Abstract

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) Pain Guidelines of 1994 recognized pain as a critical symptom that impacts quality of life (QOL). The barriers to optimum pain relief were classified into three categories: patient, professional and system barriers. A prospective, longitudinal clinical trial is underway to test the effects of the “Passport to Comfort” innovative intervention on pain and fatigue management. This paper reports on pre-intervention findings related to barriers to pain management. Cancer patients with a diagnosis of breast, lung, colon, or prostate cancer who reported a pain rating of ≥ 4 were accrued. Subjects completed questionnaires to assess subjective ratings of overall QOL, barriers to pain management, and pain knowledge at baseline and at one- and three-month evaluations. A chart audit was conducted at one month to document objective data related to pain management. The majority of subjects had moderate (4–6 on a zero to ten numeric rating scale) pain at the time of accrual. Patient barriers to pain management existed in attitudes and knowledge regarding addiction, tolerance, and not being able to control pain. Subjects who were currently receiving chemotherapy were reluctant to communicate their pain with health care professionals. Professional and system barriers were focused around screening, documentation, re-assessment, and follow-up of pain. Lack of referrals to supportive care services for patients was also noted. Several well-described patient, professional, and system barriers continue to hinder efforts to provide optimal pain relief. Phase II of this initiative will attempt to eliminate these barriers using the “Passport” intervention to manage cancer pain.

Keywords: Pain, barriers, quality of life, QOL

Introduction

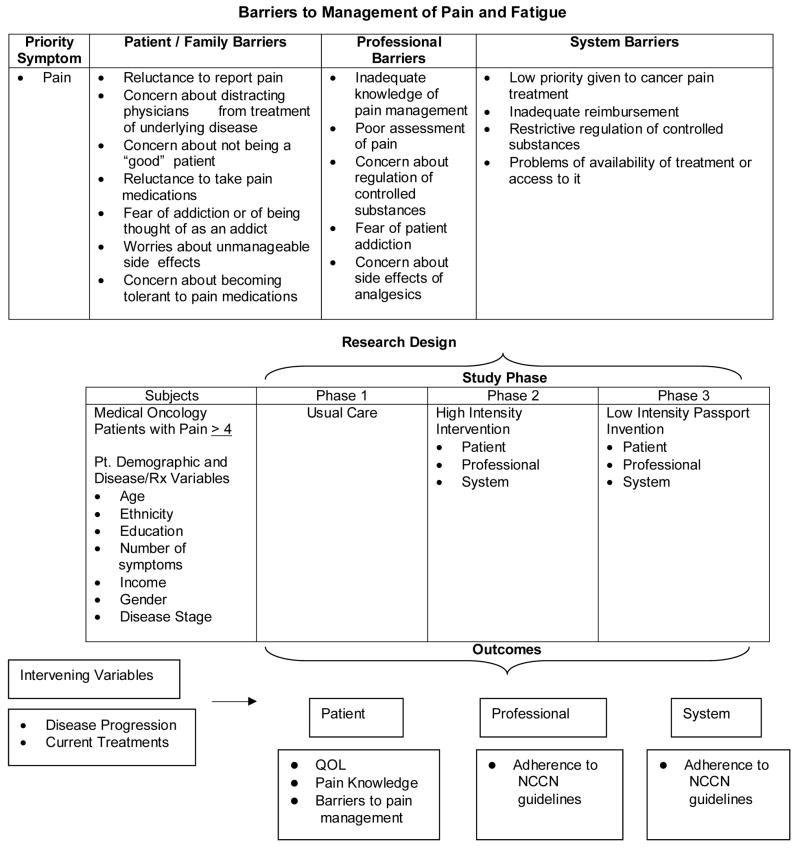

Major deficiencies in the treatment of cancer symptoms such as pain have been documented over the past two decades. Pain is recognized as impacting all dimensions of patient’s quality of life (QOL).1 One framework often applied to understanding the reasons for unrelieved symptoms is to examine the barriers to their relief. The barriers to optimum pain relief were captured during the development of the first national clinical practice guidelines on cancer pain published by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research in 1994. 2 These barriers were classified into three categories: patient, professional and system barriers.

