Abstract

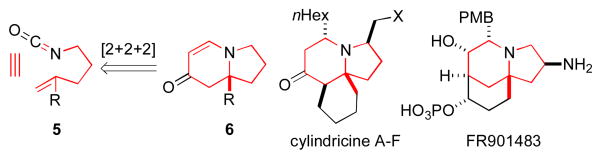

An enantioselective synthesis of indolizidines bearing quaternary substituted stereocenters by way of a rhodium catalyzed [2+2+2] cycloaddition of substituted alkenyl isocyanates and terminal alkynes is described. The reaction provides lactam products using aliphatic alkynes, while aryl alkynes give rise to vinylogous amide products. Through modification of the phosphoramidite ligand, high levels of enantioselectivity, regioselectivity, and product selectivity are obtained for both products.

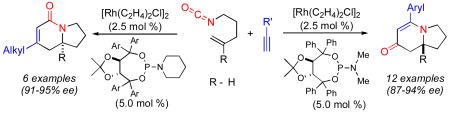

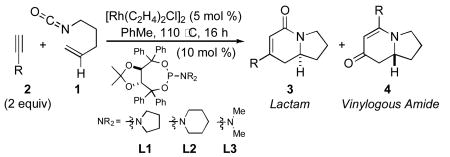

Transition-metal-catalyzed [m+n+o] type cycloaddition reactions have proven to be efficient methods for the construction of complex polycyclic carbocycles and heterocycles.1 Of the functional groups that participate in these cycloadditions, isocyanates2 have played an increasingly important role due to their reactivity and embedded nitrogen-containing functionality.3 Indeed, the [2+2+2] cycloaddition of isocyanates with diynes to generate 2-pyridones has been demonstrated with Co(I), Ru(II), Ni(0), and Rh(I).4 Our group has recently demonstrated5 that the [2+2+2] cycloaddition of unsubstituted pentenyl isocyanate 1 with alkynes 2 could be accomplished in the presence of a rhodium(I) catalyst to form either lactam 3 or vinylogous amide 4 – the result of an apparent CO migration.6 Moreover, the reaction of 1 with terminal aryl alkynes in the presence of phosphoramidite ligand L1,7 affords vinylogous amide 4 products with high levels of enantioenrichment (up to 94% ee) while reaction with terminal aliphatic alkynes in the presence of ligand L2 affords lactam products 3 with only moderate enantioenrichment (76-87% ee).5b

|

(1) |

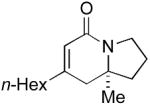

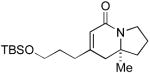

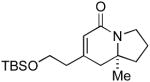

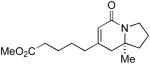

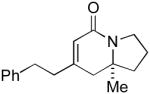

We envisioned that this reaction would provide an expedient entry into a variety of indolizidine and quinolizidine natural products.8 We further noted that a number of these natural products possess additional substitution at various positions around the core including carbon groups at the bridgehead position (a quaternary substituted stereocenter).9 Two specific examples of such natural products include the marine alkaloids cylindricines A-F10 and the immunosuppressant FR901483.11 We thus endeavored to extend this cycloaddition reaction to incorporate polysubstituted alkenes, in spite of considerable literature precedent which suggested that more substituted alkenes provide less stable alkene/metal complexes.12 For example, ethylene binds to Rh(I) 13 times stronger than propylene while isobutylene binds 200 times less strongly than propylene.13 Indeed, the substitution of disubstituted alkenes in place of terminal olefins in catalytic reactions is not trivial.14 In light of these potential problems, it is particularly notable that a Rh(I)·phosphoramidite catalyst system has proven to be very accommodating of 1,1-disubstituted alkenes as partners in this chemistry. The development of this transformation is described herein.

