Abstract

The results of seroepidemiological studies suggest that infection with adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) is negatively correlated with the incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cervical cancer. We studied the potential of AAV2 oncosuppression of HPV and showed that HPV/AAV2 coinfection of cells culminated in apoptotic death, as determined by DNA laddering and caspase-3 cleavage. The induction of apoptosis coincided with AAV2 Rep protein expression; increased S-phase progression; upregulated pRb displaying both hyper- and hypophosphorylated forms; increased levels of p21WAF1, p16INK4, and p27KIP1 proteins; and diminished levels of E7 oncoprotein. In contrast, normal keratinocytes that were infected with AAV2 or transfected with the cloned full-length AAV2 genome failed to express Rep proteins or undergo apoptosis. The failure of AAV2 to productively infect normal keratinocytes could be clinically advantageous. The delineation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the HPV/AAV2 interaction could be harnessed for developing novel AAV2-derived therapeutics for cervical cancer.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive cervical cancer patients exhibit antibodies to adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) less frequently than matched controls (27), suggesting that AAV2 has a “protective” effect against the development of this cancer (19). AAV2 is a nonpathogenic, 4.7-kb single-stranded DNA parvovirus (8) with tumor-suppressive properties (37). AAV2 has been detected in cervical tissues (17) and found colocalized with HPV (15, 41). We have reported that in HPV/AAV2-coinfected organotypic cultures, AAV2 inhibited HPV genome amplification concomitant with active AAV2 DNA replication (29). AAV2 inhibition of HPV replication displayed a typical helper/parasite relationship similar to that between AAV2 and adenoviruses (11). The AAV2-encoded nonstructural Rep78 protein inhibited cellular transformation mediated by papillomaviruses in vitro (19), which was due to Rep protein-mediated transcriptional inhibition from the papillomavirus early promoters (20). AAV2 also targets key cell cycle checkpoints. In adenovirus/AAV2-coinfected cells, Rep78 antagonizes the expression and activity of pRb (4) and E2F (5), thus decreasing S-phase progression. Consequently, cell cycle proteins targeted by adenovirus-mediated deregulation subsequently become subject to AAV2-mediated “reregulation.” AAV2 also interferes with cellular proliferation by implementing cell cycle blocks and growth arrest (3, 18, 23, 42) and differentiation (2). Recently, AAV2 was shown to induce a moderate degree of caspase activation during adenovirus coinfection (40).

We have begun characterizing potential mechanisms of AAV2 suppression of HPV oncogenesis. We have reported that in HPV/AAV2-coinfected cultures, AAV2 targeted the p21WAF1 cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor for accelerated proteosome-mediated degradation (1). In contrast, AAV2 infection of primary human keratinocytes (HK) resulted in upregulated p21WAF1 protein levels (1), which was previously correlated with growth arrest in AAV2-infected primary fibroblasts (18). Since in normal cells, p21WAF1 protein levels are decreased in preparation for S-phase entry and progression (25), our observations appeared to contradict the role of AAV2 as a tumor-suppressive parvovirus. To further investigate this observation, we characterized the downstream consequences of AAV2 infection in actively cycling HPV-infected cells.

