent.

This figure compares the effects of driving Fz, Ft and ectoDs (a particularly potent signalling form of Ds) in clones in flies lacking either the Ds or the Stan systems.

Clones overexpressing fz (UAS.fz) reverse the polarity of wildtype cells over a short range (Lawrence et al., 2004) but they reverse polarity of ds− cells over a longer range (2A). UAS.fz clones have no effect in stan− flies (2B).

UAS.ft clones reverse the polarity of wildtype cells in front of the clone (Fig 3A), but have no effect in ds− flies (2C); the same clones reverse polarity of stan− flies (2D)

Clones overexpressing ectoDs reverse the polarity of wildtype cells behind the clone (Fig 3C), but have no effect in ds− flies (2E). These UAS.ectoDs clones reverse polarity of stan− flies (2F). Clones marked with pwn (A-D), and pwn sha (E, F). As in all the figures (except Fig 7), anterior is towards the top, red lines outline the clone and red arrows indicate imposed polarity.

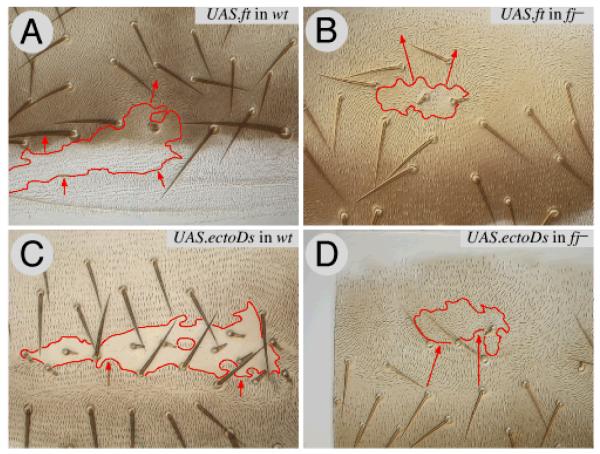

Figure 3. The range of repolarisations due to the Ds system is increased in fj− flies.

This figure compares the effects of UAS.ft clones (reversing polarity in front of the clone in the A compartment) and UAS.ectoDs clones (reversing polarity behind) in wildtype flies (3A, 3C) with the same types of clones in fj− flies. The range in fj− flies is increased (3B, 3D). Clones marked with pwn (A, B, D) and with pwn sha (C).

We find comparable results for Ds: UAS.ds clones have only trace effects in wildtype flies (genotype 10). However, a form of Ds that lacks the cytosolic domain (“ectoDs”) is more potent, so that UAS.ectoDs clones reverse the polarity of wildtype cells behind the clone, with a range of several cells (genotype 11, Fig 3C). We have used ectoDs to test whether repolarisation caused by ectopic Ds activity depends on the Stan system, and find that it does not: in stan− flies, UAS.ectoDs clones reverse cell polarity strongly behind the clone (genotype 12, Fig 2F). UAS.fj clones in stan− flies (genotype 13) also repolarise in front, as they do in wildtype flies. Thus, at least in the A compartment, signals coming from UAS.ft, ft−, UAS.ectoDs and UAS.fj clones are effective and can propagate over several cell diameters through stan− territory. It appears that the Ds system has an intrinsic capacity to repolarise cells, even when the Stan system is incapacitated.

Our conclusion in the abdomen using stan− contrasts with results in the eye, using fz− (Yang et al., 2002). We therefore repeated the UAS.ft, ft− and UAS.ectoDs experiments described above in a fz− background (genotypes 14-17) and find that the hairs in front (UAS.ft) or behind (ft−, UAS.ectoDs) clones are disturbed and/or reversed. For UAS.ft clones in fz− flies, we find that hairs in front are disturbed or reversed, although the effects are less consistent than in stan− flies. For ft− and UAS.ectoDs clones in fz− flies, hairs behind are reversed, as observed in stan− flies. We then made the UAS.ft and UAS.ectoDs clones in stan− fz− flies (genotypes 18 and 19) and, again, the clones repolarise nearby hairs — the UAS.ectoDs clones have the strongest effects, reorienting the hairs around the clone over a long range (Figure 1, Supplemental Data). These results show that the Ds system can initiate and propagate PCP, even in the absence of both key components of the Stan system; suggesting that the Ds system can confer and propagate without the participation of the Stan system.

In the absence of the Ds system, cells are more responsive to the Stan system

If the two systems are independent but set up to act against each other by an experiment, one system might have more effect if the other were inactivated. Indeed, in ds− wings, fz− clones repolarise surrounding cells over a longer range than they do in wildtype wings (Adler et al., 1998). Similarly, an ectopic gradient of Fz expression repolarises cells over an increased range when Ft is absent (Ma et al., 2003). In agreement, we find that in the abdomen, repolarisations induced by fz−, UAS.fz or UAS.stan clones show a longer range in ds− (genotypes 20-23), or even when UAS.fz clones are made in ft− (genotype 24), than they do in wildtype flies (Fig 2A). Also, if UAS.fz is driven in the entire P compartment (genotype 25) reversal at the back of the A compartment is greater in ds- than in wildtype flies. Finally, a weak disparity in Fz activity that does not repolarise cells in wildtype flies is sufficient to repolarise cells over several cell diameters in ds− flies (genotype 26, Fig 4A). This same disparity can even induce a little repolarisation in ds−/ds+ flies (Fig 4B).

