Abstract

Background

Patients with Type 2 diabetes are at increased risk for the development of atherosclerosis. A pivotal event in the development of atherosclerosis is macrophage foam cell formation. The ABC transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 regulate macrophage cholesterol efflux, and hence play a vital role in macrophage foam cell formation. We have previously found that chronic elevated glucose reduces ABCG1 expression. In the current study, we examined whether patients with Type 2 diabetes had decreased ABCG1 and/or ABCA1, impaired cholesterol efflux, and increased macrophage foam cell formation.

Methods and Results

Blood was collected from patients with and without Type 2 diabetes. Peripheral blood monocytes were differentiated into macrophages and cholesterol efflux assays, immunoblots, histological analysis, and intracellular cholesteryl ester measurements were performed. Macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes had a 30% reduction in cholesterol efflux with a corresponding 70% increase in cholesterol accumulation relative to controls. ABCG1 was present in macrophages from control subjects, but was undetectable in macrophages from patients with Type 2 Diabetes. In contrast, ABCA1 expression in macrophages was similar in both control subjects and in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Macrophage expression of ABCG1 in both patients and controls was induced by treatment with the LXR agonist TO-901317. Upregulation of LXR dramatically reduced foam cell formation in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes.

Conclusions

ABCG1 expression and cholesterol efflux are reduced in patients with Type 2 diabetes. This impaired ABCG1-mediated cholesterol efflux significantly correlates with increased intracellular cholesterol accumulation. Strategies to upregulate ABCG1 expression and function in Type 2 diabetes could have therapeutic potential for limiting the accelerated vascular disease observed in patients with Type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: ABCA1, ABCG1, cholesteryl ester, LXR, macrophages, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is accelerated several-fold in patients with Type 2 diabetes 1-4. A critical event in the development of atherosclerosis occurs when monocytes transmigrate into the subendothelial space and differentiate into macrophages 5. Upon differentiation, macrophages upregulate expression of scavenger receptors (SR-A, LOX-1 and CD36), which have the ability to take up modified lipoproteins 6;7. Likewise, members of the ATP binding cassette transporter family (ABC transporters), including ABCA1 and ABCG1, are also upregulated during macrophage differentiation, and have been shown to regulate cellular lipid metabolism 8-10. Of particular importance in atherosclerosis is the balance between the influx and efflux of modified low density lipoproteins (LDLs), because when the net influx of cholesterol supersedes that of efflux, the macrophages become lipid-laden foam cells 11.

Much is known about the role of ABCA1, as mutations in the ABCA1 gene cause Tangier Disease, a condition characterized by severely reduced HDL levels 12. ABCG1 is ubiquitously expressed and is highly expressed in lipid-loaded macrophages 13. Both proteins are known regulators of macrophage cholesterol homeostasis and key players in reverse cholesterol transport 9;10;13;14;14.

While much is known about the roles that ABCA1 and ABCG1 play in macrophage foam cell formation and the development of atherosclerosis, little is known about how cholesterol metabolism is altered in the setting of Type 2 diabetes. Previous work in our laboratory has shown that macrophage ABCG1 expression and function is decreased in mouse models of Type 2 diabetes 15. We found that the elevated glucose environment was partially responsible for this reduction in ABCG1 in diabetic macrophages. Here we examine the effects of Type 2 diabetes on the function of human monocyte-derived macrophages in reverse cholesterol transport. We show for the first time that ABCG1 expression is decreased in macrophages isolated from patients with Type 2 diabetes, leading to decreased cholesterol efflux to HDL, and resulting in increased macrophage cholesteryl ester content.

Methods

Reagents

RosetteSep Human Monocyte Enrichment Cocktail was ordered from StemCell Technologies, Inc.. Ficoll-Paque™ PREMIUM was purchased from GE Healthcare. DMEM and Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution came from Gibco. Human MCSF came from PeptroTech, Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ). FBS was purchased from Hyclone (Logan, UT). Human HDL was ordered through Intracel (Frederick, MD). [1,2-3H(N)]-Cholesterol came from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA). NuPAGE 4−12% denaturing gels came from Invitrogen. Anti-ABCG1 antibody came from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Anti-ABCA1 antibody was a kind gift of John Parks (Wake Forest University). In addition, horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies were ordered from Amersham Biosciences UK Ltd. (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). TO-901317 was purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Whole human HDL was purchased from Intracel (Frederick, MD), while apoA-I was isolated as described previously described 15.

Human Monocyte Isolation and Macrophage Differentiation

Willing human subjects volunteered their blood in agreement with the University of Virginia's Institutional Review Board for Health Science Research Protocol # 12454. Both male and non-pregnant females aged 18 and older participated. All participants were patients of the University of Virginia Cardiovascular Prevention Clinic and were undergoing aggressive risk factor modification. Up to 100 mls of additional blood was collected from the patients at the time of phlebotomy for routine, clinically indicated laboratory work. The only patient identifier at the time of collection was whether or not the patient had Type 2 diabetes, their age and gender. Ten mls from each patient was drawn into blood collection tubes to collect autologous serum for tissue culture. The remaining blood was drawn into heparinized blood collection tubes. Human monocytes were isolated using Rosette-Sep Human Monocyte Enrichment Cocktail following the manufacturer's protocol. Monocytes were then plated in tissue culture using Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Media (DMEM) containing 1.5 g/L glucose, 10 ng/ml of human M-CSF, 10% autologous serum and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic mixture. Autologous serum was used in an effort to maintain the in vivo milieu as best as possible. Although diluted, the use of autologous serum maintains the relative composition of blood components that the cells are exposed to in vivo, except for glucose, which was supplemented. Monocytes were allowed to differentiate for three days before being used in experiments. Glucose values were monitored in media throughout the 3-day culture and did not vary more than 5% for each sample (data not shown). In some experiments, macrophages were incubated for 24h in the presence of 3μM of the well-characterized LXR agonist, TO-901317 before analysis. The monocyte recovery from 100 mls of blood was not sufficient to conduct every experiment on each blood sample. Thus, while Table 1 shows the laboratory profile of the entire study population, results in Figures 1, 2 and 4 represent random subsets of the total study population.

