Abstract

Tetraspanin CD82 suppresses cell migration, tumor invasion, and tumor metastasis. To determine the mechanism by which CD82 inhibits motility, most studies have focused on the cell surface CD82, which forms tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs) with other transmembrane proteins, such as integrins. In this study, we found that CD82 undergoes endocytosis and traffics to endosomes and lysosomes. To determine the endocytic mechanism of CD82, we demonstrated that dynamin and clathrin are not essential for CD82 internalization. Depletion or sequestration of sterol in the plasma membrane markedly inhibited the endocytosis of CD82. Despite the demand on Cdc42 activity, CD82 endocytosis is distinct from macropinocytosis and the documented dynamin-independent pinocytosis. As a TEM component, CD82 reorganizes TEMs and lipid rafts by redistributing cholesterol into these membrane microdomains. CD82-containing TEMs are characterized by the cholesterol-containing microdomains in the extreme light- and intermediate-density fractions. Moreover, the endocytosis of CD82 appears to alleviate CD82-mediated inhibition of cell migration. Taken together, our studies demonstrate that lipid-dependent endocytosis drives CD82 trafficking to late endosomes and lysosomes, and CD82 reorganizes TEMs and lipid rafts through redistribution of cholesterol.—Xu, C., Zhang, Y. H., Thangavel, M., Richardson, M. M., Liu, L., Zhou, B., Zheng, Y., Ostrom, R. S., Zhang, X. A. CD82 endocytosis and cholesterol-dependent reorganization of tetraspanin webs and lipid rafts.

Keywords: cell migration, membrane microdomain, protein trafficking, sterol lipid

Tetraspanins are a superfamily of type III transmembrane proteins and can be found in evolutionarily distant species such as mammals, insects, sponges, and fungi (1). Structurally, all members of the tetraspanin superfamily contain 4 transmembrane domains and several conserved signature amino acid residues. These residues include an absolutely conserved CCG motif and 4 to 6 cysteine residues that form 3 to 3 crucial disulfide bonds within the second extracellular loop (2, 3). Tetraspanins form large transmembrane complexes called tetraspanin webs or tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs), in which tetraspanins associate with a variety of transmembrane and intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal proteins (4, 5). Functionally, tetraspanins regulate an array of physiological functions, such as cell adhesion, cell fusion, cell motility, and cell signaling (6,7,8).

Tetraspanin CD82/KAI1, a suppressor of tumor metastasis (9), directly inhibits cell motility and cancer invasiveness (10,11,12,13,14,15,16). Although the underlying mechanism for CD82-mediated inhibition of motility remains unclear, recent studies suggest that alterations in the membrane compartmentalization and/or the functional status of CD82-associated molecules are involved. For example, a fraction of CD82 localizes in ganglioside/cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains (membrane rafts or lipid rafts), and the partition of CD82 into membrane rafts is regulated by actin cytoskeleton and its own antibody (Ab) engagement (17). The disruption of membrane rafts by cholesterol removal overturns CD82-induced actin reorganization and signaling in T cells (17). In addition, CD82 expression causes the redistribution of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and ErbB2 into membrane rafts, and this recompartmentalization correlates with the increased levels of gangliosides GD1a and GM1 (a membrane raft component) in plasma membrane (13). Moreover, ganglioside GD1a reciprocally regulates the interactions of CD82 with other tetraspanins and EGFR in TEMs, indicating the involvement of gangliosides in the formation of CD82-containing TEMs (18). Finally, cholesterol and ganglioside GM2 interact with CD82 and the GM2-CD82 interaction inhibits the activation of c-Met (19). Together, the relationships between CD82 and ganglioside/cholesterol strongly suggest that the functional interaction of TEMs and membrane rafts play a role in the motility-inhibitory function of CD82.

Endocytosis is involved in the uptake of extracellular nutrients, the regulation of cell-surface receptor expression, the homeostasis of cellular cholesterol, the maintenance of cell polarity, the presentation of antigen, and many other physiological processes (20). Endocytosis occurs by various mechanisms that fall into two broad categories: phagocytosis (the uptake of large particles) and pinocytosis (the uptake of fluid and solutes). Pinocytosis can be further classified into at least four basic mechanisms: macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae-mediated endocytosis, and clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytosis (21). The clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytosis actually includes a group of poorly defined endocytic mechanisms, and lipid rafts are required for some clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytosis (22,23,24,25). Membrane molecules are internalized typically via a major mechanism, but notably some can be internalized via different routes, which lead to different fates for the internalized molecules. For example, transforming growth factor-β receptor is involved in receptor signaling when internalized through the clathrin-mediated route; however, it is ubiquitinated and degraded if endocytosed through the caveolae pathway (26).

Besides plasma membrane, CD82 is also present in intracellular vesicles (27, 28). Interestingly, a recent study showed that CD82-containing TEMs serve as a gateway for HIV-1 cellular entry (29), indicating that CD82 could be internalized. In accordance with the notion of CD82 endocytosis, tetraspanins such as CD63, CD82, Net-1, CD37, Tspan-3, CD151, A15, TM4SF6, and CO-029 contain a YXXø motif (X represents any amino acid, and ø represents an amino acid with a bulky hydrophobic side chain), the tyrosine-based sorting signal (30,31,32), in their C-terminal cytoplasmic tails. The YXXø motif is recognized by μ subunits of AP adaptor proteins responsible for internalizing clathrin-coated pits and the sorting of intracellular vesicles (30). However, the functions of YXXø motifs remain to be determined for most tetraspanins. In this study, we set forth to determine whether CD82 undergoes endocytosis and, if it does, to characterize the endocytic pathways of CD82 and the functions of CD82 endocytosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies, constructs, and other reagents

The constructs used in this study include green fluorescent protein (GFP)-dynamin wild type and K44A mutant (kindly provided by Dr. M. McNiven, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA); GFP-ARF6 wild type, GFP-ARF6 T27N, and GFP-ARF6 Q67L (kindly provided by Dr. J. Donaldson, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA); and GFP-glycosylphosphatidyl-inositol (GPI) (kindly provided by Dr. A. Kentworth, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA).

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Nocodazole and latrunculin A were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

CD82 monoclonal antibody (mAb) M104 and integrin β1 mAb TS2/16 were obtained from Dr. M. Hemler (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA). CD82 mAb 4F9 was provided by Dr. S. Iwata and Dr. T. Ishii (Dr. C. Morimoto’s laboratory, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). CD82 mAb TS82b was either obtained from Dr. Eric Rubinstein (INSERM U268, Villejuif, France) or purchased from Diaclone (Besancon, France). Mouse IgG2b was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. Rab4 mAb, Rab11 mAb, and flotillin mAb were purchased from BD Biosciences (Mountain View, CA, USA). Rab5b polyclonal antibody (pAb), caveolin-1 pAb (N-20), and major histocompatability complex (MHC) class I mAb (W6/32) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). FITC-conjugated CD63 mAb was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA, USA). FITC- or rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was purchased from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA, USA). Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin and Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA).

Cell culture and transfectants

Du145 cells stably expressing CD82 (Du145-CD82) were established in the laboratory as described previously (15, 33, 34). Du145 transfectant cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). U937 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA); cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen); and differentiated by the PMA (100 nM) treatment for 48 h. PrEC-NH cells (10) were kindly provided by Dr. William Hahn (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) and cultured in PrEBM (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD, USA). For transient transfection, cells were transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Endocytosis assay

For antibody-probed endocytosis, cells at ∼50% confluence were incubated with mAbs at 4°C for 1 h. After 3 washes with ice-chilled PBS, the cells were replenished with prewarmed serum-free medium and incubated at 37°C for the indicated periods of time. The antibodies bound to the cell surface but not internalized were removed by 3 washes with 0.1 M glycine and 0.1 M NaCl solution (pH 2.5), followed by fixation with 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature (RT). After being permeabilized with 0.1% Brij 98 for 2 min, the cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody at 37°C for 1 h, followed by 4 washes with PBS. The internalized proteins were assessed using fluorescent or confocal microscopy.

For transferrin uptake, cells were incubated with Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin at 37°C for 5 min, followed by the steps described above.

For the flow cytometry-based endocytosis assay, cells were detached, incubated with FITC-conjugated mAb or ligand at 4°C for 1 h, and then switched to 37°C for different periods of time for internalization. After acidic washes, the cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and subsequently analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The percentages of internalized membrane molecule were calculated with the formula [mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the internalized membrane molecule at a given time point − MFI of the internalized membrane molecule at time 0]/MFI of the total surface level of the membrane molecule × 100%.

Immunofluorescent and confocal microscopy

Cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde-PBS at RT for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Brij 98-PBS for 2 min. Cells were sequentially incubated with the primary mAb and fluorochrome-conjugated secondary Ab at RT for 1 h, respectively. Cells were analyzed with either a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), a Bio-Rad 1024 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), or an LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) as described previously (35). For confocal microscopic analysis, cell samples were visualized using single-line excitation at 488 or 555 nm for GFP or Alexa 594, respectively, with appropriate emission filters. In each experiment, ∼70–100 cells were analyzed for each treatment, and each experiment was performed ≥3 times.

