Abstract

In an effort to determine the physiological role of A. thaliana Glx2-1, we attempted to uncover a substrate for the enzyme. Glx2-1 did not effectively process 192 diverse substrates found in a commercial screen used for microorganism identification, or exhibit arylsulfatase, lactonase or phosphotriesterase activities. However, Glx2-1 does exhibit β-lactamase activity with kcat/KM values from 103 to 105 M−1 s−1. Glx2-1 can hydrolyze cephalosporins and carbapenems, albeit with rate constants slower than most metallo-β-lactamases. The potential role of a β-lactamase in the mitochondria of plant cells is briefly discussed.

Enzymes containing the β-lactamase fold are members of a large superfamily of proteins that catalyze a wide variety of enzymatic reactions. The β-lactamase fold consists of an αβ/βα sandwich motif, made up of a core unit of two β-sheets surrounded by solvent-exposed α-helices (1). Members of this superfamily contain a conserved HXHXD motif that has been shown to bind Zn(II), Fe, and Mn. There are several enzymes in the β-lactamase fold family, including metallo-β-lactamases, glyoxalase 2, lactonase, rubredoxin:oxygen oxidoreductase (ROO), arylsulfatase, phosphodiesterase, carboxylesterase (2) and tRNA maturase (3). The prototypical and best-studied members of the β-lactamase fold superfamily are the metallo-β-lactamases (4), which are produced by some bacteria and are responsible for bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics.

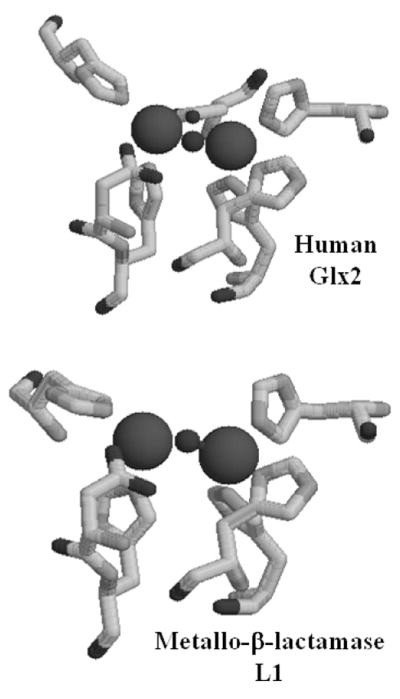

Glyoxalase 2, Glx2, is the second enzyme in the ubiquitous glyoxalase system, which detoxifies 2-oxoaldehydes from cells. Glx2 hydrolyzes the thioester bond of S-D lactoylglutathione (SLG), which is a product of the glyoxalase 1 (Glx1)-catalyzed isomerization of the thiohemiacetal produced spontaneously from the reaction of glutathione and methylglyoxal. Glyoxalase 2 has been biochemically-characterized from many different sources, including plants, mammals, and bacteria, (5–9). A crystal structure of human glyoxalase 2 revealed a tertiary structure that was similar to that previously reported in the metallo-β-lactamases; however, there were some distinct differences in the metal binding site (10). The crystallographers concluded that human Glx2 contains a dinuclear Zn(II) site; however, this conclusion has been recently questioned (11) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Active site structures of (top) human Glx2 and (bottom) metallo-β-lactamase L1. The figures were drawn using Raswin v. 2.7.3 and the coordinate files 1QH5 (for Glx2) and 1SMl (for L1).

Sequence similarity searches of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome/proteome identified five putative proteins that had the invariant HXHXD motif that were predicted to be Glx2 isozymes (Glx2-1, Glx2-2, Glx2-3, Glx2-4, and Glx2-5) (12) (Table S1). The presence of potential N-terminal targeting sequences suggested that Glx2-1, Glx2-4, and Glx2-5 are mitochondrial enzymes. In addition, the analysis of Glx2-1-YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) fusion proteins indicates that Glx2-1 is localized in the mitochondria (unpublished results). Subsequent biochemical studies confirmed that Glx2-2 and Glx2-5 catalyze the hydrolysis of SLG (5, 13), and crystallographic and spectroscopic studies revealed that Glx2-5 contains an FeZn center (5). Glx2-3 was shown to bind a single Fe ion, but this protein did not hydrolyze SLG (14). Subsequent studies have suggested that Glx2-3 is in fact ETHE-1 (ethylmalonic encephalopathy protein 1) (15), and recent studies demonstrate that ETHE-1 is a mitochondrial sulfur dioxygenase (16). We have recently reported that Glx2-1 contains a dinuclear metal center; however, Glx2-1 does not exhibit glyoxalase 2 activity (17). The work presented herein describes our efforts to identify a substrate for Glx2-1.

