Abstract

Plant innate immunity depends in part on recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as bacterial flagellin, EF-Tu, and fungal chitin. Recognition is mediated by pattern-recogntition receptors (PRRs) and results in PAMP-triggered immunity. EF-Tu and flagellin, and the derived peptides elf18 and flg22, are recognized in Arabidopsis by the leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases (LRR-RK), EFR and FLS2, respectively. To gain insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying PTI, we investigated EFR-mediated PTI using genetics. A forward-genetic screen for Arabidopsis elf18-insensitive (elfin) mutants revealed multiple alleles of calreticulin3 (CRT3), UDP-glucose glycoprotein glucosyl transferase (UGGT), and an HDEL receptor family member (ERD2b), potentially involved in endoplasmic reticulum quality control (ER-QC). Strikingly, FLS2-mediated responses were not impaired in crt3, uggt, and erd2b null mutants, revealing that the identified mutations are specific to EFR. A crt3 null mutant did not accumulate EFR protein, suggesting that EFR is a substrate for CRT3. Interestingly, Erd2b did not accumulate CRT3 protein, although they accumulate wild-type levels of other ER proteins. ERD2B seems therefore to be a specific HDEL receptor for CRT3 that allows its retro-translocation from the Golgi to the ER. These data reveal a previously unsuspected role of a specific subset of ER-QC machinery components for PRR accumulation in plant innate immunity.

Keywords: endoplasmic reticulum, innate immunity, receptor kinase

Plant innate immunity involves three main processes: Recognition of conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) leading to PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI), suppression of defense by pathogen effectors, and recognition of specific effectors by cytoplasmic host proteins resulting in effector-triggered immunity (ETI) (1–4). Three pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that can initiate PTI are known in the plant model Arabidopsis thaliana. Bacterial flagellin, and its peptide surrogate flg22 are recognized by the leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (LRR-RK) FLS2 (5), bacterial elongation factor (EF)-Tu, and its surrogate peptide elf18 are recognized by the related LRR-RK EFR (6), while recognition of fungal chitin and unknown bacterial PAMP(s) depend on CERK1, a LysM domain RK (7–9).

EFR and FLS2 are glycosylated transmembrane proteins (6, 10) and therefore need to enter the secretory pathway to mature and to reach their final plasma membrane destination. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the first organelle of the secretory pathway and is responsible for the proper folding and assembly of polypeptides that are then directed to the Golgi. After translocation in the ER, newly synthesized polypeptides interact with different chaperones that will assist them to fold properly and to avoid aggregation in a process called ER quality control (ER-QC) (11). Misfolded proteins are directed to ER-associated degradation, leading to their clearance by the ubiquitin-proteasome in the cytosol (12). Most of our knowledge on ER-QC is based on studies in yeast and mammals, while plant ER-QC mechanisms are still not well characterized (13). Studies in mammals and yeast have defined three main systems in the ER-QC (14). The first one relies on the retention of misfolded proteins by the luminal binding protein BiP, an ER member of the Hsp70 family of chaperone. In this system, the ER Hsp40 protein ERdj3 first binds directly to unfolded proteins. ERdj3 then recruits BiP and activates BiP's ATPase activity present in its N terminus, leading to interaction of the C-terminal region of BiP with the substrate and the release of ERdj3b (15, 16). The second involves recognition of free thiol groups and leads to the formation of disulfide bonds in non-native proteins by protein disulfide isomerases (PDIs) and other thiol oxidoreductases (17–19). Finally, the best studied system is specific to glycoproteins and relies on the so-called calnexin/calreticulin (CNX/CRT) cycle (20). CNX and CRT are lectins that interact with glycoproteins bearing monoglucosylated high-mannose type oligosaccharides via polypeptide based interactions (21). The enzyme UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase (UGGT) serves as a “folding sensor” (22, 23). In this system, client glycoproteins are delivered to UGGT after the trimming of their innermost glucose residue by glucosidase II, which releases them from the lectin-chaperones CNX and CRT. UGGT is inactive against folded proteins, allowing them to proceed to the Golgi apparatus for further processing to complex- or hybrid-type glycoforms. On the other hand, this enzyme efficiently glucosylates incompletely folded glycoproteins to monoglucosylated structures, providing them with an opportunity to interact with CNX/CRT.

We report here on three elf18-insensitive (ELFIN) genes that are specifically required for EFR function, all of which encode potential components of the ER-QC pathway. Surprisingly, although FLS2 and EFR belong to the same subfamily of LRR-RK (LRR-XII) and induce similar responses (6), the reported elfin mutations do not impair FLS2 function. We conclude that a dedicated subset of ER-QC components is specifically required for the proper accumulation of a subset of PRRs in plant innate immunity.

Results

Identification of CRT3 Mutant Alleles that Compromise EFR Signaling.

