Abstract

This short-term longitudinal study investigated whether maternal educational attainment, maternal employment status, and family income affect African-American children’s behavioral and cognitive functioning over time through their impacts on mothers’ psychological functioning and parenting efficacy in a sample of 100 poor and near-poor single black mothers and their 3- and 4-year-old focal children. Results indicate that education, working status, and earnings display statistically significant, negative, indirect relations with behavior problems and, with the exception of earnings, statistically significant, positive, indirect relationships with teacher-rated adaptive language skills over time. Findings suggest further that parenting efficacy may mediate the link between poor and near-poor single black mothers’ depressive symptoms and their preschoolers’ subsequent school adjustment. Implications of these findings for policy and program interventions are discussed.

Keywords: parenting efficacy, maternal depressive symptoms, low-wage employment, single mothers, child behavior problems, child adaptive language skills

Studies show that poverty and economic hardship have consistently negative effects on children’s socioemotional and cognitive functioning (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994; Mayer, 1997; McLoyd, 1998a, 1998b). These effects are especially robust for children who live in poverty persistently during the early childhood years (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Duncan et al., 1994). McLoyd (1990, 1998b, 2006) has argued that African-American children are more likely than others to experience persistent poverty and that parenting behavior mediates the links between economic hardship and black children’s development. Correspondingly, studies have found that parents’ economic stress and hardship are environmental factors that are associated with increased depressive symptoms, less efficacious parenting and, thereby, less optimal child outcomes (Brody & Flor, 1997; Conger, Conger, Elder, Lorenz, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1992; Elder, Eccles, Ardelt, & Lord, 1995; Jackson, Brooks-Gunn, Huang, & Glassman, 2000). It is not known, however, whether similar relationships would be found in a sample of single black mothers with young children who are current and former welfare recipients. This is important because the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 places strict time limits on welfare receipt and mandates that low-income recipients go to work (even mothers with very young children, low education, and low skills). Although single mothers have left welfare for work in large numbers, many still do not earn enough to raise their families out of poverty (Ellwood, 2000; Jackson & Scheines, 2005).

This short-term longitudinal investigation explored several individual and environmental factors that might be related to more efficacious parenting and, thereby, better child behavioral and cognitive outcomes in a sample of poor and near-poor single black mothers and their 3- and 4-year-old children who were current and former welfare recipients. In doing so, we looked also at the processes that might mediate the relations between family income and poor and near-poor black children’s academic adjustment in the early school years. This is important because studies have found that preschoolers’ behavior problems are predictors of later school adjustment and progress (Baydar, Brooks-Gunn, & Furstenberg, 1993; Byrd, Weitzman, & Auinger, 1997; Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, McCarton, & McCormic, 1994). Research demonstrates also that children who perform well as they begin their school careers tend to continue to do so, while children who have poor starts tend to continue to do poorly in school (Alexander & Entwisle, 1988; Ladd & Price, 1987). We focus on single black mothers in this study because they are disproportionately represented among the very poor and the welfare-dependent (Duncan, 1991; Wilson, 1987, 1996).

Background

The present study was guided by Bronfenbrenner’s (1988) person-process-context model that details a paradigm for assessing the impact on child developmental outcomes of personal characteristics of family members, family processes, and particular external environments. Consistent with this perspective, we identified maternal education, maternal employment status, and income as distal variables that might be associated indirectly with child behavior problems and adaptive language skills through their association with maternal depressive symptoms and parenting efficacy. In our conceptual model, depressive symptoms and parenting efficacy were classified as proximal variables because we predicted that they might be linked more directly to variations in children’s behavioral and cognitive functioning. According to Bronfenbrenner (1988; Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994), proximal processes are the mechanisms by which developmental potential is realized.