A. thaliana glx2-1 was cloned into pET26b, and the resulting plasmid pGlx2-1/pET26b was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells (17). Glx2-1 was over-expressed in LB medium supplemented with 250 μM Fe(II) and Zn(II). The resulting, purified protein was > 95% homogeneous (Figure S1) and was shown to bind 0.5 ± 0.3 eq. of Zn(II) and 1.4 ± 0.6 eq. of Fe. Consistent with previous results (17), it exhibited no glyoxalase 2 activity.

In an attempt to identify a Glx2-1 substrate, the purified enzyme was used in Merlin Micronaut TAXA PROFILE E assay plates, which allow for the rapid screening of 192 different substrates and several different reaction types. Analyses of the resulting assays revealed a large number of positive reactions. Therefore, we transformed E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells with an empty pET26b plasmid, performed the purification protocol and pooled and concentrated the fractions in which Glx2-1 would have eluted from the column. When this protein mixture (prep minus Glx2-1) was used in the Merlin assays plates, we found that nine reactions were uniquely catalyzed by purified Glx2-1. All of the potential substrates were nitrophenyl-substituted sugars: p-nitrophenyl α-L-arabinopyranoside, o-nitrophenyl-α-D-galactopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-D-lactopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl β-D-fucopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl α-L-arabinofuranoside, p-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside, o-nitrophenyl β-D-galactoside, and p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl β-D-glucosaminide. However, when we attempted to confirm these substrates using a steady-state kinetic assay as a secondary screen, none of the substrates were hydrolyzed by purified Glx2-1. This seemingly contradictory result can be explained by the different reaction conditions of the Merlin reactions and the steady state kinetic reactions. The Merlin kit reactions were conducted for 24 hours at 37 °C, while the steady state kinetic studies were conducted for 1–2 hours at 25 °C. If Glx2-1 does in fact exhibit nitrophenyl-substituted sugar hydrolase activity, the rates are very slow.

Therefore, we tested whether Glx2-1 could hydrolyze substrates of other β-lactamase fold enzymes. The Merlin kit contained sulfatase substrates, so Glx2-1 does not exhibit arylsulfatase activity. We then tested whether Glx2-1 could hydrolyze p-nitrophenyl-bis-phosphate and p-nitrophenyl-tris-phosphate, which are substrates of zinc phosphodiesterase (ZiPD); however, neither compound was hydrolyzed by Glx2-1. We also tested whether Glx2-1 could hydrolyze lactones, such as γ-butyrolactone and a series of N-acyl-L-homoserine lactones (AHLs) that are commonly found in the rhizosphere, all of which are substrates for the related quorum-quenching AHL lactonases (18). However, Glx2-1 did not hydrolyze any of these compounds.

