Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (CaP) progression from an androgen-dependent to an androgen-independent state is associated with overexpression of EGFR family members or activation of their downstream signaling pathways, such as PI3K-Akt and MAPK. Although there are data implicating PI3K-Akt or MAPK pathway activation with resistance to EGFR inhibitors in CaP, the potential cross-talk between these pathways in response to EGFR or MAPK inhibitors remains to be examined.

METHODS

Cross-talk between PTEN and MAPK signaling and its effects on CaP cell sensitivity to EGFR or MAPK inhibitors were examined in a PTEN-null C4-2 CaP cell, pTetOn PTEN C4-2, where PTEN expression was restored conditionally.

RESULTS

Expression of PTEN in C4-2 cells exposed to EGF or serum was associated with increased phospho-ERK levels compared to cells without PTEN expression. Similar hypersensitivity of MAPK signaling was observed when cells were treated with a PI3K inhibitor LY294002. This enhanced sensitivity of MAPK signaling in PTEN-expressing cells was associated with a growth stimulatory effect in response to EGF. Furthermore, EGFR inhibitors gefitinib and lapatinib abrogated hypersensitivity of MAPK signaling and cooperated with PTEN expression to inhibit cell growth in both monolayer and anchorage-independent conditions. Similar cooperative growth inhibition was observed when cells were treated with the MEK inhibitor, CI1040, in combination with PTEN expression suggesting that inhibition of MAPK signaling could mediate the cooperation of EGFR inhibitors with PTEN expression.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that signaling cross-talk between the PI3K-Akt and MAPK pathways occurs in CaP cells, highlighting the potential benefit of targeting both the PI3K-Akt and MAPK pathways in CaP treatment.

Keywords: prostate neoplasms, PTEN, EGF receptor, tumor suppressor genes

INTRODUCTION

In androgen-dependent prostate cancer (CaP), essential growth and survival signals are mediated through the androgen receptor (AR), and androgen-ablation therapy results in tumor regression [1]. Although advanced tumors no longer respond to androgen withdrawal, they still require a functional AR. There is substantial evidence that non-steroidal cell growth and survival signaling pathways modulate AR signaling and support the growth of androgen-independent CaP [2,3]. The EGF receptor (EGFR) is over-expressed in advanced CaP [4,5], often in association with ErbB2/HER2 [6,7] and with the EGFR ligand, TGF-α [8]. The EGFR and HER2 when stimulated, activate the MAP kinase pathway, and in collaboration with HER3 can activate the PI3 kinase pathway.

Both the PI3 kinase and MAP kinase pathways have been associated with CaP progression. Activation of the MAP kinase pathway is associated with increasing CaP Gleason score and tumor stage [9]. Expression of Ras genes that activate this pathway render LNCaP cells hypersensitive to androgen [10], and conversely, expression of dominant negative Ras restores hormone dependence to the androgen-independent C4-2 cell line [11]. Amplification of PI3K has been reported in CaP [6] and immunohistochemical staining intensity of Akt was significantly more pronounced in CaP compared to benign prostatic tissue or prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia [12]. In addition, the staining intensity for phospho-Akt (pAkt) was increased in tumors and adjacent benign tissues [13] and its expression level correlated with increasing Gleason grade [14]. As a negative regulator of PI3K-Akt signaling, PTEN was identified as a hot spot for mutations in glioblastoma, breast, and CaPs [15], and is frequently inactivated in advanced CaP [16]. PTEN dephosphorylates PI3K products, phosphatidylinositol [3,4,5]-triphosphate and phosphatidylinositol [3,4]-biphosphate, which are essential to the phosphorylation and activation of Akt [17,18]. Furthermore, androgen-independent cell lines established in vitro from LNCaP cells exhibited heightened levels of AR, HER2, MAPK, and pAkt [19].

Because of its overexpression and ability to activate growth regulatory signaling pathways, the EGFR is a promising therapeutic target [20,21]. However, persistent activation of MAPK and PI3K signaling has been implicated in drug resistance to EGFR inhibitors in numerous cancers including CaP [22,23]. Although the MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways have been previously reported to cross-talk at multiple levels [24–26], it is not clear whether the cross-talk between these two signaling pathways in CaP cells would affect their response to either EGFR, PI3K, or MAPK pathway inhibitors. Here we find that physiologic inhibition of the PI3K pathway by expression of PTEN makes C4-2 CaP cells hypersensitive to EGF or serum as indicated by increased phospho-ERK (pERK) levels and cell growth; and EGFR or MEK inhibitors can abrogate this hypersensitivity and cooperate with PTEN to inhibit growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Tissue culture medium and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Cell culture plates were purchased from Corning Incorporated (Corning, NY). Epidermal growth factor (EGF) was purchased from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA). Gefitinib was obtained from AstraZeneca. Lapatinib was provided by GlaxoSmithKline. CI1040 was obtained from Pfizer. Doxycyclin (DOX) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). MTT and LY294002 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The anti-HA monoclonal antibody was purchased from Covance (Princeton, NJ). The monoclonal anti-pERK, polyclonal anti-pAkt (Ser473), anti-Akt, and anti-phospho-EGFR (pEGFR), anti-EGFR as well as anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The anti-ERK antibody was purchased from either Cell Signaling or the UVa hybridoma facility (B3B9 predominately recognizes ERK2 on Western blots). The monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody was purchased from Oncogene (San Diego, CA). The HRP conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody and SuperSignal West Femto chemiluminescence reagents were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Cell Culture

The pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells in which the expression of PTEN is under the control of TetOn system were described previously [27]. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium plus 10% FBS in a humidified chamber at 37°C with 5% CO2.