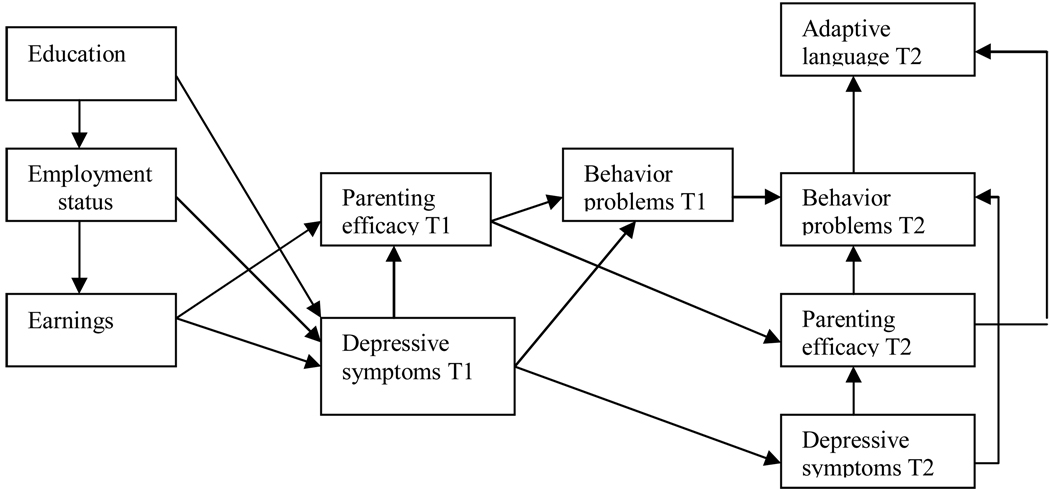

Figure 1 presents our conceptual model. The first panel of the model depicts the hypothesized relations among the distal variables. We proposed that higher maternal educational attainment would be associated with greater employment intensity (more working hours), which would be linked to higher earnings. While each of the distal variables was expected to be related indirectly to the child outcomes through their association with the proximal variables, earnings were hypothesized to be linked directly to mothers’ depressive symptoms at Time 1 and the latter to parenting efficacy also at Time 1. Parenting efficacy, in turn, was expected to be associated with behavior problems at Time 1. We expected these relations to be negative.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the influences of mothers’ education, employment status, and earnings on depressive symptoms, parenting efficacy, and child developmental outcomes.

The literature provides considerable support for the hypothesized relationships in our conceptual model. Among poor and near poor single black mothers, for example, studies have found that those with more education, are more likely to be employed, to work longer hours, and to earn higher incomes (Jackson, 2003; Jackson et al., 2000). Studies also have reported associations between single mothers’ earnings and depressive symptoms, and between depressive symptoms and deficits in parenting practices that are linked directly to children’s behavior (Conger, Conger, Elder, Lorenz, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1992; Downey & Coyne, 1990; Gelfand & Teti, 1990; Jackson, Bentler, Franke, 2006; McLoyd, 1990; Radke-Yarrow, 1998; Richters, 1992). Concerning the latter, our model specifies a direct link from depressive symptoms to parenting efficacy. In theory, lower educational attainment, less stable employment, and lower income might increase the risk for psychological distress (higher levels of depressive symptoms) which, in turn, might be associated with reduced beliefs in the efficacy of parent behavior (Bandura, 1995; Elder, Eccles, Ardelt, & Lord, 1995).

The second panel of our conceptual model presents the proposed links among the two proximal variables—parenting efficacy and depressive symptoms—at Time 1, their counterparts at Time 2, and the child outcomes; i.e., behavior problems at Time 1 and Time 2 and adaptive language skills as assessed by teachers at Time 2. More explicitly, we predicted that maternal depressive symptoms and parenting efficacy would serve as mediators connecting earlier steps in the model to children’s subsequent school adjustment. Stated differently, we expected that depressive symptoms would be associated with child behavior problems both directly and indirectly through their negative associations at Time 1 and Time 2 with parenting efficacy also at Time 1 and Time 2. We expected as well that more efficacious parenting would be associated directly not only with fewer behavior problems at Time 1 and Time 2, but also (at Time 2) with better adaptive language skills. These hypothesized relationships are supported by the work of Jackson and Huang (2000; see also Jackson, 2000) who reported links among single mothers’ depressive symptoms and self-efficacy and their preschool children’s behavior problems, and others (Baydar et al., 1993; Smith et al., 2000) who have reported links between parenting practices and children’s language development. Since higher scores on behavior problems scales in the preschool years, as assessed by parental report, have been found to predict behavior problems in the early school years (Richters, 1992; Richters & Pellegrini, 1989), our model hypothesizes that behavior problems at Time 1 would be a direct predictor of their counterparts at Time 2. We expected the latter to be associated negatively with the children’s verbal proficiency as assessed by teachers (see, for example, Baydar et al., 1993; Byrd et al., 1997; Klebanov et al., 1994). The analyses that follow present an empirical evaluation of the proposed model.

