Abstract

Background

Bacteria play a role in inflammatory bowel disease and other forms of intestinal inflammation. Although much attention has focused on the search for a pathogen or inciting inflammatory bacteria, another possibility is a lack of beneficial bacteria that normally confer anti-inflammatory properties in the gut. The purpose of this study was to determine whether normal commensal bacteria could inhibit inflammatory pathways important in intestinal inflammation.

Methods

Conditioned media from Lactobacillus plantarum (Lp-CM) and other gut bacteria was used to treat intestinal epithelial cell (YAMC) and macrophage (RAW 264.7) or primary culture murine dendritic cells. NF-κB was activated through TNF-Receptor, MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways and effects of Lp-CM on the NF-κB pathway were assessed. NF-κB binding activity was measured using ELISA and EMSA. 1κB expression was assessed by Western blot analysis, and proteasome activity determined using fluorescence-based proteasome assays. MCP-1 release was determined by ELISA.

Results

Lp-CM inhibited NF-κB binding activity, degradation of IκBα and the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome. Moreover, Lp-CM directly inhibited the activity of purified mouse proteasomes. This effect was specific, since conditioned media from other bacteria had no inhibitory effect. Unlike other proteasome inhibitors, Lp-CM was not toxic in cell death assays. Lp-CM inhibited MCP-1 release in all cell types tested.

Conclusions

These studies confirm, and provide a mechanism for, the anti-inflammatory effects of the probiotic and commensal bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum. The use of bacteria-free Lp-CM provides a novel strategy for treatment of intestinal inflammation which would eliminate the risk of bacteremia reported with conventional probiotics.

Keywords: NF-kappaB, probiotics, inflammatory bowel diseases, intestinal microbiota, proteasome

Changes in gut flora have been implicated in the etiologies of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), anti- biotic-associated diarrhea, and even obesity.1–4 While an inciting bacteria or pathogen may be causal, equally plausible is the possibility that the relative absence of commensal bacteria, normally serving a protective or anti-inflammatory role, may exacerbate intestinal inflammation. Indeed, the lack of certain classes of bacteria has already been associated with human intestinal diseases. In irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), 16S rDNA studies showed a complete absence of certain Lactobacillus species in affected individuals.5 Similarly, human intestinal biopsies have demonstrated a lower proportion of Bifidobacteria in patients with IBD compared to healthy controls.6

Consequently, the use of probiotics to enhance or modify the intestinal bacteria profile has generated much interest.7 Probiotics are defined as ingested microorganisms that provide health benefits beyond their intrinsic nutritional value. The majority of probiotics are derived from bacteria that naturally colonize the human intestine.8,9 However, although commensal and probiotic bacteria may confer beneficial effects on the host, the average “recommended dose” of probiotic consists of billions of live bacteria. Several reports in the literature have raised safety concerns over the practice of ingesting such large bacterial loads, especially in sick and immunocompromised patients.10–14 Recent clinical trials of acute pancreatitis, prematurely terminated due to increased mortality in the probiotic group, further prompt caution in using live probiotics to treat disease.15

Although some protective effects of probiotics require direct bacterial-epithelial cell-to-cell contact with live bacteria, we previously demonstrated that VSL#3, a probiotic mixture used to treat pouchitis,16 produces bioactive factors that inhibit NF-κB.17 The use of bacteria-free products synthesized by bacteria, rather than the live bacteria themselves, may be an approach to improve safety by eliminating the risk of infection reported with many conventional probiotic therapies.18–20

The purpose of this study was two-fold: first, to determine whether single strains of commensal bacteria, which commonly colonize the GI tract, secrete bioactive factors with anti-inflammatory properties. Second, if found, to define the mechanism by which these bioactive factors exert their anti-inflammatory effects. Here we report that a commensal bacteria, Lactobacillus plantarum, produces bioactive factors (conditioned media) that inhibit chymotrypsin-like proteasome function and thus broadly influence the inflammatory activation of NF-κB pathways due to multiple stimuli and in various cell lines. This effect was specific to L. plantarum, as the other bacteria tested did not elicit these effects. The use of bacteria-free L. plantarum-conditioned media (Lp-CM) provides a novel strategy for treatment of intestinal inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Bacteria-Conditioned Media

The Escherichia coli (F18 strain), a normal commensal strain of E. coli and a generous gift of Dr. Beth McCormick, and EPEC (enteropathogenic E. coli, gift of Dr. Gail Hecht) were grown using Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates and LB broth (Difco, Detroit, MI). Bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C under agitating conditions. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, strain 14028) was grown in LB as above, but under microaerophilic, nonagitating conditions as previously described.21 The Bacteroides fragilis strain (ATCC No. 25285) and the Bifidobacterium breve (ATCC No. 15700) were grown overnight in chopped meat broth or on blood agar plates (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) under GasPak (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical, New York, NY) anaerobic conditions. All bacterial suspensions were grown to the same Optical Density (as measured at 600 nm) prior to harvest. Conditioned media was prepared by aseptic filtration of the suspension culture through 0.22 μm low protein binding cellulose acetate filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

The L. plantarum and L. paracasei strains used in this study were the generous gift of Dr. Stig Bengmark. L. plantarum, L. paracasei and L. acidophilus (ATCC No. 53544) were grown first in MRS (DeMan Rogosa & Sharpe, Difco) broth at 37°C, 5% CO2 under non-agigating conditions, centrifuged (20 min, 5400 rpm), and resuspended in modified Hank’s balanced saline solution (HBSS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 0.04 M MgSO4, 0.03 M MnSO4, 1.15 M K2PO4, 0.36 M sodium acetate, 0.88 M ammonium citrate, 10% polysorbate (growth factor for Lactobacillus sp) and 20% dextrose, then propagated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2 nonagitating conditions (2 × 109 cfu/mL). The culture was again centrifuged and the supernatant (conditioned media) aseptically filtered using 0.22 μm low protein binding cellulose acetate filters (Millipore).

Cell Culture

Murine RAW 264.7 macrophage cells (ATCC No. TIB-71) were maintained at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 4 mM L-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum and used up to passage 30.