To better understand PTI, we screened 137,500 EMS-mutagenized M2 Arabidopsis Col-0 seeds for elf18-insensitive (elfin) mutants that lost seedling growth inhibition (SGI) in response to elf18 (24). Elfin5–4 was mapped to At1g08450, which encodes calreticulin 3 (CRT3) (Fig. S1 A and B). Sequencing of CRT3 in 103 elfin mutants revealed another nine alleles (Fig. 1 A and B and Fig. S1B). A SALK T-DNA insertion line in CRT3 (SALK_051336C: crt3–1; Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B) also showed loss of SGI in response to elf18 (Fig. 1A), confirming that CRT3 is required for elf18-triggered SGI. We raised a specific anti-CRT3 antibody and assessed CRT3 protein accumulation in the crt3 alleles; all showed reduced or abolished accumulation of CRT3 protein (Fig. 1C).

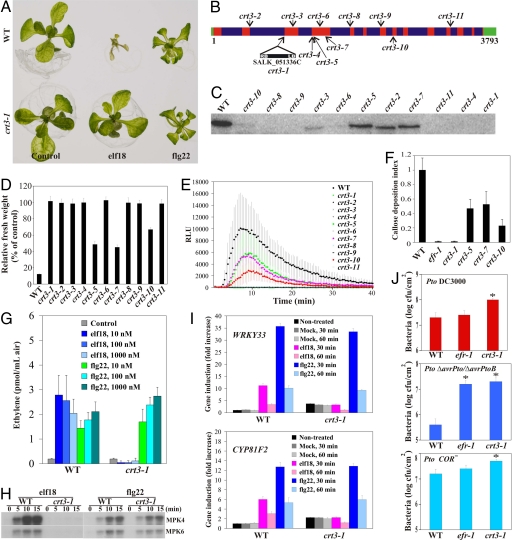

Fig. 1.

CRT3 is required for EFR-mediated responses. (A) Growth inhibition is completely blocked by elf18 but not by flg22 in crt3–1 mutants. WT (Col-0) and crt3–1 seedlings were grown for 9 days in the presence of 50 nM elf18 and 100 nM flg22, respectively. (B) Summary of crt3 alleles. The corresponding nucleotides in WT and mutants are indicated by their positions in the CRT3 gene, red or green letters, respectively. Green, red, and blue boxes indicate UTRs, exons, and introns, respectively. (C) Western blot on mutant lines using a CRT3-specific antibody. (D) Seedling growth of WT and crt3 mutants after treatment with 50 nM elf18. Treated and control seedlings were weighed 7 days after transfer to the peptide solution. Results shown are means ± SD (n = 8). (E) Oxidative burst induced by 100 nM elf18, and measured in relative light units (RLU) in leaf discs. Results are means ± SD (n = 12). (F) Callose deposition triggered by 100 nM elf18. Leaf samples were taken at 18 h after infiltration and stained with aniline blue for visualization of callose. The amount of callose was quantified with the program IMAGEJ. The data were normalized against WT. Results shown are means ± SD (n = 8). (G) Ethylene release in response to elf18 and flg22. Results shown are means ± SD (n = 4). (H) MAP kinase activation. Two-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings in liquid MS 1% were treated with 100 nM elf18 or flg22. MPK4 and 6 were affinity-purified using specific antibodies and used for in vitro kinase reactions performed with myelin basic protein (MBP) as a substrate in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. (I) Induction of defense marker genes WRKY33 and CYP81F2 by 100 nM elf18 or flg22 as determined by RT-qPCR. (J) Bacterial susceptibility assays in crt3–1 and WT. Plants were infected by spraying with suspensions of indicated strains (OD600 = 0.02). In planta grown bacteria were extracted from leaves at 3 dpi. Asterisks indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) from WT control as determined by Student's t test. Results are means ± SE (n = 4). All experiments were independently performed at least two times with similar results.

crt3 Mutants Are Compromised in EFR but Not FLS2 Signaling.

The crt3 alleles were compared for SGI induced by elf18 or flg22. Interestingly, all alleles showed reduced or abolished SGI by elf18 (Fig. 1D), but were wild-type (WT) in their SGI after flg22 treatment (Fig. S2A). We next compared crt3 alleles for elf18-triggered oxidative burst; all showed reduced or abolished oxidative burst by elf18 (Fig. 1E), but were WT in their response to flg22 (Fig. S2B). The partial loss in elf18-triggered SGI, oxidative burst, and callose deposition in the crt3–5, −7, and −10 alleles, correlated with a partial reduction in CRT3 protein (Fig. 1 C–F). The null crt3–1 T-DNA allele (Fig. 1C) was completely insensitive to elf18, as measured by SGI, oxidative burst, callose deposition, ethylene production, MAP kinase activation, and defense gene induction (Fig. 1 D–I). Chitin responses were also not compromised in crt3–1 mutants (Fig. S2 C and D). Thus, CRT3 is required for EFR, but not FLS2 or CERK1, function.

crt3 Mutants Are More Susceptible to Phytopathogenic Bacteria than efr Mutants.