The literature has consistently documented that patients play a key role in the undertreatment of pain.3,4 Patients are reluctant to report their pain for reasons including fear of side effects, fatalism about the possibility of achieving pain control, fear of distracting physicians from treating cancer, and belief that pain is indicative of progressive disease.4–9 There are also significant health care professional barriers to adequate pain relief. Physicians, nurses, and other members of the interdisciplinary team often fail to adequately assess the patient’s pain or to recognize patient barriers.10–12 Professionals lack knowledge of the principles of pain relief, side effect management, or understanding of key concepts like addiction, tolerance, dosing, and communication.13–15

System barriers include legal and regulatory structures that interfere with the provision of optimal care as well, as inadequate reimbursement for pain services. System barriers can be internal, such as low referrals to supportive care services, or external, such as reimbursement and regulatory constraints.2 Synthesis of pain literature by the Institute of Medicine and the National Cancer Policy Board have continued to document the importance of these system barriers on the ultimate outcomes of patient care. 1,16,17

In response to overwhelming evidence of the impact of these barriers on symptom management, the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI) issued a call for proposals with the intent of moving beyond descriptive studies to test innovative models that would eliminate these barriers. This paper reports on Phase I results from one of the projects supported by this NCI initiative and conducted at a NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center to test the effects of an intervention on pain and fatigue management.

Methods

Design

Figure 1 presents the overall “Passport” model of care. Barriers to the management of pain are identified in the three categories of patient, professional, and system. This five-year study is designed in three phases. Phase I, from which data on pain is presented in this paper, assessed Usual Care in order to describe the current status of pain and fatigue management in this population and setting. Phase II will be a High Intensity Intervention in which patient and professional education, as well as peer audit and feedback will be implemented in order to address the barriers. Phase III will be a Low Intensity Support Intervention, during which the intervention will be moved to a more realistic model of care in clinical settings so that it can be replicated and maintained at after the project concludes.

Figure 1.

Study model.

This project demonstrates innovation by translating the evidence-based guidelines for pain as developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).18 The symptom of pain was selected because it is consistently cited to be common and distressing for cancer patients. The NCCN Pain Guidelines have not been evaluated clinically to test feasibility in implementation. This study will provide insight into the use of NCCN guidelines and serve as a model for extending these and other guidelines into practice to eliminate barriers. The study design was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Sample

Study participants were recruited from the Medical Oncology Adult Ambulatory Care Clinic at an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of breast, colon, lung, or prostate cancer, time since diagnosis of at least one month, an expected prognosis of six months or greater, and subjective pain rating of ≥ 4 (moderate to severe pain) on a numeric scale of 0–10 (0=no pain; 10=worst pain imaginable). The criteria were intended to target patients with moderate to severe symptom intensity who would serve as an appropriate comparison for the intervention phase and to decrease the heterogeneity of the population by focusing on patients with solid tumors who have some degree of common treatment regimens. Eligible patients were recruited to assess Usual Care in Phase I of this three-phase clinical trial. Stratification was conducted to reflect a sample of the four diagnoses that were proportional to the cancer center population.

Procedure

Research nurses approached all individuals meeting eligibility criteria during a regularly scheduled clinic visit. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation in this study. Participants provided demographic and disease data at baseline along with other outcome measures to assess overall QOL, barriers to pain management, and pain knowledge. All outcome measures were repeated later at one month and three months. A chart audit was conducted at the one-month evaluation to assess potential system barriers to pain assessment and management.

Outcome Measures

The Demographic and Treatment Data Tool was designed to capture key disease and treatment variables of importance in describing the population and for analysis of influencing variables. Basic demographic data, such as age, gender, disease type, stage of disease, and treatments received, were collected at baseline. Other variables, such as current medications, co-morbidities, and Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), were obtained at baseline and during follow-up evaluations. A detailed medication list was also obtained at all follow-up evaluations to capture types of pain medications provided for patients.

The City of Hope Quality of Life–Patient Tool (COH QOL) is a 45-item multidimensional tool encompassing four domains of Physical, Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Well-Being based on the QOL conceptual model developed by the investigators.19,20 Internal consistency reliability is 0.77–0.89 for the four subscales and .93 overall. Measures of validity of the generic patient version include content validity with the FACT instrument (r = 0.78), and factor analysis.