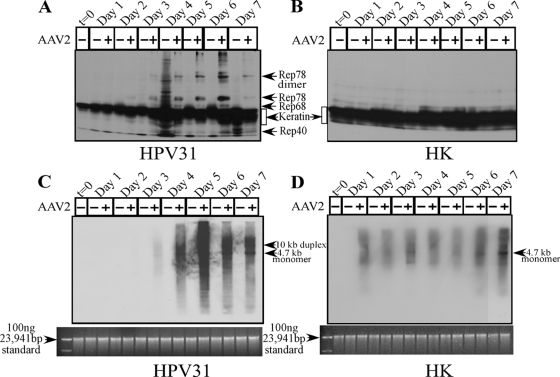

We used the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) type I biopsy-derived cell line CIN-612 9E which maintains episomal genomes of HPV type 31b (HPV31b) (6). As controls, we used HK cells isolated as described previously (1). Using keratinocytes was relevant to our studies as they are natural hosts for both HPV and AAV2 (17). Cells were synchronized as described previously (1). AAV2 viral stocks were prepared and infections performed as we have previously described (1). We used 0.02 multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of AAV2 (using AAV2 MOIs of 10, 20, 30, and 100 yielded similar results). Both AAV2-infected and mock-infected cells were grown to 80% confluence (day 2), at which time the cells were passaged at a ratio of 1:2. On day 3, HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells showed growth retardation, which eventually culminated in complete apoptotic cell death as evidenced by DNA laddering (Fig. 1A). In contrast, AAV2 infection of HK cells did not induce apoptosis (Fig. 1B). The induction of apoptosis correlated with caspase-3 cleavage/activation in AAV2-infected HPV31 cells (Fig. 1C), whereas infected HK cells displayed only the pro-caspase-3 form (Fig. 1D). These experiments have been repeated multiple times with reproducible results.

FIG. 1.

AAV2-induced apoptosis in HPV31-infected cells. (A and B) CIN-612 9E (HPV31 positive) (A) and HK (HPV negative) (B) monolayer cultures were synchronized in G1, followed by infection with AAV2 at an MOI of 0.02. Cell pellets were collected each day over a seven-day period. Cells were passaged 1:2 on day 2. DNA laddering assays were performed by isolating low-molecular-weight DNA using standard protocols. Twenty micrograms of DNA was resolved in a 1% agarose-Tris-borate-EDTA gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Detection of caspase-3 cleavage/activation was done by Western blotting. Total protein extracts were prepared and detected as described previously (1). (C and D) Sixty micrograms of total protein extracts from HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (C) and HK cells infected with AAV2 (D) were resolved in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels. To detect the procaspase form, protein samples were resolved in 10% SDS-PAGE gels and detected with caspase-3 rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). To detect the 19-kDa and 17-kDa cleaved caspase-3 forms, protein samples were resolved in 15% SDS-PAGE gels and detected with cleaved caspase-3 rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Results shown are representative of three individual experiments. t, time; +, present; −, absent.

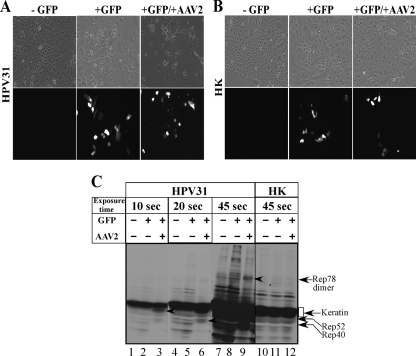

AAV2 encodes four nonstructural proteins, of which Rep78 and Rep68 regulate multiple viral functions, including DNA replication and transcription, whereas Rep52 and Rep40 are involved in packaging viral genomes into capsids (8). The Rep78, Rep68, and Rep40 proteins were clearly expressed in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells beginning on day 3 and continuing up to day 7 (Fig. 2A), but they were not expressed in AAV2-infected HK cells (Fig. 2B). The clarification of Rep52 expression was rendered difficult by the overabundance of contaminating cellular keratins which also resolve in this region. We consistently detected the dimer form of Rep78 (Fig. 2A). This is not uncommon, since others have also reported observing high-molecular-weight Rep78 complexes, which are essentially Rep-Rep protein concatemers containing two to six Rep proteins which persist in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (24, 31). Rep protein expression preceded apoptotic DNA laddering, which was observed on day 4 but increased on day 5 (Fig. 1A). Previously, the expression of Rep78 alone was shown to be sufficient for caspase-3 cleavage and the induction of apoptosis in HL60 cells in vitro (38). To rule out the possibility that the failure of AAV2-infected HK cells to express Rep proteins was due to inability of the virus to infect these cells, we performed Southern blot analysis to detect the status of AAV2 DNA replication. The 4.7-kb replicative-form DNA monomer was detectable in both HPV31/AAV2-coinfected (Fig. 2C) and AAV2-infected HK cells (Fig. 2D). In contrast, Rep proteins were expressed only in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that the induction of apoptosis in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells was due to the expression of Rep proteins.

FIG. 2.