Table 1. Laboratory profile of study population.

Average fasting plasma total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL, LDL, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, insulin and HOMA calculations.

| Population | T Chol | Trig | HDL | LDL | Glucose | HbA1c | Insulin | HOMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n=31) | 175 ± 6 | 137 ± 8 | 49 ± 2 | 99 ± 5 | 83 ± 2 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 31 ± 2 | 191 ± 27 |

| T2D (n=24) | 172 ± 10 | 194 ± 13* | 39 ± 2* | 97 ± 9 | 127 ± 9* | 7.9 ± 1* | 56 ± 9* | 499 ±107* |

| Ideals | [<200] | [55−150] |

>40 ♂ >50 ♀ |

[<130] | [74−100] | <6% | N/A | N/A |

Values are given ± the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Significantly different than control patients, p<0.01 for each parameter. T Chol = total plasma cholesterol; Trig = total plasma triglycerides, HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

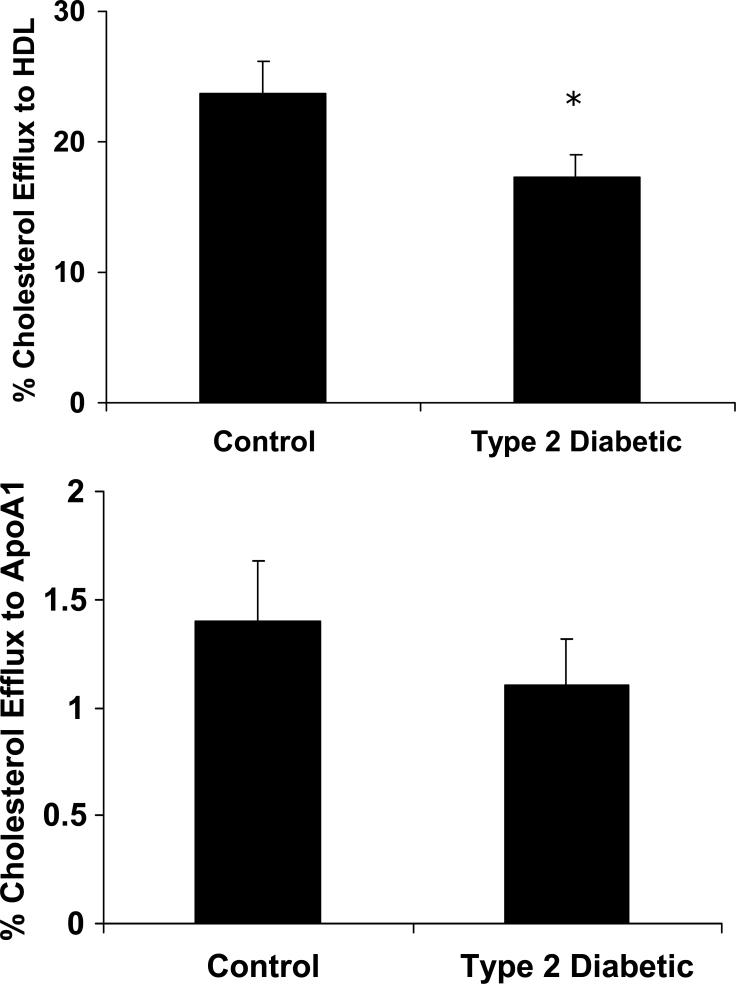

Figure 1. Cholesterol efflux to HDL is reduced from macrophages of Type 2 diabetic patients.

Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from control subjects (n=14) and patients with Type 2 diabetes (n=11) and differentiated into macrophages using M-CSF for 3 days. Macrophages were then incubated in 2 μCi/ml of 3H-cholesterol overnight and cholesterol efflux to HDL and lipid-poor ApoAI was measured for 4 hours. Top Panel: Cholesterol efflux to HDL. Cholesterol efflux to HDL is reduced by 27% in macrophages from Type 2 diabetic patients, *p<0.01 for Diabetic vs. Control. Bottom Panel: Cholesterol efflux to lipid-poor ApoAI. No significant differences were observed in cholesterol efflux to ApoAI.

