Abstract

Introduction: Not all convulsive episodes are due to epilepsy and a number of these have a cardiovascular cause. Failure to identify these patients delays the provision of adequate therapy while at the same time exposes the individual to the risk of injury or death.

Methods: We report on three patients who suffered from recurrent convulsive episodes, thought to be epileptic in origin, who were refractory to antiseizure therapy. Although each patient had undergone extensive evaluation, no other potential cause of his or her seizure like episodes had been uncovered. In each patient placement of an implantable loop recorder (ILR) demonstrated that their convulsive episodes were due to prolonged periods of cardiac asystole and/or complete heart block. In all patients their convulsive episodes were eliminated by permanent pacemaker implantation.

Conclusion: In patients with refractory “seizure' like episodes of convulsive activity of unknown etiology a potential cardiac rhythm disturbance should be considered and can be easily evaluated by ILR placement.

Keywords: Implantable loop recorders, Convulsions, Syncope.

Introduction

It has been estimated that up to three percent of the US population suffers from recurrent convulsive episodes that are usually thought to be seizures due to epilepsy 1, 2. However recent studies have suggested that as many as 20% to 30% of these individuals have an occult cardiovascular cause of their convulsive events. A variety of cardiac rhythm disturbances will create a state of cerebral hypoxia that can be manifested by convulsive activity that may be difficult to distinguish from epileptic seizure activity. Indeed, the difficulty in distinguishing epileptic seizures from other conditions that can cause convulsive activity has been long recognized 3, 4. The exact frequency at which patients with non-epileptic convulsive disorders are misdiagnosed as having epilepsy is unclear 3, 4, 5, 6. Gastaut et al 7 has estimated that as many as one third of patients initially diagnosed with epilepsy actually had a cardiovascular cause of their convulsive episodes. Schott et al 8 found that 20% of patients diagnosed with idiopathic epilepsy actually had a cardiac arrhythmia as a cause of their convulsive events. Currently, the majority of patients suffering from “seizure like” episodes are diagnosed as having epilepsy purely on clinical grounds, often without extensive cardiovascular investigations and without corroborating electroencephalographic (EEG) evidence 9, 10. We report on three patients who were initially diagnosed with recurrent seizures due to epilepsy. Due to the recurrent nature of their convulsive events, lack of a response to anti-seizure medications, and normal cardiac evaluations patients were referred to our center for further evaluation. It was only following prolonged cardiac rhythm monitoring with an implantable loop recorder (ILR) that a cardiac rhythm abnormality was identified as the cause of their recurrent convulsive events.

Case 1

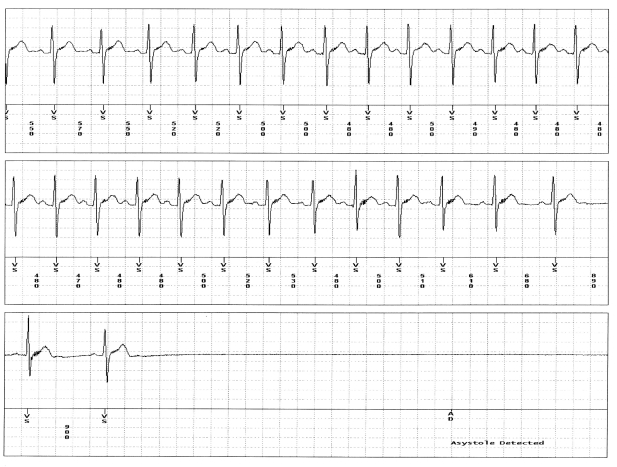

A 10 year-old young man who had suffered from recurrent idiopathic “seizures” since he was one year of age was referred for evaluation. During these episodes the patient would suddenly turn pale then abruptly fall to the floor followed by convulsive activity that would last anywhere from 30 seconds to one minute. He would often be incontinent of urine and have a postictal period of confusion and disorientation lasting from ten to twenty minutes, followed by severe confusion and fatigue that would persist for the remainder of the day. The patient would experience between five and seven major episodes each year, as well as less severe episodes every one to two months. The patient had undergone extensive neurologic and cardiovascular evaluation at the several major medical centers in the US, yet an etiology for these events could not be found. The patients' electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, baseline and sleep deprived electroencephalogram (EEG), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain were all normal (each having been repeated multiple times). A head upright tilt table test was normal as was an exercise stress test. He was tried on multiple seizure medications to no avail. External event recorders were unable to capture an episode. An ILR (Medtronic Reveal XT) was inserted in the patient and one month later, the patient experienced a witnessed “mild” convulsive episode while sitting at the table. The download of the ILR showed the patient had experienced > 20 seconds of cardiac systole coincident with the episode (Figure 1). Afterward he underwent dual chamber pacemaker placement and over a ten-month follow-up has had no further convulsive events.