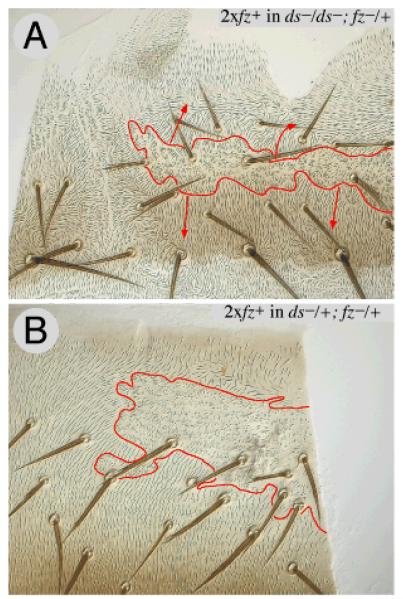

Figure 4. Cells respond more to the Stan system in the absence of the Ds system.

A twofold increase in the dose of the fz gene (between clone and surround) has no effect in wildtype flies (not shown) but, in ds− flies, reverses polarity in front of the clone and imposes normal polarity behind the clone (4A). Compare with the small effect, indicated by a yellow arrowhead, of similar clones in a ds+/ds− fly (4B). Clones marked with trc.

Conflicts between the Ds and Stan systems can affect the sign or range of repolarisation

Normally, UAS.ft clones in the A compartment reverse the polarity of cells in front of the clone and do so most strongly when located at the rear of the compartment, where endogenous Ft is least active. Conversely, fz− clones reverse the polarity of cells behind the clones, wherever they arise (Lawrence et al., 2004). Thus, in the A compartment, clones of fz− UAS.ft cells (genotype 27) will create opposing disparities in the Ds and Stan systems and send conflicting outputs to the adjacent, wildtype cells. We find that, at the front of the A compartment, they reverse posteriorly, behaving like fz− clones. While, at the back of the A compartment, fz− UAS.ft clones reverse anteriorly; as do UAS.ft clones. This may be simply understood: for the Stan system, repolarisation is driven by the difference in Fz activity across the clone/background interface, which appears to be of similar strength all along the A/P axis (Fig 1). For the Ds system, the strength of the disparity in Ft activity between UAS.ft clones and the surround depends on position, being least at the front and greatest at the back of the A compartment (Fig 1). Thus, in the anterior region, the repolarisation due to Fz overcomes the weaker opposing influence of UAS.ft. At the rear of the A compartment, the effect due to the Ds system is the stronger.

UAS.fz clones in wild type flies reverse the Stan system output in front of the clone, creating a conflict with the Ds system: this conflict appears to reduce the range of repolarisation caused by such clones, as the range increases in ds− flies. In fz− flies, UAS.fz clones change the polarity of only the adjacent cells (Lawrence et al., 2004). If UAS.fz clones in ds− flies were utilising only the Stan system to drive long range repolarisation, then UAS.fz clones in ds− fz− flies should behave exactly as they do in fz− flies, and they do; only one cell is repolarised (genotype 28). The Ds system is inactivated, but the Stan system functions just as it normally does in fz− flies.

Disparities in the Ds system do not bias the Stan system

The experiments above show that the Ds system can polarise cells independently of the Stan system. However, the Stan system might still be biased by the Ds system. To assess whether there is normally any input from the Ds system into the Stan system, we generated clones expressing UAS.ectoDs, UAS.ds or UAS.ft in ds− flies (genotypes 29-34) and also clones expressing UAS.ectoDs or UAS.ft in ft− flies (genotypes 35-36) and asked whether such clones repolarise surrounding mutant cells. Normally, UAS.ectoDs and UAS.ft clones strongly repolarise surrounding wildtype cells (Fig 3 A,C), indicating that they cause sharp disparities in activity of the Ds system. Moreover, the responding mutant cells are particularly sensitive to small disparities in activity of the Stan system (Fig 4A); hence if these two types of clones were to bias the Stan system, either within the clone or across the border, we would expect them to repolarise the surround, in either ds− or in ft− animals. Nevertheless, they do not, not even changing the polarity of one cell in either ds− (Fig 2C, E) or in ft− flies. We know that UAS.ds, UAS.ectoDs and UAS.ft are effective constructs even in the absence of endogenous Ds and Ft — when these constructs are expressed in ds− ft− clones, they repolarise surrounding wildtype cells (see below). As positive controls we added UAS.fz separately to both UAS.ft and UAS.ds clones in ds− flies (genotypes 37 and 38) and then the long-range repolarisation normally induced by UAS.fz clones in ds− flies (cf Fig 2A) was seen. Likewise, when UAS.fz was added to clones expressing either UAS.ft or UAS.ectoDs in ft− flies these clones again caused long-range repolarisation (genotypes, 39 and 40). Thus, the failure of UAS.ds, UAS.ectoDs, and UAS.ft clones to repolarise surrounding cells in ds− or ft− animals argues that the Stan system is not biased by the Ds system.

Cell polarity in the absence of both the Ds and Stan systems

If the Ds and Stan systems give independent inputs into PCP, the loss of either system might compromise polarity, but the loss of both systems should cause more damage. This is so; stan− flies have almost normal hair polarities in the tergite, apart from near the front and near the rear (genotype 41), and in ds− tergites, hair polarities are normal apart from whorls in the middle (genotype 42). The phenotype of ds− stan− flies is more extreme than in either ds− or stan− and hair and bristle polarity is randomised throughout the tergite (genotype 43, Fig 5B). Similar results are observed for the ventral dentical pattern of the third instar larva: the double mutant condition is more severe than in either single mutant (Fig 5).