YAMC (young adult mouse colon) cells (gift of Dr. R. Whitehead, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN)22 were maintained under permissive conditions (33°C) in RPMI 1640 medium with 5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, 5U/mL murine IFN-γ (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY), 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 50 U/mL penicillin, supplemented with ITS+ Premix (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), and differentiated under nonpermissive conditions at 37°C as previously described.17 Cells were pretreated with Lp-CM for 4 hours, then treated with either TNF-α, 30 ng/mL for 30 minutes (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), flagellin, 100 ng/mL for 30 minutes (Axxora LCC, San Diego, CA), or poly dI:dC, 50 μg/mL for 16 hours (Invivogen, San Diego, CA).

Preparation of Primary Murine Dendritic Cells

Dendritic cells were isolated from the hindlimbs of 6-week-old C57/Bl6 female mice using the method of Inaba et al.23 Briefly, bone marrow was collected by passing HBSS through the hindlimb, followed by centrifugation and addition of 5 mL sterile Tris-NH4Cl buffer. RPMI complete medium (10% FCS, 1× penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine, 250 μg/ml gentamicin) was then added and cells centrifuged again. Cells were resuspended in complete RPMI supplemented with 2.5 ng/mL GM-CSF (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) and 5 ng/mL IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and plated on 6-well plates. On day 7–9, cells were collected, pelleted, resuspended in complete RPMI, and plated on 24-well plates. After 4 hours, cells were treated with conditioned medium for 3 hours followed by treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) overnight, then supernatant collected for MCP-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Preparation of Nuclear Extracts

Nuclear extracts were harvested utilizing a method modified from Inan et al.24 Briefly, cells were washed and harvested in phosphate-buffered saline, then incubated 15 minutes in extract lysis buffer (10 mM Hepes, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM sucrose, 0.05% Nonidet P-40 (NP40), 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 1× complete protease inhibitor). Nucleus-containing pellets were rinsed with extract lysis buffer without NP40 and incubated 40 minutes in high salt buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 1.5 mM MgCL2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1× complete protease inhibitor; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). The nuclear extract was removed and combined with low salt buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1× complete protease inhibitor). Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad protein assay (Hercules, CA).

NF-κB electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA): At room temperature, nuclear extracts (5–10 μg) were incubated with 5 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2% Ficoll, 0.5 mM DTT, 37.5 mM KCl, 1 μg poly dI:dC (Roche), and 50,000 cpm of a γ-32P-labeled probe encoding the NF-κB consensus sequence (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCC CAGGC-3′) (Promega, Madison, WI). Samples were electrophoresed on a native 5% polyacrylamide gel. The gels were then dried and exposed to film. To determine oligonucleotide specificity, a 100-fold excess cold oligonucleotide was added to the reaction mixture prior to incubation with probe (data not shown).

MCP-1 ELISA

YAMC and RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with Lp-CM for 4 hours and subsequently treated with TNF-α 30 ng/mL to stimulate NF-κB activation. Dendritic cells were pretreated with Lp-CM or vehicle control HBSS for 3 hours and then treated overnight with LPS (1 μg/mL). Supernatants were harvested and tested for the production of MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) using a mouse MCP-1 ELISA kit (Pierce Endogen, Rockford, IL) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell Death Assay

Sample preparation and cell death ELISA assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Applied Science).

IκB Western Blot Analysis

Twenty micrograms of protein per lane was resolved on 11% SDS-PAGE and transferred using a semi-dry transfer system (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer (200 mL MeOH, 3.03 g Tris, and 14.4 g glycine/L) onto 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore).25 Membranes were blocked in 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk in TBS-Tween (Tris-buffered saline, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, with 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20) prior to incubation with primary Anti-IκB-α antibody (sc-1643, Santa Cruz Bio-technology, Santa Cruz, CA) and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Fort Washington, PA). Blots were exposed to autoradiographic film and then visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Supersignal, Pierce).

Proteasome Assay

Cells were harvested as previously described.17 Proteasome activity was measured using a proteasome assay kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) with 20 μg of each sample added to proteasome assay reaction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.6, 0.03% (wt/vol) SDS), then 10 μM of the substrate suc-leu-leu-val-tyr-AMC (SLLVY-AMC) was added. Proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity was determined by measuring the fluorogenic signal generated by cleavage and release of the fluorogenic compound AMC (7-amino-4-methylcoumarin) over time. Fluorescence (excitation 380 nm, emission 460 nm) was measured with a Synergy-2 fluorometer (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT) and proteasome activity was determined by calculating the rate (slope) of AMC production over time using KC4 software (Bio-Tek Instruments). Cells were treated with MG132 as a positive inhibitor control at a concentration of 25 μM and untreated cells with DMSO as a vehicle control for MG132.

Proteasome assays from purified liver preparations were performed as described above except that a 96-well plate reader (either Biotek Synergy-2, or Varian Eclipse) was used to screen fractions, and in addition to MG132, epoxomicin (Calbiochem:EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ), a highly specific proteasome inhibitor,26 was used at 5 μM, as a positive inhibitor control to ensure that preparations contained pure proteasome activity. Fluorescence measurements were taken every minute and the slope (proteasome activity) was calculated using KC4 software (for Bio-Tek plate-reader) or Cary-Eclipse software (for Varian plate-reader). Concentrations of the SLLVY-AMC substrate were varied from 25 μM to 100 μM, along with varying concentrations of Lp-CM, in order to perform the Dixon plot to determine the type of inhibition. For the Dixon plot analysis the slope of the reaction was used within the first 5 minutes, to calculate the initial reaction rate, or Vi, with readings being taken every minute for 30 minutes thereafter. These data were then analyzed and Dixon plot generated using Grafit software v. 6 (Erithacus, West Sussex, UK).