Cellular fractionation

For the fractionation by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation, ∼90% confluent Du145 transfectant cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated in 2 ml of TNE buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; and 1 mM EDTA) that contained 1% Lubrol WX at 4°C for 2 min (36). The cells were then scraped and homogenized in an ice-cold, loose-fitting, Teflon-glass homogenizer using 20 strokes. Cell homogenate (2 ml) was mixed with an equal volume of 80% sucrose in TNE buffer and overlaid with discontinuous sucrose gradients (5 ml of 30% sucrose and 1 ml of 5% sucrose in TNE buffer). The samples were centrifuged for 21 h at 35,000 rpm at 4°C in a SW41Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA), equivalent to a maximum force of ∼210,000 g and an average force of ∼151,000 g. At the completion of the centrifugation, a faint light-scattering band, consisting of the buoyant lipid raft/caveolar materials, was often visible at the interface of 30 and 5% sucrose gradients. Fractions were collected by sequentially removing 1-ml aliquots from the top.

For the separation of the plasma membrane and cytoplasmic fractions, ∼80% confluent Du145 transfectant cells were washed once with PBS and incubated in 1 ml of membrane separation buffer that contained 0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine (tricine), and 1 mM EDTA. The cells were then scraped and homogenized in an ice-cold Dounce homogenizer with 20 strokes. After centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min to remove the insoluble materials, the supernatant was layered on the top of 30% Percoll (Fluka AG, Buchs, Switzerland) and centrifuged at 64,000 g for 30 min. The opaque band near the top of the Percoll layer was collected as the plasma membrane fraction, and the rest of the soluble material down from the band was collected as the cytoplasmic fraction.

Cell migration

For the wound-healing assay, cells were cultured on Lab-Tek chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA). After cell monolayers were formed, they were scraped by the sterile pipette tips to produce a wound. The cells were then rinsed once with PBS and replenished with the complete medium containing mAb. After overnight culture at 37°C, the cells were fixed and photographed under an inverted light microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA).

For the transwell chemohaptotactic cell migration assay (37), cells were trypsinized, counted, and replated into the 8-μm pore size Transwell inserts (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA). The underside of the inserts was coated with 20 μg/ml laminin 1. A total of 1 × 104 cells in serum-free DMEM medium containing 0.1% heat-inactivated BSA in a volume of 300 μl were added into each insert, and 500 μl of DMEM medium containing 1% FBS was added to the lower chamber. The cells in the Transwell plates were incubated at 37°C for 12 h. Cells that remained in the inserts were removed with a cotton swab, and cells that migrated through the pores to the underside of the inserts were fixed and stained with Diff-Quick (Baxter Healthcare, McGraw Park, IL, USA). The transmigrated cells were counted from randomly selected microscopic fields, and cell migration is presented as the average number of transmigrated cells per ×10 microscopic field.

Cholesterol quantification

The sucrose gradient fractions were prepared and collected from the 1% Lubrol WX cell lysates as described above. The total cholesterol, i.e., free cholesterol and cholesterol ester, in each fraction was quantified by using the Invitrogen Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit and following the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

A 2-tailed Student’s t test was used for all statistical analyses in this study. Values of P < 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Endocytosis of CD82 into endosomal and lysosomal compartments

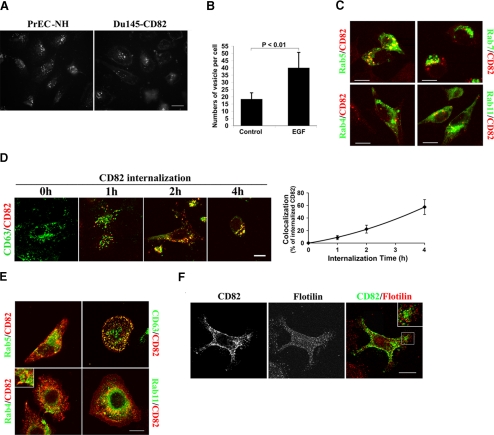

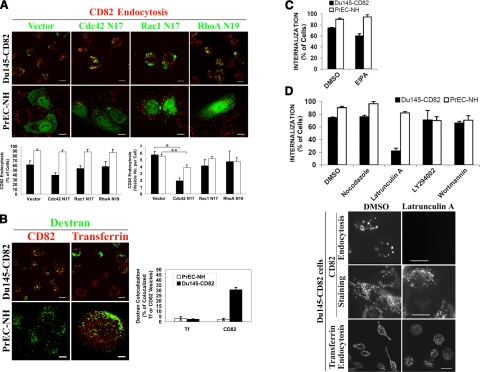

Most studies on CD82 focus on the structure and function of CD82 proteins at the plasma membrane. CD82 is, however, also found in intracellular vesicular compartments in hematopoietic cells (27, 28). Distribution of CD82 on the cell surface as well as in intracellular vesicles strongly suggests that CD82 traffics between the plasma membrane and intracellular vesicular compartments. To determine whether CD82 undergoes endocytosis, we analyzed CD82 internalization by using the prostate epithelial cell line, PrEC-NH, which is an immortalized human prostate line (37) and constitutively expresses CD82 (Fig. 1A), and the CD82 stable transfectant of Du145 prostate cancer cells (10). Using an Ab uptake assay, we found that CD82 was readily internalized into intracellular vesicles in both cell lines (Fig. 1A). The internalization of CD82 exhibited a slow pace in Du145-CD82. Internalization plateaued in ∼120–180 min (t1/2 was ∼60 min) when the whole Ig molecule of CD82 mAb TS82b was used as a probe (Supplemental Fig. 1A). We also measured CD82 internalization kinetics using the antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of this mAb and found no significant difference between whole Ig and Fab fragment (Supplemental Fig. 1). Interestingly, growth factors such as EGF markedly enhanced CD82 endocytosis (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

CD82 endocytosis and the vesicular compartments through which CD82 traffics. A) Internalization of CD82. Du145-CD82 or PrEC-NH cells were incubated with CD82 mAb TS82b at 4°C for 1 h, followed by PBS washes to remove unbound mAb. Then the cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min for internalization, followed by acidic washes to remove noninternalized mAb. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with the second Ab. Digital images were captured by fluorescence microscopy. B) CD82 endocytosis was analyzed in PrEC-NH cells in the presence or absence of EGF (40 ng/ml) at 37°C for 1 h as described above. CD82 endocytosis was quantified as the number of CD82-positive vesicles per cell. In each experiment, ∼30 cells were quantified. Bars represent means ± se of 3 experiments. C) Endocytic trafficking of CD82 into endosomes and lysosomes. CD82 endocytosis was analyzed as described above in the Du145-CD82 cells transiently transfected with GFP-Rab4, -Rab5, -Rab7, or -Rab11. D) Accumulation of CD82 in lysosomes after internalization. CD82 endocytoses were analyzed as described above, except with Alexa 594-conjugated CD82 mAb. After CD82 internalization, the cells were fixed and permeabilized and further incubated with FITC-conjugated CD63 mAb. Digital images of a Z-section were obtained by confocal microscopy. Colocalization of CD82 and CD63 was quantitated using LaserSharp 2000 software (Bio-Rad) and is presented as the percentage of internalized CD82. E) Steady-state distribution of CD82 in endosomes and lysosomes. After being fixed and permeabilized, Du145-CD82 cells were incubated with Rab4, Rab5b, or Rab11 mAb, followed by the incubation with the second antibody. For CD63 staining, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated CD63 mAb. After being washed and then blocked with mouse IgG, cells were further incubated with Alexa 594- or 488-conjugated CD82 mAb TS82b at RT for 1 h. F) Colocalization analysis of CD82 and flotillin. Steady-state distributions of cellular CD82 and flotillin were analyzed using their Abs as described above. Digital images of a Z-section were acquired using confocal microscopy. Scale bars = 10 μm.