MTT Cell Proliferation Assays

MTT cell proliferation assay was described before [27]. Briefly, pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells in 10%FBS/RPMI 1640 were plated at a concentration of 2,500 cells/well in 100 μl in 96-well tissue culture plates. Twenty hours after plating, 100 μl media with or without 2× concentrations of DOX, Gefitinib, Lapatinib, CI1040, or combinations of DOX with any of the EGFR and MEK inhibitors was added into each well in 100 μl medium, bringing the final concentration to 1×. Relative cell numbers were quantified with duplicate plates at 0 and 5 days after treatment via MTT assay. For each well, 100 μl media was removed and 15 μl 0.35% MTT was added. Four hours later, 100 μl solubilization solution (10% SDS, 50% dimethyl formamide, pH 4.7) was added into each well and incubated at 37°C overnight. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm on a plate reader (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The absorbance units of the zero time point were subtracted from the absorbance units from the day 5 time points.

Soft Agarose Colony Assay

Soft agar assay was performed as described previously [27] with slight modification. C4-2 pTetOn PTEN cells were pretreated with 0.5 μg/ml DOX for 24 hr. Cells were trypsinized and re-suspended in 3 ml of 0.4% SeaPlaque soft agarose (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ) supplemented with 10% FBS/RPMI 1640 medium, and layered on top of a pre-gelled 0.6% bottom layer of agar. Final cell density was 24,000 cells/well per six-well plate. At the time of plating, 5 μM Gefitinib, or 0.25 μM Lapatinib either with or without 0.5 μg/ml DOX were added into agar. After 2 weeks of incubation, plates were scanned on a flatbed scanner and colony numbers were quantified by ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

Preparation of Cell Lysates and Western Blot Analysis

pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells were plated in 6-well plates to a similar density as those in 96-well plates used for growth studies described above. Cells were treated with DOX, Gefitinib, Lapatinib, CI1040, or a combination of DOX with the EGFR and MEK inhibitors as described above. After 5 days treatment, 1 ng/ml EGF was added to the cells for 15 min prior to harvesting protein. Cells were washed in cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40 with protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Western blotting was carried out as described [28] using commercial chemiluminescence reagents (SuperSignal West Femto) and photographic film. The anti-HA monoclonal antibody was used at 1:3,000 dilution. The monoclonal anti-pERK, polyclonal anti-pAkt (Ser473), anti-Akt, anti-ERK, and anti-pEGFR antibodies were used at 1:1,500 dilution. The monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody was diluted at 1:2,000. The HRP conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were used at a 1:200,000 and 1:100,000 dilution respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Two-way ANOVA was carried out to compare cell growth after PTEN expression following DOX treatment across groups. Data were transformed to the log scale to meet the common variance assumption of 2-way ANOVA. Contrasts were used to compare cell growth inhibition using the combination of DOX and the EGFR or MEK inhibitor to the inhibition under DOX, the EGFR or MEK inhibitor alone. Contrasts were also used to test for statistical interaction, evaluating whether the magnitude of the effect of the EGFR or MEK inhibitor on cell growth inhibition depends on whether DOX is present or absent. In other words, the significance of statistical interaction suggests that the effect between DOX and the EGFR or MEK inhibitor is not the purely additive. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significance.