Isolation and Purication of Proteasome (20S)

Purified proteasomes were prepared based on the method described by Hirano et al,27 with several modifications as follows: Mice were male 8-week-old CD-1 mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Each excised mouse liver was homogenized in 2 mL ice-cold homogenizing buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM DTT) then centrifuged at 70,000g for 1 hour at 4°C (Sorvall Ultra Pro 80 centrifuge with T-865). Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 10%, then the supernatant was mixed with ≈20 mL of Q-Sepharose (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated with Buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 10% glycerol and 1 mM DTT) for 30 minutes, then gently centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes (Sorvall RC 5C centrifuge with SS-34 rotor). The supernatant was discarded, Q-Sepharose was suspended in Buffer A, and packed into a glass chromatography column (2 × 15 cm, Pharmacia, Gaithersburg, MD). Proteins were eluted by a linear gradient of NaCl from 0–0.8 M using 120 mL each of Buffers A and B (Buffer A plus 0.8 M NaCl), fractions of 1.5 mL each were collected using a fraction collector (Gilson, Worthington, OH). The eluted protein fractions were measured at 280 nm (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA; DU 530) and salt concentration was monitored using a conductivity meter (Radiometer CDM 210). Eluted peaks were tested for proteasomal activity using the substrate suc-LLVY-AMC 65 μM as described above. Excess salt was removed using dialysis tubing, active fractions were combined, and polyethylene-glycol was added to a final concentration of 15% while stirring gently. After 15 minutes the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 minutes, the supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate dissolved into Buffer A. The proteasomal activity of separated fractions was confirmed using the substrate SLLVY-AMC and the highly specific proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin (Calbiochem).26 The final protein concentration was determined using absorbance at 280 nm. BSA was used as a calibration standard.

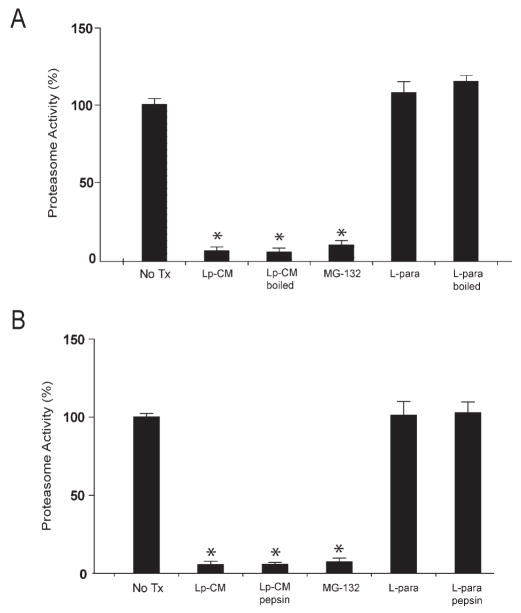

Physical Characterization of Lp-CM Bioactive Factors

Lp-CM was tested for heat stability by boiling for 10 minutes and for protease sensitivity by pepsin digestion, as previously described, prior to testing for bioactivity in proteasome assays.28

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Instat software (GraphPad Software, San Diego CA). Graphs represent mean ± standard deviation for 3 separate experiments, and in each experiment each treatment group was performed in triplicate unless otherwise specified. Experiments were repeated a minimum of 3–6 times each. For Figure 6, vehicle and Lp-CM treated sample pairs were compared using Student’s t-test (P < 0.05 was accepted as a level of statistically significant difference).

FIGURE 6.

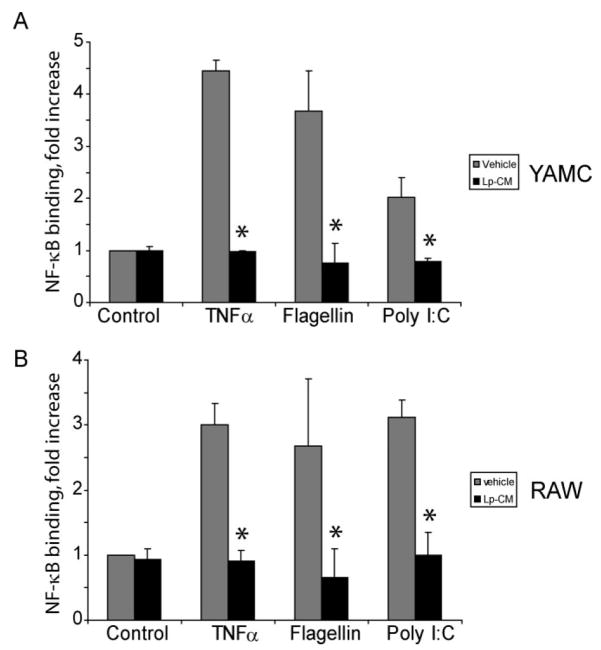

Pretreatment with Lp-CM inhibits NF-κB activation by multiple signaling pathways. Lp-CM was used to treat YAMC cells, an intestinal epithelial cell line derived from mouse large intestine (A) or RAW 264.7 cells, a murine macrophage cell line (B). Cells were activated either with 100 ng/mL flagellin (TLR5 ligand, MyD88-dependent), or with poly dI:dC (TLR3 ligand, MyD88-independent) and NF-κB activity was tested using an NF-κB ELISA assay (Active Motif) as described in Materials and Methods. TNF-α activation is also shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments and vehicle (gray bars) versus Lp-CM treated sample (black bars) pairs were compared using Student’s t-test (P < 0.05 was accepted as a level of statistically significant difference).

RESULTS

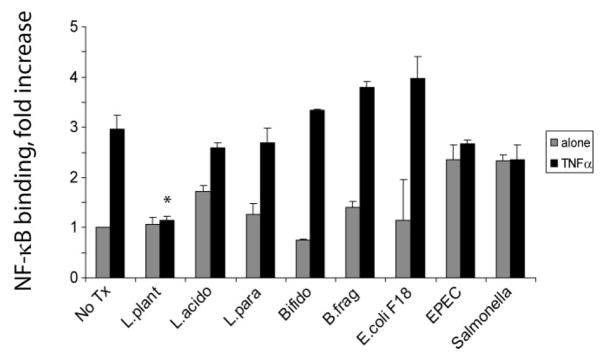

Assessment of Intestinal Bacteria-Conditioned Media Inhibition of NF-κB Binding in Gut Epithelial Cells

To assess the ability of soluble factors from different intestinal bacteria to inhibit NF-κB, intestinal epithelial cells (YAMC cells) were pretreated with conditioned media from several different Gram-positive and Gram-negative commensal bacteria, and then treated with TNF-α to stimulate NF-κB. Nuclear extracts were harvested and analyzed for binding activity of NF-κB using a commercially available ELISA assay (Active Motif). As shown in Figure 1, only Lp-CM inhibited NF-κB.

