Summary

This study described long-term outcomes of autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation (HCT) for advanced Hodgkin (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). The study included recipients of autologous HCT for HL (N=407) and NHL (N=960) from 1990–98 who were in continuous complete remission for at least 2 years post-HCT. Median follow-up was 104 months for HL and 107 months for NHL. Overall survival at 10-years was 77% (72–82%) for HL, 78% (73–82%) for diffuse large-cell NHL, 77% (71–83%) for follicular NHL, 85% (75–93%) for lymphoblastic/Burkitt NHL, 52% (37–67%) for mantle-cell NHL and 77% (67–85%) for other NHL. On multivariate analysis, mantle-cell NHL had the highest relative-risk for late mortality (2.87 (1.70–4.87)), while the risks of death for other histologies were comparable. Relapse was the most common cause of death. Relative mortality compared to age, race and gender adjusted normal population remained significantly elevated and was 14.8 (6.3–23.3) for HL and 5.9 (3.6–8.2) for NHL at 10-years post-HCT. Recipients of autologous HCT for HL and NHL who remain in remission for at least 2-years have favorable subsequent long-term survival but remain at risk for late relapse. Compared to the general population, mortality rates continue to remain elevated at 10-years post-transplantation.

Keywords: Hodgkin lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation, Overall survival

Introduction

Autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation (HCT) is effective and standard therapy for the majority of patients with relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and it is often included as part of initial treatment for selected patients at high-risk for relapse.(Haioun, et al 1997, Lazarus, et al 2001, Lazarus, et al 1999, Linch, et al 1993, Majhail, et al 2006, Philip, et al 1995, Sweetenham, et al 1999, Vose, et al 2004, Vose, et al 2001) However, disease recurrence or progression is the leading cause of treatment failure and mortality after autologous transplantation for both HL and NHL, and relapses predominantly occur within the first 2 years post-transplant.(Bolwell, et al 2002, Majhail, et al 2006, van Besien, et al 1995, Wadehra, et al 2006) Long-term outcomes of patients who survive in remission for the first 2 years after autologous HCT have not been well described. Lymphoma patients were observed to have an increased risk of late death when compared with the general population in the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study that investigated late mortality in patients who had survived 2 years or more following autologous HCT.(Bhatia, et al 2005) Also, both HL and NHL patients had an increased risk of relapse-related mortality, although specific risk-factors for late relapse and mortality in lymphoma patients were not described. We conducted a retrospective cohort study to describe the long-term outcomes of patients receiving an autologous HCT for HL and NHL who remained in continuous remission for at least 2 years following transplantation. We also conducted analyses to compare their mortality to that of the general population and to identify patient-, disease- and transplant-related factors that were predictive of late mortality and relapse.

Methods

Data Sources

Data for this study were obtained from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), which is a voluntary group of more than 500 transplant centres worldwide. Participating centres register basic information on all consecutive HCTs to the Statistical Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Detailed demographic and clinical data are collected on a representative sample of registered patients using a weighted randomization scheme. Compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Patients are followed longitudinally, with yearly follow-up. Computerized checks for errors, physician reviews of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centres ensure the quality of data. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR during the time period of this study were done with a waiver of informed consent and are compliant with the Health Insurance Privacy and Accountability Act regulations as determined by the Institutional Review Board and the Privacy Officer of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Patients

This study included patients reported to the CIBMTR who had received an autologous HCT for HL or NHL between 1990 and 1998 in North America and were in continuous complete remission (CR) for at least 2 years after transplantation.

Patients were selected from the Research database if they had received a first transplant for lymphoma and achieved or maintained a CR following the transplantation. Patients who died or who had persistent or recurrent malignancy within 24 months of their transplant date were eliminated from the dataset. A completeness index of follow-up data was computed for each team with potentially eligible patients.(Clark, et al 2002) Additionally, the proportion of patients with follow-up less than 24 months and no reported events (relapse or death) was calculated. Some transplant teams follow recipients of autologous transplantation long-term less diligently, particularly beyond 1-year after the procedure. In order to avoid potential bias from teams with incomplete follow-up and, consequently, incomplete ascertainment of events in the late post-transplant period, the final dataset included patients from teams where the number of patients evaluated at 5 years or later was greater than 50% of the patients alive and disease-free at 2 years after HCT.

Five thousand and fifty-two patients received a first autologous HCT for HL and NHL in the USA and Canada between 1990 and 1998. Among these, 3056 patients were excluded for failure to achieve complete remission after HCT, or death or relapse or second transplant within the first two years post-transplant. An additional 629 patients were excluded from 44 teams that did not meet the follow-up reporting criteria specified above. The final study population consisted of 1367 patients (HL=407, NHL=960) from 110 transplant centres (Table I). The median followup was 104 months (range, 25–203 months) for HL survivors and 107 months (range, 25–198 months) for NHL survivors. The followup completeness index from time of HCT, which is the ratio of total observed person-time and the potential person-time of followup in a study,(Clark, et al 2002) was 95% at 5-years and 76% at 10-years for HL and 97% at 5-years and 81% at 10-years for NHL patients.

Table I.

Patient, disease and transplant characteristics of patients surviving in remission for at least 2 years after autologous haematopoietic-cell transplant for lymphoma

| Characteristic | Hodgkin lymphoma N (%) |

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 407 | 960 |

| Number of centres | 87 | 98 |

| Median age at transplant (range), years | 31 (7–77) | 47 (4–72) |

| Age at transplant, years | ||

| <10 | 5 (1) | 6 (1) |

| 10–19 | 57 (14) | 34 (4) |

| 20–29 | 129 (32) | 78 (8) |

| 30–39 | 124 (31) | 174 (18) |

| 40–49 | 65 (16) | 287 (30) |

| 50–59 | 18 (4) | 285 (30) |

| ≥60 | 9 (2) | 96 (10) |

| Male sex | 242(59) | 583(61) |

| Race | ||

| White | 349 (86) | 844 (88) |

| Black | 33 (8) | 40 (4) |

| Other | 13 (3) | 50 (5) |

| Missing | 12 (3) | 26 (3) |

| Karnofsky score at transplant | ||

| ≥ 90 | 279 (69) | 637 (66) |

| < 90 | 118 (29) | 288 (30) |

| Missing | 10 (2) | 35 (4) |

| Histology | ||

| Follicular lymphoma | -- | 285 (30) |

| Diffuse large cell lymphoma | -- | 428 (45) |

| Lymphoblastic/Burkitt/Burkitt-like lymphoma | -- | 70 (7) |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | -- | 59 (6) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 407 (100) | -- |

| Othera | -- | 118 (12) |

| Disease stage at diagnosis | ||

| I–II | 157 (39) | 262 (27) |

| III–IV | 239 (58) | 652 (68) |

| Missing | 11 (3) | 46 (5) |

| B-Symptoms at diagnosis | ||

| Present | 210 (52) | 323 (34) |

| Absent | 180 (44) | 542 (56) |

| Missing | 17 (4) | 95 (10) |

| Chemosensitivity to last regimen | ||

| Sensitive | 319 (78) | 801 (83) |

| Resistant | 35 (9) | 81 (8) |

| Untreated | 32 (8) | 49 (5) |

| Unknown | 21 (5) | 29 (3) |

| Disease status at transplant | ||

| CR1 | 19 (5) | 176 (18) |

| CR2+ | 92 (23) | 203 (21) |

| REL1 | 174 (43) | 258 (27) |

| REL2+ | 46 (11) | 56 (6) |

| PIF | 46 (11) | 212(22) |

| Missing | 30(7) | 55 (6) |

| Median time from diagnosis to transplant (range), months | 28 (6–286) | 15 (2–362) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, months | ||

| < 12 | 38 (9) | 396 (41) |

| ≥ 12 | 368 (90) | 564 (59) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Use of total body irradiation in conditioning | ||

| Yes | 24 (6) | 340 (36) |

| No | 382 (94) | 616 (64) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 4 (<1) |

| Use of other field radiation in conditioning | ||

| Yes | 17 (4) | 27 (3) |

| No | 390 (96) | 929 (97) |

| Missing | 0 | 4 (<1) |

| Graft purging | ||

| Yes | 4 (1) | 100 (10) |

| No | 394 (97) | 836 (87) |

| Missing | 9 (2) | 24 (3) |

| Graft type | ||

| Bone marrow | 165 (41) | 300 (31) |

| Peripheral blood | 185 (45) | 587 (61) |

| Peripheral blood + bone marrow | 57 (14) | 73 (8) |

| Year of transplant | ||

| 1990–1992 | 115 (28) | 191 (20) |

| 1993–1995 | 158 (39) | 371 (39) |

| 1996–1998 | 134 (33) | 398 (42) |

| Post-transplant radiation therapy | ||

| Yes | 86 (21) | 123 (13) |

| No | 312 (77) | 796 (83) |

| Missing | 9 (2) | 41 (4) |

| GM-CSF or G-CSF to promote engraftment post- transplant |

||

| Yes | 290 (71) | 707 (74) |

| No | 108 (27) | 221 (23) |

| Missing | 9 (2) | 32 (3) |

| Median follow-up of survivors, mo (range) | 104 (25–203) | 107 (25–198) |

Abbreviations: CR – complete remission, REL – relapse, PIF – primary induction failure, GM-CSF – granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, G-CSF – granulocyte colony stimulating factor; mo – month

