Abstract

Background

Asthma is a leading cause of pediatric hospitalizations across the country yet no clinical instrument exists that incorporates the child’s perception of dyspnea in determining discharge readiness.

Objective

We sought to develop a Pediatric Dyspnea Scale (PDS) to support discharge decision-making in hospitalized asthmatic patients, and to compare the performance of PDS with traditional markers of asthma control in predicting outcomes after discharge.

Methods

Asthmatic children aged 6 to 18 years hospitalized for an exacerbation were included in the study. The PDS score, demographics, asthma severity, spirometry, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) and exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) were assessed at the time of discharge. A telephone-call 14 days after discharge determined relapse, activity limitation, asthma control and asthma-related quality of life outcomes.

Results

Eighty-nine subjects were enrolled of whom 70 completed the phone follow-up. Eight patients had a relapse and 29 complained of limited activity. A PDS score above 2 on the 7-point scale was a significant predictor of these poor outcomes, with each additional point of the PDS doubling the risk. A higher score on PDS also correlated with worse asthma control and poor asthma-specific quality of life. The PDS performed better than FEV1, PEFR or FENO in predicting the outcomes of interest.

Conclusion

The PDS, which is easy to use in children as young as 6 years of age, may be able to predict adverse outcomes after hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation, and should be used as a tool to help guide inpatient discharge decisions.

Keywords: asthma, discharge, dyspnea, hospitalized, outcome, pediatric, scale, spirometry, symptoms, exhaled nitric oxide

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a leading cause of chronic illness among children in the United States. Almost nine percent of American children suffer from asthma, nearly two-thirds of whom have experienced at least one asthma attack in the preceding year.1, 2 Asthma annually causes an average of 20 days of restricted activity per asthmatic child, including 10 days of missed school, a disease-related burden that is almost twice that of children afflicted with other chronic disorders.3 Three percent of all pediatric hospitalizations nationwide are asthma-related.1 Over 2.5 billion dollars a year are spent on asthma management, with hospitalizations accounting for a significant proportion of that cost.4

A well-accepted definition of relapse after discharge from the hospital is the need for unscheduled medical care,5 such as repeat hospitalization or a return to the Emergency Department (ED). A lack of relapse has traditionally been looked at as a measure of successful inpatient treatment. Therefore determining the appropriate time for discharge is a cornerstone of inpatient asthma management. This determination has typically relied upon physical examination findings,6, 7 subjective symptoms,8, 9 pulse oximetry,10 peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR)9, 11 and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).12 Even a constellation of these measures however cannot consistently predict which patients will suffer a relapse after discharge.13

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines recommend using patient symptoms as one of the criteria for discharge decisions.14 A modified Borg scale has been successfully used to assess dyspnea in adult patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,8 but children may have comprehension difficulties with this scale. Pianosi and McGrath have published the Dalhousie Dyspnea Scale to assess dyspnea during bronchoconstriction,15, 16 but this has not been evaluated in an acute clinical setting. To our knowledge there is no published clinical instrument for the inpatient management of acute pediatric asthma which incorporates a validated dyspnea assessment tool.

The objective of our study was to determine the usefulness of a Pediatric Dyspnea Scale (PDS), reported for the first time here, as an instrument for making discharge decisions. A secondary objective was to determine how the PDS compared with other measurements for prediction of poor outcome (relapse, activity limitation, a decline in asthma control and poor asthma-related quality of life) at 14 days after discharge.

METHODS

Study Population

Children aged 6 to 18 years of age with a physician diagnosis of asthma admitted to Children’s Hospital of Michigan (CHOM) in Detroit for an asthma exacerbation were eligible for the study. Subjects were enrolled between March 1 and October 15, 2007. Exclusion criteria included patients discharged from the ED after acute management of asthma, pneumonia requiring antibiotics, chronic diseases other than asthma or developmental delay such that required measurements and questionnaires could not be completed. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and patients were enrolled after written informed consent was obtained.