FIGURE 1.

Assessment of intestinal bacteria conditioned media to inhibit NF-κB binding in gut epithelial cells. YAMC cells were either pretreated with conditioned media alone from the intestinal bacteria indicated (gray bars), or pre-treated and then stimulated with 30 ng/mL TNF-α for 30 minutes (black bars). A commercially available NF-κB ELISA (Active Motif) was then used to test nuclear extracts and determine degree of NF-κB binding. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for a minimum of 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA analysis using Bonferroni correction).

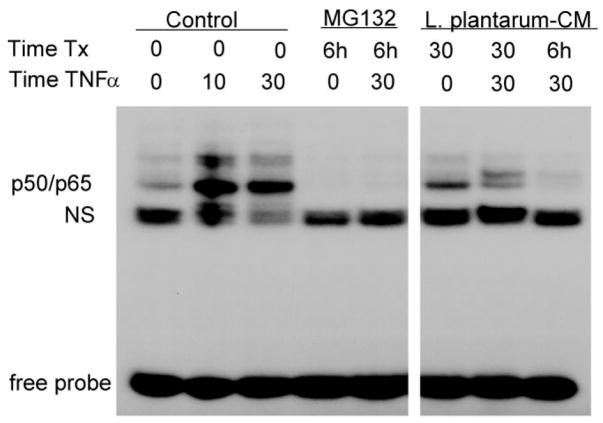

Lactobacillus plantarum CM Inhibits NF-κB Binding in Intestinal Epithelial Cells (IEC)

To further define the nature of the NF-κB inhibition, YAMC cells were pretreated with Lp-CM for the times indicated, treated with TNF-α to stimulate NF-κB, then cell nuclear extracts were harvested for analysis by EMSA to directly examine binding of NF-κB to its target DNA consensus sequence (Fig. 2). Results for Lp-CM were compared to the proteasome inhibitor MG132, which inhibits basal and TNF-α-stimulated NF-κB activity. It can be seen that Lp-CM inhibits binding of the p50/p65 isoform of NF-κB. This observation was confirmed by NF-κB ELISA, which was performed with a longer time course, up to 6 hours (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Lp-CM inhibits NF-κB binding in intestinal epithelial cells. YAMC cells were pretreated with either MG132 or Lp-CM for the times indicated (Time Tx), and then treated with 30 ng/mL TNF-α for the times indicated prior to nuclear extract harvest and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Pretreatment with Lp-CM blocks TNF-α-induced NF-κB binding. Nonspecific binding (NS) indicated, free probe is at bottom of gel. Blot shown is representative of 3 independent experiments.

Using antibodies against the other NF-κB subunits in supershift assays, it was confirmed that the p50/p65 subunit is the major NF-κB isoform inhibited by Lp-CM (data not shown).

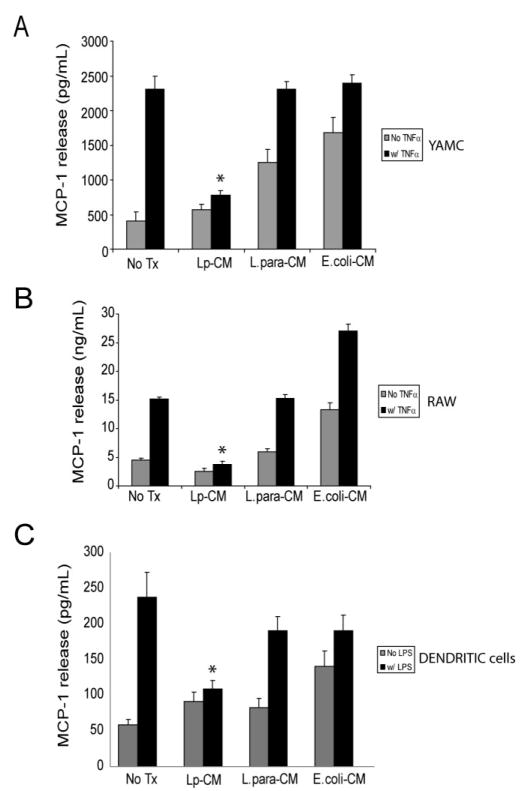

Lp-CM Inhibits Release of MCP-1 from Multiple Cell Types

In order to establish whether Lp-CM inhibits target genes important in the intestinal inflammatory response, we measured release of MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1), an inflammatory chemokine important in leukocyte recruitment to areas of inflammation and a well-described downstream gene target of NF-κB.29,30 YAMC cells were pretreated with Lp-CM and subsequently treated with TNF-α to activate NF-κB. Supernatants were harvested and tested for the production of MCP-1 by ELISA (Fig. 3A). Lp-CM attenuated the release of MCP-1 in response to TNF-α compared to both untreated control and L. paracasei and E. coli-CM treated controls. Since macrophages play an important role in mucosal immunity, the murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 was similarly tested and also demonstrated Lp-CM blockade of TNF-α-induced MCP-1 release (Fig. 3B). Finally, Lp-CM decreased MCP-1 release from primary murine dendritic cells in response to LPS stimulation (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that intestinal epithelial cells, white blood cells, and dendritic cells all exhibit a dampening of the inflammatory response upon exposure to Lp-CM, providing supporting evidence that Lp-CM exerts its effects across multiple cell types important in the intestinal inflammatory response.

FIGURE 3.

