Abstract

The role of functional MRI (fMRI) in the presurgical evaluation of patients with intractable epilepsy is being increasingly recognized. Real-time fMRI is an easily performable diagnostic technique in the clinical setting. It has become a noninvasive alternative to intraoperative cortical stimulation and the Wada test for eloquent cortex mapping and language lateralization, respectively. Its role in predicting postsurgical memory outcome and in localizing the ictal activity is being recognized. This review article describes the biophysical basis of blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) fMRI and the methodology adopted, including the design, paradigms, the fMRI setup, and data analysis. Illustrative cases have been discussed, wherein the fMRI results influenced the seizure team's decisions with regard to diagnosis and therapy. Finally, the special issues involved in fMRI of epilepsy patients and the various challenges of clinical fMRI are detailed.

Keywords: Epilepsy, functional, MRI

Functional MRI is a technique that maps the physiological or metabolic consequences of altered electrical activity in the brain. In contrast to positron emission tomography (PET), a similar brain mapping technique and one that has been used for many years to study brain function, fMRI is not based on ionizing radiation and thus can be repeated as often as is necessary in patients or normal volunteers. Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) map the electrical activity in the brain. Although EEG and MEG have high temporal resolution (10-100 milliseconds), they suffer from poor spatial resolution (one to several centimeters). The blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) fMRI technique has a spatial resolution of a few millimeters and a temporal resolution of a few seconds.[1]

Biophysical Basis of BOLD fMRI

Neuronal stimulation leads to a local increase in energy and oxygen consumption in functional areas. The subsequent local hemodynamic changes transmitted via neurovascular coupling are measured by fMRI. The close coupling between regional changes in brain metabolism and regional cerebral blood flow (CBF), called ‘activation flow coupling’ (AFC), was originally described by Roy and Sherrington in 1890.[2] The BOLD technique depends on the difference in the magnetic properties between oxygenated (oxy-Hb) and deoxygenated (deoxy-Hb) hemoglobin. The ferrous iron on the heme moiety of deoxy-Hb was shown to be paramagnetic by Thulborn and colleagues in 1982.[3] Paramagnetic deoxy-Hb produces local field inhomogeneities in the measurable range of MRI, resulting in signal decrease in susceptibility-weighted MRI-sequences (T2*), whereas diamagnetic oxy-Hb does not interfere with the external magnetic field. Ogawa and coworkers working on a rat model at 7 Tesla showed that the oxygenation of blood has a measurable effect on the MRI signal.[4] Kwong et al, in 1992, demonstrated that brain activation in human subjects produced a local signal increase that could be used for functional brain imaging.[5] In the same year, several others reported similar findings.[6–8]

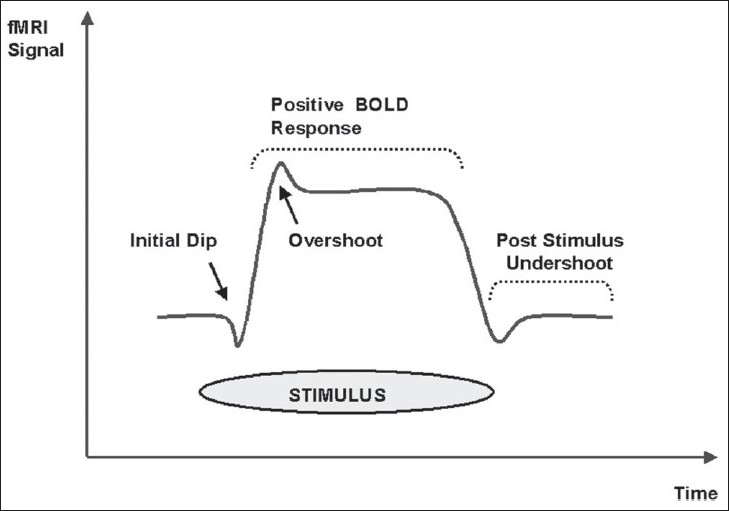

When the neurons are stimulated there is an increase in local oxygen consumption that results in an initial decrease of oxy-Hb and an increase in deoxy-Hb in the functional area. To provide the active neurons with oxygenated blood, perfusion in capillaries and draining veins is enhanced within several seconds. As a result of this process, the initial decrease of local oxy-Hb is equalized and then overcompensated.[9] The deoxy-Hb is progressively washed out. This causes a reduction of local field inhomogeneity and an increase of the BOLD signal in T2*W MRI images[10] [Figure 1]. Although the ‘initial dip’ corresponds to the neuronal activity both temporally and spatially, this is more difficult to measure in clinical settings.[11] Electrophysiologically, it is the local field potential that changes with an increase in the BOLD signal and not the neuronal firing rate.[12]

Figure 1.