Other included non-Hodgkin lymphoma, not otherwise specified (N=12); small lymphocytic lymphoma (N=1); mycosis fungoides/cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (N=2); histoiocytic lymphoma (N=3); composite lymphoma (N=28); marginal zone/mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (N=3), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (N=20); primary central nervous system lymphoma (N=1); peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (N=9); angiocentric lymphoma (N=7); other T/natural killer-cell lymphoma (N=1); T-cell rich B-cell lymphoma (N=5), non-Hodgkin lymphoma, other specify (N=26)

End Points

Primary study endpoints were overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), relapse and non-relapse mortality (NRM). For analyses of OS, failure was death from any cause; surviving patients were censored at the date of last contact. DFS was survival in CR; disease relapse or progression and death from any cause were considered as events and patients surviving without disease were censored at the date of last contact. Relapse was defined as recurrence of lymphoma with death as a competing risk. NRM was defined as mortality not related to disease recurrence and relapse was the competing risk. The two competing risks relapse and NRM make up the DFS event.

Statistical Analyses

Univariate probabilities of OS and DFS were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier estimator; the log-rank test was used for univariate comparisons.(Klein and Moeschberger 2003) Probabilities of NRM and relapse were calculated by using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks. Estimates of standard error for the survival function were calculated by Greenwood’s formula and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were constructed using log-transformed intervals. The survival interval was defined as time from the date of transplant to the date of death or last contact.

Potential patient-, disease- and treatment related prognostic factors (Table II) for OS, DFS, relapse and NRM were evaluated in multivariate analyses using Cox proportional-hazards regression.(Cox 1972) Multivariate models were built using a stepwise forward selection with a significance level of 0.05. In each model, the assumption of proportional hazards was tested for each variable using a time-dependent covariate.(Klein and Moeschberger 2003) First-order interactions of significant covariates were tested.

Table II.

Variables tested in Cox-proportional hazards regression models

| Patient related variables |

| Age: <20* years vs. 20–49 years vs. ≥ 50 years |

| Gender: female* vs. male |

| Race: White* vs. Black vs. Other |

| Karnofsky performance score at transplant: <90* vs. ≥ 90 |

| Disease related variables |

| Histology: Hodgkin vs. follicular vs. diffuse large cell vs. lymphoblastic/Burkitt vs. mantle-cell vs. other |

| Stage at diagnosis: I/II* vs. III/IV |

| B-symptoms at diagnosis: present* vs. absent |

| Number of chemotherapy regimens to achieve first CR: 1* vs. 2 vs. ≥ 3 |

| Involved field radiation pre-transplant: no* vs. yes |

| Chemosensitivity pre-transplant: sensitive* vs. resistant vs. unknown vs. untreated |

| Pre transplant disease status: CR1* vs. CR2+/REL/PIF |

| Transplant related variables |

| Year of transplant: 1990–1992*, 1993–1995, 1996–1998 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant: < 12 months* vs. ≥ 12 months |

| Use of total body irradiation in conditioning regimen: no* vs. yes |

| Graft source: bone marrow* vs. peripheral blood |

| Graft purging: no* vs. yes |

| Use of GM-CSF or G-CSF to stimulate hematopoietic recovery: no* vs. yes |

| Use of radiation post-transplant: no* vs. yes |

Abbreviations: CR – complete remission, REL – relapse, PIF – primary induction failure, GM-CSF – granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, G-CSF – granulocyte colony stimulating factor

Reference group

We calculated estimates of relative mortality as described by Andersen and Vaeth (1989) taking into account differences among patients with regard to age, gender, race and nationality using population-based standard mortality tables for North America (U.S. and Canada). Relative mortality with respect to a transplant recipient is the relative risk of dying at a given time after transplantation when compared with a person of similar age and gender in the general population. Relative mortality rates with 95% CI that included 1.0 were not considered to indicate a significant difference from the rates in a normal population. Plots for relative excess mortality and their pointwise 95% CIs were constructed and were based on the kernel smoothed estimates with a band width of 2 years using the Epanechnikov kernel.(Ramlou-Hansen 1983)

A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered significantAll analyses were carried out using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient, Disease and Treatment Characteristics

The demographic and transplant characteristics of the 1067 patients are detailed in Table I. Patients were predominantly White (87%), male (60%), with chemosensitive disease (82%), and had a Karnofsky performance score of ≥ 90 (67%) before transplantation. A greater proportion of HL patients were <40 years in age (78% vs. 30%), had history of B symptoms (52% vs. 34%) and were ≥12 months from diagnosis (90% vs. 59%) while use of total body irradiation (TBI) was more prevalent for NHL (94% vs. 64%) patients. Among NHL, diffuse large cell NHL (45%) and follicular NHL (30%) were the most common histologies. The use of TBI did not change substantially over time; e.g., TBI was used in 69% of patients transplanted in 1990–91 compared to 83% in 1997–98. TBI was commonly used as part of conditioning in patients with follicular NHL (49%), mantle-cell NHL (49%) and lymphoblastic/Burkitt/Burkitt-like NHL (44%) as compared to other NHL (32%), diffuse large cell NHL (25%) and HL (7%). The use of hematopoietic growth factors did not differ by histology, but as expected, did increase with time (28% in 1990–91 vs. 88% in 1997–98). Time between diagnosis and HCT differed by histology; it was ≥12 months in 90% of patients with HL, 76% in follicular NHL, 59% in other NHL, 55% in diffuse large cell NHL, 37% in mantle cell NHL and 28% in lymphoblastic/Burkitt/Burkitt-like NHL.

Disease status at transplantation varied by lymphoma histology. The majority of HL patients were in first relapse (43%) or second CR (15%). Disease status at transplant for patients with diffuse large cell NHL included first relapse (30%), first CR (18%) or second CR (17%). Transplant was performed in first CR or first relapse frequently among patients with lymphoblastic/Burkitt/Burkitt like NHL (51% and 13%) and mantle-cell NHL (31% and 15%).