Lp-CM inhibits TNF-α-mediated MCP-1 release in multiple cell types. A: YAMC cells were treated with either Lp-CM, L. paracasei-CM, or E. coli-CM for 4 hours, and then with TNF-α (30 ng/mL) to stimulate NF-κB. Supernatants were harvested after 6 hours and and then assayed for release of the chemokine MCP-1, a downstream gene target of NF-κB, using a commercially available ELISA. Results were compared to vehicle-treated control (No Treatment, column 1), or TNF-α treatment alone (column 2). Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA analysis using Bonferroni correction). B: RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells were treated with either Lp-CM, L. paracasei-CM, or E. coli-CM for 4 hours, then with TNF-α (30 ng/mL) to activate NF-κB. Supernatants were harvested after 6 hours and and then assayed for release of MCP-1 using a commercially available ELISA. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA analysis using Bonferroni correction). C: Primary murine dendritic cells were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and then treated with either Lp-CM, L. paracasei-CM, or E. coli-CM for 3 hours, followed by LPS treatment for 16 hours to activate NF-κB. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA analysis using Bonferroni correction).

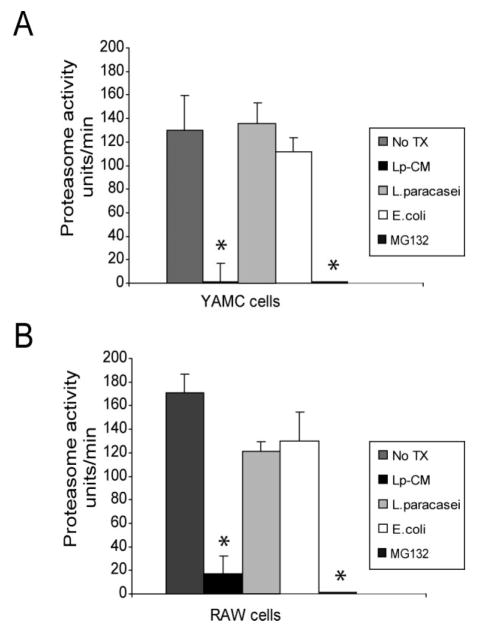

Lp-CM Inhibits Proteasome Activity in Different Cell Types

We and others have shown that the probiotic mixture VSL#3 inhibits proteasome function in IEC.17,31,32 To determine whether Lp-CM affects proteasome function, CTL-like proteasome activity was measured in extracts from YAMC cells (Fig. 4A) and RAW macrophages (Fig. 4B) after treatment with Lp-CM, E. coli-CM, L. paracasei-CM, or the synthetic proteasome inhibitor MG132. Only Lp-CM inhibited the CTL-like activity of the proteasome.

FIGURE 4.

Lp-CM inhibits proteasome activity in different cell types. A: YAMC cells were treated with Lp-CM, L. paracasei-CM, or E. coli-CM or the synthetic proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 1 hour, then harvested for proteasome assay using SLLVY-AMC substrate (see text). Results are expressed as proteasome activity in fluorescence units/min over time. Activity was determined by measuring fluorescence (excitation 380 nm, emission 460 nm) every 3 minutes for 30 minutes to determine reaction rate. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). B: RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were treated with Lp-CM, L. paracasei-CM, or E. coli-CM or the synthetic proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 1 hour, then harvested for proteasome assay using SLLVY-AMC substrate as in panel A. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction).

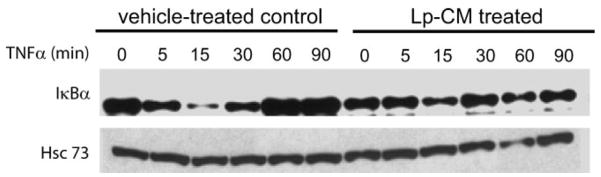

Lp-CM Preserves Proteins Normally Degraded by the Proteasome

The NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα, normally sequesters NF-κB in the cytoplasm in an inactive state but can be degraded by the CTL-like activity of the proteasome, allowing release and activation of NF-κB. Hence, to determine whether proteasome inhibition by Lp-CM resulted in blocked degradation of IκBα, YAMC cells were either pre-treated with Lp-CM or HBSS, then stimulated with TNF-α and harvested over a 90-minute time course for Western blot analysis of IκBα. Compared to HBSS controls, Lp-CM pretreatment inhibited degradation of IκBα (Fig. 5), consistent with the Lp-CM inhibition of proteasome activity shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 5.

IκBα degradation is inhibited by Lp-CM. YAMC cells were pretreated with either vehicle control (HBSS) or with Lp-CM for 1 hour, then stimulated with TNF-α (30 ng/mL) and harvested at the timepoints (min) indicated. Samples were then subjected to Western blot analysis for the presence of IκBα. Hsc73 (heat shock cognate 73) was used as a loading control. Blot shown is representative of 3 separate experiments.

Lp-CM Inhibits TLR Signaling Pathways

In addition to stimulation by TNF-α, NF-κB can be activated by Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways. TLRs recognize various bacterial and viral components and play a key role in innate immunity. If inhibition of NF-κB occurs through a mechanism of proteasome blockade, we reasoned that Lp-CM should inhibit the effect of multiple NF-κB-activating ligands which are located upstream of the proteasome. Hence, the effect of Lp-CM on MyD-88-dependent and MyD-88-independent TLR pathways was investigated by NF-κB ELISA. Following Lp-CM pretreatment the protein flagellin (ligand for TLR5), which is dependent on signaling through the adaptor molecule MyD88, and the nucleotide poly dI:dC (ligand for TLR3), which acts through a MyD88-independent pathway, were used to activate NF-κB. Lp-CM inhibited NF-κB binding in response to both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent ligands in both a macrophage cell line and an IEC line (Fig. 6A, B). Conditioned media from L. paracasei failed to inhibit NF-κB (data not shown).