In higher eukaryotic cells, internalized molecules are typically first delivered to early endosomes (38). In Du145-CD82 cells, more than one-third of internalized CD82 was detected in the Rab5-positive compartment, presumably early and sorting endosomes, after a 30-min endocytosis (Fig. 1C and Table 1). After reaching early endosomes, transmembrane and cell surface molecules could be sorted into late endosomes; and after late endosomes, internalized proteins could be further targeted to lysosomes for degradation. Rab7, a marker of late endosomes, displayed partial colocalization with the internalized CD82 (19%) (Fig. 1C and Table 1). We found that the internalized CD82 already entered the compartment positive in CD63, a marker of lysosomes/late endosomes, after a 30-min endocytosis in Du145-CD82 cells (Table 1). The kinetics analysis showed that more CD82 trafficked into CD63-positive lysosomes/late endosomes when endocytosis was prolonged (Fig. 1D). At the 4-h time point, ∼60% of the internalized CD82 had accumulated in the CD63-positive compartment (Fig. 1D), indicating that the internalized CD82 is destined mainly for the late endocytic compartments. Internalized molecules could also be recycled back to the cell surface (39). Recycling is driven by a distinct subpopulation of endosomes called recycling endosomes (38). Rab4 and Rab11 are the markers for peripheral and perinuclear recycling compartments, respectively (40). We found that ∼10 or 5% of CD82 traffics into Rab11- or Rab4-positive recycling endosomes, respectively, within a 30-min chase period (Fig. 1C and Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Internalization of CD82 into endosomes and lysosomes and the steady-state distribution of CD82 in these compartments

| Compartment | 30-min endocytosis (%) | Steady state (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Early endosome | ||

| Rab5 | 37.1 ± 5.1 | 22.6 ± 3.9 |

| Recycling endosome | ||

| Rab4 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 4.0 ± 2.0 |

| Rab11 | 9.9 ± 2.7 | 14.4 ± 2.8 |

| Late endocytosis | ||

| Rab7 | 19.0 ± 3.0 | Not done |

| LBPA | Not done | 15.5 ± 2.7 |

| CD63 | 14.0 ± 5.6 | 28.9 ± 3.9 |

Colocalizations of CD82 with the markers were quantitated by measuring the colocalized pixel areas in immunofluorescent confocal images through Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). Colocalization is presented as either the percentage of colocalized pixels from internalized CD82 pixels for the 30-min endocytosis or the percentage of colocalized pixels from total CD82 pixels for the steady-state distribution. Results represent averages ± se of 3 individual experiments. Approximately 20 cells were analyzed in each measurement.

To determine the vesicular trafficking of CD82 at the steady state, we assessed the distributions of CD82 in endosomal and lysosomal compartments. Approximately one-fifth to one-fourth of CD82 was found in Rab5-positive early endosomes (Fig. 1E and Table 1), indicating the existence of physiological endocytosis of CD82. For late endosomes, we analyzed the localization of CD82 in multivesicular bodies (MVBs), a special form of late endosomes (38). Earlier studies demonstrated the presence of CD82 in MVBs or MHC II-enriched compartment in B cells (27, 28). Based on the colocalization with lysobiphosphatic acid (LBPA), a specific marker of MVBs (38), we found that ∼16% of intracellular CD82 was compartmentalized in LBPA-positive late endosomes (Table 1). For CD63-positive lysosomes/late endosomes, ∼29% of the CD82 staining, including that at the cell surface and in intracellular vesicles, was colocalized with CD63 in Du145-CD82 cells (Fig. 1E and Table 1). Likewise, CD82 displayed partial colocalization with CD63 in PC3 cells that stably express CD82 (data not shown). For recycling endosomes, we found 14 and 4% colocalizations of CD82 with Rab11 and Rab4, respectively (Fig. 1E and Table 1), comparable to the results from the 30-min chase of CD82 endocytosis (Table 1).

A recent study indicated that flotillin-positive intracellular vesicles represent a type of intermediate endocytic compartment for clathrin-independent endocytosis and flotillin resides in punctate structures at the plasma membrane (41). We found that there is no colocalization between CD82 and flotillin at the steady state in Du145-CD82 cells (Fig. 1F).

Dynamin and clathrin are not required for CD82 internalization

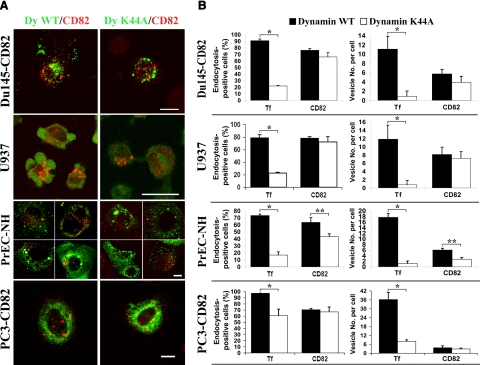

Dynamin II is involved in the formation of both clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) and caveolar vesicles (42,43,44). Expression of a dominant-negative dynamin II mutant (dyn2 K44A) inhibited the internalization of most transferrin (Supplemental Fig. 2A), a hallmark of clathrin-mediated uptake, as expected. However, when dyn2 K44A was expressed in Du145-CD82, U937, PrEC-NH, or PC3-CD82 cells, the internalization of CD82 was not markedly affected in Du145-CD82, U937, and PC3-CD82 cells but was reduced in PrEC-NH cells (Fig. 2A). Quantitative analysis revealed that no statistically significant difference in CD82 endocytosis was found between the dynamin wild type- and K44A mutant-expressing Du145-CD82, U937, or PC3-CD82 cells (Fig. 2B). In PrEC-NH cells, we found that the K44A mutant reduced CD82 endocytosis by ∼20% by quantifying the cells containing internalized CD82 or 50% in terms of the numbers of CD82 vesicles per cell (Fig. 2B), and both reductions were statistically significant (P<0.05). Despite the reductions, at least half of the internalized CD82 uses a dynamin-independent mechanism for endocytosis in PrEC-NH cells. To confirm that CD82 staining in the endocytosis assay represents only the internalized CD82, we analyzed the cell surface CD82 after the low-pH treatment in immunofluorescence and found that the acidic stripping indeed removed all of cell surface CD82 (Supplemental Fig. 2B). Thus, dynamin is not required for CD82 endocytosis.

Figure 2.

Dynamin is not essential for CD82 internalization. A) Du145-CD82, U937, PrEC-NH, and PC3-CD82 cells transiently transfected with either dynamin wild-type (WT) - or K44A mutant-GFP fusion were incubated with CD82 mAb M104 or TS82b for the 30-min endocytosis of CD82. Images of a Z-section were obtained by confocal microscopy. Scale bars = 10 μm. B) Quantitative analysis. Endocytoses were quantified as either percentage of dynamin/GFP-expressing cells that contained the internalized transferrin (Tf) or CD82 from total dynamin/GFP-expressing cells (left) or average numbers of Tf or CD82-positive vesicles per dynamin/GFP-expressing cell (right). In each experiment, ∼30–70 cells were quantitated from each treatment. Bars represent means ± se of endocytoses from 4 experiments. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.05.

Dynamin independence indicates that CD82 is internalized through neither CCVs nor caveolar vesicles. To substantiate this observation, we further assessed the requirement of the clathrin pathway in CD82 endocytosis. We found that K+ depletion, intracellular acidification, or an adaptor protein Eps15 mutant Eps15-DIII did not block CD82 endocytosis or alter the steady-state distribution of CD82 in Du145- or PC3-CD82 transfectant cells (Supplemental Fig. 3). The Eps15-DIII mutant plays a dominant-negative role to the endogenous Eps15 and specifically inhibits clathrin-dependent endocytosis (45). These results further support the conclusion that CCVs are not required for CD82 internalization.

ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6), a member of the ARF family GTPase, plays a key role in some clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytoses, such as internalization of the IL-2 receptor α subunit, MHC class I, and GPI-anchored protein CD59 (46, 47). Because CD82 undergoes CCV- and caveolae-independent endocytosis, we determined the role of ARF6 in CD82 internalization. The constitutively inactive form of ARF6 or ARF6 T27N did not markedly inhibit the internalization of CD82 in Du145-CD82 and PrEC-NH cells (Supplemental Fig. 4). As reported elsewhere (48), the internalization of MHC class I was markedly inhibited by ARF6 T27N (Supplemental Fig. 4). Hence, our study demonstrates that CD82 endocytosis is ARF6-independent.

Sterol lipid is important for CD82 internalization

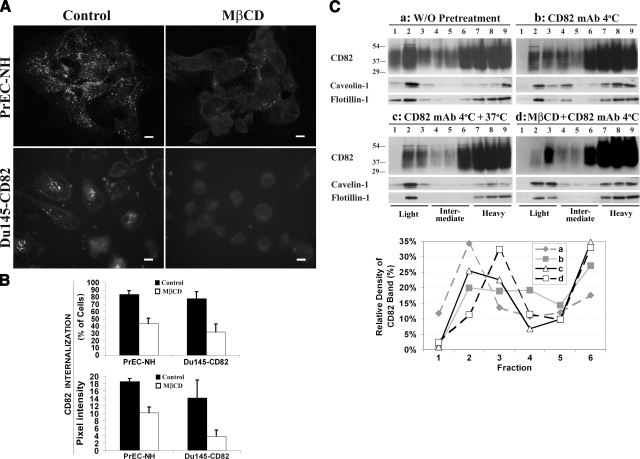

Lipid rafts are membrane microdomains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids. The components of lipid rafts, such as GM1 and GPI-anchored proteins, undergo dynamin-independent endocytosis (49). To determine whether lipid rafts regulate CD82 internalization, we assessed the impact of methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), which removes cholesterol, on CD82 endocytosis. Although MβCD treatment depleted most cholesterol from the cell surface (Supplemental Fig. 5A), it did not markedly remove CD82 from the plasma membrane (Supplemental Fig. 5B). However, the internalization of CD82 was substantially suppressed with MβCD treatment in both PrEC-NH and Du145-CD82 cells (Fig. 3A, B). The addition of cholesterol during MβCD treatment alleviates the endocytosis-inhibitory effect of MβCD (data not shown). Transferrin endocytosis, which depends on dynamin and clathrin, was not affected by MβCD (Supplemental Fig. 5C). In addition, we observed that the cholesterol-sequestrating reagent filipin inhibits CD82 internalization (data not shown).