All subjects were managed by the CHOM Asthma Service comprised of an allergist, an allergy fellow-in-training, an asthma nurse educator and a dedicated social worker. Patients received standardized treatment in accordance with NIH guidelines for care in the hospital which included systemic corticosteroid administration.17 All measurements were performed by two research assistants not part of the CHOM Asthma Service. The CHOM Asthma Service personnel were not privy to study data.

Study Protocol

At the time of discharge

Subjects were approached and enrolled on the day of discharge. Discharge decisions were made by the CHOM Asthma Service, and members of the research team were not involved in discharge decision making. At discharge, demographic and historical data were collected from the subjects, their parents/guardians, or the medical record. Demographics included age, race/ethnicity and gender. Historical asthma information included number of prior hospitalizations, ED visits, and courses of oral corticosteroids in the preceding year, as well as the need for intensive care unit (ICU) admissions or intubations ever. Asthma severity based on 2002 NIH/NAEPP guidelines was also determined.17

At the time of discharge, the parent or guardian was asked to provide a ‘Parental Assessment’ of the subject’s asthma symptoms at that moment measured on an ordinal scale from 1 through 4 (very well controlled, somewhat controlled, not very controlled, or not controlled at all). Subjects were asked to rate the degree of their breathlessness on the PDS (described below). Airway inflammation was assessed by measuring fraction of exhaled nitric oxide18 (FENO). This was followed by measurement of airflow limitation by spirometry and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR).

Development of the Pediatric Dyspnea Scale

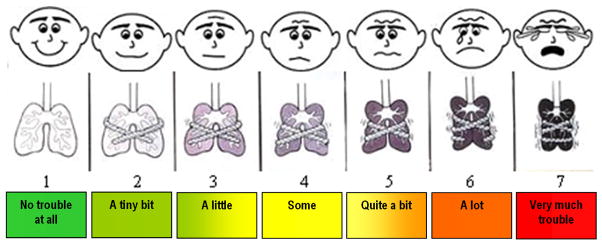

We developed the Pediatric Dyspnea Scale (PDS) (Figure 1) to determine a subjective rating of the subject’s symptoms. The PDS asks the subject “How much trouble breathing are you having?” The scale incorporates three components: (1) a faces scale similar to the Wong-Baker scale19 to estimate an overall sense of wellness or discomfort, (2) a “chest tightness” graphic adapted with permission from the Dalhousie Dyspnea Scale,15 and (3) a series of color-coded descriptions of the extent of breathing difficulties. The PDS is scored from 1 through 7 where 1 indicates “No trouble at all” breathing and 7 indicates “Very much trouble.” Subjects chose one column of responses based on what most closely matched their asthma symptoms and a score of 1 through 7 was assigned accordingly.

Figure 1.

Pediatric Dyspnea Scale. Each subject is asked to answer the question “How much difficulty are you having breathing?” by choosing the column that best corresponds to his or her perceived symptoms

Face validity of the PDS was assessed first by showing the scale to a group of 10 individuals including physicians, nurses and parents. This group felt that the PDS was adequately designed to measure an asthmatic child’s perception of respiratory symptoms.

Measurement of Exhaled Nitric Oxide

Subjects performed FENO measurements using the NIOX MINO Airway Inflammation Monitor (NIOX, MINO; Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden) at least one hour after albuterol inhalation and prior to performing spirometry. Multiple attempts were allowed until three acceptable readings were detected by the device, a mean of which was used for analysis. The device was set on the 6-second mode, which is recommended by the manufacturer for children less than 130 cm tall or those having difficulties with longer exhalations.20 The NIOX MINO has previously shown excellent correlation with traditional nitric oxide analyzers21 and reproducibility in hospitalized children with acute asthma. 22

Measurement of FEV1 and PEFR

Subjects were asked to perform forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) using the Puritan Bennett Renaissance II portable spirometer (Puritan-Bennett, Wilmington, MA) in accordance with American Thoracic Society (ATS) standards.23, 24 Because the subjects were suffering from an asthma exacerbation, ATS recommendations of up to eight spirometric measurements were not followed. Instead, three maneuvers were recorded, and the best value was chosen. FEV1 percent predicted was calculated based on Wang and Dockery standards.25 Three PEFR readings were obtained using the Airlife Asthma Check peak flow meter, and the best value was again chosen for analysis.

