Abstract

We previously found that the endogenous anticonvulsant adenosine, acting through A2A and A3 adenosine receptors (ARs), alters the stability of currents (IGABA) generated by GABAA receptors expressed in the epileptic human mesial temporal lobe (MTLE). Here we examined whether ARs alter the stability (desensitization) of IGABA expressed in focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) and in periglioma epileptic tissues. The experiments were performed with tissues from 23 patients, using voltage-clamp recordings in Xenopus oocytes microinjected with membranes isolated from human MTLE and FCD tissues or using patch-clamp recordings of pyramidal neurons in epileptic tissue slices. On repetitive activation, the epileptic GABAA receptors revealed instability, manifested by a large IGABA rundown, which in most of the oocytes (≈70%) was obviously impaired by the new A2A antagonists ANR82, ANR94, and ANR152. In most MTLE tissue-microtransplanted oocytes, a new A3 receptor antagonist (ANR235) significantly improved IGABA stability. Moreover, patch-clamped pyramidal neurons from human neocortical slices of periglioma epileptic tissues exhibited altered IGABA rundown on ANR94 treatment. Our findings indicate that antagonizing A2A and A3 receptors increases the IGABA stability in different epileptic tissues and suggest that adenosine derivatives may offer therapeutic opportunities in various forms of human epilepsy.

Keywords: epilepsy, focal cortical dysplasia

Repetitive agonist activation of GABAA receptors causes a decrease in the amplitude of the ensuing ionic currents, leading to a use-dependent rundown of IGABA, due mostly to receptor desensitization. Of note, IGABA instability is greater, and its recovery slower, in refractory epileptic mesial temporal lobe (MTLE) tissue compared with non-MTLE tissues (1, 2). In the human brain, IGABA rundown reduces the efficacy of the GABAergic signal, which is inhibitory in the adult brain but excitatory in the immature brain (3). Thus, the IGABA rundown may be proexcitatory in the adult and proinhibitory in the early postnatal brain, as in forms of pediatric focal cortical dysplasia (PFCD) (4). Because the modulation of IGABA stability (desensitization) may become pathophysiologically relevant and determine the efficacy of the inhibitory GABAergic neurotransmission in the human brain (5–7), we investigated modulators of GABAA function with the aim of finding new antagonists of neuronal excitability, which may be useful in treating refractory epilepsy. We explored whether some recently synthesized antagonists of adenosine receptors (ARs) (8) are effective neuromodulators of GABAA inhibitory activity in the human brain. Actually, the purine ribonucleoside adenosine is considered an endogenous anticonvulsant in the brain, where dysfunction of the adenosine-based neuromodulatory system may contribute to epileptogenesis (9). But despite promising work on animal models emphasizing the role of ARs as effective therapeutic targets in epilepsy (10–12), conclusive evidence of a role in human refractory epilepsy has yet to be reported. In this work, we performed experiments on Xenopus oocytes injected with membranes obtained from human epileptic FCD or MTLE brains as wel as on temporal human pyramidal neurons. We found that GABAA desensitization was consistently altered by A2A and A3 antagonists, suggesting a possible association of ARs with the functional properties of the GABAAergic system.

Results and Discussion

Modulation of IGABA Rundown by AR Activity in Oocytes.