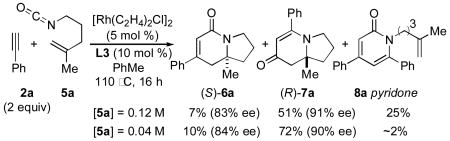

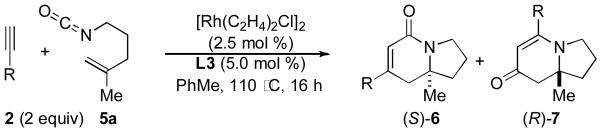

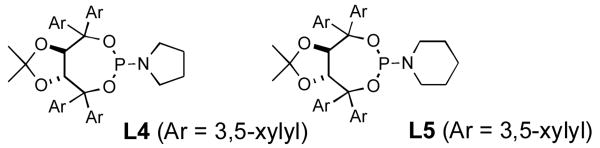

In preliminary tests, we were pleased to discover that the methyl substituted isocyanate 5a (0.12 M in toluene) reacts with phenylacetylene (2 eq) in the presence of [Rh(C2H4)2Cl]2 (5 mol %) and phosphoramidite L3 (10 mol %) to give a 1:8 mixture of lactam 6a and vinylogous amide 7a (58% combined yield) as single regioisomers with good enantioselectivities, eq 2. The major byproduct in this reaction was 2-pyridone 8a, the result of cycloaddition between the isocyanate and two equivalents of alkyne. Using more dilute conditions ([5a] = 0.04 M), the formation of pyridone 8a could be suppressed, leading to the desired cycloadducts as a 1:7 mixture of 6a:7a with similar ee's.

|

(2) |

The reaction was further optimized by lowering the rhodium dimer catalyst loading to 2.5 mol %, a change which results in only a minor decrease in yield (Table 1, entry 1). A series of terminal alkynes were subjected to reaction with isocyanate 5a using the optimized conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Alkyne Scope

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | products | 6:7a | yield (%) | ee (% of 6)b | ee (% of 7)b | |

|

||||||

| 1 | 6a (Ar = Ph) | 7a | 1:8 | 76 | 84 | 90 |

| 2 | 6b (Ar = 4-MeOC6H4) | 7b | < 1:20 | 80 | - | 91 |

| 3 | 6c (Ar = 4-BrC6H4) | 7c | 1:3 | 77 | 82 | 88d |

|

||||||

| 4 | 6dc | 7dc | 1:9 | 64 | - | 91 |

Product selectivity determined by 1H NMR of the unpurified mixture.

Determined by HPLC using a chiral stationary phase.

Alkyne and product E:Z = 97:3.

Absolute stereochemistry determined by X-ray.

Comparing the lactam:vinylogous amide (6:7) selectivity obtained with phenylacetylene 2a (1:8), p-methoxy-phenylacetylene 2b (<1:20) and p-bromo-phenylacetylene 2c (1:3), it is evident that electron rich alkynes favor formation of vinylogous amide products 7 while electron poor alkynes increase the formation of lactam products 6, a situation we had also noted in our work with terminal alkynes and pentenyl isocyanate.5b Unlike the product selectivity in entries 1-3, the yield (76-80%) and enantioselectivity (88-91% ee) remain relatively unchanged with shifting alkyne electronics. The reaction also proceeds smoothly with vinyl ether 2d to yield vinylogous amide product in good yield and excellent enantioselectivity (91% ee).15

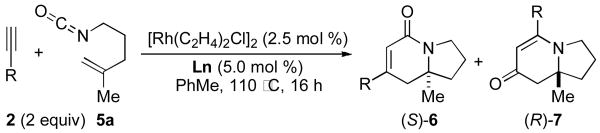

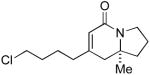

Terminal aliphatic alkynes also participate in the cycloaddition with isocyanate 5a, albeit with a reversal in product selectivity (Table 2). With 1-octyne 2e, a modest 2:1 ratio of lactam 6e (84% ee) and vinylogous amide 7e (71% ee) is obtained in 82% combined yield. Interestingly, phosphoramidite ligand L4 (a ligand with little effect on the reaction of phenylacetylene16) greatly improves the enantioselectivity in the reaction with 2e (entry 2). Further modification of the ligand led to phosphoramidite L5, which affords the lactam in good product selectivity (6.5:1) and enantioselectivity (91% ee). A variety of terminal aliphatic alkynes, including those bearing silyl ethers, an ester, and alkyl chloride (entries 4-6, 8), are tolerated under the optimized conditions (60-83% yield, 92-95% ee). The generally high enantioselectivity and product selectivity obtained with ligand L5 represents a marked improvement over the selectivity previously reported with L3.5b

Table 2.