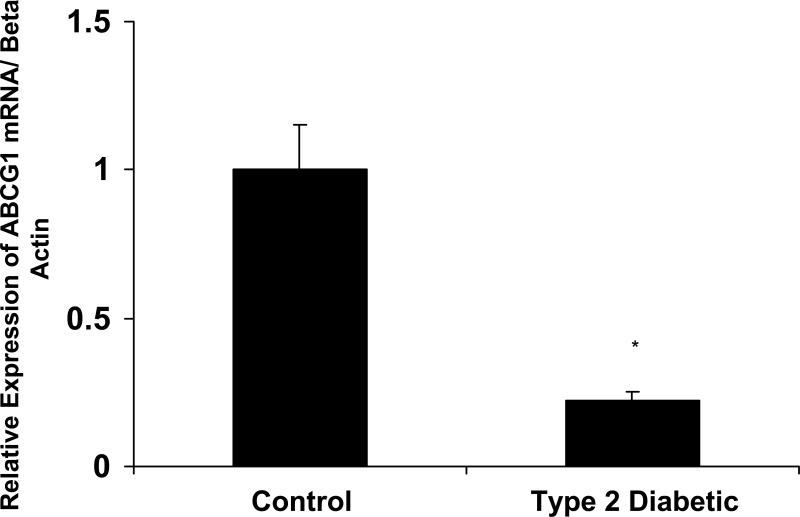

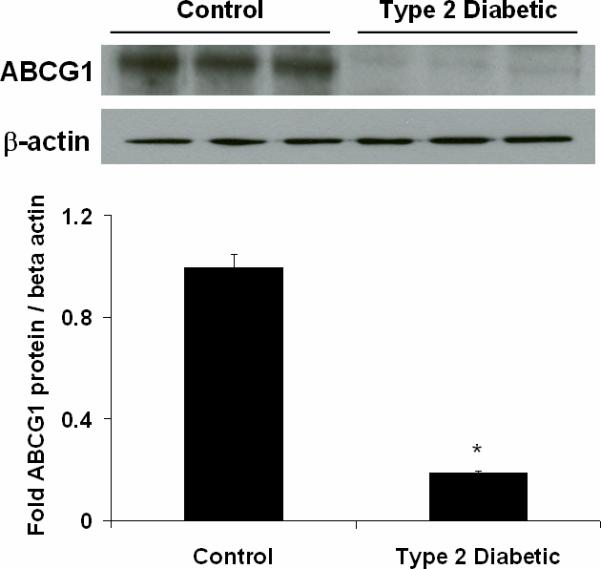

Figure 2. Macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes have decreased ABCG1 protein expression.

Representative immunoblot of ABCG1 protein expression in macrophages from isolated from control subjects (n=3) and patients with Type 2 diabetes (n=3). Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from control subjects and patients and differentiated into macrophages using M-CSF for 3 days. Panel A: ABCG1 protein expression. Whole cell macrophage lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for ABCG1. β-actin is shown as a control for loading. Densitometry from 3 representative blots is shown. ABCG1 protein is significantly reduced in macrophages from Type 2 diabetic patients, *p<0.001 vs. Control. Panel B. ABCG1 mRNA expression. ABCG1 and β-actin mRNA was measured in macrophages from control subjects (n=8) and patients with type 2 diabetes (n=8) using real-time PCR and primers from Ambion. ABCG1 mRNA was significantly reduced in macrophages from patients with type 2 diabetes, *p<0.001 vs. Control.

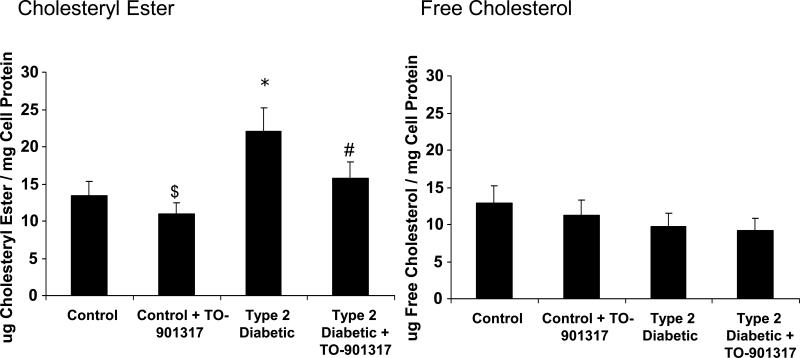

Figure 4. Increased lipid accumulation in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes.

Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from control subjects and patients and differentiated into macrophages using M-CSF for 3 days. Macrophages were stimulated with the LXR agonist TO-901317 for the final 24hrs of incubation to upregulate ABCG1 and ABCA1. Gas chromatography was then performed to quantify intracellular free cholesterol and cholesteryl ester. Left panel: Macrophage Cholesteryl Ester content. Cholesteryl ester concentrations were significantly increased in the Type 2 diabetic samples, *p=0.02 versus control. Incubation of macrophages with TO-901317 reduced the cholesteryl ester content of macrophages, $p<0.05 versus control, #p<0.01 versus Type 2 diabetic. Right Panel: Macrophage Free Cholesterol Content. No significant differences in free cholesterol were observed between the samples. N=9 for Control. N=9 for Control + TO-901317. N=4 for Type 2 diabetic. N=4 for Type 2 diabetic + TO-901317.

Immunoblots

RIPA buffer was added to macrophages to generate whole cell lysates. The lysates were collected, briefly sonicated, and quantified using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, then transferred to nitrocellulose and blocked for 2 hours with Blocker-BLOTTO (Pierce). Thirty μg of whole cell lysate was used for detection of all proteins. Blots were incubated in Tris-buffered saline + 1% Tween 20 (TBST) containing a 1:500 dilution of antibody overnight at 4°C. Blots were then incubated with a 1:5000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized using chemiluminescence and normalized to beta-actin as a control for gel loading.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total cellular RNA was collected from macrophages using Trizol Reagent following the manufacturer's protocol. 1μg of cDNA was then synthesized using an Iscript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Total cDNA was diluted 1:8 in H2O and 4μl were used for each real-time condition using a Bio-Rad MyIQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System and iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers for human ABCG1 and beta-actin were ordered from Ambion. Samples were normalized to beta-actin using the ΔCt (cycle threshold) method.