Method

Participants and Procedure

First interviewed between February and June of 2004, participants in this study consisted of 100 current and former single-mother welfare recipients (43 employed, 57 nonemployed)) and their preschool children at Time 1. The mothers resided in communities in Pittsburgh (11 zip codes) that were comprised predominantly of low-income black families. Recruited through the Allegheny County Assistance Office, the main welfare agency in Pittsburgh, the sample consisted of 134 randomly selected mothers with a 3- or 4-year-old child, who also were single, black, 18 years of age or older, and who were employed former welfare recipients or nonemployed current welfare recipients. Letters of solicitation, mailed by the Allegheny County Assistance Office, described the study as an ongoing survey on raising young children and family life. Prospective respondents were asked to indicate their interest in participating in the study by either calling the project office at the University of Pittsburgh or returning an enclosed participation form (giving their name, address, and telephone number) in a self-addressed, stamped envelope. Respondents were interviewed in their homes at Time 1 and, 1½ to 2 years later between October 2005 and January 2006, at Time 2. The final sample consisted of 100 mothers at Time 1 and 99 mothers at Time 2 (one mother died before the Time 2 interview), representing a response rate of 75%. For each interview, mothers completed a computer-administered questionnaire focusing on individual, family, and environmental characteristics. They were paid $75 at Time 1 and $150 at Time 2 for their time. In addition, 89 teachers (89.9% of those sent a mailed questionnaire) completed an assessment of the children’s adjustment in kindergarten at Time 2. Teachers were paid $25 for their time. For missing data, full bayesian multiple imputation was used. This method estimates equations predicting each variable with missing data from other variables. Through these equations, values drawn at random are substituted for the missing values (Rubin, 1987). Thus, even though one mother died before the Time-2 interview, the total number of cases included in the analyses was 100.

Measures

Corresponding to the model delineated in Figure 1, description of the measures proceeds across constructs from left to right. Except for employment status and family income, all variables included in the analyses are scales whose values represent the mean. When calculating the mean value on scales, items were reversed as necessary so that a higher score indicates more of the attribute named in the label. Alpha coefficients were obtained for scales with multiple items.

Educational attainment

Mothers’ education was indicated on a five-point scale (1 = grade school to 5 = BA/BS degree) that asked mothers to give the highest level of education they had completed. This scale was recoded to indicate years of education completed, from a low of 10 (some high school) to a high of 15 years (more than an AA, but less than a BA/BS, degree). All of the mothers had some education at the high school level; for example, 11% had completed 10 years, 24% had completed 12 years, 64% had completed 14 years, and 1% had completed 15 years of education. The mean level of completed education for the mothers in this study was 12.58 years (SD = 1.18), or some education beyond high school.

Employment status

At each interview mothers were asked whether they were employed (response options: yes/no) and, if so, how many hours they worked on average each week. In the present analyses, employment status was determined by mothers’ answers to these questions. Mothers worked up to 60 hours a week at Time 1; the mean for employed mothers was 30.35 hours (SD = 12.16). Average weekly working hours for the sample (aggregating nonemployed and employed mothers) was 13.05 hours (SD = 17.05).

Earnings

Earnings were indicated by mothers’ answer to the question, “How much in total are you earning now, before taxes and other deductions are taken out?” The range was from $0 (nonemployed) to $2140 a month; the mean was $447.11 (SD = $554.46).

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (20 items, alpha =.86 and .89 at Time 1 and Time 2, respectively) was used to measure depressive symptoms. Mothers were asked to indicate on a 4-point scale (0 = less than once a day to 3 = most or all of the time) how often during the past week they felt depressed, lonely, sad, unusually bothered by things, or that they could not get going. The CES-D is not intended as a measure of clinical depression, but groups with scores of 16 or above are considered to be at risk for depression (Radloff, 1977). In the present study, the mean was 14.62 (SD = 9.09) at Time 1 and 15.18 (SD = 9.96) at Time 2.

Parenting efficacy

A 34-item scale (alpha = .89 and .91 at Time 1 and Time 2, respectively) developed by Duke, Allen, and Halverson (1996), was used to assess parenting efficacy. Mothers were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = always) the extent to which statements such as the following applied to them as parents: “I cope well with the stresses and frustrations of parenthood;” “I am able to teach my child the things that will help him/her in life;” “I am good at showing my children that I love them;” “I feel that I have the right amount of control over my child’s behavior.” The mean was 3.34 (SD = 0.30) at Time 1 and 3.33 (SD = 0.33) at Time 2.

Child problem behaviors

Child problem behaviors (26 items, alpha = .83 and .95 at Time 1 and Time 2, respectively) were assessed by asking mothers to indicate on a 3- point scale (developed by Peterson and Zill, 1986) from 1 (very much like my child) to 3 (not at all like my child) the extent to which statements such as the following described their child’s behavior during the last three months: “tends to fight, hit, take toys when playing with other children,” “is disobedient at school or with child care providers,” “bullies or is cruel or mean to others.” The means were 1.58 (SD = 0.25) at Time 1 and 1.62 (SD = 0.28) at Time 2.

Adaptive language skills

The Adaptive Language Inventory (8 items, alpha = .94) was used to assess adaptive language skills. Teachers were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale from 1 (well below average) to 5 (well above average) the extent to which statements such as the following described the child’s verbal ability: “recalls and communicates personal experiences to peers in a logical way,” “recalls and communicates the essence of a story or other sequential material which has been heard or read in school,” “responds to questions asked in a thoughtful and logical way,” “is easily understood when talking to teachers” (Hogan, Scott, & Bauer, 1992).