RESULTS

PTEN Expression Sensitizes C4-2 Cells to EGF and Serum Stimulation

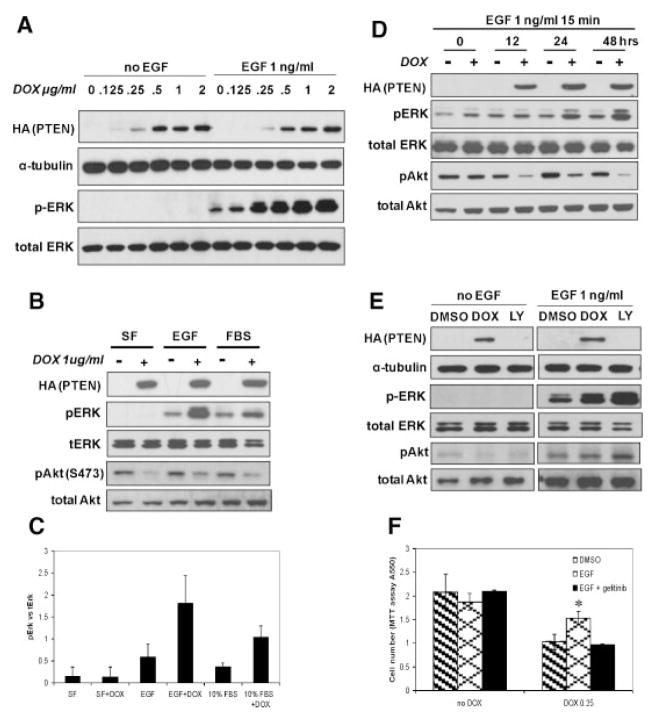

We previously established a conditional PTEN expressing C4-2 CaP cell line, pTetOn PTEN C4-2, where PTEN expression was under the control of the TetOn system [27]. In this prior study, we showed that PTEN induction in C4-2 cells enhanced responsiveness to the anti-proliferative effects of anti-androgens and that this action may involve non-AR mediated effects [27]. We also showed that expression of a dominant negative N17 Ha-Ras can restore androgen dependence to androgen-independent C4-2 cells [11] and that MAPK activation is increased in advanced and androgen-independent CaP [9]. These results, combined with those in the literature [29], led us to explore the cross-talk between PTEN and Ras–MAPK signaling in pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells. We began by testing pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cell sensitivity to stimuli that activate the Ras–MAPK pathway. In response to exogenous EGF stimulation, PTEN expressing C4-2 cells were dramatically more sensitive to EGF stimulation than were the non-induced cells, as demonstrated by an increase in pERK levels (Fig. 1A). This hypersensitivity to EGF stimulation correlated with the amount of PTEN expressed. Similarly, expression of PTEN increased pERK levels in cells stimulated with 10% FBS (Fig. 1B,C). These data suggest that PTEN expression sensitizes C4-2 cells to EGF and serum stimulation resulting in an increase in MAPK/ERK signaling.

Fig. 1.

pERK levels and growth effect in C4-2cells after PTEN expression in response to EGF and serum stimulation. A: pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with various concentrations of DOX for 48 hr. Cells were either treated with or without 1 ng/ml EGF for 15 min before cells were harvested for Western blot. B: pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with 1 μg/ml DOX for 48 hr. Cells were treated with either 1 ng/ml EGF or 10% FBS for 15 min before they were harvested for Western blot. For FBS stimulation, cells were switched to serum-free (SF) medium for 16 hr prior to the addition of FBS. For EGF stimulation, cells were kept in normal10% FBS medium. C: Densitometry analysis of Western blot (B). Relative pERK to total-ERK (tERK) levels in three independent experiments were quantitated with AlphaInnotech software. D: pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells were treated with 2 μg/ml DOX to induce PTEN expression for various times. For each time point, 1ng/ml EGF was added 15 min before cells were harvested for Western blot. The expression levels of PTEN and corresponding pERK levels were characterized by SDS–PAGE Western blots with anti-HA antibody for PTEN, anti-pERK antibody for pERK respectively. E: pTetOn PTENC4-2cells were treated with 0.5 μg/ml DOX or 3.125 μM LY294002 for 48 hr. Cells were either treated with or without 1 ng/ml EGF for 15 min before cells were harvested for Western blot. F: Growth effect of EGF on PTEN expressing cells. pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with 0.25 μg/ml DOX and 50 ng/ml EGF with or without 5 μM EGFR inhibitor gefitinib for120 hr. Cell numbers were measured with MTT assay at the end of treatment. * indicates statistical significance compared to DMSO treatment. Total-ERK in panels (A) and (D) detected by B3B9 antibody and by antibody from cell signaling in panels (B) and (E) as described in Materials and Methods.

To determine whether the increased ERK activity was due to direct cross-talk of PTEN and Ras–MAPK signaling or required a secondary event, we performed a time course study examining the correlation between PTEN expression and ERK activity in response to EGF. Although significant PTEN expression and concomitant decrease in pAkt were observed after 12 hr of DOX treatment, cells were hypersensitive to EGF stimulation only following 24 hr of DOX treatment (Fig. 1D). This suggests that the hypersensitivity of PTEN expressing cells to EGF or serum stimulation of ERK activity likely requires a secondary event triggered by PTEN expression. To confirm that the increased level of ERK activity following PTEN expression was not due to the DOX treatment itself we did a similar time course experiment on pTetOn C4-2 cells that lack the pTRE2-PTEN expression vector. As expected, PTEN expression was not induced and there was no increase in ERK activity following DOX treatment (data not shown), suggesting that the pERK hypersensitivity of PTEN expressing cells to EGF or serum is specific to PTEN expression in C4-2 cells. To see whether the increased ERK activity in PTEN expressing cells was due to the inhibition of PI3K signaling by PTEN we examined pErk levels in pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells treated with LY294002. Similar hypersensitivity of MAPK signaling was observed with LY294002 treatment (Fig. 1E) suggesting the increased ERK activity in PTEN expressing cells was due to the inhibition of PI3K signaling.

To determine whether PTEN-induced hypersensitivity to EGF was associated with any biological consequence, we performed a growth study following PTEN expression with or without EGF treatment. PTEN expression reduced the growth rate of C4-2 cells approximately 50%, consistent with the importance of PI3K signaling in growth promotion [27]. Addition of EGF partially reversed this growth inhibition and this growth restoration was completely abrogated by gefitinib (Fig. 1F), a selective EGFR inhibitor [30].

