Abstract

AIM: To assess sustained virological response (SVR) rates in a predominantly hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 4 infected population.

METHODS: Between 2003-2007, 240 patients who were treated for chronic hepatitis C infection at our center were included. Epidemiological data, viral genotypes, and treatment outcomes were evaluated in all treated patients. Patients with chronic renal failure, previous non-responders, and those who relapsed after previous treatment were excluded from the study. Among all patients, 57% were treated with PEG-interferon (IFN) α-2a and 43% patients were treated with PEG-IFN α-2b; both groups received a standard dose of ribavirin.

RESULTS: 89.6% of patients completed the treatment with an overall SVR rate of 58%. The SVR rate was 54% in genotype 1, 44% in genotype 2, 73% in genotype 3, and 59% in genotype 4 patients. There was no statistical difference in the SVR rate between patients treated with PEG-IFN α-2a and PEG-IFN α-2b (61.5% vs 53%). Patients younger than 40 years had higher SVR rates than older patients (75% vs 51%, P = 0.001). SVR was also statistically significantly higher when the HCV RNA load (pretreatment) was below 800.000 (64% vs 50%, P = 0.023), in patients with a body mass index (BMI) less than 28 (65% vs 49%, P = 0.01), and in patients who completed the treatment duration (64% vs 8%, P ≤ 0.00001).

CONCLUSION: The SVR rate in our study is higher than in previous studies. Compliance with the standard duration of treatment, higher ribavirin dose, younger age, lower BMI, and low pretreatment RNA levels were associated with a higher virological response.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus infection, Sustained virological response, Genotype 4

INTRODUCTION

Chronic infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects about 170 million individuals worldwide. The natural history of chronic hepatitis C has been difficult to clearly define because of the long course of the disease; however multiple studies suggest that 20%-30% of infected patients eventually develop cirrhosis and its complications[1]. Regardless of the mode of transmission, chronic hepatitis follows acute hepatitis C in 50%-85% of infected patients[2]. Genotypes 1-4 account for nearly 90% of HCV-infected cases and genotype 4 is the most prevalent genotype in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia. Genotype 1 is the next common, while genotypes 2, 3 and 5 are the least prevalent[3-5]. Treatment of chronic HCV is aimed at slowing disease progression, preventing complications of cirrhosis, reducing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and treating extrahepatic complications[6]. The most effective therapy is the combination of PEGylated interferon (IFN) plus ribavirin. The benefit is mostly achieved in patients with HCV genotype 2 and 3 infections[7]. Most of the published literature on management of HCV involves genotypes 1, 2 and 3. The data on treating hepatitis in the Middle East, in which genotype 4 predominates, is limited. A recent study assessing sustained virological response (SVR) in Saudi Arabia revealed an SVR rate of around 48% in patients infected with HCV genotype 4; however, only PEG-IFN α-2a (PEGASYS) was used and they also included patients who were considered difficult to treat[8]. Limitations of other studies include small number of patients, use of conventional interferons, and the lack of viral genotype data[9]. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to (1) assess the SVR rates in treatment naïve patients; (2) compare the outcome of treatment using both PEG-IFN α-2b and PEG-IFN α-2a; and (3) define the predictors of SVR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective chart review of 400 patients treated at our center between January 2003 and January 2007 was conducted. All HCV treatment naïve patients with a positive PCR were included. Exclusion criteria included (1) pediatric patients; (2) chronic renal failure patients; (3) previous non-responders and those who had a relapse following prior treatment; (4) post renal transplant patients; and (5) patients with cirrhosis and signs of portal hypertension.

Biochemical assessments, including ALT (normal value: 0-58 IU/L), AST (normal value: 0-36 IU/L), γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, albumin, and coagulation profile, were done according to our laboratory standards.