Figure 3.

CD82 endocytosis is relatively cholesterol dependent. A) PrEC-NH cells were treated with 5 mM MβCD at 37°C for 60 min and then incubated with CD82 mAb at 4°C for 1 h, followed by PBS washes. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 or 60 min, followed by acidic washes and second Ab incubation. Images of Z-sections transverse cells were captured by confocal microscopy. Scale bars = 10 μm. B) Endocytoses were quantified with the percentage of cells containing internalized CD82 (top panel) and the fluorescent intensity of internalized CD82 per cell (bottom panel). Fifty cells were quantitated for each treatment in each experiment. Results represent means ± se of 3–4 experiments. *P < 0.01. C) Sucrose gradient experiment. Du145-CD82 cells grown on a 10-cm dish at confluent stage were treated at one of the following conditions: a) none; b) CD82 mAb TS82b (2 μg/ml) at 4°C for 1 h; c) CD82 mAb TS82b (2 μg/ml) at 4°C for 1 h and then 37°C for 30 min; or d0 MβCD (5 mM) at 37°C for 1 h and then CD82 mAb TS82b (2 μg/ml) at 4°C for 1 h. After pretreatment, cells were lysed and fractionated as described in Materials and Methods. Fractions were analyzed in Western blots using CD82 mAb TS82b, caveolin-1 pAb, or flotillin-1 mAb, respectively. The light to heavy fractions were designated as fractions 1–9. CD82 proteins in each fraction were quantified by measuring CD82 band density and are presented as the percentage of total band density of CD82 proteins in all light and intermediate fractions.

To confirm that CD82 is internalized through lipid rafts, we analyzed the distribution of CD82 in light membrane fractions obtained by discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation. As shown in Fig. 3C, a good portion of CD82 is present in buoyant or light fractions (fractions 1–3) and mainly in fraction 2, in untreated, adhered Du145-CD82 transfectant cells. Quantitative analysis of the CD82 band density and protein concentration in each fraction revealed the relative enrichment of CD82 in light fractions (Supplemental Fig. 6). On engaging with the CD82 mAb TS82b at 4°C, CD82 on the cell surface shifted from buoyant or light fractions to heavier fractions (Fig. 3C). For example, CD82 at fraction 1 shifted to fraction 2, and that at intermediate fraction 4 became relatively increased compared with that at light fractions 2 and 3. After being further incubated at 37°C for 30 min or after a 30-min endocytosis, CD82 at fraction 4, an intermediate fraction, was largely lost, presumably internalized. MβCD treatment disrupted the flotation of CD82 into buoyant and intermediate fractions or dragged CD82 from fraction 2 down to fraction 3, strongly suggesting that cholesterol is a component of CD82-containing buoyant and intermediate fractions. Notably, CD82 at fraction 4 was markedly diminished and probably shifted to heavy fractions on MβCD treatment, strongly suggesting that the internalized CD82 is MβCD-sensitive. For caveolin and flotillin, the markers of caveolae and lipid rafts, respectively, CD82 mAb treatment at 4°C shifted them mainly into fraction 4. As for CD82, both caveolin and flotillin at intermediate fraction 4 were almost completely diminished after the incubation was switched to 37°C, suggesting that they were also internalized. Finally, MβCD treatment shifted caveolin and flotillin to a heavier fraction, indicating that cholesterol was indeed present in buoyant fractions. This experiment was repeated several times, and the main observations, i.e., the heavy shift and the internalization of cholesterol-containing intermediate fractions, were reproducible. In some experiments in untreated Du145-CD82 cells, caveolin and flotillin-1 were detected in intermediate fractions besides light fractions and more CD82, caveolin, and flotillin-1 were found in fraction 1 than in fraction 2 (Fig. 5A).

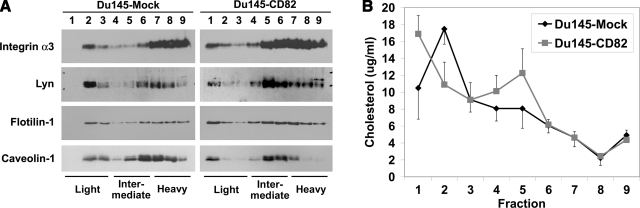

Figure 5.

CD82 reorganizes TEMs and lipid rafts in a cholesterol-related manner. A) Effect of CD82 expression on density distribution in sucrose gradient of integrin α3β1, Lyn, flotillin-1, and caveolin-1. Du145-Mock and -CD82 cells were lysed with 1% Lubrol WX and fractionated in the discontinuous sucrose gradients as described in Materials and Methods. The fractions were analyzed in a Western blot using integrin α3 pAb D23, Lyn pAb, flotillin-1 mAb, or caveolin-1 pAb, respectively. As labeled, fractions from light to heavy were designated 1–9, respectively. B) Effect of CD82 expression on membrane compartmentalization of cholesterol. Du145-Mock and -CD82 cells were lysed and fractionated as described above. Cholesterol in each fraction was quantified by using the Invitrogen Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit as described in Materials and Methods. Curves represent means ± se from four independent experiments.

We also found that approximately one-fourth of CD82 colocalized with GM1, a marker of lipid rafts, at either steady state or in a 30-min endocytosis period in Du145-CD82 cells (Supplemental Table 2). The colocalization of CD82 and GM1 remained essentially unchanged with CD82 mAb treatment. The colocalization of CD82 with caveolin was significantly less than that with GM1 at steady state and decreased further when the cells were treated with CD82 mAb (Supplemental Table 2).

CD82 endocytosis and dynamin-independent pinocytic pathways

Because the dynamin-independent endocytosis of CD82 resembles a recently identified pinocytic pathway that requires Cdc42 activity (50), we further characterized the role of Cdc42 in CD82 endocytosis. As shown in Fig. 4A, CD82 endocytosis was inhibited by Cdc42 N17, a dominant-negative mutant of Cdc42, to a statistically significant degree in PrEC-NH cells when the endocytosis was quantified as the number of vesicles containing the internalized CD82 per cell. The inhibition did not result from less binding of CD82 mAb to CD82 protein in the Cdc42 N17-expressing cells (data not shown). Under other conditions, CD82 endocytosis was not reduced or, even if it was reduced, the reduction not was statistically significant (Fig. 4A). Because earlier studies indicated that other Rho small GTPases such as Rac1 and RhoA are involved in various endocytic activities (51,52,53,54), we also analyzed their roles in CD82 endocytosis and found that neither a dominant-negative mutant of Rac1 nor one of RhoA could inhibit CD82 endocytosis (Fig. 4A). To determine whether CD82 is internalized through a fluid-phase endocytic mechanism, we analyzed the colocalization of CD82 and dextran, a marker for the fluid phase uptake, and found that one-third of internalized CD82 resided in the endocytic compartments positive in the internalized dextran (10 kDa) in Du145-CD82 cells (Fig. 4B), indicating that a small portion of CD82 is internalized through a fluid phase uptake pathway on CD82 expression. However, in PrEC-NH cells in which CD82 is constitutively expressed, almost no internalized CD82 was found in the same compartment with dextran (Fig. 4B). As expected, transferrin and dextran were not internalized into the same compartment in both cell lines (Fig. 4B). Because some CD82 and dextran were found in the same endocytic compartment in Du145-CD82 cells, we further analyzed the colocalization of CD82 with GPI-anchored proteins in this cell line. The internalized CD82 was hardly colocalized with intracellular GPI-anchored GFPs in Du145-CD82 cells (Supplemental Fig. 7), strongly suggesting that CD82 was not internalized into the GPI-anchored protein-enriched compartments (GEECs) (50). Thus, the dynamin-independent pinocytosis of CD82 appears not to fall into the same category as the dynamin-independent pinocytosis using GEECs as the early endocytic compartments.

Figure 4.