PTEN Expression Regulates EGFR Inhibitor Sensitivity in C4-2 Prostate Cancer Cells

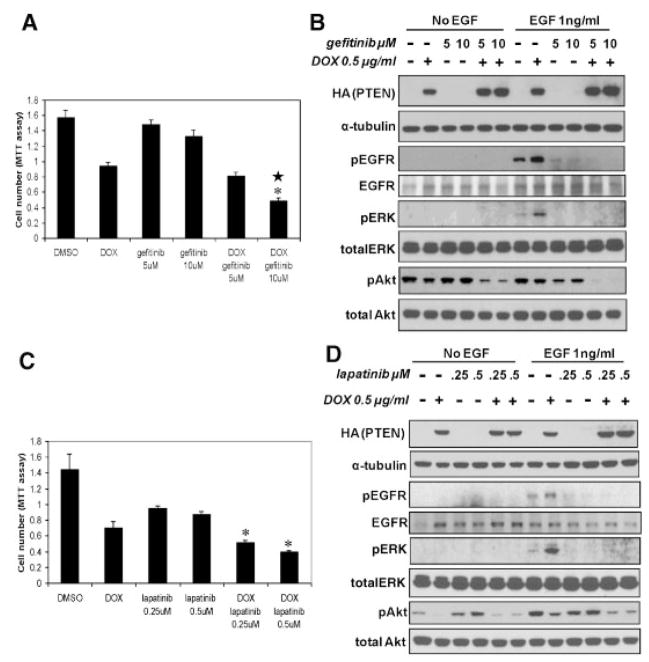

The increased MAPK/ERK signaling in PTEN expressing cells in response to EGF and its associated growth stimulatory effect led us to determine if inhibitors targeting EGFR–Ras–MAPK signaling could abrogate the MAPK hypersensitivity and cooperate with PTEN expression to further inhibit C4-2 cell growth. Here we examined the growth of gefitinib-treated cells with or without PTEN expression. Gefitinib inhibited C4-2 cell growth only slightly, consistent with reports that EGFR inhibitors are not effective as single agents against advanced CaP. PTEN expression treatment alone inhibited C4-2 cell growth about 40%, as shown also in Figure 1F, above. However, PTEN plus gefitinib inhibited cell growth by nearly 70% of control with significant statistical interaction (Fig. 2A). In addition, gefitinib completely abrogated the increased pEGFR and pERK levels following PTEN expression (Fig. 2B). This block of MAPK hypersensitivity suggests a possible mechanism for the cooperative effects of PTEN and gefitinib on cell growth inhibition. Without PTEN expression, gefitinib alone did not inhibit pAkt levels in cells cultured in 10% FBS. However, gefitinib did diminish the ability of EGF to increase pAkt levels (Fig. 2B). In addition, PTEN expression and gefitinib treatment cooperated in decreasing pAkt levels when compared to either PTEN or gefitinib alone. Collectively, the data suggest that gefitinib cooperates with PTEN expression to inhibit C4-2 cell growth.

Fig. 2.

Effect of PTEN expression plus gefitinib or lapatinib on C4-2 cell growth. A: pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells were treated with 0.5 μg/ml DOX to induce PTEN expression, 5 or10 μM gefitinib or both DOX and gefitinib for 96 hr. Cell numbers were measured with MTT assay at the end of 96 hr treatment.*indicates statistical significance compared to DOX or gefitinib alone. ★ indicates statistical interaction between DOX and gefitinib. B: Western blot for the growth study in A. Duplicate 6-well plates with pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with DOX or gefitinib the same way as cells in growth study (A). Cell lysate was made for Western blots at the end of 96 hr treatment and EGF (1ng/ml) was added 15 min before making the cell lysate. Levels of PTEN induction, pEGFR, pERK, and pAkt were characterized by SDS–PAGE Western blot analysis. C: pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with 0.5 μg/ml DOX to induce PTEN expression, 0.25 or 0.5 μM lapatinib or both DOX and lapatinib for 120 hr. Cell numbers were measured by the MTT assay at the end of 120 hr treatment. *indicates statistical significance compared to DOX or lapatinib alone. D: Western blot for the growth study in (C). Duplicate 6-well plates with pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with DOX or lapatinib the exact same way as cells in growth study(C). Cell lysate was made for Western blots at the end of 120 hr treatment and EGF (1 ng/ml) was added 15 min before making the cell lysate. Levels of PTEN induction, pEGFR, pERK, and pAkt were characterized by SDS–PAGE Western blot analysis.

To confirm this finding, we carried out similar experiments using lapatinib (GW572016), a dual EGFR-erbB2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor [31], on C4-2 cell growth in the presence or absence of PTEN expression. Here PTEN expression alone inhibited cell growth about 50%, while 0.25 or 0.5 μM lapatinib treatment decreased cell growth about 40% (Fig. 2C). The greater effectiveness of lapatinib compared to that of gefitinib in inhibiting C4-2 growth is presumably because of its broader specificity. In the presence of PTEN expression, 0.25 or 0.5 μM lapatinib treatment resulted in further cell growth inhibition, 64 and 70% respectively, compared to PTEN or lapatinib alone. Similar to gefitinib, lapatinib completely blocked the MAPK hypersensitivity caused by PTEN expression (Fig. 2D). Although lapatinib alone had a minimal effect on pAkt levels, it significantly decreased the pAkt levels in the presence of PTEN expression when cells were stimulated with EGF (Fig. 2D). Collectively these data suggest that the PTEN status of C4-2 CaP cells regulates EGFR inhibitor sensitivity.

