Abstract

In gram-positive bacteria, CodY is an important regulator of genes whose expression changes upon nutrient limitation and acts as a repressor of virulence gene expression in some pathogenic species. Here, we report the role of CodY in Bacillus anthracis, the etiologic agent of anthrax. Disruption of codY completely abolished virulence in a toxinogenic, noncapsulated strain, indicating that the activity of CodY is required for full virulence of B. anthracis. Global transcriptome analysis of a codY mutant and the parental strain revealed extensive differences. These differences could reflect direct control for some genes, as suggested by the presence of CodY binding sequences in their promoter regions, or indirect effects via the CodY-dependent control of other regulatory proteins or metabolic rearrangements in the codY mutant strain. The differences included reduced expression of the anthrax toxin genes in the mutant strain, which was confirmed by lacZ reporter fusions and immunoblotting. The accumulation of the global virulence regulator AtxA protein was strongly reduced in the mutant strain. However, in agreement with the microarray data, expression of atxA, as measured using an atxA-lacZ transcriptional fusion and by assaying atxA mRNA, was not significantly affected in the codY mutant. An atxA-lacZ translational fusion was also unaffected. Overexpression of atxA restored toxin component synthesis in the codY mutant strain. These results suggest that CodY controls toxin gene expression by regulating AtxA accumulation posttranslationally.

The gram-positive spore-forming pathogen Bacillus anthracis is the causative agent of anthrax, a disease of mammals (26, 38). B. anthracis spores initiate infection; once inside the host, the spores germinate, generating vegetative cells that multiply in host tissues. It is during this proliferative stage that B. anthracis produces its key virulence factors, namely a tripartite toxin and a poly-γ-d-glutamate capsule. The toxin is a combination of protective antigen (PA; encoded by pagA), lethal factor (LF; encoded by lef), and edema factor (EF; encoded by cya). The toxin component genes are located on pXO1, a 182-kb plasmid (40). Anthrax toxin causes the destruction of host organs and aids in the suppression of the immune system during infection (1, 38). The biosynthetic enzymes for capsule production are encoded by the capBCADE operon on the plasmid pXO2 (9). The capsule of B. anthracis contributes to pathogenicity by enabling the bacteria to evade host immune defenses and provoke septicemia (38).

The regulation of the genes encoding the anthrax toxin components and the capsule biosynthetic machinery has been studied in considerable detail (reviewed in references 17 and 41). The production of toxin and capsule responds to environmental cues, such as the presence of CO2/bicarbonate and a temperature of 37°C (17, 53). The production of toxin components is low during exponential growth and reaches its highest level during entry into stationary phase (27, 53). AtxA, a protein encoded by pXO1, is essential for expression of toxin components and has an important role in capsule operon expression (7, 16, 20, 27, 64). It also controls expression of more than 100 genes, including pXO1, pXO2, and chromosomally encoded genes (7, 37). AtxA activity was found to be dependent on its phosphorylation state, but no DNA-binding activity has so far been described, leaving open the possibility that AtxA may not act as a canonical repressor or activator of transcription (63). Other gene products are thought to modulate virulence gene expression. AbrB (43) represses atxA expression (49, 59). The role of σH is less clear, with conflicting reports on the requirement of this alternative RNA polymerase sigma factor for the transcription of atxA (6, 22).

The induction of virulence gene expression in B. anthracis during entry into the stationary phase suggests that nutrient limitation may be important for optimal toxin and capsule production. Similar phenomena of stationary-phase-associated gene regulation are mediated by the CodY protein in several species of low-G+C gram-positive bacteria (58). In Bacillus subtilis, the bacterium in which CodY was first described (54), CodY acts during the rapid exponential growth phase as a repressor of many stationary-phase and sporulation genes and as a positive regulator of other genes, including some involved in carbon overflow metabolism (39, 46, 50). Binding of B. subtilis CodY to DNA is stimulated by the presence of both GTP and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), which act additively (23, 46, 51). As a result of the decrease in the intracellular pools of GTP and BCAAs when cells enter the stationary phase (56), CodY becomes less active, leading to the induction of genes that are targets of CodY repression.

Several groups have assessed the potential involvement of CodY in regulation of virulence factor gene expression in gram-positive bacteria. These studies revealed that the inactivation of codY influences virulence properties of several organisms, including Bacillus cereus (25), Streptococcus pyogenes (32, 33), Streptococcus pneumoniae (24), Streptococcus mutans (29), Staphylococcus aureus (31, 44), and Listeria monocytogenes (4). In none of these cases, however, was it possible to identify the relevant direct target of CodY-mediated regulation. In Clostridium difficile, however, CodY is a direct repressor of the gene that encodes an alternative RNA polymerase sigma factor whose activity is essential for toxin gene expression (14).

We report here that a codY-null mutation in B. anthracis compromised virulence in a toxinogenic model of infection. codY disruption altered the expression of more than 200 genes, including the toxin genes. Contrary to our expectation, the disruption of codY led to a significant loss of toxin gene expression. Since disruption of codY caused a decrease in AtxA protein accumulation but did not reduce the level or stability of atxA mRNA or expression of atxA transcriptional and translational fusions to lacZ, we propose that B. anthracis CodY regulates toxin gene expression by posttranslational control of the intracellular concentration of AtxA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The B. anthracis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Growth of cultures was determined by measuring A600. B. anthracis precultures were grown overnight at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) supplemented with 0.5% glycerol with rotary shaking at 150 rpm. Experimental cultures were grown at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 20 ml R medium (48) supplemented with 0.6% sodium bicarbonate (RBic). Sodium bicarbonate was added to R medium to maintain a continuous CO2-bicarbonate equilibrium that is necessary for optimal production of the B. anthracis toxins and capsule (16). RBic medium was inoculated from an overnight culture to a starting A600 of 0.05. Aeration of the culture was achieved by continuous stirring with a magnetic bar at 450 rpm. The antibiotics used were spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (40 μg/ml), and erythromycin (150 μg/ml for Escherichia coli and 5 μg/ml for B. anthracis).

TABLE 1.