Univariate Analyses

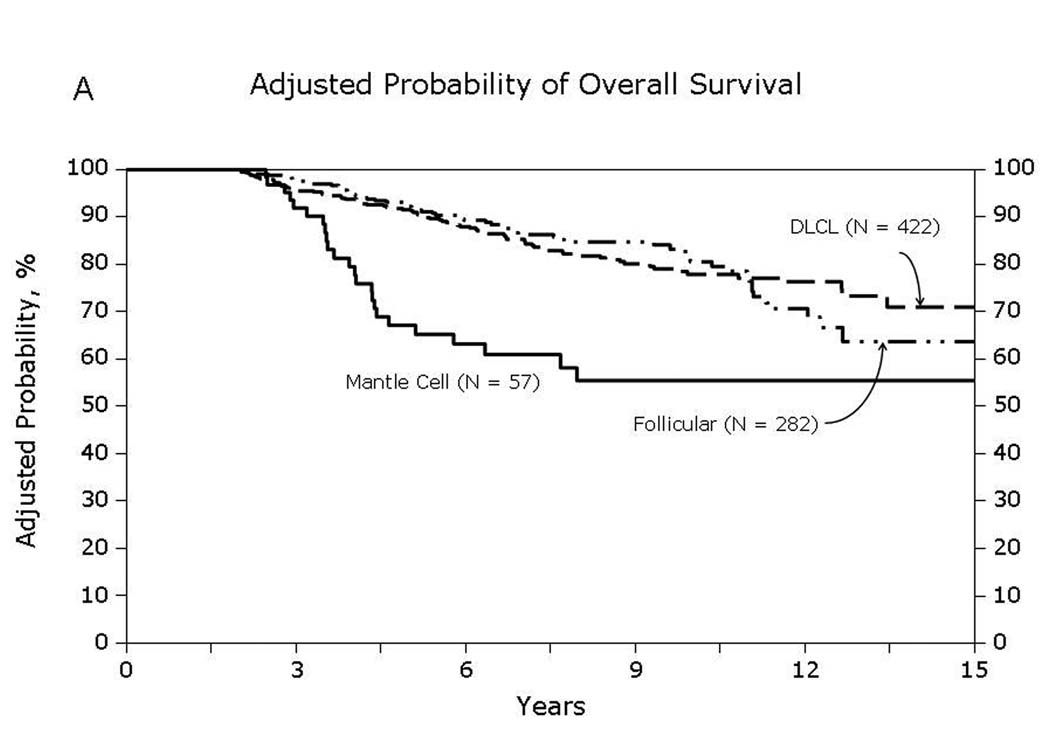

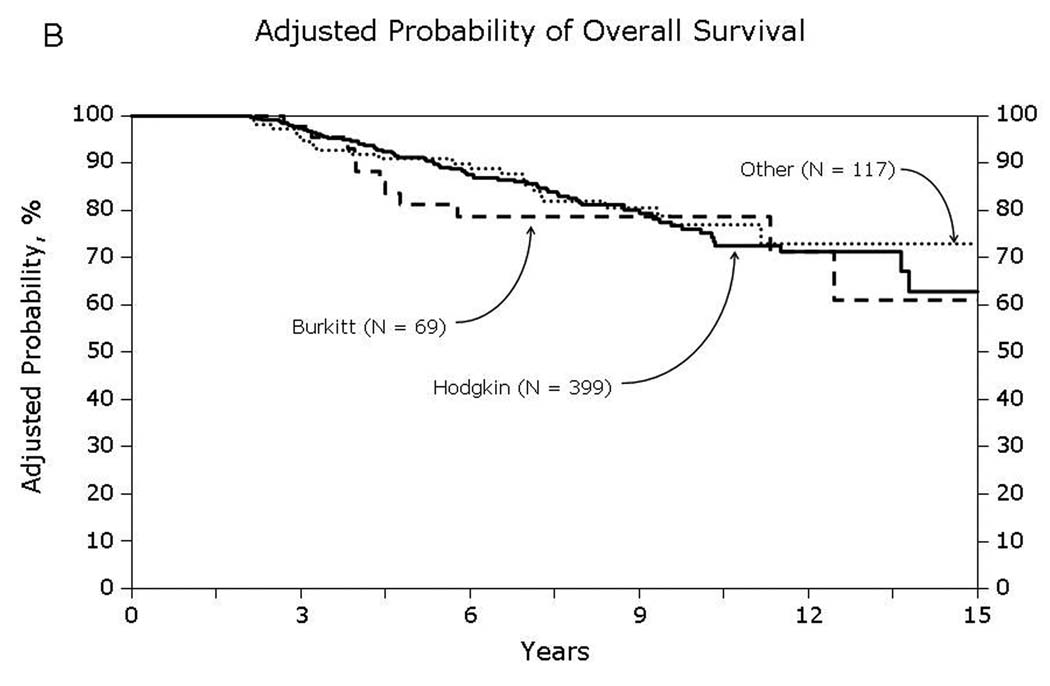

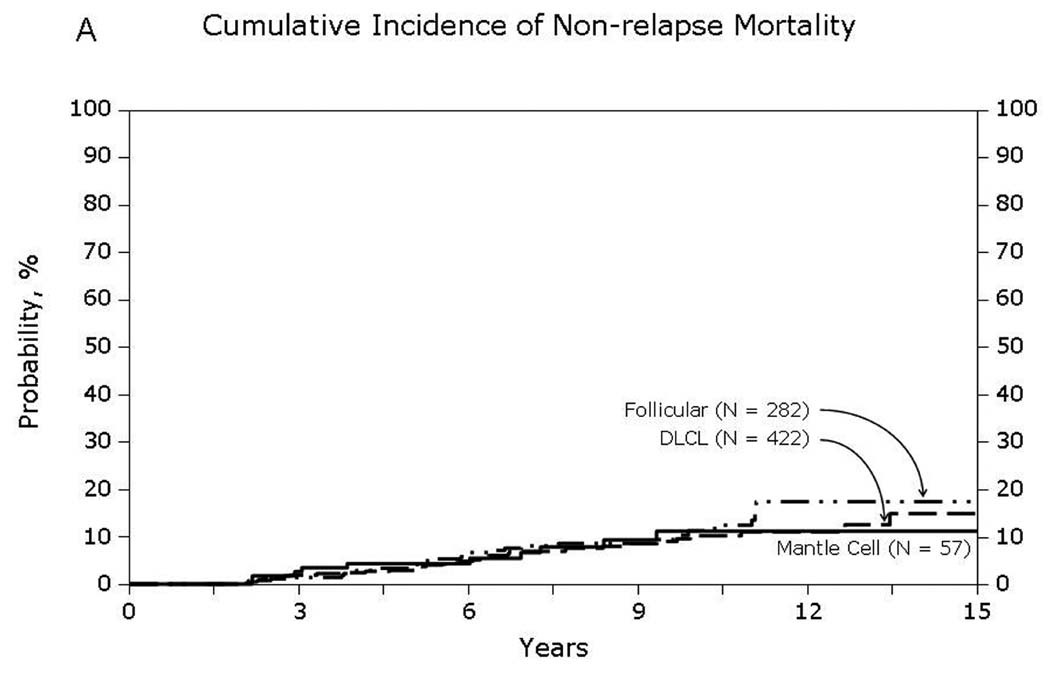

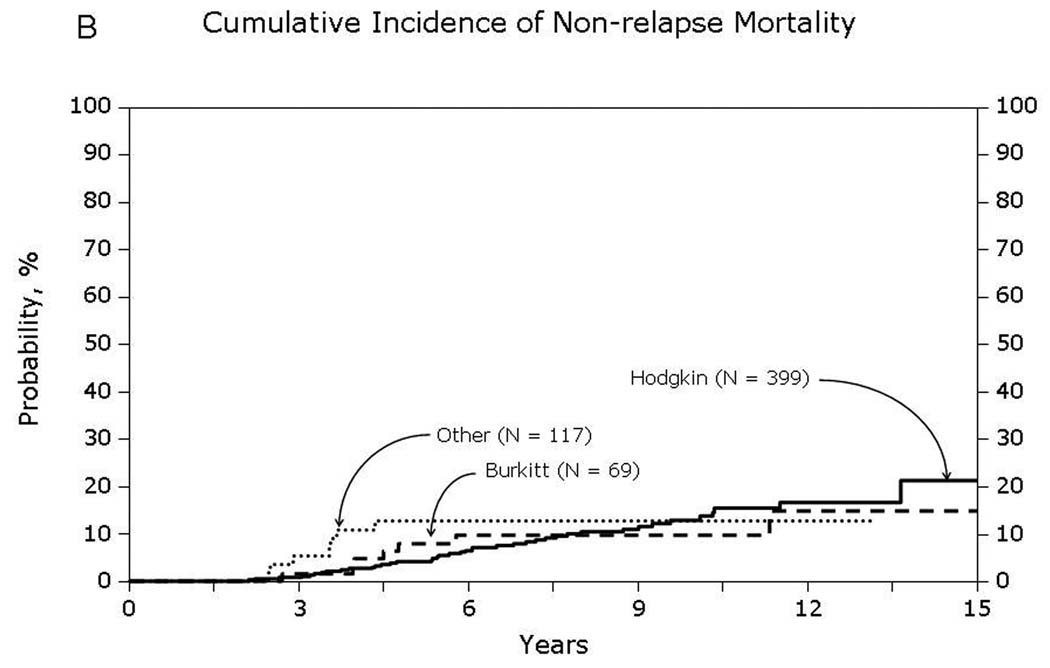

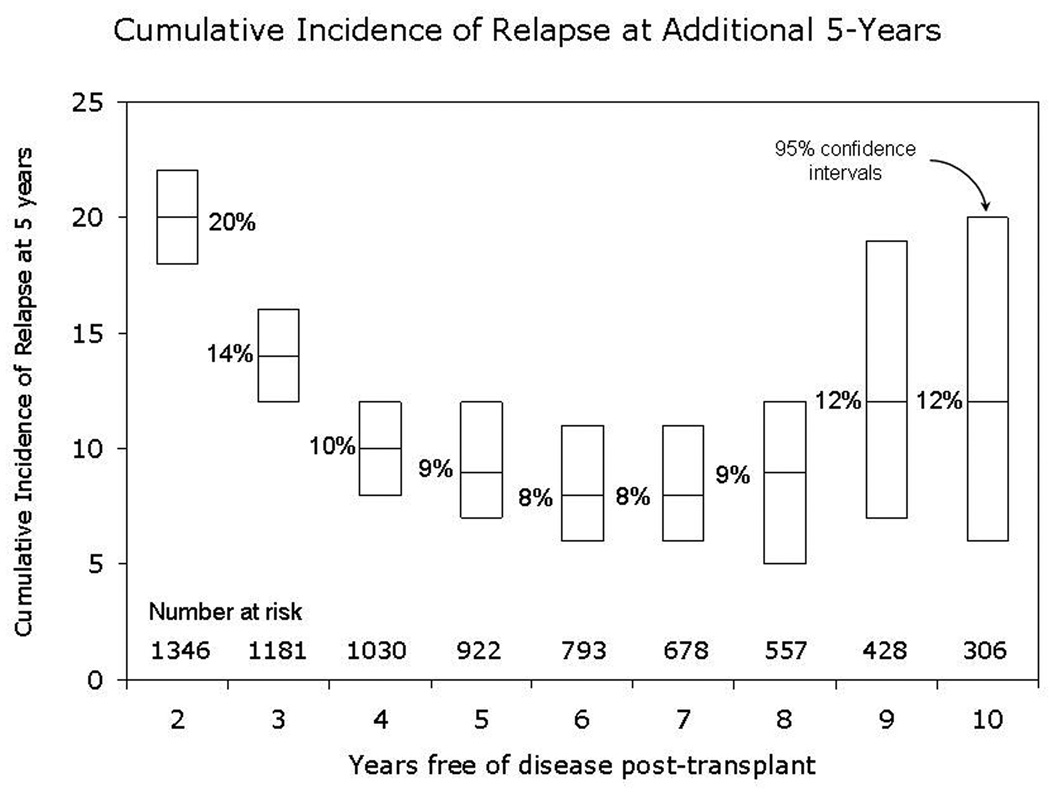

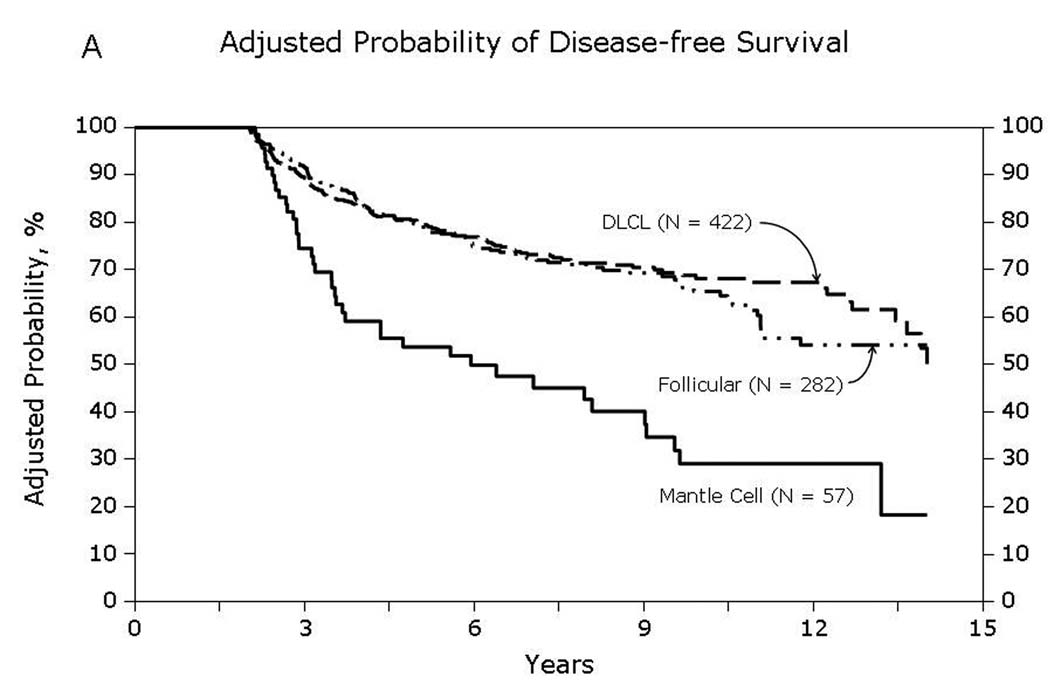

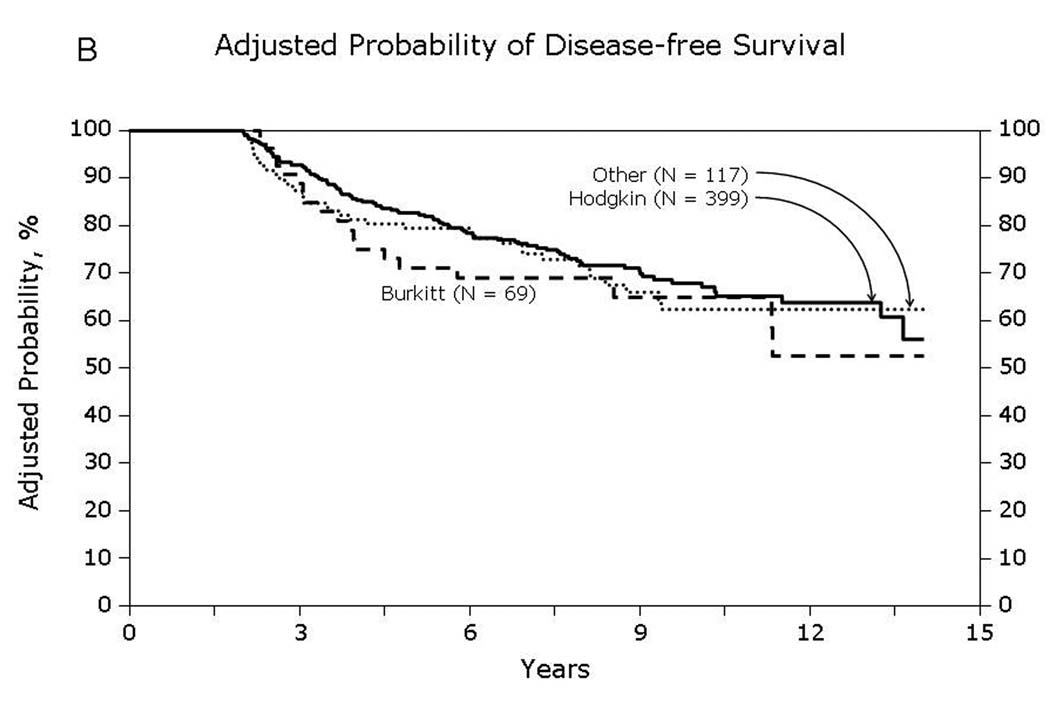

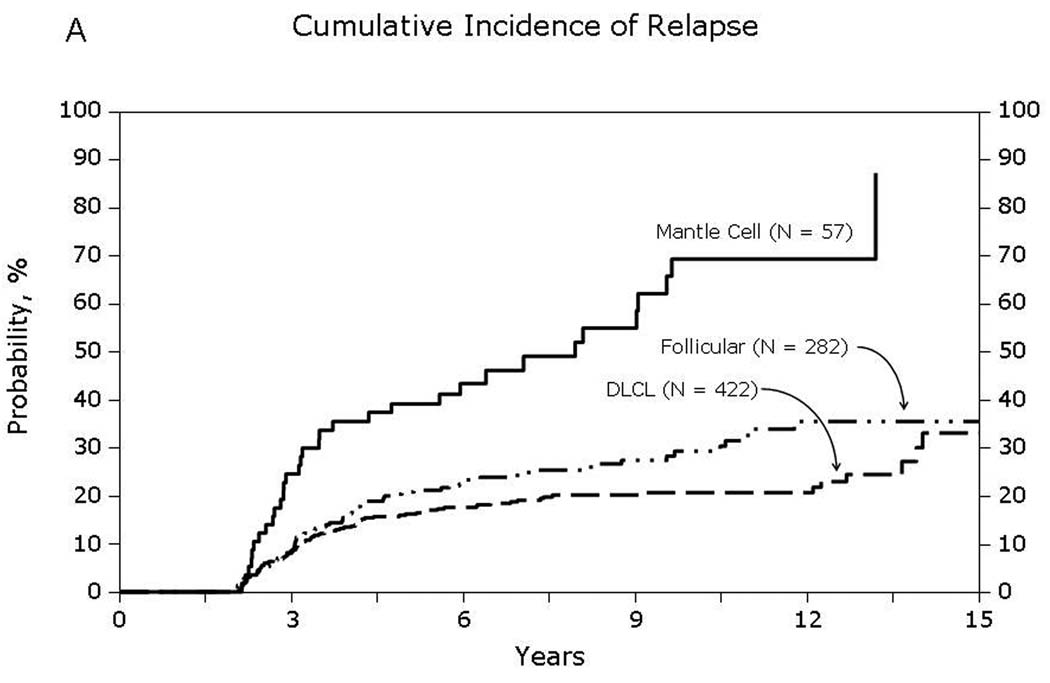

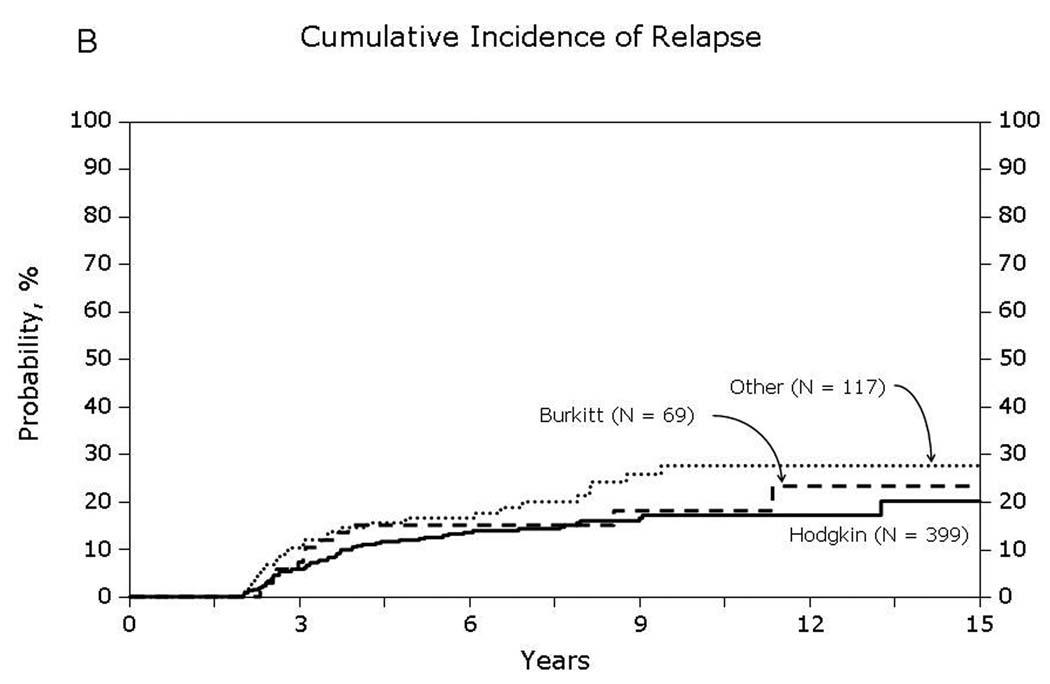

Univariate probabilities of OS and DFS and cumulative incidences of relapse and NRM are described by histology in Table III (Fig 1–Fig 4). Recipients of autologous HCT for mantle-cell NHL had the highest rates of late mortality and late relapse. The cumulative incidence of NRM was comparable between HL and different NHL histologies. The risk of relapse was highest among 2-year survivors, then decreased over the next 2–3 years post-transplant and subsequently remained stable over time (Fig 5).

Table III.

Univariate probabilities for transplant outcomes of patients surviving in remission for at least 2 years after autologous transplant for lymphoma; survival was estimated from the date of transplant to the date of death or last contact

| Outcome | Hodgkin lymphoma % (95% CI) |

Follicular lymphoma % (95% CI) |

Diffuse large-cell lymphoma % (95% CI) |

Lymphoblastic/ Burkitt lymphoma % (95% CI) |

Mantle cell lymphoma % (95% CI) |

Other % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||||

| N | 407 | 285 | 428 | 70 | 59 | 118 |

| 5 years | 92 (89–95) | 90 (87–94) | 92 (89–94) | 87 (78–94) | 66 (53–78) | 91 (85–96) |

| 10 years | 77 (72–82) | 77 (71–83) | 78 (73–82) | 85 (75–93) | 52 (37–67) | 77 (67–85) |

| Disease-free survival | ||||||

| N | 401 | 282 | 425 | 70 | 57 | 117 |

| 5 years | 84 (80–88) | 75 (70–80) | 81 (77–85) | 77 (67–87) | 48 (35–61) | 79 (71–86) |

| 10 years | 70 (65–75) | 59 (52–66) | 69 (64–74) | 73 (60–83) | 18 (7–33) | 61 (51–71) |

| Relapse | ||||||

| N | 401 | 282 | 425 | 70 | 57 | 117 |

| 5 years | 12 (9–15) | 21 (16–26) | 16 (13–20) | 15 (7–24) | 39 (27–52) | 17 (10–24) |

| 10 years | 17 (13–22) | 29 (23–36) | 21 (17–25) | 18 (9–29) | 69 (54–83) | 28 (19–37) |

| Non-relapse mortality | ||||||

| N | 401 | 282 | 425 | 70 | 57 | 117 |

| 5 years | 4 (2–6) | 4 (2–7) | 3 (1–5) | 8 (3–15) | 13 (5–23) | 4 (1–9) |

| 10 years | 13 (9–17) | 11 (7–16) | 10 (7–14) | 10 (4–18) | 13 (5–23) | 11 (5–19) |

Fig 1.

Overall survival of patients surviving in remission for at least 2-years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant for lymphoma: (A) Diffuse large cell, follicular and mantle cell lymphomas (B) Burkitt, Hodgkin and other lymphomas

Fig 4.

Non-relapse mortality among patients surviving in remission for at least 2-years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant for lymphoma: (A) Diffuse large cell, follicular and mantle cell lymphomas (B) Burkitt, Hodgkin and other lymphomas

Fig 5.