Results

Descriptive Analyses

At Time 1, the average mother in this study was 25 years old; at time 2, she was 27; the focal children were 3 and 5 years old, respectively, at Time 1 and Time 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations between variables are shown in Table 1. In general, the results are in accord with our expectations. Mothers’ educational attainment was significantly positively correlated with employment status; that is, having more education was associated with working more hours, which in turn was associated positively with earnings and negatively with children’s behavior problems at both time points. Mothers’ depressive symptoms were correlated negatively with efficacious parenting and positively with behavior problems at Time 1 and Time 2, which were associated negatively with parenting efficacy. Children’s behavior problems at Time 2 were related to their adaptive language skills, as assessed by teachers. More precisely, children with more problem behaviors in kindergarten had lower scores on the Adaptive Language Inventory. In addition, better adaptive language skills were associated with having a mother who was employed, having a mother with higher educational attainment, and having a mother with higher earnings (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Variables

| Vs | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 12.58 | 1.18 | -- | |||||||||

| 2. | 13.05 | 17.05 | .30** | -- | ||||||||

| 3. | 447.11 | 554.46 | .28* | .62** | -- | |||||||

| 4. | 14.62 | 9.09 | −.01 | −.08 | −.21* | -- | ||||||

| 5. | 15.18 | 9.96 | −.08 | −.19* | −.28** | .54** | -- | |||||

| 6. | 3.34 | .30 | .18 | .05 | .25* | −.46** | −.24* | -- | ||||

| 7. | 3.33 | .33 | −.03 | .12 | .19* | −.32** | −.32** | .62** | -- | |||

| 8. | 1.58 | .25 | −.08 | −.21* | −.20* | .22* | .10 | −.42** | −.15 | -- | ||

| 9. | 1.63 | .29 | −.13 | −.22* | −.25* | .35** | .29* | −.34** | −.25* | .58** | -- | |

| 10. | 2.90 | .80 | .22* | .24* | .26** | .07 | −.02 | −.04 | −.14 | −.16 | .32** | -- |

Note. Variables (Vs) are: 1 = mothers’ education, 2 = employment status, 3 = earnings, 4 = depressive symptoms T1, 5 = depressive symptoms T2, 6 = parenting efficacy T1, 7 = parenting efficacy T2, 8 = behavior problems T1, 9 = behavior problems T2, 10 = adaptive language skills.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Model Estimation