B. anthracis strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or nucleotide | Relevant genotype or sequence (5′→3′) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| 7702 | Sterne strain; pXO1+ | Laboratory stock |

| RBAF140 | 7702 pagA-lacZ transcriptional fusion integrated adjacent to pagA | 53 |

| RBAF143 | 7702 lef-lacZ transcriptional fusion integrated adjacent to lef | 53 |

| RBAF144 | 7702 cya-lacZ transcriptional fusion integrated adjacent to cya | 53 |

| 7702-XFI | 7702 atxA-lacZ transcriptional fusion | J.-C. Sirard, personal communication |

| BATX1 | 7702 ΔatxA | 52 |

| 7CodYS | 7702 codY::spc | This study |

| 140CodYS | RBAF140 codY::spc | This study |

| 143CodYS | RBAF143 codY::spc | This study |

| 144CodYS | RBAF144 codY::spc | This study |

| 7CodYSXFI | 7702XFI codY::spc | This study |

| 7702XF5 | 7702 atxA-lacZ translational fusion | This study |

| 7CodYSXF5 | 7702XF5 codY::spc | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC1318Spc | Laboratory stock | 35 |

| pBAD | Expression vector | 21 |

| pBAK | Suicide vector in B. anthracis | 34 |

| pBALA20 | lacZ-carrying vector | 36 |

| pAT187 | Conjugative replicating plasmid used for complementation in B. anthracis; Kanr | 62 |

| pAT113 | Conjugative suicide plasmid | 61 |

| pGEMT-easy | Cloning vector | Promega |

| pQE30 | Expression vector | Qiagen |

| pTAX5 | atxA-harboring plasmid | 20 |

| pSALAC10 | lacZ-harboring plasmid | This study |

| pJP15 | pBAD derivative harboring codY under control of araBAD promoter | This study |

| pAtlac30 | pAT113 derivative harboring atxA-lacZ translational fusion | This study |

| pAtxAc4 | pQE30 derivative harboring atxA | This study |

| pCodY4 | pAT187 derivative harboring codY | This study |

| pCOD30 | pBAK derivative harboring interrupted allele of codY | This study |

| pXF1 | pAT113 derivative harboring atxA-lacZ translational fusion | J.-C. Sirard, personal communication |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| CompCodYF | GCTGGGATCCGAAGATTTATCGTTTGAAGCATCTG | |

| CompCodYR | GGTGGGATCCGAGGAGAGTTTTATAAATTAGTTTG | |

| LacZ-N | GGATCCACCATGATTACGGATTCACTGGCCGTCGTT | |

| LacZ-C | CCCGGTTATTATTATTTTTGACACCAGACC | |

| AtxAF | GGATTCCTAACACCGATATCCATCGAAAAGGAACATATAAG | |

| AtxAR | AAGCTTGGGCATTTATATTATCTTTTTGATTTCATGAAAATCTCTTTCTGTAGG | |

| atxA-F-AC | ACTTTTGCATCCATACGTTCTTGGGCAATT | |

| atxA-R-A | GGATCCTCGGACTGTTTTATCTGCGACCTGTAGATA | |

| oPJ33 | GCGCTTTCAAAAATAGAAGAATACCTCATT | |

| oPJ36 | CCTCCTTCAGGAATATGCTACTAGTTTTAC | |

| oPJ37 | GGTATGGTAATTTTGAAAAATCTAACGCTA | |

| oPJ38 | CGACAAAAAAGTGAATTTTCACAATTCCAA | |

| qPCR-atxA1-F | ACAGGTCGCAGATAAAACAGTCC | |

| qPCR-atxA1-R | GAACAAGTAAATTCCAAGATGGAGGA | |

| qPCR-atxA2-F | TCTGCACTGCTTGAAAAACG | |

| qPCR-atxA2-R | CCATGTCTTGGAGTGATTCGTTA | |

| qPCR-tuf-F | GCCCAGGTCACGCTGACTAT | |

| qPCR-tuf-R | TCACGAGTTTGAGGCATTGG |

Cloning of B. anthracis codY.

The codY coding sequence of B. anthracis strain 7702 was amplified by PCR using primers codY5′ and codY3′ (Table 1), which introduced six histidine codons at the 3′ end of the coding sequence, as well as SacI and SphI restriction sites, respectively, at the ends of the amplicon. The PCR product was cloned in pBAD30 (21), yielding pJP15, in which codY is under the control of the araBAD promoter. This plasmid was used both for mutagenesis of codY and for overexpression of CodY protein for in vitro studies.

Generation of codY mutants in B. anthracis and in trans complementation.

A null mutation in the codY gene was generated by insertion of a spectinomycin resistance cassette at a unique HindIII site at codon 77 of codY. The codY-harboring fragment was obtained by digesting pJP15 with SphI, rendering it blunt, and then digesting it with SacI. The resulting codY-containing fragment was cloned in pBAK (34) that had been digested with HindIII, blunt-ended, and digested with SacI, giving pCOD10. A spectinomycin resistance cassette was ligated to pCOD10 that had been digested with HindIII and blunt-ended. The resulting plasmid, pCOD30, was introduced into E. coli strain HB101(pRK24) and transferred to B. anthracis 7702 by filter mating (42, 62). Spectinomycin-resistant transconjugants were checked by PCR for the occurrence of a double-crossover event and the correct insertion of the spectinomycin resistance cassette within the codY gene. The resulting mutant strain, 7CodYS, served as the donor for introduction of the codY mutation by CP51-mediated transduction (18) into other strains, which eventually also served as subsequent donors. Alternatively, the mutation was transferred by filter mating using E. coli HB101(pRK24)(pCOD30) as the donor.

For complementation of the codY mutation, a DNA segment corresponding to the codY gene and 200 bp of upstream sequence was amplified by PCR with the primers CompCodYF and CompCodYR (Table 1), which introduced BamHI sites at both ends of the product. The PCR fragment was digested with BamHI, blunt-ended, and cloned in the SmaI-digested B. anthracis-E. coli shuttle vector pAT187 (62), creating pCodY4. The absence of mutations in the insert was confirmed by DNA sequencing. pCodY4 was then introduced into E. coli HB101(pRK24) by electroporation and transferred to the B. anthracis codY mutants by filter mating. In this construct, the codY gene is expressed either from a promoter proximal to the codY gene or by read-through from a plasmid promoter.

RNA isolation and transcriptome analysis.

RNA was isolated from B. anthracis cultures (25 ml in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks)grown in RBic medium at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. At A600s of 0.2 and 1.0, 10-ml samples of the cultures were added to 20 ml RNAprotect (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 12,500 × g for 10 min, and after decanting the supernatant, 1 ml TRI reagent (Ambion, Huntingdon, United Kingdom) was added to the cell pellet and RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ambion's Turbo DNA-free kit was used to remove residual DNA from the isolated RNA. Integrity of the extracted RNA was determined by analysis with an Agilent (Palo Alto, CA) 2100 Bioanalyzer according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples were stored in 70% ethanol-83 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.2) at −80°C. Prior to cDNA synthesis, the RNA samples were spun down at 13,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge prechilled to 4°C. The RNA pellet was then washed with 70% ethanol (prechilled to −20°C) and resuspended in RNase-free water. cDNA reactions (containing 5 μg RNA), indirect labeling of cDNA with the fluorescent labels Cy3 and Cy5, and hybridizations of the microarrays were performed as described previously (45). The microarray used was a composite B. cereus-B. anthracis chip that has been described previously (28). For each time point, four arrays were hybridized with quadruplicate independent biological replicates. Two were labeled with Cy3, and the other two were labeled with Cy5 in order to reduce dye-specific effects. Statistical analysis was performed with R software (http://www.r-project.org). No background subtraction was done, but we checked that the background was low and homogeneous in both channels on all arrays. Data were log transformed (log base 2). A global Lowess normalization was applied independently on each array with the limma package (55). Empty and flagged spots were excluded from the data set, and duplicate spot log ratios were then averaged in order to get statistically independent values for each oligonucleotide. Differential analysis was conducted using the varmixt package and the VM method (11, 12). Resulting raw P values were adjusted according to the Benjamini and Yekutieli method (3, 15), and a cutoff of significance was set to 0.05. For each oligonucleotide, the normalized intensity value was computed for each (red and green) channel. Oligonucleotides with a maximum intensity value below 500 over the two channels were not analyzed further. Finally, an additional threshold of significance was introduced at a twofold difference in normalized expression levels.

cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR.