In agreement with our earlier experiments (5–7), application of GABA (500 μM, 10 s duration) to oocytes injected with membranes from the cortex of drug-resistant epileptic patients (patients 1–5; listed in Table S1) elicited inward currents ranging from −20 nA to −400 nA, depending on both the oocyte and the donor human/frog, and also on the lag between membrane injections and recordings. These GABA currents were blocked by the competitive GABAA antagonist bicuculline (100 μM; 8 oocytes, 2 frogs), and remained stable over time (1–2 h, with GABA applications every 120 s). But the IGABA elicited by receptors microtransplanted from neural tissues of epileptic patients affected with MTLE, PFCD, or adult FCD (AFCD) exhibited a considerable instability during repetitive (40-s interval) applications of neurotransmitter. On average, the normalized peak amplitude dropped to 71.7% ± 13.4% (mean ± SD) at the sixth GABA application in all of the MTLE patients examined (92 oocytes, 16 frogs, 92/16; patients 1–5), to 54.5% ± 12.1% in AFCD tissue–injected oocytes (65/11; patients 10–12), and to 49% ± 12.8% in PFCD tissue–injected oocytes (97/16; patients 6–9). These results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1 and 2, and Fig. S1. In MTLE tissue–injected oocytes, IGABA instability was not associated with a significant change in the current decay (T0.1 = 2.6 ± 0.3 s for control vs. 2.1 ± 0.3 s at the sixth GABA application, 10/3; P > .1), as reported previously (1). In contrast, the current decay after the rundown protocol was faster in both AFCD and PFCD tissue–injected oocytes (AFCD: T0.1 = 1.7 ± 0.2 s for control vs. 1.0 ± 0.1 s at the sixth GABA application, 15/3, P < .05; PFCD: T0.1 = 1.3 ± 0.1 s for control vs 0.8 ± 0.1 s at the sixth GABA application, 15/3, P < .05). These findings indicate different kinetics of GABAA receptor properties in various forms of epilepsy.

Table 1.

IGABA stability of GABAA receptors microtransplanted to oocytes from MTLE neocortex, increased with a few exceptions by treatement with different AR antagonists

| Drug treatment (dose) | Tested oocytes (frogs) [patients] | IGABA, %, before treatment (n) | IGABA, %, after treatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANR82 (100 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 31 (4) [1, 3, and 4] | 92 ± 4 (3) | 82 ± 3 | <0.01 |

| 63.2 ± 2.5 (19) | 77.4 ± 2.2 | <0.001 | ||

| ANR94 (100 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 22 (4) [2–5] | 51.3 ± 5.0 (3) | 38.7 ± 4.4 | <0.01 |

| 63.8 ± 3.3 (11) | 80.8 ± 4.4 | <0.001 | ||

| ANR152 (100 nM) [A2A and A1 antagonist] | 22 (4) [2 and 3] | 77.9 ± 3.9 (11) | 98.8 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| ANR235 (100 nM) [A3 antagonist] | 17 (4) [2, 3, and 5] | 71.4 ± 3.3 (13) | 88.6 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

n, number of oocytes tested with AR antagonists. Sets of cells in which rundown increases and n values are in bold. IGABA (%) values represent the sixth IGABA amplitude normalized to the first of the rundown protocol. ANR152 at 100 nM also antagonizes A1; see Table S2.

Table 2.

ARs antagonists generally stabilize GABAA receptors microtransplanted to oocytes from dysplastic neocortices

| Drug treatment (dose) | Tested oocytes (frogs) [patients] | IGABA, %, before treatment (n) | IGABA, %, after treatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFCD | ||||

| ANR82 (100 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 41 (6) [6–9] | 62.1 ± 4.8 (6) | 47.5 ± 2.4 | <0.01 |

| 45.8 ± 2.1 (27) | 60.9 ± 1.5 | <0.001 | ||

| ANR94 (100 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 20 (4) [6 and 7] | 46.5 ± 2.0 (10) | 55.5 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| ANR152 (100 nM) [A2A & A1 antagonist] | 12 (2) [6] | 51.7 ± 2.8 (8) | 69.0 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| ANR235 (100 nM) [A3 antagonist] | 24 (4) [6–8] | 48.5 ± 3.3 (24)* | 50.7 ± 2.9* | >0.5 |

| AFCD | ||||

| ANR82 (100 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 22 (3) [10 and 11] | 75 (1) | 66.7 | - |

| 51.6 ± 1.9 (18) | 69.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001 | ||

| ANR94 (100 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 23 (4) [10–12] | 56.2 ± 2.2 (13) | 72.6 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| ANR152 (100 nM) [A1 and A2A antagonist] | 12 (2) [10 and 12] | 51.7 ± 2.0 (9) | 64.5 ± 2.7 | <0.001 |