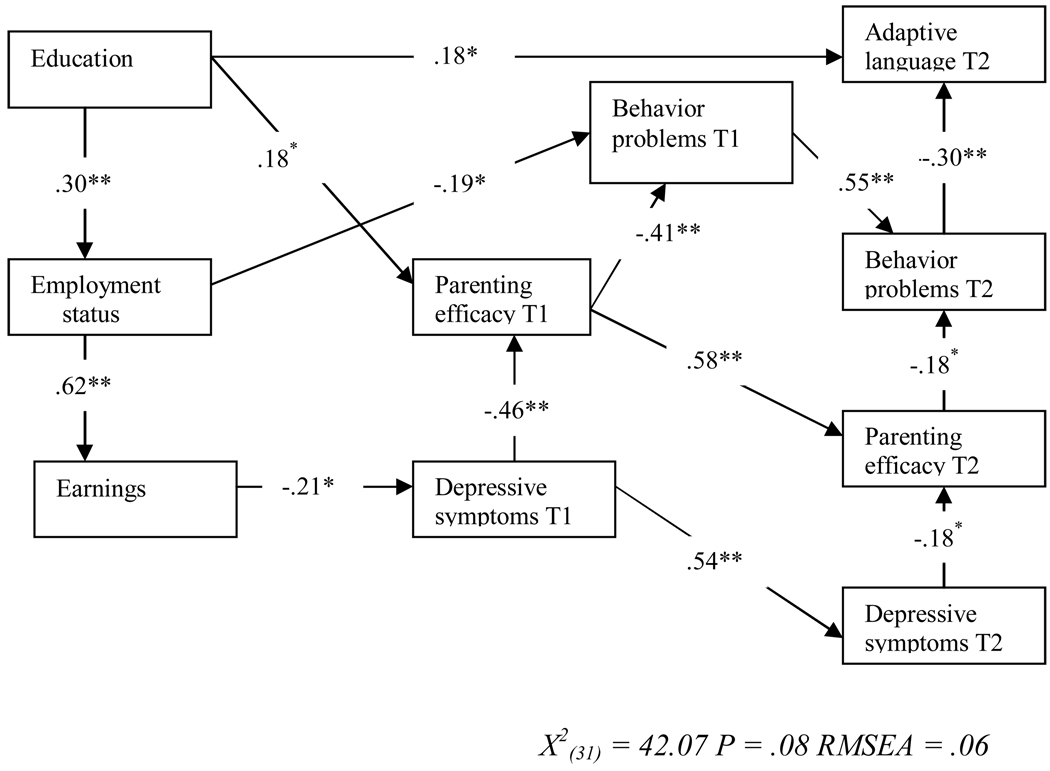

Maximum likelihood results are reported. Paths that were nonsignificant were dropped. Since direction is predicted in our model, we used one-tailed significance tests. Despite the modest size of our sample (N = 100), the model with 31 degrees of freedom produced a chi-square of 42.07 (p = .08), as well as a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of .06, indicating a good fit to the data.

The model depicted in Figure 2 provides the standardized parameter estimates representing beta weights. The path between mothers’ educational attainment and employment status is consistent with the hypothesized effect, indicating that education is associated positively with level of employment (Beta = .30, p < .01), which in turn exhibits the expected positive relationship to earnings (Beta = .62, p < .01). With regard to depressive symptoms at Time 1, earnings display a negative association (Beta = −.21, p < .05). In addition, depressive symptoms at Time 1 are associated positively with their counterpart at Time 2 (Beta = .54, p < .01), both of which have the expected negative relationships, respectively, to parenting efficacy at Time 1 (Beta = −.46, p < .01) and parenting efficacy at Time 2 (Beta = −.18, p < .05). Likewise, parenting efficacy at Time 1 and Time 2 are associated positively (Beta = .58, p < .01) and each, in turn, displays the expected negative relationships, respectively, to behavior problems at Time 1 (Beta = −.41, p < .01) and behavior problems at Time 2 (Beta = −.18, p < .05). Mothers’ employment status is related indirectly to depressive symptoms at Time 1 and Time 2 at p < .05, while earnings are associated indirectly with parenting efficacy and behavior problems, also at p < .05. The directions of these associations are consistent with the theoretical expectations; that is, employment status is related negatively to depressive symptoms and positively to parenting efficacy; while earnings are related positively to parenting efficacy and negatively to behavior problems (see Table 2).1

Figure 2.

Observed model of the influences of mothers’ education, employment status, and earnings on depressive symptoms, parenting efficacy, and child developmental outcomes. (*p < .05. **p < .01.)

Table 2.

Decomposition of Effects in Path Model

| Predictor | Dependent Variable | Total Effect |

Total Effect |

Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers’ education | Employment status | .30** | .30** | -- |

| Earnings | .19** | -- | .19** | |

| Depressive symptoms T1 | −.04* | -- | −.04* | |

| Depressive symptoms T2 | -- | -- | -- | |

| Parenting efficacy T1 | .20* | .18* | .02* | |

| Parenting efficacy T2 | .12* | -- | .12* | |

| Problem behaviors T1 | −.14** | -- | −.14** | |

| Problem behaviors T2 | −.10* | -- | −.10* | |

| Adaptive language | .21* | .18* | .03* | |

| Employment status | Employment status | .62** | .62 ** | -- |

| Depressive symptoms T1 | −.13* | -- | −.13* | |

| Depressive symptoms T2 | −.07* | -- | −.07* | |

| Parenting efficacy T1 | .06* | -- | .06* | |

| Parenting efficacy T2 | .05* | -- | .05* | |

| Problem behaviors T1 | −.21* | −.19* | −.02* | |

| Problem behaviors T2 | −.12* | -- | −.12* | |

| Adaptive language | .04* | -- | .04* | |

| Earnings | Depressive symptoms T1 | −.21* | −.21* | -- |

| Depressive symptoms T2 | −.11* | -- | −.11* | |

| Parenting efficacy T1 | .10* | -- | .10* | |

| Parenting efficacy T2 | .08* | -- | .08* | |

| Problem behaviors T1 | −.04* | -- | −.04* | |

| Problem behaviors T2 | −.04* | -- | −.04* | |

| Adaptive language | -- | -- | -- | |

| Depressive symptoms T1 | Depressive symptoms T2 | .54** | .54** | -- |

| Parenting efficacy T1 | −.46** | −.46** | -- | |

| Parenting efficacy T2 | −.37** | -- | −.37** | |

| Problem behaviors T1 | .19** | -- | .19** | |

| Problem behaviors T2 | .17** | -- | .17** | |

| Adaptive language | −.05* | -- | −.05* | |

| Depressive symptoms T2 | Parenting efficacy T1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Parenting efficacy T2 | −.18* | −.18* | -- | |