AAV2 induction of apoptosis in HPV31-infected cells correlates with Rep protein expression. For detecting Rep proteins in Western blots, total protein extracts were prepared as we have previously described (1). (A and B) Sixty micrograms of total protein extracts from HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (A) and HK cells infected with AAV2 (B) were resolved in a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and detected with an AAV2 Rep-specific antibody (Progen). (C and D) Southern blot analysis to detect 4.7-kb AAV2 replicative-form monomer representing active genome replication in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (C) and HK cells infected with AAV2 (D). A total of 5 μg of total DNA was then detected with AAV2 genomic DNA as probe as previously described (29). One hundred nanograms of total DNA isolated from cells was used as loading control (bottom). Results shown are representative of three individual experiments. t, time; +, present; −, absent.

We also observed that the 4.7-kb replicative form of AAV2 was weak in infected HK cells in comparison to the clearly increased AAV2 genome amplification in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (compare Fig. 2C and D). Additionally, there was no appreciable increase in AAV2 genome amplification in HK cells until day 7 (Fig. 2D), indicating that AAV2 was unable to replicate efficiently in HK cells during this time course. Thus, the failure of AAV2 to productively infect HK cells could lead to the absence of Rep protein expression and the induction of apoptosis in normal cells. To address this possibility, we analyzed the effect of physically delivering the AAV2 genome into HK cells using standard calcium-phosphate-DNA coprecipitation/transfection protocols. For these experiments, we transfected 15 μg of the full-length cloned AAV2 genome into HPV31 and HK cells. In the current study, the same AAV2 clone was used for production of the AAV2 virus stocks. To determine the transfection efficiency, we also cotransfected 15 μg of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression vector (Clontech) as a surrogate marker for delivery of the unlabeled AAV2 genome into both cell types. In our hands, the efficiency of the transfection protocol performed with 15 μg of the GFP expression vector alone routinely resulted in an average of 15% of HPV31 and HK cells being GFP positive (Fig. 3A and B, respectively), which is within the efficiency range reported for keratinocytes in published studies (12, 33). Cotransfection of the GFP expression vector with the AAV2 genome into HPV31 cells resulted in a reduced number of adherent cells, as determined visually, compared with the number of adherent HPV31 cells transfected with GFP alone (Fig. 3A). Additionally, delivery of the AAV2 genome induced cell death in GFP-positive HPV31 cells, as determined from their morphology (Fig. 3A), and could be correlated with the expression of Rep78, Rep52, and Rep40 proteins (Fig. 3C). Under these conditions, the expression of Rep68 could not be clearly resolved. In contrast, HK cells cotransfected with the GFP expression vector and the AAV2 genome expressed numbers of GFP-positive cells that were approximately equal to the numbers of HK cells expressing GFP alone (Fig. 3B). Delivery of the AAV2 genome into HK cells did not induce cell death, as determined by the morphology of adherent GFP-positive cells (Fig. 3B) and failure to express Rep proteins (Fig. 3C). Thus, regardless of implementing infection or transfection as the mode of AAV2 genome delivery into HPV31 and HK cells, identical results were obtained (compare Fig. 2 and 3).

FIG. 3.

Calcium-phosphate transfection of HPV31 and HK cells with the cloned AAV2 genome and the GFP expression vector (Clontech) as transfection control. For each experiment, nontransfected (−GFP) cells are shown in the left panels, GFP-only controls (+GFP) are shown in the middle panels, and GFP vector and AAV2 genome-transfected cells (+GFP/+AAV2) are shown in the right panels. (A) HPV31 cells transfected with the GFP expression vector and AAV2 cloned genome. AAV2-induced cell death was correlated with decreased numbers of cells adhering to plates. The membrane integrity of GFP-positive HPV31 cells in cells cotransfected with AAV2 was disrupted in comparison to the membrane integrity of cells transfected with the GFP vector alone. All images were captured with a 20× objective. (B) HK cells transfected with the GFP expression vector and cloned AAV2 genome. GFP expression is observed equally irrespective of the presence of AAV2, and cell death was not observed, as determined from membrane integrity. All images were captured with a 20× objective. (C) Transfection of AAV2 genome induced cell death, which was correlated with the expression of Rep proteins in HPV31-positive cells but not in transfected HK cells. For detecting Rep proteins in Western blots, total protein extracts were prepared as we have previously described (1). Western blotting was performed using 60 μg of total protein extracts from HPV31 and HK cells transfected with the GFP expression vector and AAV2 genome. As controls, cells were transfected with the GFP vector alone. Protein samples were resolved in a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and detected with an AAV2 Rep-specific antibody (Progen). For clarity of detection of individual Rep proteins, blots were exposed for 10, 20, and 45 s as indicated. Arrows point to individual Rep proteins detected in HPV31 cells transfected with AAV2. Rep52 was detected in lane 3, Rep40 was detected in lane 6, and Rep78 dimer was detected in lane 9. Rep68 expression could not be clearly established. +, present; −, absent.