Roles of other dynamin-independent endocytic mechanisms in CD82 endocytosis and the cytoskeletal and signaling requirements of CD82 endocytosis. A) Du145-CD82 or PrEC-NH cells were transiently transfected with a Mieg3-GFP, Mieg3-GFP-Cdc42 N17, Mieg3-GFP-Rac1 N17, or Mieg3-GFP-RhoA N19 construct. At 36–48 h after transfection, the 1-h endocytosis of CD82 was analyzed with CD82 mAb TS82b as described above. Scale bars = 10 μm. Results of endocytoses were quantified by assessing the percentage of green cells containing internalized CD82 per total green cells. Approximately 30 cells were quantitated for each treatment in each experiment. Results represent means ± se of 4 experiments. ▪, PrEC-NH cells; □, Du145-CD82 cells. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.05. B) CD82 endocytosis was assayed at 37°C for 1 h and transferrin (Tf) endocytosis for 15 min. Alexa 488-conjugated dextran (10 kDa) was added to the cells at the final concentration (1 or 2 mg/ml) at the last 15 min during the 37°C incubation. Colocalization of the internalized CD82 or Tf with the internalized dextran was quantitated as the percentage of the dextran-colocalized CD82- or Tf-positive vesicles per total CD82- or Tf-positive vesicles, respectively. Approximately 40 cells were quantitated for each treatment in each experiment. Results represent means ± se of 4 experiments. Note that multiple cells were present as a clump in the PrEC-Tf/dextran image. C) Du145-CD82 or PrEC-NH cells were treated with DMSO or EIPA (20 μM) at 37°C for 1 h before CD82 endocytosis was assayed as described above. CD82 endocytoses were quantitated as percentage of cells containing CD82-positive intracellular vesicles from total cells. Histograms represent means ± se of CD82 endocytosis from 4 experiments. D) Top panel: Du145-CD82 or PrEC-NH cells were treated with DMSO, latrunculin A (1 μM), nocodazole (1 μM), LY294002 (25 μM), or wortmannin (100 nM) at 37°C for 1 h. CD82 endocytosis was assayed and quantified as described in C. Bottom panel: Images of CD82 endocytosis from the Du145-CD82 cells treated with DMSO or latrunculin A (1 μM) were obtained via fluorescent microscopy. For the distribution of cellular CD82, treated cells were stained with the second Ab after the primary Ab incubation. Scale bars = 10 μm (CD82); 20 μm (Tf).

Macropinocytosis is a dynamin- and clathrin-independent endocytic route for fluid uptake (22). Because the intracellular vesicles that CD82 is internalized into are sometimes exhibited as large vesicles, we assessed the role of macropinocytosis in CD82 endocytosis by using amiloride, a Na+/H+ channel blocker that specifically inhibits macropinocytosis. As shown in Fig. 4C, 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA), a potency-enhanced derivative of amiloride, did not alter CD82 endocytosis, indicating that macropinocytosis is not essential for CD82 endocytosis. An earlier study demonstrated that Rac GTPase activity is needed for macropinocytosis (55). The independence of Rac1 activity in CD82 endocytosis as described above (Fig. 4A) is also consistent with this conclusion.

Cytoskeletal and signaling requirements of CD82 endocytosis

To further characterize the endocytic mechanism of CD82, we assessed the role of the cytoskeleton in CD82 endocytosis. After pretreating Du145-CD82 and PrEC-NH cells with cytoskeleton-disruptive reagents, we performed a CD82 internalization assay to test whether the inhibitors had any effects on CD82 internalization. Nocodazole, a microtubule-dissociating compound, exerted no effect on the internalization of CD82 (Fig. 4D, top panel), whereas latrunculin A, an actin fiber-dissociating drug, drastically inhibited the internalization of >80% of surface CD82 in Du145-CD82 cells within a 60-min internalization timeframe (Fig. 4D). The pretreatment of cells with latrunculin had no effect on the binding of CD82 mAb to cell surface CD82 molecules (Fig. 4D, bottom panel), demonstrating that the inhibition of CD82 endocytosis was not a secondary effect. In addition, the latrunculin treatment appeared not to inhibit transferrin endocytosis in Du145 cells, in accordance with earlier observations (56, 57). Interestingly, latrunculin exerted no inhibitory effect on CD82 endocytosis in PrEC-NH cells (Fig. 4D, top panel), although the latrunculin treatment significantly altered the actin network and disrupted stress fibers in PrEC-NH cells (Supplemental Fig. 8). Notably, F-actin still formed patches at the cell periphery with latrunculin treatment. Because these patches could not be disrupted even when higher concentrations of latrunculin were used, the role of F-actin in CD82 endocytosis remains uncertain in PrEC-NH cells.

We also analyzed the impact of PI3K activity on CD82 endocytosis because PI3K is needed for the internalization of tetraspanin CD151. Du145-CD82 and PrEC-NH cells were treated with wortmannin or Ly294002, the inhibitors of PI3Ks, before CD82 internalization was measured. We found that neither wortmannin nor LY294002 inhibited the internalization of CD82 (Fig. 4D, top panel). Under the same condition, both PI3K inhibitors significantly inhibited the endocytosis of tetraspanin CD151 (data not shown). Thus, PI3K is not required for CD82 endocytosis.

CD82 reorganizes TEMs and lipid rafts to form CD82-containing TEMs

Because CD82 undergoes cholesterol-dependent endocytosis and can be found in lipid rafts (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 2), we investigated whether CD82 brings its associated TEMs to lipid rafts. First, we analyzed the effect of CD82 on the membrane distributions of integrin α3β1, a major constituent of TEMs (4, 5), and Lyn, a lipid raft resident and the only Src family kinase expressed in Du145 cells (10), using sucrose density gradient flotation experiments. As shown in Fig. 5A, integrin α3β1 and Lyn proteins were detected in light fractions 2 and 3 in Du145 cells in which no CD82 is expressed (10). When CD82 is expressed, the integrin α3β1 and Lyn proteins in lipid rafts were shifted to the lighter fractions, i.e., fractions 1 and 2 (Fig. 5A). In addition, more integrin α3β1 and Lyn were found in intermediate fractions, i.e., fractions 4, 5, and 6, on CD82 expression (Fig. 5A). Similar to the shift in the light fractions, more integrin α3β1 and Lyn of the intermediate fractions in Du145-CD82 cells were present in fractions 5 and 4, which might be internalized, as shown in Fig. 3C. Likewise, we found that CD82 expression also resulted in shifts of flotillin-1 and caveolin in the light and intermediate fractions (Fig. 5A). In some experiments, we observed the shifts of flotillin-1 and caveolin toward intermediate fractions from both light and heavy fractions (data not shown). Thus, these results suggest that the cholesterol-dependent coalescence of CD82 with lipid rafts alters the composition, reflected by the density, of both TEMs and lipid rafts.

Because of the shifts of TEMs and lipid raft components to the lighter-density fractions, we analyzed the effect of CD82 on the membrane cholesterol distribution. In Du145-Mock cells, cholesterol is enriched in the light membrane fractions or lipid rafts (Fig. 5B), as expected. In CD82-expressing Du145 cells, the peak of cholesterol is shifted from fraction 2 to 1. Surprisingly, a second but minor peak was found in fraction 5, an intermediate fraction (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that CD82 redistributes the membrane cholesterol to form two membrane microdomains that are enriched in cholesterol but distinct in density and composition. The results from Fig. 5 suggest that TEMs and lipid rafts constitute these cholesterol-enriched or -containing microdomains in a CD82-dependent manner.

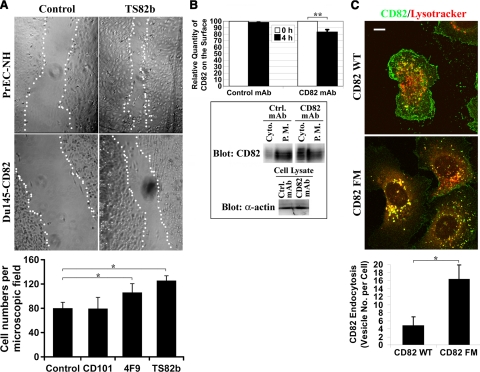

CD82 endocytosis may regulate cell migration

It is well established that CD82 inhibits cell migration (15). To determine whether CD82 endocytosis regulates its motility-inhibitory function, we investigated the effect of CD82 antibodies on cell migration. In wound-healing experiments, CD82 mAb TS82b enhanced the wound-healing abilities of both Du145-CD82 and PrEC cells (Fig. 6A, top panel). Similar effects were observed with another CD82 mAb, M104 (data not shown). To confirm this observation, we analyzed the chemohaptotactic cell migration in the presence of various mAbs in transwell migration assays. In accordance with the results of the wound-healing assay, we found that CD82 mAbs, TS82b and 4F9, significantly increased the cell migration on laminin 1 of Du145-CD82 cells in the transwell migration assay, whereas the control mAbs had no significant effect on cell migration (Fig. 6A, bottom panel). These results indicate that CD82 mAbs up-regulate cell movement and alleviate the motility-inhibitory activity of CD82.

Figure 6.