We tested whether crt3–1 shows enhanced susceptibility to infection by the virulent strain Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 (Pto DC3000) and to isogenic hypovirulent strains deleted for effectors AvrPto and AvrPtoB (Pto DC3000 ΔavrPto/ΔavrPtoB) (25) or for synthesis of the phytotoxin coronatine (Pto DC3000 COR-) (26). AvrPto, AvrPtoB, and coronatine are virulence factors that suppress early PTI signaling; the use of mutant strains is therefore more likely to reveal phenotypes linked to PTI defects. While the efr-1 mutant showed significantly enhanced disease sensitivity only to Pto DC3000 ΔavrPto/ΔavrPtoB, the crt3–1 mutant was clearly more susceptible to all three Pto DC3000 strains (Fig. 1J). This suggests that EFR is not the only PRR whose function is compromised by CRT3 mutations.

CRT1 and CRT2 Play a Minor Role in PTI.

In addition to CRT3, Arabidopsis carries the closely related CRT1 and CRT2 genes (27), two related calnexin genes CNX1 and CNX2 (Fig. S3 A and B). Null Salk T-DNA insertion lines in CRT1 or CRT2 (Fig. S4 A–C) retained elf18-triggered SGI (Fig. S4F), but a crt1–1 crt2–1 double mutant showed a partial reduction in SGI by elf18 (Fig. S4 F–H). Furthermore, the crt1–1 crt2–1 double mutant showed partial reduction in oxidative burst (Fig. S4G), but not in defense gene induction (Fig. S4H), after elf18 treatment. CRT3 accumulation was not impaired in crt1 crt2 (Fig. S4C). However, a double mutant in two, more distantly related, calnexin genes, CNX1 and CNX2 (Fig. S4 D and E), showed no impairment in elf18-triggered SGI, oxidative burst, or defense gene induction (Fig. S4 F and G). Thus, loss of CRT1 together with CRT2 compromises EFR function to a certain extent, while loss of CRT3 alone abrogates EFR function completely.

CRT3 Is an ER-Localized Protein Required for EFR Protein Accumulation.

CRT1, 2, and 3 carry a signal peptide (SP) and a C-terminal HDEL sequence, which is classically associated with protein retention of soluble proteins in the ER (28). To confirm the CRT3 subcellular localization in planta, we engineered a CRT3-promoter SP-YFP-CRT3 fusion construct, in which a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) tag was introduced one amino acid after the predicted SP cleavage site (Fig. S5A). This construct was transiently coexpressed in Nicotiana benthamiana with a control ER marker construct, ER-CK (29). Both proteins colocalized, suggesting that CRT3 is localized in the ER (Fig. S5B).

We tested if the elf18-insensitivity of the crt3 mutant could be due to a defect in EFR protein localization or accumulation. We first tested whether EFR protein accumulation was reduced in the absence of CRT3 function. An EFR-promoter EFR-GFP-HA fusion construct (EGH) was transformed into a double mutant Arabidopsis line efr-1 crt3–1 or into a control efr-1 line. Multiple transgenic lines in the efr-1 crt3–1 background accumulated no or very little EGH protein (Fig. 2), whereas transgenic lines in the efr-1 background showed a strong signal in most lines as detected by anti-GFP immunoblots (Fig. 3, left lanes, and Fig. S6A). Transcript levels of the EFR-GFP-HA construct were, however, still detectable in efr-1 crt3–1 lines that do not accumulate EGH protein (Fig. S6B; the EGH transformant in efr-1 in Fig. 2 corresponds to line 4.1 in Fig. S6A). Thus, CRT3 is an ER-localized protein required for full EFR protein accumulation.

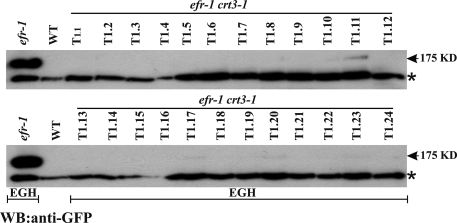

Fig. 2.

CRT3 is required for EFR accumulation. Accumulation of EFR-GFP-HA (EGH) fusion protein in efr-1 or efr-1 crt3–1 genetic backgrounds. Total proteins were extracted from primary transformants in WT nontransformed (lane 2, A and B), efr-1 (left lane, A and B), or efr-1 crt3–1. The EFR-GFP-HA (EGH) fusion protein was detected by an anti-GFP antiserum. The nonspecific band indicated by an asterisk provides a loading control.

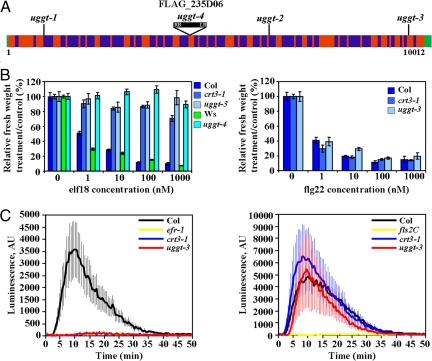

Fig. 3.