Isotopic Cholesterol Efflux Assays

After three days of differentiation on 24-well plates, cells were washed thoroughly and radiolabeled with 2 μCi/ml of [3H] cholesterol overnight in the presence of 10% FBS. The following day, cells were washed with PBS and equilibrated for 2 hours in the presence of serum free medium containing 0.2% fatty acid free bovine serum albumin (BSA). Cholesterol efflux was conducted for 4 h at 37°C in medium containing either 0.2% BSA, 0.2% BSA + 50 μg of protein/ml of human HDL or 0.2% BSA + 15 μg of protein/ml of human lipid-poor ApoAI. HDL used in these studies was identical for each group, and was from the same commercial source so as to effectively remove any differences in HDL populations that may occur with the use of autologous HDL isolated from control subjects and patients with type 2 diabetes. The efflux medium was then removed (0.5 ml total) and a 100 μl aliquot was taken for 3H radioactivity determination in a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter. Adherent cells were rinsed twice with cold PBS and 0.5 ml of isopropyl alcohol was added for overnight extraction of remaining cholesterol at room temperature. The isopropyl alcohol was then removed and dried under nitrogen, then resuspended in another 0.5 ml of isopropyl alcohol. A 100 μl aliquot of the extract was taken for 3H radioactivity determination. Results are expressed as percent efflux calculated by dpm of [3H] cholesterol in medium \ ([3H] cholesterol in medium + [3H] cholesterol remaining in cells) × 100. Specific efflux to HDL or ApoAI was calculated by subtracting nonspecific efflux in the presence of 0.2% BSA only. While the possibility of back exchange of radiolabeled cholesterol exists, it is presumably minimized during the standard 4 hour experiments commonly used 16;17.

Plasma Analysis

Plasma lipid levels, glucose and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were determined by the University of Virginia Clinical Pathology Laboratory. Insulin was measured by the University of Virginia Metabolic Core using a radioimmunoassay kit (Linco, St. Charles, MO).

HOMA calculations

Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA) calculations were made to illustrate the degree of insulin resistance between the study groups. The following formula was used: (fasting insulin (μU/ml) × fasting glucose (mM)) / 22.5. Histology. Cells were allowed to differentiate for three days on chamber slides. The LXR agonist TO-901317 was added during the final 24hrs of incubation to upregulate ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein expression. On day three, macrophages were stained with Oil Red O and hemotoxylin to visualize lipid accumulation. Images were acquired using the 20 or 40x objective on a microscope (model BX51; Olympus) equipped with a digital camera (model DP70; Olympus) using the ImagePro Plus software program in the Academic Computing Health Sciences Center at the University of Virginia.

Cholesteryl Ester Determinations

Monocytes were allowed to differentiate for three days on 100mm dishes. The LXR agonist TO-901317 was added during the final 24hrs to stimulate ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression. Cells were then washed with PBS three times and 5 ml of isopropyl alcohol was added to extract cholesterol overnight at room temperature. 5α-cholestane (Sigma) was then added as an internal standard before drying the samples under nitrogen and resuspending in 200 μl of hexane. Total and free cholesterol content was determined by gas-liquid chromatography and normalized to cellular protein as described previously 15. Esterified cholesterol was calculated as the difference between total and free cholesterol × 1.67.

Statistical Analyses

Data for all experiments were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the Statview 6.0 software program. Comparisons between groups were performed using ANOVA methods. Data are graphically represented as mean ± S.E., in which each mean consists of experiments performed in triplicate. Comparisons between groups and tests of interactions were made assuming a two-factor analysis with the interaction term testing each main effect with the residual error testing the interaction. All comparisons were made using Fisher's least standard difference procedure, so that multiple comparisons were made at the 0.05 level only if the overall F-test from the ANOVA was significant at p < 0.05.

Statement of Responsibility

The authors had full access to and take responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

Study Population

Table 1 shows the fasting laboratory profile of the study population. The control population is within normal parameters for each category. The patients with Type 2 diabetes have laboratory profiles typical of the metabolic syndrome and Type 2 diabetes, with high levels of triglycerides, low HDL-C, elevated glucose and hemoglobin-A1c (HbA1c) values, and elevated insulin and HOMA. The study population included 15 male and 16 female control subjects without Type 2 diabetes with an average age of 56.8 yrs; and 15 male and 9 female patients with Type 2 diabetes with an average age of 63.5yrs. Because the current study was initiated as a pilot with expedited institutional review board approval, we are not able to correlate any experimental data with that of patient identifiers. Therefore, data is not adjusted for race, height, weight, medications, or other information. However, because all patients did come from the University of Virginia Cardiovascular Prevention Clinic, uniform guidelines for risk factor modification were applied.

Cholesterol efflux to HDL is reduced in macrophages of patients with Type 2 diabetes

To investigate whether there was a defect in macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in macrophages isolated from patients with Type 2 diabetes, we performed cholesterol efflux studies. Cholesterol efflux to HDL was decreased in macrophages from Type 2 diabetic subjects by 30% compared to controls (Figure 1). However, cholesterol efflux to lipid-poor ApoAI was unchanged during the four hour time course. Previous studies by Tall et. al. have shown that ABCA1 has the ability to efflux cholesterol to both ApoAI and HDL; However, ABCG1 can efflux cholesterol to more mature HDL moieties 17. Therefore, because cholesterol efflux to ApoAI was unchanged, these data suggest that the decrease in cholesterol efflux observed here is largely due to changes in ABCG1 and not ABCA1.