The observed lack of Rep protein expression in AAV2-infected (Fig. 2B) or -transfected (Fig. 3C) HK cells could be due to the absence of transcription-/translation-related functions necessary for AAV2 gene expression. Others have reported that the HPV16 E2 protein provides functions necessary for productive AAV2 replication in HPV16-positive cells but not in cells lacking HPV16 genomes (32). Additionally, AAV2 was shown to induce a G2-phase-mediated growth arrest and subsequently kill cancer cells with defective p53, but cells expressing normal p53 proteins were shown to maintain this block (35).

During apoptosis, both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways regulate DNA fragmentation (14). Additionally, the DNA fragmentation observed in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells could be a function of Rep78, as studies have reported the ability of Rep78 to induce cellular DNA damage and invoke a damage response (9). Under normal conditions, nicking of cellular chromatin results from the inherent site-specific endonuclease activity of Rep78/Rep68, a function required for AAV replication and integration into the human genome (21). Thus, our results suggest the possibility that Rep proteins could also be involved in mediating signals for the induction of apoptosis via DNA damage in HPV-infected cells.

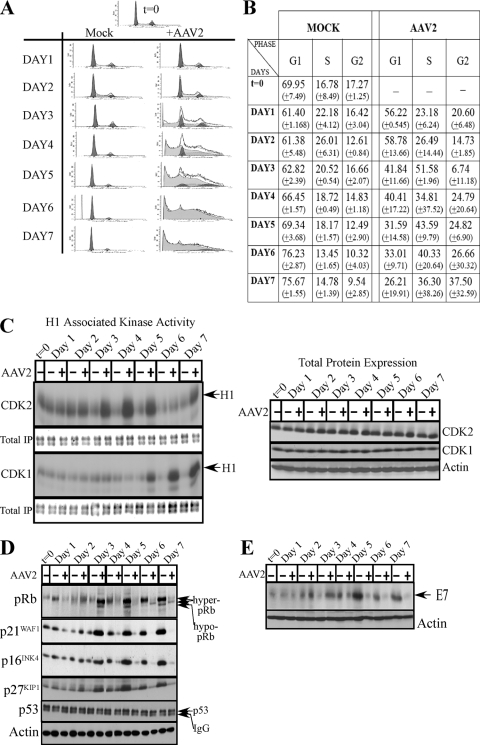

Studies have suggested a connection between apoptosis and cell cycle control (10, 16). To determine whether the induction of apoptosis in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells could be correlated with cell cycle progression, we performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. On day 3 and day 4, HPV/AAV2-coinfected cells increasingly entered into S phase compared with the cell cycle progression of controls (Fig. 4A and B). Increased S-phase entry was correlated with upregulated CDK2-associated kinase activity (Fig. 4C, left panel) and with stabilized pRb protein expression displaying both hyperphosphorylated (inactive) and hypophosphorylated (active) forms of the protein (Fig. 4D). Others have reported the ability of Rep78 to promote pRb hypophosphorylation and a complete S-phase arrest (9, 36), mediated via Rep78 binding to CDC25A and preventing access to its substrates, CDK2 and CDK1 (9, 36). Normally, pRb inactivation and E2F release is required for E2F transcription of S-phase genes (7). However, DNA damage-induced pRb acetylation/inactivation promotes E2F1 transcription of proapoptotic genes (26). In contrast, DNA damage-induced Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of pRb leads to E2F sequestration and transcriptional inhibition of proapoptotic genes (22). In our current study, we demonstrate the ability of AAV2 to catalyze S-phase entry in cycling cells in the presence of pRb in both its active and inactive forms, which could represent a novel trigger for the induction of apoptosis. In HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells, death could occur due to conflicting signals arising from a breach of G1/S checkpoints, followed by S-phase entry and progression (mediated by hyperphosphorylated pRb), simultaneous with the transcription of genes related to differentiation and growth arrest (activated by hypophosphorylated pRb). It is also notable that on day 3, AAV2-triggered S-phase entry occurred in the presence of increased levels of CDK inhibitors p21WAF1, p27KIP1, and p16INK4 (Fig. 4D), conditions which otherwise should be expected to mediate growth arrest in G1. The ability of AAV2 to promote increased S-phase entry could be a mechanism whereby AAV2 competes with HPV for cellular factors for its own transcription. Alternatively, Rep proteins could directly activate proapoptotic pathways independent of pRb/E2F.