Aliphatic Alkyne Scope

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | product | Ln | 6:7a | yield (%) | ee (% of 6)b |

| 1 |

6e 6e

|

L3 | 2:1 | 82 | 84 |

| 2 | 6e | L4 | 3:1 | 75 | 95 |

| 3 | 6e | L5 | 6.5:1 | 88 | 91 |

| 4 |

6f 6f

|

L5 | 9:1 | 70 | 95 |

| 5 |

6g 6g

|

L5 | 11.5:1 | 77 | 93 |

| 6 |

6h 6h

|

L5 | 8:1 | 83 | 93 |

| 7 |

6i 6i

|

L5 | 9.5:1 | 71 | 95 |

| 8 |

6j 6j

|

L5 | 8:1 | 60 | 92 |

| |||||

Product selectivity determined by 1H NMR of the unpurified mixture.

Determined by HPLC using a chiral stationary phase.

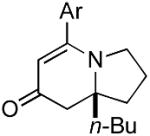

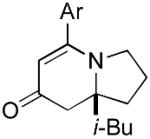

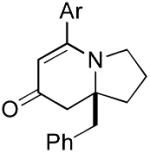

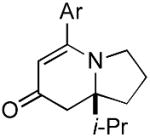

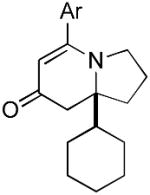

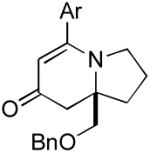

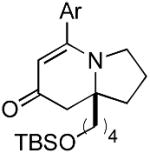

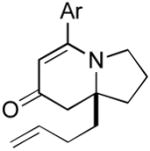

The range of alkenyl isocyanate substitution was also explored using p-methoxy-phenylacetylene 2b as the alkyne (Table 3). The ratio of lactam to vinylogous amide products obtained remains independent of the alkene substitution (<1:20 in all cases). The reaction proceeds in a consistent manner with alkyl substituents such as butyl, isobutyl, and benzyl (71-80% yield, 92-94% ee). As the steric size of the substituent is increased, as in the case with isopropyl and cyclohexyl isocyanates, an increase in pyridone byproduct and a corresponding decrease in vinylogous amide yield are observed (entries 4-5). We presume that the increased steric demand about the alkene decreases the rate of coordination and/or insertion of the alkene to the extent where intermolecular insertion of a second alkyne is competitive even under dilute conditions. Benzyl ethers 5g, silyl ethers 5h and terminal alkenes 5i17 are all tolerated under these reaction conditions (74-77% yield, 88-92% ee).

Table 3.

Alkenyl Substitution Scope

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yield (%) | ee (%)a |

| 1 |

9b 9b

|

71 | 90 |

| 2 |

9c 9c

|

75 | 94 |

| 3 |

9d 9d

|

80 | 92 |

| 4 |

9e 9e

|

50 | 89 |

| 5 |

9f 9f

|

19b | 87 |

| 6 |

9g 9g

|

77 | 92 |

| 7 |

9h 9h

|

74 | 88 |

| 8 |

9i 9i

|

75 | 91 |

Determined by HPLC using a chiral stationary phase.

Major product isolated is pyridone (48% yield).

We have shown that 1,1-disubstituted alkenes are competent partners in the Rh-catalyzed [2+2+2] cycloaddition reaction leading to the generation of tetrasubstituted carbinolamine stereocenters. We have also identified a new phosphoramidite ligand that provides improved product selectivity and enantioselectivity in the cycloaddition of aliphatic alkynes.18 Efforts aimed at understanding the subtle ligand effects and applications in total synthesis are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Indolizidines Bearing Quaternary Substituted Stereocenters

Acknowledgments

We thank NIGMS (GM080442), Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim and Johnson & Johnson for support. TR is a fellow of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and thanks the Monfort Family Foundation for a Monfort Professorship.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Aubert C, Buisine O, Malacria M. Chem Rev. 2002;102:813. doi: 10.1021/cr980054f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Murakami M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:718. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakamura I, Yamamoto Y. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2127. doi: 10.1021/cr020095i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gandon V, Aubert C, Malacria M. Chem Commun. 2006:2209. doi: 10.1039/b517696b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Witulski B, Alayrac C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:3281. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3281::AID-ANIE3281>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Tanaka K. Synlett. 2007:1977. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braunstein P, Nobel D. Chem Rev. 1989;89:1927. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Hoberg H, Hernandez E. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1985;24:961. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoberg H. J Organomet Chem. 1988;358:507. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hoberg H, Bärhausen D, Mynott R, Schroth G. J Organomet Chem. 1991;410:117. [Google Scholar]