UGGT is required for elf18 but not flg22 responses. (A) Summary of uggt alleles. Schematic representation of the UGGT gene with UTRs (green), exons (red), and introns (blue). See Fig. S7B for details of each allele. (B) Seedling growth inhibition of WT and mutants after treatment with a series of elf18 and flg22 concentration. Treated and control seedlings were weighed seven days after transfer to the peptide solution. Results shown are means ± SD (n = 12). Due to natural deficiency in flagellin perception in Ws ecotype, seedling growth inhibition in presence of flg22 was not tested for uggt4. (C) Oxidative burst induced in uggt mutants by 100 nM elf18 and flg22, and measured in RLU in leaf discs. Results are means ± SD (n = 12). Three independent experiments show similar data.

Identification of UGGT Mutant Alleles that Compromise EFR but Not FLS2 Signaling.

We hypothesized that additional components of the calnexin/calreticulin cycle might be identified in the elfin screen. Arabidopsis UGGT is encoded by a single gene, At1g71220, and is ER localized (30). We found that elfin21–2 mapped to this region (Fig. S7A), and sequencing revealed a point mutation corresponding to allele uggt-3 (Fig. 3A and Fig. S7B). DNA sequencing of At1g71220 in additional elfin mutants revealed an additional two EMS-induced UGGT alleles (Fig. 3A and Fig. S7B). The allele uggt-3, and a null insertion line (uggt-4) (Fig. 3A and Fig. S7B and Fig. S8B) also showed elf18 insensitivity (Fig. 3 B and C) confirming that UGGT is required for EFR function. Like crt3 mutants, uggt mutants were unaltered in SGI and oxidative burst triggered by flg22 (Fig. 3 B and C). UGGT protein levels were unaltered in crt3–1 mutants, and CRT3 protein levels were unaltered in uggt mutants (Fig. S8 A and B).

Identification of ERD2b Mutant Alleles that Compromise EFR but Not FLS2 Signaling.

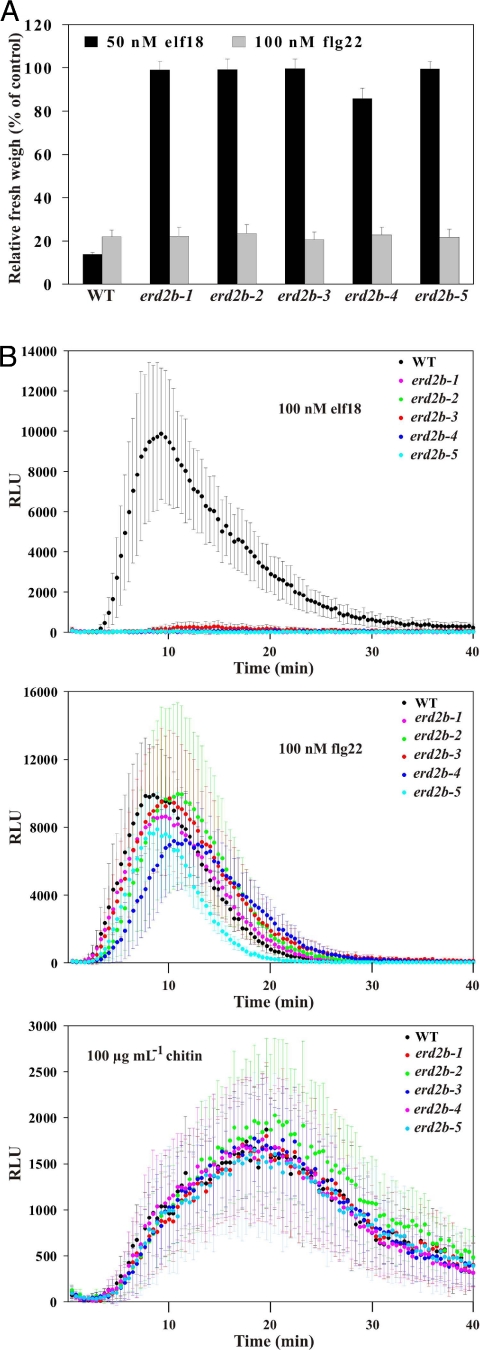

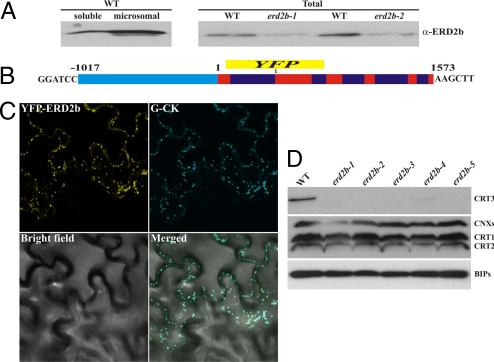

We investigated a third mutant, elfin5–3, and found that it contained a G to A transition (Fig. S9 B–D) in the gene At3g25040 (ERD2b) that corresponds to one of two Arabidopsis homologs (Fig. S10) of the yeast ER retention receptor ERD2 (31). We therefore renamed elfin5–3 as erd2b-1. ERD2 recognizes the C-terminal H/KDEL motif of certain soluble ER proteins to ensure their retrograde transport from the Golgi to the ER (32). While ERD2a was previously shown to be a functional ER retention receptor that complements the yeast erd2 mutant (33), the function of ERd2b is still unknown. Further analyses revealed four additional erd2b alleles in the elfin mutant collection (Fig. S9 B and C). All five erd2b alleles were strongly reduced in their responsiveness to elf18, but remained fully sensitive to flg22 and chitin (Fig. 4 A and B). Similarly to CRT3 and UGGT, ERD2b is therefore specifically required for EFR function.