CD82 endocytosis may regulate cell migration. A) CD82 Abs promote cell migration. Top panel: wound-healing assay. Wounded Du145-CD82 or PrEC-NH cell monolayers were cultured overnight for healing in the presence of CD82 mAb TS82b (5 μg/ml) or mouse IgG (5 μg/ml) as the control mAb and then photographed under a light microscope. Scale bar = 100 mm. Bottom panel: transwell chemohaptotactic cell migration. Underside of inserts was coated with laminin 1 (20 μg/ml). Cells were allowed to migrate at 37°C for 12 h in the medium containing the indicated mAbs (5 μg/ml). Transmigrated cells were quantitated. Bars represent average ± sd numbers of transmigrated cells from 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.01. B) CD82 Ab treatment down-regulates the cell surface level of CD82. Top panel: Du145-CD82 cells were incubated with CD82 mAb TS82b or control mouse IgG at 4°C for 1 h, followed by washes with PBS to remove unbound CD82 mAb. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 4 h for internalization, followed by acidic washes on ice to remove noninternalized mAbs. Cells were then incubated with Alexa 594-conjugated CD82 mAb TS82b at 4°C for 1 h and analyzed by flow cytometry for the cell surface CD82 levels. **P = 0.025. Bottom panel: plasma membrane (P.M.) and cytoplasmic (Cyto.) fractions from the Du145-CD82 cells treated with either control or CD82 mAb for 1 h were prepared by Percoll gradient fractionation as described in Materials and Methods. Equal amounts of proteins from the plasma membrane and cytoplasmic fractions were analyzed with CD82 mAb in a Western blot. Levels of actin in total cell lysates were used as protein loading control. C) Top panel: CD82 palmitoylation-deficient mutant contains more internalized CD82. PC3-CD82 wild-type and -FM mutant transfectant cells were incubated with LysoTracker Red DND-99 at 37°C for 10 min, followed by fixation and permeabilization. Cells were then incubated sequentially with CD82 mAb TS82b and Alexa488-conjugated second Ab. Fluorescent images of the X-Y transverse sections above the basal cell surface were captured by confocal microscopy. Scale bar = 10 μm. Bottom panel: CD82 endocytosis was performed as described above at 37°C for 3 h in the PC3-CD82 wild-type and -FM mutant transfectant cells that contain the equivalent levels of surface CD82. CD82 endocytoses were quantitated as average numbers of CD82-positive intracellular vesicles per cell. Histogram represents means ± se of 3 experiments. *P < 0.01.

Based on the fact that CD82 mAb promotes cell migration, we predicted that CD82 mAb treatment triggers the enhanced internalization of the cell surface CD82 and subsequently reduces the level of cell surface CD82. To determine whether the motility-promoting effect of CD82 mAbs results from the endocytosis of CD82, we analyzed the changes of the cell surface CD82 levels after CD82 mAb treatment and endocytosis. As shown in Fig. 6B (top panel), the amount of cell surface CD82 proteins, determined by flow cytometry, was significantly diminished after CD82 mAb treatment for 4 h. After separating the plasma membrane and cytoplasm, we found by Western blot that markedly more CD82 proteins were detected in the cytoplasmic fraction on CD82 mAb treatment than in the control group (Fig. 6B, bottom panel), supporting the fact that CD82 mAb treatment facilitates CD82 endocytosis.

Our earlier study demonstrated that CD82 palmitoylation is needed for the motility-inhibitory activity of CD82 (58). The CD82 palmitoylation-deficient mutant, FM mutant, is no longer able to inhibit (or at least inhibit much less efficiently than the wild type) cell migration and invasion (58). We compared the subcellular distributions of CD82 in PC3-CD82 wild-type and FM transfectants. As shown in Fig. 6C, a substantial amount of CD82 was distributed at the cell periphery as well as in intracellular vesicles in the wild-type transfectant cells, and some of the vesicles were probably lysosomes because of positive staining of LysoTracker. In contrast, in the FM transfectant cells, the distribution of CD82 was significantly reduced at the cell periphery but was markedly increased in intracellular vesicles, a majority of which are LysoTracker-positive, low-pH compartments (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that, compared with the wild type, more CD82 FM mutant proteins underwent endocytosis and were accumulated in endocytic compartments after internalization. After collecting the PC3-CD82 wild-type transfectant cells expressing the same level of surface CD82 as PC3-CD82 FM mutant cells by flow cytometry, we compared CD82 endocytosis between CD82 wild-type and FM transfectants. As shown in Fig. 6C (bottom panel), the CD82 FM mutant proteins exhibited markedly higher endocytosis than the wild type, supporting the correlation between more internalized CD82 and less migratory inhibition.

DISCUSSION

Dynamin- and clathrin-independent endocytosis of CD82

The observation that CD82 undergoes endocytosis drove us to identify the endocytic mechanism of this tetraspanin. Many tetraspanins, including CD82, contain a YXXø internalization or sorting motif in their C-terminal cytoplasmic tails (31, 32). The interaction of the YXXø motif with the μ2 chain of the AP2 complex initiates the internalization of transmembrane proteins into CCVs (59,60,61). For example, this motif in tetraspanin CD63 directs CD63 endocytosis through CCVs (62, 63). However, the YXXø motif does not always determine the internalization (64). In fact, perturbation of this motif in CD82 exerts no significant effect on CD82 endocytosis (unpublished results). We demonstrated in this study that dynamin is not required for CD82 endocytosis, which therefore precludes the requirement of clathrin for CD82 endocytosis. The independence of CD82 endocytosis from the clathrin pathway is also supported by the lack of biochemical interaction between the CD82 YXXø motif and the μ2 chain of the AP2 complex (Supplemental Table 1), no effects of the Eps15 DIII Δ2 mutant, potassium depletion or acidification on CD82 internalization (Supplemental Fig. 3), and rather slow endocytosis kinetics of CD82 (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Clathrin-independent endocytosis includes caveolae-dependent pinocytosis, caveolae-independent pinocytosis, macropinocytosis, and phagocytosis (21, 65). Dynamin is required for caveolae-mediated endocytosis because the activity of dynamin II is needed for the formation of caveolar vesicles (21, 66). For clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytosis, dynamin is required in some cases such as the IL-2 receptor (67) but not in other cases such as simian virus 40 (SV40) (68). Recent studies have indicated that ARF6 is required for some of the dynamin-, clathrin-, and caveolae-independent endocytosis (46, 69). Cholera toxin-binding subunit (CTxB) or GM1 ganglioside, however, can be internalized in a dynamin-, clathrin-, caveolae-, and ARF6-independent manner (70). Although CD82 endocytosis is not fully independent of dynamin in some cells, dynamin activity is not essential for CD82 endocytosis in all cell lines analyzed. Hence, similar to CTxB, CD82 endocytosis falls into the category of being a dynamin-, clathrin-, caveolae-, and ARF6-independent pathway. Because CD82 endocytosis was partially inhibited by the dynamin K44A mutant in PrEC-NH cells and probably also in Du145-CD82 cells, dynamin probably plays a partial role in CD82 endocytosis or CD82 can be internalized through both dynamin-/clathrin-independent and dynamin-dependent/clathrin-independent pathways under certain cellular environments.

Intermediate and destination vesicular compartments of CD82 endocytosis

Herein we have demonstrated that the internalized CD82 is targeted to endosomal and lysosomal compartments. Destined to recycling, degradation, transcytosis, or possibly exocytosis, the internalized proteins are sorted to the target organelles by the activated ARF and Rab small GTPases and membrane lipids that are specifically displayed on organelles (71, 72). It is generally accepted that early endosomes represent both the point of convergence for internalized molecules and the first sorting station in the endocytic pathway (38). Some internalized CD82 proteins were targeted to Rab5-positive early endosomes. Rab5-positive early endosomes are endocytic intermediates for CCVs and possibly for caveolar vesicles (38, 73, 74). The presence of internalized CD82 in Rab5-positive early endosomes suggests the possible convergence of CD82 endocytic vesicles with the endocytic intermediates of classic endocytic pathways and/or the partial internalization of CD82 through classic endocytosis pathways, although the pathways are not essential for CD82 internalization.

For dynamin-independent but cholesterol-dependent endocytosis, a recent study showed that flotillin-positive vesicles might function as the endocytic intermediate compartments (41). No colocalization of CD82 with flotillin either on the plasma membrane or in intracellular vesicles indicates that CD82-containing TEMs and flotillin-containing lipid rafts are discrete microdomains in the plasma membrane and that flotillin-positive vesicles are not the intermediate compartments for the internalized CD82. The structure of clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic vesicles emerged from recent studies on SV40- and CTxB-mediated GM1 endocytoses and displayed heterogeneous morphology ranging from small, tight-fitting vesicles to tubular or ring-shaped structures (68, 70). Although the ultrastructure of CD82 endocytic pits and vesicles remains to be analyzed, we predict that the CD82 endocytic vesicles immediately after internalization would be similar to these newly discovered endocytic compartments based on the colocalization between GM1 and ∼20% of freshly internalized CD82 (Supplemental Table 2).

After early endosomes, a large portion of internalized CD82 is not committed to recycling, if the endocytic rate is equivalent to the recycling rate. However, the recycling of a small portion of internalized CD82 could be functionally important. If the recycling rate was high, a few recycling endosomes could recycle substantial amounts of internalized CD82. Late endosomes and lysosomes are likely to be the destination for most internalized CD82 because CD82 is gradually accumulated in CD63-positive compartments after endocytosis. Distinct from CD82, dynamin-independent endocytosis drives CTxB and GPI-anchored proteins to the Golgi complex (70, 75), GPI-anchored proteins to recycling endosomes (50), or SV40 to endoplasmic reticulum (68, 74).