Serum HCV RNA was extracted using an automated extraction system. HCV detection and quantification were performed using the COBAS Ampliprep™ /COBAS TaqMan™ HCV test (Roche diagnostics) utilizing different sets of primers and probes, which target a conserved region of the 5’ untranslated region of the genome. The main processes of this procedure include: (1) specimen preparation to isolate HCV RNA; (2) reverse transcription of the target RNA to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) and (3) simultaneous PCR amplification of target cDNA and detection of cleaved dual-labeled oligonucleotide detection probe specific to the target. This assay detects and quantifies HCV genotype (1-6) with a detection limit that ranges from 15 to 69 000 000 IU/mL. Prior to treatment, the HCV genotype was assayed using INNO-LiPA HCVII (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium).

After reviewing the patients’ data, 240 patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were selected for the study. Epidemiological data and treatment records were reviewed. Liver biopsy is not done routinely in our center unless there is suspicion of underlying cirrhosis or a concomitant liver disease. For data entry, patients were divided according to their gender, viral load (HCV RNA below vs above 8 00 000 IU/mL), age (younger vs older than 40), treatment (PEG-IFN α-2a vs PEG-IFN α-2b), liver enzyme pattern (normal vs abnormal), and body mass index (BMI) (below vs above 28) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Variable | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

| Age (yr) | ||

| < 40 | 68 | 28.3 |

| > 40 | 172 | 71.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 110 | 45.8 |

| Male | 130 | 54.2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| < 28 | 131 | 54.5 |

| > 28 | 109 | 45.5 |

| Liver enzymes | ||

| Normal | 115 | 47.9 |

| Abnormal | 125 | 52.1 |

| PCR (IU/mL) | ||

| < 800 000 | 138 | 57.5 |

| > 800 000 | 102 | 42.5 |

| Duration | ||

| Completed | 215 | 89.6 |

| Incomplete | 25 | 10.4 |

| Side effects | ||

| Present | 125 | 52.1 |

| Absent | 115 | 47.9 |

| Drug | ||

| Peg IFN α-2A | 138 | 57.5 |

| Peg IFN α-2B | 102 | 42.5 |

| Genotype | ||

| Genotype 1 | 46 | 19.2 |

| Genotype 2 | 9 | 3.8 |

| Genotype 3 | 15 | 6.3 |

| Genotype 4 | 82 | 34.2 |

| Genotype 5 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Not identified | 5 | 2.1 |

| No records | 82 | 34.2 |

| ETVR | ||

| Responded | 160 | 66.7 |

| No response | 80 | 33.3 |

| SVR | ||

| SVR | 139 | 58.0 |

| No SVR | 101 | 42.0 |

BMI: Body mass index; ETVR: End of treatment virological response; SVR: Sustained virological response.

Patients received either PEG-IFN α-2a (40 Kd; PEGASYS, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at a dose of 180 mg/wk or PEG-IFN α-2b (12 Kd; PEGINTRON, Schering-Plough LTD, Singapore) at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg, and a standard dose of 1200 mg ribavirin with no weight related adjustments. While on treatment, patients were followed monthly or more frequently if required. Complete blood count (CBC) and liver enzymes were checked at each visit. To maintain the starting dose of PEGylated interferon and ribavirin, erythropoietin and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) were given as early as possible to overcome any potential treatment-induced anemia or neutropenia. Patients with genotype 2 and 3 were treated for 24 wk, while patients with genotypes 1, 4 and 5 were treated for 48 wk. Viral loads were repeated at 12 wk to assess those who achieved an early virological response (EVR), at the end of treatment to assess the end of treatment virological response (ETVR), and six mo later to confirm an SVR. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected using a specialized data collection form, then introduced into a Microsoft Exel worksheet and finally transferred to the statistical package for social sciences version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Analyses used included descriptive statistics as well as a Students t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

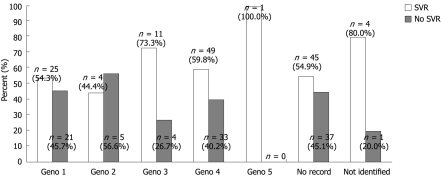

Eighty-two (34%) patients were genotype 4, while 46 (19.2%), nine (3.8%), 15 (6.3%), and one (0.4%) had genotypes 1, 2, 3 and 5, respectively. The genotype could not be identified in five (2.1%) patients, while the genotype data was missing in 82 (34.2%) patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Response rates among the different genotypes. SVR: Sustained virological response.