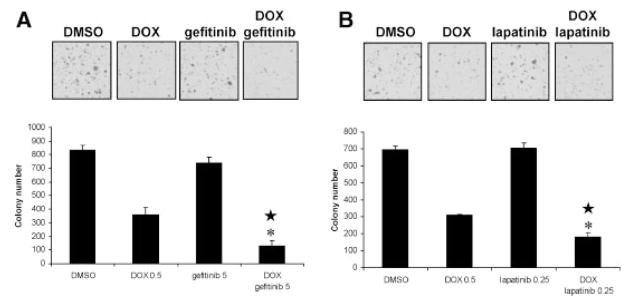

Since anchorage-independent growth is a hallmark of malignant transformation and tumorigenicity, we sought to determine whether PTEN expression could modulate EGFR inhibitor sensitivity on C4-2 cell colony formation in agar. While PTEN expression with 0.5 μg/ml DOX treatment decreased colony number about 55% in C4-2 cells, 5 μM gefitinib or 0.25 μM lapatinib treatment caused minimal (15%) or no reduction in colony numbers respectively (Fig. 3A,B). However, 0.5 μg/ml DOX combined with either 5 μM gefitinib or 0.25 μM lapatinib resulted in a 85 or 75% decrease in colony formation respectively with both combinations showing significance of statistical interaction (Fig. 3A,B). This result suggests that PTEN expression not only regulates EGFR inhibitor sensitivity in monolayer C4-2 cell growth but also sensitizes C4-2 cells to EGFR inhibitors in anchorage-independent growth.

Fig. 3.

Effect of PTEN expression plus EGFR inhibitors on C4-2 cell anchorage-independent growth. pTetOn PTEN C4-2 cells were pretreated with 0.5 μg/ml DOX for 24 hr to induce PTEN expression and resuspended in10% FBS-supplemented semisolid agarose containing 0.5 μg/ml DOX in six-well plate with a final cell concentration of 24,000 cells/well. A: 5 μM gefitinib or (B) 0.25 μM lapatinib was added at the time of plating in the agarose medium. Plates were scanned and colony numbers were quantified with ImagePro software after two weeks of growth. * indicates statistical significance compared to DOX, gefitinib, or lapatinib treatment alone. ★ indicates statistical interaction between DOX and gefitinib or lapatinib treatment.

PTEN Expression Cooperates With MEK Inhibition on C4-2 Cell Growth

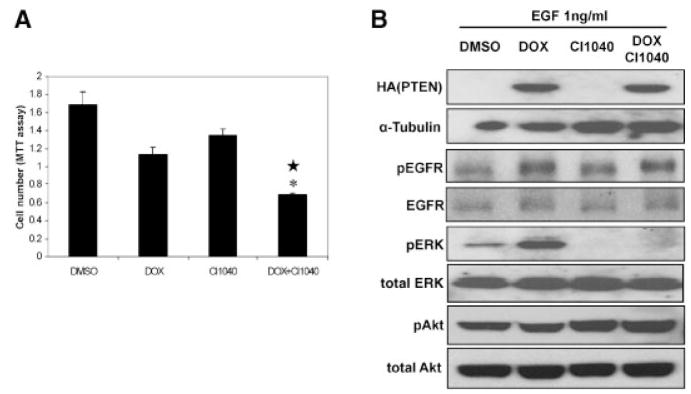

There are multiple signal transduction pathways downstream of EGFR signaling [32] and the Ras–MAPK pathway is a major one. We have shown that Ras–MAPK signaling contributes to CaP progression [3,9–11]. Additionally, the data presented above indicate that PTEN expression hypersensitizes C4-2 cells to MAPK activation by EGF and serum (Fig. 1), and this hypersensitivity could be inhibited by gefitinib or lapatinib (Fig. 2). This suggested to us that the cooperativity of EGFR inhibitors with PTEN expression in regulating C4-2 cell growth could be mediated through inhibition of MAPK signaling. Thus, we asked whether inhibiting MAPK signaling with CI1040, a MEK inhibitor [33] could cooperate with PTEN expression in inhibiting C4-2 CaP cell growth. While PTEN and CI1040 inhibited cell growth 30 and 20% respectively, PTEN plus CI1040 decreased cell growth by nearly 60%, indicating statistical interaction (Fig. 4A). This suggests that, similar to the EGFR inhibitors, the effect of MEK inhibition on C4-2 cells is potentiated by PTEN expression. As expected, CI1040 could completely block the increased pERK levels induced by EGF in PTEN expressing cells (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the ability of EGFR inhibition to cooperate with PTEN expression is mediated by the MAP kinase pathway.

Fig. 4.

Effect of PTEN expression plus CI1040 on C4-2 cell growth. A: pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with 0.5μg/ml DOX to induce PTEN expression, 500nM CI1040 or both DOX and CI1040 for 96 hr. Cell numbers were measured with MTT assay at the end of 96 hr treatment. B: Western blot for the growth study in (A). Duplicate 6-well plates with pTetOn PTENC4-2 cells were treated with DOX or CI1040 the exact same way as cells in growth study (A). Cell lysate was made for Western blots at the end of 96 hr treatment and EGF (1 ng/ml) was added15 min before making the cell lysate. Levels of PTEN induction, pERK, and pAkt were characterized by SDS–PAGE Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibody for PTEN, anti-pERK antibody for pERK, and anti-pAkt antibody for pAkt.