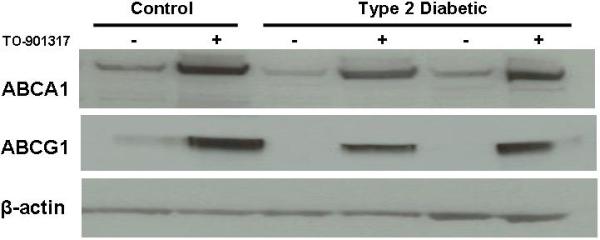

Macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes have decreased protein expression of ABCG1

Because we observed reductions in cholesterol efflux by macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes, we measured protein levels of both ABCA1 and ABCG1. ABCG1 protein expression was significantly reduced in these diabetic macrophages (Figure 2A). ABCG1 mRNA levels were decreased by 80% in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes (Figure 2B). Measurements of CD36 and ABCA1 mRNA revealed no changes between the study groups (data not shown). ABCA1 protein expression was not altered in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes (see “-“ lanes for ABCA1 in Figure 3A). ABCG1 and ABCA1 are known to be regulated by the nuclear receptor LXR 18;19. We incubated macrophages with an LXR agonist to determine if macrophages from Type 2 diabetic patients were responsive to LXR agonism. We found that both ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein levels were upregulated in the presence of the LXR agonist TO-901317 (see “+” lanes in Figure 3A). These findings are similar to what we have recently reported for Type 2 diabetic mouse models15.

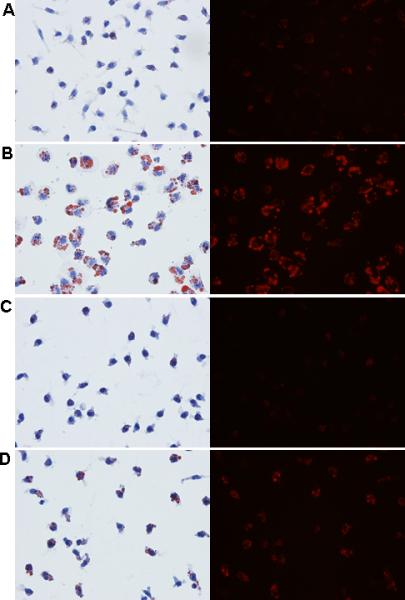

Figure 3. Increased lipid accumulation in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes is dramatically reduced by the LXR agonist TO-901317.

Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from control subjects (n=9) and patients with Type 2 diabetes (n=5) and differentiated into macrophages using M-CSF for 3 days. Macrophages were stimulated with the LXR agonist TO-901317 (3μM) for the final 24hrs of incubation to upregulate ABCG1 and ABCA1. Panel A: ABCG1 and ABCA1 expression. Whole cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for ABCG1 and ABCA1. β-actin is shown as a control for loading. Panel B: Lipid staining. Macrophages were stained with Oil Red O to visualize lipid accumulation. Right panels are fluorescent images of the Oil Red O. A. Macrophages from control subjects. B. Macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes. C. Macrophages from control subjects + 3μM LXR agonist. D. Macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes + 3μM LXR agonist.

Increased lipid accumulation in Type 2 diabetic macrophages is dramatically reduced by the LXR agonist TO-901317

We next measured intracellular lipid accumulation in macrophages from isolated from control subjects and patients with Type 2 diabetes. We stained neutral lipid in macrophages using Oil Red O and found dramatic differences in lipid accumulation between the diabetic and control macrophages (Figure 3B, Panels A and B). Accumulation of neutral lipid was dramatically reduced in both macrophage groups by the LXR agonist TO-901317 (Figure 3B, Panels C and D). To accurately quantify intracellular cholesterol accumulation, we performed gas-liquid chromatography. As shown in Figure 4, cholesteryl esters are increased by approximately 70% in Type 2 diabetic macrophages compared to controls. In addition, intracellular cholesteryl ester concentrations are reduced by approximately 25% in Type 2 diabetic macrophages by the addition of the LXR agonist TO-901317. There was a small, yet significant reduction in cholesteryl ester content by the addition of TO-901317 in macrophages from control subjects (Figure 4). No significant changes in free cholesterol content were observed (Figure 4). Taken together, our findings indicate that reductions in ABCG1 expression in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes significantly and negatively impact cholesterol efflux, resulting in the formation of lipid-laden macrophages. Further, we demonstrate that upregulation of ABCG1 expression through the use of a LXR agonist significantly reduces lipid accumulation in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes.

Discussion

Type 2 diabetes significantly increases the risk for the development of atherosclerosis 1-4. Previous work in our laboratory found that macrophage ABCG1 protein expression was reduced in mouse models of Type 2 diabetes, leading to decreased cholesterol efflux to HDL, and increased intracellular cholesteryl ester accumulation 15. Here, we show for the first time that human monocyte-derived macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes have significantly reduced cholesterol efflux to HDL, leading to an increase in macrophage intracellular cholesterol accumulation. Furthermore, we show that this reduction in cholesterol efflux to HDL is primarily due to decreased ABCG1 expression. Moreover, treatment of diabetic macrophages with the LXR agonist TO-901317 significantly upregulates ABCG1 and ABCA1 expression and reduces intracellular cholesterol accumulation in macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes.