BOLD signal shows initial dip and then a more prolonged ‘positive’ signal

Design of fMRI Experiments and Data Acquisition

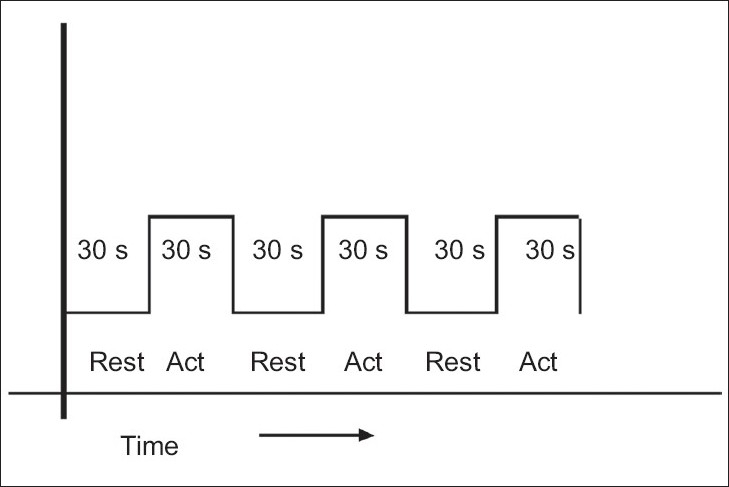

The most common imaging sequence used in fMRI studies is echoplanar imaging (EPI).[13] This is a very fast MRI imaging sequence, which can collect whole brain data within a few seconds. However, the spatial resolution is significantly lower than in anatomic MRI images. Also EPI images are sensitive to field inhomogeneities, leading to geometric distortion of the images in certain brain regions. In a typical fMRI experiment, a large set of images is acquired very quickly, while the patient or subject performs a task that shifts brain activity between two or more well-defined states (boxcar design) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Boxcar design: Rest and active conditions are repeated alternatively during the acquisition

The signal time course in each voxel of the slices and the time course of different tasks are correlated. This can identify voxels in brain that show statistically significant changes associated with the brain function under consideration.[1] Later these statistical maps (Z scores) are superimposed on a high-resolution anatomic image by using a coregistration technique for proper identification of the precise anatomic location of the origin of the signal. Although this appears complicated, most of this can now be done online using the real-time fMRI packages available in newer MRI machines.

Most of the clinical fMRI experiments use a boxcar or block design. It is the simplest and the most time-efficient approach for comparing brain response in different states. In this design, for relatively long periods (e.g., 30 s), a discrete cognitive or motor state is maintained (in the simplest form, two states: rest vs activity) and is alternated during scanning. Since this is not a physiological design (i.e., it is an artificial state), some tasks may not be suitable for this design.[1]

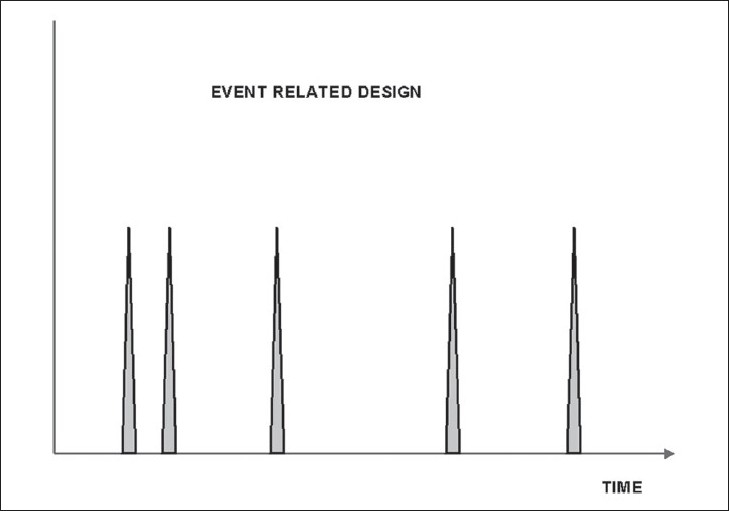

An alternative approach, which is more physiological, is an ‘event’-related paradigm [Figure 3], in which discrete stimuli are repeated at variable times while scanning is in progress. However, this design needs longer acquisition times and is statistically more difficult to analyze and, hence, is used less often in clinical practice.

Figure 3.

Event-related design: Stimuli repeated at variable intervals

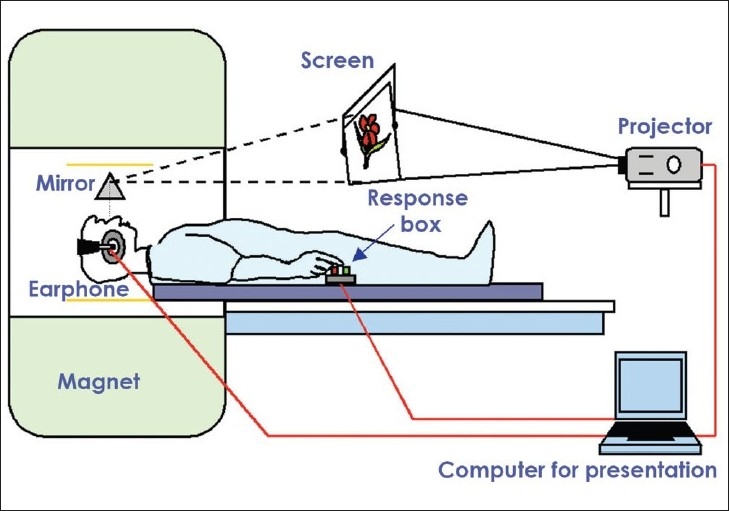

fMRI Setup

fMRI applications in research laboratories can have permanent test setups. Here the results need not be immediately available. In contrast, fMRI in clinical / hospital settings, needs custom-tailored hardware, software, imaging protocols, and data evaluation techniques. A real-time fMRI processing tool is useful so that the results are available immediately. In a clinical setting we have to examine patients with existing deficits, and subjects may include uncooperative or sedated patients and children. At our institute we have set up a patient-friendly audiovisual projection system with a response box and synchronization device (synchronizes the visual/auditory stimulation with the MRI pulse). Figure 4 illustrates the setup that we use for clinical studies.