| Behavior problems T1 | -- | -- | -- | |

| Behavior problems T2 | -- | -- | -- | |

| Adaptive language | -- | -- | -- | |

| Parenting efficacy T1 | Parenting efficacy T2 | .58** | .58** | -- |

| Problem behaviors T1 | −.41** | −.41** | -- | |

| Problem behaviors T2 | −.33** | -- | −.33** | |

| Adaptive language | .10** | -- | .10** | |

| Parenting efficacy T2 | Problem behaviors T1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Problem behaviors T2 | −.18* | −.18* | -- | |

| Adaptive language | .05* | -- | .05* | |

| Problem behaviors T1 | Problem behaviors T2 | .55** | .55** | -- |

| Adaptive language | −.17** | -- | −.17** | |

| Problem behaviors T2 | Adaptive language | −.30** | −.30** | -- |

p < .05.

p < .01.

-- = nonsignificant.

Concerning the Time-2 child outcomes, the distal variables in our model—mothers’ educational attainment, employment status, and earnings—were expected to be associated indirectly (rather than directly) with child behavior problems and adaptive language skills through their relationships with the proximal variables; i.e., depressive symptoms and parenting efficacy, which were expected to be linked more directly to variations in children’s behavioral and cognitive functioning. Figure 2 and Table 2 show that while mothers’ educational attainment is related directly to adaptive language skills (Beta = .18, p < .05), its relationship to child behavior problems at Time 2 is indirect (Beta = −.10, p < .05) and transmitted through its associations with parenting efficacy at Time 1 and Time 2. Employment status and earnings display similar relationships; i.e., the former is related negatively and indirectly at p < .05 to behavior problems and positively and indirectly at p < .05 to adaptive language skills; the latter, negatively and indirectly to behavior problems, also at p < .05.

Insofar as the proximal variables are concerned, our conceptual models shows direct effects from parenting efficacy at Time 2 to adaptive language skills and from depressive symptoms at Time 1 and Time 2 to the corresponding parenting efficacy variables. Our observed model indicates that the beneficial effects of parenting efficacy at Time 1 and Time 2 on adaptive language skills appear to be transmitted via their mitigating effects on behavior problems, rather than directly as expected. In short, as depicted in Table 2, parenting efficacy at Time 1 exhibits a statistically significant, positive, indirect relationship with adaptive language skills p < .01; at Time 2, the corresponding effect is significant p < .05. Mothers’ mean parenting-efficacy scores at Time 1 and Time 2 were comparable (see Table 1). Thus, parenting efficacy at Time 1 was quite important with respect to its counterpart at Time 2; i.e., the former was a predictor of the latter (see Figure 2).

While direct and negative relationships were expected between depressive symptoms and behavior problems at Time 1 and Time 2, the effects of these variables on Time-2 behavior problems appear to be transmitted indirectly through the extenuating effects of depressive symptoms at Time 1 (both direct and indirect) on parenting efficacy at both time points. More explicitly, mothers higher in depressive symptoms at Time 1 appear to be less efficacious parents both contemporaneously and over time and, correspondingly, to have children with more behavior problems. Likewise, the indirect associations between depressive symptoms at Time 1 and both Time-2 child outcomes transmitted through parenting efficacy are in the predicted directions—negative for adaptive language and positive for behavior problems—and statistically significant at p < .05 and p < .01, respectively. Depressive symptoms at Time 2 display no such statistically significant relationships with the child outcomes at Time 2, suggesting that depressive symptoms early on were more important. It is worthy of note that mothers in this study were at slightly greater risk for depression at Time 2 than Time 1 (see Table 1), and the latter predicted the former (see Figure 2).

Discussion

In this short-term longitudinal investigation, we sought empirical support for a conceptual model of individual and environmental factors that might be related to more efficacious parenting and, thereby, better child behavioral and cognitive outcomes. In particular, we were interested in the processes that might mediate the relations between family income early on and poor and near-poor black children’s academic adjustment in the early school years. In the main, our model was supported. If further corroborated by longitudinal research with larger and more representative samples, our findings have implications for the identification of promising targets for program and policy interventions that might enhance parenting efficacy among poor and near-poor single black parents making the transition from welfare to work. Studies have found that it is possible to influence parenting behavior in such families (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005).

For the children in this study, mothers’ employment and earnings at Time 1 were associated indirectly with child behavior problems at Time 1 and Time 2 and language skills at Time 2 through their effects on mothers’ psychological and parenting functioning. As such, our findings suggest that depressive symptoms and parenting efficacy might mediate the relations between family income early on and poor and near-poor black children’s social and academic adjustment. They suggest, as well, that higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms in the context of more efficacious parenting might be less noxious for children; or, stated differently, parenting efficacy may be a mediator of the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms and preschoolers’ subsequent school adjustment. These results are consistent with studies that have documented the relationship of family economic circumstances to children’s socioemotional competence and cognitive abilities (see, for example, Baydar et al., 1993; Hart & Risley, 1995; Smith et al., 2000) and those that have reported relationships among parental psychological functioning, family processes, and child outcomes (see, for example, Brody & Flor, 1997; Conger et al., 1992; Elder et al., 1995; McLoyd, 1990).