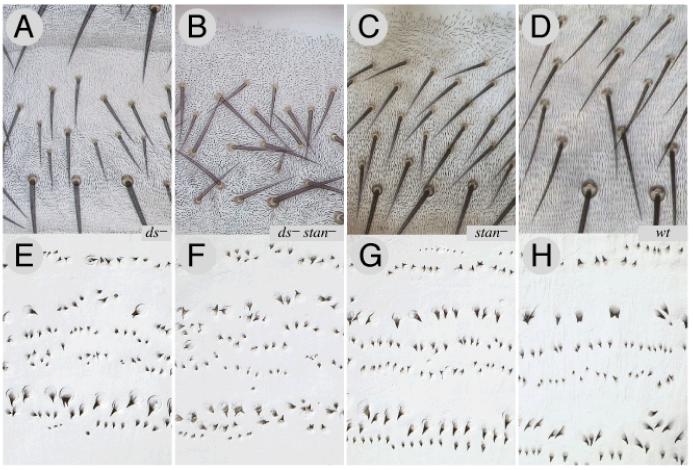

Figure 5. The loss of one or both systems leads to different larval and adult phenotypes.

ds− tergites have a whorly central area but the bristle pattern is near normal (5A) while stan− tergites are dishevelled at the front and back in the A compartment, but near normal elsewhere (5C). In ds− stan− tergites both the hairs and bristles are dishevelled everywhere (5B). In the 3rd instar larvae, ds− have disturbed hairs in the anterior rows of the ventral denticles, but the most posterior rows 5 and 6 are normal (5E). The stan− larval denticle pattern (5G), as far as we can see (compare Price et al., 2006) is like wildtype (5H), while the ds− stan− larvae (5F) show randomised polarity. Note, for 5A-D, adult cuticles were mounted without squashing, in order to preserve bristle orientation in its native state.

Polarisation depends on the balance of Ds and Ft activity in signal-sending cells

We now ask how the Ds system, acting on its own, can affect PCP. The Ds system has three components and all appear to be graded in activity (Fig 1). Either ds− or ft− clones can initiate polarity changes that spread into wildtype territory (Casal et al., 2002), but clones that lack both ds and ft do not cause repolarisations (genotype 44). Adding back either UAS.ds or UAS.ft to ds− ft− clones restores their ability to repolarise, with UAS.ds reversing polarity behind the clone and UAS.ft in front (genotypes 45 and 46). These results suggest that an imbalance (from the normal ratio) of Ds and Ft proteins in the “sending” cells changes polarity in the wildtype “receiving” cells that then spreads further. Note particularly that the sending cell does not need both Ds and Ft in order to repolarise nearby wildtype cells, the presence of either protein alone will do so.

Ds and Ft are both needed in the receiving cell

ds− or ft− clones both cause polarity changes in neighbouring wildtype cells. However, inside regions of such clones, the hairs are oriented in whorls, resembling small portions of entire ds− or ft− flies (unpublished and Casal et al., 2002), suggesting that the polarity outside the clone cannot propagate into territory lacking either Ds or Ft. Other experiments confirm this: as we have seen, UAS.ds, UAS.ectoDs and UAS.ft clones in ds− flies all fail to repolarise, not even changing the polarity of those ds− cells adjacent to the clone (Fig 2C,E). Moreover, UAS.ectoDs and UAS.ft clones in ft− flies also fail to repolarise any ft− cells outside the clone. Together, these experiments show that cells need both Ds and Ft in order to receive and respond to a polarity signal initiated by the Ds system, even when that signal comes from immediate neighbours.

The ectodomains, not the endodomains, of Ft and Ds determine the sign of polarity

As described above, UAS.ectoDs clones repolarise surrounding cells like UAS.ds clones (reversing behind), only more potently (Fig 2F, 3C). The same is true for UAS.ectoDs clones that are also ds−, ft− or ds− ft− and therefore lack one or both the endogenous proteins (genotypes 47-49) — presenting the Ds ectodomain on the surface of the sending cell is alone sufficient to change the polarity of the receiving cells. However, the Ft ectodomain cannot act alone: while UAS.ectoFt clones (genotype 50) behave similarly to UAS.ft and ft− UAS.ft clones (genotype 51), ft− UAS.ectoFt and ds− ft− UAS.ectoFt clones (genotypes 52 and 53) behave, respectively, like ft− or ds− ft− clones. Thus, the capacity of ectoFt to repolarise nearby cells also requires endogenous Ft in the sending cell, supporting suggestions that Ft may form cis-homodimers (Matakatsu and Blair, 2006).