Primers for cDNA synthesis and subsequent PCRs were designed using Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu). cDNA synthesis and real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) were carried out essentially as described previously (65) with tufA as the reference gene on a 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The reactions were carried out on the same RNA samples as those used for the transcriptome analysis, and real-time PCR was performed in triplicate for each sample.

Cloning of B. anthracis atxA, overexpression and purification of AtxA, and anti-AtxA serum preparation.

The atxA coding sequence of B. anthracis strain 7702 was amplified by PCR using primers AtxAF and AtxAR (Table 1), which introduced BamHI and HindIII sites at the ends of the amplicon. The PCR product was cloned in pGEM-T Easy, yielding pAtxAc1. The atxA-harboring fragment was obtained by digesting pAtxAc1 with BamHI and HindIII and inserting it in pQE30 similarly digested, giving pAtxAc4, in which atxA is under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter and the AtxA protein sequence is preceded by a His tag. E. coli M15(pREP4)(pAtxAc4) was grown in L broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (40 μg/ml) to an A600 of 0.6. Expression of the recombinant atxA gene was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG. After 3 h of further incubation, the cells were harvested and AtxA-His6 was found in the insoluble fraction and was purified according to Qiagen's recommendation in the presence of urea. AtxA eluted at 250 mM imidazole. To obtain mouse polyclonal serum to AtxA, four OF/1 mice were injected subcutaneously with 10 μg of AtxA and boosted on days 14, 33, 49, and 63. They were bled on day 77.

Immunoblotting techniques.

To determine the quantities of PA, EF, and LF in culture supernatants during growth of strain 7702 and its codY mutant derivatives, 1-ml samples were taken when the cultures in RBic medium reached A600s of 0.4, 1.0, and 2.5. Proteins in the cell-free culture fluid were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-12% polyacrylamide gels. Subsequent transfer to membranes and immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies against PA, EF, and LF were performed as described previously (8).

After showing that antibodies raised against CodY from B. subtilis (46) cross-react with CodY from B. anthracis (data not shown), we used those antibodies to determine the levels of CodY in exponentially growing cells of strains 7702, 7CodYS, 7CodYS(pCodY4), 140CodYS(pCodY4), and 7CodYSXFI(pCodY4). Whole-cell lysates were subjected to SDS-12% PAGE and immunoblotted essentially as described previously (60).

The antibodies raised against AtxA were assayed for their specificity by immunoblotting experiments. The 7702 and BATX1 (its ΔatxA derivative [52]) strains were grown in RBic medium, and 2.5-ml samples were harvested when the A600 reached 1.0. Proteins from whole-cell lysates were separated by SDS-12% PAGE and immunoblotted (data not shown). At a 1:250 dilution, the sera recognized a single protein, comigrating with AtxA, in the 7702 crude extract and none in the BATX1 crude extract. The levels of AtxA in cells were determined after sampling the cultures at A600, as indicated in the figures.

Construction of atxA-lacZ transcriptional and translational fusions.

The 3.6-kb EcoRI-BamHI pXO1 DNA fragment encompassing atxA was subcloned into pAT113, giving rise to pATX3. The pBALA20 (36) SmaI fragment encompassing the lacZ gene was inserted into the HpaI site of pATX3, and the orientation was checked. Thus, the resultant plasmid, pXF1, harbors upstream of the lacZ gene a fragment that starts 950 bp upstream of the atxA start codon and contains both atxA promoters, the atxA Shine-Dalgarno sequence, the ATG start codon, and the first 437 codons of AtxA.

The atxA promoter region of B. anthracis 7702, starting 593 bp upstream of the ATG codon and encompassing the first 45 codons, was amplified by PCR using primers atxA-F-AC and atxA-R-AC, which introduced a BamHI site at the 3′ end of the amplified DNA fragment (Table 1). It was cloned into pGEM-T Easy, yielding pAtxA50, from which the atxA-containing fragment can be extracted by PstI-BamHI digestion. The lacZ gene, starting at the second codon, was amplified from pSALAC10 using primers LacZ-N and LacZ-C, which introduced a BamHI site overlapping the first codons (Table 1). pSALAC10 had been obtained by digesting pBALA20 (36) with BamHI and BglII and cloning the lacZ gene-harboring DNA fragment into pSAL322 digested with BamHI (35). The lacZ sequence was cloned into pGEM-T Easy, yielding pLac10, in which the BamHI site located at the 5′ end of lacZ is close to the pGEM-T Easy PstI site. The atxA-lacZ translational fusion was constructed by cloning the atxA sequence into pLac10 after a PstI-BamHI digestion. The resulting plasmid, pAtlac10, was digested with PstI and SacI, and the translational fusion was transferred into pAT113 similarly digested, giving rise to pAtlac30.

Plasmids pXF1 and pAtlac30 were introduced into E. coli strain HB101(pRK24) and transferred to the appropriate B. anthracis strains, 7702 and its codY derivative, by filter mating (42).

β-Galactosidase assays.

The accumulation of β-galactosidase by the various lacZ fusion strains was determined as previously described (53) in samples taken during growth in RBic medium at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate; representative results are shown.

Animal experiments.

Female OF1 mice (6 to 8 weeks old; Charles River Laboratories, France) were injected subcutaneously with different amounts of spores of strains 7702 or 7CodYS. Fifty percent lethal doses (LD50s) were estimated by using the method of Reed and Muench (47) with six animals per spore dose. Drawing of Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log rank analysis for evaluating survival differences between the groups were performed with GraphPad Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Spore stocks for the animal experiments were obtained by growing B. anthracis cultures on NBY agar (18) for 5 days at 30°C. Spores were harvested and washed twice in distilled water, heated for 20 min at 65°C to kill vegetative cells, and washed again with distilled water. Spores were then resuspended in distilled water and stored at 4°C before use.

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray results have been submitted to the ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae) under accession no. E-MEXP-1706.

RESULTS

Construction of a codY-null mutant.