Cholesterol-enriched microdomains and lipid-dependent endocytosis of CD82

Lipid composition and lipid-protein interactions in plasma membranes play essential roles in the compartmentalization of plasma membranes into functionally discrete microdomains such as lipid rafts. Notably, lipid rafts are not stationary structures in plasma membrane and can be internalized (76). The lipid raft endocytic pathway may constitute a specialized, high-capacity internalization route for the endocytosis of some molecules (22). However, this pathway may not be homogeneous and possibly covers a range of endocytic events (22). In this study, perturbation of lipid rafts using cholesterol sequestration or a depletion reagent markedly inhibited CD82 endocytosis. We also found that CD82 partially colocalizes and cotraffics with GM1. In addition, CD82 constitutively coalesces with lipid rafts in T cells (17). Our study also consistently indicated that CD82 is present in MβCD-sensitive buoyant fractions of sucrose gradient. Furthermore, tetraspanins CD9, CD81, and CD82 bind to cholesterol (76). Moreover, CD82 was recently found to interact with GM2 ganglioside (19). Finally, CD82 expression enhances the levels of lipid raft components GD1a and GM1 gangliosides in the plasma membrane and shifts EGFR to a buoyant fraction (13). These observations underline a coherent relationship between lipid rafts and the cell surface CD82. Thus, it is not surprising that lipid rafts play a key role in CD82 endocytosis. Coincidently, GM1 is the cellular binding subunit of CTxB, which exhibits an endocytic mechanism similar to that of CD82. For example, the dynamin-independent internalization of CTxB can also be abolished by cholesterol sequestration or removal (70). The partial colocalization of CD82 with GM1 in endocytosis further underscores the possibility that CD82 and CTxB share overlapping steps in their endocytic routes. Thus, a direct consequence for the coalescence of CD82 with lipid rafts is likely to be the commitment of CD82 to endocytosis.

Both lipid raft- and caveolae-mediated endocytoses are cholesterol dependent. Because of the dynamin independence in CD82 internalization, we conclude that caveolae are not essential to CD82 endocytosis. The limited colocalization between CD82 and caveolin supports this conclusion. However, CD82 internalization may occur physiologically through both lipid raft and caveolae pathways but shifts to the lipid raft pathway when the caveolae pathway is blocked by dynamin K44A mutant. Hence, it remains to be determined whether the caveolae pathway constitutes a part of the CD82 endocytic mechanism, especially in the cells such as PrEC-NH in which dynamin plays a partial role in CD82 endocytosis. In addition, although cholesterol sequestration largely blocked CD82 endocytosis, it did not completely abolish it, implying that a small portion of CD82 may undergo cholesterol-independent endocytosis. Together, CD82 is internalized mainly via a lipid raft-dependent mechanism. Other pathways for CD82 endocytosis may also exist but are not essential.

Similarly to our observations, actin polymerization was not required for the dynamin-independent but cholesterol-dependent endocytosis or infectivity of SV40 in one cell line but was partially required in another cell line (68). These results suggest the involvement of different cholesterol-dependent endocytic mechanisms in CD82 or SV40 endocytosis in different cells. It is also possible that the latrunculin A treatment may not always result in a complete disruption of actin polymerization in every cell line. For example, the cell peripheral actin patches still existed in PrEC-NH cells after the latrunculin A treatment (Supplemental Fig. 8) and may facilitate the endocytosis of CD82 at the plasma membrane overlaying the patches. Notably, the coalescence of CD82 with lipid rafts in T cells was enhanced by latrunculin A but diminished by the F-actin-stabilizing agent phalloidin (17). Hence the surface CD82 can be classified into two pools: lipid raft-associated and actin fiber-linked CD82. On the engagement of CD82 on T cells with immobilized CD82 mAbs, CD82 increasingly partitioned into heavy fractions away from light and intermediate fractions (17). Actin depolymerization blocked this immobilized CD82 Ab-induced translocation of CD82 (17). These observations suggest that actin fiber-linked CD82 is present on the cell surface because the immobilized CD82 Ab-engaged CD82 is unlikely to be internalized. Once dissociated from actin cytoskeleton, CD82 is probably translocated into lipid rafts, possibly by dragging TEMs. In lipid rafts, CD82 could commit to the endocytosis in which the actin cytoskeleton is subsequently involved.

CD82 reorganizes TEMs and lipid rafts through redistributing cholesterol

Tetraspanins interact with each other and with their associated transmembrane and intracellular molecules to form large transmembrane signaling complexes called tetraspanin webs or TEMs (4, 5). From endocytosis studies on CD82, CD63, and CD151, we conclude that tetraspanin webs are dynamic structures trafficking between the plasma membrane and endosome/lysosome. Analysis of CD82-reorganized TEMs reveals another aspect of the dynamic nature of TEMs, i.e., the regulated and cholesterol-mediated lateral interaction with lipid rafts in membrane. Although it remains unknown whether the reorganized TEMs and lipid rafts are exclusively localized in the plasma membrane, CD82 trafficking implies that these reorganized cholesterol-enriched microdomains are probably also present in endosomes and lysosomes.

CD82 expression results in the accumulation of cholesterol in intermediate fractions and changes in the density of TEMs and lipid rafts, reflecting the changes in composition. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the double peaks of cholesterol in the membrane-density fractions. Notably, CD82 reorganizes the preexisting coalescence between TEMs and lipid rafts. The simultaneous shift in density of lipid rafts and TEMs from fraction 2 to 1 indicates the formation of more tightly packed, ordered, and cholesterol- and saturated lipid-enriched lipid rafts and TEMs in CD82-expressing cells. Based on the earlier observations that CD82 up-regulates cellular glycosphingolipids (13), we predict that the net increase of cholesterol and/or other saturated lipids in membrane drives the light shift of both lipid rafts and lipid raft-associated TEMs. Also, because CD82 physically interacts with cholesterol (76), the CD82-bound cholesterol could play a direct role in the light shift of both TEMs and lipid rafts that are associated with each other. The appearance of cholesterol-enriched intermediate fractions suggests that the CD82-dependent coalescence of TEMs with lipid rafts transforms the classic lipid rafts into a cholesterol-containing microdomain that comprises CD82 and the components from lipid rafts and TEMs. Besides cholesterol, CD82 also binds to GM2 (19). CD82 probably clusters saturated lipids into TEMs and leads to the light shift of some TEMs from heavy to intermediate fractions. Hence, the cholesterol-containing microdomain with intermediate density possibly results from the shifts of both lipid rafts from light fractions and TEMs from heavy fractions. It appears that this cholesterol-containing microdomain with intermediate density is the characteristic of CD82-containing TEMs.

The binding and/or cross-linking of the cell surface CD82 and/or CD82-containing TEMs by CD82 Abs may alter the lateral interaction of CD82 with lipid rafts. The CD82 Ab treatment shifted not only CD82 itself but also the markers of lipid rafts and caveolae from light to intermediate and possibly heavy fractions. These light and intermediate fractions are also sensitive to cholesterol removal. Interestingly, CD82 and those markers in an intermediate fraction appear to undergo endocytosis together because they both disappeared after 37°C incubation. If so, the cholesterol-containing microdomain in intermediate fractions may function as the endocytic platform for CD82. Although flotillin and caveolin were found in this fraction, we predict that they are not parts of the CD82 endocytic platform because caveolin is not essential for CD82 endocytosis, and we observed no colocalization of flotillin with CD82.

Functional significance of CD82 endocytosis

Interestingly, opposite to the cellular expression of CD82, the engagement of CD82 at the cell surface with its specific Abs promotes cell migration. The effect of CD82 Abs could result from the blockade of the signaling elicited by the cell surface CD82 and/or the accelerated endocytosis and subsequent turnover of the cell surface CD82. These two possibilities are not necessarily mutually exclusive because the accelerated internalization and degradation of CD82 could lead to the attenuated CD82 signaling. At least, the effect of CD82 Abs underscores the notion that CD82 has to be present at the cell surface to inhibit cell motility no matter which of these two possibilities is true. However, because the whole IgG molecule and Fab fragment of CD82 Ab exhibit similar endocytic kinetics, CD82 Ab would not markedly and rapidly accelerate the endocytosis of CD82. Indeed, CD82 mAb treatment did not drastically alter the cell surface level of CD82, at least in Du145-CD82 cells, but the down-regulation of CD82 at the cell surface became significant after the 4-h Ab treatment and would be even greater in the 12-h cell migration. In particular, when compared with the intracellular pool of CD82, the internalized CD82 was markedly increased even after the 1-h Ab treatment. Hence, CD82 Abs apparently induce CD82 endocytosis.

Moreover, correlating well with our earlier observation that the palmitoylation of CD82 is needed for the movement-inhibitory activity of CD82 (58), the palmitoylation-deficient CD82 proteins are largely localized in the intracellular acidic vesicular compartment or lysosomes and become markedly less prevalent at the cell surface compared with the wild type. Apparently, the intracellular accumulation results from, at least in a part, more endocytosis of palmitoylation-deficient CD82, supporting the notion that more CD82 endocytosis correlates with less migratory inhibition of CD82. Even if CD82 Abs attenuated signaling and such signaling attenuation played a major role in the migration-promoting effect of CD82 Abs, the Ab-induced CD82 endocytosis and subsequent trafficking of CD82 to lysosomes probably contributes to such signaling attenuation.