Cumulative incidence of relapse at additional 5-years for patients surviving in remission for at least 2-years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant. The x-axis denotes the number of years in complete remission post-transplant. The line within each box indicates the cumulative incidence of relapse over the next 5-years of followup and the ends represent 95% confidence intervals.

Multivariate Analyses

Results of multivariate analyses for OS, DFS, relapse and NRM are detailed in Table IV. Mantle-cell histology was associated with significantly higher risks of death, relapse and treatment failure; these risks were comparable for other lymphoma types. HL and all NHL histologies, including mantle-cell NHL, had similar risks for NRM. Older age at HCT (≥50 years) was associated with decreased OS and DFS and higher NRM, but did not impact relapse. Time from diagnosis to HCT of ≥12 months was independently predictive of adverse OS, DFS, relapse and NRM. Other factors that were associated with poor DFS and increased relapse risk but did not influence OS or NRM, included male gender, Karnofsky performance status score of <90 at transplant, use of TBI in conditioning and use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). We tested for, but found no significant interactions between histology and age, use of TBI, use of hematopoietic growth factors, disease status or time from diagnosis to transplant.

Table IV.

Multivariate outcomes of patients surviving in remission for at least 2 years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant for lymphoma

| Outcomes and variables | N | RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | |||

| Lymphoma histology | 0.001a | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 399 | 1.00 | |

| Follicular lymphoma | 282 | 0.91 (0.63–1.32) | 0.61 |

| Diffuse large cell lymphoma | 422 | 0.92 (0.64–1.31) | 0.63 |

| Lymphoblastic/Burkitt lymphoma | 69 | 1.28 (0.66–2.48) | 0.47 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 57 | 2.87 (1.70–4.87) | <0.001 |

| Other | 117 | 0.95 (0.58–1.57) | 0.85 |

| Age at transplant | <0.001a | ||

| <20 years | 101 | 1.00 | |

| 20–49 years | 843 | 0.94 (0.54–1.66) | 0.84 |

| ≥50 years | 402 | 2.23 (1.24–4.00) | 0.008 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | |||

| <12 months | 426 | 1.00 | |

| ≥12 months | 920 | 2.23 (1.62–3.09) | <0.001 |

| Disease-free survival | |||

| Lymphoma histology | <0.001a | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 399 | 1.00 | |

| Follicular lymphoma | 282 | 1.16 (0.84–1.59) | 0.36 |

| Diffuse large cell lymphoma | 422 | 1.05 (0.79–1.41) | 0.72 |

| Lymphoblastic/Burkitt lymphoma | 69 | 1.36 (0.81–2.30) | 0.24 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 57 | 3.23 (2.09–5.00) | <0.001 |

| Other | 117 | 1.14 (0.77–1.70) | 0.52 |

| Age at transplant | <0.001a | ||