Fig. 4.

ERD2b is required for elf18 responses. (A) Seedling growth of WT and erd2b mutants after treatments with 50 nM elf18 or 100 nM flg22. Treated and control seedlings were weighed 7 days after transfer to the peptide solution. Results shown are means ± SD (n = 8). (B) Oxidative burst induced in erd2b mutants by 100 nM elf18 and flg22 or 100 μg/mL chitin and measured in RLU in leaf discs. Results are means ± SD (n = 12). All experiments were independently performed at least three times with similar results.

ERD2b Is Golgi-Localized.

We raised a specific anti-ERD2b antibody and showed that ERD2b protein levels are higher in the microsomal fraction in comparison to the soluble fraction isolated from WT plants (Fig. 5A), suggesting that ERD2b is a membrane protein. In addition, erd2b-1 and erd2b-2 mutants exhibit substantially reduced ERD2b protein levels compared with the WT (Fig. 5A). ERD2a, the closest paralog of ERD2b, is widely used as a Golgi marker for protein localization studies, although it cycles continuously between the ER and the Golgi (34). To determine ERD2b sublocalization, we generated an SP-EYFP-ERD2b fusion construct driven by the ERD2b native promoter (Fig. 5B) and transiently coexpressed this construct in N. benthamiana with a control Golgi marker construct, G-CK (29). Both proteins colocalized (Fig. 5B), suggesting that ERD2b is a Golgi-localized membrane protein consistently to its potential function as a receptor for ER lumen proteins that escaped the ER.

Fig. 5.

ERD2b is Golgi-localized and is required for CRT3 accumulation. (A) Western blot analysis of ERD2b expression in WT (Left) or in erd2b mutants in comparison to WT (Right) with an anti-rabbit ERD2b antibody. (B) Schematic representation of ERD2b-YFP fusion construct driven by ERD2b native promoter (cyan). An YFP DNA fragment was introduced into the second exon (red), five nucleotides after the splicing acceptor site of the first intron (blue). (C) Subcellular localisation pattern of ERD2b. The YFP-ERD2b fusion proteins and the G-CK marker (29) were transiently coexpressed using Agrobacterium in N. benthamiana. (D) Proteins of leaf crude extracts were detected with specific antibodies against the ER chaperons including CRTs, CNXs, and BIPs.

ERD2b Is Required for CRT3 Protein Accumulation.

To test if ERD2b regulates CRT3 levels via retro-transport of CRT3 from the Golgi to the ER, we assessed CRT3 protein levels in the five erd2b alleles. Strikingly, all erd2b alleles show impaired CRT3 protein accumulation (Fig. 5D). This observation suggests that the elf18-insensitivity of the erd2b mutants is caused by CRT3 deficiency. Our previous data suggest that CRT1 and CRT2 might also contribute to EFR signaling, while calnexins are not required (Fig. S2 F and G). Interestingly, their protein levels were not affected in erd2b plants (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, we tested the levels of ER-resident luminal binding proteins BIPs belonging to the Hsp70 family of chaperones. Although BIP1 and BIP2 carry the HDEL motif (35), they accumulate in erd2b mutants to similar levels as in WT (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that CRT3 is a specific substrate of ERD2b.

Discussion

Despite the major contribution of PTI to plant innate immunity, our knowledge of the molecular events underlying PRR biogenesis, PAMP perception by PRRs, and downstream signaling is limited. We report here on three proteins (CRT3, UGGT, and ERD2b) that are required for the proper accumulation of the PRR EFR.

CRT3, together with CRT1 and CRT2, are the Arabidopsis orthologs of the mammalian soluble luminal lectin CRT involved in the folding of glycoproteins in the ER-QC (27, 36). Our finding that EFR does not accumulate in a crt3 null mutant, reveals that Arabidopsis CRT3 plays a similar function as its mammalian counterpart in ER-QC and that EFR is a client of CRT3 in vivo. Crt3 mutants were completely insensitive to elf18, while crt1 crt2 double mutants show reduced sensitivity to elf18. This shows that CRT1 and CRT2 are not able to complement for the loss of CRT3, but that CRT3 might complement for the loss of CRT1 and CRT2. We hypothesize that CRT proteins are part of an ER protein complex (37) in which CRT3 is required for EFR maturation but in which CRT3 can partially compensate for loss of CRT1 and CRT2. Although FLS2 function is not impaired, crt3 mutant plants are more susceptible than efr mutant plants to bacterial infection, suggesting that CRT3 may be required for the accumulation of additional, yet unknown PRRs mediating bacterial recognition, or conceivably, that it regulates other aspects of plant defense. Given that crt3 mutants are not impaired in FLS2-dependent responses, CRT3 is not required for BAK1 accumulation or function, a LRR-RK that positively regulates FLS2 function (38, 39). Our finding that uggt and crt3 mutants are insensitive to elf18 and that crt3 mutants do not accumulate any detectable levels of EFR proteins show that in the absence of CRT3 or UGGT, EFR protein is probably misfolded and therefore targeted to ERAD. EFR is therefore a client for CRT3/UGGT-mediated ER-QC.