Can the cytosolic domains influence the sign of the signal? We swapped them to make two chimaeric molecules, ectoDs::endoFt and ectoFt::endoDs and found the answer to be no. Clones expressing these proteins behaved as if they expressed the native protein with the same ectodomain, reversing hairs behind strongly (ectoDs::endoFt, genotypes 54-57) or in front (ectoFt::endoDs, genotypes 58-61), either when expressed in cells that were otherwise wildtype or were ds−, ft−, or ds− ft−. Note that the Ds and Ft endodomains are not always interchangeable: the endodomain of Ft cannot substitute for that of Ds in limiting the potency of the signal (UAS.ectoDs and UAS.ectoDs::endoFt clones repolarise strongly, whereas UAS.ds clones repolarise weakly). However, the endodomain of Ds can substitute for the endodomain of Ft to allow the ectoFt protein to signal in the absence of endogenous Ft: ds− ft− UAS.ectoFt clones do not reverse the polarity of cells in front of the clone, but ds− ft− UAS.ectoFt::endoDs clones do. We also made deleted forms of Ds and Ft (UAS.endoDs and UAS.endoFt), in which the ectodomain of each protein is replaced by three HA1 tags. If endoDs or endoFt are expressed in wildtype cells (genotypes 62 and 63) we see no alteration in polarity — however, note that some rescue of polarity was reported when endoFt was expressed in a ft− mutant background (Matakatsu and Blair, 2006). The key finding from this group of experiments is that the ectodomains of Ds and Ft are essential for sending the polarising information.

Fj modulates the range of propagation due to the Ds system by acting through Ft

Fj acts in a graded fashion and appears to repress Ds and promote Ft activity (Zeidler et al., 1999; Casal et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2002). We have evidence that Fj must work through Ds and/or Ft: ds− fj− flies (genotype 64) resemble ds− flies and UAS.fj clones have no effect on polarity in ds− flies (genotype 65). Normally UAS.fj clones in the tergite repolarise wildtype cells in front (Casal et al., 2002), but UAS.fj clones that are also ft− or ds− ft− do not (genotypes 66 and 67). However, in contrast to ft− UAS.fj clones, ds− UAS.fj clones repolarise strongly in front (genotype 68), apparently more strongly than clones that are simply ds−. These last two experiments suggest that in order to produce polarity changes in the surrounding wildtype cells, Fj acts not on Ds but on Ft. In support, UAS.fj UAS.ds (genotype 69), and UAS.fj UAS.ectoDs clones (genotype 70) behave like UAS.fj clones and reverse the polarity of cells in front. Further, UAS.fj clones behave like UAS.ft clones, and also like UAS.ft UAS.ds and UAS.ft UAS.ectoDs clones (genotypes 71 and 72), again arguing for action of Fj on Ft.

To gain more insight into Fj, we made UAS.ft, and UAS.ectoDs clones in fj− flies (genotype 73 and 74). The lack of Fj enhances the effects of both proteins: repolarisations can spread further than in any other situation we have seen, with a range of up to about 10 cells (Fig 3B,D). By contrast, the action of UAS.ds clones is not enhanced in fj− flies (genotype 75).

Dual control of the Ds and Stan systems by Hedgehog

According to the linear model of PCP, morphogens such as Hh in the abdomen, or Wg in the eye, control polarity by establishing gradients of the Ds system, which then bias the Stan system. But, if the Ds and Stan systems are independent, we must now ask does Hh signalling bias both systems, or only one? To answer this question we use clones of patched− (ptc−) cells in which the Hh transduction pathway is constitutively activated in all cells within the clone. Unfortunately, ptc− clones cause complex effects by ectopically inducing engrailed (en) and that leads to a Hh-secreting P compartment forming near the front of the A compartment (Struhl et al., 1997b; Lawrence et al., 1999)! We avoid these problems by using either ptc− en− clones or ptc− hh− clones (Lawrence et al., 1999; Lawrence et al., 2002). Such clones reverse the polarity of wildtype cells behind the clone, allowing us to test whether activation of the Hh transduction pathway can polarise cells via either, or both, the Stan and Ds systems.

ptc− en− clones cause reversal of polarity behind in stan− (genotype 76, Fig 6C), fz− (genotype 77), and ds− flies (genotype 78, Fig 6A). However, ptc− en− clones do not reverse polarity in ds− stan− flies (genotype 79, Fig 6B). It follows that Hh signalling polarises cells in the tergite largely or only via the Stan and Ds systems, and that it does so by means of two distinct inputs into PCP. For the Ds system it seems that Hh governs cell polarity, at least in part, by driving the graded expression of the transcription factor Omb, which, probably, controls transcription of ds (Lawrence et al., 2002).

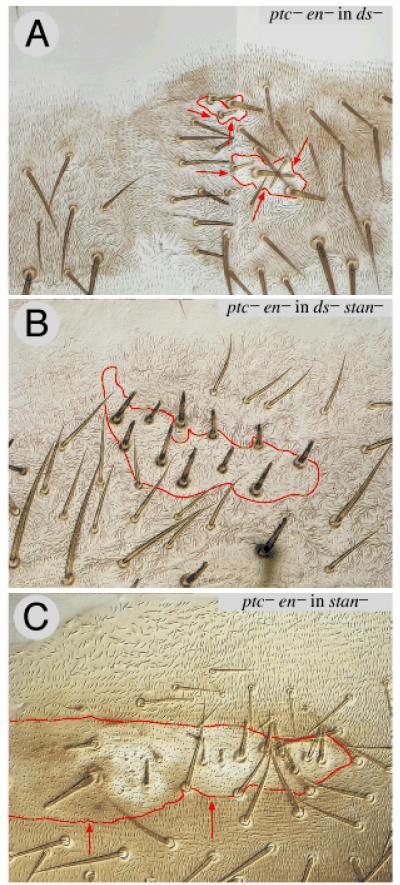

Figure 6. ptc− en− clones in flies lacking one or both systems.