Figure 4.

fMRI setup: Patient responds to the visual/auditory stimuli using the response box

fMRI Paradigms

By using optimized and standardized protocols, fMRI examinations can be integrated into routine MRI imaging without major problems. To investigate motor function, self-triggered movements are most commonly used. Motor cortex mapping is done using paradigms that include tongue movements as well as finger and toe movements, contralateral to the side of the lesion, to localize the motor homunculus in relation to the lesion. Bilateral finger movement can help in comparing the ipsilateral motor cortex with that on the opposite side. To keep the likelihood of motion artifacts to a minimum,[14,15] the following movement tasks are chosen: repetitive tongue movements, with closed mouth; opposition of fingers to thumb, with free choice of sequence; and repetitive flexion and extension of all five toes, without moving the ankle. Alternatively, in cases of mild paresis of the upper extremity, fist clenching/ releasing can be tested. The somatosensory functional areas can be studied by nonstandardized tactile stimuli (e.g., manual stroking of the hand by the examiner).[16]

Language functions are examined using various paradigms involving auditory or visual stimulation. A task commonly and easily performed in patients for the purpose of lateralization is the “verb generation task” (also called “verbal fluency task”). This task shows relatively consistent activation of the anterior language areas. Another task, the “semantic decision-making task”, demonstrates more widely distributed networks, including the anterior and posterior language areas.[17] The "visual stimulation task" is performed by showing checkerboards during the active period and a blank screen during the rest period.

Data Analysis

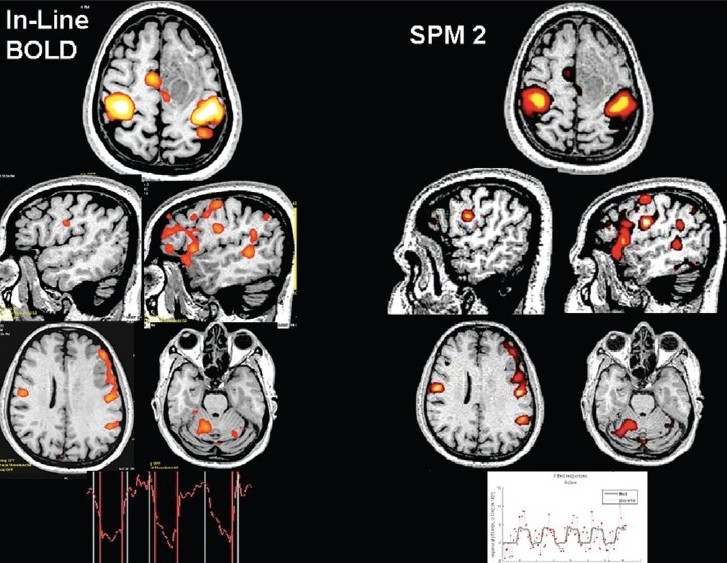

Each fMRI experiment generates a huge amount of data, which needs to be analyzed rigorously in order to obtain the best results. As mentioned earlier, for simple analysis, real-time fMRI processing will help. Our earlier studies have shown that real-time fMRI analysis by vendor-provided fMRI processing tool can give clinically useful information comparable to the time-tested postprocessing tools[18] [Figure 5]. Presently, we perform most of our fMRI studies using real-time fMRI processing. The fMRI results are then coregistered on 3D-FLAIR images. We have found coregistering on 3D-FLAIR more useful than on T1W 3D spoiled gradient images (3D FLASH/3D SPGR).[18]

Figure 5.

Real-time fMRI (vendor provided - Inline BOLD) vs offline processing using statistical parametric mapping (SPM). Inline BOLD fMRI coregistered on 3D-FLASH images with a time-activity curve of a patient with seizures due to a frontal mass lesion, obtained after bilateral finger tapping and verb generation task, is compared to the fMRI results with a time-activity curve after offline processing using SPM2 of the same data set and subsequent coregistration onto 3D-FLASH images using MRIcro software. Note the similarity in activation with real-time processing using inline BOLD and offline processing techniques using SPM2

For event-related paradigms and more complex boxcar paradigms involving more than two states, extensive computation may be required using any of the free or commercial softwares, such as statistical parametric mapping (SPM) (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), FSL ( www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) or Brain Voyager ( www.brainvoyager.de).The basic idea of analysis of functional imaging data is to identify voxels that show signal changes that vary with the changes in the given cognitive or motor state of interest, across the time course of the experiment. This is quite a challenging problem as the fMRI signal changes are very small (of the order of 0.5-5%), leading to a high probability of false negative results. The chance of false positive activation is also very high. Different types of analysis like ‘fixed effects,’ ‘random effects,’ or ‘mixed effects’ can be undertaken.[1]

The greatest problem during any fMRI experiment is subject motion. The BOLD signal is extremely sensitive to motion, which can spoil the whole experiment. Motion can be gross head movement or even the minimal brain motion associated with cardiac or respiratory cycles. Most of the analysis software includes some realignment and coregistration programs to minimize motion effects. Another step is performed using spatial smoothing and temporal filtering, to reduce the noise in the data. The images can then be normalized to a common brain space [e.g., Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template]. This step is utilized mostly in research studies and is not needed for individual patients in the clinical setting. Various statistical tests can then be applied on a voxel-by-voxel basis to test the significance of a particular voxel with an increased signal associated with a certain brain state. The commonly used method is ‘t’ statistics. The ‘t’ statistical maps are then superimposed on high-resolution anatomical images to obtain a clinically useful fMRI output.

Clinical Applications in Patients with Epilepsy

fMRI has been used to study patients with a broad range of neurological disorders and across a wide spectrum of disease severity. The results have provided insights into the mechanism of disease as well as into normal brain function. The majority of the studies published have been performed in research settings. The clinical role of fMRI is being increasingly recognized. One of the earliest and best-validated clinical applications of fMRI was, and remains, presurgical assessment of brain function in patients with brain tumors and epilepsies. There is a substantial body of evidence that shows that fMRI is a good technique for localizing different body representations in the primary motor and somatosensory cortex, as well as for localizing and lateralizing language function prior to surgery. This diagnostic information permits function-preserving and safe treatment. We illustrate the clinical applications through patients whom we have investigated at our hospital during the last three years.