The gene encoding CodY was identified in the genome of B. anthracis strain 7702 (pXO1+ pXO2−) by virtue of its sequence similarity to CodY from B. subtilis. The gene BA3966 (NP_846209) is predicted to encode a protein that shares 81% identity with B. subtilis CodY. As in B. subtilis (54), B. anthracis codY is at the 3′ end of a four-gene cluster that includes genes encoding a two-component ATP-dependent protease (ClpQY) and a site-specific recombinase related to XerD. A stem-loop structure with a calculated free energy of formation of −15.8 kcal/mol was found directly downstream of codY. This structure is likely to function as a transcriptional terminator of the codY gene cluster (10). In B. subtilis, the codY operon is located upstream of a large chemotaxis-motility operon, but in B. anthracis, the downstream genes are predicted to encode the translation elongation factor Ts and the 30S ribosomal protein S2. Interestingly, a similar gene arrangement is also seen in several Staphylococcus and Clostridium spp. (44; data not shown).

The B. anthracis codY gene was interrupted in strain 7702 by insertion via allelic exchange of a spectinomycin resistance cassette at the unique HindIII site in the codY gene at position 231 of the 780-bp open reading frame, corresponding to codon 77. The absence of CodY protein in the mutant strain 7CodYS and its presence, at a concentration similar to that in strain 7702, in the complemented strain were demonstrated by immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

CodY is absent from the codY-disrupted strain and can be complemented in trans. B. anthracis 7702, 7CodYS, and the complemented strains 7CodYS(pCodY4), 140CodYS(pCodY4), and 7CodYSXFI(pCodY4) were grown at 37°C in RBic medium under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. At an A600 of 1, aliquots of the cultures were removed. Twenty-four micrograms of each whole-cell lysate was loaded for SDS-12% PAGE, and CodY was detected by immunoblotting with CodY antiserum.

Disruption of codY leads to attenuated virulence in an animal model of infection.

Since CodY represses virulence gene expression in several pathogenic bacterial species, we compared the virulence of the parental strain 7702 and its codY mutant by estimating the dose at which 50% of the mice died (LD50) for each strain after subcutaneous injection. The LD50 for strain 7702 was 3.6 × 105 spores, which is in line with previous studies in this animal model (42). The LD50 of the codY mutant strain was at least 103-fold higher than that for its parent as even the highest dose of 7CodYS spores tested (5 × 108/mouse) did not result in death of mice (data not shown). Thus, in B. anthracis CodY is a virulence activator. The lower virulence of the codY mutant strain could be a consequence of metabolic rearrangements or of the modification of expression of known virulence determinants.

Transcriptome analysis of B. anthracis 7702 and its codY mutant.

To obtain an overview of the genes that are regulated by CodY in B. anthracis, we performed a global transcriptome analysis of the parental 7702 strain and the codY mutant. To minimize growth phase-specific effects, we determined transcript abundance in the two strains at two different points in the growth curve in RBic medium: i.e., at A600s of 0.2 and 1.0, corresponding to the mid- and late-exponential-growth phases. The microarray results indicated that the disruption of codY has major effects on global gene expression in B. anthracis (Table 2). Interestingly, the genes that were more highly expressed in the codY mutant compared to its parent strain were largely conserved between the two time points (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that CodY represses these genes during exponential growth. We found a considerably smaller number of genes that had higher transcript levels in 7702 than in the codY mutant; only 25 of these genes were differentially expressed at both time points (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Number of genes exhibiting significant difference in gene expression between B. anthracis 7702 and its codY mutant, 7CodYS, at different points in the growth phase

| Parameter | No. of genes with significant difference

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| A600 of 0.2 | A600 of 1.0 | Overlap between both time pointsa | |

| Higher expression in 7CodYS | 281 | 251 | 182 |

| Higher expression in 7702 | 114 | 85 | 25 |

The number of genes which are significantly up- or downregulated at both time points in the growth curve.

Only 28 of the 182 B. anthracis genes that are negatively regulated by CodY throughout exponential growth have homologs in B. subtilis that are repressed by CodY (39). This group includes genes from a large putative operon (BA1416 to BA1423) that is likely to be involved in the biosynthesis of BCAAs and is very strongly derepressed in the codY mutant strain. In general, the functional categories of putative CodY-repressed genes in B. anthracis were very similar to those in B. subtilis. The main cellular processes affected by CodY in B. anthracis are the biosynthesis of certain amino acids (isoleucine, valine, leucine, histidine, and glutamate), the transport of amino acids and peptides, the pentose pathway, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and acetyl coenzyme A synthesis, mirroring the situation in B. subtilis (39).

Of the 25 genes that exhibited higher expression in 7702 than in the codY mutant at both time points, most do not share an obvious functional role. However, at both time points, the lef and cya genes were expressed at a three- to fourfold-higher level in 7702 than in the codY mutant. In the sample taken at an A600 of 1.0, pagA was also more highly expressed (3.5-fold) in 7702 than in the mutant strain. The lower toxin gene expression could account for the lower virulence of the mutant strain. Interestingly, atxA gene expression was not affected by the codY mutation.

Recently, a consensus CodY-binding sequence (AATTTTCNGAAAATT) has been proposed for L. lactis (13) and this sequence has been suggested to be present upstream of many CodY-repressed genes in various low-G+C gram-positive bacteria (19). To determine the relevance of this proposed CodY-binding site in B. anthracis, the genome of B. anthracis Ames was searched with the CodY box consensus sequence with two mismatches accepted, within 300 nucleotides (nt) upstream and 100 nt downstream of a gene's translational start site. This analysis revealed the presence of 101 highly conserved CodY boxes in the B. anthracis chromosome. Such boxes were found upstream of several genes that were identified in the transcriptome analysis, such as the strongly repressed BA1416-BA1423 operon and the more moderately repressed genes BA2997, BA3315, BA3645, and BA5666. This analysis suggests that B. anthracis CodY recognizes a specific DNA sequence, but this sequence may be rather flexible, as has also been suggested for B. subtilis CodY (2). Genes that are derepressed in the codY mutant but lack any obvious CodY box-like sequence are presumably regulated indirectly by CodY. They may be genes that are regulated by a protein whose synthesis is under CodY control or whose activity is altered in response to the metabolic rearrangements that result from the disruption of codY, as hypothesized in S. pyogenes (32, 33).

CodY is required for toxin synthesis.