FIG. 4.

(A) FACS analysis profiles of HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells. Cells were infected with AAV2 and stained with propidium iodide as previously described (1). Both control and AAV2-infected cells were passaged on day 2. (B) Percentages of HPV31/AAV2-coinfected and mock-infected cells in G1, S, and G2 phases of the cell cycle. Experiments were repeated three times. Results shown represent averages determined from three individual experiments, with standard deviations presented in parentheses. (C) AAV2 infection of HPV31 cells affects S phase and G2 phase kinase activities. (Left) Beginning on day 3 after infection with AAV2, HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells displayed increased CDK2-associated kinase activity compared with that in control cells, which corresponded to increased entry of HPV/AAV2-infected cells into S phase. HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells displayed increased CDK1-associated kinase activity beginning on day 5, indicating increased G2-specific activation. CDK2- and CDK1-associated kinase activities were determined using histone H1 as substrate as described previously (1). To determine equal loading of total protein in immunoprecipitated samples (IP) used in the kinase assays, an identical blot was stained with GelCode blue stain reagent (Pierce). (Right) Western blots were used to determine CDK2 and CDK1 total protein levels. Changes in kinase activities of CDK2 and CDK1 are observed in the absence of changes in their total protein levels. Thirty micrograms of total protein was resolved on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel, followed by detection with rabbit polyclonal antibodies as we have previously described (1). Actin was used as a loading control. (D) At early time points, AAV2 mediated stabilization of pRb expression representing both hyperphosphorylated (inactive) and hypophosphorylated (active) forms; upregulation of p16INK4, p27KIP1, and p21WAF1 correlated with increased S-phase entry and the induction of apoptosis. At later time points, increased G2-phase entry correlated with loss of p21WAF1, p27KIP1, and p16INK4 tumor suppressor protein levels, whereas p53 protein levels were unchanged. Western blot analysis of all proteins was performed as we have previously described (1). IgG, immunoglobulin G. (E) Total E7 oncoprotein levels declined in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells compared with the levels in controls. Western blot analysis was performed using a mouse monoclonal antibody against HPV16 E7 (Santa Cruz), using protocols we have previously described (1). Downregulation of E7 was correlated with increased entry into G2 and diminished total pRb protein expression which appeared to be differentially phosphorylated. Results shown are representative of three individual experiments. Actin was used as a loading control. t, time; +, present; −, absent.

Late in infection, on day 5, an increased percentage of HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells entered into G2 (Fig. 4A and B). In normal cells, intact p53 and p21WAF1 proteins respond to DNA damage signaling by sustaining a G2-phase arrest which is a protective cellular mechanism for allowing DNA repair before proceeding into mitosis, thus inhibiting cell death (39). However, on day 6 and day 7, the steady increase in G2 progression in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (Fig. 4B) correlated with increased CDK1-associated kinase activity (Fig. 4C), which normally mediates entry into mitosis. In contrast, control cells reached confluence and became contact inhibited. Failure to mount an effective G2/M arrest by inhibiting CDK1 kinase activity could be due to the inability of these cells to maintain p21WAF1 CDK inhibitor protein levels, as compared with the levels in control cells (day 4 to day 7) (Fig. 4D). Decreasing p21WAF1 levels regulate the ability of p21WAF1 to block apoptosis (13). Thus, AAV2-mediated downregulation of p21WAF1 levels may act to prime HPV-infected cells for downstream events which culminate in apoptosis. The observed AAV2-mediated downregulation of multiple CDK inhibitors, including p27KIP1 and p16INK4 in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (day 4 to day 7) (Fig. 4D), could be a mechanism necessary to counteract cell cycle checkpoint-induced growth arrest in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells. Additionally, changes in p21WAF1 levels occurred in the absence of changes in total levels of p53 (Fig. 4D), which is a transcriptional activator of p21WAF1 (25).