The Hh signal transduction pathway is maximally and constitutively activated in ptc− en− clones. Such clones reverse the polarity of hairs behind the clone both in ds− flies (6A) and in stan− flies (6C). However in ds− stan− flies, the ptc− en− have no discernable (consistent) effect on the surround (6B) — compare with 6A where there is a consistent effect, the hairs pointing inwards all around the clone. Clones marked with pwn. The shadowed section in 6A indicates that the image was reconstructed like Humpty Dumpty from a single bisected piece of cuticle.

For the Stan system, Hh presumably biases the activity of Fz (Lawrence et al., 2004) but it is not clear how it does so. It did not escape anyone’s notice that Fz is a Wnt receptor and therefore many suggested that Wg or some other Wnt might be an intermediary. Several experiments argued against this possibility (Wehrli and Tomlinson, 1998; Lawrence et al., 2002), but they were all done in wildtype flies, where an active Ds system might have blocked any effect. Therefore, we made clones of cells that express UAS.wg, UAS.Nrt::wg (a membrane-tethered form of Wg), UAS.fz2DN (a membrane-tethered form of the Wg-binding domain of Fz2 to manipulate the distribution of Wg), all the other Drosophila Wnts (UAS.Wnt2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 10) and all in ds− flies, but they induced no repolarisation (genotypes 80-91). These results appear to rule out all known Wnt genes, notably Wg itself, as polarising factors for the Stan system.

DISCUSSION

Many epithelia exhibit planar cell polarity (PCP), but examples from Drosophila have been studied in most depth (reviewed in Klein and Mlodzik, 2005). It was proposed long ago (Lawrence, 1966; Stumpf, 1966) that the vectors of a pervasive gradient orient PCP and here we examine how this is achieved. In the current and prevailing model, a morphogen gradient (for example, Hh or Wg) organises the expression of fj and ds to set up Ds system gradients (Casal et al., 2002; Simon, 2004). Then, small differences in Ds system activity from one cell to the next are thought to feed into Fz and bias the Stan system. The Stan system then acts more directly on the cell to orient structures, such as ommatidia or hairs (Yang et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2003). Here we test this model and find our results do not support the main part of it; instead they argue that the Hh gradient acts separately on the Ds and Stan systems to generate two independent inputs into PCP.

The Ds system can polarise cells independently of the Stan system

The case for the Ds system polarising cells via the Stan system rested on epistasis experiments in the eye: disparities in the Ds system, such as clones of ds− or ft− cells, repolarise cells in wildtype flies, but not in fz− flies. This requirement for Fz suggested that the Ds system might act via Fz (Yang et al., 2002). However, we find that, in the dorsal abdomen, the Ds system can polarise cells without the Stan system. We present several lines of evidence, but the most crucial is that clones of UAS.ft or UAS.ectoDs cells, both of which repolarise surrounding wildtype cells up to several cell rows away, also do so in flies that lack either stan, fz, or both. It follows that the Ds system, acting alone and using Ds and Ft, can drive changes in the polarity of surrounding cells. This conclusion raises new questions: how does the Ds system produce and propagate polarising information? What polarises the Stan system? How do cells integrate the two separate inputs from the Ds and Stan systems?

How does the Ds system produce and propagate polarising information?

The discovery that fz− clones can change the polarity of nearby wildtype cells was important (Gubb and Garcia-Bellido, 1982; Vinson and Adler, 1987) and many attempts have been made to explain it: most models invoke feedback to amplify initial biases in Fz activity, within or between cells. However, now we have shown that clones affecting the Ds system can alone change the polarity of nearby wildtype cells we need to know how they might do so. The following matters are relevant:

First, morphogen gradients (Hh in A, Wg in P: Lawrence et al., 2002) appear to polarise the Ds system by grading the amount and/or state of activity of three components of the system, Ds, Ft and Fj (Casal et al., 2002).

Second, we find that cells can “send” information by presenting either Ds or Ft to “receiving” neighbours. This signal seems to depend on the ratio of Ds to Ft in the sending cell (hairs made by the receiving cell point towards neighbours with a higher Ds/Ft ratio). It is not clear how the ratio is encoded and transmitted but the signal could depend on molecular interactions in the sending cell. For example, the Ds/Ft ratio in the sending cell could determine whether how much Ds or Ft it presents to neighbours (Fig 7).

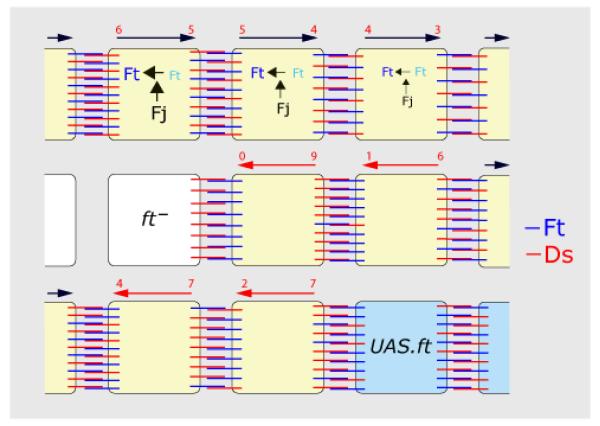

Figure 7. A speculative model of the Ds system.

The figure shows the A compartment, anterior is to the left. Ft is indicated in blue and Ds in red. The long arrows show the polarity of each cell, normal in black and reversed in red. In the wildtype (see top), there is evidence for opposing gradients of Fj protein (Fj) and of Ds (Ds) (Casal et al., 2002) as indicated by the size of the letters. Although there is no gradient of Ft protein (Ft) we envisage a gradient of Ft activity (Ft), driven by the action of Fj on Ft, as argued in the results. Active Ft can become stabilised in the membrane of one cell so that it can form heterodimers with Ds in the next cell (provided that sufficient Ds is present in that cell) .