DISCUSSION

Growth signaling plays an essential role in CaP progression [3] and cross-talk between different growth signaling pathways integrates diverse cellular inputs required for cell growth and survival [34,35]. In our present study, we examined cross-talk between the Ras–MAPK and PI3K–Akt signaling pathways in androgen-independent C4-2 CaP cells. We found that PTEN expression in C4-2 cells made cells hypersensitive to EGF or serum stimulation as indicated by increased pERK levels. This hypersensitivity of MAPK signaling was due to the PTEN inhibition of PI3K–Akt pathway since a similar effect was noted with LY294002 treatment while the expression of the G129E mutant PTEN, lacking lipid phosphatase activity, had no effect on ERK activity levels (data not shown). Although 12 hr DOX treatment resulted in marked expression of PTEN, the hypersensitivity to EGF stimulation was not observed until 24 hr after DOX treatment. Thus, it is very likely that the PTEN induced hypersensitivity to EGF activation of ERK requires a secondary event and is not due to direct cross-talk by components of the PI3K–Akt or Ras–MAPK pathways.

Due to the inactivation of PTEN, the C4-2 CaP cell has constitutively active PI3K–Akt signaling that is essential to its growth [27,36]. The hypersensitivity to EGF after PTEN restoration could be a compensatory mechanism used by cells to shift growth factor-dependent signaling from the PI3K–Akt to the Ras–MAPK pathway when PI3K–Akt signaling is inhibited. This is further supported by our data showing that the hypersensitivity to EGF was associated with a growth stimulatory effect following PTEN expression and this growth enhancement could be completely abrogated by the EGFR inhibitors gefitinib or lapatinib. Signaling compensation for maintaining cancer cell growth has been previously reported. For example, treatment of human glioblastoma, breast, and CaP cells with EGFR inhibitors could result in a compensatory activation of IGF-1 and its downstream PI3K signaling [37,38]. It has been previously shown that CaP progression to androgen-independence is associated with the acquisition of enhanced redundancy in downstream survival signaling such as ERK, p38, JNK, and Akt signaling [39]. The redundancy in growth signaling could enable CaP cells to maintain growth by switching to different signaling pathways when certain growth pathways are inhibited. Both PI3K-Akt and Ras-MAPK signaling have been implicated in modulating androgen receptor (AR) activity in androgen-independent CaP cells [3,40]. Switching signaling between PI3K-Akt and Ras-MAPK pathways may also be important for androgen-independent CaP cells to maintain their growth in an androgen-depleted state. Although the mechanism(s) underlying this hypersensitivity to EGF stimulation after PTEN expression is not clear at this time, previous studies have shown that activation of Akt inhibits the activity of Raf by phosphorylation of Raf on Ser 259 and Ser 338 [25,41]. Thus, it is possible that the decreased Akt activity in PTEN expressing cells removes an inhibitory signal and thus hypersensitizes the Raf–MEK–ERK signaling pathway to activation. However, the kinetics of the PTEN induced hypersensitivity of ERK activation and the modest effects of PTEN expression on basal pAkt would suggest that an alternative mechanism is operating.

Cellular PTEN levels have been associated with drug resistance to EGFR inhibitors and the cooperativity of EGFR inhibition with PTEN expression (or inhibition of PI3K–Akt signaling by other methods) to reduce cell growth has been reported in small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, and CaP cells [42–44]. Uncoupling between EGFR and MAPK signaling and persistent MAPK activity in the presence of EGFR inhibition was reported to cause resistance to the anti-proliferative effects of gefitinib [45]. Other studies have indicated that uncoupling of EGFR signaling to Akt due to PTEN loss, which leads to high levels of Akt activity, results in resistance to EGFR inhibitors [46,47]. This is supported by our data here showing that PTEN expression makes CaP C4-2 cells more sensitive to gefitinib or lapatinib inhibition of pAkt levels (Fig. 2B,D). In addition, increased signaling of IGFI-R to PI3K–Akt has been shown to contribute to resistance to anti-EGFR treatment [37,38]. Furthermore, Janmaat et al. demonstrated that K-Ras mutations correlated with resistance to EGFR antagonists [23]. Additionally, She et. al. showed that induction of PTEN sensitized MDA-468 breast cancer cells to EGFR inhibition and this synergistic effect was due to the inhibition of two parallel pathways that phosphorylate the proapoptotic protein BAD at distinct sites [44]. However, we did not observe any apoptotic effect (sub G1/G0 population) in our CaP cells treated with the MEK inhibitor in combination with PTEN expression (data not shown). This is consistent with reports from Carson et al. and Kulik et al. [48] showing that PI3K inhibitors did not synergize with MEK inhibitors to cause apoptosis, in CaP cells in the presence of serum [49]. Our study suggests that blockade of EGFR or MAPK signaling cooperates with PTEN to inhibit CaP cell growth. Our results, along with findings of other groups, suggest that multiple mechanisms may be involved in the cooperative effect on growth inhibition by targeting both EGFR–MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways.