The Barriers Questionnaire-II (BQ-II) AU: CHANGE OKAY? was developed by Ward and colleagues8 to measure patient-reported barriers to pain management. Significant (t=−2.16, P<0.05) construct validity and a factor analysis revealed four factors: 1) physiologic effects, 2) fatalism, 3) communication, and 4) harmful effects. The BQ-II total has an internal consistency reliability coefficient alpha of 0.89 (n=134), and a range of 0.75–0.85 for the subscales. The mean score for the total scale was 1.53 (SD=0.73).

The Patient Pain Knowledge Tool was drafted by the investigators based on the NCCN Pain Guidelines.18 This 15-item questionnaire was used as an assessment of patient’s knowledge and beliefs. The questions asked subjects to identify whether each statement regarding pain is true or false. This tool was written at a low literacy level and to be less burdensome for subjects to complete. Internal consistency reliability analysis was performed on these subjects’ scores for the QOL, BQ-II, and knowledge tests using Cronbach’s alpha. Internal consistency reliability of the instrument was 0.67.

The Pain Chart Audit Tool compared the recommendations of the NCCN Pain Guidelines with the actual care provided and served as the primary measure to identify professional and system barriers to pain management. The audit tool was pilot-tested and refined prior to subject accrual. The audits were conducted by research nurses during the one-month evaluation.

Statistical Methods

SPSS Sample Power and the PASS power calculation software were used to estimate sample size for this study based on findings of the PI’s previous pain intervention studies. A sample of 50 patients provided 80% power to detect significance in the interaction effect of this statistical design, with a two-tailed alpha of 0.05.

Analyses included tabulation of standard summary statistics of demographic characteristics, disease/treatment characteristics, and all scores at each time period. In addition to demographic and clinical characteristics, descriptive statistics were computed for QOL items, subscale scores and total score, as well as the Karnofsky performance scale score. Using Pain Chart Audit data, the frequencies of NCCN Guideline pain assessment and management provider behaviors were calculated. Multiple response frequencies were calculated on support services ordered, co morbidities, and medications.

BQ-II subscale scores and total score, and knowledge test score were compared across selected demographics (race/ethnicity, education, religious preference, marital status, cancer diagnosis, and chemotherapy status) using Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) for subscales, and ANOVA for total BQ-II score and knowledge test score.

Subjects with missing scale or subscale scores were compared with subjects having non-missing scores to determine any bias underlying the missing data. For data that are missing completely at random (MCAR) or missing at random (MAR), the EM (estimation-maximization) method of imputation was used to replace missing values.

Results

A total of 100 subjects were accrued for Phase I. Of the 100 subjects, 83 had complete data that was evaluable. Of the 83 subjects with evaluable data, 38 of these met the criterion for having moderate to severe pain (≥ 4) at the time of accrual. This paper reports on findings for the 38 evaluable subjects with pain. The mean age of these subjects was 57 and 76% were female. This sample included 55% Caucasian, 18% African American, 23% Hispanic and 3% Asian subjects. The majority of subjects (52.6%) had a college degree or graduate degree, while 44.8% had an education level of high school or less. Most subjects (34%) were retired while 26% were currently unemployed secondary to their cancer.

In terms of disease-specific variables, the sample included 57% breast, 24% colon, 16% lung, and 8% prostate cancer patients. The majority of subjects had Stage III or IV disease at the time of accrual. They were diagnosed at a mean of 3.9 years ago and had received multimodality treatments including surgery (63%), chemotherapy (82%) and radiation (42%). The majority of subjects (73%) were currently receiving chemotherapy. Forty-five percent of subjects reported a baseline KPS of 90. The majority of subjects (76.2%) reported having moderate pain (4–6) based on a 0–10 scale, and the mean pain score was 5. Complete demographic data is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject Demographic and Treatment Variables

| VARIABLE | COUNT | PERCENTAGE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 21 | 55.3 |

| African American | 7 | 18.4 |

| Hispanic | 9 | 23.7 |

| Asian | 2.6 | 2.6 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| No high school | 2 | 5.3 |

| High school only | 15 | 39.5 |

| College | 17 | 44.7 |

| Graduate/Professional | 3 | 7.9 |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married | 4 | 10.5 |