Two hundred and fifteen (89.6%) patients completed the treatment, while 25 (10.4%) patients could not complete the treatment because of significant side effects. In the entire cohort (n = 240), end of treatment Virological response (ETVR) was achieved in 160 (66.7%). 139 (58%) patients achieved SVR, while 101(42%) did not respond or had a relapse after achieving ETVR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall treatment outcomes

| Treatment outcome | Frequency (%) |

| SVR | 139 (58) |

| Relapse | 17 (7) |

| Primary non responder | 61 (25) |

| Intolerant | 23 (10) |

| Total | 240 (100) |

One hundred and twenty five (52.1%) had side effects, while 115 (47.9%) did not report any treatment related side effects. None of the patients required a blood transfusion for anemia. One hundred and thirty eight (57.5%) patients were treated with PEG-IFN α-2a while 102 (42.5%) patients received PEG-IFN α-2b. Among those who were treated with PEGylated IFN α-2a, the SVR was 61.5% and for those who were treated with PEG-IFN α-2b it was 53%, this did not reach statistical significance.

Younger patients achieved statistically significantly higher SVR rates compared to older patients. This observation is in agreement with other studies and we believe that this is because younger patients, in addition to tolerating full treatment doses, have a less advanced fibrosis stage compared to older patients (75% vs 51%, P = 0.001).

Other statistically significant predictors of achieving a SVR in the present study include compliance to a full treatment duration (64% vs 8%, P < 0.00001), a BMI lower than 28 (65% vs 49%, P = 0.01), and a pretreatment HCV RNA load below 800 000 IU/mL (64% vs 50%, P = 0.023). SVR rates were similar in relation to patient’s gender, liver enzyme pattern, and the type of drug used (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients who achieved an SVR

| Variable | Number of patients | SVR (%) | P value |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 40 | 51 | 75 | 0.001 |

| > 40 | 88 | 51 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 57 | 52 | NS |

| Male | 82 | 63 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| < 28 | 85 | 65 | 0.01 |

| > 28 | 54 | 49 | |

| PCR (IU/mL) | |||

| < 800 000 | 88 | 64 | 0.023 |

| > 800 000 | 51 | 50 | |

| Drug | |||

| Peg IFN α-2A 180 μg/wk | 85 | 62 | NS |

| Peg IFN α-2B 1.5 μg/kg per week | 54 | 53 | |

| Liver enzymes | |||

| Normal | 69 | 60 | NS |

| Abnormal | 70 | 56 | |

| Treatment duration | |||

| Completed | 137 | 64 | 0.00001 |

| Not completed | 2 | 8 |

NS: No significant.

DISCUSSION

Most of the data on HCV management originates from western populations in which genotypes 1, 2, and 3 predominate. There is less data from populations where the prevalence of HCV is much higher and in which HCV genotype 4 predominates. Initial studies with conventional interferon and ribavirin resulted in lower SVR rates, giving the impression that genotype 4 is difficult to treat[10]. One of the first trials on the treatment of HCV using PEGylated interferon in our region was conducted by Alfaleh et al[11]. In their study, 48 wk of PEG-IFN α-2b and ribavirin combination therapy resulted in an SVR rate of around 43%. One of the possible explanations for this relatively low SVR is the use of an 800 mg fixed dose of ribavirin daily. More recently Al Ashgar et al[8] published their results in which 335 patients treated with PEG-IFN α-2a and ribavirin achieved an SVR rate of around 48%. In this study, they adjusted the ribavirin dose according to the body weight. They also included renal failure patients, patients who failed previous interferon based treatment, and patients with concomitant HBV or HIV.

Other studies originating from our region, using a combination therapy of PEG-IFN α-2b and ribavirin, resulted in SVR rates of 43% to 68%[9,11-14].

In the present study, only treatment naive patients were included. 58% of the patients achieved an SVR (64% excluding the patients that didn’t complete the treatment). The following exclusion criteria were used to achieve a more homogenous study population: previously failed interferon based treatment, renal failure patients, and patients with a concomitant HBV/HIV.