Mapping the Eloquent Cortex

Mapping eloquent areas can be done using invasive methods such as intraoperative cortical stimulation in awake patients, implantation of a subdural grid, or intraoperative recording of sensory-evoked potentials.[19,20] fMRI can obtain these data preoperatively and noninvasively. Together with its high sensitivity for visualizing brain lesions, fMRI can define the relation between the margin of a lesion and any adjacent functionally significant brain tissue. fMRI has the potential to predict possible deficits in motor and sensory perceptual functions or in language that would arise from intrinsic lesion expansion or from therapeutic interventions such as surgery. This helps in decision making during patient management. The relative risk of intervention vs nonintervention can be discussed and explained to the patient and the relatives. Further, a decision on the treatment option to be adopted can be made after considering the cost of treatment and the benefits that can be expected from the treatment.

Earlier studies aimed at comparing intraoperative corticography (ECoG) with fMRI revealed good spatial correlation between the two methods.[21–23] A few studies have also tried to assess the chances of postoperative deficits when a lesion was placed in, or was close to, the eloquent cortex.[24] Lee et al, evaluated the ways in which fMRI studies have influenced patient management. In patients with medically refractory epilepsy, fMRI results helped to assess the feasibility of resection in 70%, to plan the surgical procedure in 43%, and to select patients for invasive mapping in 52%.[25]

In our series of patients, fMRI results matched those from intraoperative cortical stimulation, for lesions in, or close to the eloquent cortex. They also matched Wada test results for language hemispheric dominance.[18] Eloquent cortex mapping was performed in epilepsy patients with tumor, gliosis, or malformation of cortical development in, or close to the eloquent cortex. Our neurosurgeons have found fMRI for eloquent cortex mapping most useful in patients with gliosis, in whom the distortion in anatomy makes prediction of the eloquent cortex extremely difficult. Usually gliotic lesions pull the functionally active areas towards them. Space-occupying lesions such as tumors of the brain primarily displace the functional cortex. For this reason, resection within the boundaries of a lesion should not directly damage the eloquent cortex and result in a significant deficit. In contrast, functional reorganization may or may not happen within the dysplastic cortex in malformations of cortical development. Our study using fMRI on cortical malformations showed that functional reorganization is unpredictable in these lesions.[26] The dysplastic cortex can retain useful brain function. The following three cases illustrate the usefulness of fMRI in selecting patients for surgery, tailoring surgical resection, and in predicting the postsurgical outcome [Figures 6–8].

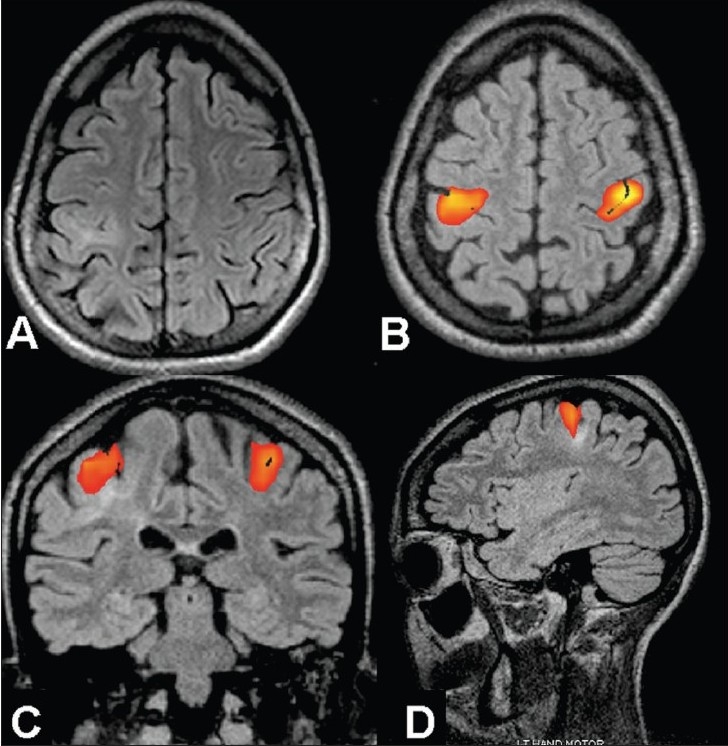

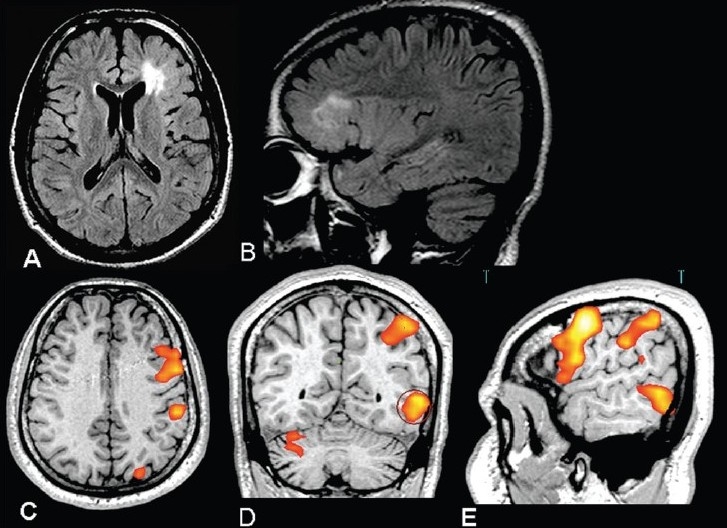

Figure 6.