Phone follow-up 14 days after discharge

Parents of the subjects received a telephone call at 14 days after discharge, and the status of four identified outcomes was assessed. Relapse was defined as the need for an additional course of oral corticosteroids, return visit to the ED, repeat hospitalization, or an unscheduled physician visit. Limited activity was defined as answering “yes” to the question “Has your child’s asthma limited him/her in any way since discharge from the hospital?” Asthma control and asthma quality of life were measured on two standardized questionnaires, the pediatric Asthma Control Test (ACT) and the Integrated Therapeutics Group Child Asthma Short Form (ITG-CASF). The pediatric ACT is scored on a scale from 0 – 27, with higher numbers indicating greater control.26 The ITG-CASF is a 10-item, asthma-specific quality-of-life score (0 – 100) which assesses daytime and nighttime symptoms as well as functional limitation.27 A higher number indicates better asthma quality of life. Parents were asked to respond to the questions, unless they felt the child would be able to provide more accurate answers.

Statistical Analysis

The outcome variables relapse and limited activity were both scored as dichotomous. All demographic, historical, and measured data were used as potential predictors. On univariate analysis, associations between outcomes and continuous or categorical predictors were assessed using point-biserial or chi-square analysis, respectively. Differences between the groups were assessed using a Mann-Whitney U analysis for continuous predictor variables. Next, any factor correlated with the outcome at a significance level of < 0.20 was entered into a logistic regression model using backward selection.

The outcome variables of asthma control (measured with the ACT) and asthma quality of life (measured with the ITG-CASF) were both scored as continuous. On univariate analysis, associations between these outcomes and continuous and categorical predictors were assessed using a Pearson correlation coefficient or ANOVA, respectively. Next, any factor related to these outcomes at a significance level < 0.20 was entered into a linear regression model using backward selection. Given that a priori we strongly hypothesized higher scores on the PDS would be associated with worse outcomes, all analyses using the PDS were done using one sided tests of the null hypothesis. All statistics were performed using SPSS Version 15 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

One-hundred sixty five pediatric asthmatic patients were screened at the time of discharge. Of these, 60 (36.4%) did not meet eligibility criteria (42 had pneumonia requiring antibiotics and 18 were discharged after hours) and 16 (9.7%) refused to participate. Demographic information for the 89 subjects who were enrolled is presented in Table I.

Table I.

Subject characteristics, n = 89

| Demographics | |

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 10.9 (3.4) |

| Sex, Male, n (%) | 58 (65.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black | 83 (91.4) |

| White | 3 (3.4) |

| Arabic | 2 (2.2) |

| Other | 1 (1.1) |

| Asthma characteristics | |

| Asthma severity classification, n (%) | |

| Mild intermittent | 18 (20.2) |

| Mild persistent | 25 (28.1) |

| Moderate persistent | 24 (27.0) |

| Severe persistent | 22 (24.7) |

| Previous ICU admission, n (%) | 20 (22.5) |

| Previous intubation, n (%) | 8 (9.0) |

| ED visits in past 1 year, n (%) | |

| 0 | 28 (31.5) |

| 1–2 | 34 (38.2) |

| 3–7 | 24 (26.9) |

| >8 | 3 (3.4) |

| Hospitalizations in past 1 year*, n (%) | |

| 0 | 56 (62.9) |

| 1–2 | 26 (29.2) |

| 3–6 | 7 (7.9) |

| Days in hospital prior to discharge, Mean (SD) | 2.2 (0.74) |

Abbreviations: ED, Emergency Department; SD standard deviation; ICU, intensive care unit.

Hospitalizations in past year excludes current admission

Measured parameters

Mean values of the measured parameters are listed in Table II. Thirteen subjects were unable to perform acceptable FENO measurements despite allowance of multiple attempts. Therefore the mean FENO measurement of 38.4 parts per billion (ppb) is based on 76 subjects. FENO measurements ranged from 6 to 194 ppb. The mean FEV1 percentage of predicted was 55.2 %, indicative of moderate airway obstruction. PEFR readings ranged from 70 to 580 liters/minute (L/min) with a mean of 239 L/min. A mean of the Parental Assessment responses was 1.91 whereas the mean of responses chosen on the PDS was 2.17.