The polarity of any cell might depend on a comparison between the number of heterodimeric Ds molecules (red numbers above the cells) on the anterior and posterior faces of the cell, with the polarity of that cell pointing downwards. Note that even though the Ds gradient peaks posteriorly, there are more Ds heterodimers anteriorly. Thus the graded form of Ds and Fj expression might not be crucial, so long as one is graded it is sufficient — both uniform Fj and uniform Ds can rescue fj− and ds− eyes, respectively (Simon, 2004).

The middle row shows the effect of a ft− cell, in which all available Ds will make heterodimers with Ft on the facing (anterior) membrane of the cell on its right. Consequently, in this wildtype cell, Ds will be displaced towards the opposite (posterior) face of this wildtype cell, whose polarity will therefore become reversed. This excess of Ds molecules will bind to Ft in the nextmost cell, and again, by depleting Ds from its anterior face, will repolarise it. This effect will weaken from cell to cell.

The lower row shows a UAS.ft cell that will attract more Ds to the facing membrane (posterior) of its neighbour on its left, thereby polarising that cell, the effect spreading anteriorwards.

Third, in order to respond by a change in polarity, we have some evidence that the receiving cells need both Ds and Ft. There is evidence that Ds and Ft can form trans-heterodimers between cells in culture (Matakatsu and Blair, 2004), suggesting how an imbalance in the ratio of Ds/Ft in the sending cell might affect the receiving cell. Also, note that Ds-Ft bridges accumulating across one cell interface probably alter the amounts or distribution of these bridges along other interfaces of the same cell — it has been reported that Ds or Ft proteins become concentrated along cell interfaces in which the abutting cell presents only Ft, or Ds, respectively (Strutt and Strutt, 2002; Ma et al., 2003). For example, in UAS.ft clones, the more Ft in the sending cell, the greater amount of Ds would be drawn to the facing membrane of the receiving cell and this would leave less Ds and more free Ft on the opposite face of the receiving cell. It is this kind of asymmetry that may be propagated through the trans-heterodimers to the next cell and beyond (Fig 7).

Fourth, we ask how the amplitude of the signal is determined. The range depends on where (in the compartment) the clones are made, pointing to the importance of any discrepancy between Ft and Ds levels in the clone and the levels in the surrounding cells. The range of repolarisation also depends on Fj which appears to act to Ft, perhaps by promoting the formation of heterodimers. Thus, with UAS.ft clones in a fj− background where heterodimers are sparse because the activity of Ft is low, there will be a large discrepancy across the clone border and a long-range effect. The same clones in a wildtype background will have a smaller discrepancy and a shorter range (Fig 7). Note also that excess ectoDs sends a much stronger signal than excess Ds, suggesting that the cytosolic domain may have an inhibitory function.

How do cells integrate the two separate inputs from the Ds and Stan systems?

The A compartments of the dorsal abdomen might seem exceptional, for here the Ds system can polarise cells in the absence of the Stan system — yet, neither in the P compartment of the abdomen, nor in the pleura, nor in the wing do UAS.ft or UAS.ectoDs clones appear to polarise cells lacking the Stan system. Nevertheless, the positive result in the tergite tells us that the Ds system has an inherent capacity to confer and propagate PCP. We rate this positive result as decisive and note that the apparent failure of the Ds system to act independently in other parts of the fly may have a simpler explanation. For example, if cells normally integrate separate inputs from the Ds and Stan systems, it could be that the lack of one system might interfere with the response to the other system. Also it seems that organs differ in their dependency on the two systems: for instance, in both fz− and stan− flies, the hair polarities are near normal in the tergite, but are randomised in the ventral pleura. Hence, polarity of the tergite appears to depend mainly on the Ds system, whereas the pleura depends mostly on the Stan system. In the eye, polarity is randomised in the absence of either system (Wehrli and Tomlinson, 1998; Yang et al., 2002) and therefore the eye might depend to a similar extent on both.

In addition, it is significant that there are qualitative differences in the outputs of the two systems; the Ds system being involved in growth, cell shape, and cell affinity (Bryant et al., 1988; Adler et al., 1998; Matakatsu and Blair, 2006), whereas the Stan system is not. This suggests that cell polarity is a composite property (like height in humans!), the orientation of hairs being the deceptively simple outcome of diverse inputs. For example, the Ds system might affect cell shape and tiling, and, in the absence of the Stan system, that could suffice to orient hairs in some tissues. While the Stan system may place asymmetric structures, such as actin filaments, and these may orient hairs in some places, even when the Ds system is disabled. Thus, both ds− and fz− eyes have many disoriented ommatidia (Zheng et al., 1995; Yang et al., 2002), perhaps because their polarity depends on both systems. If so, it could become problematic to detect effects of clones that lack one system (eg ft−), in eyes that lack the other system (eg fz−, see (Yang et al., 2002)). Also, even though in the wildtype both systems would operate in concord, some experiments would create conflicts between them, with outcomes varying in different tissues. For these reasons it can look as if PCP mechanisms vary fundamentally from organ to organ, say from wing to eye (Simon, 2004), yet they may not. At a minimum, our results show the linear pathway, Ds system -> Stan system is wrong in the tergite and challenge its validity elsewhere.