We also routinely observed aberrant fluctuations in CDK2-associated kinase activities in HPV31 cells infected with AAV2 on day 7 compared with the activities at earlier time points (Fig. 4C, left panel). The large standard deviations observed in the results of FACS analyses of the HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (Fig. 4B) could be correlated with variations in kinase activities in dying cells nearing the end of their life span.

We also determined the effect of AAV2 infection on E7 oncoprotein levels, which were downregulated in HPV31/AAV2-coinfected cells (day 4 to day 7) (Fig. 4E). Loss of E7 protein in coinfected cells correlated with decreased levels of its cellular binding partners pRb and p21WAF1 (30) (Fig. 4D). Also, pRb appeared to be differentially phosphorylated (Fig. 4D).

AAV2 induction of apoptosis was not unique to the HPV31-positive CIN-612 9E cells. In the current study, we also tested CIN-612 6E cells (which maintain only integrated copies of the HPV31b genome) by infecting them with AAV2, and these cells also underwent apoptosis (Table 1). In our hands, we also observed that other cell lines derived from both low- and high-grade HPV-infected tissues, such as RECA and AWCA cell lines (high-risk invasive-carcinoma-derived counterparts of HPV16 and HPV18 cell lines, respectively), and our laboratory-derived cell lines maintaining episomal copies of HPV16 and HPV18 (Table 1) were also susceptible to the induction of apoptosis upon AAV2 infection. Our results show that cells infected with a range of different HPV types and CIN grades are susceptible to AAV2-mediated cell killing.

TABLE 1.

Summary of different HPV-positive cell lines which underwent apoptosis upon infection with AAV2a

| Cell line (HPV type) | HPV genome status | Induces apoptosis |

|---|---|---|

| CIN-612 9E (HPV31b) | Episomal | Yes |

| CIN-612 6E (HPV31b) | Integrated | Yes |

| W12 (HPV16) | Episomal | Yes |

| RECA (HPV16) | Integrated | Yes |

| HPV16(114b):9 | Episomal | Yes |

| HPV18wt:4 | Episomal | Yes |

| AWCA (HPV18) | Integrated | Yes |

| Primary HK cells | None | No |

Cell lines maintaining episomal genomes are representative of low-grade cervical lesions. Cell lines maintaining integrated genomes are representative of high-grade lesions. CIN-612 9E and CIN-612 6E cell lines were both derived from a CIN I lesion. RECA and AWCA are cell lines which were derived from invasive carcinomas (34). HPV16(114b):9 (28) and HPV18wt:4 are both cell lines derived and characterized in our laboratory.

In conclusion, our results suggest a specific interaction between AAV2 and HPV and represent novel data which unmask a previously undocumented capacity of the wild-type AAV2 virus to induce apoptosis in HPV-infected cells but not in normal keratinocytes. HK cells were resistant to the apoptosis-inducing effects of AAV2, likely due to the failure of the AAV2 virus to productively infect normal keratinocytes. These observations are of interest, and further studies are required to determine the nature of this block in normal keratinocytes. For the purposes of the current study, whether AAV2 fails to productively infect normal cells or whether a cellular block in normal cells prevents the expression of AAV2 Rep proteins is a secondary consideration but one which could prove extremely advantageous in the design of AAV2-derived therapeutics for HPV-associated cancers. Our studies portray AAV2 as a potential anticancer agent which targets HPV-infected cells but leaves normal cells intact and which could be exploited to clinical advantage. In the future, the identification of antiproliferative/proapoptotic AAV2-derived proteins and the cell growth/apoptosis pathways activated by AAV2-derived products could be used to design targeted therapeutics for multiple HPV-related cancers.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Bowser for critical reading of the manuscript and advice with the transfection experiments. We also thank Mi Sun Moon for help with the microscopy work.