Table II.

Measured parameters, n = 89*

| Parameter | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| FENO (ppb) | 38.4 | 29.4 |

| FEV1 (L/min) | 1.31 | 0.90 |

| FEV1 percentage of predicted (%) | 55.2 | 23.4 |

| PEFR (L/min) | 239.0 | 98.9 |

| Parental Assessment | 1.91 | 0.67 |

| Pediatric Dyspnea Scale | 2.17 | 1.05 |

For FENO, n = 76

Abbreviations: FENO, Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide; ppb, parts per billion; FEV1, Forced expiratory Volume in 1 second; L/min, liters/minute; PEFR, Peak expiratory Flow Rate; SD standard deviation

Telephone follow-up at 14 days

Seventy subjects (78.6%) completed the study by participating in the day-14 telephone follow-up call. Baseline and measured characteristics of the 19 who were lost to follow-up and the 70 who were contacted were compared. Parental assessment of poor asthma control at the time of discharge for those lost to follow-up was slightly higher (2.1 vs 1.9), and this approached significance with a p-value of 0.056. The remaining characteristics showed no difference, including no difference for responses on the PDS.

Factors associated with relapse

Of the 70 patients who were reached for follow-up, 8 (11.4%) experienced a relapse. On univariate analysis, only the PDS was significantly associated with relapse, although ED visits in the previous year trended towards significance (P = 0.14). The PDS score was 2.6 in children who experienced a relapse compared to 1.9 in those who did not (P = 0.027). After controlling for other factors, the odds of suffering a relapse approximately doubled for each additional point on the PDS (OR 2.04, P = 0.033).

Factors associated with limited activity

Twenty-nine (32.6%) of the 70 children had limited activity secondary to persistent asthma symptoms after discharge. On univariate analysis, the PDS was significantly associated with activity limitation. Children who complained of activity limitations after discharge had a higher score on the PDS compared to those who did not (2.3 vs. 1.8, P = 0.030). After controlling for other factors, the odds ratio for having limited activity was 1.7 times greater for each additional point on the PDS (OR = 1.66, P = 0.034).

Factors associated with decreased asthma control after discharge

Asthma control was assessed using the Asthma Control Test. The mean ACT score at 14 days was 21.7 (95% CI 20.7 – 22.6). On univariate analysis, the PDS, number of asthma ED visits in the previous year, asthma severity as determined by NIH category, and the any previous requirement for asthma-related ICU care were all associated with a lower ACT score. Factors associated with the ACT on univariate analysis were entered into the multivariable regression model. As shown in Table III, factors that remained significantly associated with poor asthma control on the ACT included the PDS, an increased number of ED visits in the previous year, and a history of requiring ICU care for asthma (overall R2 = 0.207, P = 0.002).

Table III.

Factors associated with the ACT and ITG-CASF after discharge

| Outcome | Factor | Regression Coefficient (B) | SE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | PDS | −0.770 | 0.449 | 0.046 |

| 1-Yr ED | −0.315 | 0.158 | 0.050 | |

| ICU | −2.711 | 0.974 | 0.007 | |

| ITG-CASF | PDS | −4.202 | 2.163 | 0.028 |

Abbreviations: ACT, Asthma Control Test; ITG-CASF, Integrated Therapeutics Group-Child Asthma Short Form; PDS, Pediatric Dyspnea Scale; 1-yr ED, Number of Emergency Department visits in the last year; ICU, Ever required admission to the Intensive Care Unit SE standard error

Factors associated with decreased asthma quality of life after discharge

Asthma-related quality of life was measured using the ITG-CASF. The mean ITG-CASF score at 14 days was 86.3 (95% CI 82.1 – 90.4). On univariate analysis, the ITG-CASF was positively correlated with female gender and FEV1 percent predicted, and negatively correlated with the PDS. Factors associated with the ITG-CASF on univariate analysis were entered into the multivariable regression model. As shown in Table III, only the PDS remained significantly correlated with the ITG-CASF (overall R2 = 0.051, P = 0.033).