| ANR152 (10 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 11 (2) [12] | 59.7 ± 2.3 (9) | 67.2 ± 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Mix DPCPX (30 nM) [A1 antagonist] | 10 (2) [10] | 54.3 ± 4 (7) | 68.5 ± 4 | <0.001 |

| ANR152 (10 nM) [A2A antagonist] | 61.2 + 4 (3) | 58.8 ± 4* | >0.5 | |

| DPCPX (30 nM) [A1 antagonist] | 3 (1) [10] | 57.1 ± 1.3 (3) | 57.2 ± 0.7 | >.5 |

| ANR235 (100 nM) [A3 antagonist] | 8 (2) [10 and 11] | 42.6 ± 5.7 (8)* | 34.6 ± 3.5* | >.5 |

n, number of oocytes responsive to AR antagonists. Set of cells in which rundown increases and n are in bold. IGABA (%) values represent the sixth IGABA amplitude normalized to the first of the rundown protocol.

*, Not significantly different.

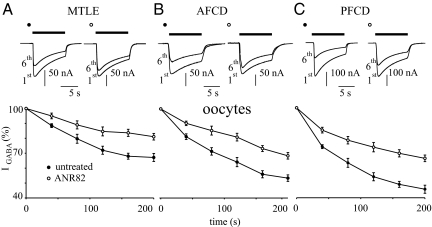

Fig. 1.

The A2A antagonist ANR82 (100 nM) decreases IGABA desensitization in oocytes microinjected with epileptic human membranes (as indicated). (A) (Top) Superimposed currents elicited by the first and sixth GABA (500 μM; horizontal bar) applications before (filled circles) and after (open circles) treatment with ANR82 in oocytes injected with MTLE neocortical membranes. Samples from 1 oocyte representative of 19 (4 frogs; patients 1, 3, and 4). Holding potential, −60 mV. (Bottom) Time course of IGABA rundown in 19 oocytes treated as indicated. IGABA values were normalized to the first IGABA peak current amplitude (filled circles, −126 ± 11nA; open circles, −142 ± 8). GABA 500 μM, 10 s duration at 40 s intervals. (B) (Top) Sample currents elicited as in (A) in oocytes injected with AFCD membranes. Samples from 1 oocyte representative of 18 (3 frogs; patients 10 and 11). (Bottom) Time course of IGABA rundown in 18 oocytes treated as indicated. Normalization of IGABA (filled circles, −111 ± 21 nA; open circles, −172 ± 10 nA), GABA concentration, and bar as (A). (C) (Top) Sample currents as in (A) from oocytes injected with PFCD neocortical membranes. Samples from 1 oocyte representative of 27 experiments (6 frogs; patients 6–9). (Bottom) Time course of IGABA rundown in 27 oocytes treated as indicated. IGABA amplitudes: filled circles, −230 ± 15 nA; open circles, −270 ± 22 nA (P < .01). Note the greater effect of ANR82 on PFCD oocytes.

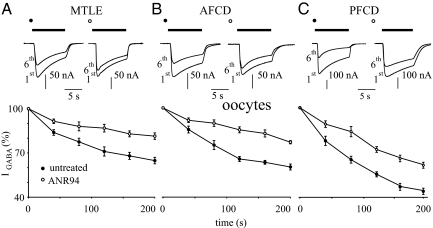

Fig. 2.

The A2A antagonist ANR94 (100 nM) decreases IGABA desensitization in oocytes microinjected with human epileptic neocortical membranes (as indicated). (A) (Top) Sample currents elicited as in Fig. 1A, from 1 oocyte representative of 11 injected with MTLE membranes (4 frogs; patients 2–5). (Bottom) Time course of the average rundown of 11 oocytes before (filled circles) and after 1 h of ANR94 treatment (open circles). Current normalization of IGABA (filled circles, −116 ± 19 nAfilled circles; open circles, −189 ± 7 nA) open circlesas in Fig. 1A. (B) (Top) Sample currents as in (A) from 1 oocyte injected with AFCD membranes representative of 13 experiments (4 frogs, patients 10–12). (Bottom) Time course averaged from 13 oocytes treated as indicated. IGABA normalized to −111 ± 8 nA (filled circles) and −156 ± 5 nA (open circles) (P < .01). (C) (Top) Sample currents as in (A) from 1 oocyte injected with PFCD membranes representative of 10 experiments (4 frogs, patients 6 and 7). (Bottom) Time course averaged from 10 oocytes treated as indicated. IGABA normalized as in Fig. 1A (filled circles, −184 ± 15 nA; filled circles open circles, −188 ± 8 nA) open circles (P > .05).