There are three primary scavenger receptors expressed on macrophages: SR-A, LOX-1 and CD36. These macrophage receptors internalize oxidized lipids and are considered proatherogenic 6;7;20;21. Recent studies have shown that elevated glucose increased both SR-A and LOX-1 expression in macrophages. Fukuhara-Takaki et. al. showed increases in both mRNA and protein expression of SR-A in human monocyte derived macrophages incubated in high glucose and in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice22. In addition, Li et. al. have shown that LOX-1 mRNA and protein levels are increased in human monocytes following incubation in high glucose 23;24. Increased expression of CD36 in human monocyte derived macrophages has also been demonstrated in a high glucose environment by Griffin et. al., which they determined was due to an increase in CD36 translation, not transcription 25. Our mRNA measurements of CD36 (data not shown) are in line with these findings.

In addition to the scavenger receptors that regulate the influx of cholesterol to macrophages, there are several equally important ABC transporters involved in the efflux of cholesterol from cells: ABCA1, ABCG1 and ABCG4. Oram et. al. have shown that these ABC transporters act sequentially to eliminate excess cholesterol from the cell, with ABCA1 acting first by effluxing cholesterol to lipid poor ApoAI 14. ABCG1 can then efflux cholesterol to these newly made HDL moieties before ABCG4 can add additional cholesterol. However, macrophages do not express ABCG4, leaving ABCA1 and ABCG1 as the known primary regulators of cholesterol efflux in macrophages. The scavenger receptor SR-B1 can also efflux cholesterol from cells, although recent elegant work by Dan Rader's laboratory indicates that SR-B1 is not a major protein involved in reverse cholesterol transport in vivo26. Based on our findings in the current study using human macrophages, as well as our prior studies using mouse macrophages15, we anticipate that ABCG1 is the primary protein in macrophages affected by the setting of diabetes that regulates cholesterol efflux to HDL. However, we cannot rule out a small contribution of SR-B1 to this process.

Since the LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol values between the control subjects and patients with Type 2 diabetes are nearly identical (see Table 1), we conclude that the large increase in intracellular lipid content in macrophages isolated from patients with Type 2 diabetes (see Figure 3B, Panel B) is not likely due to differences in plasma LDL concentrations between the two study groups. However, there are indeed lower HDL concentrations in serum of the type 2 diabetic patients (Table 1), and it is unclear if the autologous diabetic serum used in the experiments in Figures 3B and 4 contained lower levels of pre-βHDL that could act as an acceptor for the ABCA1 pathway. Changes in pre-β HDL concentrations could certainly influence ABCA1-mediated efflux27-29. In vivo, changes in HDL concentration or HDL composition could impact both ABC transporter-mediated and SR-B1-mediated cholesterol efflux, and possibly even influence passive diffusion of cholesterol from cells. Therefore, it is possible that differences in total HDL concentrations or pre-βHDL concentrations in the patient serum may have impacted the lipid accumulation that we observed in the macrophages (see Figures 3B and 4). Nevertheless, our measurements of cholesterol efflux (Figure 1) indicate that macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes indeed have significant reductions in ABCG1-specific cholesterol efflux.

The role of ABCG1 in atherosclerotic development remains unresolved. Several studies with conflicting results have been published using bone marrow transplantation in mice to study the role of macrophage ABCG1 in atherosclerosis. The most plausible hypothesis based upon the known functions of ABCG1 would be that deficiency of ABCG1 would cause increased atherosclerosis development. However, two recent studies surprisingly found a decrease in atherosclerosis formation in mice receiving ABCG1-deficient bone marrow 30;31, while one study observed a very slight increase in atherosclerosis 32. In addition, work by Basso et. al. found that overexpression of ABCG1 in LDL receptor-deficient mice fed a Western diet had increased atherosclerotic plaque formation 33. Clearly more research on the definitive role of ABCG1 in atherogenesis is warranted. However, our studies in Type 2 diabetic mice 15 and in this current study in humans, suggest that the increased intracellular cholesterol accumulation in macrophages, and subsequent foam cell formation associated with decreased ABCG1 expression could have important physiological consequences with respect to the acceleration of atherosclerosis in patients with Type 2 diabetes.

Pharmacologically, it is well known that synthetic LXR agonists or their endogenous ligands, oxysterols, can upregulate the expression and function of ABCA1 and ABCG1, as LXR appears to be the main transcription factor regulating these proteins 16;19;34;35. Unfortunately, the synthetic agonists available are pan-LXR agonists and cannot differentiate between the LXRα and LXRβ isoforms. Pan-LXR agonists may not be useful as therapies because LXRα is highly expressed in the liver and its activation greatly increases liver and plasma triglyceride concentrations through the activation of SREBP-1 36. Potentially, an LXRβ-specific agonist could be used as a beneficial therapy because LXRβ is not highly expressed in hepatocytes and thus, its activation does not increase plasma triglyceride concentrations 37;38. Therefore, an LXRβ agonist could be used to upregulate ABCA1 and ABCG1 and encourage reverse cholesterol transport, possibly inhibiting or even reversing atherosclerosis. Studies using LXRα and LXRβ knock-out mice support these hypotheses 37;38, yet isoform-specific LXR agonists remain elusive to date.

Of additional interest is the fact that the monocyte-derived macrophages from patients with Type 2 diabetes retained a reduction of ABCG1 protein levels despite being differentiated in culture for three days. One plausible explanation for this is due to the diabetic environment (the glycemic “memory” effect), in which cells removed from the diabetic milieu retain their diabetic phenotype39-41. An alternative explanation is due to a genetic effect, in which ABCG1 variants (SNPs) are associated with diabetes risk (data not shown). In this case, the ABCG1 SNP found in patients with diabetes may affect basal expression of ABCG1 in macrophages. Determination of the functional characteristics of the ABCG1 genetic effect in macrophages requires further study.