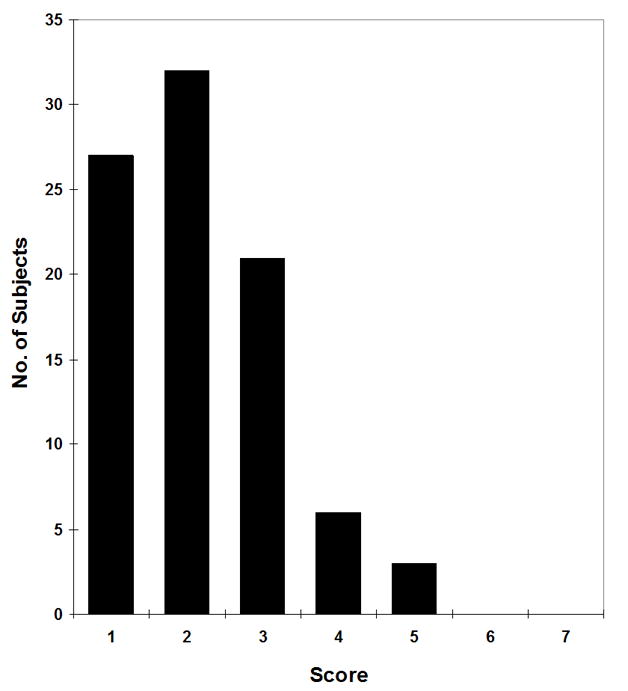

Validity of the Pediatric Dyspnea Scale

Figure 2 shows a frequency graph of the subjects’ responses on the PDS. The most frequently chosen response was 2, which was described as “A tiny bit” of trouble breathing. Predictive validity (the extent to which the PDS predicts multiple outcomes), was assessed. As shown in Table IV, the PDS was significantly associated with all outcomes measured in this study. For the two dichotomous outcomes (relapse and limited activity), the odds ratios indicate the increased odds of the specified outcome for each additional point on the PDS. For the two continuous outcomes (ACT and ITG-CASF), the regression coefficients indicate a negative correlation between the PDS and quality of life/asthma control outcomes. Of note, the PDS did not correlate with any of the measured parameters from Table II (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Responses on the Pediatric Dyspnea Scale (n = 89). Bars show the number of subjects who chose each column. A value of 1 indicates no trouble at all with breathing while 7 indicates very much trouble.

Table IV.

Association of the Pediatric Dyspnea Scale with outcome measures

| Outcome | Odds ratio | Beta | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 2.04 | 0.033 | |

| Activity Limitation | 1.66 | 0.034 | |

| ITG-CASF | −4.202 | 0.028 | |

| ACT | −0770 | 0.046 |

Abbreviations: ACT, Asthma Control Test; ITG-CASF, Integrated Therapeutics Group – Child Asthma Short Form, PDS; Pediatric Dyspnea Scale

Discussion

NIH criteria recommend including patient symptoms among the criteria for discharge decisions.14 This approach seems appropriate, as continuing or recurrent symptoms are often major factors driving decisions to seek further medical care. Currently, however, no instrument for assessing asthma symptoms in an acute-care setting has been validated for the pediatric population. This lack led us to develop the Pediatric Dyspnea Scale, whose validation we report here.

The Visual Analog, Likert and the modified Borg scales have been evaluated in aduts28 but were not designed for and have not been successfully studied in children. The Dalhousie scale is validated only for children 8 years of age and older and its effectiveness in a clinical setting has yet to be determined.15, 16 This scale requires the understanding and ability to decipher three physical constructs related to dyspnea: exhaustion, chest tightness and throat constriction. It also is mounted on a large poster board with three sliding cursors, and has multiple subscales that must be individually completed, making it potentially burdensome in a hospital setting.

The PDS incorporates three components. The first is a series of faces showing affect, a measure of overall wellness or discomfort. The second component is the “chest tightness” graphics that had previously been included in the Dalhousie Dyspnea Scale.15 The third is an ordinal series of descriptions of the patient’s difficulty in breathing, which is also color-coded from green to red as a further cue. We hypothesized that a combination of graphics, ordinal scale, words and color gradation of responses help younger children better quantify their symptoms.