An 8-year-old female presented with left focal motor seizures since the age of 4 years. The frequency of seizure had increased over the last six months to the current frequency of about 4-5 seizures per month. Axial FLAIR MRI image (A) reveals a thickened cortex with a widened sulcus and underlying white matter hyperintensity, suggestive of focal cortical dysplasia in the right sensorimotor cortex. Inline BOLD fMRI coregistered on 3D-FLAIR axial (B), coronal (C), and sagittal (D) images obtained after bilateral finger tapping vs rest show that the primary motor hand area is lying within the lesion. The likelihood of left limb weakness after surgery was explained to the parents. Since the seizures could be controlled better with the addition of newer drugs, it was decided to keep the patient on follow-up

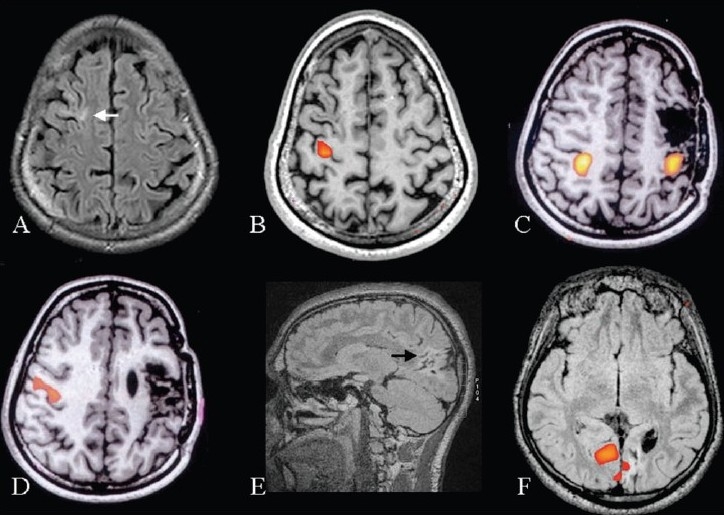

Figure 8.

Three patients with seizures due to a gliotic area. In the first patient, the gliosis was due to an old healed granuloma. Axial FLAIR and inline BOLD coregistered on 3D-FLASH (A, B) images, obtained after left hand movement vs rest, show that the right motor hand area is well away from the gliotic area (white arrow). In the second patient, the gliosis was postsurgical. Inline BOLD fMRI coregistered on 3D-FLASH images, obtained after bilateral hand movement vs rest and tongue movement vs rest (C, D) show that the left hand area is placed closer to the gliotic area, while the face area on the left side is not seen. The left hand activation area is pulled towards the gliotic area. The third patient showed gliosis in the occipital cortex probably secondary to perinatal hypoglycemia. Sagittal FLAIR and inline BOLD fMRI coregistered on axial FLAIR images obtained after visual stimulation show minimal activation in the gliotic left occipital cortex. Most of the visual activation is from the right side. All the three patients, in whom fMRI helped in surgical planning, underwent resection of the gliotic area without developing neurological deficits

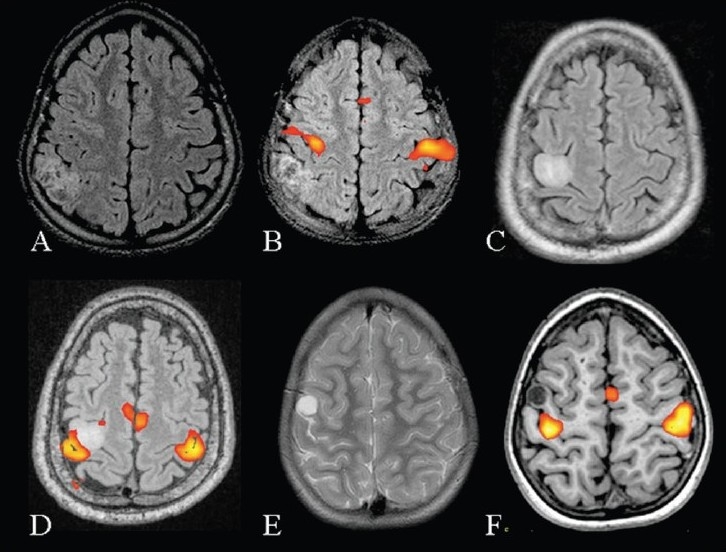

Figure 7.

Three patients with intractable seizures due to a mass lesion close to the sensorimotor cortex. Presurgical mapping of the motor cortex was performed using bilateral finger tapping vs rest, in all the three patients. MRI (axial FLAIR) and fMRI (inline BOLD coregistered on FLAIR) images (A, B) of the first patient show that the lesion is posterior to the right postcentral gyrus. Since the lesion was placed well away from the motor cortex it was decided to proceed with surgery. MRI and fMRI in the second patient (C, D) show the mass lesion to be abutting the right hand area. The postsurgical risk of developing limb weakness was explained to the patient. MRI and fMRI images of the third patient (E, F) show that the lesion is placed in the motor cortex lateral to the right hand area. Fortunately the seizures in this patient could be controlled with antiepileptic medication. It was decided to postpone the surgery and keep the patient on regular follow-up

Lateralization of Language Functions

Intracarotid amobarbital testing (Wada testing) has been the gold standard for identifying lateralization of language and memory functions preoperatively, but it is invasive and therefore carries a small, but definite risk of complications. fMRI offers a promising noninvasive alternative approach.[27] While there is good agreement between the Wada and fMRI results, fMRI is more sensitive to involvement of the nondominant hemisphere. Binder et al,[28] reported a cross-validation study comparing language dominance determined by both fMRI and the Wada test in 22 patients. The majority of studies opine that semantic decision tasks should be used rather than verbal fluency tasks because the latter may lack the ability to activate the posterior language areas.