In the present study, both PEG-IFN α-2a and PEG-IFN α-2b were used, with comparable results. A fixed dose of ribavirin was also given to the whole study population with no weight-based adjustment. This approach is considered to be an effective method for improving the outcome[9], and likely contributed to the higher SVR rate in our study compared to previous studies on genotype 4 infected patients. SVR was achieved by 64% of patients in whom the treatment duration was completed, while only 2% of patients who did not complete the treatment achieved SVR. This confirms the importance of compliance in achieving SVR, as suggested by other studies[15].

Duration of Treatment with PEG-IFN and ribavirin is individualized according to initial treatment response, genotype, and pretreatment viral load. Patients with HCV genotype 1 and 4 require treatment for 48 wk and those with genotypes 2 or 3 seem to be adequately treated in 24 wk[16,17]. Some investigators tried treatment durations of 16 wk for HCV genotypes 2 and 3 infected patients who had a rapid virological response at four wk, with variable results. In one study, SVR was lower in patients treated for 16 wk than in patients treated for 24 wk, and the rate of relapse was significantly greater in the 16-wk group[18]. Other studies show that extending the treatment duration from 48 wk to 72 wk in genotype 1 patients with slow virological response to PEG-IFN and ribavirin significantly improves SVR rates[19]. The current practice worldwide is to treat HCV genotype 4 patients for 48 wk. However, recent data suggests treating chronic HCV genotype 4 patients for 24 and 36 wk might be sufficient when viral loads are undetectable at four and 12 wk, respectively[14]. Whether extending the treatment to 72 wk in genotype 4 patients with a slow response will increase the SVR rate is yet to be determined.

Factors that are thought to be associated with a favorable outcome include genotype 2 and 3, mild hepatitis, minimal fibrosis, absence of obesity, and female gender[20]. Genotype 1, serum HCV RNA concentrations over 800 000 IU/mL, advanced duration of infection, histologically advanced liver disease, increased bodyweight, relapse or no response to previous treatment, presence of cirrhosis, African-American ethnicity, and advanced age were among the factors that are thought to be associated with a less favorable outcome[21].

In the present study, patients with genotype 4 were treated for 48 wk and achieved an SVR of 64% in the patients who completed the treatment duration. Younger patients, low pretreatment viral load, lower BMI, and compliance with the standard duration of treatment were associated with a higher SVR. This study supports the view that treatment results of genotype 4 HCV naïve patients are more favorable than has been previously suggested when higher doses of ribavirin are used.

COMMENTS

Background

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major health problem and it is the main indication for orthotopic liver transplantation among adults. PEGylated interferon (IFN) and ribavirin combination therapy is the standard treatment, but data regarding sustained virological response (SVR) in our predominantly HCV genotype 4 infected population is limited.

Research frontiers

HCV genotype 4 is the most frequent cause of chronic hepatitis C in the Middle East and North Africa. In Saudi Arabia, disease prevalence is estimated at 2.5%. Initial studies suggested that genotype 4 was difficult to treat and was associated with a low SVR.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The use of PEGylated interferon and ribavirin resulted in a higher SVR rate in patients infected with genotype 4 when higher doses of ribavirin are given. In the study, patients were given a fixed high dose of ribavirin, and it is believed that this contributed to the higher SVR rates in the study compared to previous studies. Additionally, it is shown that younger patients, patients with lower body mass index, and patients with low viral loads had a better treatment outcome.

Applications

This study supports the view that treatment results of genotype 4 HCV naïve patients are more favorable than has been previously suggested when higher doses of ribavirin are used.