Adenosine is tonically released by a wide variety of cells, including Xenopus oocytes and brain cells (9, 10, 12–16). Moreover, we previously demonstrated that tonic activation of the ARs by adenosine can influence IGABA stability (5). Because ARs are widely expressed in the brain (13, 15), we used type-selective AR antagonists to determine which subtype is effective in modulating GABAA receptor desensitization. The antagonists used were checked for selectivity through binding affinity assays (Table S2). Thus, in some experiments we used a specific concentration of antagonist (i.e., 10 nM ANR 152) to selectively block one type of receptor, the A2A receptor. GABA applications with the A2A receptor antagonists ANR82 (100 nM), ANR94 (100 nM), and ANR152 (10 and 100 nM) reduced the IGABA desensitization in ≈70% of 275 oocytes microinjected with membranes isolated from MTLE or FCD tissues (Tables 1 and 2). This effect was reversible within 1 h after the antagonist was washed out (5). In the absence of pretreatment, the A2A receptor antagonists were ineffective, and, analogously, treatment with ANR82 did not modify the desensitization of human WT α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors expressed in oocytes (80.3% ± 7.3% before ANR82 and 78.9% ± 6.3% after ANR82; 10/2), indicating that the action of AR antagonists is not due to a direct interaction with GABAA receptors. In addition, the blockage of A1 receptors by 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX; 30 nM) had no effect (patient 10, 1 frog, 3 oocytes; Table 2), and cotreatment with DPCPX and ANR152 (10 nM) produced no additive effects (patient 10, 10 oocytes; Table 2). This indicates that A1 receptors are not involved in the modulation of IGABA stability. It was also found that ANR235, a selective A3 antagonist, induced a ≈20% reduction of the IGABA rundown in oocytes microinjected with MTLE tissue. In a small subset (≈10%) of oocytes, ANR82 increased the IGABA desensitization in MTLE and PFCD patients (Tables 1 and 2), in agreement with our previous results on A2A antagonists (5). Taken together, these findings confirm our previous report with different AR antagonists indicating that A2A and A3 receptors modulate IGABA stability in different types of epileptic tissues.

Action of ANR94 on IGABA Rundown in Human Pyramidal Neurons.