| Married | 18 | 47.4 |

| Living with partner | 2 | 5.3 |

| Divorced | 8 | 21.1 |

| Widowed | 6 | 15.8 |

|

| ||

| Living Arrangements | ||

| Spouse | 18 | 47.4 |

| Parents | 3 | 7.9 |

| Children | 19 | 50.0 |

| Friends/signif. other | 1 | 2.6 |

| Other | 3 | 7.9 |

| Live alone | 4 | 10.5 |

|

| ||

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 6 | 15.8 |

| Part time | 4 | 10.5 |

| Retired | 13 | 34.2 |

| Retired b/c of cancer | 3 | 7.9 |

| Homemaker | 2 | 5.3 |

| Unemployed on disability | 10 | 26.3 |

|

| ||

| Cancer Diagnosis | ||

| Breast | 20 | 52.9 |

| Colon | 9 | 23.7 |

| Lung | 6 | 15.8 |

| Prostate | 3 | 7.9 |

|

| ||

| Stage of disease | ||

| I | 2 | 5.2 |

| II | 6 | 15.8 |

| III | 11 | 29 |

| IV | 18 | 47.4 |

|

| ||

| Current status of disease | ||

| Newly diagnosed, under tx | 10 | 26.3 |

| Completed tx, CA free | 2 | 5.3 |

| Recurrent, under tx | 20 | 52.6 |

| Other | 5 | 13.2 |

|

| ||

| Current and Previous Tx | ||

| Surgery | ||

| Yes | 24 | 63.2 |

| No | 13 | 34.2 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 31 | 81.6 |

| No | 7 | 18.4 |

| Currently receiving chemo | ||

| Yes | 28 | 73.7 |

| No | 10 | 26.3 |

| Radiation | ||

| Yes | 16 | 42.1 |

| No | 22 | 57.9 |

| Currently receiving radiation | ||

| Yes | 1 | 2.6 |

| No | 37 | 97.4 |

|

| ||

| KPS | ||

| 100 | 3 | 7.9 |

| 90 | 17 | 44.7 |

| 80 | 9 | 23.7 |

| 70 | 4 | 10.5 |

| 60 | 4 | 10.5 |

|

| ||

| Pain rating | ||

| 4 | 11 | 28.9 |

| 5 | 11 | 28.9 |

| 6 | 7 | 18.4 |

| 7 | 4 | 10.5 |

| 8 | 4 | 10.5 |

| 9 | 1 | 2.6 |

Tx = treatment; CA = cancer; KPS = Karnofsky Performance Status.

Overall QOL

Baseline QOL data revealed low scores for all four subscales of the COH QOL tool. As one would expect for this sample with primarily advanced disease, overall QOL was decreased. The overall QOL score was only 5.11(SD 1.46) on a scale where 0 = worst outcome to 10 = best outcome. All domains, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being, had moderately low scores. In the area of physical well-being, patients experienced few problems with symptoms such as nausea but had trouble with pain, sleep changes, and fatigue. Subject’s scores in the psychological domain were particularly low. These results reflect severe distress at initial diagnosis, fear of recurrence, distress with cancer treatments, and fear of a second cancer. In the domain of social well-being, subjects reported receiving support, but reported severe family distress. Spiritually, subjects sensed a purpose or mission in their lives and were hopeful, but felt tremendous uncertainty for their futures. Overall QOL score, individual item scores, and subscale scores by QOL domain are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality of Life Scale: Individual Items and Subscale Scores (n=38)

| VARIABLE | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Physical Well Being | |