CONCLUSIONS

The PI3K–Akt signaling pathway is an attractive target for cancer treatment because of its important role in promoting cell growth and survival in numerous cancers, including CaP. Our previous study together with other reports indicated that inhibition of PI3K–Akt signaling itself by either induction of PTEN or treatment with PI3K inhibitors could almost completely inhibit CaP cell growth [27,50]. However, it has become increasingly clear that the efficacy of therapeutics which target a single pathway are limited and that combinatorial therapies will be needed for the effective treatment of cancer. We observed that restoration of PTEN expression in PTEN null C4-2 cells hypersensitized the cells to EGFR–MAPK signaling; this suggested a shift in growth-dependent signaling from PI3K–Akt to Ras–MAPK in cells that were once dependent on Akt for growth and survival. Our study here indicates that a combinatorial treatment which inhibits the EGFR–MAPK and PI3K–Akt pathways may be a more effective treatment than one that targets either alone.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant number: CA104106.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.De La Taille A, Vacherot F, Salomon L, Druel C, Gil Diez De Medina S, Abbou C, Buttyan R, Chopin D. Hormone-refractory prostate cancer: A multi-step and multi-event process. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2001;4(4):204–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Culig Z. Androgen receptor cross-talk with cell signalling pathways. Growth Factors. 2004;22(3):179–184. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gioeli D. Signal transduction in prostate cancer progression. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;108(4):293–308. doi: 10.1042/CS20040329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald A, Habib FK. Divergent responses to epidermal growth factor in hormone sensitive and insensitive human prostate cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1992;65(2):177–182. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culig Z, Hobisch A, Cronauer MV, Radmayr C, Trapman J, Hittmair A, Bartsch G, Klocker H. Androgen receptor activation in prostatic tumor cell lines by insulin-like growth factor-I, keratinocyte growth factor, and epidermal growth factor. Cancer Res. 1994;54(20):5474–5478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards J, Krishna NS, Witton CJ, Bartlett JM. Gene amplifications associated with the development of hormone-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(14):5271–5281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agus DB, Akita RW, Fox WD, Lofgren JA, Higgins B, Maiese K, Scher HI, Sliwkowski MX. A potential role for activated HER-2 in prostate cancer. Semin Oncol. 2000;27(6 Suppl 11):76–83. discussion, 92–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scher HI, Sarkis A, Reuter V, Cohen D, Netto G, Petrylak D, Lianes P, Fuks Z, Mendelsohn J, Cordon-Cardo C. Changing pattern of expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor alpha in the progression of prostatic neoplasms. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1(5):545–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gioeli D, Mandell JW, Petroni GR, Frierson HF, Jr, Weber MJ. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 1999;59(2):279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakin RE, Gioeli D, Sikes RA, Bissonette EA, Weber MJ. Constitutive activation of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway promotes androgen hypersensitivity in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63(8):1981–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakin RE, Gioeli D, Bissonette EA, Weber MJ. Attenuation of Ras signaling restores androgen sensitivity to hormone-refractory C 4-2prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63(8):1975–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao Y, Grobholz R, Abel U, Trojan L, Michel MS, Angel P, Mayer D. Increase of AKT/PKB expression correlates with gleason pattern in human prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;107(4):676–680. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merseburger AS, Hennenlotter J, Simon P, Muller CC, Kuhs U, Knuchel-Clarke R, Moul JW, Stenzl A, Kuczyk MA. Activation of the PKB/Akt pathway in histological benign prostatic tissue adjacent to the primary malignant lesions. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(1):79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik SN, Brattain M, Ghosh PM, Troyer DA, Prihoda T, Bedolla R, Kreisberg JI. Immunohistochemical demonstration of phospho-Akt in high Gleason grade prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(4):1168–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, Puc J, Miliaresis C, Rodgers L, McCombie R, Bigner SH, Giovanella BC, Ittmann M, Tycko B, Hibshoosh H, Wigler MH, Parsons R. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275(5308):1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ittmann MM. Chromosome 10 alterations in prostate adenocarcinoma (review) Oncol Rep. 1998;5(6):1329–1335. doi: 10.3892/or.5.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(22):13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datta K, Bellacosa A, Chan TO, Tsichlis PN. Akt is a direct target of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Activation by growth factors, v-src and v-Ha-ras, in Sf9 and mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(48):30835–30839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi XB, Ma AH, Tepper CG, Xia L, Gregg JP, Gandour-Edwards R, Mack PC, Kung HJ, deVere White RW. Molecular alterations associated with LNCaP cell progression to androgen independence. Prostate. 2004;60(3):257–271. doi: 10.1002/pros.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arteaga CL. The epidermal growth factor receptor: From mutant oncogene in nonhuman cancers to therapeutic target in human neoplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19 (18 Suppl):32S–40S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yarden Y. The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. signalling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 (Suppl 4):S3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magne N, Fischel JL, Dubreuil A, Formento P, Poupon MF, Laurent-Puig P, Milano G. Influence of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), p53 and intrinsic MAP kinase pathway status of tumour cells on the antiproliferative effect of ZD1839 (“Iressa”) Br J Cancer. 2002;86(9):1518–1523. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janmaat ML, Rodriguez JA, Gallegos-Ruiz M, Kruyt FA, Giaccone G. Enhanced cytotoxicity induced by gefitinib and specific inhibitors of the Ras or phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase pathways in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(1):209–214. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Q, Zhou Y, Wang X, Evers BM. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is a negative regulator of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Oncogene. 