The validity of the PDS was established by looking at its relation with the four major outcomes at 14 days post-discharge: relapse, limitation of activity, poor asthma control as measured by the ACT, and asthma related quality of life as measured by the ITG-CASF. These short-term patient-oriented outcomes after an asthma exacerbation provide an important measure of asthma morbidity.29 At the time of discharge, a score of greater than 2 on the PDS was found to be the cutoff above which patients were more likely to suffer a relapse or experience activity limitation. Each additional point on the scale almost doubled the odds of suffering either of these poor outcomes. In addition, worse scores on the ACT or ITG-CASF were also correlated with higher scores on the PDS. In fact, the PDS was the only factor associated with decreased quality of life after discharge.

FEV1 and PEFR have traditionally been looked at as measures of airflow limitation secondary to bronchoconstriction. These measurements have shown reproducibility in adolescents12 but cost, time, effort and difficulty in obtaining these measurements during acute asthma and their questionable utility in guiding management have limited their use.13, 30 FEV1 and PEFR did not correlate with the PDS in our study showing that spirometry measurements and perception of dyspnea are at times unrelated, consistent with previous findings by other investigators.31, 32 Airway inflammation as measured by FENO has shown reproducibility in children as young as 6 years of age but does not correlate with spirometry.33 Similar to FEV1/PEFR measurements, FENO did not correlate with the PDS in our study. However, the PDS was found to be superior in our study as it predicted the outcomes of interest. Future studies are required to assess if the combination of the PDS with other objective measures improves the ability to predict adverse outcomes.

There were limitations to our study. We did not test the PDS in a younger age group, and therefore cannot assess it’s usefulness in children under the age of 6. Serial measurements on the PDS were not determined, either starting from the ED or from admission until discharge in the inpatient unit. We did not follow patients for months or years to assess long term asthma morbidity. A number of subjects refused to participate or were not able to be contacted at follow-up. Not all spirometric measurements met ATS standards as patients were recovering from acute asthma exacerbation. Finally, this study was conducted at an inner city hospital, so the results may not be generalizable to all populations.

In conclusion, the Pediatric Dyspnea Scale is a promising instrument that will assist in clinical decision making for acute pediatric asthmatics. The ease of use in children as young as 6 years of age and a cut-off score of 2 in its ability to predict favorable versus poor outcomes after discharge from the hospital make the PDS an appealing option for health care providers. The usefulness of the PDS in other settings, such as the emergency department and outpatient clinic, remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL070068 (RCR) and the NIH Loan Repayment Program (APB).

Abbreviations/Acronyms

- ACT

sthma Control Test

- CHOM

Children’s Hospital of Michigan

- ED

Emergency Department

- FEV1

Forced Expiratory Volume in one second

- FENO

Fraction of Exhaled Nitric Oxide

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- ITG-CASF

Integrated Therapeutics Group Child Asthma Short Form

- PDS

Pediatric Dyspnea Scale

- PEFR

Peak Expiratory Flow Rate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Farah I. Khan, Carman and Ann Adams Department of Pediatrics, Division of Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI.

Raju C. Reddy, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Alan P. Baptist, Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