| <20 years | 101 | 1.00 | |

| 20–49 years | 843 | 0.95 (0.61–1.46) | 0.80 |

| ≥50 years | 402 | 1.60 (1.02–2.53) | 0.04 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 533 | 1.00 | |

| Male | 813 | 1.23 (1.01–1.50) | 0.04 |

| Karnofsky score at transplant | |||

| <90 | 402 | 1.00 | |

| ≥90 | 901 | 0.78 (0.64–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Use of total body irradiation | |||

| No | 986 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 360 | 1.49 (1.20–1.85) | 0.003 |

| GM-CSF/G-CSF to promote engraftment | |||

| No | 324 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 983 | 1.33 (1.05–1.69) | 0.02 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | |||

| <12 months | 426 | 1.00 | |

| ≥12 months | 920 | 1.96 (1.53–2.51) | <0.001 |

| Non-relapse mortality | |||

| Lymphoma histology | 0.21a | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 399 | 1.00 | |

| Follicular lymphoma | 282 | 0.75 (0.45–1.27) | 0.29 |

| Diffuse large cell lymphoma | 422 | 0.65 (0.40–1.07) | 0.09 |

| Lymphoblastic/Burkitt lymphoma | 69 | 1.26 (0.54–2.94) | 0.60 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 57 | 1.50 (0.62–3.62) | 0.37 |

| Other | 117 | 0.75 (0.37–1.54) | 0.43 |

| Age at transplant | <0.001a | ||

| <20 years | 101 | 1.00 | |

| 20–49 years | 843 | 0.96 (0.46–2.03) | 0.84 |

| ≥50 years | 402 | 2.55 (1.16–5.61) | 0.03 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | |||

| <12 months | 426 | 1.00 | |

| ≥12 months | 920 | 2.07 (1.30–3.30) | 0.002 |

| Relapse | |||

| Lymphoma histology | <0.001a | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 399 | 1.00 | |

| Follicular lymphoma | 282 | 1.47 (1.00–2.17) | 0.05 |

| Diffuse large cell lymphoma | 422 | 1.35 (0.94–1.93) | 0.11 |

| Lymphoblastic/Burkitt lymphoma | 69 | 1.44 (0.75–2.78) | 0.28 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 57 | 4.59 (2.76–7.64) | <0.001 |

| Other | 117 | 1.46 (0.90–2.35) | 0.12 |

| Age | 0.03a | ||

| <20 years | 101 | 1.00 | |

| 20–49 years | 843 | 0.94 (0.55–1.59) | 0.80 |

| ≥50 years | 402 | 1.33 (0.76–2.32) | 0.32 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 533 | 1.00 | |

| Male | 813 | 1.27 (1.00–1.62) | 0.05 |

| Karnofsky score at transplant | |||

| <90 | 402 | 1.00 | |

| ≥90 | 901 | 0.76 (0.59–0.97) | 0.03 |

| Use of total body irradiation | |||

| No | 986 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 360 | 1.59 (1.23–2.05) | <0.001 |

| GM-CSF/G-CSF to promote engraftment | |||

| No | 324 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 983 | 1.45 (1.07–1.95) | 0.02 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | |||

| <12 months | 426 | 1.00 | |

| ≥12 months | 920 | 1.91 (1.46–2.56) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: GM-CSF – granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, G-CSF – granulocyte colony stimulating factor