Although in this study we have elucidated the mechanism of CD82 endocytosis and described the CD82-induced reorganization of membrane microdomains, many new questions arise. For example, does CD82 alter the endocytosis of lipid rafts and/or caveolae or vice versa? Does CD82 expression alter the endocytosis of TEM components such as integrins in a cholesterol-dependent manner? How do CD82 and its Ab change the composition of lipid rafts and caveolae? Why does more CD82 float up to light fractions when the cells are lysed with the detergent Lubrol than with other detergents (17, 77,78,79)? The answers to these questions probably hold the key to understanding the biochemical function of CD82 as well as that of other tetraspanins and will also provide insight into the molecular mechanism by which CD82 suppresses cell movement and cancer metastasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Lisa Jennings and David Armbruster for constructive suggestions and critical review of the manuscript. We especially thank all the colleagues who provided the antibodies and constructs used in this study. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health research grant CA-96991 and Department of Defense research grant W81XWH-04-1-0156 (to X.A.Z.).

References

- Martin F, Roth D M, Jans D A, Pouton C W, Partridge L J, Monk P N, Moseley G W. Tetraspanins in viral infections: a fundamental role in viral biology? J Virol. 2005;79:10839–10851. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.10839-10851.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitadokoro K. CD81 extracellular domain 3D structure: insight into the tetraspanin superfamily structural motifs. EMBO J. 2001;20:12–18. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneuret M, Delaguillaumie A, Lagaudriere-Gesbert C, Conjeaud H. Structure of the tetraspanin main extracellular domain: A partially conserved fold with a structurally variable domain insertion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40055–40064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler M E. Tetraspanin proteins mediate cellular penetration, invasion and fusion events, and define a novel type of membrane microdomain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.153609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Tetraspanins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1189–1205. doi: 10.1007/PL00000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrant JM, Robb L, van Spriel AB, Wright M D. Tetraspanins: molecular organisers of the leukocyte surface. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maecker H T, Todd S C, Levy S. The tetraspanin superfamily: molecular facilitators. FASEB J. 1997;11:428–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Shoham T. The tetraspanin web modulates immune-signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:136–148. doi: 10.1038/nri1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J T. KAI 1, a metastasis suppressor gene for prostate cancer on human chromosome 11p11.2. Science. 1995;268:884–886. doi: 10.1126/science.7754374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X A, He B, Zhou B, Liu L. Requirement of the p130CAS-Crk coupling for metastasis suppressor KAI1/CD82-mediated inhibition of cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27319–27328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X A, Lane W S, Charrin S, Rubinstein E, Liu L. EWI2/PGRL associates with the metastasis suppressor KAI1/CD82 and inhibits the migration of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2665–2674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odintsova E, Sugiura T, Berditchevski F. Attenuation of EGF receptor signaling by a metastasis suppressor, the tetraspanin CD82/KAI-1. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1009–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odintsova E, Voortman J, Gilbert E, Berditchevski F. Tetraspanin CD82 regulates compartmentalisation and ligand-induced dimerization of EGFR. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4557–4566. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonoli H, Barrett J C. CD82 metastasis suppressor gene: a potential target for new therapeutics? Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W M, Zhang X A. KAI1/CD82, a tumor metastasis suppressor. Cancer Lett. 2006;240:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P, Marreiros A, Russell P J. KAI1 tetraspanin and metastasis suppressor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:530–534. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaguillaumie A. Tetraspanin CD82 controls the association of cholesterol-dependent microdomains with the actin cytoskeleton in T lymphocytes: relevance to co-stimulation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5269–5282. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odintsova E, Butters T, Monti E, Sprong H, van Meer G, Berditchevski F. Gangliosides play an important role in the organization of CD82-enriched microdomains. Biochem J. 2006;400:315–325. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todeschini A R, Dos Santos J N, Handa K, Hakomori S-I. Ganglioside GM2-tetraspanin CD82 complex inhibits Met activation, and its cross-talk with integrins: basis for control of cell motility through glycosynapse. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8123–8133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611407200. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Ghosh R N, Maxfield F R. Endocytosis. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:759–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner S D, Schmid S L. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham M, Parton R G. Clathrin-independent endocytosis: new insights into caveolae and non-caveolar lipid raft carriers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:350–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans L. Secrets of caveolae- and lipid raft-mediated endocytosis revealed by mammalian viruses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M S, Watts C, Zerial M. Membrane dynamics in endocytosis. Cell. 1996;84:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80988-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh M, Helenius A. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell. 2006;124:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Guglielmo G M, Le Roy C, Goodfellow A F, Wrana J L. Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-β receptor signalling and turnover. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:410–421. doi: 10.1038/ncb975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escola J M. Selective enrichment of tetraspan proteins on the internal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes and on exosomes secreted by human B-lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20121–20127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond C, Denzin L K, Pan M, Griffith J M, Geuze H J, Cresswell P. The tetraspan protein CD82 is a resident of MHC class II compartments where it associates with HLA-DR, -DM, and -DO molecules. J Immunol. 1998;161:3282–3291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nydegger S, Khurana S, Krementsov D N, Foti M, Thali M. Mapping of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains that can function as gateways for HIV-1. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:795–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J S, Dell'Angelica E C. Molecular bases for the recognition of tyrosine-based sorting signals. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:923–926. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipp C S, Kolesnikova T V, Hemler M E. Functional domains in tetraspanin proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:106–112. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berditchevski F. Complexes of tetraspanins with integrins: more than meets the eye. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4143–4151. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.23.4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion B A, Berditchevski F, Kraeft S K, Chen L B, Hemler M E. TM4SF proteins CD81 (TAPA-1), CD82, CD63 and CD53 specifically associate with α4β1 integrin. J Immunol. 1996;157:2039–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Liu L, Cook G A, Grgurevich S, Jennings L K, Zhang X A. Tetraspanin CD82 attenuates cellular morphogenesis through down-regulating integrin α6-mediated cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3346–3354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Xia B, Moshiach S, Xu C, Jiang Y, Chen Y, Sun Y, Lahti J M, Zhang X A. The microenvironmental determinants for kidney epithelial cyst morphogenesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slimane T A, Trugnan G, van Ijzendoorn S C D, Hoekstra D. Raft-mediated trafficking of apical resident proteins occurs in both direct and transcytotic pathways in polarized hepatic cells: role of distinct lipid microdomains. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:611–624. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R, Febbo P G, Majumder P K, Zhao J J, Mukherjee S, Signoretti S, Campbell K T, Sellers W R, Roberts T M, Loda M, Golub T R, Hahn W C. Androgen-induced differentiation and tumorigenicity of human prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8867–8875. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J. The endocytic pathway: a mosaic of domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:721–730. doi: 10.1038/35096054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield F R, McGraw T E. Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrmann K, van der Sluijs P. Regulation of membrane transport through the endocytic pathway by rabGTPase. Mol Membr Biol. 1999;16:81–87. doi: 10.1080/096876899294797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glebov O O, Bright N A, Nichols B J. Flotillin-1 defines a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:46–54. doi: 10.1038/ncb1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh P, McIntosh D P, Schnitzer J E. Dynamin at the neck of caveolae mediates their budding to form transport vesicles by GTP-driven fission from the plasma membrane of endothelium. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:101–114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid S L, McNiven M A, De Camilli P. Dynamin and its partners: a progress report. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:504–512. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sever S, Schmid S L. Impairment of dynamin’s GAP domain stimulates receptor-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 1999;398:481–486. doi: 10.1038/19024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmerah A, Poupon V, Cerf-Bensussan N, Dauty-Versat A. Mapping of Eps15 domains involved in its targeting to clathrin-coated pits. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3288–3295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky N, Weigert R, Donaldson J G. Convergence of non-clathrin- and clathrin-derived endosomes involves Arf6 inactivation and changes in phosphoinositides. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:417–431. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-04-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky N, Weigert R, Donaldson J G. Characterization of a nonclathrin endocytic pathway: membrane cargo and lipid requirements. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3542–3552. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg K, Rossman K L, Der C J. The Ras superfamily at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:843–846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols B. Caveosomes and endocytosis of lipid rafts. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4707–4714. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabharanjak S, Sharma P, Parton R G, Mayor S. GPI-anchored proteins are delivered to recycling endosomes via a distinct cdc42-regulated, clathrin-independent pinocytic pathway. Dev Cell. 2002;2:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaze C, Dujeancourt A, Baba T, Lo C G, Benmerah A, Dautry-Varsat A. Interleukin 2 receptors and detergent-resistant membrane domains define a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro S, Wiewrodt R, Thomas A, Koniaris L, Albelda S M, Muzykantov V R, Koval M. A novel endocytic pathway induced by clustering endothelial ICAM-1 or PECAM-1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1599–1609. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko E, Lutgens E, Stan R-V, Simons M. Fibroblast growth factor 2 endocytosis in endothelial cells proceed via syndecan-4-dependent activation of Rac1 and a Cdc42-dependent macropinocytic pathway. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3189–3199. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassart A, Dujeancourt A, Lazarow P B, Dautry-Varsat A, Sauvonnet N. Clathrin-independent endocytosis used by the IL-2 receptor is regulated by Rac1, Pak1, and. Pak2. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:356–362. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]