- 4.With Co:; (a) Earl RA, Vollhardt KPC. J Org Chem. 1984;49:4786. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hong P, Yamazaki H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977:1333. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bonaga LVR, Zhang HC, Moretto AF, Ye H, Gauthier DA, Li J, Leo GC, Maryanoff BE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3473. doi: 10.1021/ja045001w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ru:; (d) Yamamoto Y, Takagishi H, Itoh K. Org Lett. 2001;3:2117. doi: 10.1021/ol016082t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yamamoto Y, Kinpara K, Saigoku T, Takagishi H, Okuda S, Nishiyama H, Itoh K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:605. doi: 10.1021/ja045694g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ni:; (f) Hoberg H, Oster BW. Synthesis. 1982:324. [Google Scholar]; (g) Duong HA, Cross MJ, Louie J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11438. doi: 10.1021/ja046477i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rh:; (h) Tanaka K, Wada A, Noguchi K. Org Lett. 2005;7:4737. doi: 10.1021/ol052041b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Yu RT, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2782. doi: 10.1021/ja057803c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu RT, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12370. doi: 10.1021/ja064868m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnhart RW, Bosnich B. Organometallics. 1995;14:4343. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanaka K, Fu GC. Chem Commun. 2002:684. doi: 10.1039/b200208f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Feringa BL. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:346. doi: 10.1021/ar990084k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alexakis A, Burton J, Vastra J, Benhaim C, Fournioux X, van den Heuvel A, Leveque J, Maze F, Rosset S. Eur J Org Chem. 2000:4011. [Google Scholar]; (c) Panella L, Feringa BL, de Vries JG, Minnaard AJ. Org Lett. 2005;7:4177. doi: 10.1021/ol051559c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Woodward AR, Burks HE, Chan LM, Morken JP. Org Lett. 2005;7:5505. doi: 10.1021/ol052312i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michael JP. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24:191. doi: 10.1039/b509525p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christoffers J, Baro A, editors. Quaternary Stereocenters. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinreb SM. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2531. doi: 10.1021/cr050069v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asymmetric syntheses:; (a) Snider BB, Lin H. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7778. [Google Scholar]; (b) Scheffler G, Seike H, Sorensen EJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:4593. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001215)39:24<4593::aid-anie4593>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ousmer M, Braun NA, Ciufolini MA. Org Lett. 2001;3:765. doi: 10.1021/ol015526i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Racemic syntheses:; (d) Maeng JH, Funk RL. Org Lett. 2001;3:1125. doi: 10.1021/ol015506g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kan T, Fujimoto T, Ieda S, Asoh Y, Kitaoka H, Fukuyama T. Org Lett. 2004;6:2729. doi: 10.1021/ol049074w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Brummond KM, Hong SP. J Org Chem. 2005;70:907. doi: 10.1021/jo0483567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolman CA. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:2780. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cramer R. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:4621. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For an example of the problem, see:; (a) Ohno H, Miyamura K, Mizutani T, Kadoh Y, Takeoka Y, Hamaguchi H, Tanaka T. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:3728. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For successful solutions, see:; (b) Evans PA, Lai KW, Sawyer JR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12466. doi: 10.1021/ja053123y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shibata T, Arai Y, Tahara YK. Org Lett. 2005;7:4955. doi: 10.1021/ol051876j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attempts at generating quinolizidine systems using homologous substituted isocyanates resulted in exclusive formation of pyridone.

- 16.With L4, 6a:7a (1:7) are obtained in 76% combined yield (83% and 90% ee respectively).

- 17.We have observed no evidence to suggest the terminal olefin participates in this reaction. Homologous systems were not examined.

- 18.Internal alkynes also participate in this cycloaddition reaction but provide higher selectivities using a different ligand. These studies are currently ongoing.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.