As this is a pilot study based on expedited institutional review board oversight, this study has limitations. Without access to patient identification information, we are not able to correlate the observed data to age, sex, medications, and medical history. However, because all participants were patients of the University of Virginia Cardiovascular Prevention Clinic, uniform guidelines for risk factor modification were applied. Thus variations in treatments and therapeutic goals (i.e., total and LDL cholesterol- see Table 1) were minimized. Despite this limitation, this pilot study is the first to implicate the reduction of ABCG1 with associated cholesterol ester accumulation as a potential mechanism for accelerated vascular disease in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Follow-up studies to confirm these findings in a carefully phenotyped population are needed. Nevertheless, therapies to upregulate ABCG1 in Type 2 diabetes most likely will be important for prevention of atherosclerosis and diabetic vascular complications.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr John S. Parks (Wake Forest University) for the gift of recombinant human apoA-I, and Dr Stephen S. Rich (University of Virginia) for helpful discussions.

Funding Sources:

This work was funded by NIH P01 HL55798 (to C.C.H. and C.A.M.), NIH R01 HL085790 (to C.C.H.), and American Heart Association 0615467U (to J.P.M.).

Clinical Perspective

Macrophage foam cell formation in the aortic wall is a key early event in atherosclerotic plaque development. In this process, macrophages uptake oxidized LDL via scavenger receptor binding, and efflux cholesterol to HDL for reverse cholesterol transport via the actions of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1, and scavenger receptor-B1 (SR-B1). ABCA1 and ABCG1 deliver cholesterol to HDL to aid in reverse cholesterol transport to the liver. If the balance of influx and efflux of cholesterol from macrophages is altered, the macrophages become lipid-laden and undergo apoptosis and secondary necrosis, dumping lipid into the extracellular space in the arterial wall and promoting atherosclerosis progression. Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) have an increased incidence of atherosclerosis. Previous studies in animal models of T2DM demonstrate a decrease in ABCG1 expression and lipid efflux to HDL. The current study extends these finding to humans, providing a potential mechanism for the accelerated vascular disease in T2DM. ABCG1 expression is significantly reduced in macrophages isolated from patients with T2DM compared to controls. In contrast, expression of ABCA1 and SR-B1 were unchanged. Concomitant with reduced ABCG1 expression, macrophages from patients with T2DM had reduced ability to efflux cholesterol to HDL, thus, triggering accumulation of cholesteryl esters within macrophages. Treatment of T2DM macrophages with a LXRα/β agonist restored ABCG1 expression and reduced cholesterol accumulation, suggesting that therapies to upregulate LXRβ may be beneficial for preventing macrophage foam cell formation in the arterial wall in patients with T2DM. Taken together, these observations suggest that decreased macrophage ABCG1 expression may contribute to impaired reverse cholesterol transport, macrophage foam cell formation, and atherosclerosis progression in patients with T2DM.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