| To what extent are the following a problem: | |

| Fatigue | 4.19(2.56) |

| Appetite changes | 6.16(3.01) |

| General aches or pain | 4.16(2.26) |

| Sleep changes | 4.97(2.90) |

| Constipation | 5.63(3.00) |

| Nausea | 7.18(2.81) |

| Menopausal Symptoms | 8.38(2.51) |

| Rate overall physical health | 5.26(2.04) |

| Physical Subscale | 5.66(1.65) |

|

| |

| Psychological Well Being | |

| How difficult is it to cope? | 5.26(2.45) |

| How good is QOL? | 5.89(2.29) |

| How much happiness? | 6.19(2.33) |

| Do you feel like you are in control? | 5.08(3.13) |

| How satisfying is your life? | 5.95(2.82) |

| How is your ability to concentrate or remember things? | 5.50(2.50) |

| How useful do you feel? | 4.74(2.65) |

| Has illness caused changes in appearance? | 3.89(2.82) |

| Has illness changed self-concept? | 4.45(2.91) |

| How distressing were the following? | |

| Initial diagnosis | 1.87(2.35) |

| Cancer treatments | 3.11(2.57) |

| Time since treatment was completed | 5.09(3.20) |

| How much anxiety do you have? | 5.11(2.79) |

| How much depression do you have? | 6.05(3.18) |

| To what extent are you fearful of: | |

| Future diagnostic tests | 4.37(2.91) |

| A second cancer | 4.03(2.79) |

| Recurrence | 2.95(2.59) |

| Psychological Subscale | 4.66(1.70) |

|

| |

| Social Concerns | |

| How distressing has illness been for your family? | 2.81(2.57) |

| Is the amount of support you receive from others sufficient? | 7.50(2.47) |

| Is your illness interfering with your personal relationships? | 5.53(3.14) |

| Is sexuality impacted by illness? | 4.03(4.01) |

| To what degree has illness interfered with your employment? | 3.81(4.24) |

| To what degree has illness interfered with your activities at home? | 2.82(2.62) |

| How much isolation do you feel? | 4.24(2.89) |

| How much financial burden have you incurred as a result of illness? | 3.16(3.21) |

| Social Subscale | 4.21(2.13) |

|

| |

| Spiritual Well Being | |

| How important are religious activities such as praying, going to church? | 7.50(3.25) |

| How important are spiritual activities such as meditation? | 6.68(3.76) |

| How much has your spiritual life changed as a result of cancer diagnosis? | 7.61(2.98) |

| How much uncertainty do you feel about your future? | 3.37(3.11) |

| To what extent has illness made positive changes in your life? | 5.50(3.62) |

| Do you sense a purpose/mission in life or a reason for being alive? | 7.68(2.96) |

| How hopeful do you feel? | 7.58(2.49) |

| Spiritual Subscale | 6.56(2.32) |

|

| |

| OVERALL QOL SCALE SCORE | 5.11 (1.46) |

Patient Barriers to Pain Management

The BQ-II captured patient-related barriers regarding pain management. The lowest scores were found in the subscales of harmful effects and physiological effects of pain medications (Table 3). Subjects believed that pain cannot be relieved, and thought that pain medicine is not an effective way to control pain. There was a strong belief that pain medicines are addictive, and that cancer patients are at high risk of developing addiction. Subjects also believed that their body becomes tolerant to the effects of pain medicine and the medications would not provide pain relief in the future. Additionally, there was a fear that pain medicine will mask health changes. Additional item scores are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Barriers Questionnaire-II (BQ-II)

| Variable | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Subscale | |

| Physiological Effects | 2.29 (0.83) |

| Fatalism | 1.36 (0.94) |

| Communication | 1.24 (1.20) |

| Harmful Effects | 2.5 (1.13) |

|

| |

|

Items with Greatest Barriers to Pain Management | |

| Reports of pain could distract a doctor from curing the cancer | 0.84 (1.19) |

|

| |

| If doctors have to deal with pain they won’t concentrate on curing the disease | 0.87 (1.21) |

|

| |

| Doctors might find it annoying to be told about pain | 1.08 (1.50) |

|

| |

| Cancer pain can be relieved | 1.18 (1.18) |

|

| |

| It is important for the doctor to focus on curing illness, and not waste time controlling pain | 1.19 (1.16) |

|

| |

| Medicine can relieve cancer pain | 1.32 (1.12) |

|

| |

| It is important to be strong by not talking about pain | 1.47 (1.70) |

|

| |

| Pain medicine can hurt your immune system | 1.58 (1.55) |

|

| |

| Pain medicine can effectively control cancer pain | 1.58 (1.08) |

|

| |

| Constipation from pain medicine cannot be relieved | 1.62 (1.48) |

|

| |

| Pain medicine makes you say or do embarrassing things | 1.68 (1.58) |

|

| |

| It is easier to put up with the pain than with the side effects that come from pain medicine | 1.81 (1.53) |

AU: CHANGE IN TITLE OKAY WITH YOU?

The overall score for the Patient Pain Knowledge Tool was 73% correct, which was fairly high. Subjects had the most knowledge in items such as methods to prevent constipation, the use of a pain scale, the two types of pain, and other common side effects of pain medication. However, important knowledge deficits existed in the cause of pain, addiction with opioids, stopping pain medicine suddenly, and the need to increase pain medicine as being a sign of addiction. Table 4 provides overall scores and individual item scores for this tool.