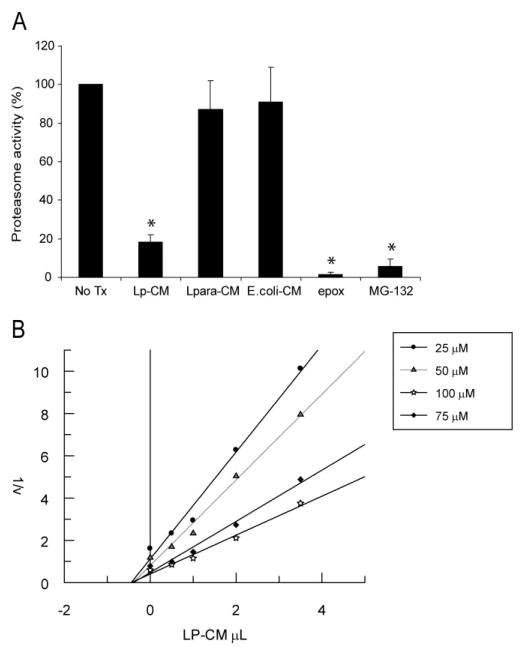

Lp-CM Directly Inhibits Proteasome Activity

The data from Figures 4, 5, and 6 support the conclusion that Lp-CM inhibits NF-κB through inhibition of proteasome function, but do not provide any indication as to whether the inhibition occurs indirectly, mediated through signal transduction pathways, or whether this occurs as a result of a direct interaction with the proteasome itself. To determine whether Lp-CM was acting directly on the proteasome, mouse liver proteasomes were isolated and proteasome activity measured after treatment with Lp-CM, or conditioned media from L. paracasei or E. coli. The proteasome inhibitors epoxomicin, MG132, and lactic acid were included as additional controls. Lp-CM specifically directly inhibits the chymotrypsin-like activity in purified proteasome preparations from mouse liver (Fig. 7A). In addition, based on Dixon plot analysis, Lp-CM exhibits a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on the proteasome, and is a noncompetitive, reversible proteasome inhibitor (Fig. 7B). Preliminary characterization of the proteasome-inhibiting bioactive factors in Lp-CM indicate that they are of small molecular weight (less than 10 kDa, data not shown), heat stable (Fig. 8A), and resistant to pepsin digestion (Fig. 8B), indicating they are not bacterial proteins.

FIGURE 7.

Lp-CM directly inhibits proteasome activity and is a reversible proteasome inhibitor. A: Proteasomes were purified from mouse liver as described in Materials and Methods, treated with Lp-CM, L. paracasei-CM, or E. coli-CM, and then proteasome assays were performed immediately to determine whether the effect of Lp-CM was a direct inhibitory effect on the proteasome. A fluorometer was used to record measurements every minute for 30 minutes (excitation 380 nm, emission 460 nm) and slopes were calculated using CaryEclipse and KC4 software (see Materials and Methods). Results are expressed as percent activity, with untreated proteasome preparations defined as 100% activity (y-axis). Epoxomicin, a highly specific proteasome inhibitor, was used as an inhibitor control to ensure absence of other contaminating proteases. MG132 is also shown. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). B: Proteasome assays were performed using varying concentrations of SLLVY-AMC substrate and varying concentrations of Lp-CM as indicated. Reaction rates were used within the first 5 minutes of starting the assay in order to determine Vi (initial reaction rate) for generation of the Dixon plot data. Dixon plots were generated using Grafit software.

FIGURE 8.

Bioactive factors in Lp-CM are heat-stable and protease-resistant. A: Purified proteasomes from mouse liver were treated with Lp-CM or L. paracasei-CM that was thoroughly boiled for 10 minutes. Treatments were added directly to the proteasome preparation, SLLVY-AMC substrate was added, and the samples assayed for proteasome activity as previously described (excitation 380 nm, emission 460 nm). Slopes were calculated using CaryEclipse software (see Materials and Methods) and results expressed as percent activity, with untreated proteasome preparations defined as 100% activity (y-axis). MG132 is also shown. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). B: Proteasome assays were performed as in panel A except that Lp-CM and L. paracasei-CM were subjected to protease digestion using a pepsin digestion method as previously described.28 Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction).

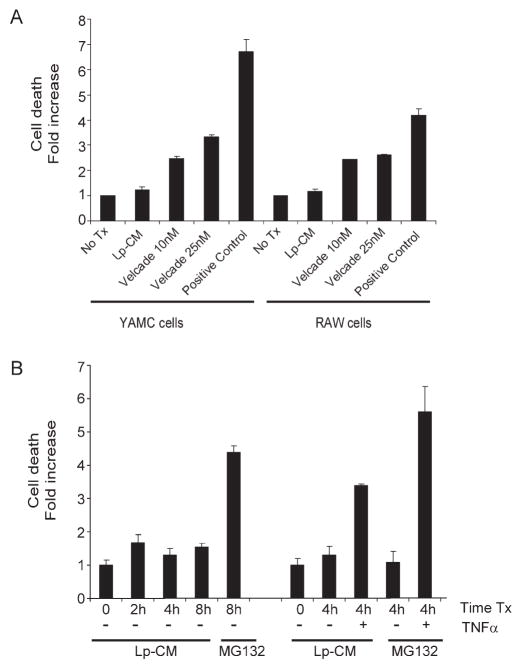

Lp-CM Does Not Induce Increased Cell Death at Concentrations Used to Inhibit Endogenous NF-κB and Proteasome Activity

NF-κB, while an important mediator of inflammation, also serves an important anti-apoptotic role in the gut.33,34 Therefore, the possibility that blockade of NF-κB by Lp-CM would affect cell viability was investigated using an apoptosis cell death assay. Both RAW 264.7 macrophage cells and YAMC cells were treated with Lp-CM at the same dose and for the same time period used previously to inhibit NF-κB activation and proteasome activity. In contrast to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade®), which is used clinically for the treatment of human hematologic malignancies,35 no toxicity was observed with Lp-CM after 4 hours of exposure (Fig. 9A). A time course of cell death with Lp-CM in YAMC cells from 0–8 hours is also shown (Fig. 9B). Even at 8 hours of exposure, there is less cell death seen with Lp-CM than with MG132, another proteasome inhibitor. However, when TNF-α is added after pretreatment with Lp-CM for 4 hours, there is increased cell death after addition of TNF-α (Fig. 9B). The amount of cell death after addition of TNF-α in the Lp-CM-treated cells was still significantly less than cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 after TNF-α, and was less than what was observed with CAM, a traditional inducer of apoptosis. No increase in cell death was seen after 4 hours when TNF-α was added prior to, or at the same time as Lp-CM (data not shown).