The behaviour of ptc− en− clones is pertinent because they repolarise surrrounding cells by means of both systems. In wildtype flies, these clones reverse behind in the A compartment. Note that the type of cuticle made by ptc− en− clones corresponds to the back of the A compartment and it is here that we believe the Ds activity should normally peak and Ft activity should be minimal (Casal et al., 2002) — thus it makes sense for ptc− en− clones to resemble UAS.ectoDs or ft− clones. Similarly, as cells in the tergite make hairs that point towards neighbours with lower Fz activity, it makes sense that ptc− en− clones behave like fz− clones: this is because all cells in the A compartment normally point their hairs towards the back of the compartment, where Hh signalling peaks and where our model calls for Fz activity to be minimal (Lawrence et al., 2004).

The ability of ptc− en− clones to repolarise surrounding cells in ds− flies provides a hint as to how Hh signalling might feed into the Stan system: we have made ptc− en− stan− clones in ds− flies (genotype 92) and these clones, unlike ptc− en− clones in ds− flies, fail to repolarise. This result is most simply explained if Hh were to drive the Stan system by acting itself to regulate the level of Fz activity, rather than via the induction of another polarising ligand. If this were so, then Hh would be one component of the elusive Factor X!

Finally, if the two systems are independent we need to address why the Stan system proteins can accumulate asymmetrically as a result of action of the Ds system; for example, ft− clones in the wing contain abnormally polarised cells that also show corresponding changes in the distribution of Dishevelled (Strutt and Strutt, 2002; Ma et al., 2003). We have argued that the asymmetry of the “core” Stan system proteins is a consequence not a cause of polarity (see Introduction and Lawrence et al., 2004). Hence, we suggest that as a consequence of changes in the Ds system, cells may be reoriented, and whatever polarity they adopt will be reflected in both the asymmetric localisation of Stan proteins and in the orientation of the hairs.

Registration of the Ds and Stan gradients

It is intriguing that, in the abdomen, the Ds and Stan system gradients are not congruent — yet another argument that they are independent. The behaviour of fj−, UAS.fj, ds− and ft− clones in the A and P compartments argues that the Ds system consist of two gradients with opposing slopes: the Ds activity peaking at the back of the A compartment and declining forwards, into the A compartment, and backwards, into P (Fig 1 and Casal et al., 2002). By contrast, the Stan system appears to be a monotonic gradient of Fz activity with A and P cells both pointing down the gradient. A nice and still unsolved problem is the registration of a Fz gradient that presumably repeats once per metamere: do its borders coincide with segmental or parasegmental borders? We do not know, but, for the animal, having two gradient systems with different registrations in space may help solve the tricky problem of how cell polarity is maintained across boundaries.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of clones was as reported in Lawrence et al (2004). For genotypes of the 92 experiments described in the text see Supplemental Data.

The stan alleles used were chosen for technical reasons. The amorphic allele stanE59 is lethal homozygous, owing to a requirement for Stan activity in the nervous system. stanE59 mutant flies can be rescued by neural expression of the stan gene (Lu et al., 1999), but doing this was impractical with our complex genotypes and also open to the criticism that unintended, low level expression of the rescuing UAS.stan transgene might alleviate the PCP phenotype in the abdominal epidermis. We therefore chose stan3/ stanE59 which sufficed because this combination, as well as stan3/ stan3, blocked all communication by the Stan system in the abdomen (Lawrence et al., 2004 see Fig 2). Even stan3/ stan3 blocked almost all communication in the wing (Chae et al., 1999). In particular, UAS.fz stan3 and UAS.fz stanE59 clones both fail to repolarise surrounding wildtype cells, showing that both these stan alleles block the sending of polarising information imparted by Fz. UAS.fz stanE59 clones in stan3/ stanE59 flies (Lawrence et al, 2004) are indistinguishable from UAS.stan UAS.fz stanE59 clones in the same flies (genotype 1) indicating that stan3/ stanE59 lack the ability to receive the same polarising information. Finally, we note that all of the results obtained in stan3/ stanE59 flies were confirmed both in fz− and stan3/ stanE59; fz− flies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Simon Bullock, David Strutt and Jean-Paul Vincent for comments on the manuscript, Seth Blair and Bloomington for stocks. David Strutt has been very generous with both advice and stocks. We thank Atsuko Adachi, Kit Bonin and Xiao-Jing Qiu for assistance in New York. Birgitta Haraldsson and the Zoology Department, University of Cambridge have given invaluable support. PAL and JC have been supported by the MRC; GS is an HHMI Investigator.