Reference List

- 1.Haffner SM. Coronary heart disease in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1040–1042. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CD, Folsom AR, Pankow JS, Brancati FL. Cardiovascular events in diabetic and nondiabetic adults with or without history of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:855–860. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116389.61864.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunjathoor VV, Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Moore KJ, Andersson L, Koehn S, Rhee JS, Silverstein R, Hoff HF, Freeman MW. Scavenger receptors class A-I/II and CD36 are the principal receptors responsible for the uptake of modified low density lipoprotein leading to lipid loading in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49982–49988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta JL. The role of LOX-1, a novel lectin-like receptor for oxidized low density lipoprotein, in atherosclerosis. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20(Suppl B):32B–36B. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oram JF, Lawn RM. ABCA1. The gatekeeper for eliminating excess tissue cholesterol. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1173–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang N, Silver DL, Thiele C, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) functions as a cholesterol efflux regulatory protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23742–23747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy MA, Barrera GC, Nakamura K, Baldan A, Tarr P, Fishbein MC, Frank J, Francone OL, Edwards PA. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linton MF, Fazio S. Macrophages, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(Suppl 3):S35–S40. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rust S, Rosier M, Funke H, Real J, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Deleuze JF, Brewer HB, Duverger N, Denefle P, Assmann G. Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1. Nat Genet. 1999;22:352–355. doi: 10.1038/11921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klucken J, Buchler C, Orso E, Kaminski WE, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, Liebisch G, Kapinsky M, Diederich W, Drobnik W, Dean M, Allikmets R, Schmitz G. ABCG1 (ABC8), the human homolog of the Drosophila white gene, is a regulator of macrophage cholesterol and phospholipid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:817–822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaughan AM, Oram JF. ABCA1 and ABCG1 or ABCG4 act sequentially to remove cellular cholesterol and generate cholesterol-rich HDL. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2433–2443. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600218-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauldin JP, Srinivasan S, Mulya A, Gebre A, Parks JS, Daugherty A, Hedrick CC. Reduction in ABCG1 in Type 2 diabetic mice increases macrophage foam cell formation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21216–21224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkateswaran A, Laffitte BA, Joseph SB, Mak PA, Wilpitz DC, Edwards PA, Tontonoz P. Control of cellular cholesterol efflux by the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12097–12102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200367697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang N, Lan D, Chen W, Matsuura F, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9774–9779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Kurdi-Haidar B, Oram JF. LXR-mediated activation of macrophage stearoyl-CoA desaturase generates unsaturated fatty acids that destabilize ABCA1. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:972–980. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400011-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabol SL, Brewer HB, Jr., Santamarina-Fojo S. The human ABCG1 gene: Identification of LXR response elements that modulate expression in macrophages and liver. J Lipid Res. 2005 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500080-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, Kamada N, Kataoka M, Jishage K, Ueda O, Sakaguchi H, Higashi T, Suzuki T, Takashima Y, Kawabe Y, Cynshi O, Wada Y, Honda M, Kurihara H, Aburatani H, Doi T, Matsumoto A, Azuma S, Noda T, Toyoda Y, Itakura H, Yazaki Y, Kodama T. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 1997;386:292–296. doi: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podrez EA, Febbraio M, Sheibani N, Schmitt D, Silverstein RL, Hajjar DP, Cohen PA, Frazier WA, Hoff HF, Hazen SL. Macrophage scavenger receptor CD36 is the major receptor for LDL modified by monocyte-generated reactive nitrogen species. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1095–1108. doi: 10.1172/JCI8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuhara-Takaki K, Sakai M, Sakamoto Y, Takeya M, Horiuchi S. Expression of class A scavenger receptor is enhanced by high glucose in vitro and under diabetic conditions in vivo: one mechanism for an increased rate of atherosclerosis in diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3355–3364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Sawamura T, Renier G. Glucose enhances endothelial LOX-1 expression: role for LOX-1 in glucose-induced human monocyte adhesion to endothelium. Diabetes. 2003;52:1843–1850. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Sawamura T, Renier G. Glucose enhances human macrophage LOX-1 expression: role for LOX-1 in glucose-induced macrophage foam cell formation. Circ Res. 2004;94:892–901. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000124920.09738.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffin E, Re A, Hamel N, Fu C, Bush H, McCaffrey T, Asch AS. A link between diabetes and atherosclerosis: Glucose regulates expression of CD36 at the level of translation. Nat Med. 2001;7:840–846. doi: 10.1038/89969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Collins HL, Ranalletta M, Fuki IV, Billheimer JT, Rothblat GH, Tall AR, Rader DJ. Macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1, but not SR-BI, promote macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2216–2224. doi: 10.1172/JCI32057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulya A, Lee JY, Gebre AK, Thomas MJ, Colvin PL, Parks JS. Minimal lipidation of pre-beta HDL by ABCA1 results in reduced ability to interact with ABCA1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1828–1836. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Favari E, Lee M, Calabresi L, Franceschini G, Zimetti F, Bernini F, Kovanen PT. Depletion of pre-beta-high density lipoprotein by human chymase impairs ATP-binding cassette transporter A1- but not scavenger receptor class B type I-mediated lipid efflux to high density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9930–9936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fielding PE, Kawano M, Catapano AL, Zoppo A, Marcovina S, Fielding CJ. Unique epitope of apolipoprotein A-I expressed in pre-beta-1 high-density lipoprotein and its role in the catalyzed efflux of cellular cholesterol. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6981–6985. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranalletta M, Wang N, Han S, Yvan-Charvet L, Welch C, Tall AR. Decreased atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice transplanted with Abcg1−/− bone marrow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2308–2315. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242275.92915.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldan A, Pei L, Lee R, Tarr P, Tangirala RK, Weinstein MM, Frank J, Li AC, Tontonoz P, Edwards PA. Impaired development of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic Ldlr−/− and ApoE−/− mice transplanted with Abcg1−/− bone marrow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2301–2307. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240051.22944.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Out R, Hoekstra M, Hildebrand RB, Kruit JK, Meurs I, Li Z, Kuipers F, Van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. Macrophage ABCG1 deletion disrupts lipid homeostasis in alveolar macrophages and moderately influences atherosclerotic lesion development in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2295–2300. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237629.29842.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basso F, Amar MJ, Wagner EM, Vaisman B, Paigen B, Santamarina-Fojo S, Remaley AT. Enhanced ABCG1 expression increases atherosclerosis in LDLr-KO mice on a western diet. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy MA, Venkateswaran A, Tarr PT, Xenarios I, Kudoh J, Shimizu N, Edwards PA. Characterization of the human ABCG1 gene: liver X receptor activates an internal promoter that produces a novel transcript encoding an alternative form of the protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39438–39447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laffitte BA, Repa JJ, Joseph SB, Wilpitz DC, Kast HR, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. LXRs control lipid-inducible expression of the apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:507–512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021488798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cha JY, Repa JJ. The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis. The carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:743–751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinet EM, Savio DA, Halpern AR, Chen L, Schuster GU, Gustafsson JA, Basso MD, Nambi P. Liver X receptor (LXR)-beta regulation in LXRalpha-deficient mice: implications for therapeutic targeting. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1340–1349. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lund EG, Peterson LB, Adams AD, Lam MH, Burton CA, Chin J, Guo Q, Huang S, Latham M, Lopez JC, Menke JG, Milot DP, Mitnaul LJ, Rex-Rabe SE, Rosa RL, Tian JY, Wright SD, Sparrow CP. Different roles of liver X receptor alpha and beta in lipid metabolism: effects of an alpha-selective and a dual agonist in mice deficient in each subtype. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du XL, Edelstein D, Dimmeler S, Ju Q, Sui C, Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by posttranslational modification at the Akt site. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1341–1348. doi: 10.1172/JCI11235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kowluru RA, Kanwar M, Kennedy A. Metabolic memory phenomenon and accumulation of peroxynitrite in retinal capillaries. Exp Diabetes Res. 2007;2007:21976. doi: 10.1155/2007/21976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatley ME, Srinivasan S, Reilly KB, Bolick DT, Hedrick CC. Increased production of 12/15 lipoxygenase eicosanoids accelerates monocyte/endothelial interactions in diabetic db/db mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25369–25375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]