This work was supported by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Breast and Cervical Cancer Initiative to C.M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam, S., E. Sen, H. Brashear, and C. Meyers. 2006. Adeno-associated virus type 2 increases proteosome-dependent degradation of p21WAF1 in a human papillomavirus type 31b-positive cervical carcinoma line. J. Virol. 80:4927-4939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bantel-Schaal, U. 1995. Growth properties of a human melanoma cell line are altered by adeno-associated parvovirus type 2. Int. J. Cancer 60:269-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bantel-Schaal, U., and M. Stohr. 1992. Influence of adeno-associated virus on adherence and growth properties of normal cells. J. Virol. 66:773-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batchu, R. B., M. A. Shammas, J. Y. Wang, J. Freeman, N. Rosen, and N. C. Munshi. 2002. Adeno-associated virus protects the retinoblastoma family of proteins from adenoviral-induced functional inactivation. Cancer Res. 62:2982-2985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batchu, R. B., M. A. Shammas, J. Y. Wang, and N. C. Munshi. 2001. Dual level inhibition of E2F-1 activity by adeno-associated virus Rep78. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24315-24322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedell, M. A., J. B. Hudson, T. R. Golub, M. E. Turyk, M. Hosken, G. D. Wilbanks, and L. A. Laimins. 1991. Amplification of human papillomavirus genomes in vitro is dependent on epithelial differentiation. J. Virol. 65:2254-2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell, L. A., and K. M. Ryan. 2004. Life and death decisions by E2F-1. Cell Death Differ. 11:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berns, K. I., and C. Giraud. 1996. Biology of adeno-associated virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 218:1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthet, C., K. Raj, P. Saudan, and P. Beard. 2005. How adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein arrests cells completely in S phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:13634-13639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brady, H. J., and G. Gil-Gomez. 1999. The cell cycle and apoptosis. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 23:127-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casto, B. C., J. A. Armstrong, R. W. Atchison, and W. M. Hammon. 1967. Studies on the relationship between adeno-associated virus type 1 (AAV-1) and adenoviruses. II. Inhibition of adenovirus plaques by AAV; its nature and specificity. Virology 33:452-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chenuet, S., D. Martinet, N. Besuchet-Schmutz, M. Wicht, N. Jaccard, A. C. Bon, M. Derouazi, D. L. Hacker, J. S. Beckmann, and F. M. Wurm. 2008. Calcium phosphate transfection generates mammalian recombinant cell lines with higher specific productivity than polyfection. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 101:937-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Detjen, K. M., D. Murphy, M. Welzel, K. Farwig, B. Wiedenmann, and S. Rosewicz. 2003. Downregulation of p21(waf/cip-1) mediates apoptosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells in response to interferon-gamma. Exp. Cell Res. 282:78-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmore, S. 2007. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 35:495-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georg-Fries, B., S. Biederlack, J. Wolf, and H. zur Hausen. 1984. Analysis of proteins, helper dependence, and seroepidemiology of a new human parvovirus. Virology 134:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil-Gomez, G., A. Berns, and H. J. Brady. 1998. A link between cell cycle and cell death: Bax and Bcl-2 modulate Cdk2 activation during thymocyte apoptosis. EMBO J. 17:7209-7218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han, L., T. H. Parmley, S. Keith, K. J. Kozlowski, L. J. Smith, and P. L. Hermonat. 1996. High prevalence of adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 rep DNA in cervical materials: AAV may be sexually transmitted. Virus Genes 12:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermanns, J., A. Schulze, P. Jansen-Dürr, J. A. Kleinschmidt, R. Schmidt, and H. zur Hausen. 1997. Infection of primary cells by adeno-associated virus type 2 results in a modulation of cell cycle-regulating proteins. J. Virol. 71:6020-6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermonat, P. L. 1994. Adeno-associated virus inhibits human papillomavirus type 16: a viral interaction implicated in cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 54:2278-2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horer, M., S. Weger, K. Butz, F. Hoppe-Seyler, C. Geisen, and J. A. Kleinschmidt. 1995. Mutational analysis of adeno-associated virus Rep. protein-mediated inhibition of heterologous and homologous promoters. J. Virol. 69:5485-5496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Im, D. S., and N. Muzyczka. 