We have noted that visual presentation of the language paradigm gives much better and consistent results as compared to auditory presentation. Secondly, in a multilingual country like India, auditory language tasks may have to be modified according to the primary language of the patient. This can be solved to some extent by showing the nouns as pictures in the verb generation task. In our fMRI language studies we perform both the semantic decision task and the verbal fluency task by visual presentation. The former is done using a discrimination task of word pairs - related/unrelated, judging the meaning of sentences, and identifying grammatically accepted language. These tasks are preferably done in the primary language of the patient. The following two cases illustrate the usefulness of fMRI in language lateralization [Figures 9 and 10].

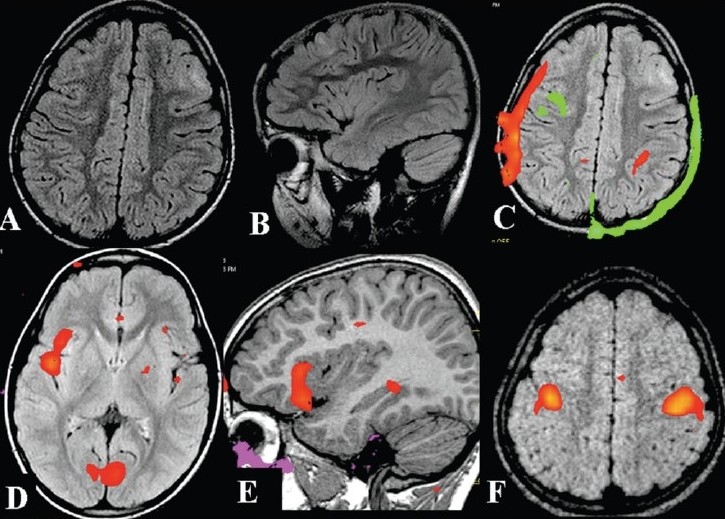

Figure 9.

This 22-year-old right-handed male was referred for surgical treatment of medically refractory partial seizures that he had been suffering from the age of 3 years. The video-scalp EEG monitoring confirmed that the origin of the seizures was from the left frontal lobe. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) FLAIR images show a thickened cortex, poor grey-white distinction and underlying white matter hyperintensity in the left frontal area suggestive of focal cortical dysplasia. Inline BOLD fMRI, language area mapping using verb generation task coregistered on axial (C), coronal (D), and sagittal (E) 3D-FLASH images, shows strong left lateralization of language. The lesion is adjacent to the Broca's area. The fMRI helped to define Broca's area, which was preserved during a tailored surgical resection with no postoperative expressive speech deficit. Histopathology confirmed cortical dysplasia

Figure 10.

A 6-year-old boy with a history of unprovoked seizures from one-and-a-half years of age was put on different antiepileptic drugs without any significant benefit. Video-electroencephalogarphy showed eight complex partial seizures of left frontal origin. The axial (A), and sagittal (B) FLAIR MRI brain images reveal a thickened cortex with hyperintensity in the left frontal area underneath the coronal suture suggestive of focal cortical dysplasia. Before lesionectomy, there was a need for an fMRI study to map the distance of the lesion from the motor cortex and the language area. Inline BOLD fMRI performed using a verb generation task before training (C) and after training (D, E) shows that the language is lateralized to the right side. No interpretation is possible in the fMRI performed before training because of the patient's head movement. On bilateral finger tapping vs rest the motor hand area is seen to be well away from the lesion (F). The boy underwent complete lesionectomy about 8 months back. As expected from the fMRI results, the child did not develop any postoperative neurological deficits and presently there is good seizure control

Memory

Performing fMRI to map memory is more challenging than mapping language. fMRI has been found to be useful in predicting postoperative memory deficits. Memory processing involves encoding and retrieval of face, patterns, words, sceneries, etc. Paradigms for each of these tasks show activation in different areas. It is also difficult to separate brain activity related to memory from that related to other cognitive processes.[29] Detre et al, were the first to demonstrate that fMRI could be used to detect clinically relevant asymmetries in memory activation in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.[30] In a study by Golby et al, fMRI was used to study the lateralization of memory encoding processes (patterns, faces, scenes, and words) within the mesial temporal lobe in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.[31] Rabin et al, used a complex visual scene-encoding task that causes symmetrical mesial-temporal-lobe activation in controls, to determine a relationship between mesial temporal lobe activation asymmetry ratios and postsurgical memory outcome.[32] It was shown that increased activation ipsilateral to the seizure focus is associated with greater memory decline. A more recent study has shown similar results.[33] We have developed simple memory encoding paradigms that can be used in Indian patients with epilepsy. We have tested these in controls and have found the results to be consistent.

Localizing Spontaneous Ictal Activity

Using a newer technique that allows concurrent EEG and fMRI, it is possible to localize the regional metabolic changes accompanying ictal activity.[34,35] These techniques capitalize on the temporal resolution of EEG and spatial resolution of fMRI. The approach of concurrent EEG and fMRI recording tends to be more efficient and accurate as compared to the spike-triggered approach. These techniques may be of particular value in presurgical evaluation of neocortical epilepsy, where paroxysmal activity on EEG may remain poorly localized. In addition, these techniques may provide new insights into the anatomical and pathophysiological correlates of unifocal and multifocal spike discharges.