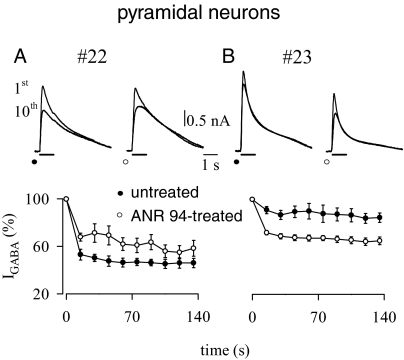

We previously reported that the blockage of all ARs subtypes by the nonselective antagonist CGS15943 impairs IGABA rundown in human epileptic temporal pyramidal neurons (5). To further elucidate the role played by specific ARs in modulating IGABA stability, we tested the effect of the AR antagonists on 28 temporal pyramidal neurons in slices obtained from adult MTLE patients (patients 13–19), from FCD patients (patients 20 and 21), and from peritumoral tissues (patients 22 and 23). In all these cells, repeated applications of GABA (100 μM, 1 s every 15 s; 10 times) produced an average drop in peak IGABA to 67% ± 26%. IGABA rundown from native MTLE pyramidal neurons in slices was not significantly affected by a 15-min pretreatment with ANR94 (100 nM; n = 10; IGABA = −1,637 ± 193 pA) (Table S3), in contrast to what was observed in oocytes (Fig. 2). In contrast, when the same antagonist was tested in neurons from peritumoral tissue (grade I ganglioglioma), it significantly decreased IGABA rundown (3 neurons). Specifically, in control conditions, the 10th current amplitude was 46% ± 7% of the first current amplitude, ranging from −1,893 to −2,241 pA (mean, −2,052 ± 102 pA). After the treatment with ANR94, the IGABA value fell to 59% ± 10% (P < .05) (Fig. 3A; Table S3). But in 5 neurons from peritumoral tissue resected from a pediatric patient with grade I ganglioglioma, the ANR94 treatment produced a larger IGABA desensitization, with IGABA rundown shifting from a drop to 85% ± 9% to a greater drop after drug administration (65% ± 9%; P < .05) (Fig. 3B; Table S3). These results merit further investigation, because they suggest possible differential activities of A2A receptors at different patient ages, rates of glioma cell infiltration of nerve tissue, or other affected parameters, such as tissue damage. Taken together, these findings demonstrate widely varying effects induced by AR antagonists on patch-clamped neurons, likely due to the dishomogeneous properties of morphological, functional, and biochemical tissues, including AR density and tonic release of local mediators, such as adenosine (17). This heterogeneity may obscure the drug efficacy, which would be better investigated in a more homogeneous system, such as the membrane-microtransplanted oocyte system (16, 18).

Fig. 3.

The A2A antagonist ANR94 decreases IGABA desensitization of temporal pyramidal neurons in human brain slices from a periglioma tissue (patient 22). (A) (Top) Sample currents elicited by the first and tenth GABA applications (100 μM; horizontal bars; holding potential, 0 mV) from a single neuron before and after a 15-min application of ANR94 (100 nM). (Bottom) Time courses averaged from 3 neurons under control conditions (filled circles) and after ANR 94 application (open circles). Current amplitudes were normalized to I1st. (B) In contrast to (A), ANR94 in a much younger patient afflicted with glioma (patient 23) increased desensitization. Traces and time courses are as in (A). Points here refer to means of 5 determinations (P < .001; 5 neurons).

In agreement with our previous report (5), our central finding in the present study is that the tonic activity of A2A and A3 receptors affects use-dependent IGABA stability, altering the inhibitory efficacy of GABA during overstimulation of the GABAAergic system. Furthermore, we confirm that A1 activity, which is not substantially involved in the GABAA function in MTLE (5), also is not significantly involved in GABAA receptor modulation in FCD-injected oocytes (Table 2). Moreover, adenosine release from glioma cells (17) could explain the effects of ANR94 in patch-clamped pyramidal cells from brain tumor periglioma tissues (Fig. 3; Table S3), in which an adenosine-induced overstimulation of endogenous ARs is likely. It does not clarify why the other A2A antagonists are ineffective on this same tissue, however.

As in our previous study (5), many questions remain, including the mechanisms by which A2A and A3 receptors influence the use-dependent GABAA function. It is well known that GABAA function is regulated by protein kinase systems, and that the effects of stimulating ARs likely are associated with MAPK and/or PKA activity, with specific effects depending on the activity of the different pathways (12, 19–24). Whatever the mechanism(s) responsible for the functional interactions between A2A/A3 receptors and neuronal GABAA, we present here evidence that blocking the A2A receptors in the human brain improves the stability of IGABA in different types of epilepsy. These results may help identify new treatments targeted at increasing the inhibitory GABAA efficacy, possibly leading to the development of a new family of adjuvant antiepileptic drugs to add to the large list of adenosine-related compounds currently available (12).

Materials and Methods

Patients.