We do not have an answer for why depressive symptoms at Time 1 were more important than their counterparts at Time 2 in this study. What is apparent is that parenting efficacy may serve an arbitrating function in the relation between maternal depressive symptoms early on and poor children’s socioemotional and cognitive development.

Elder and his colleagues (Elder et al., 1995) have argued that efficacious parents, including those heading black single-parent households, organize and arrange their children’s social environments in ways that promote better developmental outcomes. Our findings are consistent with this notion. As such, the indirect and positive link between earnings and efficacious parenting, if valid, suggests that policies which might bring single mothers with young children—especially those employed in low-wage jobs—out of poverty (either through supplemental assistance, raising the minimum wage, or tax relief) are worth consideration.

Moreover, the direct and positive association between mothers’ educational attainment and children’s adaptive language skills together with the indirect associations between higher educational attainment and, respectively, higher earnings, increased parenting efficacy, and fewer child behavior problems (again, if valid) suggest policy interventions making educational continuation beyond high school a viable option for welfare recipients. Consonant with other studies of poor and near-poor single black mothers (see, for example, Jackson et al., 2006), the average mother in this study had some education beyond high school and earned less than $500 a month. It is plausible that more educated mothers might be more likely than their less educated counterparts to provide an intellectually stimulating environment that develops children’s cognitive abilities (see, for example, Garrett, Ng’andu, Ferron, 1994; Hill & O’Neill, 1994; Jackson, 2003). Allowing single-mother welfare recipients who wish to extend their education beyond high school (including college) to do so in lieu of getting a job (“first”2) would be consistent with research findings linking higher maternal educational attainment to beneficial developmental outcomes for children. It also would be an investment in better and more meaningful employment opportunities over time for current and former welfare recipients.

Nevertheless, as with all studies, the present investigation is limited in several ways. First, the sample is relatively small and the mothers were residing in Pittsburgh. Further research with additional samples from other cities is needed to explore more fully these very important issues. Second, although we used longitudinal data, causal inferences about the observed relations among the distal and proximal variables vis-à-vis the child behavioral and cognitive outcomes investigated would be inappropriate. These analyses can only demonstrate that the directional paths we have proposed and observed are feasible. Third, our measures for the most part relied on parent reports. However, it is important that the children’s adaptive language skills at Time 2 were based on teacher ratings. Despite this, we acknowledge that objective reports of our constructs would have removed the potential for shared error variance.

Finally, although random selection is a key strength of our analyses, the size of the sample may belie what we argue here vis-à-vis the implications of our findings. The viability of our observed model should be tested with replicated studies across cities. Still, these data are unique in that they were collected from a group of single mothers who are of special interest for two principal reasons: single black mothers are disproportionately represented among the very poor and the welfare-dependent (Duncan, 1991; Wilson, 1987, 1996), and little is known about individual differences with respect to parenting, employment, and child outcomes in this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was assisted by a grant to the first author from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Center on Minority Health Disparities (#5 R21 MH066846-02).

Footnotes

Total and indirect (mediated) effects are tested via the effect of decomposition provided by the program used in estimating the model. Standardized estimates and t values are provided for both the total and indirect effects postulated by the model (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1996). The presence of a statistically significant indirect effect consistent with the theoretical expectation constitutes evidence of a fully or partially mediated effect. It should be noted that we do not use the Baron and Kenny (1986) approach to mediation. Rather, we employ structural equation modeling and, as such, mediated effects are understood in the following sense: Does a variable serving as an intervening variable transmit some of the “causal” effects of prior variables onto subsequent ones? For example, an effect constitutes mediation in our analyses if the product of the paths from A to B and B to C is significantly different from 0. If so, then B is considered to be a mediator.

The “work first” emphasis of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 which mandates a 5-year, lifetime, limit on welfare receipt presumes that most mothers who receive welfare benefits are employable and that the jobs they are able to get will pay a living wage.

Contributor Information

Aurora P. Jackson, Professor of Social Welfare, University of California, Los Angeles.

Jeong-Kyun Choi, Doctoral Student, Department of Social Welfare, School of Public Affairs, University of California, Los Angeles.