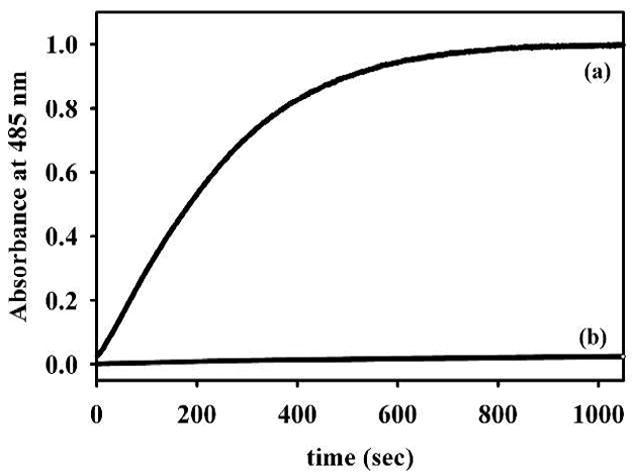

Although only having 10% overall sequence identity (Table S1), Glx2-1, like other Glx2 enzymes, most closely resembles metallo-β-lactamase L1 from S. maltophilia in terms of metal binding ligands (19), except for the presence of an additional Asp in Glx2-1 (Figure 1). Therefore, we tested whether Glx2-1 could catalyze the hydrolysis of the amide bond in several β-lactam containing antibiotics. Surprisingly Glx2-1 exhibited a kcat of 1.20 ± 0.04 s−1 and a Km of 9.9 ± 1.6 μM (kcat/KM = 1.2 × 105 M−1s−1) when using nitrocefin as the substrate. To test whether the observed hydrolysis was due to a constitutively-expressed β-lactamase in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, we assayed the prep minus Glx2-1 protein mixture for β-lactamase activity. The prep minus Glx2-1 sample exhibited essentially no hydrolysis activity against nitrocefin (Figure 2). As an additional control, purified point mutants (R172H; R172H/N174Y; R172H/N174Y/Q249R/R252K) of Glx2-1 were also shown to be incapable of hydrolyzing nitrocefin at appreciable rates (R172H exhibited a kcat value of 0.0023 s−1 and the other mutants exhibited kcat values ≤0.0005 s−1). Lastly, column fractions for wild-type Glx2-1 and the R172H/N174Y mutant were assayed, and activity tracked with the presence of wild-type Glx2-1 (Figure S2). Glx2-1 was also used in assays to ascertain whether the enzyme could hydrolyze cefotaxime or imipenem. The enzyme exhibited steady-state kinetic constants of kcat = 0.20 ± 0.01 and 0.20 ± 0.01 s−1 and Km = 25 ± 5 and 23 ± 3 μM when using cefotaxime (kcat/KM = 8.0 × 103 M−1s−1) and imipenem (kcat/KM = 8.7 × 103 M−1s−1), respectively. The steady-state kinetic constants exhibited by Glx2-1 are significantly lower (10–100 times lower kcat/Km values) than those typically exhibited by most purified metallo-β-lactamases (20), suggesting that β-lactams may not be the natural substrate of the enzyme. It is however interesting to note that Glx2-1 does exhibit higher kcat/Km values than the mononuclear Zn(II) containing A2 enzyme from A. hydrophila (20). In addition, Glx2-1 is >40-fold more active than the evolved metallo-β-lactamase, which was prepared by combining the scaffold of human Glx2 with loops and other structural components of metallo-β-lactamase IMP-1 (21). It is interesting that this in vitro evolution may have occurred in nature with Glx2-1.

Figure 2.

Nitrocefin hydrolysis by (a) Glx2-1 and by (b) prep minus Glx2-1. The concentration of nitrocefin was 96 μM, and the buffer was 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.2. Hydrolyzed product formation was monitored at 485 nm.

To further probe the reaction of Glx2-1 with the β-lactam containing antibiotics, stopped-flow kinetic studies were conducted. Previous kinetic studies revealed that most of the metallo-β-lactamases, which contain a dinuclear metal center, form a reaction intermediate, which absorbs at 665 nm, during the hydrolysis of nitrocefin, while the mononuclear Zn(II) containing analogs and metallo-β-lactamase BcII (dinuclear Zn(II)) do not (4). The reaction of 15.5 μM Glx2-1 with 94 μM nitrocefin resulted in stopped-flow progress curves in which the substrate was depleted in 20 sec (Figure S3). There was no build up of species at 665 nm, as is seen with some metallo-β-lactamases. This result indicates that the active site of Glx2-1 is not conducive to stabilizing the ring-opened, nitrogen anionic intermediate of nitrocefin, suggesting that Glx2-1 has an active site more similar to that of BcII.