Surgical specimens were obtained from the temporal neocortex of patients with MTLE (patients 1–5 and 13–19; Table S1), PFCD (patients 6–9), or AFCD (patients 10, 11, 12, 20, and 21) or with ganglioglioma (grade I; patients 22 and 23). Of these 23 patients, samples from 1 patient with AFCD (patient 10) and 3 patients with PFCD (patients 6, 7, and 9) were obtained from the Department of Neuropathology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam and the University Medical Center, Utrecht (Dr. W.G.M. Spliet). All of the other patients underwent surgery at the Neuromed Neurosurgery Center for Epilepsy, Pozzilli-Isernia, Italy. Informed consent was obtained from all patients to use part of the biopsy material for our experiments, and all tissue was used in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committees of Neuromed and the University of Rome “Sapienza” approved the patient selection processes and procedures. For all of the FCD patients, the classification system proposed by Palmini et al. (25) was used to grade the degree of FCD. More details about patients and screening analysis are provided in Table S1 and elsewhere (26).

Membrane Preparation, Injection Procedures, and Electrophysiologic Recordings from Oocytes.

Membranes were prepared as described previously using tissues from human epileptic brain regions (temporal lobe). Tissue specimens were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after surgical resection. Some experiments involved intranuclear injection of human cDNAs encoding the WT α1, β2, and γ2 GABAA subunits (kindly provided by Dr. Keith Wafford) in Xenopus oocytes. X. laevis oocytes and injection procedures were prepared as detailed previously (27). Between 12 and 48 h after injection, membrane currents were recorded from voltage-clamped oocytes using 2 microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl (28). The oocytes were placed in a recording chamber (0.1 mL volume) perfused continuously (9–10 mL/min) with oocyte Ringer's solution at room temperature (21–23 °C). The rundown of current elicited by GABA (i.e., GABAA current) was defined as the decrease (in %) in the peak current amplitude after 6 consecutive applications of GABA (500 μM; 10-s duration, 40-s interval). The fast GABAA current desensitization was measured as the time required for a 10% peak current decay (T0.1). In all experiments the holding potential was −60 mV. AR antagonists diluted in oocyte Ringer's solution were applied for 60 min after the control rundown protocol up to the end of the test rundown protocol. In some experiments, a 1-h washout with oocyte Ringer's solution was performed before initiation of a new rundown protocol.

Whole-Cell Recordings from Cortical Slices.

Neocortical slices were prepared from human FCD cortex, human temporal MTLE cortex, and human peritumoral cortex (for patients, see Table S1). Transverse slices (300 μm) were cut in glycerol-based artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) with a Leica VT 1000S vibratome (Leica Microsystems) immediately after surgical resection. The slices were placed in an incubation chamber at room temperature with oxygenated ACSF and then transferred to the recording chamber within 1–24 h after slice preparation. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed on pyramidal neurons at 21–23 °C as described previously (26). Under these experimental conditions, with inactivated voltage-gated channels, cells were stable and healthy for 1–2 h. GABA was delivered by pressure applications (10–20 psi for 1 s with a General Valve Picospritzer II) from glass micropipettes positioned above the voltage-clamped neurons. In this way, stable whole-cell currents and rapid drug wash were obtained before the rundown protocol was applied. The following current rundown protocol was adopted: After current amplitude stabilization with repetitive applications every 120 s, a sequence of 10 GABA applications of 1-s duration was delivered every 15 s, and the test pulse was resumed at the control rate (every 120 s) to monitor recovery of the GABA current. The reduction in peak amplitude current was expressed as percentage amplitude of current at the end of the rundown protocol (I10th) versus control (I1st). (For more details, see ref. 26.)

Chemicals and Solutions.

Oocyte Ringer's solution had the following composition (in mM): NaCl, 82.5; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 2.5; MgCl2, 1; and Hepes, 5, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. ACSF had the following composition (in mM): NaCl, 125; KCl 2.5; CaCl2, 2; NaH2PO4, 1.25; MgCl2, 1; NaHCO3, 26; glucose, 10; and Na-pyruvate, 0.1 (pH 7.35). Glycerol-based ACSF solution contained the following (in mM): glycerol, 250; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 2.4; MgCl2, 1.2; NaH2PO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 26; glucose, 11; and Na-pyruvate, 0.1 (pH 7.35). Patch pipettes were filled with the following (in mM): 140 K-gluconate, 10 Hepes, 5 1,2-Bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 2 MgCl2, and 2 Mg-ATP (pH 7.35, with KOH). All drugs were purchased from Sigma Italia with the exception of GABA and DPCPX (purchased from Tocris).