Figure 1.

Tracings downloaded from ILR shows prolonged asystole.

Case 2

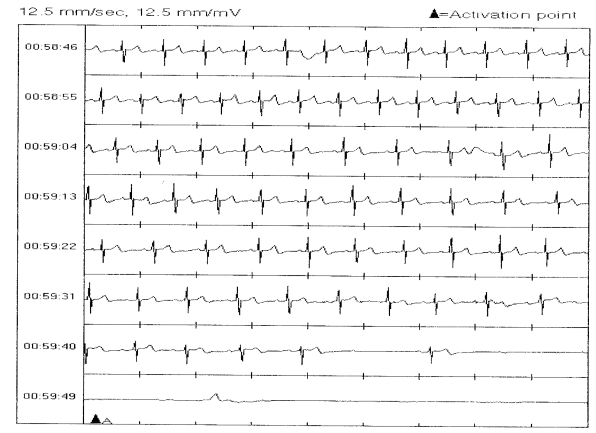

A 41-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of recurrent convulsive episodes. At the age of 29 years, she began to experience episodes of sudden loss of consciousness associated with convulsive activity. Her husband described each episode as similar in nature. She would experience a prodrome of ringing in her ears followed by an abrupt loss of consciousness. She would become pale “her eyes would roll back” and she would collapse to the floor. She would then experience convulsive activity that would last between 10 seconds and 15 minutes. During episodes, she would experience urinary incontinence and on two episodes had fecal incontinence. She also suffered from multiple traumatic injuries to her face head and arms during these episodes. She underwent an extensive series of neurologic and cardiovascular evaluations at several institutions over the years yet no etiology for the events could be found. The electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, EEG, and MRI of the brain were normal. Head upright tilt table testing was normal (on two occasions), as was an exercise tolerance test. A cardiac catheterization and cardiac electrophysiology study were both normal. A sleep study was also normal. Prolonged external cardiac event monitoring was unable to capture an episode. Her recurrent unpredictable episodes caused her to become reclusive and homebound. After consultation at our institution, she underwent ILR implantation (Medtronic Reveal Dx). This demonstrated that her witnessed convulsive events were associated with prolonged episodes of cardiac asystole and complete heart block (Figure 2). Since pacemaker implantation, she has had no further convulsive episodes over a 17-month follow up period.

Figure 2.

Asystole on a tracing downloaded from ILR.

Case 3

A 51-year-old woman had a nine-year history of recurrent convulsive episodes thought to be seizures. Her episodes were intermittent, occurring without any prodrome and were associated with convulsive activity. Episodes were associated with urinary incontinence and a post-ictal confusional state. The falls associated with three episodes resulted in trauma to the head, face and arms. She underwent an extensive neurologic and cardiovascular evaluation at several institutions, yet no etiology could be found. An electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, EEG and MRI of the brain were normal (each having been repeated multiple times). Head upright tilt table testing was performed on two separate occasions and were both normal. An exercise tolerance test was normal. A cardiac electrophysiology study normal, as was a sleep study. External event monitors were unable to capture an episode. She was tried on multiple anti-seizure medications yet none of these altered the frequency or severity of her events. After being seen at our institution, she underwent ILR placement (Medtronic Dx). The ILR demonstrated that her witnessed convulsive events were associated with periods of a cardiac asystole lasting up to 40 seconds in duration. Following implantation of a dual chamber pacemaker, her convulsive episodes have disappeared and have not recurred over a one-year follow up period.

Discussion

Syncope, the transient loss of consciousness with spontaneous recovery occurs as consequence of a period of cerebral hypoxia. A number of conditions may disturb cerebral oxygenation, ranging from cardiac arrhythmias to periods of autonomic nervous system decompensation resulting in systemic hypotension and bradycardia. In some individuals, global cerebral hypoxia may result not only in loss of consciousness but in convulsive activity as well 6, 7, 8. These episodes of “convulsive syncope” may at times be difficult to distinguish from seizures resulting from epilepsy. Indeed, some studies have reported that anywhere between 30 -42% of patients initially thought to have epileptic seizures were later found to have convulsive syncope due to cardiovascular cause 3, 4. While a careful history and physical examination combined with directed laboratory testing are often effective in arriving at a diagnosis, in some patients establishing a clear cause for recurrent convulsive episodes may be difficult 5,6,7,8. Autonomically mediated forms of reflex syncope (such as neurocardiogenic or vasovagal syncope) may produce sudden episodes of profound hypotension and bradycardia resulting in loss of consciousness and, on occasion, convulsive activity 11-12. Linzer et al 6 reported that upto 12% of blood donors with neurocardiogenic syncope (NCS) displayed convulsive activity. We previously reported on 15 patients with recurrent seizure like episodes (thought to be due to epilepsy) unresponsive to anti-epileptic agents that were found to have convulsive NCS induced during head up tilt table testing 13.