2006;25(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rommel C, Clarke BA, Zimmermann S, Nunez L, Rossman R, Reid K, Moelling K, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Differentiation stage-specific inhibition of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway by Akt. Science. 1999;286(5445):1738–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan KL, Figueroa C, Brtva TR, Zhu T, Taylor J, Barber TD, Vojtek AB. Negative regulation of the serine/threonine kinase B-Raf by Akt. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(35):27354–27359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Z, Conaway M, Gioeli D, Weber MJ, Theodorescu D. Conditional expression of PTEN alters the androgen responsiveness of prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2006;66(10):1114–1123. doi: 10.1002/pros.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gildea JJ, Seraj MJ, Oxford G, Harding MA, Hampton GM, Moskaluk CA, Frierson HF, Conaway MR, Theodorescu D. RhoGDI2 is an invasion and metastasis suppressor gene in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62(22):6418–6423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cully M, You H, Levine AJ, Mak TW. Beyond PTEN mutations: The PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):184–192. doi: 10.1038/nrc1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakeling AE, Guy SP, Woodburn JR, Ashton SE, Curry BJ, Barker AJ, Gibson KH. ZD1839 (Iressa): An orally active inhibitor of epidermal growth factor signaling with potential for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62(20):5749–5754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia W, Mullin RJ, Keith BR, Liu LH, Ma H, Rusnak DW, Owens G, Alligood KJ, Spector NL. Anti-tumor activity of G W572016: A dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks EGF activation of EGFR/erbB2 and downstream Erk1/2 and AKT pathways. Oncogene. 2002;21(41):6255–6263. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogdan S, Klambt C. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Curr Biol. 2001;11(8):R292–295. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Dudley DT, Herrera R, Van Becelaere K, Wiland A, Gowan RC, Tecle H, Barrett SD, Bridges A, Przybranowski S, Leopold WR, Saltiel AR. Blockade of the MAP kinase pathway suppresses growth of colon tumors in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5(7):810–816. doi: 10.1038/10533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2000;103(2):211–225. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz MA, Baron V. Interactions between mitogenic stimuli, or, a thousand and one connections. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11(2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vlietstra RJ, van Alewijk DC, Hermans KG, van Steenbrugge GJ, Trapman J. Frequent inactivation of PTEN in prostate cancer cell lines and xenografts. Cancer Res. 1998;58(13):2720–2723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarti A, Loeffler JS, Dyson NJ. Insulin-like growth factor receptor I mediates resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy in primary human glioblastoma cells through continued activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling. Cancer Res. 2002;62(1):200–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones HE, Goddard L, Gee JM, Hiscox S, Rubini M, Barrow D, Knowlden JM, Williams S, Wakeling AE, Nicholson RI. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signalling and acquired resistance to gefitinib (ZD1839; Iressa) in human breast and prostate cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11(4):793–814. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uzgare AR, Isaacs JT. Enhanced redundancy in Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase-induced survival of malignant versus normal prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):6190–6199. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin HK, Yeh S, Kang HY, Chang C. Akt suppresses androgen-induced apoptosis by phosphorylating and inhibiting androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(13):7200–7205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121173298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimmermann S, Moelling K. Phosphorylation and regulation of Raf by Akt (protein kinase B) Science. 1999;286(5445):1741–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kokubo Y, Gemma A, Noro R, Seike M, Kataoka K, Matsuda K, Okano T, Minegishi Y, Yoshimura A, Shibuya M, Kudoh S. Reduction of PTEN protein and loss of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in lung cancer with natural resistance to gefitinib (IRESSA) Br J Cancer. 2005;92(9):1711–1719. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Festuccia C, Muzi P, Millimaggi D, Biordi L, Gravina GL, Speca S, Angelucci A, Dolo V, Vicentini C, Bologna M. Molecular aspects of gefitinib antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in PTEN-positive and PTEN-negative prostate cancer cell lines. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(4):983–998. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.She QB, Solit DB, Ye Q, O’Reilly KE, Lobo J, Rosen N. The BAD protein integrates survival signaling by EGFR/MAPK and PI3K/Akt kinase pathways in PTEN-deficient tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(4):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kassouf W, Dinney CP, Brown G, McConkey DJ, Diehl AJ, Bar-Eli M, Adam L. Uncoupling between epidermal growth factor receptor and downstream signals defines resistance to the antiproliferative effect of Gefitinib in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(22):10524–10535. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.She QB, Solit D, Basso A, Moasser MM. Resistance to gefitinib in PTEN-null HER-overexpressing tumor cells can be overcome through restoration of PTEN function or pharmacologic modulation of constitutive phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt pathway signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(12):4340–4346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bianco R, Shin I, Ritter CA, Yakes FM, Basso A, Rosen N, Tsurutani J, Dennis PA, Mills GB, Arteaga CL. Loss of PTEN/MMAC1/TEP in EGF receptor-expressing tumor cells counteracts the antitumor action of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2003;22(18):2812–2822. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kulik G, Carson JP, Vomastek T, Overman K, Gooch BD, Srinivasula S, Alnemri E, Nunez G, Weber MJ. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces BID cleavage and bypasses antiapoptotic signals in prostate cancer LNCaP cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(6):2713–2719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carson JP, Kulik G, Weber MJ. Antiapoptotic signaling in LNCaP prostate cancer cells: A survival signaling pathway independent of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and Akt/protein kinase B. Cancer Res. 1999;59(7):1449–1453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghosh PM, Malik SN, Bedolla RG, Wang Y, Mikhailova M, Prihoda TJ, Troyer DA, Kreisberg JI. Signal transduction pathways in androgen-dependent and -independent prostate cancer cell proliferation. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(1):119–134. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]