FIGURE 9.

Lp-CM does not induce increased cell death compared to other proteasome inhibitors. A: Lp-CM was used to treat YAMC cells or RAW cells for 4 hours and the effects of Lp-CM on cell death were determined using a commercially available cell death ELISA assay. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib is also shown. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 3 separate experiments. B: YAMC cells were pretreated with either MG132 or Lp-CM for the times indicated (0--8 hours). Cells pretreated with either MG132 or Lp-CM for 4 hours were then treated with 30 ng/mL TNF-α for an additional 4 hours and cell death measured by ELISA. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for 2 separate experiments, performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

Enteric flora play an essential role in the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and gastrointestinal health.36–39 Interestingly, these critical roles in intestinal homeostasis appear largely mediated through TLR signaling.37,40 TLRs play a key role in innate immunity by recognizing various bacterial and viral products, thus forming the first line of defense in protecting the host against pathogens.41 However, TLRs do not discriminate between normal enteric flora and pathogens. They activate inflammatory pathways for host defense, but are concurrently critical for activating signaling pathways necessary for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis.37,40

How the gut preserves this balance and maintains intestinal homeostasis, in the presence of a large bacterial load, remains the subject of intense study. Dysregulation of inflammatory signaling pathways, resulting in an aberrant immune response, is thought to play an important role in the development of inflammatory colitis both in humans and in animal models.42,43 Furthermore, studies of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) have demonstrated that changes in the equilibrium of intestinal bacteria occur in areas of active inflammation, for example, fewer Bifidobacteria species and more Enterobactericiae species have been reported as being associated with active disease.6

Lactobacillus plantarum is one of the most common Lactobacillus species in the gut of healthy human volunteers.44 It is a member of the phylum Firmicutes, one of two major phyla that dominate the intestinal microbiota.45 In addition, live L. plantarum ameliorates disease and decreases inflammation in an IL-10 knockout mouse model of colitis46 as well as in a dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) rat model of inflammatory colitis.47 In this study we show that Lp-CM uniquely inhibits NF-κB binding activity in response to TNF-α attenuates release of MCP-1, a proinflammatory chemokine and downstream gene target of NF-κB, and directly, reversibly inhibits proteasome function. Lp-CM inhibited NF-κB activation from TNF-receptor, MyD88-dependent, and MyD88-independent pathways, consistent with its downstream inhibitory effects on the proteasome. Despite its potent effects on proteasome function, Lp-CM resulted in less cell death and toxicity compared to other proteasome inhibitors, even in the presence of TNF-α.

The findings here raise the possibility that the absence of certain commensals important in controlling NF-κB activation may predispose to the development of inflammatory conditions such as IBD. Studies both in humans and in animals have now indicated that modulation of proteasome function and proteasome subunit expression likely plays a role in colitis,31,48,49 and increased chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity has been reported in biopsies from patients with active CD.31 Our findings may explain why some probiotics which inhibit NF-κB and proteasome function such as L. plantarum, a commensal and probiotic, and VSL#3, another probiotic mixture that has been used clinically to treat pouchitis, confer protection against intestinal inflammation.

Although in our screen only L. plantarum was found to possess these properties, it would be presumptuous to assume that only this bacteria possesses this unique ability. It is more likely that other commensals similarly affect NF-κB activation to assist the host in minimizing aberrant or overexuberant inflammatory responses. For example, it has been shown that live L. casei was able to inhibit IκBα degradation during Shigella infection.50 Another recent study51 showed that a decrease in the commensal bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was associated with endoscopic recurrence of ileal CD. Furthermore, the bacteria-derived supernatant was shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties both in vitro and in a TNBS animal model of colitis.51 Hence, it appears likely that certain commensals such as L. plantarum, F. prausnitzii, and others play a very active anti-inflammatory role.

The balance of gut pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling due to bacteria and host interplay may be what ultimately determines whether there is development of disease or whether intestinal homeostasis is maintained. As L. plantarum is a common commensal, it is tempting to speculate that the factors it produces in Lp-CM may possess anti-inflammatory properties that can block development of colitis, without compromising the ability of the host to fight off infection.

Interestingly, lipoteichoic acid from L. plantarum (pLTA) has been shown to exhibit inhibitory activity against Staphylococcus aureus LTA-induced TNF-α production, and to block NF-κB activated by other TLR ligands such as LPS.52,53 In the case of pLTA, the mechanism of NF-κB inhibition was found to be a downregulation of TLR4, NOD1, and NOD2 receptors.53 These studies, along with ours, further highlight the existence of multiple L. plantarum-derived factors with different bioactivity and antiinflammatory function. Future characterization of these various bioactive factors will further enhance our understanding of the crosstalk between commensal bacteria and the gut.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed in the Martin Boyer Research Laboratories at the University of Chicago and in the Gastrointestinal Diseases Research Unit laboratories (GIDRU) at Queen’s University. We thank Curtis Noordhof for expert technical assistance and Ian Spreadbury at Queen’s University for computer support. We also thank Dr. Stig Bengmark for generous gifts of the Lactobacillus strains used in this study, Gail Hecht for the EPEC strain of E. coli, Beth McCormick for the F18 strain of E. coli, and James Madara for the S. typhimurium strain.

Supported by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada (to E.O.P), and by National Institutes of Health grants DK064840 (to E.O.P), HD043839 (to E.C.C), AT004044 (to E.O.P. and E.C.C.), DK47722 (to E.B.C.), and Digestive Disease Research Core Center grant DK42086.