Multiple degree of freedom test for equality over categories

Causes of Death

Table V describes the causes of death by histology. For the whole cohort, the most common cause of mortality was recurrence or progression of primary lymphoma (40%). This was followed by other causes (e.g., accidental death, hemorrhage, other cause not specified; 18%), second malignancies (12%) and organ failure (8%).

Table V.

Causes of death of patients surviving in remission for at least 2 years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant for lymphoma

| Hodgkin Lymphoma |

Follicular Lymphoma |

Diffuse large-cell lymphoma |

Lymphoblastic/ Burkitt Lymphoma |

Mantle cell lymphoma |

Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of death | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Disease recurrence | 25 (36) | 19 (31) | 33 (40) | 4 (36) | 15 (63) | 11 (50) |

| Secondary malignancy | 6 (9) | 8 (13) | 10 (12) | 2 (18) | 5 (21) | 1 (5) |

| Organ failure | 5 (7) | 10 (16) | 4 (5) | 0 | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Infection | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Other cause | 16 (23) | 12 (20) | 13 (16) | 1 (9) | 2 (8) | 4 (18) |

| Unknown | 15 (21) | 10 (16) | 19 (23) | 4 (36) | 2 (8) | 2 (9) |

Relative Mortality

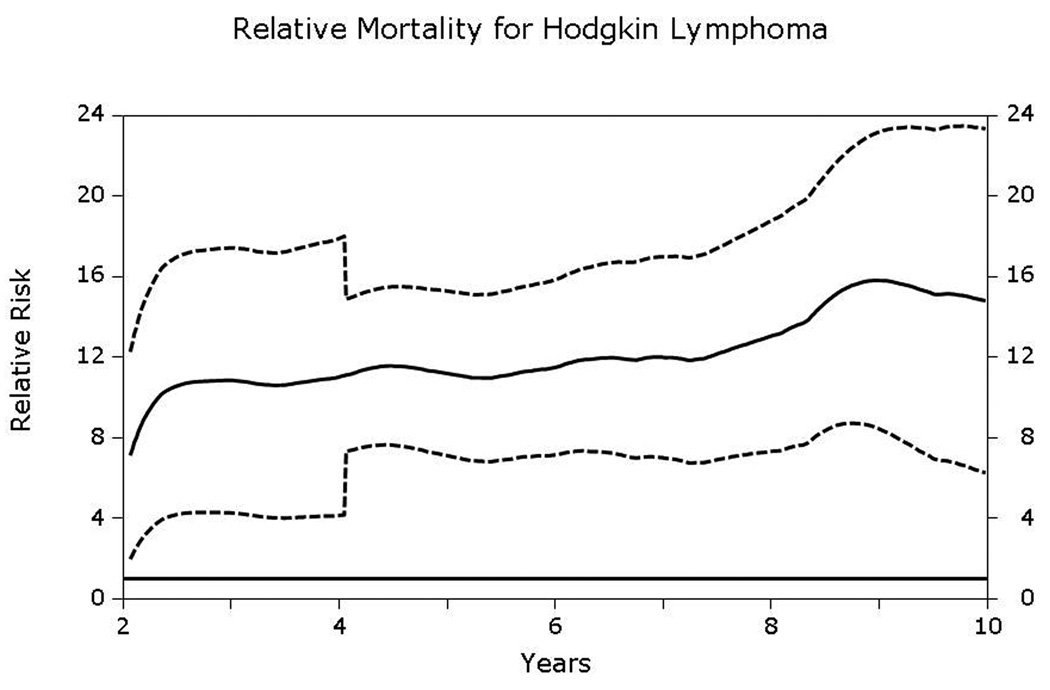

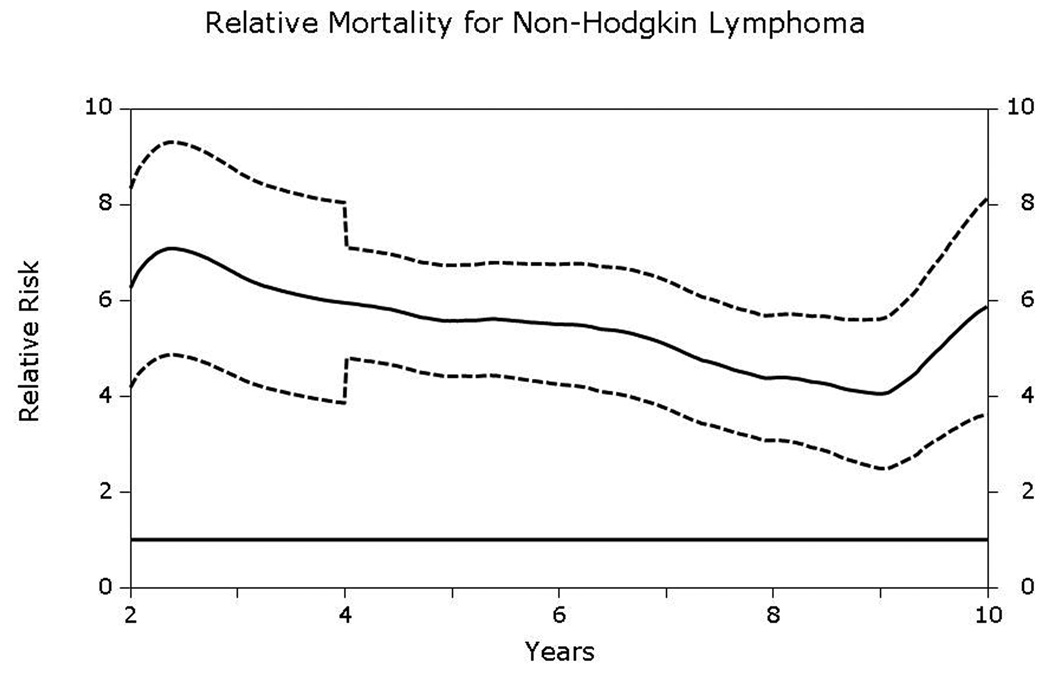

Compared to age- and gender- matched general population, both HL and NHL patients had significantly elevated relative mortality that did not approach that of the general population up to at least 10-years post-transplantation (Figs 6A and 6B). Relative mortality for HL patients was 11.1 (95% CI, 7.3–15.2) at 5-years and 14.8 (6.3–23.3) at 10-years post-HCT. Corresponding relative mortality rates for NHL patients were 5.6 (4.4–6.7) and 5.9 (3.6–8.2), respectively.

Fig 6.

A & B. Relative excess mortality (solid line) compared to age-, gender- and race- matched general population for patients surviving in remission for at least 2-years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant for (A) Hodgkin lymphoma and (B) non-Hodgkin lymphoma. A relative risk of 1 indicates that the mortality rate of the population of interest is similar to that of the general population. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals. The P-value testing the hypothesis that the relative mortality is greater than 1 was <0.05.

Discussion

Several observational studies and clinical trials have reported long-term outcomes of autologous HCT for HL and NHL.(Bolwell, et al 2002, Haioun, et al 1997, Lazarus, et al 2001, Lazarus, et al 1999, Linch, et al 1993, Majhail, et al 2006, Philip, et al 1995, Sweetenham, et al 1999, van Besien, et al 1995, Vose, et al 2004, Vose, et al 2001, Wadehra, et al 2006) Overall, 40–60% of recipients treated with autologous HCT can be expected to be alive at 5-years from the time of transplantation. Relapse or progression of primary lymphoma is the most common cause of treatment failure and predominantly occurs in the first 2 years post-transplant. Long-term outcomes of patients who survive in remission for at least 2-years and risk-factors for late relapse are not well known. Our study of a large cohort of patients with HL and NHL with an extended period of follow-up shows that patients with histologies other than mantle-cell NHL, who survive for at least 2-years in remission after an autologous HCT have favorable outcomes with 10-year post-transplant survival rates of 77–85%.