While useful, tilt table testing is unable to identify all patients with severe NCS. In these individuals, ILR's have proven extremely valuable in detecting bradycardia and asystole due to NCS. By allowing for automatic recording of events and prolonged monitoring (up to 3 years) these devices provide a much higher diagnostic yield than traditional monitoring techniques. Zaidi et al 14 found that close to 45% of patients with atypical seizures had a cardiac related cause of these episodes, and it was only because of prolonged monitoring with an ILR that allowed this identification to be made.

In each of the patients described, the history alone did not suggest a cardiovascular cause for their convulsive events. In addition, extensive neurologic and cardiovascular evaluation failed to uncover the cause as well. It was only through prolonged monitoring with an ILR that a diagnosis could be established and adequate therapy pursued. In all three patients the presumed mechanism of the observed periods of asystole was neurocardiogenic in nature. These findings would be consistent with the classification of ILR monitored events proposed by Brignole et al 15 where the “type 1” asystolic events described here suggest that the episodes are probably due to neurocardiogenic (or neurally-mediated) mechanisms. Further information regarding mechanisms of neurocargiogenic syncope can be found elsewhere 16,17. In each patient pacemaker placement resulted in dramatic improvement in their quality of life. While it is possible that the asystolic periods observed in these patients during ILR monitoring may have been caused by an epileptic seizure, the complete disappearance of their convulsive episodes after pacemaker placement tends to argue against this explanation.

Conclusion

In patients, suffering from recurrent convulsive episodes of unknown etiology prolonged cardiac monitoring with an ILR may help identify those individuals with a potentially treatable cardiac arrhythmic cause.

References

- 1.Hauser WA, Kurland LT. The epidemiology of epilepsy in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935 through 1967. Epilepsia. 1975;16(1):1–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1975.tb04721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauser WA, Hesdorffer DC. Epilepsy, Frequency, causes and consequences. New York: Demos; 1990. pp. 21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith D, Defalla BA, Chadwick DW. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy and the management of epilepsy in a specialist clinic. Q J Med. 1999;92:15–23. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheepers B, Clough P, Pickles C. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy: findings of a population study. Seizure. 1998;5:403– 6. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(05)80010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devinsky O. Psychogenic seizures and syncope. In: Feldman, editor. Current Diagnosis in Neurology. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1994. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linzer M, Varia I, Pontinen M, Divine GW, Grubb BP, Estes NA. Medically unexplained syncope: relation to psychiatric illness. Am J Med. 1992;92(1A):18S–25S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90132-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gastaut H, Fisher William M. Electroencephalographic study of syncope: its differentiation from epilepsy. Lancet. 1957;ii:1018–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(57)92147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schott GD, McLeod AA, Jewitt DE. Cardiac arrhythmias that masquerade as epilepsy. BMJ. 1977;1:1454–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6074.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shorvon S. Medical assessment and treatment of chronic epilepsy. BMJ. 1991;302:363– 6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6773.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chadwick D. Epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:264– 77. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapoor WN. Evaluation and outcome of patients with syncope. Medicine (Balt) 1990;69:160–75. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day SC, Cook EF, Funkenstein H, Goldman L. Evaluation and outcome of emergency room patients with transient loss of consciousness. Am J Med. 1982;73:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90913-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grubb BP. Syncope and seizures of psychogenic origin: identification with head upright tilt testing. Clin Cardiol. 1992;15:839–42. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960151109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaidi A, Clough P, Cooper P, Scheepers B, Fitzpatrick AP. Misdiagnosis of epilepsy: many seizure-like attacks have a cardiovascular cause. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Jul;36(1):181–4. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brignole M, Moya A, Menozzi C, Garcia-Civera R, Sutton R. Proposed electrocardiographic classification of spontaneous syncope documented by an implantable loop recorder. Europace. 2005;7:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grubb BP. Neurocardiogenic Syncope. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1004– 1010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grubb BP. Neurocardiogenic Syncope and Related Disorders of Orthostatic Tolerance. Circulation. 2005;111:2997–3006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.482018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]