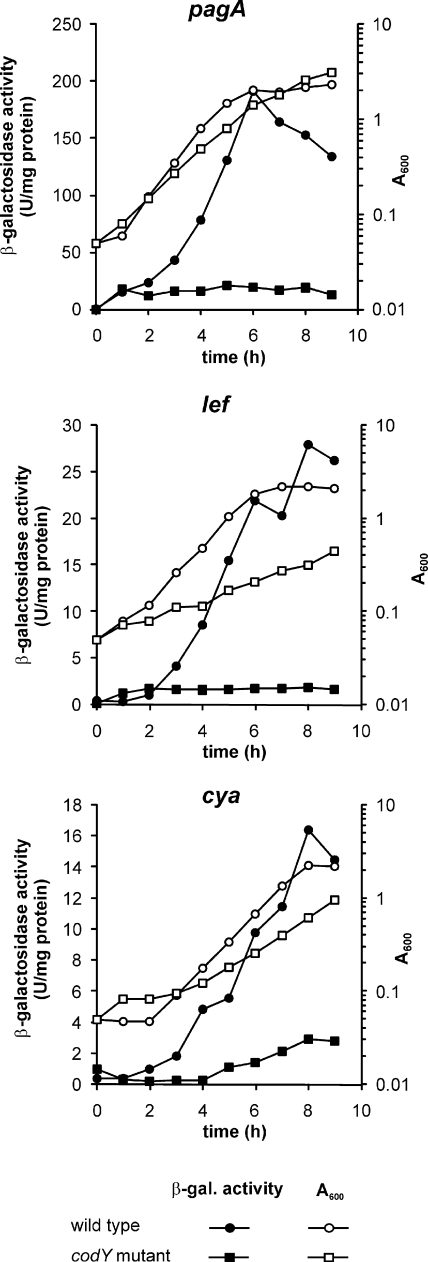

To confirm that the codY mutation affects transcription of the toxin genes and to quantitate such an effect, the codY mutation was transferred by transduction to three strains that carry fusions of a lacZ reporter gene to the promoters of cya, lef, or pagA (53). The β-galactosidase activity during growth of the strains in RBic medium was determined (Fig. 2). In strain 7702, transcription of the toxin genes reached maximum levels during the late exponential phase, corresponding to previously published data (53). In the codY mutant, in contrast, transcription of the toxin genes was at a very much lower level than in the parental strain, but was not completely abolished. In the first few hours of culture, there was little expression of cya, lef, and pagA in either strain. However, while in the parental strain transcription of the toxin genes increased rapidly from the mid-exponential phase onward, expression in the codY mutant strain remained at a low, constant level throughout growth.

FIG. 2.

CodY regulates toxin gene expression. Transcription of pagA, lef, and cya in codY wild-type B. anthracis strains and their respective codY disruption mutants was assessed. B. anthracis RBAF140, RBAF143, and RBAF144 (circles) and their codY mutants (squares) were grown in RBic medium under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Growth was monitored by A600 measurements (open symbols), and transcription of pagA, lef, and cya was determined by measuring β-galactosidase activity (closed symbols). Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. In all three independent experiments, the observed differences were found to be statistically significant, with P values (paired Wilcoxon test) of 0.009, 0.014, and 0.002 for the pagA-lacZ-harboring strains; 0.031, 0.020, and 0.010 for the lef-lacZ-harboring strains; and 0.020, 0.006, and 0.002 for the cya-lacZ-harboring strains.

Whether CodY is a direct regulator of the toxin component genes was tested using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (P. Joseph, personal communication). Binding of CodY to the pag, lef, and cya promoter regions was only seen at high protein concentrations (dissociation constant [Kd] of >256 nM), similar to the concentration that gave nonspecific binding to the B. subtilis polC negative control probe.

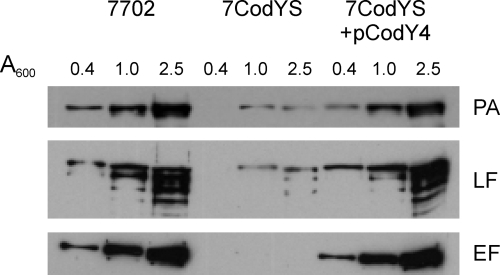

To see if the effect of the codY mutation on toxin gene expression was reflected in toxin protein levels, we measured the amounts of the three toxin components in trichloroacetic acid-precipitated culture supernatant samples obtained during growth of strains 7702 and 7CodYS in RBic medium. Samples were taken at the mid-exponential, late-exponential, and early-stationary-phase time points. Immunoblotting revealed that the accumulation of all three toxin components was, at all time points, considerably lower in the codY mutant than in the parental strain (Fig. 3). The production of the toxin components in the codY mutant was restored by complementation in trans with a multicopy vector that carries the codY coding sequence and 200 bp of upstream DNA (Fig. 3). Thus, the defect in toxin protein accumulation in the codY mutant strain must be due to the absence of CodY and not to any potential effect of the insertion mutation on expression of genes downstream of codY in the chromosome. Similarly, CodY is required for maximal toxin gene expression.

FIG. 3.

CodY regulates toxin component accumulation. B. anthracis 7702, 7CodYS, and the complemented strain 7CodYS(pCodY4) were grown in RBic medium under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and accumulation of PA, LF, and EF in the supernatant was monitored. At the indicated cell densities, aliquots of the cultures were removed. Proteins in the culture supernatant were precipitated, and toxin subunits were detected by immunoblotting with PA-, LF-, and EF-specific monoclonal antibodies.

CodY regulates AtxA accumulation without affecting atxA transcription or translation initiation or RNA stability.

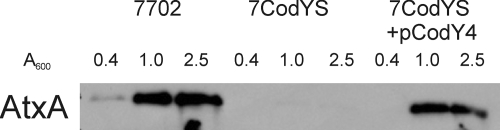

Since AtxA is required for expression of the toxin component genes, one could hypothesize that CodY activates toxin gene expression indirectly by stimulating synthesis of AtxA. In fact, when the amount of AtxA was monitored in crude extracts obtained during growth in RBic (Fig. 4), we found a much lower level of AtxA accumulation in the codY mutant than in the parental strain at the mid-exponential, late-exponential, and early-stationary-phase time points. This effect parallels that seen for toxin component accumulation but was surprising given that the microarray data indicated no significant difference in atxA transcript levels between these strains (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). When we tested the effect of a codY mutation on expression of an atxA-lacZ transcriptional fusion, we found that atxA expression was very similar in the codY mutant and in the parental 7702 strain (Fig. 5A). A small (less than threefold) overexpression of atxA was observed in the codY mutant soon after inoculation of RBic medium. However, from the mid-exponential phase onwards, when the difference in toxin gene expression between the codY mutant and the parental strain was becoming increasingly obvious, β- galactosidase activity increased similarly and was at the same level in both strains (Fig. 5A). These results confirm the data obtained during our microarray experiments (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 4.

CodY affects AtxA accumulation. B. anthracis 7702, 7CodYS, and the complemented strain 7CodYS(pCodY4) were grown in RBic medium under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and AtxA accumulation was monitored. At the indicated cell densities, aliquots of the cultures were removed. Whole-cell lysates were loaded, and AtxA was detected by immunoblotting with specific anti-AtxA serum.

FIG. 5.