The retention of soluble ER protein relies mainly of the recognition of a C-terminal sorting signal (i.e., HDEL and KDEL) by the ER-lumen protein-retaining receptor, ERD2 (32, 40). ERD2 binds the ER-escaped proteins and retrieves them back to the ER. The ERD2b protein is highly homologous to the yeast HDEL receptor and shows very high sequence similarity with ERD2a, which has been shown to complement the lethal phenotype of the yeast erd2 mutant (33). BLASTP analysis identified five additional, more distantly related, ERD2 paralogs (ERD2-like proteins, or ERPs) in Arabidopsis (Fig. S10). Interestingly, ERPs seem only present in plants (31), suggesting that they might play a role in a plant-specific biological process. Strikingly, ERD2a, ERD2b, and the ERPs show highly conserved gene structures (Fig. S10). In particular, exon lengths are invariant between ERD2a and ERD2b (Fig. S10), indicating very recent functional divergence. Given the presence of several ERD2 homologs in Arabidopsis, it was suggested that different retention signal (e.g., HDEL vs. KDEL) could be recognized by different ERD2 isoforms (31). However, our results show that the erd2b mutation specifically affects CRT3, but not CRT1 and CRT2, although they all carry a C-terminal HDEL signal, making this hypothesis unlikely. Our data, however, clearly demonstrate that ERD2b is essential for CRT3 accumulation, suggesting that the elf18-insensitive phenotype of erd2b mutants is due to lack of CRT3 protein accumulation that itself results in lack of EFR protein accumulation. This also suggests that CRT3 is a likely substrate for ERD2b. This is in agreement with the hypothesis that CRT might be degraded in a post-ER compartment after ER export if ERD2-mediated retrieval fails (41).

We have recently demonstrated the requirement of the soluble luminal proteins SDF2 and the Hsp40 ERdj3B for elf18 responses (24). SDF2 and ERdj3B form a complex with BiP in vivo, in which ERdj3B acts a bridge between SDF2 and BiP. Sdf2 mutants are strongly impaired in EFR protein accumulation, demonstrating that EFR biogenesis also requires the SDF2/ERdj3B/BiP complex, in addition to ER-QC mediated by CRT3 and UGGT. Interestingly, sdf2 or erdj3b mutants are not completely insensitive to elf18, suggesting that BiP retention is less critical than CRT-based ER-QC for EFR proper folding and protein accumulation. Because EFR contains two pairs of conserved Cys residues flanking the LRR ectodomain, it will be interesting to see if thiol reduction is also involved in EFR ER-QC. BiP and CRT exist in an abundant large complex in tobacco (37, 42). CRT3, SDF2, ERdj3B, BIP, and potentially UGGT may therefore exist in the same complex to regulate proper EFR folding. Such large chaperone complexes have been reported in mammals (43). So far, we failed to detect CRT3 or UGGT in the SDF2 immuno-complex. It is known that BiP-CRT heterodimers cannot be detected with BiP antibodies (37). Further work is therefore required to investigate the existence of such large complex.

Our studies provide a clear demonstration of a physiological requirement for the ER-QC in the control of transmembrane receptor in plants. The transmembrane LRR-RK BRI1 is the receptor for brassinosteroid class of plant hormone (44). Mutations in ER-QC components have been reported to specifically suppress the phenotype of the weak Arabidopsis bri1–9 and bri1–5 alleles by relaxing ER-QC, so that partially misfolded, but yet functional proteins can escape the ER and reach the plasma membrane (30, 45). We examined suppression of bri1–9 in crt3–1 mutants and found that like UGGT mutations (30), crt3–1 specifically suppresses the phenotype of bri1–9 but not bri1–301 that carries a mutation in the kinase domain (46) (Fig. S8). In all of these examples, the function of the WT BRI1 receptor was never affected by mutations in ER-QC components (30, 45), demonstrating that WT BRI1 is not a physiological substrate for ER-QC.

Together with another study (24), our findings reveal a subset of previously uncharacterized ER-QC components, including CRT3, UGGT, SDF2, the Hsp40 ERDj3B, and the Hsp70 BiPs, that are specifically required for the biogenesis of EFR and likely other PRRs in plant PTI. The specificity of mutations in these components clearly argues against a general defect in protein secretion. The existence of an ER chaperone complex involved in PTI mirrors the requirement of a cytosolic chaperone complex involving SGT1, RAR, Hsc70, and Hsp90 for the accumulation of several nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat-containing (NLR) proteins involved in plant ETI (47).