Bolwell et al (2002) described outcomes in patients who survived in remission for 2-years or more after autologous HCT for NHL. Among 110 recipients, 50 and 39 patients were alive and disease-free at 2-years and 5-years post-transplant, respectively. Among the 2-year survivors, 100% with high-grade NHL were disease-free at 10 years post-transplant compared to 82% with intermediate-grade and 62% with low-grade histologies. All patients who were alive and disease-free at 5-years were still in remission at 10-years post-transplant. Other studies with small numbers of patients have also reported the absence of late relapses among HL and NHL autologous HCT recipients.(van Besien, et al 1995, Wadehra, et al 2006) In contrast, in our comparatively large cohort of patients, we observed a small but continued risk of relapse over time, even in histologies other than mantle-cell NHL. Although the risk of relapse was highest among patients who had survived in remission for 2–5 years post-transplant, a stable continued risk was observed in patients who had survived disease-free up until 10-years. Our study could not address the optimal method for monitoring relapse. Further studies are warranted to determine efficacious, safe and cost-effective approaches to long-term surveillance (e.g. clinical examination vs. radiological imaging). For instance, computed tomography scans are frequently used for following patients with lymphoma after completion of therapy. However, cumulative radiation exposure from computed tomography scans has been reported to increase the risk of radiation-induced cancer.(Huang, et al 2009, Sodickson, et al 2009)

Mantle-cell histology was the most important risk factor for adverse OS and DFS and late relapse. Other studies have also demonstrated that autologous HCT may extend DFS with or without improvement in OS among patients with mantle-cell NHL, but the vast majority of patients eventually relapse.(Andersen, et al 2003, Dreyling, et al 2005, Freedman, et al 1998, Vandenberghe, et al 2003) Recent advances in the treatment of mantle-cell lymphoma may improve outcomes of autologous HCT. The use of intensive chemotherapy to achieve maximal remission prior to autologous HCT and the use of rituximab and radio-immunotherapy with transplant conditioning have shown promising results, although long-term follow-up and more investigation is needed to determine if these strategies lead to durable remissions.(Geisler, et al 2008, Gopal, et al 2002, Khouri, et al 1998) As expected, we observed relatively low rates of relapse in patients with HL and high-grade NHL. Interestingly, patients with follicular NHL had relapse rates of 21% at 5 years and 29% at 10 years, indicating that selected patients can achieve very long-term remissions after autologous transplantation. Other studies have also reported extended remission after autologous HCT for follicular NHL,(Freedman, et al 1999, Gopal, et al 2003, Gyan, et al 2009, Sebban, et al 2008) but more trials are still needed to better define a specific subset of patients who might benefit most from this approach.

The negative effect of hematopoietic growth-factors used to promote engraftment following autologous HCT for lymphoma is intriguing and has been previously reported.(Vose, et al 2004) In a study that included 429 autologous HCT recipients for diffuse aggressive NHL in first relapse or second remission, Vose et al (2004) reported that patients receiving G-CSF or GM-CSF to promote engraftment had a higher risk of relapse or disease progression (compared to bone marrow without growth factors, the relative risk for relapse was 2.46 (1.68–3.40) for bone marrow with growth factors, 1.15 (0.72–1.83) for peripheral blood without growth factors and 1.25 (0.90–1.74) for peripheral blood with growth factors). However, randomized clinical trials, although not powered to detect such differences, showed similar relapse rates between patients who received and did not receive hematopoietic growth factors following autologous HCT for lymphoma.(Gorin, et al 1992, Rabinowe, et al 1993) The adverse effect of growth factors on relapse could be secondary to patient selection factors that were not accounted for in this analysis, but may warrant further investigation in future studies.

At 10-years post-HCT, mortality rates for our cohort did not approach that of the general population. Bhatia et al (2005) reported late mortality in survivors of autologous HCT in an analysis from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study that included 245 patients with HL and 392 patients with NHL who had survived for 2-years or more following HCT. The standardized mortality ratio (SMR) was 28.2 (95% CI, 22.6–34.3) for HL and 9.6 (7.9–11.5) for NHL. Similar to our study, the risk of excess relative mortality remained elevated until at least 10-years after autologous transplantation. However, these risks subsequently decreased in >10-year survivors to approach that of the general population. The SMR was 10.2 (5.7–16.0) and 1.9 (0.2–5.5) for HL survivors who were 6–10 years and >10 years post-HCT, respectively. Likewise, the corresponding SMR for NHL patients were 3.9 (2.5–5.6) and 1.6 (0.4–3.6), respectively. A major limitation of our study and Bhatia et al (2005) is the relatively small number of patients with followup >10-years. Studies including an adequate number of very long-term survivors are still needed to understand the risks and impact of late mortality following autologous HCT for HL and NHL.

With contemporary transplant techniques and supportive care practices, early non-relapse mortality after autologous HCT for lymphoma can be expected to be less than 5%.(Geisler, et al 2008, Majhail, et al 2006, Wadehra, et al 2006) For our cohort of patients who had survived in remission for 2 years, we observed relatively high rates of late non-relapse mortality (10–13% at 10-years post-transplant). Second malignancies and organ failure were among the major causes of late non-relapse deaths. Other studies have reported high rates of second cancers and late-complications after autologous HCT for HL and NHL.(Bhatia, et al 2005, Majhail, et al 2007, Ng and Travis 2008) This underscores the need for long-term follow-up of HL and NHL patients who receive an autologous HCT with a special emphasis on screening and prevention of late-effects of transplantation.

Albeit the limitations of a retrospective cohort design, our study highlights the favourable long-term survival among high-risk HL and NHL patients who receive an autologous HCT and survive in remission for at least 2 years. However, late recurrence or progression of primary lymphoma is still the leading cause of late mortality, especially among patients with mantle cell NHL. Our study could not address optimal strategies for long-term surveillance (e.g. clinical examination vs. imaging studies) and future studies focusing on the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of various methods are needed. The risk for non-relapse mortality in these long-term survivors is also relatively high and screening and prevention of late complications should be an integral component of their health care plan.

Fig 2.

Disease-free survival of patients surviving in remission for at least 2-years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant for lymphoma: (A) Diffuse large cell, follicular and mantle cell lymphomas (B) Burkitt, Hodgkin and other lymphomas

Fig 3.

Relapse among patients surviving in remission for at least 2-years after autologous hematopoietic-cell transplant for lymphoma: (A) Diffuse large cell, follicular and mantle cell lymphomas (B) Burkitt’ Hodgkin and other lymphomas

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U01HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH234200637015C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-06-1-0704 and N00014-08-1-0058 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from AABB; Aetna; American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada; Astellas Pharma US, Inc.; Baxter International, Inc.; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; BloodCenter of Wisconsin; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Bone Marrow Foundation; Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group; Celgene Corporation; CellGenix, GmbH; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ClinImmune Labs; CTI Clinical Trial and Consulting Services; Cubist Pharmaceuticals; Cylex Inc.; CytoTherm; DOR BioPharma, Inc.; Dynal Biotech, an Invitrogen Company; Enzon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; Gambro BCT, Inc.; Gamida Cell, Ltd.; Genzyme Corporation; Histogenetics, Inc.; HKS Medical Information Systems; Hospira, Inc.; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Kiadis Pharma; Kirin Brewery Co., Ltd.; Merck & Company; The Medical College of Wisconsin; MGI Pharma, Inc.; Michigan Community Blood Centers; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Miller Pharmacal Group; Milliman USA, Inc.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Nature Publishing Group; New York Blood Center; Novartis Oncology; Oncology Nursing Society; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.; Pall Life Sciences; PDL BioPharma, Inc; Pfizer Inc; Pharmion Corporation; Saladax Biomedical, Inc.; Schering Plough Corporation; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; StemCyte, Inc.; StemSoft Software, Inc.; Sysmex; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; The Marrow Foundation; THERAKOS, Inc.; Vidacare Corporation; Vion Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; ViraCor Laboratories; ViroPharma, Inc.; and Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