CodY does not affect transcription or translation of atxA. Transcription (A) and translation (B) of atxA in parental B. anthracis and their codY disruption mutant are shown. B. anthracis 7702-XFI (circles) and its codY mutant (squares) (A) and B. anthracis 7702-XF5 (circles) and its codY mutant (squares) (B) were grown in RBic medium under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Growth was monitored by A600 measurements (open symbols), and transcription or translation of atxA was determined by measuring β-galactosidase (β-gal.) activity (closed symbols). The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. In none of these experiments was a statistical difference found (paired Wilcoxon's test), with P values between 0.074 and 0.734 for the transcriptional fusion-harboring strains and 0.052 and 0.734 for the translational fusion-harboring strains.

The lack of correlation between the effects of CodY on an atxA-lacZ transcriptional fusion and on toxin gene expression is not at all consistent with a model whereby CodY controls toxin gene expression by modulating the transcription of atxA. Furthermore, the locations of the transcriptional fusion (at nt 1341 with respect to the ATG translation initiation codon) and of the oligonucleotide probe used in the microarray (corresponding to nt 707 to 776) argue against a model in which CodY controls atxA mRNA stability. Nevertheless, we tested this possibility. qRT-PCR experiments were carried out with two pairs of oligonucleotides, one pair that anneals close to the 5′ end of the coding sequence (covering nt 111 to 190) and one pair that anneals close to the 3′ end (from nt 1225 to 1315) of the atxA gene. The amount of the 3′-end atxA fragment was slightly lower than that of the 5′-end fragment. Interestingly, the ratios of the relative amounts of the 5′-end product or of the 3′-end product in the codY mutant strain versus the parental strain were not significantly different at an A600 of 0.2 (0.703 ± 0.163 and 0.584 ± 0.086 for the 5′- and 3′-end products, respectively) or at an A600 of 1.0 (0.685 ± 0.133 and 0.637 ± 0.107 for the 5′- and 3′-end products, respectively). These results indicate that CodY does not affect atxA mRNA abundance or stability. That is, the slight difference in atxA transcript levels between the 7702 strain and the codY mutant does not account for the large difference in AtxA protein abundance.

An alternative possibility is that CodY affects atxA mRNA translation. To test this hypothesis, an atxA-lacZ translational fusion was constructed. This construct contained the complete atxA regulatory region, its Shine-Dalgarno sequence, and the first 45 codons of the atxA gene fused in-frame to a lacZ gene devoid of its translation initiation codon. This fusion was integrated at the atxA locus in the parental and codY mutant strains. The strains were grown in RBic medium under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and β-galactosidase activity was monitored (Fig. 5B). The expression of the translational fusion paralleled that of the transcriptional fusion: β-galactosidase activity was slightly higher (twofold) in the mutant strain than in the parental strain during the early exponential phase (again opposite to what was observed at the protein level) and at later time points was identical in both strains. This result indicates that CodY does not control the initiation of translation of atxA mRNA. Altogether, these data show that the disruption of codY does not affect atxA expression or translation but indicate that in the codY mutant AtxA accumulation is affected at the posttranslational level.

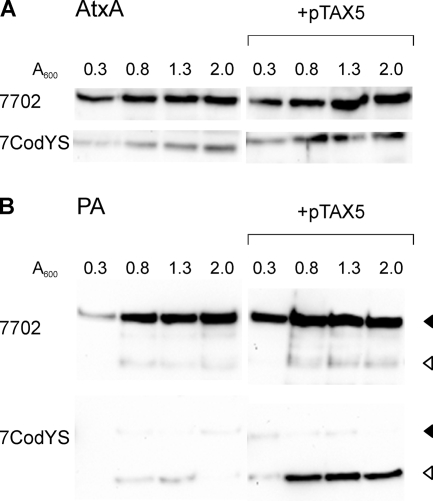

CodY controls toxin gene transcription by controlling AtxA accumulation.

To test if the lower level of AtxA in the codY mutant is responsible for the lower toxin gene expression, an atxA-harboring multicopy plasmid (pTAX5) was introduced into a codY mutant strain. Overexpression of atxA led to higher accumulation of AtxA, indicating that oversynthesis of AtxA bypasses the accumulation defect observed in the codY mutant strain (Fig. 6). A higher accumulation of PA in the culture fluid was also observed in the codY strain harboring pTAX5, suggesting that CodY regulates toxin gene expression by controlling the AtxA level. Interestingly, a degradation product of PA was seen in these experiments, suggesting that the culture fluid of a codY mutant strain has increased protease activity.

FIG. 6.

CodY controls toxin synthesis via AtxA accumulation. B. anthracis 7702, 7CodYS, and their pTAX5-harboring derivatives were grown in RBic medium under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and accumulation of AtxA in the crude extract (A) and PA in the supernatant fluid (B) was monitored. At the indicated cell densities, samples of the cultures were removed. Whole-cell lysates or precipitated proteins from the culture supernatant were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and AtxA or PA was detected by immunoblotting with AtxA- or PA-specific antibodies. Solid and empty arrowheads indicate native and hydrolyzed PA, respectively.

DISCUSSION

As shown here, inactivation of the B. anthracis codY gene results in a severe defect in virulence in a mouse model of infection by a toxinogenic but noncapsulated strain. The codY disruption also led to significantly lower production of anthrax toxin components, and this may be the primary cause for the lack of virulence. Yet, the involvement of other factors cannot be excluded as suggested by our microarray experiments. For example, in the codY mutant the expression of genes involved in uptake and detoxification of iron and in important metabolic pathways, such as the synthesis of BCAAs, is also affected; these changes may contribute to lower virulence. However, because the anthrax toxin is the main determinant of virulence in this particular genetic background (67), it seems likely that the dramatic decrease in toxin production in the codY mutant is the main cause of the avirulent nature of this strain.

The reduced production of toxin proteins in the codY mutant is most easily attributed to a dramatically lower accumulation of the AtxA protein. Since CodY has a negligible effect on atxA mRNA accumulation or stability (as detected by microarray and qRT-PCR) or on expression of atxA-lacZ transcriptional or translational fusions, CodY appears to act posttranslationally. How it would do so is currently unknown, but it seems most likely that the disruption of CodY leads to the synthesis of a factor, such as a protease, chaperone, or adaptor protein, that directly influences AtxA stability. We favor the protease hypothesis because atxA overexpression in the codY mutant strain leads to increased AtxA accumulation. Since the accumulation of AtxA is thought to be the major factor determining the rate of expression of the toxin genes, and since enhanced AtxA accumulation restored PA accumulation in the codY mutant strain, we conclude that CodY, like other B. anthracis regulators, influences toxin gene expression via AtxA.

CodY acts as a global regulator in several low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria, repressing during rapid exponential growth genes that are later induced during nutrient limitation (4, 13, 14, 19, 24, 29, 31, 33, 39, 57). Whereas in C. difficile CodY directly represses expression of toxin genes (14), in B. anthracis it activates toxin genes and does so indirectly. The fact that a conserved regulator controls genes with related functional roles in an organism-specific manner illustrates the flexibility of bacterial regulatory systems throughout their evolutionary history (30, 66). The results presented here widen the scope of the factors that are involved in B. anthracis virulence gene expression. By responding to nutrient availability, CodY links the expression of B. anthracis virulence factors to overall cellular physiology and metabolism. Such finely tuned coupling is likely to benefit the bacterium in adapting to various environments within the host.