Table 4.

Patient Pain Knowledge Tool

| Knowledge Item | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Pain can be divided into two types: acute and chronic | 0.87 (0.34) |

| The most common cause of pain is cancer | 0.45 (0.50) |

| Taking opioids will always leads to addiction | 0.53 (0.51) |

| The side effects that pain medications cause can be prevented or treated | 0.66 (0.48) |

| It is not important for doctors and nurses to know about your pain | 0.79 (0.41) |

| A pain scale is used to describe how much pain you are feeling | 0.95 (0.27) |

| Cancer pain can be treated only with medicines and not by using other treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation, surgery | 0.68 (0.47) |

| Non-opioid medicines such as Tylenol and ibuprofen are used for severe pain only | 0.79 (0.41) |

| Opioid medicines are divided by how quickly they begin to work and how long they work | 0.76 (0.43) |

| One of the most common side effect of taking morphine is constipation | 0.68 (0.47) |

| Drinking more fluids, eating more fiber foods, and some mild exercise along with some laxatives are the best ways to prevent constipation | 1.0 (0.00) |

| Other common side effects of pain medicine include nausea and some confusion | 0.84 (0.37) |

| A need to increase the dose of your pain medicine is a sign of addiction | 0.61 (0.50) |

| You can stop your pain medications suddenly without worries about side effects | 0.63 (0.49) |

| Around-the-clock dosing of pain medicine means that the medicine will be given on a regular basis, whether you are in pain or not | 0.74 (0.45) |

| OVERALL SCORE | 0.73 (0.13) |

Mean comparisons between selected demographic variables and the BQ-II and Patient Pain Knowledge Tool were undertaken. Results indicate that subjects’ ethnicity, education level, religious preference, marital status, and cancer diagnosis did not affect barriers to pain management for this sample. However, subjects who are currently receiving chemotherapy treatments were more likely to believe that communication of pain might distract physicians from treatment of underlying disease (0.98 vs. 1.97; P=0.024). Subjects with pain who are receiving chemotherapy were also more likely to believe that “good patients” do not complain about pain.

Professional and System Barriers to Pain Management

The Pain Chart Audit Tool captured barriers to pain management that were related to professional practice and system outcomes. Items in the audit tool assessed documentation and assessment of pain, as well as treatment and referrals to supportive care services. Overall, only 7.8% of subjects were screened for pain at each clinic visit. There was no correlation with pain rating documentation and re-assessment at subsequent follow-up visits. Only 2.6% of subjects had the quality of their pain documented. Seventy-six percent of patients had pain ratings of moderate severity (4–6) and 24% had severe pain (7–10). The patient’s pain management as documented in the medical record was compared to the recommendations in the NCCN pain guidelines (Table 5). There was very limited (7.9%) documented pain screening, no documentation of numerical pain ratings or evidence of reassessment.

Table 5.

Pain Chart Audit Results Compared to NCCN Pain Guideline Recommendations

| NCCN Recommendations | AUDIT RESULTS (% Yes) |

|---|---|

| Screening of pain at all visits | 7.9 |

| Pain rating documented in transcriptions | 0 |

| Pain rating documented consistently | 0 |

| Quality of pain documented | 2.63 |

| Reassessment at each visit | 0 |

| Pain Management Recommendations | |

| NSAID | 5.2 |

| Short-acting opioids | 60 |

| Long-acting opioids initiated | 26 |

| Bowel regimen | 26 |

| Education | 2.63 |

| Psychosocial support | 0 |

| Pain specialty consults | 0 |

| Reassessment after initiation of opioids | 0 |

| Adjuvant Medications | 45 |

| Other Supportive Care Services Referrals | |

| Rehabilitation/PT | 0 |

| Psychology/Psychiatry | 0 |

| Social Work | 5.26 |

| Pastoral Care | 0 |

| Transitions Program (Hospice/Palliative Care) | 0 |

In terms of pharmacologic management, 5.2% of subjects received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Sixty percent of patients were on short acting opioids and 26% were given long-acting opioids. Similarly, only 26% of patients had a bowel regimen prescribed. No patients had documented pain reassessment after opioids were initiated. Only 45% of patients were receiving an adjuvant medication such as antidepressants or anticonvulsants. Finally, only 5.2% of subjects received a social work consult and there were no other psychosocial support consults. No patients in this sample received a consult to a pain specialist and there was no documented pain education. Table 6 provides audited chart items as compared to recommendations in the NCCN pain guidelines.