Why would EFR require ER quality control components that appear to be dispensable for FLS2 function? Although both FLS2 and EFR belong to the subfamily XII of LRR-RKs, they have clear differences in their protein structures, including different number and position of putative glycosylation sites (5, 6). We speculate that since EFR is only found in the Brassicaceae (6) whereas FLS2 has been identified in several dicots and monocots (5, 48–50), EFR may have evolved more recently than FLS2, and thus its amino acid sequence is less capable of folding properly in the absence of these components. It is conceivable that evolution of recognition proteins may result in proteins that detect novel ligands but that have not been selected for high protein stability and thus require extra “buffering” (51). Regardless of this speculation, additional defense components must depend on CRT3 function, since crt3 mutants are more susceptible to bacteria than efr mutants. Thus, the ER-QC system is likely to be required for the function of additional pattern recognition receptors and/or defense components whose identity will be interesting to investigate in future experiments. The molecular mechanisms underlying the differential requirement of EFR and FLS2 for ER-QC components will need to be identified in the future.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions.

Arabidopsis plant growth conditions were described in ref. 52 with the exception of germination medium (Murashige-Skoog medium containing 1% sucrose and 1% agar). N. benthamiana plants used for the transient expression assay were grown as one plant per pot at 20–23 °C with an 8-h photoperiod for 5–6 weeks. The isolation of elfin mutants was performed as described in Reference 24.

Bioassays and Infections.

Assays for seedling growth inhibition, oxidative burst, ethylene evolution, and protein kinase activity were performed as described (6, 53–56). Spray inoculations on Arabidopsis leaves were performed as described in ref. 55 with a bacterial suspension at OD600 = 0.02, plants were covered during the whole experiment and bacteria extracted at 3 days postinoculation (dpi).

CRT3 and ERD2b Protein Detection.

Rabbit antibodies raised against the CRT3-specific peptide TAGKWPGDPDNKG and the ERD2b-specific peptide YHKAVHRTYDREQDT were generated by Eurogentec and used to detect CRT3 and ERD2b in plant extracts as described in SI Methods.

Generation of Transgenic Plants.