Whereas in C. difficile, CodY represses toxin gene expression, in B. anthracis CodY activates toxin synthesis. A difference between these two pathogens resides in the tissue context in which these bacteria thrive. The CodY-dependent regulation of toxin levels may reflect a B. anthracis-specific adaptation to specialized niches, such as the lymphoid tissue. Unfortunately, little is known about the BCAA concentration or energy status in the diverse extracellular loci in which B. anthracis resides during infection (5), and therefore it remains to be determined which in vivo signals are contributing to the effects of CodY on toxin production in B. anthracis during infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Mock, in whose lab part of the work was carried out; P. Joseph for helpful discussions and permission to cite her unpublished data; P. Domaingue, M. Haustant, M. Monot, J. Prigent, F. Smeets, and M. Schwartz for technical help; and A.-B. Kolstø for kindly providing the microarrays.

W.V.S. and A.C. were funded through an EMBO Long Term Fellowship and fellowship from the DGA, respectively. This work was supported in part by a research grant (GM042219 to A.L.S.) from the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 August 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldari, C. T., F. Tonello, S. R. Paccani, and C. Montecucco. 2006. Anthrax toxins: a paradigm of bacterial immune suppression. Trends Immunol. 27:434-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belitsky, B. R., and A. L. Sonenshein. 2008. Genetic and biochemical analysis of CodY-binding sites in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 190:1224-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamini, Y., and D. Yekutieli. 2001. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 29:1165-1188. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, H. J., D. M. Pearce, S. Glenn, C. M. Taylor, M. Kuhn, A. L. Sonenshein, P. W. Andrew, and I. S. Roberts. 2007. Characterization of relA and codY mutants of Listeria monocytogenes: identification of the CodY regulon and its role in virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1453-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein, S. E. 1966. Physiological characteristics, p. 337-350. In E. L. Green (ed.), Biology of the laboratory mouse, 2nd ed. Dover Publications, New York, NY.