The MRI scanner is a hostile environment for EEG recordings. MR-compatible EEG recording equipment must ensure patient safety, sufficient quality of the EEG signals, and avoid compromising MRI image quality. Technical issues related to EEG-correlated fMRI have been addressed in detail in several previous articles[36] EEG-correlated fMRI has been shown to be a practicable method in epilepsy patients with frequent interictal epileptiform discharges on scalp EEG.[37,38] A recently published study has evaluated the clinical usefulness of this technique in presurgical localization of the epileptogenic focus.[39]

Challenges for Presurgical fMRI

Patients with epilepsy on long-term antiepileptic medication and those who have frequent seizures can have low intelligence quotients (IQ). These patients may not co-operate for difficult tasks such as the language and memory tasks. They may, however, be able to perform simpler motor tasks. Before fMRI is performed, each of our epilepsy patients undergoes a neuropsychology test for assessing the IQ.[18]

The effects of medication on the BOLD signal response have not been systematically studied as yet. In a study by Jokeit et al,[40] the extent of fMRI activation of the mesial temporal lobes induced by a task based on the retrieval of individual visuospatial knowledge was correlated with the serum carbamazepine level in 21 patients with refractory temporal lobe epilepsy. The study showed that the carbamazepine level can significantly influence the amount of fMRI activation.

Ictal and interictal epileptic activity in a patient with epilepsy can influence the lateralization of mesiotemporal memory functions and language functions.[41,42] The next three challenges mentioned are some of the general challenges for clinical fMRI.[43]

Head motion: Signal intensity changes observed in fMRI images are small. These may be contaminated by gross head motion. Additional minor contamination results from physiologic brain motion (pulsation of the brain, overlying vessels, and cerebrospinal fluid). Head movement during the acquisition phase can be restricted by fixation of the head with straps. However we have found that patients find this uncomfortable. Postprocessing techniques in the offline tools, like realignment and coregistration can help in correcting for head movement. Stimulation paradigms that induce less patient head motion are preferred. Finally, patient cooperation is an essential element both in task compliance and in restricting head motion. If we are planning to do a routine MRI brain study along with fMRI, it is better to do the fMRI study first when patient cooperation is better. In patients in whom we have performed fMRI immediately after the routine brain study we have seen the head movement to be more. Secondly, adequate training before imaging could increase the familiarity with the imaging process. We have found training to be extremely useful in pediatric fMRI and we have been able to do fMRI studies for language lateralization in children as young as 5-6 years of age [Figure 10].

There is a concern that fMRI examinations at a field strength of 1.5 Tesla images predominantly large, draining veins. Gao et al, have shown that fMRI images weighted toward the microcirculation may be obtained at 1.5T, if the pulse sequence is designed for minimizing inflow effects and maximizing BOLD contribution.[44] Maximizing the fMRI signal toward the site of neuronal activity can also be achieved by optimizing the mode of stimulation as shown by the study of Le Rumeur et al.[45]

Does the absence of a BOLD signal in a cortical area indicate with certainty a lack of electrical neuronal activity in that area? Different pathologic conditions could weaken the hemodynamic response that is the source of the fMRI signal. Examples of this include peritumoral vasogenic edema producing mechanical vascular compression and drugs administered to the patient causing change in the hemodynamic autoregulation.