Table 6.

Pain Chart Audit Items Based on NCCN Pain Guideline Recommendations

| NCCN Recommendations | Chart Audit Items |

|---|---|

| Quantify pain intensity |

|

| Pain intensity rating |

|

| Characterize quality of pain |

|

| Management of patients with no pain |

|

| Managing mild to moderate (1–6) pain |

|

| Management of severe (7–10) pain |

|

| Managing side effects of opioids |

|

| Patient and family education |

|

| Supportive care consultations |

|

Discussion

In this study, we identified a cancer population with mainly advanced disease, which is typical for a tertiary cancer center. The majority of subjects was Caucasian, had a breast cancer diagnosis, and are currently receiving chemotherapy. Subjects primarily reported experiencing moderate (4–6 on a zero to ten numeric rating scale) pain. Baseline overall QOL, as expected, was fairly low. Predictably, subjects had many QOL concerns. Physically, our sample reported problems with pain, sleep changes, and fatigue, symptoms described in the literature as distressing for cancer patients.21,22 Severe problems in this sample in the psychological domain underscores the need for psychosocial health care professionals. Subjects in this study also reported severe family distress. This is consistent with previous studies conducted by this team related to understanding the family perspective of cancer pain management.23–28

The patient-related barriers to pain management obtained from this study confirm data reported in the literature,29,30 as well as underscores the importance of addressing these barriers. Overall, subjects in this study believed that addiction and tolerance to pain medication is common in cancer patients. Furthermore, there was a strong belief in the masking of health changes if pain medication is used. Numerous studies have documented the very significant patient barrier of fears of addiction. 3,4,31 Overall, subjects in this study scored fairly high on pain knowledge, but knowledge deficits continue to exist in areas related to addiction and proper utilization of pain medications. Model programs have emphasized patient teaching interventions including the use of pain assessment tools, strategies to dispel misconceptions, and patient coaching regarding the reporting and documenting of their symptoms. 32–34 The findings from our study support this hypothesis.

Previous studies have found that patients are reluctant to communicate information about their pain or its relief to health care professionals. 4,8,10 In this study, we found that subjects who are currently receiving active treatment with chemotherapy were more reluctant to communicate their pain experience to their health care professionals. Future pain interventions with cancer patients, particularly those in active treatment, should address and facilitate the communication of symptoms between patient and health care professionals.

Results related to professional and system barriers indicate that much improvement is needed in the screening, re-assessment, and follow-up evaluations of pain. More importantly, proper utilization of long- vs. short-acting opioid analgesics and aggressive bowel regimen to prevent opioid-related constipation is needed for optimal pain relief. Finally, internal system barriers such as a lack of referral to supportive care services should be addressed. The investigators realize that some interventions, including consultations or pain reassessment, may have occurred but simply were not documented. One overall observation was that patients seen in the outpatient clinic setting had much less supportive care available as compared to the inpatient setting.

Following Phase I, Phase II (High Intensity Intervention) began with the two intensive education sessions of medical oncology staff on assessment and management of pain and fatigue. The sessions were taught by two nationally recognized physicians in palliative care. Patients in Phase II receive four individual education sessions on the assessment and management of pain and fatigue. An education packet containing information on pain and fatigue is provided to subjects and are based on NCCN Guidelines. Follow-up and data collection time points are identical to those in Phase I. Peer feedback is provided to physicians on a monthly basis. Large posters available throughout the clinic serve as a reminder for both patient and provider of the importance to assess for pain and fatigue.

In conclusion, this Phase I (Usual Care) study identified several patient, professional, and system related barriers to pain management that continues to hinder our efforts to provide optimal pain relief. Phase II (High Intensity Intervention) for this five-year, NCI-funded clinical trial will attempt to eliminate these barriers through intensive patient education and professional interaction using the innovative “Passport to Comfort” model.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R-01 CA115323).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Statement. Symptom management in cancer: Pain, depression and fatigue. 2002 Available at: http://consensus.nih.gov/ta/022/022_statement.htm.