- 6.Bongiorni, C., T. Fukushima, A. C. Wilson, C. Chiang, M. C. Mansilla, J. A. Hoch, and M. Perego. 2008. Dual promoters control expression of the Bacillus anthracis virulence factor AtxA. J. Bacteriol. 190:6483-6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourgogne, A., M. Drysdale, S. G. Hilsenbeck, S. N. Peterson, and T. M. Koehler. 2003. Global effects of virulence gene regulators in a Bacillus anthracis strain with both virulence plasmids. Infect. Immun. 71:2736-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brossier, F., M. Weber-Levy, M. Mock, and J.-C. Sirard. 2000. Role of toxin functional domains in anthrax pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 68:1781-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Candela, T., M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 2005. CapE, a 47-amino-acid peptide, is necessary for Bacillus anthracis polyglutamate capsule synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 187:7765-7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Hoon, M. J. L., Y. Makita, K. Nakai, and S. Miyano. 2005. Prediction of transcriptional terminators in Bacillus subtilis and related species. PLoS Comput. Biol. 1:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmar, P., S. Robin, D. Tronik-Le Roux, and J. J. Daudin. 2005. Mixture model on the variance for the differential analysis of gene expression data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C 54:31-50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delmar, P., S. Robin, and J. J. Daudin. 2005. VarMixt: efficient variance modelling for the differential analysis of replicated gene expression data. Bioinformatics 21:502-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.den Hengst, C. D., S. A. F. T. van Hijum, J. M. W. Geurts, A. Nauta, J. Kok, and O. P. Kuipers. 2005. The Lactococcus lactis CodY regulon: identification of a conserved cis-regulatory element. J. Biol. Chem. 280:34332-34342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dineen, S. S., A. C. Villapakkam, J. T. Nordman, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2007. Repression of Clostridium difficile toxin gene expression by CodY. Mol. Microbiol. 66:206-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudoit, S., J. P. Shaffer, and J. C. Boldrick. 2003. Multiple hypothesis testing in microarray experiments. Stat. Sci. 18:71-103. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fouet, A., and M. Mock. 1996. Differential influence of the two Bacillus anthracis plasmids on regulation of virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 64:4928-4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouet, A., and M. Mock. 2006. Regulatory networks for virulence and persistence of Bacillus anthracis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:160-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green, B. D., L. Battisti, T. M. Koehler, C. B. Thorne, and B. E. Ivins. 1985. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 49:291-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guédon, E., B. Sperandio, N. Pons, S. D. Ehrlich, and P. Renault. 2005. Overall control of nitrogen metabolism in Lactococcus lactis by CodY, and possible models for CodY regulation in Firmicutes. Microbiology 151:3895-3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guignot, J., M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 1997. AtxA activates the transcription of genes harbored by both Bacillus anthracis virulence plasmids. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 147:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzman, L.-M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadjifrangiskou, M., Y. Chen, and T. M. Koehler. 2007. The alternative sigma factor σH is required for toxin gene expression by Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 189:1874-1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handke, L. D., R. P. Shivers, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2008. Interaction of Bacillus subtilis CodY with GTP. J. Bacteriol. 190:798-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendriksen, W. T., H. J. Bootsma, S. Estevão, T. Hoogenboezem, A. de Jong, R. de Groot, O. P. Kuipers, and P. W. M. Hermans. 2008. CodY of Streptococcus pneumoniae: link between nutritional gene regulation and colonization. J. Bacteriol. 190:590-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsueh, Y., E. B. Somers, and A. C. L. Wong. 2008. Characterization of the codY gene and its influence on biofilm formation in Bacillus cereus. Arch. Microbiol. 189:557-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch, R. 1876. Die Aetiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus anthracis. Beitr. Biol. Pflanz. 2:277-310. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koehler, T. M., Z. Dai, and M. Kaufman-Yarbray. 1994. Regulation of the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen gene: CO2 and a trans-acting element activate transcription from one of two promoters. J. Bacteriol. 176:586-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kristoffersen, S. M., S. Ravnum, N. J. Tourasse, O. A. Økstad, A.-B. Kolstø, and W. Davies. 2007. Low concentrations of bile salts induce stress responses and reduce motility in Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579. J. Bacteriol. 189:5302-5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemos, J. A., M. M. Nascimento, V. K. Lin, J. Abranches, and R. A. Burne. 2008. Global regulation by (p)ppGpp and CodY in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 190:5291-5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lozada-Chávez, I., S. C. Janga, and J. Collado-Vides. 2006. Bacterial regulatory networks are extremely flexible in evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:3434-3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majerczyk, C. D., M. R. Sadykov, T. T. Luong, C. Lee, G. A. Somerville, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus CodY negatively regulates virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 190:2257-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malke, H., and J. J. Ferretti. 2007. CodY-affected transcriptional gene expression of Streptococcus pyogenes during growth in human blood. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:707-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malke, H., K. Steiner, W. M. McShan, and J. J. Ferretti. 2006. Linking the nutritional status of Streptococcus pyogenes to alteration of transcriptional gene expression: the action of CodY and RelA. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296:259-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mesnage, S., E. Tosi-Couture, and A. Fouet. 1999. Production and cell surface anchoring of functional fusions between the SLH motifs of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer proteins and the Bacillus subtilis levansucrase. Mol. Microbiol. 31:927-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mesnage, S., E. Tosi-Couture, M. Mock, P. Gounon, and A. Fouet. 1997. Molecular characterization of the Bacillus anthracis main S-layer component: evidence that it is the major cell-associated antigen. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1147-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mignot, T., S. Mesnage, E. Couture-Tosi, M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 2002. Developmental switch of S-layer protein synthesis in Bacillus anthracis. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1615-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mignot, T., M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 2003. A plasmid-encoded regulator couples the synthesis of toxins and surface structures in Bacillus anthracis. Mol. Microbiol. 47:917-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mock, M., and A. Fouet. 2001. Anthrax. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:647-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molle, V., Y. Nakaura, R. P. Shivers, H. Yamaguchi, R. Losick, Y. Fujita, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2003. Additional targets of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation and genome-wide transcript analysis. J. Bacteriol. 185:1911-1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okinaka, R. T., K. Cloud, O. Hampton, A. R. Hoffmaster, K. K. Hill, P. Keim, T. M. Koehler, G. Lamke, S. Kumano, J. Mahillon, D. Manter, Y. Martinez, D. Ricke, R. Svensson, and P. J. Jackson. 1999. Sequence and organization of pXO1, the large Bacillus anthracis plasmid harboring the anthrax toxin genes. J. Bacteriol. 181:6509-6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perego, M., and J. A. Hoch. 2008. Commingling regulatory systems following acquisition of virulence plasmids by Bacillus anthracis. Trends Microbiol. 16:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pezard, C., P. Berche, and M. Mock. 1991. Contribution of individual toxin components to virulence of Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 59:3472-3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips, Z. E. V., and M. A. Strauch. 2002. Bacillus subtilis sporulation and stationary phase gene expression. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:392-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pohl, K., P. Francois, L. Stenz, F. Schlink, T. Geiger, S. Herbert, C. Goerke, J. Schrenzel, and C. Wolz. 2009. CodY in Staphylococcus aureus: a regulatory link between metabolism and virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 191:2953-2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ralph, S. A., E. Bischoff, D. Mattei, O. Sismeiro, M. Dillies, G. Guigon, J. Coppee, P. H. David, and A. Scherf. 2005. Transcriptome analysis of antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum—var silencing is not dependent on antisense RNA. Genome Biol. 6:R93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ratnayake-Lecamwasam, M., P. Serror, K. W. Wong, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2001. Bacillus subtilis CodY represses early-stationary-phase genes by sensing GTP levels. Genes Dev. 15:1093-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 27:493. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ristroph, J. D., and B. E. Ivins. 1983. Elaboration of Bacillus anthracis antigens in a new, defined culture medium. Infect. Immun. 39:483-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saile, E., and T. M. Koehler. 2002. Control of anthrax toxin gene expression by the transition state regulator abrB. J. Bacteriol. 184:370-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shivers, R. P., S. S. Dineen, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2006. Positive regulation of Bacillus subtilis ackA by CodY and CcpA: establishing a potential hierarchy in carbon flow. Mol. Microbiol. 62:811-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shivers, R. P., and A. L. Sonenshein. 2004. Activation of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY by direct interaction with branched-chain amino acids. Mol. Microbiol. 53:599-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sirard, J. C., C. Guidi-Rontani, A. Fouet, and M. Mock. 2000. Characterization of a plasmid region involved in Bacillus anthracis toxin production and pathogenesis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:313-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sirard, J.-C., M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 1994. The three Bacillus anthracis toxin genes are coordinately regulated by bicarbonate and temperature. J. Bacteriol. 176:5188-5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slack, F. J., P. Serror, E. Joyce, and A. L. Sonenshein. 1995. A gene required for nutritional repression of the Bacillus subtilis dipeptide permease operon. Mol. Microbiol. 15:689-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smyth, G. K., and T. Speed. 2003. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31:265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soga, T., Y. Ohashi, Y. Ueno, H. Naraoka, M. Tomita, and T. Nishioka. 2003. Quantitative metabolome analysis using capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2:488-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sonenshein, A. L. 2005. CodY, a global regulator of stationary phase and virulence in Gram-positive bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sonenshein, A. L. 2007. Control of key metabolic intersections in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:917-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strauch, M. A., P. Ballar, A. J. Rowshan, and K. L. Zoller. 2005. The DNA-binding specificity of the Bacillus anthracis AbrB protein. Microbiology 151:1751-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sylvestre, P., E. Couture-Tosi, and M. Mock. 2005. Contribution of ExsFA and ExsFB proteins to the localization of BclA on the spore surface and to the stability of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. J. Bacteriol. 187:5122-5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trieu-Cuot, P., C. Carlier, C. Poyart-Salmeron, and P. Courvalin. 1991. An integrative vector exploiting the transposition properties of Tn1545 for insertional mutagenesis and cloning of genes from gram-positive bacteria. Gene 106:21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trieu-Cuot, P., C. Carlier, P. Martin, and P. Courvalin. 1987. Plasmid transfer by conjugation from Escherichia coli to Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 48:289-294. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsvetanova, B., A. C. Wilson, C. Bongiorni, C. Chiang, J. A. Hoch, and M. Perego. 2007. Opposing effects of histidine phosphorylation regulate the AtxA virulence transcription factor in Bacillus anthracis. Mol. Microbiol. 63:644-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uchida, I., J. M. Hornung, C. B. Thorne, K. R. Klimpel, and S. H. Leppla. 1993. Cloning and characterization of a gene whose product is a trans-activator of anthrax toxin synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 175:5329-5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Schaik, W., M. H. Tempelaars, M. H. Zwietering, W. M. de Vos, and T. Abee. 2005. Analysis of the role of RsbV, RsbW, and RsbY in regulating σB activity in Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 187:5846-5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Schaik, W., M. van der Voort, D. Molenaar, R. Moezelaar, W. M. de Vos, and T. Abee. 2007. Identification of the σB regulon of Bacillus cereus and conservation of σB-regulated genes in low-GC-content gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 189:4384-4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Welkos, S. L., and A. M. Friedlander. 1988. Pathogenesis and genetic control of resistance to the Sterne strain of Bacillus anthracis. Microb. Pathog. 4:53-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.