It is not clear why there should be β-lactamase activity in plant mitochondria. To our knowledge plants do not produce β-lactams, and β-lactams are not present in plant mitochondria. The plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora as well as Serratia and Photorhabdus species do produce carbapenem β-lactams (22), but these compounds presumably target competing bacteria. A recent bioinformatics study did identify a putative serine β-lactamase in plants, although the authors of this paper speculated that enzyme was in fact a catabolic serine protease (23). β-Lactam containing antibiotics exert their antimicrobial properties by inactivating bacterial transpeptidases, which crosslink peptidoglycan building blocks in the cell wall. β-Lactam containing antibiotics do not affect plant cells in the same way. In mammalian cells, there are reports indicating that cephalosporins are nephrotoxic (24), and the toxicity is apparently caused by either the inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase (25) or by interfering with carnitine transport in the mitochondria (26). It has been suggested that β-lactams can enter animal cells via the OCTN2 transporter (27). However, at this time what role if any β-lactamase activity plays in plant mitochondria is unclear.

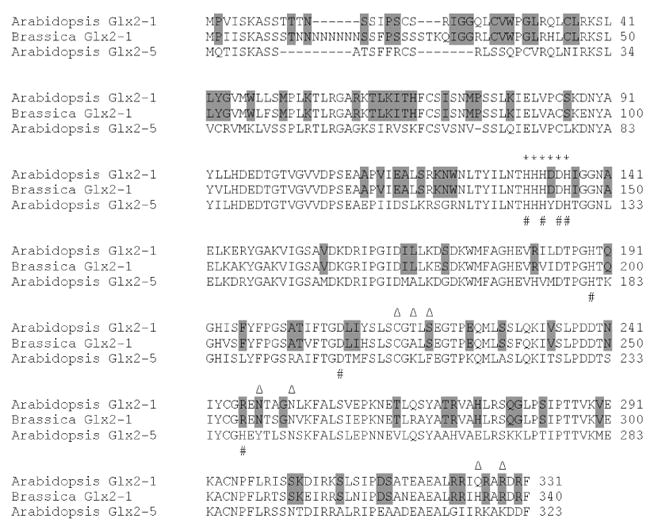

Database searching indicated a Glx2-1 homologue is not present in the completed genome sequences of other organisms, including those of rice and poplar, or in the available cDNA and EST sequence databases. We did however identify a potential Glx2-1 gene in the partial Brassica (Figure S4) and Arabidopsis lyrata genomic sequences (see Figure S5 for phylogenetic tree). Primers based on the Brassica sequence were used in RT-PCR experiments to isolate a full-length cDNA for Brassica Glx2-1, which is shown aligned with Arabidopsis Glx2-1 and Glx2-5 in Figure 3. Therefore, while Glx2-1 does not appear to be widespread in nature, it is found in Arabidopsis and related crucifers. We propose that Glx2-1 may represent an example of ongoing gene evolution (i.e., gene duplication and divergence of activity). Duplication and functional divergence of an ancestral mitochondrial Glx2 gene has led to the emergence of β-lactamase activity in Glx2-1. At this time it is not clear if Glx2-1 hydrolyzes β-lactams in plant cells, or if it has a different preferred substrate. Glx2 and many of the β-lactamases play protective roles in the cell; therefore, we predict that ultimately this may also be the case for Glx2-1.

Figure 3.

Alignment of predicted plant mitochrondria Glx2-1 and Glx2-5 from A. thaliana and Glx2-1 from Brassica. The * marks the β-lactamase fold, metal binding motif. The # marks the highly-conserved metal binding residues, and the Δ marks the substrate binding residues of Glx2-5. Residues conserved in Glx2-1, but differing in Glx2-5 are shaded.

Discovery of β-lactamase activity in a glyoxalase scaffold as well as the wide range of activities catalyzed by the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily (1) suggests that these proteins may be excellent templates for evolving new functions. However, the fact that the amidohydrolase superfamily (28, 29) has an entirely different protein scaffold, yet shares some mechanistic features and some of the same promiscuous activities with metallo-β-lactamase superfamily members suggests that the metal centers of these enzymes may serve as an inherently promiscuous catalytic unit that is refined and enhanced by changes to its local protein environment in response to selective pressures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM076199 to CAM), Miami University/Volwiler Professorship (to MWC), Miami University Presidential Academic Enrichment fellowship (to PL) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-1572 to WF). The authors thank Prof. Richard Moore of Miami University for his assistance in generating the phylogenetic tree.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental procedures are given in Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Pattraranee Limphong, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, 160 Hughes Hall, 701 E. High Street, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056.