Efr-1 and efr-1 crt3–1 mutant plants were transformed via the floral dipping method (57) with the epiGreenB(EFRp::EFR-eGFP-HA) construct (24). The BASTA-resistant transformants were further selected by PCR with GFP specific primers 5′-GTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGC-3′ and 5′-GATGTTGTGGCGGATCTTGAAG-3′.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Y. Saijo for his cooperation by revealing and sharing that elfin12–6 had a mutation in the UGGT locus and for suggesting primer sequences for defining additional elfin mutations at this locus; the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC), Institut National de Recherche Agronomique (INRA) Versailles, R. Boston, X. Dong, B. Kunkel, J. Li, G. Martin, and A. Vitale for providing materials; D. Alger and his team for excellent plant care, and J. Rathjen and R. Strasser for their useful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by ERA-NET Plant Genomics (J.D.G.J.) and by the Gatsby Foundation (C.Z., J.D.G.J.), Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/F021046/1 (C.Z.), an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship to C.Z. while in the Jones laboratory, and Swiss National Foundation Grant 31003A-120655 (to D.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0905532106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dangl JL, Jones JDG. Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature. 2001;411:826–833. doi: 10.1038/35081161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Host-microbe interactions: Shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zipfel C. Pattern-recognition receptors in plant innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T. FLS2: An LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell. 2000;5:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zipfel C, et al. Perception of the bacterial PAMP EF-Tu by the receptor EFR restricts Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Cell. 2006;125:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miya A, et al. CERK1, a LysM receptor kinase, is essential for chitin elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19613–19618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705147104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wan J, et al. A LysM receptor-like kinase plays a critical role in chitin signaling and fungal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:471–481. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimenez-Ibanez S, et al. AvrPtoB targets the LysM receptor kinase CERK1 to promote bacterial virulence on plants. Curr Biol. 2009;19:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinchilla D, Bauer Z, Regenass M, Boller T, Felix G. The Arabidopsis receptor kinase FLS2 binds flg22 and determines the specificity of flagellin perception. Plant Cell. 2006;18:465–476. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anelli T, Sitia R. Protein quality control in the early secretory pathway. EMBO J. 2008;27:315–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One step at a time: Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:944–957. doi: 10.1038/nrm2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitale A, Boston RS. Endoplasmic reticulum quality control and the unfolded protein response: Insights from plants. Traffic. 2008;9:1581–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck TM, Wright CM, Brodsky JL. The activities and function of molecular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:751–761. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin Y, Zhuang M, Hendershot LM. ERdj3, a luminal ER DNAJ homologue, binds directly to unfolded proteins in the mammalian ER: Identification of critical residues. Biochemistry. 2009;48:41–49. doi: 10.1021/bi8015923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin Y, Awad W, Petrova K, Hendershot LM. Regulated release of ERdj3 from unfolded proteins by BiP. EMBO J. 2008;27:2873–2882. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy P, Sparvoli A, Fagioli C, Fassina G, Sitia R. Formation of reversible disulfide bonds with the protein matrix of the endoplasmic reticulum correlates with the retention of unassembled Ig light chains. EMBO J. 1996;15:2077–2085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anelli T, et al. Thiol-mediated protein retention in the endoplasmic reticulum: The role of ERp44. EMBO J. 2003;22:5015–5022. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anelli T, et al. Sequential steps and checkpoints in the early exocytic compartment during secretory IgM biogenesis. EMBO J. 2007;26:4177–4188. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DB. Beyond lectins: The calnexin/calreticulin chaperone system of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:615–623. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danilczyk UG, Williams DB. The lectin chaperone calnexin utilizes polypeptide-based interactions to associate with many of its substrates in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25532–25540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caramelo JJ, Castro OA, de Prat-Gay G, Parodi AJ. The endoplasmic reticulum glucosyltransferase recognizes nearly native glycoprotein folding intermediates. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46280–46285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408404200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caramelo JJ, Castro OA, Alonso LG, de Prat-Gay G, Parodi AJ. UDP-Glc:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase recognizes structured and solvent accessible hydrophobic patches in molten globule-like folding intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:86–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262661199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nekrasov V, et al. Control of the pattern-recognition receptor EFR by an ER protein complex in plant immunity. EMBO J. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.262. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He P, et al. Specific bacterial suppressors of MAMP signaling upstream of MAPKKK in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Cell. 2006;125:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks D, Bender C, Kunkel B. The Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin coronatine promotes virulence by overcoming salicylic acid-dependent defences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persson S, et al. Phylogenetic analyses and expression studies reveal two distinct groups of calreticulin isoforms in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1385–1396. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denecke J, De Rycke R, Botterman J. Plant and mammalian sorting signals for protein retention in the endoplasmic reticulum contain a conserved epitope. EMBO J. 1992;11:2345–2355. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A. A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 2007;51:1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin H, Yan Z, Nam KH, Li J. Allele-specific suppression of a defective brassinosteroid receptor reveals a physiological role of UGGT in ER quality control. Mol Cell. 2007;26:821–830. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadlington JL, Denecke J. Sorting of soluble proteins in the secretory pathway of plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3:461–468. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semenza JC, Hardwick KG, Dean N, Pelham HR. ERD2, a yeast gene required for the receptor-mediated retrieval of luminal ER proteins from the secretory pathway. Cell. 1990;61:1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90698-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee HI, Gal S, Newman TC, Raikhel NV. The Arabidopsis endoplasmic reticulum retention receptor functions in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11433–11437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matheson LA, Hanton SL, Brandizzi F. Traffic between the plant endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus: To the Golgi and beyond. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noh SJ, Kwon CS, Oh DH, Moon JS, Chung WI. Expression of an evolutionarily distinct novel BiP gene during the unfolded protein response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene. 2003;311:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen A, et al. Functional characterization of Arabidopsis calreticulin1a: A key alleviator of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:912–924. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crofts AJ, Leborgne-Castel N, Pesca M, Vitale A, Denecke J. BiP and calreticulin form an abundant complex that is independent of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Plant Cell. 1998;10:813–823. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinchilla D, et al. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature. 2007;448:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heese A, et al. The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12217–12222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis MJ, Pelham HRB. Ligand-induced redistribution of a human KDEL receptor from the Golgi complex to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 1992;68:353–364. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90476-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pimpl P, Denecke J. ER retention of soluble proteins: Retrieval, retention, or both? Plant Cell. 2000;12:1517–1521. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denecke J, et al. The tobacco homolog of mammalian calreticulin is present in protein complexes in vivo. Plant Cell. 1995;7:391–406. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meunier L, Usherwood YK, Chung KT, Hendershot LM. A subset of chaperones and folding enzymes form multiprotein complexes in endoplasmic reticulum to bind nascent proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4456–4469. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vert G, Nemhauser JL, Geldner N, Hong F, Chory J. Molecular mechanisms of steroid hormone signaling in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:177–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong Z, Jin H, Tzfira T, Li J. Multiple mechanism-mediated retention of a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3418–3429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu W, Huang J, Li B, Li J, Wang Y. Is kinase activity essential for biological functions of BRI1? Cell Res. 2008;18:472–478. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shirasu K. The HSP90-SGT1 chaperone complex for NLR immune sensors. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:139–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altenbach D, Robatzek S. Pattern recognition receptors: from the cell surface to intracellular dynamics. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20:1031–1039. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-9-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takai R, Isogai A, Takayama S, Che F-S. Analysis of flagellin perception mediated by flg22 receptor OsFLS2 in rice. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2008;21:1635–1642. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-12-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hann DR, Rathjen JP. Early events in the pathogenicity of Pseudomonas syringae on Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J. 2007;49:607–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;417:618–624. doi: 10.1038/nature749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tedman-Jones JD, et al. Characterization of Arabidopsis mur3 mutations that result in constitutive activation of defence in petioles, but not leaves. Plant J. 2008;56:691–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Felix G, Duran JD, Volko S, Boller T. Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J. 1999;18:265–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kunze G, et al. The N terminus of bacterial elongation factor Tu elicits innate immunity in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3496–3507. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zipfel C, et al. Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature. 2004;428:764–767. doi: 10.1038/nature02485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meskiene I, et al. Stress-induced protein phosphatase 2C is a negative regulator of a mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18945–18952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.