References

- 1.Akinbami L. The state of childhood asthma, United States, 1980–2005. Adv Data. 2006 Dec 12;(381):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asthma Prevalence, Health Care Use and Mortality: United States. 2003–05. National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newacheck PW, Halfon N. Prevalence, impact, and trends in childhood disability due to asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Mar;154(3):287–293. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang LY, Zhong Y, Wheeler L. Direct and indirect costs of asthma in school-age children. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005 Jan;2(1):A11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benito-Fernandez J. Short-term clinical outcomes of acute treatment of childhood asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 Jun;5(3):241–246. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000168788.97453.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kesten S, Maleki-Yazdi R, Sanders BR, et al. Respiratory rate during acute asthma. Chest. 1990 Jan;97(1):58–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendrick KR, Baxi SC, Smith RM. Usefulness of the modified 0–10 Borg scale in assessing the degree of dyspnea in patients with COPD and asthma. J Emerg Nurs. 2000 Jun;26(3):216–222. doi: 10.1016/s0099-1767(00)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khasnis A, Lokhandwala Y. Clinical signs in medicine: pulsus paradoxus. J Postgrad Med. 2002 Jan-Mar;48(1):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karras DJ, Sammon ME, Terregino CA, Lopez BL, Griswold SK, Arnold GK. Clinically meaningful changes in quantitative measures of asthma severity. Acad Emerg Med. 2000 Apr;7(4):327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly AM, Kerr D, Powell C. Is severity assessment after one hour of treatment better for predicting the need for admission in acute asthma? Respir Med. 2004 Aug;98(8):777–781. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarren M, Zalenski RJ, McDermott M, Kaur K. Predicting recovery from acute asthma in an emergency diagnostic and treatment unit. Acad Emerg Med. 2000 Jan;7(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman RA, Flaster E, Enright PL, Simonson SG. FEV1 performance among patients with acute asthma: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Chest. 2007 Jan;131(1):164–171. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markoff BA, MacMillan JF, Jr, Kumra V. Discharge of the asthmatic patient. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001 Jun;20(3):341–355. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:20:3:341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Full Report 2007. 2007.

- 15.McGrath PJ, Pianosi PT, Unruh AM, Buckley CP. Dalhousie dyspnea scales: construct and content validity of pictorial scales for measuring dyspnea. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pianosi P, Smith CP, Almudevar A, McGrath PJ. Dalhousie dyspnea scales: Pictorial scales to measure dyspnea during induced bronchoconstriction. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006 Dec;41(12):1182–1187. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma Update on Selected Topics--2002. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002 Nov;110(5 Suppl):S141–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strunk RC, Szefler SJ, Phillips BR, et al. Relationship of exhaled nitric oxide to clinical and inflammatory markers of persistent asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003 Nov;112(5):883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong DL, Baker CM. Smiling faces as anchor for pain intensity scales. Pain. 2001 Jan;89(2–3):295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NIOX MINO User Manual, Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden. 2005.

- 21.Alving K, Janson C, Nordvall L. Performance of a new hand-held device for exhaled nitric oxide measurement in adults and children. Respir Res. 2006;7:67. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baptist AP, Khan FI, Wang Y, Ager J. Exhaled nitric oxide measurements in hospitalized children with asthma. J Asthma. 2008 Oct;45(8):670–674. doi: 10.1080/02770900802140207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide 2005. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Apr 15;171(8):912–930. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005 Aug;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Dockery DW, Wypij D, Fay ME, Ferris BG., Jr Pulmonary function between 6 and 18 years of age. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1993 Feb;15(2):75–88. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950150204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Jan;113(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorelick MH, Brousseau DC, Stevens MW. Validity and responsiveness of a brief, asthma-specific quality-of-life instrument in children with acute asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004 Jan;92(1):47–51. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant S, Aitchison T, Henderson E, et al. A comparison of the reproducibility and the sensitivity to change of visual analogue scales, Borg scales, and Likert scales in normal subjects during submaximal exercise. Chest. 1999 Nov;116(5):1208–1217. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens MW, Gorelick MH. Short-term outcomes after acute treatment of pediatric asthma. Pediatrics. 2001 Jun;107(6):1357–1362. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson MM, Irwin RS, Connolly AE, Linden C, Manno MM. A prospective evaluation of the 1-hour decision point for admission versus discharge in acute asthma. J Intensive Care Med. 2003 Sep-Oct;18(5):275–285. doi: 10.1177/0885066603256044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Killian KJ, Summers E, Watson RM, O’Byrne PM, Jones NL, Campbell EJ. Factors contributing to dyspnoea during bronchoconstriction and exercise in asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 1993 Jul;6(7):1004–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turcotte H, Corbeil F, Boulet LP. Perception of breathlessness during bronchoconstriction induced by antigen, exercise, and histamine challenges. Thorax. 1990 Dec;45(12):914–918. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.12.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baptist APKF, Wang Y, Ager J. Exhaled nitric oxide measurements in hospitalized children with asthma. J Asthma. 2008 doi: 10.1080/02770900802140207. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]