Statistics.

Unless noted otherwise, the data herein are reported as mean ± SEM. Differences among means were analyzed by 1-way or 2-way ANOVA. Values were considered significantly different when P < .05. To obtain the averaged time course of IGABA, single time-course data were normalized to the amplitude value recorded at the first GABA application of the rundown protocol.

Structures and Syntheses of Tested Adenosine Compounds.

The 8-substituted 9-ethyladenine derivatives ANR82, ANR94, and ANR152 were prepared as reported previously (8). The 9-cyclopentyl-8-phenylethynyladenine (ANR235) was obtained by reacting the corresponding 8-bromo analogue ANR168 (29) with ethynylbenzene, using a modification of the classical palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction (Table S2; Fig. S2) (30).

Evaluation of Receptor Binding Affinity.

The 8-substituted-9-ethyladenines (ANR82, ANR94, ANR152, and ANR235) (8) were evaluated for receptor binding affinity at human recombinant ARs, stably transfected into Chinese hamster ovary cells, using radioligand binding studies (AA1R, AA2AR, and AA3R). Receptor binding affinity was determined using [3H]CCPA (2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine) as the radioligand for AA1R, whereas [3H]NECA (5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine) was used for the AA2AR and AA3R subtypes (31). The data, reported as nM Ki, are given in Table S2.

Chemistry.

Melting points were determined with a Büchi apparatus and are uncorrected. 1H NMR spectra were obtained with Varian Mercury 400-MHz spectrometer (δ in ppm; J in Hz). All exchangeable protons were confirmed by addition of D2O. TLC was performed on precoated TLC plates with Merck silica gel 60 F-254. For column chromatography, Merck silica gel 60 was used. Elemental analyses were determined using a Fisons model EA 1108 CHNS-O analyzer and were within ± 0.4% of theoretical values.

ANR235.