REFERENCES

- Adler PN. Planar signaling and morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2002;2:525–35. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler PN, Charlton J, Liu J. Mutations in the cadherin superfamily member gene dachsous cause a tissue polarity phenotype by altering frizzled signaling. Development. 1998;125:959–68. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler PN, Krasnow RE, Liu J. Tissue polarity points from cells that have higher Frizzled levels towards cells that have lower Frizzled levels. Curr Biol. 1997;7:940–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amonlirdviman K, Khare NA, Tree DR, Chen WS, Axelrod JD, Tomlin CJ. Mathematical modeling of planar cell polarity to understand domineering nonautonomy. Science. 2005;307:423–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1105471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-López LA, Baonza A, Garcia-Bellido A. The orientation of cell divisions determines the shape of Drosophila organs. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1640–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant PJ, Huettner B, Held LI, Jr., Ryerse J, Szidonya J. Mutations at the fat locus interfere with cell proliferation control and epithelial morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1988;129:541–54. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal J, Struhl G, Lawrence PA. Developmental compartments and planar polarity in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1189–98. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00974-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae J, Kim MJ, Goo JH, Collier S, Gubb D, Charlton J, Adler PN, Park WJ. The Drosophila tissue polarity gene starry night encodes a member of the protocadherin family. Development. 1999;126:5421–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton S. Planar polarization of Drosophila and vertebrate epithelia. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:860–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanto M, McNeill H. Planar polarity from flies to vertebrates. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:527–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebe M. Ups and downs of tissue and planar polarity in plants. Bioessays. 2004;26:719–29. doi: 10.1002/bies.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubb D, Garcia-Bellido A. A genetic analysis of the determination of cuticular polarity during development in Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;68:37–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein TJ, Mlodzik M. Planar cell polarization: an emerging model points in the right direction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:155–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.132806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA. Gradients in the insect segment: The orientation of hairs in the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus. J. Exp. Biol. 1966;44:607–620. doi: 10.1242/jeb.44.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. hedgehog and engrailed: pattern formation and polarity in the Drosophila abdomen. Development. 1999;126:2431–2439. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. Towards a model of the organisation of planar polarity and pattern in the Drosophila abdomen. Development. 2002;129:2749–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. Cell interactions and planar polarity in the abdominal epidermis of Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:4651–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Davies A. Planar cell polarity in the inner ear: how do hair cells acquire their oriented structure? J Neurobiol. 2002;53:190–201. doi: 10.1002/neu.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Usui T, Uemura T, Jan L, Jan YN. Flamingo controls the planar polarity of sensory bristles and asymmetric division of sensory organ precursors in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1247–50. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Yang CH, McNeill H, Simon MA, Axelrod JD. Fidelity in planar cell polarity signalling. Nature. 2003 doi: 10.1038/nature01366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2004 doi: 10.1242/dev.01254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Separating the adhesive and signaling functions of the Fat and Dachsous protocadherins. Development. 2006;133:2315–2324. doi: 10.1242/dev.02401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MH, Roberts DM, McCartney BM, Jezuit E, Peifer M. Cytoskeletal dynamics and cell signaling during planar polarity establishment in the Drosophila embryonic denticle. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:403–15. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saburi S, McNeill H. Organising cells into tissues: new roles for cell adhesion molecules in planar cell polarity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:482–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MA. Planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye is directed by graded Four-jointed and Dachsous expression. Development. 2004;131:6175–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.01550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G, Barbash DA, Lawrence PA. Hedgehog acts by distinct gradient and signal relay mechanisms to organise cell type and cell polarity in the Drosophila abdomen. Development. 1997a;124:2155–2165. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G, Barbash DA, Lawrence PA. Hedgehog organises the pattern and polarity of epidermal cells in the Drosophila abdomen. Development. 1997b;124:2143–2154. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt D. Frizzled signalling and cell polarisation in Drosophila and vertebrates. Development. 2003;130:4501–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt DI. The asymmetric subcellular localisation of components of the planar polarity pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:225–31. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Mundy J, Hofstra K, Strutt D. Cleavage and secretion is not required for Four-jointed function in Drosophila patterning. Development. 2004;131:881–90. doi: 10.1242/dev.00996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Strutt D. Nonautonomous planar polarity patterning in Drosophila: dishevelled-independent functions of frizzled. Dev Cell. 2002;3:851–63. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Strutt D. Long-range coordination of planar polarity in Drosophila. Bioessays. 2005a;27:1218–27. doi: 10.1002/bies.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Strutt D. Planar Cell Polarization during Development. vol. 14. Elsevier; 2005b. Long-range coordination of planar polarity patterning in Drosophila. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf HF. Mechanism by which cells estimate their location within the body. Nature. 1966;212:430–431. doi: 10.1038/212430a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tree DR, Shulman JM, Rousset R, Scott MP, Gubb D, Axelrod JD. Prickle mediates feedback amplification to generate asymmetric planar cell polarity signaling. Cell. 2002;109:371–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura T, Shimada Y. Breaking cellular symmetry along planar axes in Drosophila and vertebrates. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2003;134:625–30. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Shima Y, Shimada Y, Hirano S, Burgess RW, Schwarz TL, Takeichi M, Uemura T. Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, regulates planar cell polarity under the control of Frizzled. Cell. 1999;98:585–95. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson CR, Adler PN. Directional non-cell autonomy and the transmission of polarity information by the frizzled gene of Drosophila. Nature. 1987;329:549–51. doi: 10.1038/329549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford JB, Fraser SE, Harland RM. Convergent extension: the molecular control of polarized cell movement during embryonic development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:695–706. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrli M, Tomlinson A. Independent regulation of anterior/posterior and equatorial/polar polarity in the Drosophila eye; evidence for the involvement of Wnt signaling in the equatorial/polar axis. Development. 1998;125:1421–32. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz A, Nusse R. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling in development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:59–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Axelrod JD, Simon MA. Regulation of Frizzled by Fat-like cadherins during planar polarity signaling in the Drosophila compound eye. Cell. 2002;108:675–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler MP, Perrimon N, Strutt DI. The four-jointed gene is required in the Drosophila eye for ommatidial polarity specification. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1363–72. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Zhang J, Carthew RW. frizzled regulates mirror-symmetric pattern formation in the Drosophila eye. Development. 1995;121:3045–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.