References

- Andersen NS, Pedersen L, Elonen E, Johnson A, Kolstad A, Franssila K, Langholm R, Ralfkiaer E, Akerman M, Eriksson M, Kuittinen O, Geisler CH. Primary treatment with autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: outcome related to remission pretransplant. Eur J Haematol. 2003;71:73–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen PK, Vaeth M. Simple parametric and nonparametric models for excess and relative mortality. Biometrics. 1989;45:523–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S, Robison LL, Francisco L, Carter A, Liu Y, Grant M, Baker KS, Fung H, Gurney JG, McGlave PB, Nademanee A, Ramsay NK, Stein A, Weisdorf DJ, Forman SJ. Late mortality in survivors of autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2005;105:4215–4222. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell B, Kalaycio M, Sobecks R, Andresen S, McBee M, Kuczkowski L, Rybicki L, Pohlman B. Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: 100 month follow-up. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:673–679. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002;359:1309–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyling M, Lenz G, Hoster E, Van Hoof A, Gisselbrecht C, Schmits R, Metzner B, Truemper L, Reiser M, Steinhauer H, Boiron JM, Boogaerts MA, Aldaoud A, Silingardi V, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hasford J, Parwaresch R, Unterhalt M, Hiddemann W. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progression-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the European MCL Network. Blood. 2005;105:2677–2684. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman AS, Neuberg D, Gribben JG, Mauch P, Soiffer RJ, Fisher DC, Anderson KC, Andersen N, Schlossman R, Kroon M, Ritz J, Aster J, Nadler LM. High-dose chemoradiotherapy and anti-B-cell monoclonal antibody-purged autologous bone marrow transplantation in mantle-cell lymphoma: no evidence for long-term remission. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:13–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman AS, Neuberg D, Mauch P, Soiffer RJ, Anderson KC, Fisher DC, Schlossman R, Alyea EP, Takvorian T, Jallow H, Kuhlman C, Ritz J, Nadler LM, Gribben JG. Long-term follow-up of autologous bone marrow transplantation in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:3325–3333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, Andersen NS, Pedersen LB, Jerkeman M, Eriksson M, Nordstrom M, Kimby E, Boesen AM, Kuittinen O, Lauritzsen GF, Nilsson-Ehle H, Ralfkiaer E, Akerman M, Ehinger M, Sundstrom C, Langholm R, Delabie J, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Brown P, Elonen E. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112:2687–2693. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal AK, Gooley TA, Maloney DG, Petersdorf SH, Eary JF, Rajendran JG, Bush SA, Durack LD, Golden J, Martin PJ, Matthews DC, Appelbaum FR, Bernstein ID, Press OW. High-dose radioimmunotherapy versus conventional high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a multivariable cohort analysis. Blood. 2003;102:2351–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal AK, Rajendran JG, Petersdorf SH, Maloney DG, Eary JF, Wood BL, Gooley TA, Bush SA, Durack LD, Martin PJ, Matthews DC, Appelbaum FR, Bernstein ID, Press OW. High-dose chemo-radioimmunotherapy with autologous stem cell support for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:3158–3162. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin NC, Coiffier B, Hayat M, Fouillard L, Kuentz M, Flesch M, Colombat P, Boivin P, Slavin S, Philip T. Recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation with unpurged and purged marrow in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Blood. 1992;80:1149–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyan E, Foussard C, Bertrand P, Michenet P, Le Gouill S, Berthou C, Maisonneuve H, Delwail V, Gressin R, Quittet P, Vilque JP, Desablens B, Jaubert J, Ramee JF, Arakelyan N, Thyss A, Molucon-Chabrot C, Delepine R, Milpied N, Colombat P, Deconinck E. High-dose therapy followed by autologous purged stem cell transplantation and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma: a randomized multicenter study by the GOELAMS with final results after a median follow-up of 9 years. Blood. 2009;113:995–1001. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haioun C, Lepage E, Gisselbrecht C, Bastion Y, Coiffier B, Brice P, Bosly A, Dupriez B, Nouvel C, Tilly H, Lederlin P, Biron P, Briere J, Gaulard P, Reyes F. Benefit of autologous bone marrow transplantation over sequential chemotherapy in poor-risk aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: updated results of the prospective study LNH87-2. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1131–1137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Law MW, Khong PL. Whole-body PET/CT scanning: estimation of radiation dose and cancer risk. Radiology. 2009;251:166–174. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511081300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khouri IF, Romaguera J, Kantarjian H, Palmer JL, Pugh WC, Korbling M, Hagemeister F, Samuels B, Rodriguez A, Giralt S, Younes A, Przepiorka D, Claxton D, Cabanillas F, Champlin R. Hyper-CVAD and high-dose methotrexate/cytarabine followed by stem-cell transplantation: an active regimen for aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3803–3809. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J, Moeschberger M. Survival analysis: Techniques of censored and truncated data. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus HM, Rowlings PA, Zhang MJ, Vose JM, Armitage JO, Bierman PJ, Gajewski JL, Gale RP, Keating A, Klein JP, Miller CB, Phillips GL, Reece DE, Sobocinski KA, van Besien K, Horowitz MM. Autotransplants for Hodgkin's disease in patients never achieving remission: a report from the Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:534–545. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus HM, Loberiza FR, Jr, Zhang MJ, Armitage JO, Ballen KK, Bashey A, Bolwell BJ, Burns LJ, Freytes CO, Gale RP, Gibson J, Herzig RH, LeMaistre CF, Marks D, Mason J, Miller AM, Milone GA, Pavlovsky S, Reece DE, Rizzo JD, van Besien K, Vose JM, Horowitz MM. Autotransplants for Hodgkin's disease in first relapse or second remission: a report from the autologous blood and marrow transplant registry (ABMTR) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:387–396. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linch DC, Winfield D, Goldstone AH, Moir D, Hancock B, McMillan A, Chopra R, Milligan D, Hudson GV. Dose intensification with autologous bone-marrow transplantation in relapsed and resistant Hodgkin's disease: results of a BNLI randomized trial. Lancet. 1993;341:1051–1054. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92411-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majhail NS, Weisdorf DJ, Defor TE, Miller JS, McGlave PB, Slungaard A, Arora M, Ramsay NK, Orchard PJ, MacMillan ML, Burns LJ. Long-term results of autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory or relapsed Hodgkin's lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majhail NS, Ness KK, Burns LJ, Sun CL, Carter A, Francisco L, Forman SJ, Bhatia S, Baker KS. Late effects in survivors of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the bone marrow transplant survivor study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1153–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng AK, Travis LB. Second primary cancers: an overview. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:271–289. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.007. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Somers R, Van der Lelie H, Bron D, Sonneveld P, Gisselbrecht C, Cahn JY, Harousseau JL, Coiffier B, Biron P, Mandelli F, Chauvin F. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowe SN, Neuberg D, Bierman PJ, Vose JM, Nemunaitis J, Singer JW, Freedman AS, Mauch P, Demetri G, Onetto N, et al. Long-term follow-up of a phase III study of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor after autologous bone marrow transplantation for lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 1993;81:1903–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramlou-Hansen H. Smoothing counting process intensities by means of kernel functions. Ann Stat. 1983;11:453–466. [Google Scholar]

- Sebban C, Brice P, Delarue R, Haioun C, Souleau B, Mounier N, Brousse N, Feugier P, Tilly H, Solal-Celigny P, Coiffier B. Impact of rituximab and/or high-dose therapy with autotransplant at time of relapse in patients with follicular lymphoma: a GELA study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3614–3620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP, Prevedello LM, Nawfel RD, Hanson R, Khorasani R. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology. 2009;251:175–184. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511081296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetenham JW, Carella AM, Taghipour G, Cunningham D, Marcus R, Della Volpe A, Linch DC, Schmitz N, Goldstone AH. High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for adult patients with Hodgkin's disease who do not enter remission after induction chemotherapy: results in 175 patients reported to the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lymphoma Working Party. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3101–3109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Besien K, Tabocoff J, Rodriguez M, Andersson B, Mehra R, Przepiorka D, Dimopoulos M, Giralt S, Suki S, Khouri I, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with BEAC regimen and autologous bone marrow transplantation for intermediate grade and immunoblastic lymphoma: durable complete remissions, but a high rate of regimen-related toxicity. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe E, Ruiz de Elvira C, Loberiza FR, Conde E, Lopez-Guillermo A, Gisselbrecht C, Guilhot F, Vose JM, van Biesen K, Rizzo JD, Weisenburger DD, Isaacson P, Horowitz MM, Goldstone AH, Lazarus HM, Schmitz N. Outcome of autologous transplantation for mantle cell lymphoma: a study by the European Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant and Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registries. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:793–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vose JM, Zhang MJ, Rowlings PA, Lazarus HM, Bolwell BJ, Freytes CO, Pavlovsky S, Keating A, Yanes B, van Besien K, Armitage JO, Horowitz MM. Autologous transplantation for diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in patients never achieving remission: a report from the Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:406–413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vose JM, Rizzo DJ, Tao-Wu J, Armitage JO, Bashey A, Burns LJ, Christiansen NP, Freytes CO, Gale RP, Gibson J, Giralt SA, Herzig RH, Lemaistre CF, McCarthy PL, Jr, Nimer SD, Petersen FB, Schenkein DP, Wiernik PH, Wiley JM, Loberiza FR, Lazarus HM, van Biesen K, Horowitz MM. Autologous transplantation for diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma in first relapse or second remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadehra N, Farag S, Bolwell B, Elder P, Penza S, Kalaycio M, Avalos B, Pohlmanq B, Marcucci G, Sobecks R, Lin T, Andresen S, Copelan E. Long-term outcome of Hodgkin disease patients following high-dose busulfan, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and autologous stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]