To a solution of ANR168 (29) (0.200 mg; 0.71 mmol) in dry DMF (24 mL), (Ph3P)2PdCl2 (10 mg; 0.014 mmol), CuI (0.9 mg), Et3N (3.2 mL), and ethynylbenzene (0.47 mL; 4.26 mmol) were added under a nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 24 h. Volatiles were removed under vacuum, and the residue was chromatographed over a silica gel column eluting with CHCl3-cC6H12-CH3OH (85:10:5). ANR 235 was obtained after crystallization from CH3OH in 36% yield as a white solid. Mp, 203–205 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.75 (m, 2H, H-cyclopentyl), 2.08 (m, 4H, H-cyclopentyl), 2.32 (m, 2H, H-cyclopentyl), 5.13 (m, 1H, CH-N); 7.46 (bs, 2H, NH2); 7.52 (m, 3H, H-Ph); 7.69 (m, 2H, H-Ph); 8.17 (s, 1H, H-2). Anal. Calcd. for C18H17N5: C, 71.27; H, 5.65; N, 23.09; Found: C, 71.34; H, 5.80; N, 22.76.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are very grateful to the patients whose brain tissue has made this work possible, specifically L.M, E.V, T.S, M.R, T.N, DB.G, G.M., S.A., M.G., D.S.A., T.D., C.V., G.A., T.A., D.A.L., M.A., S.G., R.A., K.L. (who underwent neurosurgery at Neuromed, Pozzilli, Italy) and the patients classified at the Department of Neuropathology of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam as 6, 7, 9, and 10 and numbered accordingly herein. This work was supported by grants from the Ministero della Salute (to F.E.), Ministero Università & Ricerca (a PRIN Grant, to C.L), Fondo di Ricerca di Ateneo (University of Camerino, to G.C.), and Ministero della Salute Progetto Ordinario Neurolesi (RF-CNM-2007-662855, to G.C.). Additional financial support from the Mariani Foundation of Milan (Grant R-09–76, to F.E.) and the National Epilepsy Fund (Grant NEF 09–05, to E.A.) is gratefully acknowledged. C.R. thanks the Giovanni Armenise Harvard Foundation for support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0907324106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Palma E, et al. Phosphatase inhibitors remove the rundown of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors in the human epileptic brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10183–10188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403683101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodkin HP, Sun C, Yeh JL, Mangan PS, Kapur J. GABA(A) receptor internalization during seizures. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 5):109–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherubini E, Gaiarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: An excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cepeda C, et al. Immature neurons and GABA networks may contribute to epileptogenesis in pediatric cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 5):79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roseti, et al. Adenosine receptor antagonists alter the stability of human epileptic GABA(A) receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15118–15123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807277105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palma E, et al. BDNF modulates GABAA receptors microtransplanted from the human epileptic brain to Xenopus oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:1667–1672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409442102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palma E, et al. The GABAA-current rundown of temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with repetitive activation of GABAA receptors with low sensititiviy ot GABA and Zn2+ Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20944–20948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710522105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpini R, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor antagonists: New 8-substituted 9-ethyladenines as tools for in vivo rat models of Parkinson's disease. Chem Med Chem. 2009;4:1010–1019. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boison D. Adenosine as a neuromodulator in neurological diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boison D. The adenosine kinase hypothesis of epileptogenesis. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagonopoulou O, Efthimiadou A, Asimakoupoulos B, Nikolettos NK. Modulatory role of adenosine and its receptors in epilepsy: Possible therapeutic approaches. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM, De Mendonça A. Adenosine receptors in the nervous system: Pathophysiological implications. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;68:377–392. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gourine AV, et al. Release of ATP in the central nervous system during systemic inflammation: Real-time measurement in the hypothalamus of conscious rabbits. J Physiol. 2007;585:305–316. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fredholm B. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahima L, et al. Endogenous hemichannels play a role in the release of ATP from Xenopus oocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:95–102. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melani A, et al. Adenosine extracellular levels in human brain gliomas: An intraoperative microdialysis study. Neurosci Lett. 2003;346:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T, Ikeda K, Kumanishi T. Functional characterization of an endogenous Xenopus oocyte adenosine receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:313–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology, XXV: Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciruela F, et al. Heterodimeric adenosine receptors: A device to regulate neurotransmitter release. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2427–2431. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGaraughty S, Cowart M, Jarvis MF, Berman RF. Anticonvulsant and antinociceptive actions of novel adenosine kinase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:43–58. doi: 10.2174/1568026053386845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald BJ, et al. Adjacent phosphorylation sites on GABAA receptor beta subunits determine regulation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:23–28. doi: 10.1038/223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song M, Messing RO. Protein kinase C regulation of GABAA receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell-Horner CL, Dohi A, Nguyen Q, Dillon GH, Singh M. ERK/MAPK pathway regulates GABAA receptors. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:1467–1474. doi: 10.1002/neu.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmini A, et al. Terminology and classification of the cortical dysplasias. Neurology. 2004;62(6 Suppl 3):S2–S8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000114507.30388.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ragozzino D, et al. Rundown of GABA type A receptors is a dysfunction associated with human drug-resistant mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15219–15223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507339102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miledi R, Palma E, Eusebi F. Microtransplantation of neurotransmitter receptors from cells to Xenopus oocyte membranes: New procedure for ion channel studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;322:347–355. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-000-3_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miledi R. A calcium-dependent transient outward current in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982;215:49l–497. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambertucci C, et al. 8-Bromo-9-alkyl adenine derivatives as tools for developing new adenosine A2A and A2B receptor ligands. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:2812–2822. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nair V, Richardson SG. Modification of nucleic acid bases via radical intermediates: Synthesis of dihalogenated purine nucleosides. Synthesis. 1982;8:670–672. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klotz KN, et al. Comparative pharmacology of human adenosine subtypes: Characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:1–7. doi: 10.1007/pl00005131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.