Conclusions

Mapping sensorimotor, visual, language, and memory function using fMRI can identify the eloquent cortex and predict postoperative deficits of specific functions during the presurgical workup of patients with epilepsy. In selected patients with frequent interictal epileptiform discharges, EEG-correlated fMRI has the potential to identify the cortical areas involved in generating the discharges. Better and better techniques are slowly evolving to solve challenges in clinical fMRI. With the availability of higher Tesla magnets, faster sequences, and better paradigms and postprocessing tools, the clinical application of this technique in patients with epilepsy is going to increase in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Annamma George (speech therapist), Ms. Haritha, Mr. Sujesh, Dr. Niranjan (biomedical engineers) and the MR technologists for helping us perform the fMRI studies. The authors thank Mr. Vikas and Mr. Liji for the illustrations.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Matthews PM, Jezzard P. Functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:6–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy CS, Sherrington CS. On the regulation of the blood-supply of the brain. J Physiol. 1890;11:85–158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1890.sp000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thulborn KR, Waterton JC, Mathews PM, Radha GK. Oxygenation dependence of the transverse relaxation time of water protons in whole blood at high field. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;714:265–70. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa S, Lee TM, Nayak AS, Glynn P. Oxygeneration sensitive contrast in magnetic resonance image of sodent brain at high magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:68–78. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, Goldberg IE, Weisskoff RM, Poncelet BP, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:5675–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandettini PA, Wong EC, Hinks RS, Tikofsky RS, Hyde JS. Time course EPI of human brain function during taskactivation. Magn Reson Med. 1992;25:390–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910250220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fration J, Bruhn H, Merboldt KD, Hanicke W, Math D. Dynamic MR imaging of human brain oxygenation during rest and photic stimulation. J Magn Reson Imaing. 1992;2:501–5. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880020505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogawa S, Tank DW, Memon R, Ellermann JM, Kim SG, Merkle H, et al. Intrinsic signal charges accompanying sensory stimulation: Functional brain mapping with magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:5951–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox PT, Raichle ME. Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory stimulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83:1140–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.4.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner R, Le Bihan D, Moonen CT, Despres D, Frank J. Echo-planar time course MRI of cat brain oxygenation changes. Magn Reson Med. 1991;22:159–66. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910220117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duong TQ, Kim DS, Ugurbil K, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of the BOLD fMRI signals: Toward mapping submillimeter cortical columns using the early negative response. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:231–42. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200008)44:2<231::aid-mrm10>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, et al. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412:150–7. doi: 10.1038/35084005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansfield P. Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes. J Phys Chem. 1977;10:L55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoeller M, Krings T, Reinges MH, Hans FJ, Gilsbach JM, Thron A. Movement artefacts and MR BOLD signal increase during different paradigms for mapping the sensorimotor cortex. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:279–84. doi: 10.1007/s007010200036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krings T, Reinges MH, Erberich S, Kemeny S, Rohde V, Spetzger U, et al. Functional MRI for presurgical planning: Problems, artefacts, and solution strategies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:749–60. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.6.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammeke TA, Yetkin FZ, Mueller WM, Morris GL, Haughton VM, Rao SM, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of somatosensory stimulation. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:677–81. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199410000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, Cox RW, Rao SM, Prieto T. Human brain language areas identified by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 1997;17:353–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00353.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kesavadas C, Thomas B, Sujesh S, Ashalata R, Abraham M, Gupta AK, et al. Real-time functional MR imaging (fMRI) for presurgical evaluation of paediatric epilepsy. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:964–74. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger MS, Cohen WA, Ojemann GA. Correlation of motor cortex brain mapping data with magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:383–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.3.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregorie EM, Goldring S. Localization of function in the -excision of lesions from the sensorimotor region. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:1047–54. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.61.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jack CR CR, Jr, Thompson RM, Butts RK, Sharbrough FW, Kelly PJ, Hanson DP, et al. Sensory motor cortex: Correlation of presurgical mapping with functional MR imaging and invasive cortical mapping. Radiology. 1994;190:85–92. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.1.8259434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehericy S, Duffau H, Cornu P, Capelle L, Pidoux B, Carpentier A, et al. Correspondence between functional magnetic resonance imaging somatotopy and individual brain anatomy of the central region: Comparison with intraoperative stimulation in patients with brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:589–98. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.4.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puce A, Constable RT, Luby ML, McCarthy G, Nobre AC, Spencer DD, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of sensory and motor cortex: Comparison with electrophysiological localization. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:262–70. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yetkin FZ, Mueller WM, Morris GL, McAuliffe TL, Ulmer JL, Cox RW, et al. Functional MR activation correlated with intraoperative cortical mapping. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1311–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CC, Ward HA, Sharbrough FW, Meyer FB, Marsh WR, Raffel C, et al. Assessment of functional MR imaging in neurosurgical planning. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1511–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kesavadas C, Thomas B, Sujesh S, Gupta AK. Functional MR Imaging (fMRI) Study of cortical reorganisation in focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) Proceedings of Radiological Society of North America (RSNA); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adcock JE, Wise RG, Oxbury JM, Oxbury SM, Matthews PM. Quantitative fMRI assessment of the differences in lateralization of language-related brain activation in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2003;18:423–38. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Binder JR, Swanson SJ, Hammeke TA, Morris GL, Mueller WM, Fischer M, et al. Haughton determination of language dominance using functional MRI: A comparison with the Wada test. Neurology. 1996;46:978–84. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jokeit H, Okujava M, Woermann FG. Memory fMRI lateralizes temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2001;57:1786–93. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detre JA, Maccotta L, King D, Alsop DC, Glosser G, D'Esposito M, et al. Functional MRI lateralization of memory in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1998;50:926–32. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golby AJ, Poldrack RA, Illes J, Chen D, Desmond JE, Gabrieli JD. Memory lateralization in medial temporal lobe epilepsy assessed by functional MRI. Epilepsia. 2002;43:855–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.20501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabin ML, Narayan VM, Kimberg DY, Casasanto DJ, Glosser G, Tracy JI, et al. Functional MRI predicts post-surgical memory following temporal lobectomy. Brain. 2004;127:2286–98. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell HW, Richardson MP, Symms MR, Boulby PA, Thompson PJ, Duncan JS, et al. Preoperative fMRI predicts memory decline following anterior temporal lobe resection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007 Oct 26; doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.115139. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 17898035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krakow K, Woermann FG, Symms MR, Allen PJ, Lemieux L, Barker GJ, et al. EEG-triggered functional MRI of interctal epileptiform activity in patients with partial seizures. Brain. 1999;122:1679–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.9.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lemieux L, Saleek-Haddadi A, Josephs O, Allen P, Toms N, Scott C, et al. Event-related fMRI with simultaneous and continuous EEG: Description of the method and intital case report. Neuroimage. 2001;14:780–7. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krakow K, Allen PJ, Symms MR, Lemieux L, Josephs O, Fish DR. EEG recording during fMRI experiments: Image quality. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;10:10–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200005)10:1<10::AID-HBM20>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aghakhani Y, Bagshaw AP, Benar CG, Hawco C, Andermann F, Dubeau F, et al. fMRI activation during spike and wave discharges in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Brain. 2004;127:1127–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gotman J, Grova C, Bagshaw A, Kobayashi E, Aghakhani Y, Dubeau F. Generalized epileptic discharges show thalamocortical activation and suspension of the default state of the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15236–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504935102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zijlmans M, Huiskamp G, Hersevoort M, Seppenwoolde JH, van Huffelen AC, Leijten FS. EEG-fMRI in the preoperative work-up for epilepsy surgery. Brain. 2007;130:2343–53. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jokeit H, Okujava M, Woermann FG. Carbamazepine reduces memory induced activation of mesial temporal lobe structures: A pharmacological fMRI-study. BMC Neurol. 2001;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janszky J, Ollech I, Jokeit H, Kontopoulou K, Mertens M, Pohlmann-Eden B, et al. Epileptic activity influences the lateralization of mesiotemporal fMRI activity. Neurology. 2004;63:1813–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145563.53196.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jayakar P, Bernal B, Santiago Medina L, Altman N. False lateralization of language cortex on functional MRI after a cluster of focal seizures. Neurology. 2002;58:490–2. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sunaert S, Yousry TA. Clinical applications of functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2001;11:221–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao JH, Milller I, Lai S, Xiong J, Fox PT. Quantitative assessment of blood inflow effects in functional MRI signals. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:314–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Rumeur E, Allard M, Poiseau E, Jannin P. Role of the mode of sensory stimulation in presurgical brain mapping in which functional magnetic resonance imaging is used. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:427–31. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.3.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]