- 2.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: Clinical practice guideline cancer pain management. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleeland C. The impact of pain on the patient with cancer. Cancer. 1984;58:2635–2641. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841201)54:2+<2635::aid-cncr2820541407>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miaskowski C, Dibble SL. The problem of pain in outpatients with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:791–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward S, Hughes S, Donovan H, et al. Patient education in pain control. Supp Care Cancer. 2001;9:148–155. doi: 10.1007/s005200000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward S, Donovan HS, Owen B, et al. An individualized intervention to overcome patient-related barriers to pain management in women with gynecological cancers. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:393–405. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200010)23:5<393::aid-nur6>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pargeon KL, Hailey BJ. Barriers to effective cancer pain management: a review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:358–368. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, et al. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain. 1993;52:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90165-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potter VT, Wiseman CE, Dunn SM, et al. Patient barriers to optimal cancer pain control. Psychooncology. 2003;12:153–160. doi: 10.1002/pon.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCaffery M, Ferrell BR, O’Neil-Page E, et al. Nurses knowledge of opioid analgesic drugs and psychological dependence. Cancer Nurs. 1990;13(1):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Ritchey KJ, et al. The pain resource nurse training program: a unique approach to pain management. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8(8):549–556. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCaffery M, Ferrell BR, Pasero C. Nurses’ personal opinions about patients’ pain and their effect on recorded assessments and titration of opioid doses. Pain Manage Nurs. 2000;1(3):79–87. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2000.9295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabow MW, Hardie GE, Fair JM, et al. End-of-life care content in 50 textbooks from multiple specialties. JAMA. 2000;283:771–778. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrell B, Virani R, Grant M. Analysis of pain content in nursing textbooks. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(3):216–228. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliot TE, Murray DM, Elliot BA, et al. Physician knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: a survey from the Minnesota Cancer Pain Project. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:494–504. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00100-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine. Approaching death: Improving care at the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gee RE, Fins JJ. Barriers to pain and symptom management, opioids, health policy, and drug benefits. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:101–103. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Cancer-related pain version 1. 2004 Available at: http://nccn.org.

- 19.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrell BR, Hassey-Dow K, Leigh S, et al. Measurement of the QOL in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodd MJ, Miaskowski C, Paul SM. Symptom clusters and their effect on the functional status of patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gift AG, Jablonski A, Stommel M, Given CW, et al. Symptom clusters in elderly patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:202–212. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.202-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Chan J, Ahn C, Ferrell BA. The impact of cancer pain education on family caregivers of elderly patients. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:1211–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrell BR, Rhiner M, Cohen M, Grant M. Pain as a metaphor for illness. Part I: impact of cancer pain on family caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:1303–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrell BR, Cohen M, Rhiner M, Rozek A. Pain as a metaphor for illness. Part II: family caregivers’ management of pain. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:1315–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrell BR, Rhiner M, Rivera LM. Development and evaluation of the family pain questionnaire. J Psych Oncol. 1993;10:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston-Taylor E, Ferrell BR, Grant M, Cheyney L. Managing cancer pain at home: The decisions and ethical conflicts of patients, family caregivers, and homecare nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1993;20:919–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrell B, Taylor E, Sattler G, Fowler M, Cheyney L. Searching for the meaning of pain. Cancer Pract. 1993;1:185–194. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Borneman T, Juarez G, Veer A. Family caregiving in cancer pain management. J Palliat Med. 1999;2:185–195. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Randall-David E, Wright J, Porterfield DS, Lesser G. Barriers to cancer pain management: home health and hospice nurses and patients. Supp Care Cancer. 2003;11:660–665. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0497-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paice JA, Toy C, Shott S. Barriers to cancer pain relief: fear of tolerance and addiction. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward S, Donovan HS, Owen B, et al. An individualized intervention to overcome patient-related barriers to pain management in women with gynecological cancers. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:393–405. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200010)23:5<393::aid-nur6>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miaskowski C, Dodd M, West C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a self-care intervention to improve cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1713–1720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrell BR, Rhiner M, Ferrell BA. Development and implementation of a pain education program. Cancer. 1993;72:3426–3432. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11+<3426::aid-cncr2820721608>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]