1990. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell 61:447-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue, Y., M. Kitagawa, and Y. Taya. 2007. Phosphorylation of pRB at Ser612 by Chk1/2 leads to a complex between pRB and E2F-1 after DNA damage. EMBO J. 26:2083-2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kube, D. M., S. Ponnazhagan, and A. Srivastava. 1997. Encapsidation of adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep proteins in wild-type and recombinant progeny virions: Rep-mediated growth inhibition of primary human cells. J. Virol. 71:7361-7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonard, C. J., and K. I. Berns. 1994. Cloning, expression, and partial purification of Rep78: an adeno-associated virus replication protein. Virology 200:566-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, Y., C. W. Jenkins, M. A. Nichols, and Y. Xiong. 1994. Cell cycle expression and p53 regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Oncogene 9:2261-2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markham, D., S. Munro, J. Soloway, D. P. O'Connor, and N. B. La Thangue. 2006. DNA-damage-responsive acetylation of pRb regulates binding to E2F-1. EMBO Rep. 7:192-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayor, H. D., S. Drake, J. Stahmann, and D. M. Mumford. 1976. Antibodies to adeno-associated satellite virus and herpes simplex in sera from cancer patients and normal adults. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 126:100-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLaughlin-Drubin, M. E., N. D. Christensen, and C. Meyers. 2004. Propagation, infection, and neutralization of authentic HPV16 virus. Virology 322:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers, C., S. Alam, M. Mane, and P. L. Hermonat. 2001. Altered biology of adeno-associated virus type 2 and human papillomavirus during dual infection of natural host tissue. Virology 287:30-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munger, K., M. Scheffner, J. M. Huibregtse, and P. M. Howley. 1992. Interactions of HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins with tumour suppressor gene products. Cancer Surv. 12:197-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nash, K., W. Chen, M. Salganik, and N. Muzyczka. 2009. Identification of cellular proteins that interact with the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J. Virol. 83:454-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogston, P., K. Raj, and P. Beard. 2000. Productive replication of adeno-associated virus can occur in human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) episome-containing keratinocytes and is augmented by the HPV-16 E2 protein. J. Virol. 74:3494-3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pham, P. L., A. Kamen, and Y. Durocher. 2006. Large-scale transfection of mammalian cells for the fast production of recombinant protein. Mol. Biotechnol. 34:225-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rader, J. S., T. R. Golub, J. B. Hudson, D. Patel, M. A. Bedell, and L. A. Laimins. 1990. In vitro differentiation of epithelial cells from cervical neoplasias resembles in vivo lesions. Oncogene 5:571-576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raj, K., P. Ogston, and P. Beard. 2001. Virus-mediated killing of cells that lack p53 activity. Nature 412:914-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saudan, P., J. Vlach, and P. Beard. 2000. Inhibition of S-phase progression by adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein is mediated by hypophosphorylated pRb. EMBO J. 19:4351-4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlehofer, J. R. 1994. The tumor suppressive properties of adeno-associated viruses. Mutat. Res. 305:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt, M., S. Afione, and R. M. Kotin. 2000. Adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep78 induces apoptosis through caspase activation independently of p53. J. Virol. 74:9441-9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suganuma, M., T. Kawabe, H. Hori, T. Funabiki, and T. Okamoto. 1999. Sensitization of cancer cells to DNA damage-induced cell death by specific cell cycle G2 checkpoint abrogation. Cancer Res. 59:5887-5891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timpe, J. M., K. C. Verrill, B. N. Black, H. F. Ding, and J. P. Trempe. 2007. Adeno-associated virus induces apoptosis during coinfection with adenovirus. Virology 358:391-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walz, C., A. Deprez, T. Dupressoir, M. Durst, M. Rabreau, and J. R. Schlehofer. 1997. Interaction of human papillomavirus type 16 and adeno-associated virus type 2 co-infecting human cervical epithelium. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1441-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winocour, E., M. F. Callaham, and E. Huberman. 1988. Perturbation of the cell cycle by adeno-associated virus. Virology 167:393-399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]