References

- 1.Canny GO, McCormick BA. Bacteria in the intestine, helpful residents or enemies from within? Infect Immun. 2008;76:3360–3373. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00187-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, et al. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan F, Polk DB. Probiotics as functional food in the treatment of diarrhea. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:717–721. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000247477.02650.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassinen A, Krogius-Kurikka L, Makivuokko H, et al. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:24–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mylonaki M, Rayment NB, Rampton DS, et al. Molecular characterization of rectal mucosa-associated bacterial flora in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:481–487. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000159663.62651.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdu EF, Collins SM. Irritable bowel syndrome and probiotics: from rationale to clinical use. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:697–701. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000182861.11669.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raz I, Gollop N, Polak-Charcon S, et al. Isolation and characterisation of new putative probiotic bacteria from human colonic flora. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:725–734. doi: 10.1017/S000711450747249X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin YP, Thibodeaux CH, Pena JA, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppress proinflammatory cytokines via c-Jun. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1068–1083. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antony SJ. Lactobacillemia: an emerging cause of infection in both the immunocompromised and the immunocompetent host. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:83–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horwitch CA, Furseth HA, Larson AM, et al. Lactobacillemia in three patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1460–1462. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.6.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlegel L, Lemerle S, Geslin P. Lactobacillus species as opportunistic pathogens in immunocompromised patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:887–888. doi: 10.1007/s100960050216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalima P, Masterton RG, Roddie PH, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus infection in a child following bone marrow transplant. J Infect. 1996;32:165–167. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(96)91622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Groote MA, Frank DN, Dowell E, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG bacteremia associated with probiotic use in a child with short gut syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:278–280. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000154588.79356.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Buskens E, et al. Probiotic prophylaxis in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:651–659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60207-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Helwig U, et al. Prophylaxis of pouchitis onset with probiotic therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1202–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrof EO, Kojima K, Ropeleski MJ, et al. Probiotics inhibit nuclear factor-kappaB and induce heat shock proteins in colonic epithelial cells through proteasome inhibition. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1474–1487. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rautio M, Jousimies-Somer H, Kauma H, et al. Liver abscess due to a Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain indistinguishable from L. rhamnosus strain GG. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1159–1160. doi: 10.1086/514766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sipsas NV, Zonios DI, Kordossis T. Safety of Lactobacillus strains used as probiotic agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1283–1284. doi: 10.1086/339947. author reply 1284–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz P, Bouza E, Cuenca-Estrella M, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia: an emerging infectious disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1625–1634. doi: 10.1086/429916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormick BA, Colgan SP, Delp-Archer C, et al. Salmonella typhimurium attachment to human intestinal epithelial monolayers: transcellular signalling to subepithelial neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:895–907. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehead RH, VanEeden PE, Noble MD, et al. Establishment of conditionally immortalized epithelial cell lines from both colon and small intestine of adult H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:587–591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inan MS, Rasoulpour RJ, Yin L, et al. The luminal short-chain fatty acid butyrate modulates NF-kappaB activity in a human colonic epithelial cell line. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:724–734. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojima K, Musch MW, Ren H, et al. Enteric flora and lymphocyte-derived cytokines determine expression of heat shock proteins in mouse colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1395–1407. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng L, Mohan R, Kwok BH, et al. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10403–10408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirano Y, Murata S, Tanaka K. Large- and small-scale purification of mammalian 26S proteasomes. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:227–240. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Y, Drabik KA, Waypa TS, et al. Soluble factors from the probiotic Lactobacillus GG activate MAP kinases and induce cytoprotective heat shock proteins in intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1018–1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00131.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinecker HC, Loh EY, Ringler DJ, et al. Monocyte-chemoattractant protein 1 gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells and inflammatory bowel disease mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:40–50. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacDermott RP. Chemokines in the inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:266–272. doi: 10.1023/a:1020583306627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visekruna A, Joeris T, Seidel D, et al. Proteasome-mediated degradation of IkappaBalpha and processing of p105 in Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3195–3203. doi: 10.1172/JCI28804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jijon H, Backer J, Diaz H, et al. DNA from probiotic bacteria modulates murine and human epithelial and immune function. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1358–1373. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert A, et al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2007;446:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature05698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen LW, Egan L, Li ZW, et al. The two faces of IKK and NF-kappaB inhibition: prevention of systemic inflammation but increased local injury following intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Nat Med. 2003;9:575–581. doi: 10.1038/nm849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCloskey SM, McMullin MF, Walker B, et al. The therapeutic potential of the proteasome in leukaemia. Hematol Oncol. 2008;26:73–81. doi: 10.1002/hon.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, et al. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, et al. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, et al. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J, Mo JH, Katakura K, et al. Maintenance of colonic homeostasis by distinctive apical TLR9 signalling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1327–1336. doi: 10.1038/ncb1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abreu MT, Fukata M, Arditi M. TLR signaling in the gut in health and disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:4453–4460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elson CO, Sartor RB, Tennyson GS, et al. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1344–1367. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Packey CD, Sartor RB. Interplay of commensal and pathogenic bacteria, genetic mutations, and immunoregulatory defects in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. J Intern Med. 2008;263:597–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahrne S, Nobaek S, Jeppsson B, et al. The normal Lactobacillus flora of healthy human rectal and oral mucosa. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:88–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultz M, Veltkamp C, Dieleman LA, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum 299V in the treatment and prevention of spontaneous colitis in inter-leukin-10-deficient mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:71–80. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osman N, Adawi D, Ahrne S, et al. Modulation of the effect of dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute colitis by the administration of different probiotic strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:320–327. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000017459.59088.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conner EM, Brand S, Davis JM, et al. Proteasome inhibition attenuates nitric oxide synthase expression, VCAM-1 transcription and the development of chronic colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:1615–1622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fitzpatrick LR, Small JS, Poritz LS, et al. Enhanced intestinal expression of the proteasome subunit low molecular mass polypeptide 2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:337–348. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0796-7. discussion 348–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tien MT, Girardin SE, Regnault B, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of Lactobacillus casei on Shigella-infected human intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:1228–1237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16731–16736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim HG, Lee SY, Kim NR, et al. Inhibitory effects of Lactobacillus plantarum lipoteichoic acid (LTA) on Staphylococcus aureus LTA-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;18:1191–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HG, Kim NR, Gim MG, et al. Lipoteichoic acid isolated from Lactobacillus plantarum inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-alpha production in THP-1 cells and endotoxin shock in mice. J Immunol. 2008;180:2553–2561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]