George Nimako, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, 160 Hughes Hall, 701 E. High Street, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056.

Pei W. Thomas, Division of Medicinal Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712

Walter Fast, Division of Medicinal Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712.

Christopher A. Makaroff, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, 160 Hughes Hall, 701 E. High Street, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056

Michael W. Crowder, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, 160 Hughes Hall, 701 E. High Street, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056

References

- 1.Daiyasu H, Osaka K, Ishino Y, Toh H. FEBS Lett. 2001;503:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawashima Yasuyuki, O T, Shibata Naoki, Higuchi Yoshiki, Wakitani Yoshiaki, Matsuura Yusuke, Nakata Yusuke, Takeo Masahiro, Kato Dai-ichiro, Negoro Seiji. FEBS J. 2009;276:2547–2556. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Sierra-Gallay IL, Pellegrini O, Condon C. Nature. 2005;433:657–661. doi: 10.1038/nature03284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowder MW, Spencer J, Vila AJ. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:721–728. doi: 10.1021/ar0400241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marasinghe GPK, Sander IM, Bennett B, Periyannan G, Yang KW, Makaroff CA, Crowder MW. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40668–40675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509748200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Young J, Sukdeo N, Honek JF. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;459:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talesa V, Rosi G, Contenti S, Mangiabene C, Lupattelli M, Norton SJ, Giovannini E, Principato GB. Biochem Internat. 1990;22:1115–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oray B, Norton SJ. Meth Enzymology. 1982;90:547–551. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)90183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Timari A, Douglas KT. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;870:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron AD, Ridderstrom M, Olin B, Mannervik B. Structure. 1999;7:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limphong P, McKinney RM, Adams NE, Bennett B, Makaroff CA, Gunasekera TS, Crowder MW. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5426–5434. doi: 10.1021/bi9001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maiti MK, Krishnasamy S, Owen HA, Makaroff CA. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35:471–481. doi: 10.1023/a:1005891123344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenzel NF, Carenbauer AL, Pfiester MP, Schilling O, Meyer-Klaucke W, Makaroff CA, Crowder MW. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:429–438. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holdorf MM, Bennett B, Crowder MW, Makaroff CA. J Inorg Biochem. 2008;102:1825–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCoy JG, Bingman CA, Bitto E, Holdorf MM, Makaroff CA, Phillips GNJ. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:964–970. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906020592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiranti V, Viscomi C, Hildebrandt T, Di Meo I, Mineri R, Tiveron C, Levitt MD, Prelle A, Fagiolari G, Rimoldi M, Zeviani M. Nature Medicine. 2009;15:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nm.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limphong P, Crowder MW, Bennett B, Makaroff CA. Biochem J. 2009;417:323–330. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas PW, Stone EM, Costello A, Tierney DL, Fast W. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7559–7569. doi: 10.1021/bi050050m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullah JH, Walsh TR, Taylor IA, Emery DC, Verma CS, Gamblin SJ, Spencer J. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:125–136. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felici A, Amicosante G, Oratore A, Strom R, Ledent P, Joris B, Fanuel L, Frere JM. Biochem J. 1993;291:151–155. doi: 10.1042/bj2910151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park HS, Nam SH, Lee JK, Yoon CN, Mannervik B, Benkovic SJ, Kim HS. Science. 2006;311:535–538. doi: 10.1126/science.1118953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coulthurst SJ, Barnard AML, Salmond GPC. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:295–306. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liobikas J, Baniulis D, Stanys V, Toleikis A, Eriksson O. Biologija. 2006:126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tune BM, Hsu CY. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:194–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiyomiya Ki, Matsushita N, Matsuo S, Kurebe M. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;167:151–156. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pochini L, Galluccio M, Scumaci D, Giangregorio N, Tonazzi A, Palmieri F, Indiveri C. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;173:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganapathy ME, Huang W, Rajan DP, Carter AL, Sugawara M, Iseki K, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1699–1707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roodveldt C, Tawfik DS. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12728–12736. doi: 10.1021/bi051021e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seibert CM, Raushel FM. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6383–6391. doi: 10.1021/bi047326v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.