Peter M. Bentler, Professor of Psychology and Statistics, University of California, Los Angeles

References

- Alexander K, Entwisle D. Acheivement in the first two years of school: Patterns and processes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1988;53:2. Serial No. 218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Brooks-Gunn J, Furstenberg FF., Jr Early warning signs of functional literacy: Predictors in childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 1993;64:815–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Chou C. Practical issues in structural modeling. In: Long JS, editor. Common problems/ proper solutions: Avoiding errors in quantitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 161–192. [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Jodorkovsky R. Parenting stress and family functioning as predictors of pediatric contacts and behavior problems among toddlers. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1994;15:198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal psychological functioning, family processes, and child adjustment in rural, single-parent, African American families. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1000–1011. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Interacting systems in human development. Research paradigms: Present and future. In: Bolger N, Caspi A, Downey G, Moorehouse M, editors. Persons in context: Developmental processes. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1988. pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review. 1994;101:568–586. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Markman LB. The contribution of parenting to ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness. Future of Children. 2005;15:139–168. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom BL. Parental sensitivity to infants and toddlers in dual-earner and single-earner families. Nursing Research. 1998;47:162–170. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd RS, Weitzman M, Auinger P. Increased behavior problems associated with delayed school entry and delayed school progress. Pediatrics. 1997;100:654–661. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.4.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz RO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Litman C. Effects of maternal employment on maternal and two-year-old child behavior. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke HP, Allen KA, Halverson CF. A new scale for measuring parents’ feelings of confidence and competence: The Parenting Self-Efficacy Scale. Athens: University of Georgia; 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G. The economic environment of childhood. In: Huston A, editor. Children in poverty: Child development and public policy. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early-childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65:296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Jr, Eccles JS, Ardelt M, Lord S. Inner-city parents under economic pressure: Perspectives on the strategies of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:771–784. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood D. Anti-poverty policy for families in the next century: From welfare to work and worries. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2000;14:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Garett P, Ng’andu, Ferron J. Poverty experiences of young children and the quality of their home environments. Child Development. 1994;64:331–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DM, Teti DM. The effects of maternal depression on children. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:329–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore: Brookes; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey AM, Pavetti LA. Turning job finders into job keepers: The challenge of sustaining employment. The Future of Children. 1997;7:407–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MA, O’Neill Family endowments and the achievement of young children with special reference to the underclass. Journal of Human Resources. 1994;29:1064–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan AC, Scott KG, Bauer CR. The adaptive social behavior inventory (ASBI): A new assessment of social competence in high-risk three year olds. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1992;10:230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP. Maternal self-efficacy and children’s influence on stress and parenting among single black mothers in poverty. Family Issues. 2000;21:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP. The effects of family and neighborhood characteristics on the behavioral and cognitive development of poor black children: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32:175–186. doi: 10.1023/a:1025615427939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP, Bentler PM, Franke TM. Employment and parenting among current and former welfare recipients. Journal of Social Service Research. 2006;33:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP, Brooks-Gunn J, Huang C, Glassman M. Single mothers in low-wage jobs: Financial strain, parenting, and preschoolers’ outcomes. Child Development. 2000;71:14–23. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP, Huang CC. Parenting stress and behavior among single mothers of preschoolers: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Social Service Research. 2000;26:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP, Scheines R. Single mothers’ self-efficacy, parenting in the home environment, and children’s development in a two-wave study. Social Work Research. 2005;29:7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8, User’s reference guide. Chilcago: Scientific Software International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J, McCarton C, McCormick MC. The contribution of neighborhood and family income to developmental test scores over the first three years of life. Child Development. 1998;69:1420–1436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J, McCormick MC. Classroom behavior of very low birth weight elementary school children. Pediatrics. 1994;94:700–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G, Price J. Predicting children’s social and school adjustment following transition from preschool to kindergarten. Child Development. 1987;58:1168–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S. What money can’t buy: Family income and children’s life chances. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. Children in poverty: Development, public policy, and practice. In: Siegel IE, Renninger KA, editors. Handbook of child psychology. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 1998a. pp. 135–210. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998b;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The legacy of Child Development’s 1990 Special Issue on Minority Children: An editorial retrospective. Child Development. 2006;77:1142–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Zill N. Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Radke-Yarrow M. Children of depressed mothers. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE. Depressed mothers as informants about their children: A critical review of the evidence for distortion. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:485–499. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richters J, Pellegrini D. Depressed mothers’ judgements about their children: An examination of the depression-distortion hypothesis. Child Development. 1989;60:1068–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in survey. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Landry SH, Swank PR. Does the content of mothers’ verbal stimulation explain differences in children’s development of verbal and nonverbal cognitive skills? Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. New York: Knopf; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe B, Hill S. The effect of health on the work effort of single mothers. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30:42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslow MH, Pederson FA, Suwalsky JTD, Cain RL, Fivel M. The early resumption of employment by mothers: Implications for parent-infant interaction. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1985;6:1–16. [Google Scholar]