Peer review

The article concerns a very topical problem-interferon therapy effectiveness in HCV-patients. The content of the article will be interesting, not only for gastroenterologists, but also for practical medicine.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Vasiliy I Reshetnyak, MD, Professor, Scientist Secretary of the Scientific Research Institute of General Reanimatology, 25-2, Petrovka str., 107031, Moscow, Russia

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Yin DH

References

- 1.Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology. 2008;48:418–431. doi: 10.1002/hep.22375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrera JM, Bruguera M, Ercilla MG, Gil C, Celis R, Gil MP, del Valle Onorato M, Rodés J, Ordinas A. Persistent hepatitis C viremia after acute self-limiting posttransfusion hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1995;21:639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Traif I, Handoo FA, Al-Jumah A, Al-Nasser M. Chronic hepatitis C. Genotypes and response to anti-viral therapy among Saudi patients. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1935–1938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payan C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Marcellin P, Bled N, Duverlie G, Fouchard-Hubert I, Trimoulet P, Couzigou P, Cointe D, Chaput C, et al. Changing of hepatitis C virus genotype patterns in France at the beginning of the third millenium: The GEMHEP GenoCII Study. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shobokshi OA, Serebour FE, Skakni L, Al-Saffy YH, Ahdal MN. Hepatitis C genotypes and subtypes in Saudi Arabia. J Med Virol. 1999;58:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yee HS, Currie SL, Darling JM, Wright TL. Management and treatment of hepatitis C viral infection: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center program and the National Hepatitis C Program office. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2360–2378. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Ashgar H, Khan MQ, Helmy A, Al Swat K, Al Shehri A, Al Kalbani A, Peedikayel M, Al Kahtani K, Al Quaiz M, Rezeig M, et al. Sustained Virologic Response to Peginterferon alpha-2a and Ribavirin in 335 Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C: A Tertiary Care Center Experience. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:58–65. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.39619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khuroo MS, Khuroo MS, Dahab ST. Meta-analysis: a randomized trial of peginterferon plus ribavirin for the initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:931–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koshy A, Marcellin P, Martinot M, Madda JP. Improved response to ribavirin interferon combination compared with interferon alone in patients with type 4 chronic hepatitis C without cirrhosis. Liver. 2000;20:335–339. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfaleh FZ, Hadad Q, Khuroo MS, Aljumah A, Algamedi A, Alashgar H, Al-Ahdal MN, Mayet I, Khan MQ, Kessie G. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Saudi patients commonly infected with genotype 4. Liver Int. 2004;24:568–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasan F, Asker H, Al-Khaldi J, Siddique I, Al-Ajmi M, Owaid S, Varghese R, Al-Nakib B. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1733–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamal SM, El Tawil AA, Nakano T, He Q, Rasenack J, Hakam SA, Saleh WA, Ismail A, Aziz AA, Madwar MA. Peginterferon {alpha}-2b and ribavirin therapy in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4: impact of treatment duration and viral kinetics on sustained virological response. Gut. 2005;54:858–866. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.057182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamal SM, El Kamary SS, Shardell MD, Hashem M, Ahmed IN, Muhammadi M, Sayed K, Moustafa A, Hakem SA, Ibrahiem A, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C: The role of rapid and early virologic response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1732–1740. doi: 10.1002/hep.21917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roulot D, Bourcier V, Grando V, Deny P, Baazia Y, Fontaine H, Bailly F, Castera L, De Ledinghen V, Marcellin P, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and response to peginterferon plus ribavirin treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:460–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H Jr, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Wagner M, Huber M, Berg T, Hinrichsen H, Rasenack J, Heintges T, Bergk A, Bernsmeier C, Häussinger D, Herrmann E, et al. Peginterferon-alpha-2a (40KD) and ribavirin for 16 or 24 weeks in patients with genotype 2 or 3 chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiffman ML, Suter F, Bacon BR, Nelson D, Harley H, Solá R, Shafran SD, Barange K, Lin A, Soman A, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for 16 or 24 weeks in HCV genotype 2 or 3. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:124–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearlman BL, Ehleben C, Saifee S. Treatment extension to 72 weeks of peginterferon and ribavirin in hepatitis c genotype 1-infected slow responders. Hepatology. 2007;46:1688–1694. doi: 10.1002/hep.21919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Bisceglie AM, Ghalib RH, Hamzeh FM, Rustgi VK. Early virologic response after peginterferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin or peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:721–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeuzem S. Heterogeneous virologic response rates to interferon-based therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: who responds less well? Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:370–381. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]